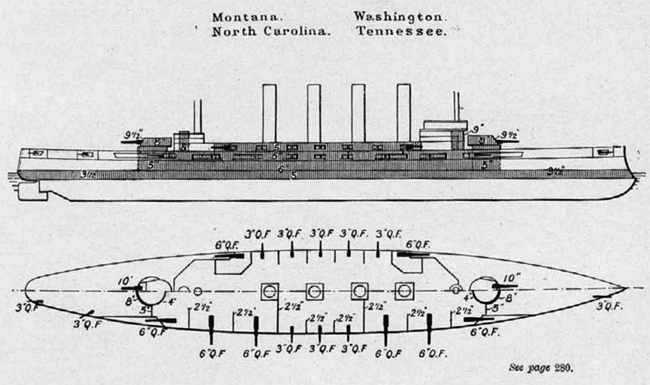

USA – USS Tennessee, Washington, North Carolina, Montana (renamed Memphis, Seattle, Charlotte, Missoula) ACR-10-13.

USA – USS Tennessee, Washington, North Carolina, Montana (renamed Memphis, Seattle, Charlotte, Missoula) ACR-10-13.WW1 and prewar USN Cruisers

Atlanta class | USS Chicago | USS Newark | USS Charleston | USS Baltimore | USS Olympia | USS Philadelphia | USS San Francisco | Cincinatti class | Montgomery class | Columbia class | New Orleans class | Denver class | Chester class | Omaha classUSS New York | USS Brooklyn | Pennsylvania class | Saint Louis class | Tennessee class

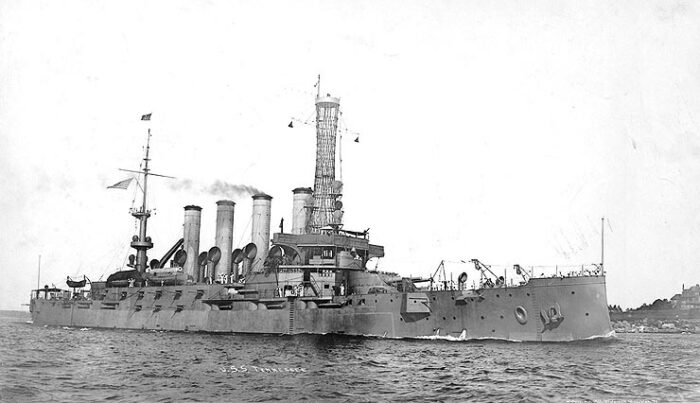

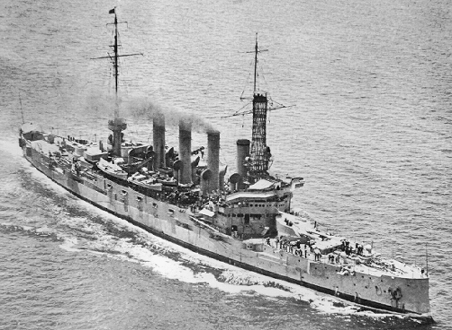

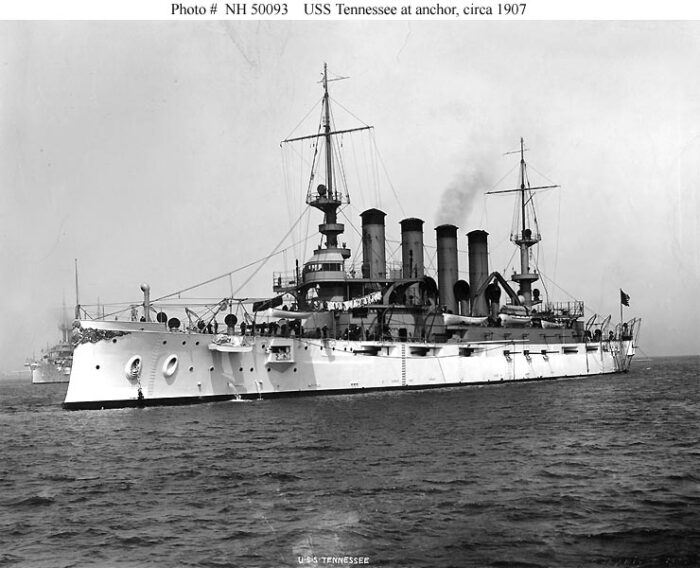

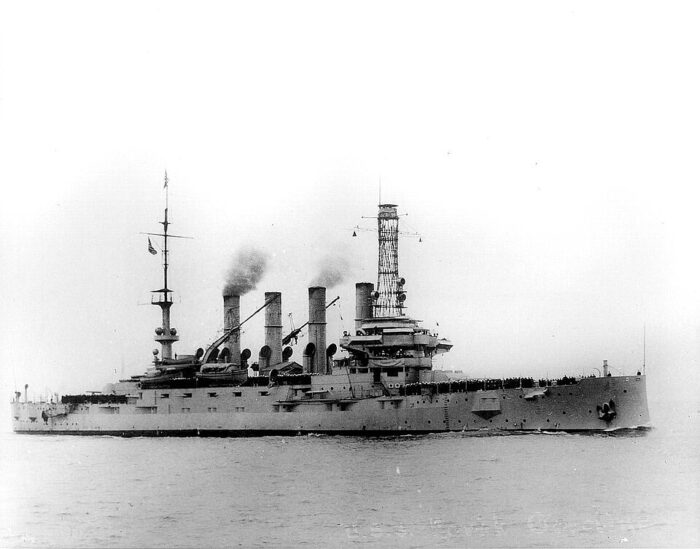

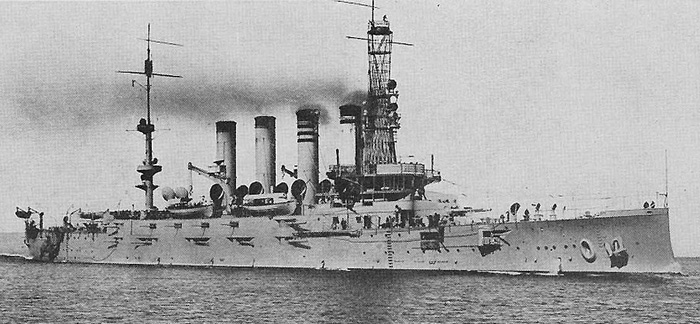

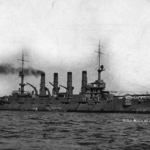

The Tennessee-class were four armored cruisers built for the United States Navy in 1903-1906 and very close in concept to the Pennsylvania class launched in 1903. By oulook, output and general dimensions, they were near-sisters and completely different from the Saint Louis built at the same time. The main difference with the Pennsylvania was their main armament of four 10-inch (254 mm) guns instead of 8-in guns. This was the heaviest carried by any American armored cruiser, but as compensation their protection ended thinner than that of Pennsylvanias. Less for technical reasons than the newly imposed congressional restraints on tonnage for armored cruisers. This put a condundrum as they still needed to reach 22 knots and in general, the USN considered this design as an improvement. Only four were built, the last completed in 1908. They were also the last US cruiser with the Chester class scouts for more than a decade. Their career was relatively uneventful in WWI and they were all renamed to free those for new battleships, before being discarded in 1920, albeit Tennessee was lost due to a rogue wave.

They were the best ever US cruisers and remained the largest at 14,000 tonnes before the 1942 Baltimore class.

These were, for all intend and purposes, the last US Navy armoured cruisers. The type vanished completely but came back in a very different way in the 1920s as the heavy cruisers. They were virtually a repeat of the previous Pennsylvania in overall appearance, but there were reasons to be different as well, between the USN admiralty wanting some improvement in the “battle line department” while caught at the same time by the Congress hostile to prevent a global tendency for these cruisers to go into battleship territory. It shlould be added than when they were started in 1903 and 1905, HMS Dreadnought was still not there (albeit the existence of this ship was no mystery) and so the later concept of the battlecruiser had yet to materialize. But the Tennessee class ended nevertheless as the last US armoured cruisers. Also, crucially, the Russo-Japanese war and its lessons were not there yet either.

In 1903, there had been an evolution of concept, from scout, convoy escort and commerce raider, traditional attribute of the cruiser as a continuation of the frigate, to an auxiliary capital ship in a battle line, despite their weaker protection. The Battle of Tsushima in 1905 validated this concept, but their design has been already setup two years prior. In U.S. naval circles their design was continuously put into question regarding speed, armament or armor and all agreed that with this design a limit had been reached and no such cruiser type was started when the Invincible-class battlecruisers (started in 1906) obviously made their concept obsolete just as the pre-deadnought capital ships were. No nation from then on, apart Italy and Austria-Hungary, started new “classic” armoured cruisers. Japan already created some intermediate vessels. In December 1914, the superiority of the battlecruiser over an armoured cruiser was clearly demonstrated when the same Invincible class defeated the Schanhorst class and put an end to Von Spee’s rampage. The US will study and mature their own brand or battlecruiser, but it had to wait for the start of the war indeed to see them funded and started.

Design of the Tennessee class

The previous Pennsylvania class

Development

Globally since 1900 there was a race on armored cruisers both in defence and attack of maritime trade, or just to deter anu aggression at foreign stations. To face any eventuality, a general drive towards larger guns, better armor to start to approach battleships and good speed necessarily pushed towards 10,000 tonnes designs and more. The Royal Navy had its ownmotivation in this by facing similar drive in the Imperial German Navy, seeing, rightly saw, the lineage of German armoured cruisers, soon deployed in the Asiatic squadron as a potential threat the the Empire. There was the Cressy class in 1898, part of an ongoing effort to built 35 armoured cruisers, reaching a peak with the 14,600 tonnes Minotaur class, 23 knots and with four 9.2-inch (234 mm) and ten 7.5-inch (191 mm) guns, at the time, a world record. France also followed the same patterns, reaching its own zenith with the 14,000-ton Edgar Quinet class with no les than fourteen 7.74-inch (197 mm) guns and a superior armour.

Germany pushed ahead with 14 armored cruisers for its overseas stations, culminating wit the 13,000 tonnes Scharnhorst and Gneisenau. Japan was another case, digesting the 1st Sino-Japanese War in 1895, then cashing in the humiliation of the “Triple Intervention” and launching its “Six-Six Program”. From the modest 9,000 tonnes Yakumo, the country was looking for much larger vessels and reached in 1912 with the Tuskuba class at 13,700t a milestone with 12 inches gun. They were for this called “semi-battlecruisers”.

Back in the US President Theodore Roosevelt was impressed by Japan’s successes and wanted to promote further American interests in the Pacific, notably maintaining a “controlling voice” in the Philippines in 1902 and sending the Great White Fleet on a show of force in 1907, which only motivated Japan pushed its program further, eonly encouraged by its results after its 1905 victor. The fall of Russian in the regions for most analysts meant a rising rivalry with the United States in the Pacific. The US program thus led to the construction of six 13,680-ton Pennsylvania-class cruisers with four 8-inch (203 mm) and fourteen 6-inch (152 mm) guns, then 6 inches (152 mm) of belt armor, capable of 22 knots.

Yet many in the naval staff criticized the limited size of their armored area and main guns caliber compared to their generous displacement. The Bureau of Construction and Repair (C&R) requesting funds from Congress for two more such ships FY1901. However the Congress denied this and so the Secretary of the Navy launched a study for new armored cruiser designs that Congress might approve. A much smaller, 11,000-ton design with thinner armor was proposed by the Board’s new Chief Constructor, F. T. Bowles as more “politically acceptable”. They were accepted indeed as the Saint Louis class but contested by Rear Admiral R.B. Bradford, of the Bureau of Equipment and Recruiting, who wanted ships homogeneous in size and comparable in overall strenght.

Thus, based on this, several design issues were raised and worked out by C&R before any design can be finalized. Bowles criticized what he saw as inadequate protection in the Pennsylvanias, notably the deck armor protecting the magazines and preferred the British approach of having the magazines buried deep below the waterline and pushed out from the sides. US cruisers had heavier armament however their larger magazines caused concerns.

Design F:

The new core design first submitted was the 14,500 tonnes “F” in which Bowles extended the casemate armor to include the turrets while increasing the beam to compensate for the added weight. He wanted the armour to be 1 inch thinner than in the Pennsylvanias however and concentrate the 6-inch guns at the ends of the ships to maximize protection. The question of armament bounced when the bureau of Ordnance proposed a new 10-inch (254 mm) heavy gun and 7-inch (178 mm) secondary gun. The latter was interesting as being the heaviest possible to be still handled manually.

Design G:

Design “G” included four of the first and siwteen of the second. But Bradford suspected weight constraints would force a return to 8-in cannons as more practical. The weight of four 10-inch and sixteen 7-inch guns indeed called for a radical compromise, thinning down the armour by 1.5 inches (38 mm) for flat surfaces, 1 inch (25 mm) for outside slopes.

Design H:

Design “H” maintained four 10-inch but compromised with 6-inch (152 mm) secondary guns, and maintained a better protection: 5 inches (127 mm) of casemate armor with better coverage from top to bottom between turrets. It also protected the ammunition stores for the 3-inch (76 mm) light guns.

Design H was the one for which well were confident enough, to be submitted to the Secretary of the Navy on 31 July 1901. The latter apporoved it, but requested to add two more 3-inch guns and better protection for the 6-inch battery.

Congress Limitations

By that time Congress was concerned about rising tonnage of the new battleships and cruisers proposed and set an overall limit for all cruiser at 14,500 tons (like the Pennsylvanias) for any new design submitted FY1902 naval building program. It paralleled another limit set for battleships that would crippled effort to produce a good first dreadnought later. Problem, design “H” was 14,700 tons. Chief Eng. George Wallace Melville requested lighter engines and boilers for these ships as a measure, yet, capable of producing 2000 more indicated horsepower. There was indeed a total of 1500 tons that needed to be eliminated. The machinery adopted would prove indeed capable of reaching, with a sligtly reduce doverall weight, enough extra horsepower to match the Pennsylvania’s 22 knots. Boiler weight saving could not be obtained however for preceived safety reasons and he Melville expressed doubts about having a reliable machinery capable of 25,000 horsepower weighting the same as the one which produced 23,000 horsepower on the Pennsylvanias.

Bowles then asked to shelve 200 extra tons by thinning down the deck armor. Bradford and Bowles were opposed by Melville which claim a realistic figure of 50 tons was rather expected, and argued that the remaining could be saved by removing 140 tons of coal carried on trials (750 tons versus 900), but this clearly was “trickery”, towards the Congress, as pointed out by a concerned Bowles. And there was model testing, something new, which seemed to prove Bowle’s point. Melville cited British cruisers for comparison and eventually the board agreed on 23,000 indicated horsepower for 22 knots. Once done, USS Tennessee and Washington were submitted, and then approved by Congress under the 1902 Naval Building Program while the next North Carolina and Montana, were approved in 1904, two years later following a trend of a single ship, either a battleship or cruiser, being approved yearly.

Now with the USN at large, while the design being accepted by the Congress were only good news, most in addition concurred that this design did match indeed still their own expectation of that “battle-cruiser” could be. The Tennessees for most, excelled in armament and protection and made these the best design globally at the time, albeit a faction still criticized the issue of speed. The Bureau of Construction and Repair were the most vocal about their inferior speed compared to British or French equivalents. They were answered by Melville in his minority report that:

“I cannot believe that Congress did not intend that these vessels should be equal to or superior to any of their class, that class being armored cruisers, and not battleships where very high speed may not be so essential; and I am not at all certain that an additional knot and the power for it should not have been insisted upon in the first place.”

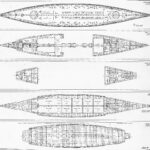

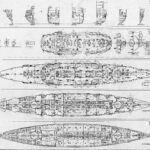

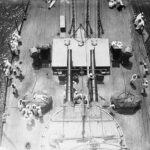

General Layout

The Tennessee and Pennsylvania class were very much near-sisters as ween aboven with a similar overall length at 504 ft 6 in (153.77 m), same hull outlook, flush deck, same pointy stern and moderate ram bow. The draft was about the same at 25 ft (7.6 m) but the beam was superior from 3 ft 1 in (0.94 m) at 72 feet 10 inches (22.20 m). In the end they still displaced only 800 tons more at 14,500 long tons (14,733 t) standard, perfectly at eas with Congress limitations. This traduced into a filly loaded displacement of 15,712 long tons (15,964 tonnes). Model testing however had been instrumental to make the best of the slighty output increase, by giving them much improved underwater lines.

Their extra beam was praised on trials also as they ended extremely steady, with a better metacentric hight, did not bled speed as much as the Pennsylvanias and maintained indeed the same speed at 22 knots with no apparent increase in horsepower. In hevy seas however they were seen pitching rather than rolling in heavy seas but in general, were regarded as good sea boats, with a generous enough freeboard of 18 feet (5.5 m) amidships, 24 feet (7.3 m) forward, 21.5 feet (6.6 m) aft. If their general outlook was nearl identical, the main change was their larger turrets, thus taller, which imposed a conning tower being one deck higher to clear out the roof of “A” turret.

Later appearance in 1912, note the typical corbel mast and extended bridge. She was then painted in medium grey.

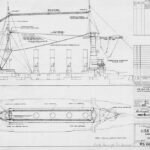

Powerplant

Despite Melville insistence over triple screws, the final design repeated the Pennsylvania’s arrangement of standard twin shafts. They were driven by two four-cylinder vertical triple expansion engines located in separate watertight compartments for protection. They were in turn fed by sixteen Babcock & Wilcox straight water-tube boilers. They were separated into eight watertight compartments, then exhausted by groups of four, into four funnels total. They worked at a steam pressure of 265 psi (1,830 kPa) and 250 psi (1,700 kPa) depending on the models.

The VTE engines has a piston stroke of 48 inches (1.2 m).

The high and low-pressure cylinders had a ratio of 1 to 7.3.

High Pressure; 38.5 inches (980 mm)

Intermediate Pressure: 63.5 inches (1,610 mm)

Low Pressure: 2-74 inches (1,880 mm).

Combined grate surface 1650 square feet

Heating surface 70,940 square feet.

Combined total 23,000 indicated horsepower at 120 revolutions per minute.

Design speed was 22 knots (25 mph; 41 km/h) and they performed better on sea trials making them in two stages, wit a 4-hour run at flank speed and a 24-hour endurance run at the maximum maintainable speed. The best performer was USS North Carolina at 26,038 hp, and 22.48 knots (41.63 km/h) over four hours, but she did less well over 24h at 20.6 knots (38.2 km/h) from 19,802 hp. Tennessee was the best at this latter, maintaning 21,600 hp at 21.28 knots (39.41 km/h) the entire day and night.

They carried eventually the same coal amount (900 tons) as the Pennsylvanias in normal conditions, but with a wartime extension to 2,000 tons, for a range of 6,500 nautical miles at 10 knots and still an appreciable 3,100 nautical miles at full speed run. This was especially precious for any battle line action.

Protection

The Tennessees made a few sacrifices, and yet still they carried a staggering 30% more armor weight than the Pennsylvanias. The US Naval staff were pleased with the fact they can pretend having by far the heaviest, most comprehensive protection of any cruiser… until the 1943 Alaska class. The larger and thicker main turrets and associated barbettes were a great cause for this increase, as well as the global area of side armor coverage, which was extended. Magazines and ammunition supply systems for any caliber were the best protected of any cruiser to that point. Their armored bulkheads enabled a full sibdivision for a full protection of the main battery, with 5 inches (127 mm) of Cemented Krupp armor while thinner spaced received Harvey armor or even untreated nickel steel.

Main waterline belt

It was 5 inches (127 mm) thick amidships. It then tapered down to 3 inches (76 mm) at the ends. Vertically she extended 5 feet (2 m) below the waterline. Above water line there was a 2-inch (51 mm) nickel steel for the gun deck in wake of the 3-inch battery.

Bulkheads

There were same thickness transverse protective bulkheads extending from the gun deck to the armored deck, across the fore and aft ends of the belt armor.

Bulkheads were also placed on the gun deck, up to the 10-inch barbettes, closing the side armour fore and aft between the main and gun decks.

The 6-inch guns on the gun deck received separations of splinter bulkheads of 1.5-inch (38 mm) in nickel steel.

Turrets

Turret armor comprised a face 9 inches (229 mm) thick, 7 inches (178 mm) sides, 5 inches (127 mm) back, 2.5 inches (64 mm) roof.

Their associated barbettes were 7 inches (178 mm) forward, and the armour was decreased down to 4 inches (102 mm) at the back. Below the gun deck, this was also 4 inches, all the way down to below casemates and belt. The 10-inch ammunition tubes were completely protected.

Decks

The Main protective deck was “only” 1.5 inches (38 mm) on flat, but thicker at the slopes at 3 inches (76 mm). This deck extended to the bottom of the belt armor, fore and aft, creating the usual turtledeck. There was also a 30-inch (1 m) cofferdam between the protective and berth decks at both ends with water-repelling material for underwater damage mitigation.

Conning tower

The forward CT was protected by 9 inches (230 mm) walls, and topped by a roof 2 inches (51 mm) thick. There was als a signal tower protected by 5 inches (127 mm).

Subdivision

Below the waterline, protection of boh the Pennsylvanias and Tennessee looked superficially identical, with the same number of transverse bulkheads, but there was just more longitudinal subdivision.

The inner bottom comprised 35 watertight compartments from the keel to the protective deck either side as well as fore and aft, to the knuckle of the keel.

Underwater protection subdivided the entire subsurface hull, up to the lower edge of the armored deck slopes.

There were also a total of twenty-eight electrically operated Long-Arm watertight doors, five armored hatches beneath the armored deck. Displays were in the bridge, and they were remotelly controlled.

Armament

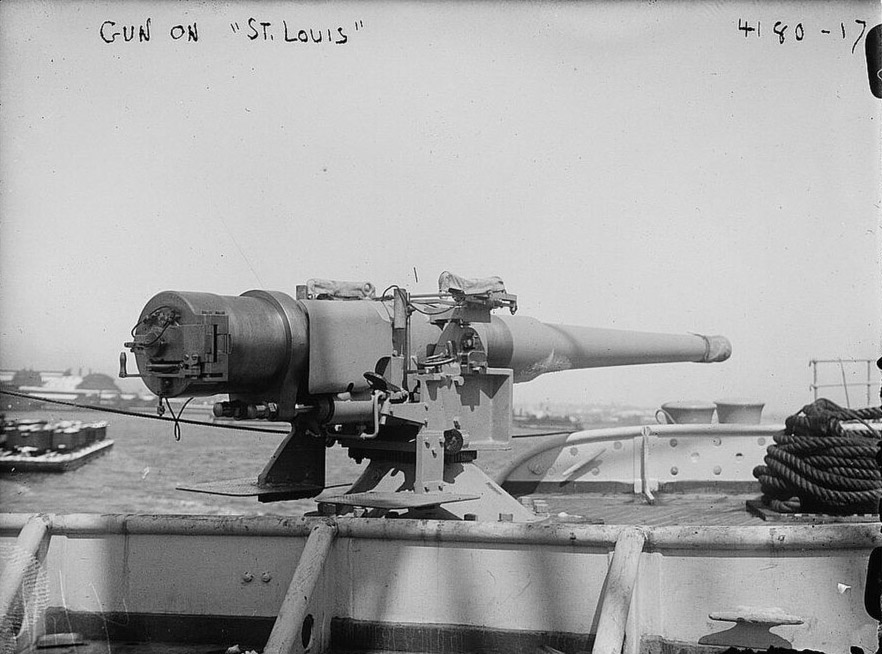

10″/40 caliber Mark 3 guns

These new four 10-inch (254 mm) 40-caliber Mark 3 guns were distributed in two twin turrets fpor and aft, like the Pennsylvanian’s 8-inche turrets. The barbettes were of course larger, and benefited for the extra beam of the design.

The Mark 3 was the last 10-inch gun built of the U.S. Navy. It had an A-tube wuth jacket and locking ring as well as a screw box liner made in nickel steel. The used “smokeless” powders and had a better velocity, flatter trajectory, being more accurate overall, helped by a centralized fire control. In 1908 hrey also obtained new armor-piercing (AP) shells with a 7crh ballistic cap to improve penetration at longer ranges, thus perfect to fit in a battle line.

Their placement was considered more optimal than on the british Duke of Edinburgh, Warrior and Minotaur-class, being very wet in high seas. Being 30 feet (9.1 m) above the waterline, the Tennessees main battery was at an advantage. Their arc of fire was than twice than on broadside guns as well, with an excellent field of view.

Specs 10-in Mark 3*

Weight and size:

Maximum elevation: 14.5°, depress −3°.

Shell: 510-pound (231 kg)

Muzzle velocity: 2,700 feet per second (820 m/s)

Range: 20,000 yards (18,288 m) at 14.5°

Storage: 60 rounds per gun in peacetime, 72 in wartime.

Rate of fire: 2 – 3 rounds per minute.

*Comparison British BL 9.2-inch (233.7 mm): 380-pound (170 kg) shell at 2,643 ft/s (806 m/s), range of 29,200 yd (26,700 m).

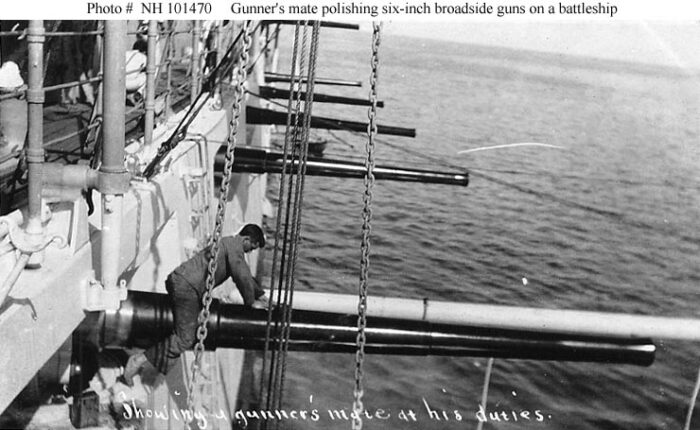

6″/50 caliber Mark 8 guns

These were usually used as secondary guns on standard battleships, from USS Main to USS Montana (Mark 8). They were of the exact calibre 49, not 50. These sixteen 6-inch (152 mm) 50-cal Mark 8 guns had 200 rounds provided per gun.

-Four were on independent, armored casemates (2 in thick) on the main deck

-The remainder were in broadside, gun deck.

All used pedestal mounts. Four could be trained ahead or astern, adding to two 10-inch and four 6-inch. The broadside guns all can be trained over 115° and the sides and did not protruded, as the sides needed to be left unobstructed when going alongside a vessel.

Specs Mark 8

Mass: 18,628 lb (8,450 kg) with breech for 300.2 in (7,630 mm) long, 294 in (7,500 mm) bore (49 calibers) barrel

Shell: 105 lb (48 kg) naval armor-piercing 6 in (152 mm)

Elevation/Traverse: −10° to +15°, −100° to +100°

Rate of fire: 6 rounds per minute

Muzzle velocity: 2,800 ft/s (850 m/s)

Effective range: 15,000 yd (14,000 m) at 14.9° elevation WWI charge

More on navweaps.

3″/50 caliber guns Mk III/V/VI

In all twenty-tow guns, planed on single mountings with the details as follows:

-6 sponsoned on the gun deck

-6 in broadside, gun deck

-10 in broadside, main deck.

Specs Mark 6

Dimensions and Weight: 2,086 pounds (946 kg) with breech, 153.8 inches (3.91 m), barrel 150 inches (380 cm) bore 50 calibres

Shell: Complete 24 lb (11 kg), 13 lb (5.9 kg) projectile: AP, HE, Illumination

Elevation/Traverse: -10° to +15°, 360°

Rate of fire: 15 – 20 rounds per minute

Muzzle velocity: 2,700 ft/s (820 m/s)

Maximum range: 10,000 yd ( m) at 15° elevation

Sights: Peep-site and Optical telescope

47mm/40/45 Driggs-Schroeder Mk I/II

The Tennessee also had a “jungle” of small caliber guns, respectively:

-12x 3-pounder semi-automatic guns

-2x 1-pounder automatic guns

-2x 1-pounder rapid-fire guns

-2x 3-inch field pieces

-2x .30-caliber machine guns

-6x .30-caliber automatic guns.

They were present on the upper deck, bridges and tops, and other planes and left ready at all times even at anchor machine cold to repel a possible night attack of a torpedo boat at anchorage, courtsey of the Port Arthur attack. These guns were deemed enough to savage the crews of incoming torpedo boat and pepper the superstructures of an an enemy ship if close enough. They all fired HE rounds. The 3 and 1-pounded were licenced Hotchkiss, with their brass cartridges with fixed projectiles manufactured by the American Ordnance Company in Bridgeport, Connecticut and others by Driggs Ordnance Company. The field piece, and eight machine guns were intended for landing parties. Add to a small arms hold an average of 200 sailors could be armes with rifles, the officers with pistols and sabres. This was a serious proposition for any international event, a deterrent when protetion nationals in countries where law and order was in jeopardy.

Modifications

Before even North Carolina was laid down BuC&R made design alteration given the gap of a full year in experience and reports from the Russo-Japanese War, namely:

-Main traverse bulkheads unpierced below the armored deck, and rearranged.

-Barbettes increased 1 inch (25 mm) on exposed surfaces.

-Deck armor over the magazines thickened from 40 to 60 pounds (27 kg).

-Side armor abeam reduced.

-Magazines rearranged for 20% more main and secondary ammunition.

-Berth and gun decks relocated amidships: New increase of coal 200 tons.

-Coal bunkers modified to allow trimming from the upper bunkers to the fire rooms.

-Cellulose omitted as water-excluding material.

During service, refits tended to be lighter than on the Pennsylvanias, with Tennessees features retrofitted like the automatic ammunition hoist structures, longitudinal turret bulkheads and the power plants were more standardized, the Pennsylvanian dropping Niclausse for all Babcock & Wilcox boilers. The major external change was about their pole masts fore and aft, replaced by corbel-style lattice masts forward. The bridge was also modernized and partly rebuilt, extended from 1912.

By January 1917 USS Seattle (ex- Washington) was the first experimentally fitted with a seaplane catapult. Montana was scheduled to receive one, but this came. The catapult however was too sensitive for an use of the aft main guns so the program was cancelled, the catapult removed even before April 1917.

In later 1917 or 1918, the 6-inch and 3-inch armament was removed and all ports sealed, with these ordnances being reinstalled on merchant ships and auxiliaries. This was also to improve watertightness in the North Atlantic.

Illustration of the USS Tennessee in 1914.

⚙ Tennessee class specs. |

|

| Displacement | 14,500lt standard, 15,712 long tons (15,964 t) tons FL |

| Dimensions | 504 ft 6 in x 72ft 10 in x 25 ft (153.8 x 22.2 x 7.6 m) |

| Propulsion | 2 shafts VTE, 16 × Babcock & Wilcox boilers: 23,000 ihp (17,150 kW) |

| Speed | 22 knots (41 km/h; 25 mph) |

| Range | 6,500 nm at 10 knots |

| Armament | 4× 10 in/40, 16× 6 in/50, 22 ×3 in/50, 12× 3-pdr, 4× 21 in TTs |

| Protection | Waterline belt 3–5 in, deck 1.5–4 in, CT 9 in, Turrets 2.5–9 in |

| Crew | 887 officers and enlisted |

The Tennessee class in action

USS Tennessee, later Memphis (ACR-10)

USS Tennessee, later Memphis (ACR-10)

USS Tennessee (ACR-10) was laid down at Cramp on 9 February 1903, launched on 3 December 1904 and completed on 17 July 1906 at Philadelphia Navy Yard under Captain Albert Gleaves Berry in command. She departed Hampton Roads on 8 November 1906 as escort for SS Louisiana carrying President Theodore Roosevelt for a cruise to Panama, checking work on the Canal. She stopped at Puerto Rico when back and reached Hampton Roads on 26 November. After fixes at the yard, she left Hampton Roads agaon on 16 April 1907 for the Jamestown Exposition (7-11 June 1907) and the tricentennial of the first english settlement in North America. On 14 June she sailed for Europe with USS Washington, arrived at Royan, France (23rd) with the Special Service Squadron and back in August. She left Hampton Roads on 12 October for the Pacific by rounding the cape, and became flagship for the second division, Pacific Fleet.

While off California on 5 June 1908 she suffered a boiler tube explosion (7 killed) while at full speed just after the rear admiral tour of inspection. Thanks to the good sub-division, she could return to port without a hitch. Later she sailed for Samoa, Pago Pago, arriving on 23 September and by 15 May 1910, was at Bahía Blanca to represent the US for the independence celebration anniversary of Argentina.

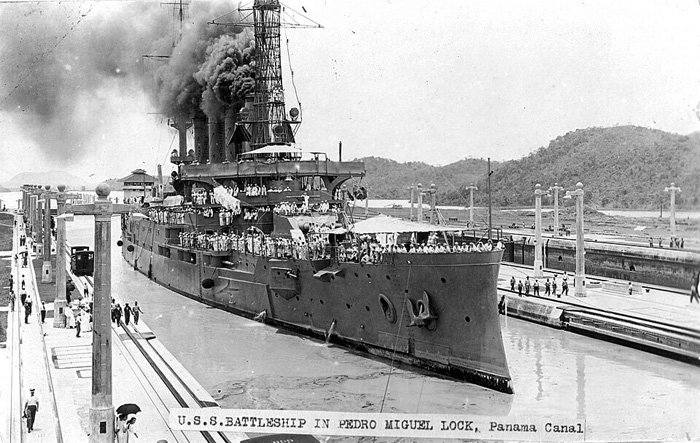

On 8 November 1910 she departed Portsmouth for Charleston and carry Pdt. William Howard Taft for a trip to Panama, also to inspect work on the canal, then back to Hampton Roads on 22 November. Next she was seen in battle practice off the Virginia coast until February 1911 and had te crew released for Mardi Gras in New Orleans, then stopped in New York City early in March and sailed for Cuban and Guantanamo Bay.

When back home on 15 June 1911 at Portsmouth Navy Yard she was placed in reserve for 18 months. She later left Philadelphia on 12 November 1912 for the Mediterranean, Smyrna to protect American citizens and property (First Balkan War) until 3 May 1913. She remained on the East Coast and joined the Atlantic Reserve Fleet, Philadelphia on 23 October. On 2 May 1914, she was receiving ship at the New York Navy Yard. On 4 November she returned to the mediterranean, Beirut (Syria) to protect the Christian population from Syrian Muslims.

On 6 August 1914 she sailed from New York to Europe and back until February 1915 notably for the American Relief Expedition, carrying gold bullion and American refugees as well as the 1st Regiment, Marine Expeditionary Force and Marine Artillery Battalion to Haiti in August 1915, and from 28 January to 24 February 1916 she became flagship of the squadron off Port-au-Prince. By March 1916 she made a cruise to Montevideo with dignitaries.

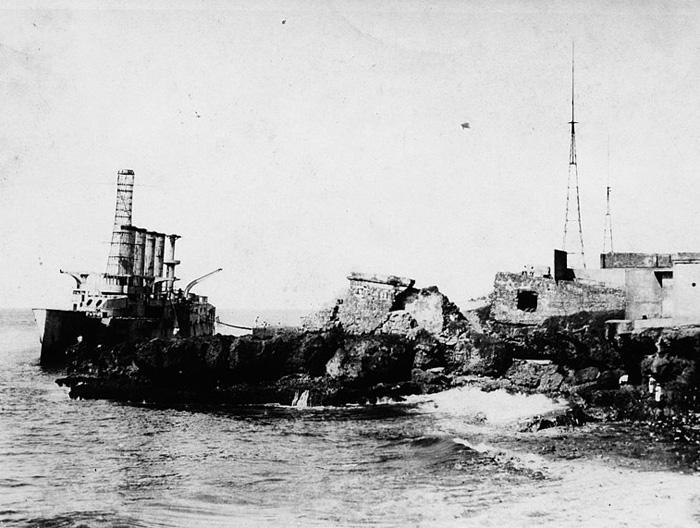

On 25 May she was renamed USS Memphis to free the name for BB-43.

In July 1916, Captain Edward L. Beach, Sr. too command and she sailed for the Caribbean, Santo Domingo, on 23 July, for a patrol as the Dominican Republic was in turmoil. She was at anchor just 0.5 nautical miles (0.58 mi; 930 m) off a rocky beach over 45 ft (14 m) of water in Santo Domingo harbor on the afternoon of 29 August 1916 with just two boilers operating and not far away was the gunboat Castine. After 12:00, Memphis started began to roll heavily as an unexpected heavy swell was just developing so captain beach ordered to raise steam, and signalled to Castine, which did the same. Memphis planned her departure for 16:35, but conditions deteriorated so much that by 15:45 Memphis spotted a 75 ft (23 m) wave of yellow water barring the horizon. At 16:00, it turn ochre and rose to 100 ft (30 m) tall, and Memphis started to rolling to 45° with masses of seawater water cascading insde via her open gun ports and the ventilators, which entry point was 50 ft (15 m) above the waterline. At 16:25, as she did not redressed, water gushed inside via the funnels, putting out all boilers.

Without steam she could not move. She then was tossed on the rocky harbor bottom at 16:40. Her propellers were tirned off, and her engines completely lost pressure just as the giant wave arrived on Memphis. As water started t be sucked in, she “fell” down into her deepest point, only to be hut by three massive waves in rapid succession, with the crew estimating the first was around 70 ft (21 m). It tores itse way insdide and washing crewmen overboard. She completely rolled, struck the harbor bottom, and was pushed to the beach close away but started drifting again and by 17:00, was tossed against the cliffs along the coast while resting on the bottom. In 90 minutes she was wrecked, whereas Castine, whch could raise steam faster, managed to reach safe waters and was further at sea to ride the large waves, albeit being damaged by and close to capsizing herself.

Without steam she could not move. She then was tossed on the rocky harbor bottom at 16:40. Her propellers were tirned off, and her engines completely lost pressure just as the giant wave arrived on Memphis. As water started t be sucked in, she “fell” down into her deepest point, only to be hut by three massive waves in rapid succession, with the crew estimating the first was around 70 ft (21 m). It tores itse way insdide and washing crewmen overboard. She completely rolled, struck the harbor bottom, and was pushed to the beach close away but started drifting again and by 17:00, was tossed against the cliffs along the coast while resting on the bottom. In 90 minutes she was wrecked, whereas Castine, whch could raise steam faster, managed to reach safe waters and was further at sea to ride the large waves, albeit being damaged by and close to capsizing herself.

In total she lost 43 men, dead or missing with ten washed overboard or killed by steam bursting out, 25 lost in her motor launch while back from leave, caught by the waves and rolle over, and then eight more in three boatsafter dark, trying to reach shore plus 204 badly injured. Chief Machinist’s Mate George William Rud, Lieutenant Claud Ashton Jones, and Machinist Charles H. Willey were all awarded the Medal of Honor for their effort to save other men, trapped for the most.

Albeit Tsunamis at the time were not unheard of, this looked as freak accident that could have cause a much greater toll. As Captain Beach’s son, Edward L. Beach Jr. reported his father’s memoirs of the incident, he precised the perception from the ship’s bridge was of a tsunami exceeding 100 ft (30 m) in height, but recent research reports there was no seismic event recorder in the whole area on 29 August 1916 and now it is described rather as a wind-generated ocean wave and possibly a rogue wave. Also there were three hurricanes active in the Caribbean. Whatever the exact cause, the death toll would have been much greater if that was not for the equally heroic efforts of the Dominicas themselves to rescue the survivors, despite the fact their country was occupied fpr eight years by hte Marines. The cruiser’s wreck later became a symbol of imperialism.

Indeed the cruiser remained upright and only in appearance, relatively undamaged above the waterline. After careful examination it was estimated she was not worth repairing. The Department of the Navy assigned men from the USS New Hampshire and wrecking vessel Henlopen to remove her guns, supplies and equipment. Her bell was presented to a local church as a gesture for the rescue.

She was struck on 17 December 1917, sold to the A. H. Radetsky Iron and Metal Co., from Denver on 17 January 1922 and gradually scrapped on site, with another effort made by President F.D. Roosevelt, which insisted to completely remove what was left, a work completed in 1937.

USS Washington, Seattle (ACR-11)

USS Washington, Seattle (ACR-11)

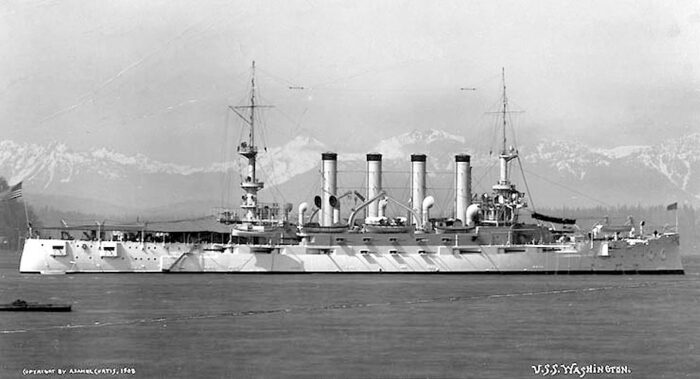

USS Washington off Seattle, north pacific coast, winter 1908.

USS Washington (ACR-11) was laid down on 10 February 1903 at New York Shipbuilding Corporation, Camden, New Jersey, launched on 18 March 1905 and completed on 7 August 1906 at a cost of $4,035,000, the contract price of hull and machinery. Under Captain James D. Adams in command, she was fitted out at Philadelphia until 1st November 1906 and proceeded to Hampton roads, and then departed as escort for SS Louisiana with her sister Tennessee (see above). This visit included Piney Point in Maryland, Colón in Panama, Chiriquí Lagoon and the Mona Passage.

She was back at Philadelphia Navy Yard on 11 December for many fixes until the spring of 1907.

She left League Island on 11 April for Hampton Roads the next day, took part in the Jamestown Exposition and spent time later between docking and tests at the New York Navy Yard before heading in late June for Tompkinsville (Staten Island) and on 5 June back to Hampton Roads and back at the Jamestown Exposition. On 11 June she headed for Newport to join Tennessee and crossed the Atlantic on the 14th to Royan, Île-d’Aix, La Pallice, Brest in France (23 June-25 July) and back to Tompkinsville to run speed trials.

After some more yard work at NyNyd she sailed for the Pacific Station with Tennessee via Hampton Roads, Port of Spain in Trinidad, and then stopped at Rio de Janeiro, Montevideo, rounded the cape, Punta Arenas, Callao, Acapulco, Pichilinque Bay, right in time to join fire target practices in Magdalena Bay still in Mexican waters from late December 1907 to January 1908. She went in independent tactical exercises until March, and operated off Santa Barbara, San Francisco, San Diego, San Pedro, into the summer 1908, visiting Redondo Beach, Venice, Monterey, and Angel Island, Port Townsend, Port Angeles, Seattle, Tacoma, and Bremerton to the north. She was also reviewed by the Secretary of the Navy at San Francisco on 6-17 May.

USS Washington operated off the west coast and then was prepared to sail with the Armored Cruiser Squadron in the Far East, leaving San Francisco on 5 September 1909, stopped at Honolulu 10-20 September, Nares Harbor (Admiralty Islands) to recoal on 17-25 October, and Manila, Philippines, on 30 October, then Woosung (near Shanghai) 14-30 December 1909 and Yokohama (3-20 January 1910) then back to Honolulu (31 January-8 February) and California, San Francisco, then Bremerton on 3 March for fixes and maintenance from 21 March. She remained on the West Coast until the autumn of 1910, and was prepared in San Francisco for her next deployment, leaving on 14 August for South America, rounding the cape again to the east coast and the Atlantic Fleet leaving also the 1st Division of the Pacific Flee.

In Valparaíso she took part in Chilean Centennial Celebration (10-23 September), then Talcahauano and Punta Arenas, Rio de Janeiro, Carlisle Bay, St. Thomas, Culebra, and target practice with the Fleet. Next was Hampton Roads and Lynnhaven Bay and maintenance at Norfolk (20 December 1910-2 January 1911), then an overhaul at Portsmouth before sailing with stores and material for the 5th Division in Cuban waters, Guantánamo Bay on 20 March followed y exercises. Next she was back via Hampton Roads in June to New York. Sje continued to operate off the northeastern seaboard until the summer of 1911 with exercises and maneuvers ranging from Cape Cod Bay to Hampton Roads. She also cruised briefly with the Naval Militia on 19-21 July and as a reference ship for torpedo practice off Sandwich Island as well as Cape Cod on 2 August and battle practice at the southern drill grounds. In November she was reviewed by President William Howard Taft and later took part in a search problem out of Newport on 9-18 November, then sailed for the the West Indies with her sister USS North Carolina and back to Hampton Roads, drydocked at Norfolk wit her crew on leave for Christmas 1911.

After exercises at Guantánamo Bay between late January and early February 1912 she returned to Norfolk on 13-19 February, being prepared (new accomodations) to host Secretary of State Philander C. Knox and his party to Key West to embarked him on 23 February to Colón, Panama and stopping in Costa Rica, Guatemala, Venezuela, St. Thomas, Venezuela, Haiti, Jamaica and Havana in Cuban the diembarking his party at Piney Point in Maryland on 16 April. She later became temporary flagship for CiC Atlantic Fleet at the Philadelphia Navy Yard, 19 April-3 May and headed via New York to Portsmouth to be seen by the Board of Inspection and Survey, also hosting Rear Admiral Hugo Osterhaus (CiC Atlantic Fleet) on 26 May. In Hampton Roads she embarked a detachment of Marines on 27 May and stores for Key West as President Taft concentrated a strong naval force for a possible action in Cuba.

By the late spring and early summer there was a rebellion on Cuba and a USN show of force. On 10 June she was in Havana and remained there until the rebellion was put down. In Hampton Roads she discharged her marines and equipment and was placed in “1st reserve” at Portsmouth on 9 July until 8 October. In New York she took part in the Naval Review of 10-15 October and was back at Portsmouth on 17 October, then New York, Tompkinsville, and became a receiving ship from 20 July 1913.

Full recommission on 23 April 1914 under Captain Edward W. Eberle she took on men from Norfolk and Port Royal, in April-2 May headed for Key West and Santo Domingo. She was present when there was unrest in the Dominican Republic, she was chosen to “show the flag” there from Key West on 4 May, in Puerto Plata on 6 May to protect American interests joining the gunboat USS Petrel. Captain Eberle invited representatives of both the insurgents and government force to settle their different but this failed. She departed Puerto Plata on 6 June, replaced by USS Machias. In June she was in Veracruz, Mexico and remained in Mexican waters on 14-24, then moved to Haiti, to protect American interests there into July.

However the situation degraded further and USS Washington returned to Puerto Plata on 9 July, staying there until the autumn (hearing about the war breaking out in the meantime in Europe). She brough a commission headed by John Franklin Fort (former governor of New Jersey) and James M. Sullivan, minister to Santo Domingo and a lawyer, Charles Smith, to mediate a peace. Both sides accepted the establishment of a constitutional government and elections under US observation. Due to post-election unrest she landed additional Marines to Santo Domingo but was soon back to Philadelphia on 24 November and became flagship of the Cruiser Squadron, before being overhauled at Portsmouth from 12 December 1914.

On 11 January 1915 she headed for Boston, took on ammunition, sailed to Hampton Roads on 14 January., completed stores and provisions to land an expeditionary force of Marines to Haiti for the third intervention of January 1915 led General Vilbrun Guillaume Sam. She was the flagship of Rear Admiral William B. Caperton, under command of Captain Edward L. Beach Sr. She stayed in port there until the 26th and moved to Port-au-Prince on 27 January and left for Mexican waters. After exercises and drills she took coal at Guantánamo and returnd for Cap-Haïtien.

But seen she was redirected to Port-au-Prince by order of Secretary of State, Robert Lansing as President Sam was besieged in the presidential palace. He was later caught and killed by a mob.

Washington was at Port-au-Prince that day and Admiral Caperton ordered marines and a landing force ashore to protect American interests and those of other foreign nations staying there all the winter. On 12 August there was a new president, recognized by the US on 17 September so she departed on 31 January 1916 for Guantánamo, transferred passengers and stores, as well as Marines at Norfolk and arrived at Hampton Roads, New York and Boston, then Portsmouth for an overhaul until March, and placed in reserve.

She was renamed “USS Seattle” on 9 November 1916, freed for BB-47, and recommissioned as flagship, Destroyer Force from 6 April 1917, fitted out at New York on 3 June and leaving on the 14th as escort for the first US convoy to European waters, and flagship for RADM Albert Gleaves. On 22 June she reported a ubmarine whe her helm jammed, sheering out of formation and sounding her whistle to warn other ships in the convoy. Lookouts noted a white streak at 50 yd (46 m) ahead from starboard to port. Admiral Gleaves was asleep in the charthouse at the time, and was awoken to see the captain orderinf the gun crews at their weapon stations while the transport De Kalb fired on the surfaced U-boat, soon attacked by the destroyer USS Wilkes attacked. There were two U-Boats waiting in ambush of the first American expeditionary forces, but this was unsuccessful, partly due to the cruiser’s jamming and alert given on all ships, manoeuvernbg unexpectedly to avoid collision. She went on with uneventful escort missions, ending in New York on 27 October 1918.

Post-armistice she received extra accommodations to bring back doughboys from France until 5 July 1919. She was transferred afterwards to the Pacific Fleet, was reviewed by President Woodrow Wilson on 12 September at Seattle, moved to Puget Sound in reduced commission, reclassified CA-11 in July 1920. Fully recommissioned on 1 March 1923 under Captain George L. P. Stone she became flagship CiC for the entire USN for four years, hosting Admirals Hilary P. Jones, Robert Coontz, Samuel S. Robison, Charles F. Hughes. operated from Seattle to Hawaii, from Panama to Australia. Back to the Atlantic in June 1927 had a another fleet review at Seattle (Pdr Calvin Coolidge) on 3 June. She returned to the east coast, New York on 29 August as receiving ship. On 1 July 1931 she was “unclassified” and acted as floating barrack until WW2 for the 3rd Naval District, providing men for tugs and other district craft or naval escorts for patriotic functions while crews were housed and trained for ships preparing to go into commission, such as the Brooklyn class cruiser USS Honolulu. On 17 February 1941 she became IX-39, still a receiving ship until decommissioned on 28 June 1946, struck on 19 July, sold for BU on 3 December.

USS North Carolina, Charlotte (ACR-12)

USS North Carolina, Charlotte (ACR-12)

USS North Carolina (ACR-12) was laid down at Newport News Drydock & Shipbuilding Co., Newport News, Virginia on 21 March 1905, launched on 6 October 1906 and completed on 7 May 1908. She started her shakedown cruise along the eastern coast and to the Caribbean Sea and also hosted for a cruise President-elect William Howard Taft down to the Panama Canal, see the progress in construction from January to February 1909. From 23 April she sailed for a cruise in the Mediterranean and to the eastern part, protecting US Citizens in the Ottoman Empire, with unrest notabl at Adana on 17 May. She sent even a landing party ashore, notably to provide medical aid to sick and wounded Armenians attacked and massacred. She also landed food, water, and other supplies and resumed her patrol in the eastern Mediterranean, back home on 3 August.

For the next eight years she had training exercises in the Atlantic-Caribbean, visiting other countries to show the flag, and represented the US at Argentina’s centennial celebration of independence (May-June 1910) and Venezuela’s centennial (June-July 1911) before hosting the Secretary of War, Henry L. Stimson to the Caribbean via Puerto Rico, Santo Domingo, Cuba, Panama Canal this summer and sent in New York City with the remains of a sailor from Maine for rebuerial after the 1898 explosion. In October she was in maintenance at Portsmouth and until the war broke out not much else is to report.

On 7 August 1914, she sailed on patrol in the Mediterranean to protect citizens notably at Jaffa, Beirut, Alexandria and was back to Boston on 18 June for an overhaul. Next she sailed for Pensacola on 9 September, for early experiments with naval aviation, being the first US ships fitted wth a catapult, and launching a Benoist seaplane on 5 November. The catapult was removed afterwards, but tests were positive. From 6 April 1917, North Carolina was an escort for troopships between Norfolk and New York and by December 1918, she started to escort repatriation ships and carried herself troops after the installation of extra accomodations, making two trips with the men of the American Expeditionary Force, her final run ending on July 1919. By 7 June 1920, she was renamed Charlotte, freeing her name for a South Dakota-class battleship. She saw little activity afterwards and was decommissioned on 18 February 1921 at Puget Sound Navy (Pacific coast). She was stricken on 15 July 1930 and was sold for BU on 29 September.

USS Montana, Missoula (ACR-13)

USS Montana, Missoula (ACR-13)

USS Montana (ACR-13) was laid down at Newport News on 29 April 1905, launched on 15 December 1906 and completed on 21 July 1908. She was assigned to the Atlantic Fleet, transferred to Norfol, and left on 5 August for an eastern coast training cruise until 25 January 1909. On 8 October 1908 she took part in fireworks display at Philadelphia with her searchlights, but one blinded an operator of Philadelphia Police Department steamer “Visitor”, colliding with a barge on which there was a fire due to malfunctioning fireworks. Next she was sent to the Caribbean Sea, Colón, Panama on 29 January and the Special Service Squadron. In February she was sent back to Hampton Roads, to greet the Great White Fleet completing its circumnavigation. In April she was dspipatched again to the Eastern med due to the Young Turk Revolution, threatening American interests. She remained there until 23 July and left Gibraltar for Boston on 3 August. Next she resumed her eastern coast patrols.

She left Hampton Roads on 8 April 1910 for South America (Argentina Centennial with USS North Carolina) and was in Maldonado, Uruguay to meet their sisters USS Tennessee and the South Dakota to Bahía Blanca in Argentina, for these centennial celebrations. All four cruisers never had been united before, or after and this made quite an impression. They left Argentina on 30 June, back to Hampton Roads on 22 July. She then ecorted Pdt. William Howard Taft to Panama from 10 November for the visit. On 26 July 1911 she was transferred to the Atlantic Reserve and started an overhaul at Portsmouth until 11 November 1912.

By December 1912 she returned to the eastern Mediterranean and joined Tennessee to protect US citizens after the start of the Balkan Wars, under Rear Admiral Austin M. Knight. Until June 1913, she visited Beirut, İskenderun, and Mersin. Back home she resumed training cruises on the east coast, as well as Mexico, Cuba, and Haiti. With Montana and the SMS Vineta in close supprt, she landed marines in Port-au-Prince. On 28 April and early May she took part in the occupation of Veracruz with her captain, Louis McCoy Nulton, leading the landing party. She then carried the remains on 17 sailors and marines KiA back to New York City, on 10 May for ceremony attended by President Woodrow Wilson and SecNav. Josephus Daniels.

After 6 April 1917, she carried men and materiel in the York River before training and on 17 July, joined the Cruiser and Transport Force, making troop convoy runs in 1917-1918 between Hampton Roads, New York City, and Halifax to France, notably on 6 August 1917. In early 1918 she was used as training ship for naval cadets in the Chesapeake Bay. By June 1918 she sailed in eccort with South Dakota and Huntington, DDs Gregory and Fairfax and the Italian steamers Re d’Italia, Caserta, and Duca d’Aosta, French Patria, and US transports Pocahontas and Susquehanna.

In September 1918 she was in another convoy with the battleship USS Georgia, her sister North Carolina, and DD Rathburne for the transports Princess Matoika, President Grant, Mongolia, Rijndam, Wilhelmina, British Ascanius. In October she joined USS Nebraska to escort twelve British merchant ships for Liverpool. In November she return to France to started repatriation, carrying troops herself back home until March 1919. On 5 March she left New York with the passenger ship SS George Washington carrying Wilson back to France. By July 1919, she completed six round trips and 8,800 soldiers.

She was sent to the west coast, Puget Sound on 16 August, an remained until 2 February 1921, decommissioned. Renamed Missoula on 7 June 1920 to free her name for a South Dakota-class battleship in construction, she was decommissioned in 1921, but remained listed until 15 July 1930, formally stricken due to the London Naval Treaty and sold for BU on 29 September 1935.

Read More:

Books:

Gardiner, Robert; Chesneau, Roger (1979) Conway’s all the world’s fighting ships 1860-1905 New York: Mayflower Books.

Jane’s Fighting Ships of World War I. London

Bauer, K. Jack; Roberts, Stephen S. (1991). Register of Ships of the U.S. Navy, 1775–1990: Major Combatants. Greenwood Press.

Friedman, Norman (1984). U.S. Cruisers: An Illustrated Design History. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press.

“The Tennessee Accident”. Service Items. The Navy. Washington DC: Navy Publishing Company. June 1908.

Brassey, Thomas Allnutt, ed. (2011). Brassey’s annual: the armed forces year-book, Volume 1901. Nabu Press. hdl:2027/mdp.39015036624735. ISBN 978-1-248-25595-7. ISSN 0068-0702. LCCN 12030905. OCLC 1537003.

Brown, David K. (2003). The Grand Fleet: Warship Design and Development 1906–1922 (reprint of the 1999 ed.) Caxton Editions

Burr, Lawrence (2008). US Cruisers 1883–1904: The Birth of the Steel Navy. London, UK: Osprey Publishing.

Cooper, Michael L. (2009). Theodore Roosevelt: A Twentieth-century Life. New York, NY: Viking Press.

Dalton, Kathleen (2002). Theodore Roosevelt: A Strenuous Life. New York, NY: Vintage Books.

Dunlap, John Robertson; Going, Charles B.; Suplee, Henry Harrison, eds. (December 1902). “The Speed of Armored Cruisers” (pdf).

Evans, David C.; Peattie, Mark R. (1997). Kaigun: Strategy, Tactics, and Technology in the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1887-1941. NIP.

Friedman, Norman (1984). US Cruisers: An Illustrated History. NIP.

Hogg, Ian V.; Thurston, L.F. (1972). British Artillery Weapons & Ammunition 1914–1918. London, UK: Ian Allan.

Hovgaard, William (1905). “The Cruiser”. Transactions: The Society of Naval Architects and Marine Engineers.

Kenney, Lewis Hobart (February 1906). “U.S. Armored Cruiser Tennessee” (pdf). Journal of the American Society of Naval Engineers. XVIII

Lambert, Nicholas A. (2002). Sir John Fisher’s Naval Revolution. Studies in Maritime History. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press.

Leyland, John (November 29, 1902). “The Seapower of the Nations” (pdf). Navy and Army Illustrated. XV (304). Lopndon, UK: Hudson & Kearns: 259–260.

Marolda, Edward J. (2001). Theodore Roosevelt, the U.S. Navy, and the Spanish–American War. The World of the Roosevelts. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan US.

Morison, Samuel Loring; Polmar, Norman (2003). The American Battleship. St. Paul, MN: MBI.

Musicant, Ivan (1985). U.S. Armored Cruisers: A Design and Operational History. NIP.

O’Brien, Phillips Payson (2007). Technology and Naval Combat in the Twentieth Century and Beyond. Cass Series: Naval Policy and History Series.

Osborne, Eric W. (2004). Cruisers and Battle Cruisers: An Illustrated History of Their Impact. Weapons and Warfare. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO.

Roberts, Stephen S. (2021). French Warships in the Age of Steam, 1859-1914: Design, Contruction, Careers and Fates (1st ed.). Barnsley, UK: Seaforth Publishing.

Ropp, Theodore (1987). Roberts, Stephen S. (ed.). The Development of a Modern Navy: French Naval Policy, 1871–1904. NIP.

Symonds, Craig L.; Clipson, William J.; United States Naval Institute (1995). The Naval Institute Historical Atlas of the U.S. Navy.

“Our New Armored Cruisers” (pdf). The Navy. II (7). New York, NY: Navy Publishing Company: 5. July 1908.

Links:

“U.S.S. Pennsylvania: Class of Eight Armored Cruisers (1905)”. cityofart.com. 23 January 2010. Archived from the original on 4 January 2011.

“Montana I (Armored Cruiser No. 13)”. DANFS. Naval History and Heritage Command. 4 February 2004.

“North Carolina II (Armored Cruiser No. 12)”. DANFS. Naval History and Heritage Command. 9 January 2004. Retrieved 22 April 2012.

“USS Tennessee (Armored Cruiser # 10), 1906-1916. Renamed Memphis in May 1916”. DANFS. Naval History and Heritage Command. 4 February 2004.

“Washington VII (Armored Cruiser No. 11)”. DANFS. Naval History and Heritage Command. 4 February 2004.

DiGiulian, Tony (26 December 2008). “USA 10″/40 (25.4 cm) Mark 3”. NavWeaps.com. Tony DiGiulian.

DiGiulian, Tony (3 November 2011). “United States of America 6″/50 (15.2 cm) Mark 6 and Mark 8”.

DiGiulian, Tony (12 February 2012). “United States of America 3″/50 (7.62 cm) Marks 2, 3, 5, 6 and 8”.

Pike, John (January 1, 1970). “ACR-10 Tennessee / CA-10 Memphis”. GlobalSecurity.org.

navypedia.org/

youtube.com drachinfels video

on worldnavalships.com/

commons.wikimedia.org/

commons.wikimedia.org full set of blueprints

colorized photos USN irootoko JR

en.wikipedia.org Tennessee-class_cruiser

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign