USA (1893): USS Indiana, Oregon, Massachusetts

USA (1893): USS Indiana, Oregon, MassachusettsWW1 US Battleships:

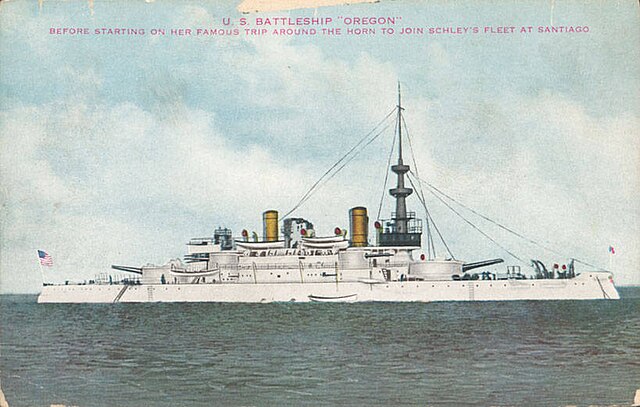

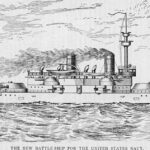

USS Maine | USS Texas | Indiana class | USS Iowa | Kearsage class | Illinois class | Maine class | Virginia class | Connecticut class | Mississippi class | South Carolina class | Delaware class | Florida class | Arkansas class | New York class | Nevada class | Pennsylvania class | New Mexico class | Tennessee class | Colorado class | South Dakota class | Lexington classThe Indiana class were three pre-dreadnought, ratehr coastal battleships planned in 1889 and launched in 1893. They were the first comparable to European standards like the British HMS Hood, and were commissioned in 1895-1896, pioneering the use of a strong intermediate battery. Of low freeboard their turrets lacked counterweights, and the main belt was too low to be effective, but they were a brave first attemps, retrospectively at the very start of the long US Navy battleship tree, BB-1, 2 and 3 USS Indiana, Massachusetts, and Oregon. All saw limited action in the Spanish–American War, USS Oregon making the round the cape (14,000 nautical miles) trip to reach the East Coast in this pre-panama era and did the reverse postwar, seeing action in the Philippine–American War, Boxer Rebellion, her sisters training with the new Atlantic fleet. After 1903, they saw limited activity, being relegated to training, albeit Oregon took part in the 1919 Siberian Intervention. All three were decommisson in 1919, two ended as targets, Oregon was initially preserved as a museum, but after being sold for BU became an ammunition barge and took part in the 1942 battle of Guam and survived the pacific war. She was finally sold for BU in… 1956.

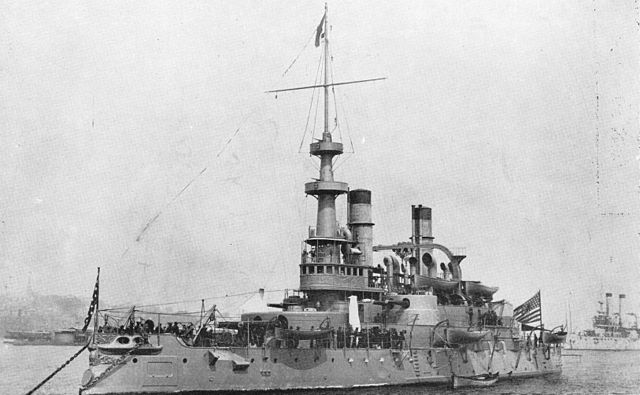

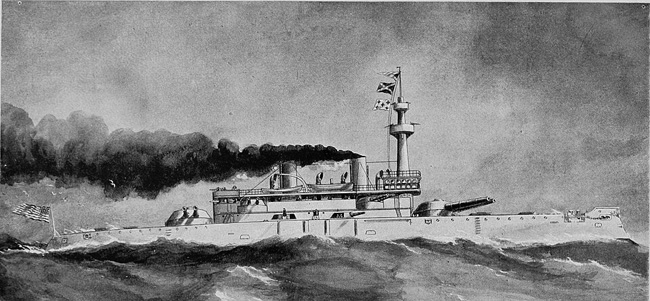

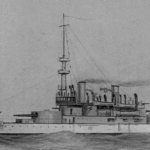

USS Indiana after 1898, in grey livery.

Development

The first US battleship class:

In 1890 there was a transition between the “old navy” inherited from the secession war, and a “new navy” born from a new naval thinking such as those of Alfred T Mahan. The lack of experience in high seas battleships (the last one was the monitor USS Dictator, back to 1863) meant US navy policy board started working in stages, notably after the Brazilians in 1883 acquired two modern British-built battleships (The Riachuelo class). In 1889, plans were made for a limited serie of coastal, short range battleships after USS Texas and USS Maine (the latter reclassified as an armoured cruiser), semi-experimental ships mainly intended to giving US shipyard experience, it was time to look after a new, true battleship class comparable to European standards.

After BB-1 (Battleship 1) was the very first piece of a new ambitious naval construction plan aiming at delivering 33 battleships and 167 smaller ships for the US Navy the United States Congress was now seeing debating still on an attempt to end the isolationist policy ruling US foreign relations since the end of the civil war. This led to refuse the funding on a new design a year, but accepted the next year a proposal for three “coast defense” battleships, a step towards proper sea going battleships, of which USS Indiana was the lead ship.

This design was very much a measure to ease Congress vote rather than a design was really pleased the Navy. It was a compromise for moderate endurance, relatively small displacement and low freeboard but ended as a ship under-protected and under-armed compared to European equivalents and as Conways put it: “attempting too much on a very limited displacement.” The problem was two close copies were built.

Congress Controversy

The start of the Indiana class, first proper, modern US Battleships, was rocked by contraditory opinions in the Congress, which ultimately led to a compromise that satisfied few and left the USN with battleships of limited use in 1896, when the last was completed. The Indiana class was indeed very controversial at the time of its approval.

Tracy’s Grand Battlefleet

The impetus started from the Navy, with a policy board convened by the Secretary of the Navy Benjamin F. Tracy which was one of the enthusiasts around the idea of a US battle fleet, at least superior to the next two South American naval powers combined, and rivalling those of Europe, at least on the east coast.

The ambitious 15-year naval construction program was approved on 16 July 1889, three years after USS Maine and Texas just authorized to test battleship construction at home. This plan included no less than ten first-rate, long-range, sea going battleships capable of 17 knots (31 km/h; 20 mph) and 5,400 nmi (10,000 km; 6,200 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph)—6,500 nmi (12,000 km; 7,500 mi) maximum, giving them reach down to the cape Horn. They were clearly instruments of a fleet in being, capable of raiding European ports in case of war across the Atlantic, or deter enemy batleships far from home (and thwart any attempt at a blockade).

In addition to these ten sea going battleships, there were planned a total of no less than twenty-five short-range second-rate battleships to provide home defense, both in the Atlantic and Pacific seaboard. In case a war happened and the main battlefleed was closer to home, they could support them, given their range of roughly 2,700 nmi (5,000 km; 3,100 mi) at 10 knots, lighter draft of 23.5 ft (7.2 m), to make it possible an intervention into the St. Lawrence River or north to the Windward Islands and Panama, and enter all southern coast ports, short of going up the Mississippi river.

Cost reasons however were discussed and approaching the Congress with this plans led many to look for a hierarchy of three subclasses instead:

-8 Sea Going BBs: 4x 13-inch (330 mm) guns armed, 8,000-long-ton (8,100 t; 9,000-short-ton)

-10 Median BBs: 4x 12-inch (305 mm) guns each, 7,150-long-ton (7,260 t; 8,010-short-ton)

-5 coastal BBs: 2x 12-inch, 2x 10-inch (254 mm) guns each, 6,000-long-ton (6,100 t; 6,700-short-ton).

Speed would likely loose a knot as well as c500 nm or more range for each.

The two battleships already under construction, USS Texas and Maine, were conveniently placed in to the 3rd class, leaving three more to built.

The fleet of 167 smaller ships that was planned included ram and cruisers, torpedo boats, in the French “Jene Ecole” style, bringing the total cost of $281.55 million, which was the entire US Navy budget until then over 15 years ($6.6 billion in 2009).

Congress Reception

The Congress balked at this plan (as expected). A large faction saw it as putting an end to the United States isolationism policy since the civil war, and even the start of imperialism. The reaction was so vivid even die-hard supporters of this naval expansion plans were wary of a complete ban on battleships altogether. Sympathetic Senator Eugene Hale notably stated to the Navy the proposal was so large that the entire bill will be rejected, on top of having no dunds alloted to the Navy for any new ship altogether. The Navy plan was indeed almost an outrage for many indeed, notably inland and poorer states that had understandably more interest to fund their own development rather than enterprises that would “bankupt america in the name of imperialism”. Others stateed it was a plain betrayal of the founding father’s ideals. 1889 ended without any major funds allocated as feared.

By April 1890, the other house, the one of Representatives approved however funding for three 8,000-long ton battleships after tractations and mirroring contracts for their own local industries, to which representatives were more receptive. Based on this approval, Tracy, returned to the Congress, trying to soothe tensions and promoted these three battleships as “so powerful only twelve would be necessary” instead of 35 and slashed the Navy operating costs altogether by proposed the scrapping of remaining Civil War-era monitors operated by militias. This effort was fruitful as a majority in the senate approved the appropriation making for a total three coast-defense battleships in the immediate years, what became the Indiana class. Instead of the fleet of 167 smaller ships, a cruiser, and a single torpedo boat (part of the “medium group”) were also approved, all funded on 30 June 1890. This was not a clear-cut for the Navy though.

Final Specs

This was a greenlight for the Navy to complete the specifificatons of the first class of short-range battleships envisioned by the policy board, not th sea-going ones. They were to mount 13-inch/35 caliber main gun and introduce for a first time, looing at European designs, a seocndary battery of 5-inch (127 mm) guns. It was greeed to give them a very good protection with a 17 in (432 mm) belt, 2.75 in (70 mm) for the deck armor, 4 in (102 mm) for the secondary guns casemates. However as the design progressed in detail, and construction proceeded, USS Indiana happened to be 25 percent heavier than anciticipated, causing serious issues notably for the armour scheme. In between the design had been revised to include indeed an even larger, 18-inch (457 mm) belt, a secondary battery mixing 8-inch (203 mm) and 6-inch (152 mm) guns as the Bureau of Ordnance could not make ready the new QF 5-inch guns in time. This made the final design slower firing and much heavier. Still, none of these guns would be able to penetrate the armour of foreign battleships, but at least they would resist heavy fire. That level of proction was indeed a match for any battleship at the time, but this was all on paper. The truth was revealed after their entered service, quite overweight.

Construction

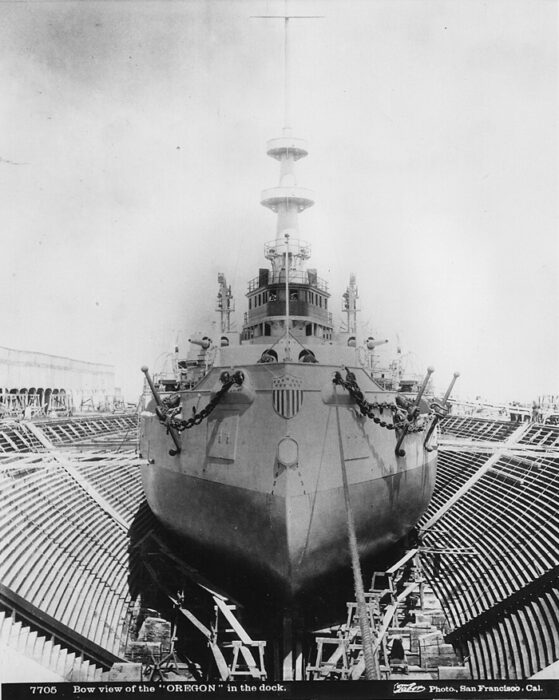

The Navy passed the ordered on 30 June 1890, right after Congress approval, to William Cramp & Sons in Philadelphia for $3 million for the lead ship, USS Indiana. But delays and still some inexperience led to a final cost that was double, at $6 million in the end. Slow delivery of armour plates delayed completion by a full year in addition. USS Indiana was launched only on 28 February 1893 and completed only 20 November 1895, six years after the design was first drawn, and already obsolete. Still, since this new ship marked the start of the most ambitious USN endeavour so far, the launching ceremony was an event attended by 10,000 including President Benjamin Harrison, members of the congress and Indiana state representatives. USS Indiana sea trials began in March 1895, in ideal conditions for performances: Side armor, guns, turrets and conning tower has not been installed yet. She thus would have a new serie of sea trials, fully loaded this time, on October. The programming of two sister ships FY1891 and FY1892 was a victory, albeit a bitter-sweet one for the USN.

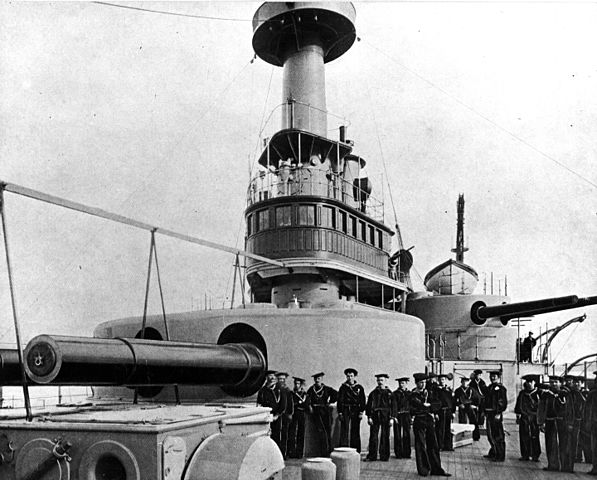

USS Indiana forecastle, showing the original heavy mast, later replace by a cage mast.

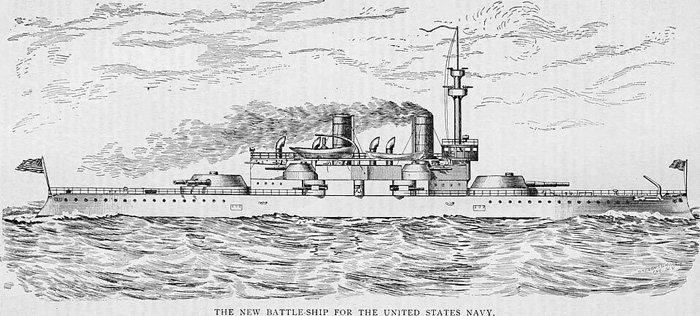

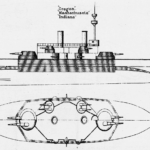

Indiana’s design

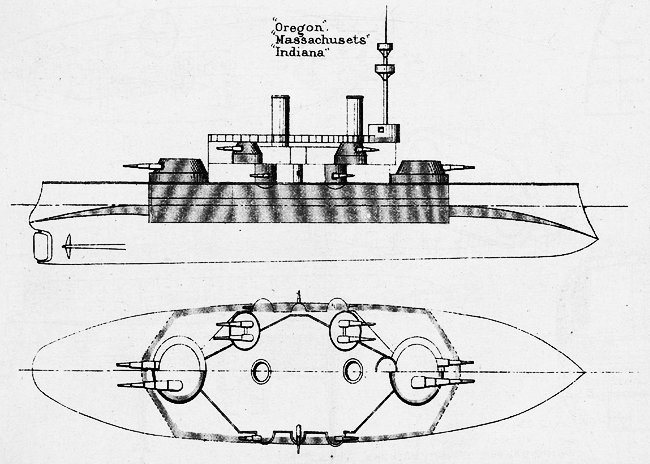

The Indiana-class were indeed designed for coastal defense, not to project power abroard. This was reflected reflected in limited coal endurance, relatively small displacement still, and expecially low freeboard, limiting seagoing capability. However, they were heavily armed and armored, so much in fact that Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships describes them as “attempting too much on a very limited displacement.”, resembling the British battleship HMS Hood, but 60 ft (18 m) shorter. Their intermediate battery of eight 8-inch guns was unlike any European ships making for a final, very respectable amount of firepower and being ‘almost’ forerunners of semi-dreadnoughts (less the speed and range), at the very end of the pre-dreadnought development.

The original design included bilge keels, but they would not fit due to the limited space in US drydocks at the time, and thus omitted during construction. This meant stability dropped sharply when in sea trials. The problem wazs particularly acute for USS Indiana, as in heavy seas both main turrets broke loose from their clamps as they were were not centrally balanced, swinging from side to side with the motion. The crew managed to secured them with heavy ropes until she was back in port. In bad weather four months later, the situation repeated and the USN ordered bilge keels to be installed on all three ships as soon as a drydock was large enough for it.

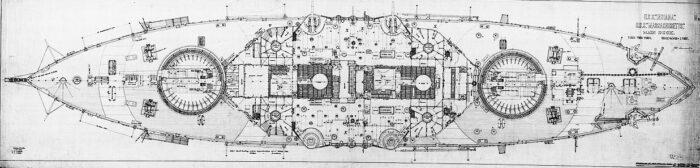

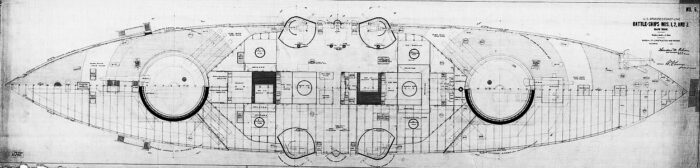

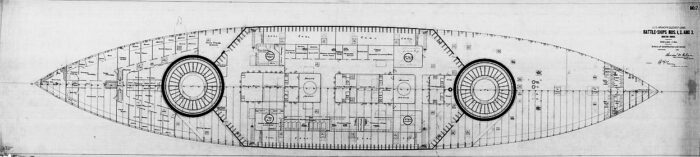

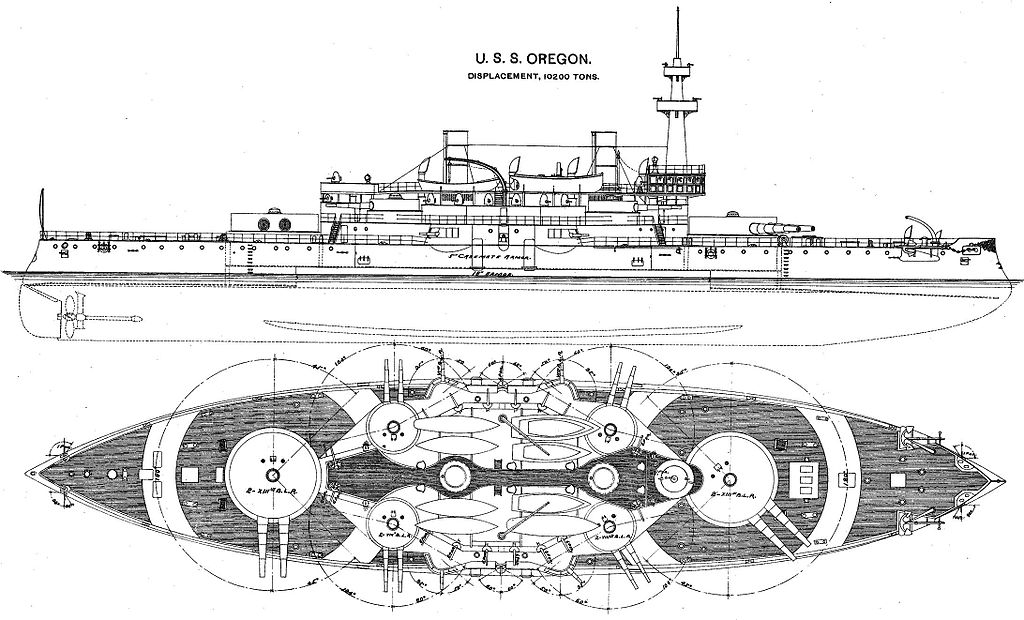

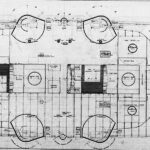

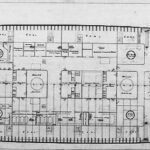

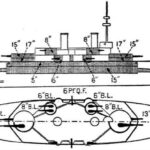

Hull & General Layout

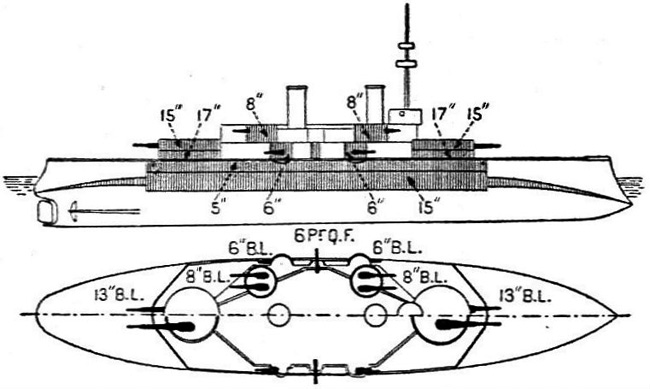

USS Indiana was a typical pre-dreadnought with her two main turrets fore and aft, central island bristling with turrets, barbettes, lighter guns under masks, military mast and tall funnels. The hull emphasized lateral protection, had a ram but due to being overweight, a low freeboard and in the North Atlantic, a wet bridge at all times. USS Indiana displaced 10,288 long tons (10,453 t), for a Length of 350 ft 11 in (106.96 m) overall and 358 ft (109 m) at the waterline, a beam of 69 ft 3 in (21.11 m) and 27 ft (8.2 m) of draft and had a complement of 32 officers and 441 men.

Her general layout was very different of Texas and Maine, which were flush-deck hulls built around their barbettes placed in echelon, centrally mounted. This gave them a slightly better balance. Instead the fore and aft turrets of the Indiana class and beeffed up structures with casemated guns was something entirely new. A simple look at the central “citadel” showed topweight aplenty with the heavier 8-in guns in high up twin turrets, and the 6-in guns lower in casemates. However the hull was devoid of any casemated guns, which was sound, as no guns placed here would be ever anything but “wet” and unusable most of the time, or even a flooding hazard.

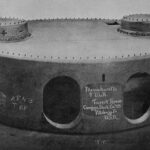

Armour

Gunnery tests in Bethlehem Belt Armour

13-inch gun battery: (Harvey) 15 in (380 mm) turret, 17-inch (430 mm) barbettes

8-inch turrets: conventional nickel steel, 6-in turrets, 8-in barbettes

conning tower: conventional nickel steel, 10 inches thick

Main belt: Harvey armor 18 in (457 mm) on 2/3 lenght +3 ft (0.91 m), -1 ft (0.30 m) waterline

Tapering down to 4 ft 3 in (1.30 m) under the waterline, at 8.5 in (220 mm).

ASW protection: Below the belt, no armor but double bottom, no compartimentation except the usual utilitarian design and compartments filled with compressed cellulose above the waterline

Armored bulkheads (Harvey): 14-inch (360 mm)

Above belt to the weather deck: 5-inch armor streay.

Deck armor: 2.75 in (70 mm) inside the citadel, 3 in (76 mm) outside.

Casemates (6-inch guns): 5 inches

Lightly armor for all the rest.

The placement of the belt armor based on the initial draft was 24 feet (7.3 m) on normal load of 400 long tons of coal on board but full capacity was 1,600 long tons and when it was, the draft increased of 27 feet (8.2 m), submerging entirely the armor belt, not a good prospect. Since fully loaded service was the norm, their main armour was almost useless. This outraged the Walker policy board which in 1896 when evaluate the existing USN battleships, proposed the design for the new Illinois-class as a standard designed to be effective with their full coal and ammunition load or at least at2/3 max capacity for this to never happen again.

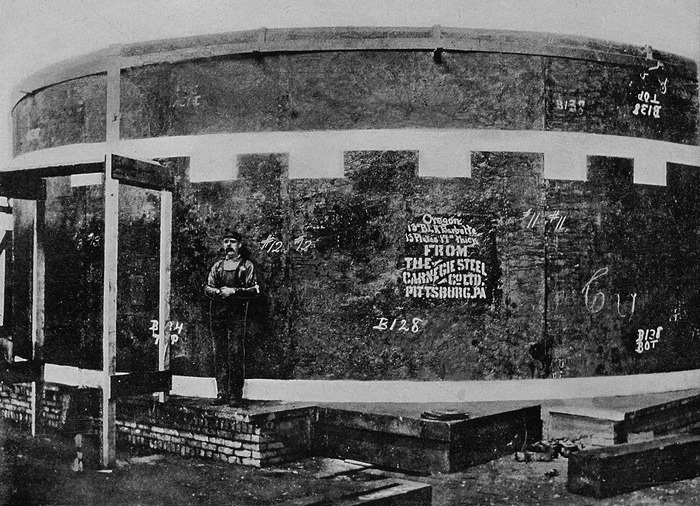

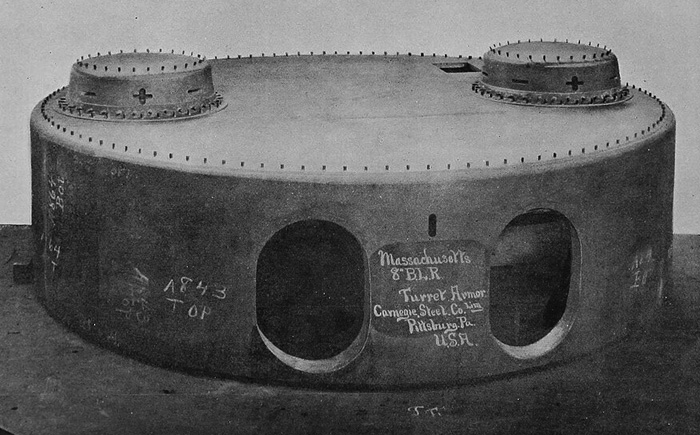

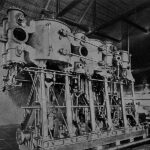

Turrets manufactured

Powerplant

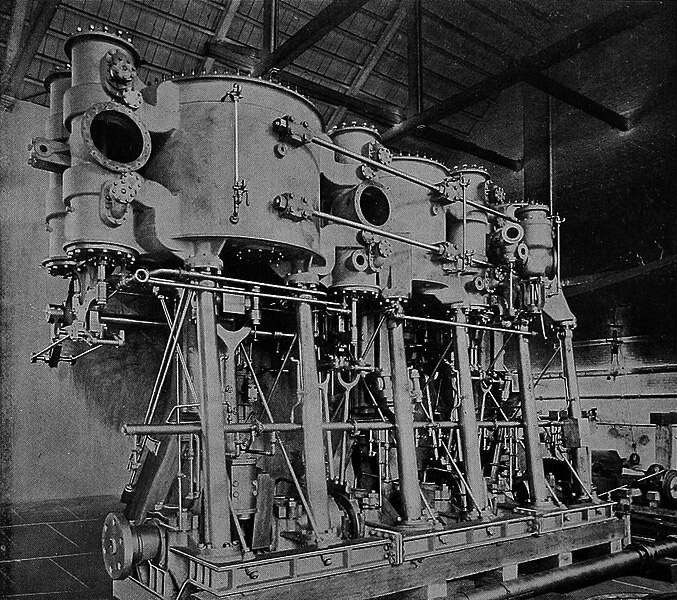

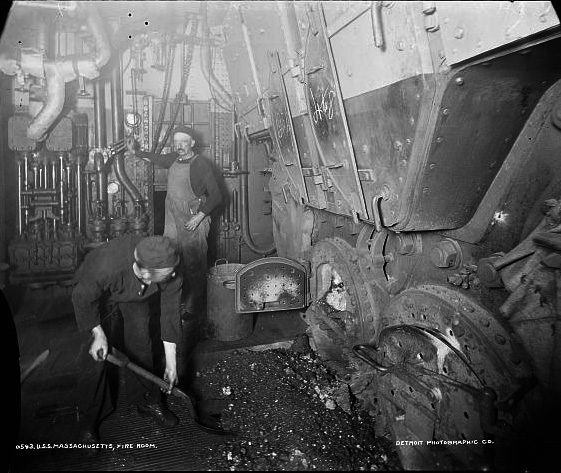

The three battleships were given the same two vertical inverted triple expansion reciprocating steam engines (TER). They were fed with the steam coming from four double-ended Scotch boilers, a power that was passed on their two four-bladed large bronze propellers at low-rev. In addition steam was provided by two single-ended Scotch boilers for auxiliary machinery. Total output as contracted was 9,000 indicated horsepower (6,700 kW), for a top speed of 15 knots (28 km/h; 17 mph).

During sea trials in which USS Indiana carried little coal, ammunition and supplies on board, both indicated horsepower and top speed, without surprise, exceeded design values. On time, all three ships were first trialled the same way and exhibited significant variation between them:

-USS Indiana delivered 9,700 ihp (7,200 kW), and 15.6 kn (28.9 km/h; 18.0 mph).

-USS Massachusetts reached 10,400 ihp (7,800 kW) for 16.2 kn (30.0 km/h; 18.6 mph)

-USS Oregon was the most powerful, at 11,000 ihp (8,200 kW) for 16.8 kn (31.1 km/h; 19.3 mph).

Modifications:

The latter had later Eight Babcock & Wilcox boilers, and four with superheaters installed in 1904 and on Massachusetts in 1907 as their Scotch boilers were seen as an obsolete tech. This profited to their top speed figures.

Armament

Indiana’s main armament comprised two twin 13 in (330 mm)/35 caliber guns, brand new ordnance tailored for this class, in addition to four twin 8 in (203 mm)/35 cal guns, four 6 in (152 mm)/40 cal guns (removed 1908), twelve 3 in (76 mm)/50 cal guns (added 1910), twenty 6-pounder 57 mm (2.2 in) guns, six 1-pounder 37 mm (1.5 in) guns, and four 18 inch (450 mm) torpedo tubes. Protection was made of Harveyized steel with a belt 18–8.5 in (460–220 mm) strong, turrets 15 in (380 mm) thick, 5 in (130 mm) on the hull. Conventional nickel-steel was also used on the conning tower (10 in (250 mm)), secondary turrets (6 in (150 mm)) and the deck: 3 in (76 mm).

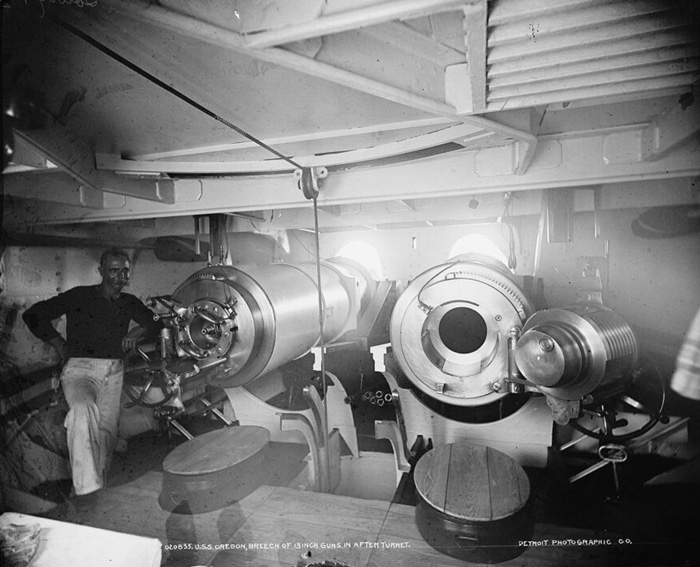

2×2 13-in/35 Mark I

The 13-inch guns were 35 calibers long, using black powder, for a range of about 12,000 yards (11,000 m) at 15 degrees elevation.

It was tested on armour plated, and was capable from 6,000 yards (5,500 m) to penetrate 10–12 inches (250–300 mm) of belt armor.

These four guns were in two centerline turrets like all pre-dreadnoughts fore and aft of the main structure.

The turrets were originally featuring sloping armor, but space requirements imposed larger rings, which were forebidden due to tonnage limits. So they ended with less effective flat sides. Fortunately, this was done for the next Illinois-class battleships. They also lacked a central spine and were simply put to rest by gravity on a ringe, with rollers, manually traverse.

Worst still, there was counterweight to offset the weight of the gun barrels, and they followed the moves of the ships.

Low freeboard in rough weather conditions, saw deck awash and seaspray just blinded these guns.

Maximum elevation was just 5 degrees due to the mounts limitations. It was considered in 1901 to replace thrse by new balanced turrets but rejected as too costly when the ships were considered obsolescent. Counterweights were added though. The turrets were also now powered by electric motors with new sights and hoists on USS Indiana and Massachusetts, increasing their reloading speed. See also: on navweaps.com 13-in/35 mk1

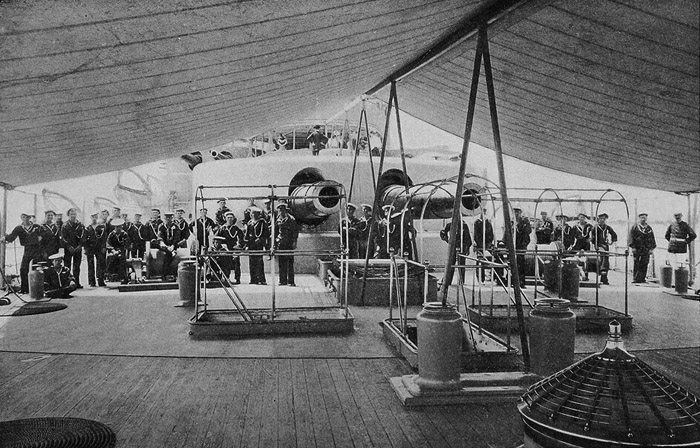

2×2 8-inches /35 Mark 5

The 8-in Mark 5 (203 mm) were the last iteration of a model that existed since 1889. It was designed for the Indiana class, with 24 barrels forged in total (Nos. 84–107).

The eight 8-inch guns were mounted in pairs, in four wing turrets relatively high on the superstructure. Their arc of fire was limited artifiaccy to avoid gun blasts oin the nearby structure. It was feared that adjacent gun positions and superstructure would suffer from their muzzle blast and that was the case also for the 13-inch guns if close enough from the structure. Over time however these turrets were modernized, wit new hydraulic rammers and turning mechanisms for the turrets, new sights and hoists however.

Weight: 40,151 lb (18,212 kg) without breech and 40,621 lb (18,425 kg) with breech

Dimensions: 28 ft 7 in (8.71 m) in lenght, 27 ft 10 in (8.48 m) bore (40 calibers).

Elevation: −4° to +13°, respective traverse, see picture.

Muzzle Velocity: 2,500 ft/s (760 m/s)

Effective range: c10,000 yd (9,140 m) at 13° elevation

6x 6-in/40 Mark 4

The smaller, but ver recent (1896) 6-inch guns were mounted in twin wing casemates, amidships on the main deck level, with a single 6-pounder gun in between.

On all three, they were mounted on central-pivot with a mask. Production of the Mark 4 went on to equip also the Illinois class and Cincinnati class cruisers.

Specs:

Mass: 13,370 lb (6,060 kg) (without breech)

Length Mod 0: 256.1 in (6,500 mm), Barrel 240 in (6,100 mm) bore (40 calibers)

Shell: 105 lb (48 kg) naval AP, 6 in (152 mm)

Traverse: −150° to +150°

Rate of fire: 1.5 rounds per minute

Muzzle velocity: 2,150 ft/s (660 m/s)

Effective range: 9,000 yd (8,200 m) at 15.3° elevation

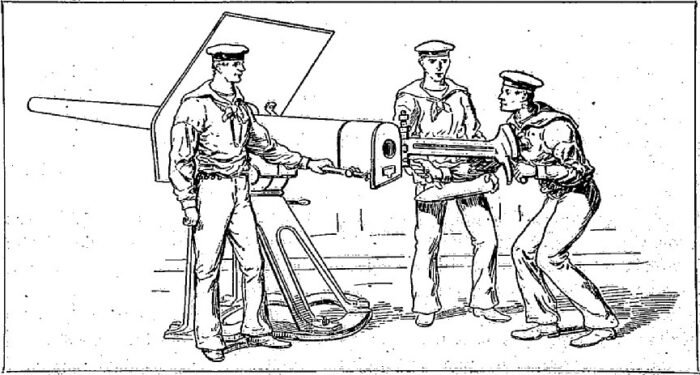

20x 6-pdr guns, 4x 1-pdr

The twenty Hotchkiss 6-pounders lined the superstructure and bridge decks. These classic Hotchkiss guns, exported all over the world, dated back from a 1885 design and were shoulder operated by a single man with assistant loaders. They had light flat shields as well.

Specs

Length: 8.1 ft (2.5 m), barrel 7.4 ft (2.3 m) 40 calibre

Shell: 57x307R or 57-millimetre (2.244 in)

Breech: Vertical sliding-block, Hydro-spring recoil.

Elevation, mount dependent, c20°.

Rate of fire: 25/minute

Muzzle velocity: 1,818 fps (554 m/s), effective range: 4,000 yards (3,700 m)

This was completemented by six 1-pounders (37 mm or 1.5 inches), four placed in hull casemates at the bow and stern, two more in the masts fighting tops.

Torpedo Tubes

Sources conflicts on torpedo tubes originally included in design, they were located on the berth deck, in above-water ports forward and aft, then midships in a lozenge pattern as most often the case, between four and six. They were located too close to the waterline and vulnerable to gunfire when opened. Later they were considered useless reduced in number, then removed before 1908. Probably fired the first model of Bliss-Leavitt models derived from the Whitehead Mark 1.

Modifications

In 1908, all 6-inch, most of the lighter guns were removed as counterweights were added to the main battery and to boot the ammunition supply.

In 1909, twelve 3-inch (76 mm)/50-caliber single-purpose guns were added midships and fighting tops, replacing the 1 and 6-pdr.

In 1918 a proposal to reline 50-caliber 14-inch (356 mm) main barrels as 98-caliber 9-inch (229 mm) guns was envisioned, with a preliminary design completed in October for service in mid-1919 but the war ended and instead thus became a limited test program for long-range guns by the Bureau of Ordnance. A 7-inch (178 mm) became a 3 inches as a proof of concept in 1922.

Oregon and Massachusetts design differences

USS Indiana (BB

USS Massachusetts was laid sown also at William Cramp and Sons, in the second slip, one month later Indiana in June 1891. She was launched 10 June 1893 and completed 10 June 1896, the delay being the delivery of armor plates. The two were very close (same blueprints) and at the exterior, only the funnel’s height betrayed these. An interesting fact was the belt armor design was based on the designed draft, 24 feet (7.3 m) with a normal load of 400 long tons of coal on board. However it appeared that with additional weight and coal this would increase to 27 feet (8.2 m), submerging the armor belt, making it useless.

The load of coal was taken in consideration in the next Illinois design by Walker policy board. The two ships had the same engine room but eight Babcock boilers including four superheaters were added in 1907 to replace older Scotch models on Massachusetts. She had a top speed of 16.2 kn (30.0 km/h; 18.6 mph) with 10,400 ihp (7,800 kW) while USS Oregon reached 16.8 kn (31.1 km/h; 19.3 mph) with 11,000 ihp (8,200 kW).

The Indiana class in action: From 1898 to the interwar

USS Oregon was laid down at Union Iron Works on 19 November 1891, launched in 26 October 1893 and completed 16 July 1896. All three battleships were the rare ones to see action in two wars, 1898 and 1917-18, separated by almost the same gap as ww1 and ww2. The war of 1898 was almost the last “romantic” war, full of dashing and bravado over, easy victory of a young nation over a crumbling old empire. But due to their very design, their contribution to the war effort in 1917-18 was limited.

USS oregon in dydock, 1898

USS Indiana (BB-1)

USS Indiana (BB-1)

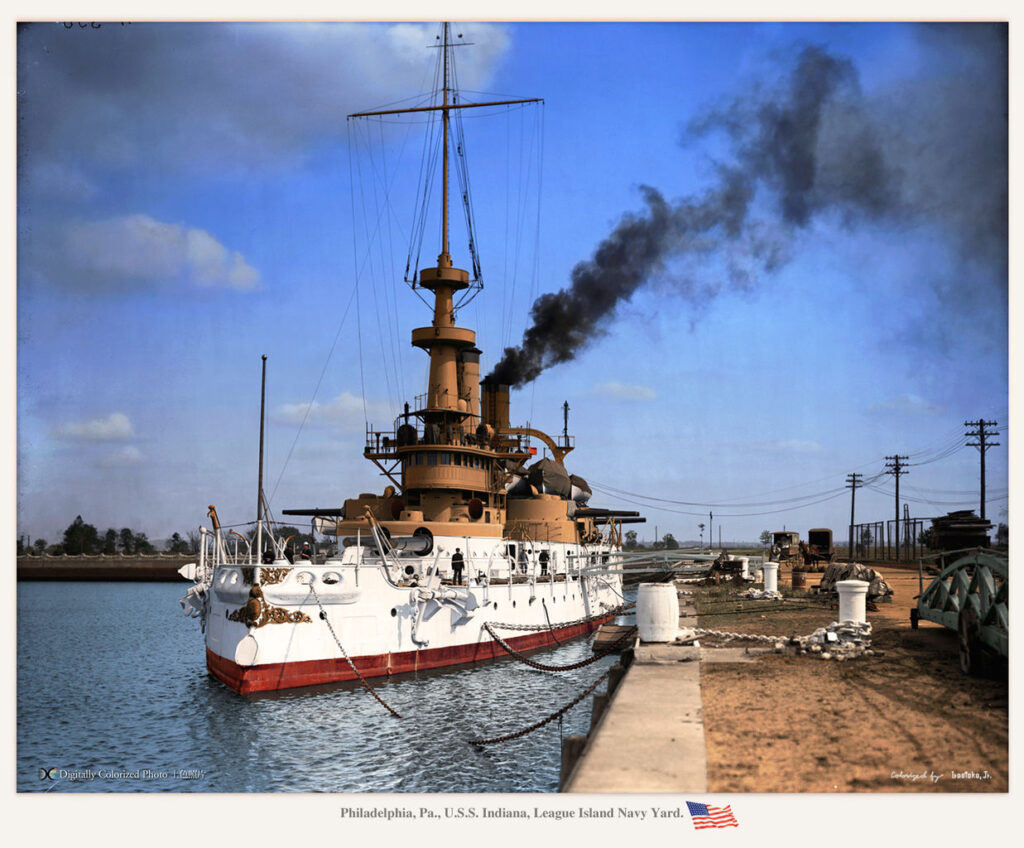

USS Indiana, colored by Irootoko JR

There is nothing notable before the Spanish-American war in 1898 (see details of the battle of Santiago de Cuba). She was then flagship of the North Atlantic Squadron, bearing the colors of Rear Admiral William T. Sampson. She raided the port of San Juan, bombarding it, before rallying Commodore Schley’s Flying Squadron which had found Cervera in Santiago. She arrived two days later but did not chased Cervera as being in the extreme eastern position. However she later catch destroyers Pluton and Furor when they emerged from the entrance and destroyed them.

From 1899 to 1903, she alternated training exercises with the fleet before being decommissioned after a career less than 8 years. She was recommissioned three years later as dedicated training ship, having just received new modern boilers, and a cage mast replacing her ancient heavy mast. She was against decommissioned in 1914, and reactivated in 1917, for gunners training.

On 31 January 1919 came her final decommission, her name being passed to BB-50 while she was renamed Coast Battleship Number 1. She ended in shallow water as a torpedo target and aerial bombing tests ship in November 1920 and her remains were refloated and sold for scrap in 1924.

USS Indiana in Drydock, 1898.

USS Indiana in 1919.

Note: Full history in 2026 update.

USS Massachusetts (BB-2)

USS Massachusetts (BB-2)

She conducted training exercises on the eastern coast soon after completion, and in 1898 was placed in the Flying Squadron under Commodore Winfield Scott Schley. She blockaded the port of Santiago but was missing when the battle started, as she was back to Guantánamo Bay in the night to resupply. She joined Texas which was shelling the Spanish cruiser Reina Mercedes, scuttled to block the entrance.

After the war she spent her career with the North Atlantic squadron, patrolling the Atlantic coast and eastern Caribbean. Before her decommission she was used as a training ship for Naval Academy midshipmen in 1906. She received new boilers and a cage mast, and was back as a “reduced commission” training ship in May 1910.

She then joined the Atlantic Reserve Fleet in September 1912, was decommissioned in May 1914, then back again in June 1917 as a gunner training ship. Decomm. again 31 March 1919, renamed Coast Battleship Number 2, scuttle in 1921 off the coast of pensacola, sunk as an artillery target for Fort Pickens.

However as her hulk found no buyer she layed there as an artificial reef since then. Now a diver’s attraction and property of the state of Florida (Florida Underwater Archaeological Preserves).

Massachusetts in 1919

USS Massachusetts sinking as target in 1921

Note: Full history in a 2027 update.

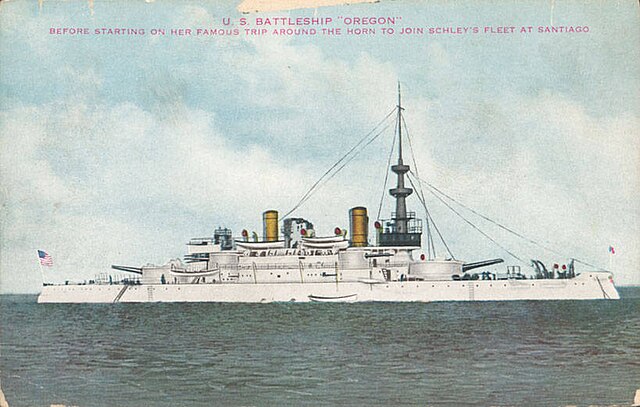

USS Oregon (BB-3)

USS Oregon (BB-3)

She joined the Pacific Station after a voyage around South America to the East Coast in March 1898 (in preparation for war with Spain), covering 14,000 nautical miles in just 66 days.

The press noted the feat buy also found it a great argument against any opponents to the completion of the Panama Canal. However she was back in North Atlantic Squadron under Rear Admiral Sampson, taking part in the Battle of Santiago de Cuba and chasing together with the cruiser Brooklyn the Spanish Cruiser Colon.

She earned the nickname “Bulldog of the Navy” because of her ploughing bow, in marine slang “having a bone in her teeth”. She was afterwards refitted in New York City, then returned to the pacific, served a year in the Philippine–American War, then joined China, Wusong during the Boxer Rebellion (May 1901) and returned to drydock in the USA for an overhaul.

She was back in the pacific in March 1903, was decommissioned from April 1906 to August 1911, and was placed into reserved in 1914. In January 1915 she was back in service, joining San Francisco for the Panama–Pacific International Exposition, then replaced in reserve.

She was eventually recommissioned for the last time in April 1917, and escorted transport ships during the Siberian Intervention. She also was a reviewing ship for President Woodrow Wilson (Pacific Fleet at Seattle) and was retired for good in October 1919 and was transferred in 1925 to State of Oregon, starting a life of war memorial.

However in 1941 given her scrap value she was sold as IX-22 and partly recycled. Her stripped hulk served as a supply barge at Guam, but in 1948 because of a typhoon, broke loose, drifted away and was recovered and resold 15 March 1956 in a shipbreaker in Japan.

Note: Full history in 2028 update.

Sources

Books

Chesneau, Roger; Koleśnik, Eugène M.; Campbell, N.J.M. Conway’s all the world fighting ships 1860-1905 and 1906-1921.

Friedman, Norman (1985). U.S. Battleships, An Illustrated Design History. NIP

Gardiner, Robert; Lambert, Andrew D. (1992). Steam, Steel & Shellfire: The Steam Warship 1815–1905. Conway Maritime Press.

Graham, George E.; Schley, Winfield S. (1902). Schley and Santiago: an historical account of the blockade and final destruction of the Spanish fleet under command of Admiral Pasquale Cervera, July 3, 1898. Texas: W.B. Conkey company.

Reilly, John C.; Scheina, Robert L. (1980). American Battleships 1886–1923: Predreadnought Design and Construction. Arms and Armour Press.

“The Speed Trial of the United States Battleship Massachusetts”. Scientific American. 74: 297. 9 May 1896.

Wright, Christopher C. (2007). “Question 40/04: Proposed Conversion of Old U.S. Battleships to Monitors”. Warship International. XLIV

“Indiana”. Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History and Heritage Command.

“Massachusetts”. Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History & Heritage Command.

“Oregon”. Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History & Heritage Command.

Links

on historycooperative.org/

on history.navy.mil Indiana

museumsinthesea.com massachusetts

web.archive.org history.navy.mil/

commons.wikimedia.org/ Indiana_class_battleships

history.navy.mil/ massachusetts-iv.html

history.navy.mil/ indiana-battleship-no-1-i.html

on spanamwar.com/index.html

nps.gov/ uss massachusetts

history.navy.mil oregon-ii.html

navsource.org indiana

navsource.org oregon

web.archive.org/ navsource.org massachusetts

Gallery

Model Kits

More Eye Candy

USS Indiana berthed at League Island Navy Yard, Philly, wonderfully colorized by Irootoko JR src

USS Massachusetts in her peacetime livery. Her low freeboard is quite obvious here.

USS Oregon steaming off New York for Cuba in 1898, sporting her early medium grey wartime livery, unusual for 1890s ships. Note that her prow ornaments had been removed and replaced by a painted blazon in US colors instead.

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign