French Navy Pre-Dreadnought Battleship (1898-1907)

French Navy Pre-Dreadnought Battleship (1898-1907)WW1 French Battleships:

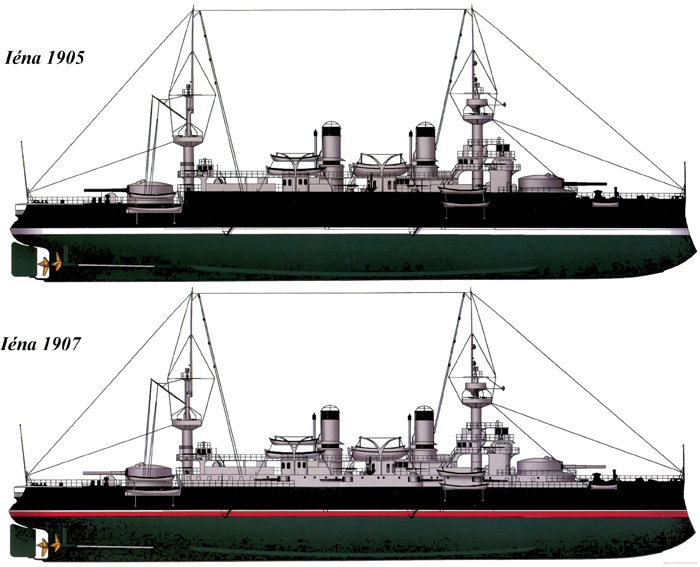

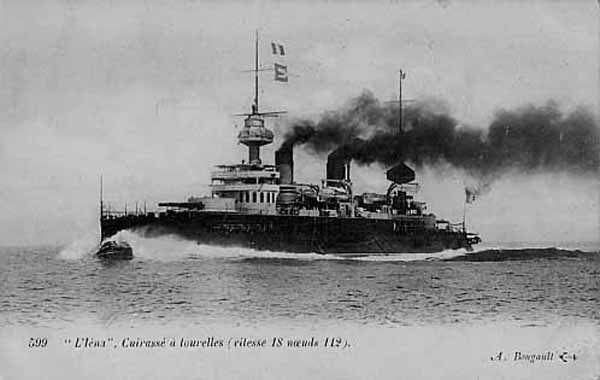

Duperre class | Terrible class | Amiral Baudin class | Hoche | Marceau class | Charles Martel class (1891) | Charlemagne class | Henri IV | Iena | Suffren | Republique class | Liberté class | Danton class | Courbet class | Bretagne class | Normandie class | Lyon classIéna was ordered in April 1897, and completed in 1902, based on the relatively successful previous Charlemagne class. Although still caracteristic of the earlier designs with a pronounced tumblehome, Iéna adopted the classic international two 12-in (305 mm) gun turrets configuration of the time, but was still relatively slow, and slightly better protected as per the armour weight ratio. Unfortunately, she would never see WWI as she was gutted in a serie of catastrophic explosions in 1907 due to secondary guns propellants self-igniting while in drydock maintenance, followed by a thorough investigation and drastic safety measure concerning black powder charges aboard.

On the wake of the Charlemagne class

Part of the late part of the “Young School” era, Iéna was a pre-dreadnought battleship based on the Charlemagne class, but larger. Some historians tend to artificially link her to Suffren (launched 1899), but they were two very different ships (and will be treated that way). The only thing they had in common was they were the last French pre-dreanoughts before reforms came in. The subsequent Republique and Patrie class were truly a revolution, more homogeneous vessels of a new class entirely.

Iéna was completed on 14 April 1902, after four full years of design revisions for her (very lenghty) completion. She was assigned to the Mediterranean Squadron, alternating as flagship with Suffren and participating in annual fleet manoeuvres. In 1907, while docked for a refit, there was an accidental magazine explosion which destroyed her, killed 120 workers and sailors onboard and led to a thorough enquiry. It appeared that it was most likely cause by the decomposition of old “Poudre B” propellant. The scandal forced the Navy Minister to resign, and the commissioned estimated she was now obsolete and her salvaged hulk was used as target and sold for scrap in 1912.

On 11 February 1897, Navy Minister Armand Besnard confered with the Supreme Naval Council over the next design, seeking a larger Charlemagne-class with a displacement set at 12,000 tonnes (11,810 long tons). It was also question of a better armour scheme in order to preserve stability and buoyancy even after shells prenetrating the hull and causing flooding. The new battleship also had to be on par for armament with all foreign battleships and keep a top speed of 18 knots (33 km/h; 21 mph) with 4,500 nautical miles (8,300 km; 5,200 mi) of range.

The Director of Naval Construction Jules Thibaudier proposed his older preliminary design, showing a scheme incorporating improved Harvey armour, with a a highr belt armour above the waterline and a secondary armament of 164.7-millimetre (6.5 in) guns. Thibaudier submitted his revised design on 9 February 1897. It was approved by the Board of Construction on 4 March 1897, with minor revisions. The ship was then ordered on 3 April 1897 and the contract was submitted to Arsenal de Brest on the Atlantic coast (Britanny). She was laid down of 15 January 1898 and for once, launched rapidly, in September the same year.

The problem was a change at the head of government, meaning also a change of ministry and many design revisions which delayed her construction of four full years. Completed (“armement définitif”) indeed only came on 14 April 1902 at a cost of F25.58 million, far more than expected. Iéna ws the embodiement of everything wrong with French battleships of that era. With a completion that late, she was already obsolescent, and her early trials revealed many problems that had to be cured, so she spent many months at dock or in drydock (see career).

Design development

Iéna after commission off Toulon

Design development and construction

Iéna (Jena–Auerstedt), named after a Napoleonic Victory in Germany, in its origin, went back to a request of design dated 11 February 1897, by Navy Minister Armand Besnard, after consultations with the Supreme Naval Council. The idea was for an an enlarged Charlemagne-class battleship, to 12,000 tonnes (11,810 long tons). It needed also to have a better armour scheme capable of preserving both stability and buoyancy, even after several hiot at the waterline and flooding. The armament was a repeat essentially, and a match for foreign design, and the same fleet speed of the Mediterranean squadron at the time, 18 knots (33 km/h; 21 mph), plus a range of no less than 4,500 nautical miles.

The Director of Naval Construction Jules Thibaudier had been two month earlier preparing a preliminary design, to test the implementation of improved Harvey armour. His modificattions after receiving the request has been to increase the belt armour height above the waterline and replace the standard 138.6-millimetre (5.5 in) guns with 164.7-millimetre (6.5 in) guns, with more impact and longer range than the latter and actual 6-in guns used by other battleships.

Postcard of Iéna – from pinterest

Thibaudier submitted his revised design on 9 February 1897 already. Approved by the Board of Construction on 4 March 1897, only minor revisions were asked for before final submission for order. After these were done and the design resubmitted, the new battleships was officially ordered on 3 April 1897 and construction entrusted to Arsenal de Brest for a total Cost of F25.58 million including supplier’s armament, armour, and powerplant.

Iéna was eventually laid down on 15 January 1898, launched on 1 September 1898 and completed 14 April 1902. For once, construction was relatively swift compared to earlier 1890s standards, nearing ten years. The new direction at the head of the Navy indeed was well aware its designs needed to be completed fast in order not to be obsolete. Completion had been running for three years though, due to again, design revisions, the result as usual of changes in government and navy ministers that wanted to have their say.

Detailed design of Iéna

One one hand, having a much heavier displacement meant the possibility of improving many aspects of the design, but a lot was eaten by new dispositions taken to answer the main protection spec, compartimentation under the waterline, and no much space was allocated to the powerplant, which was more powerful, but due to the heavuer tonnage, was just barely able to deliver what was needed to reach 18 knots, not impressive compared to most pre-dreadnoughts of the time: The Duncan class (which mostly served in the Med) for example reached 19 kts, and 20 for the Italian Regina Margherita class.

Secondary armament was surprisingly heavy though, and compared well to the British 6-in guns of the time, and only eight were provided instead of twelve. This was compensated by eight lighter 100 mm (3.9 in), weaker but faster, nand limited to a 5.9 mi range, versus 7.8 for the 6-in guns, and 11 miles for the French 164 mm guns. The tertiary guns equivalent to the 12 pounder were twice as numerous also, twenty versus ten. This made for a slow, but overall heavily armed and slightly better protected than the average pre-dreanought in the Mediterranean.

Hull & general characteristics

Postcard of the previous Charlemagne – coll. Bougault from pinterest

She displaced 11,688 t (11,503 long tons) as designed, and 12,105 t (11,914 long tons) as planned deeply loaded. Her hull was 122.31 m (401 ft 3 in) long overall, for a beam of 20.81 m (68 ft 3 in) and less tumblehome as previous vessels, making her for a more favourable hull ratio and better speed. Her draught was 8.45 m (27 ft 9 in). She was seven meters longer, sixt centimeter beamier and about the same draft as the Charlemagne class.

She had large bilge keels, but roll pitched a lot, although both Captain Bouxin praised this at a sea-keeping point of view since these moves were predictable and gentle and she rode waves well, making her a good gun platform. She also manoeuvred well.

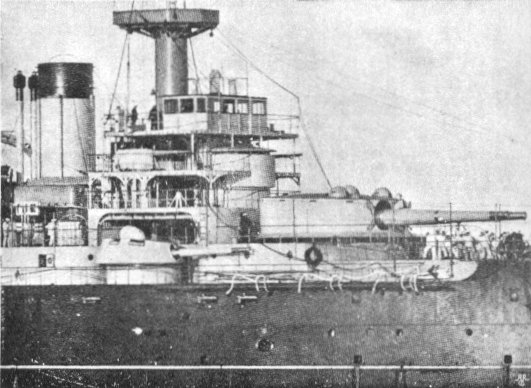

Construction was classic, with some limited ASW compartimentation below the waterline. Her silhouette also loosely resembled the previous Charlemagne, with the same complicated forecastle: It extended at full deck height up to the forward barbette, forming a redan, and then lowered from a meter up to the prow. The forward and aft turrets sat inside larger connical barbettes, supposed to deflect incoming rounds. Superstructure were limited to the main bridge forward, which sat on a two-level structure containing the coning tower, one deck above the forward turret.

Behind were located two funnels, in which pipes were truncated: A smaller round one immediately aft of the bridge, and a larger one amidship. At the rear immediately before the aft turret was the lighter and lower aft bridge. In between, there was a largely open structure at the upper gun battery, with gooseneck cranes and straps for her light service boats fleet of dinghies, cutters, yawls and steam picket boat. She had two main, thick military masts next to the bridges, with a large military top higher forward. The foremast also had a directing top surmounted by a projector. The crew comprised 727 officers and ratings but 33+668 as a “private ship”, and 731+48 as flagship.

Powerplant

Iéna was powered powered by 3 shafts of 4.5 metres (14 ft 9 in) (outer), 4.4 metres (14 ft 5 in) (centre) propellers, driven by three triple-expansion steam engines, fed in turn by 20 Belleville water-tube boilers working at a maximum operating pressure of 18 kg/cm2 (1,765 kPa; 245 psi), for a total of 14,500 PS (metric horsepower) or 10,700 kW. This was for a planned top speed of 18 knots (33 km/h; 21 mph). But her sea trials were not stellar: By using force heating at 16,590 metric horsepower (12,200 kW) on 16 July 1901, she just reached 18.1 knots (33.5 km/h; 20.8 mph).

For range, she carried 1,165 tonnes (1,147 long tons) of coal, enough for 4,400 nautical miles (8,100 km; 5,100 mi) at 10.3 knots (19.1 km/h; 11.9 mph) and she had an auxiliary 80-volt power unit with four dynamos, of respectively of a 600 and 1,200-ampere capacity. This was les than the 4,500 nautical miles (8,300 km; 5,200 mi) intended.

Protection

Her near sister ship Suffren (pinterest)

Iéna had a complete waterline belt made of Harvey armour, 2.4 metres (7 ft 10 in) high. From 12.6 in it tapered to 10.7 in at the bow, and 8.8 in at the stern. Below the waterline it was thinner at 120 mm (4.7 in) (bottom edge) and at the stern down to 100 mm (4 in). The upper armour belt had a lower 120 mm strake and upper 80 mm (3.1 in), combined on 2 metres (6 ft 7 in) high amidships.

There was for ASW protection underwater a well subdivided cofferdam filled by 14,858 water-resistant dried, compressed Zostera seaweed (“briquettes de zostère”) which expanded upon contact with water, hopefully pluging any holes. A sort of XIXth version of the “self-sealing tank”.

The armoured deck comprised a sandwich with a 65 mm (2.6 in) mild steel plate, placed over two 9 mm (0.35 in) plates and a splinter deck beneath also with two layers of 17 mm (0.67 in) plating each.

The turrets (in Harvey) were rounded, with flat walls 290 mm (11.4 in) thick topped by a mild steel roof 2 in thick and the Barbettes 9.8 in thick were also in Harvey armour with a deflector collar around on deck. The forward transverse bulkhead started at 55 and went on at the upper level to 150 millimetres (2.2–5.9 in) to enclose not the citadel, but the central battery. It fell to 2.2 in on the armoured deck. There was a single forward conning tower with thickness decrease from front to back and a 7.9 in communication tube below.

- Main belt: HA 320 mm (12.6 in)

- Outer Belt: 272 mm (10.7 in) fwd, 224 mm (8.8 in) aft.

- Underwater belt 4.7 – 4 in aft (120-100 mm)

- Upper belt: 4.7 – 3 in (120 – 75 mm)

- Armor Deck: 2.6-in +2x 0.35-in (65 +18 mm: 83 mm)

- Splinter Deck: 2x 0.67 in (34 mm)

- Main Turrets: 11.4 (290 mm) sides, 2-in (50 mm) roof.

- Battery Deck: 3.5 in (90mm)

- Bulkheads: FWD 5.9 in, Aft 2.2 in

- Secondary guns shields:

- CT: 11.7-in face, 10.2-in sides and aft

- Communication tubes below: 7.9 in (200 mm)

- ASW Compartment with seaweed bricks

Armament

2×2 305 mm (12 in) Schneider Creusot guns

The 40-calibre Canon de 305 mm (12 in) Modèle 1893–1896 gun were the same as for the Charlemagne class. They were manually elevated at −5° (loading) and +15° maximum, firing a 340-kgs (750 lb) APC shell (one per minute) at 815 m/s (2,670 ft/s). Max range was 12,000 metres (13,000 yd). 45 shells were in storage per gun, plus 14 ready rounds in each turret. The turret was powered by a 300-ampere dynamo for traverse and for the ammunition hoist.

8× 164.7 mm (6.5 in) Canet guns

These eight 45-calibre Canon de 164.7 mm Modèle 1893 guns were located on the the central battery, upper deck, with two installed on each side in protruding sponsons. They fired a 54.2-kilogram (119 lb) APC shell (200 in storage for each). At +15° max elevation and 800 m/s (2,600 ft/s) they reached 9,000 metres (9,800 yd). They fired at 2–3 rounds per minute.

8× 100 mm/45 (3.9 in) Canet guns

The eight Canon de 100 mm (3.9 in) Modèle 1893 guns completed this in unprotected mounts on the shelter deck, firing each a 14-kilogram (31 lb) shell (240 in reserve) at 740 m/s (2,400 ft/s) on an elevation to 20° and 9,500 metres (10,400 yd) range, plus maximum rate of fire of six rounds per minute, three sustained.

20× 47 mm/40 (1.9 in) Hotchkiss guns

For close defence, she also carried twenty Canon de 47 mm (1.9 in) Modèle 1885 Hotchkiss. They were mounted on both military masts (eight) and the remainder in embrasures in the hull or superstructure, an arrangemebt that was criticized by Rear-Admiral (Contre-amiral) René Marquis, complaining in the 1903 report for slow hoists and lack of ready-use rounds. Also no fire-control system was designed for them in night operations. They fired a 1.49-kilogram (3.3 lb) shell (15,000 in store total) at 610 m/s (2,000 ft/s) to 4,000 metres (4,400 yd) and 15 rpm, 7 rpm sustained.

4× 450 mm (17.7 in) torpedo tubes

These two torpedo tubes per broadside, with for one, submerged at 60° angle, the other, above water, on mounts to traverse 80°. She had in store 12 Modèle 1889 torpedoes, four being training duds.

Iéna Specifications |

|

| Dimensions | 122.31 x 20.81 x 8.45 m (401 ft x 68 ft x 28 ft) |

| Displacement | 11,688 t, 12,105 tons FL |

| Crew | 701 wartime |

| Propulsion | 3 TE steam engines, 20 Belleville boilers for 16,500 ihp (12,100 kW) |

| Speed | 18 kn (33 km/h; 21 mph) |

| Range | 4,400 nmi (8,100 km, 5,100 mi) at 10.3 kts |

| Armament | 4× 305 mm/45, 8× 164mm/45, 8× 100mm/40, 12× 47mm, 4× 450 mm (17.7 in) TTs |

| Armor | Belt: 224-320, Deck 2.6 in, Barbettes: 250 mm, Turrets: 290, CT: 298mm |

Iéna in service until her demise 1901-1907

Early service

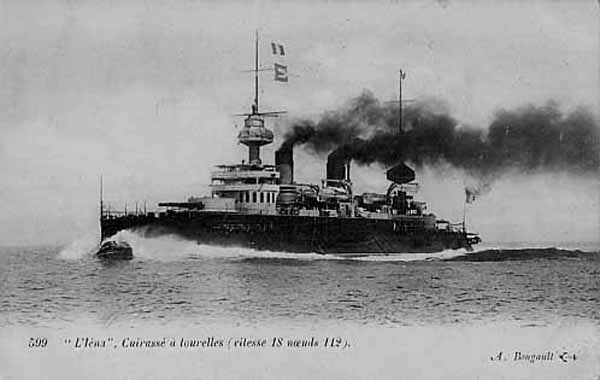

Iéna was launched in Brest on 1st September 1898, completed only by 14 April 1902 at a cost of F25.58 million. She departed for Toulon right away. En route, she cemented a reputation, having a sailor overboard and any issues with her rudder. She arrived on 25 April and became became Rear Admiral Marquis’ flagship for the Second Division, Mediterranean Squadron from the start of May. Drydocked on 14–31 May to deal with her troyblesome rudder, she started a serie of goodwill visits, notably in French North Africa.

In January 1903 she was in refitting and later departed for the coast of Spain. She stoipped in Cartagena in June, being visited by King Alfonso XIII. After a refit 20 August-10 September she departed with the Mediterranean Squadron for a visit on the Balearic Islands. Again, while back, two crewmen died while training with the manual steering gear, in heavy seas. They were caught and crushed to death by the machinery. RADM Marquis was relieved of command by Rear-Admiral Léon Barnaud on 3 November and replaced. Iéna trained in home waters untim 17 December.

Iena, Bougault coll.

April–May 1904 saw her particopating in fleet exercizes followed by a review on the Bay of Naples, and at this occasion was visited by both the president Émile Loubet, and King Victor Emmanuel III. Next she departed for the Levant, visiting Beirut, Suda Bay, Smyrna, Mytilene, Salonika and Piraeus.

In 1905 she had another yearly refit on 15–25 April and took part in the “summer cruise” on 10 May-24 June followed by annual fleet manoeuvres on 3 July–1 August. Barnaud was replaced by RADM Henri-Louis Manceron on 16 November and on 12–17 April 1906, she was sent for a relief mission to a devastated Naples after the eruption of Mount Vesuvius. In July she took part in the combined fleet manoeuvres for the first time with the Northern Squadron. On 4 August, she was in refit. She took part in an international naval review in Marseilles (16 September) but while off Toulon she collided with, and sank Torpedo Boat No. 96.

Explosion and investigation

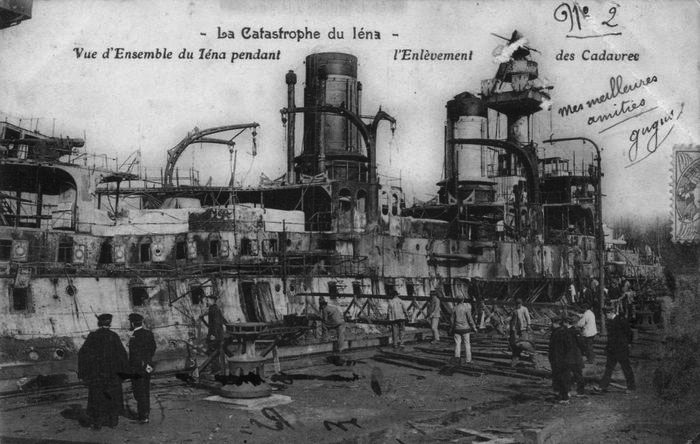

On 4 March 1907, Iéna was in Dry dock No. 2, Missiessy Basin, Toulon for her drydock hull maintenance, as well as a thorough inspection of her leaking rudder shaft. After just eight days at 13:35 a first explosion started near the aft 100 mm magazines. It spread and was followed by many others until around 14:40, completely devastating the battleship and spreading fire, debris and desolation in Toulon. At some point the blast was enough to blast clean off three nearby workshop’s roofs, while the ship was completed “cleaned off” from the aft funnel to the aft turret.

The main issue with a fire that coould have been contained, was her situation: In dry dock the magazine could not be flooded or water pumped out to extinguish the fire. Indeed, to save time, ammunition at that point was still abor, not unloaded before docking. On the bridge of the nearby moored battleship Patrie, the captain followed the first explosions and ordered right away to fire a shell into the dry dock gates. The idea was of course to flood it. But the gates were heavy and the shell simply ricocheted.

In the end, a local crew of workers led by an officer managed to have them manually opened, but in the meantile, some 118 crewmen and dockyard workers were killed plus 2 civilians nearby at Pont-Las by fallouts. The explisions were heard all around Toulon and the surroun ding countryside, more than 20 km away. This left the city in a state of shock and atonement.

On 17 March, the President of France, Armand Fallières, and Georges Clemenceau, the President of the Council of Ministers came and attended the following funeral, with a national day of mourning declared, a commemorative monument built in Lagoubran cemetery. For once, both the Senate and the Chamber of Deputies created their own commissions for a large inquiry, led respectively by Ernest Monis and Henri Michel.

Hearings followed reports of the wreck by scientists, and soon the most likely cause was atrtibuted to the fire start in the 100 mm magazine. Tests in laboratories shown the most likely explosion cause was due to decomposing Poudre B, a nitrocellulose-based propellant. It was noted are unstable when getting old, to the point it could self-ignite. This was contradicted by an April 1907 controversial report about the explision of a torpedo directly below the magazine, its warhead “cooking up”, as the further origin.

This hypothesis came from the yellow-coloured smoke which emitted, as reported by eye-witnesses before the first explosion. Navy Minister Gaston Thomson ordered on 31 March a replica magazine to be built and black-powder magazine nearby, however it failed to produce results on 6–7 August as the propellant used was more recent. President Fallières’s own appointed technical commission on 6 August was led by the world-famous mathematician Henri Poincaré, but also academic celebrities such as the chemist Albin Haller and even the inventor of “Poudre B”, Paul Vieille.

Meanwhile, the navy’s Propellant Branch not to be undone, tried to fend off criticisms by stating these were able to resist 43 °C (110 °F) for 12 hours. But they could not determine exact behaviour for old decomposing Poudre B in magazines with natural ventilation. The Senate Commission published its report on 9 July. The blamed fell on those implicated in the procurement and storage of Poudre B. It was debated on 21–26 November while the deputy assembly Commission followed on 7 November 1908 was more indecisive, stated by the presse as “a model of vagueness and imprecision”. There were clearly accusations of gross negligence abnd some business interests by some deputies which ended in a scandal and PM Thomson forced to resign.

Stern after explosions, showing her stille considerable tumblehome.

These explosions gutted the ship between Frames 74 down to the lower armour belt level and all the machinery destroyed. A Navy commission estimated the repair cost to around seven million francs on two years but the general advice by then was that she was now obsolete and not worth it. Indeed, since then a lot of changes intervened for the construction of a serie of larger, more modern Patrie and Republique class. Like Suffren, she was of another era.

The navy decided to have her decommissioned, used as a target ship with at least a recent protection scheme. Stricken on 18 March, she was disarmed keeping only her main gun turrets to be fired at, in 1908. Eventually she was made seawothy enough to be towed at sea for 700,000 francs, moored off Porquerolles Islands. The idea was to test the effectiveness of Melinite-filled armour-piercing shells. The Navy started its first live fire test on 9 August 1909 by the armoured cruiser Condé‘s 164.7 mm and 194 mm (7.6 in) shells from 6,000 metres (6,600 yd).

Results were inspected up close and photographed, even including a crew of wooden dummies and live animals. By 2 December after all these tests, Iéna was close to sinking after a new inspection and the navy decided to have her towed to deeper water and sunk for good, but as the towing began she suddenly capsized and sank. Her wreck was sold on 21 December 1912 for 33,005 francs, BU and salvaged until 1927, with the very last parts removed in 1957.

Sources/Read More

On histogen.dol.free.fr

On Calenda

On histoire-genealogie.com

On battleships-cruisers.co.uk

L’illustratrion, on Iéna

navypedia

Campbell, N.J.M. (1979). “France”. Gardiner, Robert Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships 1860–1905.

Caresse, Philippe (2007). “The Iéna Disaster, 1907”. In Jordan, John (ed.). Warship 2007. Conway.

Friedman, Norman (2011). Naval Weapons of World War One: Guns, Torpedoes, Mines and ASW Weapons of All Nations

Gille, Eric (1999). Cent ans de cuirassés français. Marines édition.

Jordan, John & Caresse, Philippe (2017). French Battleships of World War One. Naval Institute Press.

Silverstone, Paul H. (1984). Directory of the World’s Capital Ships. Hippocrene Books.

Caresse, Philippe (2018). “The Battleship Iéna” in “The World of the Battleship” Seaforth Publishing.

Schwerer, Antoine (1912), Investigation Report on the Powders of the Navy to the Minister, Paris

Le Petit Journal supplément illustré 31 March 1907, 21 April 1907

L’Illustration n°3342 (16 March 1907) and 3343 (23 March 1907)

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign