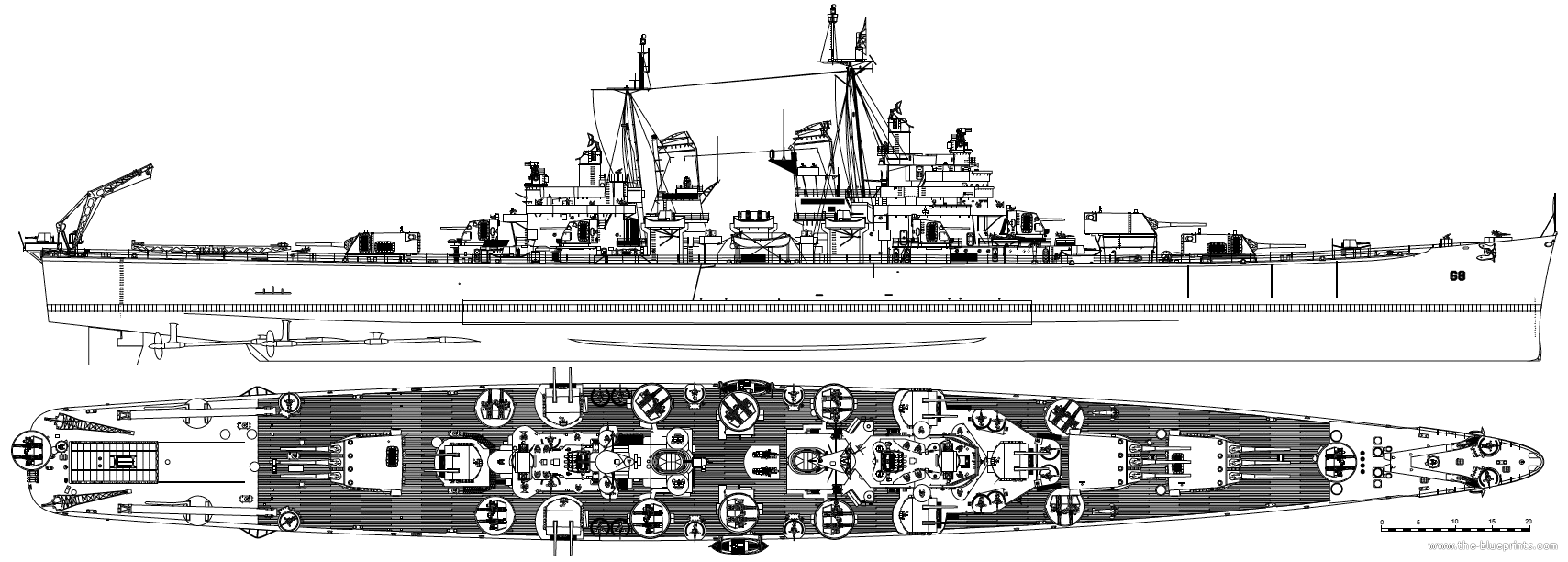

Baltimore class (1942)

USS Baltimore, Boston, Camberra, Quincy, Pittsburgh, St. Paul, Columbus, Chicago, Bremerton, Fall River, Los Angeles, Macon.

The standard USN heavy cruisers (1942-46)

The Baltimore class cruisers were splendid battle wagons that arrived too late in the pacific to make a difference. Better than the Clevelands on all accounts, they were however also not last, largest of best conventional heavy cruisers ever built: That distinction belongs to the Des Moines class. The Baltimores just resumed studies started with the USS Wichita but pushed their advantage with the treaty’s end while paying attention to detail in many areas. Further refinements due to delays would led to the improved Oregon City class (which will be treated in a standalone post as well as the guided missile conversion, Boston and Albany).

Context of the design

From September 1939 indeed, the war made obsolete the Washington treaty and with it, the ban on 8-in guns cruisers enforced since the London treaty in 1930. The USN was now free to launch replacement studies for its rather mediocre Pensacola class and following “tin-clad” Northamptons. The just completed USS Wichita was seen an excellent basis for work, albeit with the goal of radically improving her poor stability. The beam increase was to be at first limited to just 0.6 m (1.9 feet), however due to the radical AA increase planned along the way, it was decided to make more significant changes in 1940. Having low priority compared to the Clevelands, however their completion was delayed to mid-1943 which proved their undoing career-wise.

Due to a deficit in capital ships causes by treaties, the US Navy used their heavy cruisers as main surface units, and it was shown in particular in the fierce battles around Guadalcanal in 1942. These six-month saw them suffering heavily, with 11 engaged and all sunk or damaged. From 1943, surviving ones and new heavy cruisers were limited to shore bombardment (where their slow firing guns were well suited) and task forces antiaircraft screening, enabled by their larger hulls and reinforced AA armament.

Given their speed, modern radar and better AA, they ended as always assigned to carrier screening and rarely, if never have the opportunity of surface combat. For example, a single Baltimore-class which saw action in the Atlantic only conducted shore bombardment, never fought any German ship. Peacetime limitations away, at full load a Baltimore reached 17,000 tons. This was quite considerable and placed them at the head of allied cruisers.

A winning formula ?

The Baltimore class was to have 24 units planned, but 6 were canceled on August 12, 1945. The remaining 18 were admitted in service, but after WW2 for six of them. Those who had time to “participate” were twelve: The USS Baltimore, Boston, Camberra, Quincy, Pittsburgh, St. Paul, Columbus, Chicago, Bremerton, Fall River, Los Angeles and Macon. They were launched in 1942-44 and completed in 1943-45.

Their main features, apart from their huge hull, were their three main triple turrets arrangement as for the Wichita, and a powerful secondary dual artillery made of the excellent standard 5-in/38 plus the new standard 40/20 mm AA. War lessons pleaded for a concentration of guns and fire arc around a central redoubt so that each ship could set up a veritable impassable “wall of steel” to Kamikazes in 1945. As a result, just one suffered aerial torpedo damage in combat.

A simple comparison makes it possible to get an idea: USS Wichita when she entered service in February 1939, had eight 5-in guns in single mounts, plus eight cal.50 HMGs. With the Baltimore, initially planned quadruple 28mm “Chicago pianos” were replaced by more than forty four 40mm/56mm Bofors while the new 5-in/38 were now in twin turrets. Like on the Clevelands, they were arranged in a diamond-shape scheme. Engineers also chosen to lenghten the waterline armored belt (and thus the citadel). As a result standard displacement rose to 13,600t, with a taller hull for increased seaworthiness and stability, and as it happened also, better top speed.

War lessons about the arc of fire, like on the Cleveland class, culminated in the sub-class Oregon City, launched as her two sister-ships Albany and Rochester in 1945, completed in 1946, and only soldiering in the Korean War. Them and the Baltimore formed the backbone of the US conventional fleet until 1970. Many served as fire support and command ships in Vietnam, including five as missile cruisers. USS Chicago and the USS Albany were still in service in 1980. They traded Kamikaze for Migs, collectioning awards.

Genesis of the Baltimore class cruisers

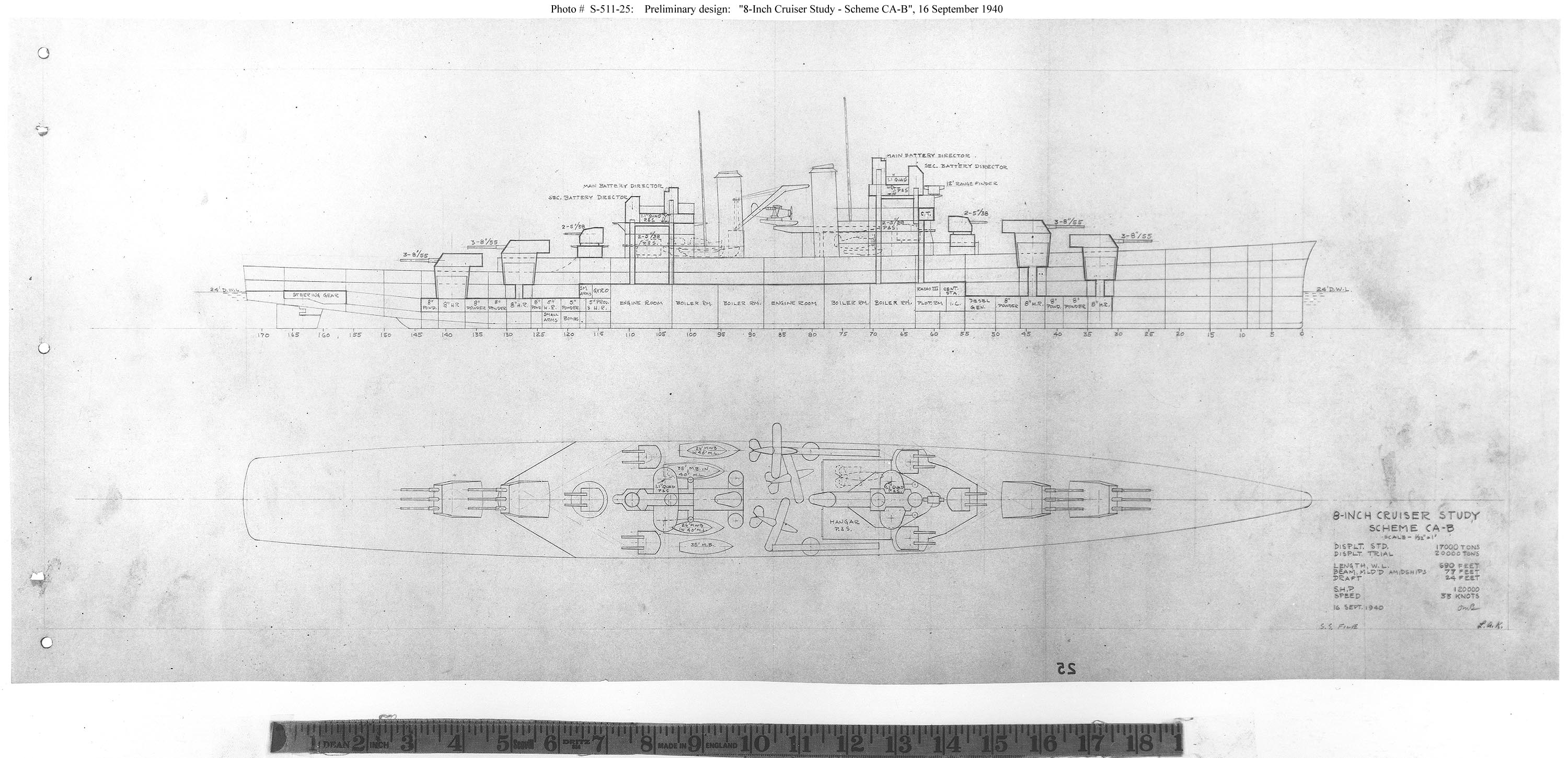

8-in cruiser design study, Scheme CA-B, 16 Septemmber 1940. Note the hangars were located at the center. It would have been a very large design, perhaps in excess of 20,000 tonnes fully loaded, still with firing arcs limitations and no substantial increased in AA.

Immediately after the the start of the war in September 1939, the US Navy started post-treaty studies, having both being freed from global topnnage limits for cruisers and technical unit tonnage and limitations as well. However with the span of such short time, the general staff could not completely rethink it’s cruiser doctrine. To gain time, it was easier to start from a known base and improve on it: The Cleveland were for example a development of the Brooklyn class and retook the hull and machinery, just working around an improvement of AA and other configurations.

Meanwhile, studies regarding a new class of heavy cruiser started a bit later, but on the same way, on the basis on USS Wichita, last known heavy cruiser designed from 1937, which represented a transition already from inter-war 1st gen (from Pensacola to New Orleans), to World War II designs. It too, borrowed on the Brooklyn class (notably and the hull) and thus, also the Cleveland class, studied earlier than the heavy cruisers in 1940. In profile, they would draw strong parrallels with the Cleveland-class light cruisers albeit with a long hull and more centralized superstructures due to the larger and heavier 8-inch (203 mm) turrets. This gave their bridges fore and aft of the two funnels their more towering apperance.

Design Evolution

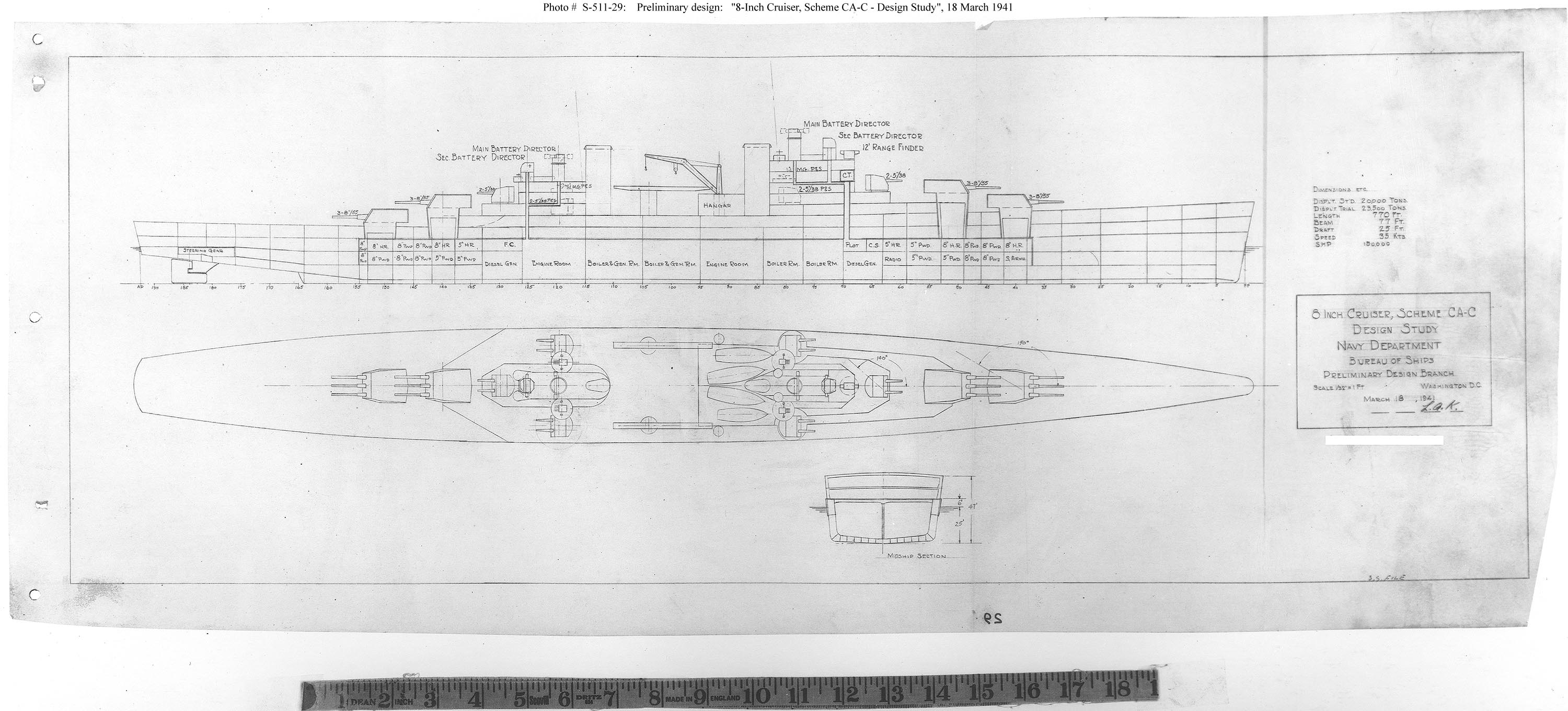

S-511-29, quad turret 8-in design, scheme CA-C dated 18 March 1941, never adopted;

In general, the US Navy considered Wichita to be successful, but the 10,000-ton limit still made for a cramped design which would exhibit later crippling stability problems when upgrading AA and radars. This would be also a huge issue for the Cleveland class. Nevertheless, it was successful enough to be used as the template for three classes of heavy cruisers: The Baltimore, Oregon City and Des Moines classes. The obvious primary reason for their development was to get a main battery of 8in guns at sea, being heavier and long range guns intended for surface engagements with IJN cruisers.

The US Navy however had a love–hate relationship with the 8in gun. Treaty cruisers had those only due to treaty restrictions, but the USN would have preferred longer range and greater penetrative power against armored targets. They were still better in that regards compared to the existing 6in gun which only saving grace was speed. With time and refinements in its mounts, it even took a dual purpose role. Leaving the USN without a proper surface battle main ordnance, but the 8-in gun.

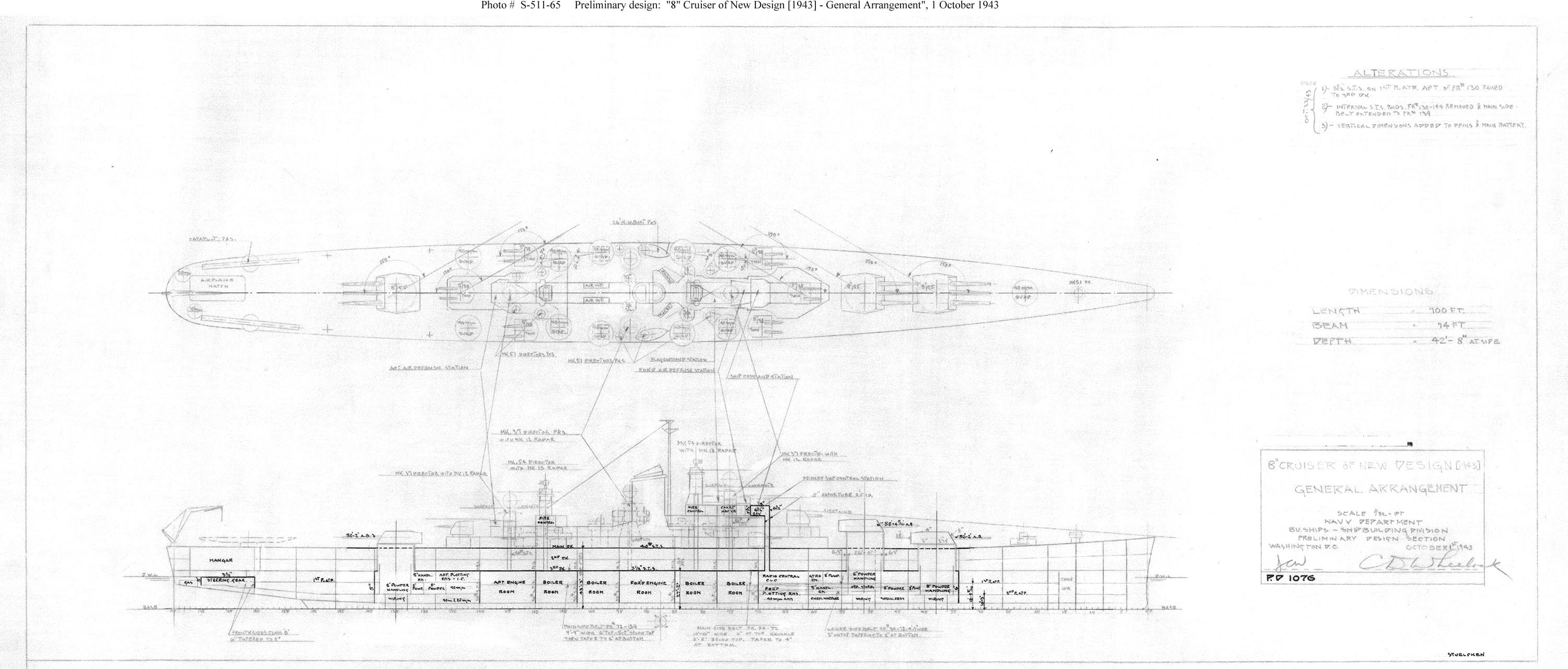

Design evolution, S-511-65 “new design” dated 1st October 1943.

They were concerns about the performance of the 8in gun as shown in gunnery trials and experience showed it was too slow, and as it was believed, potentially than the IJN cruiser’s own 8-in guns. The main reason behind was the use of separate propellant charges, which made for a longer reload cycle. Rate of fire was also lowered as to regain its loading angle and back. In the best conditions and skilled crews, it was hoped for a rate of fire of 3-4 rounds per minute, too slow to engage fast-moving cruisers and destroyers, even using radar. That was the main reason the Cleveland class was started earlier. It left more time thin,king about solutions to make the 8-in more efficient.

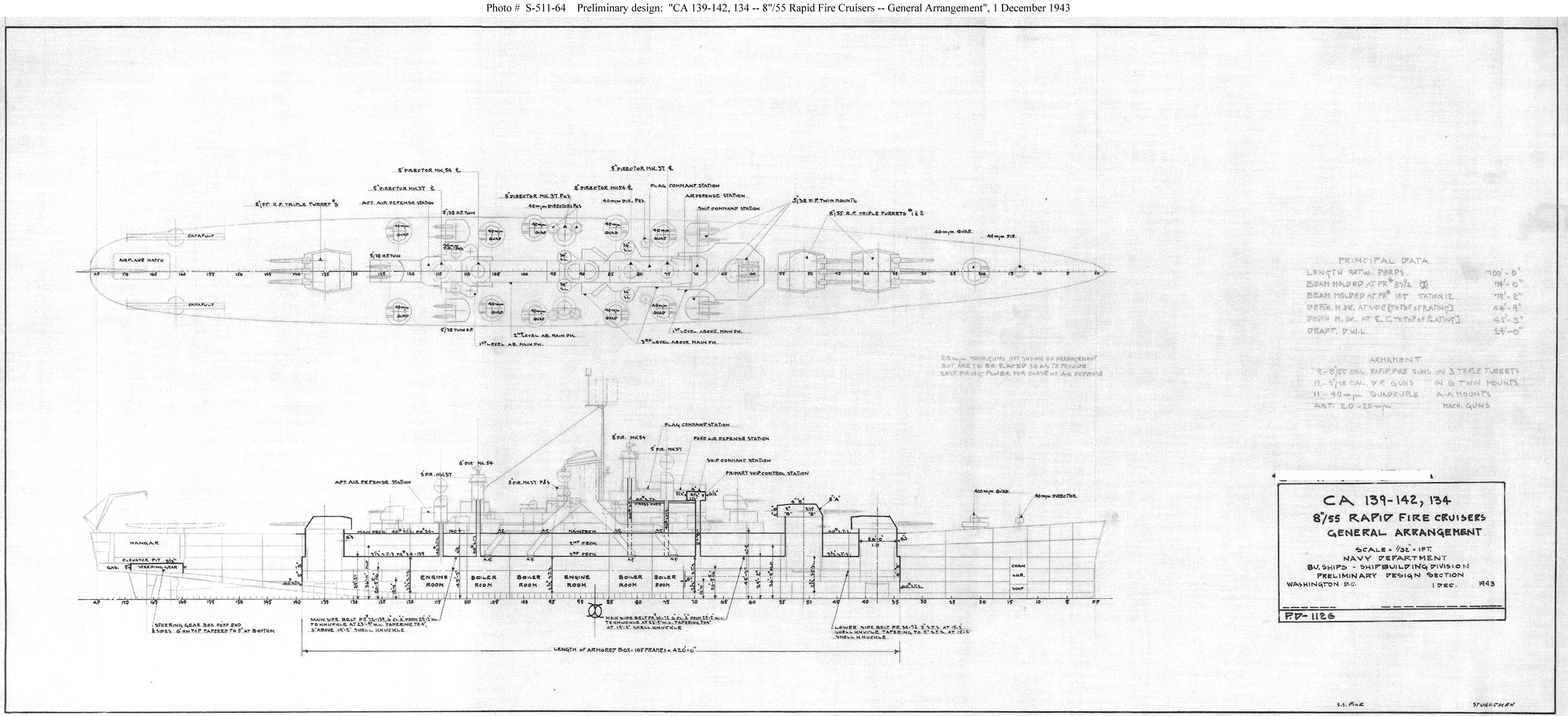

Last evolution of the alternative design (Oregon City class) in December 1943. S 511-64 ended planned for the CA-139-142 with the new 8 inches/55 rapid fire model asked by the admiralty for well before WW2. This became the Des Moines class.

Construction

Construction of the first four Baltimore class heavy cruisers started on July 1, 1940. The US were not even at war. In doubt, also given the tension growing in the far east, four more were ordered in December. The second main order was part of the war emergency mobilization plan for 16 more ships, approved on August 7, 1942. The heavy cruisers bore the brunt of the Pacific campaign and in 14 months more than half were lost in action, but despite of this, completion was delayed.

Indeed, the lighter, simpler Cleveland-class that could be completed more quickly and their fast carrier derivative (the Independence) were prioritized for the carrier groups. The first eight Baltimore-class construction proceeded at such as pace that the US Navy had extra time to improve on the design. This modified design when it came out however was delayed for the next six ships, for 14 total using the original design. Only three, before cancellation, were converted and became the Oregon City class.

Thus in grand total, 17 Baltimore and Oregon City classes entered service while the 18th to be called USS Northampton was suspended and later completed as a command ship in 1950. Five more laid down were cancelled and scrapped, one ordered but not started also when came the 1945 cancellation. Of the first serie, CA-68-75, eight cruisers were built at Bethlehem Steel Corporation, Fore River Shipyard. The CA-130-133 (four) were built at New York Shipbuilding Corporation, Camden, New Jersey and the last two, CA-135-136, at Philadelphya NyD.

Following previous practices, they were all named after larger cities, but USS Canberra, to honor the memory of HMAS Canberra sunk at Savo Island Battle and related to the Australian capital. This gesture was a sensible one to better conciliate the Australians during the Pacific Campaign. All receive didentificaitons linked to “CA” which was the old one for “armored cruiser”, kept for heavy cruisers as they were their inheritors, although much less well protected than armoured cruisers, protection was better thought of, and probably the pinnacle of cruiser armour development at this point. Cold War cruisers were a considerable downgrade on this scheme.

Final design features

Hull and general construction

On paper, they were much larger than the Clevelands, and less “spread out” in large part due to the heavier citadel, thus more compact, and larger barbettes and turrets to be protected inside. The two raked funnels and masts were kept though, but due to the location of the secondary 3-in/35 twin turrets, it was even more cramped and compact than for the Cvelelands; A larger hull and better weight management produced a better metacentric height, this the stability authorized the addition of an extra deck on the bridge, giving these cruisers a more intimidating, commanding presence.

The Baltimore-class cruisers had enlarged turrets compared to USS Wichita, 673 feet 7 inches (205.31 m) long overall, with 70 feet 10 inches (21.59 m) in beam for a 23 feet 11 inches (7.29 m) draft as designed. This was unchanged for the next Albany and Boston sub-classes alterations going in all other categories. Fully loaded they reached 17,031 long tons (17,304 t) as designed. The hull was well flared forward with fine lines and a raised bow towering above the waves for 33 feet (10 m), making them able to deal with heavy weather while being far less “wet” than the lower and overloaded Clevelands. The stern was 25 feet (7.6 m) above the waterlne at normal load, and funnels were 86 feet (26 m) high, the foremast towering at 112 feet (34 m) above the deck.

The superstructure filled 1/3 of the overall deck lenght, less than the Cleveland’s ratio as said above, with two deckhouses in which the funnels were joint, the space in between generally occupied by a few utility boats. The masts were placed either side of the funnels and although of the pole and not tripod type, strongly built and also raked, accommodated electronics platforms. They proved so strong that there was no need for modifications even after 1950s electronics upgrades.

Armour Protection

Protection, in comparison with Wichita, practically has not changed: Only deck thickness was increased to 65mm while the waterline belt became longer.

-The immune zone under fire of 8 inch guns was stretched also.

-The vertical belt armor was 6 inches (152 mm) thick.

-Horizontal deck armor was up to 3 inches (76.2 mm) thick.

-Turrets were also heavily armored, between 1.5–8 in (38–203 mm) thick.

-The conning tower had walls 6.5 inches (165 mm) thick.

Powerplant and performances

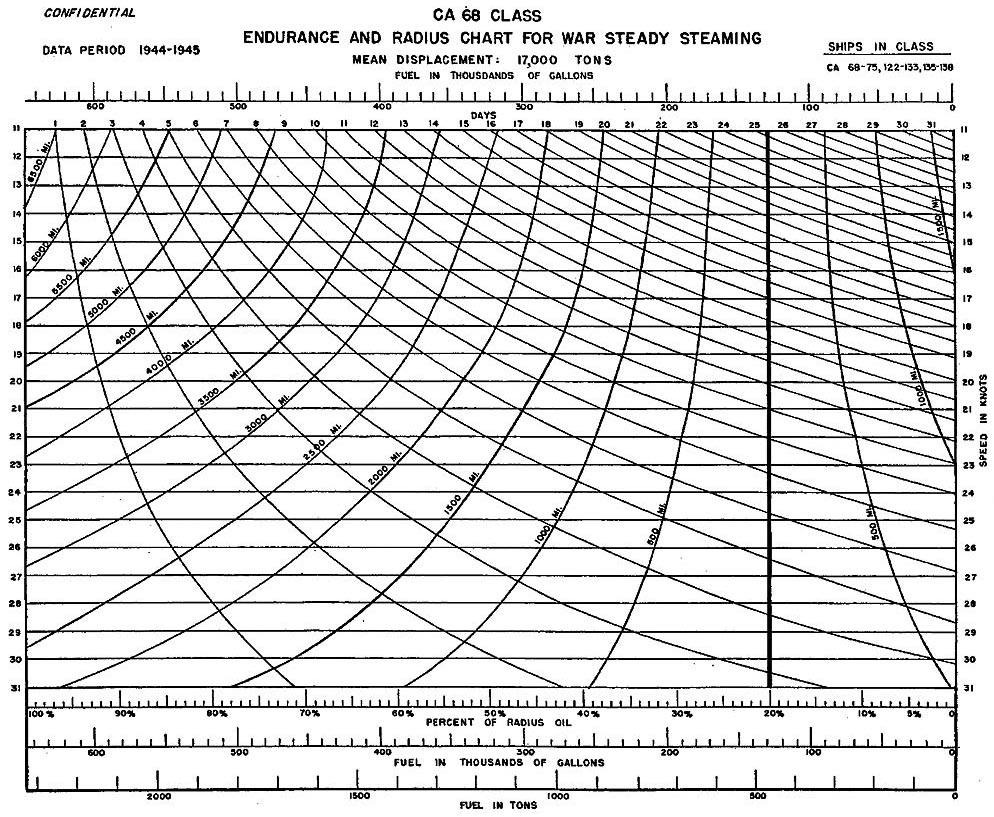

Baltimore class endurance full chart

Even at 17,000 tonnes, the Baltimore class needed more power than the Cleveland class. The powerplant consisted of 4 screw propellers connected to four shafts, driven by four steam turbine sets, fed in turn by “only” four Babcock & Wilcox boilers for a grand total of 120,000 shp (89,000 kW). This was 20,000 more than the Cleveland class, and due to their fine lines (even finer since the latter were older), the larger Baltimore were also faster, at 33 knots (61 km/h; 38 mph) versus 32.5 knots (60.2 km/h; 37.4 mph).

If this was remarkable, their larger hull enabled more fuel capacity and indeed they carried up to 2,250 long tons (2,290 t) of fuel, translated for a cruising speed of 15 knots (28 km/h) to 10,000 nautical miles (19,000 km). After missile conversion this fell for the Boston and Albany classes to 9000 and 7,000 miles respectively despite their greater fuel capacity of 2600 and 2500 tons. This was still better than the 8,640 nmi (16,000 km; 9,940 mi) of the Clevelands in their original configurarion.

They were far more stable, still bled speed in high turns but were found responsive at the helm. Their longer hull was better suited to follow wavelenghts in heavy weather, making them good “clipper” rather than “riders”. Their bow was higher as their freeboard so they were far less “wet”. Only poor welding caused bow damage in a storm, but the Clevelands were far more damaged. This combination made them better platforms for conversion overall, explaining in part the Navy was ready to spent billions and five to six years in drydock to have them converted.

Armament

There was nothing revolutionary about it, as it retook essentially the Wichita’s formula, an improved recipe already activated on the older Northampton class, and repeated on the Portland and New Orleans. Of course since the design was prefected during construction, the largest difference was a massive AA increase, and full reliance on the 40 mm Bofors.

CA68 to 71 were designed with three triple 8-in 55 caliber (203mm/55) Mk 12 main guns (two superfiring forwards, one deck aft), six twin 5-in/38 (127mm/38) Mk 12 dual purpose (in a diamond shape) and for light AA, no less than twelve quad 40mm/56 Mk 1/2 and twenty-four single 20mm/70 Mk 4. Note at the time, that the 40 mm were far more numerous than the 20 mm guns, as their lethality in 1943 was already well proven. 20 mm Oerlikons were even gradually retired in 1945. In 1940 hopwever, quad cal.05 Browning and 28mm 1.1-in “Chicago Piano” quad AA were planned, buy cancelled as time passed for the new standards.

In 1945, twelve 5-in, forty eight 40 mm, and twenty-eight 20 mm in 1945 was still impressive, more than the Cleveland classes, only beaten by the very large Alaska class. Another peculiarity of these ships was the adoption of a better distributed protection, and new shells for their 8-in guns. These much heavier shells shone in parabolic trajectory, being able to pierce the thickest Japanese heavy cruisers armor known. Unfortunately, encounteres with IJN surface ships became increasingly rare. Engagements were surface units were the exception. Their main guns were mostly used for coastal shelling, while their AA constibuted to down perhaps a hundred of planes combined, watching over aircraft carriers.

3×3 8-in/55 Mk12/Mk15

USS Toledo firing her forward guns in 1959

These were similar to the earlier Mark 14 of USS Wichita, but of much lighter construction. Two distinct mountings existed, the the triple mounting of the Tuscaloosa (CA-37) New Orleans sub-class had lighter guns easing revolving time. USS Wichita (CA-45) benefited from a new mounting type which also wetn on the Baltimore class and Oregon City class as well, as their guns were individually sleeved; mounted further apart. Yjos increased individual protection as well as allowing for better shell dispersion. The shell-handling equipment was also modified also to handle the new “super-heavy” 335 lbs. (152 kg) AP shells, as compared to the 260 lbs. (118 kg) AP of all previous classes, including Wichita. The USN admiralty at last had it’s perfect heavy cruiser gun. It should be noted that the New orleans, Tuscaloosa, Minneapolis, Wichita, but also the Baltimore class were all upgraded to the Mark 15 in 1944-45.

-The Mark 12 had an autofretted A tube with a shrunk on jacket and a screw box liner, and used a down-swinging Welin breech block.

-The Mark 15 had a smaller chamber and improved rifling twist while both were finished with chromium-plated bores.

As for ammunitions they fired the AP Mark 21 Mods 1 to 5 (super heavy) 335 lbs, the older 260 lbs AP Mark 19 Mods 1-6, the SP Common Mark 17 (same), HC Mark 24 (same) and Mark 25. Charges varied from the full Charge of 85 lbs. (38.6 kg) SPD to Full Flashless Charge of 89 lbs. (40.4 kg) SPCG, and the 55 lbs Reduced Charge or it’s 56 lbs flahsless equivalent. Muzzle velocity varied between 2700 fps/823 mps for older shells to about 4,000 fps (1,200 mps) for the LLRB. For their nine guns, each Baltimore class carried about 1,350 main caliber shells of all types.

General characteristics

USS St Paul gunnery support in South Vietnam, October 1966

- Gun car: 17.17 tons, 449 in (11.405 m) long

- Barrel: 64 grooves, Uniform RH 1 in 35 or 25 (Mk12/15)

- Chamber vol. 4,860 in3 (79.6 dm3)

- Rate Of Fire: 3-4 rounds per minute

- Muzzle Velocity (AP Mark 21): 2,500 fps (762 mps)

- Working barrel pressure: 18.2 tons/in2 (2,870 kg/cm2)

- Approximate Barrel Life: 715 rounds

- Avg. Individual storage: 150 shells.

- Turret weight: 303 tons (307.7 mt)

- Elevation 10.6°/second, Traverse 5.3°/second

- Gun recoil 32 in (81 cm)

- Loading angle +9 degrees

- AP shell range at 41.0°: 30,050 yards (27,480 m) with 54.7° fall final angle, flight 77.8 seconds.

- Belt penetration at 10,800 yards (9,880 m)/10 in to 4 in at 28,600 yards (26,150 m)

Turrets

Performances

6×2 3-in/38 Mk12

The trusted dual-purpose twin turret was one of the best such system ever developed in WW2. Its rate of fire and accuracy was unmatched. Like for the Clevelands, these were located in six positions around the main superstrcture: One forward superfiring over “B” turret, one aft superfiring over “C” turret, and four on the sides, creating two “triangles” fore and aft with the best possible arc of fire. For performances, see the Cleveland class. Only notable was the upgrade from the Mk12 to the Mk 32. See the full specs here.

40 mm/45 M1/2 AA

The standard medium-light AA guns in service from 1941 to 1945 and well beyond. Derived from the Swedish Bofors, it was improved and mass-produced as the Mark 1/2. The great allied AA gun standard. With the quad mount, proper to the USN, the reunion in fact of two twin mounts, the Baltimore class received either deck or raised mounts along the superstructure amidship: Two deck after the 5(in/38, two up alongside the funnels, and two up in the gap between the two islands. There were two at the poop and one on deck forward for eleven total.

They were all water-cooled, in twin and quad mountings but the Mark 1 was a left-hand and Mark 2 right-hand. They were crew-intensive due to their drop-style cartridges boxes, for a theroretical 120 rpm per barrel, up to 160 firing horizontal but practical 80-90 rps and efficient up to 11,133 yards (10,180 m)/22,299 feet (6,797 m) -HE/45°. Although no longer linked to the Sweidsh firm, it was still called and popularly known as the “Bofors”.

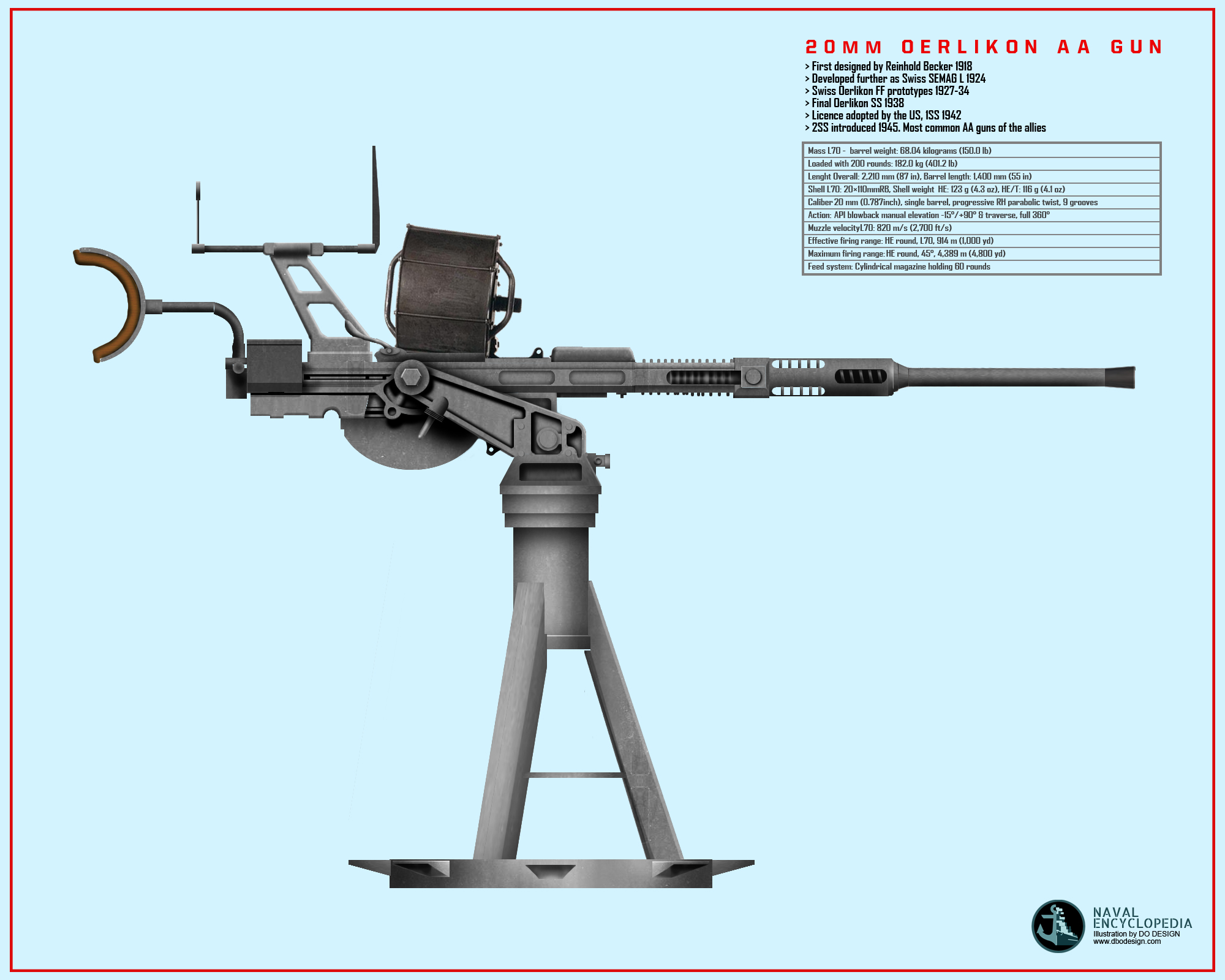

20 mm/70 Mk 4 AA

The short range standard of allied ships, derived from the Swiss Oerlikon model, itself long-derived from a cancelled WWI German gun. Liquid-cooled, shielded, it had the immense advantage of only requiring a single gun servant to operate, albeit a loader was required to reload the 60 rounds magazines, as it consumed in average 250 rounds per minute (so needed four clips). Many clips were generally stored inside the protective wall around the mount. The later war Baltimore class vessels received upgraded twin gun mounts Mark 4.

Wartime Upgrades

This armament started to change on other vessels of the class: CA72 to 75 received the new Mk 15 8-in guns, their DP artillery did not changed, but they had eleven quad 40mm/56 Mk 1/2 and two twin 40/56 ones plus two less 20mm/70 Mk 4. CA 122, 123, 124 had the Mk 15 main guns as well, and the Mk 32 dual purpose guns, Mk 2 quad and two 40mm/60 Mk 1 dual and ten twin 20mm/70 Mk 24 AA. CA-130, 131 and 132 had fourteen twin 20 mm AA guns Mk.4. CA133 still had eleven quad 40mm/60 but of the Mk 2 type and twin Mk 1, as well as the same fourteen 20mm/70 Mk 24.

Electronics and Fire Control Systems

Crewmen in the Main Battery Plot room (modernized) of USS Canberra off Vietnam, March 1967

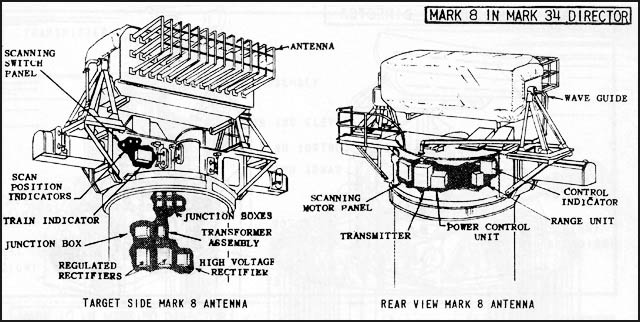

Records of exact composition varied among sources. In 1943 when the first cruisers emerged (CA68, 69, 70, 71) from completion, they had the following electronics suite, presumably the SG-1 main surveillance radar, the SK type, the Mk 8 main fire control radar, and two Mk 12/22 radars for main guns firing control.

Later CA72 and 73, but also CA130 and 136 had the more recent SG-1 radar, the SK-2, the SP radar, Mk 8 FCR and same two Mk 12/22 radars. CA74, 75, 122, 123, 124, 131, 132 and 135 had the latest 1945 SG-3 radar, the same SK-2, the new SP radar, the Mk 13 main fire control and same two 2x Mk 12/22 radars.

Mk 12/22 FCR

Thanks to their fire control radar, 8-in guns Mark 15 had amazing performances and accuracy: In 1970, USS St. Paul (CA-73), used the specially developed Long Range Bombardment Ammunition (LRBA) and fired on Viet Cong positions some 35 miles away (56 km), the best gunnery marksmanship ever achieved by a cruiser, setting an absolute, still unbeaten world record for both distance and accuracy.

Mk 8 FC/Mk 34 mount director

The standard Mark 8 microwave FC for the main battey guns was used with the gun directors Mark 34 and 38, providinh both bearing and range and allowed spotting in range and deflection of shell splashes. At 120 ft. above water the useful range was 40,000 yards down to 500 yards. Accuracy on avg. was 15 yards + 0.1% of range. Bearing accuracy was 0.1° to 2 miles.

Mk 1 FCC

The intial Mark I Fire Control Computer designed by Ford was a system linked to the Mk34 director located in the CCO (Central Comabt Operation) located well inside the ship, protected by the multiple armor layers around. This electromechanical analog computer was standard in the USN from destroyers to battleships.

Mk 8 FCC (1944)

The Mark 8 Fire Control Computer, located deep inside the fire control center in the ship’s belly, was developed by Bell Laboratories and requested by the USN Bureau of Ordnance to replace the old Ford Instruments Mark I Fire Control Computer in case manufacturing was not fast enough. But the “backup” quickly made a name for itself. The Mk 8 computer was electric, using no mechanical parts for calculation. It was far more accurate and faster to deliver a solution, but was only developed and tested in 1944 and thus was adopted in 1945.

Mk 13 FCR

The Mk13 Main Battery Fire Control radar was mounted atop the Mk8/M34 director, with a semi-cyclindrical antenna assembly. It was linked to the main battery switchboard located at one end of the plotting room inside the CCO. more on it.

Onboard Aviation

Being released later than the Clevelands, none was equipped with the initially planned Curtiss SO3C Seamew, which proved to be rather mediocre, and instead, received right away the trusted Vought OS2U Kingfisher and from early 1945 some obtained the Curtiss SC Seahawk in replacement when available. After the war, modern electronics had them condemned for good. Both for artillery spotting and reconnaissance, the power and precision of modern radars made giant leaps that aviation could no match.

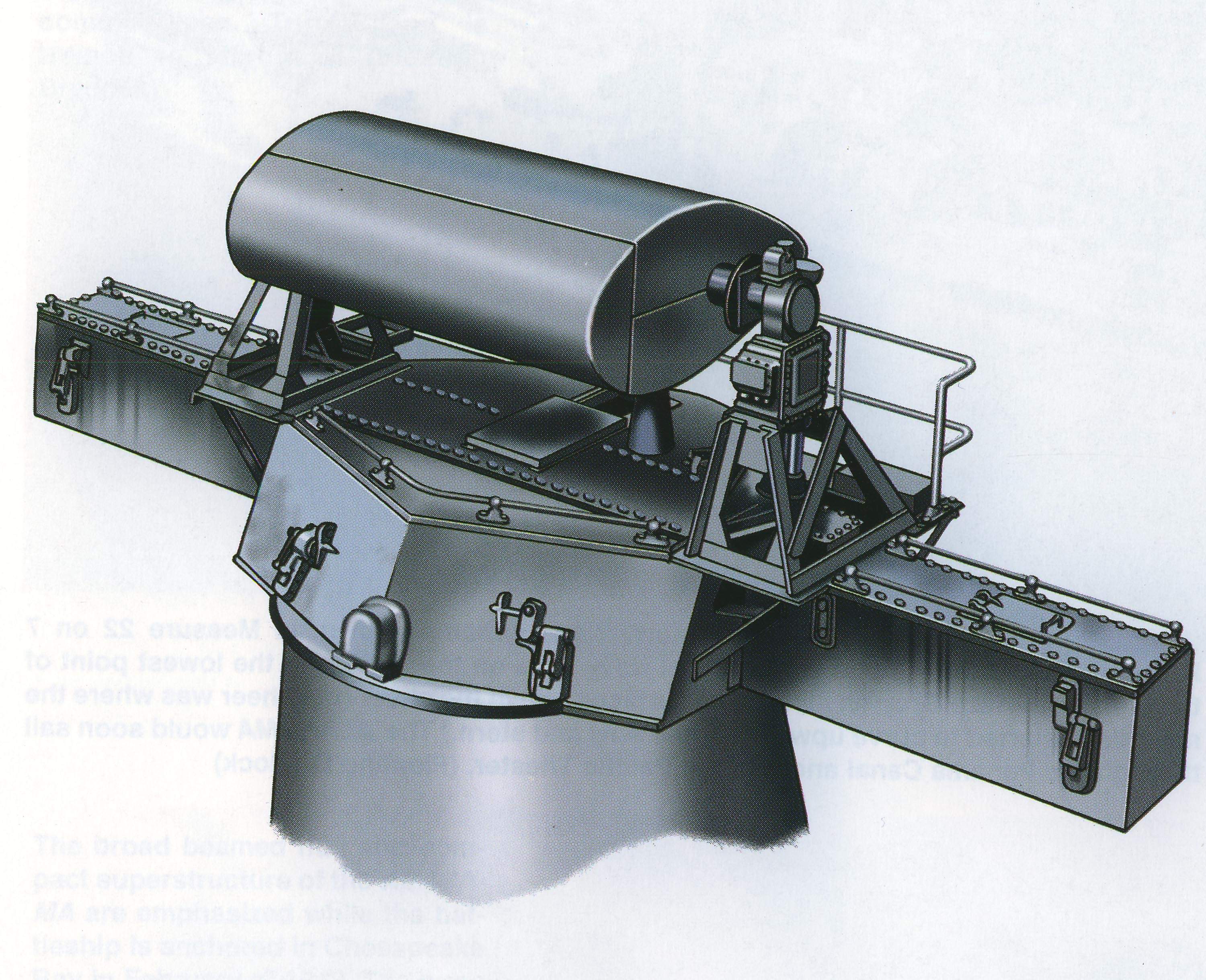

Plus the retrieval of floatplanes was always a dangerous and complicated operation whikle salty water was a maintenance nightmare. Less so for these cruisers, though, as they had a lift and internal hangar. According to navypedia, four seaplanes were carried, of the old SOC type was planned in 1940, then SO3C and eventually only the OS2U were mounted. Until CA 71 four seaplanes re carried (two on catapults, two in the hangar), but from CA 72, only two were retained.

Aircraft facilities indeed on the Baltimore class included two catapults installed on either side of the stern, which could traverse for around 130° and explosion-powered. The hangar was located below, with a sliding hatch instead of a lift, served by the two cranes at the poop. Inside there was enough space for two, not four, and wings folded, with a small workshop for maintenance which was the main intent for this space.

Profiles

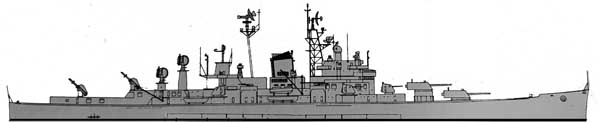

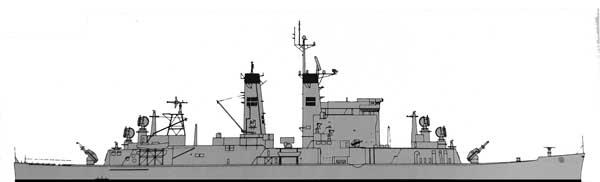

USS Boston in 1945

USS Pittsburg 1945

USS Quincy in 1944

(More to come)

USS Baltimore in 1943

uss oregon city in 1946

⚙ Balticmore class Specifications 1944 |

|

| Displacement | 14,472 t. standard -17 030 t. Full Load |

| Dimensions | 205.26 m long, 21.60 m wide, 7.32 m draft |

| Propulsion | 4 shaft GE turbines, 4 Babcock & Wilcox boilers, 120,000 hp. |

| Speed | 33 knots (CA 1 km/h; 38 mph) |

| Range | 10,000 nmi (19,000 km; 12,000 mi) at 15 knots (28 km/h; 17 mph) |

| Armament | 3×3 8 in/55, 6×2 5-in/38 DP, 48x 40mm, 24x 20 mm AA, 4 floatplanes. |

| Armor | Belt 6-in, turrets 8-in, decks 3-in, inner casemate 5-in to 6.1 in |

| Crew | 61 officers, 1,085 sailors |

A rather short and “cushy” WW2 career

USS Macon in the Mediterranean in 1953

Of the 17 (including the Oregon City sub-class) completed vessels of the baltimore class, 12 were commissioned before the Japanese capitulation but due to training and deployment time, only 7 took effectively part in Pacific campaign actions before V-Day. A single one even took part ine European/Mediterranean combat. By 1947, 9 were decommissioned, in reserve but 7 (Helena, Toledo, Macon, Columbus, Saint Paul, Rochester, and Albany) resumed service with six reactivated, 13 available for the Korean War, more seeing action there than in WW2. Of course later of those deactivated only a few returned tinto service after conversion (see below) as the Boston and Albany-class missile cruisers.

Only a few of the “pure juice” (non converted) actually took part in the Vietnam war, and by 1969, of the six commission; five were missile cruisers, only one, USS Saint Paul as a conventional cruiser for gunfire support. She was the longest in service, for 26 years, as a conventional cruiser. Of the missile ones, Chicago was the last broken up, in 1991, seeing the both end of WW2 and the end of the cold war.

Due to the context of the war when most entered service, only the first, Baltimore, Quincy, Boston and Canberra saw sigtnbificant action. In Europe and Mediterranea, in 1944, the Kriegsmarine was no longer a threat and in the Pacific, the Japanese had lost most of their assets. Designed to replace the interwar heavy cruisers, which saw heavy losses in 1942, none of the Baltimores had the occasion of using their main guns, testing their latest 8-in/55 in surface combat. Instead they spent their career between fire support on ground targets and AA defence.

USS Toledo launching a Regulus missile in 1956

Only USS Canberra was signbificantly damaged in action, struck with an air-dropped torpedo on October 13, 1944. Towed to safety by her sister USS Boston, this even saw them both missing the last major naval battle of WW2, Leyte Gulf. During the Korean War, apart an accidental fire in a turret, only sporadic coastal battery fire caused some light damage of various cruisers, such as USS Helena and Los Angeles, causing no injury. In 1968, Boston was victims of friendly fire from the US Air Force, but the AIM-7 Sparrow missiles only hit her escort, HMAS Hobart. Though when Boston was hit by a single one, its warhead failed to detonate.

So overall, their career was relatively “cushy”. Fending off Kamikaze attacks at the end of the war, they splashed perhaps 20 planes combined. More pilots were rescued either by their seaplanes in 1945, and their helicopters over Korea. Off Vietnam, however, both the Bostons and Albany shot down several migs, but that’s another story. Due to war emergency preferences, they were left over and completed too late basically to see significant action. The next wars were mostly asymetrical and despire their initial design in 1940 was made with the goold old naval battle in mind, it never happened.

If an epilogue was necessary, they Batimore were not the last heavy cruisers of the US Navy. If the Alaska class proceeded from a separate “large cruiser” type condemned to disappear as white elephants, in 1946 the conventional cruiser was still a valid concept. Missiles were a concept in the air, but it was a technological giant leap before reliability which took about ten years.

In the meantime, artillery still reigned supreme and arguably reached its zenith, between the gargantuan Des Moines class, same recipe but larger, with better guns and fire control systems, or the Worcester class, successors and ending of the light cruiser era. The three Des Moines outlived the Baltimores by decades, being striken not before 1991. They were seen rightfully so as the last of their breed, never to return, unless electomagnetic railguns triggers a renaissance.

3d Gallery

About the Saipan conversion

USS Saipan in 1955, based on a Baltimore hull.

The Saipan class were fast aircraft carriers that followed a parallel evolution to the Independence class light aircraft carrier (CVL) based on the Cleveland class hulls. The Saimapn were kjust based on the Baltimore class gulls. However unlike the first they never had full priority and were delayed until laid down in July-August 1944 and built to proper carrier specification. The hull basically as the same as the late USS Fall River, Bremerton, Macon, and Toledo, at New York Shipbuilding, Camden NJ.

They were armed with a mix of 40mm and 20mm AA guns, with no dual purpose gun. Saipan was used for jet aircraft landings and taking off from smaller decks, and had an improved radar. Completed in 1947 they fell into the post-war budget restrictions and the Navy desperatly tried to find a use for them. USS Saipan was decommissioned on 3 Oct 1957 already, converted to a command ship (CC-3) in 1963-64 and renamed USS Arlington. There was a proposal to convert them into ASW carriers but since the larger Essex class were avialable this was cancelled. Her conversion specification was modified in 1964 and she re-entered service on 27 Aug 1966 as a communications relay ship (AGMR-2) having on deck an “antenna farm” and helicopter landing area aft while the hangar was converted to communications facilities and accomodations as well as extra batteries and generators.

USS Wright was withdrawn from service on 15 Mar 1956, converted to a national emergency command ship at Puget Sound Naval Shipyard in 1962-63. Both decommissioned in 1970 and scrapped.

The Baltimore’s amazing cold war career

Baltimore class shell handling 1967

Thes massive vessels were completed late and thus, saw a limited wartime service for many. They practically saw no surface combat, but had plenty of action between coastal bombardment and AA point defence, earning battle stars, but less than the Clevelands. However post-war they had a crucial set of advantages compared to the latter: They were beamier and more stable, accepting upgrades, and generally large enough to accept more extensive modifications. That way, likle the Des Moines and Worcester class, the baltimore stayed active until the Vietnam war. They were deactivated between 1972 and 1991 (for USS Chicago/CG-11), which coincided with the disingengagement of the US in 1973, eleven keeping their full conventional capability with only radar and AA upgrades.

Missile conversions

USS Chicago underway in the coral sea 1979

Despite the fact gun-armed, conventional cruisers were not to outlive the Vietnam war, missile conversions allowed some of the baltimore to still be around until the end of the cold war, a remarkable achievement made at a hefty cost. Five cruisers were concerned, with two levels of upgrades: The more limited Boston class (USS Boston, Camberra CAG1-CAG2) and the Albany class (USS Albany, Chicago, Columbus CG-10-12). Only the first retained their partial conventional capability and were decommissioned in 1970.

Boston class conversion

The Boston sub-class was 20 inches (510 mm) draftier while displacing 500 long tons (510 t) more, notably due to their upgrades. They were only partially refitted and thus, the forward third was almost untouched. But the major cghange was the truncation of all exhausts into one thicker funnel in the gap between the two deckhouses. The guiding electronic systems required the foremast being replaced by a four-legged lattice for a larger a stronger platform. All the rear part was modified to accomodate the missile-launching system and its massive magazine, devouring the entire aft half section, replacing the turrets enirely while the AA was completely modernized and revised. A dedicated post will treat this class.

Albany class conversion

The three Albanys however were completely rebuilt from the deck up. Only the hull was left untouched. This were very impressive vessels, fitted with a massive new deckhouse taking 2/3 of the deck’s length, two decks high and it’s very tall bridge (130 feet/40 m above the water line) was a sure marker ansd recoignition point. Masts and funnels were combined into the new common “macks” (smokestacks) supporting the electronics platforms, which basically ended on tops of the funnels. The electronic suite was quite extensive as their missile suite was too. Aluminum alloy was used extensively to save weight and keep the metacentric height as low as possible but it became a fire hazard. Displacement rose “only” to 14,400 long tons standard (18,777 tons FL). They had two twin Talos SAM (52 missiles) and two twin Tartar SAM (42), ASROC and 324mm ASW TTs.

uss st. paul in 1963

uss oregon city in 1963

uss boston in 1963

uss albany in 1979

uss northampton in 1963. This last Baltimore was redesigned and converted as a command ship, which proved very useful in Vietnam.

Read More/Src

Books

K.Gardiner, Conways all the world’s fighjting ships 1922-1947.

American Cruiser of World War 2 – A pictorial encyclopedia by Steve Ewing

Cressman, Robert J. (16 December 2005). “Baltimore V (CA-68)”. Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships.

Coté, Larry; Wright, Christopher C. (December 2020). Question 15/57: Concerning the Timing of the Alterations to Baltimore (CA-68) Involving Installation of 3-in/50-cal. Guns in Place of 40-mm Guns. Warship International. LVII (4):

Links

The 8-in/55 Mk12/15 on navweaps

The 40mm Bofors on navweaps

USN Radars, fire control sets

On navypedia (archive)

uss boston ww2

On microworks.net

history.navy.mil

navsource.org

On hazegray.org

globalsecurity

uss helena on navsource

wiki

On the The Pacific War Online Encyclopedia

Videos

USS Baltimore (CA-68):Day Test Sail Fire Power

USS Pittsburg’s bow loss, dark seas

Model Kits

profile-morskie/yp-99-baltimore review on modelwarships.com

On scalemates

The Baltimore on usndazzle.com

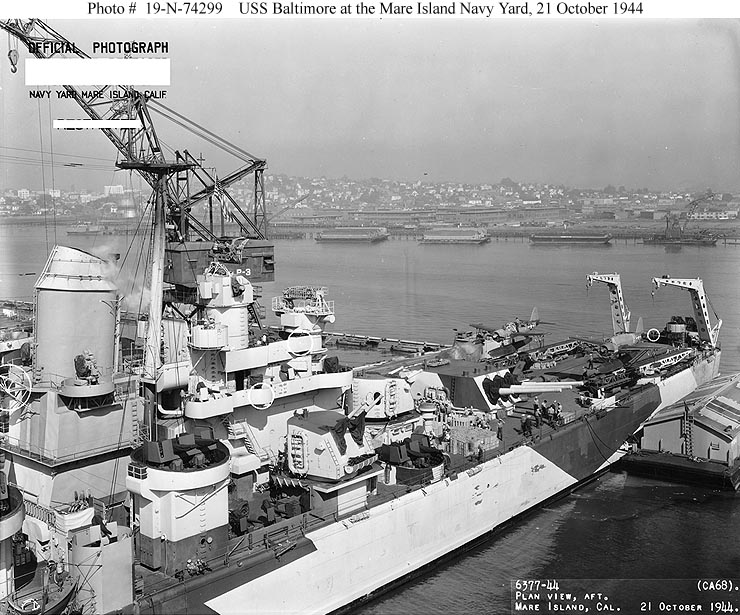

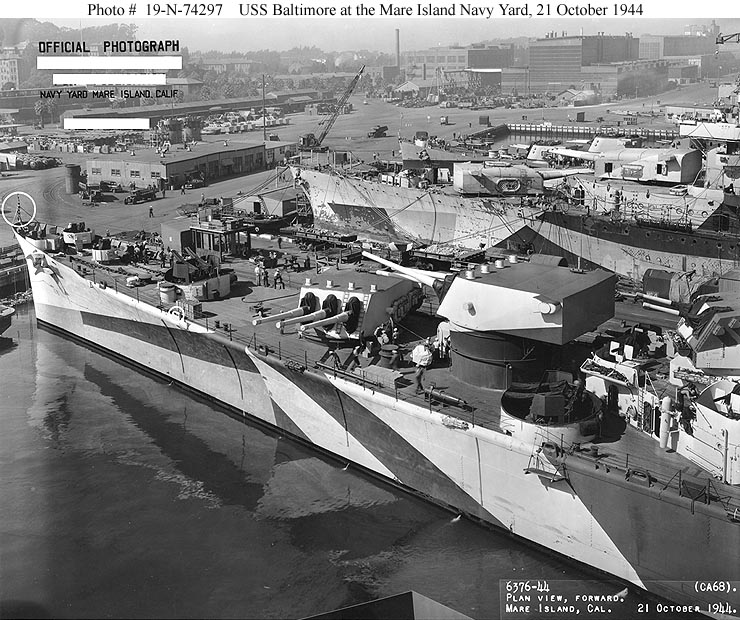

Camo ref baltimore Oct 1944 M33/16D

USS Baltimore (CA 8)

USS Baltimore (CA 8)

USS Baltimore, 18 October 1944

USS Baltimore was commissioned on 15 April 1943 and after fitting-out, she departed for Hampton Roads on 17 June, visiting the USN Academy of Annapolis, Maryland, on the 20th, and conducting exercises off the Virginia Capesbefore making an upkeep in Norfolk until 1st July and departed for her shakedown off Trinidad. From Port of Spain Hampton Roads she returned to Boston and post-shakedown fixes, like a leak discovered in the main battery hydraulic piping. With USS Sigourney she departed for the west coast in September via Panama, arriving in in San Diego on 4 October and trainjng there before sailing for Pearl Harbor on the 29th and from November 1943 to June was assigned to the fire support for the Makin Islands landings, Kwajalein, Truk raid, Eniwetok.

USS Baltimore next was in the Marianas (21–22 February 1944), Palau-Yap-Ulithi-Woleai campaign, Hollandia landings in April, Truk-Satawan-Ponape raid until 1st May, Marcus and Wake and the Saipan invasion on 11–24 June 1944 closing the first leg of her active wartime carreer with the Battle of the Philippine Sea in June. She was back for an overhaul and crew leave in July 1944 and embarked President Franklin D. Roosevelt for a cruise to Pearl Harbor underway, also hosting Admiral Chester Nimitz and General Douglas MacArthur while sailing in and back in August.

She was back in combat by November 1944, missing the battle of Leyte but being assigned to the 3rd Fleet for the assault on Luzon in December to early January 1945, the raids on Formosa and the China coast and the start of her Okinawan campaign. On 26 January she was assigned to the 5th Fleet for the attacks on Honshū in February, Iwo Jima and various support raids for Okinawa until 10 June. In July she was replenishing before returning for more raids along the Japanese coast, and was after 15 August part of the naval occupation force in Japan from 29 November 1945 to 17 February 1946, making before a single “Magic Carper” mission home, for s amll overhaul and crew’s leave.

USS Baltimore off Mare Island Naval Shipyard, 18 October 1944

Placed in reserve on 8 July 1946 at Bremerton, in rapid-return preservation, she was recommissioned on 28 November 1951 and operated with the Atlantic 6th Fleet operating in the Mediterranean until 1954. In June 1953 in between she took part in a Fleet Review at Spithead. On 5 January 1955 she was sent after overhaul to the Pacific and 7th Fleet operations in the Far East, Korean war in February-August 1955. Back home, she was placed in pre-inactivation overhaul, decommissioned, long term Pacific reserve in Bremerton on 31 May 1956. Her active career only was 6.75 years when she was stricken on 15 February 1971 and sold on 10 April 1972 to Zidell Ship Dismantling Company Portland to be scrapped. She earned for her service the Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal with nine battle stars.

USS Boston (CA 9)

USS Boston (CA 9)

USS Boston in 1944

USS Boston reported to the Pacific Fleet, Pearl Harbor after commission, shakedown and training on 6 December 1943. Assigned to Task Force 58 in January 1944 she covered the Marshall Islands raids: Kwajalein, Majuro, Eniwetok until 28 February 1944, followed by the Palaus and Western Carolines, Hollandia, Western New Guinea, Truk (where she shelled Satawan Atoll until 1 May). USS Boston was at Saipan in June, supported the Bonin Islands raids, and took part in the Battle of the Philippine Sea, giving her the occasion of towing out of hartm USS Houston torpedoed after an air attack.

USS Boston was back in the Marianas for the landings on Guam in July, until 15 August, followed by the raids on Palau-Yap-Ulithi (25-27 July), Morotai on 15 September, southern Palaus, the Philippine Islands until 24 September. She accompanied TF 38 for the first Okinawa raid (10 October 1944), northern Luzon, Formosa, and the Battle of Leyte Gulf on 24 October, followed by more Formosa raids in January 1945. After other operations on Luzon and the Chinese mainland, Nansei Shoto, Honshū in February and Japan in March, all guns blazing directly at the coast.

USS Boston was back home afterwards for an overhaul in Long Beach CA from 25 March 1945 before returning to the Pacific via Pearl Harbor and Eniwetok, assigned to TF 38 operating off the home islands until 15 August 1945 and the war’s end. She covered the occupation forces until 28 February 1946 and returned home to be decommissioned at Puget Sound on 29 October. Her career would continue postwar and she added to Korea thz Vietnam war, after a comprehensive refit as a hybrid missile cruiser (CAG-1), her career ending when she was stricken on 4 January 1974. The details of her career would be seen with a dedicated article of the Boston class. For her WW2 service she earned 10 battle stars.

USS Camberra (CA 9)

USS Camberra (CA 9)

USS Canberra underway, 9 January 1961

CA-70 was at first named USS Pittsburgh, but this was changed for Canberra to honor the loss of the Australian cruiser. After commission on 14 October 1943, shakedown and training, post-trials fixes, and post-shakedown fixes, she was prepared for combat, and left Boston in January 1944 to San Diego via Panama, assigned to Task Force 58, joined via Pearl Harbor in mid-February. By late February she supported the invasion of Eniwetok, assigned to the USS Yorktown carrier TG, following her for the raids on the Palaus, Yap, Ulithi, Woleai until April, Hollandia and Wakde.

Then, from 29 April to 1 May she was assigned to USS Enterprise TG for the great raids on Truk, where she was detached herself to directly shell a Japanese airbase at Satawan. Next she took part in operations on Marcus and Wake Islands, Mariana and Palau Islands in June, the Battle of the Philippine Sea and shelling later the Bonin Islands. By the end of the summer she took part in the Palaus-Philippines raids, the Morotai landings and in October with TF 38 covered air raids on Okinawa and Taiwan in preparation for the Leyte landings.

On 13 October a lone Japanese aircraft evaded the CAP and managed to hit the cruiser below her armour belt, the detonation killed 23 while the gash was quickly flooded and she stalled, frantic efforts being made to stop the flooding and repair her. Eventually, USS Wichita took her under tow until the tug USS Munsee took charged. After a week she reached Ulithi, where Munsee was joined by the tug Watch Hill and meeting the repair ship USS Ajax at Manus, before she was capable to sail to Boston NyD for major repairs, until October 1945. After she war she served first off west coast of the United States and seven battle stars.

Like her sister Boston she was scheduled for a transformation into an hybrid missile cruiser (CAG-2), so she could take part in the Vietnam war, and being deactivated and stricken on 31 July 1978.

USS Quincy (CA 71)

USS Quincy (CA 71)

USS Quincy underway, Pacific, 1952-54

After her shakedown cruise in the Gulf of Paria (Trinidad-Venezuela) Quincy (named after a New Orleans cruiser lost earlier and originally St.Paul) was assigned 27 March 1944 to Task Force 22. After intial training in Casco Bay, Maine, she reached Belfast to meet TG 27.10, 12th Fleet, visited at this occasion by General Dwight D. Eisenhower and Rear Admiral Alan G. Kirk on 15 May. She headed for the Clyde and Greenock in Scotland, having a special training for shore bombardment, to take part in the invasion of Europe. Her Kingfisher pilots were assigned for extra spotting training to the VOS-7 flying Spitfires at RNAS Lee-on-Solent. So she was sent with the armada and at 05:37, on 6 June 1944, opened fire at Utah Beach. She became the sole of her class to take part in D-Day.

CinC Eisenhower onboard USS Quincy in May 1944

On 6-17 June she made a serie of highly accurate striked on mobile batteries and tank and vehicles concentrations, all moving targets, receiving congratulations for her marskmanship. She neutralized long range batteries and later supported minesweepers and protected the crew evacuation of the damaged USS Corry (DD-463) and Glennon (DD-620) off Quinéville on 12 June. She retired to Portland on 21 June and was reassigned to TF 129, heading for Cherbourg, helping to silence batteries during the army assault and the city fell on the 26th.

Next, USS Quicy was sent to Mers-el Kebir, the former French base on North Africa on 4 July to operate off Palermo from 16 July untim 26 July for more shore bombardment practice and heading for Malta via Messina, for more training exercises. On 13 August she departed Malta for the French riviera (southern coast) and Baie de Cavalaire 15 August. She gave three daus of intensive fire support, on the left flank, covering the progression of the 7th Army. Rassigned to TG 86.4 she engaged Toulon, St. Mandrier, and Cape Sicie batteries. On 24 August she support minesweepers clearing Port de Bouc, Marseilles.

Franklin D. Roosevelt and King Ibn Saud onboard USS Quincy, 14 February 1945

On 1 September she was relieved from her European service and sent back to Boston for an overhaul until 31 October, followed by more training in the Casco Bay and equipped for a Presidential cruise, heading for Hampton Roads, on 16 November to take aboard President Franklin D. Roosevelt and his party on 23 January 1945 at Newport News, heading for Malta (2 February) and hosting British PM Winston Churchill and other dignitaries, while the president disembarked and flew to Crimea to attend the Yalta Conference.

Departed Malta on 6 February 1945 for Great Bitter Lake, Suez Canal after stopping at Ismalia in Egypt she received aboard the President and his party on 12 February and hosted King Farouk and Haile Selassie then on 14 February, King Abdul Aziz (Saudi Arabia) discussing about Jewish immigration to Palestine and devising a secret agreement for providing military security, assistance, training in exchange of oil, plus a base at Dhahran. President Roosevelt met again abord PM Churchill before heading for Algiers (18 February) for a enw conference with the ambassadors or France and Italy. Next, she departed for Newport News arriving on 27 February.

At last, USS Quincy departed on 5 March for the pacific, via arriving Pearl Harbor for some training, Eniwetok, and her final station at Ulithi for the 5th Fleet (11 April 1945). She departed to join Rear Admiral Wiltse’s Cruiser Division 10, assigned to protect Mitscher’s Fast Carrier Task Force (TF 58). From 16 April, she supported air strikes on Okinawa, Amami Gunto and Minami Daito Shima. In May these were over Kyushu and Amami Gunto, giving her the occasion of downing a Japanese plane on the 14th while her Kingfishers were engaged strafing targets in Omonawa, Tokune Shima, Kikai Jima, Amami Gunto, Asumi Gunto and departed for the Philippines on 13 June, weathering a severe typhoon on 5 June.

She replenished in Leyte while RADM Wiltse (ComCruDiv 10) transferred hos flag to Quincy. On 1 July she departed with TF 38 for the final mission againstJapan’s home islands, until 15 August. On the 23th she was part of the Support Force, for the occupation of Sagami Wan, and entering Tokyo Bay 1 September. No longer flagship on the 17th, she joined the 5th Fleet, part of the larger Eastern Japan Force (TF 53) in Tokyo Bay. Back home at Puget Sound she was decommissioned on 19 October 1946, Pacific Reserve Fleet. On 31 January 1952 she was recommissioned to join the 7th Fleet operating in Korea. She was part of the screen of the Fast Carrier Task groups from 25 July 1953 to 1 December 1953 and back home, was decommissioned for the last time on 2 July 1954 at Bremerton. She never received the new 3-in/50 twin AAA mounts and kept her 40 mm guns until she was stricken was stricken on 1 October 1973.

USS Pittsburgh (CA 72)

USS Pittsburgh (CA 72)

USS Pittsburgh underway, 11 October 1955

USS Pittsburgh was commissioned on 10 October 1944 and cruised on the east coast and Caribbean before stopping for post-shakedown fixes and preparations for the Pacific in Boston. By 15 January 1945 she departed, crossed, Panama and joined Hawaii where she made final gunnery drills before being assigned to the Fast Carrier Task Force 58 and USS Lexington’s Group she met at Ulithi on 13 February. The assault on Iwo Jima and Tokyo raids were her first missions, throughout February, as well as the Ryukyus from 1st March.

After a leave and resplenishment in Ulithi on 14 March she covered another raid on Kyūshū on the 18-19 and on the 20th as USS Franklin was badly damaged, USS Pittsburgh came alongside for a rescue, later joined by USS Santa Fe, launching a tow line on board and she went on in her effort until midday, later Franklin proceeded under her own power. On 23 March-27 April USS Pittsburgh took part in the invasion of Okinawa. She was also called to repel massive Kamikaze attacks while her scout planes were busy rescuing downed pilots. After the next resplenishment at Ulithi, the 8 May attack on the Ryukyu Islands and Southern Japan commenced.

On 4 June like the rest of the fleet, she weathered Typhoon Viper, with 70-knot (130 km/h) winds, 100-foot (30 m) waves. She had damage though: Her starboard scout plane was blown off the catapult and dashed onto the deck and her second deck buckled, the bow was thrust upward and sheared off. Amazingly eveybody survived it. Nose-less, Pittsburgh resisted other waves by engine power while the teams worked frantically to make her forward bulkhead waterproof, during seven gruelling hours. Pittsburgh left the fleet for Guam at 6 knots and made it here on 10 June. Her bow was later salvaged by USS Munsee. It was no less than a 104-foot section. Later inspection revealed the breakage was due to poor quality plate welding at Bethlehem. The crew, which, which again, were safe after this, jovkingly nicknamed her the “Longest Ship in the World” as her bow was thousands of miles away.

A false bow was constructed so Pittsburgh left Guam on 24 June for Puget Sound. Repairs started after 16 July and the war ended. Placed in reserve on 12 March 1946, decommissioned on 7 March 1947 she was placed in long term reserve. Due to her short prestation she only won two battle stars. However the Korean War urged her restoration and she was recommissioned on 25 September 1951 and departed on 20 October for the Panama Canal while training off Cuba, then arrived in Norfolk for her fiorst deployment with the Mediterranean 6th Fleet. After 20 May, she was back with the the Atlantic Fleet for exercises.

She made a second Mediterranean tour of duty from 1 December as flagship, Vice Admiral Jerauld Wright (CiC Naval Forces Eastern Atlantic and Mediterranean), making a good-will cruise to the Indian Ocean (January 1953) and back to Norfolk for overhaul and modernization. Next she made her 3rd TOD from Gibraltar (19 January 1954) still with Admiral Wright aboard, and back on 26 May. On 29 July 1954 she collided with a ship in the Saint Lawrence River but damage was only above the waterline and repairs were quick.

On 21 October 1954 she was sent again in the Pacific Fleet, sailing from her new home port of Long Beach. She stopped at Pearl Harbor on 13 November, reaching Yokosuka on 26 November. She met the 7th Fleet watching over the Chinese Nationalist offensive in the Dachen Islands for civilian safety. By February 1955 after an overhaul in Japan, she sailed for Puget Sound Naval Shipyard, arriving on 28 October and deactivated. Place into reserve on 28 April 1956, fully decomm. on 28 August 1956 she was stricken on 1 July 1973, scrapped by Zidell Explorations Corp. in Portland.

USS St. Paul (CA 73)

USS St. Paul (CA 73)

USS Saint Paul off Wonsan, Korea, 20 April 1951

After her Caribbean shakedown cruise, USS Saint Paul, commissionned on 17 February 1945, departed Boston on 15 May for the Pacific. As customary she traoned in Pearl Harbor on 8–30 June and it’s only on 2 July that she joined Task Force 38. After a replenishment on 23 July at sea, she accompanied the fast carrier force to its launching points for strikes against Honshū and until 10 August, screened them during their raids on Kure, Kobe, Tokyo area, southern Honshū, Maizuru and northern Honshū.

She herself fired for the first time her main artillery on industrial targets, textile mills at Hamamatsu (29 July), iron and steel works in Kamaishi (9 August) among the last salvoes of the war, while her AA crews downed the last Kamikaze. Typhoon warning had her on the move on 11–14 August and the following days cancellation due to ppeace negociations and surrender. For her (short) service, she only earned one battle star, but her cold war service was quite long and totalled 26 years, and a few months in WW2.

AfterV-day she retired with the 3rd Fleet southeast, patrolling the coast and on 27 August entered Sagami Wan in support of occupation forces. On 1 September, she entered Tokyo Bay to witness the formal surrender ceremony, remaining afterwards in Japanese waters and proceeded to Shanghai on 5 November, assigned to TF 73 as flagship. She entered the Huangpu River and anchored off the Shanghai Bund on 10 November, stil there in early 1946. During her stay she collided with the landing craft LST144 but damage was light.

On 7 January 1946, she departed with USS Keith for home. She arrived at Terminal Island (CA) on 28 January 1946 for a short refit and by May was in Pearl Harbor and back to Terminal Island on 1 August, properly overhauled adnd making a training crew on 1–15 February 1947 off San Diego. She was back in Shanghai in March as flagship, TF 71 and back home in November. She made her second deployment in August–December to the western Pacific. Back home her catapults were removed and a spot painted to operate helicopters. She made another tour of duty in the Far East in April-October 1949.

The rest of the career comprised the Korean War, and was overhauled again in 1955, served in her WW2 configuration in the far east until 1957 and 1962, Based at Yokosuka, but she was not extensively modernized into a guided missile cruiser. She was the main protagonist of the motion picture “In Harm’s Way” starring John Wayne. She would have the occasion to fight in Vietnam as well, firing on various targets in North Vietnam in October 1966 and continue her service with the 7th Fleet off North and South Vietnam. On 1 September 1967 she received a shell on her starboard bow, but the damage was repaired quickly. She earned the Navy Unit Commendation and two Meritorious Unit Commendations for her Vietnam service until 1969, added to her Korean Service Medal with eight battle stars.

Back in San Diego on 7 December 1970 she started inactivation, completed in Bremerton, Washington, on 1 February 1971, decommissioned on 30 April, placed in reserve at Puget Sound Group, Pacific Reserve Fleet, stricken on 31 July 1978 and sold for BU in 1980. She could have been turned as a museum ship due to her still original “gun configuration”, but this never happened.

USS Columbus (CA 74)

USS Columbus (CA 74)

USS Columbus off the coast of Spain, 12 July 1948

USS Columbus, despite her order in 1940, was only laid down in June 1943 and completed two years later, on 8 June 1945. The war was over in Europe, and in Japan, close to conclusion. She made her Carribean shakedown cruiser, training, headed for Pearl Harbor and made more training, at whoich point the war was over. She reached Tsingtao in China on 13 January 1946, helping occupation forces. On 1 April, she sank 24 captured Japanese submarines and was back to San Pedro in California, operating on west coast waters and making another Far Eastern cruise (15 January-12 June 1947).

Back home she underwent an overhaul at Puget Sound Naval Shipyard and departed on 12 April 1948 for the Atlantic Fleet, making Norfolk her new home port in May. She made two cruises as flagship for the Naval Forces Eastern Atlantic and Mediterranean. On 13 September 1948-15 December 1949, 12 June 1950-5 October 1951, she stayed as flagship, Supreme Allied Commander of the Atlantic fleet, taking part in NATO Operation Mainbrace, cruised the Mediterranean until January 1953 and as flagship, 6th Fleet, Cruiser Division 6 until January 1955, overhauled in between.

Back in the Pacific Fleet, she was relocated to Long Beach in California from 2 December and on 5 January 1956 headed for her provisional home port, Yokosuka, to serve with the 7th Fleet; She made two deployment, in 1957 and 1958, patrolling the Taiwan Straits and watching over Chinese communists deployments. In late 1958 the admiraty wanted her as a candidate for missile conversion, which was acted on 8 May 1959 in Puget Sound Naval Shipyard, as an Albany-class. The rest of her career would be seen in a dedicated post.

USS Helena (CA 75)

USS Helena (CA 75)

USS Helena underway c1961

Missing WW2

USS Helena was completed in Boston (launched in April) and commissioned right away on 4 September 1945. The war was already over, but still, she departed on 24 October for New York City (Victory celebrations), and made two shakedown cruises off Guantánamo Bay in Cuba before post-fixes in Boston. By February 1946 she was prepared for a round-the-world cruise with Admiral H. Kent Hewitt in board, so she became flagship, Commander Naval Forces, Europe for the 12th Fleet. She trained in Northern European waters and made several stopovers between England and Scotland.

In May she transited via the Suez Canal to asia, stopping en route to Mediterranean ports. She arrived in Colombo and moved to Singapore and then Qingdao in China on 18 June 1946. After training exercises and fleet maneuvers she departed Shanghai on 22 March 1947 for home waters, and after some training off California, she departed for asia again on 3 April 1948 (Shanghai) and patrolled in Chinese waters (as the Chinese civil war raged on), before heading back to Long Beach by December.

USS Helena trained in early 1949 and from May with Naval Reservists before heading back to Long Beach for a helicopter conversion. This summer, she took part in a six-week training cruise for the Naval Reserve Officers’ Training Corps, bringing them to the Galapagos and Panama. Next was Operation Miki, joint Army/Navy amphibious training in Hawaii by November 1949. She headed next for Yokosuka and Hong Kong, then the Philippines for exercises and back to Japan in January 1950, becoming flagship, 7th Fleet with Joint Chiefs of Staff aboard touring East Asia from 2 February. She took part in large-scale fleet exercises off Okinawa and sailed back home on 21 May.

War in Korea

Helena was scheduled for a summer cruise followed by an overhaul at San Francisco but war in Korea forced hare at sea on 6 July 1950 to Pearl Harbor and to the coast of Korea. On 7 August, she first her guns on railroads, trains, and power plants near Tanchon. She became flagship of the Bombardment Task Group, helping taking the invaders off balance during which the United Nations prepared counter-Operations. Her attacks provided a diversion to cover the assault into Inchon on 15 September. It was followed by gunfire support during the push along the east coast, and she single-handily created a diversion at Samcheok, helping recapture Pohang. By November 1950 she was at Long Beach for overhaul.

She was based afterwards in Sasebo from 18 April 1951, TF 77, covering the fast carrier group, and often detached to shell shore targets. Late ion July she was hit by shore gunfire but damage was light and she silenced all guns positions. After a respite in Yokosuka she was detached from TF 77, for a “special duty” acting as radar picket for a massive raid over Rason. Her accurate gunnery was “loaned” by the 8th Army in support of infantry, also supportined Marines and ROK units. After a resplenishment in September 1951 in Yokosuka, visited by President Syngman Rhee she received the first Korean Presidential Unit Citation, representing TF 95. Later she resumed operations in the Hungnam-Hamhung area, using her helicopter for efficient spotting.

Helena was in Long Beach next to have in December 1951 her worn out battery replaced. In February, after training and participation to the exercize “Lex Baker One” (with 70 ships), she was back in Yokosuka on 8 June 1952, meeting TF 77 for 5 months of more shore bombardments, and pilot air rescue. On 24 November she was relieved and sent for a special mission. She was visited in Iwo Jima by Admiral Arthur W. Radford (Pacific CinC) and in Guam, visited by Dwight D. Eisenhower and staff, confering with and Admiral Radford to Pearl Harbor, reached on 11 December 1952, proceeding to Long Beach afterwards. Her captains were during the Korean war, Larson, Harold Oscar. (Swede), Martin, Lawrence H., and Dyer, Walter Leo. until June 1953. She earned also the Korean Service Medal with four stars.

Post-Korean service

Helena was back to the far east on 4 August 1953, TF 77 but only for security patrols in the Sea of Japan. She joined the 7th Fleet at Yokosuka, as flagship from 11 October 1954. In February 1955 she assisted the evacuation of the Dachen Islands. She was in Yokosuka on 25 January 1956, served off Taiwan area and in Philippines, but was in Long Beach on 8 July, alterations beign made, with new masts and electronics, enclosed navigation and flag bridges. Exercizes in home waters saw her testing the Regulus I missile as a launching gear was installed aft. These tests went on for 9 months. On 10 April 1957 she returned to the Pacific, as flagship and was back to Long Beach on 19 October. Her major overhaul ended on 31 March 1958 followed by intensive training and missile launching, and a 1958 Far East cruise for 3 August, based in Keelung, Taiwan from 21 August. She also visited Manila but returned to watch Quemoy and Matsu operations.

On 7 September she made a show of force just 10 miles (16 km) of the Chinese mainland, again directed at Quemoy Island. On 9 October while off the Philippines her helicopters rescued men, women and children from a large boat people, to Hong Kong. On 5 January 1960 she operated in the Pacific with USS Yorktown and DesRon 23. She took part in the very large training Operation Blue Star. With USS Ranger and Saint Paul whe headed for Guam and sail for Australia and back to Long Beach for an overhaul. By mid-January 1961 she became the permanent flagship of Commander, 1st Fleet.

On 17 May 1961, the 12-vessels strong 1st Fleet led by Helena conducted a firepower demonstration for the American Ordnance Association. In June she cruised with the Secretary of the Navy on board to Portland for the Rose Festival. She later took part in Exercise Tail Wind with USS Los Angeles, USS Coontz and destroyer escort. She weathered the Typhoon Olga off Hong Kong and was back in San Diego to participate in Exercise Covered Wagon and afterwards, Exercise “Black Bear.”

In 1961-1962 she took part in several amphibious operations, always as head of the 1st Fleet and the 1st Marine Division, 3rd Marine Air Wing. In late 1962 she was scheduled for inactivation at Long Beach and on 18 March 1963, her flag was transferred to USS Saint Paul. Decomm. on 29 June 1963, after 18 years of service she was sent in the San Diego Group Pacific Reserve Fleet, stricken on 1 January 1974, sold to Levin Metals Co. in November to be scrapped in 1975.

USS Chicago (CA 136)

USS Chicago (CA 136)

USS Chicago off the Philadelphia Naval Shipyard, 7 May 1945

USS Chicago, named after another sunken prewar cruiser in the early phase of the Pacific war, (CA-29 of the Northampton class), was commissioned on 10 January 1945. She spent six weeks preparing for sea duty and made her first cruiser on 26 February 1945 to Norfolk, she calibrated her compasses in Chesapeake Bay and on 18 March trained in the Gulf of Paria in Trinidad, starting her shakedown cruiser and first shore bombardment exercises off Culebra in Puerto Rico, and fixes in Norfolk on 11 April. She seh sailed with DD USS Alfred A. Cunningham, for the Caribbean in 7 May, and from there, to the Pacific Ocean via Panama.

All along she proceded to various anti-air, gunnery, and radar tracking drills. She arrived at Pearl Harbor on 31 May and after more training off Kahoolawe Island, she departed for Eniwetok in Marshall Islands, on 28 June, with USS North Carolina refuelling on 5 July and escorted by USS Stockham, joined Rear Admiral Radford’s TG 38.4 north of the Marianas. Her primary role was in the anti-aircraft screen, during the Tokyo Plains raids and on Honshū from 10 July, and later Hokkaidō. On 14 July, with South Dakota, Indiana, Massachusetts, Quincy, nine destroyers (RADM Shafroth bombardment group) she pounded northern Honshū, flatterning the Kamaishi industrial area. Between pre-plotting via photo recce and radar positioning her fire was precise and efficient despite the smoke. At 12:51 her secondary battery gunsopened up on a spotted Japanese destroyer-escort vessel, which was repelled and retired into the harbor.

On 15 july she acted as “temporary seaplane carrier” when Iowa transferred her SC Seahawk floatplanes. One was catapult-launched for spotting. After 16 July replenishment she resumed cover for the Tokyo Plains/northern Honshū/Hokkaidō/Kure-Kobe raids. On the 29th with HMS King George V she took part in a night shore bombardment on Hamamatsu. Spotting planes dropped flares and rockets to lit up the area, which was pounded for an hour. Next were raids on the Tokyo-Nagoya area.

The fleet retired to avoid a typhoon, and returned until 9 August when RADM Shafroth’s unit returned to Kamaishi. They made a two-hour bombardment and during the next six days, USS Chicago screened the carriers for their last Home Islands raids, ending on 15 August. She remained until 23 August and dropped anchor in Sagami Wan on 27 August before proceeding to Tokyo Bay on 3 September, taking part in occupation forces work. After a stop at Yokosuka until 23 October she took part in an operation in the Izu Islands. For 12 days, she landed inspection teams surveying full disarmament. On 7 November she departed at last for San Pedro, arriving on 23 November.

After her Long Beach overhaul she was back in the Pacific on 24 January 1946, anchored in Shanghai on 18 February for occupation duty until 28 March (flagship of the Yangtze Patrol) and the Sasebo as flagship, Naval Support Force. She headed back to the US west coast on 14 January 1947, Puget Sound for decommission and reserve on 6 June 1947.

On 1 November 1958, she was inspected and given her excellent state, chosen for conversion as a missile cruiser, reclassified CG-11, transformed completely at San Francisco Naval Shipyard during five-years, as part of the Albany class. Her career will be seen as part of the latter class article. Her war records included Vietnam and she was decommissioned again on 1 March 1980.

USS Bremerton (CA 130)

USS Bremerton (CA 130)

USS Bremerton (CA-130) off San Francisco, 1955

Commissioned on 29 April 1945, her wartime (and overall) career was short, but dual (WW2 and Korea). USS Bremerton left Norfolk for her shakedown cruise off Guantanamo Bay, Cuba in late May 1945 and she briefly served as flagship for Admiral Jonas Ingram CinC Atlantic Fleet during his South American tour. She was not deployed in the Pacific, but instead was used for experimental work at Casco Bay, Maine, 22 July-2 October 1945. On 7 November she trained off Guantanamo Bay and at least sailed to Pearl Harbor and the 7th Flee, arrived on 15 December 1945 to proceed newt to Inchon, Korea on 4 January 1946 and remained there until 20 November 1946 before returning to San Pedro in California, and participate in more training off the west coast. She was decommissioned at San Francisco, 9 April 1948.

Recommissioned on 23 November 1951 as the war broke out in Korea, she was prepared for deployment, and after her refresher training cruise, joined the 7th Fleet, firing there on Wonsan, Kojo, Chongjin, and Changjon Hang. On 13 September 1952 she was replaced and returned to Long Beach. After a 7 month overhaul and drills, she departed on 5 April 1953 to join again the 7th Fleet and TF 77, continuing her shore gunnery missions. From November 1953 in Long Beach she had another overhaul, followed by extensive training and she was back off Korea on 14 May 1954 (Captain Will P. Starnes took command). On 17 October she was back to Long Beach.

In January 1955, she was in Mare Island Navy Yard, Vallejo, for overhaul, having her improved habitability and fighting efficiency program applied. She was later back to the Far East as flagship, RADM D. M. Tyree, CruDiv1, and later RADM H. L. Collins, then VADM A. M. Pride, 7th Fleet based in in Keelung, Formosa (Taiwan). She took part in many operation amidst the Chinese civil war with Task Force 77, earning a second China Service Medal. On 10 January 1956 in Yokosuka, Commander Robert M. Brownlie took command. On 12 February she sailed back to Long Beach (Charles C. Kirkpatrick took command there) and she was awared white “E” and a green “E” for Battle Efficiency excellence among Pacific Fleet cruisers FY1956.

On 6 November 1956 she headed for Melbourne and visited Redondo Beach, Monterey, Victoria, British Columbia, Seattle, Pearl Harbor, Guam, Kwajalein Atoll, Yokosuka, Kobe, Beppu, Okinawa, Keelung, Formosa, Kaohsiung, Manilla and Olongapo, Hong Kong and the Dingalon Bay before heading back for Long Beach in May 1957. She was selected for conversion to an Albany class guided missile cruiser (redesignated CG-14) but was later cancelled due to budget constraints and she decommissioned on 29 July 1960, placed in long terme reserve and stricken on 1 October 1973, sold to Zidell Explorations and scrapped in 1974.

USS Fall River (CA 131)

USS Fall River (CA 131)

USS Fall River at anchor, 12 August 1945

USS Fall River (CA-131), launched on 13 August 1944 at NyD Camden, was commissioned on 1 July 1945, in the dying days of WW2, under command of Captain David Stolz Crawford. After early training shakedown cruis in the Carribeans and further drills plus post-shakedown fixes, she was not ready for combat on 15 August and it’s only by 31 October 1945, that she arrived in Norfolk for a set of experimental development operations until 31 January 1946.

Assigned to JTF 1 she was the floating bas for Operation Crossroads, the Marshall Islands atomic tests of the summer of 1946. She sailed to San Pedro and until 6 March was altered for her task as flagship. She was in Pearl Harbor on 17 March to board RADM Frank G. Fahrion, group commander for the tests, and sailed from 21 May, arriving and testing on 14 September.

Back home she resumed West coast training, and started a first tour of duty in the Far East, as flagship CruDiv 1, from 12 January 1947 to 17 June 1947. Back to Puget Sound Navy Yard, she was placed out of commission and in reserve on 31 October 1947. Although she could be converted later as an Albany-class guided missile cruiser, these prospects were cancelled due to economic constraints and she was kept in reserve fleet until stricken on 19 February 1971, sold for BU on 28 August 1972. Only her upper bow survived and is on display today at Battleship Cove. Her career was fairly short and she never fired a shot in anger.

USS Los Angeles (CA 135)

USS Los Angeles (CA 135)

USS Los Angeles in the Far East, 13 October 1952

Commissioned on 22 July 1945, like her sisters Fall River, Toledo and Macon, she never had the time to be deployed. At least six months were required between early training, shakedown cruise to and from Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, fixes and advanced training and the war ended in between. She only sailed on 15 October for the Far East via the west coast. She first arrived in Shanghai on 3 January 1946 and was assigned to thee 7th Fleet patrolling along the coast of China and western Pacific, to the Marianas. Back to San Francisco on 21 January 1947 after this only sortie, she was decommissioned at Hunters Point, 9 April 1948, Pacific Reserve Fleet.

Unlike USS Fall River however, she was recommissioned on 27 January 1951 to take part in the Korean War, with Capt. Robert N. McFarlane in command. She departed after training and preparation on 14 May and started operations off the eastern coast of Korea on 31 May, as flagship RADM Arleigh A. Burke’s CRUDIV 5. For six months she pounded various objectives from Hungnam to Haeju and was back home on 17 December for overhaul and training, followed by her second TOD in Korean waters on 9 October 1952.

On 11 October, she was part of a concentrated shelling of enemy bunkers at Koji-ni. Later for weeks on end, she supported ground operations, and cruised in the Sea of Japan with the 7th Fleet. In late March she bombarded Wonsan and in April 1953 received some hits from enemy shore batteries doing little damage; She resumed operations in mid-April until departing for home, arriving at Long Beach on 15 May.

Until June 1963 she would make eight more deployments in the Pacific, as cruiser division flagship, 7th Fleet. She patrolled and showed the flag between the coast and sea of Japan to the Yellow Sea, South China Seas, the Philippines and Okinawa, and touring various Allied bases between South Korea, Hong Kong, Australia, and Taiwan. The 1956 Quemoy-Matsu crisis showed her in the Taiwan Strait, protecting ROC units waiting for a communist landing. Back home for an overhaul, she patrolled from Long Beach and between the west coast and the Pacific via Pearl Harbor. Her final Pacific TOD started on 20 June 1963.

It was at this point consdered to convert USS Los Angeles into a dedicated Talos missile cruiser, with flagship facilities, an equivalent of the USS Oklahoma City, but funds were not authorized, and only good for a general overhaul and for fleet service. She was decommissioned at Long Beach, 15 November 1963, Pacific Reserve Fleet (San Diego). Stricken on 1 January 1974, she was sold for BU on 16 May 1975 and scrapped at San Perdo, but her flying bridge and bow part are on display at the Los Angeles Maritime Museum of San Pedro.

USS Toledo (CA 133)

USS Toledo (CA 133)

USS Toledo at anchor circa 1949

USS Toledo was only commissioned 27 October 1946 after her construction was suspended due to the war end. She was launched indeed on 6 May 1945. On 6 January 1947, after her shakedown cruise to Guantanamo Bay and fixes, she made another two-month training cruise in the West Indies, via St. Thomas, Kingston, Port-au-Prince and back to Philadelphia plus post-shakedown availability. On 14 April 1947 she departed Philadelphia for the Atlantic and Mediterranean, then transited the Suez Canal and entered the Indian Ocean, going further east to Yokosuka on 15 June.

She visited Japanese and Korean ports until October 1947 and departed for her first transpacific voyage via Pearl Harbor to Long Beach (5 November). On 3 April 1948, she departed with USS Helena (CA-75) for Yokosuka and during her patrols, caught many contraband smugglers. She made that summer a goodwill cruise to the Indian Ocean and stopped in Pakistan but also Singapore, Trincomalee and Bombay. She operated from Tsingtao to assist the evacuation of Chiang Kai-shek’s forces to Formosa (later Taiwan). On 16 September she departed for Bremerton and Puget Sound NyD for her first overhaul staring on 5 October and completed on 18 February 1949.

Back to Long Beach and six months of training down to Panama she took part in Operation Miki, a simulated attack on Pearl Harbor. On 14 October, she departed for the Far East and stayed there for eight months, visiting along the way the Philippines and Marianas and back to Long Beach on 12 June, just before the war started in Korea. She was prepared hastily to depart for her fourth eastern deployment and first tour of combat duty.

USS Toledo’s Korean War

USS Toledo, Tokyo Bay, 1959, Tokyo Bay and Fuji-San behind.

USS Toledo made a brief stop at Pearl Harbor en route and continued onto Sasebo. There, she became flagship, RADM J. M. Higgins (CruDiv 5) on 18 July 1950. She was posted off the eastern coast of Korea, Pohang, near Yongdok. With CruDiv 5 and DesDiv91 she brought support to Task Group 95.5. and until 30 July with her escorts USS Mansfield (DD-728) and Collett (DD-730) she shell all North Korean objectoves designated around Yongdok. On 4 August she took in a combined air-sea strike and her shelling was helped by airborne controllers and confirmed by front-line troops. Between there and Samchok she cruised and shelled along 25-miles. She was relieved by USS Helena and returned to Sasebo.

Back on duty on 15 August with USS Rochester (CA-124), herself protected by USS Lyman K. Swenson (DD-729) she patrolled a 40-mile coastal area from Songjin to Riwon. Back in Sasebo on the 26-31 August she was back off Pohang Dong and later supported the landing at Inchon (mid-September 1950). She pounded Wolmi-do Island, defending the harbor approach with the cruisers HMS Jamaica and Kenya on 13 September, led by night by the destroyers. Ttwo days of preparatory bombardment were followed by the landing of 3rd Battalion and 5th USMC on Wolmi-do. Toledo made direct support on demand fire, as well later at “Blue Beach”, south of Inchon. These missions wene on until early October until back to Sasebo.

She operated off Chaho Han on 13 October, for the Wonsan attack, and back to Sasebo. She returned several time off Wonsan and on 22 October departed via Yokosuka and Pearl for home. She entered Long Beach on 8 November and headed for San Francisco, Hunter’s Point Naval Shipyard, for an overhaul lasting until February 1951. After a refrsher training cruise she departed via Pearl Harbor to Sasebo, and her second tour of duty in Kore. In April-May she cruised off the coast off Inchon and pounding positions along the Han River line during the spring offensive. On 26 May she operated off Kansong with TE 95.28 (interdiction bombardment) and on 28-30 May, shelled advanced elements at extreme range. In June she was at Yokosuka and back, with USS Duncan and Everett, bombarding Songjin.