Japan, 1940-45. Fleet Aircraft Carriers: Shōkaku 翔鶴, Zuikaku 瑞鶴

Japan, 1940-45. Fleet Aircraft Carriers: Shōkaku 翔鶴, Zuikaku 瑞鶴WW2 IJN Aircraft Carriers:

Hōshō | Akagi | Kaga | Ryūjō | Sōryū | Hiryū | Shōkaku class | Zuihō class | Ryūhō | Hiyo class | Chitose class | Mizuho class* | Taihō | Shinano | Unryū class | Taiyo class | Kaiyo | Shinyo | Ibuki |The best ever IJN fleet carriers ?

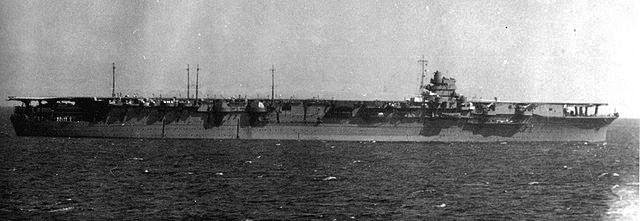

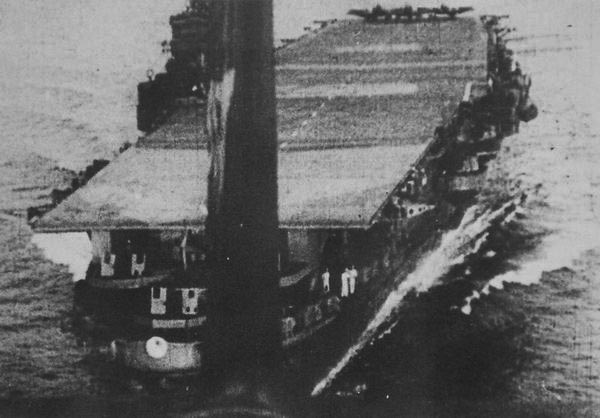

Shōkaku in Yokosuka, August 23, 1941

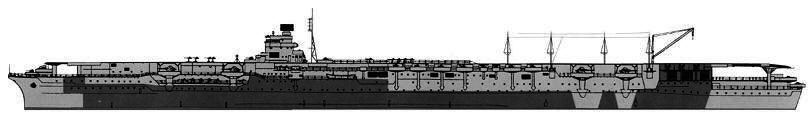

Shōkaku and Zuikaku in many ways represented the pinnacle of IJN aicraft carrier development in 1937. Unbound by treaty limits since December 1936, engineers were now free to work out the design the Japanese admiralty really wanted. Planned with 96 aicraft initially, more than the American Lexington/Yorktown or any British carrier, this was revised to a more modest 72 (plus spares) modern models. Low and still very fast at more than 34 knots, well armed and better protected than any aicraft carrier before them, they really were the fulcrum of the Kido Butai, just ready in time to participate to the Peark Harbor Attack. They participated in the Indian Ocean raid, the Battle of the Coral Sea, fatefully missed the battle of Midway, but were at Santa Cruz and the Solomons (Guadalcanal), before meeting their fate at the Battle of the Philippine Sea in June and of Leyte in October 1944.

Accelerated development of the Shōkaku class

If you followed the past articles, you saw the development line of Japanese aircraft carriers, and the Shōkaku class (翔鶴型, Shōkaku-gata) were the logical end of this. They are seen today among specialists as the finest aicraft aircraft carriers ever built by Japan, at least until the Taihō (1943). The Shoho was a prototype, the Kaga–Akagi still largely experimental conversions, the Ryūjō a prototype light carrier, and the Soryu–Hiryu peacetime (treaty) fleet carriers. After Japan retired from the London treaty in 1935, also unbound by the Washington treaty, the Imperial Japanese Admiralty was free to ask for a new class of fleet carriers, unencumbered by tonnage limits, but still derived from the previous Hiryu to spare development time. So ythis is a chapter we will not dewelve much about. In addition all original blueprints from the ships are lost.

The two Shōkaku-class were ordered in 1937, so two years later, as part of the 3rd Naval Armaments Supplement Program. Without restrictions expired in December 1936, and more relaxed budgetary limitations in the new politcal context, the IJN now wanted to gain a clear superiority over its probable adversaries (chief concerns were Britain and the USA). The Navy General Staff therefore had little time in 1937 for extensive R&D and laid out an ambitious requirement for ships capable of carrying 96-aircraft as Akagi combined with the record speed of Hiryū, and same defensive armament as Kaga, so far considered the best, as well as superior protection and range, not only compared to Japanese, but also foreign carriers. They really were planned as the spearhead of the first air fleet for future operations deep in the Pacific, and more to be built behind.

The Basic Design Section of the Navy Technical Department (艦政本部, kansei honbu) somewhat equivament to the US Ordnance bureau naval branch, decided to gain time, to start on the Hiryū design and improve it wholesale. It was also given a unconventionally located island, on the port side amidships initially. But design development was made at breakneck speed, with the same design simply stretched up and improved in many ways.

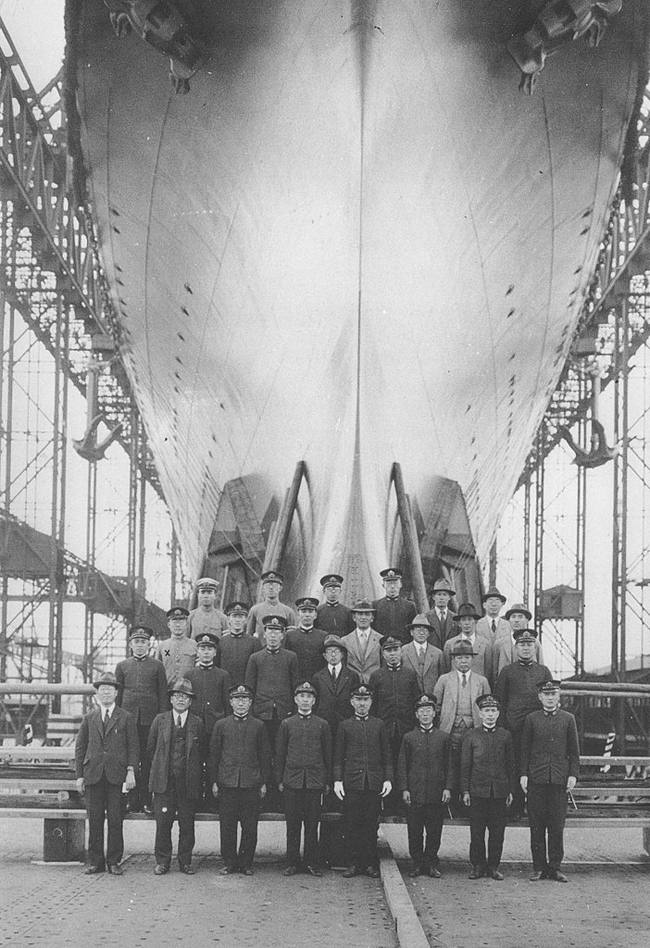

The engineers and officers at Yokosuka naval yard posing in front of the prow before the launching ceremony of IJN Shokaku.

Construction of Shōkaku and Zuikaku

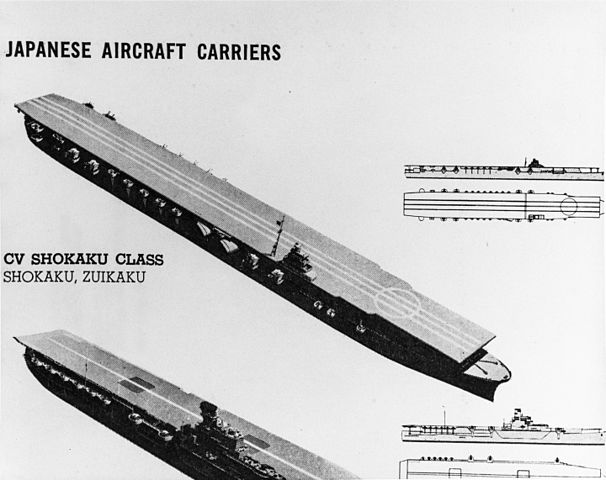

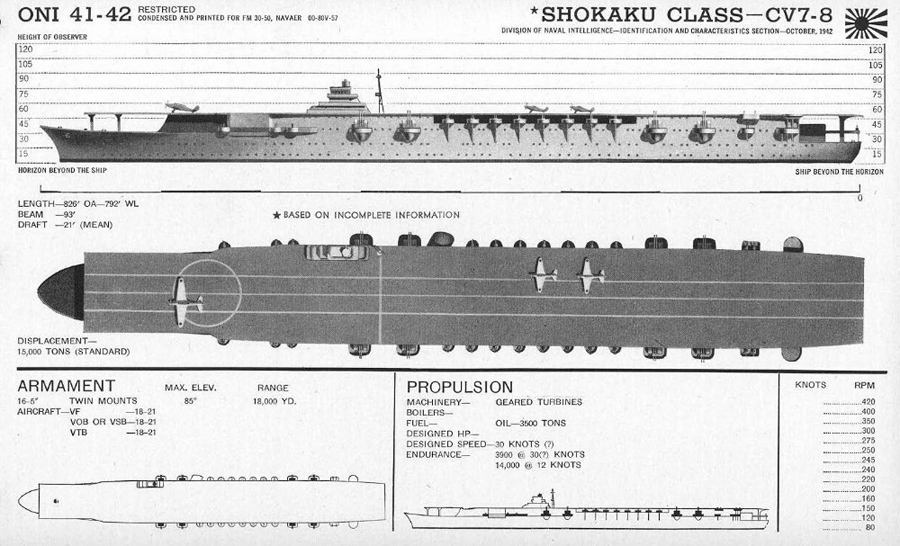

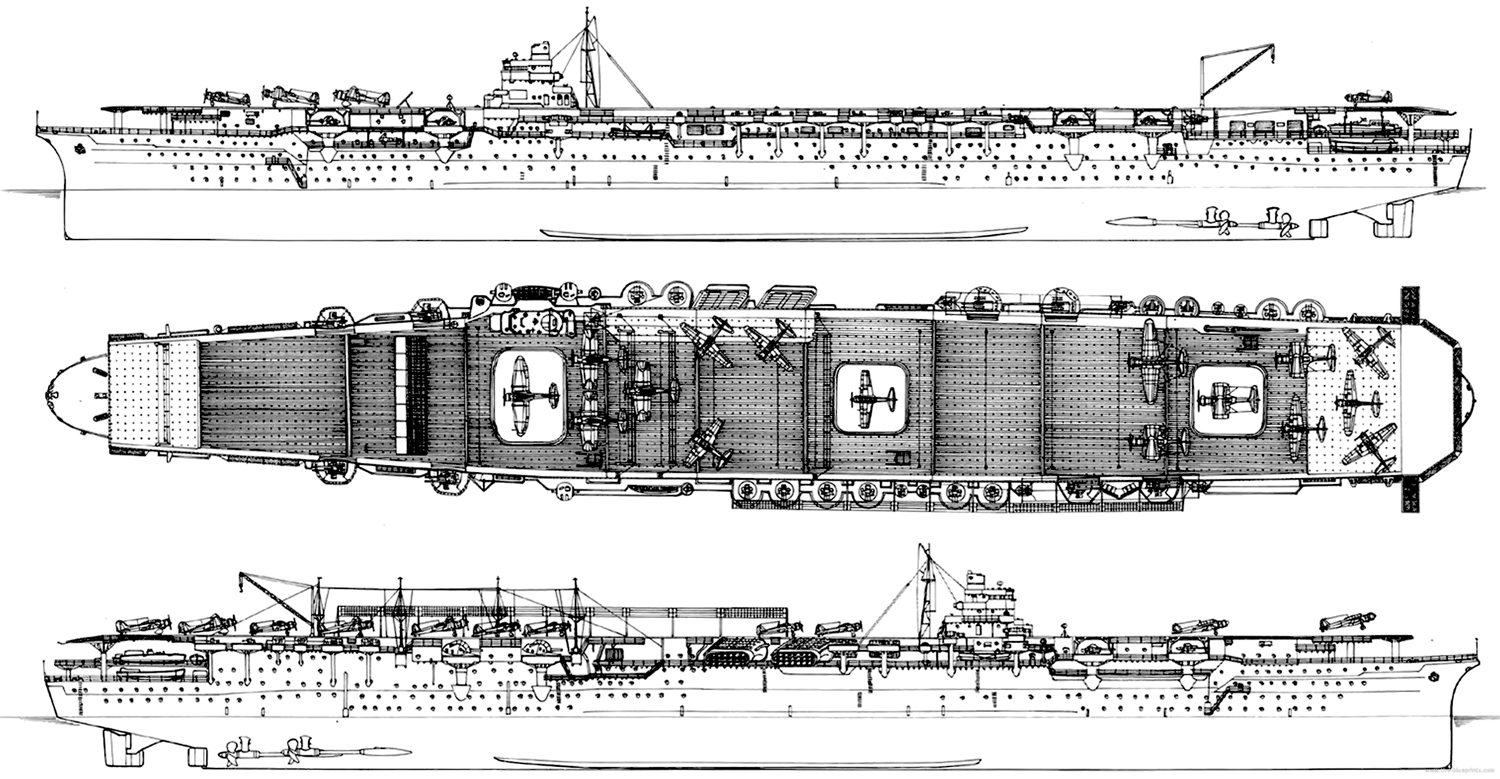

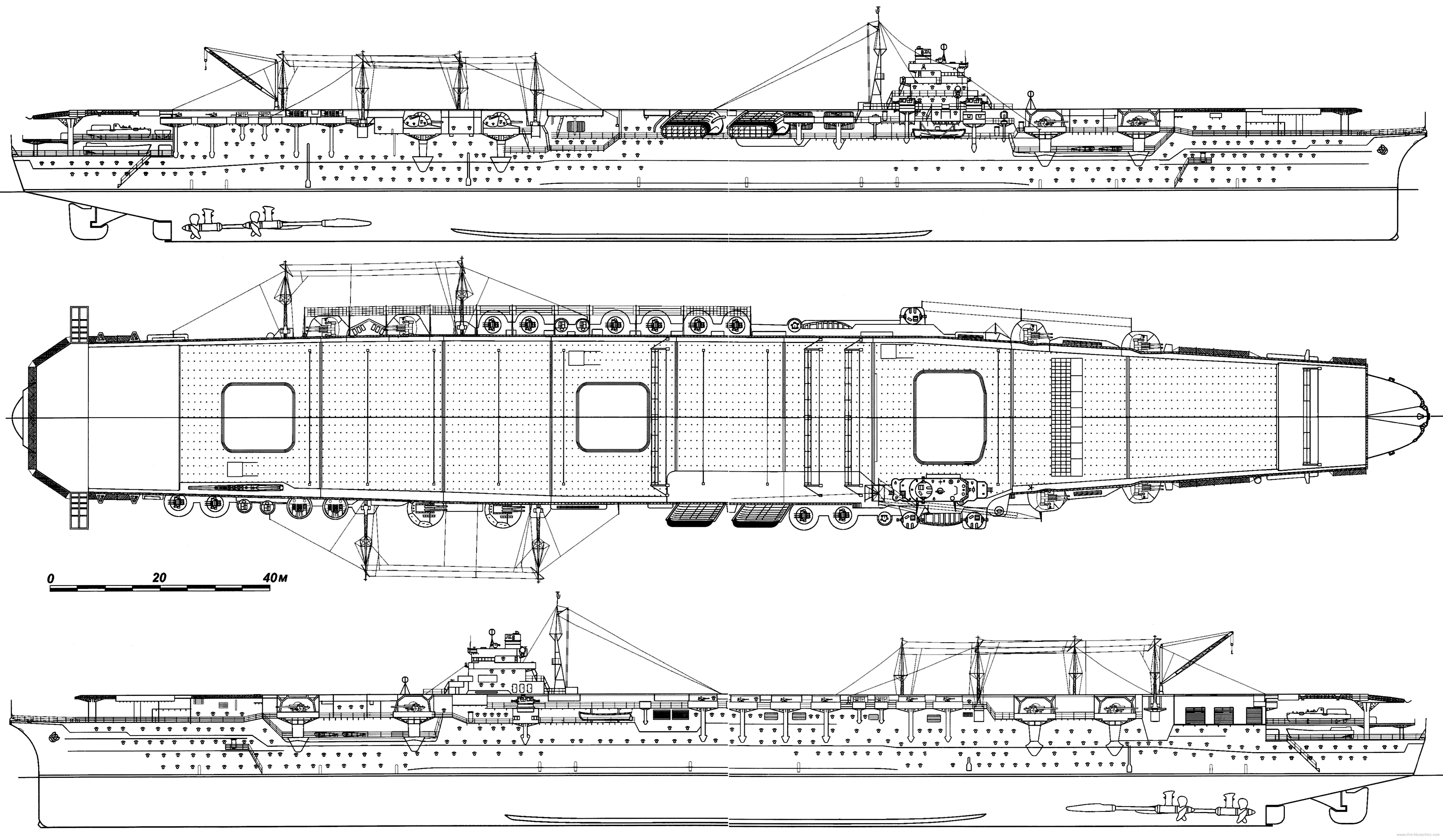

ONI plates of the Shokaku in June 1943

After construction started in December 1937 for the lead ship, the Naval Air Technical Department expressed second thoughts about the location of the island on the port side, tested both on Hiryū and Akagi. Two main reasons were expressed:

- It would have had an adverse impact on airflow, over the flight deck.

- The amidships position shortened the available landing area, problematic in future weight and landing speeds increases

The Naval Air Technical Department wanted to test this, and filmed hundreds of takeoffs and landings aboard IJN Akagi. This was done in October–November 1938, as both ship’s construction was already well underway and many structural elements depended non the decision where to place the island. Eventually they confirmed previous assumptions and decided to move the island to starboard, further forward, at around one-third lenght from the bow.

IJN Shōkaku, which was was the furthest advanced had her island supporting structure already been built and rebuilding it would have delayed construction, so it was simply left in place, whereas the island was moved away as planned. Engineers had to make a one meter (3 ft 3 in) widening of the flight deck stareboard in oder to accomodate the relocated island plus a 50 cm (20 inches) narrowing on the starboard side and 100 metric tons of ballast to compensate on the port side hull bottom to re-balance IJN Shōkaku. This meant the modifications made on her sister ship, built six months later, were minor ones. Those details are the best way to distinguish both ships, not identical twins.

Detailed Design of the Shokaku class

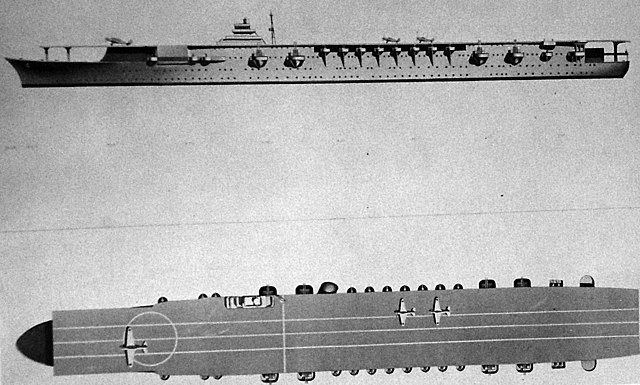

US Intel photo (navsource)

Despite the differences seen above, both ships were twins, with perhaps the tiny differences and details shown by “interpretations” of such complex blueprints by the respective yards, Yokosuka and Kawasaki. They had the exact same 257.5 meters (844 ft 10 in) lenght overall, 29 meters (95 ft 2 in) in width at the largest beam frame, and 9.32 meters (30 ft 7 in) of deep load draught. The moulded depth* (vertical distance measured from the top of the keel to the underside of the upper deck at side) was 23 m (75 ft 6 in). Compared to Hiryu, this was thirty meters longer, eight wider, three draftier, so about 1/5 size increase.

Their displaced 25,675 t. standard and 32,105 metric tons (31,598 long tons) deeply loaded, nearly 2/5 increase compared to Hiryu, or almost a 10,000 tons increase. Hydrodynamic research conducted for the Yamato-class earlier helped the Shōkaku hull to be shaped with a bulbous bow less to increase water penetration than to decrease turbulences and drag, but also twin rudders, on the centerline abaft the propellers. This provided redundancy (smomething well liked in the military) as well as the possibility of harder turns.

Crew as designed was calculated at 1,660 men, with 75 commissioned officers, 56 special-duty officers, 71 warrant officers, and 1,458 crewmen, not counting the air group’s pilots and air officers, machine-gunners/radio, and hangar service personal, for weapons and mechanics. This reflected the number of planes plannes on board, to reach 96, each plane having dedicated personal attached.

Protection

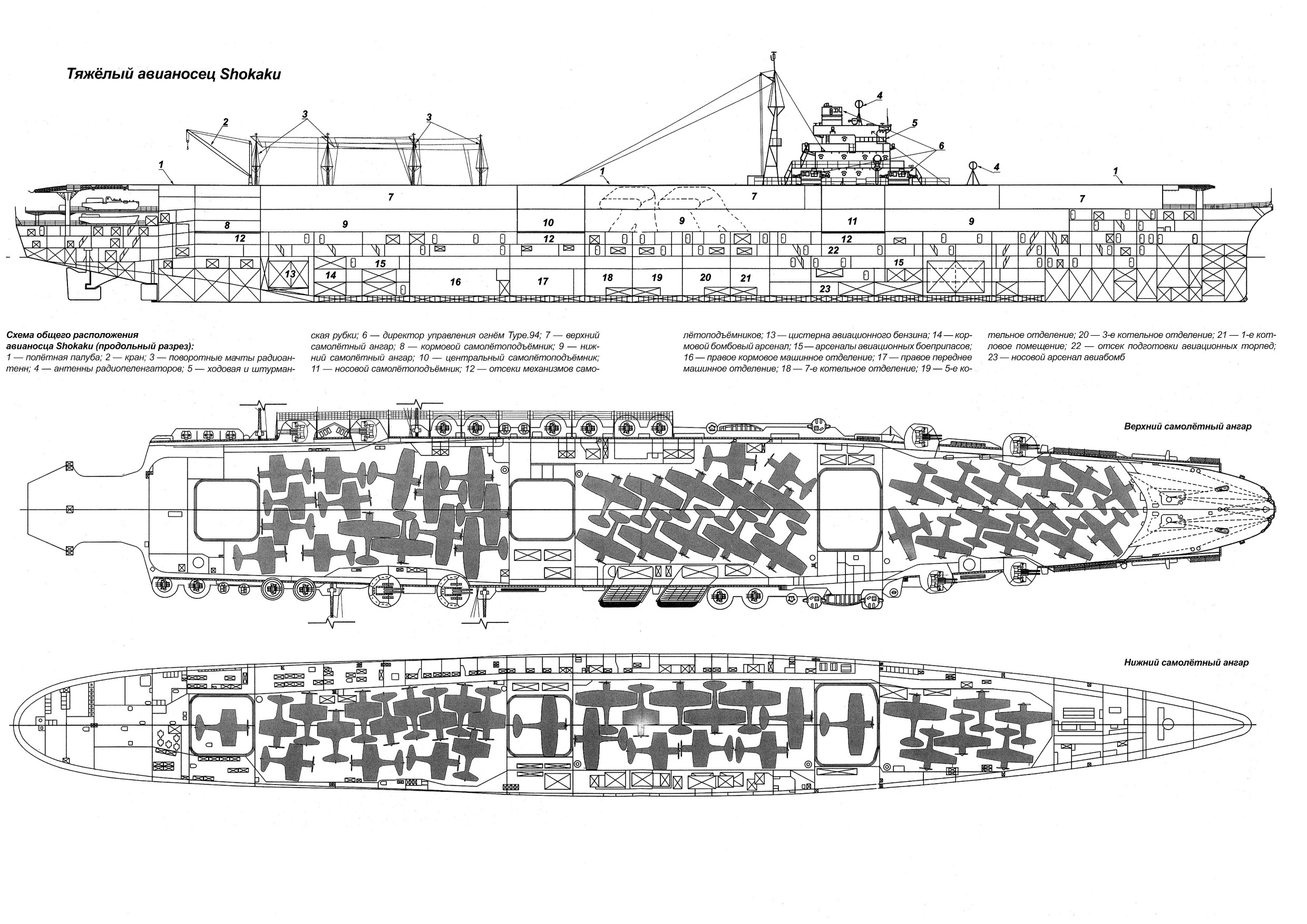

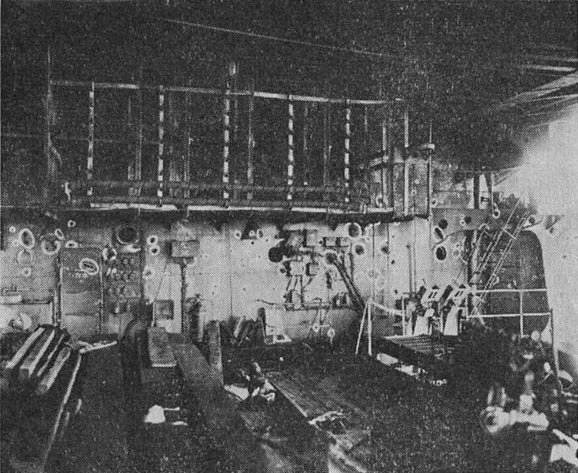

Internal arrangement (Kagero pub.)

An improved passive protection

-The waterline belt was 46 mm (1.8 in) thick only but made of Copper-alloy Non-Cemented armor (CNC) for practically all her hull lenght.

-It was 4.1 meters (13 ft 5 in) high, helf of which (6 ft 7 in) was below the waterline.

-The lower armor strake was backed by 50 mm (2.0 in) of Ducol steel.

-Magazines were protected by 165 millimeters (6.5 in) of New Vickers Non-Cemented (NVNC) armor, sloped at 25°

-These were tapered down to 55–75 mm (2.2–3.0 in).

-The propulsion machinery was protected by a 65 mm (2.6 in) CNC armor.

-Aviation magazines were covered by 132 mm (5.2 in) of NVNC armor.

-Avgas tanks were protected by 105 millimeters (4.1 in).

-Main armored deck (waterline) had a 25-millimeter Ducol steel layer.

-The flight and hangar decks were unprotected

A revolutionary ASW protection

A rather innacurate ONI plate about the Shokaku class

The Shōkakus class innovated in having a proper torpedo belt system behind the belt. These were the product of R&D made in 1935 already. Studies and tests showed that a narrow liquid-loaded compartment could mitigate considerably the blast of a torpedo warhead or a mine, along the torpedo bulkhead. The force was indeed freely distributed along the full width of the bulkhead, and this system aslo stopped splinters.

-They consisted of compartimentatized liquid-loaded “sandwich” arrangement, outboard of the torpedo bulkhead.

-The outboard section was composed of two compartments there to dissipate the gases of the detonation.

-There were also the watertight compartment of the double bottom and innermost compartments could be filled with fuel oil or seawater when consumed underway, acting as ballast as well as anti-mine mine protection.

-The torpedo bulkhead outer Ducol plate were 18–30 millimeters (0.71–1.18 in) thick, riveted to a 12 mm (0.47 in) plate.

In case the torpedo bulkhead was damaged there was a thin holding bulkhead slightly inboard, preventing leaks into inner compartments and crucially, the machinery spaces.

Active protection

Each hangar was subdivided by five or six fire curtains. These could be rapidly extended to cut each hangar section in half, preventing fire spreading. They had no sprinklers but instead foam dispensers on both walls, electrically activated from a remote position.

The lower hangar had a carbon dioxide fire suppression system. The hangar subdivision were supervised by small enclosed armored stations with one operator controlling the fire curtains and fire fighting equipment, even if the hangar was engulfed in flames. Added to these were manual backups in case of an electrical failure. These measures were a first at the time, making the Shokaku class the safest ships in the Imperial Japanese Navy.

Powerplant

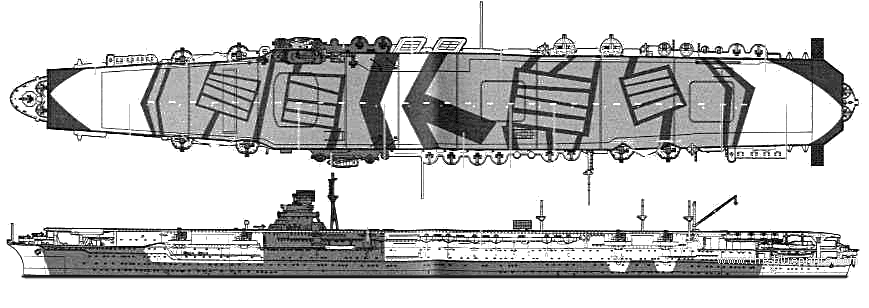

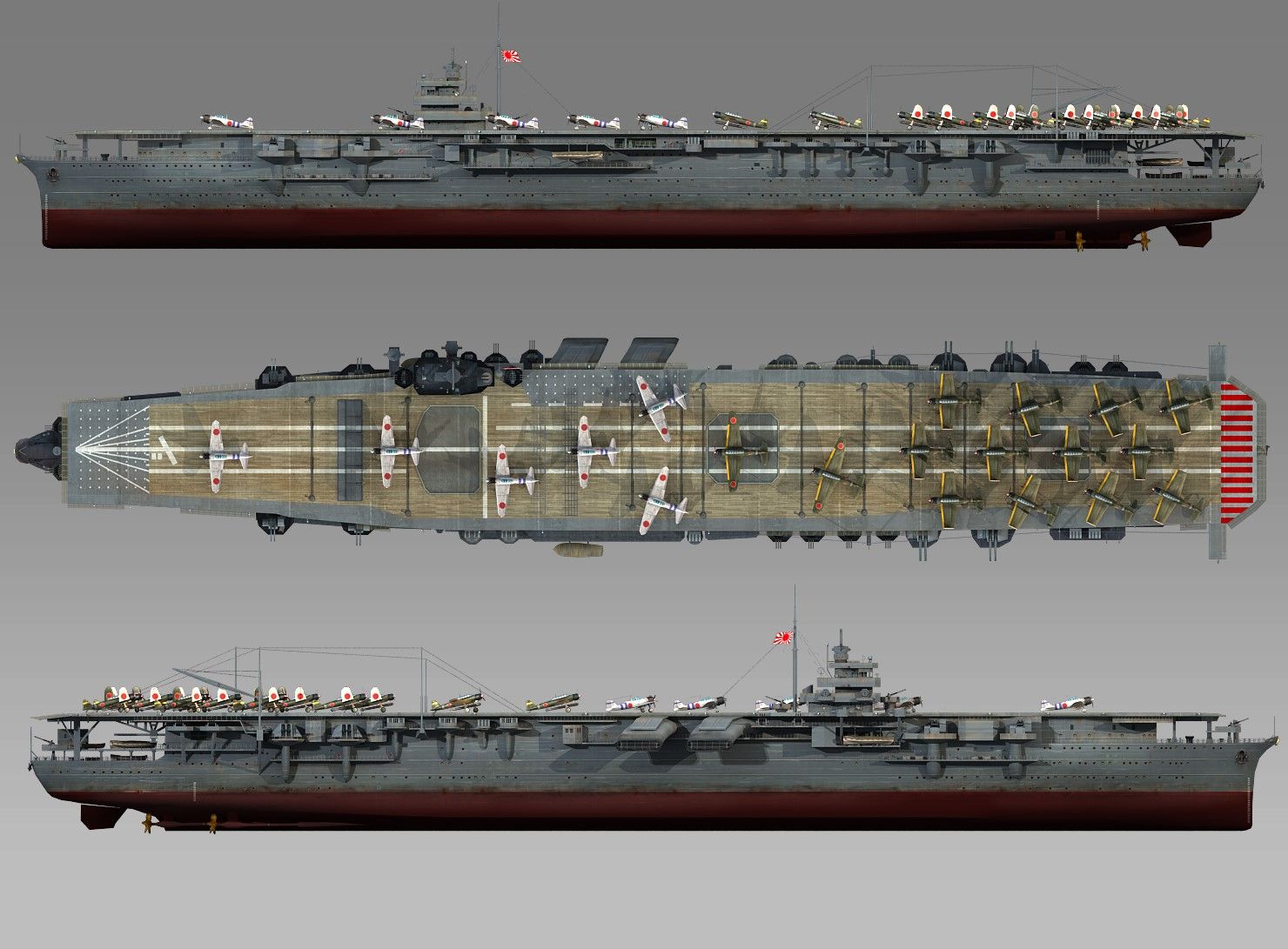

Profile and top of IJN Shokaku in 1941 as commissioned (src navypedia)

The Shōkaku-class powerplant was a modernized and sized-up version of those onboard Hiryu, to reflect their larger scale, but the general design was very close. Engineers calculated the output to reach the same performances given the ship’s larger displacement. The lenght/wifth ratio was less favourable in order to achieve great speed, but this was compensated by a better hull shape.

They had four Kampon geared steam turbine sets, a larger version of what was in Hiryu, which like Soryu derived their powerplant from the Mogami class cruisers. Each turbine drove the same 4.2-meter (13 ft 9 in) propeller. Steam was provided by eight Kampon Type Model B water-tube boilers, with a working pressure of 30 kg/cm2 (2,942 kPa; 427 psi). Total output was 160,000 shaft horsepower (120,000 kW) for a designed speed of 34.5 knots (63.9 km/h; 39.7 mph). This was the same number of turbines and boilers, but they were just scaled-up and refined, notably for the burning efficiency. The ourput was better tha the Hiryu (153,000 shp (114,000 kW)), and still procured a better speed.

Up to that point, this was the most powerful propulsion system ever seen in Japanese service, it ws even more per shaft than the Yamato or even Mogami class cruisers for that matter. Sea trials shown top speed a bit in excess, with 34.37 knots on Shokaku (63.65–64.04 km/h for 161,290 shp, 120,270 KW) and 34.58 knots (39.55–39.79 mph, 168,100 shp, 125,350 kW) on the faster Zuikaku. 5,000 metric tons (4,900 long tons) of fuel oil was carrie din peacetime, enough for a maximal range of 9,700 nautical miles (18,000 km; 11,200 mi) at 18 knots (33 km/h; 21 mph), lss than Hiryu (10,330 nmi/18 knots). Boiler uptakes were trunked in the starboard side amidships, exhausted jbelow flight deck through two equal funnels curving downward as per usual Japanese practice. This changed with wartime carriers. In addition, electrical systems onboard were powered by three 600-kilowatt (800 hp) turbo generators added to two 350-kilowatt (470 hp) diesel generators operating all as the standard 225 volts.

Armament

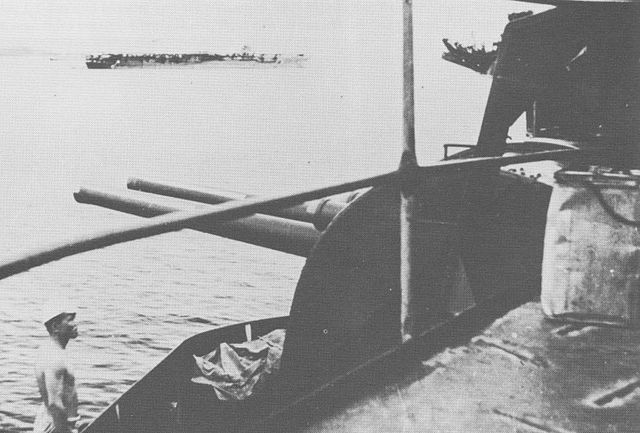

Zuikaku’s sponsons Guns in 1941

Unlike the Akagi-Kagi that inherited casemated secondary guns, the main armament was modern and dual purpose onboar the Shokaku class:

-Eight twin-gun mounts, 12.7-centimeter/40 (5 inches) Type 89 dual-purpose. They were mounted on projecting sponsons in pairs fore and aft on either side.

Their max range against surface targets was 14,700 meters (16,100 yd), with a ceiling of 9,440 meters (30,970 ft) at +90° elevation.

Maximum rate of fire fourteen rounds a minute, down to eight sustained.

-Twelve triple-gun 25 mm/60 (1 in) Type 96 AA guns: Six licenced Hotchkiss mounts on either side of the flight deck. Its speed, loading procedure, flash and smoke, poor optics made it a poor AA mount. It was especially inadequate against high-speed targets and plagued by excessive vibration.

Practical range was between 1,500 and 3,000 meters (1,600–3,300 yd) with a ceiling of 5,500 meters (18,000 ft) at 85°.

Effective rate of fire 110-120 rounds per minute due to the 15-round magazine clips. This number would grow significantly until 1944, notably by the addition of single 25 mm mounts (see later).

Fire control and sensors

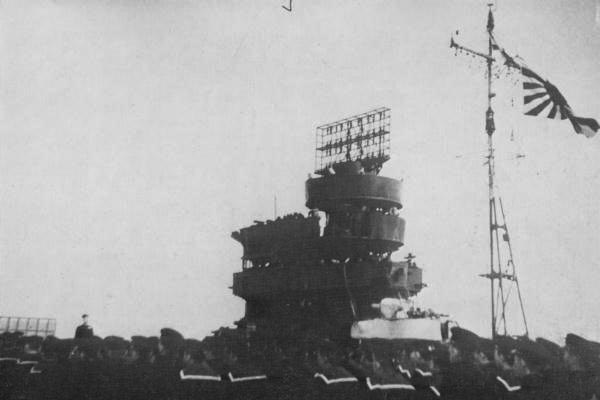

The type 21-Go radar atop the main bridge of Zuikaku in 1944

The class was equipped with four Type 94 fire-control directors to manage the 5-in guns, one decicated for each pair, competed by the island’s director than can overrule them and control all these at once.

The Type 96 guns were controlled by six Type 95 directors: Each one was setup for a pair of triple mounts;

These aircraft carriers were the first to see a radar installed. In June 1942, Shōkaku and Zuikaku receoved extra triple mounts and thus, were given two extra Type 95 director. In October 1942, and before the Battle of the Philippine Sea in June 1944, extra 25 mm were added without control. Zuikaku later, as a surviving ship was in Augtst 1944 concrete-protected aircraft fuel tanks and an additional five twin 25mm/60 Type 96 and twenty-six single of the same plus eight 28-barrel 120mm AA rocket launchers and the Type 3 mod 1 radar.

Aircraft facilities

Blueprint in 1941, click to see in HD (the-blueprints.com)

Both had the same flight deck 242.2-meter (794 ft 7 in) lonf overall, and their flight deck width was 29 meter. Contraty to earlier carriers, the overhung at both ends supported by pillars was short. Deck equipments included ten transverse arrestor wires powerful enough to stop a 4 tons (8,800 lb) aircraft, followed by three crash barricades. There was no aircraft catapults. Indeed, this was planned since it was believed that with the rising weight of new planes and the need of extra space to park, manage launches and recover an air group, the admiralty realized as in western practice, catapults were the future.

However after 1935 there was no way to obtain some from other powers and developed was led in standalone, from scratch. They were desired, but development was not ready as both ships were already in construction and even during refit, not installed. Taiho had no catapult either for the same reason, even the Tatsuragi class or Shinano.

Both were designed with two superimposed hangars as previous vessels, with a 200 meters (656 ft 2 in) long upper hangar, between 18.5 and 24 meters (60 ft 8 in and 78 ft 9 in) wide and 4.85 meters (15 ft 11 in) high. The lower hangar was just 4.7 meters (15 ft 5 in) high to park fighters only and 20 meters (65 ft 7 in) shorter while also narrower at 17.5-20 meters (57 ft 5 in to 65 ft 7 in). Combined parking area was 5,545 square meters (59,690 sq ft) and subdivided by six (main hangar) and five (second hangar) sections for safety.

Another detailed blueprint view in 1941

Aircraft service depended on three elevators doing a two level rise within 15 seconds. The forward elevator was tailored for fast recovery, for aicraft just landed with wings unfolded and measured 13 by 16 meters (42 ft 8 in × 52 ft 6 in) while the two others were narrower both 13 by 12 meters (42 ft 8 in × 39 ft 4 in). A crane was also installed on the starboard side of the flight deck close to the rear elevator and disappeared when collapsed. It was used to recuperate floatplanes or splashed planes.

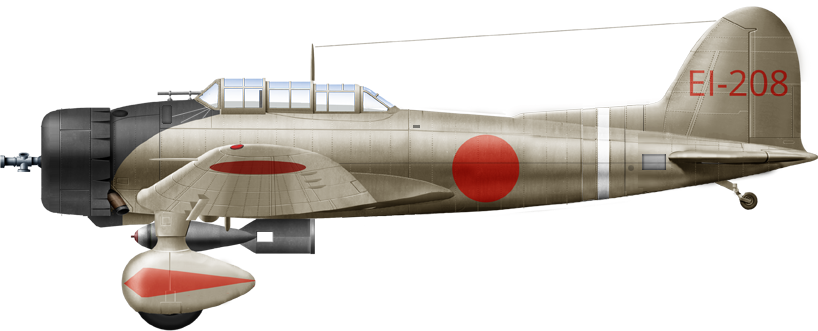

Onboard aviation

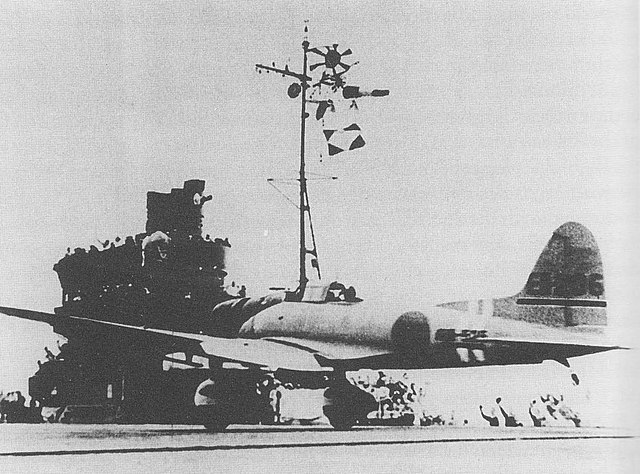

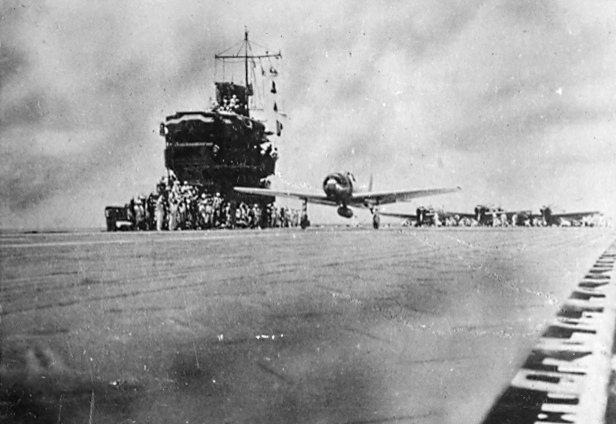

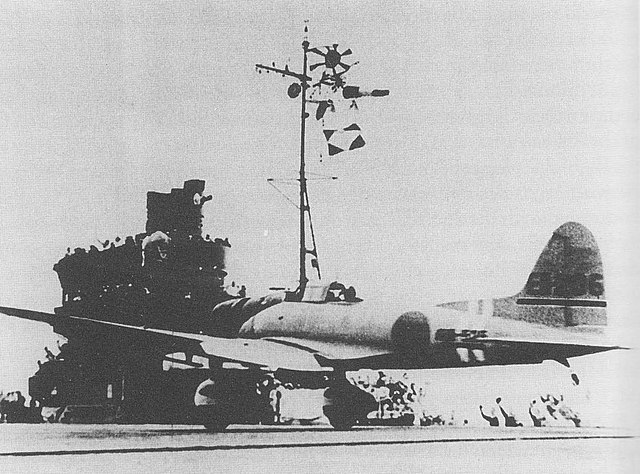

A “Val” taking off from Zuikaku during the battle of the Coral Sea

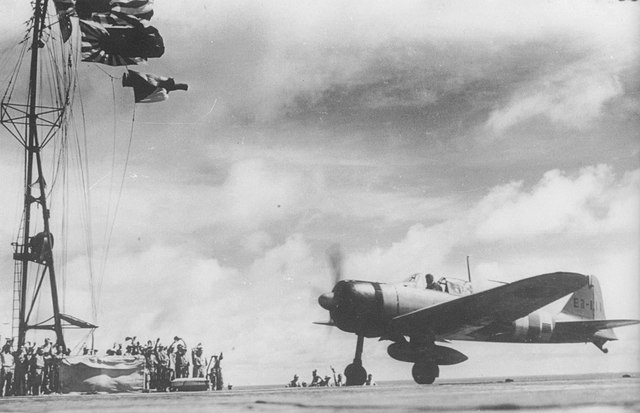

A Zero taking off from Zuikaku in December 1941

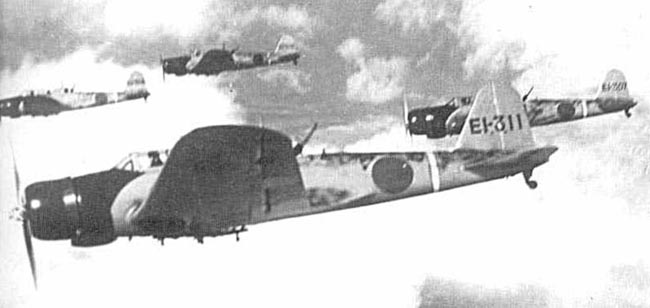

The Shōkaku-class aircraft carriers initial air group as designed in 1937 was 96 total, the same as Akagi, and included 24 aircraft in reserve. At first these were 12 Mitsubishi A5M (“Claude”) fighters, 24 biplanes Aichi D1A2 (“Susie”) dive bombers, 24 Mitsubishi B5M (“Mabel”) torpedo bombers, and 12 Nakajima C3N reconnaissance aircraft. This air park as designed was obsolete before completion despite having transitional fixed undercarriage monoplanes. The C3N eventually was cancelled after just two prototypes being built. They were commissioned in August-September 1941 with a renewed park and apart the “Val” which still had fixed undercarriage, the others were second generation monoplanes with retractable undercarriages.

More modern aircraft were re-planned before completion, and in service both carriers adopted 18 Mitsubishi A6M Zero fighters, 27 Aichi D3A (“Val”) dive bombers, and 27 Nakajima B5N (“Kate”) torpedo bombers, which became the standard trinity of all IJN carriers until 1943-44. There were in addition as usual spare planes, two Zeros, five “Vals”, and five “Kates” making for a grand total of 84 aircraft of which 72 were active. It was less than the 90 operational onboard the Yorktown class, and the repartition between fighters and strike aicrafts reflected the Japanese doctrine at the time, which prevented to mount a large CAP as half were already deployed as escorts during strikes (nine in CAP, nine in escort).

-The Mitsubishi A6M2 “Zeke” (1940) arrived just in time, to be precise, the A6M2, for Pearl Harbor. The mainstay of the carrier, replaced with the A6M3 possibly in December 1942 and the A6M5 in 1944.

–The Aichi D3A1 “Val” (1938) was also adopted in 1941, replaced by the D3A2 in late 1942 and until the battle of Leyte.

-The Nakajima B5N2 “Kate” (1937) was one, if not the most modern torpedo plane in 1938, better than the Vought Devastator. The B5N1 was no longer in service in 1941, they operated the B5N2 from pearl Harbor to Midway, and until the fall of Guadalcanal. They were replaced in the summer of 1943 by the B6N.

In early 1944, the air group was revised to comprise 26 B7A “Grace”, 24 Yokosuka D4Y “Judy”, and the rest of Mitsubishi A6M5s*.

Fighter pilots posing in 1941, before the attack.

A6M taking off from Shokaku in December 1941

Same.

A flight of B5Ns (Type 94) from IJN Shokaku in 1943

Wartime modifications

Profile in 1944, showing its early camouflage

Zuikaku camouflaged in a seocnd version of the same, wth green tones, in October 1944 at the battle, of Leyte, showing her extra armament

In late 1942, both ships were given four additional triple 25mm/60 model 96, and a model 1 2-go radar: Two were installed at the bow and stern, one each fore and aft of the island. In July 1943, both ships received again two extra triple 25mm/60 (So now eighteen triple mounts) plus eixteen single, grand total 72. In August 1944, surviving Zuikaku had her aircraft fuel tanks receiving additional concrete protection. In addition she received five twin 25mm/60 Type 96, plus 26 extra 25mm/60, and eight 28-tubes 120mm (5 inches) AA Rocket Launchers and the new Type 3 1-go radar. Her total AA at this point before October 1944 was 113 Type 96 25 mm AA in triple, twin and single points, the latter installed directly on the flight deck and removed for air operations.

The Rocket launchers, inspired by British practice, were 120 mm (4.7 in), 22.5 kgs (50 lb) models with a maximum velocity of 200 m/s (660 ft/s) and range 4,800 meters (5,200 yd). They lacked a proximity fuse and thus, their efficiency was questionable.

About the names

IJN Shokaku after launch.

Shōkaku meant “Soaring Crane” (翔鶴) and Zuikaku meant “Auspicious” or “Happy” Crane (瑞鶴). Both used old formulae at that, and were both poetic and majestic in their formulation. These names would be unthinkable in Western culture as “unmanly” and lacking inspirational patriotic values. However, they were at the very essence of Japanese culture. A pattern developed, notably with destroyers, all named after winds (“-kaze”), which in that case mirrored French practice. But interwar conventions gave them names related to weather, tide, current, wave, moon, season, other natural phenomenon in general. Second class destroyers built in wartime were given mostly botanic names, like “Cherry”, “Bamboo”, “Wisteria”, “Pine”, “Plum Blossom” or “Willow”, not unlike British ASW corvettes and frigates, named after flowers, lakes, lochs, or hunting lodges.

But for capital ships it went back to when the navy was just created and the Ministry of the Navy submitted potential ship names to the Emperor for approval. These were often donated by the Shogunate or Japanese clans and many times, original clan names were kept. In 1895 the Minister of the Navy proposed a standard for battleships and cruisers, to be named after provinces or shrines dedicated to the protection of Japan, and for others (most important) would be selected among poetic versions of Japan itself (Like Yamato) or its provinces, the latter mirroring notably more Western Practice. There was another reform in 1905, and in 1919, this was changed again, alongside a massive naval construction program.

Battleships had been generally named after provinces and cruisers after mountains/volcanoes, but aircraft carriers, due to their very role, were given special names inherited from the ships in the Bakumatsu and the Meiji period, related to flying animals, either real or mythological. Therefore, the Shokaku class were the only cranes in the IJN, Phoenix, Dragons, and interestingly enough, less nobles ones like WW2 Converted merchant ship received the initial Taka (Yō) (鷹, falcon/hawk) after her name, like in Jun’yō (隼鷹) (“Peregrine falcon”).

Author’s illustration of IJN Shokaku in December 1941

⚙ Specs 1941 |

|

| Dimensions | 257,50 m long, 26 m wide, 8,87 m draft |

| Displacement | 25,675 t. standard -32 100 t. Full Load |

| Propulsion | 4 steam turbines, 8 boilers, 160,000 hp. |

| Speed | 34.2 knots (65 km/h; 41 mph) |

| Range | 7,750 nmi (14,350 km; 8,920 mi) at 18 knots (33 kph, 21 mph) |

| Armor | Belt 70mm, stores 130-165mm, machinery deck 100 mm |

| Armament | 16 x 127 AA, 42 x 25 mm AA, 84 aircraft |

| Crew | 1660 |

Japanese aircraft carrier Shokaku in 1942

Sources/ Read more

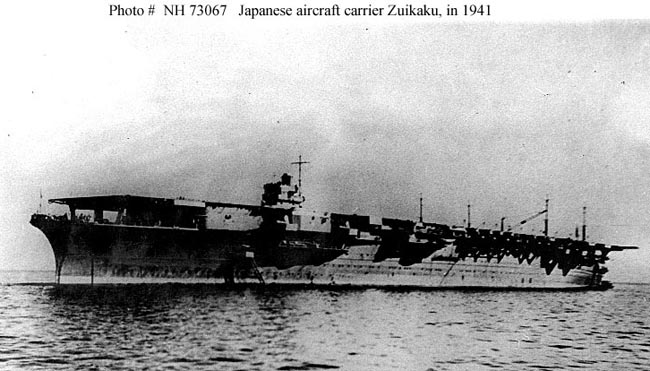

Zuikaku in Bungo channel, October 1941

Books

Conway’s all the worlds fighting ships 1922-1947

IJN AIRCRAFT CARRIER SHOKAKU-CLASS, PICTORIAL BOOK, GAKKEN REKISHI-GUNZO #13

Bōeichō Bōei Kenshūjo (1967), Senshi Sōsho Hawai Sakusen. Tokyo: Asagumo Shimbunsha.

Brown, David (1977). WWII Fact Files: Aircraft Carriers. Arco Publishing.

Chesneau, Roger (1998). Aircraft Carriers of the World, 1914 to the Present. Brockhampton Press.

Dickson, W. David (1977). “Fighting Flat-tops: The Shokakus”. Warship International.

Dull, Paul S. (1978). A Battle History of the Imperial Japanese Navy (1941–1945). Naval Institute Press.

Hammel, Eric (1987). Guadalcanal: The Carrier Battles. Crown Publishers, Inc.

Jentschura, Hansgeorg; Jung, Dieter & Mickel, Peter (1977). Warships of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1869–1945. Annapolis

Lengerer, Hans (2014). “The Aircraft Carriers of the Shōkaku Class”. Warship 2015 Conway

Lundstrom, John B. (2005a). The First Team: Pacific Naval Air Combat from Pearl Harbor to Midway

Lundstrom, John B. (2005b). The First Team and the Guadalcanal Campaign. Annapolis

Peattie, Mark (2001). Sunburst: The Rise of Japanese Naval Air Power 1909–1941. Annapolis

Polmar, Norman & Genda, Minoru (2006). Aircraft Carriers: A History of Carrier Aviation and Its Influence on World Events

Rohwer, Jürgen (2005). Chronology of the War at Sea 1939–1945: The Naval History of World War Two (Third Revised ed.).

Shores, Christopher; Cull, Brian & Izawa, Yasuho (1992). Bloody Shambles. I: The Drift to War to the Fall of Singapore.

Shores, Christopher; Cull, Brian & Izawa, Yasuho (1993). Bloody Shambles. II: The Defence of Sumatra to the Fall of Burma.

Stille, Mark (2009). The Coral Sea 1942: The First Carrier Battle. Campaign. 214. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing.

Stille, Mark (2011). Tora! Tora! Tora:! Pearl Harbor 1941. Raid. 26. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing.

Stille, Mark (2007). USN Carriers vs IJN Carriers: The Pacific 1942. Duel. 6. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing.

Zimm, Alan D. (2011). Attack on Pearl Harbor: Strategy, Combat, Myths, Deceptions. Havertown, Pennsylvania: Casemate Publishers

Links

Zuikaku in 1941 (cc)

Zuikaku in 1944 (cc)

Tully, Anthony P. (30 July 2010). Shokaku Tabular Record of Movement”.

Tully, Anthony P. (30 July 2010). Zuikaku Tabular Record of Movement”.

The Sinking of Shokaku, An Analysis By Anthony Tully, Jon Parshall and Richard Wolff

3D

A nice rendition in color and 3d (wargaming)

Rendering from World of Warships.

Videos

Shokaku vs Yorktown Class Carriers, Military History Visualized

Shōkaku and Cavalla, a Confrontation of the WWII Pacific Theater – THG

Efficence of IJN VCs in Military History Visualized

The sinking of Shokaku on HR Naval Museum

The model’s corner

A model of Zuikaku in her 1944 Leyte battle livery (cc) – 1/700 Michimo kit

General query On scalemates – zuikaku

IJN Shokaku’s career

Shokaku in 1941

IJN Shōkaku and Zuikaku, commissioned with little interval, formed the Japanese 5th Carrier Division, last of the Kido Butai. They embarked their aircraft shortly before leaving for the Pearl Harbor attack (18 A6M2 “Zero”, 27 Aichi D3A1 “Val”, 27 Nakajima B5N1/B5N2 “Kate”).

Prewar Activity

According to detailed logs, IJN Shōkaku on 15 October 1940 saw Captain Jojima Takatsugu appointed the Chief Equipping Officer during the completion of the aircraft carrier. On 15 November 1940, Captain Takatsugu also served on IJN Tsurugizaki, future light carrier IJN SHOHO under conversion from seaplane tender to aircraft carrier. This dual role was common at the time for completed ships. On 8 August 1941, as Shokaku was Commissioned at Yokosuka, she was assigned as Special Duty Ship and Jojima Takatsugu became now her first full time Commanding Officer. The ship was fitting out and attached to Kure Naval District and she departed on 23 August 1941 Yokosuka for her shakedown cruiser, sailing to Ariake Bay in Kyushu. Two days later on arrival she becomes flagship of 1st Air Fleet (Kidu Butai) assigned to CarDiv 5 (Carrier Division 5). On 1st September 1941 IJN KASUGA MARU (future TAIYO) is joined to CarDiv 5 and five days later, she departs for Yokosuka, and the commander of the First Air Fleet leaves the ship.

However, Shokaku was quicky reinstated, on 10 September 1941 as flagship of ComCarDiv 5, remaining in Yokosuka until 4 October 1941 when she departs for exercizes in Oita Bay and was back in Kure naval arsenal on 8 October 1941 to join her new sister-carrier ZUIKAKU, now ready for service. Both spent the rest of October making rotations between Kure, Oita, and Saeki area, drilling. On the 12 of October in Saeki Bay, then Sukumo Bay, Terajima Strait and on 28 October in Sasebo. On 10 November CarDiv 5 was in Kure, preparing for next offensive operations now fully planned and detailed. On 14 November 1941 Shokaku lost her flagship role to ZUIKAKU.

On 17 November 1941 she departs Kure for Saeki Bay, then Oita Bay and sailed into the Inland Sea with ZUIKAKU, bound for Hittokappu Bay (Etorofu Island, Kuriles) joining the rest of Kido Butai for “Hawaii Operation”. They reach their destination on 22 November 1941, last-minute addition to the Carrier Striking Force and on 26 November Vice Admiral M. Chuichi Nagumo’s First Air Fleet departs Hittokappu Bay, taking an unusued route in total radio silence for the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Pearl Harbor Attack

Commanding Officer on IJN Shokaku watches as planes takes off to attack Pearl Harbor

Air officers posing after the attack.

When CarDiv 5 departed, the fleet also comprised CarDiv 1 (AKAGI, KAGA), CarDiv 2 (HIRYU, SORYU), BatDiv 3 (HIEI, KIRISHIMA), CruDiv 8 (TONE, CHIKUMA), DesRon 1 (ABUKUMA) escorted and screened by Desdiv 17 (ISOKAZE, URAKAZE, TANIKAZE, HAMAKAZE) and DesDiv 18 (ARARE, KAGERO, and SHIRANUHI). At the time of the atack, each carrier’s aircraft complement consisted of 18 Mitsubishi A6M2 “Zero” fighters, 27 Aichi D3A1 “Val” dive bombers, and 27 Nakajima B5N1 or B5N2 “Kate” torpedo bombers.

On the 8 December 06:00, Dec 7th local date she launched a first strike composed of 26 “Val” dive-bombers led by Lt.Cdr. Takahashi Kakuichi escorted by 5 “Zeke” fighters (Lt. Kaneko Tadashi) loosing one dive bomber during the attack. The second strike is launched at 07:15 local time, with 27 “Kate” torpedo planes, armed with bombs (Lt. Tatsuo Ichihara), returning without loss. No third wave was launched and Nagumo retitred. It’s dificult to poinpoint particular sinkings attibuted to her air group.

Attack on Rabaul (January 1942)

The Kido Butai was split after return in home waters, CarDiv 2 (Hiryu-Soryu) detached to attack Wake Island while the rest stayed in Hashirajima on 23 December 1941 and two days later, CarDiv 5 sailed to Kure Naval Base, after a stopover at Saeki. She ws drydocked and spent the new year here undocked on 3 January 1942, before heading to Hiroshima Bay, in company with Zuikaku. On 7 January 1942, both departed for Truk with Nagumo’s main Striking Force and departed again on 16 January 1942 to take part in “R” Operations (14th-24th). On 20 January 1942 a massive first strike of 90 planes combined was launched against Rabaul, Shkaku contributed to 19 “Val” dive-bombers and retirung without loss.

On 21 January 1942, CarDiv 5 was detached with IJN Chikuma and four destroyers to launch separate raids on airfields in New Guinea, notably Lae, Salamaua, Bulolo, and Madang. On the 25th, about 100 miles south of Truk, Shokaku embarked sixteen Mitsubishi A5M “Claude” fighters from Chitose destined to fill a local reclaimed airfield at Rabaul before proceeding to Truk, arriving on the 29, while on the 30th, Shokaku departed for Yokosuka. There, she picked-up aircraft from the homeland while Zuikaku followed the Kidu Butai’s CarDiv 1 (AKAGI and KAGA) in pursuit of USN carrier force raiding the Marshall Islands.

Indian Ocean raid (March–April 1942)

Nothing much happened for Shokaku in February. On the 3th she was in Yokosuka, training in local waters and alternating to Tateyama Bay (11th), Shirako Bay, Mikawa Bay until the 24th, and back to Yokosuka to be drydocked on the 247th until 5 March 1942. She departed two days later to intercept VADM W.F. Halsey’s TF 16 (USS ENTERPRISE) after the Marcus Island raid, but in vain as he was not located. On 11 March she joined ZUIKAKU, under Vice-Admiral Shiro Takasu’s ISE (flagship) and HYUGA’s task force, for a sortie to intercept a incoming force approaching the homeland. But no contact is made and the force folds up on 16 March 1942 to Yokosuka, departing a day later for Staring Bay, to join “C” Operations, arrving there on the 24th with the destroyers IJN Arare, Kagero, and Akigumo.

Two days later, the First Air Fleet sailed out, with CarDiv 5, 1 and 2 less some ships (Akagi, Hiryu, Soryu, zuikku, escorted by the fast battleships of the Kongo class and the cruisers Tone, Chikuma and Abukuma plus eleven destroyers of Desdiv 4, 17, 18 and the fleet oiler SHINKOKU MARU. On 3 April 1942 this strike force entered the Indian Ocean and on the 5th, launched a first strike against Colombo. Two ships were sunk and support facilities badly damaged. Later en route for a second objective, two Royal Navy heavy cruisers, HMS Cornwall and Dorsetshire were spotted and sank as well as HMS Hermes on 9 April off Batticaloa.

That same day, Shokaku launched strike (18 “Kate”) tescorted by ten Zero fighers, over Trincomalee in Ceylon. She lost one fighter, but shipping was ransacked and port infrastructure destroyed. 18 “Val” dive bombers meanwhile sank the Hermese, her onw air group claiming 13 hits out of the 40 reported.

Battle of the Coral Sea (8 May 1942)

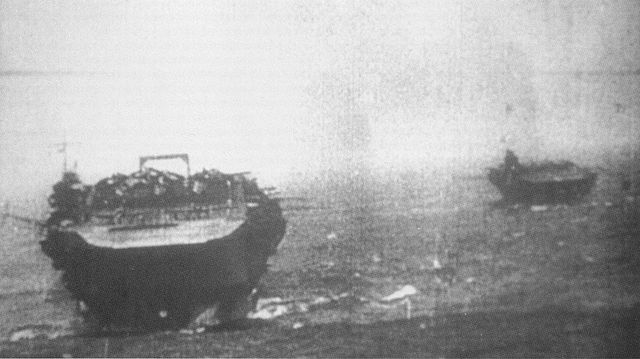

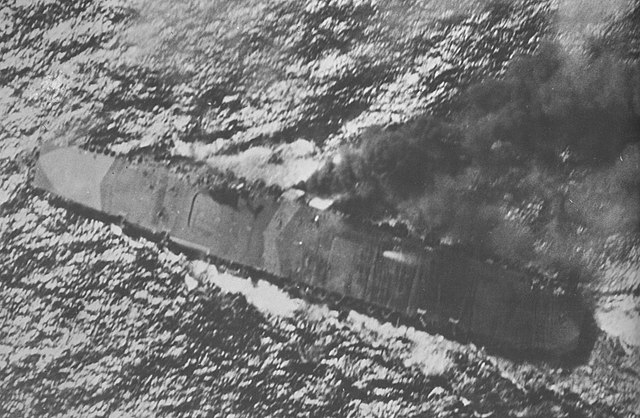

Shokaku under attack, 8 May 1942

After the Indian Ocean, the Kido Butai was back on 18 April 1942 via Formosa, when CarDiv 4 was detached, with as escort the destroyers IJN Hagikaze and Maikaze, to Mako, to resupply, embark provisions, and departs to participate in Operation “MO”, the invasion of Port Moresby in New Guinea, scheduled for 10 May, with an official start on 20 April. At arrival they were escorted by Desdiv 27 and on the 25 April 1942, they arrived in Truk.

The Fifth Carrier Division departed on 1st May 1942 with a force under overall command of Vice Admiral Takeo Takagi (flagship MYOKO), screened by IJN HAGURO and CarDiv 5 (Hara Chuichi) plus six destroyers of Desdiv 27 and 7 plus the fleet oiler TOHO MARU.

Their goal was to neutralize Australian air bases then cover the invasion convoy. Takagi was warned of the possible presence of US carriers also, but none were expected until CarDiv 5 entered the center of the Coral Sea.

On May, 7, at 06:10 reaching a position about 300 miles southwest of Tulagi, with 05:22 and 05:45 reported of enemy ships south of their position had V.Admiral Hara ordering a full strike launched from both CarDiv 5 carriers: 36 “Val” and 24 “Kate” escorted by 18 Zeros (Lt.Cdr. Takahashi Kikuichi), just underway when at 06:20 cruiser’s search planes received reports of enemy carriers south of Rossel Island. This was only known at 07:00 to Hara, not a position to launch yet mainly for logistical reasons.

At 09:15 after for two hours, the air strike only saw and sank a lone fleet oiler, Lt.Cdr. Takahashi realizing his course since the beginning was wrong or the report of a “carrier and cruiser” totally false. Resigned, her stays in the area with the dive-bombers, sending back the torpedo planes. At 09:26 he spotted and sank the destoyer USS Sims while abdly damaging the fleet oiler USS Neosho, left dead into the water. Meanwhile Fletcher (TF 17, USS Lexington, Yoktown) acted based on a mistaken report of Japanese Louisiades invasion.

They launched at 07:25 and on their way to a false flag by sheer luck, Lexington’s air group spotted Goto Aritomo’s Covering Force covered by IJN Shoho, sank at 09:35. Fletcher also detached a 3 cruiser, 3 destroyer force (British Admiral J.C. Crace) beating off combined air attacks at Rabaul and Buna, to the point Port Moresby invasion operation was suspended. Soon, both Japanese and American carrier forces prepared for a grand action at 14:30 CarDiv 5 launching, but knowing they would return at nightfall, selecting their most night flying skilled pilots.

In all, 12 “Val” and 15 “Kate” flew at the very limit of their operational radius after twilight, but to find nothing and fall back, having at that point overflown TF 17, but still intercepted by their CAP. Disoriented pilots (including from Shokaku) tried to land on USS Yorktown, greeted by AA fire. Admiral Hara ordered CarDiv 5’s searchlights on to help pilots, many splashing, out of fuel. Six were recuperated intact.

IJN Shōkaku’s air group meanwhile found and sank USS Lexington but she was in turn attacked on 8 May 1942 by Dauntlesses from USS Yorktown and Lexington and suffered three bomb hits at the port bow, starboard and abaft the island. Damage teams however contained and extinguished all fires but the aicraft carrier had to return to Japan for repairs.

On her way back, chased by many US ships under the codename “Wounded Bear”, the aircraft carrier maintained full speed to avoid submarines, her damage prow let enter so much water these started to list by the prow, and when encountering heavy seas, nearly capsized. She was spotted by USS TRITON, and missed by USS POLLACK. She eventually reached Kure on 17 May 1942, drydocked on 16 June 1942, repaired ten days bu she still needed two weeks later, until 14 July, to train new pilots, which left her and Zuikaku out of the fatidic Midway battle. She was reassigned in July to the 3rd Fleet, Carrier Division 1, Kido Butai being now deprived of more than half its power. In between, on 25 May 1942, Captain Jojima was relieved by Captain Masafumi Arima.

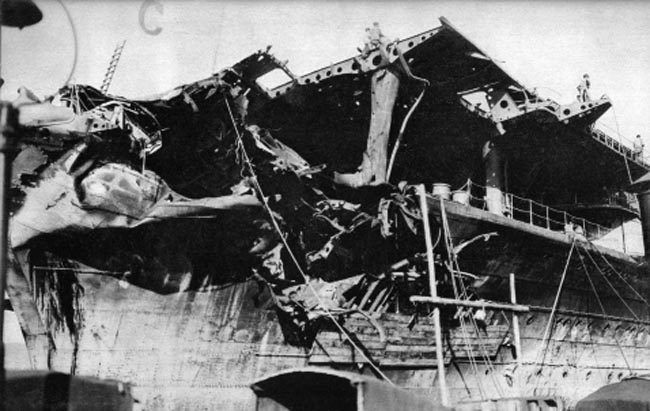

Battle damage after Coral Sea

Eastern Solomons campaign (Summer to late 1942)

Shōkaku and Zuikaku, teamed with IJN Zuihō, as the First Carrier Division, taking part in the Battle of the Eastern Solomons, and the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands, claiming Enteprise and Hornet. Here’s how it unfolded: On 18 July 1942, IJN Shokaku departed Kure for Hashirajima anchorage and started a training cruise from the 21 to the 31. After a stop in Hashirajima and kure, she rejoined her sister-ship in Hashirajima, before beiong assigned on 16 August to the Striking Force, 3rd Fleet, CarDiv 1. under command of Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo, departing to support the ground offensive on Guadalcanal, under occupation by the Marines since August 7 as well as intedicting the arrival of US carriers and further reinforcements.

In addition to the two carriers, the 3rd fleet comprised the aircraft carrier IJN RYUJO, the 11th battleship division (HIEI, KIRISHIMA), the 7th cruiser division (KUMANO and SUZUYA) and 8th (TONE, CHIKUMA, NAGARA) plus destroyers from Desdiv 10 and 16 (9 in all).

On 21 August 1942, the fleet refuelled at sea from oilers to head directly toward Guadalcanal, RDV with Kondo’s Advanced Force, and divided to reach assigned positions, drawing out into battle the three TF-61 carriers of Admiral Fletcher located southeast of Guadalcanal. The rest were to cover three troopships bound for Guadalcanal escorted by the cruiser IJN JINTSU. On the 25th, at 07:50 this convoy was spotted by a Catalina, so Tanaka urged the carriers for air cover.

Nagumo however wanted his forces held in reserve and keep its position secret, but agreed to launch if no American carriers were on August 24 as protection was due to the convoy anyway. At 16:25 Nagumo ordered the Kido Butai to retire north for the night and on the 24th at 02:00 since no US carriers was sighted, Nagumo sent Ryujo and Tone, plus two destroyers (Hara Chuichi, flagship Tone) to a south foray and joined direct support operations. At 04:15 CarDiv 1 after joing the ideal position, launches 19 “Kate” tasked of searching the US force, augmented by 7 seaplanes from the four cruisers while a standby ready strike was prepared wil all the “Val” available and extra “Kate” prepared and held in reserve for second strikes.

At 12:50 Chikuma’s seaplane reported TF-61’s carriers (Saratoga, Enteprise) and TF-18 (Wasp) back from refuelling the day before. Shokaku and her sister ship launched a strike based on estimate of their location, the 18 “Val” escorted by four Zeros (Lt.Cdr. Seki Mamoru) joining the air group from ZUIKAKU.

But underway, at 13:15 Shokak is truck by the dive-bombed from USS ENTERPRISE, spotted before by the new radar, sending a warning but not received in time. Lookouts spotted them at the last minute, prompring Captain Arima to make a full hard rudder turn to port, evading the bombs, but shakened by very near-misses on the starboard side, killing six. Her captain scrambled her last 11 fighters. Then it became quiet until both aocraft carriers launched their second strike at 14:00, including 9 “vals” for SHOKAKU with 3 Zeros (Lt. Takahashi Sadamu).

At 14:40 they fell on the US carriers. Due to confusion they all attacked only USS ENTERPRISE, having three bomb hits while all torpedoes missed. Due to superior AA on the US side, the Japanese lost a staggering total of 18 “Val” dive-bombers and 6 fighters, more than half the strike force, many of which were dealt for by the new FCS-assisted 5in/38 onboard USS NORTH CAROLINA. At 16:30 CarDiv 1’s second strike failed to locate the USS ENTERPRISE or SARATOGA due to a incorrect previous report.

Out of reach, the planes tried to reach back CarDiv 1 to land after sunset. Nagumo ordered all searchlights turned on, but just five “Val” returned, the crew of one more rescued. Nagumo then ordered awithdrawal in order to refuel, thinking the action was won. Shokauku lost in all 10 “Val” and 5 fighters. In reality the Battle of Eastern Solomons was a Japanese tactical defeat and after the loss of RYUJO Tanaka’s convoy lost its flagship JINTSU, cancelling the planned reinforcement, to the relief of the beleaguered Marines in Guadalcanal.

Battle of Santa Cruz Islands (26 October 1942)

Aircraft prepare to launch from Shokaku at Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands

The third major test of CarDiv 1 was at Santa Cruz on 26 October 1942. Well Before this, IJN Shokaku sailed on 28 August 1942 to Kavieng, leaving there its remaining air group until 4 September. She was reassigned to Support force, of the 3rd Fleet in Truk. On 10 September 1942 she departed Truk with Second and Third Fleets, heading north of Guadalcanal for support, but after failing to make contact, the force withdrawn on 23 September 1942 back to Truk. On 11 October 1942, the aircraft carrier became flagship of Nagumo and of the Third Fleet (CarDiv 1 also comprised IJN Zuiho and the cruiser Kumano and DesDiv 16, 4, ten destroyers.

Departing Truk for an extended sortie, the mission was to cover a large reinforcement convoy to Guadalcanal and then cover a major ground operation to recaptured Henderson Field. This “Support Force” was under command of Vice admiral Nobutake kondo, flagship IJN ATAGO, CarDiv 2 (JUNYO and HIYO) and Nagumo’s Kido Butai’s CarDiv 1. Operating 100 miles ahead of Nagumo was Hiroaki’s force from flagship HIEI. They were to take a station northeast of the Solomons, north of the Santa Cruz Islands.

On 15 October 1942 at 09:37, receiving a reported U.S. convoy east of Guadalcanal, Shokaku launched a 8 Zero strike, escorting 21 “Val”, soon joined to 9 “Kate” from Zuikaku and thery fell at 10:25 on their prey, sinking USS Meredith and the feet tug USS Viero towing a gasoline barge. One “Val” was shot down. On the 25th, CinC Yamamoto (flagship YAMATO in Truk) informed Nagumo that a CV force was supposed coming to an area northeast of the Solomons (TF-16, USS Enteprise and TF 17 Hornet, Thomas Kinkaid) ordered by Halsey to conduct a sweep across the Santa Cruz Islands and Coral Sea.

Long story short, Shōkaku was seriously damaged, taking three (possibly even six) 1,000-lb. bomb hits from fifteen SBD-3s from Hornet. Fortunately due to intel about the incoming attack her captain ordered all aviation fuel mains to the flight deck and hangars drained down, with few aircraft remaining on board as source of problems.

With nearly all fighters committed to her CAP early on: Around 06:40 her radar detected the inbound enemy strike 78 miles away, dispatching twenty-three fighters, detecting USS HORNET’s first strike wave (15 dive-bombers, 8 fighters, 6 torpedo planes). The attack proper started at 07:27 when ten SBDs attaccked her from astern while she raced north at full speed. Nearly four bombs hit, grouped around the amidships and the aft elevators, port of the flight deck centerline.

Multiple, firce fires broke out while the flight deck was completely buckled, shattered, looking loke sturck by an earthquake and now improper for air operations. The center elevator was destroyed as the port quarter two 12.7 cm AA guns and all killed inside. Crucially, the strength deck holds prevented any real damage below her waterline so she continued to maintain 30 knots. She was not found by the torpedo bombers. It was largely to Nagumo’s sound decision for a shift north leaving the American strike largely missing the Kido Butai and instead attacking Kondo’s two battleships and cruisers (CHIKUMA was badly damage).

No major fires broke out and she was still operational 5th after after her flight deck and hangars saw all fires extinguished, stil with heavy crew loss, and air operations now impossible, although she kept four fighters and a single torpedo plane aboard. Repairs kept her out of action for many months afterwards, in fact, 28 October 1942 she sailed for Truk to make emergency repairs with IJN ZUIHO via North Pass.

Later operations (1942-1944)

On 30 October 1942 in the morning, the Commander in Chief Admiral Yamamoto visited SHOKAKU in Truk, inspecting the damage, pay tribute to the dead. On 2 November 1942 she departed Truk screened by DesDiv 4 and the badly damaged ZUIHO and CHIKUMA to reach the homeland. On 6 November 1942 she arrived in Yokosuka and eetered the navy yard in priority. The extensive repairs and refit ended on 16 January 1943 as she undocked, reasigned from the Main Unit, Mobile Force to the Maintenance Force, then-reentered the drydock for refit on 8 February 1942 while on the 16 February Capt. Masafumi was relieved by Captain Okada Tametsugu.

After a long period of training, Shōkaku joined in May 1943 the counterattack in the Aleutian Islands. She teamed with CruDiv 7 (MOGAMI, KUMANO, SUZUYA) BatDiv 1 (MUSASHI) Bat Div 3 (KONGO, HARUNA) CarDiv2 (JUNYO, HIYO), CruDiv 8 (TONE, CHIKUMA) AGANO, OYODO and 11 destroyers. It was soon cancelled while underway after hearing about the Allied victory at Attu. She stayed in Truk for the remainder of 1943, apart a sweep for maintenance in Japan.

There were two sweeps however, one on 18-25 September 1943, to Eniwetok along with the battleships YAMATO, NAGATO the cruisers TAKAO, ATAGO, MYOKO, HAGURO and a destroyer screen under Ozawa tactical command, in response to TF 15 raid on Tarawa and Makin. But they never met this force and went back in Truk.

There was another raid on 17-26 October 1943, a second advance to Eniwetok with the Combined Fleet (Admiral Koga) this time to catch TF 16 (Wake Island raid). This force was staggering, comprising also the YAMATO, MUSASHI, FUSO, NAGATO, KONGO, HARUNA and the cruisers TAKAO,, ATAGO, MAYA, CHOKAI, MOGAMI, SUZUYA, TONE, CHIKUMA, AGANO, OYODO plus a generous destroyer screen.

They arrived in Eniwetok on 19 October 1943 while Koga (which replaced Yamamoto, shot down) ordered preparation for Operation RO, a reinforcement of Rabaul and New Britain. The operation proceeded as planned from 30 October to 13 November 1943. Shōkaku then departed for home, on 11 November 1943 and entered the drydock in Yokosuka, leaving it on 6 January 1944 and then training until the 17th.

Singapore operations (Feb-May 1944)

From 17 January 1944 she departed Yokosuka for Tokuyama Bay, joining ZUIKAKU for tactical exercises in the Inland Sea and on 27 January both departed for Truk, stopping underway Oita Bay. On 6 February 1944 both wree deployed to the Lingga Islands, south of Singapore, with the cruisers CHIKUMA and YAHAGI escorted by five destroyers. Singapore was designated by the high command the new advance base of “decisive operations”, close to major drydocks and fuel reserves. Shokaku there landed her air Group and departed for Lingga Roads on February, 20. In March she spent her time between Singapore and Lingga, still with her sister ship and escorted by the cruisers TONE, CHIKUMA, SUZUYA and MOGAMI. On the 25th, she became flagship of the 3rd fleet command, Admiral Jisaburo Ozawa’s Mobile Fleet.

On 4 April she was in maintenance at the Singapore naval arsenal, while on the 6th, Ozawa made IJN TAIHO his new flagship. On 12 May she deprted Lingga with CarDiv 1, for Tawi Tawi, spotted two days later 40 miles northwest of Tawi Tawi by USS BONEFISH. She stayed there until 13 June, when Ozawa launched a major sweep in the Phillippines with CarDiv 1 (Her, Taiho and Zuikaku) Crudiv 5 (HAGURO, MYOKO) and 8 destroyers, stopping en route at Guimaras in the Philippines, to bolster Saipan’s defense. Operation “A-Go” was launched the 14th.

Sinking at the Battle of the Philippines (19 june 1944)

On 15 June, with the Mobile Fleet she sailed to the Mariana Islands. On 17 June the full Mobile Fleet refuelled and reached its planned battle position spotted en route by USS CAVALLA, sent a report at 21:25 on surface and sets off in pursuit. On the 18th, CarDiv 1 prepared all this morning and at 11:00 dive-bombers are launched for search operations, six failing to return, out of fuel. At 15:20 one reported an enemy task force located 380 miles from Yap and at 20:00 the Mobile Fleet splits up as planned, Ozawa waiting until next morning to launch her strikes, pending clarification and due to the night falling.

At dawn on the 19th, her CAP is Launch, 17 A6Ms, and at 07:56 CarDiv 1 the first air strike is launched, 120 planes in total (48 fighters, 53 dive bombers, 27 torpedo planes). At 08:10 IJN Taiho is attacked and badly damaged by a submarine, USS Cavalla, which spotted Shokaku in turn at 10:52. Begins attack approach.

Meanwhile Shokaku’s strike wave suffered heavy losses, with only few returning. Nevertheless in a sea of yound recruits, the heavy core of D4Y Suisei pilots, all veterans from the Coral Sea and Santa Cruz broke through. One hit and damaged the battleship USS South Dakota, but themselves suffered heavy losses. At 11:22, Shokaku is torpedoes and takes three (possibly four) hits from USS Cavalla (Captain Herman J. Kossler). As she was caught refueling and rearming aircraft the torpedoes started fires, this time quickly out of control, and a 12:10, one stored aerial bomb exploded, igniting in turn avgaz tanks, spreading burning gasoline throughout the ship, which at that point was heavily flooded and sinking by the bow. Captain Matsubara gave the order to abandon ship but before the evacuation is complete, she abruptly took a much heavier list forward, sinking quickly bow-first with 1,272 men still onboard. Apparently her forward bulkhead bulged and then exploded under water pressure, causing a sudden and massive flooding of mid-ship compartments and hangar. IJN Yahagi, assisted by the destroyers Urakaze, Wakatsuki, and Hatsuzuki rescued Captain Matsubara and 570 men. The news of the sinking, as customary was hidden to the public and the Emperor and only was ofiicial when the ship was stricken on 31 August 1945, 15 days after the capitulation.

IJN Zuikaku’s career

IJN Zuikaku’s flight deck and Kaga in the foreground, underway to Pearl Harbor (colorized by irootoko jr)

IJN Zuikaku was commissioned on 25 September 1941 at Kure Naval Base, 1st Air Fleet, under command of Captain Yokokawa Ichibei. He was her Chief Equipping Officer since she was launched in 1940. She made an abbreviated shakedown cruise off Saeki between 26 September and 7 October, joining her sister ship IJN Shōkaku in Oita, Saeki province, to form Carrier Division 5. On 26 November, both left Hitokappu Bay for Sukumo Bay, then back to Saeki Bay and starting a trainig cruise on 2 November 1941 from Oita, and on 13 November 1941 she was Reassigned to CarDiv 5. On he 14th, rear admiral Hara Chuichi shifted his flag from her sister ship to her.

She departed on 19 November to join the gathering at Hittokapu Bay and the “Hawaii Operation”, comprsing the bulk of the Kido Butai, CarDiv 1, CarDiv 2 and themselves, protected by BatDiv 3, CruDiv 8 and the destroyers from Desdiv 17 and 18.

Zuikaku in the Peark Harbor attack

Kaga and Zuikaku en route for Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl Harbor performed by the Mobile Force saw her preparing on December, 7 at noon, 18 Mitsubishi A6M “Zeke” fighters, 27 Aichi D3A “Val” dive bombers, and 27 Nakajima B5N “Kate” torpedo bombers, launched in two waves and focusing on Oahu. Her first wave of 25 “Val” dive bombers (Lt.Cdr. Sakamoto Akira) mainly concentrated on the Wheeler Army Airfield while five Zeros strafed the Kaneohe airbase and installations. She commtted 27 “Kate” torpedo bombers for the second wave, but like her sister-ship, carrying bombs and not torpedoes, for levelled attacks, assigned to bombard and destroy Hickam Field. As we know, amost every parked plane was set ablaze, avgaz tanks and hangars, workshops, were all destroyed or badly damaged.

She also committed three spare Zeros to provide a Combat Air Patrol (CAP) over the fleet, but also lost two aircraft sent out on reconnaissance to find the missing carriers, which were lost after ditching as they diverged from the movement schedule and could not find the carriers back. Nagumo ordered a withdrawn, not ordering a third attack, and Zuikaku did not lost a single plane over Oahu.

Rabaul and Indian Ocean

Zuikaku air group in the Indian Ocean, April 1942

This has been seen above with her sister ship’s operation. IJN Zuikaku’s air group attacked the Australian bases at Rabaul (Operation “R”) on 20 January 1942, Lae-Salamaua (New Guinea) the following day. Afterwards she sortied on 16 February 1942 from Yokosuka to take on a holding position in Mikawa Bay area, ready to intercept American carriers if they approach, staying so until the 28th. That day she was back at Suzuka NB to embark her airgroup training there, ad after a stop at Kure made a sweep to Minami-Torishima (Marcus Island) in search of TF 16, but without results. She ade another sweep on 11 March 1942 with her sister ship (Under command of Vice-admiral Shiro Takasu, flagship ISE, and HYUGA to intercept a supposed US Force approachingn but fould nothing. It was another false flag, but the Doolittle raid took place on 18 April anyway.

In April 1942, she also took part in the Indian Ocean raid (Operation “C”), raiding Colombo and Trincomalee, Ceylon, while participating in the sinking of HMS Cornwall, Dorsetshire and the aicraft carrier HMS Hermes. When the mobile fleet came back on 10 April 1942 in the Pacific, Yamamoto decides to prepare a raid on Mako, detaching CarDiv 5 (Operation “Mo”) invasion of Port Moresby in New Guinea, made effective on 12 April. The day of Doolittle attack, CarDiv 5’s Zuikaku was flagship for rear-Admiral Chuichi Hara and under overall command of Vice Admiral Takagi Takeo (Victor of the Java Sea Battle). Operation”Mo” started on 1st May.

Zuikaku at the battle of Coral Sea

On 2-3 May 1942 she was waiting for the invasion to start, and bad weather prevented a launch of 9 fighters to reinforce the Tainan Air Group, at Rabaul. In addition their position was too far away to launch and respond to TF 17’s attack on Tulagi, on 4 May. On May, 7th, at 06:10 she launched a full strike under commmand of Lt.Cdr. Takahashi Kikuichi, of 9 fighters, 18 dive-bombers, and 12 torpedo planes. As the US fleet is located at last, Hra decided for logistical reasons not to diver his forces and maintained their initial objective. Long story short, Zuikaku that day lost in her twilight air group return, two D3A1 and 5 B5N2s.

The following day, 8 May, at 9:00 when the US air strike closed on the southward steaming CarDiv 5, ZUIKAKU was 9,000 meters ahead of SHOKAKU, protected by MYOKO, HAGURO and three destroyers, they were just blanked in a rain squall. She launched 4 fighters to assist the CAP, while Shokaku, protected by KIinugasa and Furutaka bore the brunt of the attack, soon hit by three bombs and detached for home, leaving Zuikaku in charge of follow-up operations.

In the meantime, their own air strike found their mark at 09:10 crippling Lexington, Zuikaku’s air group being detached to strike Yorktown, scoring three bomb hits. After 10:40, Zuikaku commenced recovering her crippled sister-ship’s returning strike planes, plus her own from 11:00, so her hangar and flying deck were parked full. She had aboard 46 planes from both carriers, seven damaged ones ditching and it was 12:30 when her captain esteemed she was ready to launch a new attack.

After an inventory it was found her air strength was too depleted and Takagi cancelled it at 13:00, confirmed 45 min. later by Inoue and to retire, while at 14:20 the invasion of Port Moresby was in turn cancelled, making this engagement an American pyrrhic strategic victory. In all, Zuikaku lost 4 A6M2 fighters, 6 D3A1 dive bombers, and 9 B5N2s TBs.

Summer Operations

Aichi D3A “Val” taking of from IJN Zuikaku at the battle of Coral Sea

In late May, June and July, Zuikaku’s operations were as follows: On 21 May 1942 she was spotted at 01:53 by USS POLLACK on course towards Kure at 20 knots. USS POLLACK had first mis-identified her and had little time to place herself in a good position to fire, when crossing her path from left to right, fired four torpedoes at 2,000 yards on her starboard but missed. At Yokosuka, she received maintenance while her air group needed to be reconstituted.

On 5 June 1942 Captain Yokokawa was relieved by Captain Nomoto Tameki and she dropped anhor in Hashirajima anchorage. She departed on 15 June to join Rear-admiral Kakuta Kajuji’s second Striking Force, arriving on 23 June at Ominato to meet with IJN JUNYO, RYUJO, and ZUIHO as part of 1st Air Fleet Cardiv 5, Northern Force scheduled for the Aleutian operations. On the 28th, KdB2 is sent to patrol south of Kiska and she stayed there until 6 July 1942, before heading to the homeland, Oita Bight on the 12th, then Hashirajima, and reassigned to Striking Force, 3rd Fleet, CarDiv 1, with her sister ship and ZUIHO.

A ceremony was conducted on the flight deck, the crew standing in honor, photos being made, as Hara’s flag is struck, leaving the carrier. On 20 July she headed for Kure drydocked ten days later for maintenance until 12 August and three days later, sailed to Hashirajima, and her sister ship, now the flagship of CarDiv 1 (Nagumo). They were prepared for a major operation in the Solomons.

The Guadalcanal Campaign

This all had been seen with Shokaku already. Both carriers operated together in CardDiv 1 and by that time, Zuikaku was commanded by Captain Tameteru Notomo. She was dispatched with Zuihō to oppose the US offensive and on 24 August 1942, she took part in the Battle of the Eastern Solomons, her air group severaly damaging USS Enterprise, all believing she has been left for dead. Next, she was based in Truk for the next few months. Nothing much happened, but she made a single unfruitful sweep on 10-23 september. On 26 October 1942, she took part in the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands.

Her aircraft badly hit USS Enterprise again, a “ghost” just repaired. They also crippled USS Hornet (later abandoned and sunk by Japanese destroyers). Both Shōkaku and Zuihō were severely damaged in return, leaving Zuikaku in the very same situation as at the Coral Sea, left alone on the battlefield and having to recover all surviving aircraft, 67 returning out of 110 launched. he withdrawned to the home islands via Truk, spending time afterwards training and ferrying aircraft.

On 4 November 1942 she departed Truk for Kure with IJN MYOKO and two destroyers, transferred on 21 November Tokuyama Bay, then on 6 December at Murozumi Bight for intense air training exercises along with the battleships IJN MUSASHI, NAGATO, and YAMASHIRO. On 10 December she headed for Kure via Tokuyama Bay, then on 22 December at Iwaishima Island, Kure and Yokosuka via Oita Bight, arriving on 28 December for maintenance and modernization.

She notably had a type-21 radar fitted atop her Type-94 director, similar to the one fitted on her sister ship in August. But her’s was surrounded by circular splinter shield. On 31 December she left for Truk with personnel of IJAAF 45th Sentai and a load of Kawasaki Ki-48 Type 99 (“Lily”) light bombers for Truk.

1943 Operations

In January, Zuikaku departed Truk for home with fve destroyers and arrived on the 12th at Oita, before proceeding to Kure. She departed newt for Iwakuni Bight and on 18 January became flagship, Third Fleet, departing Iwakuni for Truk with IJN Zuiho. From 29 January to 8 February 1943 she participated in Operation “KE”, the Evacuation of Guadalcanal, heading for Ontong Java Island area, north of Guadalcanal with Zuiho and Jun’yo, covering troopships loaded with ground forces and heading back for Truk. On 29 January they detached however a rearguard of 36 fighters to Rabaul, in order to cover further evacuations before heading back to Truk again. On 11 February 1943 she flew another air group into Buin. On the 15th, she detached another to Kavieng. In May 1943, she was assigned to the later cancelled counterattack in the Aleutian Islands. Captain Kikuchi Tomozo took command whille she was stationed at Truk, making a single raid to try to reach the US forces raiding the Marshall Islands.

On 24 June 1943 she departed Kure for a training cruise in western Inland Sea, ending on 10 July, bot carriers being re-united at Truk and on the 18th she sortied to Eniwetok with battleships Yamato, Naagaot , cruisers and destroyers (Under Ozawa’s tactical command) trying to catch TF 15 returning from raiding Tarawa and Makin, but failing to meet them. On 17-26 October she took part in another of such sorties under Koga’s command this time for TF 16 attacking Wake, for nothing. In between, Koga ordered preparation for Operation “RO”, the reinforcement of the Rabaul and New Britain air forces by ferrying aircraft there.

Back in Truk on 30 October, Operation RO took place, and Zuikaku received her transferred designated sections of air group ashore, the operation commencing on 1 November, the air groups flying south to Rabaul and on 7 December Zuikaku depart for Kure for a maintenance overhaul, while on 18 December Captain Kikuchi is releived by Captain Kaizuka Takeo.

January-May 1944 Operations

On 8 January 1944 Zuikaku entered the drydock and the operation was over on the 17th. After short trials and training she was prepared for further operations in the Western Inland sea, starting her training cruise from 1 to 6 February 1944, before stopping in Sumoto Bay and heading to be reunited with her sister ship, prepared to depart for Singapore, accompanied by Chikuma and Yahagi and five destroyers, arriving on 13 February, as the new advanced base for “decisive operations”, landing her Air Group.

On the 15th, she received Air Group 601 (Cardiv 1) and departs for Kure on the 20th, arriving the 27, possibly taking part in the sinking of the submarine USS GRAYBACK in the East China Sea while underway (sources differs on this). From 5 March she started a training cruise in western Inland Sea and three days later, departed Sumoto Bay for Singapore to ferry more planes, while completing and modernizing her air group with B6N1s and A6M5s. BatDiv 3 (Kongi, Haruna, Mogami, and 3 DDs escorted her).

On the 11 they are ambushed by USS LAPON, starting her attack on her starboard flank 3,200 yards away, but apparently a sudden zig-zag manoeuver foiled the opportunity to lauch. On the 14th, she arrived at Seletar with ogami, on their separate way to Lingga. She departed the 25th to Singapore and entered its drydock at Seletar for a quick maintenance, while Sjokaku stayed at Lingga as flagship of 3rd Fleet. She left the dockyard on 31 March and joined her sister ship at Lingga, remaining on station in April. On 30 April 1944 she headed for Lubang, was back in drydock, then on 6 May 1944 she departed Singapore for Lingga, proceeding from there for Tawi-Tawi anchorage with her sister ship and IJN Taiho, third ship of CarDiv 1 at the time.

On 13 May 1944 at 06:18 off the western coast of Borneo USS LAPON spotted and reported the Mobile Fleet underway, identiying Taiho, but she is detected and depth-charged, escaping. This meant a delay before she could surface and report, but soon a “wolf-pack” is hastily assembled. On 14 May, 14:00 they are spotted spotted 40 miles NW of Tawi Tawi by USS BONEFISH , reporting the sighting. They arrived the following day.

Zuikaku’s Philippines campaign

The aircraft carrier stayed in Tawi Tawi until 13 June 1944 and soon was scheduled for more operations as Ozawa is warned of other possible operations after raids on Saipan. He decided to move his forces towards the Philippines, in order to possibly cover Saipan if attacked. The Mobile Force stopped in the morning at Guimaras in the Philippines on their way to Saipan and in the evening the Combined Fleet sent orders for Operations “A-GO”, followed by intense preparations.

The operation commenced on the 15th, the Mobile Force being inderway in the Visayan Sea when the Battle of the Marianas started. The force came through San Bernardino Straits, entered the Philippine Sea, still bound for Saipan and on 16 June, the Mobile Fleet refuelled while BatDiv 1 was comimtted to relieved Biak, recalled later just as the invasion of Saipan became clear. On the 17th, the Mobile Fleet gained its designated battle position, identified by radar by USS CAVALLA, Cdr. H.J. Kossler refusing to attack to stay as radar/radio picket. Nimitz was soon informed and sets off in pursuit, leading to the Battle of the Philippine Sea proper, on the 18-20.

Long story short, on 19 June Taihō and Shōkaku are both sunk by American submarines, leaving Zuikaku alone again, for the thord time, on the battlefield.

She recovered the few Division’s remaining aircraft (244 of 374 planes lost) and on the 20th, was attacked by TF 58 carriers at around 17:30-17:46. A combind air strike from Hornet, Yorktown, and Belleau Wood. Captain Takeo however despite the ondlaught made quie a show of his seamanship, by dodging away all incoming attacks, one by one, manoeuvering hard rudder port and starboard. Helped by the growing darkness, heavy AA and evasive actions, she managed to stay alive while taking many near-misses, until her chance ran out: A single 250-kg bomb hit just aft of the island, penetrating the starboard side flight deck edge, close to the twin funnels and badly damaging a 127 mm mount in the process. The bomb ended n the hangar, starting large fires, soon extinguished by experienced damage control teams.

The damaged carrier was back on 22 June 1944, 13:00 at Nakagasuku Bay in Okinawa. Survivors of Hiyo, Taiho are transferred to Zuikaku from overcrowded rescue cruisers and destroyers and she departed for home with also onboard 25 fighters, 10 torpedo-bombers plus about 12 floatrplanes from the surviving cruisers. At that stage, IJN Zuikaku was not only the sole survivor of the Kido Butai, like USS Enteprise she was the last operational fleet carrier left to defend the Philippines.

On 2 August 1944 she left Kure drydock after repairs, and the admiralty decided of Changes drawn from lessons learned from the Marianas battle. She was fitted with a new modified mainmast, whose yardarms are angled up and back. Her AA armamement was bolstered in a considerable way and for the first time she is fitted with anti-air rockets, with a massive final battery of sixteen 127 mm (it’s twice the number of an Essex-class carrier) as well as ninety-six 25mm guns, plus its six new 28-barrel 120 mm AA rocket launchers.

The latter were mounted on platforms at each end quarter of the flight deck. She also received an experimental camouflage design paint on hull, an olive green fake cargo ship profile, as well as a complicated pattern on her flight deck made of disruptive lines reminiscent of WW1. Reassigned to the CarDiv3, 3rd fleet, she sailed for a training cruise on the western part of Inland Sea. The third carrier division also comprised IJN Zuiho, Chitose, and Chiyoda, all being converted light carriers. Zuikaku remained certainly the best fleet carrier of the IJN at the time, and was flagship of the unit.

Zuikaku in the September 1943 propaganda movie “Torpedo-bombers attack!”

In the time preceding the battle of Leyte, she made another training cruise outside Beppu Bay, to train mostly rookie pilots in landings and take-offs (qualifications) and until 21 September 1944, more training in the Inland Sea outside Beppu Bay. At this occasion she became a movie star, shown in a newsreel showing her launching torpedo planes, used for the propaganda film “Torpedo-bombers attack!”, and now a rare and important footage for any documentary. On the 22 she was in Oita Bight and on the 7th, in Kure, staying there until 15 October when a ceremony saw Captain Kaizuka Takeo leave her to be promoted to Rear Admiral.

On the 20 October she departed to take part in Operation “Sho” in Ozawa’s decoy force. She “only” had onboard 28 A6M5 “Zeke” fighters plus 16 A6M fighter-bombers variants, 7 D4Y2 “Judy” dive bombers used for reconnaissance and 14 B6N2 “Jill” torpedo planes. Their task was to draw out Halsey’s force out of the landing zone at Leyte, a mission which Ozawa succeeded.

Zuikaku end at Leyte (25 October)

Zuikaku at the battle of cape Engano 1944

This day took place the Battle off Cape Engano: at dawn (05:55) Zuikaku launched four B6N2 in recon mission, followed at 06:10 by five A6M5s and one D4Y2, order to land at Nichols Field and reinforce the flight prked there for ucoming cover missions. At 07:17 she launches four A6M5s to partipated in the local CAP. At 08:04 her radar detects enemy planes at 200 km. Se immediately launches her last planes aboard, nine fighters, for the CAP, while raisin her large naval ensign as battle flag, steaming at 24 knots towards TF 38.

At 08:30 she spotted the first wave of US attackers, torpedo planes, better drilled as they now attacked first on both sides, so she start evading manoeuvers. At 08:35 however she is targeted by dive bombers and after several near-missed, she is hit by three 250 kg bombs on her flight deck: One hit her port side amidships, setting ablaze the upper and lower hangars. Just two minutes after that, she take a torpedo hit on her port side aft amidships. It struck just between No.2 and No.3 elevators and flooded the engine room and the one after, while the forward shaft is bent and had to be stopped spinning to avoid greater damage.

The uneven rapid flooding while she arlready made a sharp turn to port increased the list to 29.5 degrees, swiftly corrected however. At 08:40 she only had her starboard shaft operational, the outboard one returning to operation after the list is corrected, keeping a steady 23 knots, also having all her starboard boilers retaining steam. At 08:50 damage control teamed extinguished both hangar deck fires. They also managed to correct her list back to 6° port, and she could steer by using the emergency power. Her transmitters are destroyed so she could no longer remains as a command ship, her flag planned to be shifted to the cruiser Oyodo, but before this at 09:53 the USN second attack wave arrived and in 15 minutes, Chiyoda is sunk, but Zuikaku dodged more torpedoes and bomb hits;

At 10:32 as planned, Zuikaku slows down to allow Oyodo coming alongside her to port. Ozawa and his staff then transfer to the cruiser, both ships departing at 11:00. With Chitose sunk and Chiyoda left sea in the warer, Zuikaku is reduced to 18 knots and recovery is hard. In fact nine fighters of her CAP are ditching.

At about 13:08 she is now steaming at 20 knots when the third wave, the larger one is spotted and steam is raised against to reach 24 knots with the remaining two starboard shafts, not a small feat. Soon however, Zuikaku is framed by an “anvil” combining torpeod planes on boath sides simultaneous with dive bomb attack.

Despite of this, captain Kaizuka Takeo still manage to avoid the first few runs. Overwhelmed in eight minutes, his ship hit in at the same time by six torpedoes starboard and port (four). Her torpedo maintenance shop was destroyed, more HA guns are knocked out, No.3 boiler room is flooded, and three bombs penetrated the flight deck aft the third elevator aft, hangar fires breaking again.

At 13:21 she took three more torpedoes and a bomb, which struck port side of the center line, in between her middle and aft elevators, a 5th and 6th torpedo hitting her port side, flooding completely No.2 and No.4 boiler rooms and remaining port forward engine room. She soon listed 14° to port, hit a last time at her port quarter, flooding the steering room. At 13:25 she was effectively dead in the water, with 20° list increasing by the minute.

At 13:25 USN planes withdrawn but the carrier was left for dead. Eventually, with floodings on boath side, she settled deeper in the water but the list reduced. The captain order all hands on the flight deck, and he addressed his crew from the island about his intention to go with her ship, followed by lowering the naval ensign, a bugler playing Kimigayo, then ordering to abandon ship at 13:58;

By that time her list was 23° and it assumed that she half-rolled to port at circa 14:14, sinking stern first, carrying with her the Captain, 48 officers (most remained with him) and 794 petty officers and men. 47 officers and 815 men were later rescued by the destoyers Wakatuski and Kuwa. LtCr. Aido Takahide, Air Group 601 officer survived too. He would never see his pilots again.

Battle of Cape Engano October, 25, 1944

Zuikaku under attack, Cape Engano

Epilogue

And with the ship also sank the last veteran of Pearl Harbor and all hopes for the IJN to return the situation in the Pacific.

Indeed, what was left after that were the completing IJN Shinano, first (and last) Japanese armoured carrier, quickly sunk at her first sortie a month after this, the Ryuho, Junyo, the first two of the Unryu class (Unryu and Amagi) and the escort carriers Kaiyo and Shinyo. Four other Unryu class and IJN Ibuki were never completed. But more crucially, there was a grave shortage of experienced pilots, fuel and resources. Zuikaku in October 1944 had perhaps the last and best veterans airmen of the IJN at that time.

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign

Incomplete phrase.

In June 1942, Shōkaku and Zuikaku receoved extra triple mounts and thus, were given two extra Type 95 director. In October 1942, and before the Battle of the Philippine Sea in June 1944, extra 25 mm were added without control. Zuikaku later, as a surviving ship was ???

fixed !