South Dakota class battleships (1939)

Battleships (1938-42):

Battleships (1938-42):

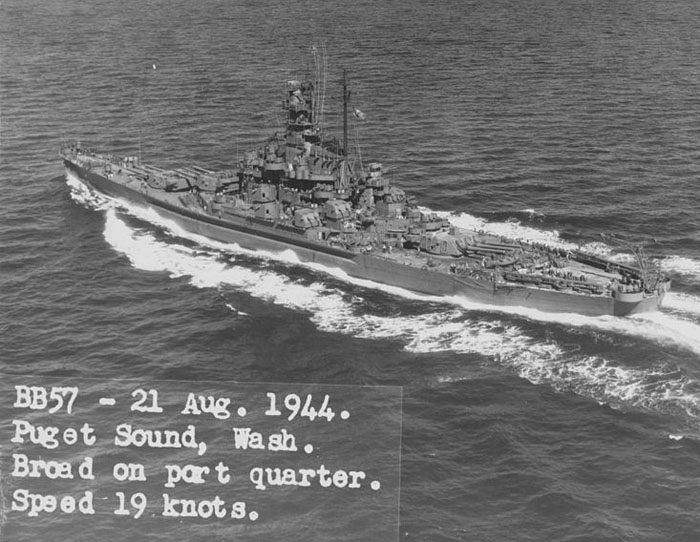

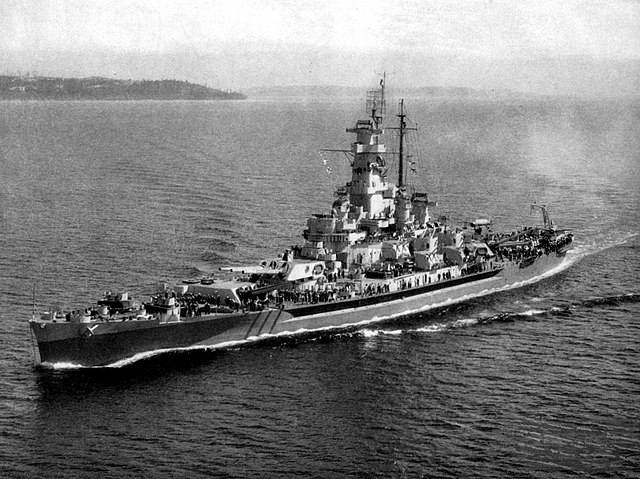

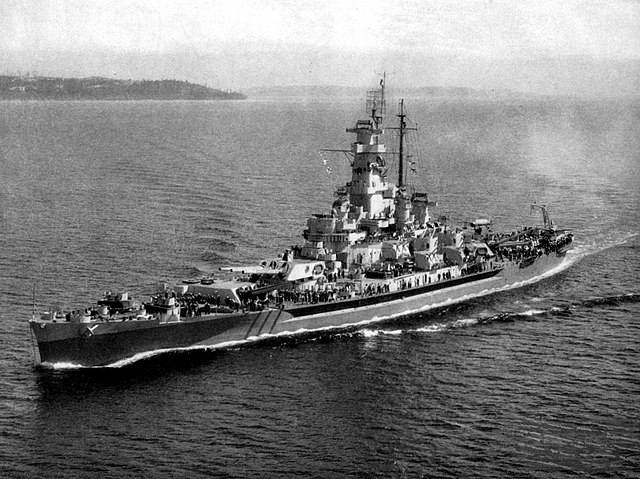

USS South Dakota (BB-57), Indiana (BB-58), Massachusetts (BB 59), Alabama (BB 60)

The shortened fast battleships

The South Dakota class was a class of four fast battleships, the lead vessel being the second named after the 40th state, taking the name of a super-dreanought class canceled under terms of the Washington Naval Treaty. The class comprised also USS Indiana, Massachusetts, and Alabama, all designed under the peacetime standard displacement limit of 35,000 long tons, like the preceding North Carolina class. Design-wise, they were basically a “repeat on budget” keeping the same main battery of nine 16″/45 caliber Mark 6 guns in three-gun turrets but, smaller, more compact, freeing weight and surface for a better protection.

They had notably a single funnel and a less favourable hull shape ratio for top speed, but miraculously just lost one knot. Construction started shortly into the war, procured as per FY 1939 for the first pair instead of FY1938 as initially planned. They were commissioned from the the summer of 1942 and served both in the Atlantic and the Pacific’s carrier groups. Their career was short as they spent most of their postwar time in reserve, until the 1960s for South Dakota and Indiana while USS Massachusetts and Alabama ended as museum ships.

Design development

Preliminary sketch in 1939

The preceding two North Carolina-class battleships were assigned to the FY1937 building program but in 1936 already the General Board wanted two more battleships allocated to FY1938. The discussion split into those these to be simple repeats of the North Carolinas, but Admiral William H. Standley (Chief of Naval Operations), wanted an improved design. He was immediately opposed by those who argued that would require a redesign and complete new calculations, making it very uinlikely they would be ready for a keel laying in 1938. Thus, after going back and forth, Standley won that they would be assigned to FY1939 instead.

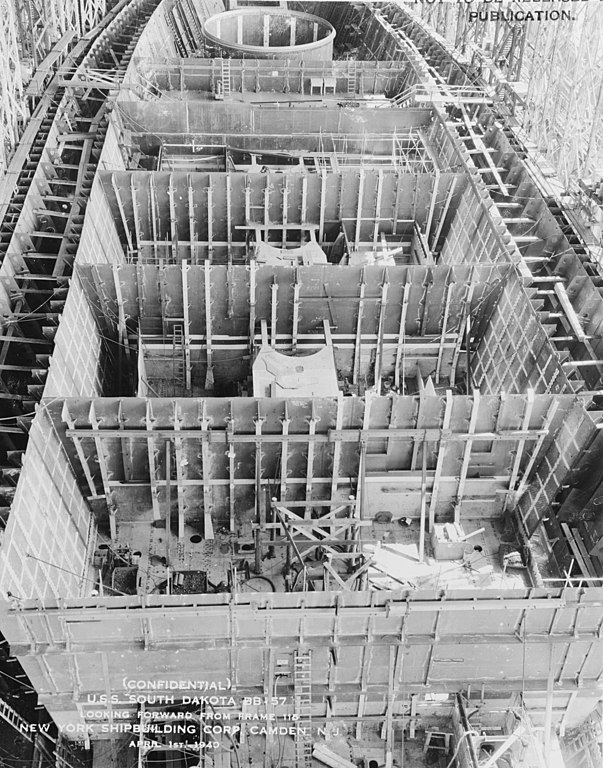

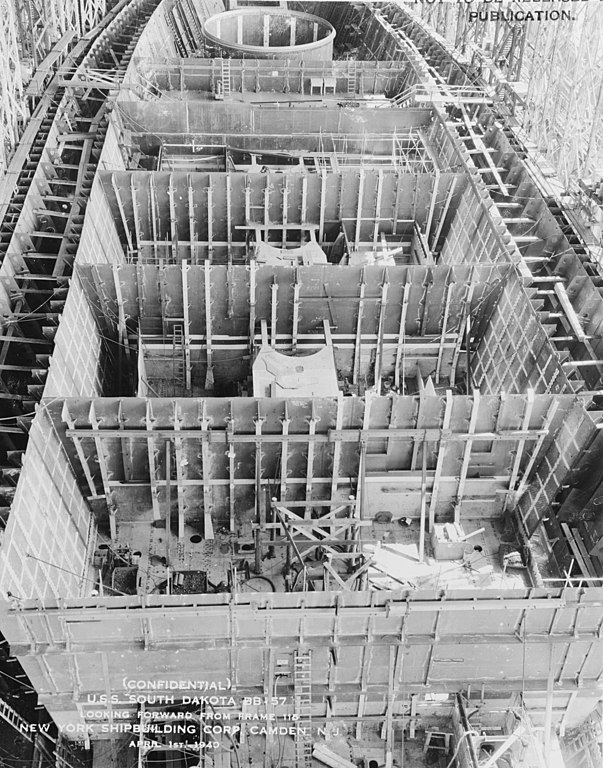

BB 57 under construction, 1st April 1940

Design work started in March 1937. The draft was formally approved by the Secretary of the Navy on 23 June after several proposal, but only detailed variants of baslcally a reduced version of the North Carolina, on a smaller displacement. This choice was also to appease some on the Congress, that saw tonnage and cost linked together and wanted to save taxpayer’s money. The specific characteristics were eventually discussed anf ixed eventually, finally approved on 4 January 1938. The formal order followed after the blueprints were ironed out, on 4 April 1938. From there starts a phase of precising all detailing blueprints for construction and call for yards.

On 25 june 1938, the deteriorating international situation both in Europe and Asia had the Congress authorizing a further two, and soon the “Escalator Clause” (passed by the Second London Naval Treaty) was activated, i be benefit of the U.S. Navy to deign working on the new (future) Iowa-class battleships. Meanwhile Congress maintained a 35,000-ton battleship tonnage for the next pair approved FY1940.

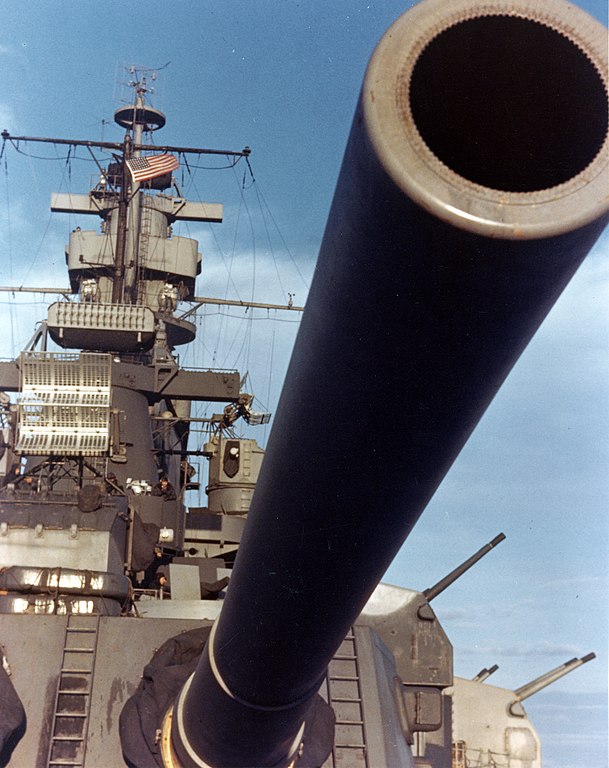

16 inches barrel

Engineers working on the BB-57 design worked out the deficiencies in the preceding North Carolinas. It was judged they had been given insufficient underwater protection. Their turbine engines also were already oudated in regards to the latest advancements. Other points seen, their accomodations to act as fleet flagships which were seen as unsufficient. Hence, the the lead ship had to be provided with an extra deck on the conning tower. Soon for stability, it was decided to sacrifice two twin 5-inch dual-purpose (DP) gun turrets.

The process was not straithforward. Treaty-wise, they were to not go further than 35,000 tons which was the frame for all claculations and constraints. In these tight margins, the above points needed to be adresses. This led to a number of proposals:

Finalized Design

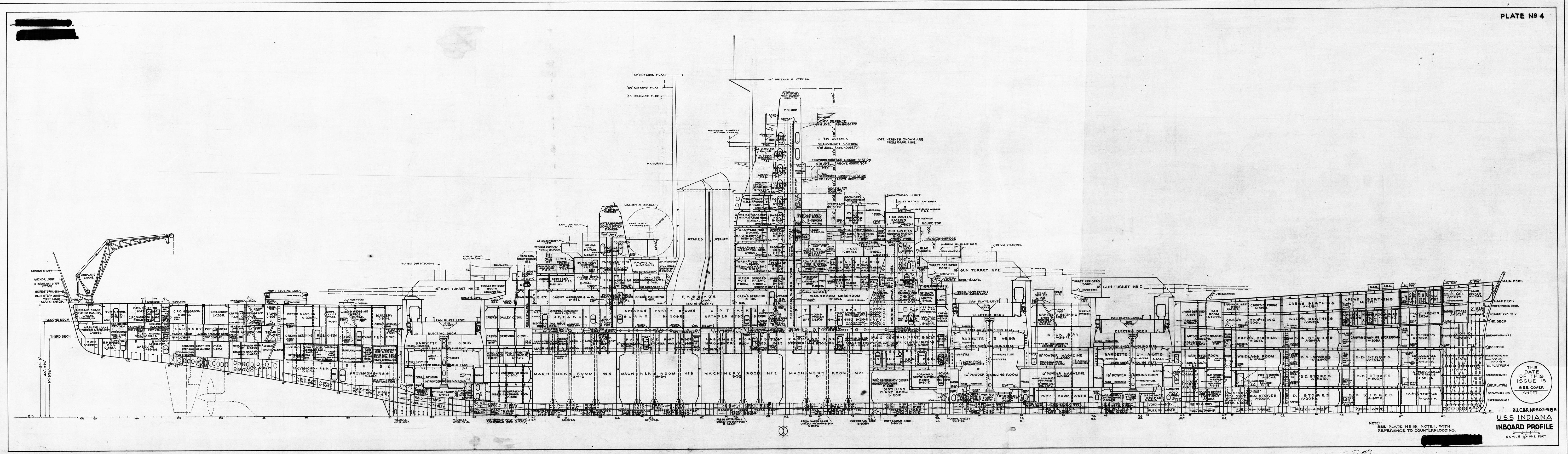

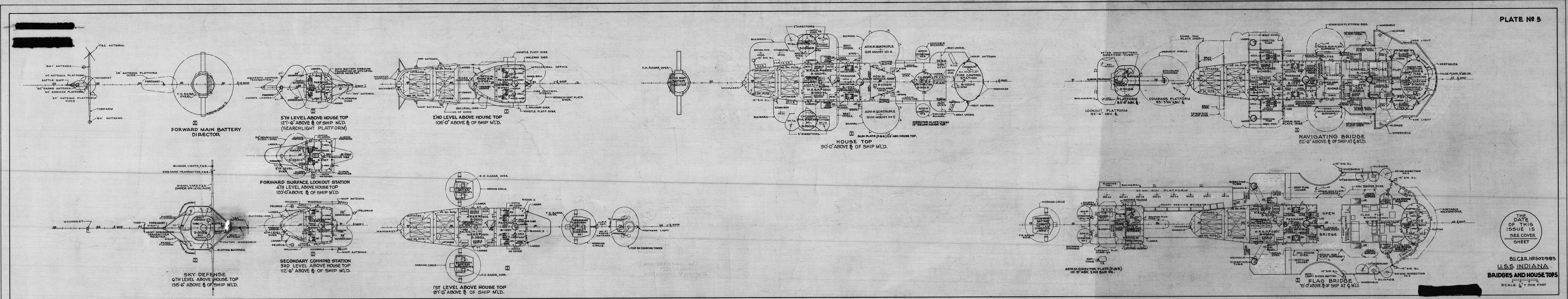

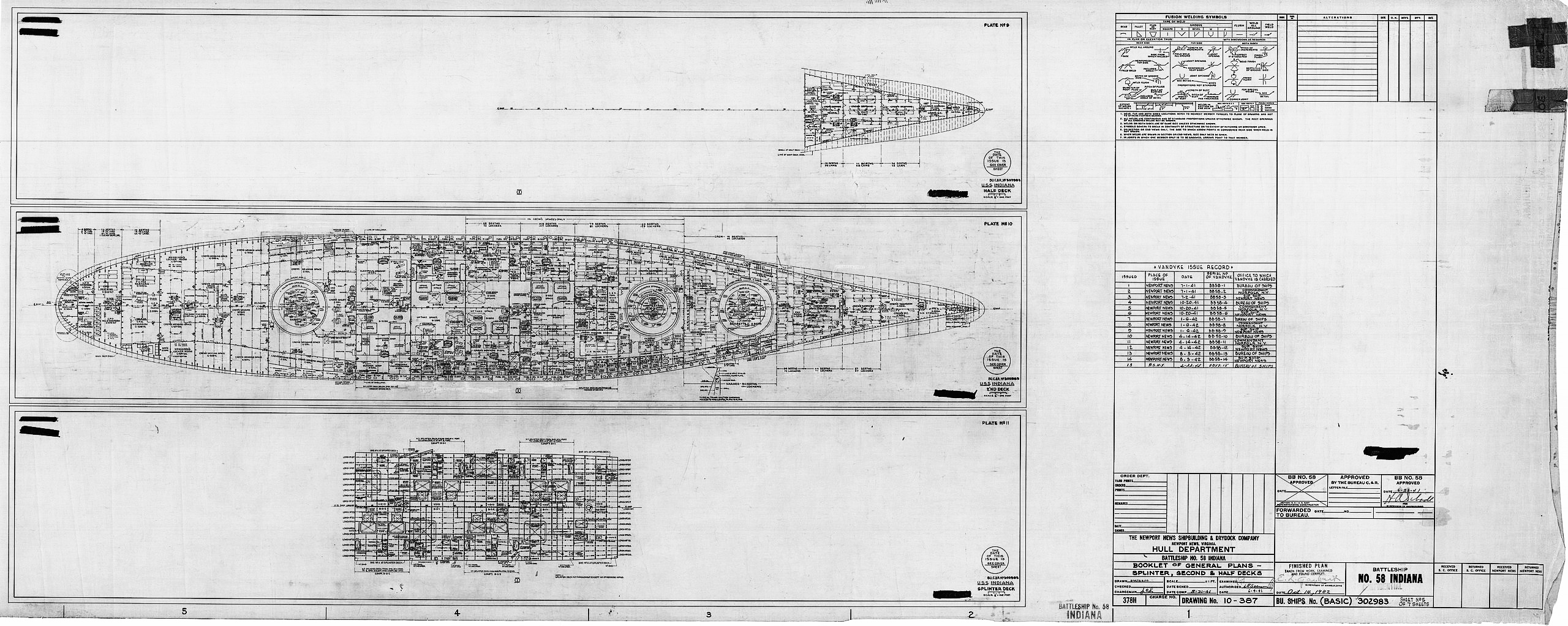

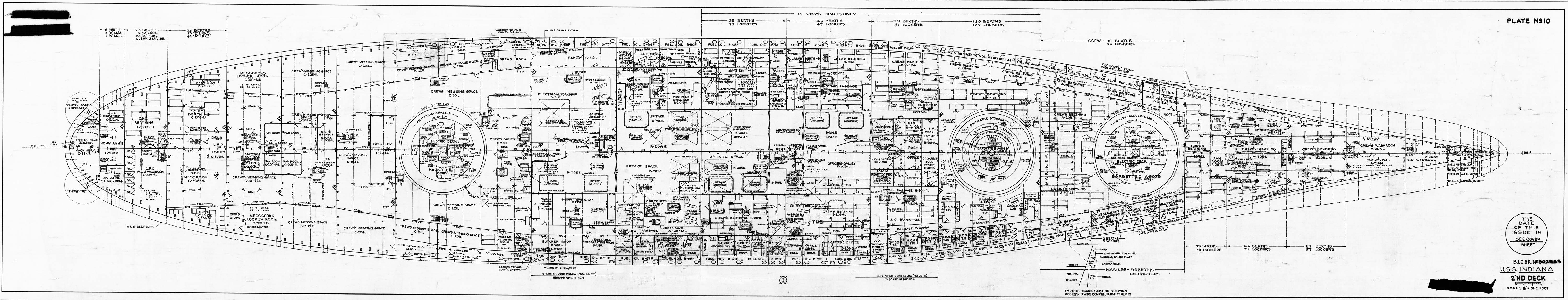

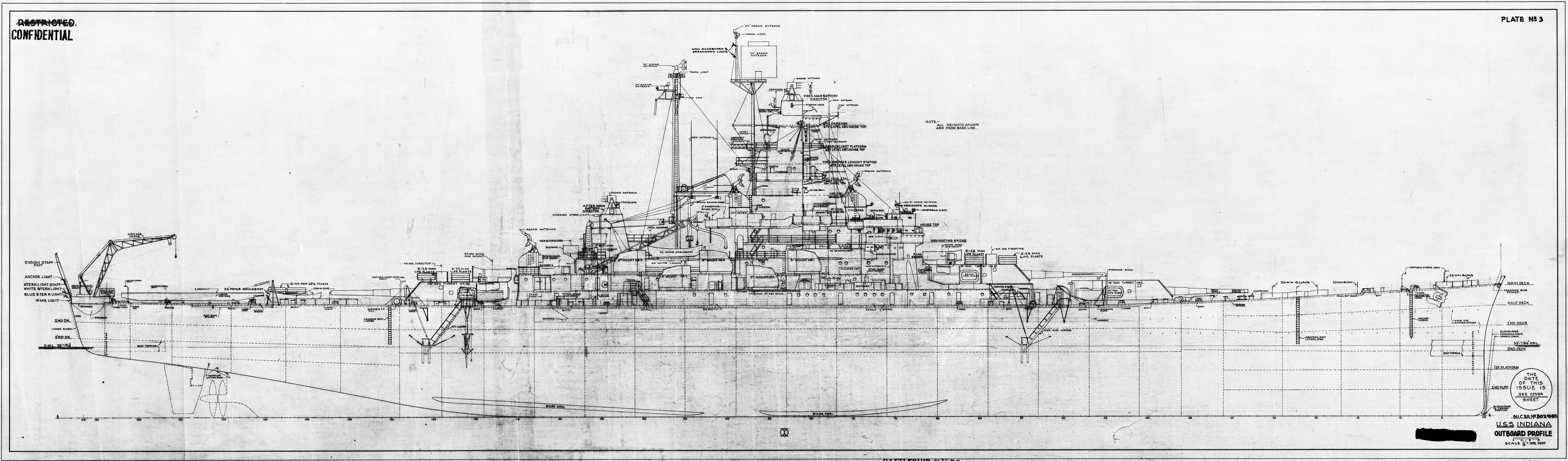

Bridges_and_House_Tops_and_Inboard_Profile

Bridges_and_House_Tops_and_Inboard_Profile

Bridges_and_House_Tops_and_Inboard_Profile

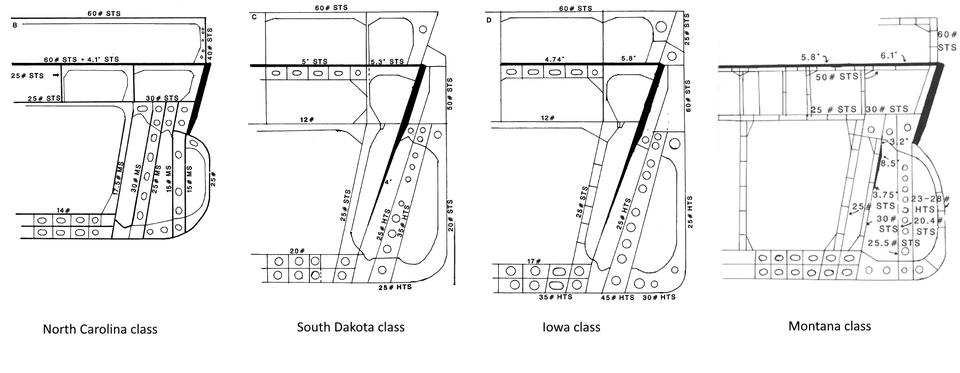

south-dakota-Splinter_Second_Half_Decks_NARA

General_Information_Data_Outboard_Profile_NARA

All agreed on a base of nine 16-inch (406 mm) guns in three triple turrets (like the previous North Carolinas) and a 5.9-inch-thick (150 mm) deck armor in order to resist plunging hit, out to 30,000 yards (27,000 m). Top speed was at least 23 knots (43 km/h; 26 mph). Belt armor was to be well above 13.5 inches (340 mm) to be proof even at at 25,000 yd (23,000 m) against 16-in shells, a practice called “balanced armor”.

Innovation: The internal armored belt

The new belt however would have ended at 15.5 in (390 mm), making the design weight way above the treaty limits. It was decided to go around this problem by featuring a sloped armor, something already adopted in the British Navy (see the N3 design), however of course it could not be external, compromising stability. Therefore just like British designs, an internal armor belt was design, behind unarmored hull plates. This was a great novelty which had serious drawbacks though, as it complicated construction and when hit, the external plating was to be cut away before repairing the main belt. But at least this first layer added some extra protection.

The solution was to slope this belt outward from the keel, and back in towards the armored deck: Shells in almost straight fire would hit the upper portion at an angle, maximizing armor protection over a thinner armour (they had more steel to cross). This upper portion effectiveness was degraded as the range increase, pluging fire encountering less and less steel. It however reduced the area to be covered by the armored deck and saved additional weight.

The final upper belt was therefire thicker, its extension answering plunging fire. Since it was internal, it was extended to the inner portion of the double bottom and thus overlapping underwater protection, fixing the issue on the North Carolinas. This double incline belt armor however was unique to this class. Later it was superseded by the single slanted belt design, which provided the sae protection while saving up to 300 tons of steel.

The question of size and speed

Propellers of USS Indiana completed by March 1942 in drydock

The size of the hull, if the same as the North Carolinas, would procured by its favourable ratio the same high top speed, but required more surface to protect. With a heavier armour it was out of question. Thus the need to have a shorter hull. A solution was to fit a higher-performance machinery, another criticism of the North Carolinas. The final hull reached 680 ft (207.3 m) versus 729 ft (222.2 m) – thus the internal space available for a larger machinery was just an impossible task.

The initial design was to have top speed of at least 22.5 knots (41.7 km/h; 25.9 mph), only to outrun surfaced submarines and stay relevant with the rest of the older dreadnoughts in battle line. But in 1936 already, US cryptanalysts deciphered radio traffic from the Japanese navy, revealing about the upgraded, reboilered Nagato class being able to reach 26 knots (48 km/h) and more.

Now engineers had to reach 25.8–26.2 kn (47.8–48.5 km/h; 29.7–30.2 mph), which would have been possible only if they managed to have the North Carolina’s machinery reduced enough to fit in the new South Dakota. Solutions were found, like repositioning boilers rooms directly above the turbines. They just recuperated the same arrangement planned in 1916 for the Lexington-class battlecruisers. They were however rearranged several times and utimately were staggered with the turbines, alongside them instea dof above. Evaporators and distilling equipment were placed in the machinery rooms also, degrading redundancy but saving space behind the armored belt. In fact this even enabled to add a second plotting room for battle direction.

The final hull design ended with a 666 ft long (203 m) between perpendiculars. The single internal sloped armor belt was a consensus and it’s deigned fixed. Fearing a rejection by General Board due to its risky choices, the engineering team proposed alternatives which were longer and faster ships, but with 14-inch guns (always in triple turrets) and also slower variants, also with 14-inch guns, but in quadruple turrets, or simply improved North Carolinas capable of 27 knots (50 km/h) and same armament of nine 16-in guns.

Speed during these dicussions proved the main issue. The fleet C-in-C (CINCUS) refused to go lower than 25 knots (46 km/h; 29 mph) and wanted for the new battle force, comprising the two North Carolinas, to reach at least 27 knots (50 km/h; 31 mph). President of the War College agreed, but wanted also compatibility with the “old fleet”, only capable of 21 knots (39 km/h; 24 mph) as they were likely to serve at least until the 1950s. It was recoignised much later that speed was indispensable later to escort fast carrier task forces…

The best treaty battleships ever

The “666 feet design” ended the winner, meeting (as expected by the design team) all the specified requirements for speed, protection, and armament. It was a near-miraculous squaring of the circle on a 35,000 tonnes design, which compared favourably with any other foreign designs at the time. In fact, according to naval historians William Garzke and Robert Dulin, they were the best “treaty battleship” ever built, later succeeded by the wartime Iowa class were wartime design free from all limitations and thus emphasized speed and protection.

By late 1937 at last, this proposed design was agreed on and a process of tweaking some detailed and adding small modifications, to save even more weight or increasing the fields of fire were made. Enginers even managed to aded berths for the crew, staterooms for senior officers, smaller but better organized mess halls, and removed ventilation ports. Apart in the superstructure, the hull was port-holes free. Artificial air circulation had its design improved to cope with these changes, and internal electrical power increased. All these were also reused for the Iowa design, by then tonnage-free, allowing further improvements. As naval analyst Norman Friedman stated:

For half a century prior to laying the Iowa class down, the U.S. Navy had consistently advocated armor and firepower at the expense of speed. Even in adopting fast battleships of the North Carolina class, it had preferred the slower of two alternative designs. Great and expensive improvements in machinery design had been used to minimize the increased power on the designs rather than make extraordinary powerful machinery (hence much higher speed) practical. Yet the four largest battleships the U.S. Navy produced were not much more than 33-knot versions of the 27-knot, 35,000 tonners that had preceded them. The Iowas showed no advance at all in protection over the South Dakotas. The principal armament improvement was a more powerful 16-inch gun, 5 calibers longer. Ten thousand tons was a very great deal to pay for 6 knots.

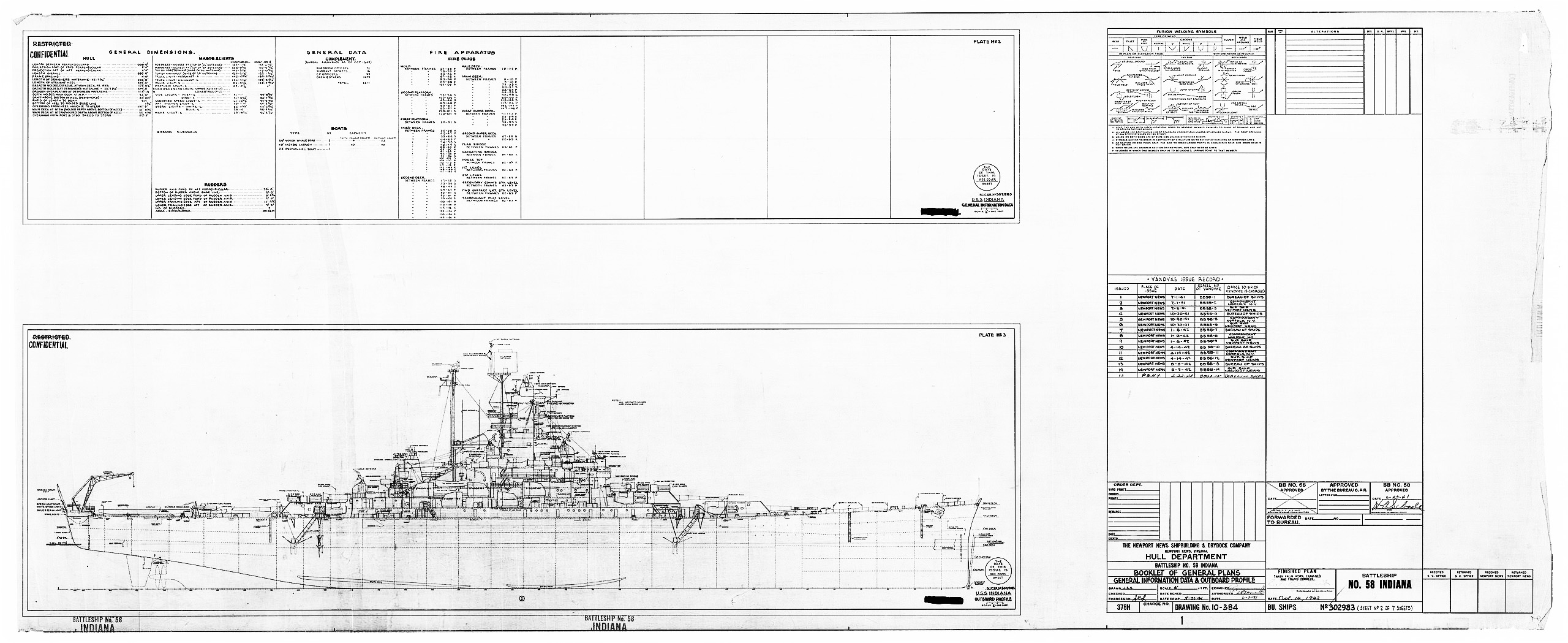

Hull design

Bridge cut showing the cramped and tall superstructure, 17 storey tall from the telemeter to the hull triple bottom.

The South Dakota-class’s final hull adopted was 666 ft (203 m) long (waterline) but 680 ft (207.3 m) overall. Compared to the North Carolinas, it was very lightly less broad 108 ft 2 in (32.97 m) in beam compared to 108 ft 3.875 in (33.017 m). The hull was also draftier to compansate at 36 ft 2 in (11 m) versus 35 ft 6 in (10.820 m).

Tonnage, standard, was calculated to 35,412 long tons (35,980 t) when completed, approximately 1.2% overweight compared to the treaty tonnage. So close to a possible war it made little difference. It was in fact much lighter than the North Carolinas at 36,600 long tons standard. When commissioned however in 1942 revisions with extra anti-air armament increased it to 37,682 long tons (38,287 t) based on Indiana on 12 April 1942. Full load it was 44,519 long tons (45,233 t) also wehen commissioned. The initial mean draft increased based upon 42,545 long tons (43,228 t) to 33 ft 9.813 in (10.3 m), metacentric height being now at 7.18 ft (2.2 m).

During the war, even more AA guns were added to the design and the full load displacement reached in 1945 for USS South Dakota at 46,200 long tons (46,900 t) and even 47,006 long tons (47,760 t) for Massachussets, but on emergency load (meaning extra oil in all free voids, extra ammunitions, ect. for long trips).

Like the previous North Carolinas, their hull featured a bulbous bow, an innovation since the reconstruction of the USS Lexintgton, and something also passed on to the Iowa class, still a common feature today. Unlike the North Carolinas or Iowas, the South Dakotas had theur outboard propulsion shafts in skegs, not inboard. In a general way their shorter hull improved maneuverability while the vibration problems were, if not cured entirely, much reduced compared to the North Carolinas.

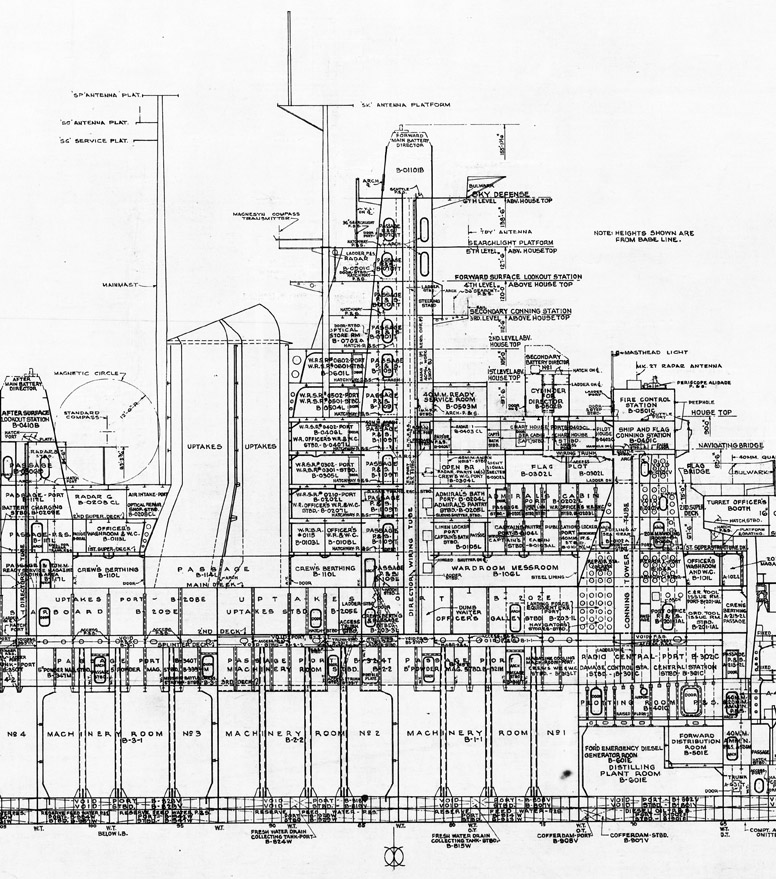

Armor protection

Comparison of armour sections

Vertical(sloped) armour

Like the previous vessels, they had a triple bottom under the armored citadel. The design was now able to resist 16-in fire, quite an improvement over the North Carolinas. The protection zone (citadel) ws calculated against the 16-inch/45 cal’s 2,240 lb shells fire by the Colorado class, calculated on a parabolic profile between 17,700 and 30,900 yd (16.2 to 28.3 km). The belt armor was just slightly thicker than the previous design, but sloped and rearranged with a brand new internal belt arrangement immune at 19,000 yards (9.4 nmi; 17 km). Special Treatment Steel (STS) was used in many parts, like for the external hull in front of the main belt. The lower belt arrangement had a decreasing thickness (but all in KC – Krupp cemented- type B armour) down to the triple bottom, a feature defeating heavy-caliber gun shells managing to hit just below the waterline. As the tonnage increased during wartime, this was made more unlikely.

Horizontal armour

Horizontal protection was sandwiched over several decks, comprising three layers: First, a 1.5-inch (38 mm) in STS for the weather deck above, called the “bomb deck” and a combined sandwich of 5.75–6.05-inch (146–154 mm) of Class B KC armour and STS for the second deck. Lastly there was a 0.625-inch (16 mm) STS “splinter deck” protecting the machinery spaces while magazines had instead a one inch (25 mm) STS third deck plating. However it was later established with the introduction of the US 2,700 lbs Mark 8 Super Heavy shell that the immune zone was now dow to 20,500-26,400 yd (18.7-24.1 km).

Underwater protection

The main principle was an internal “bulge” consisting of four longitudinal torpedo bulkheads, creating a multi-layered, blast-absorbing system. They were calculated to withstand an underwater explosion close to 700 pounds of TNT (1.3 GJ). The torpedo bulkheads were calculated to deform and absorb energy notably using several liquid-loaded compartments, either fuel oil and water. Fragments were to be stopped as well. In total between the torpedo bulkhead and compartimentation behind, it reached 17.9 feet (5.46 m), all internally.

The main feature of this system was to having the armor belt itself extended down to the triple bottom, tapered down to just one inche, as a third torpedo bulkhead (after the main tube, and compartments behind). The lower belt, lower edge was indeed welded directly to the triple bottom structure. The joint was itself reinforced with buttstraps to compensate for the knuckle.

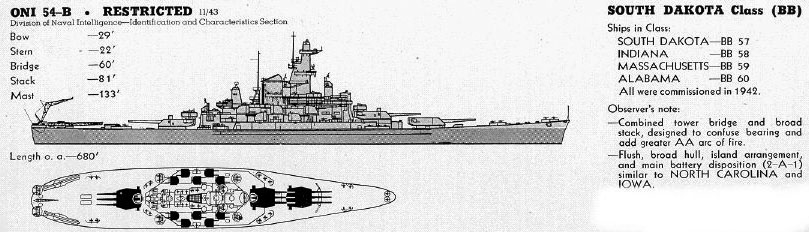

ONI depiction of the class

This seemed quite an imprvement compared to the North Carolina-class, however, caisson tests made in 1939 showed it ended less effective due to precisely this rigid lower armor belt: The detonation displaced as the result, the final holding bulkhead inward. More subscale caisson tests revealed the liquid loading scheme was also not optimal, as on the North Carolinas their 3rd and 4th outboard compartments were loded while the South Dakota’s had the two outer filled with fuel oil, the inner remaining less efficient simple void spaces, but retained to mitigate flooding by counter-flooding. Both systems were compared and improved on the Iowa class, which retained the essentally same general scheme.

Here are the resumed details:

- Outer hull plating: 1.25-inch (32 mm) STS

- Internal armor belt: 12.2-inch (310 mm)/19° (=17.3 in/440 mm) Krupp cemented

- Backup STS plate 0.875-inch (22 mm)

- Lower belt to triple bottom in KC class B 12.2 inches (310 mm)-1 inch (25 mm)

- Traverse bulkheads 11.3-inch (287 mm)

- Horizontal deck protection: 1.5 and 5.75-6.05 in

- Machinery space 0.625-inch (16 mm) STS

- Ammo magazines 1 inch (25 mm) STS

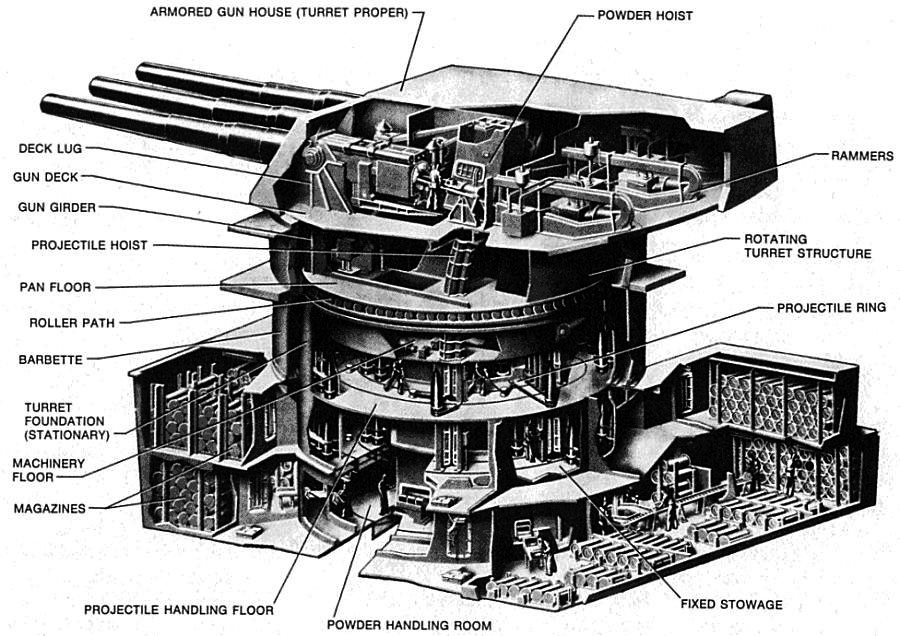

- Main battery turret, Faces: 18-inch (457 mm) Class B

- Main battery turret, sides: 9.5-inch (241 mm) Class A

- Main battery turret, Back: 12-inch (305 mm) Class A

- Main battery turret, roof: 7.25-inch (184 mm) Class B.

- Main Barbettes, upper section: 11.3 in-17.3 in (287 mm-439 mm)

- Ammunition wells & handling spaces: 2 inches (51 mm) STS

- 5-in DP barbettes and ammo wells: 2 inches (51 mm) STS

- Conning tower: 16-inch (406 mm) walls

- 4 layered torpedo bulkhead 17.9 feet (5.46 m) in width

- ASW lower belt portion: 1 in (25 mm)

Powerplant

Torpedo room

A fireman fixing an USS Alabama boiler in 1943

The South Dakota class battleships were all given the same powerplant:

-Four large 4-bladed propeller shaft* (diameter unknown, probably same as the North Carolinas), with outboard shafts mounted in skegs.

-Four General Electric geared steam turbines (Westinghouse for Indiana and Alabama)

-Eight Babcock & Wilcox three-drum express type boilers (steam pressure of 600 psi/4,100 kPa, temperature 850 °F /454 °C.

For redundancy and protection against flooding, this machinery was divided into four spaces, each having two boilers and a single set of turbines in it. That way, each of these space was capable of at least power a single shaft if the other three were flooded. However they had no longitudinal bulkheads to save space, but also as asymmetric flooding was feared.

-The Battleships were steered by two semi-balanced rudders, mounted behind the inboard screws.

The propellers montage, when completed, proved problematic as vibration tests were mostly negative. Just like the North Carolina’s they had having different propeller blade arrangements tested throughout the war:

Massachusetts and Alabama tested five bladed-ones outboard, four blades inboard. USS Indiana three bladed inboard.

Performances-wise, this powerplant was rated for 130,000 shp (97,000 kW) by design. Overheating allowed to achieve up to 135,000 shp (101,000 kW) and the 27.5 knots (50.9 km/h; 31.6 mph) designed were reached. However during the war, displacement rose while larger fuel oil storage were made (in fact the maximum) to allow refuelling smaller escorts. In 1945, USS Alabama only reached 27.08 knots (50.2 km/h; 31.2 mph) based on 42,740 tons and over 133,070 shp. With 6,600 long tons (6,700 t) of fuel oil, range was 15,000 nmi (28,000 km; 17,000 mi) at 15 knots cruising speed.

In addition, they carried each a generous electrical output, with no less than seven 1,000 kW ship service turbogenerators (SSTG) and two 200 kW emergency diesel generators and a grand total of 7,000 kW working at 450 volts alternating current.

Armament

BB 59 side top profile 1945

Main: 3×3 16-in/45 Mk.6

These were the same guns, mounts and turrets already developed for the North Carolina class. In short, while the gun type was developed from 1936 (see navweaps for more), they were essentially improved versions of the Colorado-class battleship’s main guns. This Mark 6 was developed at the end of the interwar, tailored to fire the new 2,700-pound (1,200-kilogram) AP shell from the Bureau of Ordnance in accordance to admiralty board. It could fire the AP Mark 8 (2,700 lbs/1,225 kg with a 40.9 lbs. (18.55 kg) bursting charge, the HC Mark 13 (1,900 lbs/862 kg and 153.6 lbs/69.67 kg BC) and the HC Mark 14 (1,900 lbs/862 kg).

In short:

- Muzzle Velocity: 2,300 ft/s (700 m/s) AP.

- Barrel life: 395 shells

- Traverse: 4°/second, 150° either side.

- Elevation: Max 45°, depression −2°

- Rate of fire: Two rounds a minute.

- Barrel size: 736 in (18,700 mm) oa, bore 720-in (18,000 mm), 616.9-inch (15,670 mm) rifling.

- Load mechanism: Welin breech block opening downwards

- Max range: AP 45°: 36,900 yd (33,700 m)

Secondary: 8×2 5-in/38 Mk 12 DP

Standard dual twin turret, with the standard 5-in/38. The sixteen consisted in eight turrets in all for USS North Carolina due to her large and modified conning tower/bridge ensemble. The rest of the class had twenty barrels in all, so five twin turrets on either side, three on the main weather deck, two superfiring in intervals to procure the best possible arc of fire without interruption. Combined with Mk.4 and later Mk.12 FCS radars, and VT fused shells, this combination proved very efficient, and claimed dozens of enemy planes in several occasions (see career). They had also setting for surface targets shelling, something used in several occasions during the island hopping campaign.

- Guns Weight 4,000 lb (1,800 kg) without breech.

- Mount weight 156,295 pounds (70,894 kg).

- 223.8 in (5,680 mm) long overall

- Bore length 190 in (4,800 mm)

- Rifling length 157.2 in (3,990 mm).

- Muzzle velocity 2,500–2,600 ft/s (760–790 m/s)

- Barrel life 4,600 rounds

- Depression/Elevation −15 and 85° at 15° per second.

- Traverse 150-150° on either side for battery guns (with interruptor gear)

- Traverse 80-80 degrees for deck turrets, both at 25°/sec.

- Rate of fire as designed 15 rpm

- Vertical sliding-wedge with 15 in (38 cm) recoil

- 127×680mmR 53-55 lb (24-25 kg) shell

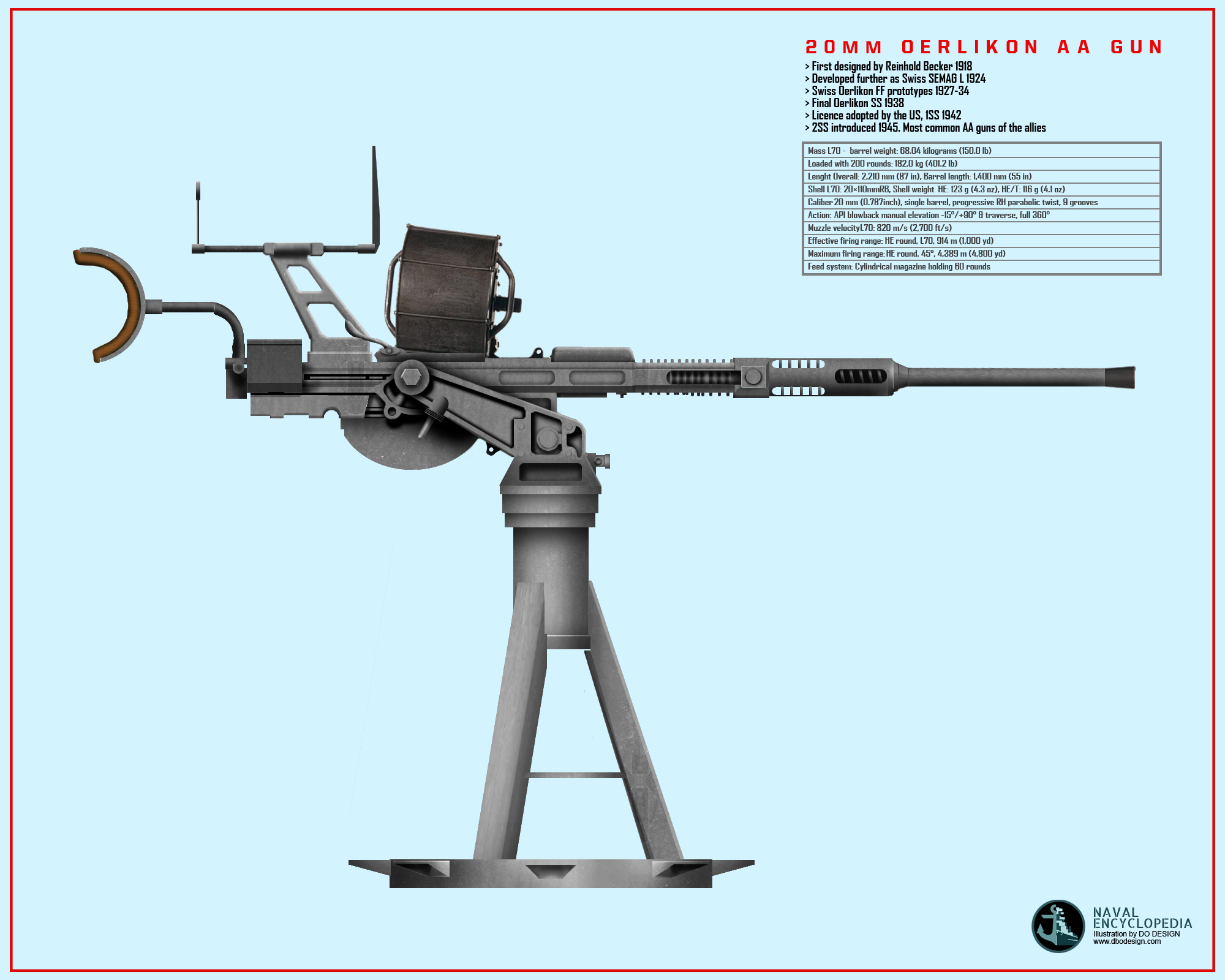

AA armament: 40 and 20 mm

Secondary Battery Control and light AA guns aboard_the South Dakota in the Atlantic 1943

At the end of their career, these ships had no less than seventy-six 40 mm/70 (1.6 in) *1943 AA guns in nineteen quad mounts, mostly placed around the main superstructure, and benifiting from an excellent arc of fire due to the compacity of this central ensemble bridge/FCS-funnel-rear FCS. So good this arrangement was taken for the rebuilding of the Pearl Harbor damaged battleships. These were standard Bofors types. See on navweaps.

Sixty-seven single 20 mm (0.8 in)/70 Oerlikon AA guns were also provided. They were arranged in twin, but mostly single mounts, under shields, and can be operated if needed by a single man, when fitted with a drum magazine. In combat, dedicated loaders ran from one to another gun to provide extra drums (stored in normal conditions around the internal face of these mounts) …and buckets of freshwater to pour on the red hot barrels. By their repective range, this steel curtain deleted any threat that went through the formidable 5-in/38 bursts.

At the start of her career, BB-57 however was planned with seven quad 28mm/75 Mk 1 – so 28 in all- (“Chicago Piano”) light AA guns and sixteen single 20mm/70 Mk 4, completed by eight single cal.05 Browning M1920 12.7mm/90 AA heavy machine guns. Needless to say, this armament was change at the first refit. BB 58 at the start had six quad 40mm/56 Mk 1.2, and sixteen 20mm/70 Mk 4, about the same as on the North Carolina class. This standard armament was repeated for BB 59 and BB 60.

It grew overtime: USS South Dakota for exampe was reamed only February 1943, with still five quad 28mm/75, but one 20mm/70 was added and thirteen quad 40mm/56 Mk 1.2. USS Massachusets at the same time received two quadruple 40mm/56 Mk 1.2, and thirteen 20mm/70 Mk 4. In 1946, BB60 (Alabama) had 5-in/38 Mk 28, twelve quad 40mm/60 Mk 2, and fifty-six 20mm/70 Mk 10.

Fire control and Radars

USS Alabama, bridge view

The South Dakota class battleships had the best radar technology available when completed. They comprised all SC air-search radars and on completion, replaced by the SK and SK-2 air-search radar. Main battery directors were assisted by Mark 3 fire-control radars, later Mark 8 from late 1942 (when their active life really started). They out-spotted the Imperial Japanese Navy by a fair margin. The latter still mostly relied on binoculars. Mark 37 directors were provided for the secondary battery, and assisted by the Mark 4 radar, later replaced by the Mark 12/22. In 1946, USS Alabama had a SG, SK-2, SR, SU,radars, two Mk 13, four Mk 12.22 and Mk 27 FCS radars, and the TDY ECM suite.

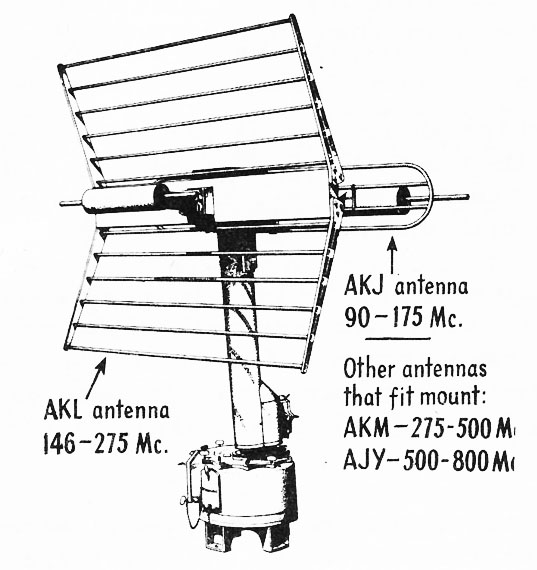

TDY Jammer in 1944

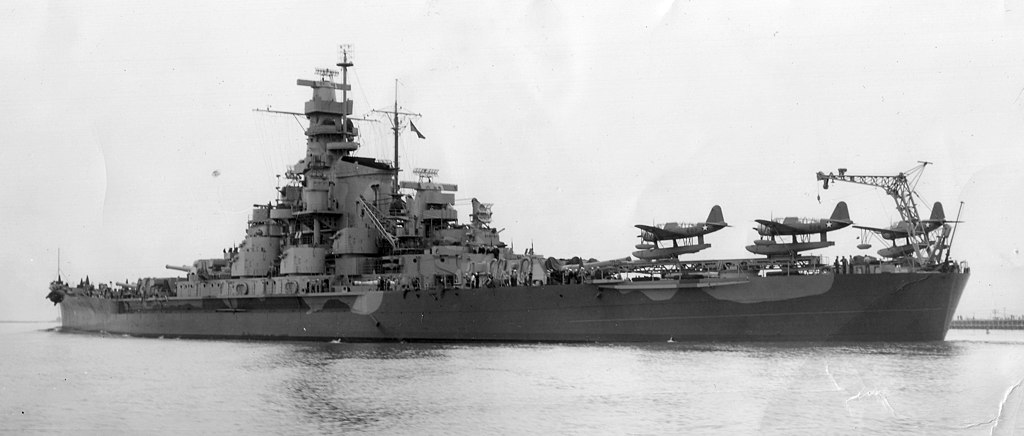

Onboard seaplanes

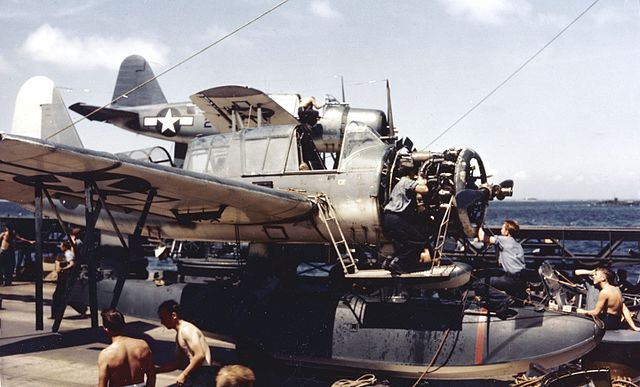

Kingfisher onboard USS South Dakota circa 1944, one in repair, the other ready for launch behind.

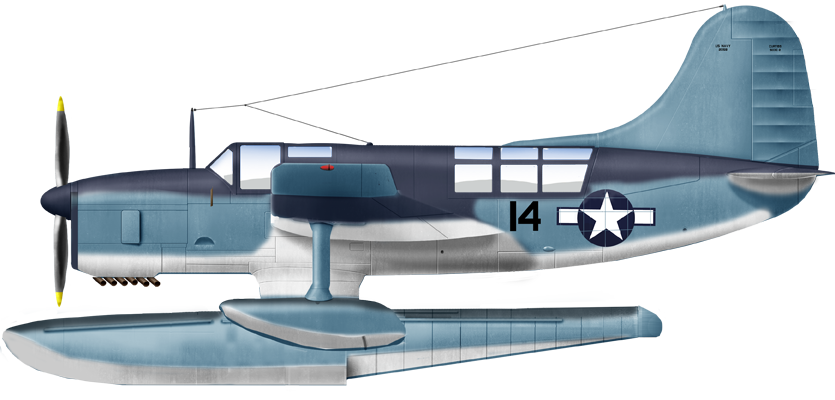

According to navypedia, these battleships operated the Vought OS2U Kingfisher, the Curtiss SOC Seagull, and Curtiss SO3C Seamew. Likely the order followed was the following: SO3C Seamew as the ship were completed in 1942, then Curtiss SOC Seagull as they were removed as to be so mediocre, and replacement likely in 1944 by the reliable Vought Kingfisher. As for other battleships, they were used both for reconnaissance and artillery spotting.

SO3C-3 Seamew (impossible to find anyone from the BB-57-60)

Two floatplanes were carried aft, made ready for launch, mounted on the two side hydraulic catapults, and one parked in between them when not in use. There was a single crane at the poop to place the seaplanes on the catapults and recover them at sea.

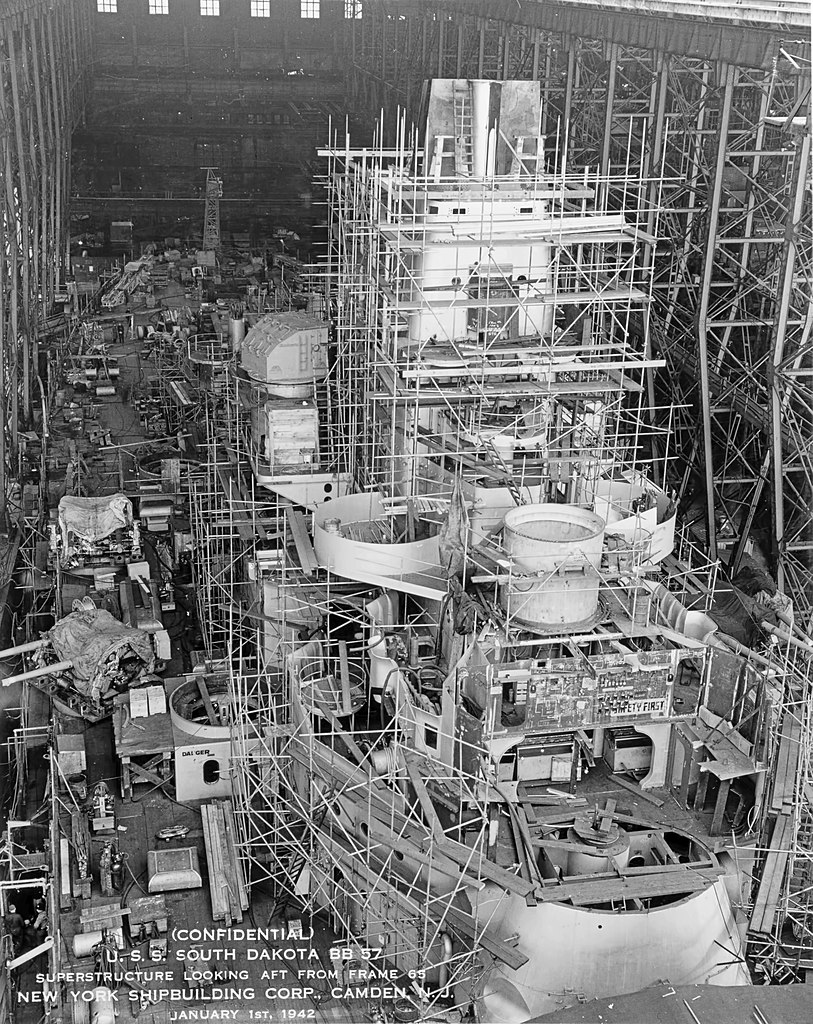

Construction

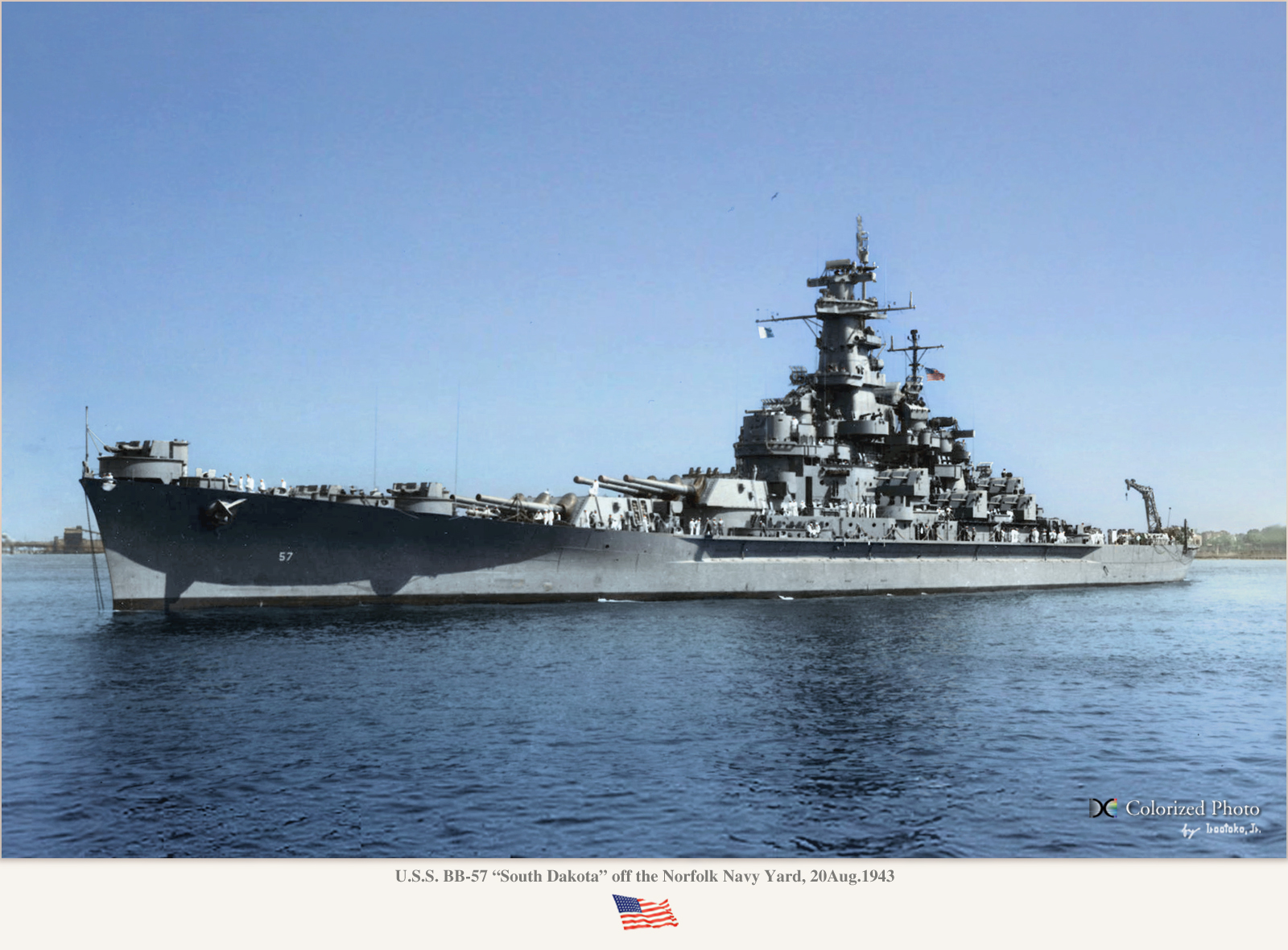

BB-57 (South Dakota) was laid on 5 July 1939 at the New York Shipbuilding Corporation (Camden, New Jersey), launched on 7 June 1941, commissioned on 20 March 1942.

BB-58 was laid on 20 September 1939 (Newport News, Virginia), launched on 21 November 1941, commissioned on 30 April 1942

BB-59 (USS Massachusetts) third of the class, was laid down on 20 July 1939 (Fore River Shipyard, Bethlehem Steel, Quincy, Massachusetts), launched on 23 September 1941, commissioned on 12 May 1942.

BB-60 was laid down on 1 February 1940 in Norfolk Navy Yard, launched on 16 February 1942, commissioned on 16 August.

USS Alabama in construction 1941 and launch.

Wartime Modifications

USS South Dakota DPLA (modifications details, ONI, February 1943, Ny NYD)

USS South Dakota received a series of modifications through her wartime career, mostly modifications and additions for her anti-aircraft battery, and modernization/addition of her electronics suite (radar sets). First came the fitting of the SC air search radar ordered in 1941, on her fore mast, later replaced by the SK type while the SG surface search radar was installed, on the forward superstructure. A second SG set was latter added to her main mast, after the Guadalcanal campaign experience. This was all done between late 1942 and early 1943.

Also by late 1942, a Mark 3 fire control radar was mounted on her conning tower to direct her main battery. Mark 4 radars were also installed for her secondary battery. The Mark 3 were replaced by Mark 8 FC radars while additional Mark 4 radars were added too until all replaced by Mark 12/22 sets. Late into the war, she also received a TDY jammer. The latter was basically a radar jamming system composed of an AKJ antenna working at 90-175mc, later upgraded to AKM-AJY types for working at 275 to 800 mc, and a larger bedframe AKL antenna working at 146-275 Mc.

In 1945 she had her spotting scopes replaced with Mark 27 microwave radar sets, in addtion to the new SR air search radar combined with its SK-2 caracteristic air search dish. Meanwhile her AA, still “stock” in November 1942, was modernized with 40 mm quadruple mounts and extra 20 mm ones, notably by February 1943, but 1945, some 20mm were removed. No specific upgrades were made postwar, at least after 1946.

Cold war carrer and proposed Conversions (1943)

Superb colorization of USS South Dakota in August 1943 by Irootoko Jr.

TF 38’s air groups were already in the air on the morning of 15 August, when Halsey learnt of Japan’s unconditional surrender. All aircraft were recalled, USS South Dakota receiving order to cease offensive operations at 06:58 while on the Japanes side, orders had a hard time to be commiunicated, so air attack went on later that day, all shot down by CAP aircraft, which also tried to signal the end of hostility how they could. USS South Dakota did not had the occasion so fire in anger that or the following days, and after refueling and replenishing she was in Sagami Wan on 27 August to cover the initial occupation of Japan.

Afterwards she moved to Tokyo Bay with Halsey and Nimitz onboard to great the crew, Nimitz remaining a bit longer, leaving for the battleship Missouri to prepare the formal surrender ceremony for the 2 September. He would returned later on BB 57 for a trip to Guam on 3 September with South Dakota sailing alongside Missouri, transferingr Halsey and his staff back on boardn becoming his flagship for the duration of the occupation until 20 September, then transferred to Pearl Harbor.

Mount Fujiyama as seen from the SOUTH DAKOTA, Tokyo Bay

USS South Dakota made it back to the United States with other ships, after stopping in Buckner Bay, Okinawa, picking up some 600 sailors, soldiers, and marines for the trip home, dispersed to different ports. She was in San Francisco on 27 October, again visited by Halsey for Navy Day celebrations and Governor Earl Warren. Next she headed for San Pedro, California and expected provisional deactivation.

On 3 January 1946 however she was reactivated and steamed for the Atlantic via the Panama Canal, heading for Philadelphia Navy Yard (20 January) for an overhaul and final preparation for full, long terme reserve and deactivation. On 21 February, RADM Thomas R. Cooley had her as hios flagship, Fourth Fleet (reserve). He was replaced by Vice Admiral Charles H. McMorris, transferred on USS Oregon City while the Fourth Fleet was dissolved on 1 January 1947. She was eventually fully decommissioned on 31 January, laid up, Atlantic Reserve Fleet.

On 26 July 1954, a conversion proposal was ordered by the Chairman of the Ship Characteristics Board. To followe the new task forces, speed was considered paramount and to be on par with the Iowa class, 31 knots was desired. The design staff came out with a radical proposal: Remove entirely the aft turret and installed in its place a set of improved steam turbines/gas turbines. On paper, the rating was to be 256,000 shaft horsepower (190 MW), which gave 31 knots after calculations. In March 1954 already she was to have her secondary batteries modernized, with ten twin 3-inch (76 mm) proposed, but it was dropped.

Though, the hull form was criticized, especially on the aft section, too bulky with the aft turret, now absent, so authorizing a radical thinning down there. Larger propellers were also required to cope with the new shape, four shafts being been completely rebuilt. In the end, for the US taxpayer this was satly: $40,000,000 were estimated as basic conversion cost per ship, not even including the total reactivation of the ship and upgrades in both electrical and combat systems. Needless to say, the Congress had the entire program halted.

Later the USN came with another, even more outlandish plan to convert her as guided missile battleship around 1956–1957. There again, conversions expected cost were deemed too prohibitive: Her main battery turrets removed, one twin RIM-8 Talos missile launcher installed forward, two RIM-24 Tartar launchers installed aft and brand new anti-submarine suite, new electronics, hangar and helicopters for $120 million.

BB 57 was listed for another fifteen years and then stricken on 1 June 1962. Sold for BU to the Lipsett Division, Luria Brothers and Co.scheduled on 25 October she was towed from Philadelphia in November to Kearny in New Jersey but some parts were saved and retained by the Sioux Falls Chamber of Commerce,installed in a memorial there on 7 September 1969. Other items were saved and place din other locations, notably in Willard Park.

On her side, USS Indiana (BB 58) departed for home on 15 September from Tokyo Bay, and upon arrival in San Francisco on the 29th, she entered the drydock at Hunters Point Naval Shipyard, fore repairs and maintenance lasting until 31 October. From there she headed for Puget Sound, and her ammunition plus other flammable material were unloaded. She entered the drydock on 15 November for deactivation. From 29 March 1946, with Postwar Plan N°2, she was transferred to the Pacific Reserve Fleet with her sister USS Alabama.

Modernization plans, like her sisters, went to nil. She stayed at Bremerton, Washington until 27 June 1961 Admiral Arleigh Burke (Chief of Naval Operations) designated her as eligible for disposal, so she was stricken by recommendation on 1 May 1962, by Fred Korth, the Secretary of the Navy, effective on 1 June. She sold for scrap on 6 September 1963, BU. Several parts were saved, between the Allen County War Memorial Coliseum in Fort Wayne, Indiana, Heslar Naval Armory in Indianapolis,Shortridge High School, Memorial Stadium, Indiana University as other parts. A dedication ceremony was held with the last veterans on September 2013.

After the Japanese surrender on 15 August, USS Massachusetts (BB 59) departed on 1 September for Puget Sound, being overhauled there until 28 January 1946, and she was berthed south of San Francisco, California, before sailing to Hampton Roads, Virginia, being there on 22 April. She was decommissioned on 27 March 1947 at Norfolk, Virginia, assigned to the Atlantic Reserve Fleet. Placed in reserve to modernization, there were planed made for future active service that went to nil. She was stricken on 1 June 1962, 5,000 tons of equipment removed for other vessels, which included her explosive-driven catapults, relocated on coastal naval stations. She was not BU however, but became a museum ships (see later).

BB 60 on her side was still in Tokyo Bay on 5 September, she embarked crew-members ashore and departed on 20 September for Okinawa, embarking 700 men (most being Seabees) as part of “Magic Carpet” arriving in San Francisco on 15 October. She remained there for Navy Day celebrations on 27 October, visited by some 9,000. Next she was in San Pedro, California until 27 February 1946 and departed for an overhaul at Puget Sound and deactivation. After several modernization plans went nowhere, decommissioned from 9 January 1947 at NAS Seattle, Pacific Reserve Fleet (Bremerton, Washington), she was scheduled to be sold for BU after being stricken on 1st June 1962. Instead, she was repurchased by former veterans like her sister ship (see below).

USS Massachusetts Museum at Battleship Cove

The Massachusetts Memorial Committee was a creation by veterans, which successfully raised enough money to repurchase her from the Navy: On 8 June 1965, the Navy transferred ownership to the state of Massachusetts.On 14 August, she was anchored in Fall River (now Battleship Cove) permanently, together with the destroyer USS Joseph P. Kennedy Jr., Gato class submarine USS Lionfish, and much later the East German corvette Hiddensee, two PT boats and other vessels for a one-day long visit. Some parts were repurchased and a new paint coasting was made for long term preservation.

In the early 1980s however, the USN reactivated the four Iowa clas and needed parts urgently. Many were taken from the preserved BB 59 and BB 60 to restore them. Engine room components mostly. USS Massachusetts became nevertheless a National Historic Landmark, and added to the National Register of Historic Places on 14 January 1986. Externally she however remained in her wartime configuration, to the delights on visitors.

Main guns

From November 1998, she was closed to the public to be shipped to Boston and her overhaul. The 300-mile (480 km) trip under tow by tugs up to Boston were she arrived on 7 November, in Drydock Number 3. After inspection it was decided to add steel plating along her hull for sea water corrosion, deal with leaking rivets and repair her propellers. 225,000 pounds (102,000 kg) of steel were added to her hull with Red Hand Epoxy to encase and protect her hull and she was underway again on March 1999, towed back to Battleship Cove, on 13 March were a ceremony was held. The museum is open from 10-3 every Wednesday-Sunday, tickets can be purchased online.

Twin 20mm gun mount aboard USS Massachusetts today

As a Museum ship at Battleship Memorial Park, Mobile

This time, the offensive to have her preserved was led by the state of Alabama first. The “USS Alabama Battleship Commission” was established with the help of many vets, by Governor George Wallace, which signed a law on 12 September 1963 creating the organization to raised funds, and $800,000 were obtained, mostly from children in the state and bugger funds from corporate donations. On 16 June 1964 she was recalled, under conditions the Navy would repurchase her for a recomm. in the event of an emergency.

Handed over on 7 July to the state, in Seattle, she towed to Mobile to be restored as a museum, making her last Panama Canal crossing. She was escorted there by USS Lexington through the Gulf of Mexico. Arrived on 14 September after a record 5,600 nautical miles (10,400 km; 6,400 mi) under tow, she had permanent berth not yet been completed, waiting until the end of the month. Preparations for visitors including sandblasting painted surfaces, applying a primer, re-painting the entire ship, then providing a clear display trip inside with panels and displays; She reopened on 9 January 1965.

Like her sister she was cannibalized in the early 1980s to restore the Iowas, became a National Historic Landmark in 1986 and was used as a set for several movies lik “Under Siege” (1992) and “USS Indianapolis: Men of Courage” in 2016. In 2002 it was agreed to finance the removal of 2.7 million gallons of seawater contaminated with fuel oil, which required erecting a cofferdam, pumping it dry to allowed workers doing their job, instead as having the vessl carried to a drydock. USS Drum (aslo part of the musem) was was moved on land display for the same reason. The battleship was damaged by Hurricane Katrina in September 2005 and repairs were done by Volkert, Inc.

Author’s illustration of USS Alabama at Guadalcanal in December 1942 (More HD to come)

South Dakota class specifications |

|

| Dimensions | 203 x 33 x 11m (666 ft x 108 ft 2 in x 36 ft 2 in) |

| Displacement | 35,000 long tons standard, 44,519 tons FL |

| Crew | 1,693 in 1942, 2,634 in 1945 |

| Propulsion | 2 shafts GS turbines, 8 WT boilers, 130,000 ihp |

| Speed | 27.5 knots (50.9 km/h; 31.6 mph, as designed) |

| Range | 15,000 nmi (28,000 km; 17,000 mi) at 15 knots |

| Armament | 3×3 16-in, 8×2/10×2 5-in/38, 76x 40mm, 67x 20mm AA, 3 seaplanes |

| Armor | Belt 12.2 in, Bulkheads 11.3 in, Barbettes 17.3 in, Turrets 18 in, CT 16 in, Decks 1.5 in |

Read More/Src

Books

Gardiner, Robert. Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships 1860–1905

Friedman, Norman (1986). U.S. Battleships: An Illustrated Design History. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press.

Garzke, William H.; Dulin, Robert O. Jr. (1995). Battleships: United States Battleships 1935–1992 (Rev. and updated ed.). Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press.

Morss, Strafford (2006a). “The Washington Naval Treaty and the Armor and Protective Plating of the USS Massachusetts: Part I-II”. Warship International.

Miller, David (2004). The Illustrated Directory of Warships from 1860 to the present day. London: Salamander Books.

Morss, Strafford (December 2010). “Excellence Under Stress: A Comparison of Machinery Installations of North Carolina, South Dakota, Iowa, and Montana Class Battleships: Part I-II”. Warship International.

Morss, Strafford (2004). “The Machinery Arrangements of USS Massachusetts (BB-59)”. Warship International.

Frank, Richard B. (1990). Guadalcanal: The Definitive Account of the Landmark Battle. Marmondsworth: Penguin Books.

Friedman, Norman (2014). Naval Anti-Aircraft Guns and Gunnery. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press.

Friedman, Norman (1985). U.S. Battleships: An Illustrated Design History.

Hornfischer, James D. (2011). Neptune’s Inferno: The U.S. Navy at Guadalcanal.Bantam Books

Mooney, James L., ed. (1976). Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships: Historical Sketches—Letters R through S. Vol. VI. Washington DC

Morison, Samuel Eliot (1956). The Atlantic Battle Won. May 1943 – May 1945. History of United States Naval Operations in World War II. Vol. X (2001 reprint ed.)

Rajtar, Steve & Franks, Frances Elizabeth (2010). War Monuments, Museums and Library Collections of 20th Century Conflicts: A Directory of United States Sites.

Rohwer, Jürgen (2005). Chronology of the War at Sea, 1939–1945: The Naval History of World War Two. Naval Institute Press

Terzibaschitsch, Stefan (1977). Battleships of the U.S. Navy in World War II. Munich: J.F. Lehmanns Verlag.

Wilmott, H. P. (2015). The Battle of Leyte Gulf: The Last Fleet Action. Bloomington

Tomblin, Barbara (2004). With Utmost Spirit: Allied Naval Operations in the Mediterranean, 1942–1945. University Press of Kentucky

Wilmott, H. P. (2015). The Battle of Leyte Gulf: The Last Fleet Action. Bloomington: Indiana University Press

Morss, Strafford (1988). “Re: The Battleship Massachusetts WI No. 4, 1986”. Warship International. XXV (4)

O’Hara, Vincent P. (2021). Battleship Massachusetts. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press.

Whitaker, Kent (2013). USS Alabama. Charleston: Arcadia Publishing.

Battleship USS Alabama: BB-60 Golden Anniversary History. Paducah: Turner Publishing Company. 1993.

Links

Construction of South Dakota’s bridge during completion in Camden, January 1942.

JSTOR: The Machinery Arrangements of USS “Massachusetts” (BB-59) by Strafford Morss

South Dakota on history.navy.mil

Battleships : United States battleships, 1935-1992 by Garzke, William H; Dulin, Robert O.

Guadalcanal : the definitive account of the landmark battle by Frank, Richard B

War Service Fuel Consumption of U.S. Naval Surface Vessels – FTP 218, Commander in Chief HQ 1945

U.S.S. SOUTH DAKOTA(BB 57) WAR DAMAGE REPORT Puget Sound NyD 19 JUNE 1944

Massachsetts on history.navy.mil

South Dakota on hnsa.org

Alabama on hazegray.org

Alabama on navsource.org

Alabama on hnsa.org

Damage report on hyperwar ibiblio.org

Video: Battleship X

USS South Dakota’s stern floatplanes

Model kits

A lot of choices, at all scales. Here Trumpeter 1:700

A lot of choices, at all scales. Here Trumpeter 1:700

Massachusetts hull-the Scale Shipyard 1:96, Alabama Oriol (Oriel) 1:200, USS Massachusetts BB-59 (1945) Blue Water Navy 1:350, USS Alabama/Massa Trumpeter 1:350, SDakota Yankee Modelworks 1:350, USS Indiana Tamiya 1:500, USS South Dakota “Super Detail” Limited Edition Hasegawa 1:700, Alabama and others Hasegawa 1:400, the class on Pit-Road 1:700, Trumpeter 1:700, VEE HOBBY 1:700, Revell 1:720, Hansa/Xp forge/Bandai 1:1200, Navis 1:1250, Fujumi 1:3000.

South Dakota general query scalemates

Revell 1:720 full doc pdf

Indiana 1:1250 On Steel Navy

Gallery

The South Dakota class in service

USS South Dakota (BB 57)

USS South Dakota (BB 57)

When completed, Captain Thomas Leigh Gatch took command of USS South Dakota. On 16-17 May she did machinery tests in the Delaware river. Fitting out work lasted until 3 June and on the 6th she started her shakedown cruise escorted by four destroyers due to the presence of German U-boats off the east coast. She trained until 17 July and departed for Hampton Roads in Virginia, and was back north to meet USS Washington off Maine, Casco Bay (21 July) for firing practice. She was back in Philadelphia and prepared for active duty, being ready on 26 July.

Unlike some of her sister ships, she was sent directly to the Pacific where she spent all her career. Admiral Ernest King as the battle of the Solomons develped called USS South Dakota, Washington and Juneau escorted by six destroyers to the south Pacific. Here, she became BatDiv 6 (Rear Admiral Willis Lee, from 14 August, hoisting his flag aboard South Dakota. She had an engine breakdown while en route and went through the Caribbean, Panama and reached Guadalcanal later in August, metting USS Juneau to proceed to Nukuʻalofa in Tongatapu attoll (4 September 1942). On the 6th while en route after refuelling she struck an uncharted reef in the Lahai Passage. Divers from Vestal discovered a 150-foot (46 m) mushed plating, which was patched so she can proceed to Pearl Harbor on 12 September for permanent repairs.

There, she met USS Saratoga, also in repairs since a submarine attack south of Guadalcanal. On 28 September she was underway again wth some AA modifications and additions. After provisioning and some training she departed Pearl on 12 October, making anti-aircraft training until 14 October and heading with Task Force 16 (USS Enterprise, 9 destroyers), ordered by Vice Admiral William F. Halse to make a sweep off Santa Cruz Islands before heading for the Solomons, joined her by TF 17 (USS Hornet), combined into TF 61 (RADM Thomas C. Kinkaid) and supported by Lee’s TF 64 (USS South Dakota, Washington, 2 heavy cruisers, 2 light cruisers, 6 destroyers). This was her first battle.

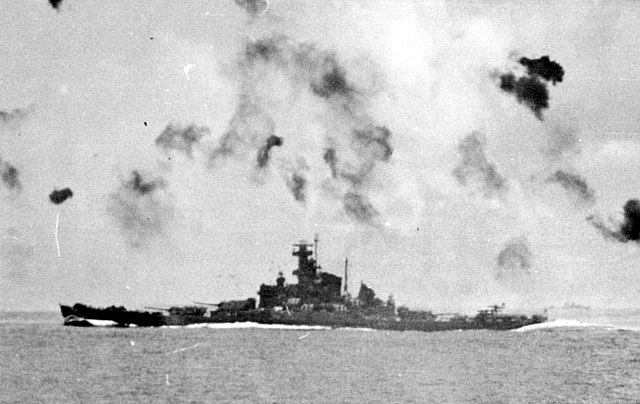

Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands

USS_South_Dakota_BB-57_underway_at_high_speed_during_the_Battle_of_the_Santa_Cruz_Islands_26_October_1942

On 25 October, reconnaissance planes spotted each other’s fleets and USS South Dakota’s prepared for night surface action that never happened, however they were spotted by the Japanese east of Rennell Island and thus, the IJN was drawn to them and away from TF 61. Air strikes followed, USS Hornet was seriously damaged and withdrawn while USS South Dakota and Enterprise had no damage, until the second strike aimed at CV-5 after 10:00. USS South Dakota provided heavy AA fire and claimed 7 aircraft (assisted).

She managed to beat also the third wave, when at 11:48, several Nakajima B5N torpedo bombers targeted South Dakota, forcing her quick evading manoeuvers, in which she dodged all torpedoes, shoot down one “Kate”. The fourth strike saw her attack by a group of Aichi D3A dive bombers, forcin her again to manoeuvr hard over, but they all missed but one, hitting her forward main battery turret roof. Fortunately, the armor stood the schock. There was concussion inside though, damaging some parts and knowcking the crew on the floor. Captain Gatch, was wounded by a bomb splinter, and thrown into the wall by the concussion. Two were killed, fifty wounded by Splinters which had the left gun of “B” turret damaged.

B5N2 flies near USS South Dakota Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands 26 October 1942

Miscommunication while transferring steering control to the station caused her to haul out of formation briefly, heading dangerously at USS Enterprise before it was corrected. As night fell the battle was mostly over. USS South Dakota’s gunners claimed in all 26 Japanese aircraft, a remarkable tally that was later corrected to 13, and for the entire TF 16 combined. Some of her wounded sailors were casualties from A6M Zero fighter‘s strafing attacks. South Dakota’s AA fire was nonetheless exaggerated by the press. But at this point, her unassisted 5-inch guns, her inadequate 1.1-inch “Chicago Piano” had a hard time in low clouds. Apparently 20 mm guns made 2/3 of these claims in the action report.

While en route to Nouméa, New caledonia, for resplenishing, USS South Dakota avoid a submarine attack and collided with USS Mahan on 30 October. Mahan’s bow struck her to port, damaging an area close to Frame 14. Vestal repaired later South Dakota’s hull and battle damage from Santa Cruz. On 6 November she was at sea again and since only USS Enterprise was left operational in the Pacific, Halsey scrambled USS Washington, to join USS South Dakota to escort her as TF 16, reibforced with USS Northampton, and 9 destroyers back from 11 November to Guadalcanal. USS Pensacola plus her own two escorting destroyers on the 12th. The following day, warned of an incoming attack, Halsey detached South Dakota, Washington, and 4 destroyers (TG 16.3) under Lee’s command to defend the area, moroeover now that USS Enterprise had her forward elevator damaged and kept south in backup. A Battle soon developed:

Second Naval Battle of Guadalcanal

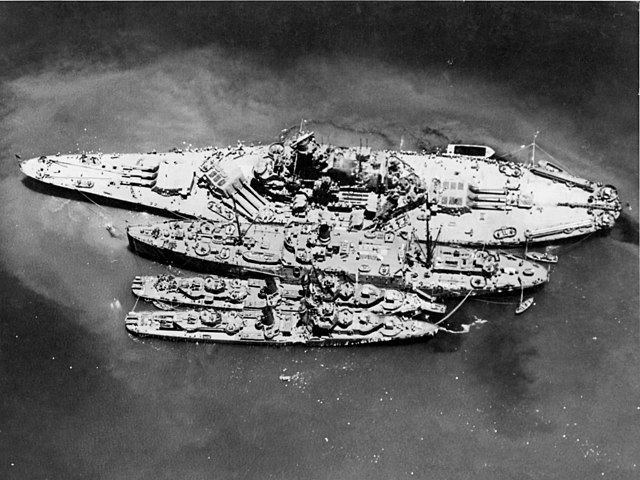

USS South Dakota two destroyers alongside USS Prometheus (AR-3) November 1942

Lee’s just renamed TF 64 tried to find Admiral Nobutake Kondō’s Kirishima, Takao and Atago, screen by destroyers on 14 November, rounded south of Guadalcanal the western end to block his expected path, when spotted by an aircraft, but was improperly reported as a much larger force, confusing Kurita. He was in turn spotted off Savo Island. The battle started at 23:00 with a destroyers brawl, those under Shintarō Hashimoto ahead of Kondō spotting Lee’s shiops, reporting and moved to attack. Conversely they were spotted by USS Washington’s search radar (a rare early case where the “eyeball Mk.I” defeated USN radar). Hashimoto’s cruisers prepared for attack, and Lee ordered Washington and South Dajot to engage when ready.

USS Washington fired first at 23:17 from 18,000 yd (16,000 m) and next South Dakota, with her six forward guns due to her still faulty aft turret from Santa Cruz. Radars and optical directors were used for this night fight with efficicacy and South Dakota first targeted IJN Shikinami but missed, which turned away, before firing on Ayanami and Uranami, claiming hits on both which was untrue. USS Washington finished off Uranami quickly with her secondaries.

At 23:30, an error in the electrical switchboard room had USS South Dakota left without power, a catastrophy given the circumstances ! Her radar systems were off, but not her artillery, although she was now blind. Hashimoto’s successes on the US destroyers gave him leeway to approach while to keeping clear of the burning destroyers wrecks, the unlucky battleship was backlited, highlighted to Japanese spotters, which opened fore at 23:40 while South Dakota tried to engage them with her rear turret, accidentally setting a Kingfisher on fire, the rest being destroyed for good by her second salvo. Power was at last restored after frantic efforts, so she can accurately direct her fire for five salvoes atf 5,800 yd (5,300 m).

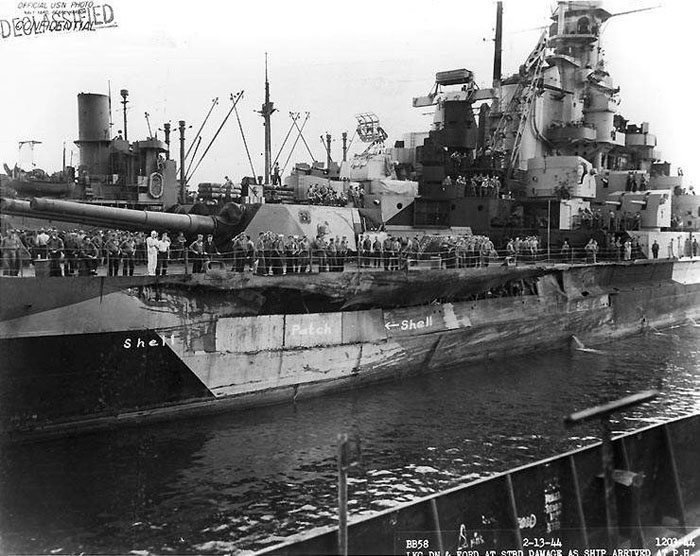

Something not anticipated is that the blast was enough to cnock other electrical parts so that her gunnery and search abilities were again shut for five minutes. Her search radar still picked up many targets ahead, while the latter turned to launch a massive “long lance” volley at South Dakota, but missed. While at 5,000 yd (4,600 m) she was in a midst oh hell, firing all her guns, inclusing the secondaries and even AA while illuminated by Japanese destroyers and having Kondo’s full concentrated fire on her. [insert metal concert here] She received 27 hits, with 14-inch shell from Kirishima. Her rear turret was hit but resisted, having its training gear jammed however.

Most hits were medium-caliber from cruisers (still 8-in inches) and destroyers imed at her largely unprotected superstructure. The radar sets were knock out of action, her radio systems were destroyed as many other systems, plus losses of lives and shattered bridges. She was left as her captain put it later, “deaf, dumb, blind, and impotent.” USS Washington in the meantime, left unengaged, came back with a vengeance on Kirishima while South Dakota still fired two or three salvos at a cruiser before targeting Kirishima, with five salvos until her main gun directing systems were destroyed.

Guadalcanal Damage report, USS South Dakota

Her secondary battery all the time barked furiously while Washington’s accurate main battery fire started to badly maul Kirishima, so shortly after midnight, Kondō turned his remaining ships in a second attempted torpedo attack. Kirishima was now out of control and 00:05, fire ceased wheras South Dakota at 27 knots (50 km/h; 31 mph) was in hot pursuit, ceasing fire herself at 00:08. Gatch all this time could not communicate with Lee and by default, turned south to disengage.

This was time for damage assessment: -Hit below the waterline (minor flooding, list 0.75 degrees) quickly corrected. Fires in the superstrcuture, mastered at 01:55. Radio repaired at 02:00, contact restored with USS Washington. Captain Gatch informed Lee also of his condition and the latter ordered him to withdraw at high speed. The crew suffered the most, with 40 killed, 180 wounded including a 12-year-old booy named Calvin Graham who lied about his age to enlist and became the youngest American in combat. The battleship received her first Navy Unit Commendation and at 09:00 AM on the following say she was reunited with USS Washington, Benham and Gwin.

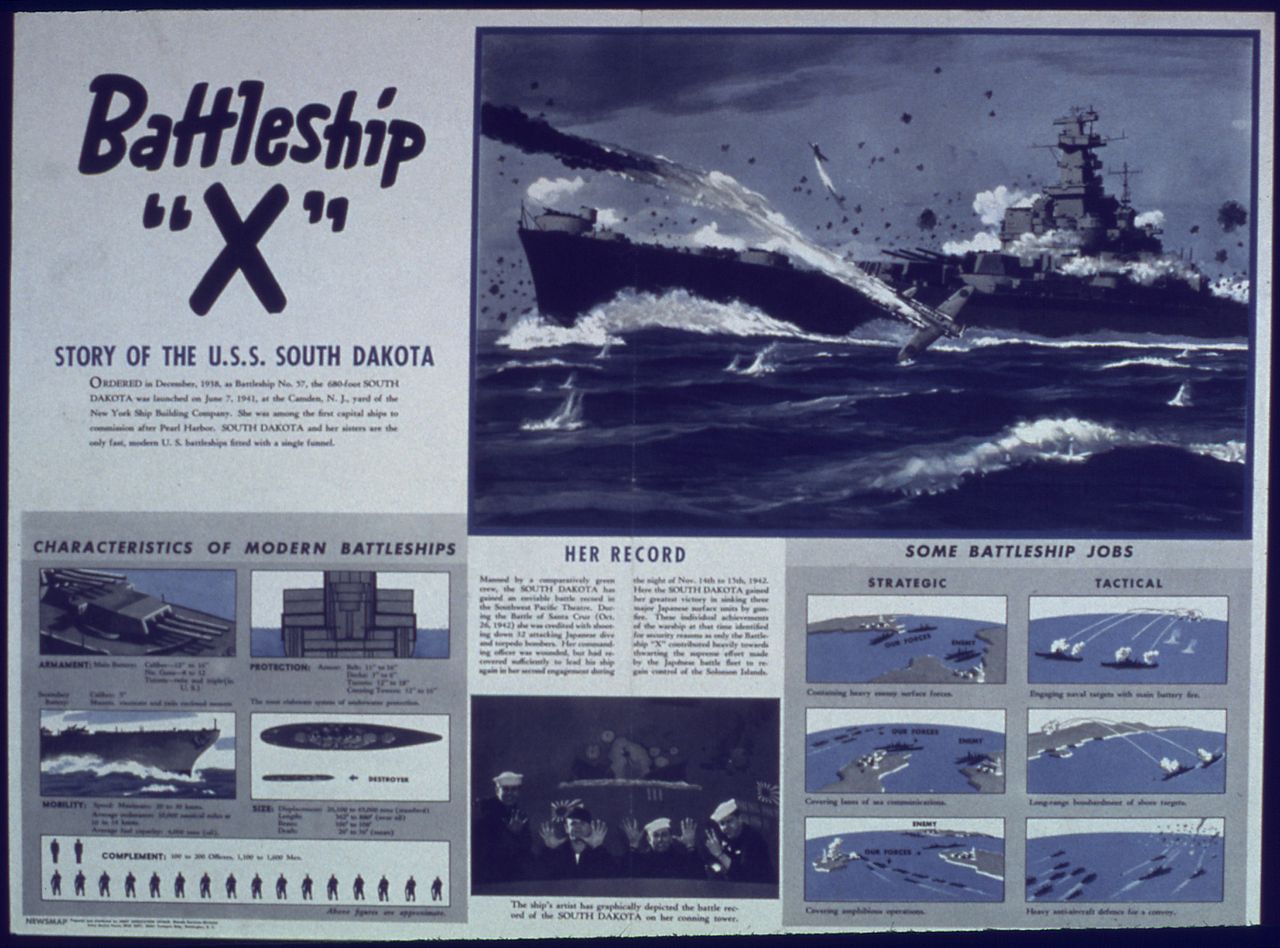

Back to Nouméa on 17 November she was repaired by USS Prometheus until 25 November and new spotter floatplanes. On 25 November she was underway to Nukuʻalofa with two destroyers, refuelked on the 27th, then proceeded to the Panama Canal, arrived there on 11 December, refueled on the Pacific side and headed for New York, through the Carribean, with another two destroyers escorting for U-Boats. From 18 December dry-dock repairs started at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, followed by a refit. The press came to laud the battleship (called “Battleship X” for satefy) for her epic fight, so much so she was credited with the victory of Guadalcanal instead of USS Washington.

Arctic service

USS South Dakota at Scapa Flow 1943

Anchored in Iceland, 24 June 1943

Captain Lynde D. McCormick took command and replaced Gatch on 1 February 1943. The battleship was back at sea on 25 February 1943, for a round of sea trials, post-refit fixes and intense training with new recruits in March, in the north Atlantic and with USS Ranger. She was assigned to reinforce the Home Fleet for the planned Allied invasion of Sicily, but she protected an Arctic supply convoy due to a strong German squadron there, with Tirpitz and Scharnhorst in Norway. She escorted TF 61 with her sister Alabama and five destroyers, departing Scapa flow on 19 May with HMS Anson and Duke of York, operating with them for three months.

Another protected convoy was done un June, and in July 1943, they were detached to make a demonstration, hopefully distracting German attention while Operation Husky took place. By late July, USS South Dakota was recalled to Norfolk escorted by five destroyers and became there RADM Edward Hanson’s BatDiv 9 flagship. This was the end of her wartime Atlantic service.

Marshall/Gilberts campaign

In Ulithi

Departing Norfolk on 21 August, she reached Efate on 14 September, Fiji on 7 November, and the rest of BatDiv 9 in support of TG 50.1 (‘Carrier Interceptor Group’). She was committed in the Gilbert and Marshall Islands campaign, with Operation Galvanic, Tarawa in November 1943. On the 19th she covered the CVs raids on Tarawa in advance. In December she fell under command of Lee’s TG 50.4 (Alabama, Washington, North Carolina) in protection of two CVs. The attack of Nauru was preceded by a reinfocement on 6 December by the two other sister ships, USS Indiana and Massachusetts, making TG 50.8. Nauru was pummeled for two days. Back to Efate preparations started and South Dakota was supplied by the William Ward Burrows on 5 January before sailing out with Indiana and for gunnery training on the 16th.

OS2U recovery in rough sea

Operation Flintlock was next (The invasion of the Marshalls), with TG 37.2, Third Fleet: She operated with her three sisters and USS Washington plus six destroyers, reaching Funafuti through Heavy seas (4 men injured, one washed overboard) and took theior protection duty of USS Bunker Hill and Monterey on the way, now renamed TF 58.8, Fifth Fleet (fast carrier task force). On 25 January, South Dakota, North Carolina, and Alabama were detached as TG 58.2.2 and reached Roi-Namur (29 January) for carriers strikes and the followuing day, USS South Dakota approached to shell the islands for the landing a day later.

After a supply run to Majuro on 4-12 February she was assiged to Operation Hailstone (Truk Raid). This wa on their way to the Mariana Islands, on 20 February. Her 5-inch gunners claimed their longest range kill on 21 February and others on 22 February. While raids on Saipan, Guam, and Tinian took place, the battleship put up a staunch AA denfence duing numerous air attack, starting on 23 February, notably by Mitsubishi G4Ms. USS South Dakota claimed two certain, one probable, when they took her as target.

Battleship “X” – The press praising USS South Dakota for “saving Guadalcanal”.

Still with USS Alabama, she made a sweep detached as TG 58.2 and were back to Majuro on 26 February, departing on 22 March for Operation Desecrate One, in the western Carolines: The carriers attacked Palau, Yap, Woleai, and Ulithi, the seaward flank to ensure landings at Hollandia, New Guinea. South Dakota joined TG 58.9, screening the main carrier task force against a possible incursion of Japanese Combined Fleet. On 27 March, three carriers from TG 36.1 joined TG 58.2, which became the 58.3 (“Mighty 58”).

BB 57’s air search radar spotted an unrecoignisable formation in the darkness, left unengaged by doubt. These were Japanese and it happened they too, failed to engage that night. On 30 March-1 April raids took place, and during an air attack, USS South Dakota engaged two waves without scoring a hit. Bad weather prevented further air operations and on 6 April, the fleet was back to Majuro, participating later to Operation Desecrate Two along the coast of New Guinea combined with a landing at Aitape.

On 19 April, USS South Dakota radar-picked up a Japanese aircraf shadowing the fleet, promtly eliminated by a CAP Hellcat. Carriers strikes were devastating on the 21st, destroying 130 aircraft and numerous ships plus installations. After another supply run at Majuro, Truk was struck again on 29-30 April and on 1 May, Lee wanted his fast battleships (with South Dakota) for a detached group called TG 58.7 to rain steel on Pohnpei. South Dakota, Indiana, and North Carolina flattened the island, briefly disengaging aftr a submarine was reported. They were back to Majuro on 4 May while South Dakota made extra shooting practice on 15–16 May.

Marianas campaign

USS South Dakota out of Puget Sound

TF 58 made a new sortie on 6 June for Operation Forager, (invasion of the Mariana Islands) and South Dakota was in TG 58.7 (RADM Lee) with six other battleships, four heavy cruisers, 13 destroyers, escorting the fast carrier strike force. The operation started on 11 June and Lee’s ships had to create an AA barrage in order to counter several Japanese counter-attacks, helped by the BBs air search radars used to vector fighters from the CAP (notably night fighters versions of the Hellcat).

USS South Dakota’s 5-inch guns the first night claimed two attackers and on 13 June, she shelled Saipan and Tinian before Adm. Oldenburg’s old battleships of the bombardment group arrived the following day. Japanese artillery was powerless to counter them and was destroyed. South Dakota concentrated around Tanapag Harbor, pouring fire for six hours straight and hitting two transports. Accuracy remained poor however due to lack of experienced with shore bombardment. In fact most defenses remained largely untouched.

On 14 June, USS South Dakota refueled her escorting destroyers, her Kingfishers away to rescue downed pilots. As Marine landed, Japanese counterattacks started, notably on 15 June, and South Dakota claimed one Kamikaze. She left the area on 17 June to meet the 1st Mobile Fleet spotted through the Philippine Sea. On 18 June, Lee and Mitscher discussed strategies and it was decided to deploy the battleships in screening mode rather than pursue the Japanese fleet in a night action.

Battle of the Philippine Sea

B6N attacking TG 38.3 during the Formosa Air Battle, October_1944

BB 57 was deployed in a 6 nautical miles (11 km; 6.9 mi) diameter circle covering a large area as they met the first IJN scouts on 19 June. South Dakota tracked these by radars until picking up the first wave incoming. This was her that warned the fleet. CAP fighters engaged the bulk of them at 10:43, and those that broke through were dealt with AA fire. A single aYokosuka D4Y dive-bomber, managed to hit South Dakota with its 500-pound (230 kg) bomb; at 10:49. It opened a 8-by-10-foot (2.4 by 3.0 m) deck gash, disabling a 40 mm mount, killing 24, wounding 27.

At 11:50, the second wave saw twenty aircraft evading the CAP and coosing targets: Two Nakajima B6N torpedo bombers attempted a launch at South Dakota, but they soon broke off. At 11:55, she was attacked again, but fierce AA fire had her unscathed. The Third and fourth waves never targeted South Dakota. The evening saw a burial at sea, after emergency repairs. On 20 June, South Dakota saw no action and she spent next days sending her floaplanes looking for downed pilots.

On 22 June she sailed east with TG 58.7, before being transferred to TG 58.2, arriving to Eniwetok on 27 June for supplying arriving there. She headed for Puget Sound via Pearl Harbor, picking up there wounded men back home. She arrived on 10 July and was dry-docked for repairs and refit, until 6 August. After loading ammunition and supplies she started post-refit Sea trials and was assigned to Task Unit 12.5.1 with two destroyers heading to Pearl Harbor on 30 August.

After gunnery exercises off Hawaii until 8 September, and replenishment she departed on the 11 for more maneuvers, developing engines issues. Divers found the blades on three propellers bent or chipped and she had to be dry docked in Pearl Harbor again until 16 September. After new training operations she joined TU 12.5.1 on 18 September in Manus Island (New Guinea), then Ulithi, the new advance base, reporting to Third Fleet

Okinawa and Formosa raids

On 3 October, the 3rd fleet narrowly escaped a typhoon in Ulithi, and BB 57 was hit by the store ship Aldebaran, drifting on her, on her port side. Damage was light and on 5 October she became once again flagship of BatDiv 9 (RADM Hanson). TF 38 sortied under Mitscher’s command to launch striked on Okinawa Islands from 10 October. The 11 had USS Iowa picking up a radar contact, confirmed by South Dakota: Fighters mived in interception and spotted a single Mitsubishi G4M “Betty” bomber, shadowing the task force.

After a feint toward the Philippines, the fleet veered toward Formosa (Taiwan) fo the first of several massive air raids, starting on 12 October. A G4M dropped chaff in order to interfere with the fleet’s search radars, mildly effective. CAP fighters intercepted three waves, many of which went through and hit the fleet: USS South Dakota started fire at 19:03 but was silent during the second wave. At 22:31, she claimed one bomber, and continue her defence until midnight.

Back to a safer position on 13 October, they still saw several waves of G4M bombers attacking. Armed with two torpedoes, they managed to hit USS Canberra. USS South Dakota also had to maneuver hard over to dodge several attacks. The carriers launched more strikes meanwhiles and protected Canberra to safety. Lookouts on South Dakota spotted seven B6Ns approaching the fleet on the 14th and claimed one.

Philippines campaign: Battle of Leyte Gulf

USS South Dakota in the ABSD6 floating drydock

The landing on Leyte on 17 October saw Operation Shō-Gō 1 launch, a complicated and clever massive gamble of a counter-attack. USS South Dakota on her part had Commodore Arleigh Burke, Mitscher’s Chief of Staff, suggesting she was detached alonh her sister Massachusetts and two light cruisers plus destroyers to foray ahead of the carriers, expecting a night action with the Japanese Northern Force. RADM Forrest Sherman commanded the detached force but Halsey intervened and overruled Mitscher. Mitscher created TF 34, with South Dakota and five fast battleships, 7 cruisers, and 18 destroyers, under Vice Admiral Lee in hot pursuit. TF 34 was depliyed ahead of the carriers as main screen.

On 25 October, morning, Mitscher spotted and attacked Northern Force (Battle off Cape Engaño) and all four carriers were sunk, as well as the hybrid carriers Ise and Hyuga badly damaged. Later took place the Battle off Samar, and time passed before Hasley agreed to detach TF 34, which progress south was further hampered by the refuelling of escorting DDs at sea. Fortunately, Taffy managed to repel Kurita well before South Dakota could arrive. Iowa and New Jersey were detached as TG 34.5 in hot pursuit, being much faster than Kurita, through the San Bernardino Strait but arrived too late.

South Dakota refueled at sea on 26 October but also refueled four destroyers the following days, disrupted on 30 October when a lone G4M appeared. On 1 November, she was reassigned to BatDiv 6, and stayed as flagship until replaced by USS Wisconsin later. She stayed in Ulithi and prepared for next operations.

China sea Operations

Underway at sea on 2 November with TG 38.1, she had to support ground forces on Leyte and was tranferred to TG 38.3 to escort four carriers attacking Luzon. She had errant AA rounds making a casualty, wounded seven during the action. South Dakota refuelled destroyers while respnelishing herself and escorted carriers launching another series of raids on 13-14 November before being back to Ulithi on the 17th. Lee being promoted as the Battleships, Pacific Fleet overall commande hoisted his mark onboard South Dakota and TG 38.3 sortied on 22 November with two fleet and two light carriers and the North Carolina-class battleships plus three cruisers, and two desron. They conducted gunnery training dung carrier strikes in the Philippines. They were back in Ulithi on 2 December.

On 11 December, TG 38.3 departed to join TF 38 attacking Mindoro. On 17 December the fleet was hit by Typhoon Cobra. South Dakota remained unscathed and she was back in Ulithi on 24 December. She accompanied a raid on Formosa on 3–4 January 1945, and later strikes on Lingayen on 6-7 January and back to the South China Sea on 10 January, attacking Formosa on 21 January, the Ryukus on the 22th.

Iwo Jima and Okinawa

By early February, the 5th Fleet and fast carrier task force was prepared for the next round of operations at Iwo Jima and Chich Jima. South Dakota was in TG 58.3 with USS New Jersey, USS Alaska and other cruisers. First, a serie of air strikes on Japan and Tokyo area (17 February) was marred byt bad weather while TG 58.3 reinforced the invasion fleet at Iwo Jima (19-22 February) and were recalled for more raids on Japan (25 February), and back to Ulithi. After another raid on Japan, Kyushu (18 March) sawe the battleships in AA escort all along. After Kure, and another refuelling, air strikes started over Okinawa. Massive kamikaze attacks started and battleships AA crew were more than ever on egde. TF 58 groups rotated between Okinawa and replenishment area but South Dakota remained again relatively unscathed.

On 19 April, South Dakota took part in a shore bombardment group to support on southern Okinawa the XXIV Army Corps. She was detached to follwon a raid on the Sakishima Islands, and was later in Leyte replenishing, before coming back for more bombadment missions on Okinawa. On 6 May while replenishing ammunition from USS Wrangell a main battery propellant tank exploded, causing chain explosions and fire. The magazine in number 2 turret was flooded promplty to avoid catastrophy by the crew. 3 were killed, 8 seriously burnt, later died, 24 were less-seriously.

After repairs at Ulithi on 13 May, BB 57 joined back TG 58.4 on the 14th, but was inspected in drydock ABSD-3 showiong that her propellers, shafts, and strut bearings were in pretty bad shape, requiring more repairs until 27 May when she rejoined the 3rd Fleet but started anti-submarine training with two destroyers, main battery and AA practice, night combat for a wee, in the Philippine Sea and Leyte Gulf. Reassigned to TG 38.1 (16 June) as flagship, RADM John F. Shafroth Jr. she did more AA training until 24 June.

Bombardments of Japan

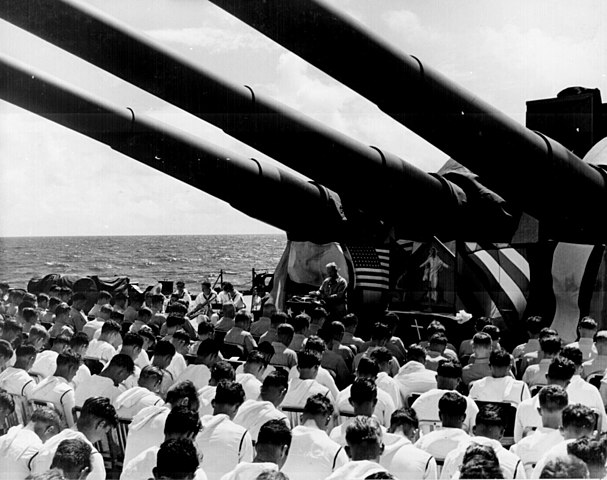

Bombardment of Kamaishi, Japan 14 July 1945

In preparations for Operation Olympic, landing on Kyushu, TF 38 started a campaign of strikes on the mainland in july-August. While en route, USS South Dakota refuelled her destroyers until arriving on 10 July. While air raids took place, South Dakota was assigned to TU 38.8.1, a bombardment group also comprising USS Indiana and Massachusetts plus two heavy cruisers, sent to shell Kamaishi and its Steel Works. The mountainous terrain there however made targeting difficult. But this was the first time US capital ships directly bombarded the mainland. After six passes, it was estmmated 2.5 month interruption in coke production and pig iron was realized.

TF 38 covered them at their returned during air strikes on Honshu and Hokkaido (15 July). Later they started to operate with the British Pacific Fleet, aliging several battleships of the King Georges V and the French Richelieu, although the latter mostly operated closer to Burma-Malaya. All combined hit Tokyo on 17 July and on 20-22 July USS South Dakota replenished an rejoined the carriers on 24-28 July, then TU 38.8.1 was re-formed (29 July) to shell Hamamatsu (South Dakota, Indiana, Massachusetts and the British TU 37.1.2 (King George V) and air cover by USS Bon Homme Richard. The shelling started in the night of 29 July until the 30th.

They withdrew with South Dakota in the lead, the TF was dissolved and she was back to TG 38.1 to cover air strikes on Tokyo-Nagoya. They all escaped a typhoon on 31 July-1 August also. After refuelling on 3 August she accompanied the carriers for more strikes, and South Dakota was in TU 34.8.1 for a third bombardment (9 August) with six Allied cruisers and destroyers on Kamaishi. Back to TG 38.1 she supported carriers on the 10th but Shafroth transferred his flag to Alabama on 12 August, South Dakota being reassigned to TG 38.3 for a fourth bombardment when new arrived on 15 August of the cessations of hostilities (see above for the rest of her records). For her service, she won 13 battle stars, the most decorated battleship of WW2.

USS Indiana (BB 58)

USS Indiana (BB 58)

USS Indiana 1942

After sea trials in the Chesapeake Bay from 26 to 29 May 1942 and fitting out she departed for Hampton Roads, made last trials on 1st June escorted by DDs USS Charles F. Hughes, Hilary P. Jones, Ingraham, and Woolsey. This was followed by gunnery training and exercises until September before departure for Casco Bay, Maine and more gunnery training. On 9 November she departed for the Panama Canal that day learning the US was at war.

On 14 November, USS Indiana became flagship of Task Group (TG) 2.6, (also USS Columbia, DDs USS Haven, Saufley), proceeding to Tonga on 28 November and transferred to TG 66.6, then heading south to Nouméa (2 December). After combined exercises with TF 64 she replaced USS South Dakota, badly damaged at Guadalcanal, and providing gunfire support there.

By January 1943, she was joined by USS North Carolina and Washington as TF 64 (RADM Willis Lee), covering reinforcement convoys. At some point they covered seven transports with the 25th Infantry Division to Guadalcanal ladnded on 4 January. Being too south for another escort, she missed the Battle of Rennell Island. But she ws detached to taked part to the invasion of New Georgia with Indiana, North Carolina, and Massachusetts, flanking the fleet.

The Marshalls

USS Indiana in a South Pacific harbor

She covered a raid on Marcus Island on on 1 September and was sent to particopate to the invasion of Tarawa on 20–23 November as part of the AA screen of TG 50.2 off Makin Atoll (USS Enterprise, Belleau Wood, Monterey) and her crews claimed their first kill. On 8 December with four other BBs she shelled Nauru: 810 16-inch shells being landed on various Japanese installations. On 1st January 1944, USS Indiana joined TG 37.2, and after gunnery practice with USS South Dakota, later joined by North Carolina, Washington 18 January she sailed to take part in the Marshall Islands campaign.

There, she joined USS Bunker Hill and Monterey at Funafuti on 20 January (TG 58.1) and later joined by USS Enterprise, Yorktown, Belleau Wood, and several more cruisers and destroyers. Further training took place from 25 to 28 January, including more AA practice and she served as target for simulated air attacks, coming from air groups, and flagship of Battleship Division 8 (Rear Admiral Glenn B. Davis). By late January, she prepared for the invasion of Kwajalein, Marshalls.

On 29 January she shelled Maloelap Atoll with USS Washington, coordinated with the Enterprise and Yorktown, and Kwajalein the followung days with Massachusetts and four destroyers, Indiana opening fire at 09:56 on the 31. They sank a submarine chaser and five guard ships and silenced artillery batteries. Unline other vessels, Indiana was not hit by them initially. The bombardment stopped at 14:48 and they departed to join the carriers, having spent 306 main shells, 2,385 secondaries.

She stayed as escort overnight but on 1 February, collided with Washington, being blacked out to prevent Japanese potting. Indiana turned in front of Washington while moving, and spotted the later too late in this moonless, covered night. Indiana was badly damaged, loosing her starboard propeller shaft, her belt armor and torpedo bulkhead mushed and penetrated by Washington. 200 ft (61 m) of armor plating needed repalcement, while Washington had a 20 ft (6.1 m) bow section ripped away, kept in Indiana’s side. 3 were killed, 6 injured aboard Indian. The inquiry later put the blame on Indiana as the captain failed to indicate other vessel her course change.

RADM Davis transferred his flag elsewhere while Indiana departed the folloing day for Majuro. Patched, she sailed to Pearl Harbor on 7 February with UDD Remey and Burden R. Hastings. They arrived on 13 February and she was dry-docked until 7 April. After sea trials, main battery tests for two weeks she was returning for next operations in the central Pacific: The Marianas.

Marianas campaign

USS Indiana at Pearl Harbor on 13 February 1944 after her collision with USS Washington

Indiana arrived in Seeadler Harbor (Manus Island) on 26 April, Davis coming back to make her his flagship, and she was underway with Massachusetts and four destroyers, assigned to TF 58 for Operation Hailstone, on Truk Atoll. On 1st May, she bombarded Pohnpei (Senyavin Islands) for an hour and on the 4th, she resupplied in Majuro, being at sea after peparations and training on 6 June, set for the invasion of Saipan. She sailed with Washington and four destroyers (TU 58.7.3) for the Western Bombardment Unit and on 13 June she fired 584 shells over two days from her main battery.

On 15 June, she repelled a Japanese air strike, doing evasive maneuvers to avoid both torpedo and dive bombers, one torpedo hitting her around 19:10, but failed to detonate. Her AA crew claimed two and controbuted others. She remained on station until warning came that the 1st Mobile Fleet was enroute, which led to the Battle of the Philippine Sea on 19-20 June 1944, in which USS Indiana and South Dakota, which reported the initial wave, started at 10:48 while starting evasive maneuvers at 11:50 due to torpedo bomber attacks. One torpedo exploded in her wake.

Her crew claimed a Zero at 12:13, but a burning Nakajima B5N2 eventally crashed into her starboard side. Not damaged she remained on station while fires were extinguished. In total she spent 416 shells from her 5-in guns and 4,832 40 mm plus 9,000 20 mm guns rounds, suffered five dead and a dozen injured, many by shell fragments from other ships AA guns, a “blue on blue fall”.

USS Indiana underway in 1944

On 4 July 1944, her Kingfishers started as SAR mission, picking up stranded pilots at sea, like those from USS Lexington. In early August she was detached to Eniwetok, replenishing and went back on 30 August to join TF 34 as part of TG 38 on 3 September for the Palau Islands campaign. But soon she developed turbines problems and instead went to Seeadler Harbor for repairs, until 4 October. Davis chosed USS Massachusetts as flagship meanwhile. USS Indiana joined USS Idaho, the cruisers USS Indianapolis and Cleveland while going to Pearl Harbor, arriving on 14 October, and then Puget Sound Navy Yard for her major wartime overhaul completed on 30 November 1944. After sea trials, she departed on 6 December for Pearl Harbor, and after training exercises she proceeded on January 1945 to the Pacific for her last campaigns.

Battles of Iwo Jima and Okinawa

Under orders of RADM Oscar C. Badger II at the head of TU 12.5.2, she was flagship again from 8 January 1945. She departed Pearl with USS Borie and Gwin to Eniwetok, refuelling, and from there to Saipan, joining her unit on 20 January. They set sail for Iwo Jima on 22 January and there BB 58 joined three heavy cruisers, seven destroyers, while her sailor USS Gwin shelled the island a firest time. At 13:17, a lone Nakajima B6N attacked them but was driven off by AA. During the bombardment, the battleship spent 200 main shells, but soon stopped due to poor visibility and she left the area for Ulithi (26 January) while RADM Badger transferred his mark to USS New Jersey. Meanwhile, Indiana spent the rest of January in anti-aircraft training.

She was back on 10 February reassigned to TG 58.1 for a raid on Tokyo, ecorting carriers for their attack on 16 February, including the Bonin Islands and Iwo Jima, or the Tokyo area. Indiana as always sent her Kingfishers for SAR missions all day long. They were back to Ulithi on 3 March and underway back on 14 March. Indiana operated with South Dakota, Massachusetts, North Carolina, and Washington as TU 58.1.3. Three days later there were new carrier strikes and her AA gunners claimed an aircraft on 19 March. Kyushu was targeted, Kure. But firced attacks got Wasp and Franklin and the unit withdrawn.

Caught in a typhoon off Okinawa, 5 June 1945