The only cold war battleships in activity

This post must be seen in complement to the origins and WW2 service of the class.

The Iowa class had the shortest career of all USN battleships in WW2 (except the unfortunate two dreadnoughts sunk at Pearl Harbor). They were completed gradually until mid-1944, starting with USS Iowa “the big stick”, on 22 February 1943. With her sister New Jersey, she saw most of the fight in the Pacific until its conclusion, her two other sisters Missouri and Wisconsins commissioned in April-June 1944 saw after months of training and preparation less intense action, apart the growing threat of Kamikaze. The four sisters arrived too late to experience surface combat, something they had been tailored to achieve in a big way, but were found as Fast Carrier Fleet most potent escorts, detached for shore bombardment missions and put in good use their formidable AA defence like a last-ditch umbrella over the fleet.

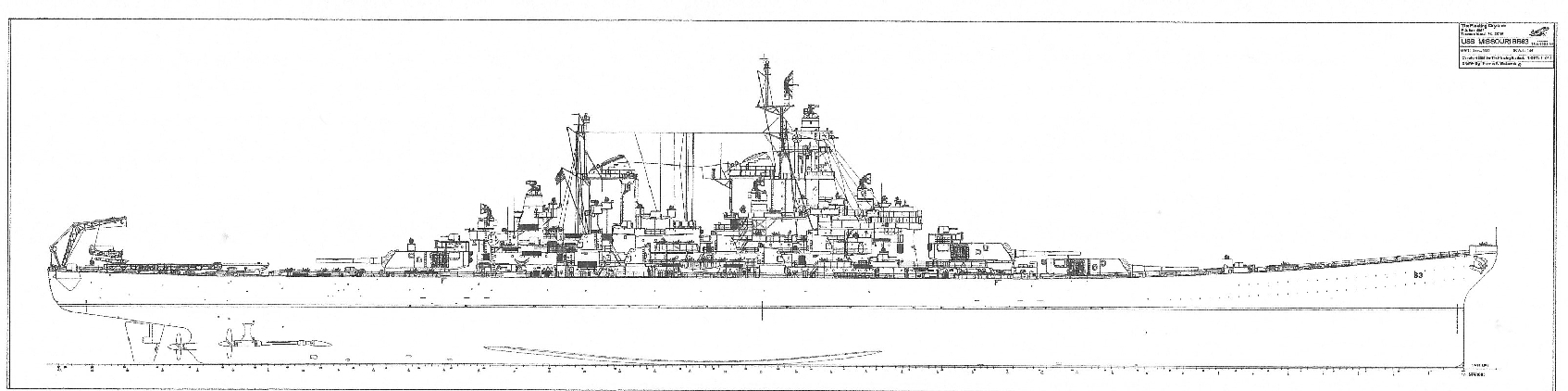

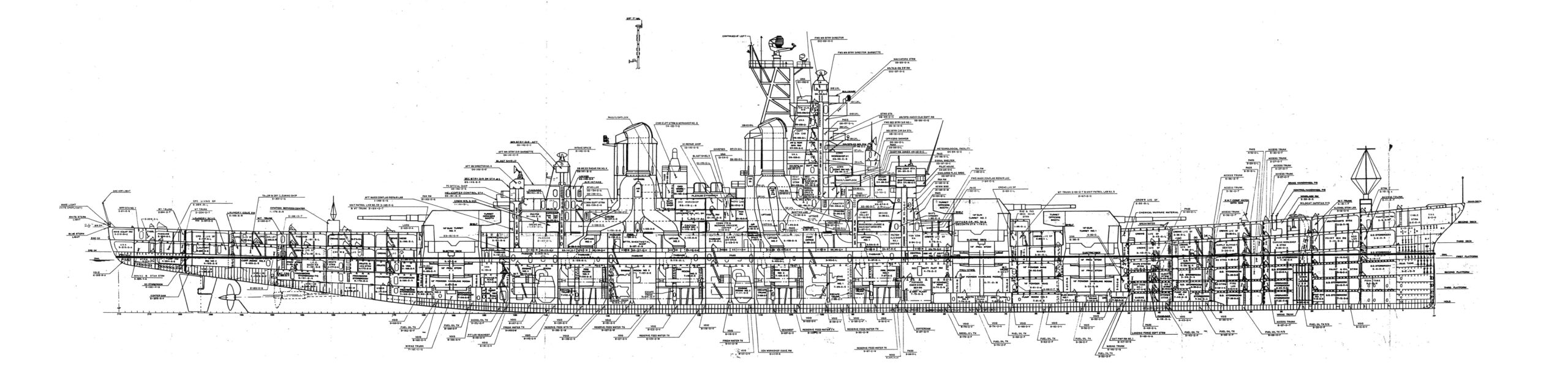

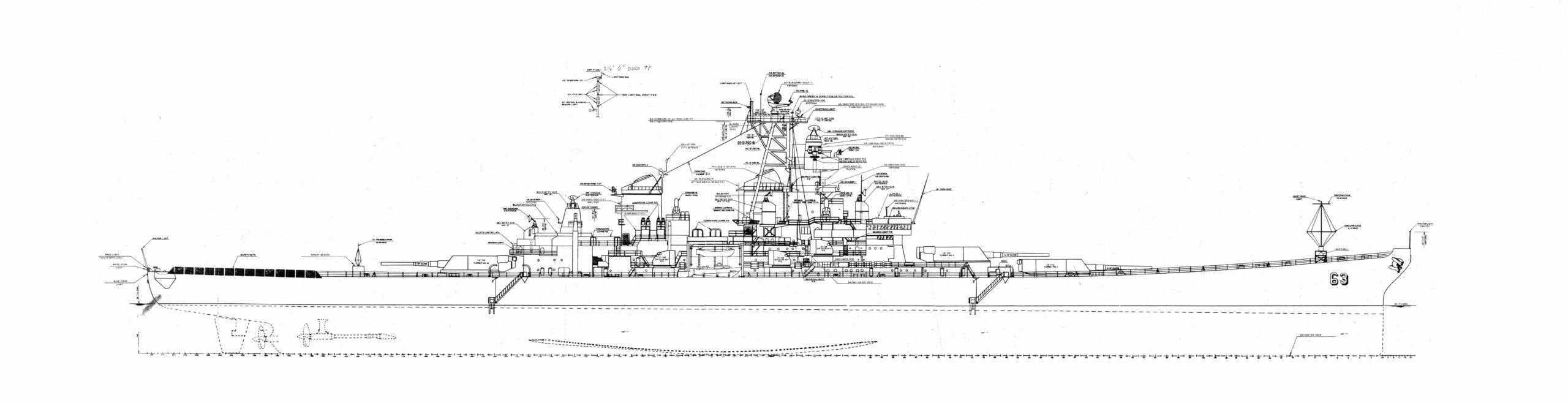

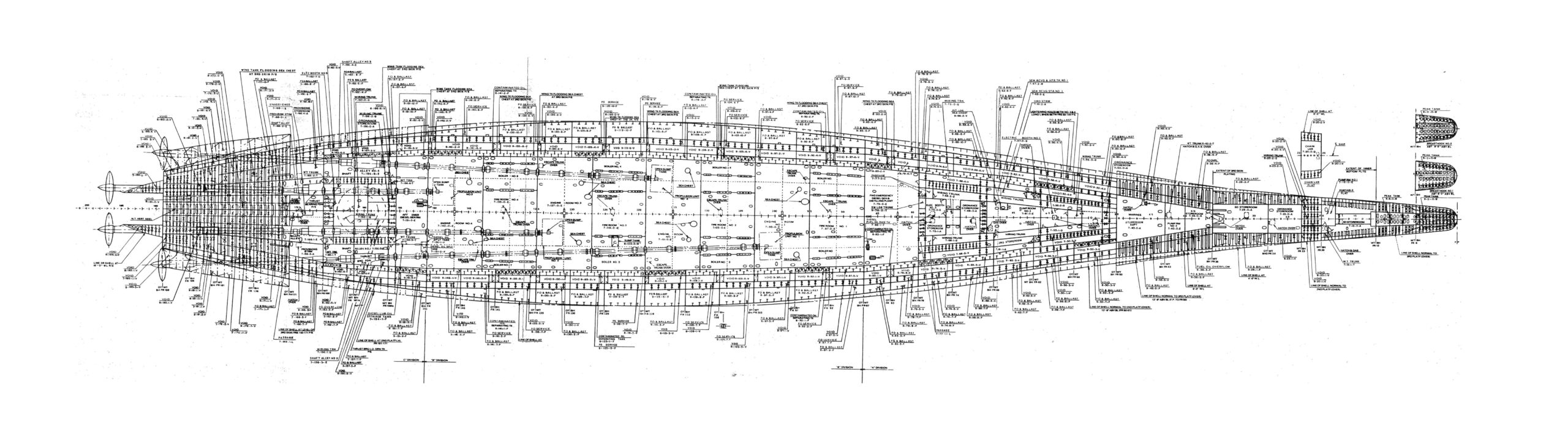

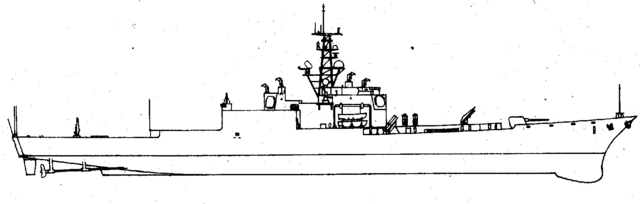

USS Missouri BB-63 original blueprint

At the end of the war, the four veterans had been honored by many awards, nine for USS Iowa, same for “Big J” (New Jersey), three for “mighty Mo” (Missouri), and five for “big wisky” (Wisconsin). If this was not impressive enough, they woould earn many more, and over a period most in the naval staff would have considered insane. Nobody could predict, as in 1945 nobody could seriously deny what was the new king of the seas (the aircraft carrier), and were counting the months before the last battleship would be scrapped. The four battleships had different fates right after the war ended, but coherent with the missions of the rest of the fleet in this winter 1945: They stayed in the Pacific for occupation duties.

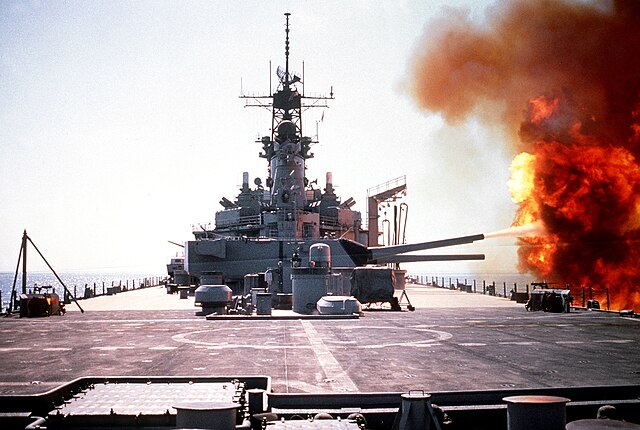

Raw power: Bow view of the Iowa Class USS NEW JERSEY (BB 62) firing its nine 16-inch/50 caliber guns simultaneously port and starboard. The blast is powerful enough to curve water below its radius in bowl shape down to a meter. These were the most powerful guns at sea, and probably better than those of Yamato in many aspects.

The rest of their career reflected a case unique in the annals in the USN. Instead of being scrapped (a common fate still in the 1970s), they had a long list of decommission/recommission for long periods, not linked to overhauls: Schemetically “reborn and awaken” in several key campaigns of the cold war: Korea, Vietnam, countering the Soviet Navy (especially some ships in particular, see below), and ending with the Gulf War, first post Soviet collapse war. When they were decommissioned a last time in 1990-92, they became museum ships, a new, educational role, showing that battleship could span and interwar conception, WW2 combat, cold war campaigns, and see the end of it, being preserved in the modern world and as time capsule for the time “big guns” reigned supreme.

They were modernized several times, which will be used to structure and summarize the present post’s analysis, which will thus exclude the whole design process, construction and initial design. Refer to the old post for this.

Summary

Early Carrier Conversion proposal (1942)

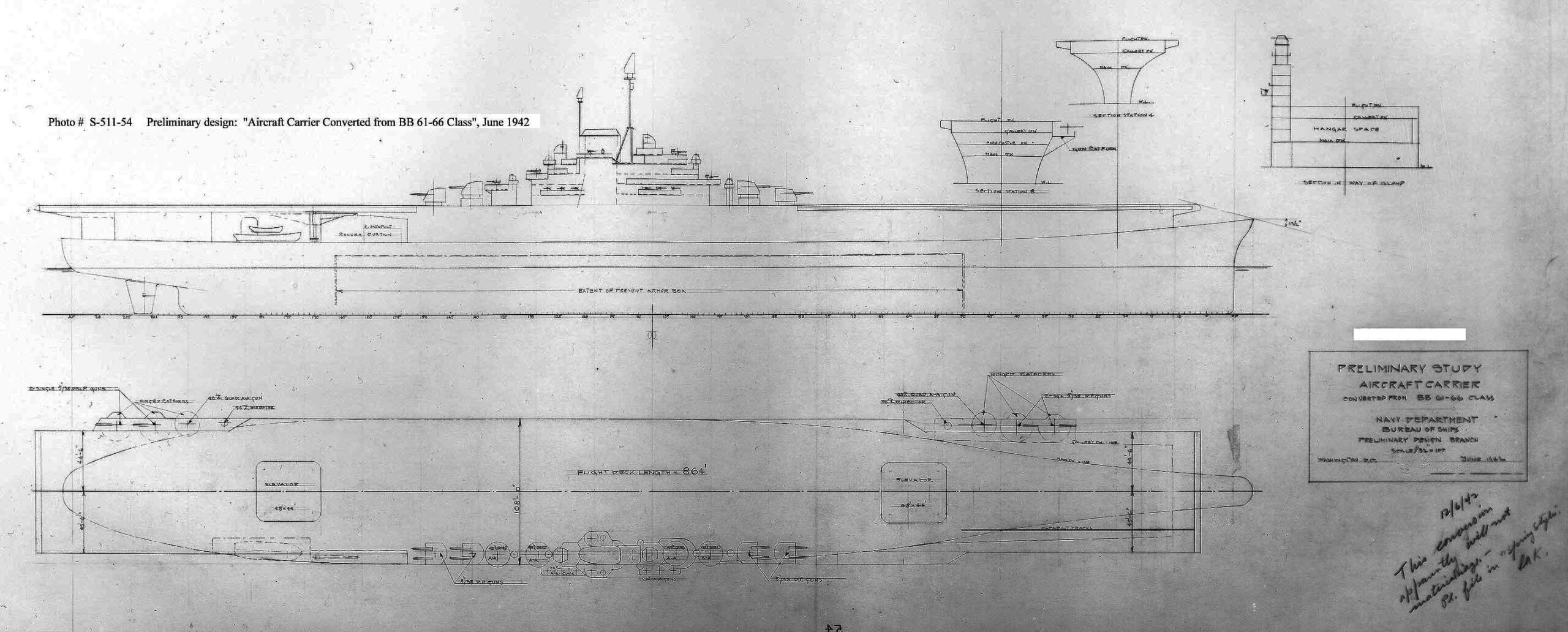

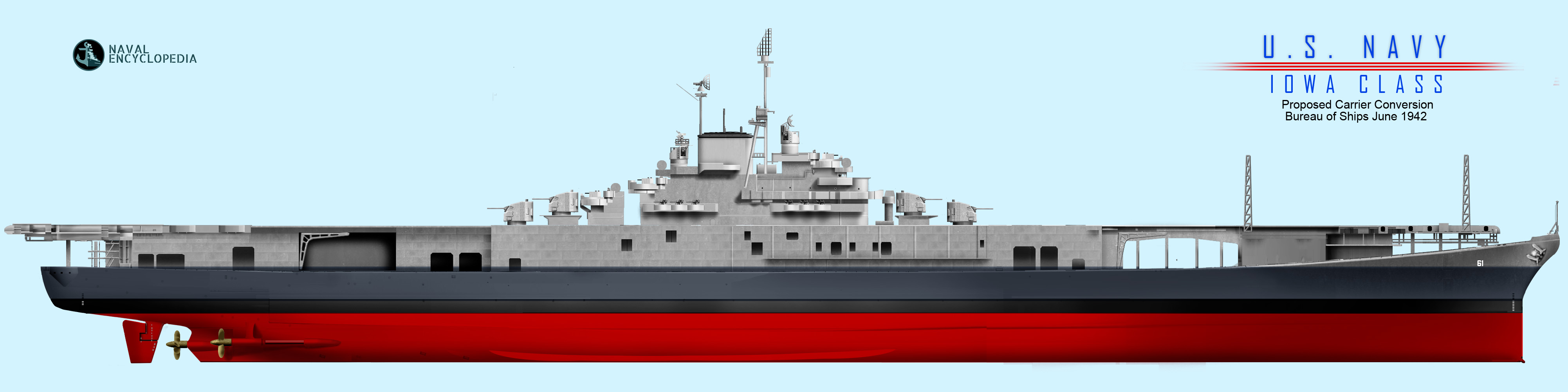

Conversion project #511-54 preliminary design, dated June 1942.

The Iowa class were the first US battleships for which a greater top speed was required for post-war operations, since they still fit the new fast aircraft carrier task forces. But the admiralty was keen of proposing conversions to reflect changes in technology and doctrine. One such plan was to ask for the installation of nuclear missiles for a greater strike value, or add aircraft capability with hybridation. For the never completed USS Illinois and Kentucky it was even intended to have them converted into armoured aircraft carriers.

Initially, the Iowa class only comprised BB-61 to BB-64 but changing priorities in wartime had the BB-65 (Montana) and BB-66 (Ohio) reordered as further Iowa class ships, USS Illinois and Kentucky while Montana and Ohio were reassigned to BB-67 and BB-68. As construction started, proposal was made at this early stage to convert them as aircraft carriers rather than fast battleships. And these prospects included plans to have them rebuilt with hangar over their weather deck, and a flight deck above. It was also proposed to have them fitted with the same armament as the Essex-class aircraft carriers under construction at the time: Four twin 5-in/38 turrets.

Ultimately, nothing came of this in 1942. They were cleared for construction as fast battleships to the Iowa-class while still differing in some ways. Eventually, the president choose instead to convert ten Cleveland-class light cruisers instead as stopgap aircraft-carrier conversion, the Independence-class light aircraft carriers. No doubt some in the Navy were divided upon the issue. One one hand they saw the light carrier conversion as a wast of time given their limited capacity in aircraft, but some supported it base on their stopgap quality, while the Essex class were completed.

As for the battleship conversion to aircraft carrier, there was no guarantee the conversion would end earlier than the Essexes, and certainly not before the Independence given the complexity of such vessels.

All could see however the advantages and drawbacks of the conversion:

In 1942, there has been plenty of return about the way the British armoured cruisers fared in the Mediterranean, in particular in Malta, resisting Stuka attacks. Reports impressed the US naval staff, but on the other hand there were many to see the drastic reduction in the air group due to the bulkheading of the hangar as an advantage, but they reasoned that the much larger hull would grant extra space and thus at least a 60 strong air park, completed to 100 if more could be parked on deck. The Iowa hull however was not optilized for a hangar and would have a reduced capacity compared to an Essex class, despite the added lenght. All the design could bring to the table is its speed and extremely strong hull, protecting well the gasoline and aicraft ammunition in or below the citadel. But to really match the advantages of this protection it was envisioned a level or armour, with the new STS plating being developed, and perhaps something of the level of the Essex class or stringer. But nothing was shown in the June 1942 preliminary design, and since the conversion was abandoned, it was never put on paper. The USN would have to wait for the Midway class to have their first proper armoured carriers.

USS Kentucky Missile Conversion proposal (1947)

After the surrender of Japan, construction on Illinois and Kentucky was stopped, USS Illinois was scrapped, but USS Kentucky however was too advanced for scrapping. So plans were proposed to complete her as a guided missile battleship (BBG) in 1947, by removing her aft turret, installing a new missile twin-armed system instead. The barbette would offer a formidable protection. A similar conversion was performed indeed on USS Mississippi (BB-41/AG-128) as a testbed for the RIM-2 Terrier missile, installed over her aft superfiring barbette.

Rear Admiral W.K. Mendenhall was the most eager proponent of this conversion, as Chairman of the Ship Characteristics Board (SCB). He proposed to budget the conversion estimated at $15–30 million for a completion asguided-missile battleship (BBG), but not only with the Terrier for fleet defence, but also as strike battleship with eight SSM-N-8 Regulus II guided missiles placed along the sides. The missiles, tested already on submarines, had a 1,000 nautical miles (1,900 km; 1,200 mi). Terrier or RIM-8 Talos were to be fitted aft (instead of the third turret) and the whole defence would be rounded by 3-in/50 new AA gun mounts. Also nuclear shells would be provided for the remaining 16-inch guns forward. This never materialized. USS Kentucky was sold for scrap in 1958, with spares used to repair her sister Wisconsin after a collision on 6 May 1956. Because of this she would earn by portmanteau the nickname “WisKy”.

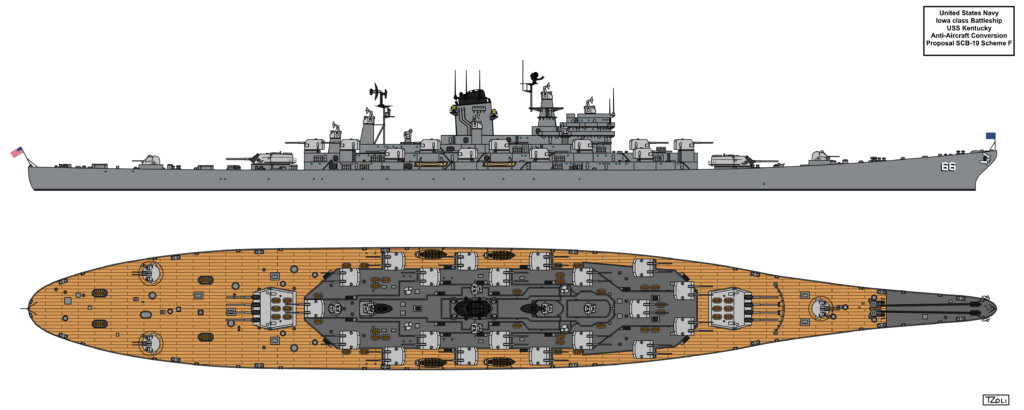

SCB 19 scheme F by Tzoli. In Friedman’s US BB’s book there was four designs of the last BBG series, with two single ended (forward artillery kept) and two double ended. The single ended had either two Regulus II launchers with 6 missiles or 16x Polaris VLS launch tubes, double ended had two single Regulus or sixteen Polaris.

USS Wisconsin launching a Tomahawk

Guided Missile Battleships proposals (1954-77)

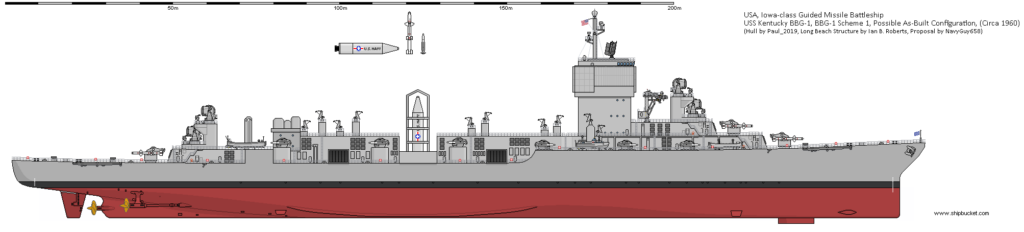

BBG-67 USS Kentucky

As early as 1946, a missile conversion project was proposed for USS Kentucky under project SCB 19, to be applied also in the incomplete large cruiser USS Hawaii. Dicussions went on and many variants were proposed. For SBC-19, as many as ten schemes, exploring also AA conversion, with notably new quad turrets with new projected 8-in dual purpose guns. But in 1949, AA ships were already considered obsolescent, as better missiles were tested.

In the early 1950s, advances in guided missile technology indeed led to a new proposal for Kentucky or similar size ships. The new proposal was for an hybrid with guns and missiles. The incomplete Kentucky was to be conversion into a fully fledged “guided missile battleship” (BBG), still conservative, with the installation of twin arm launchers for the RIM-2 Terrier SAM (surface-to-air missile) on the aft deckhouse (keeping the artillery intact), and the associated guidance radars and antennas AN/APG-55 pulse doppler interception radars installed forward of the launcher, and AN/SPS-2B air search radar on stubby mast.

At that stage, Kentucky was 73% complete, up to the second deck), and installation of the missile system and electronics meant just building on top, not digging anywhere or rework the accommodations. There were additional proposals to have two launchers for eight SSM-N-9 Regulus II missiles, or SSM-N-2 Triton nuclear cruise missiles as well, to be installed alongside the superstructure, a potent first stike combination. The guided missile battleship project was authorized in 1954, Kentucky earning the first and last “BBG-1” denomination in the Navy. The conversion was scheduled for full completion in 1956. Changes in the givernments and never ending rivalry between the Navy and Air Force on deterrence eventually caused the the conversion to be cancelled. All the paperwork done was not going to waste though, as the ideas led to the convcersion of the Boston-class guided missile cruisers, partial conversions of Baltimore-class heavy cruisers, which proved partially successful, led to the Galveston conversions and ultimately the Albany class. Rapid pace of in cruise missile technology indeed made the Regulus obsolete, but the heavy guns were still a premium as shown in Korea.

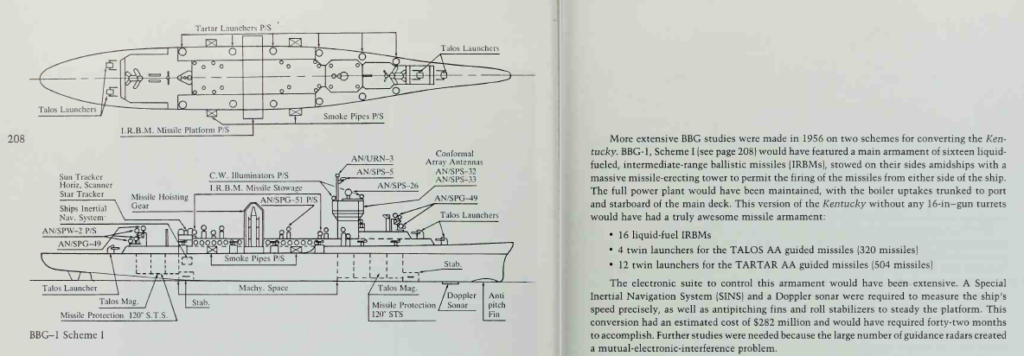

In 1956 there was an ultimate conversion project, this time without artilery at all, which barbettes would be reused for missile launchers. Kentucky would have had two Polaris nuclear ballistic missile launchers, sixteen weapons in early VLS (silos). A variant was for four RIM-8 Talos SAM (80 missiles per launcher) and twelve RIM-24 Tartar SAM launchers (504 missiles) for fleet defence. The July 1956 estimate projected completion by July 1961, but at such cost that many in the Navy suspected the Congress would never approve, and this led to another cancellation. Nevertheless, they would have been impressive saturation fire ships, more powerful than any guided missile destroyer/cruiser in service.

Kentucky being never completed, she stays to provide parts for the mothball fleet at Philadelphia Naval Shipyard, from about 1950 to 1958. Hurricane Hazel damaged her by 15 October 1954, she broke free from her moorings, ran aground in the Delaware River. In 1956 her bow was removed to repair of Wisconsin damaged in a collision with USS Eaton on 6 May 1956. Congressman William Huston Natcher attempted to block Kentucky’s sale in August 1957. But she was nevertheless stricken on 9 June 1958, the hulk eventually ended sold for scrap to Boston Metals Company in Baltimore on 31 October 1958 for $1,176,666. She was towed there by February 1959. Still, her hull was scrapped, but she was gutted to salvage everything for her sisters: The four 600 psi (4.1 MPa) boilers as well as turbine sets were stored for a time and eventually reused on the two Sacramento-class fast combat support ships laid down in 1961 and 1964.

The Navy switched to 1,200 psi (8.3 MPa) boilers and so the teams on Sacramento and Camden provided experience to operate USS New Jersey’s powerplant in her Vietnam tour, and later to the remaining sisters when recalled for modernization in the 1980s.

Two 150-pound (68 kg) mahogany doors donated by the state of Kentucky when in construction were removed and ended in an officer’s club in New York City, then returned to the Kentucky Historical Society in early January 1994.

BBG-64 Iowa class conversion

BBG-1 scheme 1 reconstituton by Tzoli

In 1954, the USN Long Range Objectives Group suggested to convert the Iowa-class into BBGs and in 1958, the Bureau of Ships offered a first proposal. They suggested the replacement of all 5-inches turrets as well as the original 16-inch gun batteries and then two Talos twin missile systems being installed as well as a two RIM-24 Tartar twin missile systems, and more advanced a RUR-5 ASROC antisubmarine missile launcher. Regulus II installation with four missiles would still be present. But the ships would also gain new flagship facilities as fleet escort coordinators, as well as a new powerful sonar in the bow, helicopters with dedicated hangar and larger helipad aft, and a brand new fire-control system for the Talos and Tartar.

The internals would be revised (at nuclear age) to provided them 8,600 long tons (8,700 t) of additional fuel oil, converted as ASW ballast both for her to follow new nuclear ships in construction or to refuel conventional destroyers and cruisers.

It’s the cost of such overhaul, estimated at $178–193 million that had it rejected as too expensive. Instead, the SCB suggested a more austere variant with just one Talos, one Tartar, one ASROC, two Regulus and some superstructure changes, down to an estimated $85 million. it was later revised for the Polaris Fleet Ballistic Missile in VLS launchers, and two more SCB schemes were studied and discussed. Eventually none of these were ever authorized.

General interest for converting the Iowas faned out in 1960, as now the ships were considered too old and still conversion costs too high cmpared to building brand new missile cruisers (like the Leahy class). This did not stopped more conversion proposals to be made further down the line, as the ships still were kept in reserve and not scrapped. On such proposal was in the 1962 with an advanced AN/SPY-1 Aegis Combat System radar. Such proposal resurfaced in 1974 and 1977. Noen again were authorized. Chief consideration about these, were sensitive electronics and the gun blasts of any 16-inch guns were not going to cohabitate well.

At Marinette Marine, a tug tows USS Wisconsin after her final refit in 1988.

USS Wisconsin in sea trials in 1988.

![]()

Kaman SH2 Seasprite on deck of USS Iowa in the 1980s

16-inch projectiles staged on the fantail for offloading from USS IOWA

Cold War Modernizations (1946-68)

Early Modernizations 1946-50

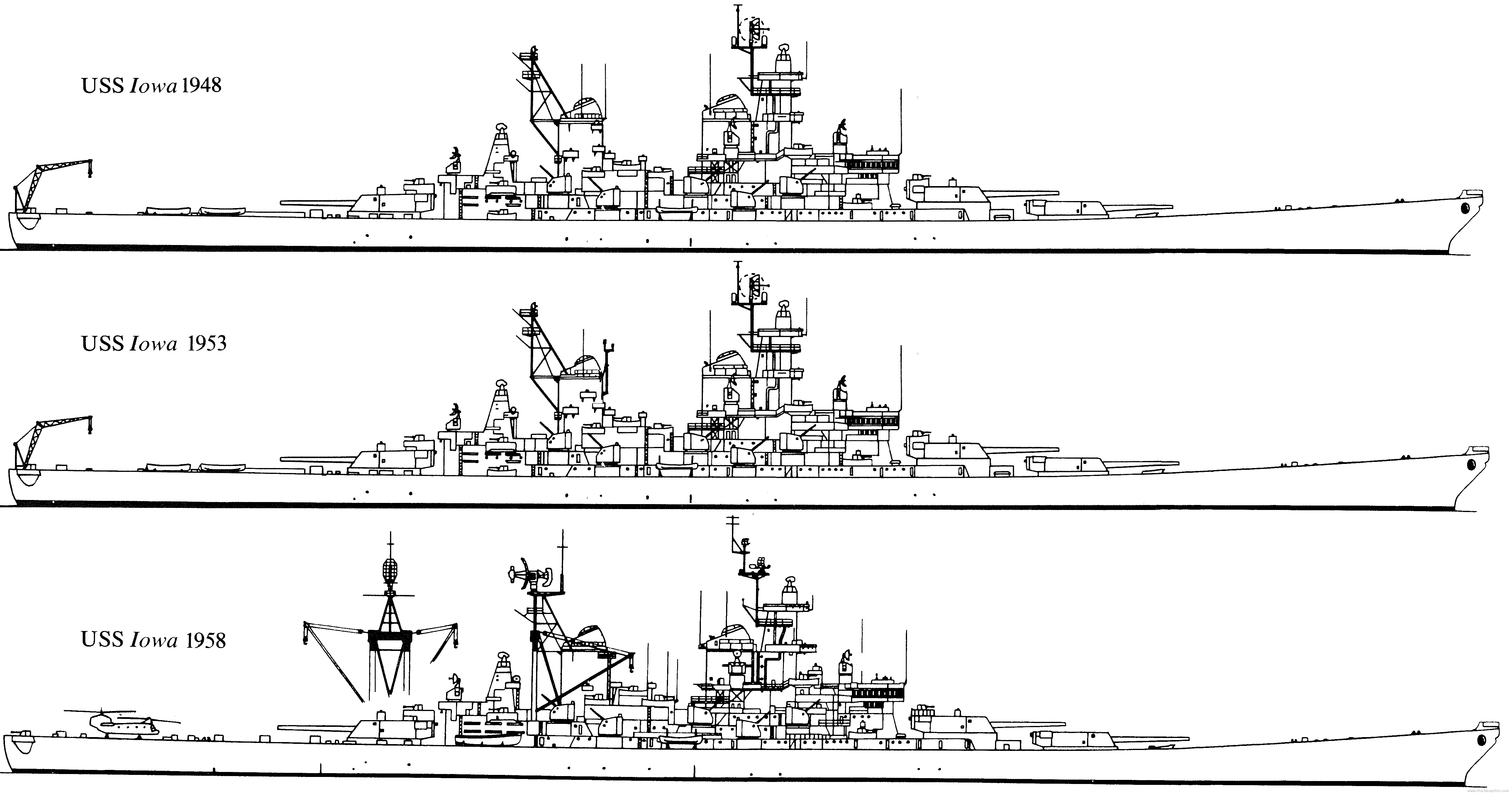

Already in 1945-46, modifications commenced. By March 1945 USS Iowa, the oldest of these veterans, saw her SG, SK, Mk 3, Mk 8 FCS and Mk 4 FCS radars being removed, twin 20mm/70 Mk 4 installed as her new radars were now the SC-2, SK-2, SP, SU, as well as two Mk 13 and four Mk 12.22 fire control plusd Mk 27 radars and the TDY ECM suite. This modifications were ported to her sisters. With the threat of Kamikaze, apart twin Oerlikon the ships had 19-20 quad Bofors, but in 1946, single Oerlikons started to be removed. What was removed also was their observation capability, but in 1948, with the removal of their two catapults and seaplanes on all ships as well as th removal of four quad bofors, eight twin and up to 32 20mm/70 Oerlikon guns. This was peacetime crew reduction.

In 1948 still Missouri and New Jersey gained an SR-3 radar and later Iowa, Wisconsin saw the adoption of a helipad aft carrying up to three helicopters as well as removal of their remaining two Oerlikons guns and all saw the adoption of SG-6, SPS-6 radars.

Modernizations of Korea

In 1951, with the war in Korea, Iowa saw the return of four quad 40mm/60 Mk 2 Bofors, same for her sisters New Jersey and Wisconsin but also of sixteen twin 20mm/70 Mk 24 or 32 twin for USS Missouri, also Mk 24. In 1953 New Jersey’s electronics were upgraded with the replacement of her SR-3 radar by the SPS-6. Wisconsin saw the removal of her SR radar and the SPS-8, SPS-12 installed, and all until 1954 saw the removal of their Mk 12.22 radars and replacement by the SPS-10, and four Mk 25 radars and in 1955, all had the SPS-8 radar.

Modernizations of Vietnam

Right after the Korean war, in 1956, USS Wisconsin started to lost some of her AA, with the removal of two quad 40mm/60 Bofors, and in 1954-1955, Iowa lost her Mk 25 radars, but gained new fire control radars: Six Mk 35, and two Mk 39 radars, leading the pack as always. Her sister New Jersey went the same way in 1955. Both also lost four Bofors quad mounts.

1956 USS Iowa was the first fitted with the new SPS-12 radar as New Jersey (with the removal of her SPS-6 radar).

Since they were put in reserve, no change was done until the Vietnam war was serious enough to motivate their return.

But USS New Jersey ws the only one affected: In 1967-1968, she saw the removal of eighteen quad 40mm/60, and her 1945 TDY ECM suite. Instead she received the SPS-10 radar, and the brand new ULQ-6B ECM suite as well as four Chaffroc decoy LR in case the NVA would be provided with Soviet antiship missiles.

It is interesting to note that none ever received the 3-in/50 AA twin mounts provided virtually to all USN ships in place of the quad Bofors, as they were tailored for this.

Full Modernization (1982-88)

SBC 19 and following projects 1954-77

The project SBC 19 consisted in the unique in history conversion of battleships into missile-armed command platforms, with a naval bombardment capability. Essentially they also replaced the now ageing Des Moines (Newport News/Salem) class cruisers as well as the hybrid Boston and Providence/Galveston class cruisers.

This was towards the Navy, perhaps the strongest gesture from the Ronald Reagan administration, and much a surprise for the Soviet Union. The upgrades after so many decades of technological advancements, and the threat of far better missiles was a challenge, but the Iowa class had an advantage over an aicraft carrier or even a missile cruiser or destroyer: Plenty of space to install new defence system and a greater capacity, albeit without VLS. All their missile capabilities would be external, thus more vulnerable.

It would have been wiser (retrospectively) in the prospect of a hybridisation, to have their aft turret gutted and replaced by a massive VLS (which was not yet a thing in 1982), with the advantage of a level of protection offered by the former barbette’s surrounding and casemate.

There were endless debates about the level of modernization against modern threats and taking advantages of her armour, something not shared by any ship in the fleet. Was her 12-inches armour belt capable of defeating an antiship missile warhead. It was understood the Soviet Navy would try if possibe to setup missiles to hit her superstructure instead if practicable, depriving her of her sensors. But of course, using nuclear warheads was still in the book also. So gradually, saturation missile inetrception became the priority over the years.

For the great lines, the Iowa class after modernization became heavier, but nothing in the hull changed: They kept their original steam machinery, and fortunately there were still enough WW2 vets to pass on their knowledge to rookies over its use. Same for the main and secondary artillery, which still used the same systems unchanged.

After all the additions on superstructures, the Iowa class grew to 50,453 tonnes standard indeed and 59,065 tonnes fully loaded. Officially they were still not the largest battleships ever built, beaten by the Yamatos by a fair margin. Their draft was augmented by 30 cm (1 feet) at 37 feet.

Their machinery being unchanged, so was their top speed of 32.5 knots, oil capacity of 7,621 tonnes giving them a global reach of 15,000 nautical miles at 15 knots.

Reagan’s administration “600 ships fleet” 1982

USS Wisconsin (BB-64) Underway at sea, 1988-91 period. Official U.S. Navy Photograph, collections of the Naval History and Heritage Command.

The idea behind the “600-ship Navy” emerged during the Vietnam War when it expanded rapidly with more demands, notably in small rivering vessels, PBR and monitors as well as amphibious ships.

The Soviet Union supported North Vietnam and Soviet vessels were more present than ever in all seas including the Gulf of Mexico as well as stepping up infantry, armor and air assets in Eastern Europe. In 1980 Ronald Reagan, freshly elected as Republican president, stepped up his stance and hardline with the USSR when by 1984 under a campaign commercial “Bear” promoted higher vigilance and increase of defense expenditures, which led to the completing programs such as the B-1B bomber, Bradley fighting vehicle, Abrams tank while Secretary of the Navy John F. Lehman and Caspa Weinberger at the defense, wanted the Navy share this increase, albeit funds were not available.

At best the “600” program peaked at 594 ship in 1987, and sharply decreased after 1989. Its most obvious gesture was the Recommissioning the Iowa-class battleships but also keeping older ships in service longer, stepping up production of Nimitz-class aircraft carriers as well as a large new construction program which was not implemented, although the Los Angeles class submarines received new upgrades and extension of construction, the Ohio class got a boost, and the future Arleigh Burke class destroyers were planned as mixing the advantages of previous Spruance and Ticonderoga.

One aspect frequently popular, cited by many historians, is the knowledge of the Kirov class “battlecruisers” in the Soviet arsenal.

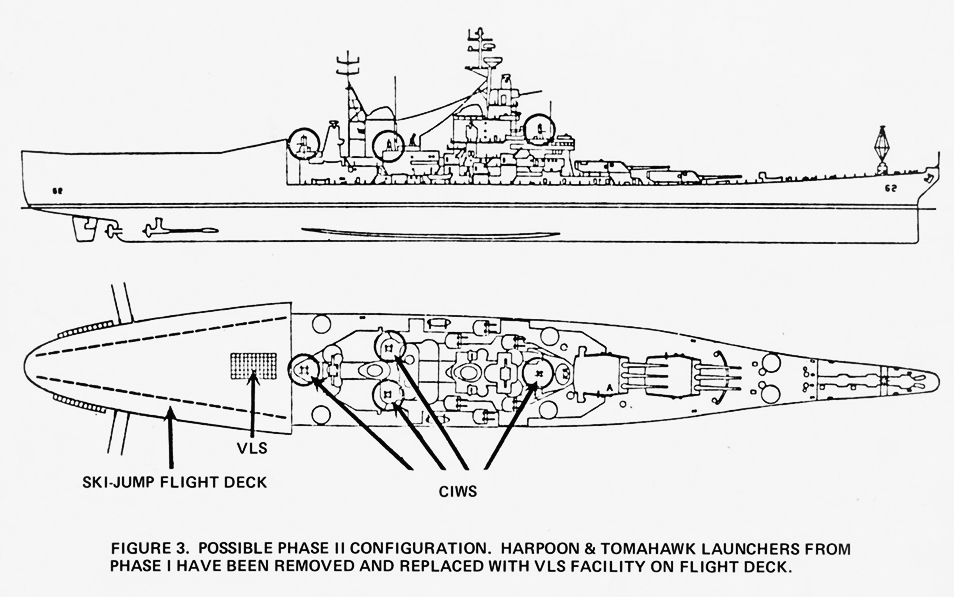

Phase I/II Battlecarriers

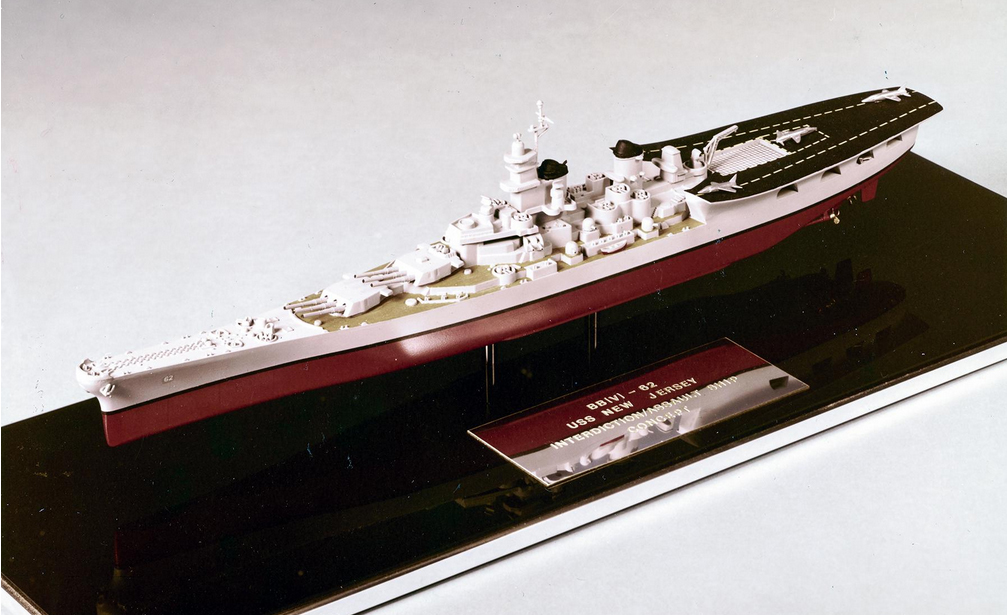

Martin Marietta project for BB(V)-62.

There was a 1970s Amphibious Assault/Commando Ship Conversion proposal with a raised aft hangar and flight deck with seven spots for heavy helicopters (such as the Sikorsky H3 Jolly, and Chinook). They would have kept their forward artillery, making sense for gunnery cover. It was not adopted.

In the same line as many projects of modernizations were studied in 1982, there were two “Battlecarrier” proposals which went far enough to generate a lot of paperwork, plans and models. The idea again was to keep their forward artillery, but convert again the rear section for a hangar and flight deck, split in two STOVL tracks either sides, single lift and operation of a range of helicopters and AV8B harrier IIs. Tomahawks and Harpoons as well as CIWS would have been provided as well.

This proposal from Martin Marietta for the BB(V) design proposal saw a single large VLS block aft of the island structure with 320 cells, and still standard 2×4 8-cell module size. Blast overpressure problems from the 16-inch guns prevented the use of Sea Sparrow which Mk29 launcher were too fragile. They had early types of CIWS before the Phalanx. This BBV proposal never get approval.

Armament

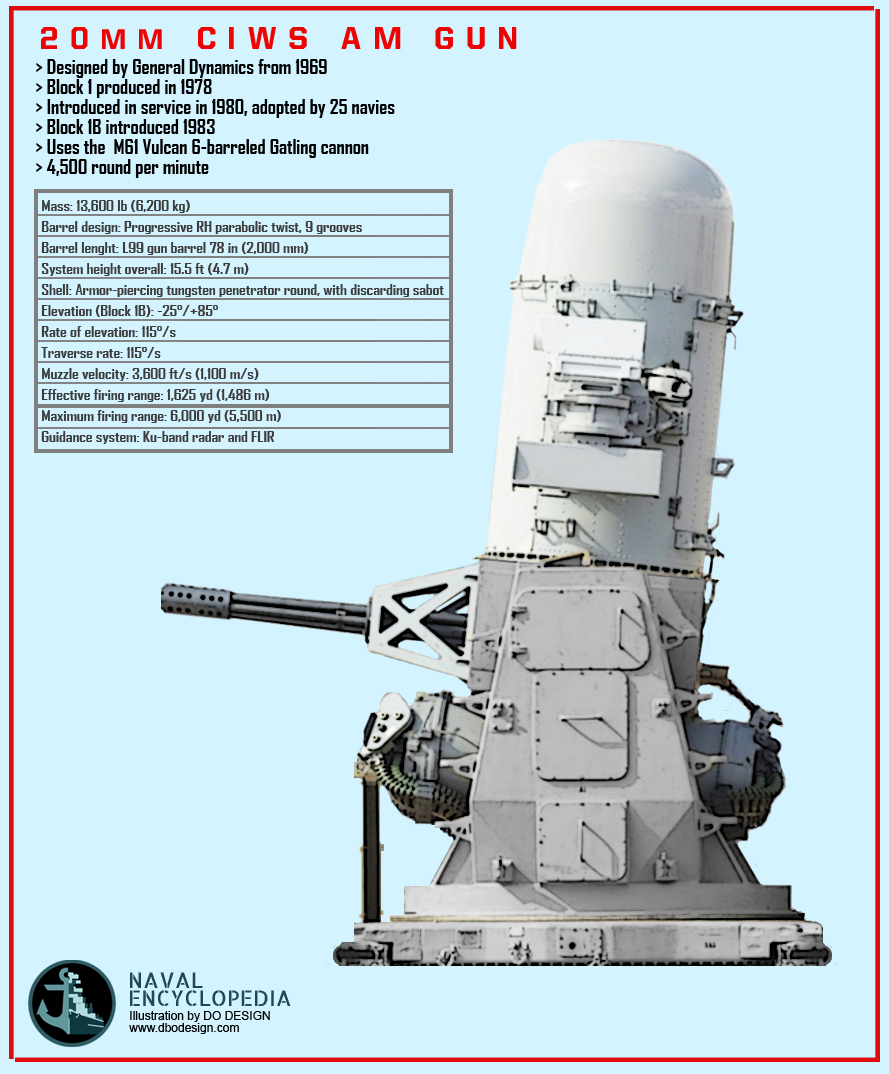

For guns, they kept on paper (all but NJ) their three triple 16-in/50 Mk 7 main guns, 4 or 6 twin 5-in/38 Mk 28 secondaries, and gained in 1982-86 four six-tubes gatling 20mm/76 Mk 15 Phalanx CIWS.

As for missiles, they gain eight quadruple armoured canisters Tomahawk CruM (32 BGM-109B), and four quad canisters Harpoon SSM (16 RGM-84A). There was an helicopter deck aft with 2-3 multirole Seahawk helicopters.

Main Guns: Three triple 16-in/50

The 16-in/50 Mark 12 were a longer barrel variant of those installed on previous battleships classes, and one of the very best ordnance of WW2, only comparable to the British BL 15-inches Mk I naval guns. They were virtually identical to the 45 caliber (North Carolina-South Dakota) but tailored to fire the new “super heavy” 16-in 2,700 pound (1,224.7 kg) AP Mark 8 with general performances estimated equal to the 46 cm (18.1″) of the Japanese Yamato class, and longer range. They were capable of 29 miles (47 km) max and 23.64 mi (38.04 km) accurately. In 1989 off Vieques range in perfect conditions (static, calm seas, clear blue sky), USS Iowa set an absolete record by hitting her target at 23.4 nmi (26.9 mi; 43.3 km).

They had plently of occasions of shine during their career, not against ships, but shore objectives, in the Pacific for the final phase, Korea, Vietnam, Lebanon and the Gulf war.

The installation of modern electronics in the cold war improved their accuracy but at the the same time, limited what upgrade could be done due to fragility of these systems versus the blast of these big guns. Each Mark 7 had its bore plated over in chromium to extent life. Still they were changed several times during their career.

The venerable main battery was kept all the way to the end of the cold war. On USS New Jersey, “C” (the aft one) turret was welded shut, all the internal ammo system deactivated and no ammunition carried. It became a “dummy” turret in effect. This was a measure of both safety and cost reduction. There was aguarantee however the welding could be undone and the turret reactivated in wartime. The other was USS Iowa. In 19 April 1989, “B” turret burst into flames, following an accidental explosion due to improper powder storage, an old story that affected so many battleships over time. The turret was later deactivated. USS Iowa due to this was the first deactivated.

USS Missouri after modernization

Secondary guns: Still 4×2 5-in/38

On all sisters, the secondary Mark 12 twin turret artillery was gutted, no longer relevant at the age of missiles. Only six (Iowa) or four turrets (New Jersey) were kept. Iowa had two abaft the funnel. The others only kept the four outer ones. These had been covered in great detail in the previous post. They were kept both as an AA “guarantee” since there was no AA aboard left in 1982, and were useable for shore bombardment. No significant upgrade was done over the years, the Mark 37 fire control systems through remote power control (RPC) and associated radars were kept as excellent for them despite their age. They could fire 15–22 rounds per minute with proximity fuses rounds at a range of 18,000 yards (16,000 m) and ceiling of 37,200 feet (11,300 m).

20mm/76 Mk 15 Phalanx CIWS

Four systems were installed during their 1980s modernization, as a last stand defence against missiles. Many criticized it as unsufficient, pleading for at least four more. It was not a problem of space aboard. They were installed high up in the superstructure.

Tomahawk Missiles

The presence of eight quadruple armoured canisters for Tomahawk Cruise Missiles (32 BGM-109B total) underlined their long range strike nature. The canisters were installed on the aft upper deck (four canisters, pointing forward on either side at oblique angle) and four on the midship upper deck, pointing on either side at a 90° angle.

The Tomahawk was indeed not a preimary defence or antiship asset, but a long range strike one.

It weighted 2,900 lb (1,300 kg), 3,500 lb (1,600 kg) with booster for 18 ft 3 in (5.56 m) long without booster, 20 ft 6 in (6.25 m) with and 20.4 in (0.52 m) in diameter, 8 ft 9 in (2.67 m) in wingspan when automatically extended after launch.

It could carry a nuclear W80 warhead (yield 5-150 kt) but the usual payload was the 1,000 pounds (450 kg) HE/submunition dispenser/BLU-97/B PBXN. Powered by a Williams International F107-WR-402 turbofan with TH-dimer fuel and solid-fuel rocket booster for launch, range for the Block II was 1,350 nmi (1,550 mi; 2,500 km) at an altitude of 98–164 ft (30–50 m), guided by GPS, INS, TERCOM, DSMAC, active radar homing for the UGM-109B. They were put to good use by Wisconsin and Missouri in the gulf war, destroying strategic Iraqi objectives well inland. A good complement to the 40 km range gunnery.

The Tomahwak however could be vectored against other ships, it was the case for the RGM/UGM-109B TASM variant with active radar homing, withdrawn from service in 1994. An argument as a “kirov killer”. They were longer range than the Harpoon indeed but easier to spot and jam.

Harpoon Missiles

As a complement in medium range, the four quadruple launchers RGM-84A were located on a former 40 mm Bofors platform abaft the aft funnel. The launchers were lightly armoured and hosted four individual missile tubes each. They were oriented to port and starboard at 90° and angled at 45°. These antiship missiles developed from 1977 by McDonnell Douglas and Boeing weighted 1,523 lb (691 kg) including booster for 15 ft (4.6 m) long, 13.5 in (34 cm) in diameter, 3 ft (0.91 m) in wingspan and carrying a 488 pounds (221 kg) utility warhead, conventional (nuclear one in option) using impact fuze. They were powered by a Teledyne CAE J402 turbojet/solid propellant booster (600 lbf/2,700 N of thrust) for 75 nmi (139 km) range, using Sea-skimming and anti-jamming devices.

They flew at 537 mph (864 km/h; 240 m/s or Mach 0.71), monitored by radar altimeter and with active radar terminal homing to the target.

Helicopters Aboard

A Sikorsky HU-1 helicopter lands on USS Missouri during target practice with midshipmens in 1948. Launching and recovring helicopters seems easier than recovering floatplanes. There was however no lift or hangar to house and service them although this was planned in the future, and obtained with the 1980s refit. The spot was also reninforced to allow operation of much heavier helicopter such as the CH-53 Sea Stallion. In the Vietnam era and beyond, the standard was a Kaman SH-2 Seasprite. more about this on the cold war page.

![]()

A Kaman SH-2 Seasprite on USS Iowa, 1980s

Post-1988: 2-3 SH SH-60 Seahawk

Sensors

SPS-49

SPS-49

Raytheon 24 ft (7.3 m) × 14 ft 3 in (7.3 m × 4.3 m) 2D radar developed in 1975, using L band 851–942 MHz for a range of 3 nmi (5.6 km) to 256 nmi (474 km) (AN/SPS-49A(V) and up to 150,000 ft in altitude (45,720 m). Precisionw was 1/16 nmi range at 0.5 deg azimuth, Power 360 kW peak and 13 kW average.

SPS-67

Short-range 2D surface-search/navigation radar providing highly accurate surface but limited low-flying (missile) detection and tracking. Worked in C band (5450 to 5825 MHz) at 15/30 rpm to a Range of 104 km (56.2 nmi), Azimuth 1.5°, Elevation 12°-31° in later versions, Power 280 kW.

SPS-64

AN/SPS-64 Mariners Pathfinder radar, surface search and navigation radar, a classic also used in almost all USN ships and civilian vessels. Frequency 9 375 ± 25 MHz in X-band or 3 030 ± 25 MHz in S band, PRF 900, 1800, 3600 Hz, pulsewidth 0.06, 0.5, 1 µs, peak power 10, 25 and 50 kW, 60 kW with range 64 nm (118 km), beamwidth 0.7°, 0.9°, 1.25°, 1.9°, 33 rpm.

SPS-10F

Only BB-62 Iowa retained this 1959 2D radar. It worked on C Band at a PRF of 650 Hz, Beamwidth of 1.9° × 16°, Pulsewidth of 1.3 µs, Power 280 kW.

Two Mk 13 FCR

Main battery fire control system. Installed on the forward and aft superstructure. Each director was topped by a fire control radar, providing long range data. The Mark 13 radar could be used to spot shot plumes location in both range and deflection. They appear on B-scope as fluctuating echoes lasted several seconds. This system was accurate and reliable at full range, independent of visibility conditions. It made spotting planes redundant in effect.

Four Mk 25 FCR

Secondary battery fire control radars. 50 kW, operates in X-band with automatic tracking coupled with the Gun Director Mark 37 for the 5″/38. Data is used to automatically train, elevated and set fuse range setup. The antenna is a paraboloid reflector 62 inch wide using linear vertical polarization. PRF 2 000 Hz, pulsewidth 0.2 µs range 24 nm (45 km) with a resolution of 36 m, beamwidth of 1.3°.

SLQ-32(v)3 ECM suite

The AN/SLQ-32(V)3 had antennas with electronic attack capability to actively jam targeting radars and anti-ship missile terminal guidance radars.

8x SRBOC Mk36 decoy RL

Complement to the CIWS, these decoy rocket launchers launches radar or infrared decoys to interfere with the incoming missiles final guidance systems. The basic Mark 137 launcher has six fixed 130 mm mortar tubes arranged in two parallel rows. With eight systems, each side could be covered by 24 chaff explosion, enough for saturation attacks.

SLQ-25 Nixie torpedo decoy

The 1987 AN/SLQ-25 Nixie is a towed torpedo decoy system composed of the decoy device TB-14A and shipboard signal generator. It is used to defeat wake-homing, acousting-homing, wire-guided torpedoes. Signals are emitted to draw away the incoming torpedo.

⚙ 1988 specifications |

|

| Displacement | 50,453t standard, 59,065t FL |

| Dimensions | Same as original (262,1 wl/270.4 oa x 33 m wide) but 11.3 m (37 ft) full load |

| Propulsion | Same, 4 sets GE geared steam turbines, 8 Babcock & Wilcox boilers 212,000 shp. |

| Speed | Same, 32.5 knots |

| Range | Same, 7,621 tons oil, 15,000 nm/15 kts |

| Armament | 3×3 16-in/50 Mk7, 6×2 5-in/38 Mk28, 8×4 Tomahawk, 4×4 Harpoon SSM, 4×6 20mm/76 Mk 15 Phalanx |

| Sensors | SPS-49, SPS-67, SPS-64, Mk 13, Mk 25 radars, SLQ-32(v)3 ECM suite, SRBOC Mk36 decoy RL, SLQ-25 Nixie TD |

| Protection | Unchanged, see the WW2 article. |

| Crew | 1518 instead of 1921 |

Conclusion: The Iowas, possible return or replacement awaited ?

Eventually Reagan’s ‘600 ship’ program was never achieved, but drastic budget cuts continuously toned it down until a “400 ship” became already optimistic. Weinberger clashed so much with Congress he resigned by late 1987, succeeded by Frank Carlucci which maintaine the same line, until in turn resigning in 1988. Many indeed crititzed expansion of the Navy as reducing resources from land and air assets deployed in Europe.

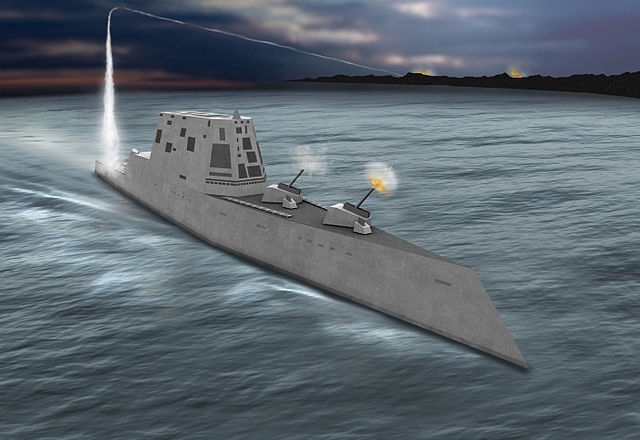

The Soviet navy was indeed a global threat in 1988, but many thought the USN still remained vastly superior and budget reductions were justified, reallocating funds to modernized the Navy and focusing on quality rather than quantity. On the long run, this trigerred a collection of new classes, the Zumwalt destroyers, and infamous Littoral Combat ships. But also to fund these, the the Navy, retired not only its older carriers, decommissioning of all four Iowa-class battleships cancelled the remaining Seawolf-class submarines.

Next the OH Perry class frigates and Ticonderoga class were all retired, after the Spruance class, leaving the fleet with “only” the Nimitz class and Arleigh Burke as escorts. With the rapid rise of the Chinese PLAN it’s clear that the new direction taken is not prepating well the Navy for new challenges in Asia and over Taiwan. There is no question today of bringing back the Iowas, as they are now since the 2000s definitely out of the mothballs and musuem ships.

In a potential conflict in 2027, the most cited date for an all-out assault on Taiwan which would mathematically involve the bulk of the USN in the Pacific (since Europe could deal with Russia), with its allies, losses would be massive. Would resurrecting the Iowa clas at great cost would be justified ? There is currenlty only one Kirov class left, in “eternal refit” for years. It is very unlikely it would be ever sold to, or copied by the PLAN. The latter could still resurrect the Minsk, but with delays and at great cost. There is no ship currently in the PLAN arsenal that could justify the resurrection of a ‘battleship battle group’ as in the late 1980s centered around modernized Iowas. The congress for very long wanted these to be reactivated as shore bombardment vessels, but their overall maintenance and operating cost is not a very sensible decision based on this sole purpose. True, previous projects like a 1960s test of a brand new 8-in gun turret ended nowhere. The concept was resurrected with the Zumwalt’s electric hyper velocity cannons, but the program is still under development today.

Late 1970s strike cruiser project, 17,000 tonnes design

Apart shore bombardment, what the Iowas incarnated was the concept of a “batteship”, a ship with superior capabilities notably fr shore to shore engagements, leading to endless debates already for their replacement in the 1980s on a potential missile armed large ships usable for saturation fire, either for inland strikes with Tomahawks and ship to ship strikes in fleet operations. A US equivalent of the Kirovs. The Zumwalt could have been a starting point for this return of a large cruiser type in the US inventory but so far not prospects for this are going on seriously.

Instead, the new fleet envisioned is rather calling for more interoperability berween satellites, air assets and air/naval/underwater drones, as well as between Destroyers. If acting in perfect coordination, four or five Arleigh burke can indeed provide this decisive saturation strike.

Zumwalt class in early artist depiction with its long range heavy guns and VLS, the designated planned replacement of the Iowas reasuring the Congress.

The debate is still open.

Cold War career of the Iowas: 1946-1990s

USS Iowa (BB 61)

USS Iowa (BB 61)

USS Iowa ended her Pacific campaign and after leabving her occupation duties behind she proceeded home via the north (Aleutians) to Seattle, Washington, on 15 October 1945 and then sailed southwards to Long Beach, for rest and training operations and back to Japan in 1946. There, she became flagship for the 5th Fleet (TF 58) until 25 March 1946 and training ship again in home waters, which included a cruise with the Naval Reserve and midshipmen.

October saw her in overhaul and modernization (SK-2 Radar, some 20 – 40 mm mounts removed) and by July, after Bikini experiment she was chosen to fire on USS Nevada was selected, a test starting with separate shellings from a destroyer, heavy cruiser, and Iowa. Nevada survived the shelling and was finished off with one aerial torpedo. She sank 65 mi (105 km) from Pearl Harbor, 31 July 1948. By September Iowa was deactivated at San Francisco, formally decommissioned on 24 March 1949. Discussions started about converting her and her sisters as a missile battleship (BBG).

However by 1950, war in Korea had President Harry S. Truman ordering US forces stationed in Japan, under UN mandate, to transfer to South Korea and mobilized a strong naval force, upon which many ships were reactivated, including USS Iowa on 14 July 1951, formally recommissioned on 25 August. Her captain was William R. Smedberg III and she sailed for Korea by March 1952, after a long work of reshaping her for service, and training rookies. On 1 April, she relieved USS Wisconsin and took her place as flagship, Vice Admiral Robert P. Briscoe, 7th Fleet. She was detached for shore bombardments at Wonsan–Sŏngjin on 8 April 1952 and the following day on troop concentrations and supply areas, gun positions off Suwon Dan and Kojo.

She supported South Korea’s I Corps on 13 April, notably destroying the local NK headquarters. In Wonsan Harbor she shelled installations around and railroad. Next she joined the UN flotilla off Kosong. On 20 April, she shelled railroad lines at Tanchon, collapsed four railroad tunnels and bombarded Chindong and Kosong. By 25 May with USS Missouri she arrived off Chongjin, 48 nmi (55 mi; 89 km) from the Russian border and reduced to rubbled the industrial and rail transportation centers. Next she assisted the US X Corps, bombarded Sŏngjin en route, collapsed tunnels and bridges, and on 28 May bombarded islands in Wonsan Harbor.

In June, she shelled Mayang-do, Tanchon, Chongjin, Chodo–Sokcho, Hŭngnam and Wonsan. On 9 June her own helicopter rescued a downed pilot from USS Princeton as part of TF 77 in the bombing campaign and close air support missions around the clock. By July, Captain Joshua W. Cooper took command until the end of her service in Korea.

On 20 August she embarked nine wounded men from USS Thompson, damaged by Chinese artillery battery fire at Sŏngjin. Iowa also covered Thompson to safety. On 23 September, General Mark W. Clark, CiC of Korean forces in Korea came aboard. On 25 September, Iowa destroyed both a 30-car train and railroad. In November she took part in Operation Decoy, a feint to draw troops in Kojo close enough for her to bombard them to oblivion. All this time she also covered USS Mount McKinley, amphibious force command ship.

In October 1952 she was still flagship, and performed some 43 bombardment missions on Wonsan, Songjin, Kojo, Chaho, Toejo, Simpo, Hungnam, northern Inchon, spending her whole stock several times with 16,689 main rounds, being awarded the UN Service Medal and Korean Service Medal, one bronze star.

This concluded her Koean war. Back home she resumed her training routine, with midshipmen cruise in Northern Europe by July 1953, and NATO Operation Mariner as flagship, VADM Edmund T. Wooldridge, 2nd Fleet. September 1954 saw her as flagship, RADM R. E. Libby (Battleship Cruiser Force), Atlantic Fleet. January–April 1955 saw her in extended cruise to the Mediterranean and flagship, Commander 6th Fleet.

Next she had a midshipman training cruise on 1 June and received a 4 months overhaul at Norfolk followed by training cruises, fleet exercises until 4 January 1957 and another deployment in the Mediterranean. She made also a South American training cruise and was at the 13 June Hampton Roads review.

On 3 September she was in NATO’s Strikeback off Scotland. By 22 October she entered the drydock of Philadelphia Naval Shipyard, prepared, then decommissioned on 24 February 1958, Atlantic Reserve Fleet. It was unclear at that time if after ten years she would be sold for scrap, but that was a likely option. Alas, if her sister New Jersey was reactivated to take part in Vietnam, she lingered in mothballed way pas the 1970s.

Under the Reagan administration, Secretary of the Navy John F. Lehman was given the task of creating a “600-ship Navy”, but also improved on quality. USS Iowa was thus reactivated in 1982, moved to Avondale Shipyard (New Orleans) for a complete refitting and torough modernization for her recommissioning after being towed to Ingalls Shipbuilding, Pascagoula for more upgrades. This program was long to be realized.

By June 1986, she received the RQ-2 Pioneer Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV), replacing helicopters and usabled for gunnery spotting. Official recommission was earlier, by 28 April 1984 and ahead of schedule and budget ($500 million). First skipper was Captain Gerald E. Gneckow. Her machinery of main guns however were not overviewed by the Navy Board of Inspection and Survey to gain time as Reagan insisted to have all four at sea as soon as possible as a gesture to the Soviet Navy.

April-August 1984, saw Iowa in refresher training, naval gunfire qualifications at Guantanamo Bay and Puerto Rico, homeported to Norfolk, and used for operations in local waters and around Central America. She crossed the Panama Canal to the west coast and took part in humanitarian operations in El Salvador, Costa Rica and Honduras and back home on April 1985 for maintenance.

In August 1985 she was present in the multination, 160 ships armada of NATO Exercise Ocean Safari, to control sea lanes. Bad weather marred her deployment and she moved noth and passed the Arctic Circle, and by October was in the Baltic, for live firing on 17 October. She stopped at Le Havre, Kiel, Copenhagen (where she hosted an official Royal visit and reception), Aarhus (Denmark), Oslo (receiving the King of Norway) and back home.

17 March 1986 saw her inspection made, which failed under RADM John D. Bulkeley as she was unable to reach 33 kn (38 mph; 61 km/h) in sea trials, and had scores of other problems, so much so the CNO recommended she was decommissioned. It was however rejected and reports were made more lenient.

She made another tout of Central America, drills and exercises and by 4 July, President Ronald Reagan, First Lady Nancy Reagan boarded her for an International Naval Review in the Hudson River. On 25 April she had a new captain, Larry Ray Seaquist, and Iowa was soon in Naval Gunfire Support requalification off Vieques Range.

On 17 August, she was in the North Atlantic and by September at Exercise Northern Wedding with live fore at Cape Wrath range in Scotland for a support exercise. She stopped at Portsmouth, then Kiel, and home by October.

In December she tested the new RQ-2 Pioneer UAV. In January–September 1987 she was off Central America, then Mediterranean in September until 22 October, and the North Sea, by 25 November she returned and started Operation Earnest Will, crossing the Suez Canal to the Persian Gulf to watch over traffic during the Iran–Iraq War and the “Tanker War” phase. She escorted Kuwaiti gas and oil tankers reflagged as US merchant ships in the Strait of Hormuz.

On 20 February 1988 she sailed back to Norfolk for maintenance. In April she was at Fleet Week before an overhaul at Norfolk and had a new captain, Fred Moosally. After her shakedown cruise around Chesapeake Bay and trials until September, refresher training off Puerto Rico and her Operation Propulsion Program Evaluation. 20 January 1989, while off Vieques she set a record main battery shell on target at 23.4 nmi (26.9 mi; 43.3 km). In February she visited New Orleans. On 10 April she hosted the 2nd Fleet CiC. followed by fleet exercise.

During a gunnery exercise, at 09:55 on 19 April 1989 however, she suffered an explosion of N°2 16-inch (406 mm) gun turret. It killed 47 crewmen, nearly all onboard the turret. Fortunately, a gunner’s mate in the powder magazine below undrestood what was happening and without orders flooded No. 2 powder magazine, saving the ship. The Naval Investigative Service believe it was a suicide attempt and if the Navy was satisfied with result, many in the crew were unconvinced. By October 1991, Congress forced the Navy to reopen the case and a new investigation by independent investigators pointed our an accidental powder explosion. At that stage, Iowa was replaced by New Jersey, at the time, only commissioned battleship in the world and Iowa’s modernization was rushed. Investigators also pointed out that training aspects for the main battery had been left over and that Captain Moosally seemed to focus more on missiles and modern system aboard than the battery.

Powder was tested at the Naval Surface Warfare Center Dahlgren Division and it was observed spontaneous combustion within, estabilishing this 1930s powder had been improperly stored in a barge at Yorktown NWS and degraded. This forced the Navy under CNO Admiral Frank Kelso to publicly apologize to the Hartwig family while Fred Moosally was criticized for his handling while powder-handling procedures were changed for the sister battleships.

In 1991 the collapse of USSR called for massive budget cuts and the costly to operate battleships became first under fire. USS Iowa was decommissioned on 26 October 1990 (19 years of service). She was first because of her damaged turret as nothing happened for her in 1990. From Philadelphia Naval Shipyard, she moved to NS Newport from 24 September 1998 to 8 March 2001, and was towed to California, Suisun Bay, San Francisco on 21 April 2001 put in the Reserve Fleet, stricken in March 2006, and left there until November 2011.

She was indeed to be reactivated for USMC amphibious operations but her damaged turret had New Jersey favored, with Wisconsin, replaced in the Naval Vessel Register and reserve fleet.

On 17 March 2006, it was decided that Iowa could be donated for use as museum ship while the Congress remained “deeply concerned” for the loss of gunfire support and wanted the ships to be maintained in a state of readiness. By March 2007 however, the Historic Ships Memorial at Pacific Square (HSMPS) at Vallejo (former Mare Island Naval Shipyard) and Stockton group proposed to buy the ship as museum. By October 2007 the Navy favored their application. By February 2010, the Pacific Battleship Center proposed Iowa to be berthed at San Pedro in Los Angeles with it was rejected and later passed by November 2010, with voting funds for adequate facilities, approved by the Pacific Battleship Center, and work was done at the Port of Richmond. From December 2011, USS Iowa opened to the public at Richmond and officially donated on 30 April 2012 to the Pacific Battleship Center in Los Angeles by the USN. Her hull was scrubbed and she was permanently docked in San Pedro Berth 87 south of the World Cruise Center, opening on 7 July 2012.

USS New Jersey (BB 62)

USS New Jersey (BB 62)

USS New Jersey mothballed at NyC in 1948

After occupation duties, New Jersey sailed for home in January 1946 as part of Operation Magic Carpet with 1000+ servicemen aboard. She operated on the west coast, had an overhaul at Puget Sound, and had a “birthday party” at Bayonne, New Jersey on 23 May 1947 with the Governor Alfred E. Driscoll present. 7 June to 26 August 1947 had her part of the first training squadron in Northern European waters with Academy members and NROTC midshipmen and Admiral Richard L. Connolly aboard, as CiC Eastern Atlantic/Mediterranean while at Rosyth on 23 June. She was at an official visit in Oslo, visited by King Haakon VII of Norway on 2 July, and Portsmouth. While back she trained in the Caribbean.

She became flagship for Rear Admiral Heber H. McLean (Battleship Division 1) at NyC between 12 September and 18 October but was inactivated at NyC Naval Shipyard, decommissioned at Bayonne on 30 June 1948, New York Group, Atlantic Reserve Fleet.

USS New Jersey in Korea

In 1950, the war in Korea saw all battleships reactivated. New Jersey was recommissioned on 21 November 1950, with Captain David M. Tyree in command, made a refresher in the Caribbean, sailed from Norfolk on 16 April 1951 after preparations and intensive traing with a partial rookie crew (framed by former vets) and arrived to Japan, then Korea on 17 May with 7th fleet Vice Admiral Harold M. Martin making her his flagship for six months. She started the first of many shore bombardment missions, at Wonsan on 20 May. During a counter-battery fire she was hit, with one killed and two severely wounded, and a near miss aft to port.

23-27 May, 30 May saw her firing on Yangyang and Kansong, notably destroying a bridge and three large ammunition dumps among other, well informed by Air spotters. On 24 May, she lost an helicopter, starved of fuel in SAR mission. Admiral Arthur W. Radford (7th fleet CiC) and Vice Admiral C. Turner Joy (CNF Far East) were aboard for another mission on Wonsan by 4 June, then Kansong and had to silence shore batteries afrter many near misses to port. 4-12 this was the Kansong area, and Wonsan on 18 July, 17 August at the Kansong area as on 29 August, then Changjon area. On 23 September she rescud the crew of Korean frigate Apnok (PF-62) damaged by gunfire, and reurned bombarding the Kansong area for the U.S. X Corps. She was visited on 1 October 1951 by WW2 fame General Omar Bradley, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Matthew B. Ridgeway, CiC Far East for a conference with Admiral Martin.

In October USS New Jersey baombarded Kansong, Hamhung, Hungnam, Tanchon, Songjin. In some occasion she used her five-inch (127 mm) gun mounts. In the Kojo on 16 October she was assisted by HMS Belfast and HMAS Sydney. This operation was a rousing success.

Sher pounded infrastructures at Wonsan, Hungnam, Tanchon, Iowon, Songjin, and Chongjin in the winter, then Kansong and Chang-San-Got until ending her first tour of duty in Korea, relieved by USS Wisconsin. After rest at Yokosuka she transited to Hawaii, Long Beach, Panama and Norfolk on 20 December followed by a 6-month overhaul. She became flagship, RADM H. R. Thurber with midshipmen for a cruise to Cherbourg and Lisbon. She started her second Korean tour on 5 March 1953.

Same route, Panama, Long Beach, Hawaii, Yokosuka, arriving on 5 April and relieving sister Missouri as flagship, VADM Joseph H. Clark 7th Fleet. On 12 April she bombarded Chongjin. In Pusan she hosted the the President of the Republic of Korea. Shelling resumed at Kojo 16 April, Hungnam 18 April, Wonsan 20 April, Songjin 23 April, Wonsan 1 May, Hodo Pando, Kalmagak at Wonsan and Chinampo, then Wonsan 27–29 May with silenced counter-fire, Kosong 7 June, Wonsan 24 June, and Kosong until 10 July, Wonsan 11–12 July, Hodo Pando, Kojo on 13 July, and Kosong on 22–24 July. The on 25 July 1953 Hungnam. Hr deployment off Wonsan was the last before the truce. Her crew had R&R at Hong Kong on 20 August. She trained off Japan and Formosa (Taiwan), visited Pusan to received from the president his Unit Citation to the 7th Fleet.

She was relieved by Wisconsin on 14 October and was back in Norfolk on 14 November. She resumed her training routine in the Atlantic with midshipmen, and fleet maneuvers. On 7 September 1955 she started her first deployment with the 6th Fleet, Mediterranean. She visited Gibraltar, Valencia, Cannes, Istanbul, Souda Bay, Barcelona and back on 7 January 1956. This summer with midshipmen she returned in Northern Europe. On 27 August was she flagship, VADM Charles Wellborn Jr. CiC 2th Fleet. From Lisbon, she sailed to Scotland for NATO exercises and had an official visit in Norway, visited by Prince Olav and back to Norfolk by 15 October, inactivated at New York Naval Shipyard, decommissioned, reserve at Bayonne on 21 August 1957. This was a long sleep or nearly ten years.

USS New Jersey in Vietnam

USS New Jersey en route for Vietnam off Oahu, 1968

As part as reports for Operation Rolling Thunder in 1965, studies some studies shown the usefulness of a battleship for shore bombardment, rather than using aircraft due to mounting losses. On 31 May 1967 Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara authorized a study to have USS New Jersey reactivated, and it received favorable reviews. In August 1967 it was decided to recommission her “for employment in the Pacific Fleet to augment the naval gunfire support force in Southeast Asia”. She appeared in better material condition than her sisters, having an extensive overhaul prior to decommission. She had a limited modernization during (20/40 mm AA guns removed, improved electronic warfare systems, radar). Recommissioned 6 April 1968 at Philadelphia under Captain J. Edward Snyder she started sea trials, achieving 35.2 knots (62.5 km/h; 40.5 mph) for six hours, quite an achievement for the class.

As the world’s only active battleship she left Philadelphia on 16 May for Norfolk, Panama, Long Beach on 11 June, some training, her armament from Mount Katmai, including ammunition transferred by helicopter at sea and she departed for Pearl Harbor, Subic Bay before and arrived on the gunline on 25 September. On the 30th she fired her first shots since 1953 on the 17th parallel. She destroyed PAVN targets near the DMZ, Tiger Island and other Viet Cong bunkers, supply depots, AA sites, and in October returned off Tiger Island and in the mouth of Song Giang River, coastal installations, concentrations at Nha Ky, Vinh caves and other objectives, helped by USS America, and batteries at Hon Matt Island.

On 16 October she helped the 3rd Marine Division with main and secondary guns, and to the 173rd Airborne Brigade north of Nha Trang. She entered the Van Fong bay for deeper strikes. On 25 October she supported the 3rd Marine Division as the following days and later off Cap Lay with counter battery fire and other objectives for several days.

She supported ops of the 1st Marine Div. at Da Nang and Point DeDe and in November operated for the southern II Corps near Phan Thiết and the 173rd Airborne Brigade. On 23 November she was relieved by USS Galveston, and supported the America Division.

On 25 November she made a rampag near Quảng Ngãi, and to Point Betsy near Hue for the 101st Airborne, and back to the 3rd Marine Division at Da Nang before R&R at Singapore on 9 December. On 26 December she bombarded Tuy Hòa for the SVN 47th Regiment and II Corps, then the 1st Marine Division on 3 January 1969.

On 10 February she supported the Korean 2nd Marine Brigade off Da Nang and crumbled an underground complex. On 14 February she was back south of the DMZ for the 3rd Marine Division and later Con Thien then on the 22th, helped a besieged observation post near the DMZ. On 13 March she sailed for Subic Bay and back on 20 March near Cam Ranh Bay for the Korean 9th Infantry Division. Then Phan Thiet and Tuy Hoa and by 28 March supported the 3rd Marine Division until 1 April, and back to Yokosuka for R&R, and left for home. She fired main 5,688 rounds, 14,891 secondary rounds in this major deployment. This ended her Vietnam war.

Late service

USS Iowa firing off Beirut 1984

Back home on 9 April she had been delayed by an action when North Korean jet fighters shot down an unarmed EC-121 Constellation over the Sea of Japan and she protected the carrier task force until the crisis eased. She was at Long Beach on 5 May 1969 and had an overhaul. On 22 August 1969 Secretary of Defense Melvin Laird declared she would be inactivated while Captain Robert C. Peniston took command for a short while as she joined the “mothball fleet” on 6 September at Puget Sound Naval with preinactivation overhaul, colors went down on 17 December 1969. But after another 13 years of “sleep” the cold war asked her to be reactivated in 1982.

She was selected for reactivation in the spring of 1981, towed from Puget Sound to Long Beach by July 1981 for modernization overhaul. She followed the line of sister ship Iowa and after all modernizations schemes were eliminated she was modernized while taking account of overpressure effects from her main battery on missiles and electronics.

She was recommissioned on 28 December 1982 at Long Beach as homeport. However her No. 3 16 in gun turret aft was welded shut and deactivated to be replaced by a VLS with 48 Tomahawk or Harpoon or even a STOBAR deck for V/STOL aircraft but the plans were dropped while the aft turret remained inactivated. Her upgrades complete she was mobilized for the Lebanese Civil War in 1983–1984 as part of a Multinational Force with Italian and French armed service while the US deployed the USMC and 6th Fleet.

The 18 April 1983 embassy bombing in West Beirut and August 1983 Israel withdrawal from Chouf District southeast of Beirut saw more brutal fighting and more Marines casualties, New Jersey being sent as support. On 28 November, after the Beirut barracks bombing she started operation, and started shelling on 14 December inland of Beirut. Bob Hope and his entertainers made a show onboard New Jersey on 24 December 1983. On 8 February 1984 she resumed fire at Druze and Shi’ite positions in the hills over Beirut. She notably flattened a Syrian command post in the Bekaa Valley.

However this weakened the neutral U.S. stanced and local Lebanese Muslims believed she took sides and acted accordingly. Her accuracy was also called into question after an investigation by Marine Colonel Don Price and made civilian casualties. Tim McNulty from Chicago Tribune. It seemed poor accuracy was caused by recently rebagged Powder lots which burn at different rates leading to some inconsistency, an issue later remedied by the Navy, locating additional powder supplies not remixed.

In 1986, USS New Jersey was shuffled to the Pacific Fleet and took the lead of her own battle group, cruising from Hawaii to Thailand as a show of force and freeing aircraft carriers from May to October. Battlegroup New Jersey also accompanied battlegroup USS Ranger (CV-61) and Constellation (CV-64). During her transit through the Sea of Okhotsk on 27–28 September 1986 she was agressively flew over by “Bear” and “Badger” bombers, “Hormone” helicopter, “May” patrol airplane and closed in by a Kara-class cruiser and two Grisha III frigates. After an overhaul at Long Beach until 1988 she was back to the on a surface action group cruising off Korea and be present at the 1988 Summer Olympics in Seoul, the to Australia for bicentennial celebrations.

In April 1989 her sister Iowa suffered a catastrophic explosion and there was a main battery ban on all battleship, eventually lifted. She made her final cruise in 1989 for Pacific Exercise ’89 in the Indian Ocean and Persian Gulf, and back home by February 1990.

Budget cuts saw her decommissioned at NS Long Beach on 8 February 1991 after 21 years service, the most of her class. Thus, she missed Operation Desert Storm in 1991 where Missouri and Wisconsin operated. She was towed to Bremerton, Washington, stricken by January 1995.

In 1996 she had to be maintained in the mothball fleet until the Strom Thurmond National Defense Authorization Act of 1999 maintining onli Iowa and Wisconsin on the Register, New Jersey was to be stricken. On 12 September she was towed to Washington and Philadelphia for restoration work and a planned donation as museum.

There was application from Bayonne, New Jersey, Home Port Alliance in Camden. Home Port Alliance was selected, conformed by Secretary of the Navy Richard Danzig on 20 January 2000 and by 15 October she was towed to Camden Waterfront, opened to the public. In 2004 she became a state historical place. In 2012 was created the nonprofit USS New Jersey Battleship Foundation, Inc. asking she was moved to Liberty State Park but she remained in Camden.

It should be underlined that USS New Jersey, as explained on a plaque at the entry, and on her command bridge, is the most decorated battleship in US History: For ww2 she earned 9 battle stars, 4 Korean War, 3 for Vietnam, 3 for Lebanon/Persian Gulf as well as the Navy Unit Commendation for Vietnam, Philippines and Korean Presidential Unit Citations.

USS Missouri (BB 63)

USS Missouri (BB 63)

The surrender ceremony aboard Missouri, 1st September 1945.

After occupation duties in late 1945, “might mo” sailed back home. After an overhaul at New York Naval Shipyard (notably Mark 13 FCS installed) and carribean refresher training she was back to New York. On 22 March 1946 she departed for Gibraltar to bring back the defunct Turkish ambassador in Istanbul, making a 19-gun salutes and departing on 9 April to Phaleron Bay, Piraeus as the civil war rages on. The idea was to create a counterweight presence to the Soviets pushing for concessions in the Dodecanese and access through the Dardanelles.

Sailing off on 26 April she stopped at Algiers, Tangiers and hit Norfolk on 9 May, then Culebra Island on 12 May for 8th Fleet Atlantic training maneuvers. She spent the rest of the year on the eastern coast. On 3 December she was hit by a star shell from USS Little Rock, killing one, wounding three.

She was at Rio de Janeiro on 30 August 1947 (Inter-American Conference/Hemisphere Peace and Security) and she hosted President Truman on 2 September for the Rio Treaty (Monroe Doctrine). She landed the president in Norfolk on 19 September, had an overhaul in New York until 10 March 1948 and made a refresher in Guantanamo Bay followed by midshipman and reserve training cruises. She had an helicopter detachment (two Sikorsky HO3S-1) for liaison and SAR. She left Norfolk on 1 November 1948 for a three-week Arctic training cruise, Davis Strait. She had another overhaul at Norfolk (23 September 1949 – 17 January 1950). It seems that President Truman refused to allow Missouri to be decommissioned despite advice from Secretary of Defense Louis Johnson, and later John L. Sullivan, CNO Louis E. Denfeld, mainly for personal reasons.

Captain William D. Brown took command on 10 December during overhaul and she trained, until 17 January 1950 when running aground off Old Point Comfort on a shoal close to the main channel. To free her, a noria of ships came to After off-load ammunition, fuel and food and she was refloated on 1 February with tugboats, pontoons and the rising tide. The Naval Board of Inquiry court martialle Brown and three officers. Relieved of command he was replaced by Captain Harold Page Smith on 7 February, and stayed in home waters for training duties until Captain Irving Duke took command on 19 April. She was mobilized for the Korean War soon after.

USS Missouri was never decommissioned, so she could be transferred to the Pacific Fleet quicky after preparations, sailing from Norfolk on 19 August to Asia, and upon instruction of emerfency, her

captain decided to go directly through a hurricane off the coast of North Carolina on 20 August. She lost her helicopers and needed a week of repairs in Pearl Harbor. She was at Kyūshū on 14 September, and became flagship RADM Allan Edward Smith. Being the first off Korea waters her first objective was Samchok on 15 September to divert attention from the Incheon landings. She would made regulat tours on the gunline, alternated to resupply missions, and by 10 October became flagship, RADM John M. Higgins, Cruiser Division 5. At Sasebo on 14 October she was now flagship of VADM A. D. Struble, CiC 7th Fleet. She operated with USS Valley Forge and was detached for bombardments on 12 to 26 October at Chongjin and Tanchon, Wonsan. She had the visit also of comedian Bob Hope for three performances aboard.

Firing over Korea

On 19 October 1950, the Chinese attack under General Peng Dehuai into North Korea suprised and pushed back UN troops and Missouri was called for delaying actions in early 1951, until 19 March. While supplying in Yokosuka, Capt. George Wright too command on 2 March. She went homr after sending 2,895 main and 8,043 secondary rounds. In Norfolk on 27 April she became flagship, RADM James L. Holloway, Jr., Cruiser Force, Atlantic Fleet. May-August saw her in midshipman training cruises to Europe. Her overhaul started on 18 October until 30 January 1952 and Captain John Sylvester too command.

After six months refresher she visited NyC for Navy Day celebrations, hosting c11,000 onlookers, and returned to Norfolk on 4 August to be prepared for a second tout of duty in Korea under Captain Warner Edsall, arriving on Yokosuka on 17 October.

Flagship of VADM Joseph J. Clark, 7th Fleet, she returned to naval gunfire support (“Cobra strikes”) in the Chaho-Tanchon area, Chongjin, Tanchon-Sonjin, Chaho, Wonsan, Hamhung, Hungnam from 25 October up to 2 January 1953. She lost an helicopter on 21 December whe used as gunnery spotter. In Sasebo she was used as conference HQ for General Mark W. Clark CiC UN Command, British Admiral Sir Guy Russell of the Far East Fleet on 23 January. She returned to the gunline, entering Wonsan and dealing with counter battery fire. Her five-inch guns sent 998 shells. Next she was off the Kojo area on 25 March and in all spent 2,895 main, 8,043 secondaries before her last tour arrived to its conclusion. Edsall had a fatal heart attack and was replaced by Captain Robert Brodie by 4 April. The battleship left Yokosuka on 7 April for home, Norfolk on 4 May;

Back home for home water service she became flagship, RADM E. T. Woolridge (Battleships-Cruisers, Atlantic Fleet) and started on 8 June a midshipman training cruise to Brazil, Cuba-Panama. RADM Clark Green (Battleship Division 2) broke his flag on her later as she started an overhaul in Norfolk from 20 November to 2 April 1954 , having her 16-inch guns replaced, and upgrades. Captain Taylor Keith took command and she became flagship, RADM Ruthven Libby, for anoother midshipman cruise to Europe: Lisbon, Cherbourg, and Cuba when bac. She sailed remarkably with the other three battleships of her class, the only time the four sailed together, generating films and photos aplenty. After preparations at Norfolk on 3 August, she sailed on the 23th to the West Coast reserve at Long Beach and San Francisco, being visited by tens of thousands as a farewall tour. She entered Seattle on 15 September and saw the off-load of ammunition at Bangor before being decommissioned on 26 February 1955 at Puget Sound, Pacific Reserve Fleet. Moored at the last pier of the reserve fleet she could still be visited and became a popular tourist attraction (250,000 visitors yearly). So much so historical display were made on her “surrender deck” woith a bronze plaque for the Tokyo Bay surrender. She would stay there for decades, not reactivated for Vietnam.

Under the 600-ship Navy under secretary John F. Lehman, she was reactivated, towed to Long Beach in the summer of 1984 for modernization with a skeleton aboard working around the clock, and recommissioned in San Francisco on 10 May 1986, with Captain Albert Kaiss in command, then Captain James A. Carney on 20 June. After a brief refresher and sea trials she left Long Beach for her round-the-world cruise via Pearl Harbor, Sydney, Hobart, Perth, Diego Garcia, Suez Canal, Istanbul, Naples, Rota and Lisbon, then back to Panama and the West Coast. She became the only US battleship to to do so after the “Great White Fleet”, including the former USS Missouri (BB-11).

In 1987 the thteat of asymetric attack saw her equipped with 40 mm grenade launchers and 25 mm chain guns. She joined Operation Earnest Will, escorting reflagged Kuwaiti oil tankers in the Persian Gulf. This armament indeed repelled the Iarian Boghammar cigarette boats. On 25 July, she started another deployment in the Indian Ocean-North Arabian Sea with 100 continuous days at sea and part of Battlegroup Echo, watching over Iranian Silkworm missile launchers on her way to Ormuz.

She was back home via Diego Garcia, Australia, Hawaii in 1988, seeing Captain John Chernesky taking command in Pearl Harbor, just in time for RimPac ’88.

1989, saw her at Long Beach Naval for maintenance, and PacEx’89, with New Jersey off Okinawa, firing 45 main rounds, 263 secondaries. She stopped at Pusan, and later visited Mazatlan, Mexico. In early 1990, she was at RimPac under Captain Kaiss.

USS Missouri firing her secondaries during Operation Desert Storm on 6 February 1991

2 August 1990 saw the invasion of Kuwait and unlike her earlier suisters Iowa and New Jersey, USS Mirrouri and Wisconsin actively participated in the Gulf War, sent by George H. W. Bush as naval support for Operation Desert Storm in Saudi Arabia. Her WestPac in September was canceled and she was prepared with a detachment of AAI RQ-2 Pioneer UAVs for gunnery spotting. She sailed on 13 November 1990 for the Persian Gulf from Long Beach via Hawaii, the Philippines, stopping at Subic Bay and Pattaya in Thailand and the Strait of Hormuz on 3 January 1991. She started to launch Tomahawk Missiles and prepared for naval gunfire on 17 January 1991, launching 28 missiles in 5 days.

On 29 January, the frigate Curts escorted her for a first mission of bombardment for Desert Storm, blasting a Iraqi command and control bunker, then beach defenses in Kuwait, sending 112 main shells until relieved by sister USS Wisconsin, and 60 more rounds off Khafji on 11–12 February, then moved to Faylaka Island for 133 rounds in four missions for the amphibious landing feint on 23-24 February. The Iraqis fired two HY-2 Silkworm missiles at her, on crashing, the other intercepted by a GWS-30 Sea Dart from HMS Gloucester, crashing 700 yd (640 m) of the battleship’s bow. She launched her Pioneer drones and made a stike on the missile launchers with 50 rounds.

There was however a friendly fire incident with frigate USS Jarrett on 25 February, when the latter’s Phalanx CIWS engaged chaff fired by Missouri and some rounds ended on her deck, escept one piercing her bulkhead with one sailor injured. Missouri also blasted some 15 naval mines.

On 26 February, after spending 783 main rounds she started patrollong the northern Persian Gulf and departed for home on 21 March, stopping at Fremantle, Hobart, and Pearl Harbor. In Long Beach she hoster thousands of visitors in between training missions. One of her last was a 7 December 50th anniversary trip to Pearl hosting President Bush off Ford Island for the recemony.

The end of the cold war saw her decommissioned on 31 March 1992 at Long Beach, under Captain Albert L. Kaiss. She entered the reserve fleet at Puget Sound until 12 January 1995, and was stricken, not open to tourists. Discussioned for this led the US Navy to make her a symbol of the end of WW2 and by 4 May 1998, Secretary of the Navy John H. Dalton signed her transfer to the USS Missouri Memorial Association based in Hawaii, where she was towed from Bremerton via Astoria in the Columbia River to clean her hull, and arrived at Ford Island on 22 June, close to the Arizona Memorial. On 29 January 1999 she was opened as museum, where she remained since. She was placed in the National Register of Historic Places already on 14 May 1971 but not as National Historic Landmark due to her modernization, not reverted.

On 14 October 2009 she was planced in drydock at the Pearl Harbor NyD for overhaul at $18 million (anti-corrosion coatinh, new paint, etc. internals overhauled), leaks corrected. By January 2010 she returned to Battleship Row for a grand reopening on 30 January and by 2018 she saw a $3.5 million refurbishement of her superstructure. She was shot in “If I Could Turn Back Time”, the 1992 film Under Siege, and 2012 sci-fi “Battleship”, hosting tens of thousands of visitors to this day.

USS Wisconsin (BB 64)

USS Wisconsin (BB 64)

USS Buck (DD-761), USS Wisconsin (BB-64) and USS Saint Paul (CA-73) Steaming in close formation during operations off the Korean coast. Photo is dated 22 February 1952. Official U.S. Navy Photograph, now in the collections of the National Archives.

Postwar service, decommission and reserve

After Japan, Wisconsin headed for Okinawa, to embark GIs on 22 September 1945 for a single run as part of Operation Magic Carpet to Pearl Harbor and San Francisco by 15 October and later via Panama to the East Coast in 1946, then Hampton Roads on 18 January. After a refresher cruise to Cuba she had her major overhaul at Norfolk. She made a refresher off South America, stopping at Valparaíso, Callao, Balboa, La Guaira and back to Norfolk on 2 December 1946. In 1947 she became training for reservists and short cruises. Typically Bayonne-Guantánamo Bay and Panama. By June-July 1947 she brought Naval Academy midshipmen to northern Europe. January 1948 she was in the Atlantic Reserve Fleet, Norfolk, inactivated, decommissioned on 1 July.

June 1950, saw her reactivated for Korea, recommissioned on 3 March 1951 with Thomas Burrowes in command, and she made shakedown to Edinburgh, Lisbon, Halifax, NyC and Guantánamo Bay and back. She had grounded on mud flats in New York Harbor freed on 23 August 1951.

The Korean War

Wisconsin departed on 25 October via Panama Canal, San Diego, Hawaii to Yokosuka on 21 November, relieving USS New Jersey as flagship (VADM H. M. Martin, 7th Fleet) and RADM F.P. Denebrink (Service Force Pacificcaeme aboard also in Yokosuka. She supported TF 77’s air operations, detached on 2 December with USS Wiltsie to shell the Kasong-Kosong area and cover the 1st Marine Division.

After some rampage she was relieved by the USS Saint Paul on 6 December and after R&R went to the Kasong-Kosong area with USS Twining. RADM H. R. Thurber (BatDiv 2) came by helicopter aboard for inspection. Naval gunfire resumd until 14 December to the Kojo area and she was visited on 15 December by Admiral Thurber until R&R at Sasebo.

USS Wisconsin (BB-64) Fires a three-gun salvo from her forward 16/50 gun turret, during bombardment duty off Korea. Photograph is dated 30 January 1952. Official U.S. Navy Photograph, now in the collections of the National Archives.

Back on 17 December with Senator Homer Ferguson aboard she supported the 11th ROK by night while Ferguson left for USS Valley Forge. The 20th, she shelled Wonsan in port and made a sweep against shipping northwards, and shelling until 22 December. Cardinal Francis Spellman was aboard for Christmas. After R&R at Yokosuka she was in Pusan on 8 January 1952 to be honored by Syngman Rhee on 10 January. Next she covered the 1st Marine Division and 1st ROK Corps. After another R&R at Sasebo she was back with TF 77 for shelling on 23 January to the Kojo area, and destroyed the 15th North Korean Division HQ. Next she shelled Hodo Pando, Kojo and Kosong area, then headed for Pusan on 26 February, visited by VADM Shon (ROK CNO) and Ambassador J.J. Muccio, RADM Scott-Montcrief of the RN with TG 95.12. She shelled Songjin on 15 March and silenced four heavy battery (155 mm) field guns which hit her, starboard 40 mm mount destroyed, three injured. She was relieved as flagship on 1 April by USS Iowa and after R&R at Yokosuka left for home via Guam floating dry dock on 4–5 April, Pearl Harbor then Long Beach on 19 April, Panama and Norfolk.

Inter-reserve service 1950-58

On 9 June, Wisconsin returned to training ship routing with midshipmen. She stopped at Greenock and Brest. She took part in NATO exercise Operation Mainbrace, which was held out of Greenock, Scotland. After overhaul she served from 1952 to 1953 with midshipmen and on 9 September 1953 was recalled to the pacific, to Japan, and relievin New Jersey as flagship on 12 October. She spent Christmas at Hong Kong and was relieved on 1 April 1954, back to Norfolk via Long Beach in May and in the Naval Shipyard on 11 June for a short overhaul, resuming midshipman training cruises and later Atlantic Fleet exercises as flagship 2nd Fleet. January 1955 was Operation Springboard, visiting Port-au-Prince in Haiti. During her next midshipmen cruis she stopped at Edinburgh, Copenhagen. After a major overhaul at NyC Naval Shipyard, refresher training, Springboard exercise where she visited Mexico and Colombia, she was back to HP by March 1955. On 19 October she grounded in the East River, Ny harbour Harbor, freed in an hour.

April-May 1956 saw local operations but on 6 May she collided with the destroyer USS Eaton in heavy fog and had her bow repaired. Later in Norfolk she had 120-ton, 68 foot (21 m) bow section replaced, from USS Kentucky carried by barge in one section, work done in 16 days. On 28 June 1956 she was underway for a new cruise and Atlantic Fleet exercises and other maintenance at Norfolk until 2 January 1957. She served at the Naval Station Guantánamo Bay, hosting Admiral Henry Crommelin as flagship for exercises off Culebra, Puerto Rico in February. 27 March saw her departing for a first tour in the Mediterranean 6th fleet, TF 60 in the Aegean Sea and Turkey for NATO’s Red Pivot.