The world’s first “helicopter carrier”

The title, which is abusive given the hybrid nature of the Autogyro, predated the WW2 IJN Akitsu Maru, which also used autogyro and was in addition an amphibious assault ship in the modern sense. At least this was the first ship in Europe to deploy “VSTOL” (in 1934) in operations, although at an experimental level. Anyway, this was a pioneer, a first of three ships in the Armada, including the second of the name from 1967, ex-USS Cabot (Independence class), and from 1982 the Principe de Asturias, also based on a US design and in need of a replacement. But this had the Spanish Navy possessing naval air assets since 1918. The only interruption was between the Dédalo first of the name, being discarded in 1940, and the new one commissioned in 1967.

In truth, the original Dédalo made at the end of WWI Spain a pioneer in naval aviation, alongside Britain, but mostly operated balloons and classic seaplanes. The ship was a conversion from a civilian steamer, and instead of a full flight deck, she had the unique characteristic of being divided in two, operating ballons forward, with a hangar, and seaplanes aft, from a short landing deck. On this standpoint she was very singular, and is also forgotten in the great scheme of things today (but not in Spain through). For all her long interwar career she served semi-exparimentally rather than operationally, testing the waters of airborne naval reconnaissance for the fleet, albeit her slow speed was a deterrent for further integration. She never was a substitute for an aicraft carrier, an endeavour that Spain, in the very troubled interwar, was unable to pursue.

Spanish Naval Aviation

Before going into the details of Dédalo’s conversion and concept, let’s dive into the early beginnings of the Spanish Naval Aviation. Spain’s venture into the 3rd dimension of the sea started below it, with brillant engineers and pioneers, such as Monturiol, Saez and Peral (see the full picture of Spanish submarine development). For the air, an army service in 1896 used ht air balloons for observation, and in 1905 Spain had its first army dirigible. Heavier-than-air development started with the 1909 expedition of Colonel Pedro Vives Vich and Captain Alfredo Kindelán in Europe to adopt a first model, and later create a school. The Aeronáutica Española was first operationally tested over Morocco in 1913, with a unique expeditionary squadron making observation, strafing and bombing missions.

Hydro La Cierva, an autogyro seaplane

Still, the conservative Armada could not ignore experiments made by other navies at the time, but it’s only in 1915 that the first seaplane base was opened at Los Alcazares, Murcia. It was still under supervision of the army though. The Aeronáutica Naval was established through a Royal decree in 1916 in El Prat (todays Barcelona Airport). Since 1912 however, many of the future cadree already trained with the army air corps. The famous roundel was first ported by two Nieuport 80 and one Caudron G.3 in 1920. The Navy therefore looked at the prospect of carrying the numerous seaplanes it acquired, to screen for the fleet. It was also to bring support and coastal reconnaissance along the Morrocan coast during the Rif War.

Spanish licence-built Dornier Plus Ultra

The Navy at that time was equipped with Short models, from UK, but had no domestic production of seaplanes before the experimental (and confidential) HACR Cañete Pirata in 1927. The same year a licence was acquired by CASA (1923) to built the modern, all-metal Dornier Wal, which formed the bedrock of Spanish Naval Aviation both up and during the civil war.

In 1920, the Naval Aviation school was established in Barcelona Naval Aeronautics. This name “Aeronáutica Naval” change was made to accommodate both the aviation and ballooning specialties. The latter was considered rightfully obsolete and reduced in 1926, then eliminated in 1930. Lieutenant Commander Pedro Cardona Prieto was appointed first Director, in charge of selecting new seaplanes for his service.

Cañete Pirata

Of course the adoption of Dédalo changed the capabilities of this branch in 1922, a ship officially called “Estación Transportable de Aeronáutica Naval” or “Naval Aeronautics Transportable Station”, incorporated into the Navy in order to provide an utility Squadron able to transport and provide logistical support for seaplanes in operations. So she was essentally a depot ship with planes to carry the goods. The Spanish Navy still subordonated her use to the army, rather than providing an organic component to Navy Operations. For her, procurement was made of 3 Avro 504K, 4 Martinsyde F.4 Buzzard and 2 Parnall Panther. The diversity was also a way of comparing designs.

Development of the Spanish seaplane carrier

Design of the Dédalo

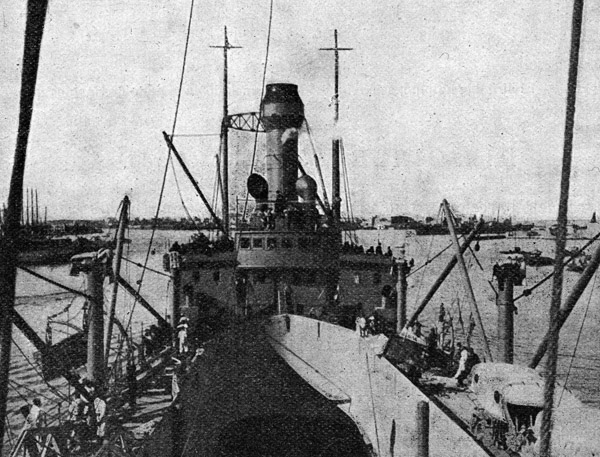

About the M/S Neuenfels

During WWI, and despite its neutral status, the Spanish Merchant Navy suffered human and material losses due to the urestricted campaign of German submarines in 1917. Pressured both by Spanish shipowners and public opinion, the Spanish government started negociations in August 1918 with German companies in order to obtain compensation for the tonnage lost. As it dragged on, in October 1918 several German ships present in Spanish ports were interned, which in all made it for the tonnage to the losses. This in Spain gave satisfaction to the shipowners, ended the pending arbitration however the disagreement with Germany remained unsolved until he Armistice.

among these vessels was the Neuenfels, one of recent six German steamers seized. This VTE-powered steamer was relatively modern, being laid down in 1900, launched in 1901 and commissined in 1902 to the Deutsche Dampfschifffahrts (DDG Hansa). She was given the provisional name ‘Espana No.6’ and provided immediate employment, now owned by the Ministry of Public Works. She was under the direction of a dedicated office called the «Gerencia de Buques Incautados por el Estado» (management of ship seized by the State) or “GBIE”.

This office took official possession of the vessel for inspection in the port of Vigo on October 23, 1918. The national flag was hosted, and crewmembers from the gunboat Hernán Cortés were mustered to care for the ship, waiting for a new new crew to be asembled, paid by the provided by an assigned new management Company, “Compañía Trasatlántica.”. After a brieg overhal in Ferrol, the vessel was registered in Vigo still apparently as “España Nº6”, and returned to full commercial activity, making nuerous trips in 1919.

In 1920, there was an outbreak onboard of bubonic plague. She had to spend the usual 40-days quarantine in the assigned sanitary control facility, in Mahón. Afterwards, she resume commercial service, making more trips until the end of September 1921. By then, it was decided to hand her over to the Spanish Navy. Indeed, the latter had plans to convert her as a first seaplane/balloon carrier.

Transfer to the Navy as Dédalo

The Spanish Naval Aeronautic Corps had long been interested to acquire or built a seaplane carrier, following the operational service in orther countries. After requesting to the state’s GBIE a transfer, it was agreed and signed by to the Ministry of the Navy and Public Works. España Nº6, was recommissioned as “Dédalo”, Daedalus, a logic choice. The transfer took officially place in November 1921.

Once delivered to the Naval Aeronautics School of Barcelona, the latter came with the conversion proposal. Conversion work started in mid-December 1921, and the study and blueprints were all drafted and conversion made until the start of preliminary tests, on May 1, 1922 over five months. These tests were carried out under the direction of Naval Engineers’s colonel Jacinto Vez, assisted by Lieutenant Commander Pedro María Cardona Prieto. From 1922 her first captain was Wenceslao Benítez Inglott.

Details of the conversion

The transformation into a seaplane carrier was carried out at Talleres Nuevo Vulcano, Barcelona, at a cost 8 million pesetas (1922) and it was quick. Unlike ther, more radical approaches, her superstructure wand masts were kept mostly unchanged. It consisted in modififying her forward part to be dedicated to observation balloons, with her former holds removed, the whole deck pierced and converted into a single hangar space. The goal was to be able to manage and inflate a balloon from the interior of the ship, safe from sea spray and wind, critical for balloon operations.

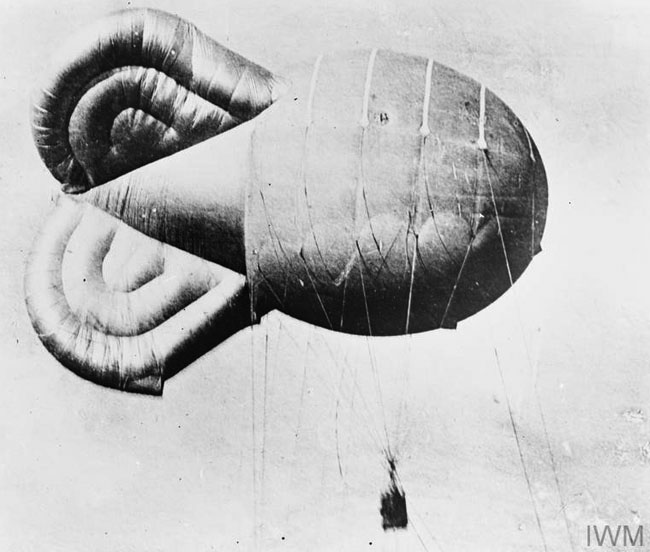

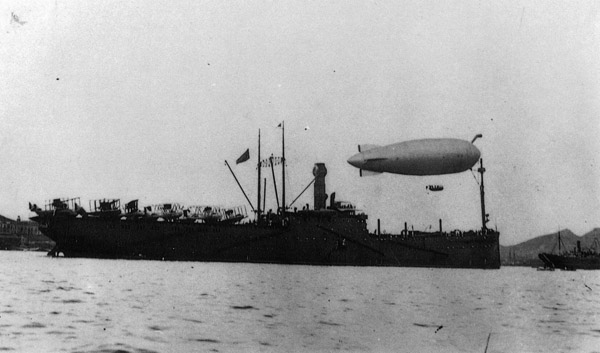

As such, she was able to carry two A.P. (Avorio Prassone) 1100 m³ captive balloons: They were raised from the mooring mast, using a telephone line. The latter was installed at the port bow with winched cable, but also with a similar holding system as used on foreign mooring masts for dirigibles. She also carried two Italian S.C.A. semi-rigid 1500 m³, 39.3 m independent balloons, one kept operational, and another in reserve.

Avorio-Passone Captive Balloon (1915): Volume 1130 cu.m, Diameter 11,46 m, Length 22,42 m, Max wind 20-25 m/sec.

The mooring post tailored for airships was partly lattice, and placed centerline to the bow. It allowed to navigate one balloon, moored to the post while another was prepared below into the open-air hangar. This way she could operate up to three balloons, one captive and two independent. The captive balloon The hangar also contained spare engines for the nacelles, equipments but moreover batteries for the hydrogen gas cylinders and a small workshop to ensure supply and proper maintenance of the balloons. When not in use, the hangar opening, shaped like a boat, was covered by a waterproof tarpaulin.

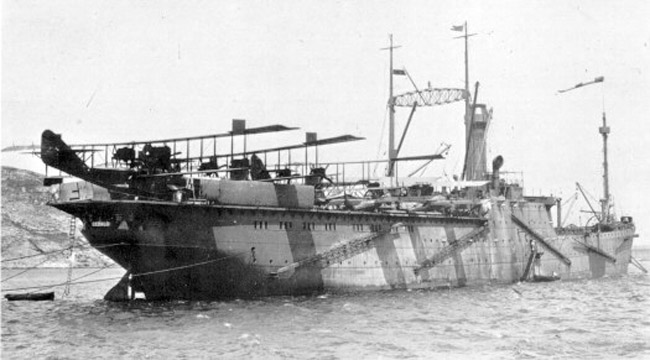

The aft part was dedicated to seaplanes. A holding deck was constructed above the original deck, replacing completely the former holding deck. She had a hangar to house the planes inside, although details are not known. This is very likely the two former holds were removed to make way for a larger open space. Part was managed as a workhop, with various payloads, ammunitions and fuel stores. She was still also a depot ship.

On this deck, which was neither “flying nor landing” any plane, but she could host up to twelve neatly stowed seaplanes on deck, and twenty with wings folded in the hangar inside. The 60 m deck had a dedicated lift to raise or lower the seaplanes in the hangar below, provided they had their wings removed due to its small size. This was a serious drawback for operational speed, but ensured to carry many models. The hangar indeed was not considered for preparing planes and rapid launch, but only as a reserve (see “operations”).

Indeed, in total, this made on paper 32 planes, provided they were all wings folded and of the smallest model (see air group), however most publications states an overall capacity for 25, deck and hangar combined. In this fashion, she was still one of largest capacity seaplane carrier in the world, as befitting to a “base”.

Armament & Other Caracteristics

Dédalo’s forward balloon hangar.

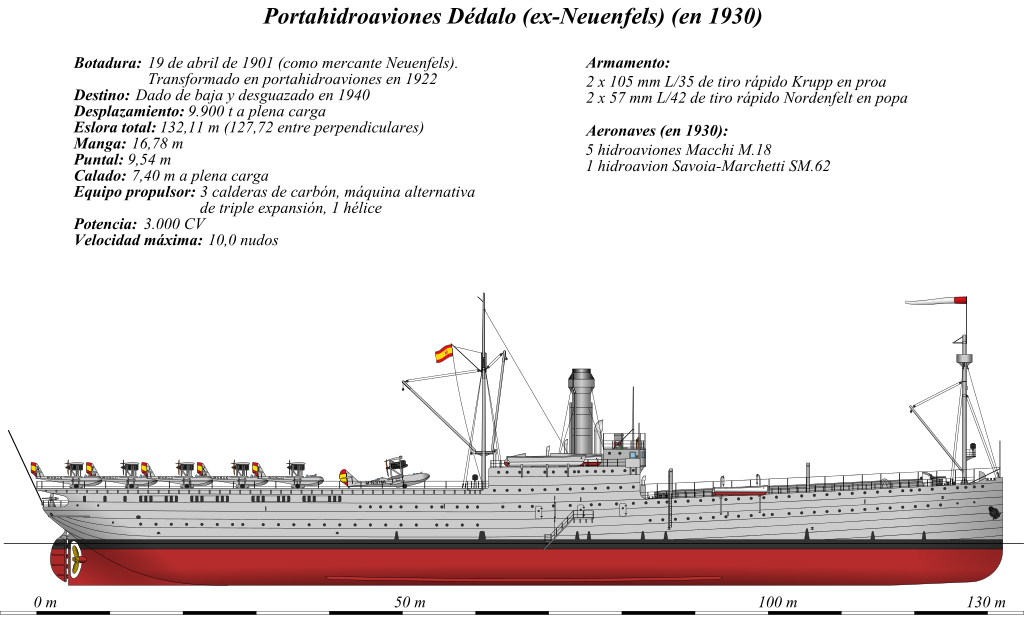

As she was commissioned in April 1901, Neufels’ displacement was around 8,500 GRT, but in Spanish service as Dédalo she displaced 9,000 tons standard, 9,900 t fully loaded. She measured 127,4 m long between PP and 132.11 m overall, for 16,76-16.78 m in width, and 7,4 m draft FL. (418 ft x 55 ft x 24 ft 3 in).

Her aft deck measured 60 m (). She was propelled by a single propeller shaft, mated to a 3-cylinder reciprocating engine, later changed to a more modern VTE, which developed 3,000 shp (2,200 kW), provided steam from three coal-burning boilers. Top speed was 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph). She carried a crew of 398 officers and sailors, probably comprising also her air group personal.

She also had two projectors, a pole mooring mast at the bow, a ladder-type, lattice mast with four booms to hoist seaplanes. As for close defence, she carried four Krupp 105 mm (4.1 in) guns and two 57 mm (2.2 in) AA guns.

Dédalo air group

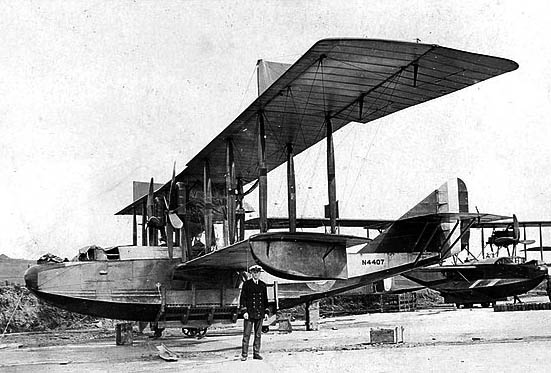

In reality, her Operational air group, as completed, was more diverse, and reduced: She carried four balloons (as seen above, two Avorio-Passone and two semi-rigid SCA types). The seaplanes were lowered into the water using cranes, and after splashing down and taxiing, were hoisted onboard by the same means. This air group comprised in all 22 seaplanes:

- Five Felixtowe F.3A obervation/bombers

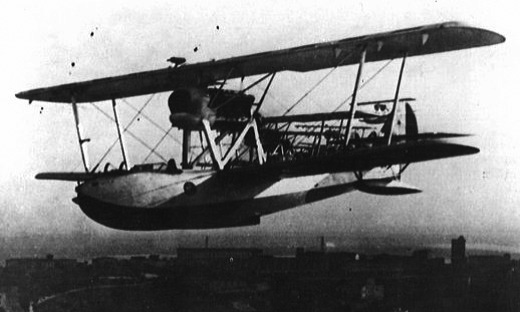

- Five Macchi M.18 Fighters

- Four SIAI S.13 Reconnaissance-fighters

- Four SIAI S.16 Reconnaissance-Transport-Bombers

- Five SIAI S.16bis Reconnaissance-Transports-Bombers

This made for a diverse group, filling all the needs of the Navy, with laison and transport models, long-range observation/bombardment models also possibly capable of ASW patrols, and escort fighters. The most capable were the high-performances Macchi M.18s, derived from the wartime Macchi M.5 which range was short and only intended as local defense and escort. Here are the details of each model:

Felixtowe F.3A (1917): Crew 4, 14.99 x 31.09 x 5.69 m, 7,958 lb/12,235 lb (5,550 kg). Prop: 2 × Rolls-Royce Eagle VIII V12 345 hp (257 kW), 91 mph (147 km/h, 79 kn), ceiling 8,000 ft (2,438 m). Armed with 4× Lewis guns, 920 lb (420 kg) bombs underwing

Macchi M.18 (1920): Crew pilot, observer, and gunner, 9.75 x 15.80 x 3.25 m, 1,275 kg/1,785 kg (3,935 lb). Prop. Isotta Fraschini Asso 250 186 kW (250 hp): 187 km/h (116 mph, 101 kn), range 1,000 km (621 mi, 540 nmi), ceiling 5,500 m (18,000 ft), armed with a 7.7 mm (.303 in) Vickers (ring), 4 light bombs underwing

SIAI S.13 (1918): Crew pilot, observer, propelled by an Isotta Fraschini V6 engine 187 kW (250 hp), top speed 197 km/h (122 mph, 106 kn), armed with a 7.7mm (0.303in) MG.

SIAI S.16/16 bis (1919): 9.89 x 15.50 x 3.67 m, 840/2,652 kg (5,847 lb), prop. Lorraine-Dietrich 12Db 298 kW (400 hp), 194 km/h (120 mph, 100 kn) range 1,000 km (621 mi, 540 nmi), ceiling 4,000 m (13,125 ft). Armed with a 7.7mm (0.303in) MG, 230kg (485lb) bombs underwing

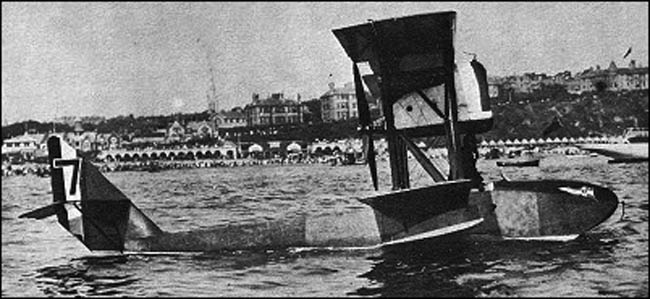

The air group was modified during the Rif War. As it progressed, the Navy needed a more modern, high performance and more versatile model. Discussion with Supermarine led to the purchase of a specifically designed variant of the Sea Eagle (1923). Not all 12 planes provided were on board the Dédalo. Some were kept in reserve and for training.

Supermarine Scarab (1924): Based on the 1923 Sea Eagle, and Sheldrake, in pusher configuration and tailored for the Spanish Navy and Dédalo: 12 built, delivered to the Spanish Naval Air Service as a bomber/reconnaissance model in Rif War. .303 in (7.7 mm) Lewis, 1,000 lb 454 kg. bombs underwing.

In the 1930s and the civil war (from 1932), she carried a modernized, much reduced air group, without balloons and with only five Macchi M.18 for reconnaissance/bombing and a single Savoia-Marchetti SM.62.

SM.62 (1926): Crew 3, 11 x 15.5 x 4.19 m, 1,900/3,000 kg (6,614 lb), prop. Isotta Fraschini Asso 500 V-12 370 kW (500 hp). Perf. 200 km/h (120 mph, 110 kn) ceiling 4,200 m (13,800 ft). Armed with 4 × 7.7 mm, 600 kg (1,300 lb) bombs.

Specifications 1922 |

|

| Dimensions | 176.63 oa (166.12 pp) x 16.45 x 5.03 m |

| Displacement | 7,475 long tons standard, 9,237 long tons Fully Loaded |

| Crew | 1044 total: 564 officers and enlisted men |

| Propulsion | 4 shafts parsons turbines, 8 WT Yarrow boilers 80,000 shp |

| Speed | 33 kn (61 km/h; 38 mph) 5,000 nmi |

| Armament | 8 × 6in (150), 4 × 4in (102), 2x 3pdr, 12x 21-in (533 mm) TTs |

| Armor | Belt: 40-75 mm, Decks: 25-50 mm, CT 150 mm |

Dédalo’s Morrocan Campaign

Dédalo during the Rif War, 1925

She started service at Cartagena in late 1922, under command of Wenceslao Benítez Inglott. A big chunk of the Naval Air Branch (1923-1924) was indeed linked to the Moroccan Campaign, or “Rif War”. From August 2 to November 15, 1922, Dédalo traveled to the coast of Africa to participate in the Morocco Campaign. Her main objective was to map and explore the coast, starting with Beni Urriaguel, and report troop movements of the Rifans, while cooperating with land-based army aircraft and seaplanes based in Mar Chica. Baptism of fire took place on August 6, 1922, with the bombardment of Morro Nuevo and Azibfazar.

The first loss, both of aircraft and pilots occured on June 20, 1923, when one Macchi M.18 crashed in “Los Acantilados del Freus” area, close to the Mola fortress, Menorca. A reported, it happened as a result of a stall while flying very low, resulting in the death of Lt. de Navío Mr. Vicente Cervera (pilot) Juan Suárez de Tangil (observer).

On October 2, 1924 two Spanish Supermarine Scarab seaplanes were shot down during a reconnaissance mission, of the coast of Gómara. They were flying in support of the Tiguisas positions to the point of being submerged by Rifans. One received bullet hits to her fuel tanks just as making a very low-level pass over enemy positions. She made a crash-landing about 500 meters from the coast. The other warned the nearby T-13 torpedo boat, but Rifan boats arrived in between to take their prize, the Spanish seaplane, still defended by pistol, by her crew. The T-13 arrived just in time to save both crew and plane, but the pilot, seriously injured, died in between.

Dédalo in 1930

The next year, Dédalo was sent to another offensive mission, the Alhucemas air-naval operation, taking place in support of a landing. This was for Spain its first complex combined-operation, amphibious and air-covered, with full coordination Army-Navy. It is today still a textbook reference for the modern Spanish Marines. The objective was to definitely “pacifying” the Spanish protectorate of Morocco. As planned on April 30, 1925, the goal was to create a base of operations (in addition to a beachhead) to allow landing and preparing an expeditionary corps of 20,000 men from Cebadilla beach to Adrar Sedun, with an operation area comprising the Morro Nuevo peninsula, Cabo del Quemado, Morro Viejo, Cala Bonita, Buyifar, Monte Palomas and Monte Malmust.

Dédalo and the rest of the naval air group had to spot and attack enemy positions in the initial phase of the landings, recoignise and report any reinforcement maneuver from the enemy, and later, bring air support by reconnaissance inland, boming and strafing enely targets of opportunity. On September 17, 1925, the naval air group bombed Sidi Dris and Cabo Quilates, even going so far as to strafe and bomb well dug-out positions and caves built by the rebels.

Dédalo in the interwar

Until 1925, she proved very valuable services to the Navy and Army during the war in Morocco. Her contribution to the Alhucemas landings notably has been praised and well observed. Her air group performed “projection power” missions with decisive result like her mass bombing on a Rifan Garrison during this support, dropping in all 175 bombs. This was the first landing with a massive air support in world history. In 1924, she sailed to Southampton to be loaded with a dozen Supermarine Scarab, tailor-built or Spain. These were the first Spanish Navy amphibious bombing seaplanes.

In October 1928, she participated in large fleet maneuvers. Later in the 1930s, the Spanish Navy, like the Air Service, were interested in Juan de la Cierva y Codorníu’s autogyro, which brought brand new capabilities with its vertical or short run take-off and landing. Soon, the Navy asked him to test his latest model on the deck of the Dédalo. De la Cierva made a perfect and precise landing on March 7, 1934, with his C.30, registered G-ACIO. A marked area, the world’s first “helispot” was painted on deck for the occasion. For this test, Dédalo was anchored off Valencia. 30 min. later, De la Cierva took off after a short run on 24 m. And again, made history again as the world’s first STO (Shot Taking Off) with a rotary-wing aicraft.

Cierva C.30

It can be argued the Autogyro was not a “true” helicopter, due to its conventional tail, front engine, and not able to fully hover or take off vertically, but it is generally assumed as the forebearer of more modern helicopters. This model enable brand new capabilities to the Dédalo and the Navy envisioned to acquire the C.30; Indeed, although its range, speed and payload were very limited, the capability to take off and landing quickly allowed the Navy to deployed a swarm of spotters all around the Ship, far quicker than earlier seaplanes.

The Cierva C.30 was widely tested around the world, exported and mostly used by the RAF as the Avro 671 Mk.1 (N.º80 and N.º529 Sqn), also licence-built in France as the Lioré et Olivier LeO C-30 or Germany as the Focked-Wulf C30 Heuschrecke. Having a single pilot onboard, the C.30 had a 6 m long fuselage, 11,28 m diameter rotor, was 3,38 m high, weight 554,5/818 kg fully loaded, and propelled by a 7-cyl radial Genet Major 1A which developed 108 kW 145 hp. It could reach 177 km/h, cruised at 153 km/h over 458 km. It was unarmed, although on the long run it could have been possible to fit forward a Vickers with interruptor gear.

Postcard

Operating a semi-rigid SCA, date unknown.

Dédalo in Cartagena, 1920. The photo could lead to think she was camouflaged, but this that the projected shadow of the planes stowed on board.

Civil War and Fate

With the troubled situation in Spain after the Rif War, as Support for the Rivera regime gradually faded. Miguel Primo de Rivera eventually resigned in January 1930. Little support for the monarchy in the major cities led eventually to the Republicans to grew support, and on 12 April 1931, the Republicans won the elections, proclaiming the Second Republic, King Alfonso XIII going into exile.

The spanish Navy was “purged” of its most conversative, pro-manarchist or pro-Rivera elements, and reorganized.

The Dédalo was mostly inactive all this time, with an air group largely dilapidated, and lack of maintenance or training. She was held in reserve, not making any fleet sorties and in 1933 it was decided to have her placed in reserve, with a skeleton crew. In 1935 the reserve was permanent, and she was srtipped of air air group (she had in 1930 also her forward balloon hangar scrapped).

Dédalo was decommissioned in April 1936. Dut due to the outbreak of the Civil War, she was partially reactivated in the port of Sagunto, waiting for a possible recommission by Repblican Forces. Eventually, she stayed there until the end of the war in 1939. Under the new Franco Regime, there were little prospect to have her recommissioned as many in the Armada seen the concept as already obsolete. She stayed in reserve again, until definitively stricken from the Navy Lists on March 1, 1940. After being towed to Valencia, she was scrapped. Her name would be given later to USS Cabot transferred in 1967.

Src/Read More

Books

Los Portaaviones Españoles: Camil Busquets, Albert Campanera y Juan Luis Coello, Vida Marítima

Chesneau, Roger, Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships 1906–1921.

Ministerio de Defensa (2017). Cien años de aviación naval 1917-2017

The first Dedalo was an aircraft transportation ship and the first in the world from which an autogyro took off and landed.

Busquets, C.; Campanera, A; Coello, J. L. (1994). Los portaaviones españoles. Agualarga Editores

Laforet Hernández, Juan José (2010). lmirantes Horiundos de Canarias: III Jornadas Marítimo-Navales. Las Palmas de Gran Canaria: Real Sociedad Económica de Amigos del País de Gran Canaria. p. 74

Links

El dédalo aviacionnaval (sp)

Spanish Naval Aviation on ww2aircraft.net

Early Appearance (model kit)

On publicaciones.defensa.gob.es

On bibliotecavirtual.defensa.gob.es

On abc.es/archivo

On abc.es/archivo

On abc.es/archivo

Armada’s aviation (wiki es)

Dédalo (wiki es)

Model Kits

Only known model kit: Fairy Kikaku Models Spanish Seaplane Carrier Dedalo, Spanish Civil War S048 1:700.

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign