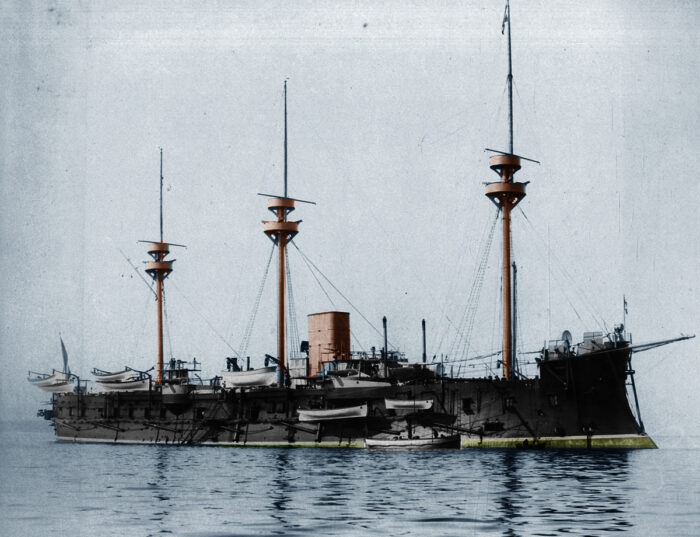

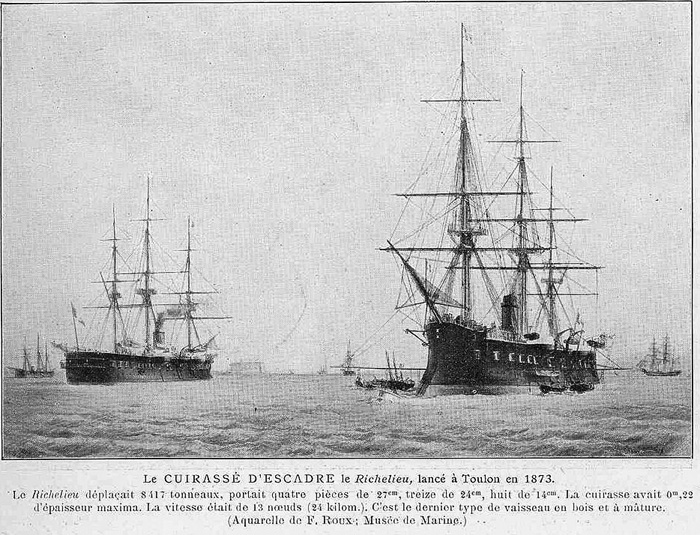

The French ironclad Richelieu was a wooden-hulled central battery ironclad started before the Franco-Prussian war and completed after a redesign in 1875. She was named after the 17th century statesman and Cardinal, designed by Dupuy de Lôme as an improved Ocean class, with her main guns in barbettes and a two-stage central battery. She became flagship of the Mediterranean Squadron for most of her career, but caught fire in 1880, and was scuttled to prevent her magazines from blowing up. Salvaged later, fully repaired and modernized, she returned as flagship until placed into reserve in 1886 and condemned in 1901. As a ship which did not want to end in a scrapyard, while towed in the Bay of Biscay on her way to Amsterdam, her line was cast loose to not bring her tug under during a storm. She survived, located later drifting away near the Scilly Isles, and was tugged to her final destination anyway.

Design of Richelieu (1868-69)

Hull & general appearance

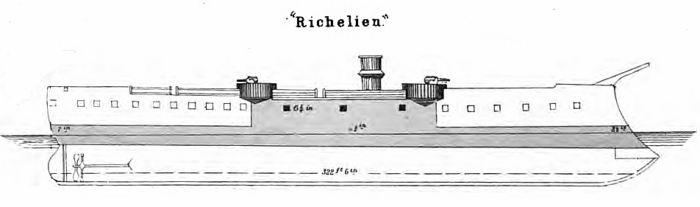

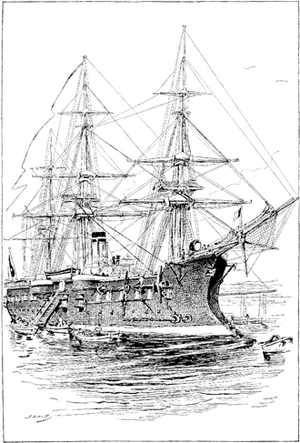

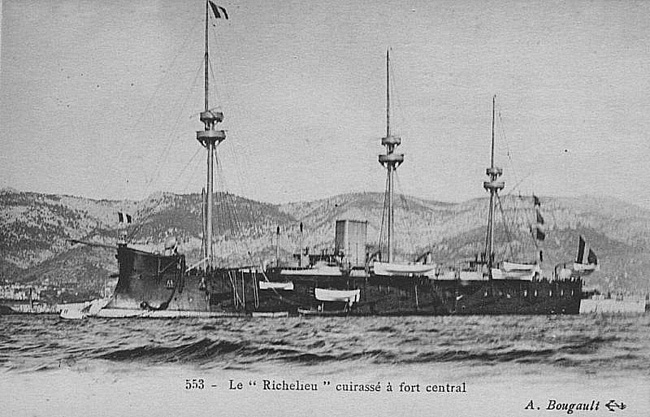

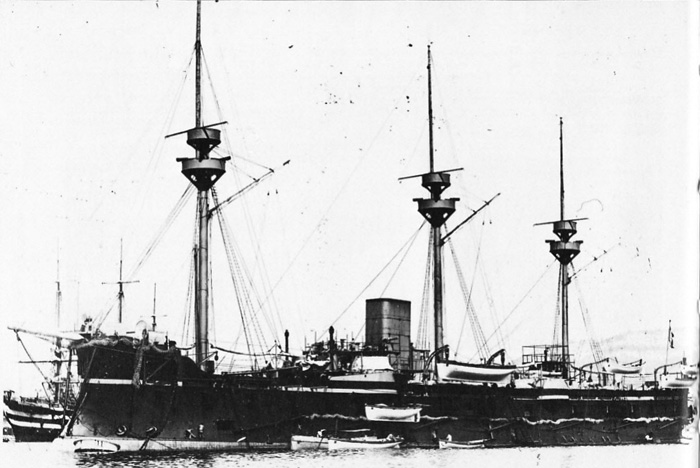

Henri Dupuy de Lôme, French superstar designer, which signed all major French warships since the 1850 Napoléon, designed the Richelieu as an improvement over his previous Océan-class ironclads. As a central battery ironclad, she had her armament concentrated amidships but in a two-storey arrangement between a classic concentrated broadside and upper heavy guns in barbettes for a better arc of fire. She combined this with an improved plough-shaped ram projecting no less than 10 feet (3 m) from her hull, and a 3-masted barque rigging typical of her day. Her appearance changed during her career, and her crew numbered around 750 officers and men, counting on a fleet of 16 boats of various types, some under single davits, and eight aft under double davits.

Richelieu was substantially larger than the Ocean class, measuring 101.7 meters (333 ft 8 in) overall for a beam of 17.4 meters (57 ft 1 in) and had a maximum draft of 8.5 meters (27 ft 11 in) while displacing 8,984 metric tons (8,842 long tons). She had a tall and short forecastle, then a continuous deck with bulwarks down to the poop. Her metacentric height was very low, at just 1.5 feet (0.5 m) so her roll was long and manageable for the crew, but she was at greater risk of overturning. The master idea was to make her more agile and better as a ram.

Powerplant

To be better at manoeuvring, Richelieu was given by Dupuy de Lôme de advantage of two propellers instead of a single one for the Ocean class and the preceding Friedland. Henri Dupuy de Lôme homed to use the power plants themselves to moderate speed and increase the efficiency of the axial rudder. She needed to out-turn other ships in melee, giving her a decisive advantage for ramming. The engines chosen were two Indret 3-cylinder horizontal return connecting rod (HRCR). These were compound steam engines driving each a single large bronze 2-bladed propeller. These engines were fed by eight Indret oval boilers.

To be better at manoeuvring, Richelieu was given by Dupuy de Lôme de advantage of two propellers instead of a single one for the Ocean class and the preceding Friedland. Henri Dupuy de Lôme homed to use the power plants themselves to moderate speed and increase the efficiency of the axial rudder. She needed to out-turn other ships in melee, giving her a decisive advantage for ramming. The engines chosen were two Indret 3-cylinder horizontal return connecting rod (HRCR). These were compound steam engines driving each a single large bronze 2-bladed propeller. These engines were fed by eight Indret oval boilers.

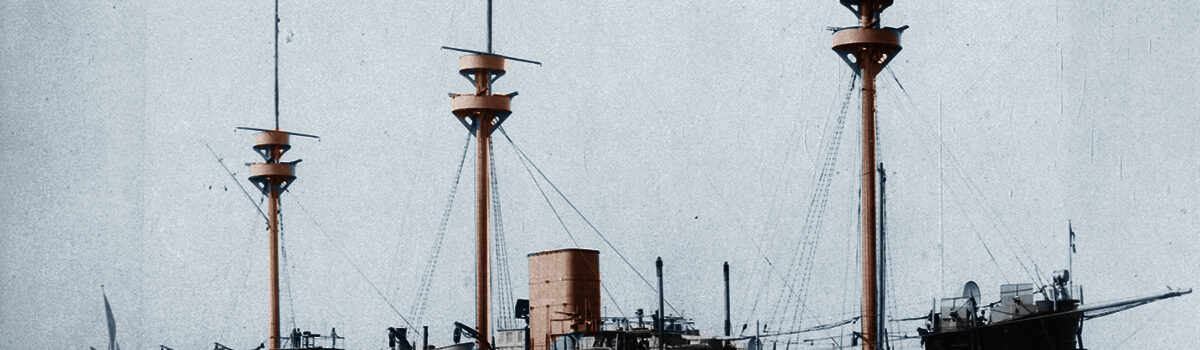

On trials based on 4,600 indicated horsepower (3,400 kW) she managed to reach 13.2 knots (24.4 km/h; 15.2 mph) for a contracted speed of 13 knots (24 km/h; 15 mph), earning her builder, Arsenal de Toulon, to be awarded bonuses. She carried 640 metric tons (630 long tons) of coal, a bit more on Friedland, but was slower than the latter. This enabled her a range of 3,300 nautical miles (6,100 km; 3,800 mi) on coal alone at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) however, more than the 2200 nm of her predecessor. Richelieu had a square rigging initially to reach distant station by preserving coal, but seemed not to be an efficient sailing ship. Her three masts were soon cut down and simplified as a schooner rig. Later in 1982, they received military masts.

Protection

Richelieu was given a belt armour 220 mm (8.7 in) strong, in wrought iron at the waterline. Both the sides and battery transverse bulkheads were armoured and had 160 millimetres (6.3 in) of wrought iron as well. The barbettes were wilfully left unarmoured due to weight balance issue, and there was at first no mask to protect the gun operators. But the armoured deck was protected by 10 mm (0.4 in) of iron plating. Meanwhile, steel casting and foundry techniques for very large parts were progressing. This would lead to the construction of the Redoutable class, just a step after the Richelieu, which was Colbert class, started in 1870. They were the last French ironclads, effectively only protected by wrought iron.

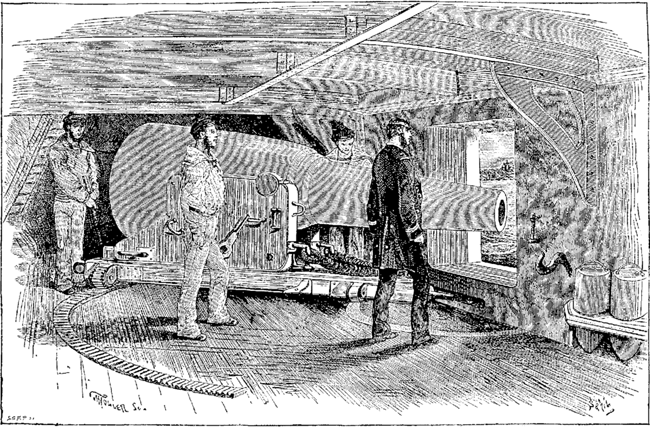

Battery Deck illustration

Armament

Like the Ocean class, she had four identical guns in barbettes, four Canon de 24 C modèle 1870 on her upper deck open barbettes, covering all corners of the battery. In contrast, the preceding Friedland only had two larger guns (274mm) forward. The remainder were larger guns, six 274 mm (10.8 in) on the battery deck, below the barbettes. This was the only choice to preserve stability. There was also a supplementary 240 mm mounted in the forecastle, acting as chase gun. Her secondary armament was still generous, comprising ten 120 mm (4.7 in) guns, later replaced by six 138 mm (5.4 in) guns.

Main: Four Barbette 240 cm (9.4 in) M1870

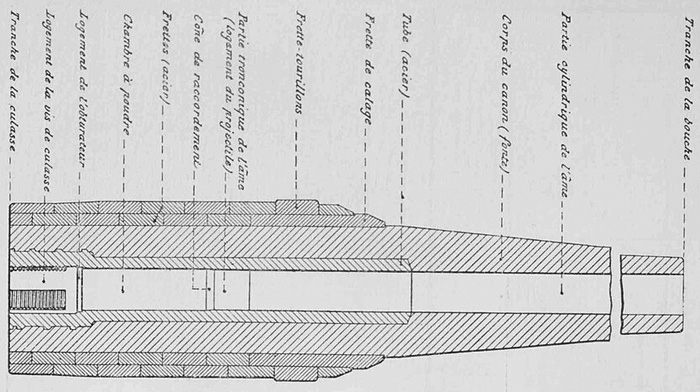

These guns were made by Ruelle Foundry in 1870, they derived from the earlier Canon de 24 C modèle 1864, switching from muzzle-loading to breech-loading guns but still using cast iron gun barrels for cost, speed and ease of manufacture. The 1864 models entered service in 1867 with steel hoops and shells three times heavier than previous round bullets for the muzzle velocity of 334–345 m/s.

The 1870 system had its barrel also hooped, but it was built from a short steel inner tube increasing longitudinal strength which had many shallow grooves instead a few deep grooves. Internal Pressures could grow 50% higher. Their obturator was made by a ring of red copper and the ignition took place via the breech block, starting in the centre of the bottom part of the charge for more regular initial velocities, less strain on the gun. It used also a less offensive gunpowder, longer projectiles with copper driving bands and bourrelet. Performances were greatly improved across the board.

Characteristics (1870M):

Type: Separate-loading, bagged charge and projectiles

Mass & Dimensions: 15,660 kg or 15.41 long tons, 4.940 m (16.21 ft) L/21.

Shell: AP 317.5 pounds (144.0 kg). Muzzle velocity 1,624 ft/s (495 m/s). Penetration 14.4 inches (366 mm) wrought iron at the muzzle.

Elevation/rate of fire: 30°, 1 round every two minutes.

Effective range: 10 km (6.2 mi) basic and 10.8 km (6.7 mi) for the 1870 M

Main: Six Central Battery 274 cm (10.4 in) M1870

The 22.84 long tons (23.21 t) 18-caliber 274 mm Modèle 1870 gun fired an armour-piercing (AP) 476.2-pound (216.0 kg) shell at a muzzle velocity of 1,424 ft/s (434 m/s) and was capable of defeating 14.3 inches (360 mm) of wrought iron armour at the muzzle. See the previous post on Friedland for more details.

Secondary: Ten 12 cm (4.7 in)

No data so far.

Secondary (upgrade): Ten 13.8 cm (5.4 in)

This was a 21 calibers, 2.63 long tons (2.67 t) model, which fired a 61.7-pound (28.0 kg) HE shell at a muzzle velocity of 1,529 ft/s (466 m/s), but also was capable of fitring classic solid shots, and had stores of it. It was mostly used against fortifications.

Later: 47/37 mm Hotchkiss (6-3 pdr.)

47mm: No data.

Later in her career, Richelieu received eight, and then later ten more, 37 mm (1.5 in) Hotchkiss 5-barrel revolving guns, firing a 500 g (1.1 lb) HE shell at a muzzle velocity of 610 m/s (2,000 ft/s) to a range of c3,200 meters (3,500 yd). Rate of fire was 30 rounds per minute.

TTs: 2-4 356 mm tubes (14 in)

In 1884, two above-water 356-millimeter (14.0 in) torpedo tubes were added.

⚙ Richelieu specifications as built |

|

| Dimensions | 101.7 x 17.4 x 8.5m (333 ft 8 in x 57 ft 1 in x 28 ft) |

| Displacement | 8,984 metric tons (8,842 long tons) |

| Propulsion | 2 shafts, HRCR steam engines, 8 oval boilers: 4,600 ihp (3,400 kW) |

| Speed | 13 knots (24 km/h; 15 mph) |

| Range | 3,300 nm (6,100 km; 3,800 mi) at 10 knots |

| Armament | 6× 274 mm (10.8 in), 5× 240 mm (9.4 in), 10x 120 mm (4.7 in) |

| Protection | Belt 220 mm (8.7 in), Battery 160 mm (6.3 in), Bulkheads 100 mm (3.9 in), Deck 10 mm (0.4 in) |

| Crew | 750 |

Richelieu’s career (1876-1900)

Richelieu was laid down at the Arsenal de Toulon (French Riviera) in 1869, but only launched on 3 December 1873, and had prolonged construction time as result as a mix of financial pressures caused by slashing French Naval budget after the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71, outdated work practices and lack in investment in the arsenal’s infrastructures for decades, as well as probably design changes overtime due to succeeding ministers, the classic illness of French naval construction and planning at the time. Toulon was part of these antiquated French dockyards that completely missed the Industrial Age. Still, six years was relatively reasonable when Richelieu was completed and started her sea trials on 12 April 1875, but she needed fixes and more trials, and only entered service with the Mediterranean Squadron as flagship (as she was the largest French capital ship at the time), from 10 February 1876. She was placed in reserve on 3 December 1879, due to budget constraints.

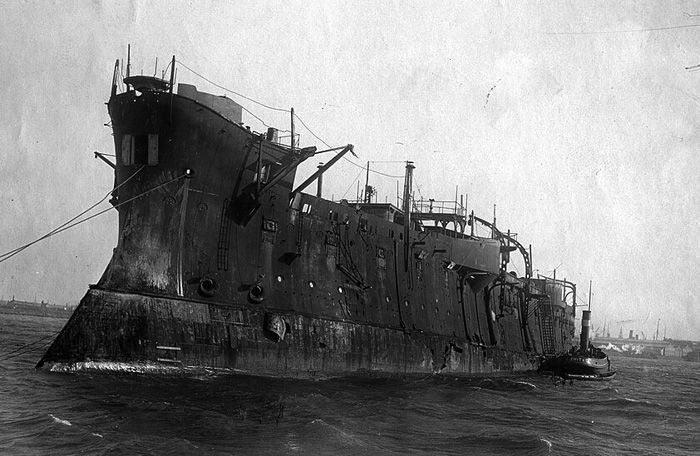

While anchored in Toulon harbour on 29 December 1880, she caught fire. The exact reasons why it started was never completely established by the later enquiry commission. Some argued this was likely an unauthorized bagged storage too close to a machinery bulkhead, while raising steam, or just poor cooling inside the hull in storage spaces. Whatever the root cause, she had to be scuttled to prevent her magazines from exploding as the fire progresses quickly. This was done simply by opening water pump cocks. She capsized however due to her unequal stability, and settled, laying on the bottom under 10.75 meters (35.3 ft) of water, her barbettes at a 90° angle. Immense efforts were procured to salvage her, her ammunition, masts, armour and movable decks were all removed. A massive weight was gradually loaded into her holds to lower her centre of gravity, and a system of cranes and pulley was set in place. A sheer hulk was moved to her port side, cables were connected to the ship Sybille on the other side, with 360 empty casks, 34 cubic meters (1,200 cu. ft.) of attached to starboard o prevent her from rolling too far the other way. The final effort after weeks of preparations took one hour and a half of lifting until she reached a 45° angle, and more applied a day later to reach her straight level.

Richelieu then was towed to the dry-dock and needed long repairs due to all seawater that seeped into the entire internal hull and sat for a time, saltwater degrading everything. She also was modernized at the time, with her schooner rig further simplified, having just the composite masts with all three a fighting top with a 37mm Hotchkiss 6-barreled gun and a spotting top above. She returned into service as flagship of the Mediterranean Squadron again from 8 October 1881, almost a year since her scuttling. Likewise, she remained listed as such until 1886, despite better, more modern ironclads entered service in between.

Furthermore, she led the squadron in between for port visits such at Tangiers and Lisbon in 1884, and joined the Atlantic fleet for combined exercises, visiting Brest and Cherbourg. In 1885, Richelieu tested the Bullivant torpedo nets, folded onto her hull while underway. It was show they drastically reduced her speed down to 4 knots (7.4 km/h; 4.6 mph). They also aggravated her roll considerably. Trials were not considered successful as a result.

She returned to the reserve in 1886. She was later reassigned as flagship of the Reserve Squadron from 8 September 1892, still in official commission. The squadron sorties notably for exercises from June to August 1892. Richelieu was at last condemned on 5 March 1900 (stricken from the register), but her hull not immediately sold, laying at Toulon reserve for many more years. She was eventually sold to a ship breaking company operating in the Netherlands, at Amsterdam, in 1910. She departed Toulon on 28 January 1911 under tow. While underway in the Bay of Biscay, she was caught in a storm. It caused the tugboat to cast her loose to avoid being dragged to the bottom. Richelieu remained afloat. She started drifting after the storm abated, out of view from the tug. A search was launched. She was eventually recovered near the Scilly Isles, apparently having being tossed on to rocks, but without damaging the hull to the point of creating a breech. She was towed to Amsterdam eventually, and started to be broken up.

Richelieu being broken up at Amsterdam, 1911-12.

Read More/Src

Books

de Balincourt, Captain; Vincent-Bréchignac, Captain (1975). “The French Navy of Yesterday: Ironclad Frigates”. F.P.D.S. Newsletter. III

Campbell, N. J. M. (1979). “France”. In Chesneau, Roger & Kolesnik, Eugene M. (eds.). Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships 1860–1905.

Brassey, Thomas (1888). The Naval Annual 1887. Portsmouth, England: J. Griffin.

Roberts, Stephen S. (2021). French Warships in the Age of Steam 1859–1914: Design, Construction, Careers and Fates. Seaforth Publishing.

Ropp, Theodore (1987). The Development of a Modern Navy: French Naval Policy 1871–1904. NIP

Saibene, Marc (1995). “The Redoubtable, Part III”. Warship International. XXXII (1). Toledo.

Silverstone, Paul H. (1984). Directory of the World’s Capital Ships. Hippocrene Books.

Wilson, H. W. (1896). Ironclads in Action: A Sketch of Naval Warfare From 1855 to 1895. Vol. 2. Boston, Massachusetts: Little, Brown.

Links

https://www.navypedia.org/ships/france/fr_bb_richelieu75.htm

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/French_ironclad_Richelieu

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Canon_de_24_C_mod%C3%A8le_1870

http://www.navweaps.com/Weapons/WNFR_Main.php

on archive.wikiwix.com/ Fjose.chapalain.free.fr

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign