The last British heavy cruisers

Development of the “Class B” – York design

The County class is generally known as Washington cruiser design “Class A” cruiser, reaching the top of what could be done within the 10,000-ton range. However already when they were designed in the 1920s it was thought of a second-rate cruiser design called “Class B”, already with budget constraints in mind, before the 1929 crash. The displacement of 8,500 tons needed to do many drastic changes in the final design, which was approved in 1927. It was even before the global stock market crisis. Based on these limitations, the engineers did wonders.

The York class was afterwards found as a very convenient design by the admiralty in a context of budget-constraints.

The tonnage was the first concern. The large, roomy hull of “County” was scrapped and the final design returned to a more classic forecastle model, shorter by more than almost twenty meters. But the most significant sacrifice was a turret 203 mm (so six 8-in guns instead of eight).

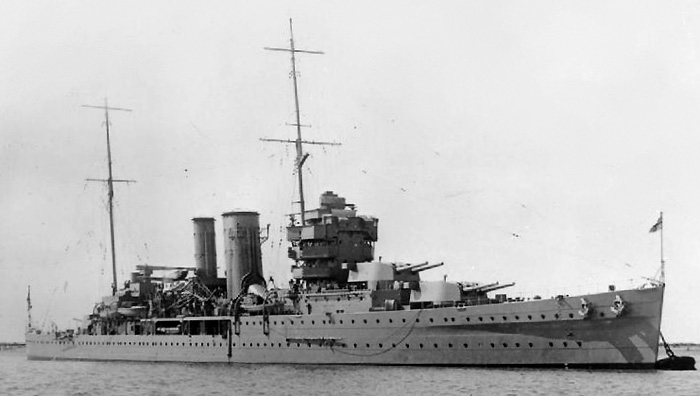

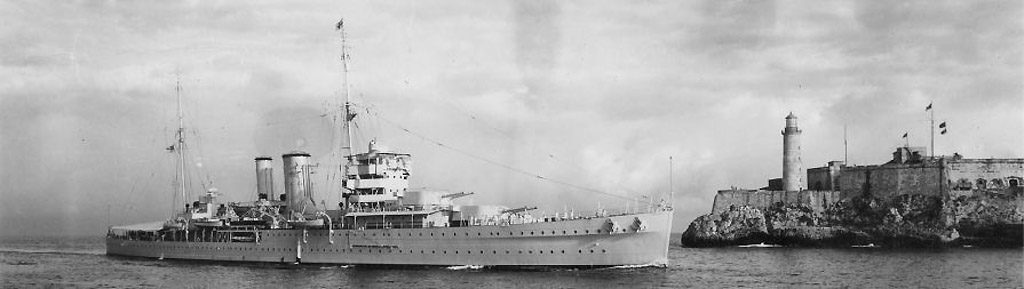

HMS York in 1930

The tonnage saved was about 4000 tons, traduced as real savings for the tax payer, however this weight savings also served to better concentrate and distribute the armor. The Exeter protection was in the end ultimately thicker and more effective, although still weak to face aircraft bombs as the York demonstrated later. Moreover, despite the limited size available, the engineers were able to cram into the compartments the same powerplant, four boilers in two boiler rooms, four Parsons geared turbines, for 80,000 shaft horsepower in total. As a result according to the weight saving, the design speed was 32.5 knots, faster than the County class by one knot. So in the end, with the loss of two main guns and some range, the York class was faster and better protected.

The reductions in cost were £250,000, compounded by a manpower reduced by 50.

The Exeter class design

The York was launched in 1928 and completed in 1930, followed by the Exeter in 1931.

The latter differed in having a hull wider by 2.5 cm. Normal hull size was 540 ft (160 m) between perpendiculars and 575 ft (175 m) o/a, and the ship was 57 ft (17 m) wide, and had a 17 ft (5.2 m) draught. Also the Exeter was 8,390 tons standard/10,410 tons full load, had a complement of 630 and her magazine box citadels was covered by 5–1 in thick plates. Her onboard aviation was better with two Fairey Seafox (later Supermarine Walrus), thanks to two fixed catapults. HMS York indeed had a single Fairey Seafox operated by a single rotating catapult. None had hangars.

The two ships were particularly set apart by their superstructures, totally different. The York had masts and funnels angled to the rear and a very tall bridge designed to clear the aircraft catapult planned to be placed on the original design on the “B” gun turret, installed in 1931 but later removed. In fact in Conway’s, both ships are treated as separated entries.

The class was however limited to that two ships, which were in essence, the last British heavy cruisers. The Surrey class, which derived from the Yorks, and reconciliated with the “eight-eight” battery, was never ordered (see below). All the next cruisers were light ones, according to London treaty limitations.

Paper projects: The Surrey class

The Surrey class was planned under the 1928-29 program for completion in 1932, but they were cancelled on 14.1.1930, right after the financial crisis and in parralel to the London naval treaty. Indeed, Great Britain was permitted 15 heavy cruisers with a total tonnage of 147,000, and had already reached her cota with the County class.

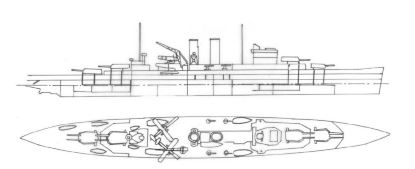

They were basically four turrets versions of the Exeter. They shared the same hull elongated from 175 to 183 m (575 to 600 feets) and the forecastle was continued to “X” turret, which used the upper superstructure deck as a superfiring position. They displaced in theory 10,000 tons standard still, for a planed 12.664 tons FL, and their armour was later judged totally inadequate. They would have been given a reduced machinery, four Parsons turbines fed by 6 admiralty 3-drums type boilers rated for 60,000 hp, enough for a design speed of 30 knots.

Protection-wise they were given a 5-1/2 in belt protecting the machinery spaces and extended 9 feets below the lower deck, 2-1/2 in thick on 1-1/2 in plating. Closing bulkheads were extended for a further 5 feets. 3 in protected the magazines, while the turrets, trucks, ring and bulkheads, steering gear, were 1 in thick. In addition to a secondary armament of four 4 in/45 QF Mk V HA, 16 Bofors ‘Pom-Pom’ (two octuble) and 8 TTs, they would have carried two seaplanes on rotatable catapults each side behind the funnel N°2. They would have been named HMS Northumberland (planned to be laid down at Devonport) and HMS Surrey (planned to be laid down at Portsmouth), but work on the design stopped on 23.8.1929.

A modified Surrey design at the end of the 1930s. The complete reconstruction of the London also give clues about the possible 1940s design.

Powerplant

Despite a redued macinery space, better proytected and compartimented, both Class B heavy cruisers had eight Admiralty 3-drum water-tube boilers feeding four shafts Parsons geared steam turbines for a total of 80,000 shp (59,700 kW). Top speed as designed was 32.25 knots down to 30.25 knots (56.02 km/h) fully loaded. Their range was 10,000 nmi (20,000 km) at 14 knots (26 km/h, helped by a provision of 1,900 tons of oil fuel.

Armament

The main armament comprised six 8-inch (203 mm) Mark VIII guns in three turrets rather than eight. These artillery pieces were mounted on Mark II mounts, which was designed to be 20 tons compared to the previous Mark I of the County-class but turned out to be heavier in the end. It however allowed a 80 degrees elevation, like the previous model. With special ammunitions, the York were indeed able to direct heavy anti-aircraft fire. This did not helped the York however against plungin Stukas. But mechanically this proved very complex by for little gain and a very rare use. On her side, HMS Exeter used a more conventional Mark II* mount with a 50 degrees elevation.

The secondary armament comprised four 4-inch (102 mm) QF Mark V guns, two AA 2-pounder guns and two triple banks with 21-inch (533 mm) torpedo tubes on each broadside, like for the County class.

The HMS York received in 1933 two additional Bofors 40 mm and several 20 mm Oerlikon guns in 1941. The Exeter was almost entirely rearmed after her duel with Graf Spee (see notes).

Protection

The A-class design cruisers may have been roomy and with a considerable range, they were “paper cruisers” in the sense of many areas were left totally unprotected and others were lightly armored. By contrast the York class included a 3-inch thick (76 mm) belt 8-foot-deep (2 m) high, plus an armoured lower deck linked to the top edge. The belt rose to 4 inches (100 mm) over the magazines, and extended above the belt with 2.5-inch (64 mm) crown.

The turrets faces and crowns were protected by 2-inch (51 mm) armour while the sides had 1.5 inches (38 mm). The barbettes below and ammo wells connected to the magazines and powder charges deep inside were 1-inch (25 mm) thick. The radio station was protected by 1-inch.

The belt was shorter, as the amidship magazine of the previous class was removed, and the space between turrets was largely reduced also. The armour scheme was in the end at least equivalent to the previous class but better over the machinery.

The York in action

Built at Palmers Shipbuilding & Iron Company, Jarrow, HMS York was laid don on 16 May 1927, launched 17 Feb 1928 and completed on 6 June 1930; She became flagship of the 2nd Cruiser Squadron until 1934 under captain Richard Bevan and the 8th Cruiser Squadron, North America and West Indies Station. In 1935 she sailed to the Mediterranean, patrolling during the second Italo-Abyssinian War, and in 1939 she was back on the American station.

Atlantic

Her first task was to escort a convoy from Halifax, Nova Scotia.

HMS York was assigned early in the hostilities to Force F at Halifax to hunt down the German raiders. She was refitted in Bermuda in October-November 1939 and returned in home waters. She entered the drydock for a refit from December to February 1940, and was back in action with the 1st Cruiser Squadron of Home Fleet. She intercepted the Arucas, a German blockade runner in the Skagerrak Strait in March 1940. The crew scuttled her before she could be captured.

She fought in Norway, escorting troop ships according to Plan R 4, and in April she towed to safety the badly damaged destroyer HMS Eclipse. She also escorted a convoy carrying the 1st Battalion of the Green Howards to Åndalsnes and Molde with HMS Manchester and HMS Birmingham, and later evacuated allied troops from Namsos in May 1940.

Battle of cape Passero

Then was sent mediterranean, arriving at Alexandria in late September with the 3rd Cruiser Squadron. After escorting a convoy around the Cape of Good Hope she was back to escort another convoy to Malta, one of the most dangerous route in the Mediterranean. She did not participated in the Battle of Cape Passero, but sank the disabled and abandoned destroyer Artigliere on 13 October, already badly hit by HMS Ajax the previous evening.

In November, York took part in Operation MB8, and Operation Judgement, the attack on Taranto which crippled the Italian fleet for the remainder of the war and inspired Pearl Harbor. She later returned to escort duties, ferrying trrops from Alexandria, Egypt to Piraeus, Greece. She again escorted reinforcements to Malta. She was part on a major sortie of the Mediterranean squadron from Alexandria on 16 December, which conducted air strikes on Italian shipping and airbases on Rhodes. She shelled Valona during this operation.

Battle of Crete

Operation Excess: In January 1941, York escorted a force bound to Suda Bay, Crete, and later covered operations in the Eastern Mediterranean. She escorted there a composite force, with the tanker RFA Brambleleaf and four Flower-class corvettes; She was back at Alexandria on 16 January, but returned in Suda bay in early February.

She was anchored in Suda bay (North of the ridge) for preying on Italian shipping an convoys. During the defense of the island on 26 March 1941, she was attacked by Flotilla Decima Flottiglia MAS commandos at night. The attack came from six Italian explosive motorboats of the MAT type. Each pair attacked a particular ship. One sent the tanker Pericles by the bottom. HMS York was hit amidships, flooding both boiler rooms and one engine room and killing two in the process. The cruiser was forced to ran aground to not sink competely.

While the bulk of her hull remaied out of the water her armament was not fully operational. Submarine HMS Rover was used as a makeshift dynamo to procure her electrical power, ensuring her AA batteries remained operational, whereas the Luftwaffe dominated the area.

It was the Luftwaffe indeed that took the task of finishing her off the following days. Raid after raid Stukas pounded the cruiser to oblivion, with 50 kgs to 500 kgs bombs. But where she was, the cruiser was still up but damaged well beyond repair. The British themselves, deciding the general evacuation, blew her remains up on May 22, 1941.

The Exeter in action

HMS Exeter off Solo coco, circa 1939

HMS Exeter was one of the most battle-harneded cruiser of the Royal Navy during world war two. She participated in three naval battles, in very difficult circumstances. On the first, she duelled (it’s right, with at first the help of two light cruisers) the Graf Spee, considered as a dangerous “pocket battleship” bearing six 280 mm cannons. A movie as made of this epic duel. On the second, against a whole squadron of IJN heavy cruisers during the two Battles of the Java Sea.

HMS Exeter anchored at Balboa harbor, 24 april 1934

The battle of Rio de la Plata

For his part, the Exeter, also in the Force H participated in the hunt for Graf Spee, accompanied by two light cruisers, and distinguished himself in the famous Battle of Rio de la Plata. Severely damaged, she struggled to Port Stanley for rough repairs, then the metropolis, where he remained in repairs and overhauled nearly 14 months.

Aftermath

She received in 1941 new tripod masts, rangefinders and firing telemeters, and a reinforced AA with eight 4 in/102 mm in double turrets, sixteen 40 mm Pompom in two octuples mounts, and a modernized mounts with more elevation for her main 8 in guns (203 mm). Thus parried, she quickly passed the Suez Canal to reach the Far East, and joined the Composite ABDA fleet under the command of Dutch Rear Admiral Karel Doorman, trying to oppose the Japanese. After the fall of Singapore, she joined Java, the last allied stronghold before Australia. She tried to oppose the passage of a convoy of 40 IJN ships of the invasion force, heavily guarded by four heavy cruisers and 15 destroyers. The challenge was to ward off the fall of java, potentially opening the doors of Australia.

First battle of the Java Sea

During the first battle of the Java Sea, the Japanese, whose morale was excellent, began an artillery duel while their destroyers approached for a massive torpedo attack. HMS Exeter received a 8 in shell from the Nachi in her engine room and was reduced to 16 knots, compromising the cohesion of the Allied force, ut she survived the onslaught. Two days later, she was again facing the Japanese heavy cruisers Nachi, Myoko, Ashigara and Haguro, each with four 8 in guns more than her. She endured a deluge of shells but was saved only by the resolute action of her escort, the destroyer HMS Electra. With the arrival of the night, the Dutch ships were sunk, and the HMS Exeter, badly damaged, forced to flee again, joining Surabaya.

Temporarily repaired, she tried to join with escorting destroyers the port of Ceylon. But the cruiser lacked sufficient repairs, and could only reach 23 knots. On March, 1st at dawn, she was spotted by Japanese aviation, and later caught by four Japanese cruisers. HMS Exeter and her escort, destroyers HMS Pope and Encounter, faced a new Japanese attack for two long hours before being destroyed along the destroyers. She capsized but refused to sink, and it was eventually decided to scuttle her. During these preparations, a Japonese destroyer approached and torpedo her at point-blank range. She exploded and sank, taking away the rest of her crew. Survivors were picked up by an enemy squadron and suffered the same terrible fate as the other British forces trapped in the Far East in death-riddled POW camps.

HMS York specifications |

|

| Dimensions | 175 m x 18 m x 5.2 m draught (full load). |

| Displacement | 8390 t. standard -10 410 t. Fully Loaded |

| Crew | 630 |

| Propulsion | 4 shafts Parsons turbines, 6 Admiralty boilers, 80,000 hp. |

| Speed | 32.5 knots, Range 10,000 nautical at 14 knots. |

| Range | |

| Armament | 6 x 203 mm (3×2), 8 x 102 mm MK VIII AA (4×2), 16 x 40 mm AA (2×8), 2 x 533 mm TTs, 8-10 x 20 mm oerlikon, 1 seaplane. |

| Armor | Belt 75 mm, turrets 60 mm, ammunition magazines and citadel 120 mm. |

Links/sources

http://www.naval-history.net/xGM-Chrono-06CA-York.htm

Conway’s all the world’s fighting ships 1922-1947

https://www.world-war.co.uk/profiles3.php3

https://uboat.net/allies/warships/ship/1187.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/York-class_cruiser

http://www.fr.naval-encyclopedia.com/2e-guerre-mondiale/royal-navy-2egm.php#crois

HMS Exeter in September 1939 during her duel with KMS Graf Spee (author’s illustration).

HMS York in Suda Bay, Crete, May 1941 (author’s illustration).

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign