France (1894-1900)

France (1894-1900)Charlemagne, Saint Louis, Gaulois

WW1 French Battleships:

Duperre class | Terrible class | Amiral Baudin class | Hoche | Marceau class | Charles Martel class (1891) | Charlemagne class | Henri IV | Iena | Suffren | Republique class | Liberté class | Danton class | Courbet class | Bretagne class | Normandie class | Lyon classThe Charlemagne class Battleships were three French “pre-dreadnoughts” ordered in 1894 over a new design, in an attempt to rationalize and standardize capital ships in France. Charlemagne, Saint Louis, Gaulois were originally intended for the Atlantic but were soon in service in the Mediterranean, taking part notably during WWI in the Dardanelles Campaign, one being sunk by an U-Boat.

First step out of the Young School

One of the crucial change for the French Navy at the end of the century, was to start seeing some of the Young School (jeune école) theories with growing suspicion. France after the 1870 defeat and regime change, decided to reaffect budget towards its army, cutting down massively on naval spendings, and concentrating on coastal defence and armored cruisers, to wage an asymetric warfare on the global stage, mostly looking at the Royal Navy.

However after 1895, emerging Navies like those of Italy, Germany or Japan were contesting the old rivalry and forcing France started to look at a more conventional path, if war was to break out with these.

One point always brought forward in 1893 already was the great diversity of designs tested by the French Navy, lack of homogeneity and long contruction time. This plagued all previous battleships, obsolete when commissioned, like those of the Charles Martel, as well as some constestation on odd design choices, like single turrets and wings guns, or the typical pear-shape hull design (tumblehome) which proved not so ideal in rough seas as it was discovered.

Some of these complaints made their way into a new design ordered in 1894 of three Battleships based on the same, more advanced design, two of which were built in Brest and one in Lorient, with a strict specification and timetable respect.

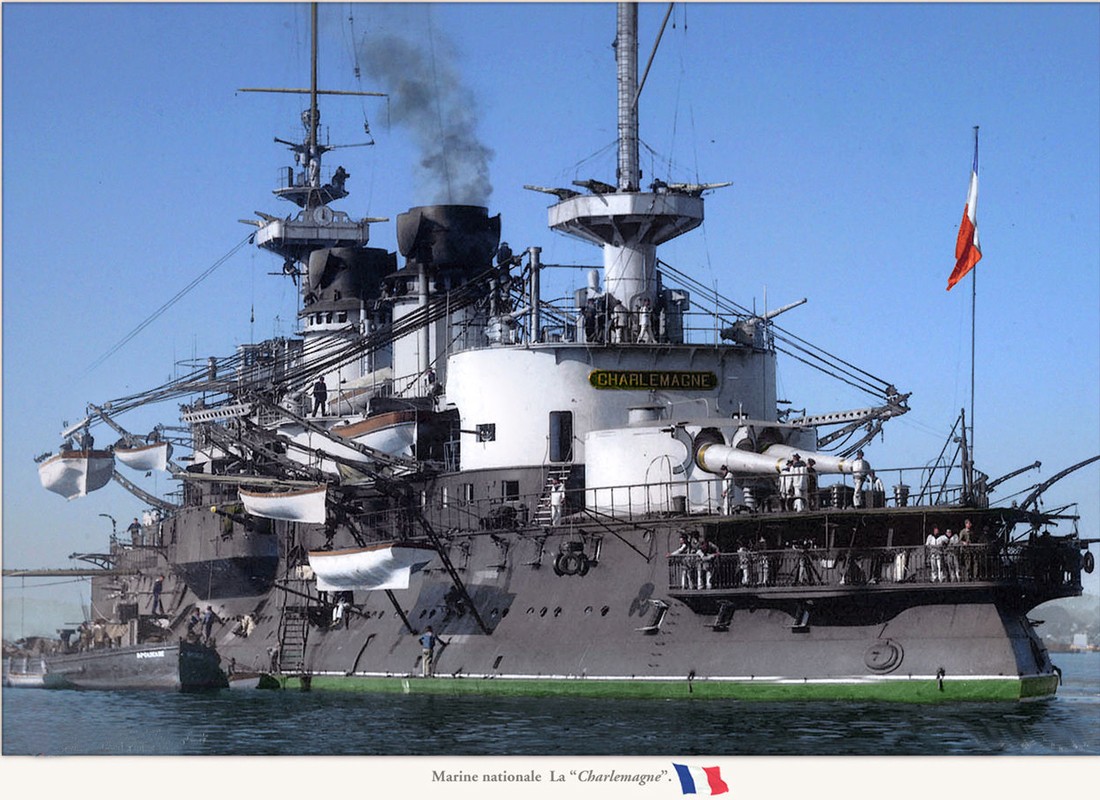

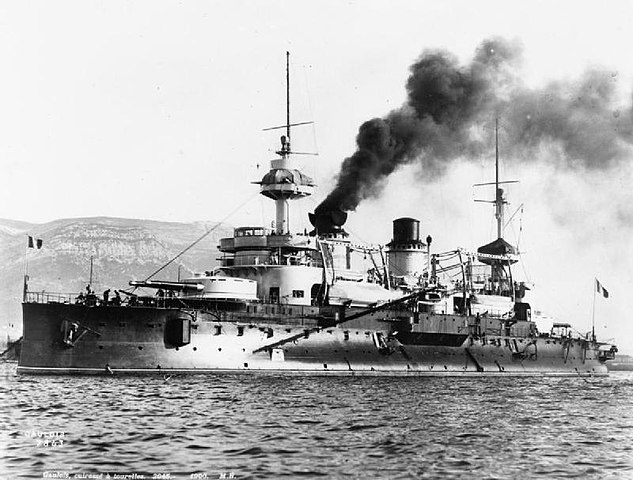

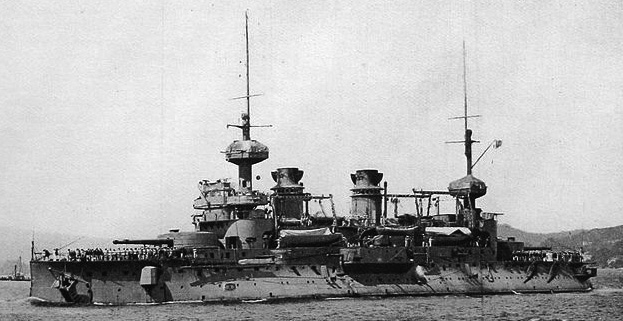

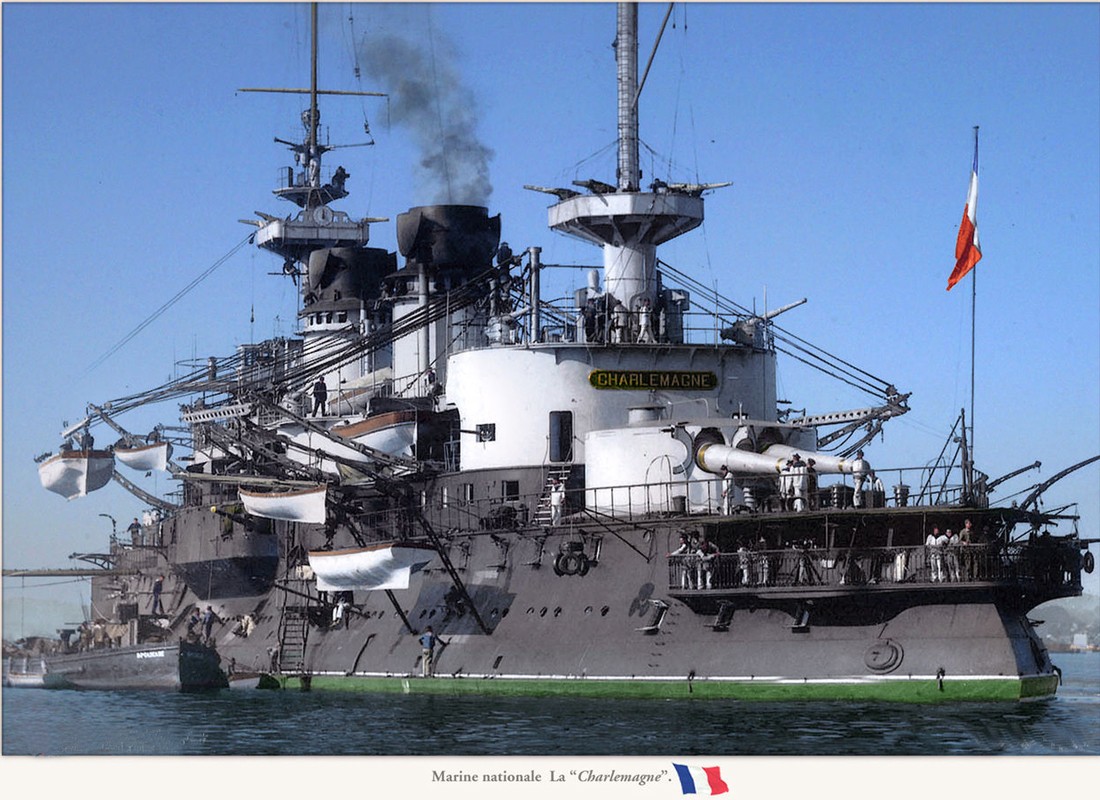

Charlemagne, colorized by Irootoko Jr.

In the end, this procured three sister-ships that were a more coherent class, with general better characteristics, more conventional approach for artillery, hull construction, better armour scheme, and better speed. Intended at first for the Atlantic, they did not fare well in heavy weather and made their career in the Mediterranean instead, being quite active in WWI in this theater in which all three took part to the Gallipoli campaign, Gaulois being sunk by UB 47 in December 1916.

Despite they were faster built, and more coherent, these new battleships still entered service in 1900, being obsolete as their general design went back to 1893. They were followed by the single Iéna and Suffren, spin-off of their class in 1902-1904, before the old design ways were completely abandoned, leading to the brand new République-class battleships and the great fleet reforms that preceded WWI.

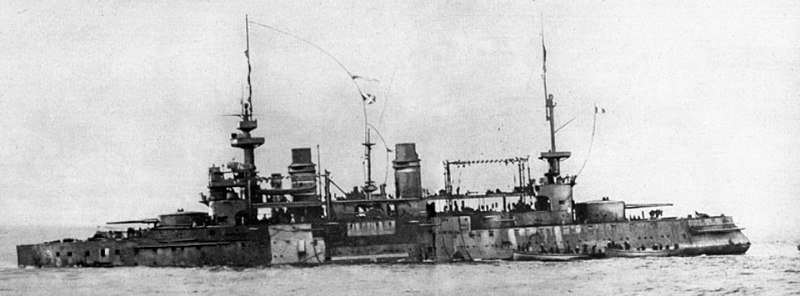

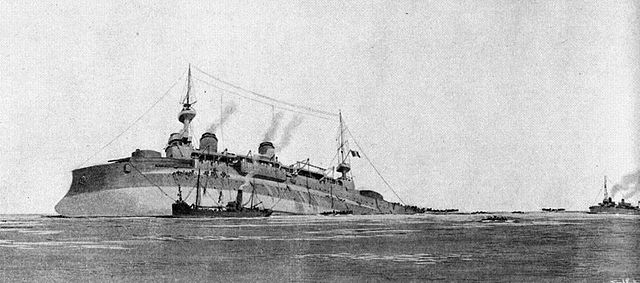

Charlemagne’s class predecessor, the Charles Martel class, showing all what was wrong with French capital ships under the Young School doctrine (colorized by Irootoko Jr).

Design in Details

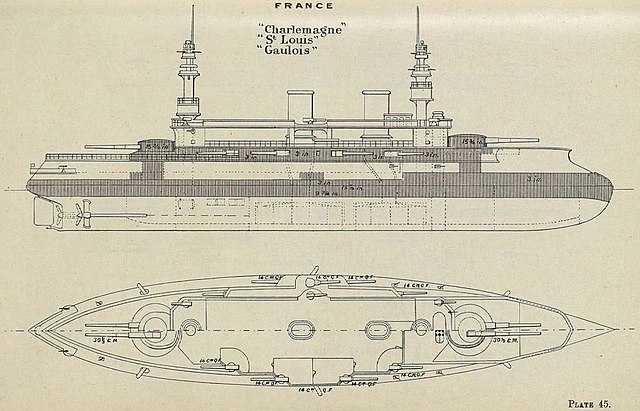

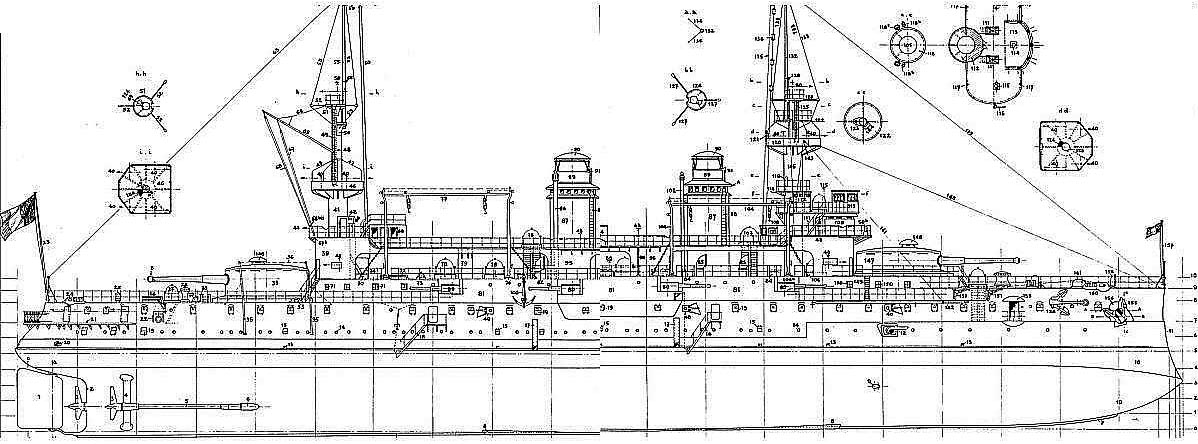

Brasseys diagram of the class in 1896

The Charlemagne were an interesting mix between old and new habits. The “old” was paradoxically an inheritance of the young school experiments, but toned down: They were still characterized by a massive tumblehome, ram bow, and heavy military masts. But at the same time they opted for the more standard fore & aft twin turrets approach. Secondary armament was a bit weak, with just five 14 cm (5.5 in) guns in casemates per side, speed was the same as before and not impressive compared to Italian designs of the time, and armor had a weak spot where the tumblehome slope was located. The struct enforcement of specifications to the yards and avoidance to revise the design also helped a faster construction, of six years (Charlemagne) to four (Gaulois), and the choice of Atlantic coast yards played its part.

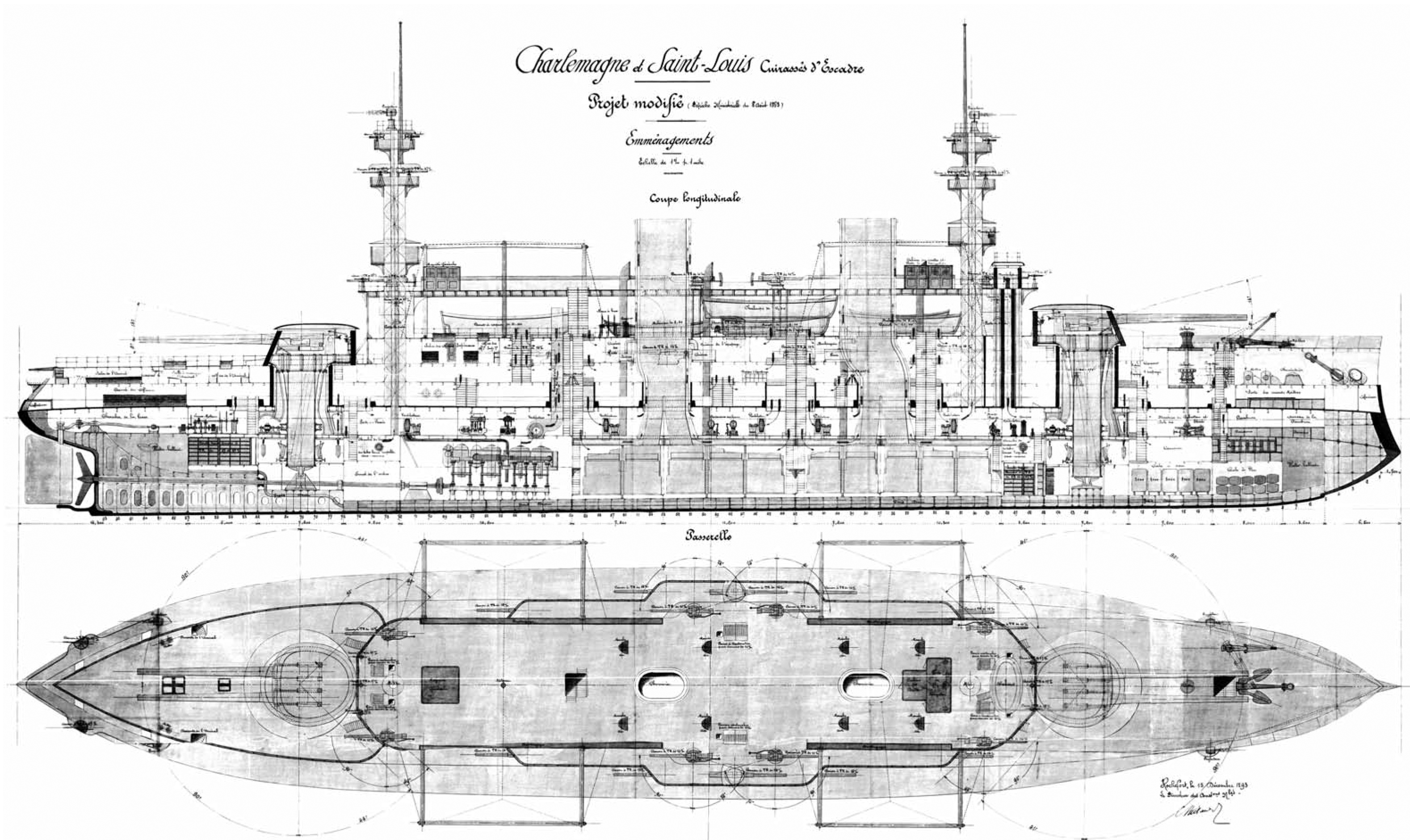

Original plans cutouts profile and deck

Decks plans elevations Original

Hull construction

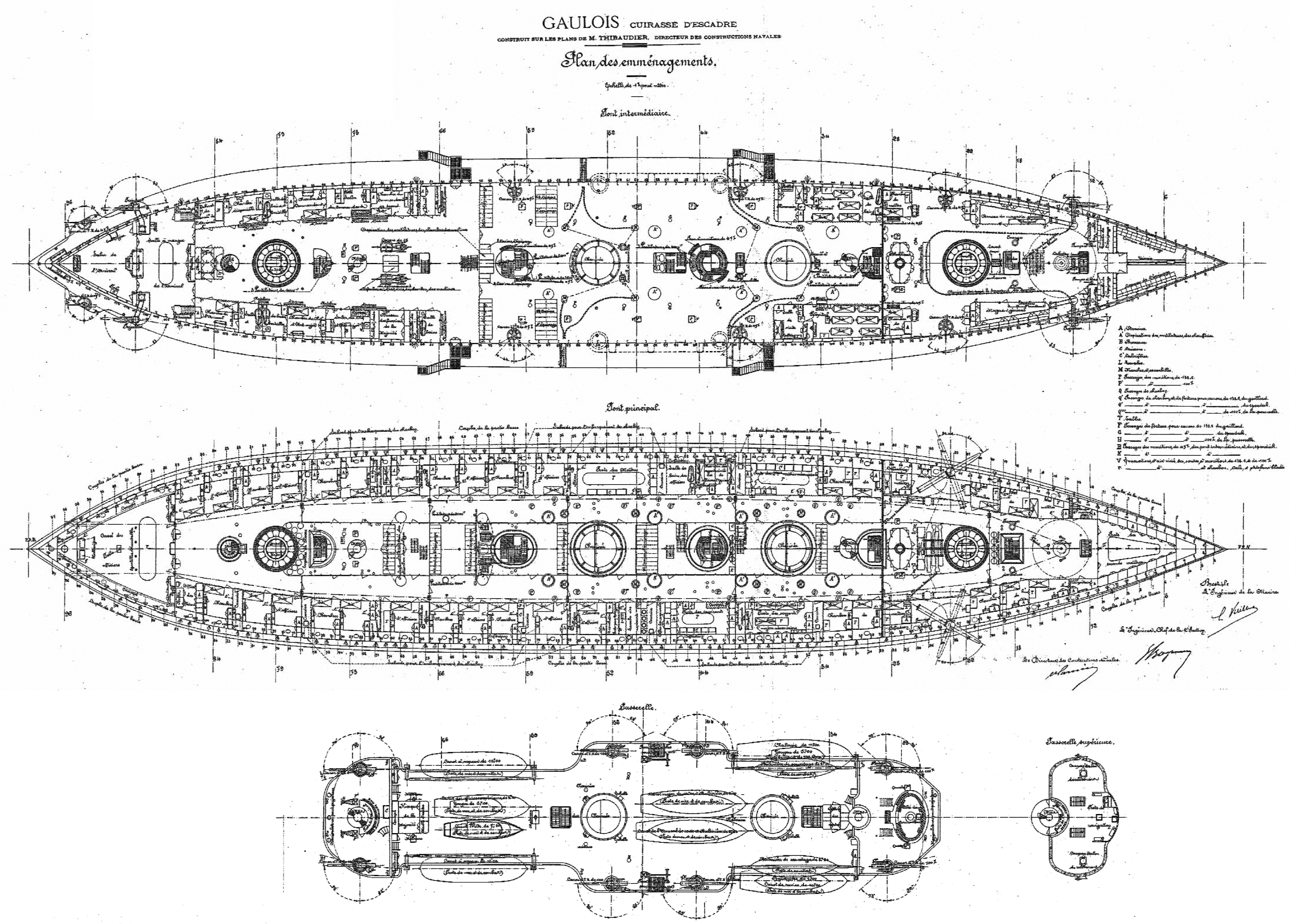

Symonds and Co Collection, Q22279 Gaulois

The Charlemagne-class battleships were small in 1900 standards: They measured 117.7 metres (386 ft 2 in) long overall, for 20.3 metres (66 ft 7 in) in beam, and deeply loaded, reached 7.4 metres (24 ft 3 in) in draught forward, up to 8.4 metres (27 ft 7 in) aft for a displacement of 11,275 tonnes (11,097 long tons) deeply loaded, which was also weak. The contemporary Majestic class (1895) reached 16,000 tonnes and the Italian Sardegna class (capable of 20.3 kts also) 15,000 tons FL.

The general design was still very much in line with previous French pre-dreadnoughts, with the typical tumblehome, still pronounced, a tall, rounded hull, small usable deck surface, conning tower and small bridge forward, towering above the forward main turret, flying bridge running along the amidship section to the aft bridge (with service boats under davits alongside), two heavy military masts with three levels, where the light guns and projectors were located, and the artillery spotters lookouts. As previous designs also, the very long ram bow was substracted from the utility deck lenght, so that the forward and aft turrets were very close to both deck ens of the ship, with little buoyancy reserve. Due to this, both this and their metacentric height resulted in poor behaviour at sea:

The Charlemagne-class ships indeed were poor seaboats in heavy seas, as shown by initial tests in stormy weather in the Bay of Biscay, in 1900. The Gaulois’s captain reported that his ship’s forward gun turret and casemates were flooded out, while his vessel was ploughing heavily, raisiong so much spray it even washed over the bridge, and the deck was flooded at each wave, water systematically going over the bow. However he also observed when the weather was good, his hip made for a steady gunnery platform, manoeuvering well and having a predictable roll. He however was very critical of the armour layout, not being high enough above the waterline, rightfully so.

The crew of all three ships consisted of 727 officers and enlisted men, but they were also outfitted as flagship and in that case, carried 41 officers and 744 sailors.

Protection

The armour scheme was seemed at the time as an improvement over previous experiments, but left much to be desired: They carried 820.7 tonnes (807.7 long tons) of Harvey armour, quality compensating for quantity, but it was a bit light. By thickness figures, the main belt and turrets were well protected, but the general scheme left the entire section above the armor deck and up to the casemate deck unprotected. The sloped section was not sufficient to stop modern AP shells.

As for ASW compartimentation, no special care has been made to adequately separate the machinery room VTE and boilers, but a single layer of compartimented sections behind the belt, and no longitudinal bulkhead. There was no particular innovation in this field compared to previous designs, which was paid dearly by a submarine kill in 1916. Details were as follows:

- Waterline Belt 400 mm (15.7 in) thick over 3.26 metres (10 ft 8 in) high

- Belt tapered down to 110 mm (4.3 in) at its lower edge

- Armoured deck 55 mm (2.2 in) thick, flat section

- Deck slope to the belt 35 mm (1.4 in), angled downwards

- Main turrets 320 mm (12.6 in), roof 50 mm (2.0 in)

- Main turrets barbettes 270 mm (10.6 in)

- Casemates outer walls 55 mm (2.2 in)

- Transverse bulkheads 150 mm (5.9 in)

- Conning tower 326 mm (12.8 in), roof 50 mm

- CT communication tube 200 mm (7.9 in)

Powerplant

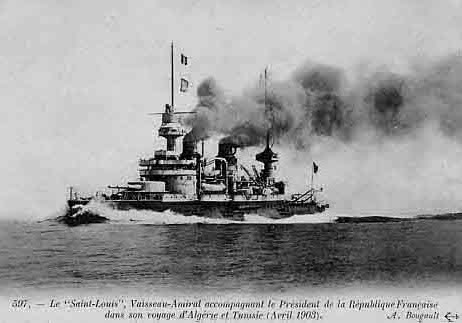

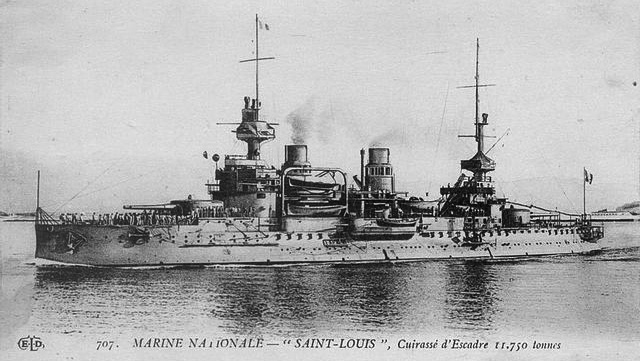

Saint Louis underway

The three vessels had construction specification quite strict between them, all equipped with 4-cylinder vertical triple-expansion steam engines (VTE), driving each a 4.3-metre (14 ft 1 in) propeller. Steam was provided by 20 Belleville water-tube boilers working at 17 kg/cm2 (1,667 kPa; 242 psi). Total output was rated to 14,500 metric horsepower (10,700 kW). On sea trials they produced with forced heating up to 14,220–15,295 metric horsepower (10,459–11,249 kW). Top speed was 18 knots as designed, but up to 18.5 knots (34.3 km/h or 21.3 mph) was reached on trials. 1,050 tonnes (1,030 long tons) of coal was stored onboard, enabling a range of 4,200 miles (3,600 nmi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph).

Armament

Main: 2×2 12-in/40 Modèle 1893/96 guns

The Charlemagne class made quite a rupture with previous designs (Charles Martel class) by having a more uniform armament in twin turrets fore and aft while earlier ships spread two 305 mm/45 Modèle 1893 guns in single turrets fore and aft, and two 274 mm/45 Modèle 1893 guns on the wings.

The four 40-calibre “Canon de 305 mm” Modèle 1893 were a first in the French Navy in this configuration, but forcing to adopt a common, solidary mount. The latter was rotated by electric motors while the guns were still hand-cranked for elevate and depression, respectively of -5° to +15°.

Loading position was fully depressed only. They had a ready rack with 10 shells before a new call to the magazine was necessary, helping for a “greater” rate of fire (1.3 minutes). They fired a 349.4-kilogram (770 lb) armour-piercing shell at at 815 m/s (2,670 ft/s), with a range of 12,900 metres (14,100 yd). 45 shells were provided for each gun, 180 total on board.

Secondary: 10x 4.5-in/45 Modèle 1893 casemate guns

From eight to ten 45-calibre Canon de 138.6 mm (5.5 in) for the previous vessels, was explained by having eight (four per side) in individual casemates along the amidship battery and two in shielded mounts, on the forecastle deck. Depression/Elevation was -5°30″ and +19°30″. They fired a 35 kgs (77 lb) armour-piercing shell at 4 rpm and 730 m/s (2,400 ft/s), with a range of 11,000 metres (12,000 yd) at maximum elevation. Total storage onboard amounted to 2316 rounds.

Tertiary: 8x 4-in/45 Modèle 1893 shielded guns

Complementary, eight “Canon de 100 mm (3.9 in) Modèle 1893” were all placed in shielded mounts on the superstructure. Depression/elevation was -10° to +20°, they fired a 16 kgs. (35 lb) shell at 5 rpm, 710 m/s (2,300 ft/s) and 10,000 metres (11,000 yd) range. Provision was 2288 rounds (286 per gun)

Light artillery: 20x 47 mm/40 Hotchkiss

To deal with torpedo boats, they also had twenty “Canon de 47 mm (1.9 in) Modèle 1885” Hotchkiss, eight located on fighting tops on both masts, four in the superstructure, and the rest in hull casemates. Depressio/elevation was -21° +24°. They fired a 1.5 kgs (3.3 lb) shell at 650 m/s (2,100 ft/s), with 12 rpm, and max range of 4,000 metres (4,400 yd). In total, the battleships carried 10,500 rounds.

Torpedo armament: 4x 450 mm

Four 450-millimetre (17.7 in) torpedo tubes were mounted in the broadside, two submerged and angled 20° from axis the others above the waterline, 90°. The ships carried for them twelve Modèle 1892 torpedoes, sporting a 75 kgs (165 lb) warhead, max range of just 800 metres (870 yd) at 27.5 knots (50.9 km/h; 31.6 mph). In 1906 the above water tubes were removed adnd plated over.

Old author’s illustration of the Charlemagne in 1914.

Old author’s illustration of the Gaulois in 1915.

Charlemagne class Specifications |

|

| Dimensions | 117.81 x 21.39 x 8.38 m (386.5 ft x 70.2 ft x 27.5 ft) |

| Displacement | 12,007 t (11,817 long, 13,235 short tons) |

| Crew | 710 wartime |

| Propulsion | 3 TE steam engines, 32 Belleville boilers for 15,000 ihp (11,000 kW) |

| Speed | 18 kn (33 km/h; 21 mph) |

| Range | 8,870 nmi (16,430 km, 10,210 mi) 19 knots (35 km/h, 22 mph) |

| Armament | 2 × 305 mm/45, 2 × 274mm/45, 8 × 138mm/45, 8 × 100 mm, 12 × 3-pdr, 2 × 450 mm (18 in) TTs |

| Armor | Belt: 460 mm (18 in), Turrets: 380 mm (15 in), Conning tower: 305 mm (12.0 in) |

Sources/Read More

Books

d’Ausson, Enseigne de Vaisseau de la Loge (1978). “French Battleship St. Louis”. F. P. D. S. Newsletter. VI

Caresse, Philippe (2012). “The Battleship Gaulois”. In Jordan, John (ed.). Warship 2012. Conway.

Chesneau, Roger & Kolesnik, Eugene M., eds. (1979). Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships 1860–1905.

Corbett, Julian (1997). Naval Operations. History of the Great War: Based on Official Documents. Vol. II

Friedman, Norman (2011). Naval Weapons of World War One: Guns, Torpedoes, Mines and ASW Weapons of All Nations

Gille, Eric (1999). Cent ans de cuirassés français [A Century of French Battleships] (in French). Marines édition.

Jordan, John & Caresse, Philippe (2017). French Battleships of World War One. Naval Institute Press.

Silverstone, Paul H. (1984). Directory of the World’s Capital Ships. New York: Hippocrene Books.

Links

Cuirassé Charlemagne (photo marius bar)

On navypedia.org

Last campaign of Gaulois on JSTOR

Gaulois Dardanelles forum.pages14-18.com

memorial-national-des-marins.fr/

On laroyale-modelisme.net

On avions-bateaux.com

On forum.pages14-18.com

On fr-academic.com

On le.fantasque.free.fr

wiki

Model Kits

1/1250 model worthpoint

On modeliste27.com

Cratchbuilt model

Armo 1/700 700-32 Gaulois Charlemagne-class

Charlemagne

Charlemagne

Charlemagne in 1914-15 (in grey camouflage)

Charlemagne (after the first Holy Roman Emperor), was authorised on 30 September 1895 as lead ship ship of class, laid down at the Arsenal de Brest, on 2 August 1894 launched on 17 October 1895, completed on 12 September 1899, which was still six years, but this was much improved for the second laid down two years after her, Gaulois, completed earlier actually, in January.

Charlemagne was assigned at first to the Northern Squadron base din Brest with Gaulois, but due to their problems with heavy weather, they were transferred to the 1st Battleship Division, Mediterranean Squadron, in January 1900. On 18 July 1900 she took part in combined manoeuvres with the Northern Squadron and a naval review hosted by the President of France, Émile Loubet in Cherbourg, Atlantic coast. She escorted the Minister of War and Minister of Marine on a tour of Corsica and Tunisia in October 1900 and took part in 1901 in an international naval review in Toulon, with ships from Spain, Italy and Russia.

In October 1901, the 1st Battleship Division (Rear Admiral Leonce Caillard) sailed to Mytilene, landing two companies of marines to occupy the island on 7 November in retaliation of Sultan Abdul Hamid II failing to honoroung contracts made with French companies and French banks loans. The 1st Division departed Lesbos afterwards for Toulon. In January–March 1902, Charlemagne wasn sent to Morocco to participate to the summer fleet exercises and allegedly collided with Gaulois on 2 March 1903, with little damage.

In April 1904, she took part in the escort of President Loubet in a state visit to Italy, followed after her return to the annual fleet manoeuvers of the summer. During a gunnery drill, a 100 mm cartridge spontaneously ignited in a magazine, in January 1905, but damage was well controlled. She sailed with the destroyer Dard, in an international squadron occupying Mytilene in November–December 1905. Thos was followed by another naval review by President Armand Fallières, in September 1906, followed by the summer naval manoeuvres in 1907. In September 1908 she was transferred to the 4th division.

Charlemagne wans sent for a time in the Northern Squadron, in October 1909. Underway north, she visited Oran, Cadiz, Lisbon and Quiberon. She was overhauled in Brest in January 1910. This was followed by a large naval review hosted by President Fallières off Cap Brun, 4 September 1911. Placed in reserve in Brest (September 1912) she was due for her major overhaul. When ot was over she experienced in a gale a 34° roll during her sea trials, in May 1913. Assigned to the training squadron of the Mediterranean Fleet, she headed south, andwas there from August 1913 until August 1914.

Charlemagne escorted Allied troop convoys at first, from North Africa, until November 1914. Like the rest of the French squadron she was ordered to the Dardanelles, in order to guard against a sortie by Goeben, refugee in Istambul. She took part later in the Gallipoli campaig, firing on 25 February 1915 on the fort at Kum Kale. On 18 March with Bouvet, Suffren, and Gaulois she made a first attempt to penetrate the Dardanelles, following six British battleships, in order to destroy Turkish fortifications further north-east.

Ordered to be relieved by six other British battleships, they went through a minefield laid during the night: Bouvet struck a mine, sinking quickly, Gaulois hit two but survived, escorted by Charlemagne to Rabbit Islands, north of Tenedos. There, she was beached and Charlemagne retired too for repairs, damaged during the bombardment, to Bizerte. This went on until May 1915, after which she returned.

Back to the “escadre des Dardanelles” she was ordered to bombard Turkish positions in support of the first Allied landings. Transferred to Salonica in October 1915 they joined the French squadron there to guard againsta possible intervention of the Greeks. Charlemagne was relieved and sent for a major refit in Bizerte, in May 1916, until August. Back to Salonica she was later assigned to the Eastern Naval Division or “division navale d’Orient”, until August 1917. Proceeding back to Toulon, she was placed in reserve on 17 September, disarmed on 1 November, stricken and disarmed from 21 June 1920, sold for BU in 1923.

Saint Louis

Saint Louis

St Louis engraving, 1914, ELD coll.

Saint Louis (named after King Louis IX), was authorised on 30 September 1895, laid down at Arsenal de Lorient, 25 March 1895, launched on 2 September 1896, commissioned on 1 September 1900 after her sea trials. total cost was 26,981,000 francs. Before commission she participated in a naval review honoring President Emile Loubet at Cherbourg, July 1900.

She was soon assigned to the Mediterranean Squadron, based on Toulon from 24 September, squadron flagship on 1 October, and until 24 February 1904. She transported Louis André (Minister of War) and Jean de Lanessan (Minister of Marine) on a tour of Corsica and Tunisia and in 1905 she participated to yet another international naval review, also held by President Loubet, in Toulon.

On 25 June 1903 she hosted King Alfonso XIII of Spain during a visit to Cartagena after escorting President Loubet to Italy. Saint Louis visited Morocco in December 1906 as tensions rose in the region, and became flagship of the Second Battleship Division from 18 March, then flagship of the 4th Division, from 17 April 1908. She was a brief appareance in the Northern Squadron as flagship in October 1910, taking part in a large naval review with President Armand Fallières in attendance, off Cap Brun on 4 September 1911. However soon after she collided with the destroyer Poignard off Hyères, relieved on 11 November for repairs, which transofmed into a full overhaul at Cherbourg, complete in April 1912. She returned as squadron flagship on 15 April 1912.

In June 1912 she collided yet again with the submarine Vendémiaire, rammed and sank on 8 Junen in the English Channel, off the Casquets. The submersible and crew went down without survivors. Saint Louis was transferred to the Mediterranean Squadron again in late 1912, being based in Toulon from 9 November as flagship, Second Division, Third Squadron, from 18 March 1913. Later she was part of the Supplementary Division as flagship from 10 February 1914.

As war broke out, she escorted troop convoys from North Africa to France and on 23 September 1914 sh sailed to Port Said, escorting a British convoy carrying troops from India. In November she was ordered to the Dardanelles, as part of the guarding fleet in case the battlecruiser Goeben would break out, until January 1915. After a brief refit at Bizerte she sailed for the Eastern Mediterranean, flagship of the Syrian Squadron from 9 February 1915. This unit was supposed to prey on Turkish positions and lines of communication between the Syrian, Lebanese, Palestinian coast, down to the Sinai Peninsula. Saint Louis notably shelled Gaza and El Arish in April 1915, before headed to the Dardanelles in May 1915.

There, she was used to bombard Turkish positions, in support of Allied landings. She even became flagship of the French Dardanelles Squadron on 26 August. She was relieved for her wartime overhault at Lorient, departing in October 1915, and was back in May 1916, but as operations ceased in the Dardanelles, she was ordered instead to Salonica as part of the French deterrence fleet towards the Greeks, from 22 May. She was flagship of the Eastern Naval Division (“division navale d’Orient”) from 26 October 1916, until refitted in Bizerte in February 1917, placed in reserve in April there and in January 1919 she headed bacl to Toulon for deactivation.

Saint Louis was decommissioned on 8 February, becoming a disarmed training ship for stokers and engineers, in Toulon. Condemned on 20 June 1920, she became an accommodation hulk, and listed for sale on 29 June 1931, purchased in May 1933 for 600,230 francs, to be scrapped.

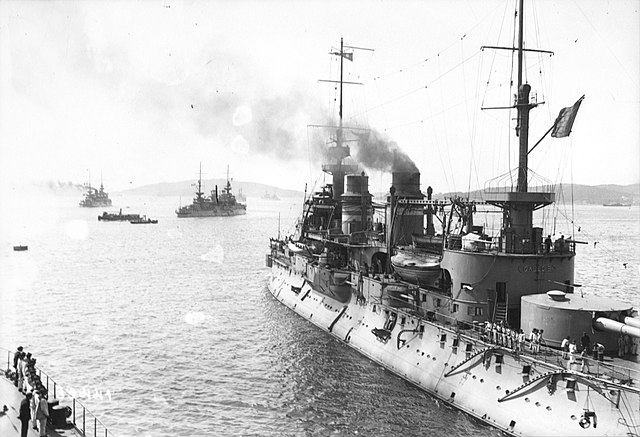

Gaulois

Gaulois

Gaulois in Toulon, Agence Rol Coll.

Gaulois (“Gaul”), was ordered on 22 January 1895 at Brest Arsenal, her construction delayed by the completion of Charlemagne until launch, and she was laid down on 6 January 1896, launched on 6 October, commissioned on 15 January 1899, assigned to Northern Squadron, but then 1st Battleship Division, Mediterranean Squadron on 30 September.

Both her and Charlemagne were scheduled to sail from Brest on 18 January 1900, and reached Toulon later. In Hyères, Gaulois accidentally rammed the destroyer Hallebarde, which survived and reached Toulon to be repaired. No damage was reported for Gaulois, which on 18 July, after combined manoeuvres with the Northern Squadron, took part in a naval review for Émile Loubet at Cherbourg, followed by an international naval review in Toulon. In October 1901, the 1st Battleship Division (Rear-Admiral Leonce Caillard) sailed to Mytilene, Lesbos, by then possessed by the Ottoman Empire. The battleship carried and landed companies of marines occupying the island on 7 November, forcing Sultan Abdul Hamid II paying his Empire’s debts to French Banks.

The 1st Division departed Lesbos in December back to Toulon and in May 1902, Gaulois became flagship, Vice-Admiral François Fournier sent in the US for her staff to assist the unveiling of a statue of Comte de Rochambeau, in Lafayette Square, Washington, D.C. President Theodore Roosevelt visited Gaulois and her crew was invited in New York City and Boston. While back, the battlesip also paid goowill visits to Lisbon and entered Toulon harbor on 14 June 1902.

Exercises off Golfe-Juan (31 January 1903) saw Gaulois hitting Bouvet during manoeuvers. Bouvert suffered little but Gaulois had two armour plates in her bow lost. Both captains were however relieved of their commands and Pierre Le Bris took command on 20 March. By April 1904 she escorted the president Loubet to Italy. She visited also Thessaloniki, Athens, and tested a wireless telegraph in December 1905. With Iéna and Bouvet, she took upt survivors of the April 1906 eruption of Mount Vesuvius in Naples. On 16 September 19106, she took part in another international naval review held in Marseilles.

Until the war broke out she went on in her routine of exercises with the Mediterranean Squadron, visiting port in the Empire. In January 1907, she was now in the 2nd Battleship Division, then 4th Battleship Division (July 1908), on 5 January 1909, 2nd Battle Squadron. The strongpoint of her gunnery drills had been the sinking of the target ship Tempête on 18 March. On 5 January 1910 she was now in the 1st Division, 2nd Battle Squadron transferred to Brest, replacing the Northern Squadron in late February. While there, one of her torpedoes was accidentally launched and colided with the the destroyer Fanion while training.

On 1 August 1911, the 2nd Battle Squadron became the 3rd Battle Squadron and she later took part in a residential naval review. She returned to the Mediterranean Squadron on 16 October 1912, and after another naval review for Pdt. Raymond Poincaré on the 10th, her unit was soon dissolved and she was reaffected to the “Complementary Division” with Bouvet and Saint Louis. In June 1914, Gaulois was to be sent to the Training Division of the Squadron but war broke out.

After escorting convoys she ws sent to Tenedos Island guarding against a possible sortie of Yavuz Sultan Selim, in place of Suffren. Gaulois was flagship, Rear-Admiral Émile Guépratte from 15 November, until 10 January 1915. On 19 February she bombarded Turkish Forts with Suffren at the mouht of the Dardanelles, notably Orhaniye Tepe. While on mission on 25 February, anchored some 6,000 metres (6,600 yd) away from the Asiatic shore, she engaged Kum Kale and Cape Helles, was replied, but moved closer to finish off the forts, down to 3,000 metres (3,300 yd) for the shore, having her secondary armament to bark too. She was hit twice with moderte damage.

Le Gaulois, battle damage in 1915

On 2 March, she shelled targets in the Gulf of Saros and went on raining steel on more positions joined with British battleships. Gaulois was hit by a 150 mm (5.9 in) shell, which failed to detonate. Guépratte’s was back to the Gulf of Saros to resupply on 11 March, and returned shelling Ottoman fortifications. On 18 March British ships led the way in the entrance, the French ships passing through them to engage forts closer. Gaulois was hit agai, twice. Her quarterdeck was hit, as the waterline, starboard bow. Armour plates were torned below the waterline, with a 7 metres (23 ft) by 22 centimetres (8.7 in) gash causing flooding. It soon uncontrollable so that Captain André-Casimir Biard orderedto sail to Rabbit Islands north of Tenedos to beach her. Non-essential crewmen were ordered off, in case she sank on her trip. She eventually arrived and beached as planned.

Gaulois was patched until fully refloated, towed away on 22 March, repaired further until she could depart for Toulon, via Malta escorted by Suffren. They crossed a storm on 27 March off Cape Matapan, so that Gaulois’s patches started leaking under the pressure. She setn a wireless message for assistance, answered by the armoured cruiser Jules Ferry and three torpedo boats, helping her until she reached the Bay of Navarin for furher repairs, taking spare metal from the oldMarceau.

Gaulois arrived at last at Toulon on 16 April, entering drydock and overhauled at the occasions: Her heavy military masts were removed and replaced by simple poles, the superstructure lightened, the conning tower removed a s well as the battery roof’s secondary guns, two 100 mm and six 47 mm guns. She received anti-torpedo bulges, making her beamier. All these measures greatly benefited her stability. In June she was at sea again for further operations. Gaulois sailed back to the Dardanelles, arriving at lemnos on 17 June.

She dropped anchor 1,000 metres (1,100 yd) on 11 August off the coast, to pummel the Ottoman artillery battery of Achi Baba. She was hit in return, one putting fire her deck, quickly mastered; While underway back the decodedly unlucky battleship ran aground at the harbour entrance. This obliged all her ammunition and storages being unloaded before she could be towed away on 21 August. Sailing with République she covered the Allied evacuation in January 1916. Next she headed for Brest on 20 July for an overhaul, her captain insisting she needed an extra 4,000 metres artillery range to fit in a modern battleline and so the admiralty though ot disarming her entirely as a barrack ship.

Alas, after her refit, shortened, she was ordered back to the Eastern Mediterranean on 25 November, being off Crete on 27 December 1916. There, she was was torpedoed by UB-47n at 08:03. Her escorting torpedo boat Dard and two armed trawlers could do little to prevent the ambush, and chased off the submarine afterwards, before coming back to assist the sinking Gaulois. Hit abaft the mainmast, flooding became uncontrllable, killing two crewmen outright, drawing many more attempted to abandon her. She sank however slowly enough for the rest of the crew to be successfully rescued. She disappeared beneath the waves at 09:03, off Cape Maleas, where she still lays today as a war grave.

Gaulois sinking after UB-47 hit.

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign