Japanese Navy vs German Navy

Introduction: The first air-land-sea battle

The battle of Tsingtao was one of these twists of history which seems odd to us today: Both Axis members of WW2, Germany and Japan, were indeed at each other’s throat at Tsingtao, a German-held colony in China twenty years prior. Officially, the attack of the port was a token of the recent alliance of Japan with Great Britain on the side of the entente.

Officiously, this was the perfect opportunity to get rid of another western presence in the Yellow sea, securing nearby Korean peninsula from all foreign influence, by then under firm Japanese control, and taking another hold in the Chinese continent, on a strategic place, and a modern, well-developed and equipped enclave that was further developed.

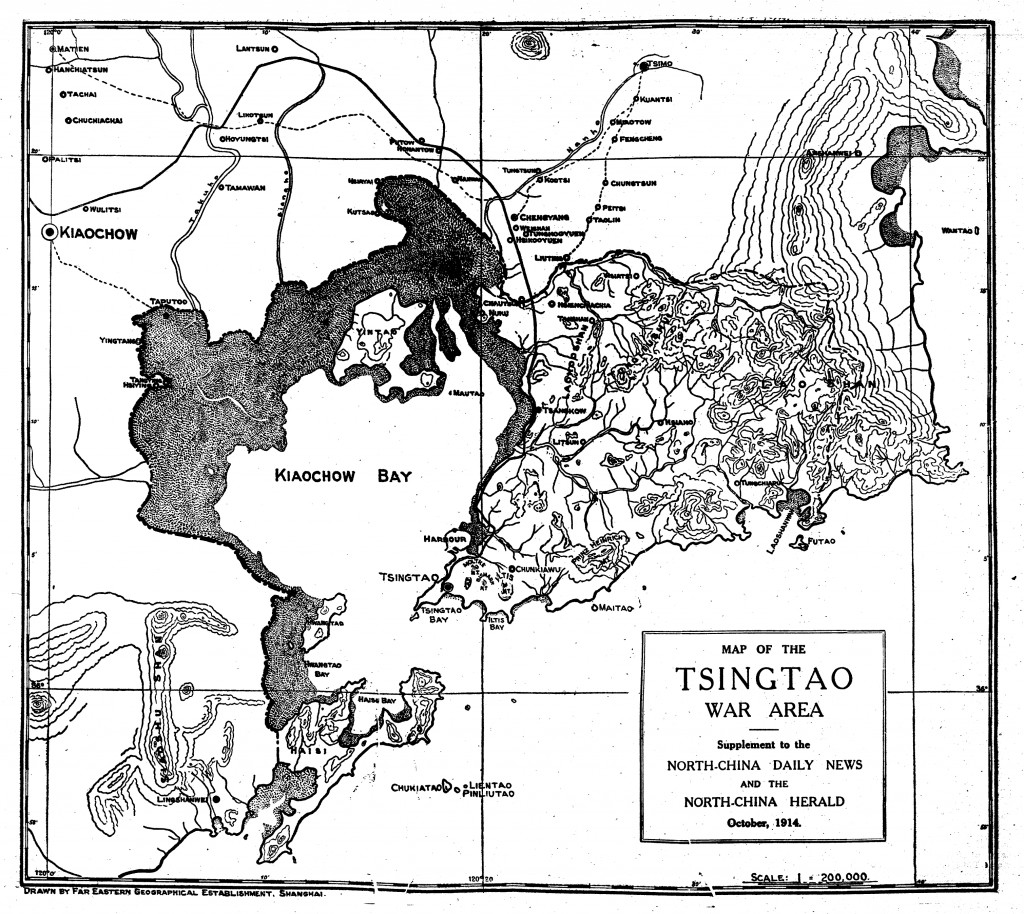

Map of Tsingtao in ww1 – source

The modern city of Qingdao, is now one of the richest and most dynamic ports in modern China, why the German colony inheritance resides only in the best known Chinese beer… But the naval battle was the occasion to see an early combined arm operation, a more complex operation than the Japanese planned ten years earlier at Port Arthur, not far from there.

Its consequences were the end of the German Asiatic squadron of Von Spee, obliged to flee and launched in a rampage over the globe, settled for good in the Falklands; but also of any German presence in Asia. After Russia, only France, Britain and the Netherlands remained as imperialist powers in the area, but it confirmed once again to Japanese falcons their superiority over western powers.

The colony of Tsingtao

The very name of Tsingtao is to add to the long list of Chinese humiliations and explains the current will of the government to restore grandeur through naval power, territorial acquisitions and economical means. In 1891 the Qing Empire made Tsingtao (Jiao’ao) a defense base and improved its fortifications.

However at that time, Western powers were still present in force and reported the move to naval officials. They Germans eventually made a complete formal survey of Jiaozhou Bay in May 1897. Meanwhile two German missionaries were killed in the Juye Incident the same year. Protestations backed by military power led the weak Chinese government to agree a 99-years concession of Kiautschou Bay in Shantung.

Quickly German troops were ordered to seize and occupy the fortifications as they could have been a threat to Western (and German) trade in the area. This was not long before the Boxer rebellion. Chinese authorities indeed declined any attack to retake the strongpoint, de facto annexed by Germany.

The concession quickly became a fully-grown German colony which received high priority by the Kaiser given its strategic value. This was the only German presence in Asia. A moderately large territory though, 552 square kilometres (136,000 acres; 213 sq mi) much smaller than Hong Kong (2,755 km2), Singapore (721 km2), but far larger than Macao (30 km2) and Shanghai (6.3 km2). There was still plenty of room for development.

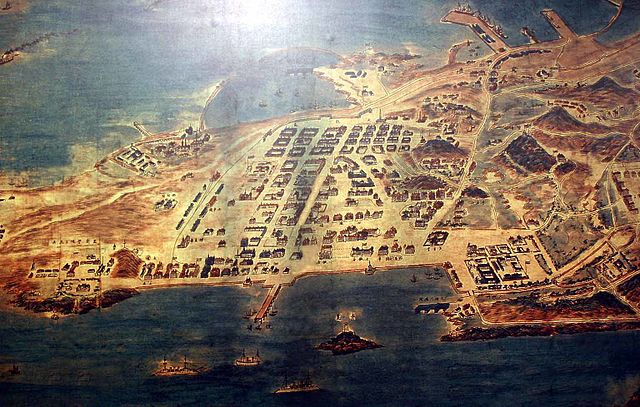

In 1898 though, this territory was poor and remote, the Marktstrasse (Market street) was nothing more than the old main street of the Chinese village, with fishermen and craftsmen shops and houses around, hardly a city like Shanghai. Therefore the Germans took at hart to develop it. The Chinese inhabitants were expropriated and relocated further east.

The former village was razed and rebuilt from scratch with wide paved streets, large stone-built housing areas, and government buildings. Moreover, electrification was installed, as well as drinking water and a modern sewer system. All these were quite new for the time and for China, driving locals back in. Trade flourished once again.

Development went quickly also on the harbor side, with a solid stone jetty and breakwater, safe storage areas, cranes, a harbor administration center, and a drydock. Tsingtao soon showed the highest school density and the highest per capita student enrolment in all of China.

This colony in all but name became the pride and joy of the German Empire, and soon a Brewery was installed, producing a local beer under the same name. Also the inevitable Protestant and Roman Catholic missions also settled. However the concession was unique as it was managed directly by the Imperial Department of the Navy since the arsenal and Asian squadron were the main strategic reasons of this enclave.

The Far East Squadron was then soon constituted with the best units, mostly cruisers, that can be mustered, and grew in size. On land, the colony was defended by marines of III. Seebataillon. The village became a city, with thousands of German residents, mostly families of officials in China and navy personal, and it was connected to the continent via the recently built Tsingtao-Jinan Railway Line ending in the Tsingtao Railway Station, nearby brand new locomotive works, all German.

Military situation in August 1914

The German naval forces present before 1914 were the Asian squadron commanded from its creation by Admiral Count von Spee. He very much setup this force and ordganized its support from TingTao, but his fleet also had other bases in the pacific to sail to an from, controlling a wide area: Samoa and New Guinea but also German Micronesia, the Marianas, the Carolinas and the Marshall Islands.

Von Spee’s fleet indeed served central Pacific colonies on routine missions. The fleet eventually was out of Tsingato when the war broke out. They joined early on in the Marianas Islands. The plan was to return back to Germany, fearing to be be trapped in the Pacific by much more powerful Allied fleets, especially British and Japanese.

Even before TsingTao, there was a minor British naval attack on the German colony on Shandong in 1914. German presence here was merely symbolic and the attack was swift and decisive; Japanese troops planned to besiege Tsingtao and eventually occupied the city and surrounding province after Japan’s declaration of war on Germany, as part of the Anglo-Japanese Alliance.

Siege and battle of Tsingtao

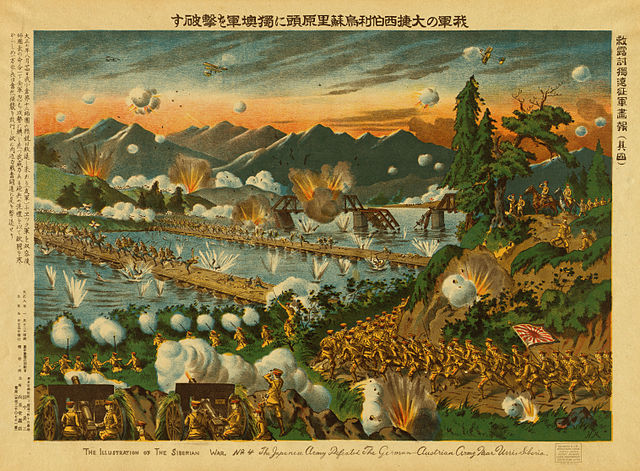

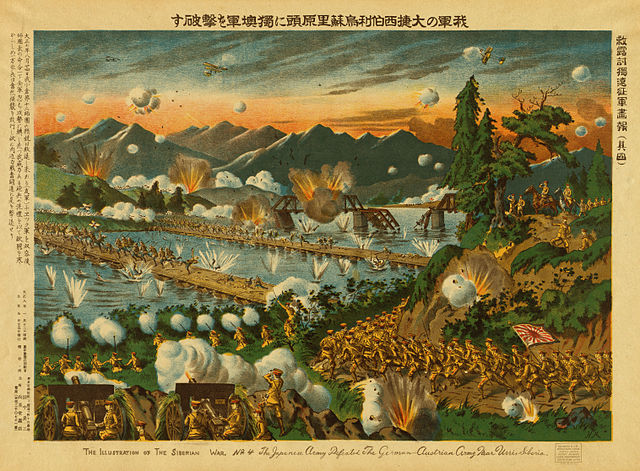

Japanese lithograph of the battle of Tsingtao

Tsingtao (Western medias)/Tsingtau (Germany)/Qindao (China), is frequently associated with the Japanese attack, but the British also participated. The land siege was relatively short due to the overwhelming disproportion of forces, it lasted from 31 October to 7 November 1914, so eight days in all, but the divesionary attacks in the province, and with the naval blockade, it lasted for two month. It was also the accumulation of many “first”:

-First encounter between Japanese and German forces

-First Anglo-Japanese operation of the war

-First combined operation (naval, land, air)

-First naval air attack

-First night bombing raid

-First and last major operation of the pacific front during the war.

Indeed for the last point, the attack on other pacific islands was quick and decisive affairs that rarely took more than several days. Nothing to do with the protracted campaign in East Africa for example, where Von Lettow-Vorbeck succeeded despite limited forces to maintain large entente forced for very long in a protracted campaign which can only be compared to Rommel’s exploits in North Africa later.

German troops parading en route to the frontline in Tsingtao

The German presence here was also seen as a threat by the British, which leased Weihaiwei, and the French for their southern colony of Indochina, at Kwang-Chou-Wan. In addition Great Britain cemented an alliance with Japan, which included the building of the Japanese Navy, from ships to arsenals and academies. The strong bonds established in 30 January 1902 would play at full during the attack on Tsingtao. On the Japanese perspective they were also a counterbalance to the Russian presence in the region and a blank check to its own imperial ambitions.

The Russian fate was sealed as we know at Tsushima three years after this important alliance. This battle eliminated Russian presence and comforted Great Britain that its Asian ally was reliable and strong, so the bond was maintained when WW1 broke out.

In August 1914 indeed, the British government prompted Japanese assistance in the name of the alliance. Indeed the German Asiatic squadron was a deadly threat for the British Colonial Empire. On the Japanese side, German concessions were tempting targets for its own ambitions. Based on this, on 15 August, Japan issued an ultimatum to the German government to evacuate all their concession from any ships and from Japan while they asked to take control of Tsingtao. On 16 August, Major-General Mitsuomi Kamio, head of the 18th Infantry Division, prepared his troops for a landing at Tsingtao.

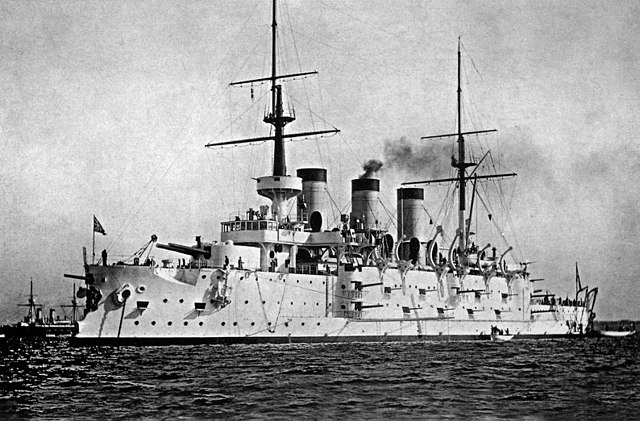

The Suwo (ex-Pobeda) that we just see in the previous post, captured in 1905 by the IJN was used as lead ship for the combined fleet off Tsingtao

German Naval forces in Asia in August

On 23 August the ultimatum expired and the declaration of war against Germany became effective. Meanwhile the East Asia Squadron, dispersed at various Pacific colonies was reunited Northern Mariana Islands and did not even tried to join Tsingtao such was the disproportion of forces.

Indeed he decided to head for the Indian ocean, and perhaps trying to reach the Atlantic and head for home waters. This was a dangerous trip to say the least, as to avoid the Suez canal, the only choice left was great cape, Good hope. Trying to reach the Terra de Fuego on the eastern route was out of question given the presence of the Japanese Navy in the pacific, and distances for coaling; However in the end, Emden made a diversion in the Indian ocean while the fleet headed for the west coast of South America.

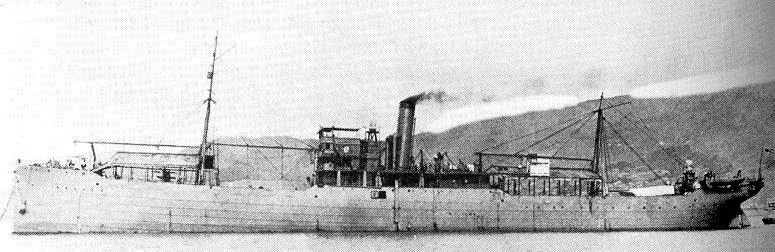

The seaplane carrier Wakamiya, which played a vital role in the battle, supplying informations about German positions and movements to gunners of the fleet and on land, and even making strafing attacks in some occasions.

On the German side, the boxer rebellion made a possible Chinese assault on their colony a real concern and they began fortifying the surroundings. The port and town were protected by steep hills, a natural line of defense which was fortified from the Kaiserstuhl to Litsuner Heights. Another 17 km (11 mi) defensive line was set in the inner ring of steep hills. The third and last line was only 200 m (660 ft) above the town.

Map of the colony, the pride of the German Empire (From Pinterest).

German preparations

These lines comprised a network of trenches with batteries and bunkers, all built in preparation of a possible siege. Work has been hectic during the ultimatum and from early August. The German administration also bolstered the sea defenses, fearing the Japanese fleet. Mines (which had proved their devastating effectiveness in 1904) were laid in the approaches to the harbour. Also coastal fortifications were raised, four batteries and five redoubts, well equipped but only armed with existing artillery, obsolete Chinese guns, but well manned by trained crew and large supplies of ammunitions inherited from the Chinese garrison.

German front line at Tsingtao 1914; the head cover identifies these men as members of III Seebataillon (III Sea Battalion) of Marines.

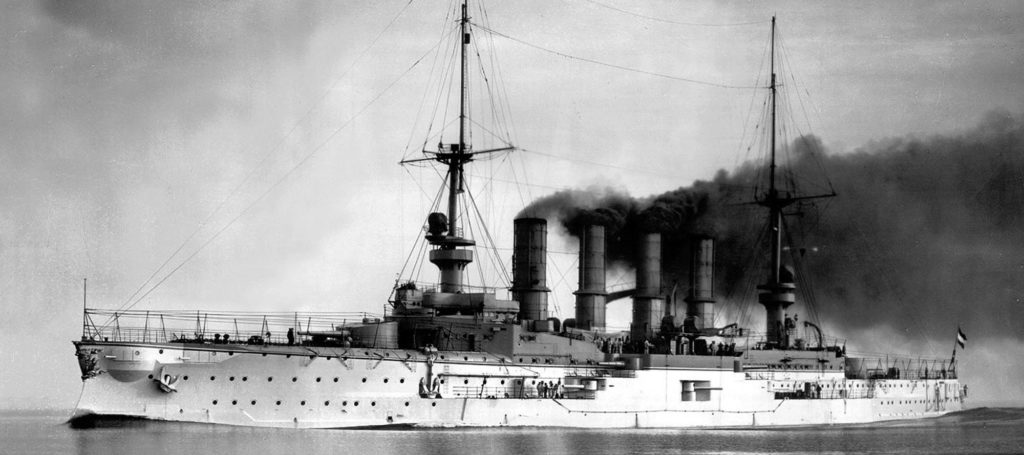

In addition to the coastal defences, the Harbor was still protected by some ships. Not all were part of Von Spee squadron: These were one protected cruiser, the Austro-Hungarian Kaiserin Elisabeth, one torpedo boat and four gunboats. The Kaiserin Elisabeth was one of the older cruiser present and mostly used for training in Asian seas. The ship was of dubious value at sea, but could add its own artillery and crew (324) to the already strong 3,650 German infantry present in the concession, manning the very long defensive ring.

Most of them were Marine troops recognisable to their colonial hat and blue uniforms, but other were from the army and shown the classic feldgrau uniform with cap, wearing proudly their pickelhaube in parade in order to bolster the population morale. In addition there were also bout 100 Chinese Police, but their loyalty was dubious at best. Last but not least, the colony had a single plane for reconnaissance.

Japanese landing boats preparing to land at Tsingtao

Japanese Forces

Facing the Germans, the Imperial Japanese Forces seemed overwhelming. In all, 23,000 Japanese infantry were gathered for the assault, with officers which were already battle-hardened and experienced by the recent siege at Port Arthur. Later on the assault would benefit from 1,500 British infantry. The Japanese Infantry could also bring on the shores 142 artillery pieces, not counting the guns of their ships, 4 battleships, 2 battlecruisers and 1 destroyer, representing a large section of the Imperial Navy.

One of the auxiliaries was the Wakamiya, a seaplane carrier, which could bring there four Farman MF.11 seaplanes for observation. The combined fleet’s battleships were pre-dreadnoughts, led by ex-Russian Suwo, carrying Vice-Admiral Sadakichi Kato’s mark.

The British bring from their own China station the battleship HMS Triumph and the destroyer HMS Usk. Knowing the German coastal defences were a potential threat, as well as mines, two lower-value captured pre-dreadnoughts made the bulk of this force, reinforced by the Kawachi and Settsu and battlecruisers Kongō and Hiei which were there in the background to repel any relieving German force at sea. And indeed, HMS Triumph was later claimed to be damaged by German shore batteries.

British troops arrives at Tsingato in November 1914 to occupy part of the city. By then the siege was over and they will soon depart.

Start of the operations

Even before the landings started, the IJN began its deployment on 27 August. Vice-Admiral Sadakichi Kato (battleship Suwo) blockaded the coast of Kiaochow, the peninsula. He was soon reinforced by the British Royal Navy (RN), sending from the China Station’s the pre-dreadnought HMS Triumph and destroyer HMS Usk. German press was present after the siege to report the Triumph’s damaged by German shore batteries. Meanwhile, Wakamyia’s planes prepared for a reconnaissance of the surroundings of the Tsingtao harbor and made a survey of the triple-layered defences.

The 18th Infantry Division was responsible for opening the show, making the the initial landings with some 23,000 soldiers in waves of boats quickly joined by 142 artillery pieces gradually bring to the shores. Landings started on 2 September at Lungkow, amidst heavy floods. To secure any possible reinforcements and flankings, 16 years after on 18 September another landing took place at Lau Schan Bay, about 29 km (18 mi) east of Tsingtao. China’s protestation for this violation of her neutrality did not stop the Japanese.

However because the intentions of the Japanese were not unclear at that stage, the British Government decided to send a small British contingent from Tientsin to take part in the landings commanded by Brigadier-General Nathaniel Walter Barnardiston, comprising men of the 2nd Battalion, South Wales Borderers and later the 36th Sikhs. However after a friendly fire incident the Japanese gave the British troops some kimonos to wear to be identifiable, which probably cause quite a sensation and laughs.

The Austro-Hungarian cruiser Kaiserin Elisabeth

On the German side, east troops and Chinese were sent to reinforce the inner and city defences, and Kaiser Wilhelm II quickly sent a message by telegraph that the colony was not to be lost at any cost, even declaring “… it would shame me more to surrender Tsingtao to the Japanese than Berlin to the Russians”. This put some pressure on the shoulders of naval Captain and Governor Alfred Meyer-Waldeck.

In addition to his crack troops, the III Seebataillon, he had reinforcements from Chinese colonial troops and Austro-Hungarian sailors from the Kaiser Augusta. The great total was around 3,625 men but this was still thin to man all trenches and fortifications, and about half of these were sent to man the cruiser while the other half took positions with artillery batteries and defensive lines.

Naval Operations

The cruiser stayed in harbor in a static position to support the defense, however on 22 August, German S90 took part in repelling a naval reconnaissance made by China Station’s HMS Kennet. The latter was doing a routine monitoring of naval trade routes when she was intercepted off Tsingato by S90 and the gunboat SMS Launting, whereas a coastal battery soon joined the fray. The destroyer retired, damaged, receiving two hits from S90 and was written off for the following week.

On 2 September, the German gunboat SMS Jaguar catch the stranded Japanese destroyer Shirotaye off the coast and sank her.

On 5 September, Japanese reconnaissance floatplanes, of the famous Farman MF.11 model, the “longhorns”, made a complete survey of the harbor, the city and its defenses. This was crucial to help draw landing plans of operations; More importantly he reported the absence of the German East Asia squadron, which reassured the combined fleet. Soon the admiral ordered the most modern ships to retire and avoid any risk in the following coastal operations. A dreadnought, pre-dreadnought and cruiser left the blockade.

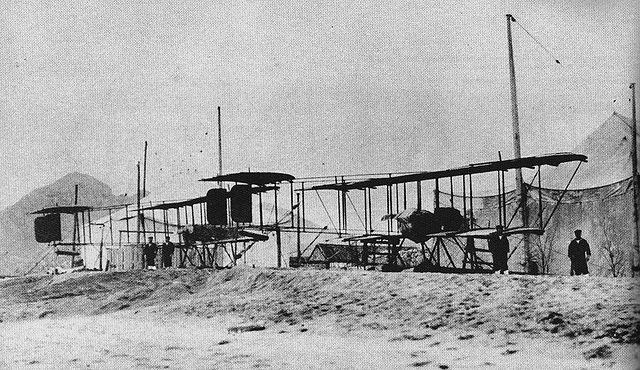

Japanese Farman Planes at Tsingtao after the siege. They led the first air-sea battle and first naval air night bombing raid in history.

However a day after, on 6 September, these planes were launched by the Wakamiya with bomblets, in order to try to hit the ships present in Qiaozhou Bay, SMS Kaiserin Elisabeth and Jaguar. But both ships had well trained crews manning AA guns and they repelled the Farmans. This was incidentally the first air-sea battle in history. This did not prevent the two ships to make a bold sortie, trying to attack the Japanese.

But after a while the ship was anchored for good and her 15‑cm and 4.7‑cm guns were removed to create the batterie Elisabeth, manned by her crew. Meanwhile on 28 September, SMS Jaguar made another raid and successfully hit the Japanese cruiser Takachiho. However the same day, all three remaining gunboats, Cormoran, Iltis and Luchs.

Later, the Takachiho would be hit by a single torpedo launched from S90, 10 nautical miles southeast of Jiaozhou Bay, sinking with all hands. The Imperial German Navy honor was saved. However, having failed to lift the blockade S90 Ran out of fuel when making it back to the harbour and she was eventually scuttled in Chinese waters the following day. On 29 October, this fate was shared by SMS Tiger, and on 2 November, SMS Kaiserin Elisabeth.

The siege

Instead of spreading his forces thin on the outer defensive lines, encountering the risk of seeing breakthrough in many points and his forces surrounded by flanking and rear attacks, he choose to concentrate all his troops in the inner defensive circle, close to the city. That way he could better man the perimeter and avoid local gaps and breakthroughs.

On 13 September this was Japanese turn: They landed first a cavalry corp to raid on the German rear-guard at Tsimo. Troops there were second-rates and their officer ordered a withdrawal. This allowed the Japanese to take control of Kiautschou and the Santung railway. General Kamio howener at this point knew he has dangerously overstretched his supply and communication lines and as the weather degraded fast he decided to stop his advance and to fortify in situ. Later he ordered the reinforcements to turn back and later he will re-embark and land his troops at Lau Schan Bay.

On 31 October the Japanese surrounded the city and started to dig parallel lines of trenches, a copycat of what they did already at Port Arthur. After great efforts they bring at range several 11‑inch howitzers to start pounding the fortifications, added to the already devastating and constant barrage from Japanese naval guns. During the line, they advanced their line closer to the city, and their artillery pummelled German positions for seven gruelling days. We talk here of 100 siege guns with about 1,200 shells each on average.

However as customary with sieges, if Germans were able counter-battery fire with the guns of the port fortifications, they eventually ran of ammunitions, and on 6 November, their guns were all shut. In addition, if they could accurately spot enemy position thanks to Lieutenant Gunther Plüschow’s Taube, the second one was short down early in the campaign.

German pilot biographic: Gunther Plüschow

During this time, Plüschow attacked the Japanese blockading ships in several occasion, more as a nuisance than anything else, dropping explosives and all kind of improvized ordance, injuring some but never cause any concern. Apparently however he met and engaged a Japanese Farman and allegedly shot the pilot with his pistol, making it -non officially still- the first aerial kill of the war. When the situation was dire, he was given by the governor in November 1914 the last dispatches to be sent to Berlin out of the city, and never saw it fall.

He was able to make his way home by August 1915, after nine months via Shanghai, San Francisco, New York, Gibraltar (captured, London as a POW ans later an escapee to Netherlands) and back to Germany. He served for the remainder of the war in the German naval air service ranking as Kapitänleutnant in 1918 and became a well known air explorer after the war, crash in Patagonia in 1931.

The proper attack came the same night, 6-7 November, when waves of Japanese infantry baionet-charged the defenders on their third defensive line, demoralized and almost out of ammunitions. They were overwhelmed and were made prisoners. On the morning, both the Germans and Austro-Hungarian, asked for a formal surrender. After much discussions, the terms were signed on 16 November 1914 when the Japanese (and later British) took possession of the colony. When the latter entered the town in turn, the German prisoners turn their back on them.

During this land campaign, the Japanese lost 733 killed and 1,282 wounded, the British 12 killed and 53 wounded and the Germans 199 dead and 504 wounded. The deads were buried at Tsingtao whiled German POWs were shipped to Japanese camp, some 4,700 prisoners, treated well and with respect contrary to WW2 and after the Versailles treaty, repatriated before 1920. 170 Germans however chose to remain in Japan and made a new life there, not surprising after such a long captivity and time to grasp the complex culture and met local women.

Some were part of the III Marinebatallion band orchestra that toured Japan with their own uniforms in 1914-19, where they became quite popular. Their impression and the contrast with the performances of the Russian added its weight to the future interwar relations between Japan and Nazi Germany and the steel pact.

Aftermath

During the Japanese occupation, the city of Tsingtao was further developed: Used as a base for the exploitation of natural resources in the Shandong and northern China it saw further development of industry and commerce. The Japanese made their mark on the city, creating an entire New City District for Japanese colonists and trade companies.

Alongside new living quarters, schools, hospitals and new public buildings mushroomed. The urban plan was extended and highways constructed while the network of the Tsingtao-Jinan Railway Line and the Tsingtao Railway Station was upgraded and further extended, with new quarters built northward and in the eastern bay.

Bundesarchiv – German Prisoners of War bring back to Wilhelmshaven on SS Kofuku Maru in February 1920 after a six years captivity.

Afterwards, the Paris Peace Conference and Versailles Treaty negotiations at first recognised the Japanese presence by not restoring Chinese rule over Tsingtao but also many other concessions after the Great War. This understandably provoked a vivid resentment in the population which erupted into the May Fourth Movement (May 4, 1919), combining all the Chinese anti-imperialist, nationalists and those advocating for the return of cultural identity in China.

Eventually, the concession of Tsingtao would fell once again under Chinese rule in December 1922, by the takeover by the Republic of China (R.O.C.) established after the 1911 Chinese Revolution.

A Japanese company still maintained its control on railways in the whole province, but the city itself was fully controlled municipality by the in July 1929. Of course imperialistic Japan eventually preyed on the strategic city and re-occupied “Qingdao” as renamed, in 1938, right after the start of the the second Sino-Japanese war in 1937.

Kuomintang forces would seize the city after the Japanese surrender in September 1945. Eventually Qindao will fell on October 1, 1949 into the hands of Chairman Mao Zedong and his troops and is now part of China since.

Admiral Von Spee would eventually fail in his attempt to join the fatherland. After roaming the Indian Ocean, and the Western pacific, winning at Coronel, the fleet was destroyed in the Falklands and the remaining ships eventually hunted and sunk, with some amazing stories like the case of the Emden.

Admiral Von Spee would eventually fail in his attempt to join the fatherland. After roaming the Indian Ocean, and the Western pacific, winning at Coronel, the fleet was destroyed in the Falklands and the remaining ships eventually hunted and sunk, with some amazing stories like the case of the Emden.

Despite the loss of Tsingtao, German propaganda turned it into a valiant defeat, their troops and ships holding two combined, overwhelming forces at bay for two month, sinking enemy ships, downing a plane, and killing four times more Japanese than their own. They bravely maintained their cohesion under an unrelentless barrage which lasted a week, while being outnumbered 6 to 1, fighting literally to the last shell and bullet. This was also praised in Austria-Hungary.

BBC – The siege of Tsingtao – See also: //youtu.be/mfSGqlnvhxc (footage archives and movie extract)

Read More/Src

Österreichs Kriegsmarine in Fernost: Alle Fahrten von Schiffen der k.(u.)k. Kriegsmarine nach Ostasien, Australien und Ozeanien von 1820 bis 1914 (in German). Berlin: epubli. ISBN 978-3844249125.

Edgerton, Robert B. (1999). Warriors of the Rising Sun: A History Of The Japanese Military.

Radó, Antal, ed. (1919). “Csingtao eleste” [The fall of Tsingtao]. A világháború naplója [Diary of the World War

Haupt, Werner (1984). Deutschlands Schutzgebiete in Übersee 1884–1918 [Germany’s Overseas Protectorates 1884–1918].

Veperdi, András. “The protected cruiser SMS Kaiserin Elisabeth in defence of Tsingtao, in 1914”

Schultz-Naumann, Joachim (1985). Unter Kaisers Flagge, Deutschlands Schutzgebiete im Pazifik und in China einst und heute

https://www.nam.ac.uk/explore/siege-tsingtao

https://www.bbc.com/news/av/world-asia-china-29801553/ww1-the-siege-of-tsingtao

https://www.firstworldwar.com/battles/tsingtao.htm

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Siege_of_Tsingtao & Qindao page

https://encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net/article/pacific_islands

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign

Thanks,

This really helped me on my research on battle of tsingtao

You’re welcome !

My grandfather fought in that, for the Germans, and was imprisoned for many years in Tokushima.

Thanks for this precision David !

Indeed the aftermath is little researched. Do you know if he was interned until November 1918 ?

This event is quite strange and when related i often get eyebrows. WW2 alliances habits are so strong that some have a hard time to assume Japan was effectively a member of the entente (and a frustrated one later, to place on par with Italy). No WW2 without WW1 again. This war really started in 1914 and resumed in 1939.