A visual of the area and route taken by the Allied ships. Although this engagement was all but fair (a recent dreadnought against an old cruiser) the ultimate result was almost a year round of inactivity for the Austro-Hungarian Navy (K.u.K Kriegsmarine) in the Adriatic

A visual of the area and route taken by the Allied ships. Although this engagement was all but fair (a recent dreadnought against an old cruiser) the ultimate result was almost a year round of inactivity for the Austro-Hungarian Navy (K.u.K Kriegsmarine) in the Adriatic

The Austro-Hungarians at war

The war broke out because of the Balkans, the assassination of Archduke Franz-Ferdinand was followed by a rejected inquiry by Austro-Hungarian authorities to Serbia, followed by a rejected ultimatum and war. By the alliances game, Serbia had the support of its natural ally Russia, which in turn could count on France. In response, Austria-Hungary was able to count on the German Empire for backup. But the first engagements of the Austro-Hungarian Army against Serbia, despite clear advantages, was nothing of a promenade. The Serbs managed to block and even repel the initial attacks with massive payback.

Situation in the Adriatic

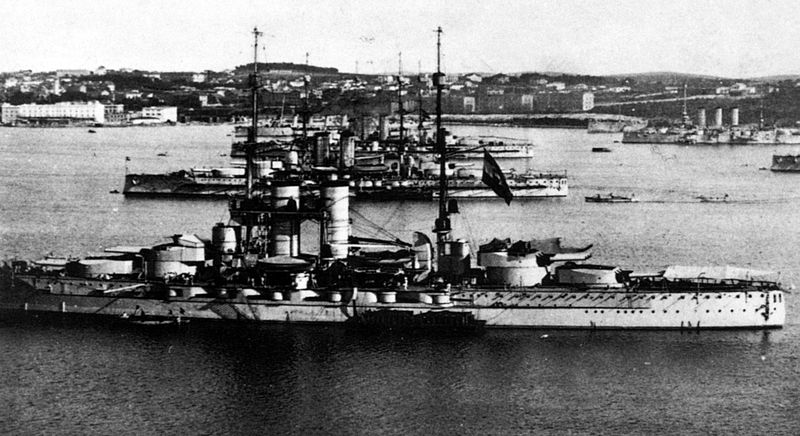

On the naval front however it was expected from the K.u.K Kriegsmarine to take advantage of a clear cut superiority in the Adriatic. At that stage, the Austro-Hungarian Navy was not to be taken lightly with three brand new dreadnoughts (a fourth in achievement), 12 pre-dreadnought battleships, 13 cruisers, 27 destroyers and 79 torpedo-boats, as well as 7 submarines and many monitors and auxiliary ships of all sizes and tonnage. It was based mostly in Pola harbour and could easily defeat a very weak Montenegrin navy (perhaps a single gunboat, no info could be found) whereas the Serbian “navy” only counted a single patrol boat Jadar, based on the Danube in 1915. Since Italy was neutral, and perhaps then more inclined to join the central powers, Austro-Hungary has free hands in this “private lake” bordering the Balkans. In the Mediterranean however, this was another matter.

Austro-Hungarian Dreadnoughts and the fleet anchored at Pola. Despite real assets, from 1915, it was dwarfed by the combined might of the French, British and Italian navies and mostly condemned to inaction, trapped in the Adriatic.

At that time, since June 6, the proportion of the French fleet in the Mediterranean was such that the British thought fair to let the supreme naval command in the area to the French, the British naturally receiving supreme command of the Allied naval forces for the north sea. Thus, by treaty on June 6, the Royal Navy there was reduced to two armored cruisers (Defence and Warrior) and some light cruisers after by massive transfers to the North Sea,theoretically under the orders of Admiral Boué Lapeyrière. The latter, from the outset of the declaration of war, rallied Malta with the combined forces, then joined the Adriatic by executing an ostensible “naval review” in full strength and regalia to impress still undecided Italians.

The battle

On August, 14 the French fleet enters the Adriatic included 15 battleships (2 Courbet, 6 Danton and 5 Vérité), 6 armored cruisers (3 Léon Gambetta, Quinet, Renan, Michelet) and smaller cruisers. It was followed by British-armored cruisers from Gibraltar, the squadron of Admiral Troubridge. Alerted, the Austro-Hungarian fleet scrambled to rally in emergency the safe harbor of Pola. But Zenta had not been informed, and was still conducting operations of shelling of the small Antivari harbour.

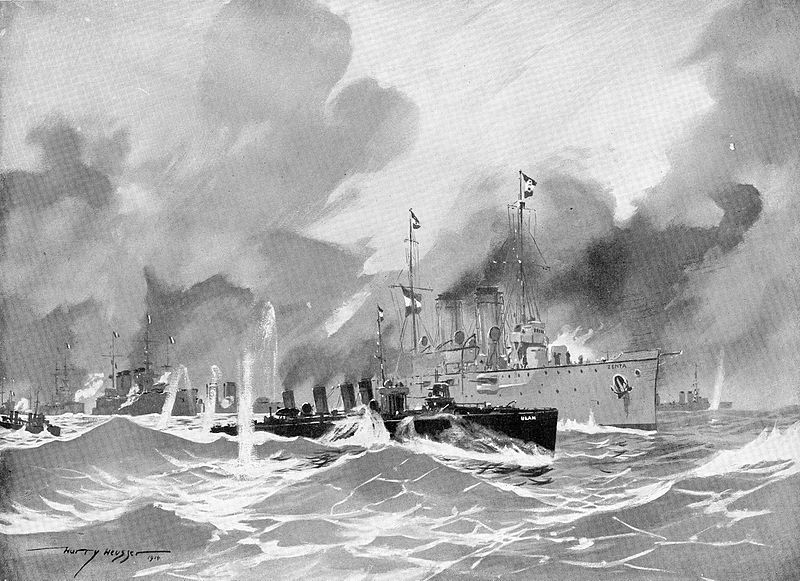

She was safeguarded by destroyer Uhlan and 2 others. None did noticed the Courbet, a recently built dreadnought which opened fired at 20 000 m range. Soon 305 mm plumes squared the Zenta, which had no artillery capable of replicate at such distance. In very little time, the Zenta was severely hit, immobilized, and rendered all but helpless and burning. Her crew evacuated the soon-to-be hulk on rafts. The Destroyer Uhlan and two destroyers managed to flee thanks to their speed. The Zenta sank in a short time, but most of its crew safely joined the coast.

A painting of the battle of Antivari, by Harry Heusser, 1914.

Aftermath

This modest setback meant that the allies could now roam at will the Adriatic, blocking all the Austro-Hungarian initiatives. Initially at least, French presence dissuaded the naval forces stationed at Pola to start new coastal raids. But soon the allied forces departed and would be fully absorbed by operations in the Dardanelles. The Austro-Hungarian was then again free and ready for any action but only for a short time: Italy entered the war at about the same time. We will return on this chapter of the adriatic naval campaign soon. The “inaction” ended with a first major action Battle in Decemlber 1915, the battle of Durazzo, followed by by the Battle of the Strait of Otranto in 14-15 may 1917.

The Austro-Hungarian fleet

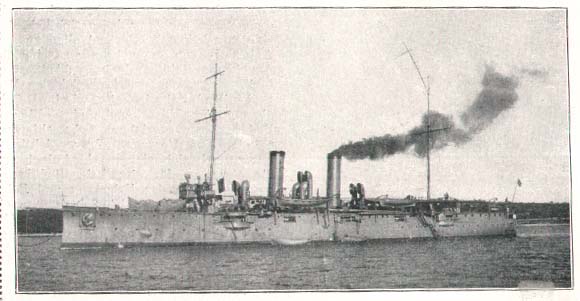

The cruiser Zenta in 1914.

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign