One of the forgotten gunboat-size Chinese cruisers – In 1880 the concept of cruiser was rather new. Not long ago, mixed Frigates were still the norm. This was a time for transition in which Vickers-Armstrong ruled the trade and wrote the book, providing cheap ‘cruisers’ to the world. Countries still with a young shipbuilding industry such as Italy or Japan purchased protected cruisers, and China was no stranger to this as well. Given limited resources at that time, everything was better than the motley collection of sometimes hunded-year old sampans and junks armed with bronze or wooden cannons and firelances.

Nothing could oppose aggressive Western trade backed by the fleet of the British and French especially in 1840-57. Concessions were obtained by force, and in 1860 Russia annexation north of the Amur, USA’s ‘punitive expedition’ against Korea in 1870, Britain’s war to gain Burma the next year, all contributed to raise the Imperial court’s concerns about their fleet.

The change started when the Foochow and Kiangnan shipyards, reorganized and helped by Westerners started to deliver the first Chinese armed steamers. In 1869 already, the Foochow fleet was created. From 1875, the Empress authorized a global naval budget for all maritime provinces. Minister Li Hung Chang later started to reorganize the disparate fleet and started to create a modern navy in 1880, purchasing ships abroad. The most impressive was the order of two ironclad to German shipyards. The fleet was now slowly reorganized by British Officers.

Context: The Sino-French war

In 1882 however France had views on Indochina, at the time considered as China’s backyard. The process started by the attack on Tourane in 1858 by Rigault de Genouilly’s combined French-Spanish forces, which deposed the hostile (to catholic missionaries especially) Nguyễn dynasty. A new compaign started which ended in 1862 with the Treaty of Saigon granting new concessions to the French, and additional provinces fell under French control until 1867, soon called the French colony of Cochinchina while in 1863 the Cambodian king Norodom requested French protectorate. Further extensions camed with the Tonkin campaign in 1883–86 generally called also the “Sino-French war”. Until 1894, Indochina was formed by the addition of Annam, Tonkin and the Kingdom of Cambodia and Laos.

But in 1881, already Henri Rivière’s expedition in Tonkin and Battle of Paper Bridge in 1883 accelerated the degradation of relations between France and China, since in 1882 the Vietnamese Government seeked help from Liu Yongfu, leader of the elite black flags troops, backed by China. Rivière was beaten but the Black Flags were beaten in turn in two more battles whereas a protectorate over the Tonkin took place. Negociations to avoid war and attempts to the German government to delay the delivery of two ironclads for the Beiyang Fleet did not succeed.

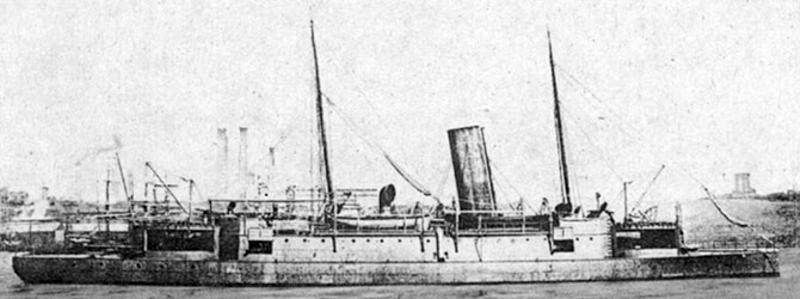

The 1880 Chinese cruiser Chaoyong, British-built for the Beiyang fleet.

Order of the Pao Min at Shanghai

In this context, the Pao Min was ordered for the southern fleet (Nanyang), the most likely to clash with the French, in October 1883. Also called Baomin (保民), this vessel was single of her class, and a “cruiser”, receiving at least some protection. She was not however a “protected cruiser”. The latter received and armoured deck over the engines and magzaines, and gun shields. The Pao Min was launche din January 1884 and completed in October, so relatively quickly.

The Nanyang fleet would comprise the screw frigates Hai-an and Yu-yuan (delivered 1872), the unprotected cruisers K’ai Chi and Kai Che (delivered 1884), Nan Shui, Nan Shuin, and Nan-jui of the same type (1884), the cruisers Nan Ch’en and Nan Chin (1884), and the Paomin. The next year, the unprotected cruisers Ching Ch’ing and King Ch’ing were ordered and the Hian T’ai and Huan Tai in 1887. The Pao Min was ordered locally to the Kiangnan DYd in late 1883.

Seeing various sources, Pao Min is described sometimes as a “cruiser”, therefore receiving some limited protection, while others, among which the respected Conway’s books, classed this ship and an unprotected cruiser.

Any case, this vessel was small, displacing 1477 to 1480 tons standard for dimensions of 64,9m (oa) by 11m wide and 4,27 m in draught. Her steam reciprocating engine was rated for 1900 KW and this power was backed by schooner rigged sailing. Zdditional sails were customary of the time. Her armament was mostly German, two 150/35 mm Krupp guns (6 in) and six 120/35 mm (5 in) plus four QF 47/20 mm guns.

Design of the Pao Min

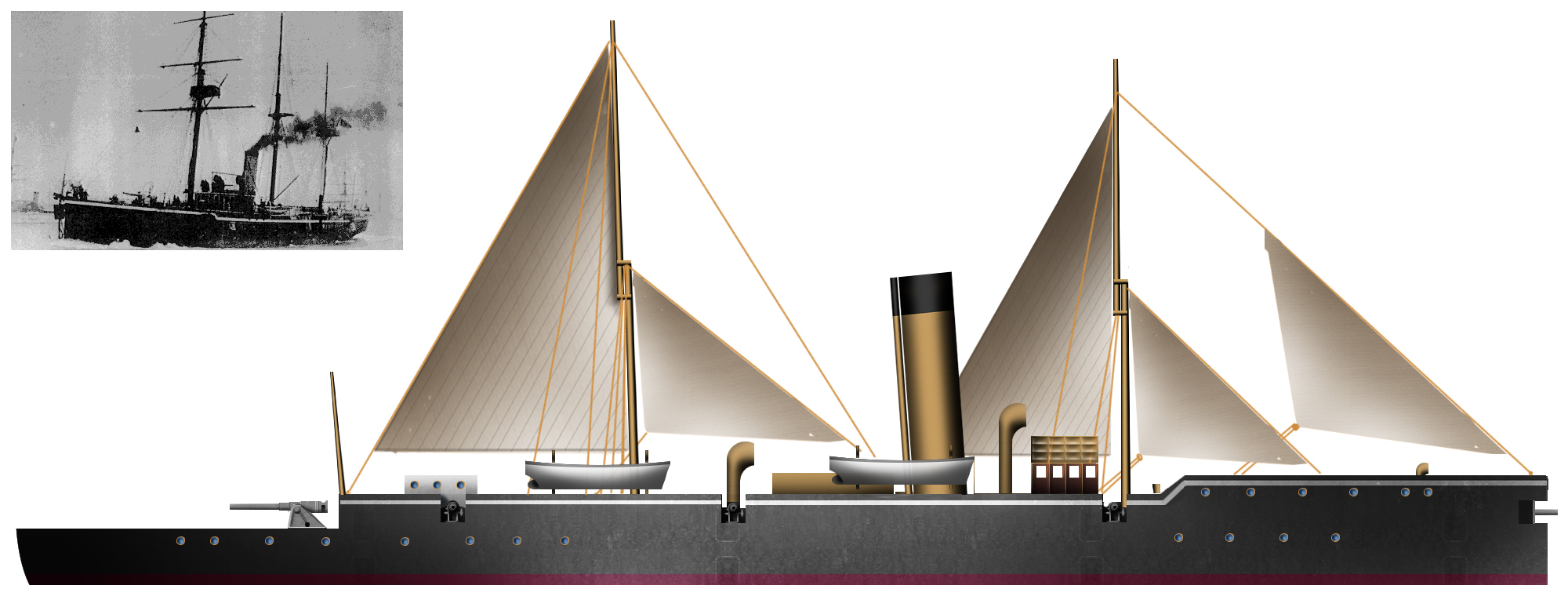

After crawling the internet this is the only photo i found of the Pao Min. It is contradictory to the usual description of a two-masted ship but the hull, unique funnel and superstuctures are coherent. According to battleship-scruiser.uk, the photo relates to the pao Min in 1889, so after the Sino-French war. A close examination of the bridge superstructure shows what its seems interesting woodwork.

The locally-built Paomin was laid down in Kiangnan shipyards. This was part of the Kiangnan Arsenal complex and General Bureau of Machine Manufacture of Jiangnan. Now the yard is called Jiangnan and is still the main southern Chinese naval yard today. The arsenal became the largest in Asia, procuring most of Chinese 1870-90s weaponry, but also the yard produced the first Chinese steam boat (the Huiji) in 1868 and the first domestically produced steel in 1891.

This ship was a Schooner-rigged, steel-hulled cruiser. Information is scarce to say the least about this obscure cruiser, but since no data could be found about her armour protection, if any, the designation given by Conway, page 399, must be closest to the truth. What was an unprotected cruiser ? A ‘cruiser’ in general was supposed to be a gun-armed vessel, faster and more heavily armed than a gunboat, at least in the 1880s. The fact that she was not given any protection at the time some received limited armour over the magazines and engines, plus gun shields, make it more vulnerable but also cheaper. There is just one known photo of the vessel, which makes this post less bare.

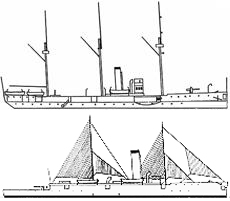

The two profiles allegedly attributed to the Pao Min/Baomin. The first is from navalhistory.flixco.info and shows a ship with two large sponsons guns, but the right three masts also in the photos but it’s unlikely the Pao Min. The second one if more faithful to Conway’s description.

As shown by the photo, and the reconstitution made and displayed in navypedia (no profile in Conway’s), the Pao Min was a conventional three-masted vessel. The steel hull had a straight bow which extended with a ram underwater. The stern was raked and looked like schooner sterns of the time, probably well decorated and housing the officers quarter. The hull, painted black, was not flush deck as there was a small break in the forward deck, then walls pierced by three ports either side, and the walls ended at the rear on the quarterdeck to left the aft Krupp main gun the best traverse opening. What was unusual was the forward gun was placed in a closed trap in the bow not on the main forward deck above. Therefore, despite its absence of shieding, it was protected by the hull itself.

This design feature was rare at the time for main guns (but not unusual for lighter guns in traversing barbettes). The hull, 64.9m pp and 69.4m overall was low on the water, therefore, this opening was probably very wet in anything but calm seas. The 4.27 m draught was important nonetheless so her use on rivers was limited to the Yangtze. Appearance as built apparently changed in the 1890s. The photo attributed to the Paomin shows three masts and a raked stern. In the 1890s and according to Conway’s short description, she was two-masted and there is no mention of a raked stern. It is likely that Pao Min lost her mizzen mast. A simple pole is shown on the 1890s appearance where the mizzen should have been.

Sources are diverging a bit about the precise caliber of the various guns carried by the cruiser. Conway’s is less precise with 5.9 in guns (150 mm) and 5-in guns (127 mm), two 3-pdr, while Navypedia is clearer by giving the calibers in millimetres: 149 mm or since its a German nomenclature 14.9 cm/32 RK L/35 C/80. This meant these main Krupp guns were 32 caliber long, rifled, and rear-loaded. The two guns, called 15 cm Schnelladekanone Länge 35 were brand new in 1883 as the arsenal just proposed them for export. These became very popular guns, rivalling Vickers products worlwide. In addition to China, which purchased many of these for their ships, fortesses and land troops, the gun was also used by Austria-Hungary, Denmark, Japan, The Netherlands, The Ottoman Empire, Romania and Spain.

Widespread among Chinese cruisers, these guns had separate loading cased charge and projectile, firing a 45.6 kg (101 lb) projectile of a 149.1 mm (5.87 in) 35 caliber. The 5.8 tonnes loading system was a horizontal sliding breech block. The gun elevation was -7° to +20° and rate of fire about 4-5 rpm for a well trained crew. Muzzle velocity was 650 m/s (2,100 ft/s) and maximum firing range 10 km (6.2 mi) at +19°. One was placed as said above in the bow port. The gun was on rails and tracted forward to fire and the port was closed when not in use. The opening allowed some limited traverse, about 60-70° only. Certainly less than in a standard deck position. As said also, it could only perform well in calm weather. Splashed would have obscured it completely.

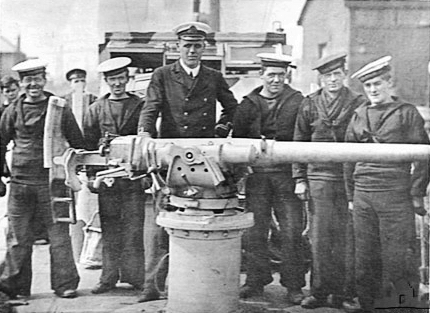

A Royal Navy Hotchkiss QF 3-pdr (47 mm)

The secondary armament comprised six Krupp (presumably) 12cm/32 RK L/35 C/80 guns, all placed in side ports on the main deck. Traverse was also limited. The first pair was just abreast the foremast, the second behindd the funnel and the third between the main and mizzen masts. In addition, the ship were equipped to deal with early torpedo boats and other close threats with two French Hotchkiss ‘3-pdr’ also 47mm/40 Hotchkiss guns. The latter were unprotected but its is difficult to locate them on the ship, most probably in a high position, possibly either side of the main bridge. Note: Another reference give the cruiser a top speed of 16 knots, two 200-lb and six 70-lb guns.

Propulsion

Information is scarce about it. There was a steam reciprocating engine, driving one shaft and single propeller, rated for 1900 ihp. Navypedia is diverging completely, stating there were two HC engines instead, fed by 6 cylindrical boilers. It is perhaps related to an hypothetic refit, or an error from one source. Both agrees about the ratings, 1,900 ihp. Whatever the case, top speed was noted as nine knots also. This could seems laughable for a cruiser especially today, but that that time the ship was considered as a glorified gunboat. Conway’s itself classifies the Pao Min not along the cruisers, but the gunboats and sloops, which is telling. Sources agrees the cruiser carried 300-360 tons of coal. Range was estimated 3360 nautical miles at 10 knots. Complement was 200 men.

Active service of the Pao Min: 1884-1903

The Chinese cruiser was completed in October 1884 too late to be thrown in to the furnace of the Sino-French war. She was part of the Nanyang Fleet (南洋水師), one of the four modernised provincial Chinese navies in the late Qing Dynasty (1870s). This feet was crippled during the Sino-French War. Later the remainder escaped intact in the Sino-Japanese War, but the Pao Min did not survived enough to see the fleet formally abolished in 1909. When the Pao Min entered service, the star of the fleet and only really ship feared by the French was the semi-experimental tiny ironclad called Jinou, made at Foochow.

Admiral Li Chengmou (李成謀), a veteran of the Fujian fleet and traditional Yangtze water forces commanded the fleet. He decided to stay safely in Shanghai and Nanking from August 1884. They were closely watched at a distance from July 1884 by the French ironclad Triomphante, which maintained de facto a “blocus”. Pao Min was still fitting-out in Shanghai during the war. French Admiral Amédée Courbet asked to lead an attack, which was denied by PM Jules Ferry. The ironclad therefore departed with the cruiser d’Estaing for the Min River, concentrating the squadron for an attack against the Fujian Fleet and Foochow Navy Yard. The “blocus” was maintained by the cruiser Perceval which replaced both ships in station.

Courbet attack on the Fujian Fleet on 23 August 1884 (Battle of Fuzhou) was the starting point of the war. Therefore Admiral Li Chengmou decided to split the fleet to protected both Shanghai and the arsenal and Nankin. Staying at Shnaghai were the Longxiang, Feiting, Cedian and Huwei. The cruisers Nanrui and Nanchen, and other ships including the Pao Min sailed out for Nanking. French cruiser Perceval did not opposed them and departed in turn. In February 1885, trying to break the French blockade of Formosa the Chinese squadron suffered defeat in the Battle of Shipu while Kaiji, Nanrui, Nanchen, Chaowu, Yuankai were trapped and blockaded in Zhenhai Bay until the end of the war. Pao Min was delivered as the war ended.

Operational records are not known directly, she is only mentioned a few times and her known fater is a hulk in 1903. Afterwards she could have survived many more years in this state, one source telling 1920 as her scrapping date. Entering service shortly after the war ended, she somewhat compensated in the declining Nanyang fleet for the losses of the Yuyuan and Chengqing soon joined by the Foochow built composite cruisers Jingqing and Huantai in 1886-87.

Interwar years (before 1894) did not saw much as actions or records, and the Baomin, now a third-rank cruiser, was assigned to the Chinese Nanyang gunboat fleet and acted the same way. The Beiyang Fleet was rebuilt in the end of the 1890s with five brand new steel cruisers made in British & German shipyards. These were second rank protected cruisers but nevertheless, this placed China on the level of the Chilean Navy, certainly at thet time the elite naval power of South America.

Nanyang fleet’s Frigate Dengyingzhou in construction

In 1894 during the first Sino-Japanese war, the Pao Min is absent from the Battle of Pungdo in July as only the Chinese cruiser Tsi-yuan and gunboat Kwang-yi are mentioned, plus the transport Kow-shing. During the Battle of the Yalu River (1894), the Paomin was not involved as this affair concerned the Beiyang fleet. Record after the battle are not known either and the ship is supposed to have been hulked in 1910, but probably existed as a hul in WW1. All in all, the Pao Min is just anecdotical in the Chinese naval history, missing two wars, but she was important nevertheless as one of the first domestically-built Chinese cruisers, in what is now probably the largest PLAN shipyard and arsenal.

Specifications

Specifications* |

|

| Dimensions | 64.92 m x 10.97 m x 4.27 m draft (213 x 36 x 14 ft). |

| Displacement | 1,480 tonnes standard -approx. 1,590 tonnes Fully Loaded |

| Crew | 200 |

| Propulsion | 1 shaft reciprocating, 2 boilers, 1900 ihp. |

| Speed | Top speed 9 knots, 3000? nm range, about 300 tons coal. |

| Armament | 2 x 249 mm (5.9 in), 6 x 120 mm (5 in), 2 x 47 mm QF (3 pdr). |

| Armor | None. |

Src/Read More

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nanyang_Fleet

https://www.worldnavalships.com/chinese_navy.htm

http://oceania.pbworks.com/w/page/8450927/Chinese%20Cruisers

http://www.navypedia.org/ships/china/ch_cr_pao_min.htm

https://enacademic.com/dic.nsf/enwiki/5204442

https://www.quora.com/Why-did-China-have-no-fleet-after-the-Beiyang-fleet-s-destruction

http://docshare03.docshare.tips/files/26364/263644851.pdf

Google Books the Sino Japanese wars 1894-95

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Naval_ships_of_Qing_China

https://fr.scribd.com/document/263644851/Nanyang-Fleet

Arlington, L. C., Through the Dragon’s Eyes (London, 1931)

Duboc, E., Trente cinq mois de campagne en Chine, au Tonkin (Paris, 1899)

Loir, M., L’escadre de l’amiral Courbet (Paris, 1886)

Lung Chang [龍章], Yueh-nan yu Chung-fa chan-cheng [越南與中法戰爭, Vietnam and the Sino-French War] (Taipei, 1993)

Rawlinson, J., China’s Struggle for Naval Development, 1839–1895 (Harvard, 1967)

Wright, R., The Chinese Steam Navy, 1862–1945 (London, 2001)

https://wikivisually.com/wiki/Battle_of_Zhenhai

https://wikivisually.com/wiki/Battle_of_Shipu

https://wikivisually.com/wiki/Sino-French_War

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign