Mining the Gulf of Finland

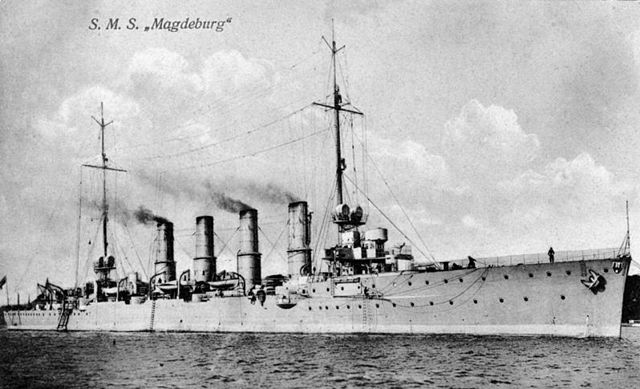

Odensholm (currently Osmussaar, desolate island of 4.7 kilometers belonging to Estonia – where according to legend, Odin was burned at his funeral) was located 67 km southwest of Tallinn (59°17′30″N 23°23′30″E). By its strategic location, it closed the Gulf of Finland, gateway to the Baltic from St Petersburg. Upon declaration of war, it was entrusted to the care of the Hochseeflotte to lay mines at the entrance to the Gulf. On 25 August, were designated for this the cruisers Magdeburg and Augsburg. The first sailed from Königsberg (now Kaliningrad) and rallied the entrance to the Gulf during the night of August, 26.

SMS Magdeburg, German light cruiser

Return of fate

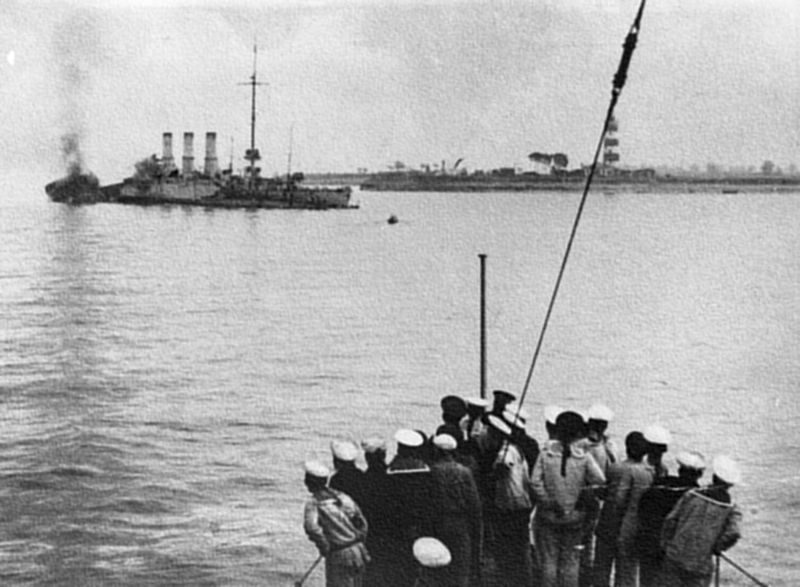

Unfortunately the weather was foggy, and the Magdeburg ran aground on shoals north of the island of Odensholm, at only 200 m from the lighthouse at midnight past 38 minutes, when the starboard forward hit sand where water was only 2.5 meters deep. Escorting destroyer V26 tried to take her in tow for digging out, but in vain. However, from the nearby island Lighthouse, as the weather cleared up in the first lights, the Russian watchman gave the alarm to the headquarters of the Baltic Fleet. The naval base of Tallinn was only 50 miles away. Situation was now critical and Lieutenant Commander Habenitch orders the crew to evacuate the ship and prepare for scuttling.

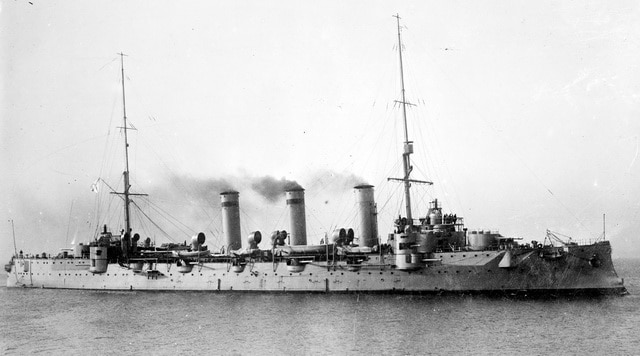

Russian cruiser Bogatyr

Engagement

Charges were laid, confidential archives are burned in a boiler. As the crew prepares to embark on the V26, a watchman signaled two Russians cruisers in sight. This was actually the Bogatyr, followed at a distance by the Pallada, that came through at 9.10 am. The V26 resumed abruptly boarding operations and left the area immediately, leaving the men left to their fate. The cruiser had not brought the colors yet, so the Russians cruisers opened fire in a blind spot: The German cruiser would not even have time or opportunity to replicate. After warning shots, seeing that the German cruiser failed to comply and bring the colors down, they shelled the ship at short range and quickly blown its superstructures up. A raging fire started, and the beginning of a panic seized the German crew. Moreover, charges at the front blown up at the same time, the back charges then being inactivated probably to left time to evacuate the ship. As a result, the ship essentially was left unscaved, as the Russians quickly stopped firing and sent a boarding party.

Stranded SMS Magdeburg being evacuated (seen probably from a Russian cruiser’s bridge), as the front part has been blown up. The lighthouse can be seen 200m in the background. (Bundesarchiv)

Aftermath

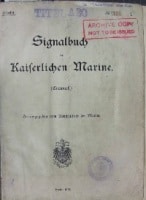

Ultimately, 56 sailors and Commander Richard Habenicht were captured, 17 dead, 21 wounded and 85 missing were declared. Captain Nepenin, chief of intelligence of the Baltic fleet sent a search team who to find a copy of the precious codes book of the Hochseeflotte, the Signalbuch der Kaiserlichen Marine (SKM), which was eventually discovered under a pile of clothes in the room of the commander. This document was indeed of paramount importance, giving precious intelligence to the allies.

Moreover two others were also found with their decoding manuals attached: The around maps (containing coded squares). Two of these copied code books were sent to the fleet of the Baltic and the Black Sea, and the third one sent to London by captains Kedrov and Smirnof that delivered these personally to Winston Churchill, then 1st Lord of the Admiralty. Discovered also were the 4977.73 Marks, maps with the registered German minefields and corresponding secret codes.

Moreover two others were also found with their decoding manuals attached: The around maps (containing coded squares). Two of these copied code books were sent to the fleet of the Baltic and the Black Sea, and the third one sent to London by captains Kedrov and Smirnof that delivered these personally to Winston Churchill, then 1st Lord of the Admiralty. Discovered also were the 4977.73 Marks, maps with the registered German minefields and corresponding secret codes.

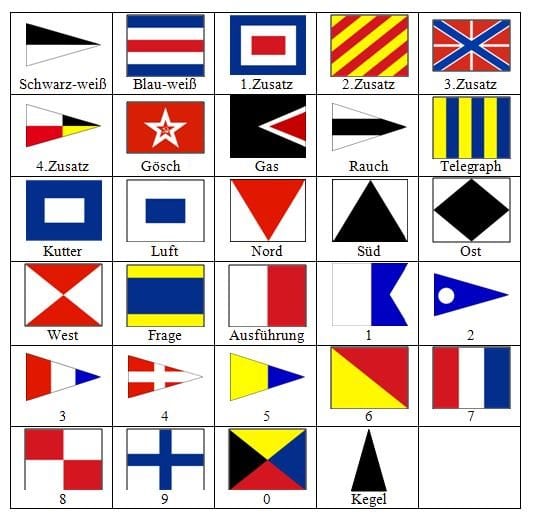

German signal flags.

These were immediately sent to the “Room 40” and intersected with other documents. From then on the Royal Navy and the Russian Navy will always have an edge over the Hochseeflotte. Indeed, the German staff ignored that the allies were now in possession of these ultra-secret documents, as the 56 men of the Magdeburg were held in Siberia until the capitulation. Moreover, in October 1914 the British also obtained the Imperial German Navy’s Handelsschiffsverkehrsbuch (HVB). This codebook was used by German naval warships, merchantmen, naval zeppelins and U-Boats. This case recalls another, which occur 19 years after: The seizing of enigma machines and breaking of the encryption code (which ultimately led to the invention of the computer).

Links & resources

Osmussar – Odensholm

German signal flags from 1815 (pdf)

The Code Bearers (Google book) By John Westwood

Das Ende von SMS Magdeburg

Room 40

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign