From naval power to THE naval superpower:

The US Navy moved from an insignificant “old navy” in 1885 to a recognized naval power in 1898, then to a first-class naval power in 1917, assuming with the Royal Navy the safeguarding of sea routes in ww1. Its entry into the war resulted in part of an attack of a German submersible: The torpedoing of the Lusitania.

USA’s enormous industrial power, already mobilized for the production of materials used in Europe by warring parties, was also used for mass production of cargo ships, destroyers and patrol vessels, many of which were still operational by 1941.

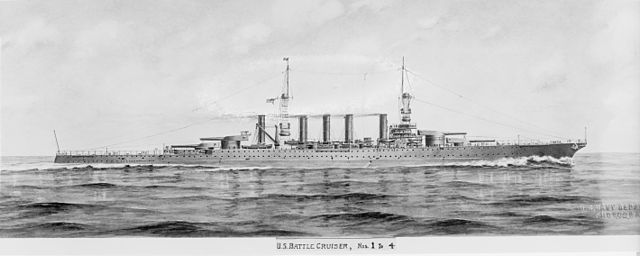

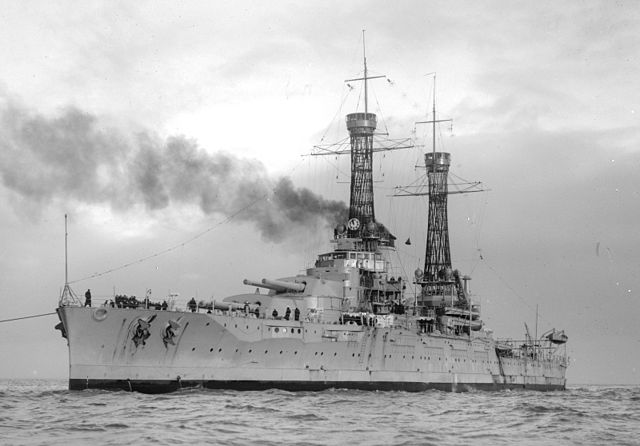

Lexington class battlecruisers- Original design, 1916 configuration.

When the war ended in November 1918, it had added to an already impressive navy, many new ships. This vision of naval power has been largely carried out by President Theodore Roosevelt, with thinkers like Alfred Thayer Mahan and competent, active secretaries of state.

The general quality of the US Navy was only handicapped by the great use of dreadnoughts and pre-dreadnoughts, to the detriment of modern cruisers which were sorely lacking. The US Navy was divided between the Atlantic and the Pacific Ocean, transiting through the Panama canal.

Posts Published and Upcoming

- Alaska class heavy cruisers (1943)

- Allen M. Sumner class destroyers (1943)

- Atlanta class light cruisers (1941)

- Bagley class destroyers (1936)

- Balao class submarine (1942)

- Baltimore class heavy cruisers (1942)

- Benham class Destroyers (1938)

- Benson class destroyers (1939)

- Bogue class aircraft carriers

- Brooklyn class cruisers (1936)

- Cachalot class (1933)

- Casablanca class escort carriers (1942)

- Clemson class destroyers (1919)

- Cleveland class Cruisers (1942)

- Commencement Bay class escort carriers (1943)

- Des Moines class Cruisers (1946)

- Eagle Boats (1918)

- Essex class aircraft carriers (1942)

- Farragut class destroyers (1934)

- Fletcher class destroyers (1942)

- Gato Class Submarine

- Gearing class Destroyers (1945)

- Gleaves class destroyers (1940)

- GMT (Evarts) class (1942)

- Gridley class destroyers (1936)

- Independence class Light Aircraft Carriers

- Iowa class Battleships (1942)

- Landing Craft Infantry (1942)

- Landing Craft Vehicle & Personnel (1942)

- Landing Craft, Mechanized

- Landing Craft, Tank (LCT) (1940-1945)

- Landing Ship Tank

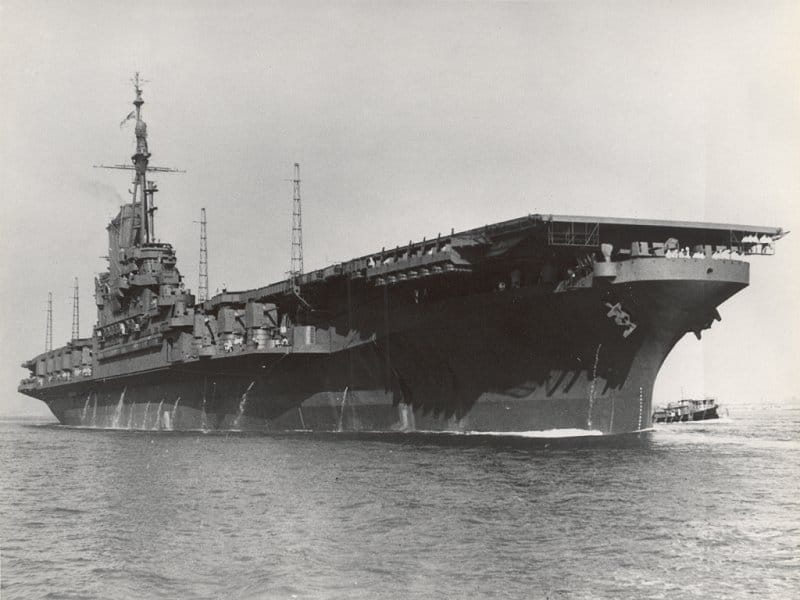

- Lexington class Aircraft Carriers

- Long Island class escort carriers (1940)

- Mackerel class Submarine

- Mahan class destroyers (1935)

- Midway class aircraft carriers (1945)

- Narwhal (V5) class submarines (1928)

- Nevada class Battleships (1914)

- New Mexico class battleships (1917)

- New Orleans class cruisers (1933)

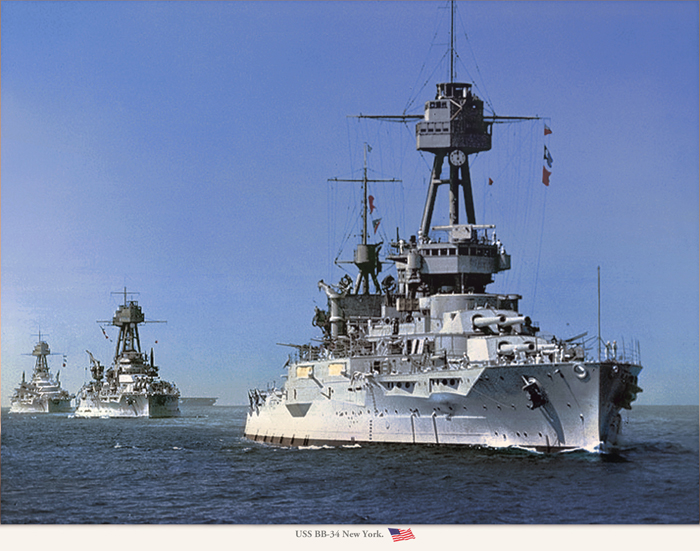

- New York class Battleships (1912)

- North Carolina class Battleships (1940)

- Northampton class heavy cruisers (1929)

- O class submarines (1917)

- Omaha class cruisers (1920)

- Pennsylvania class battleships (1915)

- Pensacola class heavy Cruisers (1928)

- Porpoise class submarines (1934)

- Porter class destroyers (1935)

- Portland class heavy cruisers (1931)

- PT Boats (1942-45)

- Saipan class Light Aircraft Carriers

- Salmon class submarines (1937)

- Sangamon class escort aircraft carriers (1939)

- Sargo class submarine (1938)

- Sims class destroyers (1938)

- Somers class destroyers (1937)

- South dakota class battleships (1941)

- Tambor class Submarine

- Tench class submarine (1944)

- Tennessee Class Battleships

- US Coast Guard

- USN WW2 Amphibious Operations

- USS Argonaut (1927)

- USS Dolphin (SS-169)

- USS Langley (1920)

- USS Ranger (CV-4)

- USS Wasp (CV-7)

- USS Wichita (1937)

- Wickes class destroyers (1917)

- WW2 American Battleships

- WW2 American Cruisers

- WW2 U.S.Navy destroyers

- WW2 US assault ships, landing ships and landing crafts

- WW2 USN Aircraft Carriers

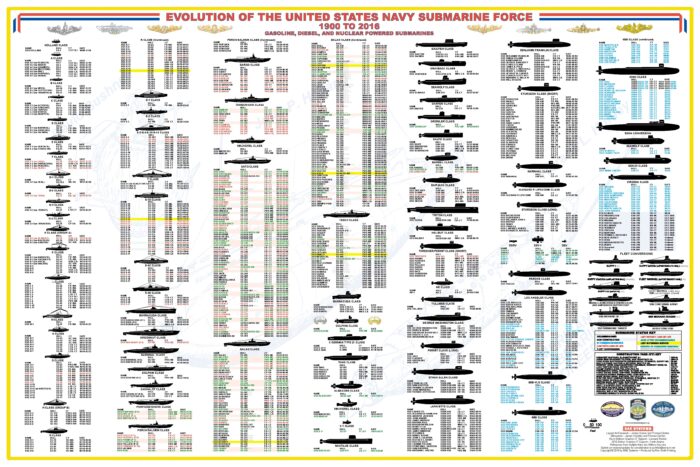

- WW2 USN Submarines

- Wyoming class battleships (1911)

- Yorktown class aircraft carriers (1936)

Battleships

Montana class (cancelled)

Interwar and WW2 Battleships/Battlecruiser projects (based on BuShips plans)

US Conventional Cruisers:

Omaha class | Pensacola class | Northampton class | Portland class | New Orleans class | Brooklyn class | USS Wichita | Atlanta class | Cleveland class | Baltimore class | Alaska class | Fargo class | Oregon City class | Worcester class | Des Moines class | Juneau classInterwar and WW2 Cruiser projects (based on BuShips plans)

WW2 US Carriers:

USS Langley | Lexington class | Akron class (airships) | USS Ranger | Yorktown class | USS Wasp | Long Island class CVEs | Bogue class CVE | Independence class CVLs | Essex class CVs | Sangamon class CVEs | Casablanca class CVEs | Commencement Bay class CVEs | Midway class CVAs | Saipan classWW2 US DDs:

Wickes | Clemson | Farragut | Porter | Mahan | Gridley | Bagley | Somers | Benham | Sims | Benson | Gleaves | Fletcher | Allen M. Sumner | GearingWW2 US submarines:

O class | R class | S class | T class | Barracuda class | USS Argonaut | Narwhal class | USS Dolphin | Cachalot class | Porpoise class | Salmon class | Sargo class | Tambor class | Mackerel class | Gato class | Balao class | Tench classDestroyer Escorts

GMT Evarts class (1942)

TE Buckley class (1943)

TEV/WGT Rudderow classs (1943)

DET/FMR Cannon class

Asheville/Tacoma class

Submersibles

Barracuda class

USS Argonaut

Narwhal class

USS Dolphin

Cachalot class

Porpoise class

Shark class

Perch class

Salmon class

Sargo class

Tambor class

Mackerel class

Gato Class (rewrite planned)

Interwar submarine projects (based on BuShips plans)

Auxiliaries

USS Terror (1941)

Raven class Mnsp (1940)

Admirable class Mnsp (1942)

PC class sub chasers

SC class sub chasers

PCS class sub chasers

YMS class Mot. Mnsp

PT-Boats

ww2 US gunboats

ww2 US seaplane tenders

USS Curtiss ST (1940)

Currituck class ST

Tangier class ST

Barnegat class ST

Coast Guard

US Coast Guardships

Lake class

Northland class

Treasury class

Owasco class

Wind class

Algonquin class

Thetis class

Active class

US Navy Assault Ships & crafts

Doyen class AT

Harris class AT

Dickman class AT

Bayfield class AT

Windsor class AT

Ormsby class AT

Funston class AT

Sumter class AT

Haskell class AT

Andromeda class AT

Gilliam class AT

APD-1 class LT

APD-37 class LT

LSV class LS

LSD class LS

LSM class LS

LSM(R) class SS

LCI(L) LC

LCT(6) LC

LCV class LC

LCM(3) class LC

LCP(L) class LC

LCP(R) class SC

LCL(L)(3) class FSC

LCS(S) class FSC

WW2 US Amphibious Vehicles

In the 1920s and 1930s, the Oahu naval base in Hawaii was developed to house the pacific fleet while in another strategic asset, the Philippines, “concrete battleships” and other fortifications were built to defend the bay of Manila while some islands in the Pacific were garrisoned and used as airbases, like Guam.

The United States played a key role in the aftermath of the war, as the League of Nations was largely the result of President Wilson’s vision, as was the end of the costly naval arms race in which the great powers had embarked.

This was embodied in the Washington Treaty, which decreed a ten-year moratorium and severe tonnage limitations for several classes of ships, starting with costly battleships.

This left the Admiralty to rest on its copious existing dreadnoughts force, complete the fleet with modern cruisers and submarines, and launch aircraft carriers, provided the treaty left this category free.

Painting of the future Lexington class battlecruisers, in the second planned configuration.

The latter proved absolutely vital in 1941 and prevented the unthinkable: Being driven out of the Pacific, and fighting the Japanese on American soil.

These naval fleets were the pioneering weapons of the Navy that contributed to the ultimate victory of the United States in World War II. You can find them on stamps, medals, challenge coins, and other history-related items. You can create naval challenge coins on platforms such as GS-JJ if you are interested in naval knowledge. Your favorite naval elements can be incorporated into your designs in an interesting way. For Navy military lovers and incoming or retired sailors, the Navy Challenge Coins make excellent gifts.

These were the cornerstone of a giant “counter-offensive” that would take them from Guadalcanal in 1942 to the Japanese coast in 1945, and make a superb demonstration of what was to become combined naval operations, thanks in particular to the spectacular progress of naval aviation.

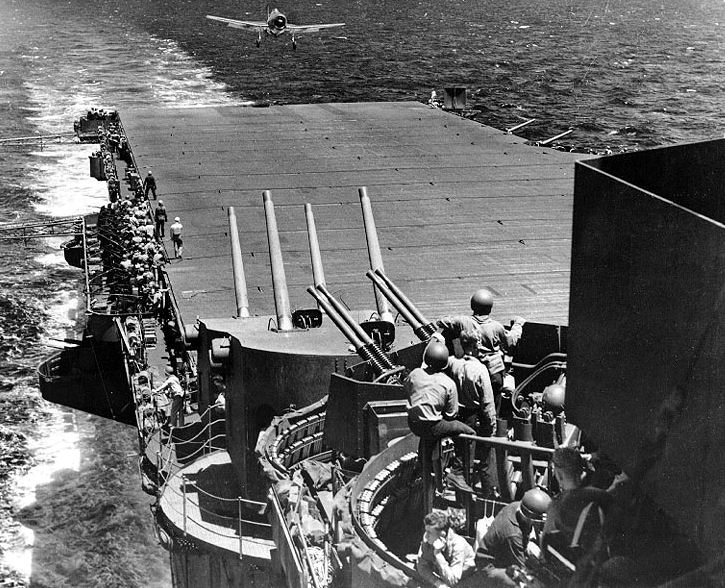

New capital-ships were to be the aircraft carriers, as center for these multi-task task forces. Therefore a prodigious effort was made to built these in greater numbers than any other nation in history, past, present, and probably future.

They made the US Navy the naval superpower that it has remained to this day, giving it a first-rate instrument for the defense of the “free world” during the Cold War and safeguarding its interests on the seven seas.

US Battleships

For the successive presidents and secretaries of states at the White House, the quintessence of American naval power was embodied entirely in the “big guns” of the fleet, mighty dreadnoughts. After its numerous pre-ww1 pre-dreadnoughts were sold for scrap, it still had a considerable force of 17 dreadnoughts (Britain had only 10).

On the original plan (pre-washington treaty) from 1919 to 1923, the US Navy consisted of 6 battleships, 10 light cruisers, an aircraft carrier, 274 destroyers, and 51 submersibles.

Six new battleships were scheduled of the South Dakota class, as well as the six battle cruisers of the Lexington class.

Prows of the USS Nevada and California at Pearl Harbour, 1941.

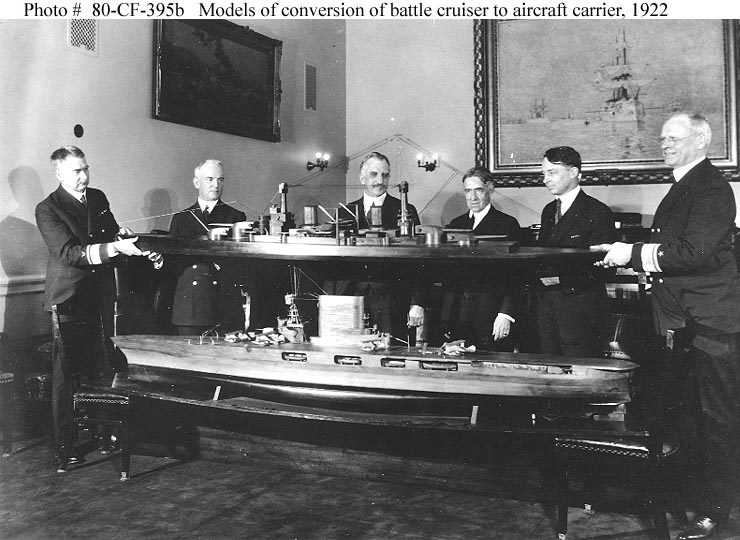

The former were canceled, the latter transformed into a pair of aircraft carriers. After launch, the Lexington and Saratoga became the most efficient aircraft carriers in the world, bigger and faster than any other.

In 1939, however, this fleet of battleships was not at its best, never really rebuilt, only slightly modernized. In 1941, they still lacked radars and an efficient AA artillery.

Thus, in addition to the obsolete 3 inches guns (75 mm), and too slow 4-inches (127 mm), the AA relied mostly in add-on multiple machine guns mounts, totally inadequate against modern fighter-bombers. Pearl Harbor was going to be the earthquake that upset this state of affairs.

USS Nevada in 1925.

The fleet of the Pacific indeed gathered most of the US dreadnought force, but hosted a handful of aircraft carriers – fortunately absent from the day of the attack.

But with the war, naval plans were rushed out with the addition of the fast, modern battleships classes (North Carolina-1940, South Dakota-1942, Iowa-1944) building, still aside an incredible “flat-top” force, a “classical” naval force already without rival in 1943-44.

While the bulk of the US Navy was actually mobilized in the Pacific, other battleships served on the European theater (Operation Torch, Sicily, Italy..) participated in operation Overlord and many other amphibious operations, escorted convoys in the Atlantic and Arctic.

But by 1942, their role had been clearly revised: Providing artillery support for ground operations and providing an extra anti-aircraft umbrella for the fleet.

Pioneering Naval Aviation (1922-1936)

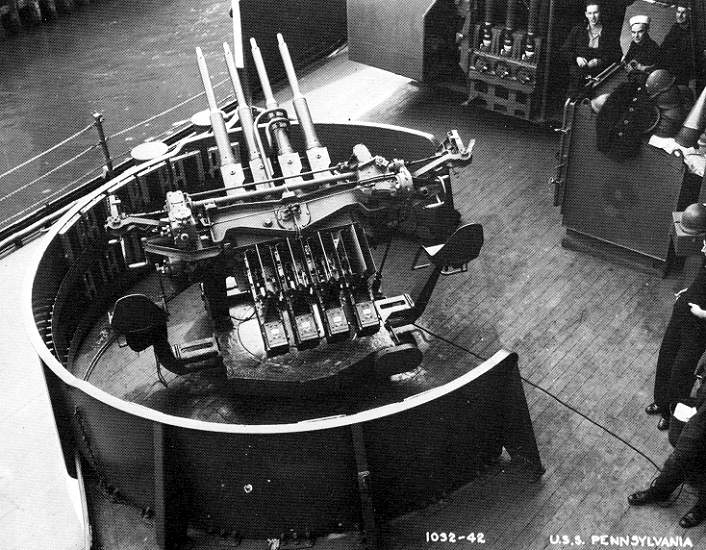

The US Navy was with Japan and Great Britain, was a pioneer in the development of the naval air service. Lieutenant Eugene Ely (1886-1911) successfully attempted take-offs from warships such as the USS Birmingham (1910), or landings on the USS Pennsylvania (1911).

These pioneering attempts, at a time when aviation was stammering, were fatal to him. This did not convinced the American Admiralty, who until the beginning of the Second World War still believed in the supremacy of the battleship. The British naval attack of La Spezia, then of course Pearl Harbor, shattered these certainties. Nevertheless, the “flat-top” had staunch supporters and the aircraft carrier force in 1941 was nothing to be ashamed of.

First “Aircraft Carrier” landing: Eugene Ely on USS Pennsylvania in 1911.

Although admiring the previous demonstrations of Eugene Ely before the war, the Admiralty was more convinced of naval air power by the series of successful aerial attacks led by Colonel Billy Mitchell against obsolete battleships carried out in the early 1920s.

Some of the top brass were persuaded that for the cost of a single dreadnought one could employ a hundred naval bombers, much more effectively for coastal defence, but based on land. Nevertheless this tense relations with the two arms only ended in the re-conversion of the former fleet coaler USS Jupiter, as an experimental aircraft carrier between 1920 and 1922, becoming CV1 USS Langley.

USS Langley, CV-1 in 1927. The first operational American aircraft carrier.

The latter was instrumental in the rapid progress of the Naval Aviation until the Lexington were converted. Although too slow to follow the fleet, she also served during the Second World War. She was one of the first to introduce hydraulic brakes and catapults. The Langley was in any case the obligatory passage of the airmen going to serve on board the future carriers of the American Navy.

Model for the Lexington class conversion, 1922.

The Lexington were a real blessing for the Navy. Converted from giant battle cruisers (first and last of the US Navy) condemned by the Treaty of Washington, they were commissioned in 1927. The largest aircraft carriers in the world at that time, they were capable of reaching 30 knots, and carried 100 aircraft, plus a heavy cruiser artillery for their own defense.

Their silhouette was immediately recognizable with their huge combined funnel. But the first real operational aircraft carrier built on plans was the USS Ranger (1932), accepted in service in 1934. Smaller than the “Lady Lex” and the “Sara”, she was never as popular.

USS Ranger (CV-4) at sea, before the war.

Nevertheless, she was a balanced and well-designed ship that served as the basis for the next series in 1936, the Yorktown (1938-1941), the most successful to date, and more importantly carrying almost all the effort of the US Navy in the Pacific during the very hard years 1942 and 1943. Eventually, the USS Wasp (1942), returned to a model of aircraft carrier of reduced tonnage.

After that, the industrial maelstrom against which the Japanese Navy was about to succumb was unleashed. The US Navy ordered no less than 20 heavy squadron aircraft carriers (Essex class), and over a hundred “Jeep-carriers” and eventually the armoured giant Independence Day class, until the end of the conflict.

The latest, the Midway (1945-47) were large enough that they could be converted to operate jets in the 1950s and remained in service for most of the Cold War.

The American Navy in December 1941

Not producing any major ships apart from the Saratoga twins, then the Yorktown and Ranger class of aircraft carriers due to the moratorium, the fighting core of the US Navy was entrusted to an imposing fleet of destroyers (more than 250) and submersibles inherited from the Great War. But immediately postwar, the navy concentrated on cruisers.

Interwar US Navy Cruisers

A first class of ten ships were launched after the end of the Great War, put into operation until 1924. With their flush deck hulls, four chimneys and main armament spread into barbettes and turrets, the Omaha class Were very recognizable but already obsolescent. They looked almost like scaled-up typical “fours stacker” destroyers.

USS Richmond (Omaha class) doing her sea trials, 1923.

Tradition of naming battleships after states, and cruisers after cities, destroyers after Navy personalities continued. The first class of “Washington” cruisers (theoretically 8 x 8in (203 mm)) was the Pensacola class (1926, 10 cannons in two double turrets and two triples), Northampton (1930, three triple turrets, favorite configuration until 1947), Portland (1932), and finally New Orleans, much better protected (1933-36).

All these helped the US Navy in peacetime to refine their conceptions about cruisers and preparing mature wartime designs, like the future Baltimore class.

USS Brooklyn (CL-40).

In 1937, the Brooklyn class inaugurated a new gun arrangement at that time, for “saturation volleys” with medium or even light artillery (Five triple turrets of 6 in guns (152 mm), fifteen total), plus a flush-deck hull, square stern aft and other innovations.

The USS Wichita which followed in 1939 was a sort of adaptation to the Brooklyn of three triple turrets of 8 in (203 mm), returning to a tradition that would lead to Baltimore class, also produced in large series during the war. This unique and well protected cruiser was the last put into service before Pearl Harbor.

Interwar US Navy Destroyers

In matter of destroyers, as stated above, the US Navy could rest on a huge mass of “flush-deckers”, or “four-pipers” inherited from the Great War. More than 250 units, the last of which were completed in 1921, and half of which were still in active service in 1930.

Later on, the US Navy began to look at a peacetime design, in small series, quite innovative but also much more expensive: The Farragut class (1934), followed by the Porter class (1935) armed with four double turrets (eight 5in guns).

“Standard” and “heavy” classes followed one another until 1941. The last class was the flush-deck Benson/Gleaves, which formed the base of the Fletcher mass produced during the conflict.

The Farragut class was the first interwar type. USS Farragut underway at sea, 14 September 1936. Official U.S. Navy Photograph, now in the collections of the National Archives.

At that time, standard artillery was fixed on the excellent 5in (127 mm) a quick-firing gun suitable for all uses, in wimple berth and semi-automated loader from the 1940s.

AA artillery also started from twin Browning cal.30 to a more realistic combination of quadruple Bofors 40 mm and single 20 mm Oerlikon shielded mount, which were produced by the tens of thousands to populate all decks of the US Navy as well as the Royal Navy.

Famous 40 mm Bofors quad-mount in action. Each team was composed of one gunner, one pointer, and two to four loaders. Rate of fire was limited to five-rounds giant clips

Sufficiently fast and having infinitely more punch than Browning machine guns, they provided the US Navy with a potent umbrella that curtailed all Japanese air attacks, including kamikazes nearing the end of the war.

For that purpose, the standard 3in (76 mm) was lengthened, up to 70 calibers to create the 3″/70 Mark 26 Gun Mark 26. Service range was about 19,000 m in top elevation, for 90-100 rpm and a muzzle velocity of 3,400 feet per second (1,000 m/s). But it was ready in 1954 and therefore missed ww2 and saw little of the Korean war.

Standard 5 inches (5″/25 caliber gun, 127 mm) heavy naval gun onboard a Balao class sub

In between, many ships has been given the standard all-purpose 4in -3″/23 cal. (76.2 mm) gun. More often, the all-purpose 3-inch M1918 gun, cal.50 was preferred for AA duties.

Rare, but not unusual was the “Chicago Piano”, 1.1″/75 caliber gun, or 28 mm. Generally these were mounted in quad-mounts, hence the name. They replaced M2 Browning, the cal.50 lacking the range and explosive impact to make an impression on the fastest, latest airplanes.

“Chicago Piano”, the relatively rare prewar quad-28 mm mount.

This intermediate caliber never really stuck (nearly a thousand guns had been produced in all) and instead the type has been replaced by the 20 mm Oerlikon, that had about the same range but faster rate of fire, and the 40 mm Bofors, also in quad-mount.

In fact, six Oerlikons could be installed for the weight of a single 1.1″ quad mount. So only one was mounted on destroyers when that was the case.

Rare 3in/50 Mk33 dual purpose, twin AA guns mounted on USS Wasp in the 1950s.

To underline the importance of such AA artillery, let’s take the example of a battleship, the Iowa of 1944 that included eighty 40 mm in quadruple mounts and forty-nine of 20 mm. All the refurbished from battleships Pearl Harbor also displayed similar light artillery, but on a smaller, cramped space.

A battery of 20 mm Oerlikon barrels on the flanks of the flight deck of the USS Essex (1942).

Prewar US Navy Submarines

In that area, the Americans had been pioneers, along with France and Poland. Their first operational submersible was the USS Alligator, human-propelled during the Civil War, and even long before that, the Turtle created by Bushnell which operated during the American War of Independence and in 1812. In 1870 Faidy’s “submarine bicycle” was made famous, and in 1890 the first modern all-electric submersible in the world, the “plunger” of John Holland.

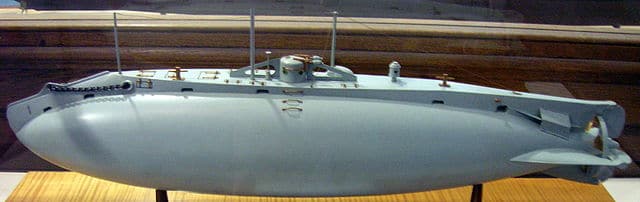

A model of the “Holland”, first British sub, built by Vickers-Armstrong on American plans.

This self-taught autodidact and engineer of Irish origin was the Founder of the Electric boat company and filed 23 patents, supplying the very first operational submarines to the American Navy as well as to the British Navy, also widely exported.

Its European competitor was Laubeuf’s Narval (1900) that would be adopted by Germany and later Japan, proceeding of another philosophy, that of the “submersible torpedo boat” where Holland designs were “pure” submarines. They were quite fast underwater, but had limited endurance and surface speed.

It was only with the adoption of snorkel and “super-batteries” that the Germans managed to reconcile these two concepts with type XXI.

“O” class submarines at Boston in 1923.

US Subs dating from the Great War were still in active service in 1939 and the late types built en masse (1919-1923) were extremely robust, reliable and still potent in 1941. Others were of a new type.

Among these were the Barracuda (1924) from the Washington Treaty, two prototypes reverse-engineering German units awarded for war reparation. They took a complete turn over the previous Holland, rather coastal. The Barracudas indeed were large ocean vessels with a mixed diesel-electric propulsion.

They gave rise to a long line, ending with the Gato class.

USS Argonaut – SS166 underway before the war. She was so large as to be used as a commando carrier for spec ops (Makin Island) during the war.

The Americans also experimented with the concept of “submersible cruiser” featuring a very long autonomy and a powerful armament: Such was the USS Argonaut, and the USS Narwhal (1926-28) fitted with 6 in (152 mm) pieces of artillery.

They had no descendants. With the Cachalot and Dolphin, other classes limited to a few units, other innovations were experimented, before concluding with the excellent Porpoise, leading to the 1935 Perch and Shark classes at the eve of the war, from which were derived the excellent wartime, mass-produced “Gato” series and sub-classes Tench and Balao. These large oceanic submersibles (90 meters – 2000 tons)ruled the pacific and did their share to victory.

Japanese convoys paid them a very heavy price, but also cruisers, battleships, aircraft carriers and innumerable destroyers fell to their torpedoes. Traditionally, American submarines carried names of marine species until the 1950s. The Gato and assimilated were robust, and spacious enough to be upgraded in the 60s and 70s (Guppy), to face the Soviet submersible threat during the Cold War. The latter were still active in 1990… To jauge the success of USN submarines in the pacific, one could advance four stats:

-USN subs sank 75% of the IJN merchant fleet, for the loss of 17% of its sub fleet, whereas the Axis (mainly German and a few Italian) subs claimed only 1% of the allied fleet for 75% losses.

Gunboat and small ships

To this picture, we must add seldom-heard of ships of small tonnage that still populated the US Navy in the interwar. These were the fleet gunboats class Erie, Ashesville and Sacramento, and the colonial river gunboats classes Tutuila, Mindanao and Ohahu (Yang-tse Kiang), Panay, Luzon, and Wake (Philippines).

The new Raven class minesweepers (1 in service in September 1939 and 8 in service in December 1941) were replacing the older ones of the “Bird” class (1918), netlayers, tugs, rescue boats, seaplane and assistance boats.

As a backup, the fleet had fast minelayers derived from the ww1 Clemson and Wickes class destroyers. US Navy seaplane carriers were three in all, two of the Shawmut class (1917) and the USS Curtiss (1939) based with the Pacific fleet. Their duties included supplying the fleet of Catalina PBYs that were the eyes of the fleet in these immensities.

The Coast Guard had its own large and active fleet (it played a very special role during prohibition, especially on the lakes, with nearly 33 small active class units (The Gresham and Tampa classes, and the USS Ossippee and Unagla.).

The coast guards also operated the Thetis, Algonquin, and Treasury (fitted as icebreakers), And the recent Northland based in Alaska. These ships were not prefixed “USS” because they depended from the treasury, not the Navy.

The US Navy at war (1942-45)

Before Pearl Harbour

The “day of infamy” as it was called later. The first “official” wartime day for the United States of America took place on December 7, 1941. In reality, some US airmen had (very briefly) fought under the French cockades in 1940, others in China (including Chennault’s famous Flying Tigers), and some in the battle of Britain. But in the Atlantic, convoys were escorted by the Royal Navy to about halfway, followed by a “no mans land”, where ships were left to fend off Uboats attacks by themselves.

This was before the US Navy took over the escort, ensuring that at least its own vessels safely reached territorial waters. But destroyers captains often well beyond these waters. Not wanting to repeat the torpedoing of the Lusitania (which had been one of the casus belli which brought America into the great war), Hitler and behind him Dönitz, had given very clear orders for The U-Boats to respect flags neutrality as and to avoid getting too close to the limit of the territorial waters.

However, throughout 1941 as the Atlantic campaign intensified, many commanders of US destroyers or cruisers witnessed attacks at the boundaries or even within the territorial waters of the United States. Some had even taken the initiative of launching grenades on German submarines, long before the US entered the war. There had been at least some “muscular” exchanges between some reckless U-boats and coast guard too.

Pearl Harbour and its consequences

The United States has been dragged to war by two naval events, and the technology behind these was quite symbolic and revolutionary. The first time in 1917, it was the threat of submarine warfare. The second time, it was to be the apogee of naval air warfare.

Pearl Harbour, beyond the human catastrophy, the battlehip losses, and the character of surprise, completely stunned traditional naval analysts. Never ever an airborne attack could have been so massive and so daring as to be successful. These analysts should have been short-sighted however, as to not see the Tarento attack, the same year but more than one year before, in November 1940.

This was a coup from the Royal Navy, which effectively sunk or damaged the whole of the Italian fleet anchored in Tarento, ruling the central Mediterranean area. And this was done, like the successful attack of the Bismark later, by a handful of antiquated biplanes, the Swordfish.

Torpedo-bombers and Zero fighters preparing to launch their second wave on boad Akagi, December, 7, 1941

Tensions with the Japanese at that time led already officers to believe a war with the “seeping giant” was not an option but a somewhat unavoidable end when the US eventually put an embargo on oil and other industrial resources. Yamamoto Isoroku, a visionary admiral that hard-pressed for the creation of a first rate naval air arm, did not lost anything of the British attack.

Seeing the war inevitable he planned a knockout blow, comforted by most top brass believing the Americans would gave up soon. The scale of the attack had simply been multiplied by the number of aircraft carriers engaged, a very advanced training and total surprise.

After two attacks and very few losses, the success of the operation had been total. Its result was twofold: Loss of the Pacific fleet (except aircraft carriers, which proved to be absolutely crucial for the continuation), and America’s war entry.

In spite of Roosevelt’s sympathy and commitment to Great Britain, this formidable slap was necessary to turn a firmly neutral public opinion and put the United States on the footing of war. Henceforth nothing could stop the giant to wake up and strike back.

The fleet oiler Neosho AO-23, sunk at Pearl Harbour. The Japanese however failed to destroy the fleet’s massive reserves of oil, as well as any aircraft carriers.

However severe the shock of Pearl Harbour was for the public opinion war, some historians would endlessly debates about the strategic results of the attack and the failure of the Japanese high command to achieve better results. Indeed, perhaps too cautious Chūichi Nagumo was vividly critized to cancel a third attack, arguing a possible American much more aggressive defense, and having secured the main objective as to sink battleships.

As any old guard admiral, Nagumo still relied on the “big guns” to decide the fate of nations at sea. This air attack was merely a very lucky diversion that achieved to restore some numerical advantage to the Imperial Japanese Navy in prevision of a future battles and clearing combined operations throughout the pacific.

Such attack indeed would have targeted the massive nearby fuel tanks of the fleet, which were still unprotected. Without oil, what left of operational ships would have been rendered immobile, including crucially the three aircraft carriers that were not there (luckily for the Americans) this day.

If the attack had been bold, both public opinion and the old naval admiralty were indeed mistaken: Certainly, most battleships present (half of which the US Navy had) had been neutralized, and theoretically, the Pacific fleet had been eliminated.

No one at that time could have predicted what the few aircraft carriers absent that day could contribute in the hard fighting of 1942, and until 1943. Afterwards, the roller-coaster of American industry outclassed several times numerically the enemy and the conclusion was logical.

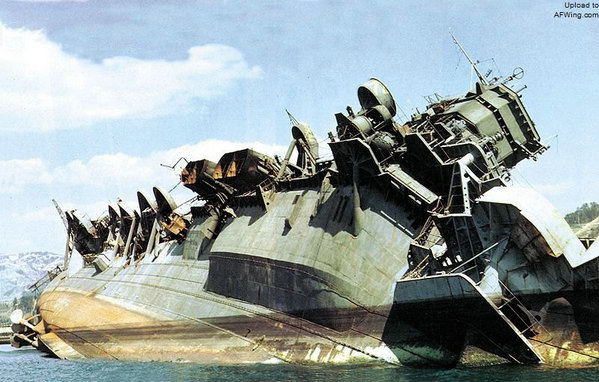

The battleships themselves were, for the most part, refloated, repaired, and completely rebuilt and modernized. They do returned to combat and participated in all subsequent engagements of the US Navy in the Pacific. Some naval historians went as far as thanking the Japanese to have “wrecked these old useless hulls” and open eyes and minds to the cause of aircraft carriers, like no event before, or since. Pearl Harbor was certainly the last nail in the battleship coffin.

The US Navy in the Atlantic

Neutrality Patrols

If US involvement in the Second World War stemmed from the Pacific (see next chapter), the effort provided by the US Navy against the axis, was to be equally decisive.

Indeed, as early as 1941, the submarine warfare against British traffic to the American continent – north and south – was the biggest threat for the Island Nation by far, the one that Churchill really feared: The absence of escort other than large ships in the middle of the Atlantic, and crucially the shortage of destroyers.

Merchant ships, although in convoy were no longer protected because of the insufficient range of action of aviation and destroyers. The U-boats, often refueled at sea, could therefore ambush these and with their wolf-pack tactics, could locate and attack these convoys in this sensitive area.

Navy’s Vought SBU-1 from VS-42 squadron in a neutrality patrol in 1940.

Some long-cruising U-boats (like type IX), although rare in comparison to other types, even skimmed the inner limit of American territorial waters so far to see the cities lights in their “second happy time” – with precise instructions, s the German admiralty did not wanted to reproduce the “Lusitania” affair.

If the government, according to American opinion, was determined to stay fiercely neutral, the Admiralty, like sailors, and captains of these ships, that collected the shipwrecked of the unfortunate torpedoed vessels at the limit of their territorial waters could not stay so for long despite strict orders. Sometimes bold U-Boats were spotted inside territorial waters.

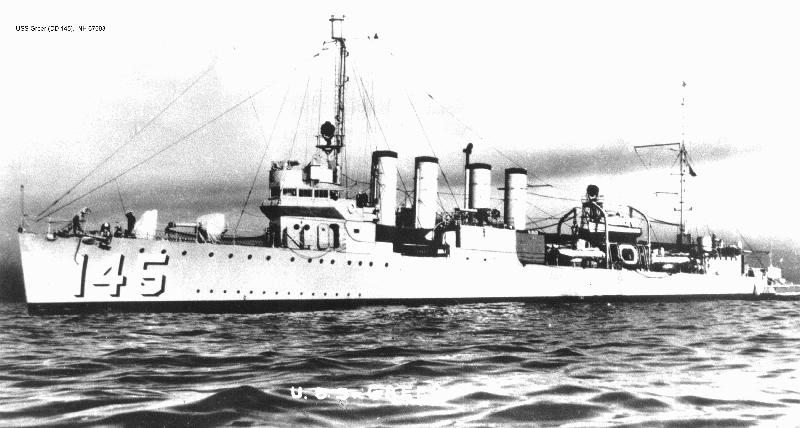

USS Greer, in the interwar. Most Atlantic destroyers were numerically still these “four-pipers”

A report stated that the American escort commander ordered all destroyers in the vicinity to rush out and open fire towards the spotted periscopes. By seafarer solidarity, captains of these ships could not remain insensitive to the fate of the British. Long before any entry into the war, some U-Bootes had been reported gunned or squarely sent to the bottom.

These actions intensified throughout the second half of 1941. American destroyers then often crossed the outer limit of the terrific waters, trying to extend their sphere of protection to the unprotected areas.

USS Anders in a neutrality patrol in June 1941. By then the “neutrality” was scarcely effective.

The Convoys

December 1941 came obviously as a shock. If the bulk of the effort will lean towards the Pacific due to the quasi-destruction of the fleet, the declaration of war also concerned Germany and Italy. Vessels of the Atlantic fleet in addition to the coast guards, were now free to escort ships up to and through the unprotected area, which was partly reduced.

Aviation was also mobilized, notably the long range PBY Catalinas, perfectly able to cross the Atlantic. But conversely, U-Boote commanders had seen their restrictions lifted. And they wreaked havoc for the freighters that at first continued to sail without a convoy, well spotted on the cities background, or all their lights burning.

The U-boats also used coastal lights to orient themselves at night and placed in ambush. One single about in a day was able to sink without difficulty all freighters and especially oilers leaving New York harbour. In fact, losses of the combined allies had been never so high. These were U-boats “happy times” from January to April 1942. From February onwards, however, the Americans organized themselves better and adopted the system of convoys, despite the resistance of certain captains.

The better-organized allies were going to strike from the end of 1942 to mid-1943, recording decisive successes in underwater warfare. At stake, new tactics, new equipment, and unexpected deciphering. Indeed, the fighting still led by the British in the Mediterranean, were largely dependent on American equipment and armaments. The supply of the island, moreover, remained always closely related to its traditional maritime routes.

The presence and action of the US Navy was therefore able to concentrate on covering much of the western Atlantic. In exchange the British provided in particular two vital systems, new asdic-sonars and Huff-Duff arrays for trigonometric locating.

The Americans were going to produce them under license and quickly equip their ships, as well as radars. Patrols of smaller ships were extended to the middle of the Atlantic, spotting U-boats and rescuing the shipwrecked. Convoys were now taken over by long-range escorts, specially built for escorting past the middle of the Atlantic, leaving no gap. Until the end of 1942, new escort destroyer types (they will be hundreds) will arrive.

Towards the end of 1942, the situation became more difficult, but the loss rates began to be fall thanks the massive building program of standard tankers and freighters by both the Canadians and the Americans. The famous “liberty ship” was produced in September. The very first was SS. Patrick Henry, a hero of the revolution who famously launched the slogan “freedom or death”.

The Liberty Ships

This episode concerns the period from September 1941 to the Japanese capitulation. Until then, 18 American civil shipyards were going to produce on a British design, no less than 2751 “Liberty-Ships”. It was an unprecedented effort compared to the number of U-boats effectively at sea.

The design in question specified a sturdy and relatively conservative type of ship (with a double hull capable of absorbing a torpedo), a simple and proven engine (conventional triple expansion engine) but capable of producing a top speed of 11 knots, enough to let down any U-boot underwater.

Speed was decisive in certain annexes, equipped with powerplants capable of providing 15 knots, this time enough to cover a u-boot on surface. Facilities were rudimentary, but known to all sailors, space was rational and generous, comfortable, and the cargo load was also largely sufficient.

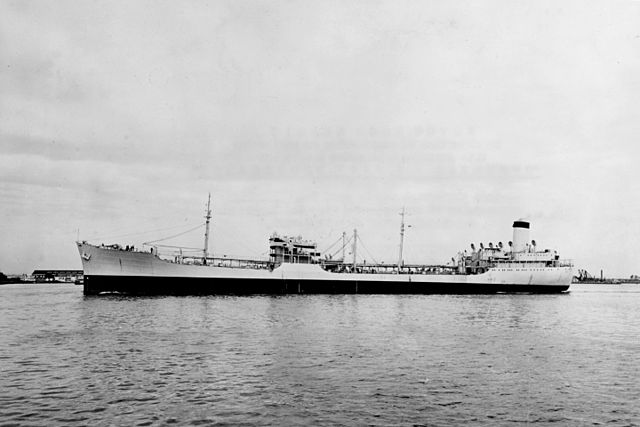

SS John W Brown

If the design and idea were British, the construction was more than 90%, carried out in the USA and Canada, in civil shipyards like that of J. Kaiser near New York.

The construction of these ships was modularized and simplified to a point where some shipyards competed to beat construction records, ranging from 244 to 230 days for the first to just 4 days and 15 hours (SS Robert E. Peary), with an average of 42 days.

In the end, the movement initiated by the Merchant Maritime Act of 1936, confirmed during the war by the Defense Aid Supplemental Appropriations Act in March 1941, only increased the pace of launching new cargo ships.

In 1943, this cadence reached a peak, with three freighters built daily in the USA. All these vessels, which were very functional, replaced the losses during the battle of the Atlantic and soon contributed to a significant increase in freight capacity. Many of these cheap ships were modified to serve as assault transports and were of all amphibious operations, especially during the crucial years of 1944-45.

Most Liberty ships also had an impressive defensive arsenal by themselves, usually a single 102 mm or 127 mm piece (5 in), and a variety of 3in (76 mm), 2in (40 mm), or 20 mm Oerlikon, all served by navy staff.

American escort destroyers

During the conflict, military yards delivered an impressive number of escort ships, mainly for ASW duties. All of them had administrative acronyms, were relatively slow (convoy’s pace and sub-chasing), moderate and specialized armaments plus good detection equipment, and a well-trained crew. Classification was as follows:

GMT – Diesel electric tandem motor drive – (class Evarts) Type of short hull, 68 ships.

TE – Turbine Electric drive – (Buckley class), 102 ships.

TEV – Turbine electric drive – (Rudderrow class), 72 ships.

FMR – Fairbanks Morse diesel Reverse gear drive – (class Edsall), 85 ships.

DET – Diesel electric tandem motor drive – “long hull” – long boat (class Cannon), 59 ships.

WGT – Gear Turbine drive – (class John C. Butler), 83 ships.

USS Harmon, TE class (naval encyclopedia illustration)

These ships played their full part in the Atlantic, where the threat of the U-boats was much more present, but also in the Mediterranean as US presence grew. In the Pacific, few were sent because of the lesser threat of Japanese submarines. The British on their side launched hundreds of cheap but effective “Flower”, “Castle”, “River” corvettes and frigates, skimming West Atlantic.

These hundreds of ships altogether managed to form a dense and truly effective escort from 1943 onwards, completed by the cover from aircraft of the many escort carriers also launched to serve in the Atlantic, and the arctic convoys bound to Murmansk.

Amphibious Operations

Amphibious operations are readily associated with the Pacific campaign, although everyone knows the famous “D Day”. Operation Overlord was only the best known of all amphibious operations led in Europe, starting with the Mediterranean. In fact, the first was carried out in North Africa (Operation Torch, November 1942).

Sicily landings (Operation Husky, July 1943) truly mobilized more forces than Overlord and was a first of its kind, introducing new vehicles like the DUKW, then it was Salerno (Operation Avalanche, September 1943, in southern Italy) and Anzio (Operation Shingle in January 1944, which almost turned into a disaster); And finally the famous D-Day (June 6, 1944) followed two months after by the landing in Provence (Operation Dragoon, August 1944).

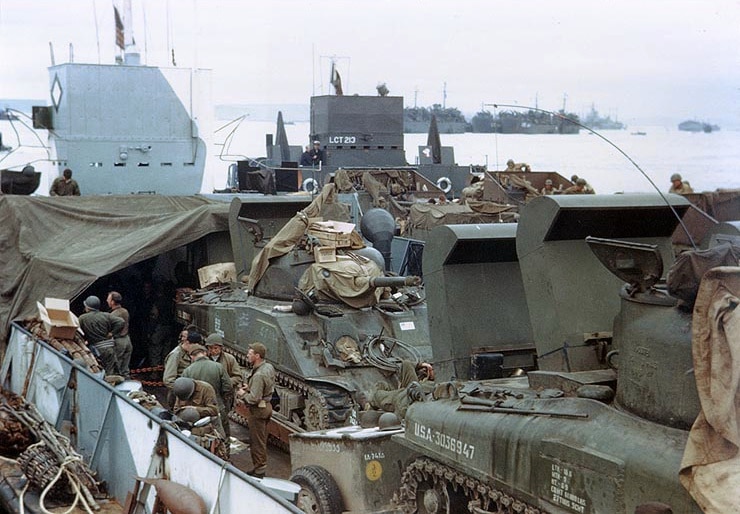

Normandy supplies in the summer of 1944. Before the artificial harbour was ready, and even after it was, most of the enormous US Army supplies fighting in and out of Normandy was provided by a rotating fleet of massive LSTs, across the Atlantic.

This was the last major operation of this style. At that time the axis were cutoff from the Mediterranean, and the Atlantic was becoming way too dangerous for the Kriegsmarine.

During these operations, many specialized ships were used. The duration of the war, the variety of situations and number of operations has been the melting pot of doctrines, equipment and tactics of amphibious warfare, or combined assault (naval and air forces) that still applies today, with the addition of the introduction of helicopters.

All these operations were carried out in much the same order: Bombardment of aviation and “surgical” strikes on artillery posts, roads, bridges, etc., followed by coastal bombardment of enemy fortifications by the fleet (often not very precise), then finally the assault itself led by the infantry and then the tanks.

The link between bases of departure and assault range was made by converted cargo ships (assault ships) modified to embark about ten barges, putting them in the water empty, the infantry then embarking by means of nets suspended on the flanks of the ship.

Once all barges were in formation and ready, the assault itself was carried out, under cover of the on-board aviation. “Amphibious assaults” have no justification other than the lack of harbours, deliberately blocked by the enemy, fortified and mined or/and totally destroyed.

The organization was essential in this type of operation, for a perfect coordination, as well as good communication and real time information. In fact, practically all doctrines related to modern amphibious operations came from these ww2 operations. LSTs for example, assault aircraft carrier (on the Japanese side), assault dock ships containing barges, and close support vessels.

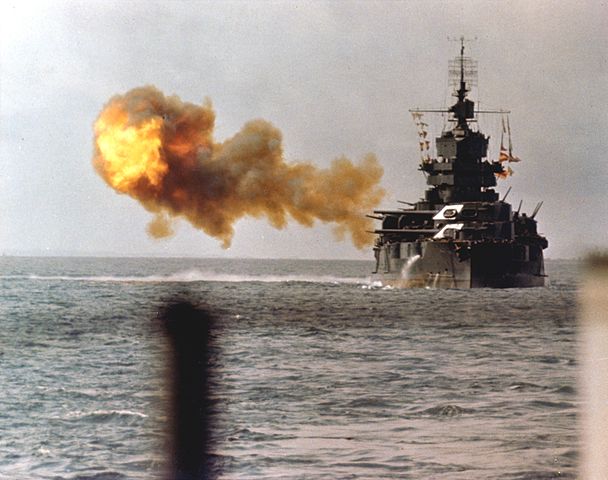

USS Nevada bombarding Utah Beach, June, 6, 1944.

Operation Overlord, the greatest of them all

This became so far the costliest, largest scale, longest in planning but also most crucial and decisive of the whole war. Its reputation is no way usurpated as a major US Navy operation and allied combined operation.

The idea to open a second front directly threatening Germany through Western Europe has been envisioned at Moskow’ second conference back in August 1942 at the insistance of Staline which then tired Soviet Forces supported the bulk of German onslaught.

Italy landings, after a complete victory in Tunisia and the taking of strategic Sicily were an idea of Winston Churchill, who like in the previois conflict, where he was already Lord of the Admiralty, lobbies to attack the soft underbelly of the axis, and make Italy leave the war.

However the quick victory never came, and Allied forces found themselves pitted, despite the Italian surrender in november 1943, against experienced German forces that expertly defended any areas, masterfully using the terrain to the point that in May 1944, the allies were still stuck in the north of Rome and by April 1945 the Gothic line still held.

Therefore these diversionary efforts were not to be arguably a successful move for the allies and it was therefore in the face of Stalin’s heavy insistence at each conference that the American command had to resolve to plan a massive landing in France in 1943.

The shortest landing spot was of course Calais, a certainty reinforced by Operation Fortitude, a great deception to which the Germans had replied by installing the bulk of their best divisions, and it was there that the Atlantic wall had the most consequent defensive works.

Sherman tanks loaded into LCTs.

The operation in itself by its magnitude required a thorough training, accomplished in England. It mobilized no fewer than 7,000 ships of any size, the first wave of infantry amounting to 170,000 men, which will be followed after securing the bridgehead by nearly 3 million additional soldiers.

Besides the Americans, who constituted the bulk of the troops, there were British contingents, Canadians, and commandos of Free France. After the safety of the various bridgeheads in Normandy, recapture of destroyed harbors by the Germans required the construction and transport on site of a modular artificial port at Arromanches, a first in history, which alone gave the logistical scale of the whole operation.

Artificial harbours

Although a British creation, the steel came from the USA, but the construction of the elements was done in England. The code name for the operation “Mulberry” became the harbour designation itself. The origin had been taken as a joke by Hugh Lorys Hughes, during a debriefing meeting after the failure of Dieppe.

The assembly of the elements, towed on site, was done in situ. The principle was simple: In the absence of being able to use the ports of the Normandy coast, the Allied command had to have a means of transporting troops and materials more easily than with conventional means of assault.

The bold idea was to have a “mobile” port could be set up anywhere on the coast. Tests followed in 1943, culminating in the construction of a composite port with a theoretical size equivalent to Dover, ie 500 ha with no less than 6 km of jetties and dykes, 33 intermediate floating intermediate platforms docks.

A good part of these elements would be concrete, hollow to float and filled on the spot, to ensure solid points of the port that was largely “floating”.

60 ships were to be sacrificed as “blockships” to constitute a jetty. The docks included metal crosses (as junctions), and 212 Phoenix concrete boxes from 2000 to 6000 tons. The 33 Lobnitz platforms connected by fixing on jacks with a beat of up to 7 meters had to ensure the transition of the tides, of very high amplitude in this sector.

Finally, there were about 15 km of floating roads called “whales”, metal platforms designed by J. Beckett (24 m and 28 tons, resting on concrete pillars).

All these elements were brought in and put in place from 16 June in Omaha Beach (Mulberry A) before being destroyed by the storm of 19-21 June. The second, more durable, was placed at Arromanches (Mulberry B).

However, the intensive day and night rotation of the assault ships, LST and LSI, as well as landings in small fishing ports around the country, allowed to land more troops than the one Mulberry. Historians today relativise the importance of their contribution to the success of Overlord.

When Cherbourg was finally captured and quickly rehabilitated, most of the traffic was carried out on this side, but the port of Arromanches continued to serve as a residual until the end of the war.

With the success of the landing in Normandy, followed by that of Provence, American naval operations were going to limit themselves to tracking the last U-Boats in the Atlantic. Cruisers and battleships crossed the Panama Canal and joined the units stationed in the Pacific for the most crucial operations of this theater.

The Pacific Campaign

USS New York leading the USN Battlefleet in 1938 – Colorized by Hirootoko JR

When one thinks of the US Navy during the war, it is obviously the Pacific who retains the attention above all. It played an essential role, reflected both by the volumes involved and by the troops (Mostly the famous US Marine Corps), whereas the army was mainly affected in Europe.

This is due to the nature of this theater, of course, but also to the respective emergencies (After Pearl Harbor the danger of a Nippon invasion on American soil seemed much more real than a possible Axis operation on the West coast).

Objectives were simple to define: One had to stand up to the Japanese after the defeat of the combined British and Dutch naval forces, and French Japanese-enforced neutrality.

The Empire of the rising sun, in a series of welwell-orchestrateditz campaigns, had succeeded in securing a vast area extending from China to the west to the Mariana Islands to the east, almost within reach of the American West Coast and Of the great industrial centers of California, as well as the Kurile and Sakhalin archipelago in the north and new guinea in the south…

Only Australia, with its meager ships, could still stand with New Zealand since the elimination of The Z Force in Singapore, and the last remains of the ABC composite fleet near Java. But Australia was targeted directly by 1942 and prepared to a possible invasion.

The Philippines Campaign

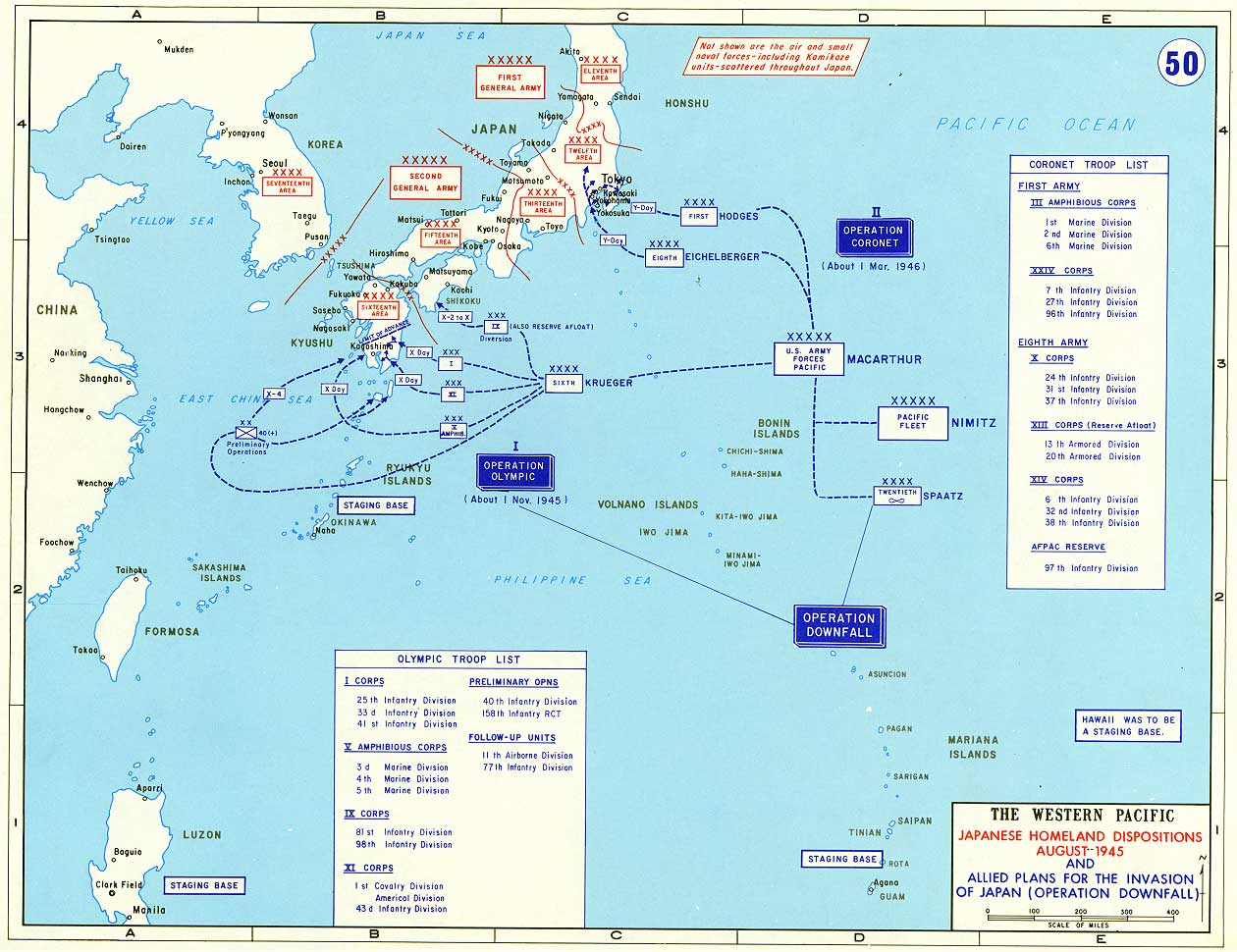

Right: Map of operations in the Pacific (US landings). The series of engagements which will take place on this gigantic theater of operation had for goal (for the Japanese) the elimination of all the American and British bases in the Pacific. Map of the Belligerents.

Guam, was the first of its bases targeted. Wake was also targeted on December 7, 1941. A few days apart, the Z (British) force was used as an aerodrome and support base for both fleet ships and reconnaissance seaplanes, Was eliminated and the invasion of Singapore scheduled. Hong Kong, the Philippines, Malaysia and Thailand were in turn submerged.

The immensity involved had the campaign divided into four main theaters: Southeast Asia, China, the Central Pacific, and the Southwest Pacific (including Oceania). The US Navy played only a small role in China and South-East Asia, a sector mostly devolved to the British (notably because the sector, apart from France, was close to its largest colony, India. ..).

Oceania was in principle vested in the Dutch, but even their forces combined with those of the Commonwealth were not in a position to reverse the course of events.

The Australian Forces, outdated in 1942, were dependent on American resistance in the pacific south-west, beginning with Australia and Papua New Guinea.

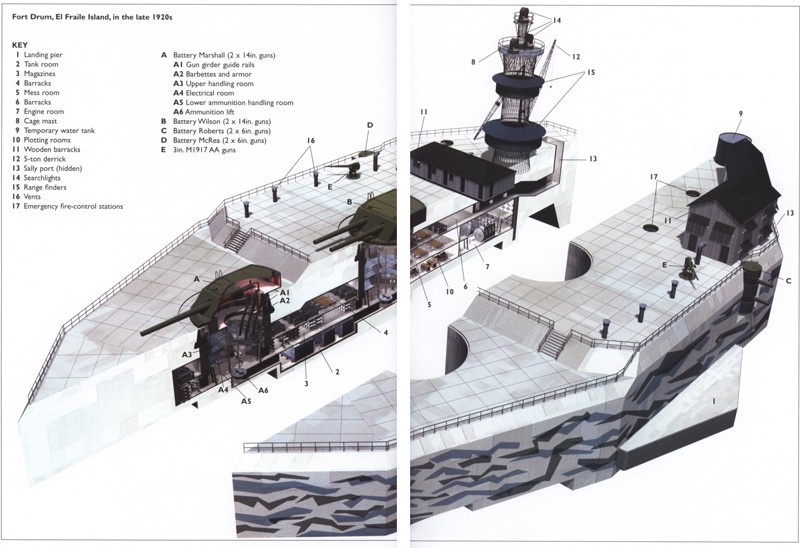

The famous “concrete battleship”, Fort drum (diagram), built on the island of El Fraile, already used as a base of artillery by the Spaniards in 1898.

Located south of Corregidor, between the peninsulae of Cavite (south) and Corregidor (north), which protected the outskirts of Manila Bay, was one of three concrete forts by the Americans in the 1910-1917 years, with Fort Hugues (Caballo) to the north and Fort Frank (Carabao) to the south, equipped with firing positions and firing direction, heavy artillery turrets (Turrets with 356 mm gun pairs).

Fort Drum, begun in 1909, was completed only with the replacement of its old 305 cannons by 13 in (356 mm) gun turrets in 1916. The Fort was shaped like a ship and had a “crew” of 320 men with complete living quarters, electric generators, forge, bunkers And stores that allowed him a near-autonomy.

Fort Drum (photo).

Fort Mills and Fort Hughes were built on Caballo just south of Corregidor, a quarter of the island rising to a height of 116 meters on its western side, armed with 17 pieces ranging from 12 to 3in (305 to 76 mm). Four miles south of Fort Hughes was located Fort Drum.

To build Fort Drum, the engineers cut the entire summit of the island of El Fraile to the level of the water; Using rock as a foundation, they built a massive 106.70 m long by 44 meters wide bunker, battled with concrete walls up to 11 meters thick. This giant blockhouse was armed with four 305 mm (from reformed battleships) guns in two double turrets, four 152 mm, and a three-piece anti-aircraft defense of 76 mm.

The southernmost of the fortified islands was Fort Frank on the island of Carabao, just 500 meters from the shore of the province of Cavite. Carabao was 30 meters high, straight out of the sea and was armed with 12 and 3 inches guns, covering the beach of Cavite.

The Philippines as an American protectorate, benefited from sizeable land forces, complete with tanks and cavalry. The Japanese led by General Homma, attacked the northern part of the island of Luzon, where they were not expected, then overflowed the Philipino-American lines by a tactic that was also used in Singapore, and advanced To the peninsula of Bataan, besieging the fortress of Corregidor.

On paper, Corregidor looked formidable. Fifty-six coastal guns ranging from 3 to 12 inches (75 to 305 mm), all in fortified bunkers or positions.

The two 305 mm pieces had a range of 15 miles, the 12 pieces of 152 mm were deadly at 2 miles, an area also covered by ten mortars of the same caliber. Nineteen other 155 mm guns could reach 17,000 meters. The AA artillery consisted of 24 pieces of 3in (76 mm)/48 caliber, many heavy machine guns cal.50 gauge (12.7 mm), and five 3in projectors.

The main concern was the supply of ammunition. There was a lot of ammunition, but not appropriate for attacking ground targets, as well as no special projectiles to provide flares at night. And what was really needed – the supply of illuminating shells for anti-aircraft defense – was also in short supply.

In spite of these tremendous arguments, which the Japanese had bypassed, the campaign ended with the surrender of General Wainwright and a terrible fate for the many prisoners on the fatal “Bataan road” and captivity in Luzon itself in factories and Mines. There will be a full chapter on the “Battle of the Philippines”.

The battle of Wake

Wake was originally a seaplane base (for the Pan American Airlines as well as the US Navy), a relatively well defended aerodrome and a supply point for light naval units.

On 19 August a garrison was stationed there (the first Marines defense battalion), protecting 68 members of the US Navy and 1221 civilian workers working on the extension of the aerodrome and other works. The defense of the island consisted of six coastal 5-inch guns (127 mm) Twelve 3in (76 mm), and eighteen cal.50 nests, plus thirteen 30 cal. nests of varied provenance.

The local squadron counted 12 F4F Wildcat naval fighters under orders Of Commodore Cunningham. Following the attack on Pearl Harbor and the Marshall Islands attack, the Japanese were able to launch a raid by thirty-six G3M3 bombers on Wake on December 8. The attack caused considerable damage, causing 23 dead and 11 wounded, and only 4 Wildcats has been spared (they however shot down two bombers the following day).

At the dawn of 11 December, an attack by three cruisers and eight destroyers, conveying 450 men, was repelled by the combined action of the fighters and coastal artillery. The destroyer Hayate was sunk and the Yubari badly hit, the Kisaragi sunk by the four Wildcats equipped with bombs.

This unexpected resistance led the Japanese command to detach two aircraft carriers, Soryu and Hiryu, for the second assault on December 23rd. In the meantime, a support force was hurriedly mounted (Task Force 11 under Rear-Admiral Fletcher) with USS Tangier, Saratoga, a supply tanker, Astoria, Minneapolis and San Francisco cruisers and 10 destroyers, carrying the 4th Marines battalion and a squadron of Buffalo fighters, as well as impressive ammunition reserves.

While this fleet was sailing towards Wake, the Task Force 14 (Lexington, 3 cruisers and 8 destroyers) was conducting a diversion attack to the Marshall Islands. But on December 22, the reconnaissance signaled the presence of 2 battleships and 2 aircraft carriers of the IJN near Guam, and the commander-in-chief of the US Navy, Admiral Wiliam s. Pye, for fear of losing his precious aircraft carrier, renounced his action and turned back towards Pearl Harbor.

Right: Wrecked Wildcats on Wake island. The Grumann F4F Wildcats played a crucial part in December 1941. One of the pilots, Capt. T. Elrod, posthumously decorated with the medal of honor, destroyed a destroyer and shoot two Zeros the same day.

Right: Wrecked Wildcats on Wake island. The Grumann F4F Wildcats played a crucial part in December 1941. One of the pilots, Capt. T. Elrod, posthumously decorated with the medal of honor, destroyed a destroyer and shoot two Zeros the same day.

The second assault was carried out on 22 December after intense preparation of artillery. 1500 troops of imperial marines, supported by naval aviation, disembarked in force in the evening. The battle, desperate after the loss of the last remaining aircraft, and the knocking out of all positions of artillery, nevertheless continued obstinately all night and morning.

The last survivors, exhausted, surrendered in the early afternoon. Most were Chamorro workers, a few Marines and US Navy personnel that were taken prisoners. The last were deported, the first were used to build entrenched positions and blockhouses on behalf of the Japanese navy.

If sporadic attacks followed, the island was gradually isolated and a blockade was instituted, with regular bomber raids. In October 1943, a massive air raid from the Yorktown caused an attack on Admiral Sakaibara to be assaulted, and he executed the remaining civilian and Marines prisoners (He was later tried for war crimes and hanged). The Japanese garrison surrendered in September 1945.

The battle of Guam

It was the southernmost island of the Marianas, and the largest, already used by the Spanish, but taken over by the Americans after 1898. A base was built that covered a particularly wide and strategic area of the Pacific.

Subsequently, the Germans became masters of the rest of the Marianas, but lost these possessions in favor of Japan during the First World War. Neither the Japanese nor the Americans fortified these positions. The artillery was removed and there was only one USMC seaplane on duty in the 1930s.

The capture of Guam by the Japanese was considered as early as March 1941. From the reconnaissance of the aviation they were able to draw a precise map of the island. When the Japanese attacked on 8 December (local time), there was only a kind of slightly armed militia, the Guam Insular force guard, reinforced by the minesweeper USS Penguin for a total of 246 men and 80 policemen, armed with guns. Attacked by nearly 2,500 naval troops disembarking in four places, supported by the artillery of 4 cruisers and 4 destroyers covering the assault, preceded by air raids (which lasted for 48 hours), the defenders surrendered, taking nine dead and 35 wounded. The Japanese had six casualties.

PT-105 Elco PT-Boat

Guam remained under Japanese rule until June 1944. The American invasion of Saipan was scheduled and Guam was to follow. However, the relentless resistance of the Japanese in Saipan contradicted this optimistic plan. It was only on June, 21 that a force first bound for Saipan landed west of Guam.

The size of the island (48 km) and time given to the Japanese to prepare their defenses, allowed them to hold a moment, despite their numerical inferiority. The conquest of the island was devolved to the 3rd Marines Division reinforced by the 77th infantry division.

The Japanese multiplied night infiltration and counter-attacks in force, all of which were repulsed with great losses. The fighting lasted for the whole summer. The port of Apra and the airfield of Orote were captured and the offensive continued in difficult conditions, through the jungle and in the rainy season.

But after the decisive battle of Mount Barrigada, the Japanese defense collapsed. Survivors took refuge in the north, but the fighting did not cease until August 10. There was no surrender among the Japanese which committed Seppuku.

The Defense of Australia and New Zealand

With the destruction of the Pearl Harbor fleet, and the capture of the Philippines, Guam and Saipan, the Americans had their Pacific lines of communication cutoff. The Japanese secured their future gains, in theory delaying the US Navy counter-offensive by almost a year.

They did not take long to pursue their objectives. Indeed, in early 1942, the Japanese seized the northern coast of New Guinea. The route to Australia was opened to them after the liquidation of the last allied forces of the sector.

The Kokoda retreat

From there, they launched a devastating raid on Darwin in February 1942 that shocked the Australians , followed by a submarine raid in Sydney. The government relied on American military aid, sent troops to new guinea while preparing its defense for an imminent invasion.

At the express order of President Roosevelt, General MacArthur was instructed to set up a defense plan for the whole area. On the tactical level, Doolittle’s attack on Tokyo, although without material consequences for the Japanese, was a boost to the allies morale, and a blow for the Japanese, while surviving Australian-Dutch forces continued a guerilla war in Timor.

The longest and best known of these episodes remains Guadalcanal and the reconquest of the Solomon Islands. But the ANZAC (Australians and New Zealanders) until 1944, delivered a merciless battle against the Japanese for the reconquest of new Guinea, a vast remote territory, still savage at the time.

The Battle of the Coral Sea (4-8 May 1942)

This was the first major naval battle of this conflict. Crucial, for at that time the means of the US Navy were almost ridiculous compared to the Japanese, with only two battleships and a handful of cruisers and destroyers. But their might rested on the aircraft carriers, remaining intact and about to play their part.

The kick-off was Operation MO (conquest of Port Moresby and Tulagi by the Japanese, strategic points to hold the Solomon).

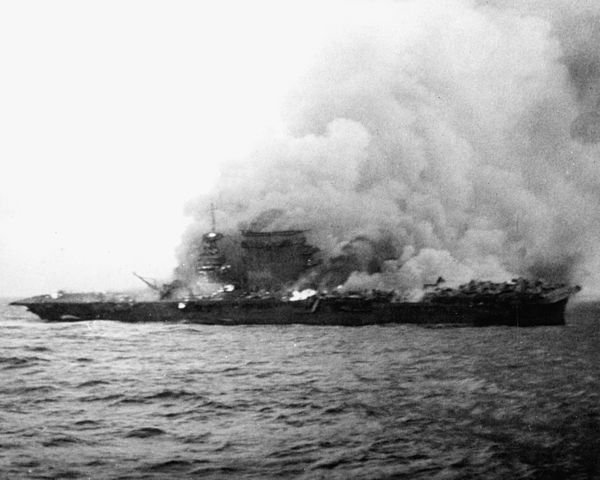

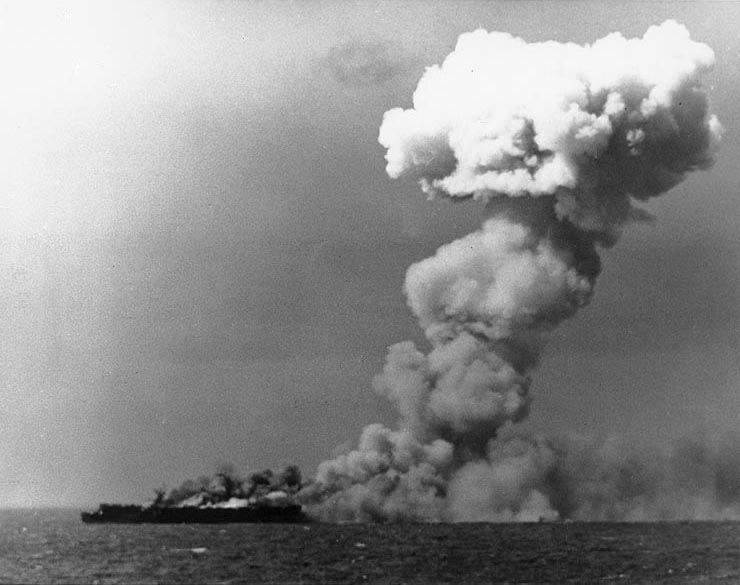

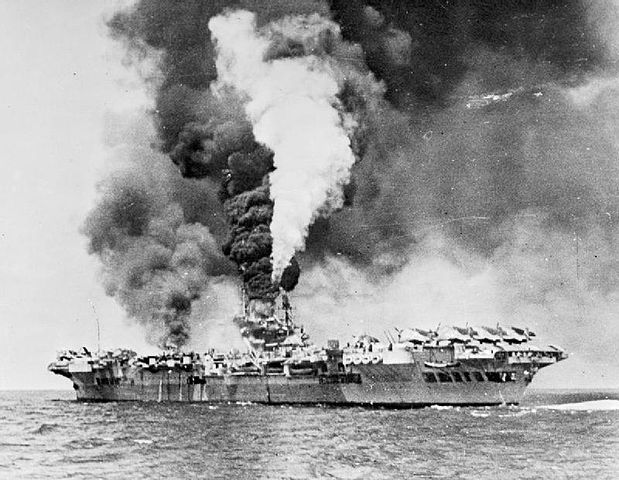

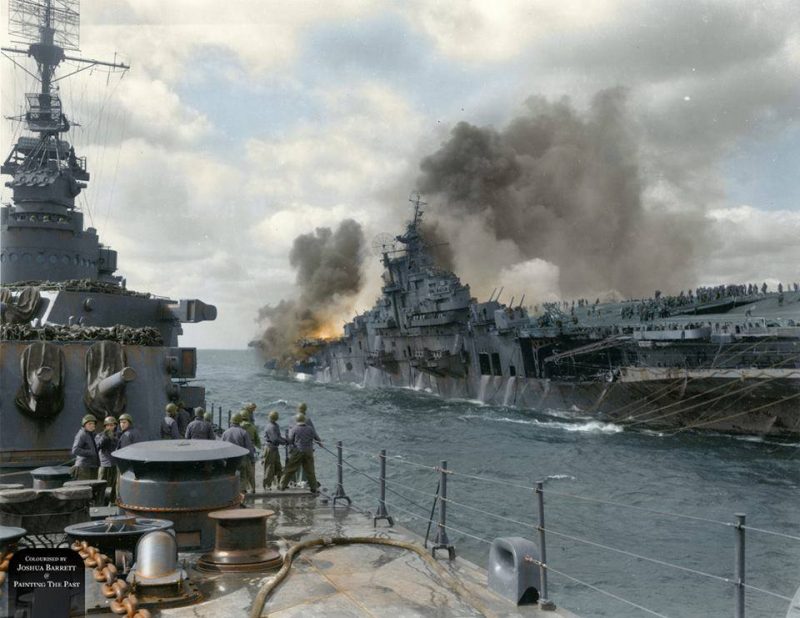

USS Lexington burning

While the Japanese were busy at Tulagi, they were surprised by aircraft of the USS Yorktown, part of the combined American-Australian fleet led by Admiral Fletcher. A game of cat-and-mouse began then, both sides sending reconnaissance planes.

On May 7, the Hosho was sunk by the Americans while the Japanese sunk an American destroyer and a tanker. On 8 May, attacks were redoubled as the two fleets went closer.

The Zuikaku was sunk and on the American side the Lexington was sunk and the Yorktown badly damaged. But the latter was sheltered and later repaired in record time (to serve decisively but fatally a month later).

Shokaku being bombed, trying to avoid torpedoes

In view of the losses suffered, it was a tactical victory, Pyrrhus-style for the Japanese. The Americans had only Saratoga and Enterprise left, but the Japanese were obliged to renounce the attack of Porte Moresby, now without the protection of the two units lost.

In fact, this vulnerability was exploited by the US Navy during the Solomon campaign, so it was overall a strategic American victory.

The Battle of Midway (4-6 June 1942)

Douglas TBD devastators of VT-6 Sqn onboard USS Enterprise. All but one returned.

Much more decisive and only a month after the Coral Sea battle, this pivotal naval battle was the turning point of the war in the Pacific. The US Navy rushed their only aircraft carriers left available in the Pacific, the Enterprise and Hornet (Spruance), plus the Yorktown, miraculously repaired in no time (Fletcher).

Opposite, a composite force divided into three fleets, including battleships, cruisers and 4 large aircraft carriers, the spearhead of the whole Imperial Japanese Navy, with the intention of seizing the Midway atoll.

These aircraft carriers, under the command of Nagumo, were grouped into two divisions (Hiryu and Soryu, Akagi and Kaga). Yamamoto himself was in command of a fleet of battleships, another was in charge of conquering Midway.

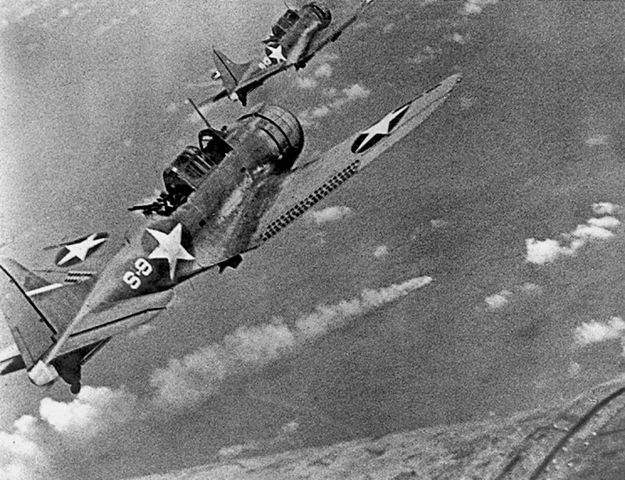

Douglas SBD-3 Dauntless dive bombers of the VS-8 over IJN cruiser Mikuma, 6 June 1942.

The two fleets searched for one another and attacked each other with waves of torpedo carriers and dive bombers. Japanese decision to keep aircraft on board and change their weapons at the last moment had disastrous consequences, loosing four aircraft carriers, while the Americans, facing a resolute and skilled defense by the means of Zero fighters and AA artillery.

Taking huge losses, they attacked in two successive waves, one of low-flying torpedo bombers diverting the Japanese so as the dive bombers had open field to operate). With luck on their side, the US Navy only deplored the loss of USS Yorktown.

As a result, the Americans made a (temporary) halt to Japan’s naval operations throughout the Pacific Northwest. The final victory at Guadalcanal in 1943 is partly a consequence of that decisive victory, but it took months of hard fighting, mainly around Guadalcanal and the “iron bottom” slot to take away from the Japanese their naval supremacy in this sector.

The campaign of the Gilbert and Marshall Islands (1943-44)

The Gilberts were occupied by the Japanese three days after Pearl Harbor. The first American assault was carried out on Makin Island at the end of 1942.

It took several months to see a new large-scale operation against the Gilbert (Operation Galvanic), this time against the much better defended Tarawa.

The island was only painfully conquered after a furious three days onslaught, won only by colossal means on November 23, 1943. Finally the capture of Apamama at the end of November 1943 completed this operation. The American forces could now concentrate on the Marshall Islands.

But the forces set up a siege, rather than repeating the sweeping assault of Tarawa. Thus the atoll of Milli was isolated, and the garrisons of Kwajalein, Eniwetok and Majuro were reduced to starvation. The fiercest battle was the capture of Kwajalein, a rocky and featureless atoll.

It was carried out in January 1944 by two divisions of marines and Army infantry.

The battle ended on February 5, with the death of practically all the Japanese, Korean and indigenous workers of the island. The taking of the Marshall Islands was an indispensable milestone for the continuation of the assault towards the Pacific north-west.

The campaign of the Mariana Islands and Palau (1944-45)

This campaign (Operation Forager) started in June 1944, and was only completed in November. The first objective was to support the reconquest of the Philippines and to provide air support for other operations, as well as (and above all) the installation of a strategic bomber base able to reach Japan (B-29s).

For Japan, however, this string of islands was considered the “inner defense line” of mainland Japan, and they fully engaged in the struggle. On one hand kamikazes, on the other, a fierce, merciless, no-surrender fight on the Saipan and Tinian islands.

A LVT2 Water Buffalo loaded with Marines en route to Palau.

The Battle of the Philippine Sea (June 1944)

This was to be the largest naval battle on the XXth century. The fleet (or more precisely the TF38 commanded by Admiral Fletcher) played an essential but not decisive role: The bulk of the offensive was led by the infantry.

The opening battle of this campaign was that the Philippine Sea air supremacy battle, also known as the “Mariana Turkey shoot”, given the staggering losses of Japanese aircraft, both from now seasoned American pilots, flying on the successor of the Wilcat, the Hellcat pitted against mostly novice Japanese pilots, but also because of the plentiful AA artillery.

In the light of the past struggles, it was particularly reinforced, including on the refurbished battleships previously “sunk” at Pearl harbour. The standard was now composed almost exclusively of long-range 3in (76 mm) pieces, FLAK-style, the formidable quadruple 40 mm Bofors for the medium range, and the numerous Oerlikon 20 mm for the short Range, all guided by radar.

They literally were bristling on the deck and superstructure of all ships for the US fleet, setting up a “steel wall” in front of the enemy. This artillery indeed was responsible for three-quarters of the losses of the Japanese Naval Aviation.

The “turkey shoot” of the Mariana was a part of the battle of the Philippine Sea, the 5th and last major “symmetrical” battle of the Pacific.

The Japanese, who regarded these islands as vital-and rightly so-were literally throwing all their strength left into it. But at that time, assets completely changed. American fighters were now more numerous and better in quality than the fragile Zero and the pilots well experienced.

They were led by aces such as David McCabbard, Robert J. Foss, Cecil B. Harris, Douglas “Flash” Gordon or Stanley “Swede” Vejtasa, more motivated than ever. Other names were added, such as the famous Greg “pappy” Boyington who inspired the 1970s “baa baa black sheep” serie, while Richard I. Bong, distinguished himself as the top ace for the USAF with his twin-boom the P38 Lightning.

In this battle, the last opposing experienced pilots, some being Veterans since 1937 in China had been killed. From now on, only young recruits will face Americans.

The battle of the Philippine Sea was, however, a partial success for naval aviation: The evening fell when finally Vice-Admiral Mitscher, commander of the TF58, ordered the take off of the whole Aviation available which almost missed the retreating fleet at sunset.

The Hiyo aircraft carrier, two oil tankers, and four other vessels were sunk, for the price of 20 aircraft shot down during the attack. But ultimately 99 out of 550 will be lost due to night landings, for which pilots were not properly trained. The vice-admiral ordered all lights to be turned on to guide the pilots, but many of them fell short of fuel after several attemps.

In the end the best score was signed by two US submarines in ambush, the USS Albacore and Cavalla, sinking the Taiho (Admiral aircraft carrier of Ozawa), and the Shokaku, another large wing carrier.

The Battle of Peleliu

Following Salipan and Tinian, which were costly battles in men, Peleliu, the largest Palau island, a rosary in the southeast of the Philippines became the theater of another bloody confrontation, supported by the fleet (most of the inexperienced gunners missed the Japanese dugouts as at Saipan).

2000 of the Marines and US army troops were lost, as well as 10,000 Japanese which as usual, did not surrender. 73 days of hellish, inhumane fighting, a campaign that began on 15 September and ended on 27 November.

Latest marches before Japan (1945)

The great strategy of reconquest had diverged since the beginning of 1944 on the continuation of operations: Douglas Mac Arthur, faithful to his promise, wanted to take over the Philippines, then Okinawa before attacking Japan itself.

But the size of the Philippines and of the Japanese troops present, conducted Admiral Chester Nimitz to cut short by taking directly Okinawa and Formosa, attacking Japan by cutting it off from China.

President Roosevelt, desirous not to let the conflict escalate, allowed the two campaigns to take place simultaneously. At that time, the need for troops in Europe was reduced, and it soon fell after May 1945.

The second campaign of the Philippines (1944-45)

As commander-in-chief of the south-west pacific sector, General Douglas MacArthur, who famously declared “I will return” to those left to fight in Corregidor, now headed newly formed divisions of the US Army, and reinforced Australian and New Zealand divisions, mostly veterans of new guinea.

These forces long prepared for the invasion were supported by heavy bombers based in the reconquered islands of the Marianas and Palau.

USS Princeton burning (Battle of Leyte gulf)

In September, with the help of Chester Nimitz, who commanded the central pacific sector, Morotai (north of the Dutch Indies) and Rabaul (west of the Philippines), were taken and converted into airbases for close support.

Obviously, another, even closer support came from the navy, namely three task forces detached from the central pacific sector, one spearhead, commanded by Bull Halsey, another in charge of the landing and its cover, and the last in backup naval support. The sector chosen was Leyte, in the center of the Philippines, so as to cut the Japanese front in two.

THE BATTLE OF THE GULF OF LEYTE (25-26 October)

This was the last major naval confrontation of the Pacific War. After that, the Japanese definitively lost the initiative of the operations, due to lack of ships and lack of fuel.

This confrontation, of epic scale because of the amount of resources engaged on both sides, actually took place on three sectors, including the battle of Surigao Strait, Samar, and the battle of Engano.

Escort carrier USS St Lo (Casablanca class) exploding, battle of Surigao Strait

The plan, tactically sound and partially successful of Admiral Ozawa, the heroic resistance of the Seventh Fleet, dominated from the head and shoulders by Admiral Kurita fleet, And the blunder of “Bull” Halsey in pursuit of the Ozawa bait fleet through the northern Philippines became legendary.

After the success of the American Navy in securing a bridgehead at Leyte, land operations continued until April-May 1945. Meanwhile another force landed in December 1944 at Ormoc.

The 6th Army, well supported by the Filipino guerrillas, took Mindoro, a prelude to the great final offensive on Luzon, the great northern island, including the industrial centers of Manila and the bulk of the Japanese forces.

The last offensive was carried out on Mindanao in April 1945. However the last pockets of resistance did not surrender until August 1945.

The battle of IWO JIMA

Iwo Jima, nicknamed ‘Devil’s Island’, was one of the last marches before Japan itself (precisely south of Tokyo). Considered as sacred ground, it was probably the costliest battle of attrition of the whole campaign (“Verdun of the Pacific”), despite being more than 2,000 kilometers from the Japanese coast.

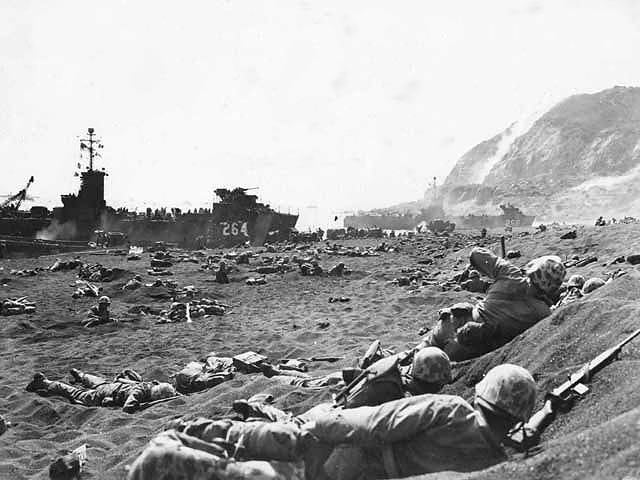

A heavy bomber base was of course planned to conduct more rotations than Saipan, which was far away, and to provide escort coverage. This was a smelly volcanic island, with sulfur and black sand, a 8-kilometer Japanese land, with a relief of 166 meters to the north, the Japanese “head” (eyes), fortified Mount Suribachi.

The garrison was commanded by General Kuribayashi which dug a complex of caves, galleries, shops, armories, and shooting stations, some buried on the beach, while some artillery positions battering the beach were encased in the rocky summit. In fact his ably set up deep defensive system was prepared for a long, protracted and costly assault.

Marines on Iwo Jima beach, an LSI (Landing Ship Infantry) can be seen in the background

The Suribachi played the role of a “natural blockhouse”, and all the bombs of aviation and incessant pounding of the US Navy did not succeed in destroying firing positions, which often revealed themselves only for a deadly burst. Infantry was committed to clean-up the mount.

In the end, the battle for Iwo Jima lasted more than one month (36 days), with last-minute night charges from Japanese suvivors, although the landungs took place after a preparation of only three days. Before that, periodic bombardments, then regular ones began in June 1944.

The island was declared “safe” on the evening of 26 March, but sporadic shooting continued. Nearly 3,000 Japanese were still left inside the galleries, preferring to commit suicide instead of surrendering.

The last surrendered in 1951. Tactically, the capture of the island proved particularly costly in men, as for the first time more Americans had fallen than Japanese. For the latter, night raids and “banzai” charges took their toll, while others were burned or killed by grenades and flamethrowers deployed during the “cleaning” by the Marines.

The aircraft carrier USS Bismarck sea was attacked by kamikazes and sunk, many others more or less severely damaged.

Although this costly operation was criticized, the island was quickly converted into an airbases for B29s. It served as a route and relief base for the most famous B-29s, those responsible for issuing the A-bomb. No other position Was appropriate. Moreover, the experience gained was reused in Okinawa, reducing the rate of American losses.

The battle of OKINAWA

This large island (nearly 50 km long) was a Japanese land, the southernmost and largest of the Ryukyu Islands, last step before southern Japan.

It was the object of the largest landings of the second world war (Operation Iceberg). Almost all the allies participated. The means the numerical superiority in ships and planes were absolutely overwhelming for the Japanese Navy, which deprived of fuel and manpower, could not hope to influence its course.

However, “suicide weapons” of all kinds were used like explosive fast boats and human torpedoes. This was also the last and fiercest Kamikaze onslaught of the campaign.

USS Bunker hill hit by Kamikazes

The greatest danger to be faced by the American Navy were indeed suicide attacks. Much more effective than conventional attacks, these prefigured guided missiles. Before the era of electronics, the only comparable weapons were German Henschel self-propelled smart bombs.

It has often been said that Kamikazes were the result of the combination of two factors: The lack of experienced pilots, and lack of fuel (for the return trip). If the second is true (Even the Yamato sailed for a mission of the same kind with just enough fuel to reach its destination), but a plane filled wih gasoline was more effective when hitting a flight deck.