Germany: SM U19, 20, 21, 22 (1912)

Germany: SM U19, 20, 21, 22 (1912)WW1 German U-Boats

Brandtaucher | Forelle | U-1 | U-2 | U-3 class | U-5 class | U-9 class | U-13 class | U-17 class | U-19 class | U-23 class | U-43 class | U-57 class | U-63 class | U-87 class | U-93 class | U-139 class | U-142 class | UA | UB-I class | UB-II class | UB-III class | UC-I class | UC-II class | UC-III | Deutschland | UE-I class | UE-II class | U-ProjectsThe U19-22 series were the first German U-Boat class fitted with diesel engines and other radical new improvements. They became a critical stepping stone in the development of world war one submarines, also also the first in German service fitted with 50 cm instead of 45cm torpedo tubes and with a 8.8 cm naval gun. Four boats were built in all in 1912, all surviving the war after many patrols and finding considerable success. U19 conducted 12 patrols, sinking 58 ships totalling 99,182 combined tons. U20 sank 37 ships for 145.830 GRT (+2 damaged) and infamously sunk the British ocean liner RMS Lusitania on 7 May 1915. U21 sank 36 merchant ships (79,005 GRT) and four warships (34,575 tons), damaged two more, sank two battleships and two cruisers (also changing the face of the Dardanelles campaign), and U22 sank 43 ships (46,521 tons), damaged three, captured 1. The U23, U27 and U31 classes, alternating from Germaniawerft and Dantzig NyD all derived from the U19 class, as the the last prewar submarines. They litterally made history.

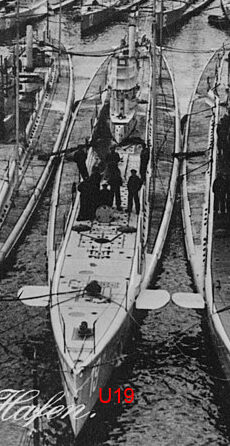

U22 underway

Early U-Boat at Kiel (Schleswig-Holstein) on 17 February 1914, so before the war. At the first rank, U 22, U 20, U 19, and U 21 (first row, left-right), then U 14, U 15, U 12, U 16, U 18, U-17 (U 13?) on the second row, left-right and then U-11, U-9, U-6, U-7, U-8 (U-5?) on the third row, left-right. Caption says: “Our submarine boats in the harbour” (in German).

Design of the U19 class:

Development

Probably one of the most imporant U-Boote class so far. To see the U-17 class, check the U-13 article, as U-17 was just an incremental step of the same by Dantzig NyD. In 1910 indeed, work on diesel engines had been going on for many years up to that point. The genesis of the U19 class was really to swap from gasoline engines to diesels, but the order was four gasoline engines for two diesels, which at this stage were much beefier and heavier. This imposed much changes in internal arrangements, recaclulations of the balance center and strenghtening the engine room.

The move towards diesel engines was a defining moment, that the general public always assoeciated even to this day, to classic German submarines. But unlike common assumptions, Germany was relatively late into placing diesels into submarines.

In the US Navy, the “E” class were the first with diesels (launched 1911), and the British from 1908 with the “D class” and the French from 1904 with “Z” (Rochefort). Each country devised its own models. In Britain it was Vickers, in France Sautter-Harlé. Imperial Russia, which first purchased German models, also jumped in the bandwagon with Minoga (launched 1908), but these early engines, (like for the US boats), were completely unreliable. Strangely, there was a pioneer of diesels in Germany, MAN (Maschinenfabrik Augsburg-Nürnberg), which provided its first units, not to the Kaiserliches Marine, but to rival Marine Nationale, as the 1907 Circé class adopted MAN diesels, so many years before the Germans did.

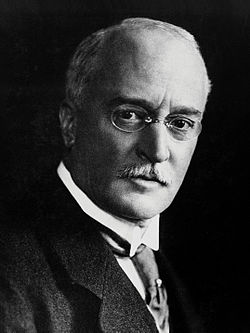

The idea of a diesel engine as an alternative to gasoline ones, dates back even before the automobile became widespread. Rudolf Christian Karl Diesel was born 18 March 1858 in Paris, France, from Bavarian immigrants living in Paris and young Rudolf Diesel work in his father’s workshop and was soon interested by technology and became a very good student, but with the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War his family were deported to London. Diesel attended an English-speaking school and wa slater sent to Augsburg to live with his aunt and uncle to become fluent in German and being taught mathematics, before joining the Technische Hochschule and later being awarded a merit scholarship from the Royal Bavarian Polytechnic of Munich, having Carl von Linde as mentor. Her worked as the Sulzer Brothers Machine Works in Winterthur, Switzerland, graduated in January 1880 with highest academic honours and returned to Paris to assist Linde creating a modern refrigeration and ice plant, becoming director a year afterwards.

The idea of a diesel engine as an alternative to gasoline ones, dates back even before the automobile became widespread. Rudolf Christian Karl Diesel was born 18 March 1858 in Paris, France, from Bavarian immigrants living in Paris and young Rudolf Diesel work in his father’s workshop and was soon interested by technology and became a very good student, but with the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War his family were deported to London. Diesel attended an English-speaking school and wa slater sent to Augsburg to live with his aunt and uncle to become fluent in German and being taught mathematics, before joining the Technische Hochschule and later being awarded a merit scholarship from the Royal Bavarian Polytechnic of Munich, having Carl von Linde as mentor. Her worked as the Sulzer Brothers Machine Works in Winterthur, Switzerland, graduated in January 1880 with highest academic honours and returned to Paris to assist Linde creating a modern refrigeration and ice plant, becoming director a year afterwards.

Long story short, years later, his thermal efficiency and fuel efficiency skills led him to build a steam engine using ammonia vapor, which almost killed him after exploding. His research into high-compression cylinder pressures lef home once more to the hospital but he soon conceptualised the idea of a diesel engine. His idea was to approach the maximum theoretical thermal efficiency of the Carnot cycle. In 1892 he patented his idea under DRP 67207 and by 1893, published a treatise on a new engine to replace the Steam Engine and Combustion Engines. He understood that 90% of the energy available in the fuel is wasted in a steam engine and instead outside ignition applied against internal air and fuel mixture he anted a system in which air was compressed internally within the cylinder whilst heating, with the fuel igniting on its own. This made for a smaller, lighter engine with a fuel efficiency 75% above the 10% theoretical efficiency for steam engines… From 1893 to 1897, Heinrich von Buz, director of Maschinenfabrik Augsburg, provided Rudolf Diesel the opportunity to test and develop his ideas with unlimited financing. Diesel latter received the same support from Krupp and managed to have Compression engines 30% more efficient over conventional gas burning engines and with higher internal temperature, higher rate, with greater pressure over the pistons, then quicker rate. These wouk also on biodiesel originating from waste cellulose gasification and extraction of lipids from algae, as alternative to classic fossil fuels.

The first successful diesel engine Motor 250/400 was officially tested in 1897 and rated at 25 hp. it was a 4-stroke, single vertical cylinder compression unit. It was first proposed to the manufacturing industry and became an instant success, royalties making Diesel a milionaire. Diesel obtained patents in most countries for his engine later, including in the United States. Between 1893 and 1897, MAN worked with Rudolf Diesel on this first prototype engine which showed a specific consumption of 324 g/kWh and produced 17.8 hp (13.1 kW) at 154 rpm. But it will take more years before MAN was able to present diesels suitable to be used on ships. The first marine diesel engines were built in 1903, however MS Selandia only became the first fully diesel-powered ship of note when she was launched in 1912. The French attempt in 1904 (Circé class) was not promising, as the very early MAN diesels were still unreliable, which is perhaps why Germany’s Dantzig yard waited so long to adopt the diesel, asking MAN for its latest, and hopefully now reliable units.

Based on these, the new U19 were ordered on 25 November 1910 at Kaiserliche Werft as so-called “double-hull” type, designed as an ocean-going submarines in the official documentation. The contract for their construction was awarded and U19 became the lead boat, laid down on 20 October 1911, launched on 10 October 1912, commissioned a year before the war on 6 July 1913 under Lieutenant Constantin Kolbe. Kaiserliche Werft wanted not only to improve on speed and range, but also on armament, making the submarine larger so to received 50 cm insted of 45 cm torpedo tubes, understanding the larger caliber would bring better results in combat.

Hull and general design

Apart de powerplants, the remainder of the design was pretty classic, just a slightly enlarged hull to fit in the large powerplants. These boats had the typical “double hull”, in reality comprising a central tubular pressure hull in the center, an upper, outer hull deck for the crew to walk on and do their daily tasks, a keel, and two large blisters blended to the pressure hull fore and aft, protecting it, and also topped by a flat section that complemented the deck, albeit in that case, efforts were made to better rounding that section for greater underwater performances and create less turbulences when diving or surfacing.

The U19 class was a bit larger than the U17 class, with a surfaced, light displacement of 650 t (640 long tons) and an underwater 837 t (824 long tons) submerged displacement. In overall lenght they were 64.15 m (210 ft 6 in) long (for memory this was the same as the Type VII of WW2), a beam of 6.10 m (20 ft) and a draught of 3.58 m (11 ft 9 in). Total height from the keel to the periscope fairings was 7.30 m (23 ft 11 in).

There was no fundamental change in the war the conning tower was made, there was still a tubular main section going down to the pressure hull below, also in which was placed a faired well contaning the attack and spotting periscopes. The conn. was preceded by a fore “step” section containing an emergency diving hatch, and larger, regular hatches places for and aft of the deck. There was a taller “step” aft of the conn. only there to add a platform and made a transition aft for better water flow when underwater. The CT generally had a small platform for a few officers and the helmsman standing behind a steering wheel at the front, covered with white canvas. There was also a portico supporting a protecting cable to go under nets, strapped fore and aft at the prow and stern.

The hull was divided into seven sections with only two main “independent” sections fore and aft on both sides of the CT, having concave heavy bulkheads. The forward one was the torpedo room with its two forward 50 cm tubes, mostly hosted in the outer hull. The pressure hull shapre her ended in a strenghtened narrow section. After of that “weak” internal hull section was the start of the first main “string” pressure hull section separated into two, with the crew quarters, magazines, gallery and then the officers’s quarters. Next was the CT and “central”, and the aft “strong” pressure hull followed, the engine compartment, also separated into two sub-sections, the diesel engines in the fore section and AEG electric engine in the aft section, and below a cigarette deck, the batteries which acted as permanent ballast underneath.

The aft section, outside the “strong” aft pressure machinery compartment, was the aft torpedo tibes room, also acting as crew’s accomodation room. The hull still was gently sloped up to the stem, straight as always, with anchors in recesses, and two pairs of diving planes forward, two close to the upper outer deck, and a pair below the waterline, roughly at the level of the aft diving planes near the poop. The rudder was hexagonal, not very low to avoid damage, articulated and protected by a heavy frame. Above were located the two short propeller shafts and their struts. The hull blisters hosted the ballasts and could be filled by three series of water scoops, forward, amidship and aft, near the end of the aft deck.

For communication, there were two telescopic masts fore and aft that can hold wireless radio cables. There was also enough room in the upper outer hull, above the presure hull, to store a number of items, notably buoyancy jackets (kapok type), and a dinghy for shore operations.

On paper, the sub had the means to have a small boarding party of a few sailors and one or two officers, all armed with pistols and rifles to inspect ships, as at this stage, these boats needed to obay recent submarine warfare conventions, which by default applied the “prize rules”, inspired by blockade running, contraband control rules. Thus, the subs needed to stop a ship at deck gun point, firing at the bow if necessary, call for a stop at the megaphone and order to prepare papers, sending the dinghy with the small boarding party, climb to the bridge and meet the captain and XO, control the papers, evacuate the crew of the ship was indeed listed as “hostile” by its nationality and content, and then dispose of the ship by various means, opening flooding cocks in the holds, or place scuttling (explosive) charges with a timer before evacuating. Courtesy of the seas applies, and the U-Boote captain generally indicated the cargo crew the nearest port or shore with a clear direction and compass or some food and other items if needed, but there was no room to take prisoners.

Powerplant

The U19 was powered as said above by a novelty, a pair of diesels. Mated on two 2 shafts were MAN 8-cylinder two stroke diesel motors rated for 1,700 PS (1,677 bhp; 1,250 kW). A small pipe was erected above the deck for the exhaust just like previous U-Boats using kerosone engines. This was complemented underwater by two AEG double modyn with 1,200 PS (1,184 shp; 883 kW) rated at 320 rpm. Top speed was a bit less than previous designs at 15.4 knots (28.5 km/h; 17.7 mph) surfaced, and 9.5 knots (17.6 km/h; 10.9 mph) when submerged, but the diesels were far more efficient and provided an unheard of range of 9,700 nmi (18,000 km; 11,200 mi) at 8 kn surfaced and the electric engines provided 80 nmi (150 km; 92 mi) at 5 knots when submerged.

Test depth wa the same as before, 50 m (164 ft 1 in). The move towards diesels of that later MAN type proved a bonanza ad by 1912 all teethibng problems had been solved, notably vibration issues. In service, they proved very reliable and never hampered operations while providing these U-Boats unbpreceddented “legs” to operated at the opposite of the British isles, on the western coast of Ireland as demonstrated by the sinking of Lusitania. MAN diesels became the norm but soon was introduced a 6-cylinder which was even more efficient while providing extra power to regain speed on the next classes.

Armament

The U13 were armed exactly like previous U13 boats and earlier, with six torpedoes carried internally, two bow and two stern tubes. Choice was made to adopt large tubes than change the layout notably at the bow to house four 45 cm tubes instead and store eight or more of these, which was an option on the table.

Torpedo Tubes

Germany started by equipping its torpedo boats and early U-Boats of the 1890s with the 35cm (14 in) C35/91 and C35/91GA, then 45cm (17.7 in) C45/91 Br, C45/91S, C/03 and C/03 D were reserved for surface ships, and the C/06 and C/06 D for U-Boats from U3 onwards. They stayed standard before tthe introduction of the 50 cm. The initial model was reserved for surface ships. This was the (19.7″) G/6 and G/6D whic used either the Decahydronaphthalene (Decalin) or Kerosene Wet-Heater. Before their replacement by the famous G7 (entering service in 1913), the U19 class was the first to introduce this model. U-Boats only used the G/6 apparently as the Kerosene powered G/6D was considered to “temperamental” for submarine use.

The G/6 was developed from 1908 and entered service in 1911. The Royal Navy was slower on this chapter, only introducing the 21″ (53.3 cm) Marks II, II* and II** for submarine use from 1914 onwards.

The four 500 mm (19.7 inches) torpedo tubes could be reloaded from above via the larger hatches going through the outer upper hull.

G/6 specs

Weight unknown, 236 in (6.000 m) lenght overall

Warhead 353 lbs. (160 kg) TNT/Hexanitrodiphenylamin (Hexanite) mixture

Range/Speed 2,410 yards (2,200 m) at 35knots or 5,470 yards (5,000 m) at 27 knots

Power: Decahydronaphthalene (Decalin) Wet-Heater

More on navweaps

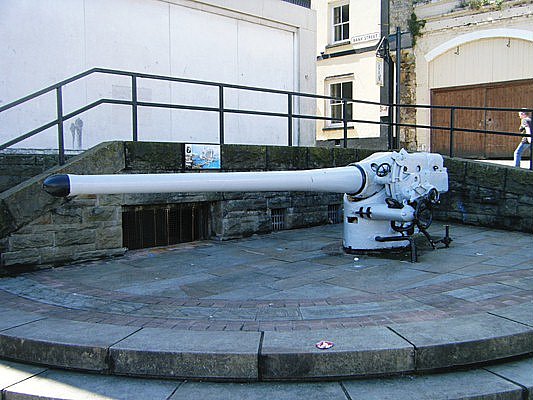

8.8 cm Schnelladekanone Länge 30 naval deck gun

This was another leap forward. After the classic 3,7 cm or in some case, replacement by an equally puny 5cm deck gun, this new class was estimated to be stable enough to have a larger gun installed. But at first, as designed, they had no deck gun but a 7.9 mm/79 Maxim machine gun mounted on a pintle when surfaced. The idea was to have it for boarding support only. Ships were torpedoed though the usual prize rule and surface actions against ships were deterred.

However by late 1914 as the war progressed rapidly, this was changed as U-Boats captains asked vehemently for a deck gun. As a result, all four boats either in November-December 1914 for U21 and U22 or Jan-Feb. 1915 for U19 and U20 their machine gun replaced by a single 88mm 27 caliber TK L/30 C/08 deck gun forward. For this the deck was reinforced but no sponsons extensions appeared seemingly on photos.

In 1916, after captains reported this gun still weak, notably to scuttle a boarded ship or engage an armed trawler. They spent way too much time sinking their prey, which called for enemy reinforcements. Thus, all four boats had a second 8,8 cm deck gun installed aft, making two. This made the U19 the first U-Boat class with two guns, fore and aft. At least this gave the crews a fighting change when surfaced. Apart U19 which exchanged both guns for a single 10.5 cm deck gun, U22 lost one in 1917, the other two (U20, 21) kept both guns until 1918. They accounted for many of their preys. The 8.8 cm became the standard go-to gun for all U-Boats built afterwards, until the U87 class (launched 1916), generally two for oceanic boats, one for minelayers and for later coastal subs.

The 8.8 cm SK L/30 gun used the Krupp horizontal sliding block, or “wedge” and the submarine deck version was on either a retractable or fixed pivot mount. The Krupp mount retracted vertically through a hatch, and the Erhardt version folded down onto the ship’s deck. They avoided underwater drag and turbulences. It seems U19 class had the Ubts.L of the second type.

The 8.8 cm SK L/30 was a widely used naval gun on World War I pre-dreadnoughts, cruisers, coastal defence ships, avisos, submarines and torpedo boats in both casemates and turrets as well.

This caliber became so ubiquitous in the German Navy it was still a favorite for WW2 U-Boats as well starting with the Type VII. Read more

Specs 8.8 cm SK L/30 on Ubts.L mount

Weight: 644 kilograms (1,420 lb)

Overall length: 2.64 meters (8 ft 8 in).

Breech: Krupp horizontal sliding block

Shell: fixed 7 kg (15 lb) cal 88 mm (3.5 in)

Elevation: -10° to +30°

Rate of fire: 15 RPM

Muzzle velocity: 590 m/s (1,900 ft/s)

Maximum firing range: 7,3 km (8,000 yd) at 20° or 10,5 km (11,480 yards) at 30°

10.5 cm SK L/45 naval gun (1917, U19 only)

In 1917, U19 only had her two 8,8cm deck guns replaced by a single 105mm deck gun with 300 rounds. Her crew rose to 35 men, still with four officers, albeit one was now a gunnery officer.

Built by Meddinghaus it was designed specially for deck use, low, with many sensible elements protected from corrosion.

Specs 10.5 cm SK L/45

1,450 kg (3,200 lb), 4.725 m (15 ft 6.0 in), 6.8 mm (0.27 in) wide.

Shell 10.5 cm (4.1 in) 25.5 kg (56 lb) fixed Brass Casing 17.4 kg (38 lb)

Breech: Horizontal sliding-block, MPL C/06: -10° to +30° mount

Rate of fire: 15 RPM

Muzzle velocity 710 m/s (2,300 ft/s)

Effective range 12,700 m (41,700 ft) at 30°

⚙ U17 specifications |

|

| Displacement | 650 t surfaced, 837 t submerged |

| Dimensions | 64.15 x 6.10 x 3.58m (210 ft 6 in x 20 ft x 11 ft 9 in) |

| Height | 7.30 m (23 ft 11 in) |

| Propulsion | 2 shafts MAN 8-cyl. diesel 1,700 PS +2 × AEG dm 1,200 PS |

| Speed | 15.4 knots surfaced, 9.5 knots submerged |

| Range | 9,700 nmi at 8 kn surfaced, 80 nmi at 5 kn submerged |

| Armament | 4× 50cm TTs (2 bow, 2 stern, 6 torpedoes), 3.7 cm (2 in) SK L/40 gun (1914) |

| Max depth | 50 m (160 ft) |

| Crew | 4 officers + 31 men |

Career of the U19 class

U19

U19

U19 was ordered in 1910, laid down at Kaiserliche Werft Danzig in 1911, launched on 10.10.1912 and completed in july 1913 with Oberleutnant zur See Constantin Kolbe in command since july 1912 until 15 March 1916. From 1 August 1914, the latter date Constantin Kolbe had the unfortunate distinction of becoming the first U-boat casualty of World War I, when his boat was rammed by HMS Badger on 24 October 1914. Her hull was badly damaged, but she survived and was repaired, albeit Kolbe was wounded.

U19 was ordered in 1910, laid down at Kaiserliche Werft Danzig in 1911, launched on 10.10.1912 and completed in july 1913 with Oberleutnant zur See Constantin Kolbe in command since july 1912 until 15 March 1916. From 1 August 1914, the latter date Constantin Kolbe had the unfortunate distinction of becoming the first U-boat casualty of World War I, when his boat was rammed by HMS Badger on 24 October 1914. Her hull was badly damaged, but she survived and was repaired, albeit Kolbe was wounded.

He was replaced by Kapitänleutnant Raimund Weisbach until 10 August 1916. On 22 January 1915, she was spotted by the steamer Durward (1.301 GRT) near the Maas lightship, which had a hard to time escape the U-Boat at 12 knots. Durward’s second was later interviewed by the Daily Mail in Rotterdam about his brief exchange by megaphone with the XO of U19, which spoke excellent English. The later ordered them to lower a boat and come to talk, given ten minutes to leave the ship. The commander of the U-boat towed the lifeboat to within 100 yards of the Maas lightship and there, crew of Durward said goodby, and rowed to the lightship, to await for rescue hosted at least in a safer place.

Raimund Weisbach, was the former torpedo officer on U-20 and had served under Kapitänleutnant Walther Schwieger, the man that infamously sank RMS Lusitania. During his brief command, Weisbach carried out an unusual mission: He delivered the Irish revolutionary Roger Casement and two other agents to Banna Strand, Ireland in hopes to stir an uprising and distract British forces.

Weisbach was relieved on 11 August 1916 by Johannes Spiess, relieved in turn on 1 June 1917 by Heinrich Koch and then Hans Albrecht Liebeskind, who commanded for less than a month before being relieved on 17 November 1917, by Spiess again. On 1 June 1918, Liebeskind retook command until the end of the war.

Overall, U-19 conducted 12 patrols and sank 58 ships for a total of 99,182 combined tons, including Santa Maria (5,383 GRT) off Lough Swilly on 25 February 1918 as well as Tiberia (4,880 GRT) off Black Head, near Larne, on 26 February 1918, and HMS Calgarian (12,515 GRT) off Rathlin Island on 1 March 1918 as its biggest “kills”.

On 11 November 1918, U-19 was surrendered to the British, which scrapped her at at Blyth in 1919 or 1920. Her main gun was donated to the people of Bangor (still today at Ward Park) by the Admiralty in recognition of the native Commander The Hon. Edward Bingham of HMS Nestor famous for the Battle of Jutland for which he received the Victoria Cross.

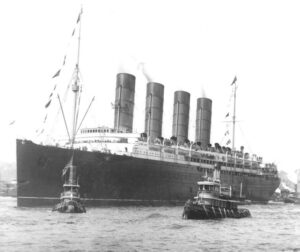

U20

U20

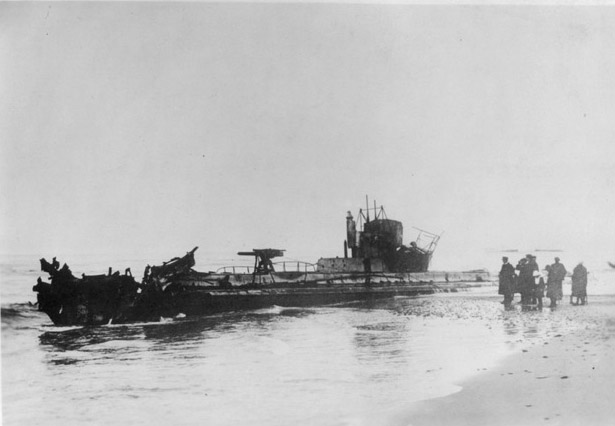

U20 stranded, grounded on the Danish coast in 1916. Torpedoes had been setup to explode in the bow in order to scuttle her.

U20 was ordered in 1910 to Kaiserliche Werft Danzig a a Cost of 2,450,000 Goldmark in 14, laid down on 7 November 1911, launched on 18 December 1912 and commissioned on 5 August 1913. Her first commander was Oberleutnant zur See Otto Dröscher until 15 December 1914.

On 7 May 1915 under Kapitänleutnant Wilhelm Otto Walther Schwieger (until 4 November 1916), U-20 was patrolling off the southern coast of Ireland. On 30 January the same day she claimed the steamer Oriole (1.489 GRT) and Tokomaru (6.084 GRT). On 4 February, a U-boat blockade around the British Isles was established with an official declaration that any vessel in it, was now a legitimate target that can be sunk without warning. Later she sank the steamer Bengrove (3.840 BRT) on 7 March 1915, Princess Victoria (1.108 BRT) two days later, Florazan (4.658 BRT) on 11 March, and both Centurion (5.945 BRT) and Candidate (5.858 BRT) on 6 May.

At about 13:40 the following day (7 May), Schwieger saw in his periscope and approaching vessel, making at 700 m (770 yd) a silhouette with four funnels and two masts, making her a passenger liner. Long story short, he believed she carried ammunitions (which was true) and fired a torpedo that passed to the starboard side almost directly below the bridge. Schwieger wrote later he was surprised by the size of the explosion, reasoning that a second explosion must have happened due to coal dust, boiler, or black powder.

At about 13:40 the following day (7 May), Schwieger saw in his periscope and approaching vessel, making at 700 m (770 yd) a silhouette with four funnels and two masts, making her a passenger liner. Long story short, he believed she carried ammunitions (which was true) and fired a torpedo that passed to the starboard side almost directly below the bridge. Schwieger wrote later he was surprised by the size of the explosion, reasoning that a second explosion must have happened due to coal dust, boiler, or black powder.

Only by closing on her he realized he torpedoed Lusitania of the British Fleet Reserve. The mighty liner sank very fast, in 18 minutes, and with 1,197 casualties. This was one of the most pivotal historical moment in naval history for its consequences. Even Before Schwieger got back to Wilhelmshaven for refuelling and supplies, the United States formally protested and at first Kaiser Wilhelm II was infuriated by the tone of the American note but in June, he was compelled to rescind unrestricted submarine warfare and banned any action against passenger liners. On 4 September 1915, Schwieger was back at sea and sailed 85 nmi (157 km; 98 mi) off the Fastnet Rock, south Irish Sea on his patrol line, but this area had treacherous rocky shoals.

Soon she spotted and sank the Horse transport Anglo-Californian (7,333 GRT), shelled in company of with U-38 on July 4. A few days later on the 9th this was the steamer Ellesmere (1,170 GRT) and the same day the Finnish steamer Leo (2,224 GRT), then the British steamer Meadowfield (2,750 GRT) an the following day, the Finnish sailing ship Marion Lightbody (2,242 GRT) on July 10, then the Russian steamer Lennok (1,142 GRT) on the 13th, . He went back to resupply and was back to the same area, and on 2 September sank the British steamer “Rumania” (2,599 GRT), Danish steamer Frode (1,875 GRT) a day later, and was critized again by the high command for having torpedoed the passenger steamer RMS Hesperian (10,920 GRT) on 4 September.

Next, on the 5th, this was U20’s “biggest tally” of the war, when she sank in succession the British steamer Dictator (4,116 GRT) and Douro (1,604 GRT) as well as the Finnish steamer Rhea (1,145 GRT). The followed day rhis was the French steamer Guatemala (5,913 GRT) and a day later, Bordeaux (4,825 GRT) and British steamer Caroni (2,652 GRT). The 8th, he had his last victim, the British steamer Mora (3,047 GRT), sunk on 8 September 1915. Back home the submarine went into drydock and sailors went back to their familiies for Xmas.

Back in action in April, U20 sank the Spanish freighter Bakio (1.906 BRT) on the 30th, British Ruabon (2.004 BRT) on 2. May, she gunned down the French sailing ship Marie Molinos (1.946 BRT) a day later, then the sailing vessel Galgate (2.356 BRT), on 6 May, and two days later the large passenger ship Cymric (13.370 BRT) on 8 May. Back to port to rsupply and R&R for the crew, she went back in action for the summer campaign, starting with the steamer Aaro (2.603 BRT) on 1st August, the steamer Thelma (1.002 BRT) on 26 September. But targets were few and far between. Most went now under the convoy system. Back in action for a last round, she sank the Ethel Duncan (2,510 GRT) on 18. October, French steamer Arromanches (1.640 BRT) on the 23th and Italian Chieri (4.400 BRT) the same day.

However when closing on the coast on 4 November 1916, she grounded on the Danish coast, south of Vrist, north of Thorsminde, after her diesels broke down and strong currents that drive her to the shore. Her crew attempted to scuttle her with the torpedoe’s explosives but only managed to blast her bow. She remained there until 1925 when the Danish government blew her up and removed the deck gun, kept in the naval stores at Holmen, Copenhagen for 80 years. The conning tower was exhibited at the front lawn of the local museum Strandingsmuseum St. George Thorsminde, still there.

U21

U21

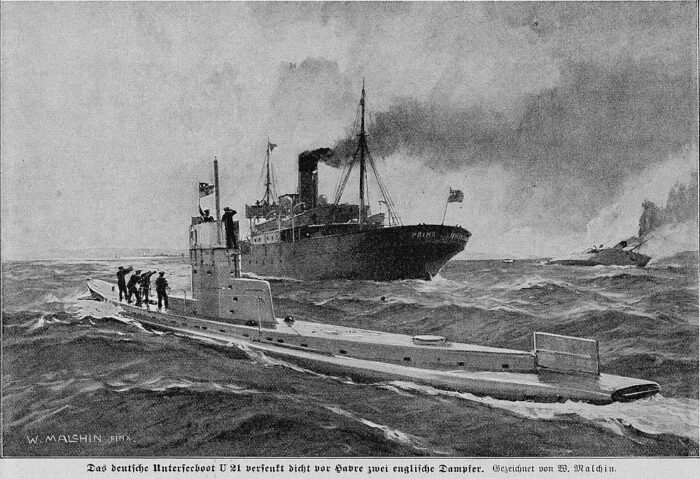

Wilhelm Malchin, 1919: German U-Boat U21 sinks two British steamships 1915

U-21 was built at the Kaiserliche Werft (Imperial Shipyard) in Danzig (now Gdańsk, Poland), laid down in 27 October 1911, launched on 8 February 1913. After fitting-out work completed, she was commissioned on 22 October 1913 with Oberleutnant zur See Otto Hersing in command, practically unil the end of the war in April 1918. In August 1914, U-21 was based at Heligoland an sailed for a patrol into the Dover Straits. On 14 August for her second patrol with U-19 and U-22, she sailed to the northern North Sea between Norway and Scotland. They spotted a cruiser and a destroyer off the Norwegian coast but fail to sink both. Hersing also attempted to enter the Firth of Forth but was unsuccessful, between nets, patrols and currents.

On 5 September, she crossed the path of the scout cruiser HMS Pathfinder off the Isle of May when surfaced to reload his batteries. She submerged to make an attack, but Pathfinder turned away so he broke off the chase, resumed reload of his batteries.

Shortly thereafter, Pathfinder reversed course again and headed back toward U-21, Hersing manoeuvering into an attack position, firing a single torpedo that hit her aft of her conning tower, detonating one of the forward magazines, and she vanished in a massive explosion. For what still floated afterwards, only a single lifeboat could be lowered before she sank. Other survivors were found clinging to torpedo boats that rushed to the scene. Pathfinder was the first warship sunk by a modern submarine, before the sinking of three armoured cruiser. 261 sailors went down with her. She sank the French steamer SS Malachite on 14 November under classic prize rules, foring her to stop, sending a boat, inspect the cargo manifest, and ordered the crew to abandon ship, after which she was sunk by deck gun. Next she did the same for the British collier SS Primo.

On 22 January, she sailed to the Dover Barrag and Irish Sea, where U21 shelled the airfield on Walney Island until being turned back by a coastal battery. A week later she sank the collier SS Ben Cruachan with scuttling charges (prize rules too) and on 30 January 1915, SS Linda Blanche and SS Kilcuan. She had to pass back the Dover Barrage to Wilhelmshaven.

In April 1915, U-21 was transferred to the Mediterranean to support Turkey, leaving Kiel on 25 April, to Austria-Hungary in eighteen days after a long detour north around Scotland to avoid the Dover patrols, rendezvoused with the supply ship SS Marzala off Cape Finisterre to refuel. However this was poor quality oil and had to complete the journey with half her fuel supply remaining, forced to remained surfaces to conserve fuel but managing to evade British and French torpedo boats and transport ships.

She made it at snail pace in Cattaro on 13 May, with justy 1.8 t (1.8 long tons) of fuel remaining out of 56 t initially. She spent a week at Pola and Cattaro in mid-May, viisted here by U-Boat commander Georg von Trapp and was sent to assist in the Gallipoli campign with U-33, U-34, U-35, and U-39.

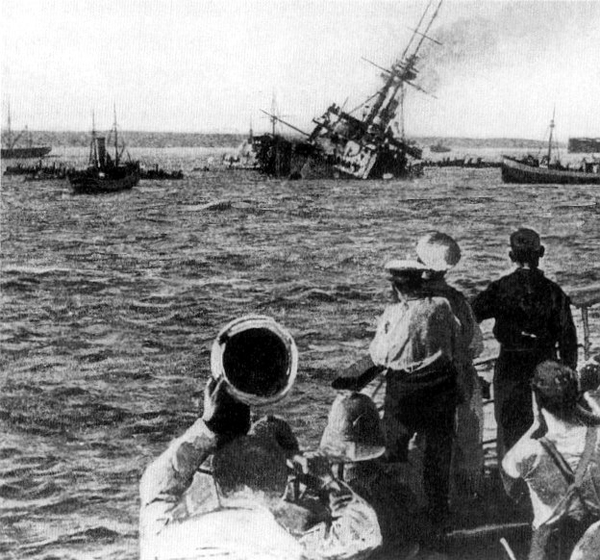

She arrived on her operational area off Gallipoli on 25 May and soon spotted HMS Triumph. She close to 300 yards (270 m) and fired a single torpedo which hit her, and the flooding was soon uncontrollable. But she had to evade many destroyers hunting her. After 24h down the bottom waiting, she surfaced to reload batteries and bring in fresh air. On 27 May, just two days later she spotted and sank her second battleship, HMS Majestic. This time, she was protected by torpedo nets and several small ships around, but Hersing aim at a weak point in the defences. Majestic sank in four minutes. The result was all the Ottomans wished for: All Allied capital ships were withdrawn.

She arrived on her operational area off Gallipoli on 25 May and soon spotted HMS Triumph. She close to 300 yards (270 m) and fired a single torpedo which hit her, and the flooding was soon uncontrollable. But she had to evade many destroyers hunting her. After 24h down the bottom waiting, she surfaced to reload batteries and bring in fresh air. On 27 May, just two days later she spotted and sank her second battleship, HMS Majestic. This time, she was protected by torpedo nets and several small ships around, but Hersing aim at a weak point in the defences. Majestic sank in four minutes. The result was all the Ottomans wished for: All Allied capital ships were withdrawn.

Majestic listing after being hit by a single torpedo from U21. Devoid of any modern torpedo protection or even flooding mitigation, these ships were “easy pickings”.

The crew of U-21 was later back home awarded the Iron Cross by Kaiser Wilhelm II and commander Hersing the “Pour le Mérite” (“blue max”). She refuelled at a Turkish port before crossing the Dardanelles to Constantinople and while transiting, nearly pulled into a whirlpoo. As the newspapers related about the exploits, the crew already had a taste of massive welcoming ceremony attended by Enver Pasha. The maintenance took a month, so the crew enyoyed their shore leave. U-21 sortied through the Dardanelles, spottd and torpeedoed the French munitions ship Carthage. Later she was potted by an allied trawler, foring a crash-dive to escape ramming, but blundering into a minefield. One mine exploded off her stern without significant damage so she could come back to Constantinople.

She then operated on the Black Sea with UB-14 as part of the newly formed Black Sea Flotilla. In September she returned for a patrol in the eastern Mediterranean, but could not pass the complete blockade of the Dardanelles with mines and nets erectec in between. Unable to return to Constantinople, she sailed to Cattaro. To circumvent the fast Germany was not at war with Germany yeat, she operated under the Austro-Hungarian flag as “U-36” until 27 August 1916.

On 1 February 1916, she sank the British steamer SS Belle of France and added another large warship to her already impresive tally, as she torpedoed and sank the French armoured cruiser Amiral Charner (photo), off the Syrian coast, disappearing with 427 men. In early 1916, while off Sicily she spotted the Q-ship and auxiliary cruiser. She surfaced, fired a shot across her bow, but as the latter refused to stop, started firing and close to sink her when she revealed her heavy armament. Wounded by shell splinters, Hersing withdrew in the conn and ordered to launch a smoke screen before submerging.

On 1 February 1916, she sank the British steamer SS Belle of France and added another large warship to her already impresive tally, as she torpedoed and sank the French armoured cruiser Amiral Charner (photo), off the Syrian coast, disappearing with 427 men. In early 1916, while off Sicily she spotted the Q-ship and auxiliary cruiser. She surfaced, fired a shot across her bow, but as the latter refused to stop, started firing and close to sink her when she revealed her heavy armament. Wounded by shell splinters, Hersing withdrew in the conn and ordered to launch a smoke screen before submerging.

On 30 April, she sank the British steamer City of Lucknow and three small Italian sailing vessels off Corsica on 26-28 October. On 31 October she sank the 5,838 grt Glenlogan. Next she sank the Italian steamships Bernardo Canale and Torero and samll sailing vessels off Sicily. On 23 December she damaged the steamer SS Benalder, east of Crete.

By early 1917 she was recalled to Germany and sent in unrestricted warfare, sinking en route two British sailing vessels off Porto (16 February) and two Portuguese on the 17th. On the 20th she sank the French steamer Cacique in the Bay of Biscay and on the 22th in the Western Approaches, she sank the Dutch steamer Bandoeng, already damaged by UC-5 and still the same day, sank or damaged seven more ships, Dutch (Eemland, Gaasterland, Jacatra, Noorderdijk, Zaandijk, Menado) and Norwegian Normanna. For her first north sea patrol since the start of the war, by late April, she successively sank the Norwegian Giskö, Theodore William (22 April) Askepot (29th) Russian Borrowdale (30th) and Lindisfarne (3 May), then the British steamers Adansi and Killarney (6 and 8 May) and Swedish “Balti” on 27 June.

She also attacked a convoy of 15 merchants escorted by 14 destroyers in August SW of Ireland but had to fleet a 5-hour hunt. Hersing later changed tactics to deal with escorted convoys, establishing it was better to close as much as possible before firing torpedoes and dive under the transport ships as destroyers would fear to use depth charges so close to the transports. That tactice was sitll used as standard in WW2. Later in 1918 he left command to Kapitänleutnant Bruno Krumhaar when U21 was assigned to the III U-boat Flotilla. Later under Kapitänleutnant Hans Scabell, Paul Schwerdtfeger and Friedrich Klein she was used as a training boat for new crews, survived the war. On 22 February 1919 while under tow to Britain as war reparation she accidentally sank in the North Sea. In all, she sank 113,580 gross register tons (GRT), damaged two ships for 8,918 gross register tons (GRT), and with two battleships and two cruisers held a wartime record, never equalled even in WW2.

U22

U22

Ordered on 25 November 1910 like her sisters, U22 was laid down at Kaiserliche Werft Danzig, Yard 16 on 14 November 1911, launched on 6 March 1913 and commissioned on 25 November under command of Kapitänleutnant Bruno Hoppe. In her career of 14 patrols, she sank 43 ships for a total of 46,521 tons, damaged three more for 8,988 tons, and captured one prize worth 1,170 tons.

On 21 January 1915 she spotteda periscope, fired on what she believed to ba British submarine, but later it appeared to be SM. U-7. This was one of the high profile friendly fire at that stage of the war, leading to new recoignition procedure to avoid this to happen ever again.

On 21 April she sank the Swedish Ruth (867t)a dn a day later the British St. Lawrence (196t). Back on patorl this summer, she sank on 15 June the British steamer Strathnairn (4,336t) and cpaster Trafford (215t) the following day as well as gamaing the Turnwell (4,264 grt). On 20 June she sank the “Premier” (169t). On 8 August 1915 she sank her first auxiliary warship, the liner HMS India (7,911t). On the 15th, this was the british Grodno (1,955 grt). After a maintenance overhaul and rest for the crew this winter, she was back in action in the spring 1916. In 6 April she nearly sank the british Vennacher (4,700 grt), ùanaged to limp back for repairs. Two days later she sank the Adamton (2,304 grt) and on 13 April the British steamer “Chic” (3,037 grt). For her newt summer patrol her sole “kill” was on 21 June the French steamer Francoise D’amboise (1,973 grt).

Next she had a new captain, Oberleutnant zur See Karl Scherb from 23 August until 31 May 1917n this time transferred to the Baltic flotilla. Scherb performed most of his kills in a single winter patrol: On 2 November 1916 she sank the Russian Vanadis (384 grt) and the same day day captured the Swedish Runhild (1,170 grt) as prize. The following day she sank in sucession the Swedish Ägir (427 grt), Frans (134t) and Jönköping (82t) partly by gunfire. on 8 November she sank the Russian Taimi (114t) and on the 11th the Swedish steamer “Astrid” (191t)

Given the meagre result it was decided to send her back to the north sea theater, operating from Kiel, and under a new captain.

Oblt.z.S. Hashagen was indeed her most successful of her wartime captains (from 1st June 1917 to the armistice of November 1918) sinking 28 vessels, the largest being the British passenger steamer “SS California” (5,629 tons) 145 nautical miles (269 km; 167 mi) of Cape Villano on 17 October 1917.

But she also sank on 7 August the Swedish Jarl (1,643 grt) as her last patrol in the Baltic. On 11 October she sank the british Elve (899 grt), on 16 October the US steamer Jennie E. Righter (647 grt) and a day later the British California. On the 19th she Austrlian “Australdale” (4,379 grt) and Norwegian Staro (1,805 grt) and a day later the Snetinden (2,859 grt). The year ended with a maintenance overhaul and well earned R&R for the crew at Xmas. She was back in operation in January. On 6 January 1918 she sank the French coaster Saint Mathieu (175t). Her next patrol she only sank on 2 March the Swedish Stina (1,136 grt). May was her most profitable month due to her new hunting area in the Baltic. On 11 May she sank the Russian Michail and on 12 May the Norwegian Kong Raud, Tennes, Vea, on 14 May 1918 the Stairs and on the 16th Mthe Polarstrommen, Russian Fedor Tschishoff and another never identified vessel. On 19 May she sank the Norwegian Forsok and a day later the Russian Hertha.

She was back for a Bay of Biscay summer campaign, sinking on 19 August the Italian Buoni Amici, Portuguese Magalhaes Lima (20th) and Maria Luiza (22th), Norte (31st). On 1st September, Libertador and on 4 September the Santa Maria, Villa Franca, Lloyd and gun damaged the Prateado.

U-22 survived the war, and was surrendered to the Allies at Harwich on 1 December 1918, in accordance with the Armistice terms with Germany, sold for BU to Hughes Bolckow on 3 March 1919, completed in 1922.

Read More/Src

Books

Johannes Spieß: Sechs Jahre U-Bootfahrten. R. Hobbing, Berlin 1925.

Johannes Spieß: U-Boot-Abenteuer. 6 Jahre U-Boot-Fahrten. Verlag Tradition Kolk, Berlin 1932 Kriegsabenteuer eines U-Boot-Offiziers. Berlin 1938.

Bodo Herzog, Günter Schomaekers: Ritter der Tiefe, graue Wölfe. Die erfolgreichsten U-Bootkommandanten der Welt. 2.

Gröner, Erich; Jung, Dieter; Maass, Martin (1991). U-boats and Mine Warfare Vessels. German Warships 1815–1945. Vol. 2. Conway Maritime Press.

Rössler, Eberhard (1985). The German Submarines and Their Shipyards: Submarine Construction Until the End of the First World War. Bernard & Graefe.

Werner von Langsdorff: U-Boote am Feind. 45 deutsche U-Boot-Fahrer erzählen. Bertelsmann, Gütersloh 1937.

Carl Ludwig Panknin: Unterseeboot „U. 3“. Verlagshaus für Volksliteratur und Kunst, Berlin 1911

Unterseeboot „U. 9“. Schiffe Menschen Schicksale.

Bodo Herzog: Deutsche U-Boote 1906–1966. Erlangen: Karl Müller Verlag, 1993

Eberhard Möller/Werner Brack: Enzyklopädie deutscher U-Boote Von 1904 bis zur Gegenwart, Motorbuch Verlag, Stuttgart 2002

Ulf Kaack: Die deutschen U-Boote Die komplette Geschichte, GeraMond Verlag GmbH, München 2020

Robert Hutchinson: Kampf unter Wasser – Unterseeboote von 1776 bis heute, Motorbuch Verlag, Stuttgart 2006

Links

on uboat.net/ U19

on navypedia.org/ u19

en.wikipedia.org SM_U-19 (Germany)

on de.wikipedia.org/ U_19 U-Boot 1913

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign