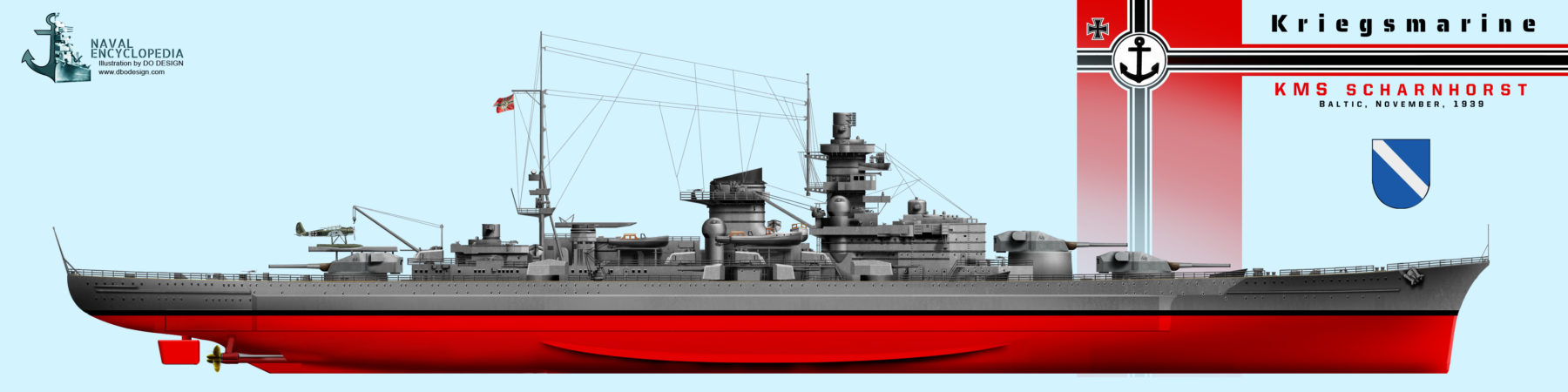

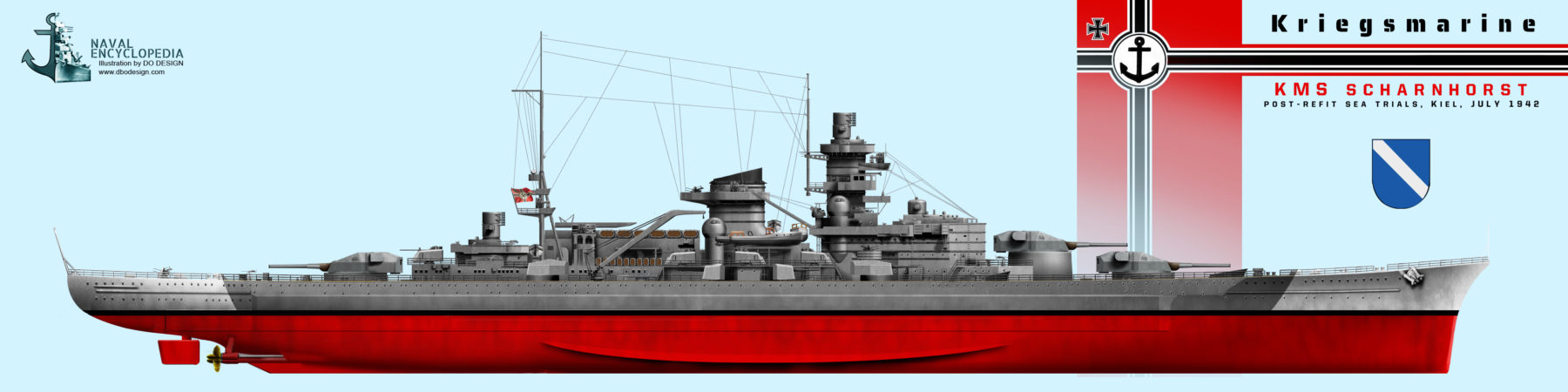

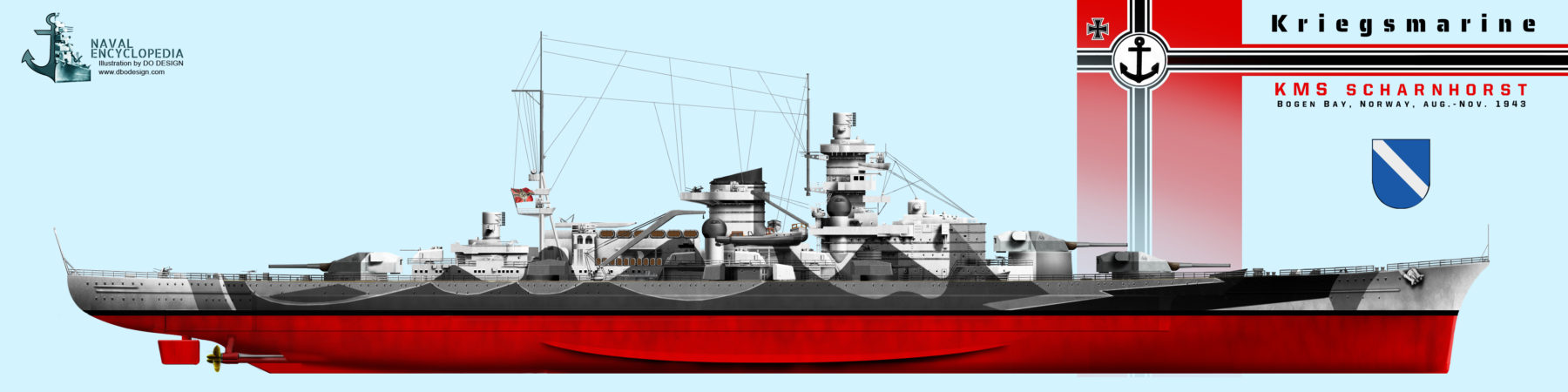

The Kriegsmarine “terrible twins”: The Scharnhost and Gneisenau were the first Kriegsmarine battleships, completed shortly before the start of WW2. They were fast battleships, with an true emphasis on speed over protection. The second issue was the lack of a suitable artillery, as the 2,8 cm used since the Deutchsland class were quite light, although long range and fast-firing. The optional 3.8 cm also developed for the Bismarck however were never installed. In any rate, the Scharnhorst class were transitional schlachtshiffe (“Battleships”), the first true ones being the Bismarck class. Their main asset was their speed, superior to any other capital ship of the time, only matched by battlecruisers such as HMS Hood (31 knots) or the Dunkerque class. This was this high speed which perhaps more than the protection level made them assimilated to battlecruisers at that time. During WW2, KMS Scharnhost and Gneisenau used this high speed in many occasions to their advantage, mostly against merchant traffic, but their biggest success was their escape from Brest through the channel, before joining Norway. For the duration of the war, they were used indeed as merchant raiders, due to their light artillery and protection, unsuitable for battle lines. They were also the only capital ships to sink an aircraft carrier in European waters (hms Glorious), and after their inconclusive duel against the battlecruiser HMS Renown also during the campaign of Norway, Scharnhorst was sunk in another famous duel at the battle of the North Cape in 1943, while her sister ship, badly damaged several times by air raids, was in repair in Kiel when the war ended.

The German first fast Battleships

Technically, the Scharnhorst pair not always have been called “fast battleships”. They were designed in answer to the French Dunkerque class which were slightly less armoured than battleships, so to be called at the time “battlecruisers” too. However, historians considered by simplifications this new generation was to be called “fast battleships” for simplification since their level of protection was still much superior to the WWI era battlecruisers.

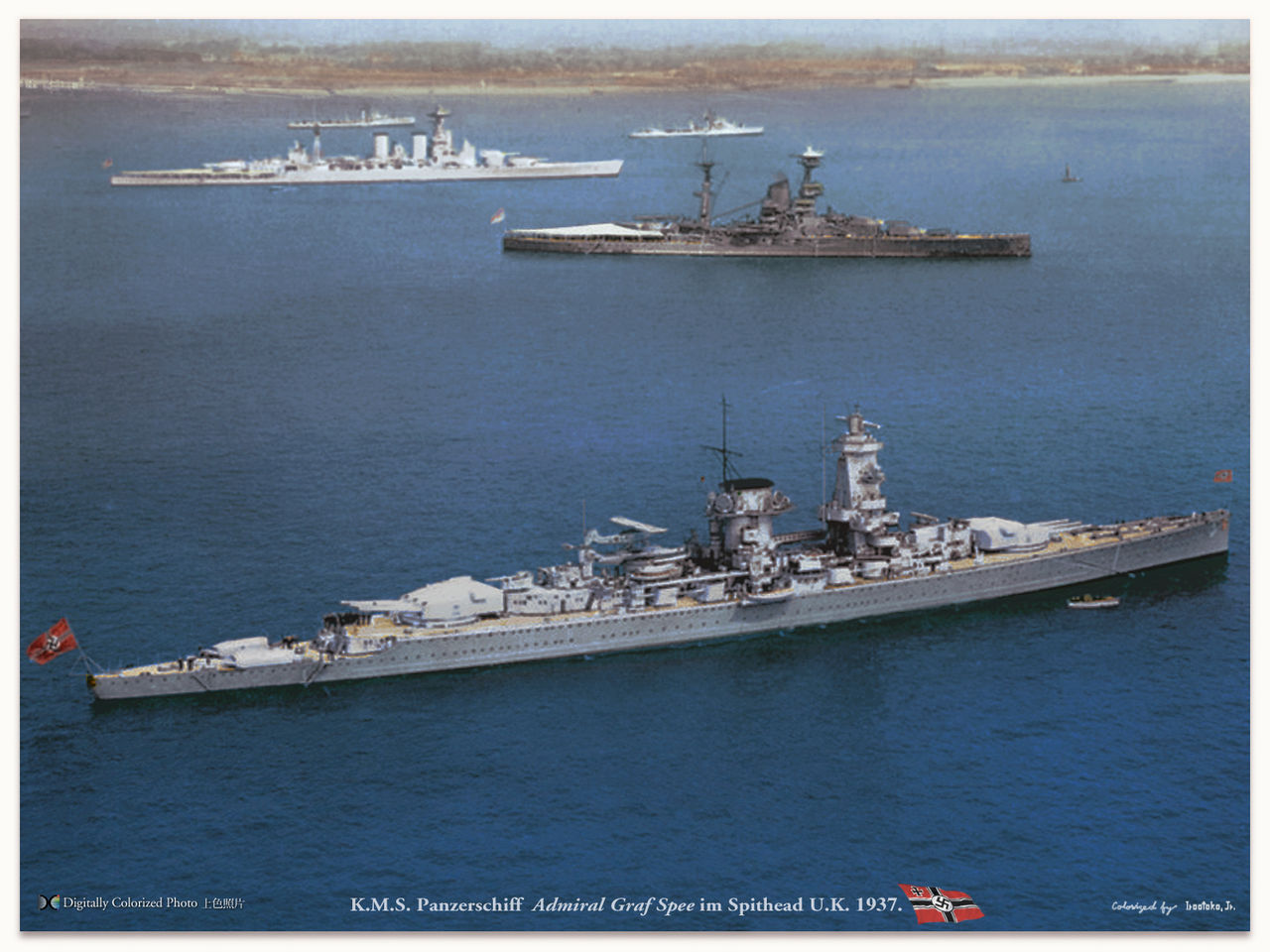

The Scharnhorst class was a class built prior to World War 2, and first true capital ships of the Kriegsmarine, especially compared to the previous Deutschland class “pocket battleships” which in reality were overgunned cruisers. KMS Scharnhorst and Gneisenau were named after two Prussian historical figures of the Napoleonic era which helped organize resistance and regain freedom.

KMS Scharnhorst being launched the first, the class is named after her although some sources talk of the Gneisenau class as she was the first to be laid down, but also commissioned. They were in effect the first ships in the ambitious German naval rearmament’s list, when Hitler decided to rip off the Treaty of Versailles. They were largely seen as transitional ships, armed with nine 28 cm (11 in) SK C/34 guns, in three triple turrets, although from the beginning it was planned to arm them with six 38 cm (15 in) SK C/34 twin turrets guns.

Both were commissioned by early 1939 and were planned as commerce raiders operating together in the early World War II as mutually supportive contrary to the Deutschland class which operated solo. Sorties into the Atlantic had mitigated success, Operation Weserübung off Norway showed they can be quite deadly together, as shown against HMS Renown and HMS Glorious in June 1940, with one of the longest-range naval gunfire hits in history. Their daylight channel dash in early 1942, was a propaganda coup dictated by their poor result against Atlantic merchant shipping compared to U-Boats and exposure to allied air raids while in Brest. It was more the result of poor coordination on the part of the British, but they had their revenge in Kiel while Scharnhorst joined Tirpitz in Norwegian fjords in order to raid the Murmansk convoys. At the battle of North Cape, she stood little chance against HMS Duke of York, but nevertheless this engagement taught both sides valuable lessons. The remainder of the two was never rearmed as planned, showing that allied bombers were quite efficient against large exposed targets such as battleships.

KMS Scharnhorst prewar – Bundesarchiv

Design development

The Treaty of Versailles restricted German naval shipbuilding to a mere 10,000 long tons and the reduced naval staff of the Reichsmarine discussed wildly in the 1920s about how to make a ship going around these limits. The result was the compromised “Panzerschiff” (aka ‘armored ships’) and not “Kreuzer” of the Deutschland class. They were completed in 1931, while prompting a response in France with the construction of the Dunkerque class. The Soviet Union projects also alarmed the Germans into studying large capital ships. The initial design project in 1928 was under the name of “Schlachshiff”, lit. “battleship” versus “panzerschiff” or “lilienschiff” which was the denomination of WW1 era battleships dreadnoughts an pre-dreadnoughts. The name change reflected an alignment on British parlance, but also a unification of the roles of battleships and battlecruisers.

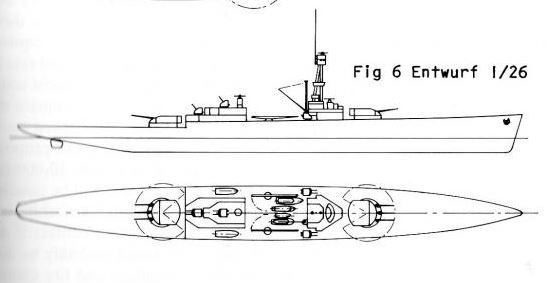

1928 schlachtshiff design:

Generally admitted design of the 1928 Type BC.

This was a 17,500 long tons (19,600 short tons) battlecruiser, armed with eight 30.5 cm (12 in) guns. The latter were arranged in four twin gun turrets and based on the design of the Ersatz Yorck-class battlecruisers left uncompleted. They were basically a massive improvement over the “pocket battleships”, as part of Admiral Zenker’s fleet building program; This design would have been “successor” of the panzerschiffe, and the ultimative raiders of their time with a top speed of 34 knots, and in addition to their main artillery, nine 5.9 secondary guns (149 mm) and of course larger, faster but sharing about the same overall armor scheme. Speed was indeed seen as a kind of active protection. 34 knots was faster than the British battlecruisers.

Specifications

Dimensions: Length (wl) 206.0 meters, Beam 25.0 meters, designed Draught 7.8 meters, moulded Depth 13.3 meters

Displacement: As designed 17,499 tons standard, 19,192-19,600 tons fully loaded, which includes 1,378 tons of fuel and 315 tons (1.6%) of boiler feed water.

Machinery: 4x shafts turbines, 12? oil-fired turbines, 160,000 SHP 34 knots. Bunkerage 3200 tonnes.

Armament: 8 x 305 mm/55 (4×2), 9 x 150 mm/55 (3×3), 4 x 88 mm AA

Armour: Main Belt: 100 mm down to 80 mm ends, main deck 25 mm, armored decks 30 and 20 mm, barbettes 250 mm as Main Turrets and CT, Torpedo Bulkhead 20 mm.

Admiral Zenker’s Naval Program

Hans Zenker was born in Bielitz (Bielsko-Biała, Poland) and entered the Imperial German Navy on 13 April 1889. He commanded SMS Lübeck in 1911, Cöln in 1912–13 and Von der Tann in 1916–17, at the Battle of Jutland. He joined the Admiralty Staff in 1917, appointed to the North Sea area command in 1918 and became Inspekteur der Marineartillerie from 1920 to 1923, and Chef der Marineleitung (Naval Command) until 1928, planning the the rebuilding of the German fleet.

Hans Zenker was born in Bielitz (Bielsko-Biała, Poland) and entered the Imperial German Navy on 13 April 1889. He commanded SMS Lübeck in 1911, Cöln in 1912–13 and Von der Tann in 1916–17, at the Battle of Jutland. He joined the Admiralty Staff in 1917, appointed to the North Sea area command in 1918 and became Inspekteur der Marineartillerie from 1920 to 1923, and Chef der Marineleitung (Naval Command) until 1928, planning the the rebuilding of the German fleet.

Vice-Admiral Hans Zenker prepared the navy’s building program around this assumption that Germany would have to prey first on maritime trade between France and Poland and to prevent French landings on the German coast. This fleet was also to wage a long-range commerce warfare against French interests. Basically the Kriegsmarine inherited this specifications. However the Reichstag opposed Zenker on his new ships pkans, and Erich Raeder was named instead, taking a much slower and prudent approach.

The Reichsmarine’s initial ships were were pre-dreadnoughts and same era cruisers and torpedo boats while personal was limited to 15,000 men as to ensure even this limited fleet could not be operational at all times. Two battleships were disarmed and the two others in reserve to allow crewing more modern ships. As it was authorized to replace cruisers 20 years old, an exception was accorded in 1922, with the RMS Emden, but only one over the six allowed eight cruisers could be in service, latter allowing for the “K” class. Total economic collapse delayed this program for two years, until the Nürnberg was authorized, and delayed again because of the 1929 crisis, to be finally laid down in 1934. By that time, for larger ships, the Versailles treaty applied, not Washington. For large ships, packing on a 10,000 tons design 11-inch (280mm) guns were authorized, but it was a daunting challenge. The allies hoped to constraint the fleet to ha Scandinavian-like coastal battleship collection.

Author’s photoshopping of a possible appearance of the Panzerschiff 1928

Zenker was the brainchild between the amazing Deutschland class, with thin protection bested by a very long range, another compensation for the lower caliber. As defined by Zenker, the class was to be aimed at commerce raiding and later Nazi German propaganda claimed they could outrun what she could not outfight (Battleship), and outfight those she cannot ourun (cruisers), which was of course false given the speed of battlecruisers. But on paper the idea was seductive. The German naval staff like the others worked on a “Washington Treaty Cruiser Killer”, with high speed and light armor. The same 10,000 tons/8-inch guns limitation applied and most navies chose to emphasis speed over protection. Battleships were limited to 35,000 tons/16-inch guns, plus an overall tonnage limit capping and some thought that filling this limit by two 17,500-ton warships given large-caliber guns would allow to built a larger fleet within the available tonnage, capped by the treaty to 17,500 tons indeed as minimum displacement for a ship carrying an artillery above 8 inches. Italy worked on such project in 1928, never realized, and the French also studied comparative designs.

Zenker hoped Germany would have re-entered world diplomacy in 1925 under the Locarno Pact, re-join the family of nations and thus, sign the Washington treaty or obtain an increase in the Versailles tonnage limit and increase of the main gun caliber to 12-inch, which was at the time advocated by all nations as a way to break the race and make the ships better fitted to peacetime.

Entwurf I/M26, alternative proposal for the Panzerschiffe

Zenker’s designs prepared by the naval staff by year:

1923:

-II/10 – Turbines coal/oil 25,000 shp 22 knots, 2×2 380 mm turrets, 2×2 150mm, 2x 88m, 2x50mm

-I/10 – Turbines oil 80,000 shp 32 knots, 4×2 210 mm turrets, 4x 88m, 8x50mm

1925:

-II/30 – Diesel oil 24,000 shp 21 knots, 3×2 305 mm turrets, 4x 105mm

-IV/30 – Diesel oil 24,000 shp 21 knots, 2×3 (all fore) 305 mm turrets, 2×2 150mm, 4x 105mm

-V/30 – Diesel oil 24,000 shp 21 knots, 2×3 (1 fore, 1 aft) 305 mm turrets, 6x 150mm 3x 88mm

-I/28 – Diesel oil 24,000 shp 21 knots, 2×3 (1 fore, 1 aft) 305 mm turrets, 2×2 150 mm, 6x 88mm

-II/28 – Diesel oil 24,000 shp 21 knots, 3×2 (2 offset aft) 305 mm turrets, 4x 150 mm, 4x 88mm

-VI/30 – Diesel oil 24,000 shp 21 knots, 2×2 (1 fore, 1 aft) 305 mm turrets, 2×2 150 mm, 4x 88mm

-VIII/30 – Diesel oil 24,000 shp 21 knots, 2×2 (2 fore) 305 mm turrets, 2×2 150 mm, 4x 88mm

-I/35 – Diesel oil 16,000 shp 19 knots, 1×3 (fore) 305 mm turrets, 6x 88mm

-VIII/30 – Diesel oil 36,000 shp 24 knots, 2×2 (fore & aft) 305 mm turrets, 6x 88mm

1926:

-I/M26 – Diesel oil 54,000 shp 28 knots, 2×3 (fore & aft) 280 mm turrets, 4×2 120 mm DP, 6x 37mm

-II/M26 – Diesel oil 54,000 shp 28 knots, 2×3 (fore & aft) 280 mm turrets, 4×2 120 mm DP, 6x 37mm

1927:

-Type A – Diesel oil ? shp 18 knots, 2×2 (fore & aft) 380 mm turrets

-Type B1 – Diesel oil ? shp 18 knots, 2×2 (fore & aft) 380 mm turrets

-Type B2 – Diesel oil ? shp 21 knots, 2×3 (fore & aft) 305 mm turrets

-Type C – Diesel oil ? shp 26 knots, 2×3 (fore & aft) 305 mm turrets

1928:

-Type BC – Diesel oil 160,000 shp 34 knots, 4×2 305 mm turrets, 3×3 150mm, 4×88 mm

Hans Zenker therefore ordered a 17,500 tonnes, 12-in armed, “Kreuzer Jäger” (or cruiser killer) with good range and a thin protection which could outrange cruisers. The twin turret was a wel known and trusted design, so no surprise to wait technically on this side. The Secondary guns of nine 5.9-inch was more original as it was fitted in the very same turrets in production for K-type cruisers. For closer range, they were fitted by two triple banks of torpedo tubes. The armor scheme was largely the same as the Deutschland studied at the same time, but the much greater speed (34 knots against 28) only could be obtained from a much larger hull with turbines and not diesels like Deutschland, curtailing its range. So it ws assumed they would be deployed in another way. If meeting a battleship, they stood little chance, only having hopes to out-run them. Against anything behind she could unleash enough firepower to deal with a convoy protected by cruisers. Those of the time of Zenker were French, and of the generation of “tin-clad” cruisers, so easy preys. But events did not met the optimistic hopes of Zenker, and German diplomats seems to never had even asked to raise these limitations either, having other priorities at the time.

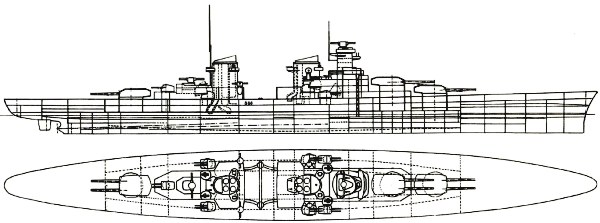

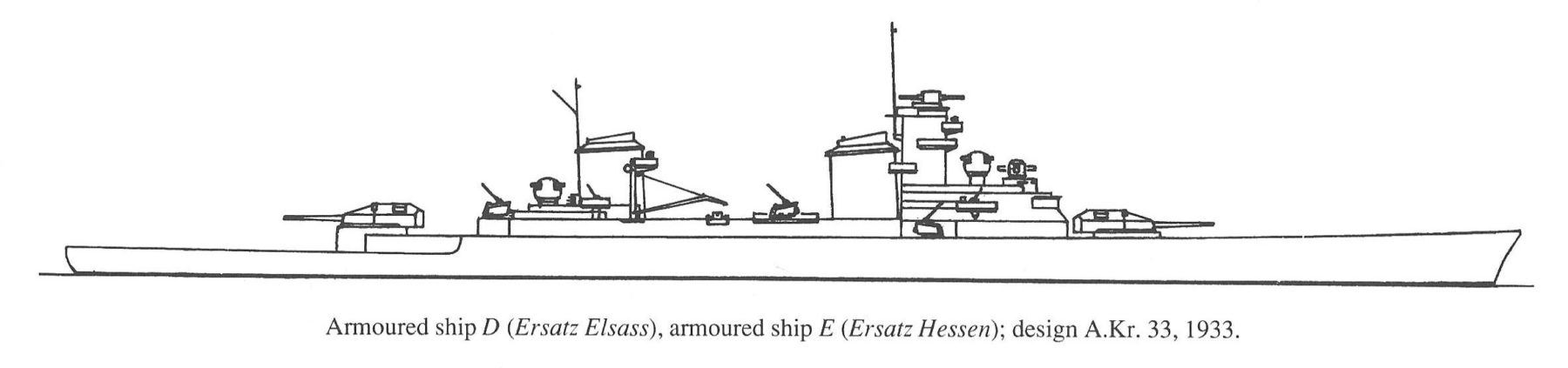

1933 D-class design:

The follow-on to the Deutschland-class cruisers named “Panzerschiffe” were designed under Raeder, the new Chief of the Navy. It was linked to 1933, the year the Nazi Party came to power in Germany. This ended the dispute between those who wanted a large-scale naval rearmament program, Hitler himself defining priorities and limit construction to a counter French naval expansion. Authorization for two additional panzerschiffe were stipulated to displace 19,000 long tons (19,000 t) with the same primary battery, but Erich Raeder advocated increasing the armor protection. He also lobbied for a third triple turret while the ship was to stay within the 19,000 ton limit fixed by Hitler. Two projects were drawn under the contract names D and E, or “Ersatz Elsass” and “Ersatz Hessen” respectively, knowing they would replace the disarmed old pre-dreadnoughts SMS Elsass and SMS Hessen. Design D was awarded on 25 January 1934 to the Kriegsmarinewerft in Wilhelmshaven. He keel was laid on 14 February while at the same time the Kriegsmarine decided to alter the design as more was known about the French Dunkerque-class. Hitler agreed the displacement raised to 26,000 long tons (26,000 t), AND the third 28 cm triple-turret. Construction was halted on 5 July, while E was never laid down. Contracts were canceled and the whole program evolved into Scharnhorst class.

Project D Characteristics

These were 230 meters (750 ft) long by 25.5 m (84 ft) in width, and a draft of 8.5 m (28 ft) for a final displacement of 20,000 long tons (20,000 t). “D” would have been given the accommodations of a fleet flagship, and bot were turbine-powered; Total output as designed was to be 125,000 shaft horsepower (93,000 kW) for 29 knots at full speed. The main armament was exactly the same as for the Deutschand class, but with one extra turrets and its three 28 cm (11 in)/52 C/28 quick-firing guns. The staff discussed the possibility of having two quadruple turrets, for eight guns, but this caused major redesign concerns. The 11.1 in guns fired both AP and HE shells weighting 300 kg (661.4 lb), using a 36.0 kg (79.4 lb) fore charge and silk bag plus a 71.0 kg (156.6 lb) main charge in a brass case. 910 mps (2,986 fps) at 40 degrees, gave an excellent range of 36,475 m (39,890 yards) for 2.5 rpm and 900 shells in store, total. Her secondary battery comprised eight 15 cm (5.9 in)/55 SK C/28 quick-firing guns ordered by the time construction was canceled, so they ended on the Scharnhorst class, in a mix of single and dual turrets.

The anti-aircraft battery was consistent for the time, taking aviation very seriously: Eight 10.5 cm (4.1 in) SK C/33 guns in twin Dopp LC/31 type mounts originally designed for the old 8.8 cm (3.5 in) SK C/31 guns. They were triaxially stabilized for a 80° elevation 12,500 m (41,000 ft) ceiling, HE and HE incendiary rounds, illumination shells, also a number of 37 mm guns (unknown figure) were to be provided as well as 53.3 cm (21.0 in) torpedo tubes, probably two quadruple banks mounted alongside the deck. Armour protection was made in Krupp hardened steel plates, with a 35 mm (1.4 in) thick deck, 70 mm (2.8 in) main armored deck forward, 80 mm (3.1 in) amidships down to 70 mm at the stern, a main armored belt 220 mm (8.7 in) thick, a conning tower with 300 mm (12 in) walls and the bulkheads forming the citadel of 50 mm (2.0 in) thick, probably also with ASW longitudinal bulkheads. Little is known about their internal compartimentation below the waterline, but giving the fact it was based on the Deutschland, with a longer hull, we can assume well separated turbines and boilers rooms.

KMS Hessen if completed in 1936. Credits Haratio Fales, CC

In Brief:

Displacement: 20,000t, Length: 230m, Breadth: 25.5m, Speed: 29kts

Armor: Belt 220mm, Citadel: 50mm, CT 300mm, Decks 35-80 mm, Bulkheads 50mm

Armament: 2×4 28cm/52 QF, 8×2 (4 x 15cm/55 QF, 4x 10.5cm/65 DP), AA, 2×4 TT.

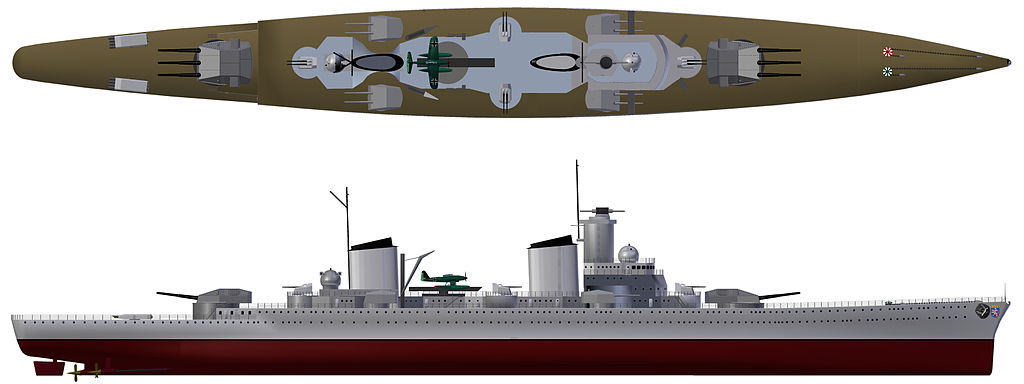

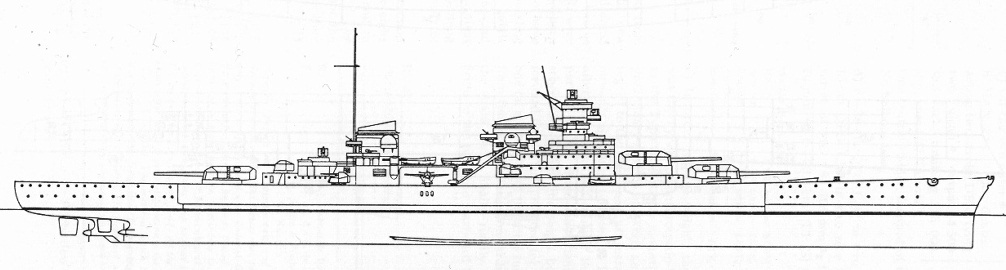

1937 P-class design:

As part of Plan Z, these were another alternative design, an attempt to replace the Deutschland class for commerce raiding. This class as planned was to comprise twelve heavy cruisers, not capital ships, in replacement for the Deutschland-class cruisers. Design started in 1937 and went on until 1939 with twenty designs in between. Nine were considered, three selected.

1-six 283 mm, single triple turret forward, one more aft. Two 150mm twin secondary turrets fore of the aft main and front main turret. It was beamier than the other two and mounted two seaplanes on its fantail.

2-Second design: Six 28 cm (11 in), in two triple turrets, called “Panzerschiff”, with the names P1–P12, improved versions of the D-class cruisers cancelled in 1934. They were assigned to shipyards, but construction never started as the O-class battlecruisers were choses instead. Note: These will be seen in a dedicated post in the future and more in detail in the WW2 German

Even with the completion of the two Scharnhorst-class and start of two Bismarck-class, the German Navy wanted to past its numerical inferiority in 1937 by creating more of an improved Deutschland-class design, and after more than twenty designs considered for these specifications, only one last was chosen, designated as cruiser “P” (For “Panzerschiffe”). Z-Plan indicated twelve P-class built FY1940, designed as “kreuzerjäger” or “cruiser hunters/killers” to take on heavy cruisers and still outrun fast battleships.

Many design problems delayed the finalized blueprints, the main issue revolving around armor. The top speed of 34 knots (63 km/h; 39 mph) on a 217 m (712 ft) to 229.5 m (753 ft) hull meant that the beam needed to be kept at 25 m (82 ft) while if diesel engines were to be installed installed this would have been raised by 2 m (6.6 ft) meaning that designers needed to make the hull longer in order to keep its hydrodynamic efficiency. This meant greater lenghts of armour plates that further complicated the protection arrangements. What really killed the design was this impossibility of marrying diesels with a 20,000-tonne ship.

At some point, the design changed completely to a capital ship intended to the dual role of classic battle ship and still preying on cruisers. The result was a class of battlecruisers with an armament shifting from 283 mm (11.1 in)/55 caliber guns to 380 mm (15 in)/47. It was eventually concluded that smaller gun were far less effective in combat anyway, and to restrict the initial plan of twelve ships to just four in order to not overtax shipyards. This was also based on foreign capital ship gunnery standards and time from design to service. Last argument came in 1939, when Adolf Hitler denounced the 1935 Anglo-German Naval Agreement and declared the 38 cm caliber standard for any German capital ship. This eventually evolved into the O-class battlecruisers; never built.

P class drawing – SRC

HD version of the design upgraded to the 38 cm caliber turrets

An overview is coming soon.

Complete specifications (1st version)

Displacement: 22,145 t (21,795 long tons) (standard), 25,689 t (25,283 long tons) (full load)

Length: 230 oa/223 m wl, Beam 26 m, Draft 7.20 m

Installed power: 4 shafts, 12 MAN 9-cylinder diesels 165,000 PS (121,000 kW; 163,000 shp) 33 knots (61 km/h)

Range: 25,000 nm (46,000 km; 29,000 mi)/13 knots or 15,000 /19 knots

Armament: 2×3 28 cm (11 in) 8 × 15 cm (5.9 in), 4 × 3.7 cm (1.5 in) AA, 6 × 53.3 cm TTs

Armor: Barbettes: 80 to 100 mm, Belt 40 to 120 mm, Deck 70 mm, Torpedo bulkhead 30 mm (1.2 in)

Misc.: 2 Aircraft and 2 steam catapults

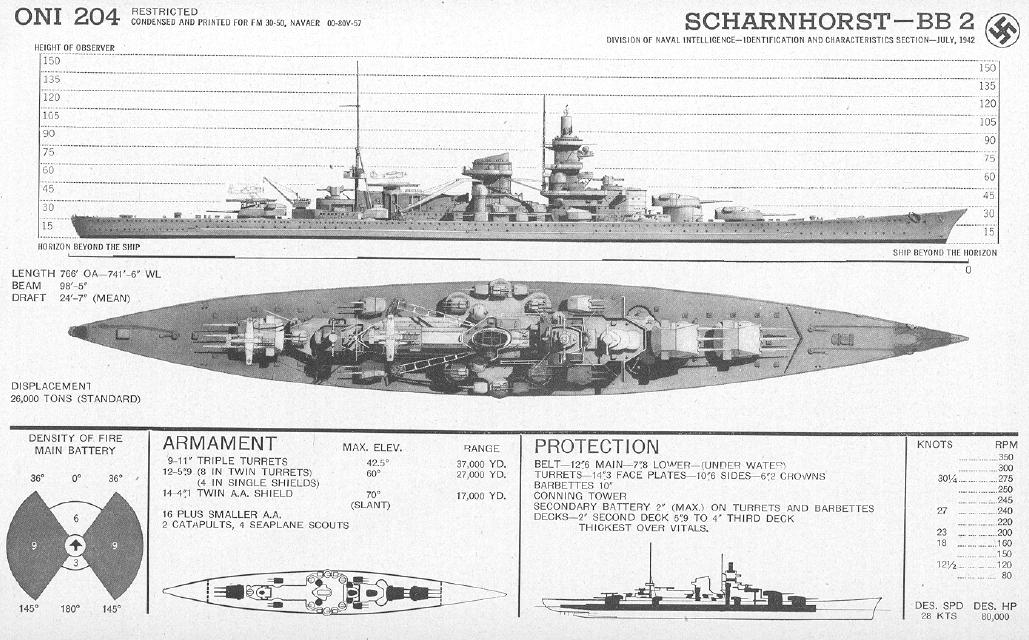

US Intelligence, identification plates

Arrival of Hitler and naval plan confirmation

In 1933, Adolf Hitler made clear to the naval staff since the beginning he has no intention to contest the Royal Navy’s hegemony (like he would repeat again and again before the battle of Britain, hoping favourable peace conditions). He was concerned chiefly, as Zenker, by a limited war with France over the question of Poland, and therefore the navy’s role was chiefly to protect German sea lanes as well as distrupting French ones. He authorized thefore two more ships of the Deutschland-class Panzerschiffe, with a 19,000 tons displacement and same same armament and speed, the extra tonnage saved being used for protection. This relatively modest ships were mostly not to antagonize too much the allies about the Treaty of Versailles but these planned commerce raiders were seen as a much greater threat for Great Britain than an alternative plan for 26,000-ton battlecruisers, armed with 28.3 cm (11.1 inch) guns.

Scharnhorst’s 280mm turrets

However, the design evolved as the French soon built two small Dunkerque-class battleships in the early 1930, which prompted the German navy to revise plans for a more powerful battlecruiser design. Erich Raeder was the head of the German Navy in 1933, and argued in favor of a scaled-up Panzerschiffe, with a main battery comprising a third triple turret. This position was backed by the Kriegsmarine, which put a nail in the 19,000-ton design coffin. Hitler eventually agreed on increased armor protection and internal subdivision, but no other modification to the design. By February 1934 however he eventually agreed on the third turret, which allowed design development to be resumed, one a displacement estimated to 26,000 long tons (29,000 short tons). To save time, the same 28.3 cm and turrets were kept. However, to secure these, and the following naval plan, Hitler signed in the 1935 Anglo-German Naval Agreement, recoignising a 3 to 1 superiority in capital ships but removed the limitations of the Treaty of Versailles for the Kriegsmarine. However Germany still was not signatory of the Washington treaty, but there was a gentleman’s agreement over their application. The new D-class design was definitively cancelled to make way for Scharnhorst and Gneisenau (see above). Provisional names, Elsass and Hessen, were reallocated and contracts awarded to Wilhelmshaven and Deutsche Werke in Kiel. Construction however was slowed sown by 14 months, as negociations were ongoing for a treaty with Britain. The staff used this respite to study numerous improvements and additions to the design.

Because the maximum caliber allowed by the Anglo-German Naval Agreement was raised to 40.6 cm (16 inch) for Germany, Hitler soon came back to the designs initially planned and ordered to setup-up to 38 cm (15 inch) instead of leap-frogging directly to the larger caliber. The 28.3 cm turrets however being available and new turrets taking years to develop, it was decided to stay with the previous planned caliber. Hitler also reminded the British were sensitive about main gun calibers increases for German capital ships, trigerring races Germany could ill-afford at that stage. He acquiesced to the 28.3 cm guns but with a provision for them to be up-gunned to 38 cm as soon as possible while the 38 cm turret which were studied landed on the the Bismarck-class (and were never fitted on the Scharnhost class).

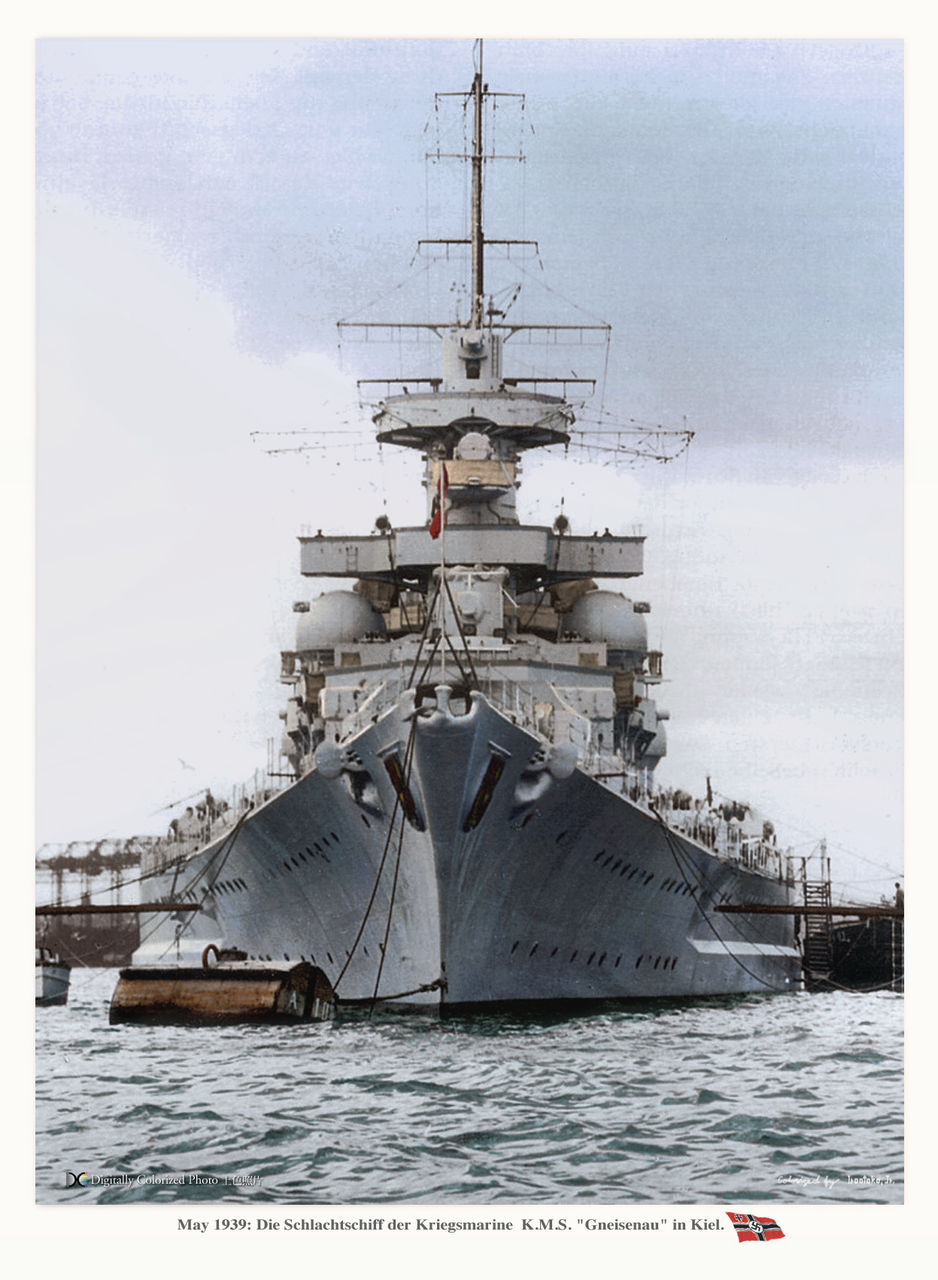

KMS Gneisenau’ bow at Kiel in 1939 – colorized by Irootoko Jr.

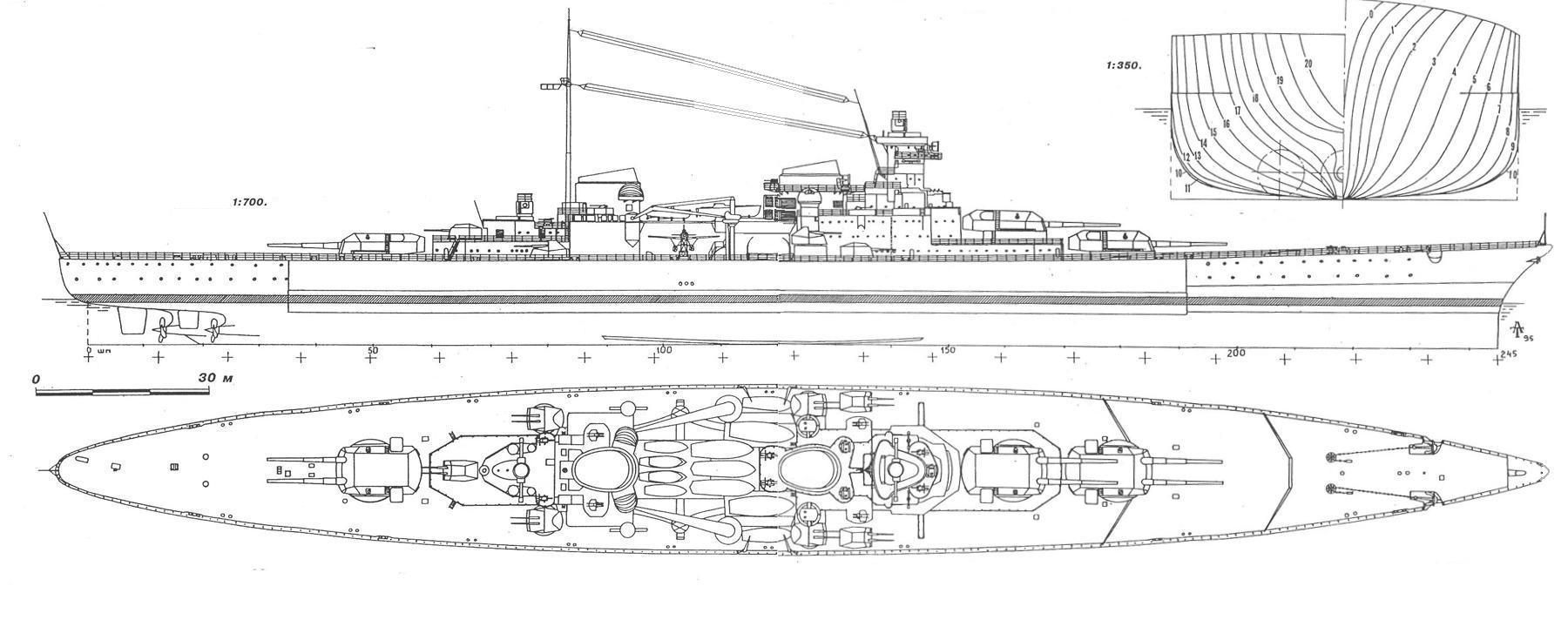

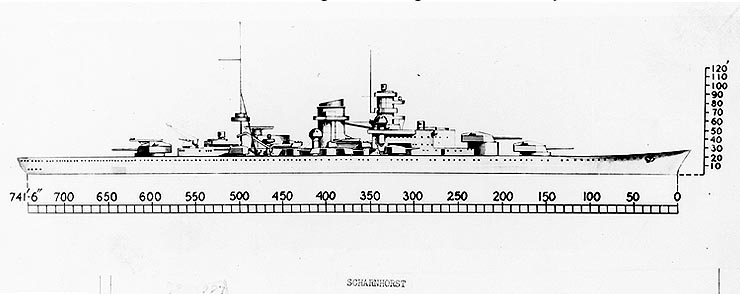

Scharnhorst class final design 1934

Design development was largely based on an extenson of the cancelled Project D, with the third turret. As completed, this design was accepted in 1935, and orders confirmed at the Kriegsarinewerft and Germaniawerft in May-June that year. The hull were stretched to reach 226 m (741 ft 6 in) at the waterline, 234.9 m (770 ft 8 in) long overall (For Scharnhorst) while Gneisenau was shorter at 229.8 m (753 ft 11 in) overall, but the same straight bow. Both hwere 30 m (98 ft 5 in) wide and with their final designed displacement of 35,540 t (34,980 long tons), draft was 9.1 m (29 ft 10 in). Standard displacement was 32,100 long tons (32,600 t) for a 8.3 m (27 ft 3 in) draft, up to 9.9 m at 38,100 long tons. Construction called for longitudinal steel frames and welded outer hull plates with 21 watertight compartments dividng the structure underwater and a double bottom for 80% of the lenght.

On trials, the straight bow and hull shape meant they were both poor seaboat, always “wet” and plowing in heavy weather in the north sea. To the point that water splashed went as far high as the bridge. TSoon both were taken in hands to rebuilt their straight stem with an “Atlantic bow” (clipper shaped and longer) in January (Scharnhorst) and August 1939 (Gneisenau). But ever after thiosn their low hull meant “A” could not fire straight over the deck and was curtailed by water splashes in heavy seas. For the same reason, their stern was also frequently “wet”. Both were fast as planned, but very slow when entering a turn: When the rudder was hard over they lost over 50% speed and heeled to more than 10° and as much as 13° hard rudder in trials. In port, they always required assistance from tugboats.

Their crew comprised 56 officers and 1,613 gratings on Scharnhorst, up to 60 officers and 1,780 enlisted men on Gneisenau, and in wartime and acting as squadron flagship, they carried 10 more officers and 61 more men. Their fleet of smaller watercraft differed in their locations, but both had two picket boats, two launches, two barges, two pinnaces, two cutters, two yawls, and two dinghies.

Propulsion

Diesel propulsion has been planned for a time, as they were perceived as replacement for the three Panzerschiffe, long range commerce raiders. But their role shifted to classic battleships and it was decided to give them a superheated steam propulsion, as for their size, and desired speed, they needed three times more output power that the Panzerschiffe. They had a triple propellers arrangement, so twice the power per shaft than the Panzerschiffe, while the option for four propellers was still 40,000 hp per shaft. This went far beyond diesel technology at the time, thus this naturally imposed steam turbines. One set was ordered in UK, due to the technological gap lost since the great war and differed in both vessels:

-Scharnhorst had three Brown, Boveri, & Co geared steam turbines, Gneisenau three Germania geared turbines. Their three 3-blade propellers were 4.8 m (15 ft 9 in) in diameter. Thiese turbines were fed by the steam produced by 12 Wagner ultra-high-pressure oil-fired boilers. Their working pressure was around 58 standard atmospheres (5,900 kPa) at temperatures of 450 °C (842 °F). In total these powerplant were rated at 160,000 metric horsepower (157,811 shp; 117,680 kW) while the shafts spinned at 265 revolutions per minute (rpm) max. On trials the ships reached an output of 165,930 PS (163,660 ihp; 122,041 kW) at 280 rpm.

KMS Scharnhorst in trials, 1939 – colorized by Irootoko Jr.

They could also reverse and in tht cas, worked on 57,000 PS (56,220 ihp; 41,923 kW). Top speed as designed was 31 knots (57 km/h; 36 mph) and on trials they exceeded these figures, Scharnhorst reaching 31.5 kn (58.3 km/h; 36.2 mph) and Gneisenau 31.3 knots (58.0 km/h; 36.0 mph). For endurance, both carried 2,800 metric tons (2,800 long tons; 3,100 short tons) of fuel oil. The latter occupied the allocated tanks, but there were plenty of additional storage areas usable in wartime, notably the hull spaces between the belt and torpedo bulkhead as filler against torpedo hits. This could rise the total capacity to 5,080 metric tons (5,000 long tons; 5,600 short tons). With this, both were on paper able to reach a radius of 8,100 nautical miles (15,000 km; 9,300 mi) at 19 knots (35 km/h; 22 mph). However in normal conditions, Scharnhorst reached 7,100 nmi (13,100 km; 8,200 mi) and Gneisenau 6,200 nmi (11,500 km; 7,100 mi) on trials at this speed. This forbade their use as long range raiders like the Deutschland class, but sweeps in the North Atlantic.

Electrical power came from five electric units at different points. Each of these small powerplant comprised four diesel generators and eight turbo-generators each. These diesel generators provided 150 kilowatts, 300 together or 600 kW. The eight turbo-generators varied in capacity, six of these models generating 460 kW each and two 230 kW for a grand total of 4,120 kW at 220 volts for all inboard systems.

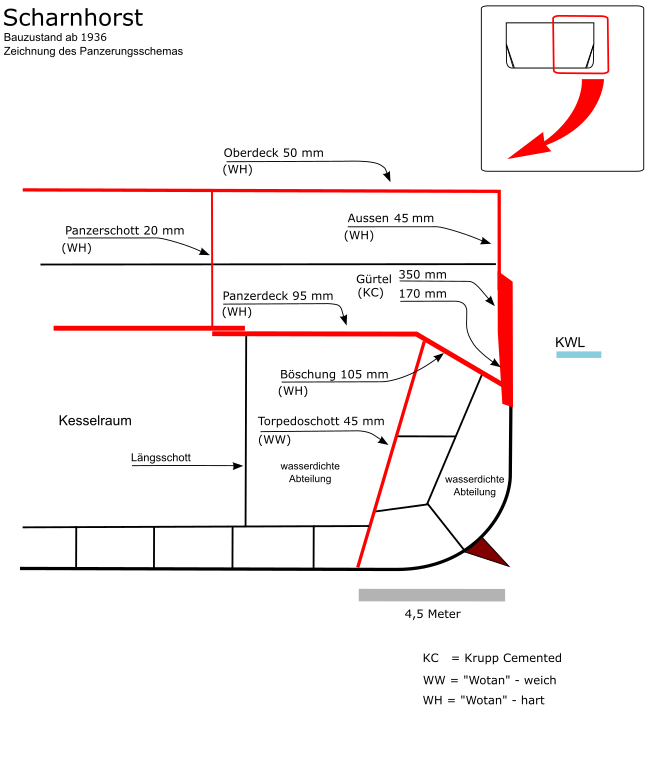

Protection

The Scharnhorst class battleships had hardened Krupp armor all around and critical areas with “Wotan Hart” steel. Slopes of the turtle deck artificially increased armor protection in the critical areas of the ship against horizontal fire. Their vitals were well armored against any caliber at angles impacting the main belt-sloping deck area, but at very long range plunging fire, deck armor was weak. The belt central section was 350+170 mm in Krupp Cemented steel and immune to 2,240 lb (1,020 kg) 16 in (406 mm) shells fired over 11,000 m (12,000 yd). The artillery turrets were protected by KC steel. The ASW protection as designed was to withstood a 250 kg (550 lb) explosive warhead. Full-scale underwater explosion tests were done with sections of armor cut from the old SMS Preussen, revealing that welded steel resisted better than riveted plates. On the Schanrhorst class, the torpedo bulkhead was made of Wotan Weich (Wotan, soft) steel, behind the armored belt. The latter was riveted because plate joints incorrectly welded would not withstand an impact.

Here is the detail:

Armored Deck: Upper: 50 mm (2.0 in). Main armor deck: 20 mm aft and bow (0.79 in) to 50 mm central, ammo magazines/machinery

“Turtle deck”: Sloped plates, 105 mm (4.1 in) on both longitudinal side, connected to the lower edge of the main belt

Armored belt: 350 mm (14 in) central section, 150 mm (5.9 in) and down to zero at the bow, 200 mm (7.9 in) aft to zero at the stern.

Belt Central portion backing: 170 mm (6.7 in) shielding.

Conning towers: Forward 350 mm walls, 200 mm roof. Aft CT: 100 mm (3.9 in) walls, 50 mm roof.

Main gun turrets: 360 mm (14 in) faces, 200 mm sides, 150 mm roofs.

Barbettes: 350 mm tapered down to 200 mm below, shielded by the turrets above.

Secondary 15 cm turrets: 140 mm (5.5 in) faces, 60 mm (2.4 in) sides, 50 mm roof.

10.5 cm gun mounts: 20 mm (0.79 in) gun shields.

Underwater protection: Outer layer 12–66 mm (.47–2.6 in), void, fuel bunker 8 mm (0.31 in) outer wall and longitudinal stiffeners, transverse bulkheads.

The outer layer located under the main armored belt detonated the torpedo warhead and behind was located a large void to allow gases to expand and dissipate. Beyond it was located the fuel bunkers just 8 mm (0.31 in) thick on the outer section (exposed) to absorb the remaining explosive force. The latter was stiffened by longitudinal frames and transverse bulkheads as well.

This was an extremely strong amidships, but clearly weaker aft and forward of the citadel. There, it still could deal with a 200 kg (440 lb) warhead, roughly a 457 mm aerial torpedo. The arrangement of the torpedo bulkhead, connected to the lower portion of the sloped deck at 10° had riveted angled bars. However these bars were not designed to take too much stress, already from normal bending forces when manoeuvring hard rudder. If a torpedo warhead stoke when turning, these already overloaded bars would fail. The beam was limited, therefore decreased on both ends of the citadel near the turrets in width, notably the critical battery turrets, close to the magazines and barbettes. More beam allowed for more armor, stability and absorption of impacts underwater. That’s why the following Bismarck class had a beam of 36 m instead, just conceding a single knot in top speed.

Armament

Main:

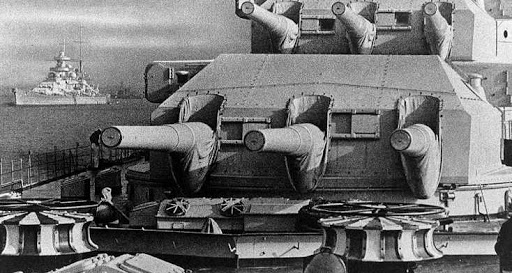

28 cm turrets of KMS Scharnhorst, with Gneisenau in the background – src navweaps.com

The Scharnhorst-class battleships carried nine 28.3 cm (11.1 inch) SK C/34 54.5 (34 caliber) quick-firing guns located in three triple turrets, two forward and one aft. These guns were not identical to the 28.3 cm SK C/28 mounted on the Deutschland-class Panzerschiffe as their barrel was reinforced and much longer. This 28.3 cm caliber looks weak, but Kriegsmarine’s officers still preferred it to heavier, but slower rated guns. The higher rate of fire was indeed 3.5 rounds per minute and the crews made competitions for faster loading, despite the level of automation compared to the previous guns.

Conception of the 28 cm (11″) SK C/34

They had a high muzzle velocity, giving its light-weight projectiles very long range and good penetration power but poor performance against deck armor. Gneisenau was badly damaged during a bombing raid and her guns were reused in a coastal fortification, turret Caesar, still remains a museum exhibit at Austrat (Oerlandat) near Trondheim in Norway. Turret Bruno was used at Fledt, near Bergen and individual guns (Turret Anton) used in Denmark and the Netherlands.

Inroduced into service in 1938, they weighted, including the breech 111,739.6 lbs (53,250 kg) and Worked at a 20.3 tons/in2 (3,200 kg/cm2) pressure, with an approximate Barrel Life of 300 rounds. It was Constructed of A tube with a loose liner, a two-part shrunk-on jacket and a breech end piece screwed shut to the jacket. The breech block supporting piece was screwed into the breech end-piece and its used horizontal sliding.

The overall lenght was 607 in (154.415 m) for a 571.1 in (14.505 m) long barrel and a rifling 461.6 in (11.725 m) long, (80) grooves 0.128 in deep x 0.265 in (3.25 mm x 6.72 mm) and lands 0.173 in (4.4 mm), increased twist RH 1 in 50 to 1 in 35. Its chamber Volume was 10,984 in3 (180 dm3).

The 2.8 cm had a rate Of Fire of 3.5 rounds per minute, and fired the APC L/4,4: 727.5 lbs. (330 kg), HE L/4,4 base fuze: 694.4 lbs. (315 kg), HE L/4,4 nose fuze 3: 694.4 lbs. (315 kg) and HE L/4,4 nose fuze AA 4: about 685.0 lbs. (311 kg). They had two propellant charges, the fore one 93.7 lbs. (42.5 kg) RPC/38 (1040 x 15/4.0) and Main charge 168.6 lbs. (76.5 kg) RPC/38 (1195 x 15/4.9). When loaded the w/RPC/32 cartridge weighted 262.3 lbs. (119 kg). With the APC muzzle velocity was 2,920 fps (890 mps)

These the same kind of projectiles as did for the Bismarck and Hipper, notably Psgr.m.K. L/4,4 AP rounds scaled to 28.3 cm size. The 28 cm SAP round was also a copy of the 38 cm round but without the light AP cap. One clue about this design was German intelligence believing French battleships used KC armor for their turret roofs. The 28 cm SAP design was ather weak small to penetrate vertical armor. Netherlands Navy planned these guns for their “Design 1047” (Gelderland class) Battlecruisers.

Turrets: Drh LC/34 turrets named from the bow “Anton”, “Bruno” and “Cäsar”, electrically traversed with hydraulic elevation/depression, a mass of 750 tons, an internal barbette diameter of 10.2 m, a traversing speed of 7.2° ps and depression/elevation of −8° to 40°, -9° for the superimposed “B” turret with a 40,930 m (44,760 yards) range.

Secondary Artillery

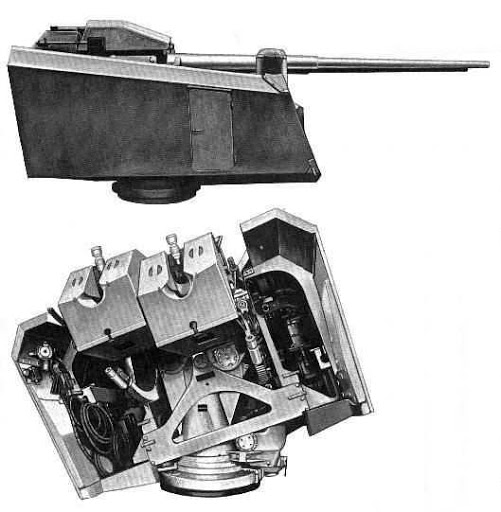

150 mm twin turret as preserved today in a coastal battery

-Twelve 15 cm SK C/28 L/55 quick-firing guns.

These were mounted in two ways, due to the lack of space: Eight guns in four Drh L. C/34 twin turrets and four in single MPL/35 pedestal mounts. The former were placed on the broadside, one pair abft the bridge superstructure, with a cylindrical recess to allow the turret a 180°, the second pair abaft the aft superstructure. The single masked mounts were located along the amidship section, on either side of the funnel, with a platform in between supporting one of the eight twin AA mount.

The turrets and pedestal mounts enabled a depression/elevation of −10°/40° down to 35° for the single mounts. They fired a 45.3 kg (99.87 lb) shell at a rate of 6–8 rounds per minute. Barrel life time was expected to be 1,100 rounds. The pedestals guns range reached 22,000 m (24,060 yd), while the turrets, which could elevate further, reached 23,000 m (25,153 yd). Ammo supply range was between 1,600 and 1,800 shells total so around 133–150 shells per gun.

AA Artillery (FLAK)

FLAK 105 mm naval artillery and mount – From German ordnance catalog

The Scharnhorst and Gneisenau anti-aircraft battery comprised fourteen 10.5 cm C/33 L/65 guns in twin mounts and sixteen 3.7 cm L/83 guns also in twin mounts plus ten and twenty 2 cm guns, as designed.

-The 10.5 cm guns rate of fire was 15–18 rpm at a ceiling of 12,500 m (41,010 feet), using six Dop.L.C/31 twin mounts all placed amidships while the last one was superfiring over “C” turret placed on the quarter deck aft.

Depression/elevation was −8° +80°, maximum range of 17,700 m (19,357 yd) at 45°.

–The 3.7 cm guns were in eight twin Dopp LC/30 mounts, manually operated. They elevated to 85°, giving them a ceiling of 6,800 m (22,310 ft), but tracers were reached only 4,800 m (15,750 ft). Rate of fire was 30 rpm.

They had no torpedo tubes as designed, but after 1942, two triple 53.3 cm deck-mounted torpedo tubes from KMS Leipzig and Nürnberg were installed and storage or 18 G7a torpedoes provided for both vessels.

Fire control

KMS Scharnhorst and Gneisenau had two sets of Seetakt radar. The first was mounted on top of the forward gun director atop the bridge tower and the second on the rear main battery gun director. The Seetakt operated at 368 megacycles and 14 kW, but new models were installed later in the war, for 100 kW, and 80 cm wavelength (375 MHz.).

KMS Deutschland specifications |

|

| Dimensions | -Length 235 meters (771 ft) overall, 226 meters waterline -Beam 30 meters (98 ft) -Draught 9.69 meters (31.8 ft) |

| Displacement | 32,100 long tons (32,600 t) (standard) 38,100 long tons (38,700 t) (full load) |

| Crew | 1,669 (56 officers, 1613 enlisted) |

| Propulsion | 3 screws, Germania/Brown, Boveri & Co geared turbines 151,893 PS (149,815 ihp; 111,717 kW) |

| Speed | 31 knots (57.5 km/h; 35.6 mph) |

| Radius | 7,100 nmi (13,100 km; 8,200 mi)/19 knots Gneisenau: 6,200 nmi (11,500 km; 7,100 mi) at 19 knots |

| Armament | 9 × 28 cm/54.5 (11 inch) SK C/34 12 × 15 cm/55 (5.9″) SK C/28 14 × 10.5 cm/65 (4.1 inch) SK C/33 16 × 3.7 cm/L83 (1.5″) SK C/30 10 (later 16) × 2 cm/65 (0.79″) C/30 or C/38 6 × 533 mm torpedo tubes |

| Aviation | 3 Arado Ar 196A-3, catapult | Armor | Belt: 350 mm (13.8 in) Deck: 50 to 95 mm (2.0 to 3.7 in) Turrets:200 to 360 mm (7.9 to 14.2 in) Conning tower: 350 mm |

KMS Scharnhorst in november 1943, in the “Norway” pattern.

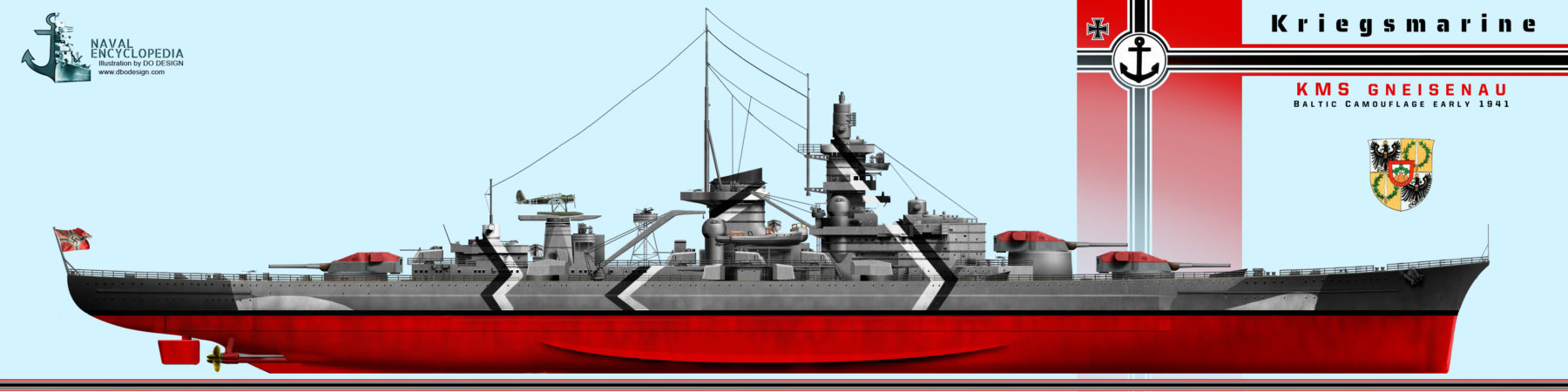

Author’s HD illustration of the KMS Gneisenau in 1938 with the initial prow.

Author’s HD illustration of the KMS Gneisenau in early 1941 in the Baltic

Another HD 3 views picture

KMS Gneisenau in February 1942 after Operation Cerberus

KMS Scharnhorst November 1939 training in the baltic after her bow reconstruction

The Scharnhorst in action

Scharnhorst in Port

At her commissioning, KMS Scharnhorst was commanded by Kapitän zur See (KzS) Otto Ciliax. His service tour was rather brief as he had to leave in September 1939 because of illness replaced by KzS Kurt-Caesar Hoffmann, holding his post until 1942. On 1 April 1942 he was promoted to Konteradmiral, awarded the Knight’s Cross, while the battleships’s new captain was KzS Friedrich Hüffmeier, replaced in October 1943 by KzS Fritz Hintze, killed in action during the ship’s final battle ().

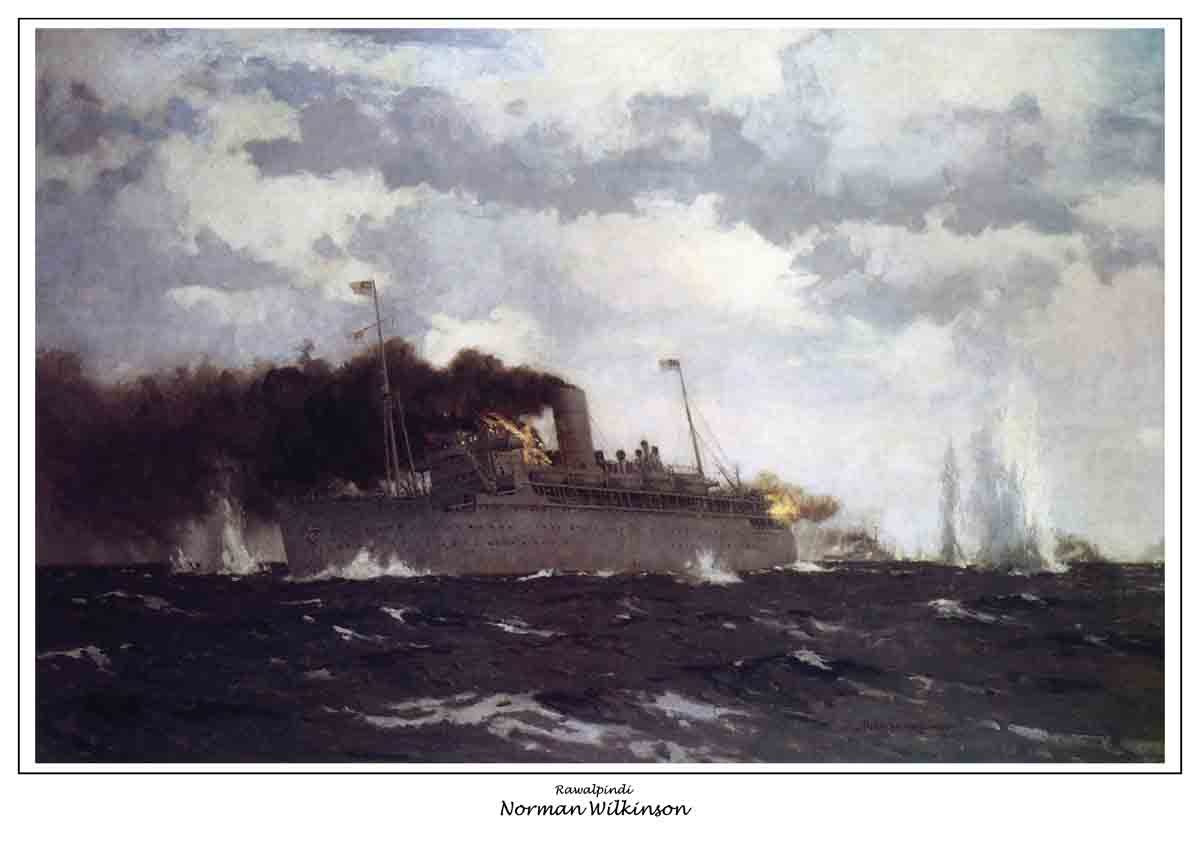

Atlantic rampage: The sinking of Rawalpindi

The sinking of Rawalpindi, famous painting by Norman Wilkinson

First operation as commerce raider as intended started with Gneisenau, her sister ship, on 21 November 1939. Flanked and screened by the light cruiser KMS Köln and nine destroyers, they were patrol between Iceland and the Faroe Islands, hoping to draw out British units, notably as a diversion for the Panzerschiffe for Admiral Graf Spee then in hot pursuit in the South Atlantic. On the 23, the German flotilla spotted the armed merchant cruiser Rawalpindi. At 16:07 this day, lookouts identified it positively as a target of choice and both battleships opened fire. Rawalpindi was an AMC, armed with old 150 mm guns and acting as a sherpherd for its convoy, which was order to flee while she stayed behind facing the onslaught. Despite the gallantry, the Rawalpindi was jopelessely outranged and outgunned. The hellish twins of the Kriegsmarine made short work of this, as in a hour later they had catch up to range and opened fire at 17:03. Just three minutes later the first salvo of hter main gun landed on Rawalpindi’s bridge. Captain Edward Coverly Kennedy was killed instantly as well as most officers present. Despite of this, Rawalpindi still managed to score a hit on Scharnhorst, causing just splinter damage. By 17:16 this was practically over. Rawalpindi was sinking while burning fiercely. Admiral Wilhelm Marschall onboard Gneisenau ordered bith ships to stop to pick up survivors with their boats. The rescue operations was cut short however by the spotting of cruiser HMS Newcastle (Town class). The squadron broke and fled north while weather deteriorated fast. They headed south through the North Sea while four allied capital ships, Hood, Nelson, Rodney and, Dunkerque (their nemesis) were in hot pursuit. They reach Wilhelmshaven on 27 November. Scharnhorst had short repairs afterwards in Wilhelmshaven, but her boilers were overhauled.

Operation Weserübung

Scharnhorst sailed into the Baltic Sea for gunnery training but the winter ice soon had her confined in port until February 1940. Both could then return to Wilhelmshaven, arrriving on 5 February and assigned to the force mustered for Operation Weserübung: The invasion of Denmark and Norway. Scharnhorst and Gneisenau had to provide a distant cover for the ships designed for the assaults on Narvik and Trondheim. They departed Wilhelmshaven on 7 April with the heavy cruiser KMS Admiral Hipper. Around 14:30, the flotilla was attacked by bombers, scoring no hits. That was the first of the many demonstration that high altitude bombers could not do much agains fast movine battleships, contrary to General Douhets theories widely believed by the general staff at the time. Heavy winds however did more structural damage as well as flooding. Scharnhorst’s fuel stores suffered of this.

HMS Renown

Duel with HMS Renown

At 09:15 however, the flotilla spit up as Admiral Hipper reinforced the destroyers at Narvik, already engaging a British force here. On 9 April, the “zwilling” (twins) spotted the battlecruiser HMS Renown, spotted by Gneisenau’s Seetakt radar first at 04:30. Crews were called to combat stations and 30 min. later Scharnhorst’s navigator spotted gun flashes from Renown, hile themselves responded three minutes later. Gneisenau took tow hits right away: One shell disabled her rear gun turret while Scharnhorst’s radar shut down. At 05:18, Renown, shifted fire from Gneisenau to Scharnhost and the latter started maneuvered to avoid plunging fire. At 07:15, both German schachtschiffe nevertheless used their higher speed to to evade Renown successfully while heavy seas provoked some flooding especially for Scharnhorst’s forward turret, which at some point went out of action while mechanical problems with her starboard turbines forced both to reduce theur speed to 25 knots. Still this was enough to take their distance.

Second Raid on Norway

Scharnhorst arrived off Lofoten, Norway on 9 April at midday like her sister, and both turned west while temporary repairs were done onboard, then steamed west, then south to meet KMS Admiral Hipper on 12 April. They were spotted by an RAF patrol aircraft which was followed by an air attack. Poor visibility¨protected them however. In the end, the squadron reached port in the evening. Scharnhorst was repaired at the Deutsche Werke in Kiel during which the aft turret aircraft catapult was removed. Both left Wilhelmshaven on 4 June joined by Admiral Hipper and four destroyers on their way to Norway. The objective was to disrupt Allied reinforcements and supplies to the Norwegians. On 7 June, they were resupplied by the tanker Dithmarschen and a day after spotted a British corvette, which was promptly sunk together with the oil tanker Pioneer. Arado 196 floatplanes were soon in the air to try to spo other targets of opportunity. Later Admiral Hipper and destroyers were detached to sunk the 19,500 long tons passenger ship SS Orama but spared the hospital ship Atlantis. Admiral Hipper and the destroyers later refuelled in Trondheim before going to the Harstad area.

Scharnhost firing on HMS Glorious

Destruction the Glorious

At 17:45, both battleships spotted at 40,000 m (44,000 yd) the British aircraft carrier Glorious and her two escorting destroyers, HMS Ardent and Acasta. At 18:32 Scharnhorst was closer and opened fire at 26,000 m (28,000 yd). Six minutes later she started to hit Glorious at 25,600 m (28,000 yd). On shell penetrated the upper hangar a massive fire broke out. After ten minutes, Gneisenau’s shells fell on the Glorious’s brdge, killing the captain and staff. The two destroyers bravely tried to distract the German battleships by obscusing them laying smoke screens, but radar still provided the position of their target. A 18:26 both ships fired now at 24,100 m (26,400 yd), at maximum rate of fire, nearly 63 shells per minute were falling on the carrier and this went on for an hour. Glorious eventually capzied and sank to the bottom as her two destroyers. However, before sinking HMS Acasta closed enough to launch a volley of 4 torpedoes on Scharnhorst. One of these hit her at 19:39 while one of her Acasta also hit 4.7″ shell landed on Scharnhorst’s forward superfiring turret without damage contrary to the torpedo; The latter blew a hole 14 by 6 m (15.3 by 6.6 yd) followed by a flooding of around 2,500 tons of sea water. The rear turret stopped working and 48 men were killed or drawn. The ship listed 5 degree at the rea, the stern lower for a meter and speed fell to 20 knots. Her machinery suffered from the flooding, and the starboard propeller shaft was dislodged by the impact.

HMS Glorious last trip, with her escort destroyers.

This forced Scharnhorst to leave her mission to join Trondheim for temporary repairs on 9 June. There, the Germans had posted the repair ship Huaskaran, but a day later, she was spotted there by the RAF followed by a raid by twelve Hudson bomber. They dropped 36 armor-piercing bombs which all missed but meanwhile, the British admiralry had dispatched the battleship Rodney and carrier Ark Royal. On 13 June, Ark Royal launched fifteen Skua dive bombers, which were interceptedby German Me 109 fighters and shot more than half. The other remaining seven arrived over Trondheim, braved the FLAK and attacked Scharnhorst. The single bomb that hit the battleship was a dud. After repairs were completed at a hellish pace on 20 June, Scharnhorst rushed at sea to make he way back home, under heavy escort. While underway, she was attacked on 21 June twice by air attacks, Swordfish and Beaufort bombers. Between her AA and her fighters escort, they were driven off. Meanwhile British radio traffic indicated the fleet was rushing toward her, so Scharnhorst sailed to Stavanger while the British capital ships arrived within 35 nautical miles (65 km; 40 mi) of Scharnhorst. However Stavanger was well guarded, including by the Luftwaffe, and the British ships did not ventured close. This respite led Scharnhorst to leave the following morning Stavanger for Kiel. Her extensive repairs lasted six months.

Scharnhorst firing against HMS Glorious

Operation Berlin

Scharnhorst started her post-repairs trials in the Baltic ad was back to Kiel in December 1940. There, she met Gneisenau prepared for Operation Berlin. This was a planned raid into the Atlantic, preying on Allied shipping lanes, on which great hopes were placed by the naval staff. Bismarck was not yet in service. But the perio was known for its severe storms. Whle at sea, massive waves flooded and damaged Gneisenau, less Scharnhorst, but this was enough to return into port, Gotenhafen for Scharnhorst, Kiel for her sister ship to be repaired. On 22 January 1941, both ships under command of Admiral Günther Lütjens, left for the North Atlantic. They were detected passing through the Skagerrak. The Home Fleet scrambled and deployed to place itself between Iceland and the Faroes. The Germans detected this force by radar at long range, and Lütjens managed to avoid the British and by 3 February, after evading the last British cruiser they were in the open Atlantic, ready to create havoc.

Scharnhorst started her post-repairs trials in the Baltic ad was back to Kiel in December 1940. There, she met Gneisenau prepared for Operation Berlin. This was a planned raid into the Atlantic, preying on Allied shipping lanes, on which great hopes were placed by the naval staff. Bismarck was not yet in service. But the perio was known for its severe storms. Whle at sea, massive waves flooded and damaged Gneisenau, less Scharnhorst, but this was enough to return into port, Gotenhafen for Scharnhorst, Kiel for her sister ship to be repaired. On 22 January 1941, both ships under command of Admiral Günther Lütjens, left for the North Atlantic. They were detected passing through the Skagerrak. The Home Fleet scrambled and deployed to place itself between Iceland and the Faroes. The Germans detected this force by radar at long range, and Lütjens managed to avoid the British and by 3 February, after evading the last British cruiser they were in the open Atlantic, ready to create havoc.

On 6 February, they refuelled from the tanker Schlettstadt off Cape Farewell. After 08:30 on 8 February, lookouts spotted convoy HX 106. It was escorted by the battleship HMS Ramillies and Lütjens, under instruction from Hitler, forbade anu engagement. The attack was called off as a result but still, Captain KzS Hoffmann (Scharnhorst) closed to 23,000 m (25,000 yd) to try to lure Ramillies away from the convoy, in order to allow Gneisenau to prey on the convoy. This was immediately stopped by Lütjens and the two battleships veered northwest in search of shipping. On 22 February, they spotted as small convoy sailing west to load in the US. They dispersed when the battleships were spotted and Scharnhorst sank the 6000 ton tanker Lustrous before the attack was called off again: Lütjens indeed decided to take new positions as the convoy sent distress calls warning the Royal Navy. Lütjens choice was a risky one: The Cape Town-Gibraltar convoy route, far away to the south. This meant both ships would head fot the northwest of Cape Verde. While underway, they encountered another convoy, this time escorted by HMS Malaya of the Queen Elisabth class on 8 March. Again, Lütjens forbade any attack, but both vessels tracked and shadowed the convoy while directed U-boats. Just two of them headed there and sank a 28,488 tons of shipping during the night to 9 March. Malaya’s lookouts evebtually spotted the German battleships and turnd to attack them, closing at at 24,000 m (26,000 yd). Still, Lütjens refused to open fire and ordered to break away from the engagement. Scharnhorst and her sister ship veered west in the mid-Atlantic. This gave the occasion to Scharnhorstto spot and sinke an isolated cargo, the Greek Marathon. Both later refuelled from the tankers Uckermark and Ermland on 12 March.

On 15 March, both battleships were headed with the tankers to meet what was left of a dispersed convoy in the mid-Atlantic because of an U-Boat attack. Scharnhorst sank two ships and later the main body of the convoy was located. Scharnhorst alone would sank seven ships for a total of 27,277 tons. But a surviving ships meanwhile sent a warning and location of the German battleships. The naval staff HQ directed HMS Rodney and King George V on this position at full sped. Scharnhorst and Gneisenau evaded them nevertheless. Lütjens however at this point beliweve he has tested their luck enough and it was time to wrap up and leave. He gave ordered to head for Brest, reached on 22 March. Scharnhorst’s technical crew were hard at work afterwards to fix superheater tubes in her boilers. This was carrie dout until July. Because of this, Scharnhorst missed Operation Rheinübung, another raid by Bismarck in May 1941.

Scharnhorst targeted by the RAF

Scharnhorst moved from Brest to la Pallice for post-repairs trials on the 21. She receive instructions not to reach Brest to avoid concentration of heavy units in Brest, now Prinz Eugen was there on 21 July. This would have been too tempting for the RAF. Instead she stayedat La Pallice on 23 July. Meanshile, the RAF planned a large raid on Brest planned for the night of 24 July. Aerial reconnaissance however signalled Scharnhorst at La Pallice and the operation was altered. The RAF despatched a squadron of Halifax heavy bombers (No. 35 Sqn) and No. 76 Squadron. They took off and crossed 200 miles (320 km) to reach Scharnhorst at La Pallice. Meanwhile the raid on Brest targeted Prinz Eugen and Gneisenau. Meanwhile 15 Halifaxes attacked Scharnhorst and scored five hits on her starboard side. Three of the 454 kg (1,001 lb) armor-piercing bombs and two HE 227 kg (500 lb) bombs. One landed on her deck forward of the starboard 15 cm twin turret and conning tower, passing through the both decks and exploded in the main armored deck, somewhat containing the blast. The torpedo bulkhead was badly damaged and flooding started. A second HE bomb fell forward of the rear main battery turret. Again, it made through two decks and also exploded on the armored deck. This time, it blew a hole in it and caused splinter damage.

Two AP 454 kg bombs hit amidships, between the 15 cm and 10.5 cm gun turrets, fortunately they were duds. The first went through each deck to exit through the double bottom, causing severe flooding, while the other slided along the torpedo bulkhead and ended near side belt armor. The third fell aft of the rear 28 cm turret, 3 m from the side and also failed to detonate. Because of the flooding, the ship took at her mooring a 8 degree list to starboard. Both main turrets and half her anti-aircraft battery were out of action, and the crew had two KiA and fifteen injured but damage-control teams later corrected the list with counter-flooding. Scharnhorst was able to leave La Pallice for Brest at 19:30. The following morning, 25 July, one of the escorting destroyers shot down a British patrol plane and signalled it, but Scharnhorst reached Brest in the later afternoon and joined the drydock for extensive repairs. She was immobilized there 4 months. Meanwhile, the Germans sent there a new radar system to be installed aft, capable of 100 kW. Also 53.3 cm torpedo tubes banks from a former cruiser were also installed. Her sister ship also had been damaged seriously and in repairs, and the location of the two battleships in Brest was precarious to say the least. Bt that point, all German capital ships deployed to the Atlantic were out of action, and there was a real danger of anoher raid of the RAF. FLAK and fighters were mobilized around Brest for this occurence.

Operation Cerberus: The Channel Dash

Quite a famous episode in the life of boh battleships. On 12 January 1942, the German Naval Command was in conference with Hitler to relate about the dangerous location where the German battleships were in. At one hand, it gave them easier access to the Gulf of Biscay and mid-atlantic, but the port was too close to British shore. It was decided at the end of the reunion to return the “terrible twins”, Scharnhorst, Gneisenau, together with Prinz Eugen back to Germany, even if this meant hading straight through the Channel. Other options had been studied, like a great manoeuver westwards and around the British Island, north to Greenland and Iceland, but this long journey would have been too tempting. The fastest, shortest way won the decision. It was also decided to redeploy the squadron to Norway, to prey on convoys to Murmansk. The “Channel Dash” (Unternehmen Cerberus) was an attempt to avoid Allied radar and patrol aircraft of the Atlantic. Vice Admiral Otto Ciliax hoisted his flag onboard Scharnhorst for this operation. In early February, minesweepers started to clean up minefields on their way in the channel, and performed still undetected by the British.

At 23:00 on 11 February, the operation started. It could have been a disaster, and the British prepared detailed plans in advance for just such eventuality. Scharnhorst, Gneisenau, and Prinz Eugen left Brest that day, entering the Channel at 27 knots (50 km/h; 31 mph) staying very close to the French coast, also to avoid radar and visual detection. The British failed to detect their departure and luck was maintained along the way. A submarine in faction just went to port recharge its batteries. By 06:30, both ships were already off Cherbourg, joined by a flotilla of torpedo boats led by Kapitän Erich Bey (Z29). The Luftwaffe was also scrambled for an air cover, under command of General Adolf Galland, in what was called Operation Donnerkeil. The fighters flew low, and stayed close also to avoid radar detection and there were liaison officers onboard on all three ships to coordinate the air cover. In addition, German aircraft jammed British radar with chaff. By 13:00, the flotilla was off the Strait of Dover and 30 min. later were attacked at last by six Swordfish torpedo bombers with Spitfire escort. The Luftwaffe defense was impenetrable, and all six Swordfish were shot down.

Scharnhorst was the only ship damaged however. At 15:31 she struck an air-dropped magnetic mine off the Scheldt. It hit abreast of the forward superfiring turret, damaging the ship’s circuit breakers, knocking out her electrical system for 20 minutes. Her superfiring forward turret was jammed, as well as all twin and single 15 cm mounts on the port side, the fuel oil pumps, bearings of the turbo-generators. Power shut and the ship had to stop for emergency measure to switch power from the boilers and turbines. The hull was also damaged, with a large gash leaving 1,220 t of seawater flooding 30 watertight spaces. As a result, Scharnhorst took a list of one degree. Admiral Ciliax decided to transfer his flag on Z29. The engine room crews restarted the first turbine at 15:49, twenty minutes after, a miracle. But dictated by the extreme situation the battleship was in, just under the nose of the British shore. The second and third turbines were restarted later, the last at 16:01. Scharnhorst, dead on the water for half an hour, was notw able to speed up to 27 knots (50 km/h; 31 mph), and she was able to restart her last turbine when an isolated bomber spotted the ship and closed to attack. It dropped several bombs 90 m (98 yd) off her port side. Later, twelve Beauforts bomber attacked Scharnhost for ten minutes. It was beaten off by AA fire and the Luftwaffe again. Other attacks followed with the same result, leading the AA to become red-hot and short of ammo at the end of the operation. This was nothing short of an humiliation for the Royal Navy and RAF, and PM Churchill was understandably furious.

However, Scharnhost was not safe yet. While she was underway off Terschelling she hit another magnetic mine on the starboard side, at 22:34. Again, the blast knowked out the whole power system and jammed the rudders as well as two turbines while the third was turned off soon afterwards. The blast created a hole leaving 300 tons of seawater flooding ten watertight spaces. The ship by that point had only its centerline shaft operational and was able to run at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph). The teams yet again performed the impossible and partial power was restored, first to the starboard turbine (now the ship reach 14 knots) but her main gun turrets and 15 cm turrets were all jammed. At 08:00, Scharnhorst at last made it to the Jade Bight. There, she was to wait for iceabreakers to clear her way to Wilhelmshaven. Admiral Ciliax returned from the torpedo boat to Scharnhorst, raising his flag again. At noon, the ice was cleared and Scharnhorst entered Wilhelmshaven. before heading to Kiel two days after for long repairs in a floating dry dock. Work was completed by July 1942, after which she made sea trials in the Baltic, revealing her boiler tubes needed replacement.

Scharnhorst in Norway (August 42 – Nov. 1943)

In early August 1942, Scharnhorst started exercises with U-boats and collided with U-523, sending her in dry-docking for repairs, completed by September 1942. She trained in the Baltic and was sent to Gotenhafen to be fitted with a new rudder. It has been designed based on reports of the torpedo damage on Prinz Eugen and Lützow. Boiler and turbines issues however had the ship immobilized until December 1942. By that time she had indeed only two shafts operational. It was decided at this point to overhaul completely her propulsion system. It was don quickly as Scharnhorst was ready for action again in early January 1943. She made verification trials and departed on 7 January with Prinz Eugen and five destroyers for Norway. However she soon received a warning of British air activity near the coast and headed back to port. She made another attempt later with the same result, but on 8 March, poor weather allowed the squadron to head for Norway, greeted by a severe storm off Bergen. Scharnhorst went on at 17 knots (31 km/h; 20 mph) without the destroyers, which took refuge and she arrived at 16:00 on 14 March, in Bogen Bay, outside Narvik. There, were already present the bulk of what was left of the Kirgsmarine at that point: The Lützow and Tirpitz.

On 22 March, all thee made their way to Altafjord for heavy storms light damage. In early April, Scharnhorst, Tirpitz escorted by nine destroyers trained at Bear Island in the Arctic. On 8 March, Scharnhorst suffered an internal explosion in her aft auxiliary machinery space, just above the armor deck. It killed or injured 34 men. The crew flooded the magazines of the aft turret (“Caesar”) as a precaution. A repair ship was present to complete repairs in just two weeks. Neverthelss, Germany was experiencing severe fuel shortages, reserved for the U-Boats, which prevented any operation for six months. This time was spent in short training maneuvers.

Scharnhorst, Tirpitz then departed from Altafjord on 6 September for Operation Zitronella. They carried troops and were tasked to cover landings on the island of Spitzbergen. Scharnhorst selenced a battery of two 3 inches gun, set ablaze fuel tanks, coal mines, harbor facilities, and military installations. The weather station, main meteorologica source for the allies fo the northern convoys to USSR was destroyed while about 1,000 landed troops pushed the Norwegian garrison into the mountains. On 22 September while the squadron was back, British X-craft attacked Tirpitz, which was seriously damaged. There was only Scharnhorst left with five destroyers available for future operations. On 25 November 1943 Scharnhorst made a two-hour full-power trial, reaching only 29.6 knots compatred to her 1940 trials of 31.14 knots. This was perhaps a presage her speed could not save her.

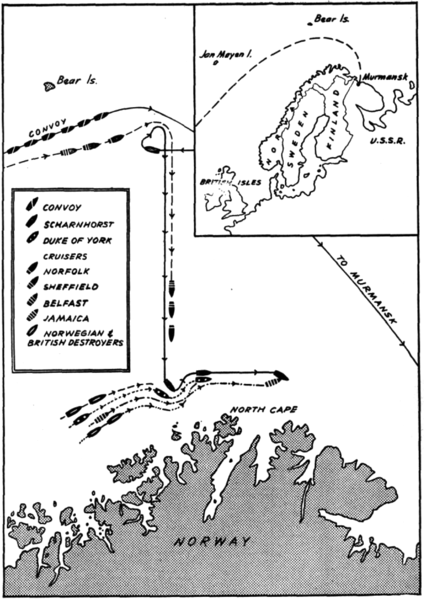

A dramatic end: The Battle of the North Cape

In December 1943 it was more important than ever to interrupt allied supplies to USSR via the north road. Between the German Army in fighting retreat and a weakened Luftwaffe and increased Allied ASW and naval presence, Hitler and the nava staff still believed Scharnhorst and Tirpitz could do smething together with the four remaining cruisers in the Baltic. There was a conference with Hitler on the subject held on 19–20 December. Großadmiral Karl Dönitz agreed to deploy Scharnhorst to attack the next Allied convoy by any means necessary. The operation was supervised by Konteradmiral Erich Bey. The task force setup around Scharnhorst was gathered and prepared on 22 December, made ready to go within a three-hour notice. Luftwaffe reconnaissance aircraft located a convoy with 20 transports, only escorted by cruisers and destroyers around 400 nautical miles west of Tromsø. Two days later its course was confirmed, and orderes were sent for an interception course. The convoy position was cornfirmed again by an U-boat at 09:00 on 25 December. Dönitz ordered Scharnhorst to go, but also to break off if a capital ship was spotted or signalled, while still be aggressive enough to inflict maximal damage to the convoy. Bey and Dönitz hoped the Atlantic 1941 carnage could be repeated. Attack was planned to start at 10:00 on 26 December, independent of the weather. There was by then only 45 minutes of full daylight available for six hours of twilight, and Allied radar-directed fire control greatly impproved, allowing accyrate fire in any conditions of weather, day and night. The German radar lagged behind at that point.

HMS Duke of York

Scharnhorst departed with five destroyers around 19:00, in open sea four hours later and at 03:19, instructions were received that Scharnhorst was to conduct the attack alone in case of heavy seas, as the destroyers fighting capabilities would have been severely reduced. This last message was intercepted by British and Admirals Robert Burnett and Bruce Fraser positioned their forces, waiting for the Scharnhorst to arrive. At 07:03, about 40 nautical miles southwest of Bear Island at 10:00 as planned, the German battleship was in position to attack the convoy. On his side, Admiral Burnett had under orders the cruisers Norfolk, Belfast, and Sheffield. He placed these in between the Convoy JW 55B and the planned approach route of Scharnhorst. Meanwhile, Admiral Fraser was on board the battleship Duke of York, recently in commission, with crews eager to fight. She made another squadron with the cruiser Jamaica and four destroyers. Fraser moved southwest of Scharnhorst’s path, blocking his escape. The trap was set.

An hour after this, Conter-Admiral Bey deployed his destroyers to screen Scharnhorst, 10 nautical miles behind. Battle stations was signalled in preparation for the attack and at 08:40, HMS Belfast spotted Scharnhorst on her radar while the latter ignored they had been detected, turning off their own radar to prevent the Brtish to pickup its signals. At 09:21, Belfast’s lookouts spotted in turn the approaching Scharnhorst at about 11,000 m (12,000 yd), and opened fire when in range three minutes later, soon joined by Norfolk. Scharnhorst fired in response and turned to stay away, increasing speed. She was hit twice by 8 inches shells, one dud, one disabling her forward rangefinders and radar antenna. Only the aft radar was left now for detection. Scharnhorst turned south to evade the cruisers, which stayed close, following her by radar. She then tuened northeast of the convoy, spotted again by Belfast. The cruisers then took 20 minutes to coordinate their moe and be close enough to fire again on Scharnhorst, which detected theem with her aft radar, and opened fire in response. After two volleys, she broke off, and again, turned away to disengage. Around 12:25, Scharnhorst ma,aged to hit Norfolk twice, destroying her gunnery radar and the second hit “X” barbette and jammed the turret. Increasing speed, Scharnhorst tried to escape and later find the convoy. Burnett kept his distance too, only shadowing Scharnhorst. Fraser mweanhile arrived with the Duke of York. Scharnhorst’s screen of destroyers failed to locate the convoy and at 13:15, Counter-admiral Bey seeing this was going nowhere and the destroyers were dangerously kow on fuel, decided they would head for home. At 13:43, order was given and the destroyers left Scharnhorst alone.

At 16:17, HMS Duke of York at last made radar contact. 30 minutes later, HMS Belfast was close enough to fire illuminating shells on Scharnhorst, allowing the Duke of York to open fire at 16:50, from 11,000 m (12,000 yd). Scharnhorst returned fire and manouvered to dodge the first volleys. Five minutes later, Duke of York hit first: One of her 14 in shells struck Scharnhorst abreast of her forward gun turret, jamming the turret’s training gears while splinters started a fire in the ammunition magazine, flooded as well as the other forward magazine, but the water was quickly drained to allow Bruno’s turret to resume fire again. Another struck the ventilation trunk (Bruno turret), which was destroyed. Due to this, the turret was invaded by noxious propellant gases each time the breeches were opened. A third shell hit close to the turret Caesar and caused flooding while splinters killed many. Next the forward 15 cm gun turrets were both hit and destroyed.

It was about 18:00, when another shell struck on the starboard side, going through the upper belt armor to land in number 1 boiler room. The propulsion system was so badly damaged Scharnhorst slowed down to 8 knots to repair, making her an easy target. Again, her teams made miracles, and she was soon able to speed up to 22 knots, adding 5,000 m (5,500 yd) to her distance to the Duke of York, firing salvo after salvo. Duke of York felt the Geran rapid-fire at this point. Many were killed by splinters, while her fire-control radar was jammed. But Fraser went on pounding the German battleship, in a fight to the finish.

The Gunners of Duke of York posing proudly after their duel with the Scharnhorst. This was the last ever big gun naval battle in Europe.

At 18:42, Duke of York ceased fire. In total, her guns had fired 52 salvos. Her lookouts reported at least 13 hits. Still Scharnhorst was able to keep the distance, her main armament still ârtially operational, but not her secondary armament. Fraser knew this was the right time to send the destroyers at his disposal. Like hunting hogs, HMS Scorpion and HNoMS Stord closed to the Scharnhorst enough to launch eight torpedoes at her at 18:50. Four hit, one abreast of turret Bruno (jamming it), another port causing minor flooding, another damaged the port propeller shaftand the fourth hit the bow. These achieved their objectives to slow Scharnhorst down to 12 knots, allowed the Duke of York to soon close to 9,100 m. By all means, ths spelled the end for the Scharnhost. Now only her aft turret (Caesar) was operational. The captain ordered that all available men tried to arry ammunitions forward to the aft turret, a daunting task fue to the weight of the shells and their propellant charges. Meanwhile, Fraser ordered HMS Jamaica, soon joined by Belfast to close into range and finish off the Scharnhorst, with guns and torpedoes. They did, and the German battleship, hit by more torpedo hits eventually stopped dead in the water, listed to starboard until at 19:45 she sank by the bow. Her propellers were still turning when her stern emerged high above the water. British ships searched for survivors, pulling 36 away even though voices could be heard in the darkness. As always, there was the danger of U-Boats. In addition, the water was freezing cold, so there was little hope for survivors.

Scharnhorst’s rare survivors transferred to Scapa Flow

Epilogue

Scharnhorst’s wreck was rediscovered in September 2000, by a joint expedition financed by the BBC, NRK, and the Royal Norwegian Navy. The survey vessel Sverdrup II scanned the sea floor and located a large submerged object after which the Royal Norwegian Navy’s HNoMS Tyr sent ROV to inspect the wreck. On 10 September, Scharnhorst was located under 290 m (950 ft) of water with her hull lying upside down in a cloud of debris, with the main mast and rangefinders scattered around. Damage from shellfire and torpedoes was clear, while the bow was blown off, more from a magazine explosion than collision with the bottom as it was found at some distance.

Documentary about the Scharnhorst.

The Gneisenau in action

KMS Gneisenau started her sea trials in the Atlantic in June 1939, carrying practice ammunition, and very few live rounds. By September 1939 she was back, and prepared for war. On the 4 September, she was attacked by fourteen Wellington bombers, but none scored any hit. In November 1939 her captain KzS Förste was replaced by KzS Harald Netzbandt and she started her first combat operation under command of Admiral Wilhelm Marschall on 21 November. With her sister ship Scharnhorst (which always accompanied her until 1942) and teaming with the light cruiser Köln and nine destroyers they started a patrol between Iceland and the Faroe Islands to draw out British units for Admiral Graf Spee in the South Atlantic. They sank the AMC Rawalpindi at this occasion.

Gneisenau was back in 27 November, slightly damaged by heavy seas and was repaired in Kiel in drydock, her bow modified again (the first tme was after her sea trials) to incorporate flare and sheer. She made her trials in tje Baltic in January 1940 but was blocked by ice when returning to the North Sea the Kiel Canal. Se she was only back by 4 February.

Operation Weserübung

Gneisenau was pepared for the invasion of Norway, as a distant covering force for the assaults on Narvik and Trondheim, under command of Vize Admiral Günther Lütjens. Leaving on 7 April with Admiral Hipper and fourteen destroyers they coveered the landings, hipper detached to land the troops she carried, while at 14:30 this day they were attacked by British bombers, scoring no hits. The following day Z11 Bernd von Arnim duelled with HMS Glowworm and Glowworm rammed Admiral Hipper. Battle stations were ordered, but none of the capital ships took patrt in the action. When night fell, they took up a position west of the Vestfjorden. During the night their Seetakt radars spotted the British battlecruiser Renown. Battle stations rang out and the first volley ffomr Renown started at 05:05. Gneisenau scored two hits on her one dud and on on the upper deck aknocking up the radio. Gneisenau disengaged while Renown’s 15 in (38 cm) struck Gneisenau. One hit the director tower but was a dud, cutting cables and killed an officer and five gratings while the other disabled the rear turret. Gneisenau increased speed and manoeuvered to break away. Gneisenau fired sixty 28 cm and eight 15 cm rounds during this first duel.

They were joined by Admiral Hipper on 11 April and returned to Wilhelmshaven. Repairs took place, including for the heavy weather. After the 29 April Gnesenau returned in the Baltic, however as she steamed to 22 knots on the morning of 5 May off the Elbe estuary, she struck a magnetic mine, 21 m (69 ft) off her port rear quarter, 24 m (79 ft) below the hull. Her hull was seriously damaged, flooding several compartments. She took a half-degree list to port and had problems with her starboard low-pressure turbine and tear rangefinders. Repairs took place in a floating drydock in Kiel until 21 May after which she made a brief shakedown cruise in the Baltic and back in Kiel for her next mission.

Operation Juno

The terrible sisters left Bremerhaven on 4 June to return to Norway, flanked again by the cruiser Admiral Hipper, and four destroyers. They were prey on Allied supplies to the Norwegians and relieve pressure on German troops here. On 7 June, the tanker Dithmarschen refuelled Hipper and the four destroyers and their planes spotted the Orama, sank, and spared the Atlantis. Later they spotted the aircraft carrier Glorious and her two escorting destroyers. Both battleships intercepted her and despite the valiant defence by her destroyers, she was destroyed. Acasta even succeeded to torpedo the Scharnhorst at 19:39 and Gneisenau accompanied her to Trondheim when it was clear British convoys were too heavily guarded.

Iceland and North Atlantic

Admiral Günther Lütjens became permanent commander of the squadron on 20 June, ordering a new sortie to Iceland. The operation by Gneisenau and Hipper was a diversion to allow Scharnhorst her safe return to Germany. It was a mock break out into the Atlantic. However when underway, they Gnesenau was torpedoed by the submarine HMS Clyde. She took two hits in the bow, forward of the splinter belt. The ship took hundreds of tons of seawater in her two forward watertight compartments, forced to return to Trondheim at low speed to be patvhed up by the repair ship Huascaran. She returned to Kiel on 25–27 July under escorted by Hipper and Nürnberg plus four destroyers, and six torpedo boats. The British Home Fleet tried to intercept the flotilla, but it escaped. Gnesenau was in drydock at the Howaldtswerke dockyard, for five months. In August, KzS Otto Fein became her new captain, for the remainder of her active life.

The battleship Ramillies, guarding the convoy HX 106

Operation Berlin