USS Monitor (1862)

First of the name & defining a type: The Monitor

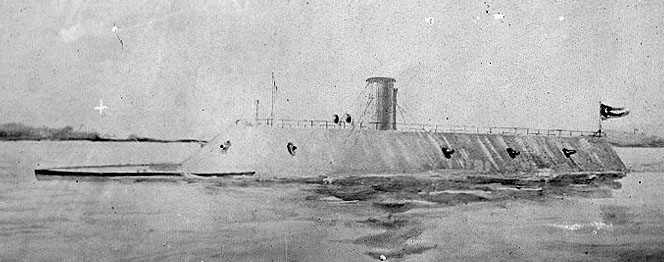

The USS Monitor is not only an icon of the American civil war, a symbol of the industrial north, but it also defined a genre, a type that found use until recent times. The USN still deployed monitors to combat the Viet-cong in the Mekong deltas and its numerous tributaries a hundred years later (☍ see page). But in 1862, the USS Monitor was very much a “secret weapon” designed to counter another (The former USS Merrimack, transformed into the CSS Virginia). The whole blockade of the southern economy depended on it. Off Hampton roads on 8 March 1862, both would fight a largely indecisive duel, the first in history for ironclads. The rest of her career was short, as she was lost at sea during a storm, on 31 December 1862 (off Cape Hatteras, North Carolina), the weight of her contribution could not be underestimated.

Legacy

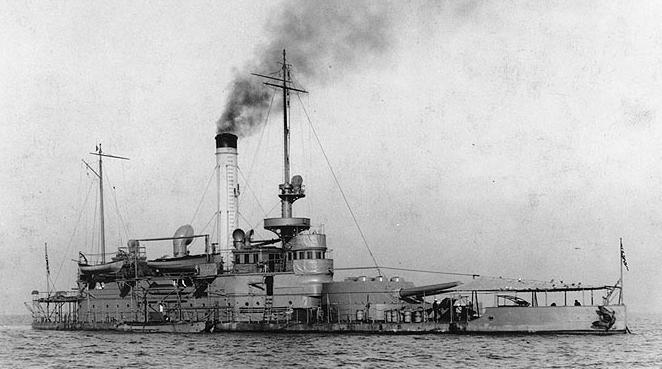

USS Ozark (M7), former Arkansas renamed by 1909. The last classic USN Monitor.

The marriage of heavy guns in a turret and a shallow-draft armored hull represented such a technological step for the time, that it was fully embraced by the Union to counter possible threats of more confederate ironclads, to the point that no less than nearly fifty more were ordered, and most completed before the war ended: USS Roanoke, USS Onondaga, the Passaic class (ten ships), Miantonomoh class (four), USS Dictator, USS Puritan, the Canonicus class (five), and four more in construction by 1865, but also 24 Shallow draught monitors of the Milwaukee & Casco class built 1864-65. The US also exported the concept far and wide, as it was adopted by many other nations as well, sometimes combined into other concepts like the ram, or influencing the late 1870s central breastwork monitors, ancestors of the pre-dreadnoughts; So popular were monitors that they were still listed in the USN in 1917 (Arkansas-class, 1900), others were built by the Royal Navy to deal with the flanders front, or the Italians on the Isonzo front, and still saw action in WW2 (Like the HMS Roberts, discarded in 1965).

Ideas in the air

French floating battery Devastation in Crimea

Before the USS Monitor was conceptualized, there were already several ideas looming in the air among engineers interested by ballistics and steel alike. Armour protection was relatively new in 1850 but uring the Crimean war, the mixed-protected (sandwiched teak wood and specially treated steel) French armoured batteries deployed showed encouraging signs for believers that ships can defeat traditional fortifications. Processes were further worked out until the Gloire was out in 1859, just prompting the British Admiralty to go further with the Warrior class. So in April 1860, when Charleston harbor was shelled, sea-going armoured ironclads were already a thing in Europe, but just.

The science of ballistics reflected the trust made in new projectiles: Until 1860, the standard artillery shot was the cannonball. Its path was unpredicted, causing engagements to be almost point-blank. In Crimea however, the “shell” itself did not changed, but ideas about a practical rifled breech loading weapon was born as well, as reshaping the spherical shell into a cylindro-conoidal form. In 1855, industrialist William Armstrong was awarded a contract to produced a new rifled artillery piece at the Elswick Ordnance Company and Royal Arsenal, Woolwich.

This too, was known in 1860, although only a few British guns had been imported, the immense majority of artillery still relying on smoothbore muzzle-loaders, at any caliber. The armies still trusted the venerable “Napoleon” 6 or 12-pdr, but rifles with the minie bullets started to equip sharpshooter units.

The other revolution in the air was the gun turret. In the 1850s, guns were placed in batteries, guns were placed on rolling cradles with elevation but little traverse, if any. The entire ships manoeuvered to put their guns to the correct bearing. This defined manoeuvers and the type of ranged battles since the XVIth century, and was still a thing in 1860. But durung the Crimean war, designs for a rotating gun turret were first drafted by Captain Cowper Phipps Coles, which had the idea to construct a raft with ‘cupolas’ protecting guns. His experimental raft was to named “Lady Nancy” and the idea was to use it to shell the Russian town of Taganrog (Black Sea). His “Lady Nancy” was indeed built and proved its worth. Back in homeland, Coles patented his rotating turret.

More crucially, The British Admiralty ordered in 1859 such system to be installed onboard the ironclad floating battery HMS Trusty for trials in 1861. His idea to allow the greatest possible all round arc of fire as low in the water as possible were really instrumental to understand the personal engagement of John Ericsson in the whole process. Later, the British Navy laid down HMS Captain, the first ocean-going turret ships.

Genesis of the design

The need for iron plating was first trigerred by the Paixhans gun, put to great use, notably at Sinope against the Turks in the 1820s. Combined with better steam propulsion, it was possible in the 1850s to built armored ships that would not be stuck immobile by their own wieght. Developments in gun technology meant in 1850 that no wooden protection could withstand a modern shell and in 1854 already, the USN tested these iead with the steam-powered Stevens Battery, which work was much delayed while its own design Robert Stevens died in 1856. Without pressing need for this ship at the time, work never resumed and the battery was left unfinished. But in Europe, it progressed well after the Crimean war.

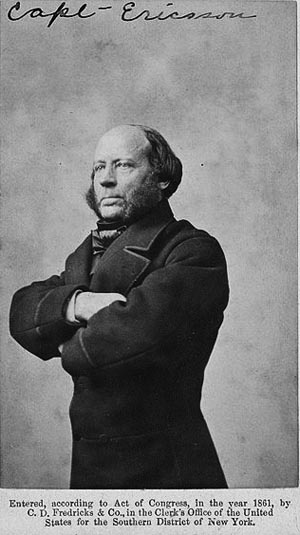

Enters John Ericsson

Swedish-borne engineer, John Ericsson (born July 31, 1803) was instrumental in this history. The extraordinary skills of the two Ericsson brothers were discovered by Baltzar von Platen (1766–1829), architect of Göta Canal, which hired them with success to solve many technical issues as ‘cadets of mechanics’ of the Swedish Royal Navy. John was just 14 at that stage. At 17 he started a military career, with the Jämtland Ranger Regiment, as Second Lieutenant and Lieutenant. While in the far north he constructed a heat engine, which worked very well. Advised to do so by his superiors and friends, he moved in Britain to perfect his engineering skills, and worked on steam propulsion, and early railway applications. His first prototype in 1826 was not a success however as it was designed to burn birchwood, which did worked well in Britain.

Swedish-borne engineer, John Ericsson (born July 31, 1803) was instrumental in this history. The extraordinary skills of the two Ericsson brothers were discovered by Baltzar von Platen (1766–1829), architect of Göta Canal, which hired them with success to solve many technical issues as ‘cadets of mechanics’ of the Swedish Royal Navy. John was just 14 at that stage. At 17 he started a military career, with the Jämtland Ranger Regiment, as Second Lieutenant and Lieutenant. While in the far north he constructed a heat engine, which worked very well. Advised to do so by his superiors and friends, he moved in Britain to perfect his engineering skills, and worked on steam propulsion, and early railway applications. His first prototype in 1826 was not a success however as it was designed to burn birchwood, which did worked well in Britain.

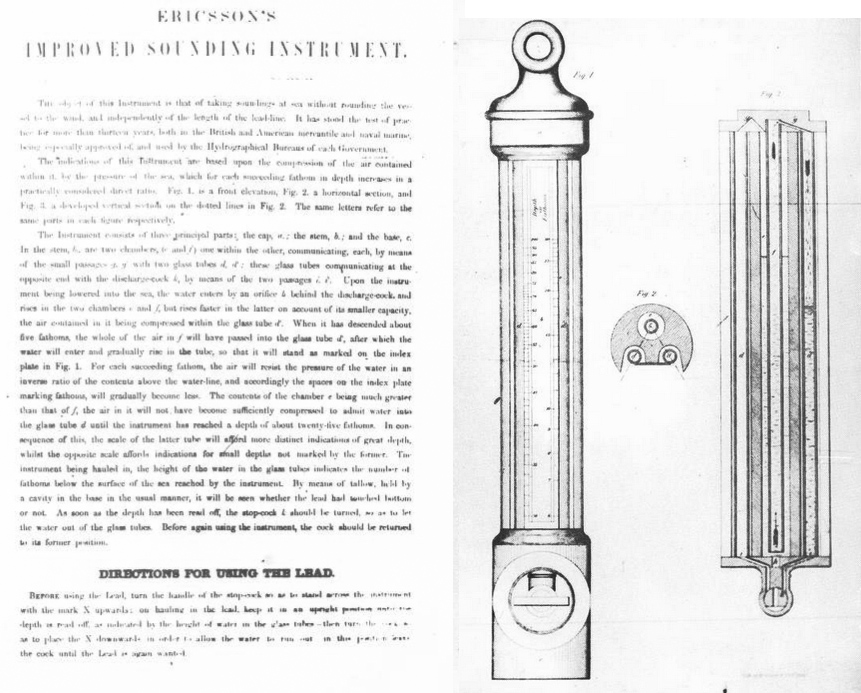

He invented several other mechanisms with bellows to increase the oxygen supply and in 1829 associated with John Braithwaite (1797–1870) for the Rainhill railway Trials on the Liverpool-Manchester Railway but lost the competition to George and Robert Stephenson with their “Rocket”. New prototypes were more successful, using a blower for ‘Induced Draught’ as shown on new railway tests. However they were able to quell the Argyll Rooms fire in 1830, working for five hours straight. One was purchased by Sir John Ross for his Arctic expedition. Ericsson patented notably a surface condenser working with recovered fresh water at sea, avoiding to use saltwater. He also patented a pressure-activated fathometer, but his commercial failures and development costs had him eventually jaied for debts. Both this and a failed marriage pushed him to move to the US, but not before he attempted to sell to the admiralty his patented Propeller design. This also failed, and through one custmer of his design, American captain Robert Stockton he was persuaded to move to the US.

He moved to New York in 1839 and Stockton co,nvinced him to oversee the development of a new class of frigate. The arrangement was a classic one with the trader and the engineer, but it did not fare well with Ericsson which soon felt betrayed as Erisckson revendicated paternity of the designs. Nevertheless, he designed a sloop that eventually became USS Princeton for the USN (1843). The ship was revolutionary, with twin screw propellers, a collapsible funnel, and mouting a 12-inch muzzle-loading gun place on a revolving pedestal (with an innovative recoil system). Not yet a turret, but already with full traverse. Unfortunately, during a firing demonstration of her gun, the breech ruptured, killing Secretary of State Abel P. Upshur and Secretary of the Navy Thomas Walker Gilmer, while Stockton tried to pass the blame on Ericsson and refusing payment.

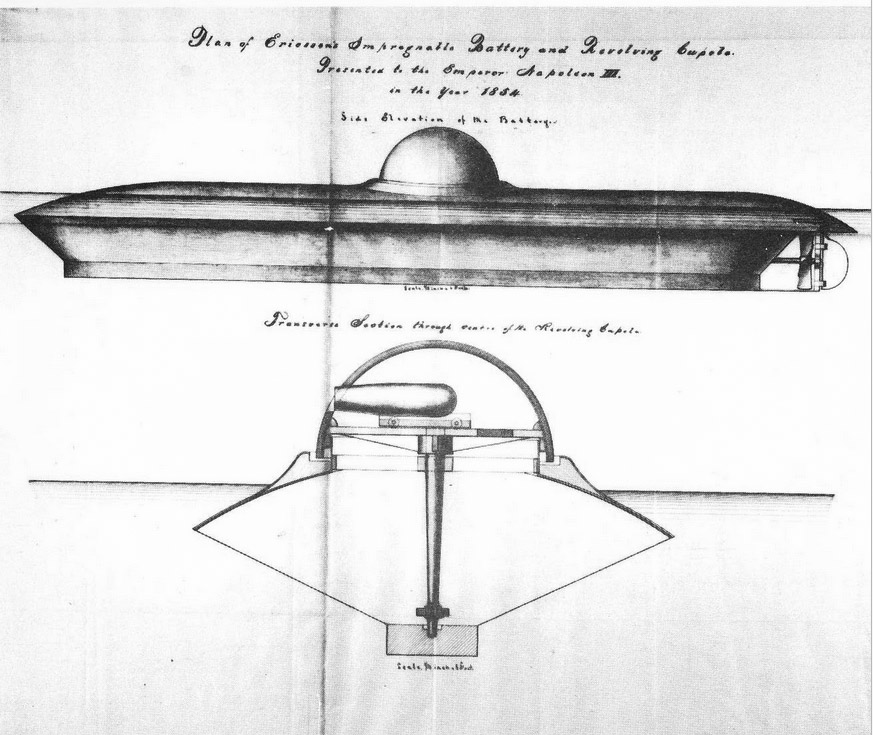

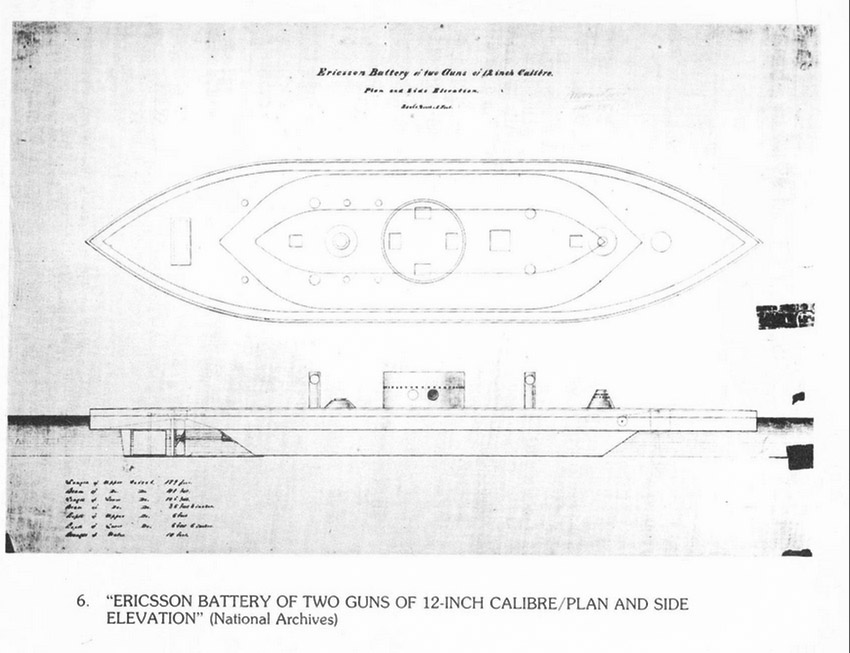

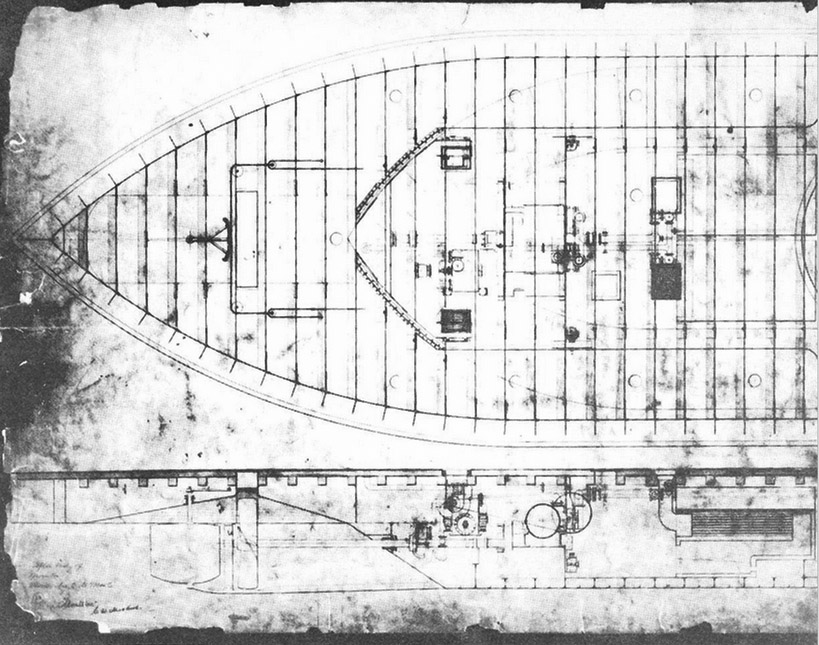

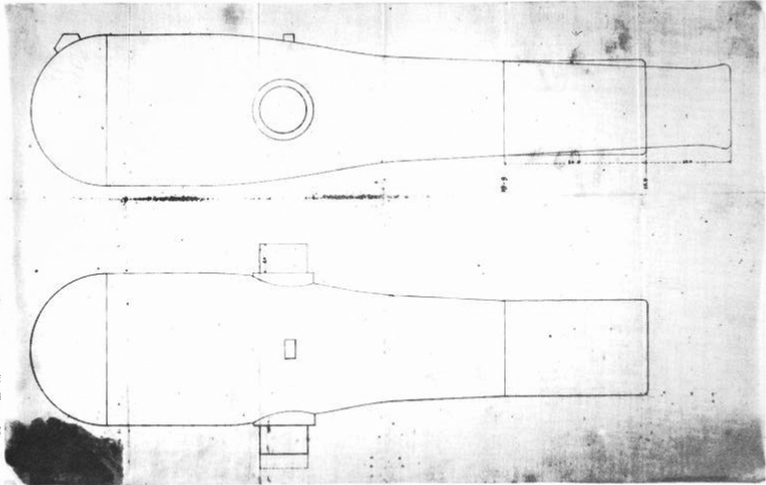

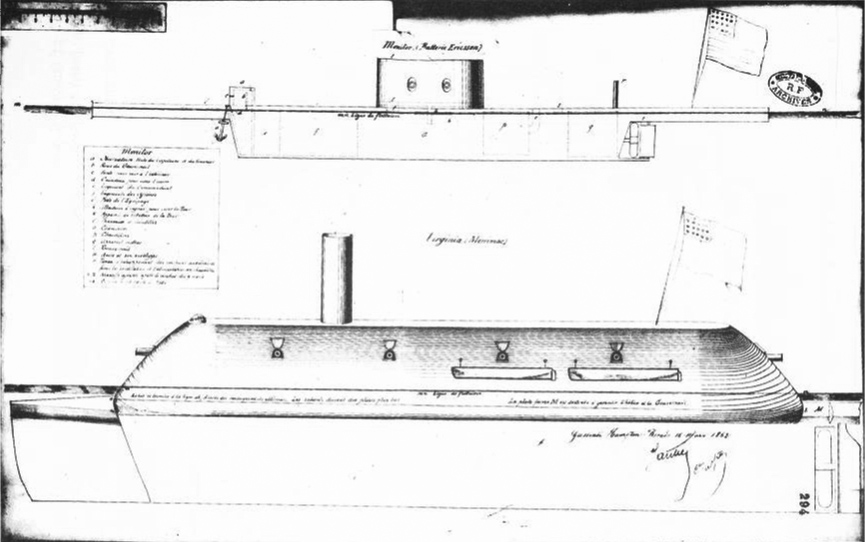

Early proposal draft by Ericsson. Note this was ideal, but not realistic even for the Industrial Union: The cupola was apparently a very large casting, and the turtle back hull (also on USS galena) was destined to make cannonball and shells bounce, extending far underwater where water itself protected the ship’s underbelly. Also interesting is the turret resting in a needle axis, planted in a solid keel, ideas that went into the final design.

Nevertheless, he also associated with industrialist Cornelius H. DeLamater (1821–1889) and together they created the “Iron Witch” first iron steamboat, then the ship Ericsson, and in the 1880s, a submarine, a self-propelled torpedo, and a torpedo boat. In between, Ericsson wanted to propose the USN a new type of ship, and claimed to have sent the French Emperor Napoléon III a proposal for a monitor-type design already in September 1854 (this was never confirmed). Until the, Eriscsson lived on his patents on the Hot air engine, and built the “caloric ship” powered by the 4th Ericsson engine in 1852. His invention made him wealthy as this was a safer, boilerless design, more practical and compact for many applications. He would go on until the 1880s with others, more advanced engines including a solar one.

The war breaks out, Merrimack is being converted

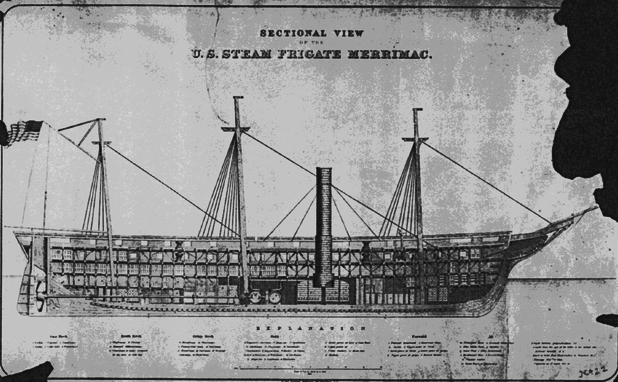

USS Merrimack plan in 1855

The Union Navy, previously rebuffed by Ericsson’s quick temper and the souvenir of the gun explosion on USS Princeton changed its attitude towards ironclads as the war broke out, when learning the Confederates were converting the captured USS Merrimack, into an ironclad at Norfolk in Virginia.

There were knowlegeable engineers indeed in the less industrialized southern states, and strong connection with Europe, Britain and France. Whereas the Union soon set in motion their blockade to cripple the Confederacy trade, create and arms embargo and collapse its economy, some like Lt. John Mercer Brooke though to convert the burn down USS Merrimack into an ironclad, as they were made in Europe, in order to break the blockade.

USS Merrimack was a large, very capable 84 m long 3,200 tonnes frigate with two decks and 40 guns, built in 1854-56. Burnt and sunk in dock on 20 April 1861 after seeing little service since February 1860s, she was large enough for such endeavour and her steamplant was still intact as well as her artillery. Spies in Virginia knew this was an ironclad due to preparation mades with mixed iron plates. John Mercer Brooke wanted a composite armor sloped very close to the waterline in order to deflect any incoming shells. it was made of 4 inches (102 mm) of iron armor, backed by 24 inches (610 mm) of wood. The battery was reduced compared to the original, made to match the few portholes along the armoured casemate: Two 7-inch (178 mm) Brooke rifles, two 6.4-inch (160 mm) Brooke rifles, six 9-inch (229 mm) Dahlgren smoothbores and on the deck, two 12-pounder (5 kg) howitzers. CSS Virginia would be commissioned on 17 February 1862.

css virginia 1862

The United States Congress recommended in August 1861 that armored ships be built for the American Navy, and soon, this encounter a regained interests for Ericsson previous designs. He was met again by representatives of the USN and asked to submit his own design as quickly as possible. Completion of the project was made more urgent by the fear of a deployment to Hampton Roads of the Confederate ironclad Virginia. In theory the latter was impregnable and would have sunk all blockading Union ships as well as bomber Union cities along the coast. Northern newspapers were well aware of the race, and published regular updates on the supposed Confederates progress, which further the Union Navy to complete the Monitor. Ericsson was not alone to (later) answer the call of the Congress, with a appropriated $1.5 million on 3 August 1861: Cornelius Scranton Bushnell also presented his own design.

The competition

After Congress appropriated fund to built one or more armored steamships, a board was created to evaluate the proposed designs. The Union Navy advertised it seeked “iron-clad steam vessels of war” on 7 August. Welles appointed three senior officers to the Board on the 8th,consideringmostly delays and costs. At first, Ericsson made no submission to the board. Instead he teamed with Cornelius Bushnell, well known sponsor of the proposal, later to be known as the armored sloop USS Galena. The board required from Bushnell the boat would float despite the armor, and was advised by Cornelius H. DeLamater to seek out help from Ericsson.

After Congress appropriated fund to built one or more armored steamships, a board was created to evaluate the proposed designs. The Union Navy advertised it seeked “iron-clad steam vessels of war” on 7 August. Welles appointed three senior officers to the Board on the 8th,consideringmostly delays and costs. At first, Ericsson made no submission to the board. Instead he teamed with Cornelius Bushnell, well known sponsor of the proposal, later to be known as the armored sloop USS Galena. The board required from Bushnell the boat would float despite the armor, and was advised by Cornelius H. DeLamater to seek out help from Ericsson.

A meeting took place on 9-10 September, time for Ericsson to evaluate the design. Ericsson at the end showed Bushnell a model of his own design (his 1854 armored raft he “proposed” to the French Emperor). Bushnell did not approve the boldness of the design but recopignised the merit of it and obtained permission for Eriscson to show his model to Welles. After this, the latter recomended he showed it to the board. Upon review hpwever the latter was skeptical over her seaworthiness (which proved right, see later). They rejected the proposal of this completely iron laden “cheseebox on a raft”.

President Lincoln himself however examined the design and overruled them. Ericsson gave guarantees to the board his ship would float by stating (“The sea shall ride over her and she shall live in it like a duck”), and on 15 September, after final deliberations over cost and delay (Ericsson’s were both smaller like the Galena) the board accepted his proposal, to the dismay of Bushnell, although his armored sloop will be also approved and built). The Ironclad Board evaluated 17 different designs in all (notably William Norris’s 90-ton steam ironclad gunboat, and up to Edward S. Renwick’s 6,520-ton ironclad), recommending three on 16 September in the procurement act, including Ericsson’s and Bushnell’s.

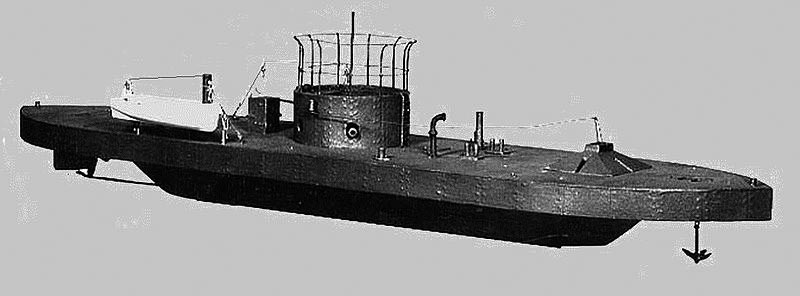

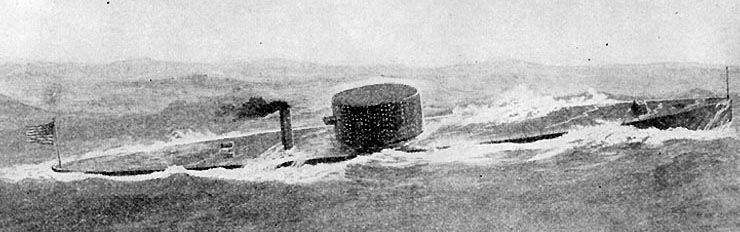

USS Monitor seemed the most innovative with her low freeboard, shallow-draft iron hull, total dependence on steam power, and revolving turret instead of a battery. The latter was riskier, it was the only of such proposals, something not even tested by the European navies at the time. But what took the cake was Ericsson’s assurance of delivery within 100 days. It overcame all the risks involved.

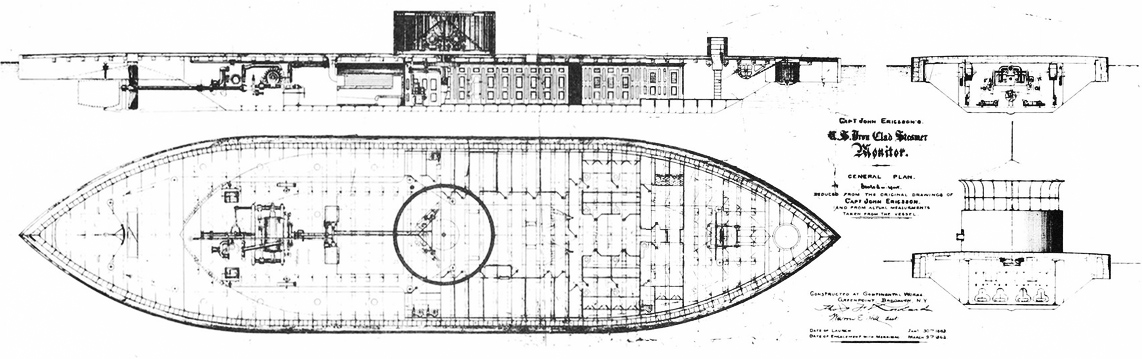

Design of USS Monitor

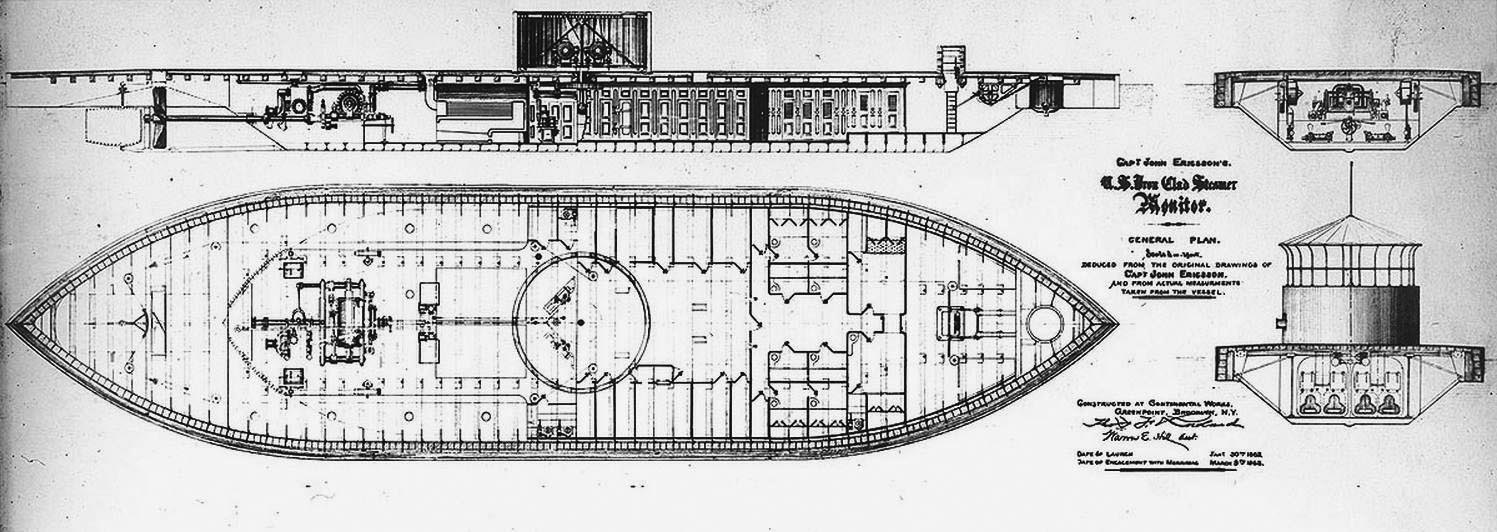

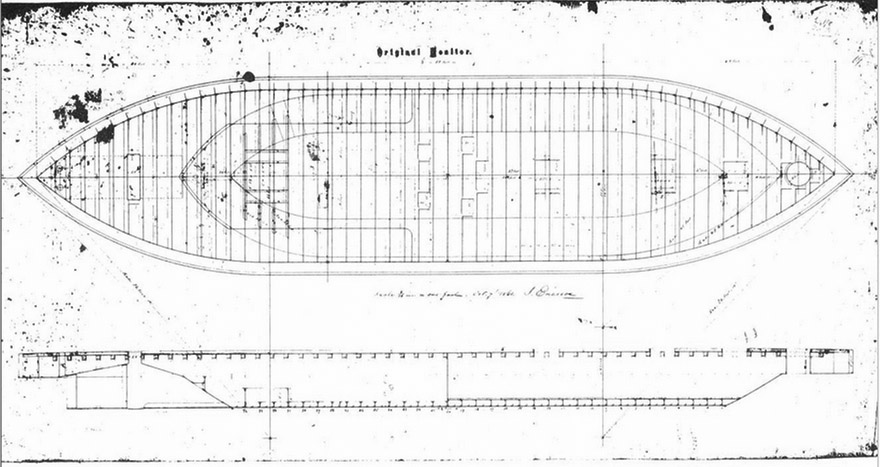

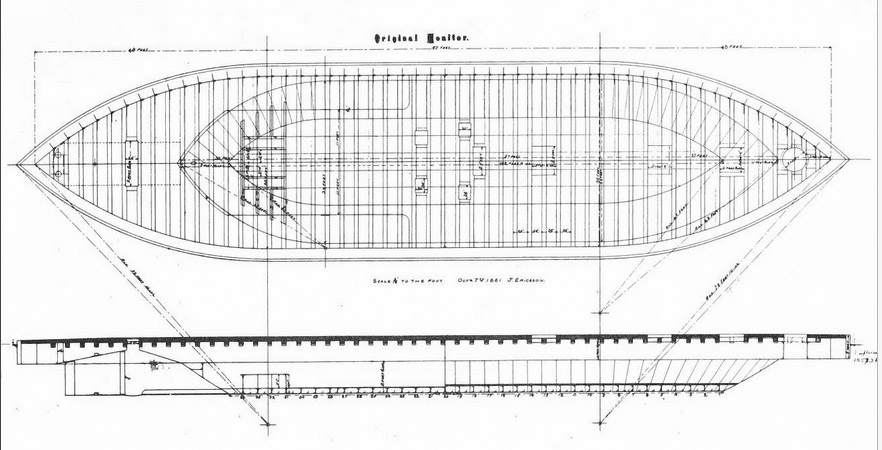

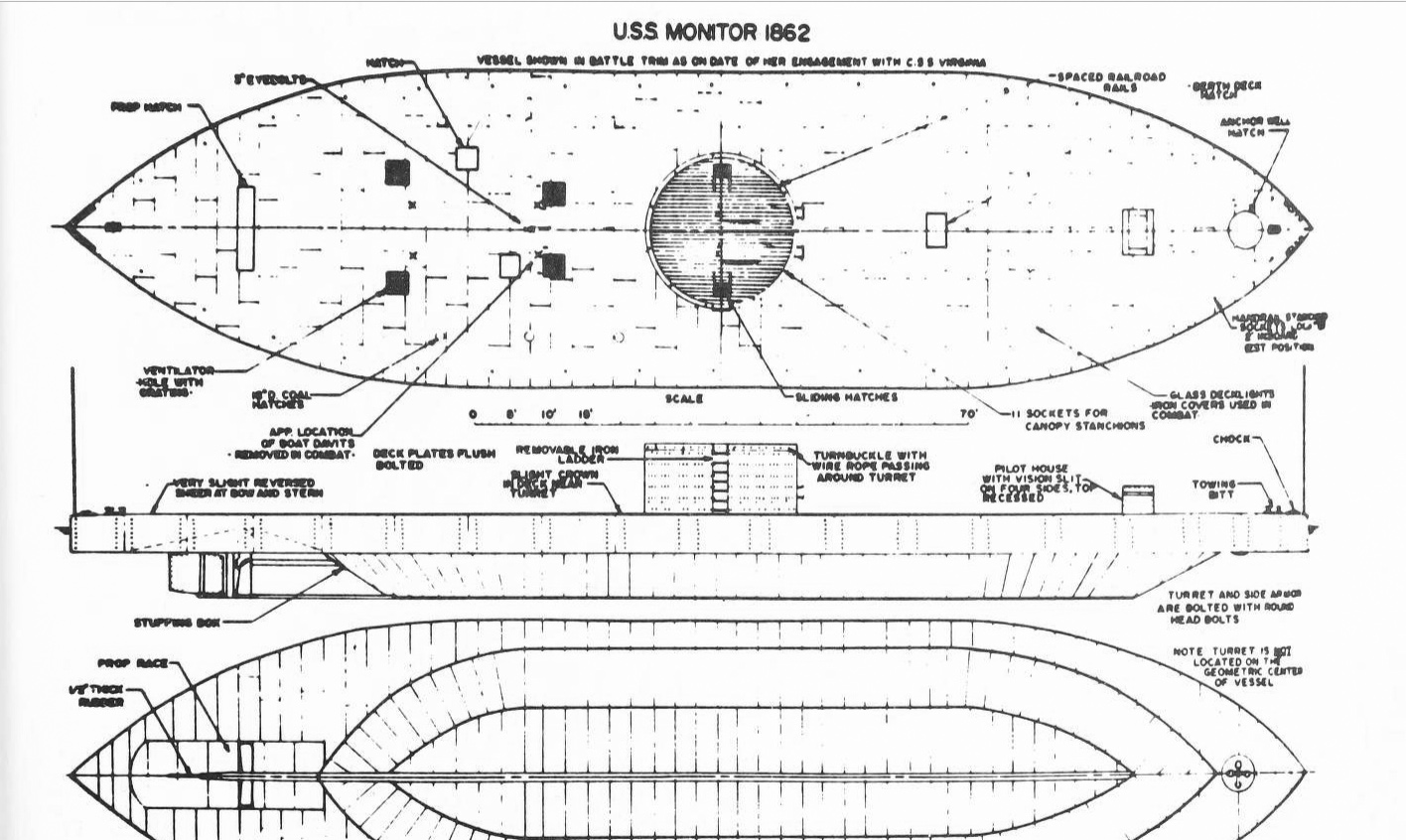

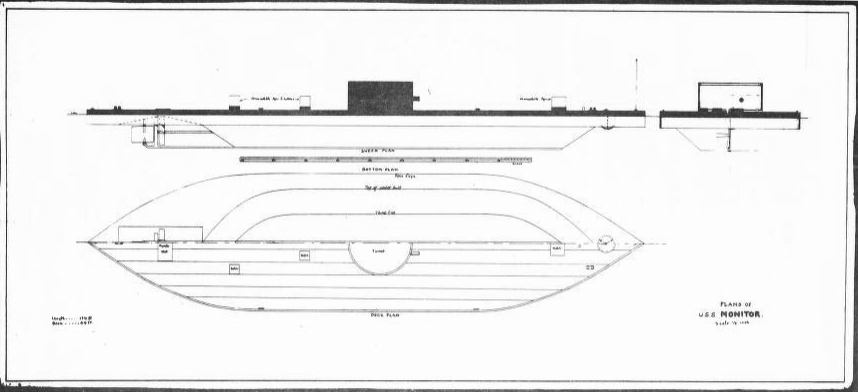

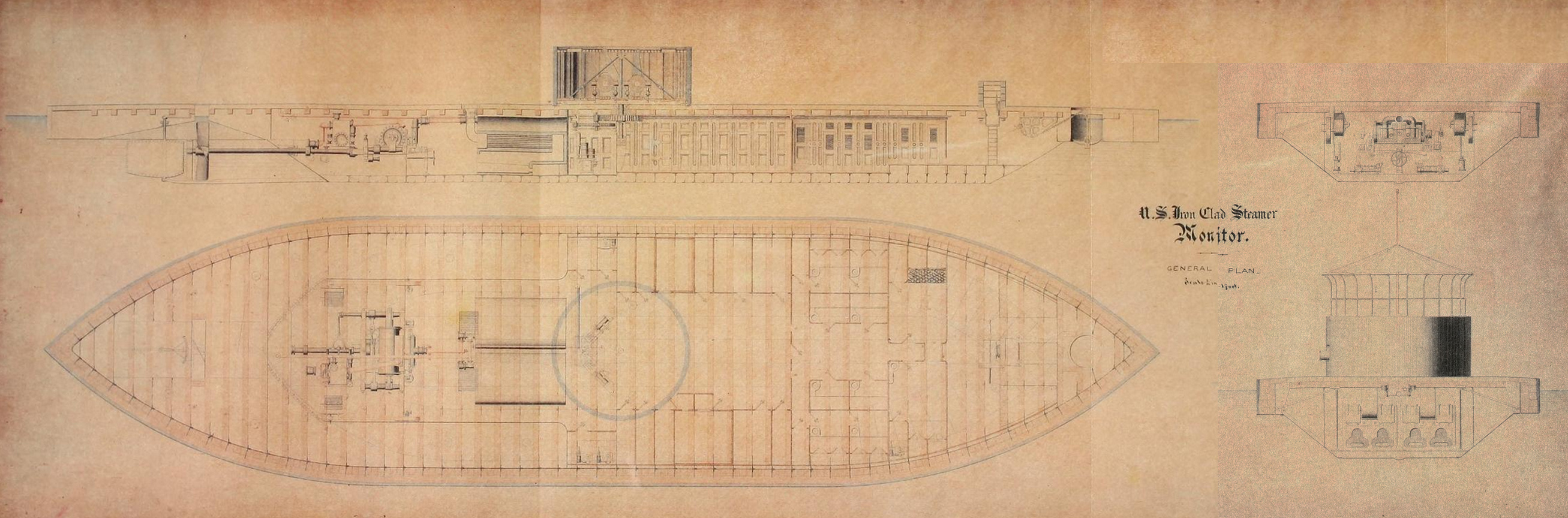

USS_Monitor_plans

The design was essentially ready since 1860, time to gather all technical informations about the turret’s Coles design and revolving bearing’s intricate designs, steam power, and armor construction around the wooden hull. The keel of USS Monitor was laid down soon after the board’s choice, on 25 October 1861, at Continental Iron Works, Greenpoint, Brooklyn, New York. She was launched on 30 January, and commission on 25 February 1862 (instead of the planned March 6, 1862 in accordance to the 100 days delivery as promised), an amazing achievement for the time, or for any ironclad.

This was largely due to Gideon Welles pushing hard across the board: Indeed near-completion of the CSS Virginia was known in the North by February 1862, through Mary Louvestre of Norfolk, freed slave using to be housekeeper of the Confederate engineers working on Merrimack revealed it to competent authorities, with intel from a Union sympathizer working in the Navy Yard. Louvestre met Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles in person, the latter raising the alarm and further pressed completion of the Monitor. From there, Lincoln’s hard-working Secretary of the Navy took charge personally of the completion.

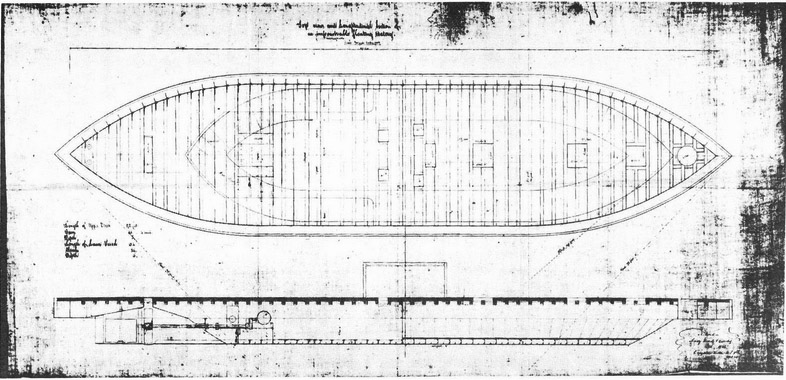

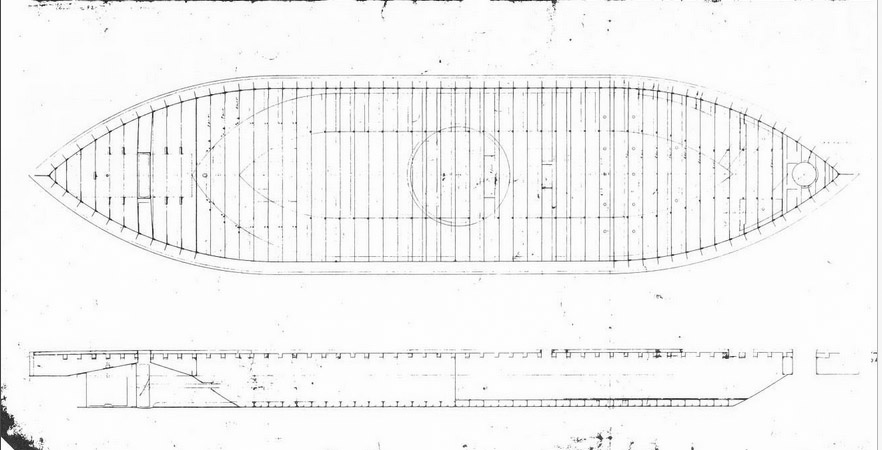

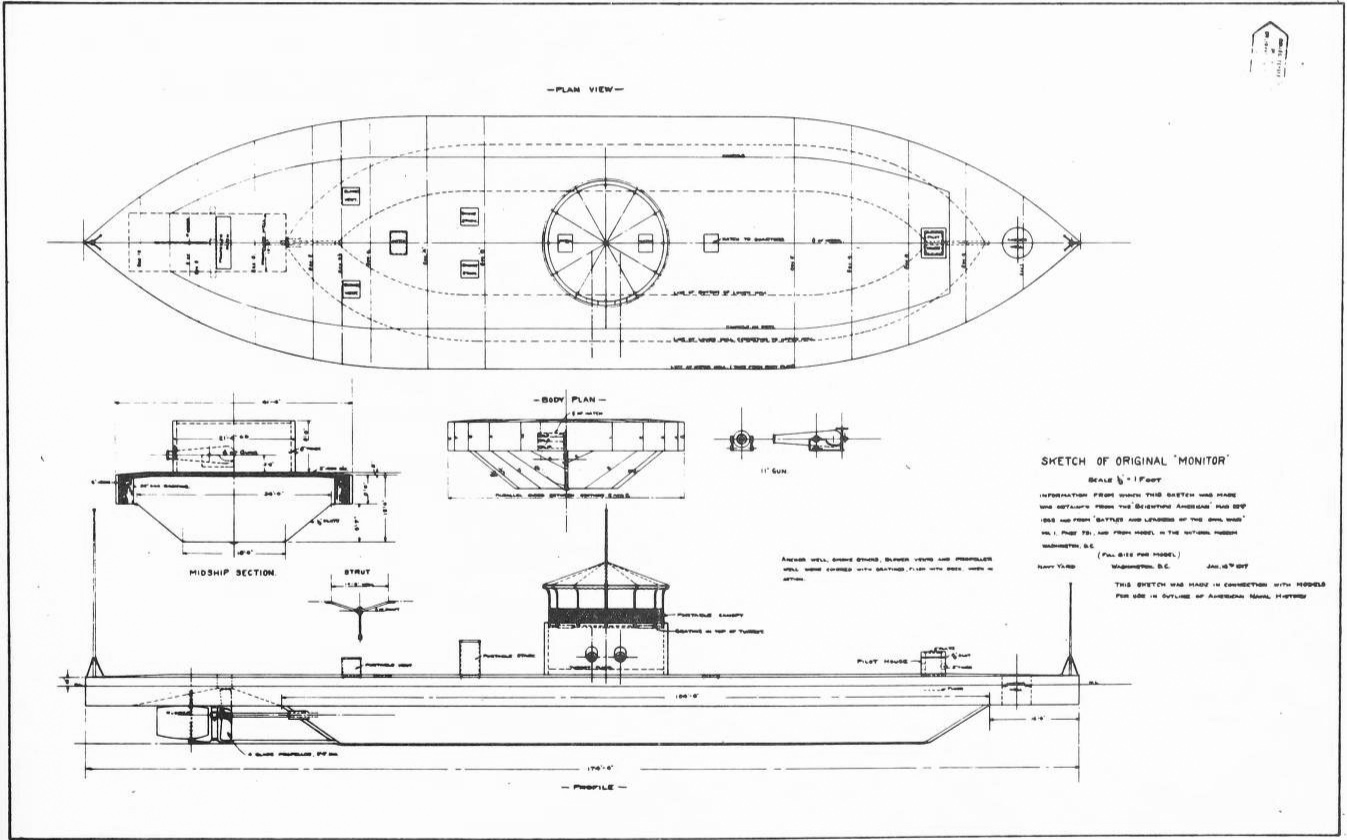

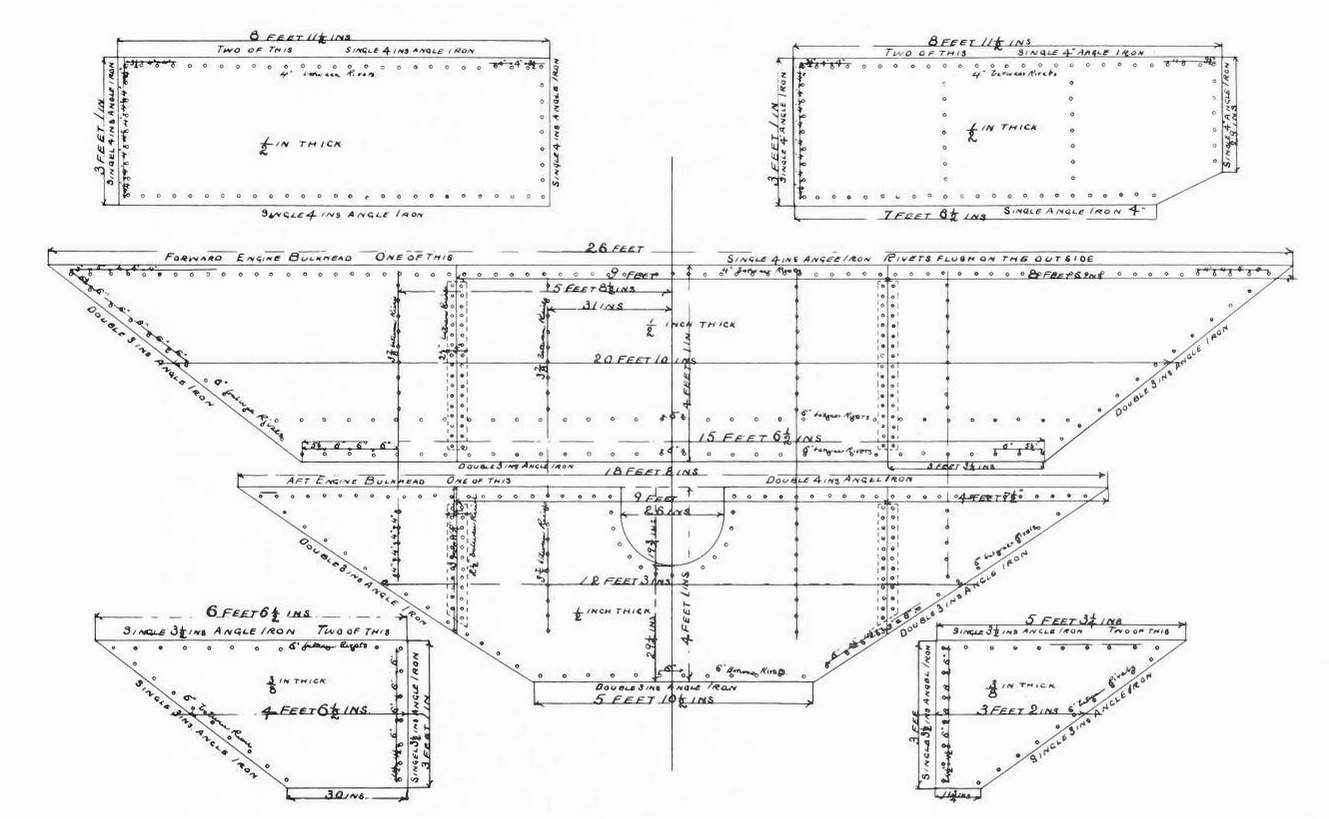

Hull of the Monitor

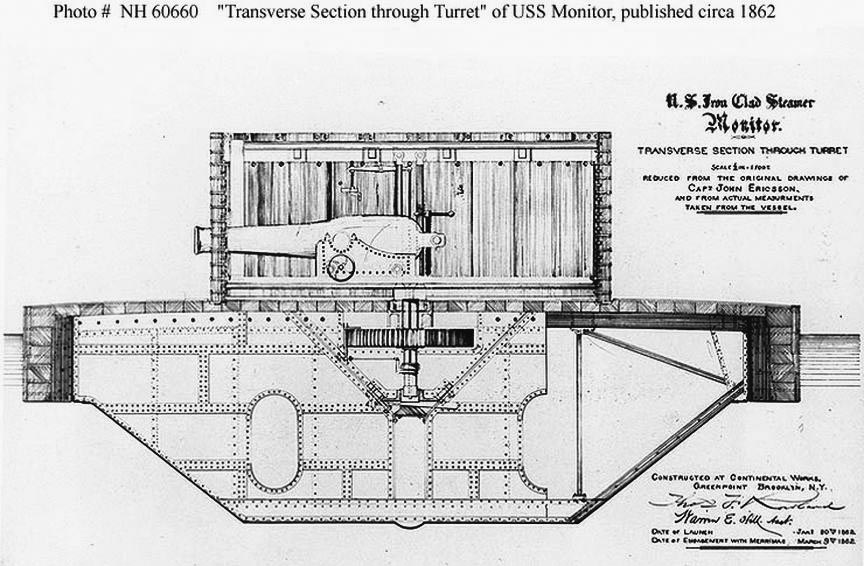

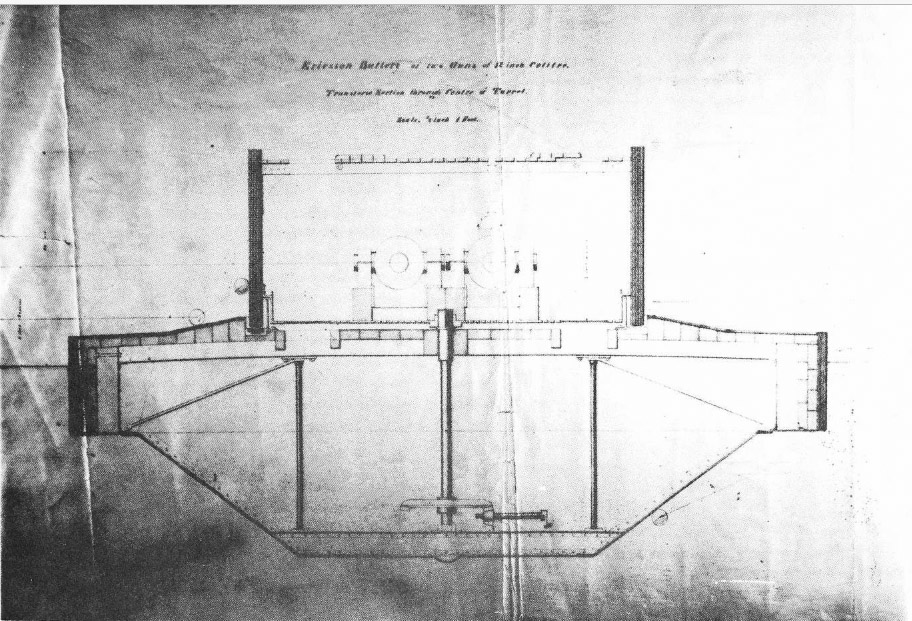

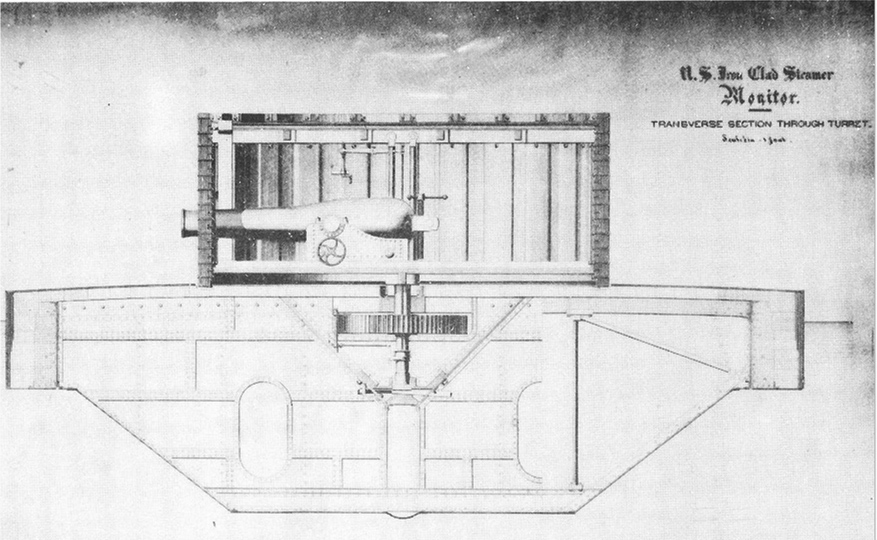

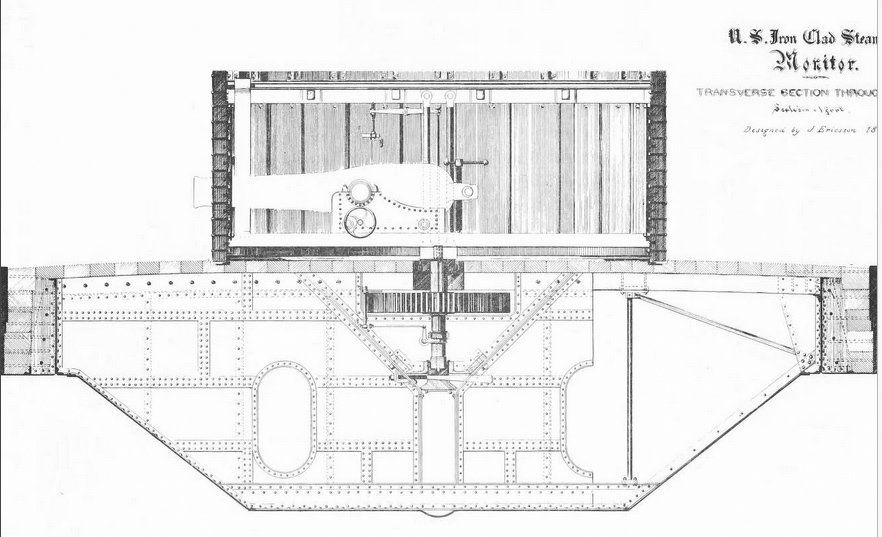

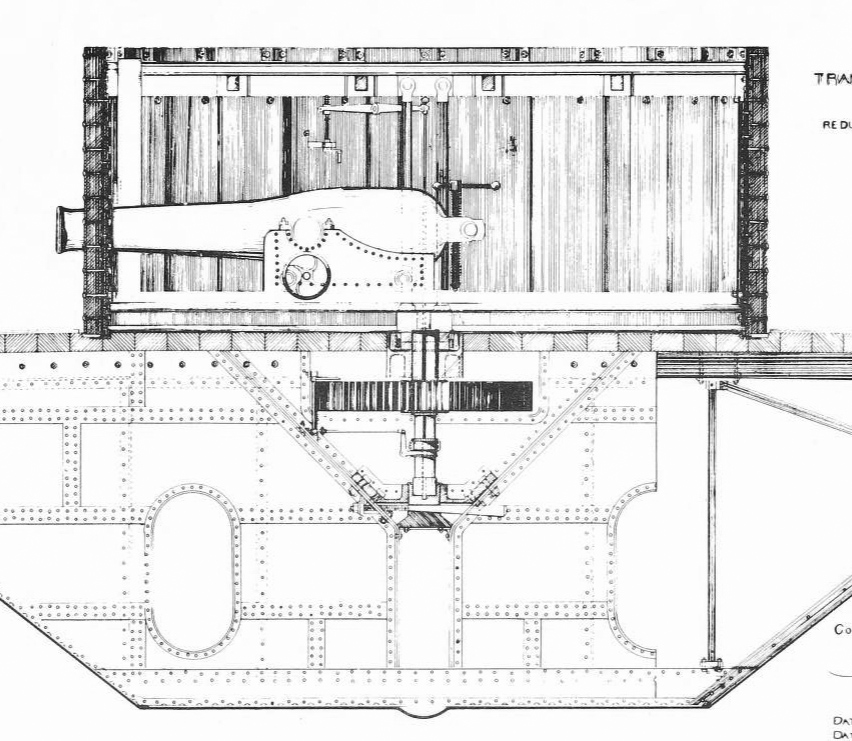

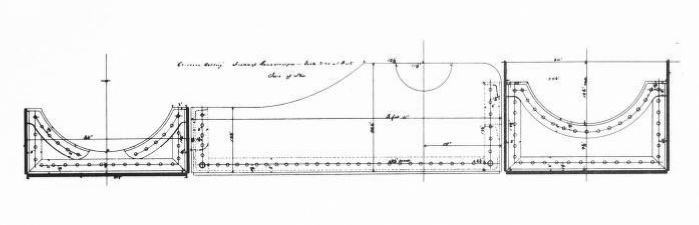

USS_Monitor_Transverse_hull_section_through_the_turret

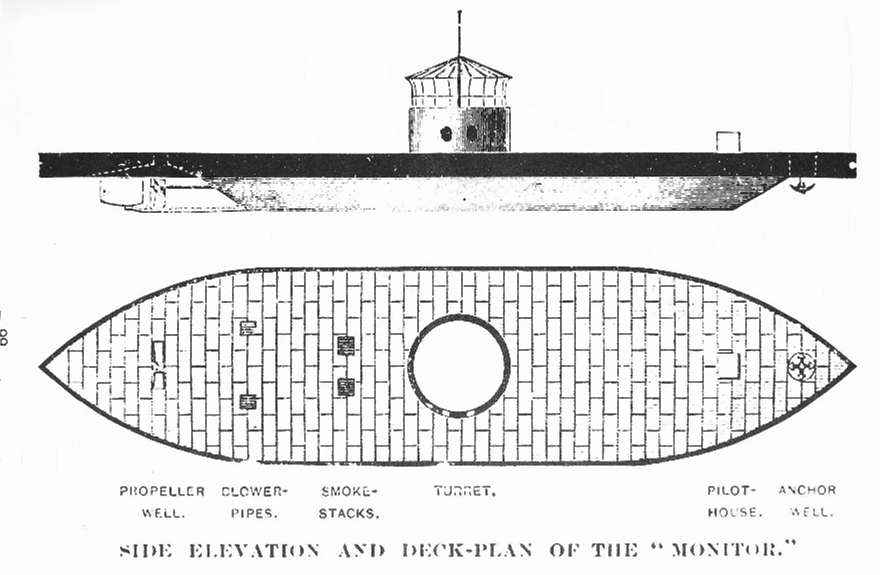

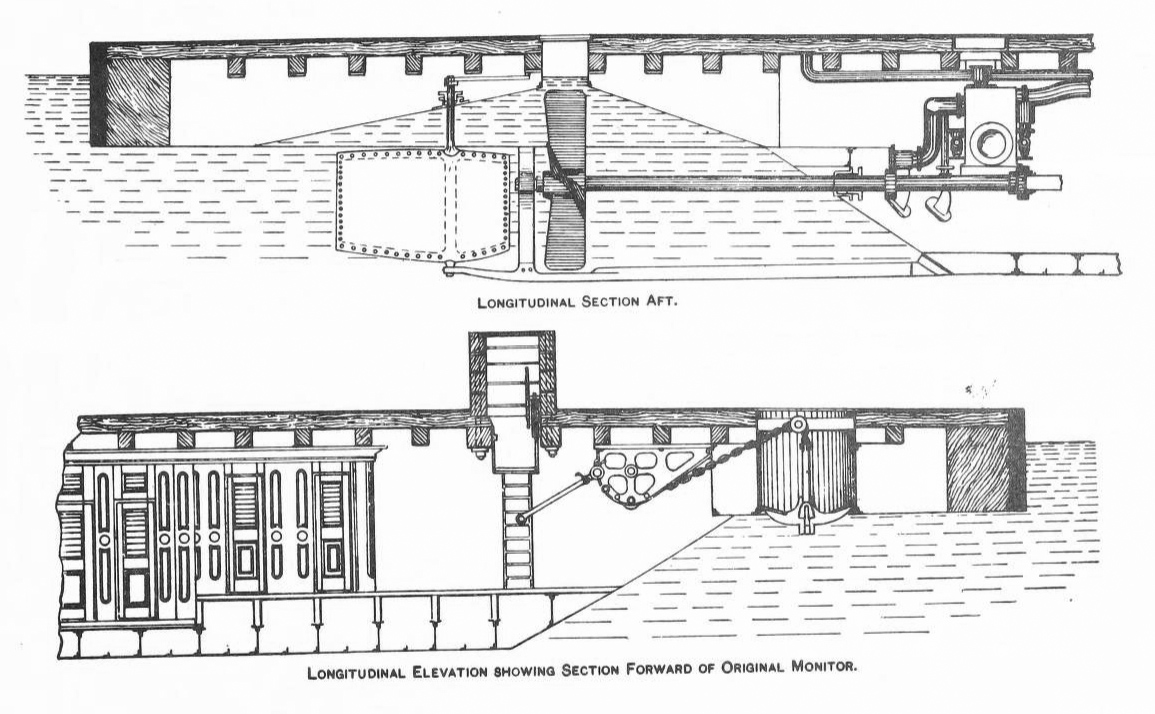

The basic idea was to present the smallest target possible, hoping shells landing too short would just bounce over the water, and those close enough, be slowed down enough to not penetrate. The basic hull shape was of a raft, with very little actual vertical surface to protect. Ericsson was not concerned by cannonballs landing on deck, as they would merely bouncing. Muzzle velocity was quite low at the time for the average Naval gun. Under the “raft” that was a rectangle with ogival ends as seen from above, symmetrical to steam both directions (although with aft rudder only), there was a smaller immerged hull with sloped sides and ends in order to manage sandbanks and shallow draft rivers like the Mississippi. This lower hull was much smaller, and contained in one space the machinery and coal supply for it. This difference between the much larger raft and lower hull gave her great stability, perfect for accurate firing in calm, to moderately rough seas. In short, the combination of a shallow-draught “raft” and smaller lower hull was typical of the Mississippi steamers of the time.

USS Monitor was for the time completely unheard of, bonkers and brillant. In almost every respect, dubbed by the press and critics as “Ericsson’s folly” or famously, “cheesebox on a raft”, “Yankee cheesebox”, its large cylindrical gun turret amidships was probably its most outstanding innovation. Apart this one, the raft deck was bare, apart a small armored pilot house towards the bow, surrounded with sloped sides. It housed a single pilot, but prevented the guns to be fired straight forward. Ericsson’s primary goal was to present the enemy the smallest possible target to gunfire. The hull was only 179 feet (54.6 m) long overall -gunboat size- 41 feet 6 inches (12.6 m) in beal, with gave her a favourable ratio, and maximum draft of just 10 feet 6 inches (3.2 m), allowing riverine operations. She displaced however 776 tons burthen due to the armor, 987 long tons (1,003 t) fully loaded. Despite having just two guns she still carried 49 officers and ratings.

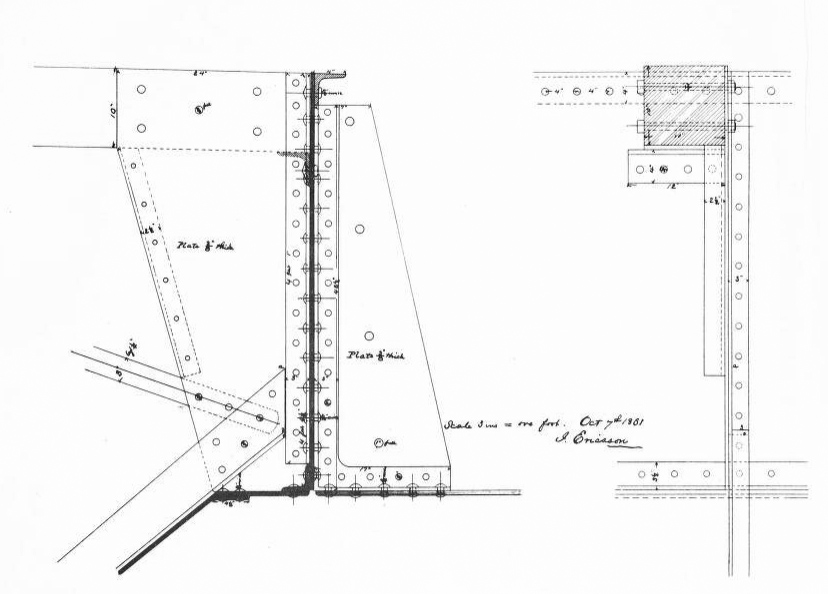

Protection

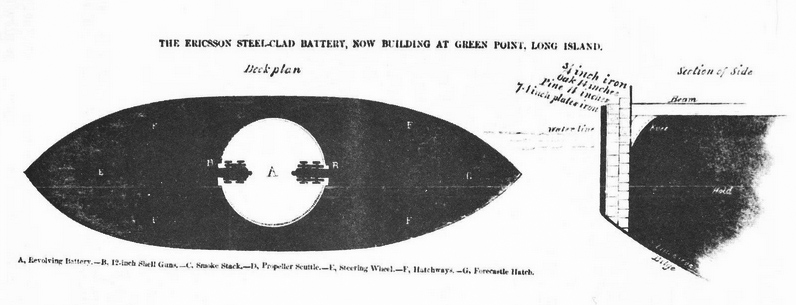

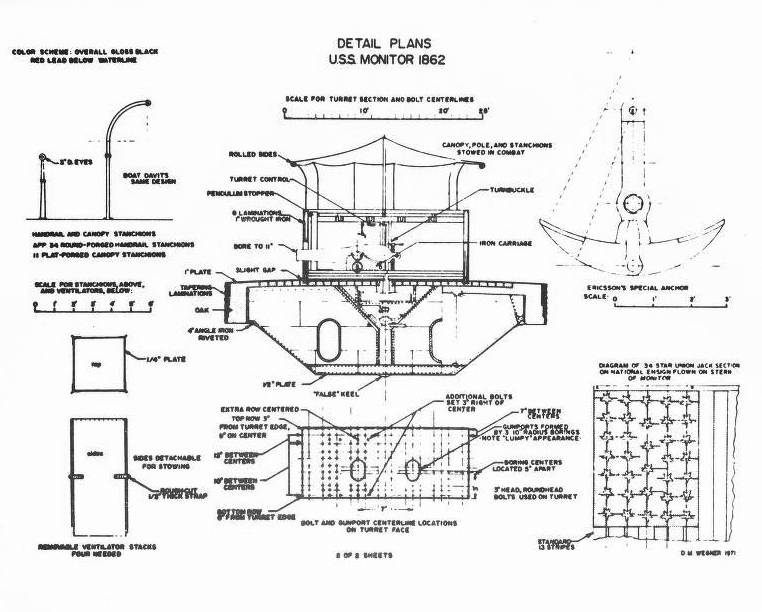

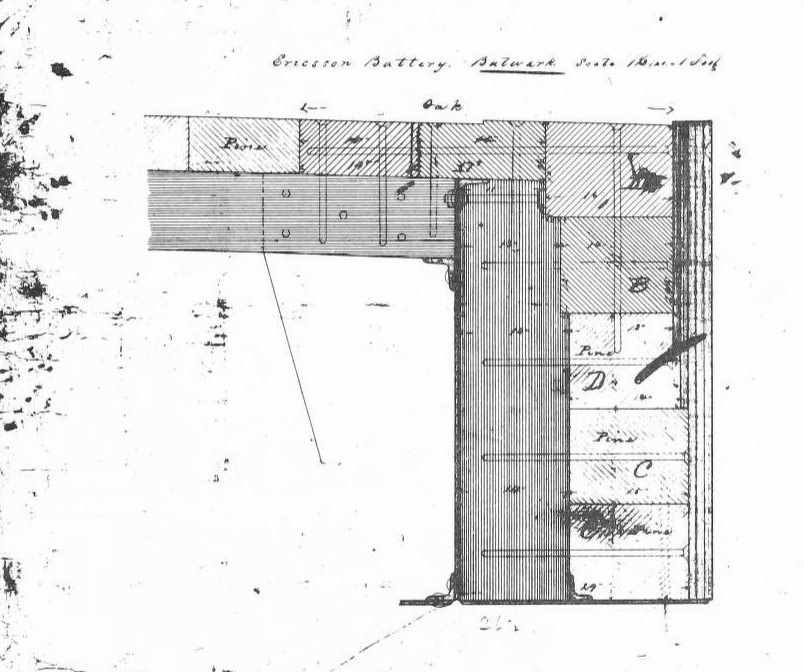

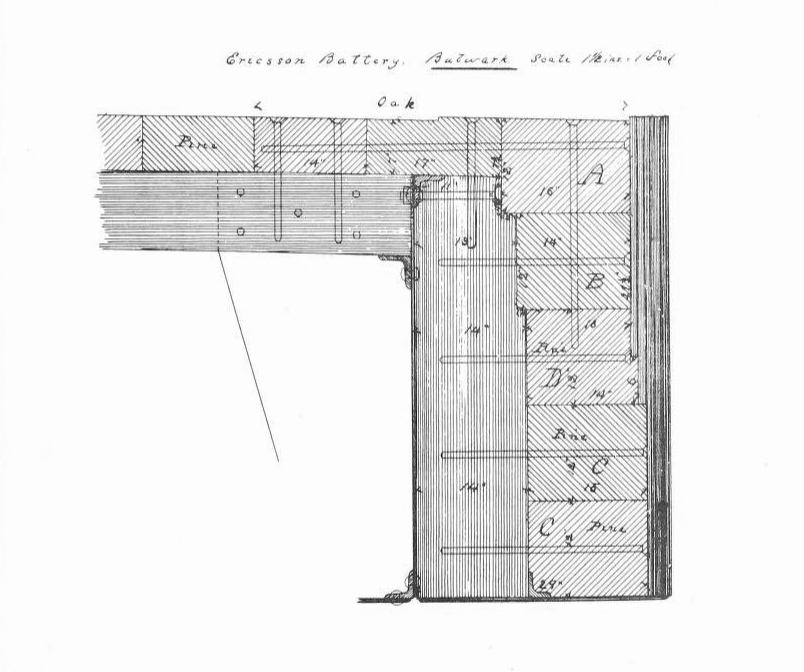

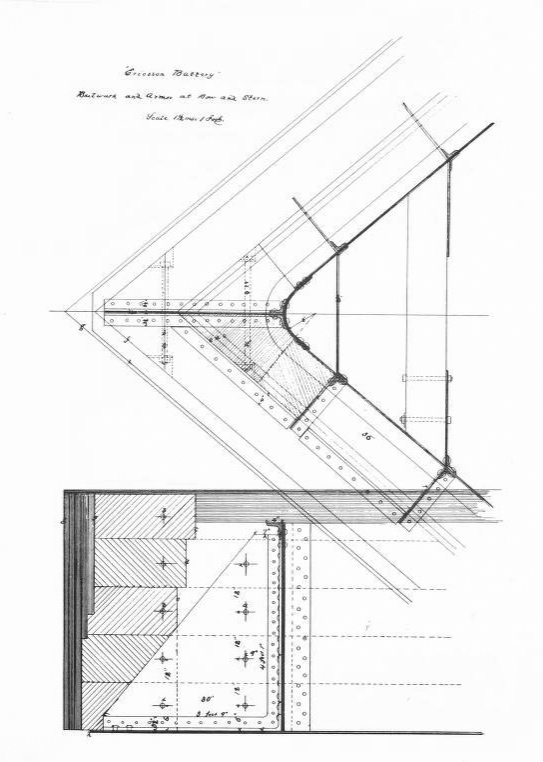

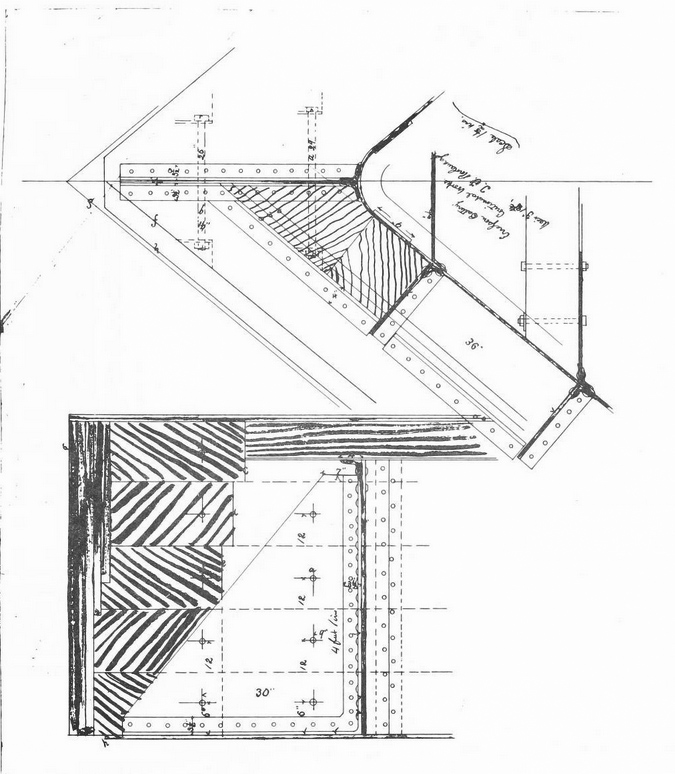

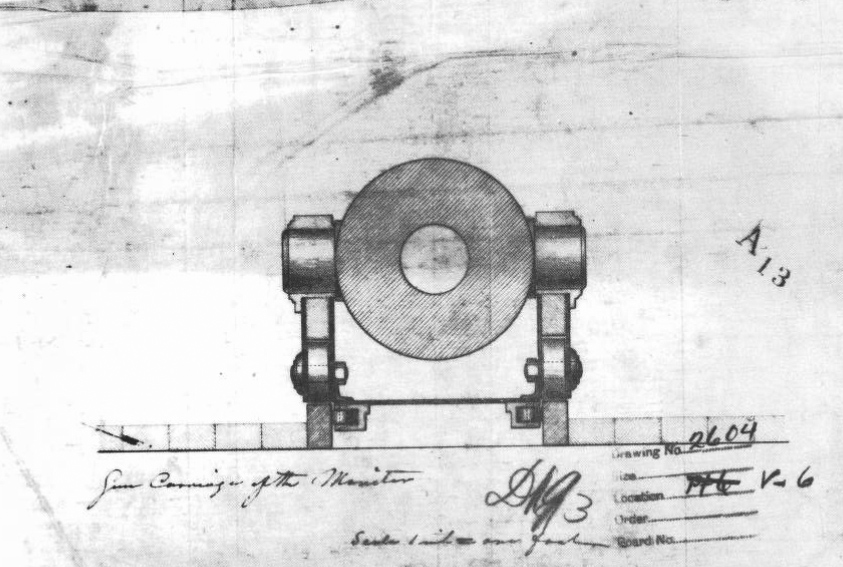

Section of the belt armor showing the iron plating sandwich and wooden backing. In this interesting early draft, the original gun position is also shown. Due to the recoil and turret’s size it was impractical.

With an armored deck just 18 inches (46 cm) above the waterline, a cannonball had a very small target to hit. The deck was created out of two layers of 1⁄2-inch (13 mm) each, in wrought iron armor, the best tech at the time for iron casting, to boiler grade. If seemingly weak, it was largely enough for bouncing projectile, parabolic fire did not existed at the time for ships, and USS Monitor was not intended to duel with siege mortars… The armoured belt ran all along the “raft” made of 3-5 layers of 1-inch (25 mm) each iron plates. They were backed by 30 inches (762 mm) of pine and oak.

A 3-plates layer extended for 60-inch (1,524 mm) in height and the two innermost plates stopped mid-way down. Ericsson original plan was to use five combined 1-inch plates, or a single outer 4-inch (100 mm) plate backed by three 3/4-inch (19 mm) plates. However the metal industry at the time was unable to roll that type of very thick plate quicky enough. The two innermost plates were riveted, the outer plates bolted to the former. There was a ninth plate 3/4 inch (19 mm) thick but 15 inches (381 mm) wide bolted over the butt joints of the innermost plate. The very exposed, small pilot house forward was protected by 9 inches of armour (229 mm) with well sloped sides all around. Apart glass portholes in the deck for natural light, covered by iron plates there was no other way to have the lower hull provided with lighting.

Interior replica showing the Dalghren guns and turret cutaway

After the battle of Hampton Roads some Navy officials criticise the raft design as too easy to boarding by Confederates. On 27 April 1862 Lt.Cdr O.C. Badger advised the Assistant Inspector of Ordnance of a water sprayer from the boiler, through hoses and pipes to repel boarders. Hot water pipes arranged to scald assailants were envisioned but never installed apparently, before the disapperance of USS Monitor.

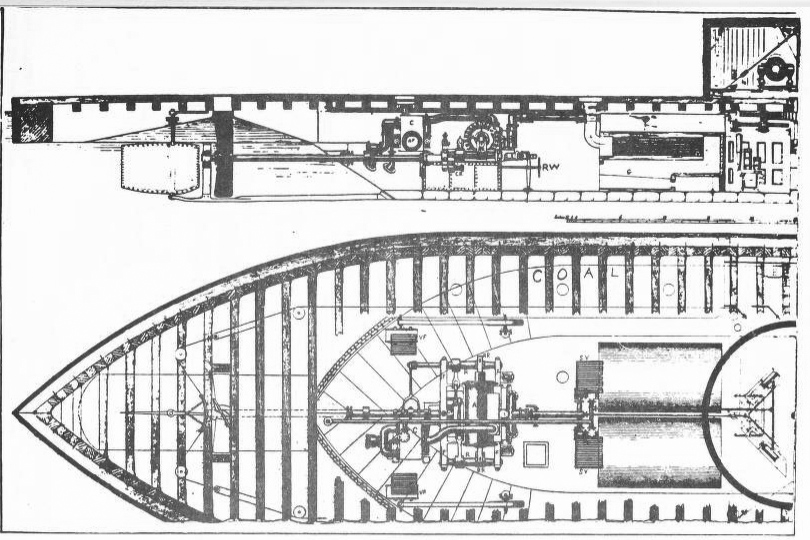

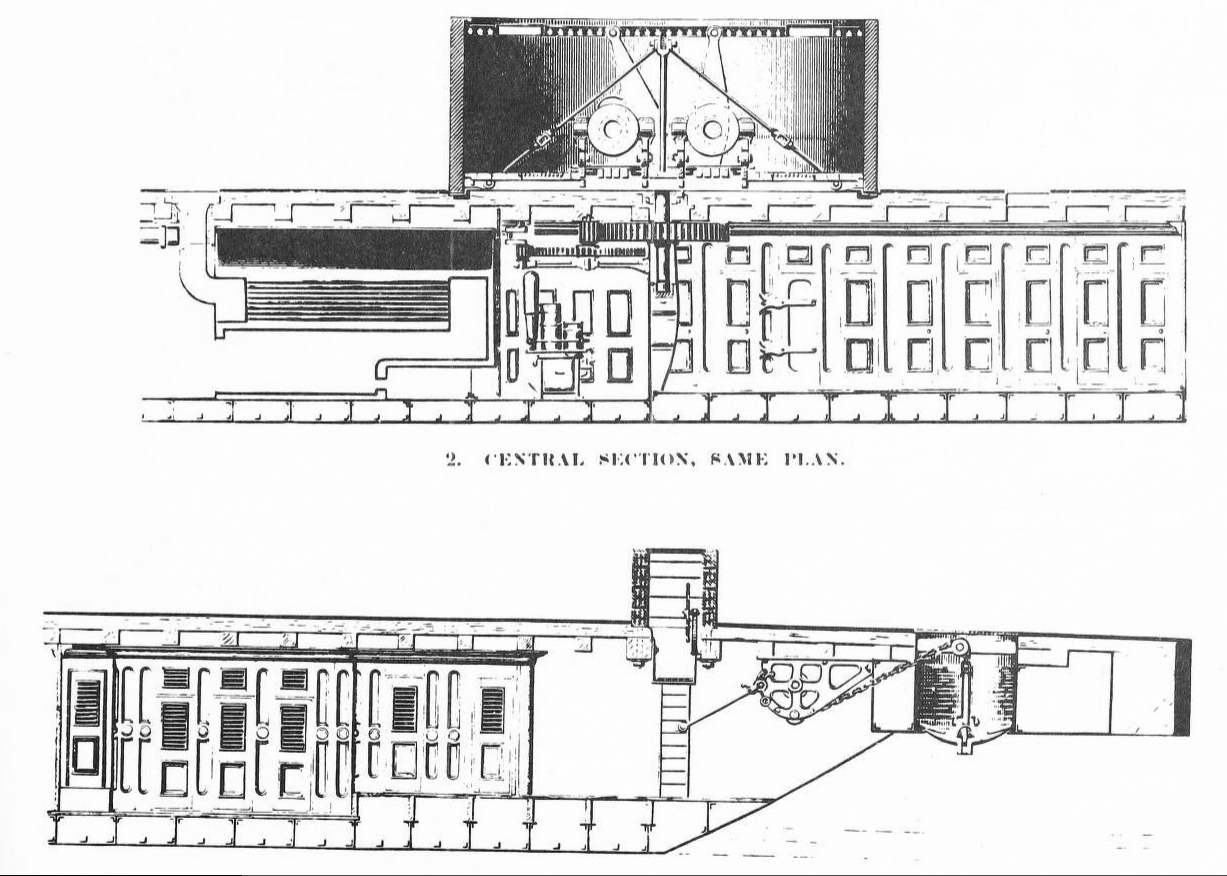

Various design features: Sections, Powerplant, accomodations, deck plans, auxiliary machinery and sounding system.

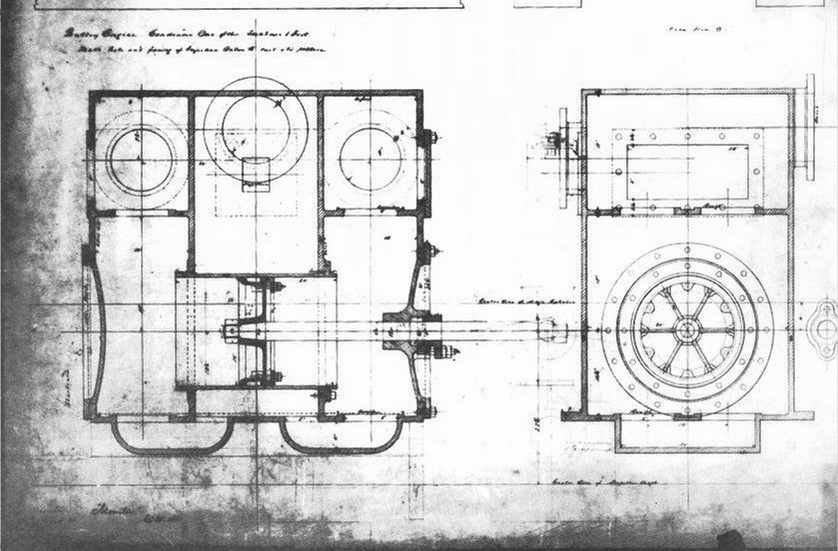

Propulsion

Aft section cutaway, showing the powerplant, rudder, shaft, gears and propeller as well as the front section and anchor lifting system.

Rudder

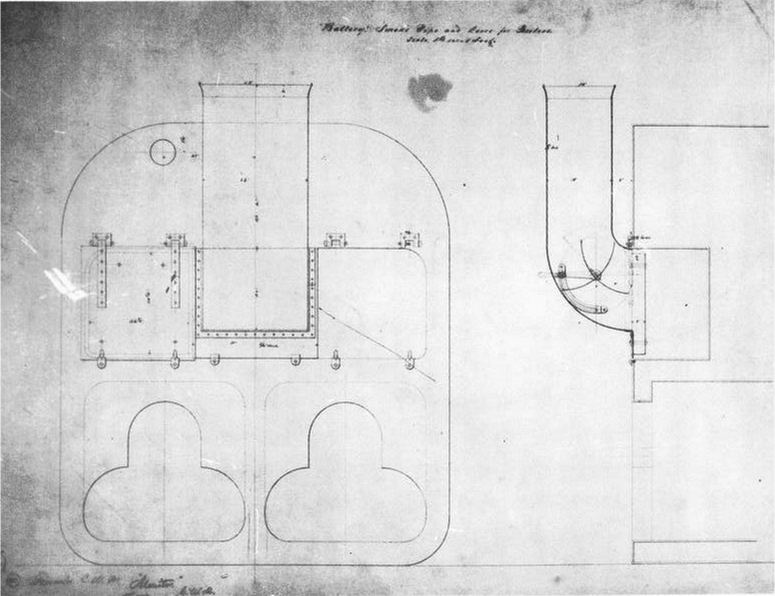

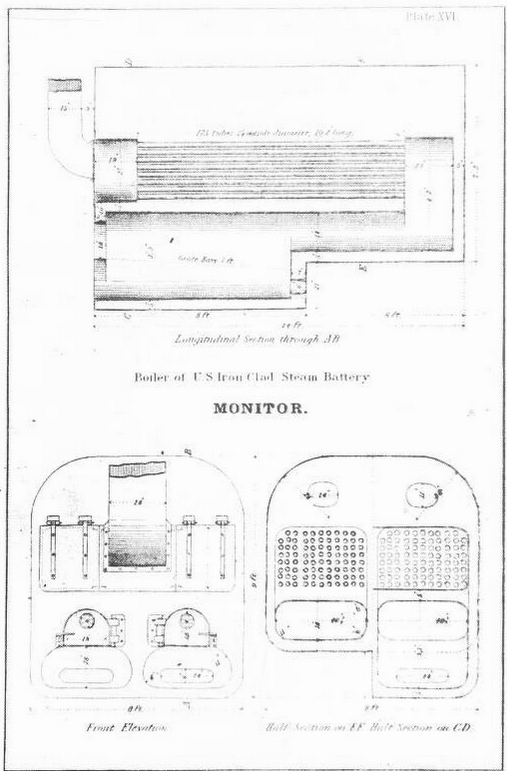

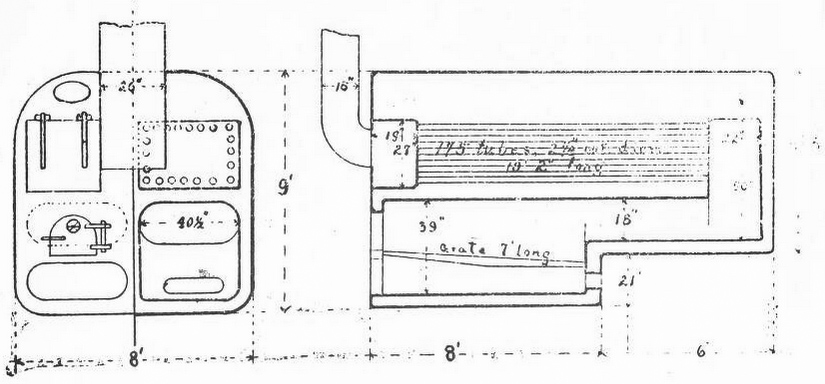

Boilers

Furnaces design

Boilers more detailed

Steam engine overview (section)

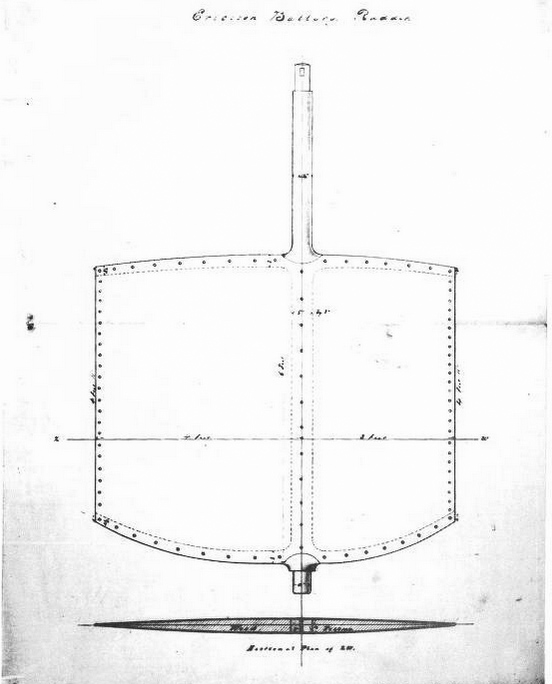

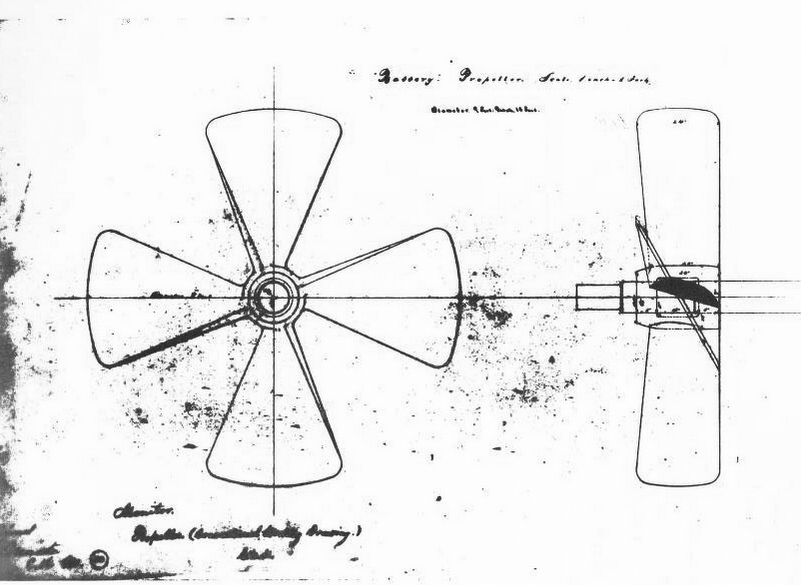

Propeller

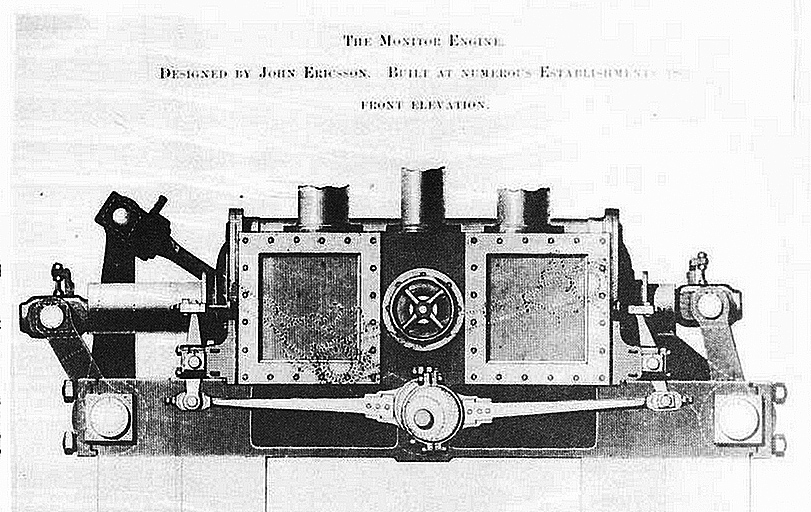

Inside the lower hull, there was a single-cylinder horizontal vibrating-lever steam engine designed by Ericsson (which had quite a long experience as we saw). It had a bore of 36 inches (914 mm), stroke of 22 inches (559 mm). It drove a single 9-foot (2.7 m) propeller, mated on a nine inches diameter shaft. Steam was generated by two horizontal fire-tube boilers at a working presure of 40 psi (276 kPa, 3 kgf/cm2). This enabled the anemic (but standard at the time) 320-indicated-horsepower (240 kW), for a top speed of 8 knots (15 km/h; 9.2 mph), at least as planned. This was still good for a steamship at the time, but range was diminished by the absence of sail. Ericsson brished this consideration as she was more of a coastal “interceptor”, to catch the Virginia off Hampton roads.

On sea trials, USS Monitors reached 1–2 knots (1.9–3.7 km/h; 1.2–2.3 mph) lower than expected, or 6 knots (11 km/h; 6.9 mph). For range, 100 long tons (100 t) of coal were carried, enough for an estimated 500 nm. Ventilation was procured via two centrifugal blowers near the stern powered each by a 6 hp steam engine. One fan circulated air throughout the ship for the crew, the other was decicated to feed the boilers, a forced draught. Leather belts also connected the blowers to their engines, stretching when wet which disabled both the fans and boilers, as shown later. The pumps were also steam-operated and so if the latter was too low, they would fail. This was in essence what happened when the Monitor sank. It seems there was no manual backup, as Ericsson was overly confident on his steam engine.

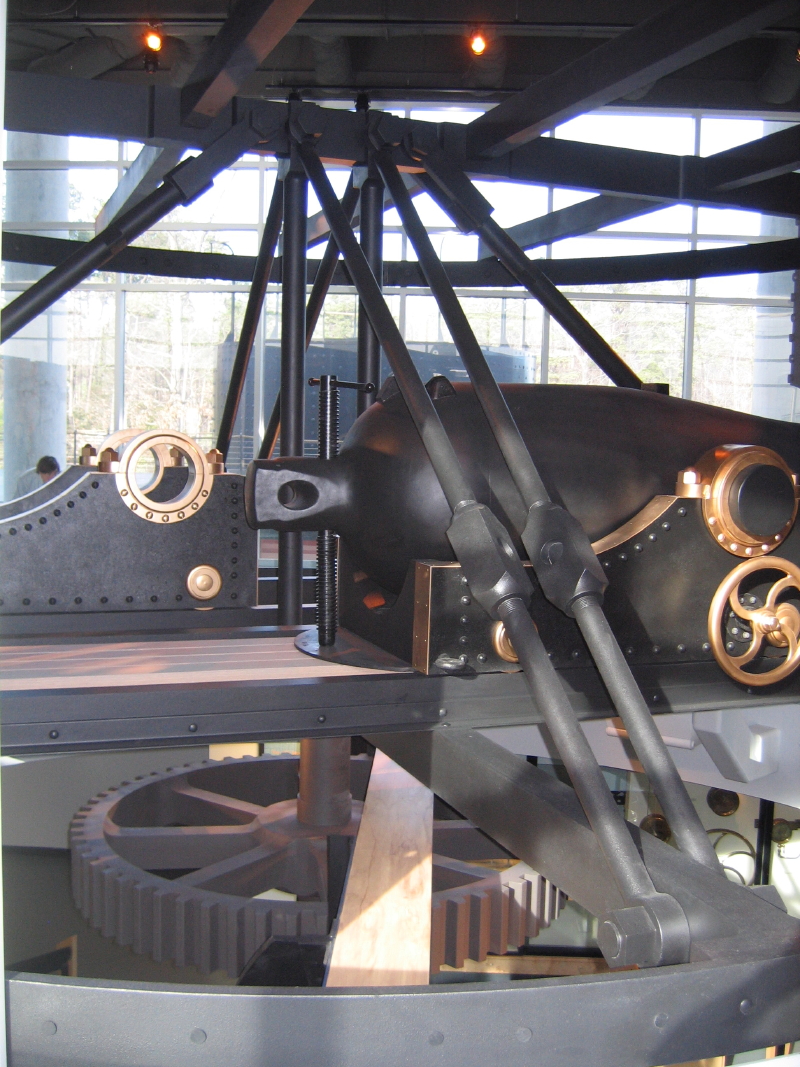

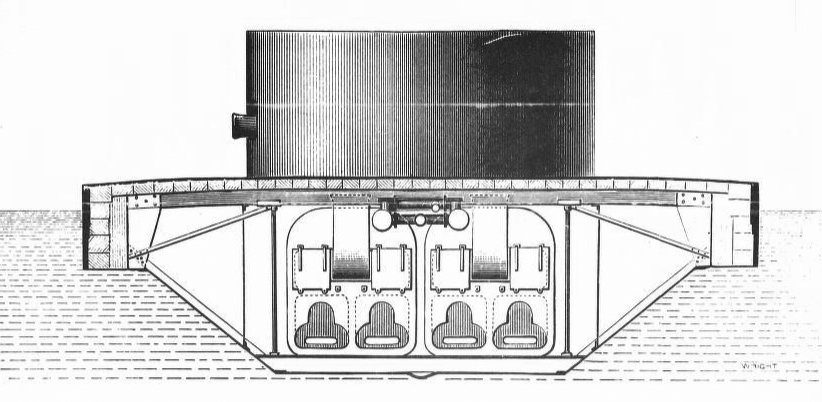

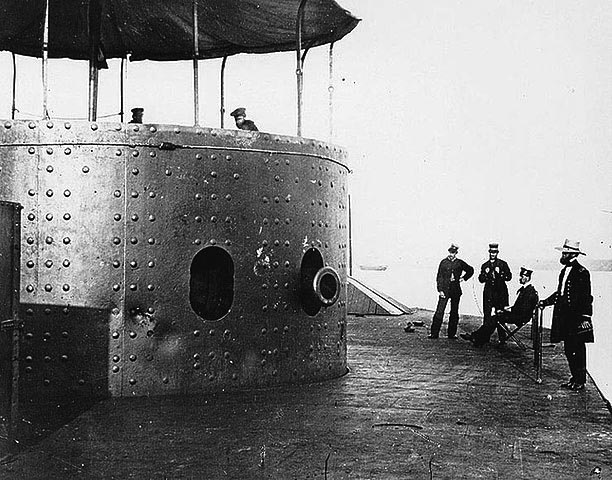

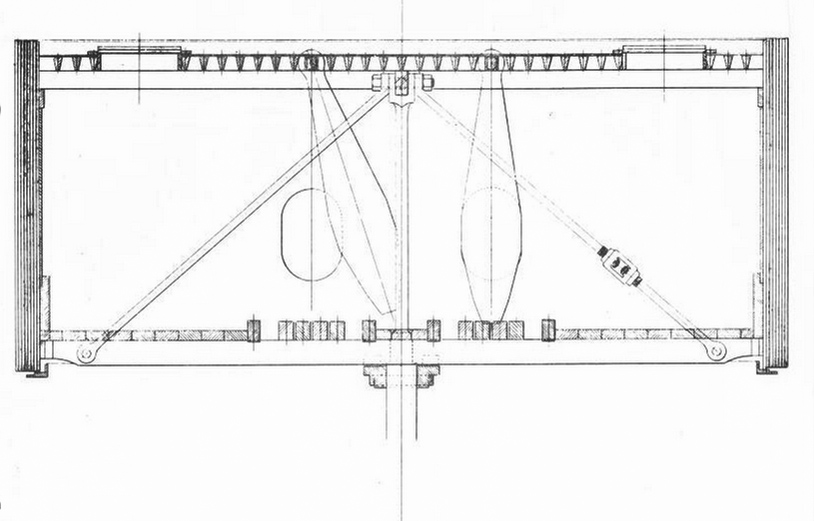

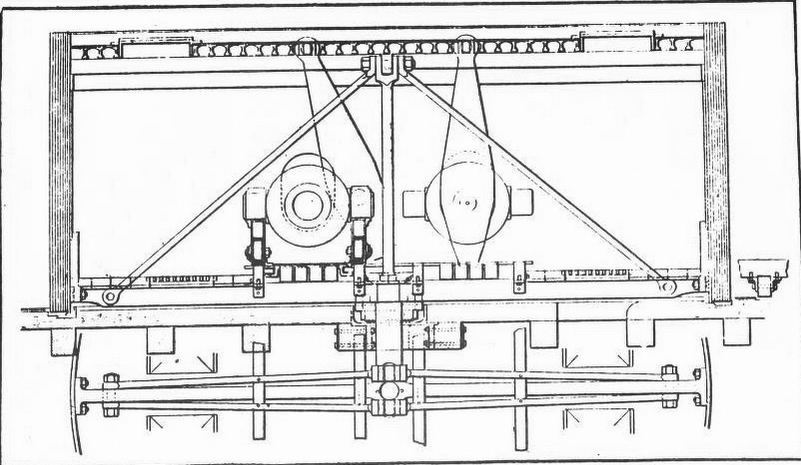

Turret

USS_Monitor_James_River_1862

Monitor’s turret was 20 feet (6.1 m) in diameter, 9 ft (2.7 m) high. She barely accomodated the two Dahlgren cannons, which practically hit the other side after recoil. The walls were constructed of 8 inches (20 cm) of armor but reached 11 inches (290 mm) at the front, around the gun ports. The ensemble weighed approximately 160 long tons, and this made her top heavy, but the rounded shape helped deflecting cannon shot, and were proved impregnable. There was no spall lining however. She rolled on her bearing thanks to the use of two steam-powered donkey engines, using a set of gears. Full rotation was performed in 22.5 seconds, as noted in tests reports of 9 February 1862.

Her motion was difficult to control also, as the steam engines were to be reversed if the turret overshot and had to turn the other way, which took time. So much, that in that case, the gunnery officer ordered another full rotation instead. The gun ports provided the only sight of the target, and were obscured by the guns and smoke. They were shut were not in use with heavy iron port stoppers, swing down. The rotation mechanisme used an iron spindle, jacked up using a wedge, before the turret could rotate, which was 9 inches (23 cm) in diameter. This prevented the turret from sliding sideways, and in normal travel condition, it was disconnected and the turret rested on her deck brass ring, forming a watertight seal (but leaked heavily as it appeared due to heat differences).

The gap between the turret and deck was not immune to debris and shell fragments either. A large enough shard could enter it, jamming the mechanism. That’s what happened for several Passaic-class monitors with the same turret design at the Battle of Charleston Harbor (April 1863). Also, Direct hits on the turret could eventually bend the spindle, causing another jamming. It was accessed from below or via the hoist to lift powder and shot. Another issue on that matter is that the turret needed to rotate to face starboard to line up the entry hatch ans proceed to the reload. The turret’s roof was light, easy to remove to change the guns, and provide a welcome aeration and ventilation. It was not bolted, only held by gravity.

Monitor’s turret section

Monitor’s turret section

Monitor’s turret shutters

Turret base and axial needle

Armament

Dahlgren guns

The initial armament as planned was a pair of 15-inch (380 mm) smoothbore Dahlgren gun, casted for her. However the ship was ready sooner, and due to the need to have her operational, she received two 11-inch (280 mm) instead of the same type, weighing still 16,000 pounds each. They used a 15 Ibs (6.8 kgs) propellant charge marked for targets “distant”, “near”, and “ordinary”. These fired a 136-pound (61.7 kg) round shot/shell to a max range of 3,650 yards (3,340 m) at the maximal elevation of +15°. However in practice during her duel, she fired at point-blank.

Dahlgren guns base section

Dahlgren guns cradle design

Old author’s illustration for USS Monitor

⚙ USS Monitor’s specifications |

|

| Dimensions | 54.6 x 12.6 x 3.2 m (179 x 41 x 10 feets) |

| Displacement | 987 tons standard, 776 tons Fully Loaded |

| Crew | 49 |

| Propulsion | 1 shaft VLSE, 2 HFT boilers, 320 ihp (240 Kw). |

| Speed | 6 knots (11 km/h) |

| Range | Unknown |

| Armament | 2× 11-in (280 mm) Dahlgren SB |

| Protection | Belt 3-5 in, decks 1 in, turret 8 in, pilot house 9 in |

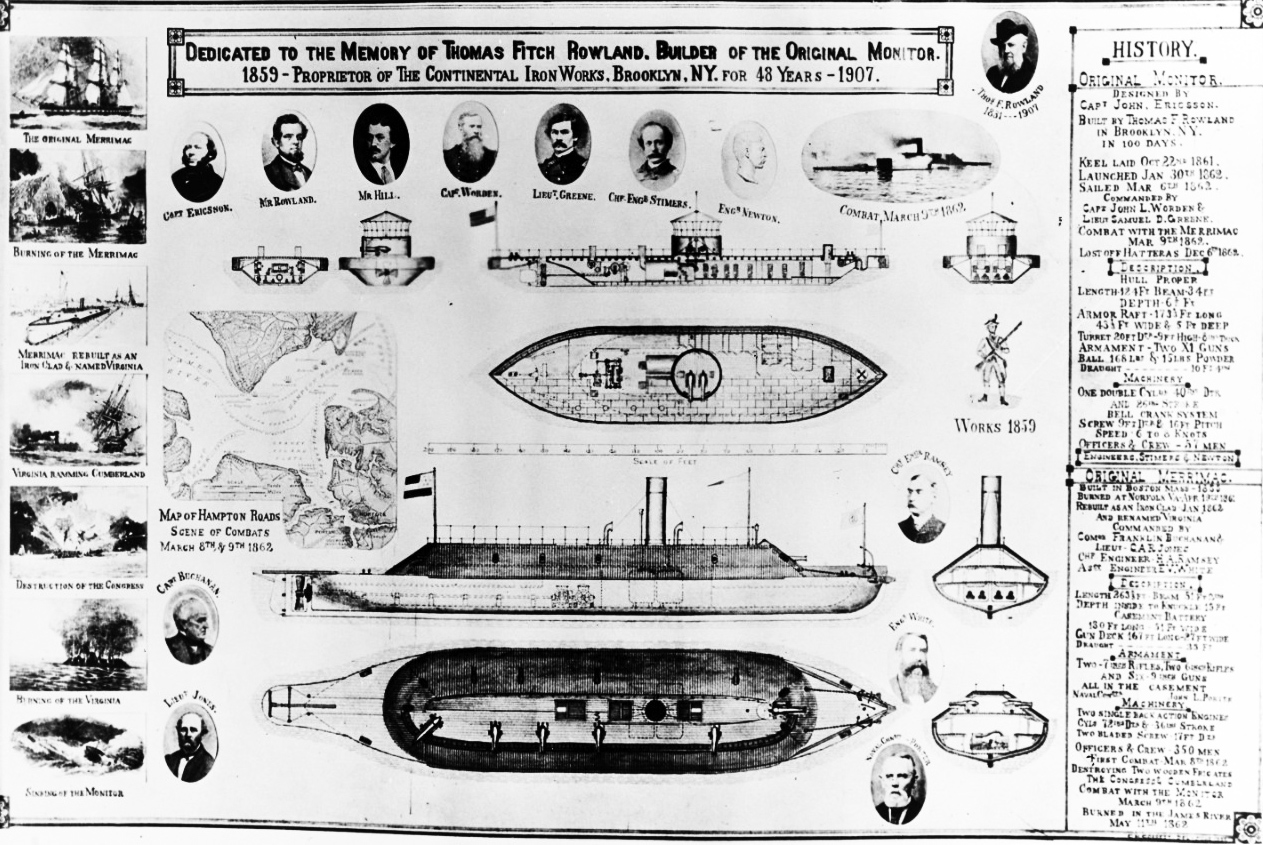

Construction of USS Monitor

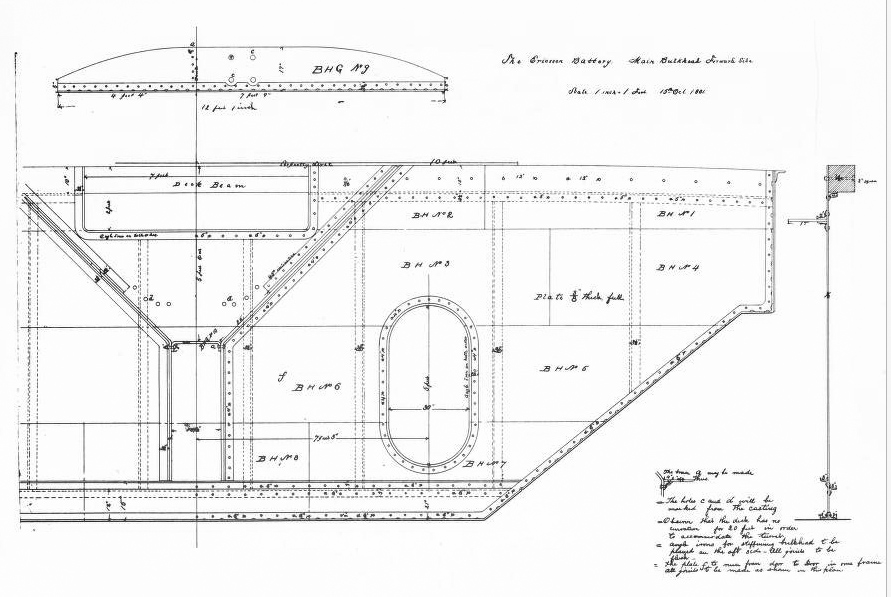

HD original drawing of the Monitor

The Chief of the Bureau of Yards and Docks, Commodore Joseph Smith, sent Ericsson his formal notice of proposal acceptance on 21 September 1861. On the 26th, Ericsson signed a contract with Bushnell, John F. Winslow and John A. Griswold which in which they would equally share profits or losses incurred to the construction of the ironclad. They were ready to start afterwards, but a major delay was caused by the government itself, which did not signed any actual contract yet; Some were still not convinced and Welles had to add a clause of “complete success” of the ship, otherwide a refund would be provided. This draconian provision was hard pill to swallow to his partners, and the Navy rejected this modification of contract, finally signed on 4 October, so 15 days after, and a final agreed price of $275,000, paid in installments along construction phases.

Preliminary work was ready since a while, Ericsson’s consortium already in discussions with Thomas F. Rowland (Continental Iron Works, Bushwick Inlet, now Greenpoint, Brooklyn), and they signed a final contract on 25 October for the hull, which keel was laid that day. The turret was built at the Novelty Iron Works, Manhattan. After being assembled and tested, it was disassembled and shipped to Bushwick to be mated on the hull. The steam engines and machinery were built at DeLamater Iron Works nearby, in Manhattan. Chief Engineer Alban C. Stimers was appointed Superintendent while construction. His advices were precious as he was a former officer onboard USS Merrimack now in confederate hands. New formally assigned to the crew, he still became inspector during USS Monitor’s maiden voyage and the battle of Hampton Roads as well.

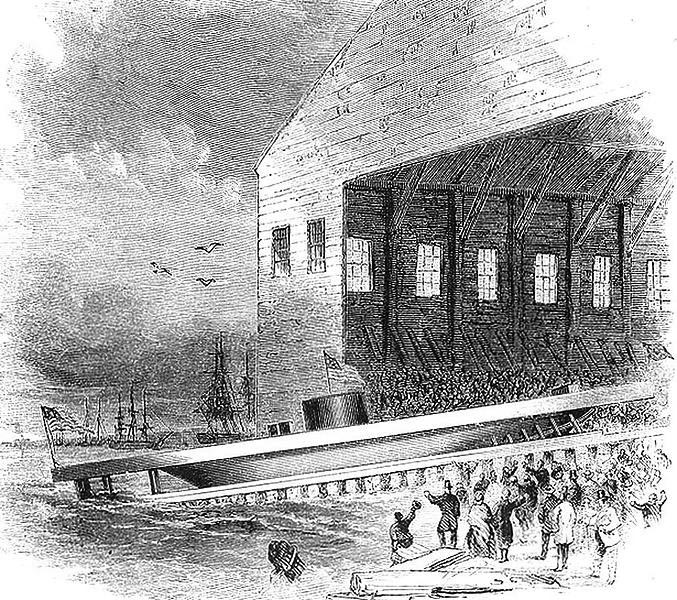

Construction was plagued by short delays, starting with the delivery of iron and money at times, but the progress was still good and the hundred days allotted expired on 12 January, as the ship was not yet completed. The Navy, which new what was at hand, did not to penalized the consortium. The name “Monitor” was proposed by Ericsson on 20 January 1862, approved by Assistant Secretary of the Navy Gustavus Fox. The new ship was to “correct the wrongdoers” (the Confederacy). When the ship was launched, Ericsson in defiance of those arguaung she would never float, was standing on her deck on 30 January 1862. There was a ceremony, and this was done under the cheers of the massive crowd of Newyorkers, which interest was flamed by the press all along. She was commissioned rather quickly, on 25 February, as her fittings were quick, but she already made initial sea trials on 19 February.

Launch, 30 January 1862

Valve and fan engines problems were soon identified, and she was towed the next day to the Brooklyn Navy Yard. Once fixed, USS Monitor was ordered to proceed right away to Hampton Roads, on 26 February. Her departure was delayed as she waited for ammunition. She departed on 27 February, entering the East River and left New York. Underway her captain found her however “unsteerable”. She had to be towed back to the navy yard for modifications. Ericsson found the steering gear was improperly installed. It was proposed to realign the rudder, causing a 24h delay, but Ericsson preferred adding an extra set of pulleys, which was quick. This was a success as shown by the 4 March trials, as well a gunnery trials. Gunnery officer Stimers however failed to understand Ericsson’s complex recoil mechanism, loosening them so much they hit the back of the turret twice.

All in all, the revolutionary Monitor was created with no less than forty patented inventions and the “boom time” of the Civil War allowed Ericsson to have his concept multiplied by the Navy, and could have made a fortune. But instead, he just U.S. government all his patent rights as a personal “contribution to the glorious Union cause”. After all, he was Swedish-born and like many foreigners, wanted to show his patriotic fervor, but financially, this was not that judicious.

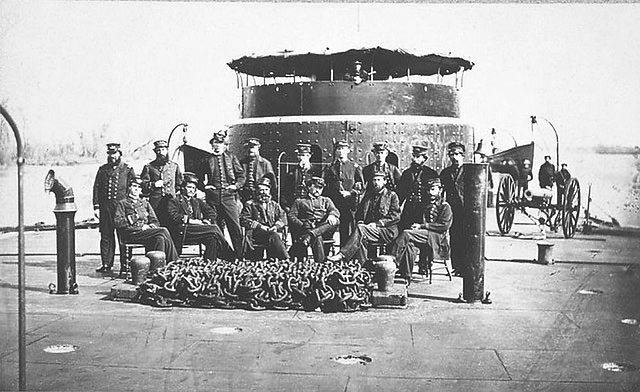

Detail of her first crew

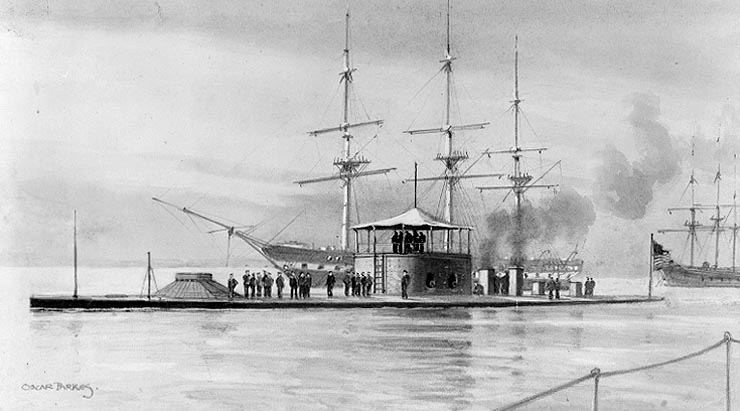

Officers on deck, posed by her armored gun turret, while the ship was in the James River, Virginia, 9 July 1862

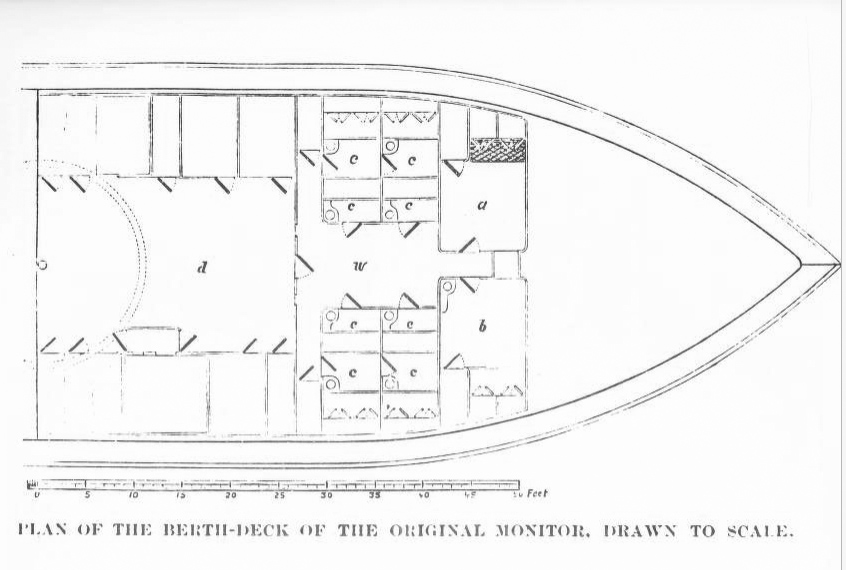

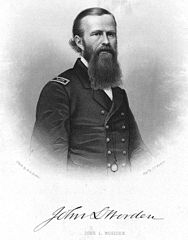

USS Monitor’s crew volunteered rapidly, with ten officers and 39 enlisted men. There was a commander, Lieutenant John Lorimer Worden, an executive officer, Lieutenant Samuel Greene and third Assistant Engineer Robinson W. Hands, four engineers, one medical officer, two masters and a paymaster assembled by Worden. There were Line officers, responsible for the vessel’s handling and artillery, and separate engineering officers. The turret housed gunnery officers Greene and Stodder, which supervised loading and firing, with eight men under them in the crowded turret. Worden’s report (27 January 1862) stated that the turret, still could house as much as 17 men and 2 officers.

Living quarters for senior officers comprised eight separate well-furnished cabins with table and chair, oil lamp, shelves and drawers, canvas floor and rug. Suspended goat-skin mats were provided for the rest of the crew. Small skylights practiced in the deck above provided lighting, all covered by an iron hatch during battle so the ship became so dark as force the use of oil lamps. The officer’s wardroom was placed forward of the berth deck, used as mess, well furnished. Ericsson paid for all costs of these personally.

Many details about the crew were found in the recovered items in the wreck, giving an insight on everyday life onboard and cluses about the personal crew’s life. The correspondence of George S. Geer “The Monitor Chronicles” were preserved on land however, also providing many details, as a sailor’s experience onboard, offering more insight about the many issuies and incidents onboard. They are now at the Mariners’ Museum in Virginia. Louis N. Stodder, a survivors and last man to abandon Monitor also gave precious clues about the ship’s demise.

Officers posing in front of the turret after refit, showing the added roof top protection and command CT.

USS Monitor in service

Early service, Fort Monroe

On 6 March 1862 at last, USS Monitor was declared ready for operational service and sailed out of New York for Fort Monroe in Virginia. To spare her coal, she was towed by an ocean-going tug, USS Seth Low. She was escorted also by the gunboats USS Currituck and Sachem. Captain Worden had serious doubts about the seal between the turret and hull and not following Ericsson’s advice her wedged the turret un fixed, up position, stuffing oakum and sail fabric into the gap.

During the windy noght, water washed away the oakum and soaked the fabric, so it was literraly raining under the turret. The hawsepipe, hatches, ventilation pipes, and funnels (two small ones) also leaked. The belts for the ventilation and boiler fans also loosened and fell off, almost stopping steaming and creating a toxic atmosphere in the engine room. Eventually the crew had to be evacuated on deck as ordered by First Assistant Engineer Isaac Newton. The most afflicted were handed over the top of the turret and laying there to recover. Newton and Stimers meanwhile tried to reactivate frantically the blowers, until they succumbed and were taken above. One brave fireman holed the fan box and drain the water in order to restart the fan.

Mishaps were not over yet as later Later the wheel ropes which controlled the rudder jammed, just when the ship was going into rough seas. In danger of foundering, Worden signaled the tug to help her keeping course, and she was towed to calmer waters, cose to shore laying there to restore full power. The following day, 8 March, before noon, she rounded Cape Charles, entering Chesapeake Bay and arriving in sight of Hampton Roads at around 9 PM. It was well after the first Battle of Hampton Roads, where Virginia made a carnage, engaging first the USS Cumberland, left crippled, burning, and rammed. After what she sank in shallow waters. USS Congress’s captain was so afraid he order his frigate into shallower water to be beached right away and later under heavy fire, surrendered.

The Virginia’s scare

Comparison virginia-monitor

Days before the battle, a telegraph cable was sent from Fortress Monroe overlooking Hampton Roads to Washington about the estimated arrival of the CSS Virginia, spotted en route. It was feared she would also bombard New York or ascend the Potomac River and attack Washington itself. President Lincoln held an emergency war council with Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, Wells and other senior naval officers. Stanton knew about USS Monitor’s issues and only two guns, and was appealed by the prospect of loosing her at the first engagement.

Admiral Dahlgren however reassured the audience that the confederate ironclad was too massive to approach Washington and that USS Monitor was more than capable to challenge her effectively. Lincoln sent many warning telegrams afterwards to governors and mayors of coastal states which tried to evacuate their most previous assets and have shore batteries ready when possible. Stanton approved an officer’s plan to sent sixty canal boats loaded with stone and gravel to block the Potomac. However Welles convinced not to do it; and at least to wait confirmation CSS Virginia would enter the Potomac.

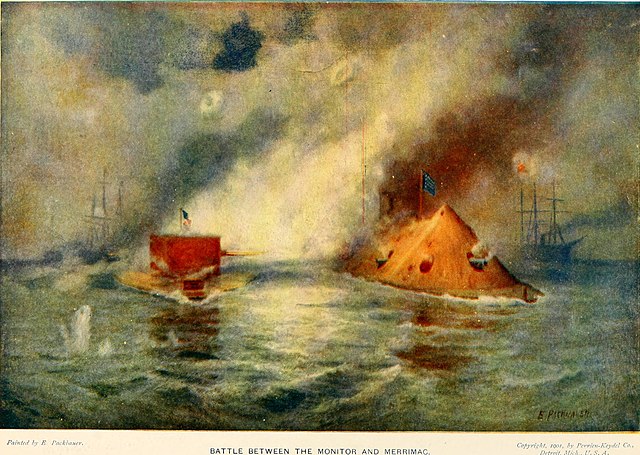

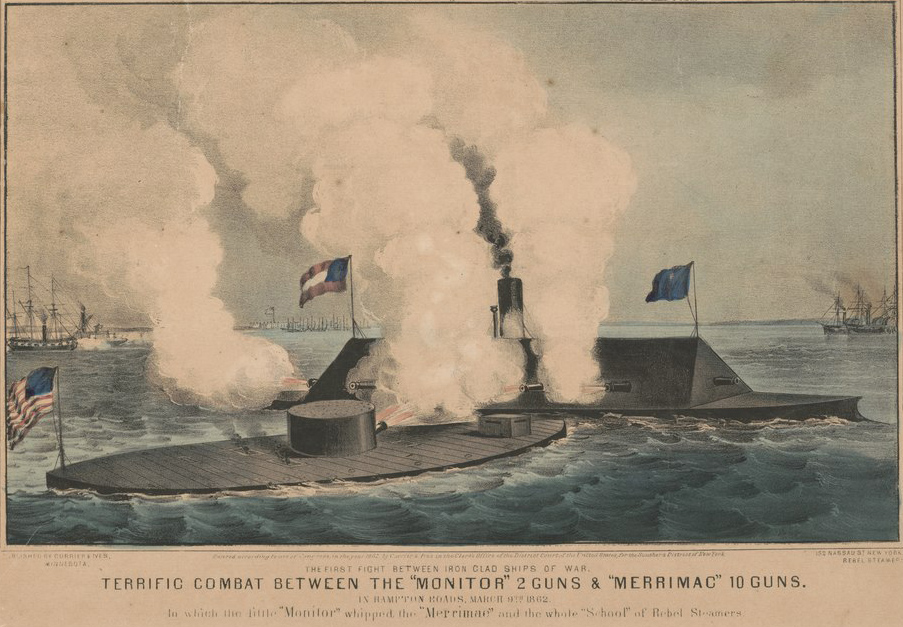

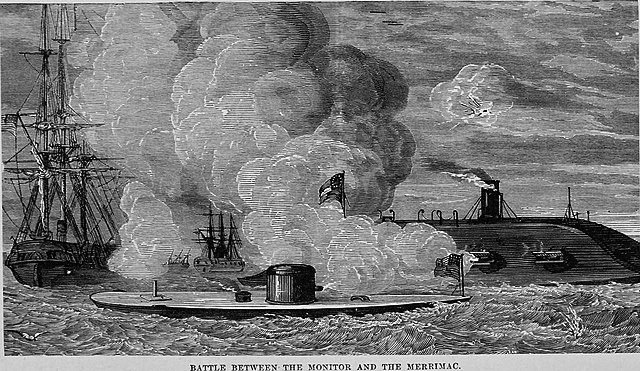

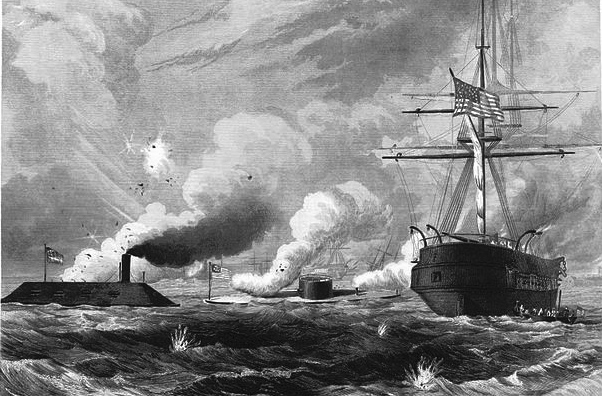

The battle of Hampton roads (8 March 1862)

Battle of Cape Hatteras

On this 8 March 1862 CSS Virginia (Commander Franklin Buchanan, chief engineer H. Ashton Ramsay) also scared the steam frigate USS Minnesota, which ran aground while attempting to engage her, remaining stranded. However when sighting the Monitor, CSS Viriginia was not Unscathed: Her port side anchor was lost, bow leaked with a mushed port side half by a lucky shot and she had many punctures and superficial damage from all the bouncing projectiles from USS Cumberland, Congress, and shore-based Union batteries. She lost her smokestack had two broadside cannons out of commission, many armor plates disjointed or loosened and her two cutters blow away plus her deck’s 12-pdr anti-boarding howitzers. She also had her deck stanchions, railings and flagstaffs destroyed. Captain Buchanan was injured and later relieved of command by Catesby ap Roger Jones. He ordered an attack on the stranded USS Minnesota but the ironclad had now a 22-foot draft due to leakages and a too slow speed to manoeuver. The idea was to retire to her supply fleet during the night repair and return the following morning to finish the job.

At 9:00 pm, at last, USS Monitor arrived on site, spotting the smoke of two ships burning, and the smokestack of CSS Virginia. Captain Worden initial ordered were to anchor alongside USS Roanoke and report to John Marston, briefed of the situation and then protect USS Minnesota, stranded. At midnight USS Monitor arrived alongside USS Minnesota and the crew just waited. The next morning, at 6:00 am CSS Virginia arrived with her support fleet (CSS Jamestown, Patrick Henry and Teaser) rounding Sewell’s Point and soon on sight of USS Minnesota and other blockaders, at slow speed due to the shoals and heavy fog. She only arrive at gun distance around 8:00 am, as the folg lifted.

In USS Monitor, Worden was looking out from the pilot house, the whole crew in battle order. Greene took command of the turret. Samuel Howard (Acting Master of USS Minnesota) was onboard due to his familiarity with Hampton Roads preculiarities, as pilot. Quarter Master Peter Williams steered the ship during the battle (later to be given the Medal of Honor), communicating via the speaking tube between the pilothouse and turret was out of order so commands were relayed from Worden to Greene. CSS Virginia at first concentrated on USS Minnesota from a mile but making few hits. Greene sent Keeler to the pilot house and request to open fire asap, Worden insisting upon “to take sure aim and not waste a shot.”

USS Monitor 1862

Merrimack and Monitor

Combat of giants

USS Monitor made a surprise appearance, emerging from behind Minnesota to interpose in front of the latter and protect it fromm CSS Virigina. At 8:45 am order was given to order fire, point blank, on the Confederate vessel. Then started the famous “ironclads dance” as they harmlessly fired on each others without any consequence, turning close to one another. USS Monitor fired solid shot at an appaealing rate of a volley every eight minutes, Virginia fired shells, a bit faster due to having more guns to bear. This “dance” went on for about four hours. It ended at 12:15 pm as the range opened gradually to several miles. Virginia’s weak engines and inferior agility, and Monitor’s turret meant she could aim at leisure while Virginia was lumebering out to try to present her broadside. She difficult to maneuver in the shallows and made a 180° turn in 30 minutes.

USS Monitor’s turret started to malfunction when the first shells bounced on her, turned with difficulties or even stopping at times. Alas, the crew simply let the turret continuously turn, firing their guns “on the fly” when finding the right spot. Direct hits on the turret causing bolts to shear off, ricocheting inside and making wounds, while the deafening impact noise, ringing the turret like an enclose bell, stunned the crew, causing nose and ear bleeding.

After four hours, neither ship took the advantage. It ws a time where armour was clearly superior to gunnery. Towards the end, CSS Virginia’s captain lost patienced and attempted to ram but the nimbler and faster Monitor dodged the manoeuver and only had a glancing blow making no no damage. That collision however further torned down Virginia’s bow, already in poor shape after her ramming of USS Cumberland. The little damage made by Monitor on Virginian were latter attributed to the protection of the latter, but also the guns firing with reduced charges as adviced by Commander John Dahlgren, the gun’s designer and manufacturer. The latter however had no clues about defeating iron plates, which was brand new. Stodder, at the wheel and controlling the turre was knocked him clear by an impact as he layed on the side. He was later recover and relieved by Stimers.

The two ships also collided five times from several accounts. At 11:00 am already, USS Monitor’s ready round ammunition (inside the turret) were exhausted and the gun port covers were jammed shut to resupply and repair the damaged hatch. At some point Captain Worden climbed through the gun port for a better look and spotted Virginia, seeing Monitor distancing for her resupply, turned her attention to USS Minnesota, making her ablaze as well as skinging the tugboat Dragon. Worden ordered back to battle as sson as possible. Towards 12:00 Worden wanted to try destroying the Confederate ship’s tern, but this was prevented by Lieutenant Wood on board Virginia, furing a 7-inch Brooke gun at USS Monitor’s pilothouse. As a result, Worden was made blind by the impact and shell fragments, gunpowder residue. He ordered to escape to the shallows and she drifted idly for about twenty minutes, Samuel Greene eventually taking command, undecided about the action, unti he ordered to return to the fight.

CSS Virginia tried to follow USS Monitor and as expected, ran aground. After seeing the poor results of her artillery, order was given by Jones to stop firing, as a waste of ammunition. She later managed to free herself and break away, towards Norfolk for repairs. It was assumed Monitor withdrawn and the battle was won. Greene let this happen, not chasing her. He stuck to orders to stay with USS Minnesota, which was later criticized by some.

Aftermath of the battle

Soty of the confederate state, USS Monitor

Accounts were made on both ships and reports written. USS Monitor was struck twenty-two times, including nine to the turret, two hits to the pilothouse. She fired forty-one shots in all. Virginia took ninety-seven indentations but this was the sum of Monitor and other ships, plus coastal batteries. Damage was still insignificant, apart the bow of Virginia. Commander Jones estimated USS Monitor could have sunk them if hit at the waterline. On the strategic level, this battle was considered the most definitive naval battle of the Civil War.

Although a draw, with Virginia taking slightly more damage but the Union suffering more losses from the previous battle, the Confederates were quick to announce a victory. USS Monitor defended USS Minnesota as ordered and repelled Virginia, enabling the rest of the Union blockading force to stay and resulme the blockade and conversely the Confederate vessel was unable to break it, so making this battle a strategic victory for the Union. Historically of course it marked a turning point in naval warfare. This was the first fight between ironclad, a brand new type of ship that would dominate the seven seas until 1945.

“Monitor fever” in the North led to the construction of improved designs and about 60 ironclads were built and unleashed on the south, especially to win several river engagement and ultimately shell to oblivion several significant cities, largely contributing to the final victory.

Immediately after the battle, Stimers sent a congratulation telegram to Ericsson, for “saving the day” with his design. When USS weighed anchor she was greeted by a fleet of enthusiastic small boats while a massive crowd of equally extatic spectators gained momentum on shore. The crew, as soon as they disembarked were greeted with cheers for their assumed victory over Virginia. Assistant Secretary Fox was an observer that day from USS Minnesota, and came aboard Monitor to tell the officers “Well gentlemen, you don’t look as though you just went through one of the greatest naval conflicts on record”. A blinded Worden carried out as well as other wounded sailors, still under the cheers to Fort Monroe and then an hospital in Washington.

Stimers and Newton assessed, then repaired battle damage as soon as possible. They repaired the pilot house and its slopes to 30° and readjust disjointed plates, hammering some back into shape. Mrs. Worden also personally brought news of her husband during that time, to the relief of officers working on the Monitor. Her would eventually recover his eyesight. President Lincoln personally visited Worden. He later spent the summer home in New York but was unconscious for three months, later brought back to command USS Montauk, a brand new monitor, until the rest of the war.

The Confederates also cheered as CSS Virginia came along the banks of the Elizabeth River, a huge crowd gathered, cheering and waving flags, handkerchiefs and throwing hats. Virginia indeed also managed to captured the ensign of Congress during the previous battle amonf floating debris. The Confederate government promoted Buchanan to Admiral and congratulated the crew. Soon, both government made plans of course for new Ironclads. It was much easier for the industrial north, but the south had to improvize, using notably railway traverses. The Union Navy chartered the converted sidewheeler USS Vanderbilt, reinforcing her bow to be used as naval ram nd stationed permalently at Hampton Roads.

11 April 1862: 3rd battle of Hampton Roads

Engraving of the battle

On 11 April, CSS Virginia indeed steamed into Hampton Roads, Sewell’s Point (southeast edge) to try to lure USS Monitor into battle again, fired a few shots at very long range while her opponent returned fire but remained near Fort Monroe, under the added protection of its batteries. She was in position to ram Virginia if approaching, but it never happened. The Confederateplan was to board USS Monitor to capture her, hoping to bring her back under Confederate control using the the James River Squadron. The latter prepared three captured merchant ships, brigs Mand a schooner, hoisting “Union-side down” to taunt USS Monitor, but this failed and Viriginia eventually departed away.

The plan was to attack USS Monitor with the James River Squadron, landing a party aboard, and either her had in tow or disabling her turret using heavy hammers, covering the pilothouse with a wet sail, while throwing combustibles down the ventilation and smoke openings. There was an ultimate encounter between the vessel, on 8 May, CSS Virginia sailing towards Monitor, which with four other Federal ships shelling the Confederate batteries at Sewell’s Point. Upon seeing the approaching Virginia, they were signalled to retire slowly to Fort Monroe, to lure her out into the Roads, but she did not followed. Instead she anchored off Sewell’s Point. When Norfolk fell on 11 May 1862, however, the Confederate troops were ordered to burn down and destroy CSS Virginia.

Battle of Drewry’s Bluff (12 May 1862)

Battle_of_Drewrys_Bluff

After the loss of CSS Virginia, USS Monitor supported the General McClellan’s campaign against Richmond. By that time she was under command of Thomas O. Selfridge, later relieved by Lieutenant William Nicholson Jeffers (15 May 1862). USS Monitor was the centerpiece of a flotilla under command of Admiral John Rodgers, aboard the other Union armoured ship, the Bushnell’s USS Galena, and three other gunboats. They steamed up the James River, dealing on the way with Confederate batteries at Drewry’s Bluff, until they were silenced.

Meanwhile, this was cooridnated with McClellan’s push on land, towards Richmond. It was scheduled that the flotilla would present there and bombard the city into surrender. They arrived within 8 miles (13 km) of the Confederate capital but were barred to go further as the Confederate had sunken seeral vessels and other debris across the river. Once stopped, they were dealt by Fort Darling’s batteries, which were waiting for them. Also the Confederate had placed several other heavy guns unde corver on the shores and sharpshooters were also positioned along the banks.

The fort controlled the west bank of the James River, placed atop of a bluff towering 200 ft (61 m) above which gave them excellent visibility and parabolic fire potentially deadly for the weakly protected USS Monitor. The latter could not bring her guns to bear, having a too short elevation. She soon had to fall back to be able fire at a greater distance, loosing accuracy. Gunboats however dealt with the fort. USS Monitor received a few hits, but with little damage, and was mostly spared by Confederate officers which preferred to focus on USS Galena and the other gunboats. They all took quite a punishment, with some casualties, in a four-hour artillery duel. In the end, it was ordered to the flotilla to retire, unable to silence the fort. In fact, the fort deter any approach via the Jamanese river until the end of the war. Richmond was evecuated and captured by land.

After the battle at Drewry’s Bluff, USS Monitor stayed as a vigil on the James River, providing support when needed, and teaming with USS Galena and other gunboats. They still provided support to McClellan along the river and this included a bombardment of Harrison’s Landing in August 1862. In between inactivity and hot weather crippled the crew’s morale. Some crew members were transferred to Hampton Roads and there was a turnover of officers. Commander Thomas H. Stevens, Jr was in command on 15 August. By the end of the month, USS Monitor was back to Hampton Roads, dropping anchor close to the wreck of USS Cumberland, at Newport News Point. She was then to blockade the James River, waiting for the newly constructed Virginia II.

USS Monitor’s overhaul

Model after refit

In September 1862, Captain John P. Bankhead took command, sent to Hampton Roads, but upon arrival, he was reported engines problems, later conformed by a board of survey. They recommended a full overhaul and on 30 September she was towed to the Washington Navy Yard, starting on 3 October. Upon arrival she became a premier tourist attraction in NYC, as the crowd was soon allowed on board. During the overhaul, various officials als payed her a visit. Lincoln also came to an official visit, with the whole crew present and Captain Worden. Soon after the crew was in action again onboard USS King Philip for the six weeks during which her bottom was scraped clean, engines and boilers were cleaned and scraped anew.

USS Monitor was repainted and every detail fixed, improvements made like the turret top iron shield and a 30-foot (9 m) smokestack over the smoke outlet and tall fresh air vents for a better ventilation. The berth deck was enlarged, but also made lower. Cranes were added and living condition improved. A new independent blower for the boilers was also installed, drawing air from and through the pilothouse. Stanchions were installed around the freeboard, roped along, making it safer to walk around in rough seas. ISS Monitor was out on 26 October and started sea trials afterwards, in November she was ready for service.

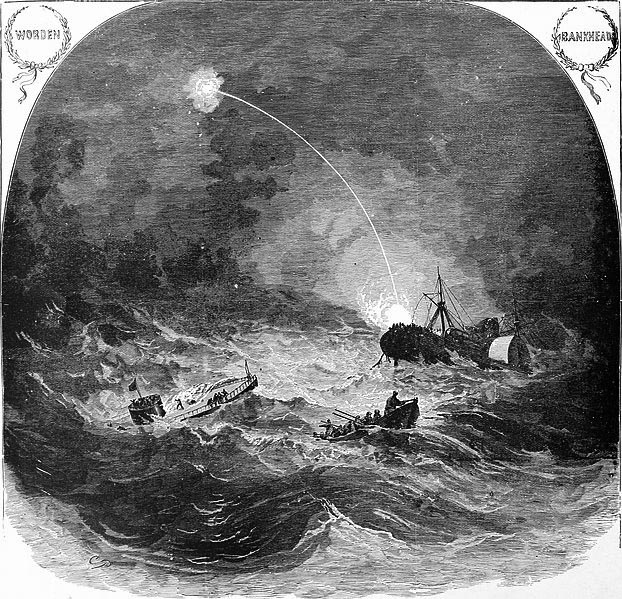

Final mission and sinking

USS Monitor at sea in heavy weather

On 24 December 1862 she was ordered to Beaufort, North Carolina, teaming with the brand new monitors USS Passaic and Montauk to support an army expedition to Wilmington, and blockading Charleston. It came about Chritsmas and sispleased the crew, some thinking she was not ready for the open sea voyage. Christmas was celebrated while she stopped at Hampton Roads. In provate, officers however worried about their ship to be unseaworthy in rough waters. The Captain John P. Bankhead under orders trie to reassure them, but probably thinking too that sailing out by in this season was not good business. USS Monitor departed again on 31 December but under tow to spare coal, by USS Rhode Island, just as a heavy storm developed off Cape Hatteras.

Soon the storm became intense and large waves started splashing over the deck, entering by the pilot house. The crew rigged the wheel atop the turret and helmsman Francis Butts evacuated his post. Flooding via all vents and ports continued while the ship started rolling badly. Son also she started rocking heavily in larger waves, crashing and ploughing heavily, shaking in the process. Leaks appeared soon, and Captain ordered all hands to try to fix them as they appeared. But itsoon appeared as an uphill battle.

Frank Leslie’s scenes and portraits of the Civil War, loss of uss monitor

The Worthington pumps momentarily stemmed the flood, but a squall shook the ship, and larger waves came crashing so only making matters worse. Eventually the Worthington pumps were overwhelmed and the engine room was soon flooded beyond safe level. Bankhead signaled her tug USS Rhode Island she needed help, hoisting the red lantern, and ordered the anchor dropped, to stop rolling and pitching; But this had little effect. Frm the tug, rescue boats tried to get close and a towline was cut, volunteers were called on deck. Stodder, John Stocking, James Fenwick climbed down from the turret, but swept overboard and drowned. Stodder however installed safety lines around the deck and cut the 13 in (33 cm) towline with his hatchet. At 11:30 pm, Captain Bankhead ordered engineers to shut the machinery, divert all steam to the large Adams centrifugal steam pump. However this was not sufficient due to the reduced steam output from wet coal. The steam pumps failed and now hand pumps and a bucket brigade were ordered, but too late;

Greene and Stodder were the last to abandon ship with Bankhead, the last surviving to abandon ship. The official report at the Navy Department would praise their heroic sacrifice. The frantic rescue effort paid off, as Forty-seven were saved, but still, USS Monitor sank 16 miles SE off Cape Hatteras, carrying with her sixteen men, notably four officers remaining in the turret. They were picked up onboard USS Rhode Island. The Navy, which ordered this mission without knowing about the deteriorating weather did not created a board of inquiry and closed the affair as a common sea fortune in wartime.

Nevertheless a controversy would later emerged, not in small part because of Ericsson accusing the crew of drunkenness. Stodder defended the crew, accusing him in return to “covers up defects by blaming those that are now dead”, and pointing out the unseaworthiness of the ship and sea conditions. He also pointed out the the overhang between the upper and lower hulls came loose and even partially separated, which was corroborated by other shipmates.

Recovery and preservation

2000s salvage operations: The turret is pulled out of water by the “spider” system.

The Navy sent an “underwater locator” in August 1949 south of the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse to try to locate her wreck. She was eventually found under 310 feet (94.5 m) of water but investigation was marred by local powerful currents. Ret. Rear Admiral Edward Ellsberg proposed external pontoons to raise her wreck in 1951. Later in 1955, Robert F. Marx claimed the wreck had drifted into shallow water north of the lighthouse and that he had dived on the wreck.

The Duke University associated to the National Geographic Society and National Science Foundation financed an expedition in August 1973 using a modern towed sonar system. On 27 August she was at last located, after 111 years, and a camera was soon down to photograph her, but images appared too fuzzy. Another was lost. The sonar images eventualy told the ship was upside down. The discovery was announced on 8 March 1974 and another expedition was mounted to confirm it and sent the submersible Alcoa Sea Probe, making a video confrming the find.

They showed the wreck was disintegrating and since she had been formally abandoned in 1953, private divers or salvage companies could pillage her. In order to preserve the wreck, a 0.5-nautical-mile (0.93 km; 0.58 mi) was designated as the “Monitor National Marine Sanctuary” the first in fact, on 30 January 1975. Soon it was designated a National Historic Landmark on 23 June 1986. The recovery costs were deemed impossible in the 1970s. but in 1995, the NOAA divers tried to raise her propeller, but failed due to the stormy season. NOAA soon developed a plan to recover the most significant parts of the ship: Engine, propeller, guns, and turret for 20 million dollars and over four years.

The propeller was lifted on 8 June 1998, but work wa smade in difficult conditions and the 1999 dive season was a comprehensive study for better planning. In 2000 installed bags of grout, the engine recovery system framework for the next seaons in 2001, trying to recover the steam engine and condenser, on 16 and 19 July. Saturation diving was used and in 2002 the 120 ton turret was recovered using a large, eight-legged lifting frame, from 26 July to 5 August 2002. A skeleton was discovered in it. Remains of other sailors were transferred to the Accounting Command (JPAC) at Hickam Air Force Base in Hawaii for identification. Some were identified and on 8 March 2013 buried at Arlington National Cemetery with full military honors. The propeller is now on display in the Monitor Center at the Mariners’ Museum. Conservation of the rest is ongoing and the Dahlgren guns were removed in September 2004. The red signal lantern was also recovered. Northrop Grumman Shipyard also constructed a full-scale static replica, placed on the grounds of the Mariners’ Museum. The 150th anniversary of her loss prompted several events on 29 December 2012.

Src/Read More

Links

The steam navy of the United States : a history of the growth of the steam vessel of war in the U.S. Navy, and of the naval engineer corps

Drawings of the USS Monitor (archive NOAA)

Ironclad : the Monitor and the Merrimack by Mokin, Arthur, 1923

Monitor Builders: A Historical Study of the Principal Firms and Individuals Involved in the Construction of USS Monitor

monitorcenter.org

On ibiblio.org, onboard life photos and crew, DEPARTMENT OF THE NAVY — NAVAL HISTORICAL CENTER

More Photos on history.navy.mil

DTIC ADA033069: Project Cheesebox: a Journey into History. Volume 1

DTIC ADA033070: Project Cheesebox: a Journey into History. Volume 2

DTIC ADA033071: Project Cheesebox: a Journey into History. Volume 3

NOAA the exploration of uss monitor’s wreck

NOAA, the 2002 Monitor’s retrieval expedition

The Original United States Warship “Monitor.”: Copies of Correspondence Between the Late Cornelius S. Bushnell…

The Monitor and the Merrimac; both sides of the story by Worden, John Lorimer, 1818-1897

Diary of Gideon Welles: Secretary of the Navy Under Lincoln and Johnson, Volume 1

Diary of Gideon Welles

Wiki

Videos

The USS Monitor, Wide Awake Films

Drachinifel’s Battle of the Hampton Roads – The Fury of Iron and Steam

TV Movie Monitor vs Merrimack, the battle of Hampton Roads

The USS Monitor and NOAA: A Look Through Time.

USS Monitor, Carl Alessi

USS Monitor Center Documentary, The Mariners’ Museum and Park

Greatest Mysteries of the Civil War: The Lost Ironclads and Submarines

Books

Navsource.org – Comparison Virginia – Monitor

Anderson, Bern (1989). By Sea and by River: The Naval History of the Civil War. Da Capo Press.

Ballard, G. A., Admiral (1980). The Black Battlefleet. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-924-5. 261 pages.

Baxter, James Phinney, 3rd (1968). The Introduction of the Ironclad Warship, Archon Books

Bennett, Lieutenant, U.S. Navy, Frank M. (1900). The Monitor and the Navy under steam. Houghton, Mifflin

Broadwater, John D. (2012). USS Monitor: A Historic Ship Completes Its Final Voyage. Texas A&M University Press.

Canney, Donald L. (1993). The Old Steam Navy. Vol. 2: The Ironclads, 1842–1885. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press.

Clancy, Paul (2013). Ironclad; The Epic Battle, Calamitous Loss, and Historic Recovery of the USS Monitor. Koehler Books

Chesneau, Roger; Kolesnik, Eugene M., eds. (1979). Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships 1860–1905.

Davis, William C. (1975). Duel Between the First Ironclads (Book club ed.). Doubleday.

‘USS Monitor Can Be Raised,’ Says Top Underwater Salvaging Expert”. The Harvard Crimson.

Dinsmore, David A; Broadwater, John D. (1999). “1998 NOAA Research Expedition to the Monitor National Marine Sanctuary”.

Field, Ron (2011). Confederate Ironclad vs Union Ironclad: Hampton Roads. Osprey Publishing.

Gentile, Gary (1993). Ironclad Legacy: Battles of the Uss Monitor. Gary Gentile Productions.

Holloway, Anna (2013). The Last Voyage of the USS Monitor (PDF). The Mariner’s Museum.

Holzer, Harold; Mulligan, Tim (2006). The Battle of Hampton Roads: New Perspectives on the USS Monitor and CSS Virginia. Fordham University Press.

Konstam, Angus (2002). Hampton Roads 1862: First Clash of the Ironclads. Osprey Publishing.

Konstam, Angus (25 January 2002). Union Monitor 1861–65. Osprey Publishing.

Mariners’ Museum. “Last Voyage of the Monitor: December 24th – Forward”.

Nelson, James L. (2009). Reign of Iron: The Story of the First Battling Ironclads, the Monitor and the Merrimack.

Park, Carl D. (2007). Ironclad Down: The USS Merrimack-CSS Virginia from Construction to Destruction.

Quarstein, John V. (1999). The Battle of the Ironclads. Arcadia Publishing.

Quarstein, John V. (2006). A History of Ironclads: The Power of Iron Over Wood

Quarstein, John V. (2010). The Monitor Boys: The Crew of the Union’s First Ironclad..

Quarstein, John V. (2012). The CSS Virginia: Sink Before Surrender. The History Press.

Rawson, Edward K.; Woods, Robert H. (1897). Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion.

Roberts, William H. (2002). Civil War Ironclads: The U.S. Navy and Industrial Mobilization.

Still, William N. (1988). Hill, Dina B. (ed.). Ironclad Captains: The Commanding Officers of the U. S. S. Monitor.

Thompson, Stephen C. (1990). “The Design and Construction of the USS Monitor”. Warship International.

Thulesius, Olav (2007). The Man who Made the Monitor: A Biography of John Ericsson, Naval Engineer.

Brooke, John Mercer (2002). Ironclads and Big Guns of the Confederacy: The Journal and Letters of John M. Brooke.

Bushnell, Cornelius Scranton; Ericsson, John; Welles, Gideon (1899). The original United States warship “Monitor”.

Dahlgren, Madeleine Vinton (1882). Memoir of John A. Dahlgren, Rear-admiral United States Navy. J. R. Osgood.

Green (USN), Lieutenant Samuel Dana (1862). “An Eye-Witness Account of the Battle Between the U.S.S. Monitor and the C.S.S. Virginia”

Rawson, Edward K., Superintendent Naval War Records; Woods, Robert H. (1898).

Welles, Gideon (1911). Diary of Gideon Welles, Secretary of the Navy Under Lincoln and Johnson.

Worden, John Lorimer; Greene, Samuel Dana; Ramsay, H. Ashton; Watson, Eugene Winslow (1912). The Monitor and the Merrimac

Bennett, Frank Marion; Weir, Robert (1896). The Steam Navy of the United States. Warren & Company

Mokin, Arthur (1991). Ironclad: the Monitor and the Merrimack. Presidio Press.

Peterkin, Ernest W. (1985). Drawings of the U.S.S. Monitor: A Catalog and Technical Analysis. NOAA

Sheridan, Robert E. (2004). Iron from the Deep: The Discovery and Recovery of the USS Monitor.

Snow, Richard (2016). Iron Dawn: The Monitor, the Merrimack, and the Civil War Sea Battle that Changed History.

Still, William N., Jr. (1988). Iron Afloat: The Story of the Confederate Armorclads

Still, William N., Jr. (1988). Monitor Builders: A Historical Study of the Principal Firms and Individuals Involved in the Construction of USS Monitor.

Welles, Gideon (1911). Thaddeus Welles (ed.). Diary of Gideon Welles, Secretary of the Navy Under Lincoln and Johnson. Houghton Mifflin Company.

The model’s corner

General query

Dumas 1/72 (with virginia), same cardboard model, Proarte-Modelarstwo Kartonowe 1:200/1:350. Same Lindberg 1:245/1:350, LIFE-LIKE Hobby Kits 1:297, Pyro 1:297, Atlantis 1:360, ROP o.s. Samek Models 1:700, Lindbergh Monitor 1:210, Merrimac 1/300.

Mikro-Mir 1/144

Flagship Models | No. FM19200 | 1:192

1/192 model – flagship models

Union Navy

Union Navy

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign