Introduction

For once, we left the guns to rest, and turn the bar back in time, with one of the most glorious page of sail: A long tradition that still is revered around the world, maintained by naval schools and living museums: The magnificent Tall ships and the invention of trading race: The great clippers are unleashed !

This was before steam definitively ruled the seas, when it was still dirty, noisy and unreliable, sometimes bordering to dangerous.

The oceanic nobility of the time were wooden cathedrals of sail, champions of rival trade companies that made the headlines, turned the heads and drew unapologetic cheers. The prize ? The freshest tea from India up to London’s docks…

Captains, ship-owner and architects raised as the superstars of their day, empires betting their fortune on the finest pure-breeds, with names carried with pride as an invitation to compete, fine lines, fiery temper, daring prows ready to cut the seas and break records. But clippers were also a way to revolutionize naval architecture, by searching for -empirically- the best hull shape and water lines.

They influenced naval construction to this day, also allowing frigates to be faster and mixed vessels to reach good speeds while under sail, often a viable alternative to mediocre or dangerous early steam powerplants. From 1869 and the opening of the Suez canal, clippers demand fell whereas the first composite vessels appeared, soon to be replaced by 1880s iron-hulled ships.

And when this ended, it went on with human cargo, immigrants to the US and South America or Australia. Here, from 1820 to 1870 follows the harrowing legends of half-century sailing at its very best, with the British, American and Australian clippers that made history. Follow us in that adventure !

History of clippers

The term itself was controversial. “Clipper” could either be likened to “to clip”, cut, cross quickly, or get close to an marine slang term for the “pinnacle” of its field, a thoroughbred of the seas as it was also associated with race horses. It was influenced by Dryden, the English poet that first used it to describe the swift flight of a falcon in the 17th century.

Origins (1770)

Still, Clippers had common characteristics, including a generous sailing area, elongated hull with fine shapes at both ends. In short, and at the very moment when the steamers might dethrone them, the Clippers represented an effective alternative, albeit subject to the vagaries of the weather, but much more efficient, increasing delivery speed as more important as the payload capacity.

The sailing clippers were therefore justified for carrying goods with high added value, and the buyers were ready to pay premiums and colossal fees to the first stocks arrived. Hence the highly competitive nature of these “trading regattas”. The British and the Americans held the highest position during those years from 1820 to 1860. The other Europeans followed, and the big four-master or five-master square or schooners iron ships succeeded them until the 1930s.

Alan Villiers describe the opinion of most sailors as being “sharp-lined, built for speed (…) tall-sparred and carrying the utmost spread of canvas”. Added to very fine lines that went against carrying capacity, the ships had skysails and moonrakers on the masts plus studding sails on booms and extra manpower. The true first clippers has been the topsail schooners developed in the Chesapeake Bay right before the American Revolution, which took a prominent part in the war of 1812. Their early inspirations has been French luggers operating in the Caribbean. After this war, American clippers started to link with China and India, bearing some resemblance to the small and sharp-bowed British “opium clippers” in the 1830s. “Baltimore clippers” continued to be built, this time for American companies willing to engage in the China opium trade until 1849 when it was no longer profitable.

The early clippers (1830)

The first post-Baltimore ship, also considered as the first proper “clipper” was an enlarge model called Ann McKim, built in 1833 at Kennard & Williamson shipyard, displacing 494 tons OM, with a sharply raked stem, counter stern and square rig. She is frequently assimilated as the “first clipper” but appeared at a time ships were still bulky and was its own breed, but her influence can’t be denied.

Ann McKim, the first proper modern clipper for most authors, model and hull lines.

Not to be undone, old Europe made a clipper, through Scottish yard Alexander Hall and Sons, innovating with a new kind of prow, soon to be called “Aberdeen clipper bow”. This first “Aberdeen clipper” was the Scottish Maid (1839). She displaced 150 tons OM only, but built to compete against steamers on the lucrative Aberdeen-London trade. Since the distance was short she did not need to be taller. Her hull was the work of passionate designers, the Hall brothers, which tested multiple hulls shape in a water tank. 1836 tonnage regulations were also taken in account. In effect, Extra length above this level was tax-free, which motivated greatly the construction of more Clippers. These first European clippers were indeed those trading between the British Isles.

The 1840s saw the gradual appearance of much larger clippers, tailored to carry from the far east tea, opium, spices and other precious goods. Larger, they were to went through notoriously difficult cape of good hope without too much harm and then race through the Indian ocean. In the USA the first of these was the Akbar (1839), 650 tons OM, followed by the Houqua (1844), 581 tons OM, for tea. Opium clippers were generally smaller, such as the Ariel (1842) 100 tons OM.

Extreme clippers (1845)

The New Yorker 1845 Rainbow, 757 tons OM is now seen widely as the first “extreme clipper”: Large hull with very fine lines, lost of sail area. The Rainbow was really sacrificing cargo capacity for speed. More on the detail below.

William-j. Popham painting, clipper rainbow

Extreme Clippers would flourish between 1845 and 1855, before changes of regulations and more reliable steamers among others made them less profitable. Already there were concerned in 1850 these ships were too uncompromising and costly, therefore Medford, in Massachusetts, launched what is often compared as the first “medium clipper”, the Antelope of Boston (1851). It was a compromise, combining large stowage capacity with yet still good sailing qualities. They certainly made more profit on payload on less expensive goods which freshness was not an issue. This new breed ultimately replaced extreme clippers. Companies still kept some more for the prestige and as a flagship than to make profit as per se. By 1856, none was built anymore. Their shine lasted for just ten years but they will certainly raised the clipper as a genre, as far as possible by using sailing power. No ship that fast and with that tonnage was ever built afterwards.

The golden age of clippers (1850-60)

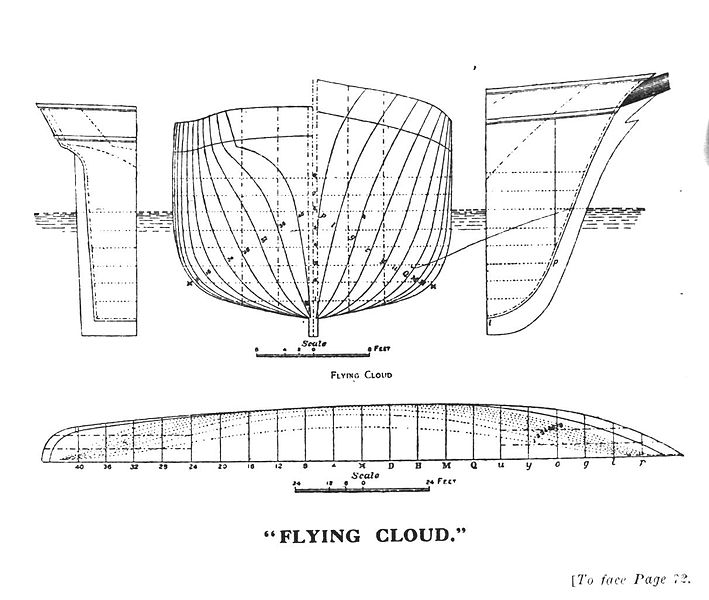

Medium Clippers were still impressive by their own right nevertheless. One yard in particular will rose to international fame: Canadian-born designer and builder Donald McKay. The Flying Cloud made headlines by linking New York to San Francisco in 89 days 8 hours, through the dreaded cape horn. Not only she became famous by being the fastest of all clippers, but for her race with the Hornet in 1853, and by being commanded by a female skipper, Eleanor Creesy. The Flying cloud will also link with Australia and took part in the timber trade in the far east. McKay would built almost a hundred clippers from 1840 to 1875.

Medium Clippers were still impressive by their own right nevertheless. One yard in particular will rose to international fame: Canadian-born designer and builder Donald McKay. The Flying Cloud made headlines by linking New York to San Francisco in 89 days 8 hours, through the dreaded cape horn. Not only she became famous by being the fastest of all clippers, but for her race with the Hornet in 1853, and by being commanded by a female skipper, Eleanor Creesy. The Flying cloud will also link with Australia and took part in the timber trade in the far east. McKay would built almost a hundred clippers from 1840 to 1875.

British Revenge

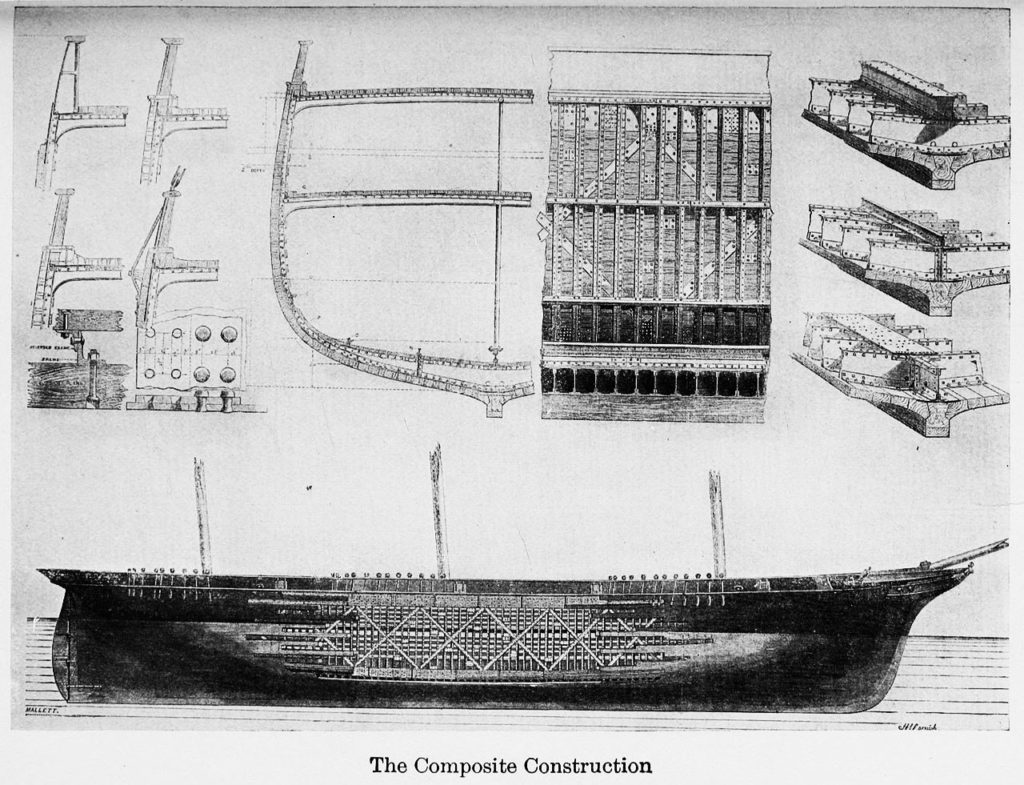

From 1859 a brand new British clipper appeared, in total contrast with the American ships. From 1859 were still extreme clippers, with a sleek, graceful appearance and lower sheer and freeboard, as bulwarks and narrower. They were the supreme athletes of the seas, and nothing was too fine to win the ultimate race of the time: On the China tea trade route. The first of these was aptly named the Falcon, that year of 1859. The last of these great China clippers (a name taken back for a famous seaboat of the 1930s) appeared in 1870 ad a year prior, the Suez canal was open. Only 25 to 30 of these clippers were launched at a rate of around four each year worldwide. The 1860s vessels, first generations, were of course all wooden but iron construction slowly but surely was making its way, heavier, but making the ships much stronger. In fact as the world’s leading industrial power, UK already built a flew ships in iron prior to 1859. Like frigates they were called “composites”. By 1863 the first composite tea clipper had iron spars inside its wooden hull plus copper sheathing for anti-fouling.

One of the last of these late 1860s Tea/Opium composite clippers was the Dumbarton-built Cutty Sark. The fall of this activity was gradual. First, the Emperor of China forbid importation of European goods and imposed payment in silver for tea. This was circumvented by the East India Company which produced and introduced Opium on the Chinese Market, with tremendous effect in the population, hence the Imperial ban and subsequent two opium wars. Apart Opium and tea, gradually passenger transport was thought just as profitable as wealthier gents opted for adventure and exoticism by embarking at any price on these majestic tall ships.

The Flying cloud, with studding sails and handkerchiefs up – Painting by Jack Spurling

One such vessel converted to passengers and mail was the City of Adelaide, designed by William Pile of Sunderland (1864). But fast clippers carrying precious goods rarely exceeded 20 years of service. They were either worn out of progress made them obsolete. Apart some exploits like the Challenger carrying almost her own construction price with her tightly packed tea and precious silks load, Clippers were least and least profitable. The Australian City of Adelaide is the second and only surviving Clipper.

Californian Clippers

The most prestigious and prolific Clipper builders and operators were the West Coast Yards. The great incentive was the 1848 gold rush. Americans but even Europeans flocked to California to try their luck. Rather than crossing a still untamed wild west by land, they preferred the faster route by sea, via the Cape Horn. Impoverished New Yorkers or Easterners in general despite the ticket high price, bet their own existence on this trip west. Californian clippers were therefore built to rally San Francisco to New York in record times, in four month, and gradually down to 90 days as the Clippers became better and better.

Of course the speed was showcased as an argument as tickets prices flamed up in some cases. In all, until 1855, some 144 clippers were built on the West coast. The champion became the Flying cloud, holding a record with 89 days. But in the 1860s extreme clippers left their place to medium clippers. McKay’s thoroughbred had a length-to-beam ratio of 6/1, which was much narrower than the usual 5/1. The Cloud measured 73 meter on the waterline, she was one of the largest. But the record holder of the largest clipper ever built went to the Great Republic, a 1853 McKay prestige vessel, displacing 4500 GRT for 400 ft (122 m) over all length.

Captains usually cheated by not allowing to reduced sail, even in heavy weather. They only reduced it when crossing the Cape Horn. However these ships on average rarely made more than 6-8 knots on the long run. Despite of this, Clippers, after disembarking passengers in San Francisco often went south, taking the eastern route to Asia and loading previous loads in Shanghai and other port, then sailing to Europe via the Good Hope Cape, and then back to the USA with more migrants. In two or three trips, the ship more than made up for the expenses of its construction and maintenance.

Outstanding and unmatched performances for trade ships

Due to their prolific sailing area, the great tea Clippers of the 1860s were the pinnacle of the genre, the fastest sailing trade ships ever built, up to over 16 knots (30 km/h) when the winds were favourable an the sea calm enough. 1900s iron-built windjammers sometimes approached those speeds, but only modern yachts beat them in terms of pure speed. By judging statistics of port-to-port liaisons, American clippers seemed at the top of this game and rule supreme. Donald McKay’s Sovereign of the Seas reached the unheard of, and record-holding speed of 22 knots (41 kph) on her way to Australia.

Even the best competitors of the the Great Tea Race of 1866 never approached that speed. Ten US-built Clippers raised to the hall of fame in terms of sustained speed over long distances. The Champion of the Seas for example once managed an astounding 465-nautical-mile (861 km) run in a single day (which held up until 1984). It was not uncommon for US-built Clippers to cover more than 700 km daily, on entire weeks. This of course was also linked to the skills of seasoned, brave and aggressive captains, showing outstanding feats of seamanship, flair and probably also luck. Clippers were also very safe, fortunately for their precious load. Their unmatched speed prevented them to be caught up and captured by pirates. Nothing was as fast, even oversailed cutters.

Back to the tea race, this year saw three clippers from rival companies competing: The Ariel, Teaping and Serica. The first to win earned an extra bonus of one pound per ton of precious cargo, the other down to 10 shilling. The 1863 Teaping was a 985 GRT composite clipper, and avid competitor of the tea races and in general this far east route until 1871, when the trade vanished. The Thermopylae and Cutty Sark were also other famous duellists, making the headlines. In 1866 the Taeping won by only 12 minutes over the Ariel, and only because the captain chose the more risky trip south. He took the risk, like many captains after him, to catch and hold as long as possible the dreaded Roaring Forties. This was the autobahn of the seas.

The Rainbow at sea. Difficult seas made ships rocking and rolling, decreasing dramatically the top speed they could achieve. By knowing the local peculiarities of winds and reading weather, Captains were often able to take the optimal courses.

The fall of clippers (1870)

In the end, as the tea trade was no longer profitable, 1870s Clippers were used to carry passengers, migrants to the USA or between coasts and to Australia, notably for the wool trade. For long sea voyages, they were free of any space taken by coal of machines and thus carried more goods for the same size. A few routes were profitable, notably Boston to San Francisco, and to Australia, motivating Australia to built a few clipper in turn. The other traditional European shipbuilders also produced some fine clippers, notably in France and the Netherlands.

The Panic of 1857 started the downslide for Clippers. The disruption of the Secession war for international trade also, and gradual restrictions of trade in China, plus the rapidly moving nature of markets trades. In 1869, the opening of the Suez Canal made their fast trip round Africa useless and steamers, slower but more regular, were just better at making profit on the new route to the far east. A new breed appeared, the steam clippers, which fired their boilers and lowered their removable screw propeller each time the wind died. The weight and size of the steam engines and associated coal made these ships slightly bulkier and with less capacity, but this was compensated by their regularity on the long run.

Some were also reconverted as had hoc frigates, like those of the American Civil War (mounting cannon, carronades, used for piracy, privateering, smuggling, or as blockade runners).

‘Free Trade’ – One of the 2300+ advertising sailing cards were produced, highly praised by collectioners today.

Clippers were not completely extinct after 1870s though. Composite steam clippers, arguably much slower but carrying more due to their stronger ans larger hull, proved more profitable. Soon, the rule of windjammers, three four and even five barque and schooners replaced he wooden wonders of the 1860s. In 1914, the numbers of sailing ships was still very impressive. U-Boat warfare soon condemned the tall ships trade which emerged depleted from the war. The last of these great ships slowly vanished in the interwar, such as the Preussen. Perhaps the last war action by a clipper was from the memorable Seeadler (1888), which proved that old school sailing privateers could be just as effective. As of today only one great classic clipper of the golden age survived: The Cutty Sark. Unfortunately despite such a rich history, no American clipper has survived.

Composite construction of clippers

Other countries

Australian Clippers

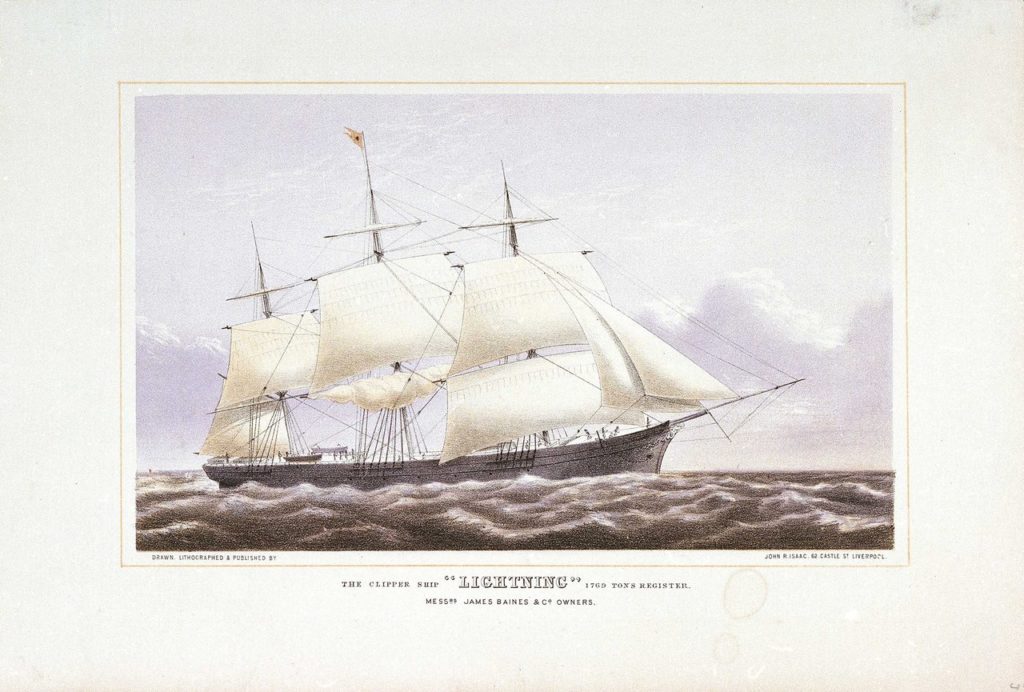

The record-beater Australian clipper Lightning of 1854

The 1851 gold rush in Australia motivated the construction of clippers. They were built in the USA, notably at the Californian McKay yards and many others, paid and exploited by British and Australian companies. They used the western winds, from Europe to the east, via the cape of good hope, reached Australia and came back loaded with Asian goods through the pacific south and the same winds via the cape Horn to Europe. The first was the composite clipper Marco Polo (1853), of 1622 GRT made in Canada. The same year, the British yard Robert Scott & Co delivered in 1853 at Greenock the Lord of the Isles, entirely in iron. She made London-Shanghai in 98 days, showing it was possible for an iron clipper to do just as good as wooden ones. She won the tea race of 1856. With a 7/1 ratio she often rolled badly in heavy weather so much so sailors nicknamed her the diving bell.

The most famous Australian clipper of that era was the James Baines (1850). Californian-built made Liverpool-Melbourne on a regular basis and her first crossing in 63 days. The Baines was launched on 25 July 1853 from the East Boston shipyard of Donald McKay yard, for the Black Ball Line (James Baines & Co.) of Liverpool. She reached the record-breaking speed of 21 knots in 1856 and under Captain C. McConnell made Boston-Liverpool in 12 days, 6 hours.

Learn your sails ! – 1850s Extreme Clippers’s rigging plan.

But soon she was beaten back by the Lightning, made by the same yard for the same company. Carrying wool to UK, she made the trip in 63 days and less hours, the world record. Her sail area was greater, with a mainmast reaching 50 m above the deck, 29 m wide for her largest sail, and 49 m wide with the addition of studding sails. She also made a record 24 hours run at 18.2 knots on average, over 432 nautical miles topping at 21 knots in several occasions. On the Australian line, thanks to the roaring 40, Australian Clippers had no competitors, especially packet boats and heavier medium mixed clippers. They stat active in the 1880s even after the opening of the Suez canal, which only shortened their trip for 900 miles, whereas the 4600 miles between Europe and Australia used western winds to best effect. Australian clippers therefore were the last in use anywhere in world, up to the 1890s. Of course, composite or iron-built clippers became the norm.

French Clippers

Called “Havrais” (Form the Havre, main French sailing trade port), or “Cap-Hornier” (in reference to Cape Horn), the French Clipper era preceded the tall ship traders, generally built in iron and then steel up to 1914. France has one of the finest clippers that roamed the seas, although their story is seldom known in the Anglo-Saxon world, to the point the very term “French clipper” equates a big interrogation point. We will try there to correct that issue.

Development of French Clippers was slower and later, mostly due to the lack of prospect for such trades. Only by seizing the colonial Empire of Indochina in the 1880s the French could deploy their own long range trading networks, taking advantage of classic Clippers. But by that time they were already composites and many had steam engines. North African colonies on the other hand did not required anything else than steamers, from 1830.

1870-90s: The French iron tall ships era.

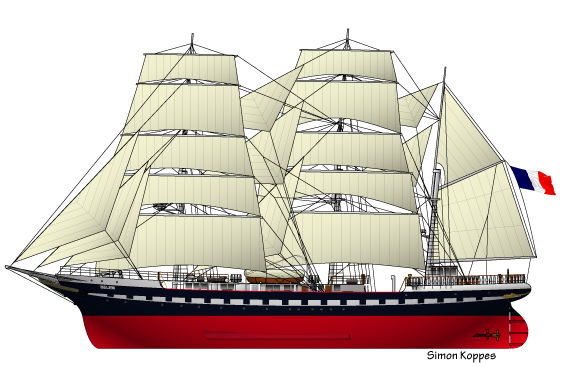

France, then far behind its partners in terms merchant tonnage (9th rank), implemented a resolute policy for promoting sail, by offering bonuses to yards, as their total absence of coal consumption made them interesting for carrying particular goods. Companies (called in French “armements”) such as Bordes, in Nantes, which launched in 30 years some 230 iron tall ships, specialized in carrying coal and cereals from the United States and nitrates from Chile. Of course the war of 1914 would cripple this fleet. Such sailing vessels were easy pickings, easy to spot and slow enough to be catch by a submarine and destroyed by gunfire. Nowadays France has a single of these medium iron clipper preserved for us to see, the 1890s nitrate carrier called the Belem, a familiar sight in tall ships events around the globe.

The Belem (1896), by Simon Koppes (cc)

Brazilian Clippers

Brazilian Clippers were used to transport coffee, sugar, and other goods from Brazil to Europe and North America. These exports were crucial to Brazil’s economy, especially during the 19th century when coffee became a dominant export.

Like other clippers, Brazilian clippers were characterized by their narrow hulls, large sail areas, and tall masts, designed to maximize speed and wooden construction but with composite hulls in the 1880s. They were built for long voyages and fast travel, which was crucial for perishable goods like coffee.

Brazil’s involvement in clipper trade routes was part of the broader global maritime economy. Clippers often stopped in Brazilian ports like Rio de Janeiro, Santos, and Salvador, contributing to the flow of goods and cultural exchange.

Dutch Clippers

An example:

The Kosmopoliet I, launched on 29 November, 1854 by Cornelis Gips and Sons (Dordrecht) for Gebr. Blussé of Dordrecht. She has been inspired by a medium-clipper model of 1852 showcased at an exhibition in Amsterdam by the Dutch lieutenant-commander M.H. Jansen. She carried both cargo and passengers, fully rigged with royals and skysails on three masts. On the line Netherlands-Java she made the trip in 89 days and later in 76, 74 and 77 days, whereas the normal trip would be 100 days and more.

American Clippers

Baltimore Clippers (1812)

Author’s illustration of the Pride of Baltimore, a replica of an east coast privateer, blockade runner clipper. All the following profiles are also from the author.

These fast coasters mainly built at Baltimore from the 1770s were designed for trade around the thirteen colonies and the Caribbean Islands. They played their part in the independence, scouting for the insurgents, and were very fast thanks to their “V”-shaped cross-section below the waterline, strongly raked stem and masts. They could have been originated not from the east coast but from the Bermuda sloop, made for open ocean. The fact they were very fast and made for speed whereas used for trade with the full knowledge that time was money made them the first clippers.

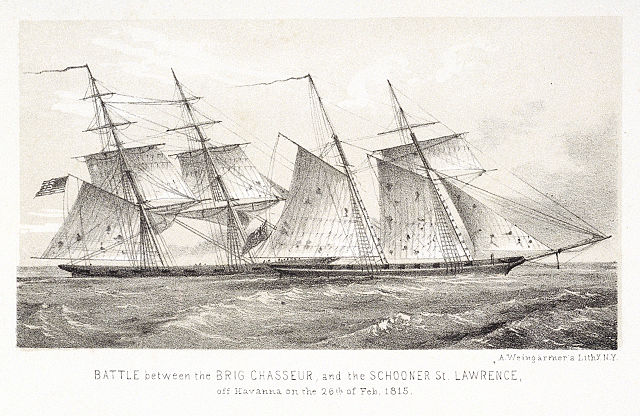

During the 1812 war, Baltimore clippers rose to fame. There was yet a very young USN (13 october 1775), and alongside the famous “super frigates” of the USS Constitution class, Baltimore and other ports could offer privateers using Clippers. They were given letters of marque but traded, used as blockade runners, and many were captured by the British.

In addition many new such vessels were developed specifically for war: They were larger and faster yet heavily armed. Such ships were the Chasseur, Prince de Neufchatel and General Armstrong. Like battlecruisers they were designed to catch up any ships or skirmish with larger ones. Prince duelled with the much larger HMS Endymion, while Chasseur captured more vessels than the entire USN. The Royal Navy appreciated these clippers and used them after the war to chase off slave ships.

Rainbow (1845): The first “extreme clipper”

The Rainbow was in its time the fastest sailboat. It was built in New York on the plans of J.W. Griffith and officially held for a 750-ton barrel. She had most of the characteristics of clippers of his time, including concave or hollowed lines forward, a clear innovation at that time, now mainstream in ship construction.

The Rainbow with her magnificent and immense sailing area earned indeed the title of “first extreme clipper” awarded to the first real ship of this type, and the fastest, but it disappeared without a trace in 1848. The famous “America’s Cup” appeared just when this trade competition between England and the USA was at its highest. Both for long were the only cup participants, prolonging a long tradition.

Flying Cloud (1851): The fastest American clipper

The Flying Cloud was a tall ship and clipper, rigged as a three-masted barque in service from 1851 to 1874 under the US and British flags. She was known for her role in the gold rush and colonization of Australia, and transporting migrant to California via Cape Horn or to America from Europe.

One of the most famous clippers she was known first for her exceptional speed between New York and San Francisco, nailing one record at 89 days and 21 hours in 1851, and 1854 in 89 days 13 hours. The record stands until… 1989. She was Built at the McKay yard, East Boston, for Enoch Train (Train & Co) for $50,000, and repurchased, still on the slipway for $90,000 by Henry Walton Grinnell (Grinnell, Minturn & Co). One of the very first clippers designed by Donald McKay she was inspired by John Willis Griffiths designs and borrowed a lot from his previous Stage Hound, yet better streamlined overall.

Overall lenght: 235 US feet (71.6 m), 12.7 m (41.8 US feet) wide, 6.55 m (21.6 US feet) draft (2.5 m below beam). Displ. 1782 tons, 60 m (196 ft) mainmast tall over deck, figurehead showing a white and gold angel. Launched on April 15, 1851, she inspired a poem by Henry Longfellow.

Her first career (Capt. John Perkins Creesy and his wife, navigator Eleanor Creesy) was carrying candidates for the gold rush, on June 2, 1851 plus perishable foodstuffs, from New York to August 31, 1851 in San Francisco, in 89 days 21 hours despite storms and Cape Horn crossing, the doldrums, some damage along the way and an unruly crew. On July 31, she reached 18 knots and Eleanor Creesy calculated and average of 15 knots on 374 miles/24 hours.

In 1853 she made another run in 105 days and later broke its own record on New York-San Francisco. From 1862, she sailed for James Baines & Co. with the Black Ball Line and by April 1871, resold to Harry Smith Edwards, South Shields. From Liverpool, she transported migrants to Australia. She was lost on June 19, 1874, loaded with cast iron, running aground, breaking in two off Saint-Jean (New Brunswick). Her cargo was sold and salvaged in 1874 but the wreck was burned.

Challenger (1851)

The Challenge is without a doubt the most beautiful and the fastest, the biggest clipper ever built in the USA. It was built at G.H. Webb yards in New York City in an effort to dethrone the mythical Flying Cloud, which was no small feat. The latter was considered unbeatable, and his record was already five years when the Challenge went to sea.

His owner, N.L. and G. Griswold, had him baptized during the greatest launching ceremony ever seen in New York. Huge, moving 2006 empty barrels, 70 meters long, its very solid hull had iron struts and was 51 cm wide at the waterline, the challenge was also the first to have three decks.

The apple of his great mast was 70 meters high, and the shape of his hull was the thinnest ever seen. Its black hull was embellished with a fine golden band, and ended with an eagle with spread wings, also gilded. Its interior fittings were extremely refined for a merchant ship, a “freighter” with current standards, with two accommodations for officers, another large room and an antechamber, 6 luxurious cabins in rosewood, panelled with carvings oak raised fine gilding.

The Challenge was designed for trade between California and China. It could also carry wealthy passengers. There was great hope in him and for his first crossing, it was entrusted to a celebrity of the time, Captain Robert H. Waterman, known to be the fastest on this road.

Her first trip would take him from New York to San Francisco, through Cape Horn, and Waterman was promised a $ 10,000 bonus if she could complete the course in 90 days. She made it in 108. For if the ship was sublime, her crew, force-picked up in the port, consisted mainly of false sailors and unreliable rabble attracted mainly by California gold. Thus, off Rio there was a mutiny, and the second was killed.

Officers promptly re-established order by harsh discipline and the journey continued in a heavy atmosphere. At Cape Horn, three sailors fell from the mizzen yard and died, and later, dysentery carried off 4 others. But on her first trip to China, Captain Land replaced Waterman, considered too tough, together with a better crew.

Challenge broke the record for a return trip in 34 days, but captain Land died on board. Pitts replaced him and made further trips. Rallying with Great Britain’s Wamphoa Tea, he set a new record in 105 days. The British admired the ship so much during her stay in UK her hull lines were carefully drawn for the admiralty.

In 1861 the proud ship was worn out. She was sold in Bombay as Golden City, and travelled between India and Hong Kong, then she sailed in 1866 for Wilson and Co. of Britain between Bombay and Java. At the Cape of Good Hope, a rogue wave swept over the back and carried off all her officers. She often ended her travels with part of her rig absent, as well as her crew.

The beautiful clipper was perhaps too finely made, fragile with a high rigging making her unstable and thus dangerous. She ended her career by hitting the reefs of Ouessant, Britanny, and sank despite the help of a French gunboat in 1876.

Chariot of Fame (1853)

The Chariot of Fame was a three-masted, square-rigged “medium clipper” type ship, built at East Boston in Massachusetts, by famous shipbuilder Donald McKay, for Enoch Train & Co., Boston’s White Diamond packet line (Boston-Liverpool). She was launched in April 1853. She srarted as a packet vessel before being chartered by the Australian branch of the White Star Line (Australian packets) running to Australia from England 1854-1855 then by In 1862, she was sold on london, made new voyages to Australia-New Zealand and left Queenstown on 7 October 1863 for Auckland 8 January 1864 with 520 British colonial troops to deal with the Maori insurrection. She made another run to Lyttelton on 29 January 1863 with 430 Government immigrants, 30 passengers. The Chariot of Fame was reported “abandoned at sea” in January 1876 while between the Chincha Islands and Cork. Ref. Disp. 1693 tonnes, Dimensions 220 feet × 43 feet × 27 feet 6 inches.

British Clippers

Thermopylae (1850)

The Thermopylae is certainly less known than the Cutty Sark, but she was nevertheless one of the key legends of the Clippers’ time; It’s actually her who holds the record for the fastest tea clipper in the world, winning the Golden Rooster, breaking all established records, and motivating the owner of the rival company arming the Cutty Sark to build another clipper. These two ships made headlines because their ferocious regattas were popular.

Cutty Sark (1850)

(To come…)

Ariel (1865)

Ariel, better clipper of the Tea route.

Ariel was one of the first British composite clippers to be the only A-Clipper. She was built to serve the London-Foochow route to China at a time when the tea trade gave rise to ferocious regattas. She was commissioned by Shaw, Lowther, Maxton & Co from London to Robert Steele & Greenock’s yards. Her hull was composite, with steel framing and a teak deck. Her sails was innovative with the addition of an extra square stages, up to five levels.

She measured 197.4 feet between perpendiculars (hull only), and approximately 60.16 meters long overall by 10.33 meters wide for 853 net tons in the register, carrying more than 1060 gross. 100 tons of steel ballast were added to the hull, to perfect her stability and to compensate for her higher mast height (meaning taking more wind).

In October 1865, she was launched for her first major crossing to China (Gravesend-Hong Kong) and returned, under the command of Captain Keay, in 79 days and 21 hours pilot to pilot, or 83 anchorage, which was already a nice feat. and the following year, in 1866, he participated in the great tea race with other famous shearers, Tapping, Fiery Cross and Taitsing. She was famous for his very short loss to Taeping, who arrived 20 minutes before her on London’s waterfront.

…To be continued

Read More/Src

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Clipper_route

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Clipper

http://www.navistory.com/navires-ere-industrielle.php

http://www.baltimoreindustrytours.com/shipbuilding.php

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_clipper_ships

//fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cap-hornier

//fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chantiers_de_la_Loire

//fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C3%89tablissements_Ballande

//fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Armement_Bordes

Videos Docs

Why conserve the Cutty Sark? – Richard Doughty

‘Cutty Sark & The Great Clippers’ / Nautical Engineering Documentary

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign

Looking for information on clipper ship PIDGEON. Supposedly an anchor from this ship was recovered from San Francisco Bay off Yerba Buena Island in November 1964 by the Freighter Robin Kirk. It is believed to have been lost by the PIDGEON. Cannot find anything on either ship on Internet, but someone else researching said that the PIDGEON was never in that location. Appreciate any information.

Hello Joyce, if you count on Google for that, good luck. What you need is a dictionary of clippers, if ever this book exists. I have some books about XIXth ships, but they are not listing all clippers, far from it, only shining examples. The lists of Lloyd Registers would certainly help too: https://hec.lrfoundation.org.uk/archive-library/lloyds-register-of-ships-online. If you find infos about this ship, could you publish some info here please ? Thanks !

Here is a 1852 newspaper article of the Pidgeon Clipper. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn86053954/1852-03-04/ed-1/seq-2/#date1=1770&index=1&rows=20&words=clipper+Pidgeon&searchType=basic&sequence=0&state=&date2=1963&proxtext=Pidgeon+clipper&y=0&x=0&dateFilterType=yearRange&page=1

Thanks for the reference !

Greetings from NewZealand

A very interesting site indeed.

I have spent some time transcribing the diaries of my great grandfather who was the Steward on Eagle Wing under Captain Linnell

He wrote not lines but pages of commentary every day at sea.

Gripping reading indeed.

Extraordinary social commentary as well as of course the daily sailing events.

Most interesting are his recordings of ships they sighted at sea, date times and bearings. I suspect some were last sightings.

Are there other Eagle Wing researchers out there?

Thank You Helen for your appreciation !

I hope indeed this page will draw more researchers. I will update and expand it in 2021, no doubt, and add as many reference i can, pdf and sites on the topic.

Fair winds and following seas !

Do you plan to share your transcriptions? The Wenonah Historical Society has a model of the Eagle Wing made around 1872 or so and it would be so great to have some insight about life on board this wonderful extreme clipper. We have learned about Captain Linnell recently but not much else.

You can see the model at this link.

http://wenonahhistoricalsociety.org/Eagle-Wing-clipper-ship-model-by-Andrew-W-Carey

Sure !

However i can’t access your page, my ip is banned apparently.

Hi! I am a Descendant of Captain Ebenezer Linnell, Commander of the Extreme Clipper Ship, The Eagle Wing. I am trying to paint The Eagle Wing and am struggling with accuracy while avoiding plagiarism of the two paintings I’ve seen. Have you run across any details of the ship that sets it apart from others? Does it most closely resemble the Taeping?

I am very interested in the diary of your forefather. How lucky you are to have this! Will you be publishing? Any interesting info on Captain Linnell? Was he liked?

Thank you so much for your time.

JoAnn Adams

http://joartcountry.gallery.com

@artbyjoannadams

Philip Gunther New zealand

I RECENTLY PURCHASED A Photo framed ,of a three masted ship under full sail ,main sails stacked four high

It is hard to make out the name ,but it looks like

Teabel

Any help please ,thanks

Hello Philip, must be “Taeping” It was indeed quite a famous Clipper, of 1863 built by Robert Steele & Company of Greenock and owned by Captain Alexander Rodger of Cellardyke, Fife. Taeping participated in The Great Tea Race of 1866 and narrowly defeated the Ariel.

Best,

David

I am writing a book on a woman who sailed with her officer husband & children to New Zealand on the Chariot of Fame. I am trying to find a description of the ship’s figurehead but can’t find one in any of the key clipper ships texts though they do mention the ship. Where else could I look?

Hello Cathy, indeed no close photo of the ship, the closest i found for the figurehead (if this is the same) is this

I just added the photo on this article BTW. Good luck for your research !

Sugar, cocoa and coffee is what the French clipper named BELEM transported, not nitrate. Just a small correction if you don’t mind. Great website , thanks for sharing!!! The BELEM will carry the Olympic flame from Athens to Marseille for this year’s Olympics. Come and admire the ship in its full gloryl

For those interested in clipper ships, I started a facebook group for them: “The Clipper Ship Era”.

https://www.facebook.com/groups/1150884902100229