Japan, 1938-42. Fleet Aircraft Carrier

Japan, 1938-42. Fleet Aircraft CarrierWW2 IJN Aircraft Carriers:

Hōshō | Akagi | Kaga | Ryūjō | Sōryū | Hiryū | Shōkaku class | Zuihō class | Ryūhō | Hiyo class | Chitose class | Mizuho class* | Taihō | Shinano | Unryū class | Taiyo class | Kaiyo | Shinyo | Ibuki |Soryū’s near sister ship

IJN Hiryū was the second purpose-built medium fleet aircraft carrier, and near-sister ship of IJN Soryū, the “blue dragon”. She shared most caracteristics, powerplant, armament, armor scheme, general layout, but with significant changes as well, like the island’s position, higher freeboard, better protection and other improvements. Both carriers operated together in the Kido Butai, made the Indochina campaign, China blockade, Pearl Habor raid, Indian Ocean raid and many operations in between, but also sharing the same fate at Midway in June 1942.

Design development of the “flying dragon”

Colorzed rendition by Irootoko Jr. of IJN Hiryu in 1939.

Hiryū (飛龍, “Flying Dragon”) was the second of the two large medium fleet aicraft carriers approved, under the 1931–32 Supplementary Program. Basically the same design as her earlier sister ship of IJN Sōryū was used, with some paths of improvements in details, but not changing the overall plans. However two events were suddenly changing all this: The Tomozuru incident in 1934 (when the torpedo boat broke in two in foggy circumstances) and Fourth Fleet incidents the next year during a typhoon. They all revealed that many IJN ships built at the time were top-heavy, unstable, with an inherent structural weakness. As a result, it was asked a revision of these plans to take these into account.

The second carrier had her forecastle redesigned, raised to avoid “ploughing” in heavy weather, resulting of hangar flooding like for the erlier Ryujo.

She also would have her hull radically strengthened, with supplementary steel bracing, additional plates.

The most radical change overall was to increasing her beam, from 69 feets 11 inches to 73 feets 2 inches.

The last point was to revise and improved armor protection.

But aside all this, the basic design was not changed much and was still the same as in Soryu: Same machinery & performances, same hangar and installations (but the island that was placed on the other side), same arour arrangement and general scheme, same armament and same aircraft carrying capacity.

All these efforts culminated into a new design approved for construction in January 1936, two months after her sister ship was launched already. More design details were perfected until the ship was won by Kawasaki Naval Arsenal, her keel laid down eventually on 8 July 1936. Meanwhile, her sister-ship was fitting out in Kure.

Detailed Design

Hiryu’s hull was 227.4 meters (746 ft 1 in) long overall, for a beam of 22.3 meters (73 ft 2 in) and 7.8 meters (25 ft 7 in) draft, displacing 17,600 metric tons (17,300 long tons) standard, and up to 20,570 metric tons (20,250 long tons) fully loaded. So she was beamier, slightly shorter, and with a deeper draught than her sister ship, and unsurprisingly, heavier, of almost 1500 tons. She had a complement of 1,100 officers and enlisted men.

Armour protection

Protection overall was still weak as the dominant factor was still speed over protection. She was given nevertheless compared to Soryu a waterline belt with 150 millimeters (5.9 in) of ducol steel plating over the magazines, reduced to 90 mm (3.5 in) over the machinery space. Another layr of the same thickness was provided to the avgas storage tanks, was backed by an internal splinter spall lining in the bulkhead. The main armor deck was 25 mm (0.98 in) over the machinery spaces, and more than double at 55 mm (2.2 in) over the magazines and aviation gasoline storage tanks.

Powerplant

Hiryū’s machinery was basically the same as Soryū’s, as she was fitted with four geared steam turbine mated each on one propeller shaft (inner and outer). They were provided steam from eight Kampon water-tube boilers and the whole powerplant basically was copied from the excellent Mogami-class cruisers design. Together these turbines generatd an output of 153,000 shaft horsepower (114,000 kW). The hull design at the water line was the same, she kept the slim, cruiser-type shapes, still with an excellent with a length-to-beam ratio of 10:1.

Less than her sister ship, but still lagely sufficient to reach 34.3 knots (63.5 km/h; 39.5 mph), so the second fastest carrier in the world when commissioning in 1937.

To put things in perspective it was almost as fast as most destroyers of the time. For autonomy, she carried 4,500 metric tons (4,400 long tons) of fuel oil, allowing to cross 10,330 nautical miles (19,130 km; 11,890 mi) at 18 knots (33 km/h; 21 mph). Like her sister, boiler uptakes were trunked starboard amidships exhausted below the flight deck level into two funnels curved downward so as to avoid smoke interference on the flight deck. This was result of earlier reconstructions and trials made on Akagi and Kaga.

IJN Hiryu underway in 1940

Armament

The same scheme as the Soryu was kept:

Primary Armament:

Six twin-gun mounts, dual purpose 50 cal. (127 mm) Type 89. They were mounted on projecting sponsons, three pre side along the hull, four forward and two aft. However they had the same disposition as for Soryu: They were mounted too low to cover anything else than 180° of their side, not having covering arcs over the flight deck.

Specs: Range of 14,700 meters (16,100 yd), ceiling 9,440 meters (30,970 ft) at +90 degrees, rate of fire 8-14 rpm. To assist them, two Type 94 fire-control directors were mounted, one on a sponson port, and the other starboard director on the island’s roof, which was able to direct all Type 89 guns if needed.

Light AA Armament:

Hiryu’s light AA comprised fourteen twin-gun mounts Type 96, 25 mm (1 inch). These were license-built Hotchkiss models, derived from earlier 12.7 mm models, and using fifteen-round clips magazines. Each mount needed five, two loaders, two pointers and the commander. Three were located on the platform below the forward end of the flight deck, two close to the funnels and five opposite, split in two groups, two forward of the island and three behind.

The problems of these AA mounts, unfortunately the standard for the IJN, was well known during WW2: Slow to train and elevate, with inadequate sights, excessive vibration and a blinding muzzle blast. Practical range 1,500–3,000 meters (1,600–3,300 yd), ceiling of 5,500 meters (18,000 ft) at +85 degrees, 110-120 rpm. They were controlled by five Type 95 directors, two on either side, one in the bow.

Hangar and aircraft facilities

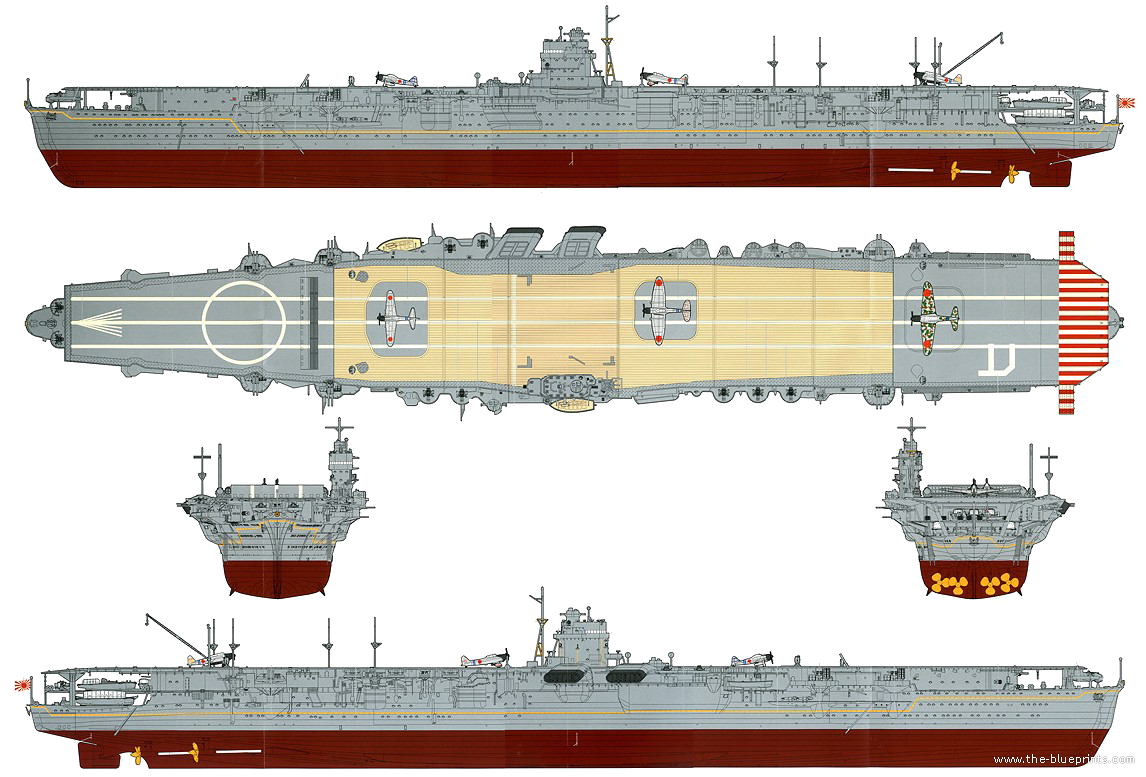

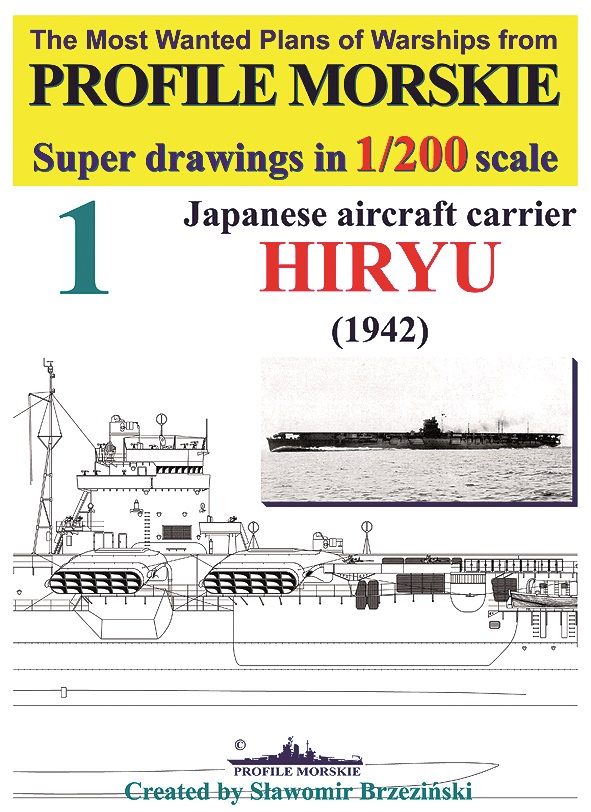

The blueprints, 5 views of the Hiryu

Naturally due to the slender lines of the hull and usage of the time, the flight deck was shorter than the hull, with just 216.9-meter (711 ft 7 in) in overall lenght and 27 meters (88 ft 6 in) in width. Naturally it overhung at both ends, with two pairs of pillars fore and aft pairs of pillars. Major difference here was the forward section of the hull being one deck higher, they were shorter and thus stronger forward.

IJN Hiryū however distinguished herself from all previous carriers in the sense her island was on the port side, but Akagi. It was also positioned to the rear which was very unusual, and encroached on the flight deck, unlike Sōryū which had it on a sponson extension. Why doing this ? -Japanese engineers indeed rode about a naval aviation study published in 1935 which stated that, according to the latest statistics about planes landings and taking off from existing aircraft carriers, the best position was not forward, but amidship as in Kaga. This was pplied on the rebuilding Akagi. Howver on Hiryu the engineers were soon prevented to place it as expected due to the position of the exhaust funnels starboard, they had to move it further aft on port. This ultimated arrangement proved problematic in operations as seen in 1937: Combined with the location further on the deck, there was an even greater degree of turbulence, for landing planes, and this was never repeated.

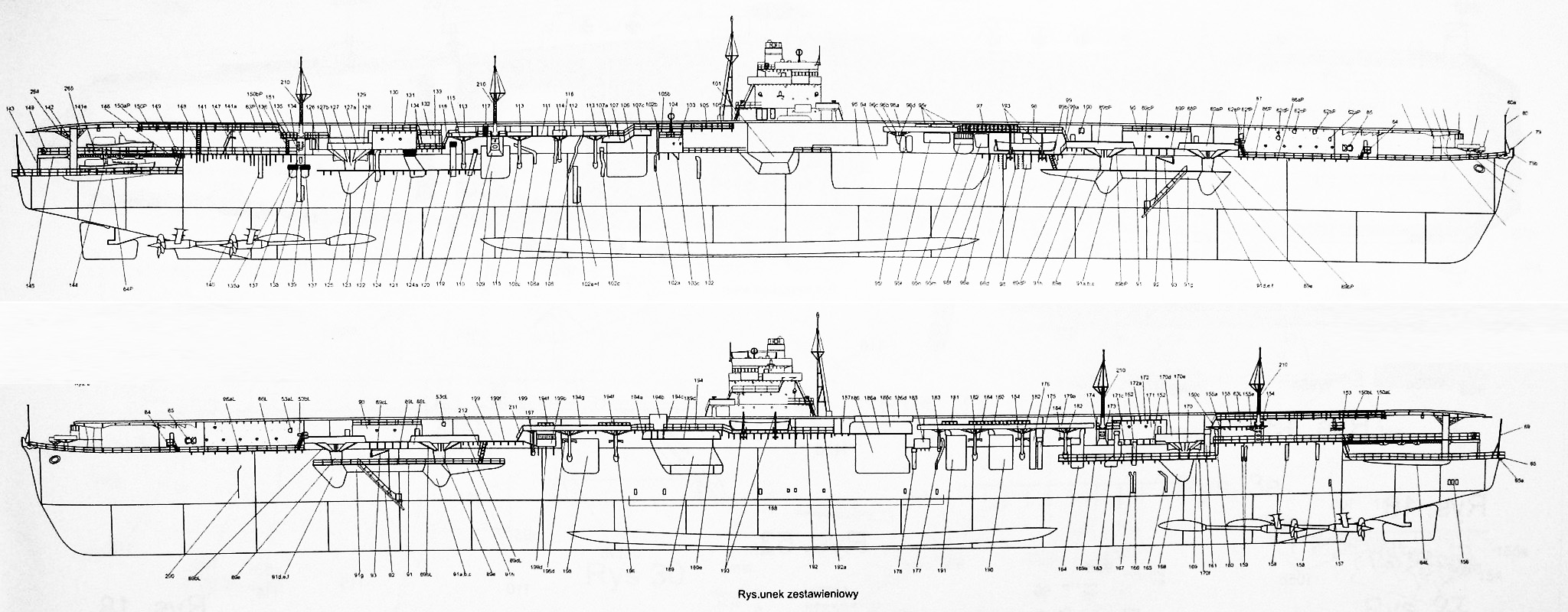

Extract from the 1/200 Angraf model kit

Soryu was fitted with nine transverse arrestor wires aft, which could stop a 6,000-kilogram (13,000 lb) aircraft, seemingly sufficient for the nimbler biplanes of the time, even large torpedo planes fully loaded. There was a first group of three wires further forward to land aircraft over the bow, but this never happened in practice. Like for Soryu, the flight deck was just 12.8 meters (42 ft) above the waterline. It was not immune to water spray in heavy weather, which could cause degradation of the parked aircraft and hinder operations. The designers kept both stacked hangars low due to measured for combating stability issues, mastering their metacentric height, the absolute counter example being Ryujo.

The upper hangar was 171.3 m long (562 feets), 18.3 meters (60 ft) wide and around 4.6 meters (15 ft), which was still tight for some models. The lower hangard measured 142.3 by 18.3 meters (467 ft by 60 ft) for around 4.3 meters (14 ft) hight, better fitted for fighters. Total approximtive area was 5,736 square meters (61,740 sq ft), causing still handling problems: The wings of a the last adopted Nakajima B5N “Kate” torpedo bomber were too long to be spread, nor folded, even in the upper hangar. They were parked permanently on deck. She carried 1270 tons of aviaton gazoline, a fuel stowage increased by 20% compared to her sister ship.

Both the flight deck and upper hangar were served by three elevators: A forward one, abreast the island, centerline and the two aft, offset to starboard. The forward one (largest) had a superficy of 16 x 13 meters (52.5 ft × 42.75 ft), the middle was 13 x 12 meters (42.75 ft × 39.3 ft), the aft one 11.8 x 13.0 meters (38.7 ft × 42.8 ft). Their useful capacity was 5 tons (11,000 lb). Hiryū carried 64 plus plus nine spares wich was a bit better than her sister. Like the latter she also had a folding safety net aft, abreast the rear main 5-in turrets, and before the wooden deck section. There were three of these. The forward section and the aft ones both were in metal. Wooden surfaces covered hardly more than 50% of the total flight deck area.

Onboard aviation

Mitsubishi A5M4 in 1940 (IJN Soryu)

Yokosuka B4Y1 1938 (Akagi)

Aichi D1A in 1939 (Kaga).

-December 1939: Her initial air group in 1939 (possibly since her commission in July-August) included the transitional, late interwar bunch of sixteen Mitsubishi A5M2 “Claude” fighters monoplanes (fixed undercarriage), twenty Aichi D1A2 “Susie” biplane dive bombers, and 38 Yokosuka B4Y1 “Jean” torpedo bombers biplanes.

–December 1941: For Pearl Harbor she had a new air group comprising 23 A6M2 zero “Zeke” monoplane fighters, 17 Aichi D3A1 “val” monoplane dive bombers (fixed undercarriage) and 18 also modern Nakajima B5N2 “kate” torpedo bombers.

–June 1942: At Midway, she carried the same 21 Mitsubishi A6M2 fighters, but 21 D3A1 “val” and 21 B5N2 “kate” for a total park of 63 planes, its maximum capacity (plus spares).

Mitsubishi A5M “Claude” (1935) first IJN monoplane, open cockpit (later enclosed) fixed undercarriage. It was replaced in 1941.

Mitsubishi A6M “Zeke” (1940) The legendary A6M2 was her main fighter from Pearl Harbor to Midway.

Aichi D1A “Susie” (1934) Retired in 1940.

Aichi D3A1 “Val” (1938) Introduced from 1940. In December, the pilots had alost two years to train. They will prove deadly at Pearl Harbor

Yokosuka B4Y “Jean” (1935) Seeing the peak of the Sino-Japanese war, retired in 1939 or 1940.

Nakajima B5N “Kate” (1937) A splendid cantilever, all duralumin monoplane, built with state of the art tech when introduced. This was probably the best of any type worldwide in 1938, but obsolete by 1942. Replacement was on its way, but Hiryu would never experience it.

Author’s illustration of IJN Hiryu in May 1942

IJN Soryu to compare

⚙ Specs 1937 |

|

| Dimensions | 227,4 m (740 ft) x Beam 22.32 m (73 ft) x Draught 7.84 m (30 ft) |

| Displacement | 17,300 long tons standard, 21,900 long tons FL |

| Propulsion | 4 shaft geared steam turbines, 8 Kampon boilers 153,000 shp |

| Speed | 34.3 knots (64 km/h; 40 mph) |

| Range | 7,750 nmi (14,350 km; 8,920 mi) at 18 knots (33 kph, 21 mph) |

| Armor | Belt 90 mm (3.8 in), 56-150 mm magazine decks, 25 mm engine decks |

| Armament | 6×2 12.7 cm (5 in) DP, 31x 25 mm (1 in) AA, 73 planes |

| Crew | 1100 |

Sources/ Read more

Links

Warships After London: The End of the Treaty Era in the Five Major Fleets By John Jordan.

tabular movements combinedfleet.com

On wrecksite.eu

Midway on nationalww2museum.org

Aircraft Carriers: A History of Carrier Aviation and Its Influence on World, By Norman Polmar

On ww2db.com

Dutch Maritime Disasters in the Dutch East Indies, 1941-1942

U.S. Marine Corps Aviation Volume Five of a Commemorative Collection

On navyreviwer channel

Hiryu improvements on yamato30 channel

Commissioning, stock footage

Books

Sturton, Ian (1980). “Japan”. In Chesneau, Roger (ed.) Conway’s all the world’s fighting ships 1922-477

Bōeichō Bōei Kenshūjo (1967), Senshi Sōsho Hawai Sakusen. Tokyo

Brown, David (1977). WWII Fact Files: Aircraft Carriers. New York: Arco Publishing

Brown, J. D. (2009). Carrier Operations in World War II. Annapolis

Stille, Mark (2011). Tora! Tora! Tora:! Pearl Harbor 1941. Raid. 26. Osprey, Oxford

Campbell, John (1985). Naval Weapons of World War Two. Annapolis

Chesneau, Roger (1995). Aircraft Carriers of the World, 1914 to the Present: An Illustrated Encyclopedia

Condon, John P. (n.d.). U.S. Marine Corps Aviation. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office

Hata, Ikuhiko; Izawa, Yasuho & Shores, Christopher (2011). Japanese Naval Air Force Fighter Units and Their Aces 1932–1945.

Jentschura, Hansgeorg; Jung, Dieter & Mickel, Peter (1977). Warships of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1869–1945. Annapolis

Lengerer, Hans (2010). “Katsuragi and the Failure of Mass Production of Medium Sized Aircraft Carriers”. In Jordan, John (ed.). Warship 2010. Conway

Lundstrom, John B. (2005). The First Team: Pacific Naval Air Combat from Pearl Harbor to Midway (New ed.). Annapolis

Parshall, Jonathan & Tully, Anthony (2005). Shattered Sword: The Untold Story of the Battle of Midway. Dulles, Potomac Books

Peattie, Mark (2001). Sunburst: The Rise of Japanese Naval Air Power 1909–1941. Annapolis

Polmar, Norman & Genda, Minoru (2006). Aircraft Carriers: A History of Carrier Aviation and Its Influence on World Events. 1, 1909–1945. Potomac Books.

Shores, Christopher; Cull, Brian & Izawa, Yasuho (1992). Bloody Shambles. I: The Drift to War to the Fall of Singapore. London

Shores, Christopher; Cull, Brian & Izawa, Yasuho (1993). Bloody Shambles. II: The Defence of Sumatra to the Fall of Burma. London

Silverstone, Paul H. (1984). Directory of the World’s Capital Ships. NY Hippocrene Books.

Stille, Mark (2011). Tora! Tora! Tora!: Pearl Harbor 1941. Raid. 26. Osprey

Stille, Mark (2007). USN Carriers vs IJN Carriers: The Pacific 1942. Duel. 6. Osprey

Zimm, Alan D. (2011). Attack on Pearl Harbor: Strategy, Combat, Myths, Deceptions. Havertown, Casemate Publishers.

The model’s corner

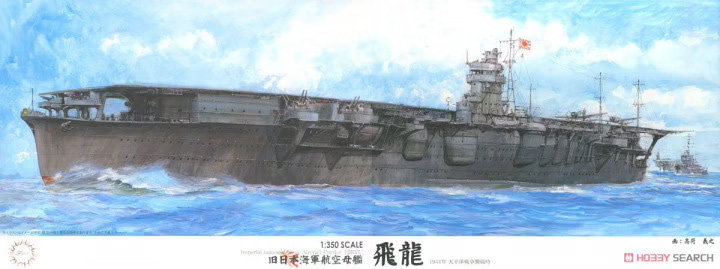

1/350 kit boxart

Sea Way Model (EX) Series The Battle of Midway First Carrier Division Akagi & Kaga, Second Carrier Division Soryu & Hiryu Set, Fujimi 1:700

IJN CV Hiryu Bridge w/Flight Deck Kami de Korokoro 1:144

Aircraft Carrier Hiryu Outbreak of War Version / Battle of Midway / with 43 Aircraft Fujimi 1:350

IJN Aircraft Carrier Hiryu w/Stand Nichimo 1:500

Water Line Super Detail Series Hiryu 1942 Japanese Aircraft Carrier Aoshima 1:700

Hiryu 1939 Japanese Aircraft Carrier Aoshima 1:700

IJN Aircraft Carrier Hiryu Full Hull Fujimi 1:700

Hiryu XP Forge 1:1200

IJN Hiryu’s career

Pre-Pearl Harbor service

Pre-Pearl Harbor service

Captain Kaku Tomeo

The “Flying Dragon” left Yokosuka Naval Arsenal after 16 November 1937 to be fitted out in Kure. She was commissioned unde command of Captain Yanagimoto Ryusaku on 5 July 1939, and assigned to the Second Carrier Division, on 15 November. By September 1940 her air group was transferred to Hainan Island to prove cover for operations in French Indochina. In February 1941, she participated in the blockade of Southern China and 10 April saw the 2nd Carrier Division (now Rear Admiral Tamon Yamaguchi) grouped with the First Air Fleet (Kido Butai). Hiryū was back home on 7 August for a refit, until 15 September. She became flagship, 2nd division from 22 September to 26 October as Sōryū was also in refit. The latter was the normal flagship.

In July 1941, she took part in operation “FU-GO” as part of the Escort Fleet, Departing Yokosuka with HIRYU and on 14 July 1941, Cardiv 2 arrived at Mako, then proceeded to days later at Samah while air groups are flown off to land bases for future operations inland. On 25 July 1941, they departed, mission accomplished, to join Crudiv 7 (KUMANO, SUZUYA, MIKUMA, MOGAMI) and DesDiv 23 in support of an invasion convoy of 39 transports bound for Saigon, covered by the Third Fleet (flagship ASHIGARA, Desron 5, NAGARA, five destroyers). On 28 July 1941 landings near Saigon started unopposed and on 29-30 July 1941 CarDiv 2 retired to Condor and St. James, then Samah, departing again for home nd arriving on 7 August 1941 at Kagoshima. There, she was assigned as flagship, ComCarDiv 2, staying in Kyushu waters until 6 September 1941 whe she departed for Tokyo Bay.

Two days later she was in Yokosuka and on 22 September, ComCardiv 2 flag was transferred to Soryu as she Entered drydock for a short refit, until 8 October 1941. On 26 October 1941 she was in Kagoshima and on 18 November 1941 departed for Hitokappu Bay, arrving on 22 November 1941 to gather wih the rest of Kido Butai for future operations.

IJN Hiryu in 1939

Pearl Harbor attack

In November 1941 the Combined Fleet (Yamamoto) prepared for a formal war with the United States and a raid on Pearl Harbor. Preparations commenced on 22 November when Hiryū (Captain Tomeo Kaku) departed under orders of Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo 1st, 2nd and 5th CarDiv from Hitokappu Bay, off Etorofu Island on the 26th, following a north-central Pacific course in the middle of nowhere (crossing no commercial routes) in total radio silenced. Instead, communication within the fleet was done with more signals when possible, but the weather soon deteriorated. The feleet arrived unspotted about 230 nmi (430 km; 260 mi) north of Oahu when at noon, all carriers launched the first waves on 7 December, Hawaiian time.

Concerning Hiryu, her 8 B5N torpedo bombers were tasked to target aircraft carriers normally berthed on the northwest side of Ford Island. Of course fat had it none were present. So four pilots decided to fall down to their secondary targets, ships berthed alongside “1010 Pier”. There, was USS Pennsylvania in drydock, next to the light cruiser Helena and minelayer Oglala. The torpedoes missed in this difficult spot. The other four pilots attacked USS West Virginia and Oklahoma and remaining B5Ns were equipped with 800 kg (1,800 lb) AP tipped bombs, falling on Battleship Row, notably wrecking USS Arizona. A6M Zeros meanwhile strafed parked aircraft at MCAS Ewa).

Soon, Soryu launched her second wave 18 D3As escorted by 9 Zeros.

One aborted due to engine problems, and the fighters later strafed Naval Air Station Kaneohe Bay and Bellows Army Airfield. They shot down two Curtiss P-40 fighters taking off, destroyed a B-17 diverted from Hickam and short down a Stinson O-49 on the ground, loosing one. This still with ammo strafed MCAS Ewa. D3As meawxnhile attackd various ships, but it’s unclear what they hit. Two D3As were lost during the attack, one being short down by George Welch’s P-40, one of the rare in the skies that day.

Wake, Ambon, Borneo, Darwin, Java

Back to Japan, Nagumo ordered CarDiv 2 (Sōryū and Hiryū) be detached on 16 December to raid Wake Island, recently defeating a first attack. They arrived on 21 December, launching 29 D3As and 2 B5Ns escorted by 18 Zeros combined as a first wave. Without no serious aerial opposition, they launched a second wave of 35 B5Ns and 6 A6M Zeros the next day, intercepted by two surviving F4F Wildcats from VMF-211, which shot down 2 B5Ns, before engaged by the flight commanded by Isao Towara. The garrison surrendered later as the landing was made.

Both carriers were back in Kure on 29 December, assigned to the Southern Force (8 January 1942), departing later for the Dutch East Indies. They covered the invasion of the Palau Islands and the Battle of Ambon, strafing and bombing Allied positions on 23 January 1942, with 54 aircraft making round the clock sorties. Four days later they separated from 18 Zeros and 9 D3As landed to operate from land bases for the next operation, the Battle of Borneo. Hiryū was back in the Palaus on 28 January, waiting for CarDiv 1 (Kaga and Akagi). All four departed on 15 February to join a position ideal for launching the famous raid on Darwin, the “Australian Pearl Harbor”, four days later. Hiryū for her part launched 18 B5Ns, 18 D3As, escorted by 9 Zeros. Her fighters claimed a single P-40E as it was taking off and two Consolidated PBY Catalinas in the water, but she lost a Zero, shot down by a P-40E of the USAAF’s 33rd Pursuit Squadron.

Next Hiryū and two divisions arrived at Staring Bay, Celebes Island, on 21 February in order to resplenish. They departed four days later in support of the the invasion of Java. On 1 March 1942, her D3As damaged the destroyer USS Edsall, later finished off by Japanese cruisers. Her dive bombers sank the oil tanker USS Pecos and combined 180 aircraft ro raid Tjilatjap on 5 March. On the 7th, they attacked Christmas Island. IJN Hiryū’s aircraft sank the Dutch freighter Poelau Bras. They later resupplied at Staring Bay on 11 March preparing for the next big operation southwards, the Indian Ocean raid. It targeted Burma, Malaya, and finishing off the Dutch East Indies. Next long term plans included Madagascar and eventually controlling the exit to the Suez Canal to completely block allied access to the Pacific, but from the US west coast.

The Indian Ocean Campaign

Indian Ocean raid fleet, April 1942

On 26 March, the Kido Butai set sail from Staring Bay, later spotted by a Catalina, 350 nautical miles southeast of Ceylon, early on 4 April. Hiryū’s Combat Air Patrol zeros were part of the force shooting it down, ut not before alert was give. Nagumo arrived 120 nautical miles of Colombo in the evening to launch the fist airstrike the following morning. Meawnhile, a powerful British Force, still inferior to the Kido Butai, was refuelling far from there. The initial plan to attack it in a pincer has failed to this point. For the strik on Colombo, Hiryū flew off 18 B5Ns escorted by 9 Zeros, meeting over their objective six Fairey Swordfish torpedo bombers (788 NAS) en route to attack the fleet. They were all shot down.

Later the force met interecpting Hawker Hurricanes (N°30 and 258 Sqn, RAF), over Ratmalana airfield. Hiryū’s zeros claimed no less than 11, with just 3 Zeros damaged but this contradicts British claims. Total losses were 21 Hurricanes shot down, 2 more crash landed. D3As and B5Ns damaged the port but failed to sink the bulk of the shipping, which was allready departed after the alert was give. Nagumo’s fleet was searched in vain by the British, while Hiryū’s CAP zeros claimed another RAF Catalina, a Fairey Albacore and drove a squadron from HMS Indomitable. Cornwall and Dorsetshire were later spotted and Hiryū’s 18 D3As combined with those of other three carriers sank both.

On April, 9, Hiryū’s CAP claimed their third Catalina, caught while searching for Nagumo. Later a wave of 18 B5Ns escorted by 6 Zeros took off from her flight deck to attack Trincomalee. They met over the objective the 261 Squadron RAF, claiming two plus two shared, but the Japanese claimed 49 in all, the British giving a total of just eight fighters, since this was already half of the 16 Hurricanes engaged from 261 Sqn. One of Hiryū’s B5Ns was short down and another crash landed over the port. Haruna’s floatplane meanwhile on patrol spotted HMS Hermes and her escort HMAS Vampire. All available D3A took off escorted by nine Zeros, including 18 from Hiryū. They arrived too late (they had been sunk already) but found further north the freighter RFA Athelstone and escorting corvette HMS Hollyhock, both sunk.

Meawnhile Nagumo’s fleet was attacked by a flight of 9 Blenheim, IJN Akagi being targeted, dodging bombs. These came from Ceylon and dropped their payload from 11,000 feet (3,400 m). Hiryū sent CAP’s Zeros added to 12 more to intercept them, vlaiming five, for one Hiryū’s Zero shot down. Blenheims on return met D3As from Shōkaku escorted by Hiryū’s Zeros, which claime done more. After mission accomplished, Nagumo ordered the First Air Fleet to headed southeast, for the Malacca Strait, to set for home.

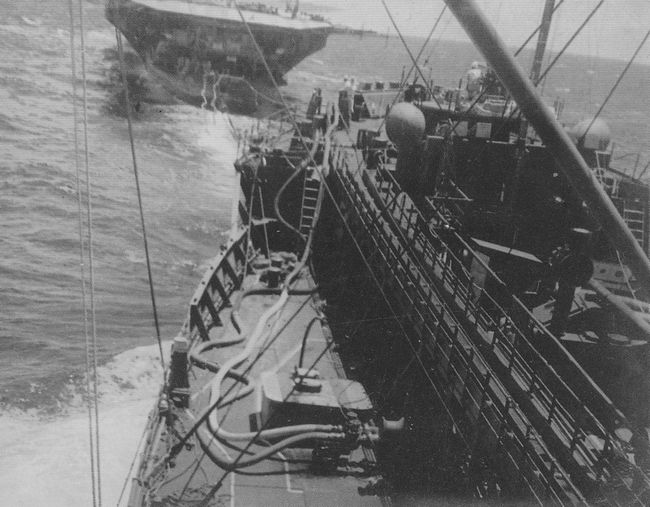

Hiryu’s stern seen from Kyokuto Maru in 1942

On 19 April though the Bashi Straits (Taiwan-Luzon) Hiryū, Sōryū, and Akagi were suddenly re-routed to chase the USS Hornet and USS Enterprise back from the Doolittle Raid, but missed them. The Kido Butai dropped anchor in Hashirajima on 22 April, and the ships were (as their tired crews) in dire need for rest, maintenance and repairs. but this was made quick, as the Combined Fleet’s next major operation was scheduled for May. Hiryū’s air group was based ashore, Tomitaka Airfield (Ōita pefecture) to train, as all the other squadrons from the Kido Butai. Officers and ratings took their leave.

Hiryu at Midway (6 June 1942)

USS Yorktown hit by Hiryu’s planes on 4 June 1942

Yamamoto planned next a showdown to eliminate for good the missed American carriers at Pearl Harbor, that were helping a multitude operations, the last of which was the raid on Tokyo. A good way to raw these forces was to invade Midway Atoll, too close from peark and Wake for comfort. Called “Operation MI”, US Intel unit soon decrypted the Japanese JN-25 code and prepared an ambush with all available carriers northeast of Midway. On 25 May 1942, Hiryū and the rest of the Combined Fleet (Kaga, Akagi, and Sōryū, so CarDiv 1 and 2) departed for the attack with a large aicraft complement, possbly 18 Zeros, 18 D3As, and 18 B5Ns or 21 of the latter. Three extra A6M fighters (6th Kōkūtai) were to be flown off and land as local garrison for Midway once the battle was over, such was the Japanese confidence.

The Kido Butai was positioned 250 nmi (460 km; 290 mi) northwest of Midway at dawn, on 4 June 1942. Hiryū contributed all her 18 B5Ns and nine Zeros out of a 108-plane strong firest wave airstrike, to destroy facilities on Sand Island. Two B5Ns were shot down by local fighters, a by AA fir a fourth, (sqn. leader Rokuro Kikuchi) badly damaged and crash-landing later on Kure Atoll. A fifth ditched on return, five more badly damaged and just beyond repair after landing, so ten out of 18. Never Hiryu’s air group suffered so badly since the start of hostilities. Two Zeros also landed badly damaged.

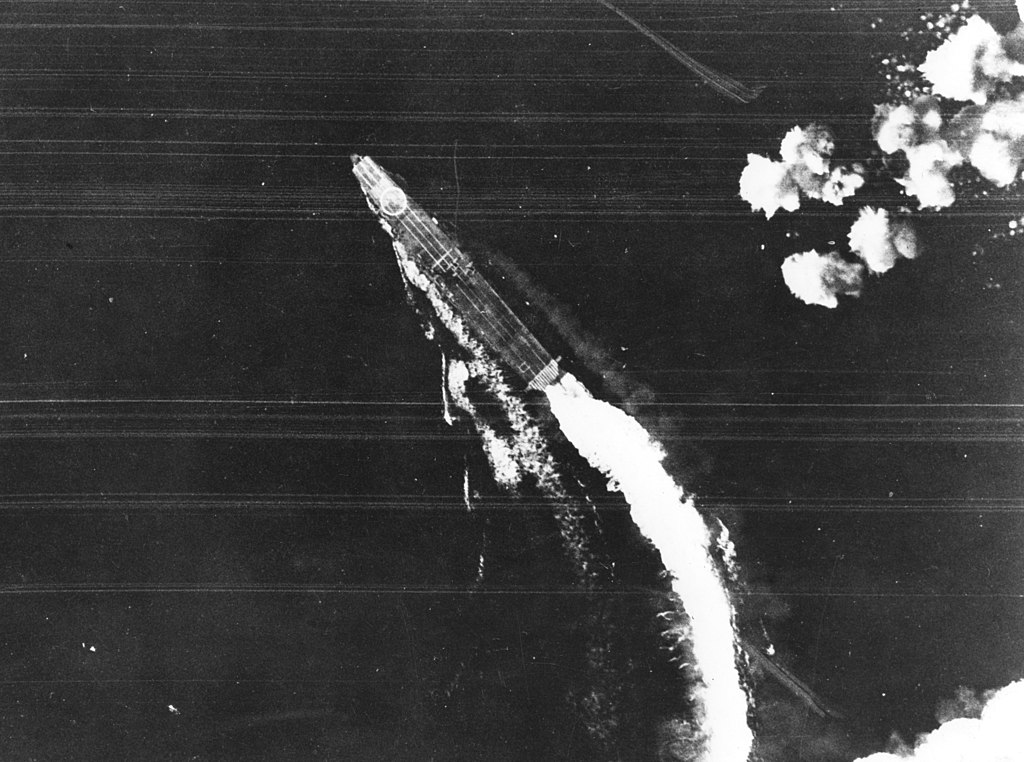

Hiryu’s manoeuvers to avoid bombs, 4 June 1942

The CAP was 11 strong, with Hiryu’s three Zeros and at 07:05, six? Five minutes later, six U.S. Navy Grumman TBF Avengers and four USAAC Martin B-26 Marauders with torpedoes attacked. Hiryū was attacked by Avengers, but thanks to her great speed and relative agility, her captain was able to have her dodging every torpedo, for those which passed the CAP. With 30 CAP Zeros in the air, five Avengers were down as well as two B-26s. The Avengers in particular were claimed specifically by Hiryū’s Zeros.

At 07:15, Nagumo made the fateful decision to reamed onboard Kaga and Akagi his B5Ns with bombs for another strike on Midway, but he reversed the order at 07:40 when he received a scout plane report of the US carrier fleet. Meanwhile, two Hiryū’s CAP Zeros landed to resupply. At 07:55, another strike from Midway (16 USMC Douglas SBD Dauntless from VMSB-241, Major Lofton R. Henderson) arrived. Hiryū’s CAP zeros went the only ones in the air at that time, out of only nine in the air total. Six Dauntless were shot down while trying a desperate glide bombing attack, but a tail gunner of one shot down one of Hiryū’s Zeros. Meanwhile, 12 USAAC B-17s arrive dover the scene at 20,000 feet (6,100 m) and dropped theur payload, but due to the altitude, the Japanese just have the whole fleet manoeuvering out of the way, and the bombers missed.

Hiryū soon launched three Zeros for the CAP at 08:25 which defeated anoother strike from Midway, 11 Vought SB2U Vindicator dive bombers (VMSB-241) concentrating on IJN Haruna at 08:30. Three were shot down and they all missed. At 08:20 Nagumo was confirmed the presence of the American carrier forces northeast, and the Midway strike force came back at 09:00, landing in turn for ten minutes and quickly struck below, the crews preparing a strike on the carriers, rearming with torpedoes. At 09:18, the first carrier strike was spotted, 15 Douglas TBD Devastator from VT-8 (Lt. Com. J.C. Waldron, USS Hornet) concentrating on IJN Soryū, but shot down, while the carrier dodged the torpedoes.

It was just the beginning. 14 Devastators from VT-6, USS from Enterprise (Eugene E. Lindsey) tried to sandwich Kaga, atttacking from both sides, but again, they were shot down by the CAP, reinforced by four Zeros from Hiryū at 09:37. All but four splashed. Kaga dodged all torpedoes while Hiryū launched three more Zeros at 10:13 just as VT-3 (USS Yorktown) was spotted. She lost Two to escorting Wildcats. VT-3 were concentrated on Hiryū, just as Dauntless dive bombers arrived over the scene. At circa 10:20, they were through almost unopposed and hit Kaga, Akagi and Soryu in quick succession. With budy crews in the hangar preparing the strike, gasoline and ammuntion aplenty, this was instant inferno. Amazingly, confusion in orders had some dive bombers attacking the same target, and IJN Hiryū was left unscaved.

Midway’s survivor was all thtat was left to launch the counterattack. aunched 18 D3As escorted by six Zeros flew off as planned, heading for the US carriers at 10:54. Underway, Zeros spotted USS Enterprise’s SBD Dauntlesses, but failed to shoot down any, while loosing two Zeros by rear gunners, a thord, damaged, later ditching near a destroyer. The Carrier’s radars detected the incoming wave and directed their CAP at 11:52 (20 Wildcats), which shot down the three Zeros left, and all but seven D3As, which made through. Two more were shot down by AA, leaving five which attacked. Two near-missed, but there were three direct hits. So this was IJN Hiryu’s that claimed USS Yorktown, the only serious US loss for this epic and crucial battle.

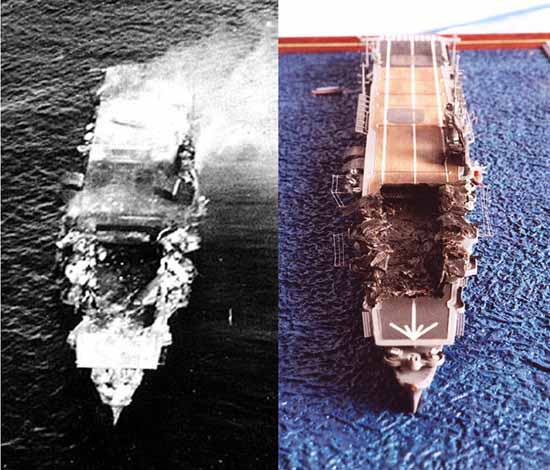

Hiryu adrift and burning, 5 June.

As cale model reconstructing the damage.

Admiral Yamaguchi now persuaded Yorktown was done for, launched a second wave of ten B5Ns, plus some from Akagi landed earlier on Hiryu, escorted by six Zeros (two from Kaga) at 13:30. They were searching to attack the separate carrier spotted but found USS Yorktown still far from finished, with all fires extinguished by 14:00, at 19 knots. At 14:30 when the strike approached, with six Wildcats nearby. Four were sent intercepting them, the two others watching over ten Wildcats fueling on deck and preparing to take off in turn. At 14:38 one B5N splashed, by two Wildcats were shot down Zeros, with two shot down later, and one more wildcat. Four more B5Ns splashed later, some by AA, but those which went through the meagre CAP scored hits on USS Yorktown: They damaged three boiler, knocking out electrical power onboard so she was soon dead in the water, listing to 23°, until order came to abandon ship. Only two Zeros and three B5Ns came back to Hiryū.

Yamaguchi asked Nagumo at 16:30 to launch a third strike at around 18:00, but Nagumo ordered the fleet to the north. The still unlocated USS Enterprise and Hornet meanwhile launched waves in between (26+16 Dauntlesses combined). Hiryū was left at this point with just four airworthy “Vals” and five “Kate” but still 19 “Zeke” plus 13 more for the collective CAP from other carriers. She had all of what’s left of the Kido Butai’s two divisions.

At 16:45, Enterprise’s Dauntlesses were her first and took altitude before diving in turn. At 16:56, Nagumo ordered a course change to 120° to recover his reconnaissance floatplanes, so the ship dodged the first bombs, not even spotting the SBDs before 17:01. The CAP intercepted and shot down two in their dives, another aborting. They were soon joined by the remainder of SBDs from Yorktown. Hiryū coid not dodge all and took four 1,000-pound (450 kg) bomb hits: Three on forward, one directly through the forward elevator.

Explosions rocked the ship and put her ablaze as the entire hangar deck became a furnace fed by ammunitions and aviation gasoline. The forward half of the flight deck in fact collapsed into the hangar after the explosion, the elevator was split i two, one part projected into the island. The apparent damage was so severe the remaining SBDs considered she was done for, and concentrated instead on her escort, but without effect. They started to retire, when at 17:42, two groups of B-17s arrived above the crippled aircraft carrier, and bombed her without hits. Though, one B17 plunged to strafed her flight deck.

Hiryū’s propulsion still was operational to this point, so she was able to steam fast. At 21:23 however, ruptured fuel lines had the fire spread below and her engines stopped. At 23:58, there was even a major explosion, probably caused by a cooking off ammunition depot, and order was given to abandon ship after three more hours of fire fighting. It was 03:15 when survivors were taken off by the escorting destroyers IJN Kazagumo and Makigumo. Captain Yamaguchi and officer Kaku decided to remain on board. At 05:10 the aicraft carrier was scuttled, torpedoed by IJN Makigumo and sunk with the two officers onboard. However at 07:00, Hōshō’s Yokosuka B4Y spotted Hiryū still afloat. They even could also see crewmen still on the deck.

They eventually took a boat and abandoned ship at 09:00, 39 in all fled in a cutter. Sehe eventually sank around 09:12 still with 389 men onboard, trapped, drawned or burned to death. These survivors drifted for 14 days before being spotted by a PBY Catalina and later rescued by the seaplane tender USS Ballard, becoming POWs. Five died later from wounds and exposure.

Reconstructed drawing, last moments of Admiral Yamaguchi.

All in all, the loss of Hiryū, the last of the two divisions making the bulk of the first air fleet greatly comprising the IJN’s strenght in the Pacific. Not only it was a strategic defeat as it failed to achieve its two objectives, taking Midway and destroying the remaining US carriers, but it severely hampered its capabilities to resist the next operations of thz USN in the south Pacific. By loosing these four carriers and these precious veterans, highly skilled air crews, the IJN also lost definitely its edge and would never recuperate. Hiryū’s design was considered for mass production, which became the planned program of 16 ships of the Unryū class from which only three were ever commissioned late in the war.

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign