United Kingdom – 19 Hybrid Merchant Escort Aircraft Carrier (1942-45): MV Empire MacAlpine, MacAndrew, MacCallum, MacDermott, MacKendrick, MacRae; MacCabe, MacColl, MacKay, MacMahon; MV Acavus, Adula, Alexia, Amastra, Ancylus, Gadila, Macoma, Miralda, Rapana.

United Kingdom – 19 Hybrid Merchant Escort Aircraft Carrier (1942-45): MV Empire MacAlpine, MacAndrew, MacCallum, MacDermott, MacKendrick, MacRae; MacCabe, MacColl, MacKay, MacMahon; MV Acavus, Adula, Alexia, Amastra, Ancylus, Gadila, Macoma, Miralda, Rapana.

Although not the best-known aircraft carriers, MAC-ships (Merchant Aircraft Carriers, to not mix with the Merchant Armed Cruisers) illustrated the most extreme form of conversion dictated by circumstances: Those of the “Battle” of the Atlantic. Perhaps less extreme than CAM-ships and their expendable “Hurricat”, MACs were an emergency, compromise solution between lacking escort carriers, and the need to keep supply running, notably both vital oil and grain. Thus, the idea of a very austere conversion of merchant vessels as carriers flush deck essentially for a small utility deck and nothing else emerged in 1941. Gone were the hangar, catapult, lift or even workshop as in a true aircraft carrier.

This ensured the holds below the deck would remain fully operational. In a sense, HMS Audacity in 1941 was a model. In all, 19 were built in three relatively close series. They only carrier four aircraft at best, most often the Fairey Swordfish, a dependable and versatile but slow moving beast of burden, the perfect match for their small deck and rough conditions. There were the Empire “clans” both grain and oil carriers, and Gadila class oil tankers, operated by merchant crews and companies. AA crews however came from the Navy, as one liaison officer, and the pilots and personal from the Fleet Air Arm, quite a unique case in the annals of the war at sea. #ww2 #aircraftcarrier #MACships #merchantaircraftcarrier #royalnavy

Development

The Civil ensign sported by the British merchant marine in WW2

The idea of a cargo ship which was topped by a flight deck emerged in 1940 already, with a few aircraft parked at the rear ready to take off on the available runway length (fairly short). It emerged as a perhaps more sensible solution than the CAM-ships and their Hurricane thrown away. CAM ships could still carry their cargo, and so would the conversion be able to do the same, albeit requiring more time to access the holds. So as it was really unpractical to cover these with a deck and then removed panels for access each time, it was soon more practical to have the ships requisitioned for such conversion being bulk carrier, so to be able to just pump hold contents in and out using pumps. That way, the deck could stay permament.

Slattery’s 1940 proposal

In 1940 Captain M. S. Slattery RN which was the Director of Air Material at the Admiralty, proposed a scheme to converting merchant ships into aircraft carriers in the wake of the CAM ship project. The deck would be limited to just two arrester wires and a safety barrier. He dubbed it the “auxiliary fighter carrier” and at the time the priority was to hunt down attacking FW 200s so optimistically six Sea Hurricane (still at design stage at the time) would be ready, while the ships retained its cargo-carrying ability. But the opposition, surprisingly, did not came from the admiralty but from the Ministry of Supply in charge of the merchant fleet.

They estimated that combining a merchant vessel and and an aircraft carrier and having the best of their respective roles would be too complicated. They did not thought at first about the depht of the conversion, nor if it would be bulk or standard cargo. Probably having the mental image of an HMS Ark Royal. Instead of hap-hazard hybrid merchant-warships it was preferred to make a full and definitive conversion into fully-fledged warship. The program name remained the “auxiliary aircraft carrier” and to not tax regular merchant vessels stocks it was decided to use recently confiscated German ships, notably Hannover, which was already impressed as “Empire Audacity” later HMS Audacity, in June 1941. More conversion would follow over the years (Vindex and others), but after entry into the fray of the US, via lend-lease dozens of large, valuable and recent C3 conversion carriers took the bulk of this auxiliary fleet. All this took time however.

1942’s merchant fleet take on the concept

Poster on the merchant fleet, “war effort, under the red duster they sustain our island fortress”

The hybrid concept nevertheless resurfaced in early 1942 as the U-boat rampage not only greenlighted the MAC-ships, but open more emergency channels, escort carriers building in the UK was marred by already overworked yards, whereas US production was not on par. Delays upon deliveries were up to six months and more. The war in the Atlantic could be lost in between.

It is not certain who made the idea surge again, but Captain B. B. Schofield of the RN (Director of the Trade Division) and John Lamb (Marine Technical Manager, Anglo-Saxon Petroleum Company) are credited to have brough the idea forward again. Sir James Lithgow as Controller of Merchant Shipbuilding and Repair owning Lithgows Ltd shipbuilders had a runion and drafted a consistent design concept to vanquish growing Admiralty reservations over the MAC concept. Another perceived limitation was indeed the use of RN crews and FAA pilots that could be better performng on regular vessels, and confusion of command when mixing both merchant logic and admiralty orders.

Lithgow sketched the rough design on the back of an envelope apparently, offered this admiralty contact to convert two ships for a start on private funds on condition not to be interfered with by the Admiralty during the design and construction phase. His deputy Sir Amos Ayre was the Director of Merchant Shipbuilding, and was already informed about the project back May 1942, drafting specs, but later credited Sir Douglas Thomson of Ben Line and the Ministry of War Transport for the idea instead. Slattery was all but forgotten.

Admiralty resistance (1942)

Resistance from the admiralty pointed out air operations from a short and relatively slow ship, that generally helped by taking a face wind for surtentation. The Admiralty considered anything below a flight deck length of 460 feet (140 m) was required to ensure safety bot for taking-off and landings at 15 knots (28 km/h; 17 mph). Since they needed to divert course to take the wind and regain the convoy, speed needed another margin, not to be distanced by regular convoy speed. So many estimated tankers, the most probable conversion, between their low freeboard, ponderious allure and and volatile cargo would be ill-suited. But as these exchanged went on, the U-boat in the summer 1942 turned to the absolute worse. Both off the US coast where U-Commanders had their “happy times” and closer to home were wolfpacks were numerous and active, assets still lacking. In the end, and perhaps after some pushing by Churchill himself, emergency made this convoy air support all the more useful whatever the form it takes. Instead of an oiler a stadard of modern and fast grain ship variant was accepted by the Admiralty as a starting base.

Official approval, US resistance

September 1942 had the Admiralty now enthusiastic about the program and asking for fifty MAC ships available the next year as soon as practicable. They were needed at least two or three for each passing North Atlantic convoy, by October this was even raised to 52. But that proved too ambitious and was soon back to 40 when formally sanctioned by the War Cabinet in October 1942, and requited obvious American help. The US were asked to convert 30 MACs for the first half of 1943, but the more caution Navy Department committee considered the request too experimental in natureaznd turned it down. As it happened, the plan B called for at least some to be converted back home in British shipyards.

Conversions

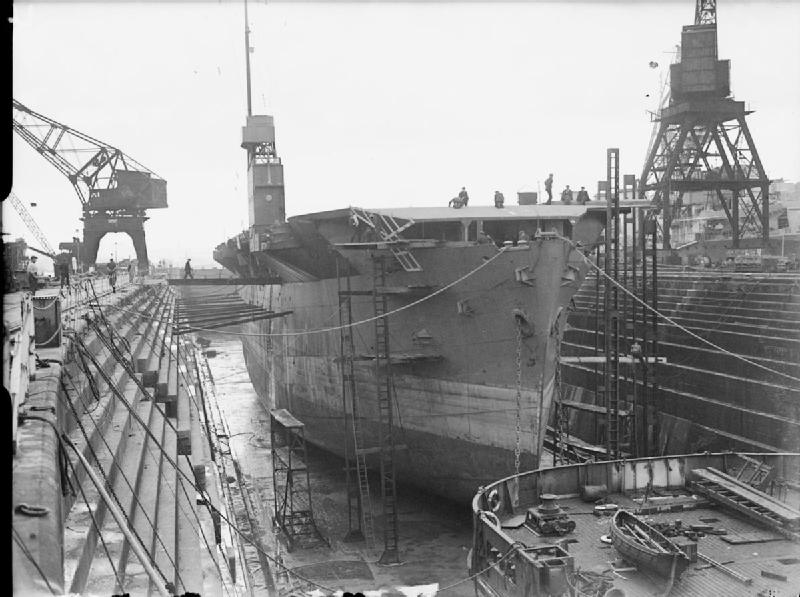

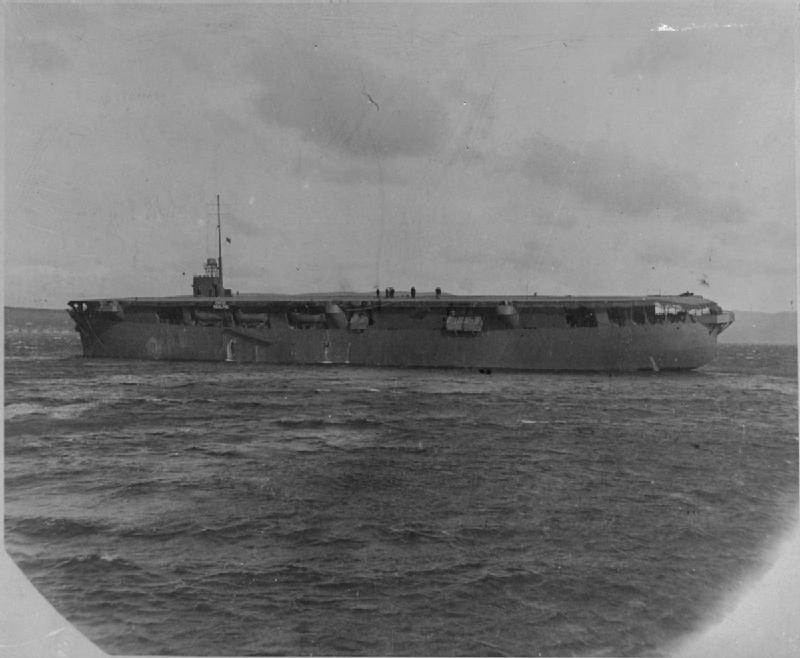

MV Empire MacAlpine in drydock

The other essential feature what these ships were bulk carriers, still used to carry cereals and oil. These were the “grain group” standard “empire types”, MacAlpine, MacKendrick, MacAndrew, MacDermott, MacRae, MacCallum requisitioned in December 1942 and converted, the last in January 1944. They were slow (12.5 knots, as equipped with a sober diesel) so a clear operational limitation, had limited AA, and only 4 planes, but they were stored in the only small hangar/workshop (7.30 m under ceiling), and served by a lift. None of these ships were lost in battle, and they brought as a bonus to their vigilant defense the American wheat from the Great Midwestern plains to British bakers.

The second series of MAC-Ships concerned tankers. There were 13 ships, the Empires MacKay, MacColl, MacMahon, MacCabe (1943), and “flowers” serie, the Acavus, Adula, Amastra, Alexia, Ancylus, Gadila, Macoma (the last two under the Dutch trading flag), Miralda, and Rapana. They were a little taller than grain carriers, better armed, but had neither hangar nor lift, being even more autere to keep their precious oil capacity intact. Their flight deck was however longer (137 meters or xxx feet) and all their aircraft were stored aft enduring all weather. The last came into service at the end of 1944. None were lost at sea and in 1945, their facilities and runway were removed and after a brief overhaul and they regained their simply deposed civilian infrastructure back, returning to their original activity.

The originality was they served under merchant flag (Red flag, State Merchant Navy) with civilian crews under contract, apart from the naval officers and sailors of the Royal Navy who were responsible for the AA, the pilots and mechanics. The planes themselves could also bear the red sign of the shipping company rather than the classic “Royal navy” on their fuselage. This was usually for each vessel, 1-2 Sea Hurricanes and/or 2 to 3-4 Swordfish.

About the “Empire class”

Empire ships were merchant vessels renamed as such as they were now in service of the Government of the United Kingdom, directly under supervision by the Ministry of War Transport (MoWt) which technically owned them, contracted their operation to various shipping companies which were part of the prewar British Merchant Navy.

Empire ships were merchant vessels renamed as such as they were now in service of the Government of the United Kingdom, directly under supervision by the Ministry of War Transport (MoWt) which technically owned them, contracted their operation to various shipping companies which were part of the prewar British Merchant Navy.

Empire ships were differing so much that speaking of a “class” is simply a shortcut. They were new constructions, captures and seizure. The MoWT obtained from the US to increase their shipping capacity due to U-Boat losses and asked for a tonnage sufficient to support globe-spanning Britain’s sea comunication lines. They not only differed by provenance but type as well being freighters, tankers, fast cargo liners, or even later converted as tank landing ships, deep-sea salvage and rescue tugs, and diverged withing each type but were hundreds under the MoWt flag.

They supplemented Britain’s normal peacetime merchant fleet and eventually reached some 12,000, making this the world’s largest merchant ship, with 4,000 lost as per the British register during the war, the bulk of these during the Battle of the Atlantic.

Among them, the Tankers were divided into three types:

The ‘Ocean’ type or ‘Three twelves type’ (12,000 tons deadweight, 12 knots, VTE engine or diesels, and gobbling 12 tons of fuel daily. They were also used for refuelling at sea.

The ‘Norwegian’ type were slightly larger, made by Sir James Laing & Sons Yard in Sunderland (prototype) and Furness Shipbuilding Co, Ltd. The prototype had two 3,800 horsepower (2,800 kW) triple expansion steam engines with the production ships havinf 3,300 horsepower (2,500 kW) diesel engines, and at the end of the war, 4,000 horsepower (3,000 kW) diesel engines. The need to augment speed was paramount as a survival trick facing U-Boats

The ‘Wave’ fast tankers were introduced in 1943n capable of 15 knots (28 km/h) so much so they also operated outside convoys. and

Catapult-armed merchantmen or CAM ships, 27 Empire ships were requisitiond and converted as such (Plus Eight requisitioned private ships) to provide important convoy cover as no air cover was available when ten Empire ships lost in service.

Design of the class

Hull and general design

Nice cutaway model of a Grain carrier, HMS Empire McAlpine, src Royal Museum Greenwhich

Since they were conversions of three different hull types, specifications and details are explained later in this post. But basically the project started with grain carriers of the “Empire” class.

In general, the Grain carriers were the smallest of the three, at 7,950 GRT standard – 8,250t Full Load but limited to 12.5 knots. The grain had the shorter flight deck, 413 feet (126 m) up to 424 feet (129 m) ft for a breadth of 62 feet (18.9 m) but unlike the others, they had a built-in small hangar on the lower deck and a lift while being able to accommodate four Fairey Swordfish aircraft inded, wings folded. For maintenance on the long run it was a gift, but they were the most tricky to operate.

The oil tankers conversions had longer flight decks up to 461 feet (141 m) but no hangars and in general only three Swordfish stowed at the aft end. The pilots still had more manageable distances to take off or land. Neither had catapults.

They had the “standard tramp hull” for the Admiralty’s revised requirement asking for flight deck of not less than 390 feet (120 m) in length, 62 ft (19 m) in breadth and in practice they ended at between 413 and 424 ft (126 and 129 m) and for the tankers c460 ft (140 m) but there were still minor variations for individual ships.

On the grain carriers, the main engine was a massive diesel located right amidship for stability. On either sides were located four grain holds separated by bulkheads, reinforced by structural pillars. The lift was located aft, and the hangar started from there to about 45% of the the center of the ship aft. It was tall enough for models larger than the Swordfish, and four could be stowed, wings folded beneath the lift. The RN personal was located in forward accomodations, with two-story tall open airt separations betwen structures under the deck. The port side island was located on a sponsonsed platform to free the flight deck. The island had a map deck, open bridge deck, a rear platform for the main fire control of the aft poop sponsoned main gun, and a pole mast with limited sensors.

Structural changes

The largest modifications concerning the flight deck was their supporting structures were arranged in sections, three on the grain carrier, four ib tankers with expansion joints between each. The flight deck was at the level of the wheelhouse and on the yard tankers had indeed their existing wheelhouse and funnel being removed, the space under the flight deck housing arrester gear mechanisms and four wires plus on tankers a trickle wire and safety barrier. There was still for command and control a small island structure with bridge above, wheelhouse below, but in the tankers this was a chartroom/pilots’ briefing room. Under the deck were also rather forward, accommodation for 107 crew (50 more than normal, navy personal dedicated to AA guns and FAA perosnal).

There were also an improved internal subdivision with additional ventilation, exhausts truncated to vent to the leeward side. The lifeboat position were changed and work was done, by default of having armour to safely protect bombs, depth charges, ammunition and pyrotechnics magazines buried inside the ship. The grain carries had their armament sponsons encroached onto the flight deck area and tey could not use commercial berths, whereras tankers could as their “zarebas” were extended outboard. A single amidships center cargo tank carried Avgas on the tankers, but on grain carriers, that was a special compartment with two pressurised fuel tanks, control room and piping.

The Grain carrier’s hangar was an enormous advantage, and it extended on three after holds, measuring 142 ft (43 m) long and 38 ft (12 m) in width, while being of generous height at 24 ft (7.3 m) so not only the four Fairey Swordfish could be stowed wings folded with room to spare, but spare parts could be suspended above as well. The elevator platform was stronge enough to lift a filluy loaded and prepared for flight Swordfish on deck in a minute, followed by an immediate taking off, then a new one. On Tanker such feature was impossible due to the very extensive structural alterations needed and large reduction in cargo capacity for a more vital supply. Normal provision was three aircraft, not four, due to limited parking space aft and normally on the forward end with a collapsible safety barrier raised in operations. In addition the decj was equipped with hinged side screens around the aft end of the flight deck to try to gain weather protection but this was never sufficient, neither were the aircraft being wrapped in canvas. Wear and tear was enormous and maintenance conditions appealing.

Powerplant

The initial requirement was to keep their standard diesel tramp engine which developed 2,500 bhp (1,900 kW) for 11 knots (20 km/h; 13 mph) but the admirakty revised these for practical flight operations and the new-built vessels had 3,300 bhp (2,500 kW) diesels instead. In practice max speed when loaded was below 12 knots.

It diverged between ships, the grain carriers having 1 shaft propeller, two Burmeister diesel for 8,500 shp total and 12.5 knots (max trials), and the Empire MacCabe Oil Tankers had the same. However for the next “3-12” clasS tankers, they had a single shaft but two diesels 4-cylinder MAN rated for 4,400 hp each, so 8,800 total, for the same top speed of 12.75 knots. Again, this speed was a problem in convoy operation as the ship to launch, due to their small deck, had to face the wind, and this often meean taking a new bearing out of the convoy route. After each launch, they had to come back in line, whereas the convoy speed of average was around 10 knots. For this reasons they were deployed with the medium (9–10 knots) and especially slow (4–7 knots) convoys, carrying less valuable cargo than military hardware. All these ships had a single propeller and rudder, merchant type. The diesels ensured quick operations and took less space than VTEs.

Empire MacCabe diverged by having a Doxford diesel, Empire MacColl and Empire MacKay had a Burmeister & Wain diesel and Empire MacMahon a Werspoor diesel, the Rapana class had all Sulzer diesels but Gadila which a MAN diesel.

Armament

It was uniform across the board between classes thanks to the admiralty setting a standard: One 1x 4-in QF MK IV (102mm) main gun located on a platform or sponson at the poop for max fire arc, and a variable number of Bofors and Oerlikon light AA guns. This diverged between ships, as well as their locations. Generally the bofors 40mm (two for the Grain carriers) were located forward and aft oin sponsons, including one at the step of the island. As for light AA they had generally four single 20 mm under masks. This was, for their size, light but sufficient against a limited Luftwaffe activity from 1944.

Grain Carriers: Two 40/56 Bofors Mk I/III, four single 20mm/70 Oerlikon Mk II/IV plus 4 Swordfish

Tankers, Empire MacCabe & MacMahon: No bofors, eight single 20mm/70 Oerlikon Mk II/IV and 4 aircraft

Empire MacColl and Empire MacKay same but three Swordfish.

Gadila class: Two 40/56 Bofors Mk I/III and six 20mm/70 Oerlikon Mk II/IV, 4 Swordfish

4-in QF MK IV (102mm)

The The QF 4-inch gun Mk IV was a WW1 vintage ordnance found on most Royal Navy destroyers, introduced in 1911 to replace the BL 4 inch Mk VIII gun. 1,141 of these QF guns were produced and 939 still available in 1939, many removed from ships that went to the scrapyard. Mk XII and Mk XXII variants went on submarines. Being surplus guns essentially they were ill-suited for AA fire and mostly were used for ship-to-ship or in that case, U-Boat defence although it was capable of 30° elevation.

⚙ specifications 4-in QF MK IV |

|

| Weight | 2,750 pounds (1,250 kg) barrel & breech |

| Dimensions | 160 inches (4.064 m) bore (40 calibres) |

| Elevation/Traverse | 250°+ aft, CPIII Mount -10° to +30° |

| Loading system | Horizontal sliding-block |

| Muzzle velocity | 2,370 feet per second (720 m/s) |

| Range | 11,580 yards (10,590 m) at +30° |

| Guidance | Visual, radar/FCS assisted |

| Crew | 7, no shield |

| Round | Separate QF 31 pounds (14.06 kg) 4-inch (101.6 mm) |

| Rate of Fire | |

Sensors

It was the same across the board, nominally light short range radars since they had a small pole to carry them.

Type 271 radar

The Type 271 was a surface search radar, using a microwave-frequency system, with an antenna small enough to be mounted on small ships, and there on the small island. It could pick up a surfaced U-boat at around 3 miles (4.8 km) or its periscope at 900 yards (820 m).

Developed ASRE, produced by Allen West and Co, Marconi in service in 1941 this 28 in (0.71 m) 5-70 kW sea-surface search, early warning radar had a Frequency of 2950 ±50 MHz (S-band), a PRF of 500 pps, Beamwidth of 8.6º horizontal, 85º vertical, Pulsewidth of 1.5 µs, 2 rpm for a 1 to 11 NM (1.9–20.4 km) range. Azimuth went from 220 to 360º at a precision of ~2º, 250 yards range.

Type 279 radar

The 1940 Type 279 was a 70 kW metric early-warning set with separate transmitting and receiving antennas (combined on Type 279M) with secondary surface-search mode and usable for aerial gunnery using a precision Ranging Panel to pass accurate radar ranges to the HACS table with an analog computer. Data: FRQ 43 MHz PRF 50/sec., Pwdt 7–30 μs, RA 50 nautical miles (93 km; 58 mi)

Air Group

Fairey Swordfish at an airshow in 1988 to the colors of ‘L’ Flight, 836 NAS, HMS Rapana.

The bedrock of these small air groups were half-squadrons equipped with the very dependable Fairey Swordfish.

Not much to say on that chapter. All thse carriers had betwene three and four Fairey Swordfish, the only really suited for these small decks. Bery robust and reliable, it had a low landing speed ideal for tough conditions imposed by these small dancing decks on the North Atlantic. The basic task of these planes was anti-U-boat reconnaissance and strikes, armed with depth charges.

Initially the Director of Trade Division wanted a new headquarters organisation to oversee MAC ship aviation and the Director of Naval Air Organisation disagreed as he saw these ships as an addition to the main escort carrier programme and argued there were to be few, if any aircraft and crews available for them, but when HMS Dasher exploded and sank in March 1943 a whole Swordsfish squadron not onboard was freed, split up by June, with a first section of No. 836 Naval Air Squadron assigned to MV Empire MacAlpine as commissioned, flying to Belfast with nine aircraft, so enough for at leat two MAC ships plus spares but also intended to redill the common pool for escort carriers. 836 NAS was relocated at RNAS Maydown in County Londonderry and the MAC ship headquarters formed there. 840 NAS was partly detached to MV Empire MacAndrew until becoming the M flight of 836 Squadronn August 1943. At Maydown was located the very unique Royal Netherlands Navy No. 860 Naval Air Squadron assigned to Gadila and Macoma.

The same as above, in flight today.

Fairey Swordfish landing on the deck of the Empire MacKay in the North Atlantic in 1944, note the landing signaller to the left

Discussions about aircraft types soon ended with the Fairey Swordfish Mks. II and III as the most obvious choice due to the very challenging conditions. The Hurricanes not only were too heavy and fast for these small decks, but in 1943 the Luftwaffe was no longer such a threat over the Atllantic. Still, the flight deck was just 16 ft 6 in (5.03 m) wider than the Swordfish wingspan. When used to hunt down U-Boats loaded with RP-3 rockets and depth charges these often needed rocket-assisted take-off gear (RATOG) to launch when the ship could not divert in the wind, or the latter was adverse. Tankers routinely carried four aircraft such as the Dutch MACs Gadila and Macoma but it was rare on British tankers. Famous Captain Eric “Winkle” Brown made a trial with a Martlet on MV Amastra in October 1943 for operations in the Pacific but that prospect was later cancelled.

HMS Empire MacAlpine, 1943

⚙ specifications Empire MacAlpine, grain bulk carrier |

|

| Displacement | 7,950 GRT standard – 8,250t Full Load |

| Dimensions | (136.5 x 18.3 x 8.1 m) |

| Propulsion | 1 shaft propeller, Burmeister diesel, 8,500 shp. |

| Speed | 12.5 knots |

| Range | c1000 nm |

| Armament | 1x 4-in (102mm), 4×1 40mm AA, 4×1 20 mm AA |

| Protection | None |

| Sensors | Type 271, 279 radars |

| Air Group | 4 aircraft, Fairey Swordfish |

| Crew | 107 |

⚙ specifications Empire MacCabe Oil Tankers |

|

| Displacement | 9,000 tons deep load |

| Dimensions | Same as above |

| Propulsion | Same as above |

| Speed | 11 knots |

| Range | Same as above |

| Armament | 1x 4 in (102 mm) QF MK IV, 8×1 20 mm Oerlikon AA cannons |

| Protection | Double hull |

| Sensors | Type 271, 279 radars |

| Air Group | 3/4 aircraft |

| Crew | 122 |

They were tailor-built and entered service in October–December 1943, operated by the British Tanker Company except Empire MacKay, by Anglo Saxon Petroleum. Like above, they lacked any hangar, lift, catapult, but had arrestor cables while the aircraft were maintained and stored on deck.

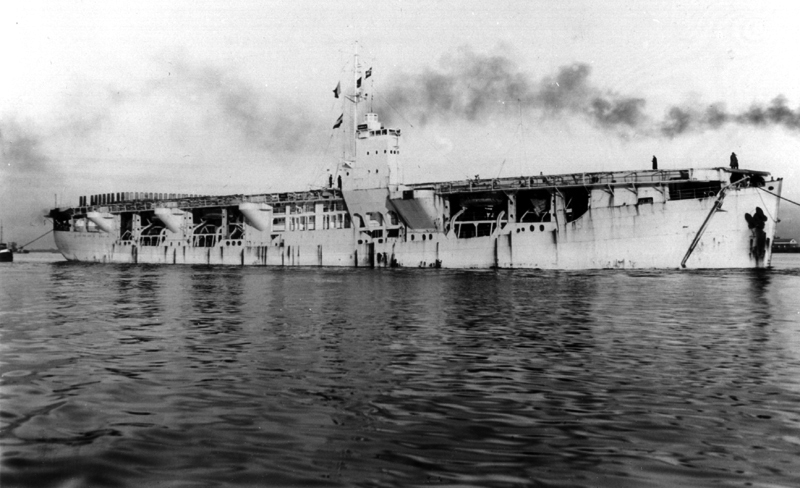

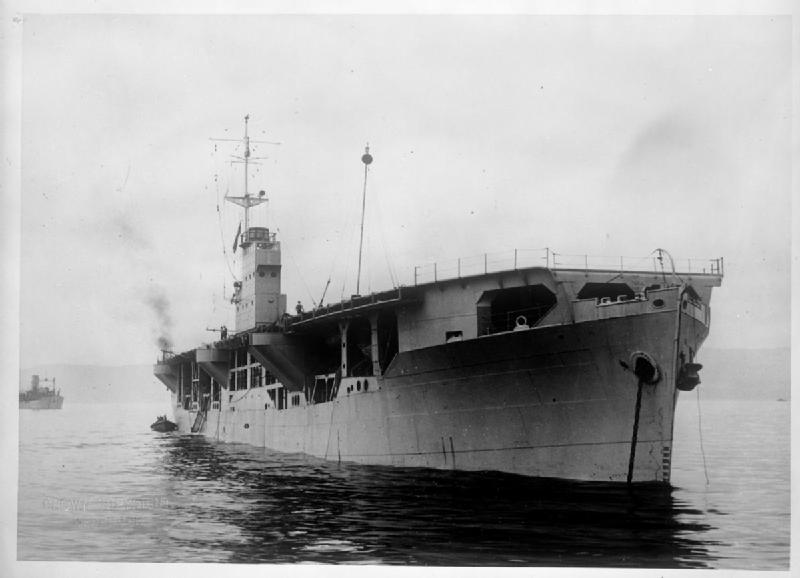

HMS Rapana in 1944

⚙ Macoma Oil Tankers class specifications |

|

| Displacement | 8,000 standard – 8,250 GRT Fully Loaded |

| Dimensions | (141.12 x 18.08 x 10.32 m) |

| Propulsion | 1 shaft diesel 4-cylinder MAN, 4400 hp |

| Speed | 12.75 knots |

| Range | Same as above |

| Armament | 1x 4-in, 2x 40 mm Bofors, 6x 20 mm Oerlikon AA |

| Protection | None, double hull |

| Sensors | Type 271, 279 radars |

| Air Group | 4 Fairey Swordfish |

| Crew | 54 crew, 64 air crew and AA |

The conversion: Tradeoffs and peculiarities

The first two MAC ships were ordered in June 1942 at Burntisland Shipbuilding Co. Firth of Forth, and William Denny & Brothers, Dumbarton. They were not “conversions” but brand-new grain ships not even laid down when the decision was made, named Empire MacAlpine and Empire MacAndrew, the first launched on 23 December 1942 and completed on 21 April 1943 for a total of 11 months. Five more followed, Empire MacAndrew, Empire MacRae, Empire MacCallum, Empire MacKendrick and Empire MacDermott every two months, the last (MacDermott) commissioned by March 1944.

By late September 1942, so three months after the laying down of the first Grain carrier, decision was made to convert tankers as well, given two arguments: The longer flight deck, and better supposed stability due to the higher underwater load. Four new-build tankers were thus marked for conversion, but they were only started by May 1943 so the lead ship, HMS Empire MacKay, only entered service in October 1943 followed by Empire MacCabe, Empire MacMahon and Empire MacColl by November 1943. Next, since the need for new tankers was also urgent, it was decided for the follow-up to existing ships of a similar design. By early 1943, the Anglo-Saxon Petroleum Company offered its entire fleet of ‘Triple Twelve’ tankers for conversion, and they became the Rapana class.

By January 1943 the Ministry of War Transport asked the Norwegian government-in-exile of they could also provide extra ships (the country had a the world’s second largest merchant fleet at the time) designated the Norwegian tanker B.P. Newton for conversion under British command. But Norway insisted on financial arrangements described at the time as “wholly unreasonable as between allies” until proposal foundered in relation of the design effort for this one-off conversion.

Final chapter, three tankers of the same class of ‘Triple Twelves’ under Dutch registry as Anglo-Saxon Petroleum was a subsidiary of Royal Dutch Shell led the admiralty to contact the Netherlands authorities. The latter accepted in condition these new MAC ships, would fly the Dutch flag, under Dutch civilian command. This was agreed with reserves. Only two were concerned, MV Gadila and Macoma, with Dutch merchant crews, while the aircraft flights were from the unique Royal Netherlands Navy 860 Naval Air Squadron. They became in practice Netherlands’ first “aircraft carriers” before HtMs Karel Doorman in the 1960s.

This conversion of course had consequences on these ships’s carrying capacity, the preservation of which was a crucial selling point. This caused a reduction in cargo capacity of 10% on tankers, which was preferrable due to the nature of their cargo, but 30% on grain ships to gain a hangar, quite a tradeoff. Conversion were done with standardised designs and steel all around 51% prefabricated components, for a conversion time in five months with new-builds requiring 14 weeks and from existing vessels 27 weeks and variations as Rapana took five months and Macoma ten. Labour issues and dacing shipyard priorities as well as delivery of arrester gear (in high demand) bottlenecked timely delivery.

For their trading role, operation under Ministry of War Transport with daily management by owners or shipping companies whereas all military aspects were controlled by the Admiralty, which urged the creation of a dedicated section, the Trade Division DEMS Air Section for efficient co-ordination.

MAC Ships in service

Tough Conditions

An image of the conditions aboard tankers assigned to the Arctic Convoys: pilot posing near maintenance personal trying to maintain flying Swordfishes open to the elements on MV Ancylus. They had often to de-ice the palisades seen in the background to keep stability. The latter were supposed to reduce seawater spray, but this was not very successful in heavy weather.

This conversion was a quite extreme one, and as a result, operating conditions were equally extreme. First off, the planes, usually the Fairey Swordfish, as the more modern Albacore was too heavy for the job. The Swordfish were generally no more than three, as ideally two were at the very aft of the deck, wings folded and the third, wings unfolded and ready to take of at all time. In case of heavy weather to avoid seawater corrosion, they were strapped all three wings folded under waterproof tarpaulins but this was never enough.

When the Swordfish designated for patrol took off, depending of the needs, another was unfolded and launched, eventually all three, and then they landed in turn. If just one, to land the deck parked Swordfish had to be moved all the way to the other end of the deck and then all three replaced aft. Manoeuvers that half to be done while often waterspray and the ship rolling and pitching.

These ships left the convoy to position themselves in the wind to launch. One can easily imagine the problem of managing these planes securely moored to the runway. When MACs operated in the arctic to Murmansk, frost set in and packed ice had to be chiselled down to free the planes trapped solid in their tarp. For maintenance, everything had to be brought to the deck by hand from the holds as there was no lift. Operation of the ship was difficult also, albeit there was at least a small open bridge. There was no other options for these ships to carry grain or oil, since the holds were condemned. Instead pumps systems were managed to load and unload them.

Strange crew peculiars

As crews relations went with FAA and RN personal, this could be complicated, although between great care done to setup coordination and general good will, efficiency prevailed. MAC ships never appeared in Royal Navy Lists officially, and instead of commissioned officers they were commanded by regular merchant captains. It was clear they were to operate as merchant ships under the Red Ensign like CAM ships at first, although the Admiralty wanted them used as regular warships initially. With personnel lacking, a compromise was achieved, so that these would be civilian-manned. This was objected still by the Foreign Office that they would fall as warships under international law as under the 1907 Hague Convention the crews could be assimilated as “francs-tireurs”, remembering the execution in 1916 of Captain Charles Fryatt, ram a U-boat with his cross-Channel ferry and captured. The War Cabinet started:

The greater the effect of air action on the U-boat campaign, the more the enemy may be tempted to try to damage the morale of M.A.C. crews by court martialling and shooting any Merchant Service personnel they may capture from such ships.

Best solution was to have them operating under the Red Ensign, with unions cooperating about the risks involved and capture being avoided by any means. By September 1944, masters were still reminded to remind their crews to maintain secrecy on the ships the operated, which was required for the military and not for them in normal times.

As for the small air party responsible for flying/maintenance, it was headed by lieutenant commander RN/RNVR actiing as Air Staff Officer and master’s main adviser on aviation matters, as well as a pilot, observer and air gunner for each aircraft (generally 9) three signalmen and five communications and armament ratings plus 17 aircraft fitters. The defensive armament was manned by a detached DEMS team RN or Royal Artillery personnel of 50+. They all acted as “supernumerary crew members” with a nominal payment of a shilling per month and a daily beer, wearing on their uniform a small Merchant Navy badge.

Service arrangements

These MAC ships started with the North Atlantic route and were seen in ‘ON’ and ‘HX’ convoys, and the tankers were intended for CU convoys between the UK and Curaçao. But this was rejected as these vital convoys only used fast tankers to avoid Uboats so they ended on the North Atlantic route, to New York City, to have them run between Halifax and New York already under protection of land-based aircraft. The “oil pool” of Halifax was thus created for tanker MACs for loading, grain MACs using there, their bulk loading facility. On the other end, the the Firth of Clyde became the sole UK terminus for all MACs as it had good aviation training facilities. It took often more than a week to unload a MAC in Glasgow, grain MACs were diverted to Alexandra Dock in Liverpool which had two facilities to unload in thirty-six hours. Tankers unloaded at the Clyde or Mersey facilities.

Assessment

In the end, for immobilizing from 5 to 10 months a ship that could have carried multiple times oil and grain in the meantime, was it worth it ?

When joining the Battle of the Atlantic in mid-late 1943 and 1944, the tables had turned towards the Allies’ favour and in early 1944 all convoys to North America (ON) and Halifax convoys (HX) and to British Isles comprised a MAC ship, sometimles two or three. Swordfish made still countless patrol flights and operated dozen of attacks but never scored a kill on any U-boat even after 4,000 sorties but the admiralty overall was satisfied of their very presence to prevented development of any concentration of U-boats close to the convoy. It should be noted that they always operated by day, since night capable air crews were too rare and valuable and kept to the Fleet Carriers. No air coverage by night so.

MAC ships prevented indeed many U-boat attacks despite their lackluster records. Still, even in convoys protected by MACs, six merchantmen and three escorts were sunk in ONS 18/ON 202, notably while Empire MacAlpine was there, as well as two merchantmen and an escort from SC 143 with Rapana being present. Still, countless other ships were saved by the active deterrence brouight by the daily patrolling “stringbags”, a valuable contribution to the Battle of the Atlantic. Merchant ship masters even cheered when hearing about a MAC joining their convoy. Indeed, regular escort carriers were present also, but in 1944 were often detached or operated far from the convoy in hunter killer groups, whereas MAC ships always stayed with the convoy.

Early in 1944 MAC were intended to carry more than 500 aircraft awaiting shipment in the US, and indeed many MAC ships made such ferry crossings in addition of carrying oil or grain, especialy when carrier strnght withing a convoy was sufficient enough. By September 1944, a few MAC ships tankers started to be used for refulling at sea always fuel-hungry escorts using a hose streamed over the stern. At that stage, the admiralty saw the Atlantic convoys war won, and MAC ships no longer required. Discussioned about to use them in the Pacific notably as supply vessels and fleet oilers ended short due to cost-effectiveness issues. By September and October 1944 MV Acavus, Amastra, Ancylus and Rapana were taken out of service, sent in yards to be reconverted as conventional merchant ships at a cost of £40,000 each. The remainder were also discharged by May 1945. So their war would have lasted for some just about a year. They certainly would have been more useful if deployed earlier in 1942, but this would meant circumventing initial string reistance across the board, but from the merchant marine itself…

In the end, the “mechant aicraft carriers” are a very unique occurence of WW2, never seen before, and never repeated since. It was dictacted by very specific conditions and the idea remained a possibility in case of a war developing with the Soviet Union. Convoy escort training for the North Atlantic was practiced for years by NATO and the USN even rebooted the idea of escort carriers in the shape of the SCS class in 1969 and VSS class in 1974, but nothing came close to the conversion of a supertanker in the same manner. Although it could be the matter of wet dreams for some, with their post-oil crisis need to go round the cape horn, these 500,000 tonnes behemoths, 413m+ meters long could potentially be a bonanza of space for any air group, provided one hold section was sacrified and turned into a hangar… Large container ship also have amazing potential for conversion, albeit the level of technology and support required for an “aircraft carrier” today is probably out of reach realistically. However one-off simpler conversions had been studied. In the early 1980s experiments were conducted by both the USN and Royal Navy. In 2011 Maersk published a promotional explaining a kit could turn any of its latest container ships for a range of military applications, using modular conversion kits based on its containers – src.

Here are examples of service for these ships, note that these are relativly succint. More could be found there:

MV Empire MacAlpine

MV Empire MacAlpine

Empire McAlpine was originally laid down at Burntisland Shipbuilding Company of Fife in Scotland, ordered by the Ministry of War Transport, delivered on 14 April 1943. She was operated eventually by William Thomson & Co of the Ben Line. Nothing notable in her career but many convoys until the end of the war, and postwar, reconverted to a full capacity grain carrier, served until scrapped in Hong Kong in 1970.

MV Empire MacAndrew

MV Empire MacAndrew

MV Empire MacKendrick was built at William Denny and Brothers Dumbarton in Scotland and she was operated by The Hain Steamship Company Ltd in St Ives, Cornwall. Converted back to a grain carrier postwar and scrapped in Hong Kong in 1970.

MV Empire MacCallum

MV Empire MacCallum

MV Empire MacCallum was built at Lithgows shipyard, Glasgow in Scotland, for the Ministry of War Transport. She was operated by Hain Steam Ship Co Ltd of St Ives. On 7 July 1944, her Fairey Swordfish mistakenly sank Free French submarine “Perle” off the coast of Newfoundland. The sub was spotted prior by another wSwordfish from the Dutch MV Macoma. One of her “birds” was the Fairey Swordfish Mk II LS326 of ‘K’ flight previously on Rapana.It was preserved, restored in flying conditions and by November 2010, made her first new maiden flight for the Royal Navy Historic Flight. As for Empire McCallum she was reconverted as grain carrier in 1945, scrapped at Osaka in 1960.

MV Empire MacDermott

MV Empire MacDermott

MV Empire MacDermott was built by William Denny and Brothers, Dumbarton, Scotland.

She made a number of convoy escort missions on the Atlantic convoy routes, and postwar she was handed over to Buries Markes Ltd. of London in 1947, was rconverted and returned to merchant service in 1948 as “La Cumbre”. She was sold on again in 1959 to Canero Cia Nav. S. A., Panama as “Parnon” flying the Greek flag until 1969, sold her to Southern Shipping & Enterprises in Hong Kong as “Starlight”, Somalian flag. Then she was resold to China Ocean Shipping Co, in Peking by 1975 until 1991 officially stricken from Lloyd’s Register. Quite a career…

MV Empire MacKendrick

MV Empire MacKendrick

MV Empire MacKendrick was originally built at the Burntisland Shipbuilding Company Ltd, Fife, Scotland, for the Ministry of War Transport, completed on 12 December 1943. She was operated by William Thomson & Co (the Ben Line). She made a number of convoy escort missions without anything of note and in 1945 she was reconverted back to a grain carrier. In 1967, resold to a Bulgarian company, she was found trapped in the Suez Canal as the Six-Day War went on. She was scrapped at Split in 1975.

MV Empire MacRae

MV Empire MacRae

MV Empire MacRae was a grain ship built at Lithgows shipyard in Glasgow, Scotland, for the Ministry of War Transport. She was operated by Hain Steam Ship Co Ltd of St Ives. She made a number of convoy escort missions without anything of note and in 1945 she was reconverted back to a grain carrier, scrapped at Kaohsiung in 1971.

MV Empire MacCabe

MV Empire MacCabe

MV Empire MacCabe was built by Swan Hunter, Wallsend for the Ministry of War Transport, commissioned by December 1943, operated by the British Tanker Company. She made a number of convoy escort missions without anything of note and in 1946 she was reconverted back to an oil tanker, scrapped in Hong Kong in 1962.

MV Empire MacColl

MV Empire MacColl

MV Empire MacColl was built by Laird, Son & Co., Birkenhead for the Ministry of War Transport, commissioned by November 1943, operating for the British Tanker Company. She made a number of convoy escort missions without anything of note and in 1946 she was reconverted back to an oil tanker under the same name, and eventually scrapped in Faslane in 1962.

MV Empire MacKay

MV Empire MacKay

MV Empire MacKay was built by Harland and Wolff, Govan for the Ministry of War Transport and entered service in October 1943, with the British Tanker Company. She made a number of convoy escort missions without anything of note and in 1946 she was reconverted back to an oil tanker, renamed “British Swordfish” scrapped in Rotterdam in 1959.

MV Empire MacMahon

MV Empire MacMahon

MV Empire MacMahon was was built by Swan Hunter, Wallsend under order from the Ministry of War Transport and became a MAC ship in December 1943 under operation by the Anglo-Saxon Petroleum Co.

She made a number of convoy escort missions without anything of note and in 1946 she was reconverted back to an oil tanker, renamed Naninia, sold and scrapped in Hong Kong, 1960.

MV Acavus

MV Acavus

MV Acavus was originally built by Workman, Clark and Co. Belfast, launched on 24 November 1934, completed 1935. In 1942–1943, Acavus was converted by Silley Cox & Co. at Falmouth, recommissioned on October 1943. She carried 90% of oil capacity compared to pre-conversion, and crude oil to minimise fire hazard. She made a number of convoy escort missions without anything of note and in 1945 she was reconverted back to an oil tanker, later she was resold, renamed Iacra in 1963 but quickly scrapped in Italy.

MV Adula

MV Adula

MV Adula was built at Blytheswood, completed in March 1937 as oil tanker for the Royal Dutch/Shell line. She was converted at Falmouth, “commissioned” on February 1944, and after a number of convoy escorts she was reconverted to an oil tanker postwar, served until sold to Briton Ferry in May 1953 to be BU.

MV Alexia

MV Alexia

MV Alexia was built at Bremer Vulkan, completed in April, 1935 as oil tanker for the Anglo-Dutch Royal Dutch/Shell line. She was torpedoed but survived in two occasions during her early convoys, in two separate U-boat attacks in 1940 and 1942. She was converted to a MAC ship, and re-entering service in December 1943. Postwar, she was reconverted to an oil tanker, and resold, renamed “Ianthina” in 1951, sold for BU at Blyth in 1954.

MV Amastra

MV Amastra

MV Amastra was built at Lithgows Yard, completed in March, 1935 as oil tanker for the Royal Dutch/Shell line, converted at Smiths Dock, North Shields, in service by September 1943. After 1945 she was reconverted to an oil tanker, sold in 1951 as “Idas” until sold for BU at La Spezia in June 1955.

MV Ancylus

MV Ancylus

MV Ancylus was built at Swan Hunter, completed in January, 1935 as oil tanker for the Anglo Saxon Royal Dutch/Shell line, converted as MAC ship, in service by October, 1943. She operated Swordfish Mark II of ‘O’ Flight, 860 NAS. Ancylus was reconverted to an oil tanker after 1945, served as “Imbricaria” in 1952 until BU at La Spezia in December 1954.

MV Gadila

MV Gadila

Gadila was originally built at Howaldtswerke, Kiel, Germany, completed 11 April 1935 as an oil tanker for the Royal Dutch/Shell line. She was converted to Merchant Aircraft Carrier at Smith’s Dock Company Limited in Middlesbrough, between April 1943 and February 1944, commissioned on February 1, 1944. She operated Swordfish of ‘S’ Flight, 860 NAS. She made the following escort trips: ON-229 in March, 1944 and SC-157 in April 17-May 1, 1944, ON-236 in May 1944, HX-293 in May 27-June 9, 1944, ON-241 June, 1944, HX-299 July 11-July 24, 1944, ON-249 August 1944, HX-306 August 31-September 17, 1944, ON-263 in October, 1944, SC-161 November 17 – December 4, 1944, ON-273 in December, 1944, HX-333 by January 18 – February 1, 1945, ON-284 in February 1945, SC-169 March 7 – March 21, 1945, ON-295 in April, 1945, HX-353 in April 29 – May 15, 1945, ON 284 in February 10 – March 20, 1945 and SC 169 in February 10 – March 20, 1945. She served much longer than British MAC ships, until the very end of the Eureopean campaign, and decommissioned on May 30, 1945, converted back as tanker in Maatschappij Feijenoord, Schiedam, BU in Hong Kong from June, 1958.

MV Macoma

MV Macoma

MV Macoma was built at Nederlandse Scheepsbouw Mij, Amsterdam, and became one of nine Anglo Saxon Royal Dutch/Shell oil tankers, making her sea trials by May 13, 1936 and she served on the West Indies line until 1943, converted as Merchant Aircraft Carrier by Palmers Shipbuilding & Iron Company in Hebburon on Tyne, recommissioned on April 1, 1944. She operated Swordfish of ‘O’ (later ‘F’) Flight, 860 NAS. She made the following escort trips: ON-242 in June, 1944 and HX 300 by July 17 – August 3, 1944, ON-248 in August, 1944 and HX-305 by August 25 – September 10, 1944, ON-254 in September, 1944 and HX-312 by October 5 – October 21, 1944, ONS-35 in October 29 – November 15, 1944 and SC-161 in November 17 – December 4, 1944, ONS-38 by December 13, 1944 – January 2, 1945 and HX 331 in January 8 – January 22, 1945, ON 282 by February, 1945 and SC-168 in February 25 – March 13, 1945, ONS-47 by April 11 – 30, 1945 and SC-175 in May 7 – May 21, 1945. During one of her missions, her swordfish spitted a submarine surfaced off the convoy, communicated the info. The U-Boat was attacked by 860 squadron and a Swordfish from another MAC-ship. The suspected U-Boat was in reality the Free French submarine “La Perle” (one survivor).

She was decommissioned on May 30. 1945 and converted back to a tanker at Rotterdamsche Droogdok Maatschappij, Scrapped in Hong Kong by 1958.

MV Miralda

MV Miralda

She was launched in July 1936 at Nederlandse Scheepsbouw Mij, Amsterdam, conversion to a MAC ship, completed in January 1944. She was adopted by the British Ship Adoption Society (Maritime Charity) with schools amassing comforts for a particular ship, in return receiving thank letters and new from various ports. M.V Miralda was adopted by Styal Cottage Homes, a school for orphaned and destitute children of Manchester. Nothing of note during her career. After the war, she was reconverted and returned to merchant service under the same name, then resold as “Marisa” in 1950, served until scrapped in Hong Kong in 1960.

MV Rapana

MV Rapana

MV Rapana was built at Wilton-Fijenoord, Schiedam, Netherlands, launched in March 1935, completed by April and owned and operated by N.V. Petroleum Maats under the name “La Corona”. In 1939, she was purchased by the Anglo-Saxon Petroleum Company and continue service until 1943, converted as the first MAC tanker ship at Smith’s Dock Company. As Rapana she was completed in July 1943. She started convoy escorts in the North Atlantic from July 1943 and had aboard 836L Flight, 836 NAS by August. In October 1943 she was in convoy SC 143 when one of her Swordfish attacked a U-boat shadowing the convoy, but the latter survived. In April 1944, she had 836 X Flight aboard, under sent back to RNAS Maydown in October 1944 and she made the rest of her career without air group. After 1945, she was converted back as tanker and stayed with the Anglo Saxon Petroleum Company until 1950, resold as “La Corona” and then “Rotula” until January 1958, sold for BU at Osaka, Hanwa Kogyo K.K. One of her Swordfish, LS326, later transferred to MV Empire MacCallum is now part of RN Historic Flight, airworthy and displayed by the Fly Navy Heritage Trust.

Read More/Src

Books

Conway’s all the world’s fighting ships 1921-47

Lenaghan, J; R. Baker; W. J. Holt; A. J. Sims; A. W. Watson; Selected Papers on British Warship Design in World War II. Conway Maritime Press 1983

Hobbs, David (1996). Aircraft Carriers of the Royal and Commonwealth Navies. London: Greenhill Books.

Hobbs, David (2013). British Aircraft Carriers: Design, Development and Service Histories. Seaforth Publishing.

Sturtivant, R & Ballance, T (1994). ‘The Squadrons of the Fleet Air Arm’ Published by Air Britain Ltd, 1994

The World’s Warships 1941 by Francis E. McMurtrie (1944). Janes London 1941 1st ed.

Jane’s Fighting Ships of World War II by Francis E. McMurtrie (Editor) 1984. Crescent Books

Links

THE EFFECTIVENESS OF MERCHANT AIRCRAFT CARRIERS John R. Mably

web.archive.org fleetairarmarchive.net Empire_MacDermott

uboat.net

netherlandsnavy.nl Gadila class

The catafighters and merchant aircraft carriers Hardcover – January 1, 1970 by Kenneth Poolman

hazegray.org

navypedia.org mac_ships.htm

navywings.org.uk

mariners-l.co.uk EmpireM.html

web.archive.org/ fleetairarmarchive.net/ GADILA.htm

en.wikipedia.org Merchant_aircraft_carrier

en.wikipedia.org Empire_ship

Videos

Model Kits

Not a lot: HMS EMPIRE MACALPINE Escort Aircraft Carrier, AJM Models 1:700

ghqmodels.com/

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign