c130 ships in September 1939

c130 ships in September 1939

The cruel fate of La “Royale”

La Marine Française (French Navy) is still called “La Royale” to this day (“Royal” (navy)) according to its pre-revolutionary traditions. Of considerable size by 1918, she was drastically reduced after Washington’s treat limitation in 1922, shaping in the end a smaller, but homogeneous fleet of excellent overall quality, but nevertheless with some inherent limitations that would have hampered its capabilities in WW2 if her fate has to serve with the allies for the whole duration of the conflict.

Instead she suffered a cruel fate, most of its officers remaining faithful to Vichy France. French ships were found either sunk, fighting the allies, or scuttled. A fraction however escaped this fate for various reasons, but in the end remaining ships still present in the Empire swapped side due to Admiral Darlan‘s own shifting of allegiance and joined the allies, participating in many operations until the end of the war under the Free French flag.

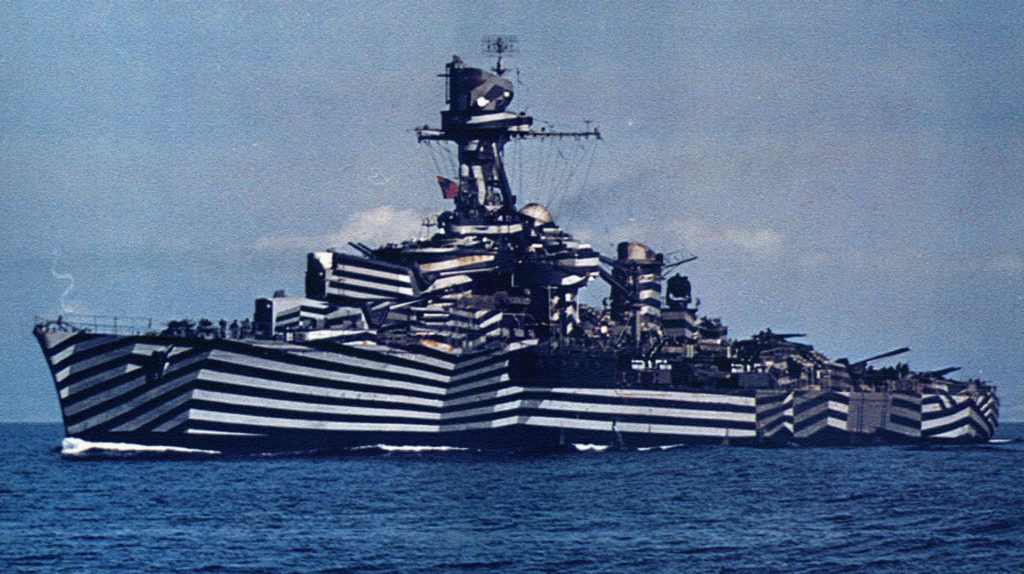

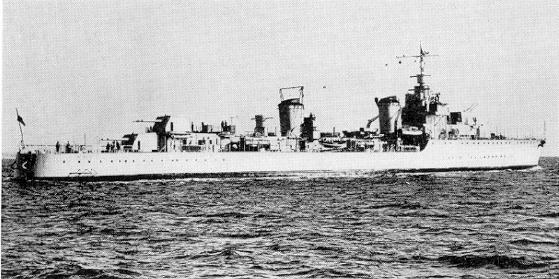

Gloire, Light cruiser of the La Galissonière class, and her famous 1944 dazzle camouflage. Six ships considered particularly successful, derived from Emile Bertin. Their square stern, concentrated armour, triple turrets, and large aircraft facilities were noted.

Articles published and to cover

- 600/630 Tonnes Type Submersibles (1925-38)

- Aigle class destroyer (1931)

- Aircraft Carrier Béarn (1923)

- Algérie (1930)

- Bourrasque class Destroyer (1924)

- Bretagne class Dreadnought Battleships (1914)

- Chacal (Jaguar) class Destroyer (1923)

- Commandant Teste (1929)

- Courbet class Dreadnought Battleships (1911)

- Cruiser Pluton/La Tour d’Auvergne (1933)

- De Grasse (1946)

- Duguay-Trouin class cruisers (1923)

- Dunkerque class Battleships (1935)

- Duquesne class heavy cruisers (1925)

- Emile Bertin (1933)

- FS Jean Bart (1940)

- Guepard class destroyer (1928)

- Jeanne d’Arc (1930)

- L’Adroit class Destroyer (1926)

- La Galissonnière class cruisers (1934)

- Le Fantasque class destroyer

- Le Hardi class destroyer (1937)

- Mogador class Destroyer (1937)

- Redoutable class submersibles (1928)

- Requin class submarines (1924)

- Richelieu class battleships (1940)

- Saphir class submarines (1928)

- Suffren class heavy cruisers (1927)

- Vauquelin class destroyer

- WW2 French Battleships

- WW2 French cruisers

- WW2 French Destroyers

- WW2 French Submarines

Gascoigne class (Project)

St Louis class (started)

La Melpomene class TBs

Le fier class TBs

Surcouf (1929)

Aurore class (1939)

Morillot class (1940)

Emeraude class (project)

Phenix class (project)

Joffre class CVs (started)

French ASW sloops

Bougainville class Avisos

Elan class Minesweepers

Chamois class Minesweepers

French ww2 sub-chasers

Sans souci class seaplane tenders

ww2 French river gunboats

ww2 French AMCs

French Navy in the Interwar

In 1918, the French Navy emerged in a sorry state. Still massive on paper, she has fallen to a lower rank due to a lack of manpower and complete freeze in naval construction but a handful of patrol boats and sub-chasers. Sailors went in the trenches, and often navy officers and future prominent admirals like Muselier and Darlan would learn their artillery trade on the Western Front. The Mediterranean was the main front for “La Royale”, loosing ships to U-boats and mines, especially in the Dardanelles. Shipyards had to be reequipped after 1918, resume construction of the ships started before the war (like the interesting Bearn and Lion class battleships) but there were other priorities ahead, and the funds were not allocated yet.

The French Navy in 1939 (click and support naval encyclopedia)

Washington Treaty consequences (1922)

In 1922, the naval race ongoing at the end of 1918 was put to a complete halt. Europe needed reconstruction, and in general there was a will of de-militarizing society, also shown by the creation of the League of Nations, pet project of President Wilson. As a result, France being a signatory nation, was found relegated on the same rank as the Italian Navy, at 175,000 tons (The US Navy and Royal Navy were allocated 525 000 tonnes, Japan 315 000 tonnes). This was criticized, as woefully insufficient to deal with the Empire.

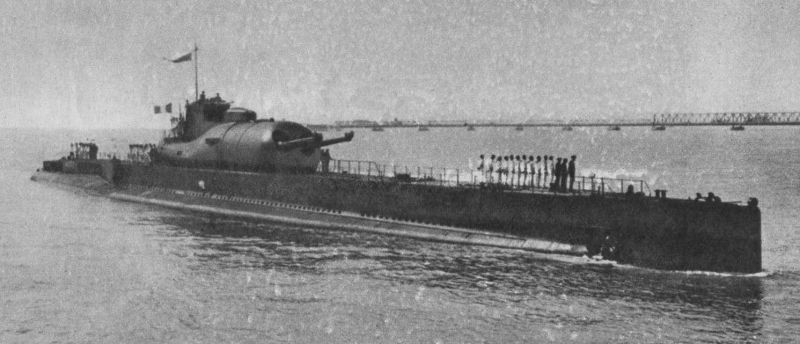

Cruiser submarine surcouf with a dark Prussian blue livery (1925). Morze, nr.6/1936 Public Domain (cc). Like Great Britain and Germany, the French Navy evaluated in a positive way the concept of submarine cruiser as a raiding asset against commerce. Tailor-built with a large hold for captured crews, a pair of 8 in guns and a reconnaissance floatplane, the Surcouf remains the largest French submarine before 1967 (SSBN Le Triomphant)

However, this limit paradoxically led to two consequences: The French navy was able to not disperse itself, concentrating on the most important ships and building a coherent and innovative navy, of far better shape than in 1914. The other consequence was to create a de facto rivalry with Italy. Indeed, not being capable anymore to safeguard the channel or assure a sizeable permanence in the Atlantic, the French navy concentrated in Toulon and the Mediterranean, which was also the way to its colonial empire, in Africa, Syria, and through the suez canal, to Indochina.

This led to a construction programme which was closely matched, almost on a ship-to-ship basis, by the Italian navy. This does however prevented Germany to also built her ships to match the French Navy. By the way, both Italy and France developed locally a tradition of “tin clad cruisers”, lightly built, but very fast. This was also true for battleships like the Dunkerque, which were little more than glorified battlecruisers.

3D Rendition of the Cruiser Algerie – WoW.

The situation evolved however with the arrival of the Algerie in 1931, perhaps the best 10,000 tons cruiser design of the era, and in 1939 with the Richelieu, a true battleship by any means, but retaining French characteristics like the front-only heavy artillery in quadruple turrets (The British Rodney also favored this radical solution) and the “mack” or funnel-mast.

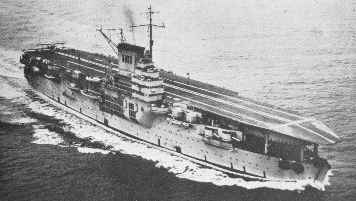

Since there was no limitations for aircraft carriers, France converted its almost finished Bearn battleship into one, the first French aircraft carrier. Two more, this time tailor-designed, of the Joffre class, were added to the programme at the end of the 1930s but suffering delays, they would never be completed.

Strategic presence and duties of the French Navy

Before ww2, “La Royale” was the fourth world’s largest navy, behind the British, American, and Japanese. Its only rival in the Mediterranean was the Regia Marina (Italian Navy) and its other potential rival, the Kriegsmarine (far behind in terms of tonnage) was dealt by the Royal Navy.

Indeed since 1914 the tacit agreement between France and Great Britain was still active, meaning that the French navy in case of conflict, would ensure the bulk of the naval effort in the Mediterranean so the British don’t have to.

To protect the interest of Great Britain, the Royal Navy had neverthless a handful of bases: Gibraltar, closing the Mediterranean westwards, and Alexandria Eastwards, gate-guarding the vital Suez Canal. Toulon, Dakar, Mers el Kebir on the French side were operational bases, some like the latter, being completely rebuild, modernized and enhanced.

However the defeat of France and surrender completely shatterred these plans in june 1940. The Royal Navy was deprived of any support in the Mediterranean, having to face the might of the Italian Navy, the Luftwaffe and even a fiercely neutral, later hostile French navy.

Projects: The what-if French Navy

There are two what-if French Navy scenarios to consider. First: What if the French Navy has maintained its naval construction programme from 1912, including the two new classes of battleships and battlecruisers in the Great war. Second, what if the second world war has erupted two years later, in 1941. There were a whole range of new ships in the yards back then that would have been completed, from the new Joffre class aircraft carriers, Gascoigne class battleships, to the St Louis and De Grasse class cruisers.

In the first scenario, the 25,000 tons Normandie class and 29,000 tons Lyon class battleships would have replaced without any doubt the early Courbet, by 1918 already obsolete with their 305 mm guns in lozenge arrangement. The Lyon class in particular, would have been game changers in the Mediterranean if completed, and IF modernized the proper way. In fact if they had been rebuilt as the four Italian battleships of the class Duilio and Caesare were, they would have been very hard to match in any naval battle.

With perhaps 35,000 tons including ASW bulkheads, 200+ m with a new prow, and no less than 16 x 340 mm guns, they would have largely surpassed their Italian counterparts indeed or constitute a very serious threat against 380 mm armed British Resolution and Queen Elisabeth battleships in Vichy hands.

Completely rebuilt and modernized the Italian way in the late 1930s.

Battleship Normandie if rebuilt in the 1930s (WoW screenshots)

The second scenario would have seen the constitution of two modern Mediterranean “task forces” centered around modern, fast aircraft carriers capable of operating 40+ aircraft each, where the Italians lacked any of the kind, protected by new battleships of the Gascoigne class that showed a more classical artillery with one quadruple turret at the front and rear, and improved protection. The St Louis heavy cruisers were closely related to the Algérie, with an even improved armoured scheme, and for the first time triple 8 in turrets.

They would have been lighter equivalents of the latter US heavy cruisers of the Baltimore class. On the other hand, the new 3900 tonnes Desaix class destroyers would have been improved Mogador, considered as “super destroyers”, cultivating an impressive 42 knots top speed and powerful main armament worthy of “pocket cruisers”.

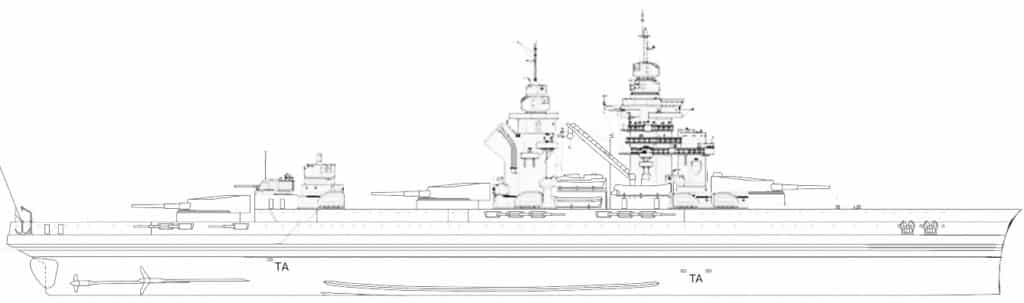

Dunkerque’s own armour internal arrangement.

Beyond the myth: The true French navy of 1939

Now let’s uninflate this straight on: The French navy, despite some appareances was not this modern, high quality navy sacrificed by events history often depicts. First-off, the good-looking Dunkerque class were only glorified battlecruisers, with limited armour and constraints in firing range due to the radical approach in artillery. It should be noted also that so close guns would also meant more shells dispersion and a lucky hit could disable half the artillery (individual cannons protections were added on the Richelieu).

The Richelieu drew most of the lessons and featured an innovative prow, a “mack” later adopted by cold war warships because of the multiplication of radars arrays. Crucially also, the 5 older battleships featured by “La Royale” were never modernized as they should. French cruisers until the Algerie all featured good speed but totally sacrificed protection.

French Destroyer Le Fantasque (ONI USN archives) (cc). With their breakneck speed and powerful armament, the Fantasque and Mogador easily outclassed any other destroyers in the Mediterranean and were a match for Italian light cruisers. But lacking in AA artillery, radars, ASW capabilities or effective air support, there was room for improvement.

The Béarn was a small aircraft carrier, unfit for more modern monoplanes, and slow. The Cdt Teste was proceeding of an old concept of air reconnaissance that was stuck in ww1 naval tactics and of little use in ww2. More crucially, still in 1940 the French navy completely lacked any radar. The device was known but there was no effort at any rate to try to develop this technology. Fairly it has to be precised however that at that stage only the Royal Navy and Germany ventured into it. Neither the Japanese and Italians adopted it, and the US Navy only experimented it in 1941. ASW was limited, relying on ww1-era light ships.

Colorized photo of the French cruiser Algérie, sadly the last french heavy cruiser before long. ONI203 booklet for identification of ships of the French Navy, published by the Division of Naval Inteligence of the Navy Department of the United States (9 November 1942) (cc)

French destroyers had limited ASW grenades, but no dedicated lighter ships, like frigates. Instead, there were a handful of 1930s torpedo boats (with more on order), again, an obsolete proposition. Moreover, AA artillery was poor at best, even by 1940 standards.

Until its refit in New York NYd with modern American AA defence, Richelieu had ony a handful of short-range 13 mm MGs and a few relatively slow-moving, slow rpm dual-purpose guns. Air defence was clearly the least of concerns for the admiralty, which was still obsessed by the concept of “big gun battles” (still shared by many admiralties worldwide).

Order of battle in Sept. 1939

Battleships

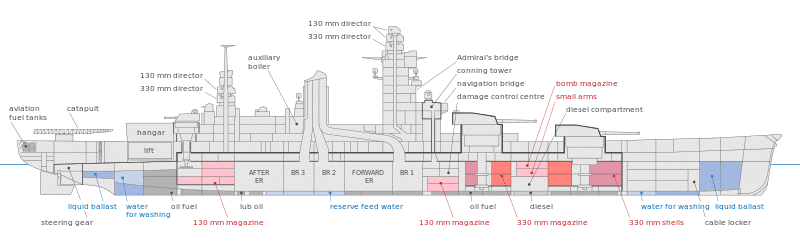

The oldest ones were those of the Courbet class (1911), originally four ships, but France was lost on a reef in the bay of Quiberon in 1922. The Courbet, Ocean and Paris were modernized in 1926-29 with a tripod supporting new rangefinders. Later some (symbolic) AA was added. In 1938, the Ocean was renamed Jean Bart and assigned to Brest as a training ship. The Courbet and Paris served as training ships in 1939. The most active were the three later ships of the Bretagne (Brittany) class (Bretagne, Provence, Lorraine, 1913). Their modernization was more extensive and intervened in 1921, then in 1932-35. This however never matched the scale of the Italian rebuild.

Provence after her second refit in 1936. ONI203 booklet for identification of ships of the French Navy, published by the Division of Naval Inteligence of the Navy Department of the United States (9 November 1942) (cc)

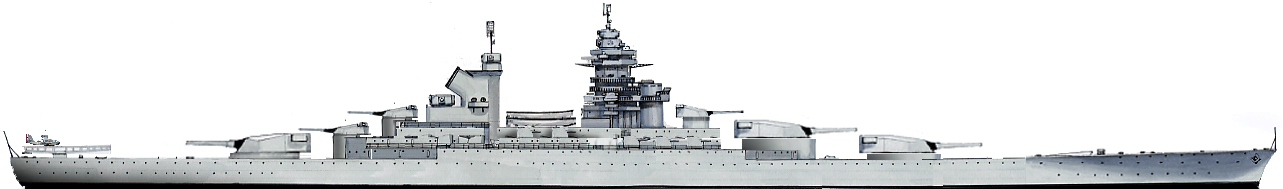

Under construction, the first “super-dreadnoughts”, or fast battleships which existed as blueprints since the late 1920s, were again possible with the expiry of the Washington moratorium. These were the Richelieu and the Jean Bart, two units of 35,000 tons, begun in 1935 (for the first) and January 1939 (for the second). In fact, the Richelieu had been launched in January 1939, and was almost operational in July 1940. So she must be discounted in this picture.

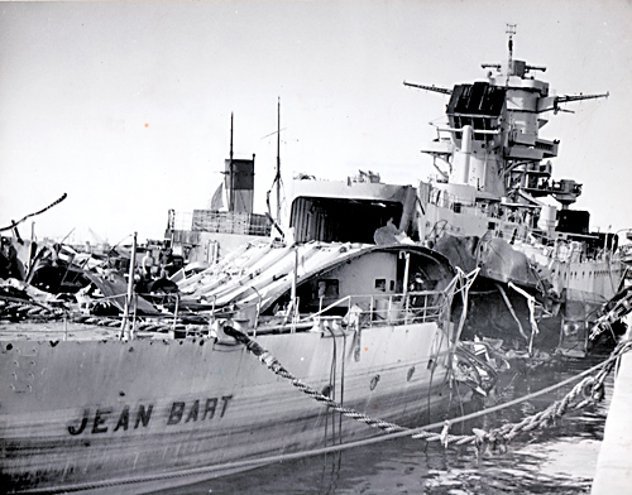

The Jean Bart, for her part, managed to leave the drydocks of Saint-Nazaire and to reach Casablanca, far from being Completed, thanks to Lieutenant Ronarc’h skills and a handful of crewmen, avoiding capture by the Wehrmacht. The other two planned for 1941 and 1942 were the Clémenceau and Gascoigne. The first was launched in 1943 but never completed and her hull destroyed during an allied air raid in 1944.

These ships completed the Dunkerque class. Both inaugurated the twin quad-turrets configuration at the front, but their armour scheme was still relatively light and akin battle-cruisers (They replied to the Deutschland pocket battleships, and were answered by the two German Scharnhorst, also trading protection for speed). Dunkirk and Strasbourg were started in 1932-34, entering service in 1937-38, and were responded by the Italians with their Littorio. Their short career was active, especially between September 1939 and June 1940 when they hunted the German Graf Spee, but sadly ended in November 1943 in Toulon.

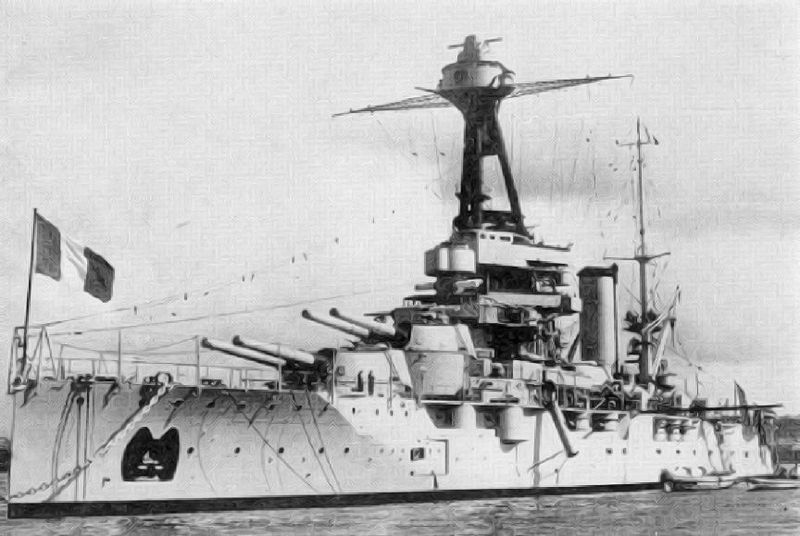

Aircraft carriers

Attempts had been made with the old Foudre during the great war, as well as the Bapaume (a Frigate). But it was not until 1927, after the reconversion and the completion of the Béarn, that the French navy acquired its first aircraft carrier. Former unfinished battleship, she had however some inherited flaws, including a slow speed, but the advantage of a heavy armour and, width to accomodate a large flight deck. Her tailor-made hangar allowed to carry 40 aircrafts, biplanes designed in the early 1930s.

Apart the dive bombers of the LN 401 type and imported SB2U Vindicator (that mostly operated from land bases) Béarn’s own air force was obsolete. Her main fighter, the Levasseur PL.5 dated back from 1924. The Béarn was to be followed by the first dedicated French flat-tops, the two Joffre.

Programmed in 1938, they were considerably larger and faster, and can operate up to 60 modern aircraft. The first was begun in 1938, but was neither launched nor completed. Also in service was the Commander Teste. She was a “seaplane carrier”, quite capable of operating torpedo bombers and reconnaissance seaplanes for the fleet, including the fast Laté 298 torpedo floatplane.

Aircraft Carrier Bearn – Src naweaps.com (cc)

Cruisers

The first were those of the Primauguet class. These three units (Primauguet, Lamotte-Picquet, Latouche-Tréville), launched in 1923-24, were light vessels (main artillery, height 152 mm pieces). These had been first ordered as part of the Lapeyriere plan of 191, later suspended by the war. The first French heavy cruisers were typical of the Washington Treaty models: 10,000 tons, eight 8-in guns. These were the Duquesne class (Duquesne, Tourville, 1925-26), followed by the four Suffren class (Suffren, Colbert, Foch, Dupleix, 1930-32). Algeria, which followed in 1930, was a little different.

Last heavy French cruiser, she had a singular silhouette: lower “flush deck” bridge, single mast-chimney, and tower as on the Dunkirk instead of a tripod. Praised by naval analysts around the globe then as the best possible compromise, she was to constitute the prototype of the future “Saint Louis”, approved in March 1940 but never built, all to be given nine guns in three triple turrets.

Tourville, of the Duquesne class (1925) – State Library of Victoria, Allan C. Green collection of glass negatives Allan C. Green (cc)

The light cruisers started with the school ship Jeanne d’Arc, third of the name, launched in 1930, and Pluto, a minesweeper launched in 1929, rebuilt, and renamed La Tour d’Auvergne little before the war. There was also the Emile Bertin (1933), a prototype of light cruiser featuring triple 6-in turrets, followed by the six La Galissonniere (the galissonniere, Jean de Vienne, Marseillaise, Montcalm, Gloire and Georges Leygues, in service in 1935-37), innovating with a new prow, and reworked squared stern. Their successors, the De Grasse, were to have a tower like the St Louis.

Approved in 1937 for the first two (De Grasse and Chateaurenault), and 1938 for the other two (Only the Guichen was started), they will be caught in the turmoil of June 1940. De Grasse was lated comleted and rebuilt as a post-war anti-aircraft cruiser, a fitting escord for the Jean Bart, and only enlisted and broken up in 1977. Less known, the navy also operated in the interwar two cruisers obtained in 1918 as war damage. These ex-German cruisers in French service were the Metz (ex.Königsberg) stricken in 1936, and the Strasbourg (ex-Regensburg), also stricken in 1936.

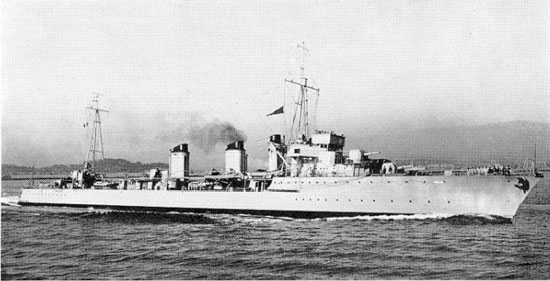

Heavy Destroyer Chacal. Src ONI203 booklet (Division of Naval Inteligence, US Navy Dept.) (9 November 1942). (cc)

Destroyers:

In the case of destroyers, France like Great Britain, Japan and the USA developed “standard” types and “squadron leaders”, or heavy destroyers. Lion (6 units in 1924), Gepard (6 others in 1928), Aigle (6 ships in 1930-31), Vauquelin (6 in 1931-32), and finally Le Fantasque (6 buildings, 1934) class, all very recognizable with their three or four funnels. The latter had only two, and were at the time among the most powerful destroyers in the world with 3,400 tons at full load, 37-42 knots and five guns of 140 mm. They anticipated the new generation of “super-destroyers” of the Mogador class (1936), armed with eight 140 mm double turrets. But the bulk of the fleet was provided by standard destroyers of the Bourrasque and L’Adroit classes.

French super-destroyer Le Triomphant, as repainted in 1940 by the Free French Navy. Tomlin, H W (Lt) Royal Navy official photographer (cc).

Total, 32 heavy destroyers and 38 standard destroyers, showing the the “leaders” first intended were as much important numerically. It was even thought each was capable to deal with two Italian destroyers, making for a clear-cut numerical superiority in this class of ships. Before the war, Le Hardi class destroyers were under construction, 12 units of which only one (Le hardi) began tests in September 1939. 8 others were completed during the conflict, only to be scuttled in Toulon in 1942.

Torpedo-boats

France and Italy considered this light type gradually abandoned by other fleets, as seen as it was useful in the Mediterranean, where the light construction and limited autonomy still justified their use. France retained none from 1918, but put into service those of the La Melpomène class (12 units, 1935-37), while the 12 larger Le Fier class were under construction in 1939. Six were launched and Taken over by the Italians who hoped to finish them and return them to service after their capture and transfer by the Germans.

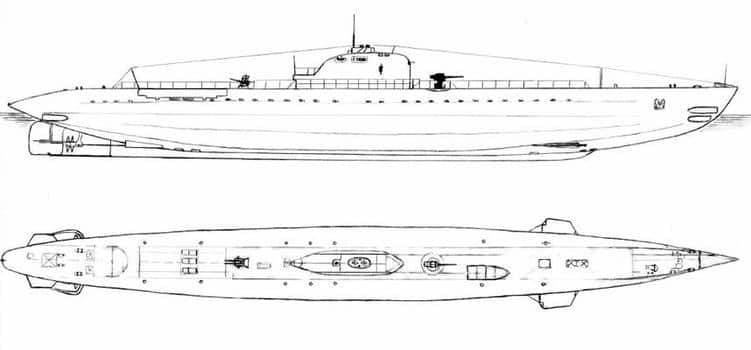

Aurore class submarine – Blueprint – From Plans Marine Nationale

Submarines

France in this field was a pioneer, setting the example with Laubeuf’s Narval, the first modern “submersible torpedo boat” (while other designs emphasised underwater performances and were often overly complex). This 1910 design became the basis of future submersibles for many nations. Under supervision of the controversial young school, “Plongeur” had been conceived as early as 1865. In 1914-18 French submersibles has been very active, with some success. By 1918, several U-boats has been obtained as war damage, and carefully studied, influencing some designs.

For its own sake, in 1929, France launched the famous “Surcouf”, a submersible cruiser influenced by German and British submarine cruisers and projects of 1918. This ship was indeed equipped with two heavy cruiser cannons, 12 torpedo tubes With a comfortable supply, two 37mm AA guns and two 13.2mm double machine guns for close AA defence (impressive by 1925 standards), and featured a hangar and catapult for a reconnaissance floatplane. A showcase of French know-how, her war career was not very glorious and the Surcouf remains a standalone.

Morse, of the Requin class oceanic submarines – ONI 220-M axis submarines manual November 1942 (cc)

France’s interwar submarine fleet was divided between oceanic units (the 31 Redoutable and 9 Requin), and coastal ones (Sirene, Ariane, Circe, Saphir, Argonaute, Diane, Orion, Minerve classes, altogether 40 units.), all intended for the Mediterranean. The Aurore were still under construction in 1939-40. As a result, only the first, launched in July 1939, was operational in time. The others were completed during or after the war). The Rubis was a submarine minelayer that passed early one under free french control, and met successes in many missions as the Royal Navy has no equivalent, sinking 24 ships.

Frigates and Sloops

In 1918, the French fleet had two hundred light units in service, but in 1940 only the small Aviso Quentin Roosevelt, Dubourdieu, Ailette, 11 of the Amiens class and 3 of the Marne class remained in service. Also from ww1, minesweepers of the Ardent (3), Friponne (2), Luronne, Granit and Meulière classes were also still enlisted.

Mistral class destroyers (WoW)

Sub-chasers

8 SC “Eagle” class were light US-built wooden construction units (Elco, 1918), adding to 4 of French construction of the same period, same model, deployed in Indochina. 17 more, (CH1-CH5) were operational in June 1940, and four others under construction. France also experimented with two motor torpedo boats (MBTs), VTB8 and VTB9 in 1935, but leading to no further developments. This was quite the opposite for Italy and even Great Britain. Ironically, France took the opposite of the ideas of the young school, betting on a homogoneous battlefleet rather than a lot of small economic ships. Many had understood that the former role held by traditional torpedo boats was now taken by these nimbler and much cheaper MBTs.

Miscellaneous

The fleet included the gunnery training vessel Condorcet (a venerable 1909 battleship partly rebuilt), and 5 colonial and riverine gunboats for service in China (Yang-Tsé) and Indochina (Mekong) with the two Argus, Francis Garnier, Tourane. Four seaplane refuellers (Sans Souci) were under construction, none were completed. Finally, the role of the fleet included the Castor and Pollux minesweeper, netlayer Gladiateur, submarine supply ship Jules Vernes, 8 Petrel class seaplane tankers and Amiral Mouchez fishery gunboat.

This fine fleet in 1939 was conventional, coherent, and well-trained with a quasi-symbolic presence on the Atlantic at Brest (only a couple of old dreadnoughts and a few destroyers) the rest being deployed in the Mediterranean, facing to the Regia Marina. By then the Royal Italian Navy was qualitatively superior to that of 1914, and aligned to the Axis in an alliance that mirrored the Franco-British tacit arrangement for the Mediterranean, as the Kriegsmarine was far from capable to muster sufficient naval forces locally, but to smuggle out a few submarines. As was often the case in art, thes Washington’s treaty constraint had been salutary. Many recognized the value of this navy that events betrayed in the most tragic and ironic fashion.

- Battleships: 8 (+2 in completion)

- Aircraft carrier: 1 (2 under construction)

- Cruisers: 20

- Destroyers: 70 (32 heavy, 38 light)

- Torpedo boats: 12

- Submersibles: 78

- Others: 58

The French Navy at War

Convoys of the Atlantic, hunting for privateers

This fine instrument, which had been ready in 1939, had been saved from the budgetary misconceptions of aviation or the erroneous tactics of the Army. During the “phoney war”, the fleet was not inactive, far from it. In the Atlantic, the Marine Française patrolled against possible German raiders, although the RN assumed most of this role. In the Mediterranean, the Regia Marina was still neutral (until june 1940), but under surveillance. Patrols in the Atlantic were multiplying in order to track U-Bootes and the Pocket Battleships that has been deployed there. The French navy’s flagships took part in the hunting of the Graf Spee.

French super-destroyer Mogador circa 1939 – ONI Booklet November 1942

Norway expedition

During the Norwegian campaign, it escorted auxiliary cruisers loaded with troops (mainly the foreign legion) without incurring any losses. France did not have this vital need to protect its trade routes directly from the Germans.

The famous photo of the French destroyer “L’adroit”, a 1500 tons, sinking in front of Dunkirk, touched by the Luftwaffe. Although the RAF was fiercely engaged during the French campaign, Churchill decided to withdraw it gradually, then totally, in anticipation of the continuation of the events. A decision that turned out to be salutary, but which resulted in the release of the sky for the Luftwaffe of Göering. But the latter, in spite of certain successes against the Royal Navy and the French navy, did not succeed in preventing the smooth operation of the dynamo operation at its end.

Dunkirk

In May 1940, the “phoney war” ended with the German invasion. If the Allied strategists are confident, reality quickly takes precedence over the many false assumptions of the French command: First, the ardennes breakthrough, the heel of the French defense, and Belgian neutrality, which delays the tactical movements of the French and British northern units. Soon, facing the formidable combined German tactics, the front crumbles from all sides. Guderian’s race to sea encloses half of the Allied forces, now retreating from the north, in a pocket centered around the old city port of Dunkirk.

Bourrasque, sinking slowly at Dunkirk, loaded with troops – Imperial War Museum Photograph Archive (cc)

Here an epic naval rescue operation unfold, in which the French navy takes an active part, losing many destroyers. The Luftwaffe indeed is not hampered by a struggling and preserved RAF and an absent Armée de l’air, which leaves the field open to Stukas. The city is burnt to the ground by waves of Goering’s bombers, but the Luftwaffe fails to kill the gathering troops on the beaches, and in the matter of less than a week, most of the British Expeditionary Force and thousands of French soldiers are successfully repatriated in Great Britain. This episode, seeing French Admiral Abrial complaining about “dishonorable” decisions made by the Admiralty, was to see and the first nail into Franco-British relations hammered. Much worst was to come.

Armistice and consequences

In June 1940, the humiliating armistice of Rethondes is signed. As ink is drying, the fleet navy has lost so far the cruiser La tour d’Auvergne (handling accident), destroyers Jaguar, Jackal, Bison, Bourrasque, Cyclone, Sirocco, L’Adroit, Foudroyant in operations, the Maillé Brézé in March 1940 in Greenock (accidental torpedo explosion), torpedo boat Branlebas, and Rigault de Genouilly sloop. Scuttlings occured, to avoid capture: The Beautemps Beauprés (Brest), CH9, submarines Narval, Morse, Doris, Pasteur, Poncelet, Achille, Ajax, Perseus, Agosta, Sfax, Ouessant (Five by scuttling, the other lost in operations). The Jean Bart, 77% completed, escaped to the Mediterranean thanks to a true feat of seamanship.

Heavy Destroyer Milan – USN Intel Dept. ONI203 booklet Nov 1942 (cc)

Churchill was found in a delicate situation: Having recovered most of the men engaged in the expeditionary force, the small, professional British Army had lost all its material on the beaches, roads and city of Dunkirk. The empire was left with the Royal Navy and RAF to fend off Hitler’s next move. Soon the fate of the French units, although declared neutral by the French according to the Armistice treaty, raised questions. Churchill flet the French betrayed their agreement by signing an armistice, and was soon dubious Hitler was going to respect his word about the French Navy.

The prospect of seeing this intact fleet, falling into the hands of the axis gave cold shivers to the old Lion. The Royal Navy could certainly not face the combined naval forces of Germany, Italy (now in the war), bolstered by the French fleet. It was therefore there that was defined the controversial and difficult operation “Catapult” which repercussions were considerable for the fate of former comrades in arms.

Operation Catapult (July 1940)

At the same time the RAF was mustering all its assets to face the Luftwaffe onslaught, British Admirals were left with their most difficult task ahead: Capturing wherever possible, or disable, “neutralize” French ships by force if necessary. On 2 july, British troops seized during the night a French battleship, destroyers, torpedo boats, minor units, and submersible Surcouf in Plymouth, Portsmouth and Rosyth. Frech sailors are made prisoners for the time being (most, as events will unfold, later choose to leave for France instead of joining the Free French Forces).

Dakar, Senegal’s naval base was not immediately worried, but would be listed for Operation Menace. However the 3 of July, came the ultimatum of Mers el-Kebir, which ends with the shelling of a largely unprepared fleet. This was darkest part, most tragic of the whole operation. Even before, defiance was the rule as if ships that did not left France were Scuttled as ordered, Darlan did not allow departure for UK because he suspected a possibility of British capitulation thereafter, preferring to see them in various Vichy-held French Empire possessions.

At Mers-el-Kebir, the stubbornness of French Admiral Gensoul, associated with the impatience of Churchill meant the ultimatum conditions were to be rejected and Admiral James Somerville of Force H, based in Gibraltar, forced to open fire after a 6-hour delay.

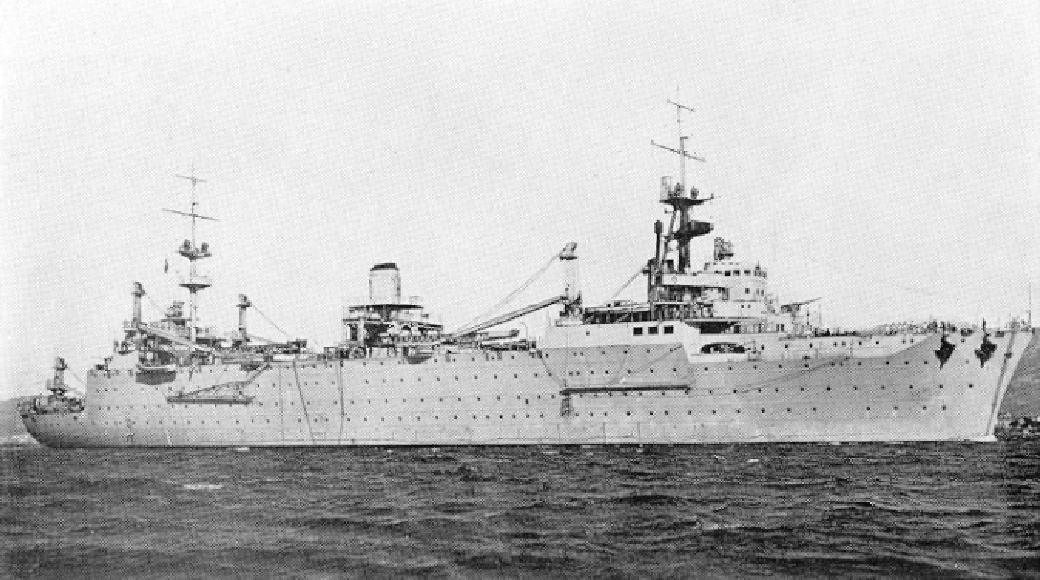

French seaplane carrier Cdt Teste. ONI203 booklet Nov. 1942 (cc)

Opposing forces comprised on the British side, the battlecruiser HMS Hood, battleships HMS Valiant and Resolution, aircraft carrier HMS Ark Royal, and many cruisers and destroyers. At anchor, their stern facing the jetty and the sea, were the French battleships Provence and Bretagne, Dunkerque and Strasbourg, seaplane tender Commandant Teste and six large destroyers. In backup, there was an airbase with bombers and recently acquired American-built Curtiss H75 (that will shot down a British Skua), plus coastal heavy guns and fortifications.

After a bombardment started at 17:54, battleship Bretagne exploded and sank with all hands, Provence, Dunkerque and the destroyer Mogador were badly damaged and run aground by their crews. Strasbourg managed to escape along with six destroyers and made it to Toulon, dodging fire, mines, and air attacks. Further raids will occur on 6 and 8 of July, the latter at Dakar against Battleship Richelieu, by planes of the Hermes, while submarine Bezeviers torpedoed HMS Resolution. Shortly after Mers-el-Kebir the French Air Force in Africa launched half-hearted bombing raids on Gibraltar in retaliation.

The 4 of July in the port of Alexandria, the scenario was to repeat itself, but this time a gentleman agreement between two admirals who know each other well, Cunningham and Godfroy, occurred. Disarmament was decided. Churchill’s orders were not executed without reluctance by officers and sailors alike. The two navies knew each other and stabbing yesterday’s comrade in arms could not be an easy decision.

The outcome was questionable (especially in view of the scuttling of Toulon in 1942), and ironically Hitler also feared the French fleet will join the allies and be turned against him in the Atlantic. Petain also used the fleet as a lever to smooth up armistice application whenever possible. The wole operation was above all Churchill’s means of proving to all his implacable resolve to continue the war, whatever the price to pay…

Mers-el-Kebir: Bretagne is blewing up.

At strategic level, in addition to the rupture of diplomatic relations by France, the whole operation will result in a tightening of Vichy’s positions (as will be shown by Operation Menace in Dakar and the precautions taken in Operation Torch) and prevented effectively the French Navy to join the allies until late 1942 when Darlan swapped sides.

This will also led to bitter fratricidal fights at sea, like a duel on November 9, 1941, between Savorgnan de Brazza (Free French) and Vichy-held Bougainville, defending Libreville (Gabon). In Syria, this situation saw the French fighting Australians, and another British raid on Diego-Suarez, off Madagascar in the fall of 1941.

Operation Torch (Nov. 1942)

Strategically, the gradual involvement of US Forces was to be first turned on a supposed much “easier” theater of operations. North Africa, which can take in a giant pincer the beaten remnants of the Afrika Korps ater El Alamein, was to be the proving ground for the then green 1st division and armoured divisions.

Battleship Jean Bart at Casablanca, 1942. Despite having just one operational turret she duelled with battleship USS Massachussets. Official U.S. Navy Photograph, now in the collections of the National Archives. (cc)

The uncomfortable position of France would continue thereafter, aggravated by the congenital suspicion of President Roosevelt against De Gaulle, and the difficult, intransigent personality of the latter. The only superior officer passed on the allied side, admiral Muselier, was going to try to set up from scratch a Free French Navy with skeletal forces, mostly because of Mers el Kebir (“…this was in our hopes, a formidable axe blow” as wrote De Gaulle).

November 1942 was the great turning point: With Operation Torch (November 8-16, 1942), the Americans in their majority would face Vichy French troops, in order not to endure a vivid opposition that very likely of the British. The situation however varied depending on the sectors and personal preferences and loyalties of the officers in place. It was at the same time for De Gaulle’s Free France project, the expectation to see the “French Empire” switch side to the side of the allies, as it did.

Minelayer Submarine Rubis, class Saphir. Probably the most successful French sub of the war (Author’s illustration).

In spite of the little success of General Giraud to rally Vichy French authorities to the allied cause at first, the latter reversal of Admiral Darlan had a major consequence for the fleet remaining in North Africa, which de facto passed on the allied side, as well as in metropolitan France. Indeed the German reacted to the allied landings by launching Operation Lila on 27 November. They invaded the “free zone”, and race to Toulon to seize the whole French fleet. This risky operation failed, as the fleet, long prepared, effectively true to its word, scuttled totally.

In merely a month, the situation of the French navy changed completely. But it was not until 1943 that these numbers were efficiently involved in the operations, in Italy and Normandy, and even in the Far East. From 2,700 men in November 1940 to more than 5,000 in August 1943, the Free French Naval Forces used a number of valuable units (see below) as well as British and American light units, not to mention technical refit in US arsenals.

The Richelieu in the Far East, 1945 (September 1943 – Official U.S. Navy photograph). The camouflage is experimental. The ship had been fully re-armed two years earlier in NY. She carried the standard AA artillery of American battleships, exception of the dual-purpose turrets, French multiple 135 mm and 100 mm. The Jean Bart, completed at 77% when she fled Saint Nazaire, will be completed well after the war.

As a result of operation “Torch”, French losses (ships stranded, or scuttled) will include the cruiser Primauguet, the destroyers Epervier, Milan, Typhon, Tramontane, Tornade, Brestois, Boulonnais, Fougueux, Frondeur, submersibles Ariane, Danae, Le Conquerant, L’orage, Sidi Ferruch, Argonaute, Diana, Medusa, Amphitrite, Oreade, Sybille, Psyche, Pallas, Ceres.

Toulon scuttling of the fleet. German photo, Bundesarchiv. (cc)

On the other hand, in Toulon, on 27 November 1942, the Dunkerque and Strasbourg battleships, the battleship Provence, Cdt Teste, heavy cruisers Colbert, Foch, Algeria and Dupleix, light cruisers La Galissonnière, Jean de Vienne, La Marseillaise, destroyers Lynx, Chepard, Valmy, Verdun, Lion, Vauban, Eagle, Gerfaud, Vautour, Vauquelin, Cassard, Kersaint, Tartu, L’indomptable, le Volta, Mogador, La Palme, L’Adroit, casque, Lansquenet, Mamelouk, Sirocco, un torpilleur, submersibles Thetis, Vengeur, Espoir, Fresnel, Poincaré, Pascal, Achéron, Redoutable, Diamant, Venus, Mermaid, Naiade, Galatee, Pallas, Ceres, and D’Iberville sloop scuttled, and became dry losses.

The Germans no longer felt bound by the conditions of armistice after the American landing in North Africa, and seized the French ships based at Bizerte, and tried to recuperate some units scuttled in Toulon. Some were to resume service under axis flags in 1944-45. These were the destroyers Tigre (FR23), Panthere (FR22), Valmy, Lion (FR24, FR21), several units of the class Le Hardi, FR32 to 37, torpedo boats (class La Melpomène) FR41, 42 and 43, submersibles Such as the former Requin class (FR111-114), the FR117 (ex-Circe), FR112 and 116 (ex-Saphir and Turquoise) were thus expected to reinforce the naval forces of the Kriegsmarine in the Mediterranean or the Regia Marina. But even in that case many French workers sabotaged this process at any level, considerably slowing it down, until these ships were operational.

French cruiser Gloire, as repainted with its distinctive dazzle camouflage and rearmed in an US arsenal, 1943. Author’s illustration

Free French Naval Forces

The strength of the FNFL (Forces Navales Françaises Libres) had increased significantly since January 1943: Battleship Richelieu, which joined NyD (New York) from Dakar, light cruisers Montcalm, Georges Leygues, Gloire, Emile Bertin, old battleships Courbet, Paris and Lorraine, soon Relegated to secondary roles, aircraft carrier Béarn (used as aircraft transport), heavy cruisers Duquesne, Tourville, Suffren, light cruisers Duguay Trouin, Jeanne d’Arc, upgraded to the standards of the US Navy, destroyers Leopard, Albatros, Le triomphant, Le Fantasque, Le Malin, Tempête, Mistral, Trombe, L’Alcyon, Le Fortuné, Forbin, Basque, Torpedo boats Melpomène, submarines Marsouin, Archimède, Argo, Protée, Pégase, Le Glorieux, Le Centaure, Casabianca, Rubis, Perle, Antiope, Amazone, Orphée, Junon, Minerve; Or the Savorgnan de Brazza sloop, 9 Elan class minesweepers, and 4 Chamois, representing about half the naval strength of the French Navy in 1940.

Cruiser Foch, unknown date (Royal Navy Photo) (cc)

In addition, the Allies supplied 15 Minesweepers, torpedo boats of the Fairmile A and Fairmile B models (17 units), 32 other ASW boats, 5 Elco type torpedo boats, and between March and November 1944, 32 US sub-chasers of the “PC” type, And 52 of the “SC” type, most operating in the Mediterranean.

Cancellations, Projects, and What-ifs

In September 1939 the French Navy, like in 1914 was caught a bit off-guard, but far less than the poor state she was in prior to vigorous reforms and naval plans of 1912. The battleship program really was started like other nations at the expiration of the Washington treaty ban and soon several classes of battleships were planned, of which only the first class, Richelieu, barly made it in operational stage. Sister-ship Jean Bart was left uncompleted in Casablanca for the duration of the war. This class was to be followed by the Gascoigne.

Gascoigne class battleships (1939)

In addition to the Richelieu-class BBs, two other sister-ships were planned for the next naval section, following B3 specification of 1938. They were to be laid down after the Richelieu and Jean Bart were launched, in the largest French docks available. Technically, they were true sister-ships, the only significant difference being their second quadruple turret relocated aft, to enable retreat fire, while the secondary artillery was relocated forward. This design was considered more balanced, incorporating changes and lessons learned from the first squadron exercises with the Dunkirk class. Their on-board aviation was moved to the center and radars were planned for them, a ballistic computer and radar-assisted rangefinders and fire directors. Theyr kept their unique “mast-stack” arrangement. The main artillery remained the same with eight 15-in/380mm (2×4), twelve of 6-in/152mm (3×3), sixteen 4 in/100mm (8×2) six twin 37mm, six quadruple 13.2 mm AA. They also had larger dimensions (252 meters overall versus 248) for a tonnage reaching 51,000 tons fully loaded. However this class was never started and remained on the drawing board.

Alsace class battleships (1942)

wow what-if battleship Alsace, as she should have been completed in 1945. Three quad turrets instead of two, including one in retreat gave her a substantial advantage compared to the Richelieu class, and Gascoigne.

This was a second design variant elaborated at the same time as the Gascoigne/B3. They were planned in response to the two German H-class battleships started after the Second London Naval Treaty collapsed. The Alsace class design was based on the larger initial variant of the Richelieu class, when three proposals were submitted to the admiralty. These included either nine (3×3) or twelve 380 mm (15 in) guns (4×3) or nine 406 mm (16 in) (3×3) guns, but no choice was made before the program ended in mid-1940.

It seemed the naval command settled on the nine 380 mm design in three triple turrets, a rather standard configuration at that time. However three-gun turrets would have been complicated to make apparently, causing significant delays during wartime construction. These ships were larger, imposing significant improvements the harbor, naval yards and shipyard facilities. Construction of the first, presumably named Alsace scheduled for 1941, plan were terminated by the German victory in June 1940.

Unnamed 1942 naval plan battleships

wow’s rendition of the very hypothetic “Republique” class. The configuration would have been the same as the Gascoigne, with one turret after and forward, but of a larger 16-in caliber, or 406 mm. In reality, this proceeded from an hypothetic variant with three triple turrets, not two as shown here, but rather a 2×4 variant of the rearlier Richelieu. By any standard, designing such large turrets would have taken years.

Author’s resconstruction of the Alsace class

St Louis class heavy cruisers (1939)

The heavy cruiser Algeria was considered the most successful of the “washington cruisers”, an almost perfect technical compromise within the treaty limits. But this was also the last heavy cruiser class as France was signatory to the 1930 London treaty, limiting the tonnage of 8-in armed cruisers; The intended new class was planned to replace the Duquesne class crusiers, voted in 1939 after the 1936 second London treaty’s accomodations.

As a result, the new class, to be named Saint Louis (after a famous French medieval King) and was to include four ships, of a completely different standard. Designed displacement was more than 14,000 tons, with a main artillery of nine 8-in or 203 mm guns (in three triple turrets, a configuration then in favous in many navies). Another innovation, the Saint Louis class was to have a “mack” or French typical mast-stack, as for the Richelieu (and De Grass cruiser class). In addition the St Luis were to be equipped with a sonar and a radar, although retaining spotting seaplanes.

With 202 meters in lenght overall, 20 m wide, an armor increased to more than 210 mm in some areas, and a fully loaded tonnage estimated to around 16,000 tons, these cruisers were tailored to effectively replicate to the German heavy cruisers of the Blücher class (1937) and their successors.

In addition to their main artillery, they were fitted with eight twin 100 mm turrets and eight twin 37 mm also in turrets, of a new model that was adopted by post war French escorts and destroyers. Their parsons turbines were coupled with 6 Indret supercharged oil-fired boilers to give them 130,000 hp for a top speed of 34 knots. Construction was approved in April 1940, but their was never started or approved, cut short by the events of May 1940. If they had been built, they would probably have been in service in 1943-44, very comparable to the US Navy Baltimore class.

What-if rendition (wow) of the St Louis class.

De Grasse class light cruisers (1939)

The replacement of the Duguay-Trouin class, dating from the 1920s, had been considered since 1936. Approved in 1937, the new class (later named De Grasse, Chateaurenault and guichen), was ordered in 1938 and construction of the lead ship started at Arsenal de Lorient in November 1938. In June 1940, with shortage of workforce and equipment, construction of the hull was suspended. In fact, afer the armistice, the Vichy regime was allowed to resume construction on its own account, but problems labour shortage remained. In addition there was a fear she could be recovered by the Germans after construction, so work progressed at snail pace. It was resumed after the war on new plans in 1948, converted as an anti-aircraft cruiser in 1950. In this new role, she served until 1976 (see the cold war section).

De Grasse as initially planned was basically a better protected version than La Galissonière, while keeping the arrangement of three triple turrets. Antiaircraft artillery consisted of six dueal purpose rapid firing 90 mm in three twin turrets (placed at the rear), as well as five 25 mm in single mounts, rapid-fire model. In addition, they had quadruple 13.2 mm mounts and two triple 550 mm torpedo tubes banks. They also carrid a generous allocation of varied seaplanes, four, two Loire 130 observation and artillery spotters and two ASW/torpedo bombers of the Laté 298 type. The De Grasse class kept their square stern but were larger at 176 meters long for 18 meters wide, displacing 9900 tons fully loaded. Propulson-wide they had four propellers and parsons turbines fed by four supercharged oile-fired indret boilers for a total output of 110,000 hp and 33 knots.

Desaix class heavy destroyers (1938)

The Mogador class were mere “prototypes” of a new generation of heavy destroyers designed to escort fast battleships of the Atlantic-based raid force. This Desaix class was approved in May 1938 and included Desaix, Hoche, Kleber and Marceau, followed by another serie of six ships, the Bayard class, approved in April 1940. The first was planned the completion around 1942, 1943 fo the next one. Unfortunately, construction never started and stayed at paper level.

The Desaix class was closely derived from the Mogador, including the “pseudo-turrets” twin 130 mm. However, it was anticipated a more adequate electrical installation was needed, so the first feedbacks from the Mogador in service made it possible to redesign the rudder as well for more agility (the Dunkirk class BCs were more agile !). The Desaix were larger and heavier (3,000 tons standard, 3,900 to 4,100 fully loaded, 139 m long overall by 13 m). They were part of the wave of so-called “super-destroyers”, more than leaders, light cruisers in reduction. Their AA artillery consisted of twin 37 mm mounts and quadruples 13.2 mm mounts. Their six torpedo tubes were axial and top weight had been significantly reduced, improving stability as gun platforms. If built, they would have been formidable adversaries for any destroyer and more than a match for some light cruisers liike the Italian Guissano class.

Le Fier class torpedo boats (1938)

Replacements of the Melpomene-class torpedo boats, considered too narrow for practical use, was to be done with the new serie of “Le Fier” class ships. Almost light destroyers in tonnage (1010 tons standard, 1337 tons fully loaded), they were approved in 1938, their keels laid down at the Loire and Brittany yards in 1940, but they were never completed. The most advanced ones were captured by the Germans and construction resumed for completion. But they were never completed due to repeated sabotage from local workers, and they were eventually burned after the Allied landings of Normandy.

The Fier class were to be equipped with two twin “pseudo-turrets” of 100 mm, two in a superfiring pair aft and one forward to reduce weight on the forecastle and for stability. Th AA took place on the forecastle, two quadruple 13.2 mm mounts. Four torpedo tubes in two axial banks completed the armament. They would have been good steamers with a much better autonomy, their turbines being fed by three Indret boilers for a rated power of 30,800 hp for 33 knots. Their hull measured 95 meters by 9.40 m wide, the crew should have included 136 officers and sailors.

Sources

https://www.ffaa.net/

https://www.batailles-1939-1940.historyboard.net

https://www.meretmarine.com/fr/content/histoire-la-flotte-francaise-en-1939

www.flottille9f.net

French warships colorized photo

3dhistory.de French BB blueprints

More: //commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Scuttling_of_the_French_fleet_in_Toulon

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign