France 1858-1880, Broadside Ironclad

France 1858-1880, Broadside IroncladMarine Nationale's Ironclads

Gloire class | Couronne Bd. Ironclad | Magenta class Bd. Ironclads | Arrogante class Flt. Batteries | Provence class | Embuscade class | Palestro class Flt. Batteries | Taureau | Belliqueuse Bd. | Ocean class | Alma classOrigin of the ironclad concept

The naval staff under the 2nd French Empire (Napoleon III) was concerned after the declining state of the French Imperial Navy after the Napoleonic era crippling losses of Trafalgar, Aboukir and many other battles, plus captured ships, leaving quite a modest force to Louis XVIII. Some experienced admirals and officers which left France during the Revolution returned, and those of the Imperial Navy were seen with suspicion until they proved their new loyalty to the the regime.

After the 1830 revolution and constitutional monarchy, some efforts were put into built large, modern ships of the line whereas the French Empire continued to grow its industrial output, now accessing new resources thanks to its colonial possessions. However constitutional King Louis-Philippe (ruled 1830–1848) was not keen to maintain a powerful navy and that keeping 20 of its 40 1st line wooden ship on dry land, they will not loose their value in case of war. But it was no subsitute for training nor creating a pool of able officers.

Under the French 2nd Empire (14 January 1852), a plan to relaunch the Navy was ordered by Louis Napoleon Bonaparte, president since 1848 after the last revolution. The first product of this renewal was a prototype, the world’s first steam ship of the line, Napoléon. This success led to more conversions and reinvested interest in the navy, let still without any strategic playbook. In fact the new fleet was unable to protect the country in 1870…

Lessons of the Crimean War

Then the Crimean War started in 1853, France committed the bulk of its fleet in joint operations with the British, not only in the Black sea, but around the world, from the Baltic to Vladivostok. By dealing with Russian forts what became clear is the vulnerability of unprotected ships of the line against the latest high explosive and incendiary projectiles.

That is until the French deployed the Devastation class ironclad floating batteries. They were built specifically for the attack of Russian coastal fortifications in this war with ten ordered, but only five completed in French shipyards. Only the first three managed to take part in the attack on Kinburn in 1855, at close range reducing the fort to rumble, taking many hits that achieve nothing.

These 1,600–1,674 t (1,575–1,648 long tons) 53 x 13.35 x 2.65–2.8 m ships were powered by a 150 nhp Le Creuzot steam engine, achieving 4 knots (7.4 km/h; 4.6 mph). For long range crossings they had a sail plan on three masts, with 350 m2 (3,800 sq ft) or sails and a crew of 282. They were armed with sixteen 50-pounder smoothbore guns and two swivel-mounted 12-pounder guns and were protected by iron plating over the whole lenght of the hull above water 110 mm (4.3 in) in thickness.

They were judged so valuable that all five also were used in the Adriatic by June–July 1859 (Italian war).

The crimean war concluded by the allied objectives gained, a peace treaty that basically saved the Ottoman Empire. But the French Naval Staff concluded two things from the conflict. One, a confirmation that steam power combined with a screw propeller was the future, as shown by the intervention of Napoléon, towing a crippled French man-o-war out of harm when there was no wind. And the Devastation class showed than an armoured ship was imperveous to battery fire, and conversely could provoke untold levels of damage to an unprotected target. But the latter has been designed not as pure floating batteries. They were almost rectangular in shape, slow, unwieldy, short ranged, and completely unable to do fleet work.

The idea of a sea-going Ironclad.

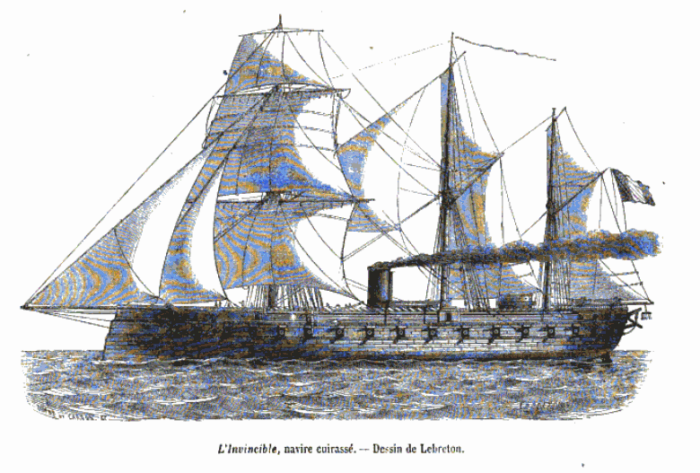

Engineers, notably Breton Henri Dupuy de Lôme (which created the Napoleon steamship), prophetized that a single sea-going broadside ironclad, screw-propelled, could deal with entire fleets. And for this it only needed a single battery, not a two or three deck battery, making it cheaper to build. This was tempting for Napoléon III, which was not thinking of the Royal Navy but rather to the Austrian Navy in his Mediterranean chess game. However the first French sea-going ironclad would have the effect of launching a new Anglo-French naval arms race anyway (see later).

Engineers, notably Breton Henri Dupuy de Lôme (which created the Napoleon steamship), prophetized that a single sea-going broadside ironclad, screw-propelled, could deal with entire fleets. And for this it only needed a single battery, not a two or three deck battery, making it cheaper to build. This was tempting for Napoléon III, which was not thinking of the Royal Navy but rather to the Austrian Navy in his Mediterranean chess game. However the first French sea-going ironclad would have the effect of launching a new Anglo-French naval arms race anyway (see later).

Nevertheless in 1957, since the concept was untested, Dupuy de Lôme requested to start with an existing Frigate, which battery deck would be compatible with his design. The man was gifted with invention, creating with his Friend Gustave Zede, the first electric operational submarine in 1888, and the first armoured railway carriage batteries or a revolutionary airship in 1870.

Jules Verne‘s model for some of its fictional engineer characters.

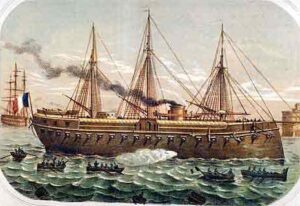

Launch of La Gloire in 1859

In general, the solution was in response to new developments of naval gun technology and particulalry (and ironically) the French-designed Paixhans guns as well as British latest rifled guns, using explosive shells that were now able to reduce wooden ships as matchsticks. Many of the design’s origins also layed in the ironclad floating batteries used in Crimea. After negociating with Toulon, about to lay down a two-decks frigate, he had plans redrawn, notably to reinforce the wooden hull considerably in order to have armoured plates attached, a revision of the waterline and other mosifications. When plans were approved over a new 5,630-ton base, the ship was eventually ordered by the ministry and laid down at Mourillon Dock on 4 March 1858.

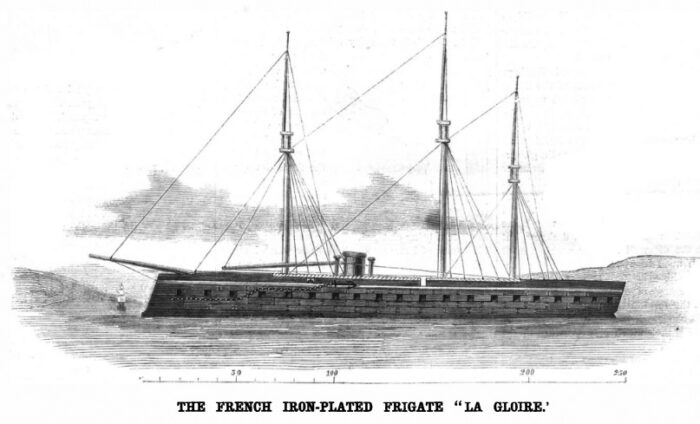

Scientific American Feb.1861 on Gloire:

For 200 years England has been the acknowledged mistress of the scas, but her great rival, France, has looked with ever-increasing jealousy upon this supremacy. During the two years of the French republic, after the overthrow of Louis Philippe, when the government was directly under the influence of the people, this jealousy manifested itself in the appointment of a commission to inquire into the state of the French navy and devise means for its improvement. In the able report of this commission, the position is dis tinctly taken that the object of France in increasing her Navy is to surpass England in this element of power, and during the eleven years which have since elapsed this object has been pursued with remarkable steadiness and vigor, notwithstanding the great change in the government; the politic Emperor shrewdly making himself the agent of the nation’s will in this matter. During the last decade France has created a navy larger than any the nation had ever before possessed.

But while this navy has been in process of creation, the neighboring rival has not looked idly on at the building up of a force for the express purpose of wrestling from her grasp the power which she has so long enjoyed. As France increased her navy, England also increased helps, and thus has been exhibited for the last ten years, the most stupendous efforts for the mastery of the seas that the world has ever seen. As England has about five millions of tuns of mercantile shipping, while France has only about one million, the great superiority of England in sailors as well as in money, must make the efforts of France to surpass her in naval power entirely hopeless.

But while this navy has been in process of creation, the neighboring rival has not looked idly on at the building up of a force for the express purpose of wrestling from her grasp the power which she has so long enjoyed. As France increased her navy, England also increased helps, and thus has been exhibited for the last ten years, the most stupendous efforts for the mastery of the seas that the world has ever seen. As England has about five millions of tuns of mercantile shipping, while France has only about one million, the great superiority of England in sailors as well as in money, must make the efforts of France to surpass her in naval power entirely hopeless.

The concentration of authority in the hands of the Emperor may enable him, by directing the whole resources of the nation upon the effort, to obtain a temporary superiority. It would seem that he is now engaged in such an effort. Some months since, he ordered the construction of a number of large iron plated ships to be finished and ready for sea in the Spring of 1861. The engineer who was appointed to the responsible position of superintendent of their construction, was M. Depuis de Lome. and the result has well justified the wisdom of the selection. He was called upon to construct vessels for novel purposes to be used under peculiar conditions, and after completing his calculations, he boldly laid down the lines for several of these ships, without waiting for the first one to be tested. One of these vessels is finished and has made three voyages, and her brilliant success in

every respect has raised the I’eputation of de Lome to the highest point among the engineers of England as well as those of France.

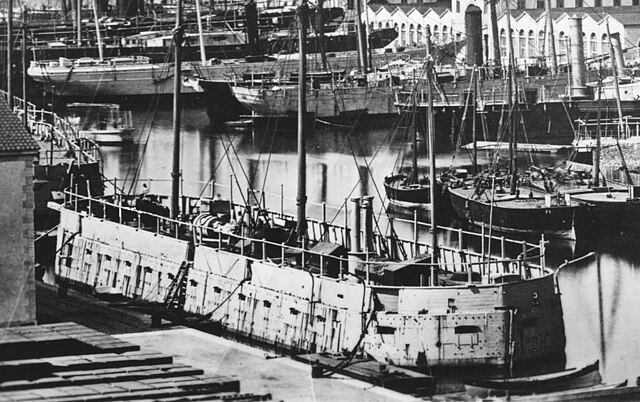

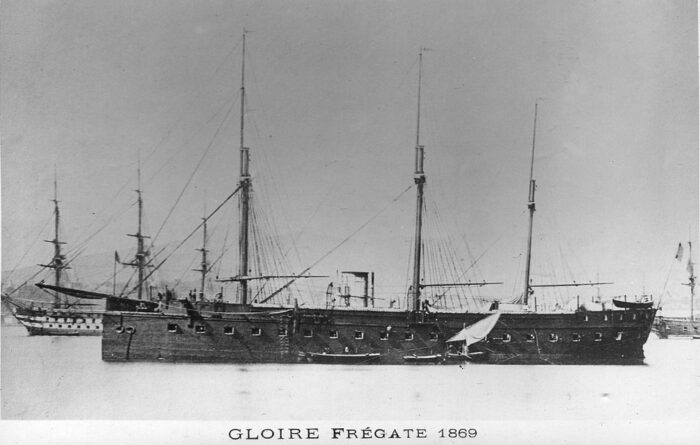

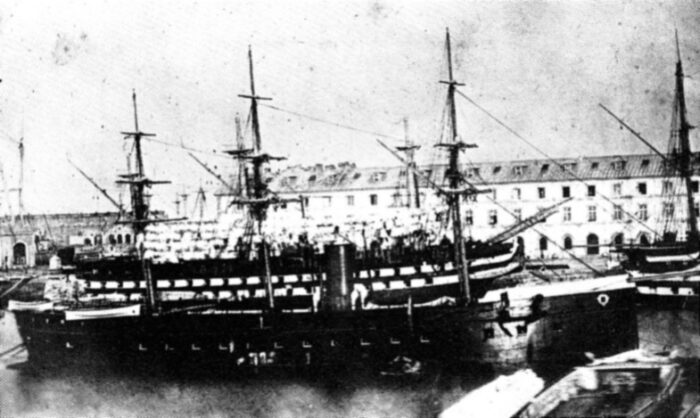

The port of Toulon at the time Gloire was in service

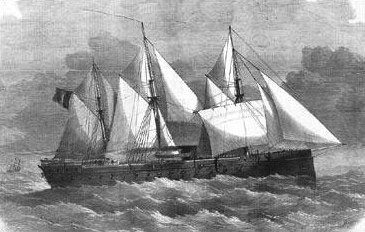

She is named La Gloire, and we herewith present an engraving of her, which we transfer from the London “Mechanics’Magazine”. She is about 250 feet-long, 51 feet wide, and displaces 5,000 tons. Her engines are of 900-horse power. They were huilt at Marseilles by the “Société des Forges et Chantiers. The construction and performance of these engines have so pleased the Emperor that he has named the director of the company, M.Guiguer, Chevalier of the Legion of Honor. La Gloire carries one battery of 34 guns, at a level of only about 6 feet above the sea, and she has 2 long-range guns on the forecastle. On the quarter deck is an iron redoubt, to protect the master at his post. She is built of wood, and entirely covered, above water, with hammered, wrought iron plates, 4 inches thick. We have already given an account of the admilable sailing qualities of this famous ship. She made 13 knots per hour, and averaged 12/.10 knots for 10 hours, a speed which is said never to have been equaled by any other steam frigate…

She is named La Gloire, and we herewith present an engraving of her, which we transfer from the London “Mechanics’Magazine”. She is about 250 feet-long, 51 feet wide, and displaces 5,000 tons. Her engines are of 900-horse power. They were huilt at Marseilles by the “Société des Forges et Chantiers. The construction and performance of these engines have so pleased the Emperor that he has named the director of the company, M.Guiguer, Chevalier of the Legion of Honor. La Gloire carries one battery of 34 guns, at a level of only about 6 feet above the sea, and she has 2 long-range guns on the forecastle. On the quarter deck is an iron redoubt, to protect the master at his post. She is built of wood, and entirely covered, above water, with hammered, wrought iron plates, 4 inches thick. We have already given an account of the admilable sailing qualities of this famous ship. She made 13 knots per hour, and averaged 12/.10 knots for 10 hours, a speed which is said never to have been equaled by any other steam frigate…

Design of the Gloire

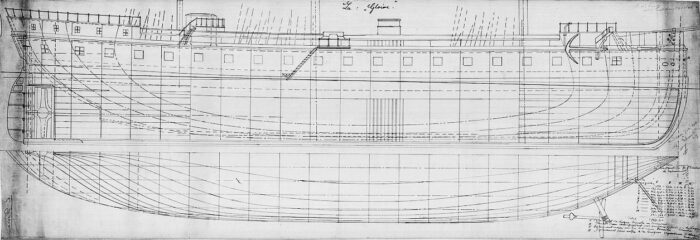

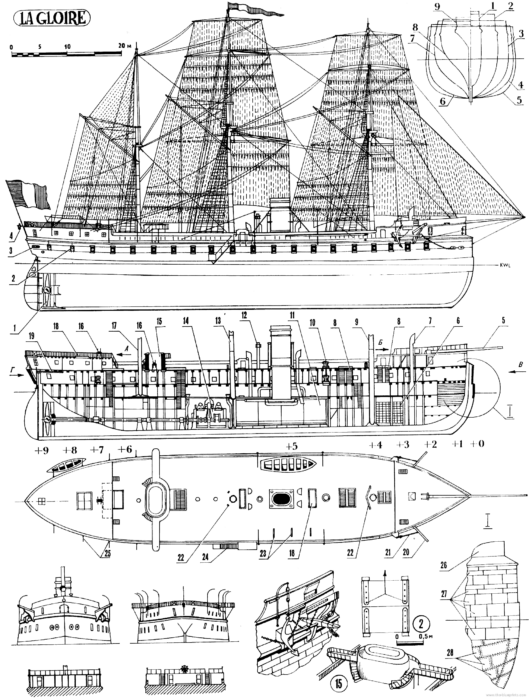

Plans of the ship, now at the US library, NARA

Hull and general design

Designed by Henri Dupuy de Lôme as seen above, the Gloire class were battle ships, more than the British Warrior class, design to act independently or as guardships and looking more like true frigates. The Gloire class were 77.25–78.22 meters long (77.88 meters or 255 ft 6 inches at the waterline for Conways) (253 ft 5 in – 256 ft 8 in). The beam was generous, at 16.99 meters (55 ft 9 in). Maximum draft was 8.48 meters (27 ft 10 in), with an hold depth of 10.67 meters (35 ft) total. They displaced from 5,618 to 5,650 metric tons (5,529 to 5,561 long tons) for quite a high metacentric height of 2.1 meters (7 ft). Due to this, they rolled a lot on trials and in service. The low gun ports at just 1.88 meters (6 ft 2 in) above the waterline was also a grave issue combined with the former, and made them very wet. The crew comprised 570 officers and enlisted men.

Typically for these early ships for which the sailing rig was capital, the decks were very plain, and she had a forecastle and poop deck, whereas the upper batery deck (no guns was installed on it, tall bulwarks covered it) comprised the three masts, with a main capstan between the fore and main masts and a hatch, then the funnel and its base, the separate siren and four dorade boxes (cowl vents) around. Then came the main mast, a new hatch, and the only superstrucvture on deck with the command post and walkway wings on both sides, accessible by two staircases aft at the foot of the aft mast. The coxwain’s helm and steering wheel was located at the start of the poop deck as it ever was, with two more boxes containing flags behind. Officers quarters were located below, with well furnished and wooden panelled interiors, with curtains and rugs and squared framed windows. But there was no gallery. There were also three anchors, tow forward, one aft under davit.

There were a dozen of boats for the nearly 600 strong crew, the whalers and utility barges located abaft the funnel on deck, served by a boom crane. There were two yawls and two pinnaces aft, around the poop deck as well. Both the foecastle and poop were pointy and enclosed by barriers, fully solid and covered forward, open metallic aft. The ram bow was peculiar in its shape with successive steps from the shorter forcastle and rounded below the waterline down to meet the keel. The hull was covered with copper polating just like former generation of wooden warships. Access on board was done via the single starboard access door helped by a lifting ladder and platform hanginf from a spar.

Armour protection layout

The fact she was built from a wooden hull, not an iron one, made some authors speaking of her as a “semi-ironclad”. But most authors continue to place them among broadside ironclads for simplicity due to the number of converted wooden ships that flourished after 1860 far more actually than all iron built ships, a bit of luxury mostly made in Britain.

Gloire and her sisters had a completely armoured wooden hull:

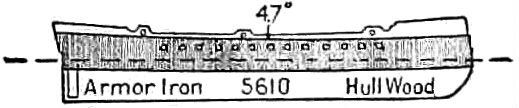

The belt comprised wrought iron plates 120 mm (4.7 inches) thick, backed by the 760 mm to 800 mm (30 inches) teak planking, part of the original wooden armour, extending 5.4 meters (17 feet 9 inches) above the waterline, two meters (6 feet 7 inches) below it.

The Battery was protected by 110 mm iron plates (4.3 inches) on 660 mm (26 inches) wooden backing.

There was no lighter tapering above, rather the main deck’s bulwarks were left unprotected. The plates were all riveted, which was a source of rust.

The only other armoured part was the open-topped “conning tower” aft, protected by 100 millimeters (3.9 in) thick walls over 3.7 meters high, and 10 millimeters (0.4 in) underneath the wooden upper deck. It was used as a backup steering and command post.

In addition, Invincible and Normandie apparently were built in emergency, with unsound timber, completely rotted after less than ten years of service.

Powerplant

The Gloire class had a single horizontal return connecting-rod compound (HRCR) steam engine installed, driving a single six-bladed, 5.8-meter (19 ft) propeller. On profile it looked like a 2-bladed one hence some confusion in some sources, albeit photos shows a 4-bladed one. This steam engine was fed by eight Indret oval boilers, with a total a capacity of 2,500 indicated horsepower (1,900 kW). Her sea trials showed a top speed above 13 knots (24 km/h; 15 mph), a figure which was the baseline contracted speed. They carried 675 metric tons (664 long tons) of coal for a range of 4,000 kilometers (2,500 mi) at cruise speed or 8 knots (15 km/h; 9.2 mph). Their initial light barquentine rig seen on engravings based on three masts was worth 1,100 square metres (11,800 sq ft). It was judged unsufficient and soon changed. This first rigging was rather light, schooner type with main and topsails, a square foesail and two-part masts. This was in contrast to the Warriors which had a full barque rig, but were poor sailships anyway, with little agility. The Gloire and sisters, as well as the very similar Provence class however later received a barque rig and the appearance diverged on depictions and engravings, which was 2,500 square meters (27,000 sq ft). Later however it had to be reduced because of excessive rolling.

Armament

Initially thirty-six, Modèle 1858 164.7 mm (6.5 in) 17 caliber rifled muzzle-loading guns (RML): Fourteen per side on the main battery deck, fully protected, two pivots mounts forward, four pivot mounts as chase guns. The remaining two guns were located on the upper deck, chase guns. All these guns fired a 44.9-kilogram (99.0 lb) shell at 322 meters per second (1,060 ft/s). They were ineffective against armour and considered a stopgap solution.

They were replaced in 1868 by proper rifled breech-loading Modèle 1864. In addition, they received four 194 mm (7.6 in) and eight 240 mm (9.4 in) guns in the middle of the gun deck and two more 194 mm (7.6 in) as upper deck chase guns. To be exact, Gloire in 1863 already had all her main guns replaced by thirty-four 165mm/15 M1860 BLR. The next year she lost two of these 165mm/15.

In 1867 she was armed with an addition of six 240mm/18 M1864 BLR, and two 194mm/19 M1864 BLR.

Her sisters were armed the same, but rearmed as well in 1864 for Invincible with thirty-two 165/15 M1860 BLR and Normandie skipped that and went directly to twelve 194mm/16 50pdr SBML, and sixteen 165mm/15 M1860 BLR in 1865.

In 1868, both sisters had a final armament of eight 240mm/18 M1864 BLR, and six 194mm/19 M1864 BLR like Gloire.

Author’s illustration.

Fully monty depction, from the blueprints.com

⚙ specifications (1860) |

|

| Displacement | 5,618 t (5,529 long tons) |

| Dimensions | 78.22 x 17 x 8.48 m (256 ft 8 in x 55 ft 9 in x 27 ft 10 in) hold 10.67 m (35 ft) |

| Propulsion | 1× Shaft HRCR-steam engine, 8 oval boilers, 2,500 ihp (1,900 kW) |

| Speed | 13 knots (24 km/h; 15 mph) |

| Range | 4,000 km (2,500 mi) at 8 knots (15 km/h; 9.2 mph) |

| Armament | 36 × 164 mm (6.5 in) Mle 1858 rifled muzzle-loading guns |

| Protection | Hull 120 mm (4.7 in), Conning tower 100 mm (3.9 in) |

| Crew | 570 officers and enlisted men |

Career of the Gloire class Ironclads

Gloire (1859)

Gloire (1859)

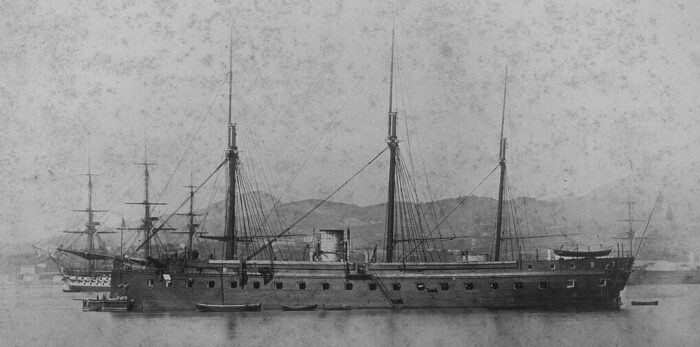

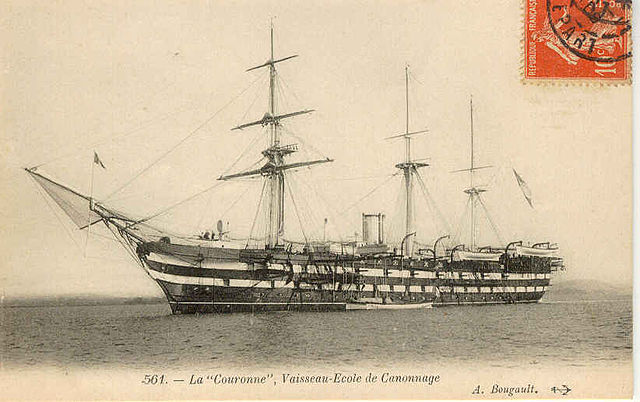

Gloire was laid down at Arsenal de Toulon on May 5, 1858, she was launched on 24 November 1859 and completed on august 1860. A bit like the Warrior class, all three sisters had very uneventful lives, kept as a “master ace” for a few years, but their mixed construction and stability issues did not fare well. La Gloire was never engaged in any naval combat, even during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-18715. She was rearmed, yet still, Overtaken fairly quickly technical progress and central battery ironclads, then turreted ones about ten years after she was laid down. She was base din the Mediterranean with her sisters in Toulon for more of her service until stricken in 1879, scrapped in 1883. Despite she was rearmed in 1867-68 an inspection revealed her wooden hull already deteroriated badly and by 1872 she was placed in reserve already. Her sister ship “La Couronne” was the first French ironclad entirely built in iron, and like the Warrior class, shewas not condemned until 1933. Both sisters were built from unseasoned wood that deteroriated faster and their career was even shorter.

Invincible (1861)

Invincible (1861)

Ordered on 4 March 1858, Invincible was laid down at the Arsenal de Toulon on 1 May 1858 and launched on 4 April 1861, completed in March 1862. By September–October 1863 she started her tactical trials with other ironclads. She was assigned to the Mediterranean Fleet, and made a port visit in August 1865 to Brest, Atlantic coast, as the fleet hosted the British Channel Fleet. While festivities took on, Invincible invited guests of the RN, a banquet for midshipmen of both fleets, reportedly the noisiest and most enjoyable of the visit. A few days later the French fleet visited Portsmouth in return, hosted by the Channel Fleet. There are conflicting records for her action in the During the Franco-Prussian War in 1870–71. She was sent to defend the islands of Saint Pierre and Miquelon from Prussian commerce raiders. However Wilson claims she was assigned to Vice Admiral Léon Martin Fourichon’s squadron blockading German ports in the Heligoland Bight while Gille and de Balincourt as well as Vincent-Bréchignac maintained she was instead sent to the North America station, close to Canada as stated above.

She was modernized (see above) for her main armament twice but was built of unseasoned timber which degradred rapidly. Upon inspection in 1871 she was in poor shape upon her return that was decommissioned outright, kept for possible alteaitons and then condemned on 12 August 1872, scrapped in 1876 at Cherbourg for a career of just nine years, not worth her cost.

Normandie (1860)

Normandie (1860)

Named after the province of Normandy, an idea that would resurface while naming the follow-up Provence class, Normandie was ordered around September 1858, six months after her sisters an at Arsenal de Cherbourg on the Atlantic Coast. Laid down on 14 September 1858, she was launched on 10 March 1860, completed on 13 May 1862.

In July 1862, Normandie became the first ironclad to cross the Atlantic as flagship, Vice Admiral Edmond Jurien de La Gravière to support Napoleon’s III ill-fated French intervention in Mexico. By April 1863 she was back due to an outbreak of yellow fever, killing her captain, some of the staff and crew. She was then assigned to the Mediterranean Fleet as her sisters (poor seaworthiness made them more suitable here). She still made a port visit in August 1865 to Brest like her sister when the Marine Naitonale hosted the British Channel Fleet. A few days later she was in Portsmouth where for a reciprocating visiting to the Channel Fleet.

From 1865 to 1868, Normandie joined the “Evolutionary Squadron” under command of Bernard Jauréguiberry, a later famous admiral. She was assigned to the ironclad squadron, commanded by Rear Admiral Didelot in the Franco-Prussian War, but saw no action and was kept in home waters. Like her sister, she was built of unseasoned timber and when examined in 1871 after her sister, she was soon found in qually poor shape after the war. She was thus decommissioned on 17 June 1871 and condemned on 1 August, stricken, broken up, her still valuable engine installed in the breastwork monitor “Tonnerre”.

Legacy: An Anglo-French ironclad race ?

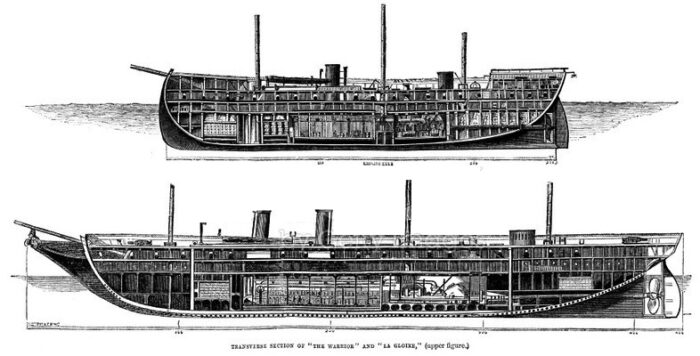

Comparison between Gloire and Warrior, with cutaways

Dupuy de Lôme, Director of Material since 1 January 1857, wanted a synthesis of ideas in the air of the time and from an extrapolation of his “Napoléon”, first steamship of the line. Plans for the Gloire were born to restore balance of maritime forces in favour of the French Navy, putting an end to the supremacy of the Royal Navy. Convinced that in an engagement between two ships equal in speed, armour, nautical qualities and range, the smaller would have the advantage, Dupuy de Lôme wanted “the smallest dimensions possible”. He also wanted a new built hull, not just a existing ship. The core wooden hull would be propeller driven by a 900 hp steam engin and roughly, of the size of an Algésiras-class frigates. His 12 cm thick wrought iron plating was radical, and to compensate for this extra 820 tonnes of armour, a removed the upper battery kaaping “only” thorty six 30-pounder rifled cannons in a lower main battery, fully protected. The rigging was much reduced and seen as a simple auxiliary. The configuration chaged from a three-masted schooner to a three-masted barque and ended as a three-masted square-rigger with only the foremast fully rigged.

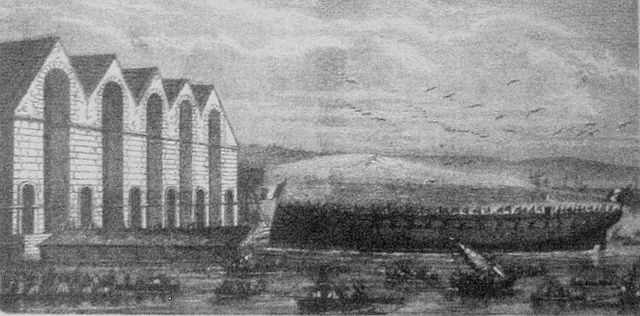

“La Courronne”, near sister-ship of Gloire was built on a brand new plan on a two deck configuration, unlike Gloire, converted.

Napoleon III was submitted these plans and immediately ordered construction of three ships without even consulting naval authorities. Whe she emerged for completion in Mourillon arsenal, Gloire had been under work for twenty-three months and in trials by 1860, gave full satisfaction, with a top speed of 13.5 knots comparable to that of ocean liners. However she had flaws, rolling badly in heavy seas and being a poor seaboat in more sea conditions, requiring portholes of the single battery being shut most of the time. It still outclassed all existing vessels of the time, an undeniable technological breakthrough keeping the French Navy ahead of the curve, if not still capable of equalling the RN notr its gargantuan industrial capacities.

On the British side, the French initiative, known already in 1858 was initially judged too costly. But soon HMS Warrior was built anyway, and in the meantime, Navy Minister Hamelin in France ordered the construction of three new armoured frigates based on these plans on 4 March 1858, Invincible in Toulon, Normandie in Cherbourg, Couronne in Lorient, later revised to be built entirely of iron, and an answer to the Warrior class.

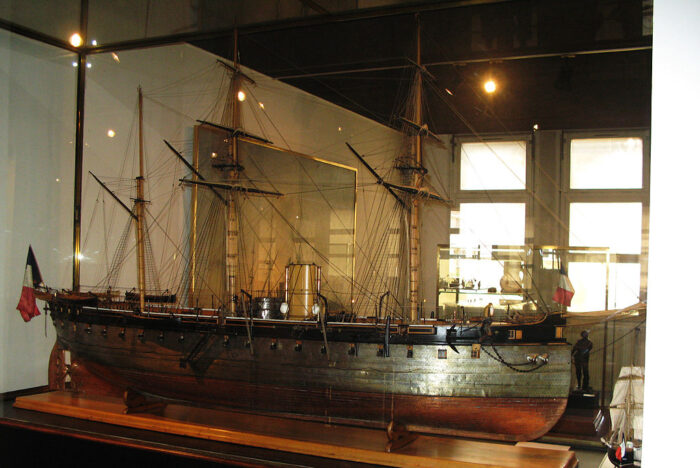

Model of the Flandre, virtually identical to Gloire

The most immediate follow-up of the Gloire class was a large class of copies of Gloire, all built from wooden hulls as the contracted yards had no experience in iron-made hulls.

These were Flandre (Arsenal de Cherbourg) started on 28 January 1861, comp. May 1865, Gauloise (Arsenal de Brest) on 24 January 1861, comp. December 1867, Guyenne (Arsenal de Rochefort) 11 February 1861, comp. 6 November 1867, Héroïne (Arsenal de Lorient) 10 June 1861 comp. 7 June 1865, Magnanime (Arsenal de Brest) 27 February 1861 comp. 1 November 1865, Provence (Arsenal de Toulon) March 1861 comp. 1 February 1865, Revanche, same 28 December 1865, comp. 1 May 1867, Savoie same 29 September 1864 comp. 19 November 1888, Surveillante (Arsenal de Lorient) 28 January 1861 comp. 21 October 1867 and Valeureuse (Arsenal de Brest) 23 May 1861 comp. 25 March 1867. Most were stricken in the 1880s. Experience with Invin,cible and Normandie led to be very cautions about the wood to be used, ensuring a longer service, however they were soon obsolete.

Read More/Src

Books

de Balincourt, Captain & Vincent-Bréchignac, Captain (1974). “The French Navy of Yesterday: Ironclad Frigates, Part I”. F.P.D.S. Newsletter.

Campbell, N. J. M. (1979). “France”. In Chesneau, Roger & Kolesnik, Eugene M. (eds.). Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships 1860–1905.

Gardiner, Robert, ed. (1992). Steam, Steel and Shellfire: The Steam Warship 1815–1905. Conway’s History of the Ship.

Gille, Eric (1999). Cent ans de cuirassés français [A Century of French Battleships] (in French). Marines.

Jones, Colin (1996). “Entente Cordiale, 1865”. In McLean, David & Preston, Antony (eds.). Warship 1996, Conway.

Roberts, Stephen S. (2021). French Warships in the Age of Steam 1859–1914: Design, Construction, Careers and Fates. Seaforth Publishing.

Roche, Jean-Michel (2005). Dictionnaire des bâtiments de la flotte de guerre française de Colbert à nos jours. Retozel-Maury Millau.

Silverstone, Paul H. (1984). Directory of the World’s Capital Ships. New York: Hippocrene Books.

Links

European Ironclads 1860–75: The Gloire sparks the great ironclad arms race. Angus Konstam (Author), Paul Wright (Illustrator)

on article of Scientific_American Series 2 Vol. 004 Issue 07 1861 (pdf)

on navypedia.org/

on en.wikipedia.org/

on fr.wikipedia.org/

on ltwilliammowett.tumblr.com

more photos on commons.wikimedia.org/

Videos

Model Kits

only known kits on scalemates.com/

There had been several scratchbuilt made, and hell, it should not be difficult on paper.

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign