SMS Schwarzenberg was an Austrian Navy Frigate built in Venice in 1851-54 and sole in her class. She was a sail-only ship later converted to steam in 1862. She had an illustrious career, and saw significant action notably by leading the Austro-Prussian squadron at the 1864 Battle of Heligoland, part of the Second Schleswig War, and at the Battle of Lissa in the Third Italian War of Independence. A very long career as a TS from 1869 which saw her retired only in 1890.

Design

Hull and General Layout

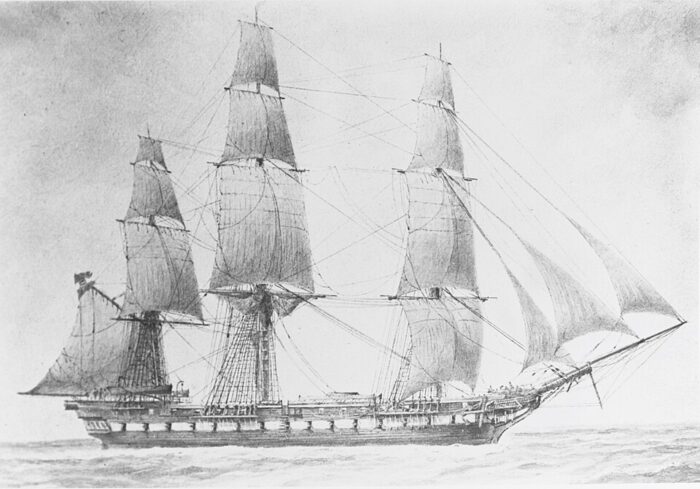

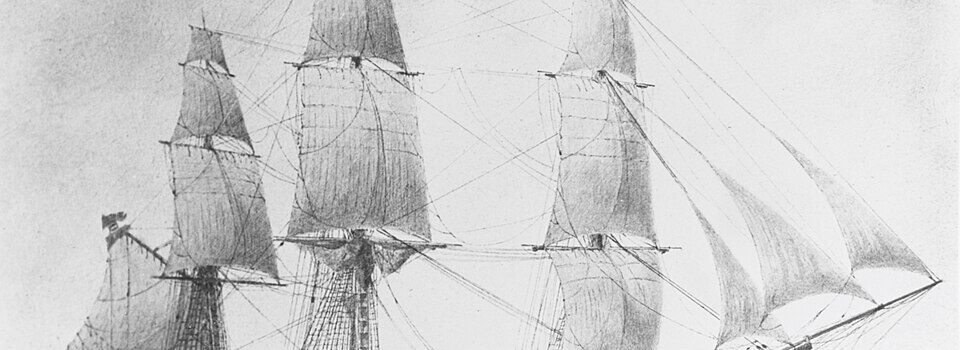

Schwarzenberg as completed as a sailing frigate in 1854

Schwarzenberg was a large, 1st rank frigate for its day, at 64.4 m (211 ft 3 in) long, between perpendiculars, and 74 m (242 ft 9 in) long overall at the bowsprint’s end. Her beam was 14.88 m (48 ft 10 in), for a draft of 6.5 m (21 ft 4 in). Her displacement was 2,614 long tons (2,656 t). She had a crew of 547 officers and enlisted sailors. Being a purely sailing ship, she was fitted with a three-masted ship rig. The latter was a complete four-stage model typical of the warships of the time, with three jibs, a spanker sail aft, taller mainmast and still generous foremast. The hull was designed with fine lines typical of the Venetian Arsenal and Yard, with a limited decorum, black hull and typical battery light band, then a relatively austere “castle” and officer’s quarters aft. Internal decoration however was everything but austere, with neo-baroque motives.

Still, as warships of old, all these could be dismounted and stored if general quarters was ordered. Extra panels were mounted to act as bulkheads in case of raking fire. For her generous crew of 557 men as a sailing frigate. After conversion as a screw frigate this was between 498 and 535 men, so significantly less, mostly due to fewer modern guns that did not required that much crew. Originally she had a typical gangway between the foremast and mainmast, with two large whalers installed. She had two yawls under davits further aft. After conversion to stem, the former gangway was now housing the powerplant’s upper structure and funnel and whalers and pinnaces were strapped under davits.

Sailing Rig and Powerplant

In 1862, Schwarzenberg was considered no longer relevant as a sail only frigate. The steam conversion craze was at its peak, and thus she was heavily modified for steam propulsion.

Although lobbyists strongly supported the paddle steamer concept, the “screw faction” won. The originally designed engine could not be delivered in Austria at such short notice, which lacked experience in large marine engines, so it was decided to hastily purchase one from England. The problem was that this engine was designed for a ships 500 tons lighter, one reason why steam Frigates built in Britain and Denmark, were at least 1-2 knots faster. But at that time, screw propulsion served as a “slack-wind pusher”, an auxiliary more than a replacement for sails.

In the official version, it was indeed correctly referred to as an “auxiliary steam engine.” With the installation of the massive engine and the coal supply however, Schwarzenberg’s operating weight increased to 2,700 tons, versus 2,200 tonnes initially so an increase of 500 tonnes. This engine produced 400 hp for a top speed from 10.5 to 11 knots. The original sailing speed was reduced by a knot and the crew increased by 30 men to attend to the engine. An additional 15-20 men were included of acting as flagship after the conversion. Rifle racks and racks for boarding sabers were also standard on deck at the time.

Her lower decks, below the gangway were gutted down to the main hold in order to install a reinforced platform, on which as single 2-cylinder marine steam engine was installed. It’s not clear if it was an HCR (Horizontal Connecting Rod), but it drew a two-bladed not removable, fixed pitch screw propeller aft. This engine was manufactured by Stabilimento Tecnico di Fiume in the namesake city. The number and type of boilers remains unknown. Given the standard of the time, four double-ended, cylindrical, was likely. The smoke was vented through a single funnel, apparently non retractable. It was located forward amidships. This propulsion system generated up to 1,700 indicated horsepower (1,300 kW), and that made for a top speed of 11 knots (20 km/h; 13 mph).

Her former sailing rig was fully retained to supplement the steam engine on long voyages. However when the funnel was in operations, the main course was folded up, and often the mizzne course as well, or the main lower topsail to avoid them blackened by smoke. Since the coal had average qualities at this time, sparks sometimes flew out and could also start a fire so water buckets were always present. When the wind was favoutable, or just to make overseas transits, the steam engine was shut down and all sailed, including studding sails for extra power, were deployed, and she probably could reach around 11-12 knots.

Painted black-brown, with “imitation gold” for her prow and castle decorations and her classoc line of gun ports painted white, she also received a hammock rack around the ship, providing additional protection for the crew against rifle bullets and small shrapnel. Her operational displacement when fully equipped was approximately 2,200 tons. While in service she was seen as a particularly modern ship at the time. Her dimensions were similar to her half-sister Radetzky, so some authors made the choice to speak of a “Schwarzenberg class”, but she was really a league of her own. Radetzky was commissioned about a year later with slightly modified armament, requiring a crew reduced by 50 men. She was also declined into two true sisters, SMS Adria and Donau.

Armament

In 1854: As a sailing frigate she boasted fifty four 30-pounders, six 60-pounders. Of the latter two were on the upper deck as chase and stern guns with better traverse. They were all MLS (Muzzle Loading, Smoothbore) and could not penetrate the armor of ships built from 1859 onwards. This was a 1853 planned armament, no change was made when completed in 1854. Her two initial 15-pounders were so-called “prize cannon.”

In 1862: She was converted as a screw frigate 1862 and since it was nearly ten years after being laid down, her armament was completely modernized. She now had four 60-pounders, 2 smoothbore 15.0 cm (6 inches) guns, forty-two 30-pounders, and four rifled 24-pounders, placed on the upper deck.

From 1866: There was yet another refit. She was now equipped with thirty-six smoothbore 30-pounders, six smoothbore 60-pounders (center of the main battery deck), and kept her four rifled 24-pounder breechloaders on the upper deck. The crew for any bnoarding or landing party ws given an arsenal of 200 rifles, 100 pistols, 36 revolvers, 170 sabers.

From 1876: She had eight 15 cm (6 inches) guns, two 7 cm guns (3 inches). The crew now was given 104 carbines, 24 revolvers and 28 sabers.

After her steam conversion her battery of fifty guns as completed saw six 60-pounder Paixhans guns firing explosive shells plcaed on deck. All forty 30-pounder muzzleloading (ML) guns of two types were in the main batteru deck, but the four 24-pounder breechloading (BL) guns were more likely on the upper deck, notably in chase and retreat with better fire arcs. However in 1866, four of the 30-pounder guns were removed.

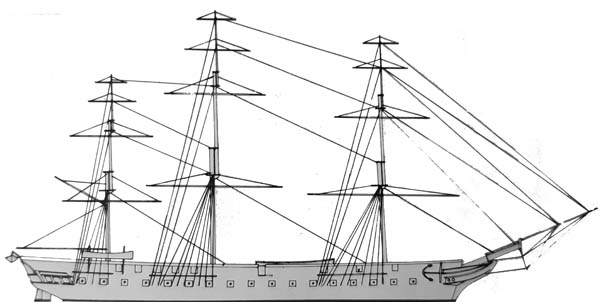

Conway’s profile of Schwarzenberg

1855 Specifications (1862) |

|

| Displacement | 2,614 long tons (2,656 t)(full load) |

| Dimensions | 74 x 14.88 x 6.5 (242 ft 9 in oa x 48 ft 10 i x 21 ft 4 in) |

| Propulsion | 1 shaft marine steam engine, c4 boilers, 1,700 ihp (1,300 kW) |

| Speed | 11 knots (20 km/h; 13 mph) |

| Armament | 6× 60-pdr Paixhans, 40× 30-pdr MLRs, 4× 24-pdr BLR |

| Crew | 547 |

Career of SMS Schwarzenberg

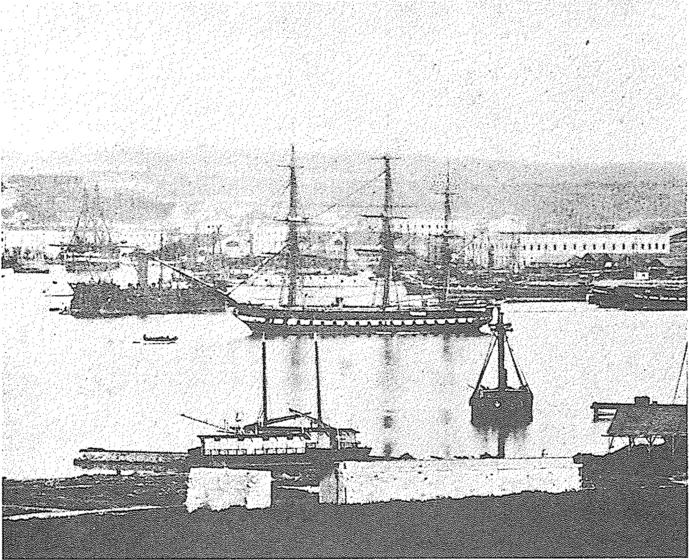

Schwarzenberg (right, afire) with Radetzky and the Prussian vessels astern in action at the Battle of Heligoland

Her keel was laid down at the Venetian Arsenal in 1851. She was launched on 23 April 1853, completed in 1854. She was built very fast, when completed on April 23, 1853, setting a new construction record. Her career from there is not well known she probably spent her first years in 1855-62 training in the Adriatic with possible cruises in the Mediterranean. She was indeed of the the most modern and largest Austrian ship so far, and a power statement.

In 1862, the head of the Austrian Navy, Archduke Ferdinand Max milited for a major construction program, which became the Austro-Italian ironclad arms race. Three new ironclad warships were ordered, and he requested the conversion of Schwarzenberg and Novara from sail to steam frigates as a complement. The Austrian Reichsrat refused to fund the program mostly due to the usual Hungarian and Czech factions, but Kaiser Franz Joseph intervened. He authorized the navy to place orders for the work anyway, and guaranteed his own personal finances as a complement. After returning to service, SMS Schwarzenberg, with Radetzky, and the gunboat Seehund were sent to Greek waters in 1863 after the expulsion of Otto of Greece and internal turmoil. Otto formally abdicated, and the Austrian squadron went to the Levant coast.

She famously took part in the Second Schleswig War.The dispute between Denmark or the German Confederation over controlling Schleswig and Holstein became a war on February 1864, and both the Prussian and Austrian Empires delivered an ultimatum to Denmark. It was clear for both Denmark needed to cede these German-speaking duchies to Austro-Prussian control. However the Danish fleet was at the time a heavyweight in the region, far superior to the plucky Prussian navy. Thus the Danes happily blockaded the German coast. The Austrian Navy was sent under Kommodore Wilhelm von Tegetthoff. Schwarzenberg was his flagship, and the squadron also comprised Radetzky and Seehund still in the Levant when they received the order. They needed maintenance, but were ready to sail. Meanwhile, another, larger squadron was gahered Pola, and was to sail out and meet Tegetthoff underway ideally off the Adriatic Sea. However thet were not ready in time and Tegetthoff prceeded ahead but stopped in Britain to recoal and for quick maintenance. However Seehund was damaged in an accident and left behind. The Austrian and Prussian squadrons later concerted and met in Texel, Netherlands. Since the Prussians were the junior partner, they fell under Tegetthoff’s command.

On 9 May, Tegetthoff received intel about a Danish squadron nearby (steam frigates Niels Juel and Jylland, corvette Hejmdal) off the island of Heligoland. He brought his five ships (2 Austrian frigates, 3 Prussian corvettes) in interception. The Battle of Heligoland showed the Prussian ships were too slow to keep pace and Schwarzenberg and Radetzky confidently engaged the Danes alone. But the Danes concentrated on the flagship, Schwarzenberg, and she was hit many times, and soon in flames. So Tegetthoff broke off the action and escaped to neutral waters around Heligoland, remaining until early the next day. The next morning she sailed to Cuxhaven. The Danies claimed a tactical victory at Heligoland but a strategic defeat as they had to withdraw their blockade. In June at last, the second Austrian squadron joined in, with SMS Kaiser and the armored frigate Don Juan d’Austria. Meanwhile, both Austrian Frigates had been repaired. Now the Danish fleet, outnumbered, remained in port for the rest of the war. After the armistice in July, the Austrian fleet withdrew.

On 9 May, Tegetthoff received intel about a Danish squadron nearby (steam frigates Niels Juel and Jylland, corvette Hejmdal) off the island of Heligoland. He brought his five ships (2 Austrian frigates, 3 Prussian corvettes) in interception. The Battle of Heligoland showed the Prussian ships were too slow to keep pace and Schwarzenberg and Radetzky confidently engaged the Danes alone. But the Danes concentrated on the flagship, Schwarzenberg, and she was hit many times, and soon in flames. So Tegetthoff broke off the action and escaped to neutral waters around Heligoland, remaining until early the next day. The next morning she sailed to Cuxhaven. The Danies claimed a tactical victory at Heligoland but a strategic defeat as they had to withdraw their blockade. In June at last, the second Austrian squadron joined in, with SMS Kaiser and the armored frigate Don Juan d’Austria. Meanwhile, both Austrian Frigates had been repaired. Now the Danish fleet, outnumbered, remained in port for the rest of the war. After the armistice in July, the Austrian fleet withdrew.

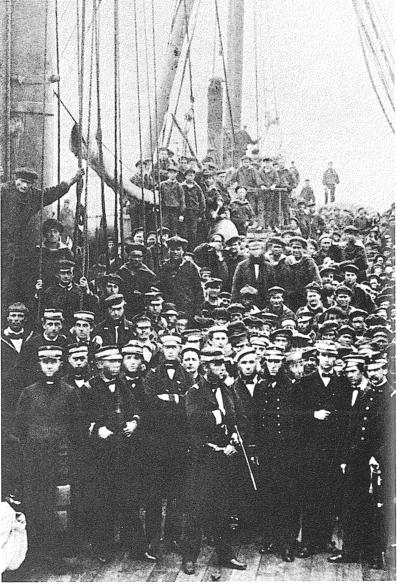

The defeated Austrians at Cuxhaven, note the Schwarzenberg’s missing foremast, which burned up and was cut down. She would be ready again in June.

Next was the third Italian War of Independence and battle of Lissa.

Afrer the Austro-Prussian War flared up in June 1866, the Austrian Navy mobilized, and now had to face Prussia’s ally, Italy, on 20 June. Tegetthoff was now Kontreadmiral and took command of the fleet, preparing crews of hastily raised, untrained men. Preparations and extensive practice in the Fasana Channel was safe from attacks thanks to naval mines, a very early example of the concept of tactical minefields. Schwarzenberg and others were fitted with iron chains draped down over the sides of their hulls for extra protection not being ironclads. But this made them slower and difficult to manoeuver.

On 17 July, Lissa telegraphed about the Italian attack on the island and Tegetthoff was convinced this was not a feint to draw his fleet away from Venice and Trieste. Two days later he sailed out to engage the Italians, almost three time their size. To offset his numerical inferiority her arranged his fleet in three lines abreast. Schwarzenberg and the wooden vessels were in second 900 m (1,000 yd) inside the “arrowhead” made by ironclads. The second line under Anton von Petz behind comprised Kaiser, Radetzky, Adria, Donau, Novara, and Erzherzog Friedrich.

After Tegetthoff’s ironclads rammed and sunk Re d’Italia and badly damaged Palestro, the Italians disengaged, startted to withdraw, and Tegetthoff took his ships to Lissa and reformed the fleet with Schwarzenberg and the wooden ships on the disengaged side the ironclads line. The pursuit was short lived as he was not fast enough. All ships withdrew by night and sailed for Pola. The fight was inconclusive for Schwarzenberg wich never was in ideal position to fight.

Schwarzenberg, date unknown

The 1868 reforms to improve efficiency included removing Schwarzenberg and Adria from service. Schwarzenberg was decommissioned in 1869, and started a new career as non-sailing training ship for naval cadets, replacing the old Venus. She was larger and could train more cadets. By March 1871 she made a few cruises from Pola over a week each every year, supported by the old schooner Arthemisia. She took part in the 1872 training year (300 cadets trained) and manoeuvered with the old schooner Camaeleon in 1873. Same for 1874 and she remained in that role, later static again, until 1890, when struck from the register on 20 November.

Read More

marineverband.at fregatte_schwarzenberg.pdf

de.wikipedia.org/ Schwarzenberg_(Schiff)

scribd.com Austria captive navy

en.wikipedia.org/ SMS_Schwarzenberg

Register der k.(u.)k. Kriegsschiffe. Von Abbondanza bis Zrinyi, Wien/Graz (NWV Neuer Wissenschaftlicher Verlag) 2002.

Benko, Jerolim Freiherrn, von, ed. (1873). The School Ships and Naval Schools During the Period from September 1871 to September 1872. Carl Gerold’s Sohn.

Same, 1 September 1872 bis 1 September 1873.

Clowes, William Laird (1902). Four Modern Naval Campaigns: Historical Strategical and Tactical. New York: Unit Library, Limited.

Embree, Michael (2007). Bismarck’s First War: The Campaign of Schleswig and Jutland 1864. Solihull: Helion & Co Ltd.

Greene, Jack & Massignani, Alessandro (1998). Ironclads at War: The Origin and Development of the Armored Warship, 1854–1891. Pennsylvania: Da Capo Press.

Sieche, Erwin & Bilzer, Ferdinand (1979). “Austria-Hungary”. In Gardiner, Robert; Chesneau, Roger & Kolesnik, Eugene M. (eds.). Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships 1860–1905.

Sondhaus, Lawrence (1989). The Habsburg Empire and the Sea: Austrian Naval Police, 1797–1866. West Lafayette: Purdue University Press.

Sondhaus, Lawrence (1994). The Naval Policy of Austria-Hungary, 1867–1918. West Lafayette: Purdue University Press.

Wilson, Herbert Wrigley (1896). Ironclads in Action: A Sketch of Naval Warfare from 1855 to 1895. London: S. Low, Marston and Company.

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign