United Kingdom (1906) HMS Colossus, HMS Hercules

United Kingdom (1906) HMS Colossus, HMS HerculesWW1 RN Battleships

HMS Dreadnought | Bellerophon class | St. Vincent class | HMS Neptune | Colossus class | Orion class | King George V | Iron Duke class | HMS Agincourt | HMS Erin | HMS Canada | Queen Elizabeth class | Revenge class | G3 classMajestic class | Centurion class | Canopus class | Formidable class | London class | Duncan class | King Edward VII class | Swiftsure class | Lord Nelson class

Invincible class | Indefatigable class | Lion class | HMS Tiger | Courageous class | Renown class | Admiral class | N3 class

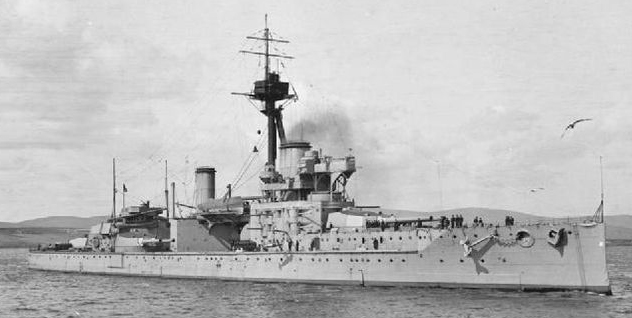

The Colossus-class battleships were 1st generation dreadnought battleships of the Royal Navy built at Palmers and Scott shipyard in 1909-1911. They were also the last with 12-inch gun for the RN, but with a different configuration of turrets mounted amidship en echelon. They spent time at the Home and Grand Fleets, often as flagships.

The Colossus-class battleships were 1st generation dreadnought battleships of the Royal Navy built at Palmers and Scott shipyard in 1909-1911. They were also the last with 12-inch gun for the RN, but with a different configuration of turrets mounted amidship en echelon. They spent time at the Home and Grand Fleets, often as flagships.

Furthermore, they took part in the Battle of Jutland in May 1916, and the action of 19 August later, to break the relative boredom of their routine patrols and training in the North Sea. They were deemed obsolete by 1918, reduced to reserve in 1919 with Hercules being sold for scrap in 1921, Colossus lingering as a training ship until hulked in 1923, sold 1928.

Design of the Colossus

Design Genesis

Construction was also motivated by a 1908 rumour about the secret start of new dreadnoughts ordered by the Kaiser (which turned to be false). Winston Churchill, then at the head of the trade office, then violently argued with the Admiralty. He famously coined then “we want eight (dreadnought) and we will not wait” which was also popular at the House of Commons. Eventually the Liberal cabinet, which until then temporized, trying to keep a tight naval budget, had to bend, alarm too by the intelligence service report. No less than six other battleships were ordered then, the first two being the Colossus and Hercules. They were laid down at Scotts Greenock in July 1909, launched in April 1910 and accepted in August 1911.

HMS Neptune when launched in 1909, experimented a main artillery of five twin turrets in a new configuration of one front, two aft centerline, and two axial ones in echelon. These sister-ships started at Scott and Palmers in 1909.

They were keeping the number of the previous 12-inch Mark XI 50-calibre guns with the disposition seen on the Neptune. However, superfluous sources of weight were eliminated, namely the bridge between the second chimney and aft deckhouse. The central turrets were spaced closed together, given a much better arc of fire for lighter artillery. Torpedo tubes 21-inch (533mm) Hardcastle torpedoes, which had a maximum speed of 45 knots (83 km/h) and effective range of some 7,000 yards, were fitted for the first time.

Last but not least, the belt protection was widely enhanced at 11 inches thick, and the rear deck was increased to four inches over the rudder, the forward bulkhead, conning tower, turret faces were also thickened, but this was performed on the same hull as the Neptune, and became a headache for engineers. In total, armour accounted for 5,474 tons of the displacement, the weight of a cruiser. The eighteen boiler Babcock and Wilcox worked at 235-240 psi, heated by 3 single-orifice burners (standard Admiralty type). 2,900 tons of coal and 900 tons of oil were carried.

Hull and general design

On 19 November 1908, Rear-Admiral Sir John Jellicoe (3rd Sea Lord and Controller of the Navy) proposed changes to the design with a redistribution of the armour from locations statistically less exposed to enemy fire. He also insisted of having 21-inch (533 mm) torpedoes instead of 18-inch (450 mm) torpedo tubes, and having more spare torpedoes. On the other hand, Admiral Francis Bridgeman, CiC Home Fleet agreed with Jellicoe to eliminate the mainmast and transfer all spotting top to a proper armoured spotting tower above the conning tower. This was opposed by DNO Rear-Admiral Reginald Bacon for height’s sake. The topmasts were just better at spotting. Jellicoe also wanted to increase displacement of the new ships and this angered DNC Sir Philip Watts for additional calculations.

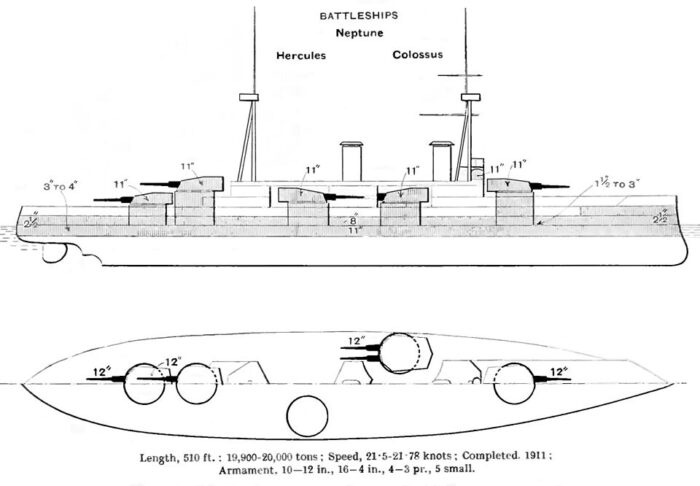

Right elevation and plan from Brassey’s Naval Annual 1915. This diagram shows masts for HMS Neptune as the Colossus class had only a foremast, positioned behind the forward funnel.

The DNC also maintaned the mast was needed for boat-handling derrick, until overruled by the Admiralty which preferred a tripod foremast aft of the forward funnel with its legs facing forward so that the vertical leg could support the derrick. As a result, this conspired to have hot funnel gases transforming the spotting top into a cauldron, it was just too hot to be used. The short height of the funnel also smoked the bridge until raised in 1912, and this only aggravated the issues with the spotting top, and this went with the poor decision to have the echeloned, wing turrets closer together, reducing space available to the aft boiler room. As a result, the forward funnel had to accommodate the exhausts of a dozen boilers, twice as much as the aft one, which only built up far more smoke forward. This poor arrangement was kept for all eight battleships of the 1909-1910 program and modifications were done only on two battlecruisers at great cost.

This was severely criticized by David K. Brown, naval architect and historian.

In the end, the two Colossus class were slightly larger than neptune. They had the same lenght at 545 ft 9 in (166.3 m) overall, for a beam of 85 feet 2 inches (26.0 m) for Colossus and 86 feet 8 inches (26.4 m) for Hercules, and the same draught on paper of 27 ft (8.2 m), however it’s likely the extra buoyancy on Hercules gave her a lesser draught.

The general design was still a copy-paste of the Neptune class, except the points seen above. Displacement figures are disputed withing sources but now it is generally agreed that they displaced 20,030 long tons (20,350 t) at normal load, 23,266 long tons (23,639 t) at deep load.

Powerplant

The Colossus and Hercules differed little from the previous Neptune. On that chapter they were near-sisters with their similar arrangement and output. They had two sets of Parsons direct-drive steam turbines, but with the major difference of them place in three separate engine rooms with outer propeller shafts driven by the HP (high-pressure) turbines and inner props by inner rooms exhausted into LP (low-pressure) turbines.

These turbines were fed by eighteen water-tube boilers, working at a pressure of 235–240 psi (1,620–1,655 kPa; 17–17 kgf/cm2) and rated at 25,000 shaft horsepower (19,000 kW). They were were intended to give these dreadnoughts a top speed of 21 knots (39 km/h; 24 mph). In sea trials, they exceeded their designed speed and horsepower calculated figures, at forced draft. As for range, they carried 2,900 long tons (2,947 t) of coal maximum, plus and an additional 800 long tons (813 t) of fuel oil to be sprayed on coal and increase the burn rate. Range was 6,680 nautical miles (12,370 km; 7,690 mi) at 10 knots cruising speed (19 km/h; 12 mph).

Protection

-KC (Krupp cemented armour) waterline belt: 11 inches (279 mm) fore and rear barbettes.

-Outer belt: 2.5 inches (64 mm) outside the citadel, short of the bow and stern, instead Neptune.

-Belt height: 2 feet 9 inches (0.8 m) above, 5 feet 6 inches (1.7 m) below waterline, tapered to 8 in (203 mm) bottom edge.

-Above belt strake armour: 8-inches.

-Forward Bulkhead: 4-inch (102 mm), connected from the waterline and upper belts, to ‘A’ barbette.

-Aft bulkhead connected to ‘Y’ barbette, 8 inches thick.

-Centerline barbettes, face, 10 inches (254 mm) above the main deck (4-5 inches (127 mm) below).

-Wing barbettes same but 11 inches, outer faces.

-Gun turrets 11-inch faces sides, 3-inch roofs.

-Three armoured decks, 1.5 to 4 inches (38 to 102 mm), latter outside central citadel.

-Conning tower 11-inch walls, roof 3 inches thick.

-Spotting tower above CT: 6-inch (152 mm) sides

-Torpedo-control tower aft: 3-inch sides, 2-inch roof.

-No anti-torpedo bulkheads protecting the engine and boiler rooms

-Outboard magazines bulkheads 1-3 inches (25 to 76 mm).

-Boiler Uptakes: 1-inch armour plates.

Armament

The Colossus class were armed the same way as Neptune, apart the two echelones (or stagerred) turrets amidship were closer together, in order to reduce blast damage when firing broadsides on either side, but this proved a poor choice due to the modifications to the boilers and funnel’s smoke as seen above. However, this was not enough, since the blast damage to the superstructure and boats made the broadside impractical except in emergency. Like the Neptune, they had their boats on girders over the two wing turrets to reduce length, but if damaged during combat, they could fall onto the turrets and immobilise them. The bridge and its compass platform could also fell on the conning tower, if collapsed. The ship would be blind. No dreadnought after them ever reverted to the stagerred arrangement. There was enough experience already with superfiring turrets to go centreline in the next designs.

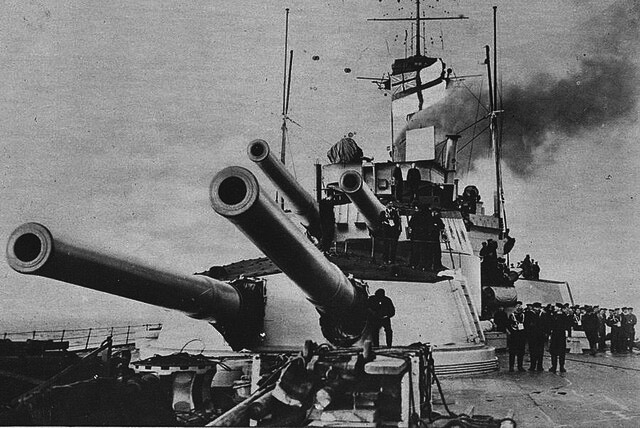

BL 12-inch/50 (305 mm) Mark XI guns

Like the Neptune, five twin mount turrets, one centerline on the forecastle (A), two amidship stagerred (P, Q), two centerline, superfiring aft (X, Y). The turrets were hydraulically powered.

-Maximum elevation +20°, range 21,200 yards (19,385 m).

Shell: 850-pound (386 kg), muzzle velocity 2,825 ft/s (861 m/s)

Rate of fire; two rounds per minute.

Capacity: 100 shells per gun, 1,000 total.

BL 4-inch/50 (102 mm) Mark VII

Same as the Neptune class. Sixteen in all, installed in unshielded single mounts in the superstructure, no casemates. At least they were not obscured by water spray.

-Maximum elevation +15°. Range 11,400 yd (10,424 m).

Shell 31-pound (14.1 kg) HE, muzzle velocity of 2,821 ft/s (860 m/s).

Capacity 150 rounds per gun, 2400 total.

In addition they had also four 3-pounder (1.9 in (47 mm)) saluting guns.

Torpedo Tubes

The Colossus, at the insistance of Jellicoe, had three 21-inch submerged torpedo tubes, each broadside and stern, in a triangle patter, with a generous supply of 18 torpedoes. The first and last time they were used for real was at Jutland. Afterwards, they were removed from all battleships as potential weaknesses in the hull. The model was likely the Mark I “long” notmally used by destroyer, as it was available in 1910, but in 1915, replaced by proper torpedoes for battleships, the 21″ (53.3 cm) Mark II***.

Specs:

515 lbs. (234 kg) TNT warhead for c4000 lbs. (1.8 tons)

Powered by Wet-heater for 4,500 yards (4,110 m) at 45 knots or 10,750 yards (9,830 m) at 31 knots.

Fire Control

HMS Neptune inaugurated better fire controls, but the Colossus innovated by the placement of the fire control tower atop the conning tower. However at the insistence of the DNC, control position for the main armament remained in the spotting tops at the foremast, often obscured by smoke and made cooking levels hot if the conditions were reunited. Data from the nine-foot (2.7 m) Barr and Stroud coincidence rangefinder here went to a Dumaresq mechanical computer. In turn it was electrically transmitted to Vickers range clocks in the transmitting station beneath each position on the main deck and from there, converted into range and deflection data for the main guns with indicators inside the guns themselves. A complicated system, but the time needed to reload the guns between each volley made this viable, with a relatively rapid elevation.

The target’s data was also graphically recorded on a plotting table so that the gunnery officer could predict target moves.

In 1912, they received another 9-foot rangefinder at the forward side of the compass platform atop the bridge.

In late 1914, more 9-foot rangefinders this time protected by armoured hoods were installed on the turret roofs as well as backups.

Their director firing system, mounted high in the ship electrically provided data to the turrets via pointers, and layer fired the guns simultaneously helping to spot shell splashes and minimise effects of the roll on dispersion. This system was present on all ship by December 1915.

The Dreyer Fire-control Table was later installed, combining the Dumaresq and range clock into a single transmission stations. Hercules in fact tested the prototype table from Commander Frederic Dreyer by late 1911, until February 1916, replaced by a Mark I table in 1918 and Colossus a Mark I table from early 1916.

Profile of the Colossus class, in 1911.

Colossus specifications |

|

| Displacement | 19,680 tonnes standard* or 20,030 long tons (20,350 t) or 22,700t FL |

| Dimensions | 545 ft 9 in x 85 ft 2 in(86 ft 8 in) x 27 ft (166.3 x 26/26.4 x 8.2 m) |

| Propulsion | 4 shafts Parsons turbines, 18 WT boilers, 25.000 hp (19,000 kW) |

| Speed | 21 knots (39 km/h, 24 mph) |

| Range | 6,680 nautical miles (12,370 km) at 10 knots (19 km/h) |

| Armament | 5×2 12-in (305 mm), 16 ×4-in (102mm), 3× 21-in (533mm) sub TTs |

| Armor | Belt 8-11 in, Bulkheads 4-8-in, Barbettes 4-11 in, Turrets 11 in, Deck 1-4 in |

| Crew | 755 to 791 as flagship 1916 |

Service modifications

In 1912 their front funnel was raised to tame smoke issues (for the spotting top it was worse).

1913–1914: Small rangefinder added to ‘X’ turret roof, gun shieldse fitted to the 4-inch guns on the forward superstructure (Hercules).

August 1914,: Two 3-inch anti-aircraft (AA) added.

In early or mid-1915, the heavy torpedo nets were removed.

December 1915: Fire-control directors added on Colossus (platform below the spotting top), Hercules (rear extension of the compass platform)

May 1916: 50 long tons (51 t) of additional deck armour added. Four 4-inch guns removed, aft superstructure.

April 1917: single 4-inch and 3-inch AA guns, forward 4-inch guns enclosed in casemates.

Late 1917, Temporary platform fitted over their rear turret for an observation plane, masts shortened, rear tripod mast removed.

Late 1917 and early 1918: Stern torpedo tube removed.

1918: High-angle rangefinder fitted on the spotting top.

September–October 1921 refit: Colossus had her AA guns removed and some 4-inch guns

1922: Machinery removed to demilitarise the ship in accordance with the Washington Naval Treaty.

Career, in short

Trials took place in 28 February 1911. They took part in the Second Battle Squadron in may 1912, and figured at the Parliamentary Review of the Fleet in July 1912, and later in December 1913 joined the Second Battle Squadron. After an early uneventful career, anchored at Scapa Flow, HMS Colossus fought at Jutland, being the only English dreadnought damaged, by two hits that made 5 victims. In 1919 the Colossus served as a training ship, repainted in the old Victorian livery (black hull, white superstructures and sandy canvas). It was eventually decommissioned in 1928. HMS Hercules collided with a steamship in 1913 but was repaired before the war. She participated in the Battle of Jutland with the 6th Division, then embarked an allied naval commission in Kiel in November 1918, and was decommissioned in 1921.

Hercules was flagship of the 2nd Division Home Fleet, and from July 1912 to March 1913 flagship of the 2nd Battle Squadron. On March, 22, 1913 she collided with SS Mary Parkes of Glasgow, retaining only minor damage. In August 1914 she joined the Grand Fleet. On she fought on 31 May 1916 at the Battle of Jutland, 6th Division, also counting the Marlborough, Revenge and Agincourt. She fired about 98 shells on enemy battlecruisers, scoring hits and dodged torpedoes but remained unscaved.

She became flagship of the 4th Battle Squadron in June. In August at the raid on Sunderland she tested a towed kite balloon. She was sent in Orkney 24 April 1918 together with the St Vincent to support the Agincourt in the last sortie of the High Seas Fleet, and an operation in November, escorting the surrendering Imperial German Navy en route to Scapa Flow. In December she was at the Allied Naval Armistice Commission to Kiel, then back to Rosyth. Put in the reserved in February 1919 she was sold on 8 November 1921 to a shipbreaker and later scrapped in Germany. Restrospectively, they were the last of the pre super-dreadnought era (inaugurated by the Orion class), and thus in 1919, with their stagerred turrets unusuable most of the time, smoke and spotting top issues, they were not seen as a successful design, and were discarded without a second thought, courtesy of the Washington treaty if an incentive was needed.

THE Colossus class in Action

HMS Colossus (1910)

HMS Colossus (1910)

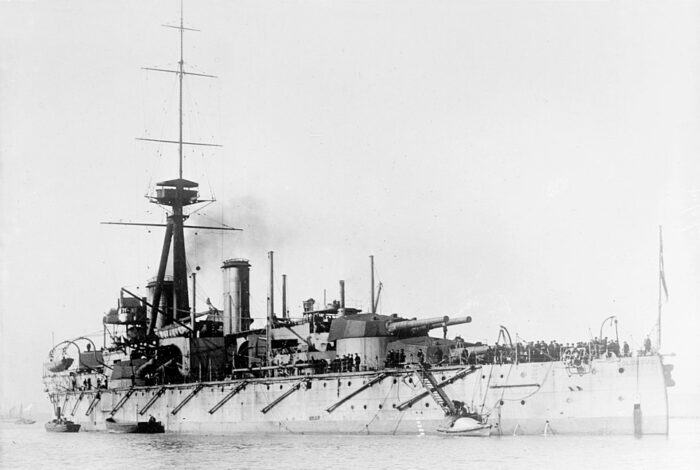

Colossus in 1911

Antiquity was still popular and thus, like her predecessor, Colossus was named after the Colossus of Rhodes. She was 5th of the name in the Royal Navy (RN). Ordered on 1 June 1909 she was laid down at Scotts Shipbuilding & Engineering in Greenock, 8 July. Launched on 9 April 1910, completed in July 1911 for a total cost of £1,672,102, including armament. Sea trials started on 28 February and until July. She was commissioned at Devonport on 8 August, then assigned to the 2nd Division, Home Fleet. This became the 2nd Battle Squadron on 1 May 1912. She was present for the Parliamentary Naval Review on 9 July at Spithead, as temporary flagship of the squadron. Hercules was meanwhile refitted by November–December. She took part in gunnery practice off Portland at 14,000 yards (13,000 m) setting up a record before the war. She was then transferred to the 1st BS, visited Cherbourg in March 1913.

From 17 to 20 July 1914, she took part in a test mobilisation/fleet review, British response to the July Crisis. She was in Portland on 25 July, and ordered to proceed to Scapa Flow on the 28th, against a possible surprise attack. Two engineers were killed in an accident whilst coaling the same day. In August as part of now the “Grand Fleet” under Admiral Sir John Jellicoe she was stationed at Lough Swilly in Ireland between 22 October to 3 November as defences at Scapa were strengthened. On 22 November 1914 she was in the first sweep in the southern half of the North Sea in support of Beatty’s 1st Battlecruiser Squadron, back on 27 November. Next she sailed NW of the Shetland Islands for gunnery practice on 8–12 December. She sorties again, too late, with the German raid on Scarborough, Hartlepool and Whitby. Then she was in another sweep of the North Sea, 25–27 December.

On 10–13 January 1915 she wa sin gunnery drills west of Orkney and Shetland. On 23 January, she sorties again in support of Beatty’s battlecruisers, but too far away for the Battle of Dogger Bank. On 7–10 March, another sweep in the northern North Sea, and training manoeuvres. Same on 16–19 March. Patrol on 11-14 April, central North Sea, again on 17–19 April, plus gunnery drills off Shetland, 20–21 April. She had other sweeps into the central North Sea on 17–19 May, 29–31 May. On 11–14 June, she was in gunnery practice and battle exercises west of Shetland and more on 11 July. On 2–5 September, she sweeped the northern end of the North Sea, plus gunnery drills. The month ended with scores of training exercises. With the majority of the Grand Fleet, she made another sweep into the North Sea, from 13 to 15 October. 3 weeks later she took part another fleet training operation, west of Orkney, 2–5 November. Next she became flagship of Rear-Admiral Ernest Gaunt, 5th Division, 1st BS Commander.

Then was another sweep in the North Sea on 26 February 1916 Jellicoe sending the Harwich Force east to the Heligoland Bight, however bad weather ended this, they patrolled the northern north sea instead. Same on 6 March, abandoned due to poor weather for destroyers again. On 25 March by night she and the fleet departed Scapa Flow to support Beatty and light forces for a raid on the German Zeppelin base at Tondern but on 26 March, the engagemnt was over and a gale threatened light craft. On 21 April, there was a diversionary demonstration off Horns Reef for Imperial Russian Navy minelaying operations. She was back to Scapa Flow on 24 April, refuelled, before proceeding south after room 40 knew about the incoming raid on Lowestoft, but arrived too late. On 2–4 May, the demonstration off Horns Reef was repeated.

Meanwile, the Kaiser grew impatient with the Hochseeflotte for its inaction and asked the naval staff to prepare a major acction in order to lure our and destroy a portion of the superior Grand Fleet. In all, sixteen dreadnoughts, six pre-dreadnoughts and supporting ships sallied out of the Jade Bight before dawn on 31 May. They sailed in concept of Rear Admiral Franz von Hipper and his 5 battlecruisers. Room 40 intercepted and decrypted German radio traffic and the Grand Fleet (28 dreadnoughts and 9 battlecruisers) departed in an attempt to take the Germans to their own trap, cutting their retreat and destroy them once and for all, possibly hasting up the end of the war. They sorties the night before the Germans did.

On 31 May, Colossus (Captain Dudley Pound, yes, this one) was the flagship of the 5th Division, 17th in line from the head of the battle line. The weather was atrocious, but she managed to fire three salvos from at 18:30 at a battleship silhouette, then four salvos at the crippled SMS Wiesbaden at 18:32, then three salvos at Wiesbaden at 19:00, and the destroyer SMS G42, with her secondary armament barking as well. The destroyer escaped hits but not near misses. Her condensers sprung leaks, her speed fell, but she would escape. At 19:10 Colossus engaged several German destroyer flotillas.

At 19:15, she engaged SMS Derfflinger from just 8,000–9,000 yards (7,300–8,200 m), making five salvos with APC shells, claiming four hits (five in reality) destroyed two 15-cm (5.9 in) guns, knocking out two more, causing flooding. She received two shells from SMS Seydlitz at 19:16, but no significant damage apart a fire starting in a few 4-inch propellant charges, put out but 7 men wounded. She later lost a searchlight from shrapnel, 2 men down. At 19:35, she dodged German torpedo attacks. On of her propellers scraped over a wreck at 23:30. The battle ended and she emptied her magazines of just 93 twelve-inch shells (81 APC and 12 CPP) plus 16 four-inch gun shells.

On 12 June, Admiral Gaunt and his ships were were transferred to the 4th BS, Gaunt became second-in-command, still on board Colossus. The Grand Fleet sorties on 18 August after the Hochseeflotte sorties on the southern North Sea, but miscommunications and mistakes made the interception fail. Two light cruisers were sunk by U-boats however, so Jellicoe decided to keep his fleet out of a south exclusion zone, 55° 30′ North. The option for another sortie was kept for a possible German attack in force (like the one planned in 1918).

From June to September 1917, Colossus was refitted, a fate common to most dreadnoughts in turn at that inaction time. In April 1918, the High Seas Fleet sortied to prey on convoys to Norway under strict radio silence so no Room 40 intercepts. This was broken when SMS Moltke was forced to return due to issues, and Beatty (which replaced Jellicoe, “sacked” after what was seen as a near-fiasco at Jutland) ordered the Grand Fleet to sea, too late.

On 21 November she in Rosyth to greet the surrendered Hochseeflotte on 21 November. In January 1919, she became flagship, Reserve Fleet, Devonport. By March 1918 she was flagship of the 3rd the Home Fleet, then to Collingwood on 18 March. On 30 June 1921 she was listed for BU but became a boys’ training ship from September, refitted, stationed in Portland until May 1922. Back to Devonport and disposal she was stricken on 23 July 1923, hulked, TS HMS Impregnable until August 1927, to dockyard control on 23 February 1928, sold to Charlestown Shipbreaking Industries in August, then to Metal Industries, BU from 5 September.

HMS Hercules (1910)

HMS Hercules (1910)

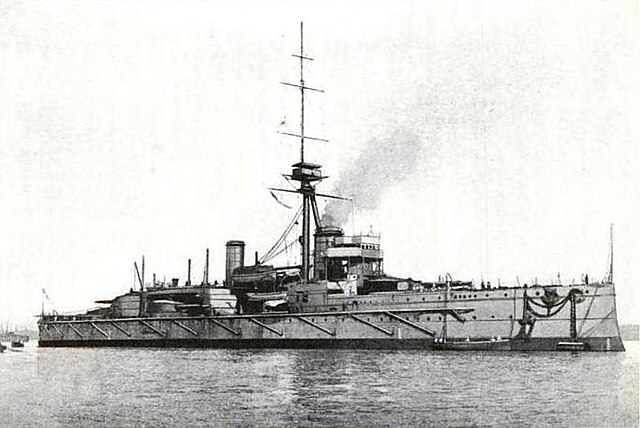

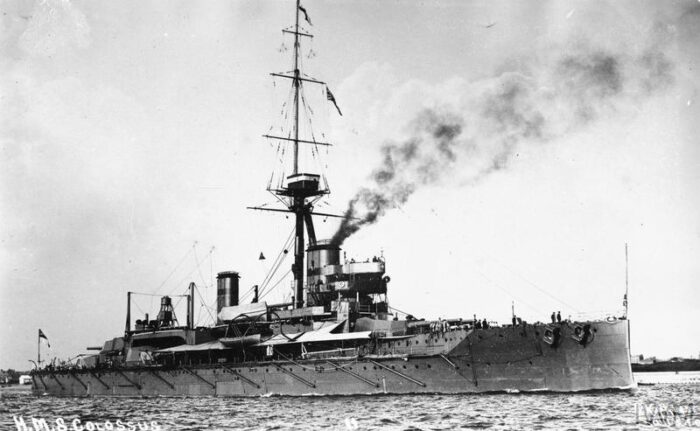

Hercules in 1914

HMS Hercules (after the mythic demigod Hercules, 5th of the name) was ordered on 1 June 1909, laid down at Palmers, Jarrow on 30 July, launched on 10 May 1910, completed in August 1911 for a total cost of £1,661,240 plus armament. She was commissioned on 4 July for trials, with a partial crew. She was recommissioned with a full crew on 31 July, assigned as flagship of the 2nd Division, Home Fleet. On 19 December, VADM Sir John Jellicoe assumed command and she entered the 2nd Battle Squadron (BS) on 1 May 1912. She was at the Parliamentary Naval Review on 9 July at Spithead, refitted at Portsmouth (November–December) and her unit was commanded by Vice-Admiral Sir George Warrender so she was no longer flagship from 7 March 1913, private ship instead for the King. On 22 March, she collided with and damaged SS Mary Parkes of Glasgow in Portland (gale) having minor damage. In May she was in the 1st Battle Squadron.

On 17-20 July 1914 she was in a test mobilisation/fleet review after the July Crisis. In Portland from 25 July she followed the Home Fleet to Scapa Flow 4 days later. Now under the Grand Fleet under Jellicoe she was transferred at Lough Swilly like the rest of the fleet from 22 October to 3 November as Scapa defences were strengthened. On 22-27 November 1914 she was in a sweep in the southern half, North Sea. Next she was at the gunnery drills in the Shetland Islands on 8–12 December. She departed after the Scarborough, Hartlepool and Whitby, too late. Next she was at a sweep in the North Sea on 25–27 December.

She took part in the gunnery drills of 10–13 January 1915 west of Orkney-Shetlands and sortied on 23 January, but missed the Battle of Dogger Bank. On 7–10 March, she was in the sweep in the northern North Sea, and training manoeuvres. Same ib 16–19 March. On 11-14 April she patrolled the central North Sea, same on 17–19 April, and gunnery drills off Shetland, 20–21 April.

Next was another sweep in the central North Sea, 17–19 May, 29–31 May. On 11–14 June, gunnery practice and battle exercises, west of Shetland. Same from 11 July. On 2–5 September, northern end North Sea sweep plus gunnery drills. Training exercises multiplied afterwards, and another sweep from 13 to 15 October and a training operation west of Orkney, 2–5 November.

On 19 March 1916 she saw her turbines repaired over six weeks. On 25 March, she sortied in support for Beatty’s battlecruisers for the Tondern raid, marred by bad weather. She was part of the desmonstration on 21 April off Horns Reef, a distractio for the Russians to lay minefields in the Baltic. On 24 April she refuelled and sailed south after Room 40 knew about an ongoing raid on Lowestoft, but only arrived too late. On 2–4 May, she was part of the same diversion off Horns Reef.

On 31 May, under Captain Lewis Clinton-Baker, Hercules was the 23rd ship from the head of the battle line, 6th Division, 1st BS. In the evening when the battleships at last saw action, she was straddled by 5 shells from a dreadnought at 18:16 and later finished off SMS Wiesbaden around 18:20. She then duelled in the fog with a dreadnought from 18:25, firing 7-8 salvos, always in poor visibility. At 19:12, she duelled with SMS Seydlitz, probably scored two hits. One HE shell penetrated through her upper superstructure (splinter damage) and a second burst on hitting her upper hull armour, causing moderate flooding. Next she was attacked by destroyer flotillas and fired her main guns, hit none. She dodged torpedoes, one being very close. HMS Marlborough, was hit (6th Dv. flagship), lost speed, so the entire division fell behind the main body only catching up after the battle on 1 June. Hercules was unscaved and fire 98 main guns shells (82 HE, 4 APC, 12 CPC) plus 15 shells of secondaries 4-inches.

Post Jutland she was reassigned to the 4th BS as flagship for VADM Sir Doveton Sturdee. She sorties on 18 August to ambush the Hochseeflotte’s advance into the southern North Sea, which was a failure. Hercules however on this occasion, tested a towed kite balloon without observers. Jellicoe after U-Boats attacks, restricted operations, approved by the Admiralty.

On 24 April 1918, she steamed north to Orkney in support of HMS Agincourt and the 2nd Cruiser Squadron to support a convoy to Norway. Meanwhile the Germans sortied, until the operation peterd out after SMS Moltke issues. Like her sister Colossus, Hercules was in Rosyth, Scotland when the surrebdered high seas fleet arrived on 21 November. On 3 December, she carried the Allied Naval Armistice Commission to Kiel in Germany, and back to Rosyth on 20 December. She entered the reserve in February 1919 at Rosyth, on disposal by October 1921. On 8 November, she was sold to Slough Trading Co., resold to a German company by September 1922 and returned in Kiel by October, BU.

Links

Books

Conway’s all the world fighting ships 1905-1921.

Brooks, John (1996). “Percy Scott and the Director”. In McLean, David; Preston, Antony (eds.). Warship 1996. London: Conway Maritime Press. pp. 150–170. ISBN 0-85177-685-X.

Brooks, John (2016). The Battle of Jutland. Cambridge Military Histories. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-15014-0.

Burt, R. A. (1986). British Battleships of World War One. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-863-8.

Campbell, N. J. M. (1986). Jutland: An Analysis of the Fighting. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-324-5.

Colledge, J. J.; Warlow, Ben (2006) [1969]. Ships of the Royal Navy: The Complete Record of all Fighting Ships of the Royal Navy (Rev. ed.). London: Chatham Publishing. ISBN 978-1-86176-281-8.

Halpern, Paul G. (1995). A Naval History of World War I. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-352-4.

Jellicoe, John (1919). The Grand Fleet, 1914–1916: Its Creation, Development, and Work. New York: George H. Doran Company. OCLC 13614571.

Massie, Robert K. (2003). Castles of Steel: Britain, Germany, and the Winning of the Great War at Sea. New York: Random House. ISBN 0-679-45671-6.

Parkes, Oscar (1990) [1966]. British Battleships, Warrior 1860 to Vanguard 1950: A History of Design, Construction, and Armament (New & rev. ed.). Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-075-4.

Preston, Antony (1985). “Great Britain and Empire Forces”. In Gray, Randal (ed.). Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships 1906–1921. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. pp. 1–104. ISBN 0-85177-245-5.

Silverstone, Paul H. (1984). Directory of the World’s Capital Ships. New York: Hippocrene Books. ISBN 0-88254-979-0.

Tarrant, V. E. (1999) [1995]. Jutland: The German Perspective: A New View of the Great Battle, 31 May 1916. London: Brockhampton Press.

Links

http://www.navweaps.com/Weapons/WTBR_PreWWII.php

https://www.jutlandcrewlists.org/colossus

https://www.worldwar1.co.uk/battleship/hms-colossus.html

https://www.maritimequest.com/warship_directory/great_britain/battleships/colossus/hms_colossus.htm

The Colossus class Battlehips on wikipedia

On the Dreadnought Project

Gallery

HMS Hercules

HMS Colossus

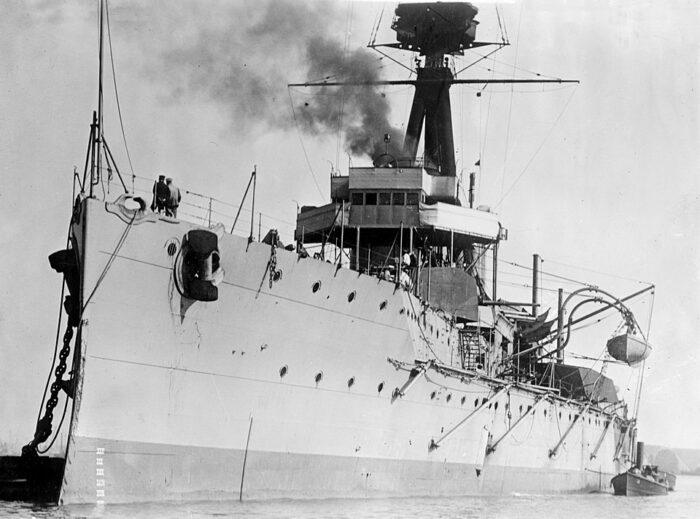

HMS Colossus later in her career, showing her stern.

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign