The Crimean War: Generalities

The largest war of the 1850s

The Crimean War (1853–1856) was a major conflict fought between the Russian Empire and an alliance of the Ottoman Empire, France, Britain, and Sardinia. It was primarily sparked by disputes over Christian holy sites in the Ottoman-controlled Holy Land and the declining power of the Ottoman Empire, which European nations sought to control or protect.

Key Causes:

- Religious Disputes: Russia sought to protect Orthodox Christians in the Ottoman Empire, while France supported Catholics.

- Russian Expansionism: Russia wanted to extend its influence over Ottoman territories, particularly in the Balkans.

- British and French Interests: Britain and France opposed Russian expansion, fearing it would disrupt the balance of power in Europe.

- Strategic Control: Russia aimed to gain access to the Mediterranean via the Black Sea, threatening British and French trade routes.

Major Events:

- 1853: The war began with Russia invading Ottoman territories (Moldavia and Wallachia).

- Battle of Sinop (1853): Russian forces destroyed an Ottoman fleet, triggering British and French intervention.

- 1854-1855: The Allies landed in Crimea, leading to the prolonged Siege of Sevastopol.

- 1854: The famous Charge of the Light Brigade occurred during the Battle of Balaclava.

- 1855: Sevastopol fell to the Allies.

- 1856: The war ended with the Treaty of Paris, which weakened Russia’s influence and declared the Black Sea neutral.

Impact:

-Russia lost influence in the Balkans and was forced to demilitarize the Black Sea.

-The war exposed inefficiencies in European armies, leading to drastic military reforms.

-It was one of the first wars covered by war correspondents and photographers, shaping public opinion.

-On the Naval side, it saw the triumph of steam over sail, explosive shells over fortifications, and armoured batteries.

-Some of these aspects were further confirmed ten years later in the Americas

Naval Implications

This conflict, as questionable were its goals, saw for the first time cargo ships and armored batteries demonstrates their usefulness, as well as the Paixhans carronades, well adapted the parabolic fire of fortification bombardment.

The Russian demonstrated themselves at Sinope, at the very opening of the War, as deadly and efficient these new explosive shells could be, wiping out the almost entire Turkish fleet with unsignificant casualties on their side.

The Crimean War is rooted in the willingness of the Russian empire to put an end to the domination of the Ottoman Empire, “The sick man of Europe”, while guaranteeing itself access to the Black Sea.

The Russians seen themselves-the tradition was passed through the Cossack struggle since the XVIth century- as the champions of opressed peoples against the Ottoman empire. The British, which had long-term commercial treaties with the “sublime door”, see the Russian ambitions over the black-sea and Constantinople, as a threat to their free trade in this area.

Napoleon III, as did the Tsar, are challenging themselves to see who would offer protection to the holy places of Jerusalem.

The French were also reserved the favor of this protection to themselves. Annoyed, the Tsar turned to the British, offering an alliance to put an end to Turkish rule over the holy places. The latter refused, fearing that the Russians could have an access in the Mediterranean.

The Tsar then decided to make the law for itself and attacked the Turkish fleet in the Black Sea (Sinope) and invaded Rumania (Ottoman territory) and the Caucasus, were also black oil and coal were abundant, needed to the emerging Russian industry.

Against all odds, Napoleon III, willing to equal the glory of his great-uncle, saw an opportunity and asked for an alliance with London, for the first time since the Crusades. War is declared on March 27, 1854.

Operations

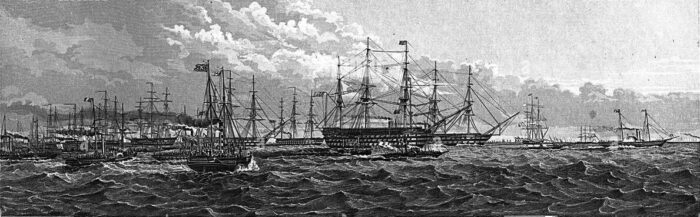

A combined fleet headed by Lord Raglan, commander-in-chief of the allied forces, rallied in the Mediterranean and landed troops in the Crimean peninsula at Eupatoria. After losing many men by illness, the real landing took place at the North of Sebastopol.

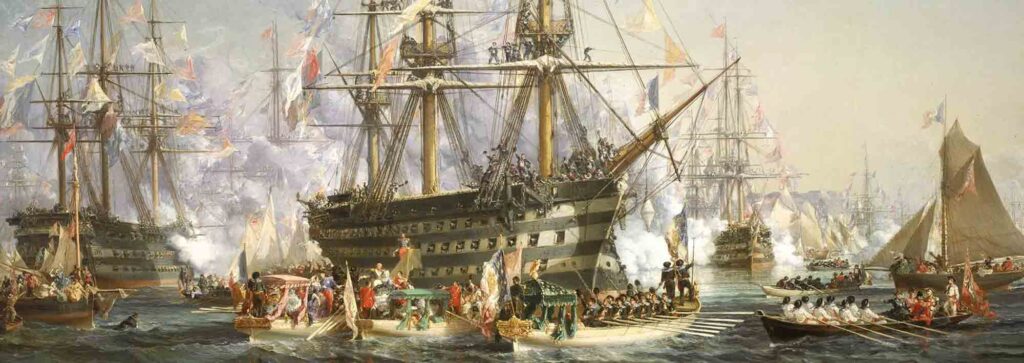

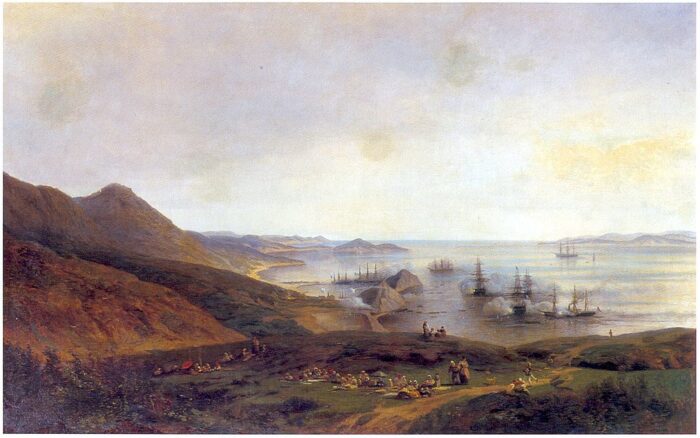

Diorama of the siege of Sevastopol and painting of Roubault.

A decisive victory is achieved on the Alma, and the allies marched on the fortress of Sebastopol, beginning a long siege of two years, burying in trenches. The situation remains hopelessly frozen, despite the coastal bombings and reinforcement of the Piedmontese and Sardinians, the interior remains inaccessible. The Russians desperately counter-attacked but were repelled each time with heavy losses in both sides.

The famous charge of the British Light Brigade, originated in a misunderstanding, although unfructiful, became legendary under the pen of Alfred, Lord Tennyson. Soon after, the battle of Balklava, south of Sebastopol, really took the brunt of allied forces. The real attack came on September 8, 1855, when Marshal MacMahon at the head of his Zouaves stormed Fort Malakoff. From this breakthrough, the Allies eventually bring down the place.

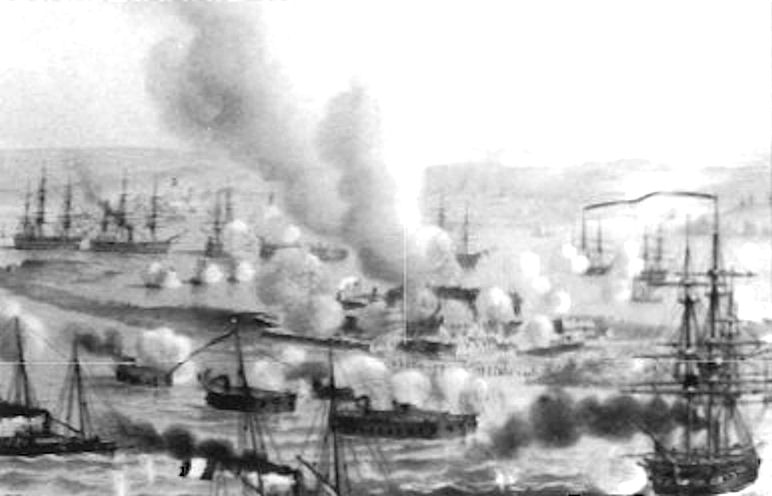

The bombardment of Bomarsund in the Baltic

But the Russians have previously withdrew, crossing the strait on a pontoon bridge and blew up the remaining magazines. The Allied engineers ensured that the fortifications were erased for good, preventing any return of the Russians there. On March 30, 1856, the Tsar asked for and obtained peace, signed in Paris.

The prestige and influence of Napoleon III has been strengthened and thus, convincing him to carry two other campaigns, one successful, the Italian war against Austria, and one which achieved nothing, the Mexican adventure. But his confidence over his army and his own capabilities proved eventually fatal against the Prussians in 1870…

French floating batteries in action at Kinburn. Below, Lave, one of the devastation-class batteries engaged.

For the Russians, as the Emperor himself stated, this was only a minor defeat (“sebastopol is not moskow”). The Russians will remained in the Caucasus and eventually seized once again the Crimean peninsula. But the conflict showed how was important to equal modern, industrialzed countries like Great Britain and France, leading to a stream of reforms by his successor, Nikolai II. However, the “sick man of Europe” never recovered.

With the loss of its most formidable fleet, what was left began to crumble, and the Ottoman empire losed all its territories in the Balkans, and others after, until the first world war, where it was reduced to the territory of nowadays Turkey.

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

Map of the Crimean war, operations and moves in the Black sea.

On the maritime side of this war, we will saw a panorama of no less than four naval powers, as they were in 1852. Both Great Britain and France were unrivalled becaused of their wealthiness and industrial might, although France was still much more rural than industrial per capita, with export/imports and steel production far beyond the United kingdom, its engineers made it possible to built the very first steamship of the line, the Napoleon.

This ship was launched in 1850 and was part of the french squadron. It demonstrated, as well as the armoured prams (Devastation class) combined with heavy mortars and Paixhans shells, how efficient this combination could be against fortifications.

Conclusion

Soon after the Crimean war, the British admiralty ordered several ships of the line to be converted also. In 1870, steamships were the bulk of both fleet, by far. The Russian fleet however, was less impressive and much more classical. Its only innovation -which proved decisive however- was the adoption of Paixhans shells. On the paper, the Turkish fleet was even greater, but many of its ships lacked of everything, including trained gunmen and crewmen.

Its ships were sitting ducks at Sinope. They were mercilessly hammered and took so much punishment in so few time, that they were soon silenced and burned to the bottom.

Significant events:

> Battle of Sinope: Which saw the doom of the Turkish fleet.

> Naval bombardments: How the Russian forts were overwhelmed.

The Belligerent Fleets and their ships

The Royal Navy in 1853

This chapter is after the world biggest navy in the world. From its outstanding military success against the Napoleonic and Spanish fleets under Nelson command, the Royal Navy grew constantly as well as the Empire. It was in 1820, and remains until 1850, a massive, unrivalled force of 130 ships, with at least twenty three deckers. However, despite the success of its civilian steamships and its pioneering role in steam history (Archimedes, the first screw steamship, SS Great Britain, the first iron hulled liner, etc..), the navy was -by nature- conservative.

The arch-enemy, the French, under Napoleon III, seems to have never seriously considered a war with Britain. However, the Crimean war gave the British the sight of new technological advances, which could change naval tactics and were to be considered. The first step was the French Napoleon, showing in 1854 that the steam was not only fit for gunboats-class ships. But as early as 1852, the screw ship of the line, 92 guns HMS Agamemnon, was launched, entering service in 1854. Many other followed or were converted.

In 1862, they were no less than 56, built as such or converted while on the stocks, outnumbering the french by two to one. (The objective then was to built a navy able to cope with both French and Russian fleets). This force was added to a fleet of 10 active sailing ships of the line, 9 guardships/blockships, and 27 more still in the effective list (among them, three 120 guns), giving a grand total of no less than 91 two and three-deckers ships.

Duke of Wellington

HMS Duke of Wellington: The biggest British screw ship of the line ever, and shortly before arrival of the Ironclad era, the biggest warship afloat ever. The DoW was a former sailing ship, converted while on the stock in 1852. She was even bigger than the French Valmy.

And this fleet counted no less than two screw 130 guns, five 120 guns, two 110 and six 101 guns flaghips. They were second rate as well as third rate (90 to 60 guns). Fourth and fifth rate were now an obsolete classification.

The Carronade, a scottish (than British) discovery, was still largely used on brigs and corvettes in 1852, and Paixhans shells were massively produced. The french armoured batteries that reduced the Russian forts in rumbles were noticed as a curiosity.

But in 1859, the French Gloire stirred the press in Britain, although the admiralty was less impressed. Plans for a much more powerful iron hulled ironclad were already drawn, and by 1860, the HMS Warrior was built. (See the franco-prussian war for the Royal Navy in 1870).

To summarize the Royal Navy during the 1853-55 campaign in Crimea, a handful of ships were given the task to cover the landings, and neutralizing the Russian forts. Many blockships, originally made to deal with the ever-lasting threat of a French invasion, were given some rigging and used succesfully as bombardment ships in Crimea.

British empire naval forces, order of battle :

– Screw three deckers : HMS Wellington (131 guns, 1852), Conqueror (131 guns, 1855) Marlborough (131 guns, 1855), Royal Albert (121 guns, 1854), St Jean D’Acre (101 guns, 1853), Waterloo (120 guns, 1833-converted 1854).

– Screw two deckers : 18 two-deckers from 1852 to 1855, ranging from 72 to 91 guns. Some were sailing ships converted in 1854-55.

– Screw frigates : Unknown.

– Screw Corvettes : Unknown.

– Screw guard ships and blockships : nine old 74 guns, dating back from 1809 to 1822 and converted from 1837 to 1855. None fought in Crimea.

– Paddle frigates : Unknown.

– Paddle corvettes : Unknown.

– Screw sloops : Unknown.

– Paddle sloops : Unknown.

– Screw gunboats : Unknown.

– Sailing ships of the Line : 10 ships from the first to the third rate (120-74 guns), dating back 1821 to 1844, and 27 other waiting to be cast from the effective list.

– Sailing Frigates : Unknown.

– Sailing corvettes : Unknown.

– Brigs : Unknown.

The French Navy in 1853

This chapter is after the second world biggest navy in the world. Despite the complete loss of the old, royalist french fleet during the revolution and the napoleonic era, the new kings reestablished its rank while building a constant array of sailing corvettes, frigates and ships of the line.

When Napoleon III came to power, it was obvious that a strong navy was the only way to built and sustain a colonial empire, as to be a threat over English seatrade net. The industrial weight of France was built mostly since the arrival of a new bourgeoisie under king Louis-Philippe. By its size, it was far below the level attained by the United Kingdom, but still capable of making good steal plates and complex artillery pieces.

The military research during Napoleon III, both for the army and navy,was well-favored and well-deserved by skilled engineers from the elite technical schools founded by Napoleon Bonaparte fifty years before. So in 1850, everything was ready for some breakthrough in naval warfare in france.

Dupuy de Lôme and Paixhans : These two frenchmen, one a succesful engineer, the other a resourceful officer, gave France the edge in military technology, the first while conceiving the very first steamship of the line (the Napoleon), and the second, the naval high explosive shell. As Paixhans guns were quickly adopted by many navies, the Napoleon was the very first of its kind.

Until then, naval conservatism and defiance toward steam prevented any such attempt. In 1840, the only military steamships were light dispatch vessels, and gunboats, only fielding a handful of medium and light guns. The only reliable propeller available then was the sidewheel system. A single hit in one of these, and the ship was doomed. So not only these ships were always fully rigged, but they never fully included in the naval fleets or admitted in exercises.

But the adoption of the screw (by the british Archimedes in 1837) began to change the way steam power could be used onboard ships. The very first screw steamships were civilian liners and dispatch (mail) ships. This was usually a lifting screw, and by windy weather, the ship ususally proceed by sail only. The first major screw steamship ever to be built was Brunel SS.

Great Britain, which was also the first all-iron liner. It was to impress so much the French that Dupuy de Lôme decided to plan a major warship with a screw. This led to the Napoleon. Despite some strong septicism from the admiralty, the enthusiastic Napoleon III ordered one to be built in 1848. And then, the very first was ready for the end of 1850, quickly followed by several sister-ships, and commtied succesfully in trials and naval exercises.

The Napoleon was the first steam two-decker (plus one incomplete) ever to use steam propulsion and a lifting screw, as well as beeing fully rigged. It was based on the usual first class warship of the time, the 90-guns.

In fact the Napoleon was followed by Algésiras, Arcole, Imperial and Redoutable launched in 1855-56, all beeing 5040 tons in displacement. In 1853, two 80-guns of 4330 tons were launched (Duquesne and Tourville), and the three Wagram class in 1854 (4560 tons), 90 guns. The Charlemagne (80 guns, 4060 tons) was launched in 1851, Jean Bart (76 guns, 4010 tons) and Austerlitz (86 guns, 4430 tons) in 1852. Many other steam ships-of-the-line were built during the crimean war (see 1870 records), as well as nine other sailing two-deckers of 90-guns converted as steamships from 1857 to 1860.

Some three-deckers were also converted, in fact, all four of the Friedland class (5170 tons, 114 guns) in 1854-58, and the Montebello (4920 tons, 114 guns), converted in 1852 was the only one which served during the Crimean war. The very first purpose-built steam three-deckers was the impressive Bretagne, a 6770 tons, 130 guns.

Unfortunately she was launched only in 1855 and therefore was not in service before the war ended. Depite of this, she demonstrated that even such gigantic ships could be propelled by steam power. Of course, cumbersome boilers and an enormous amount of coal in such ships led to gave them a deeper hull below waterline, thus reducing their habilities to be anchored in many shallow water ports.

The Crimean war allowed this new breed of warship to be put on the test. The Napoleon, as well as its sister-ships performed well against the Russian forts. In fact, one episode was so famous that it changed completely the way the British admiralty seen these French experiments…

Heavily pounded and its rudder disabled, one of the french sailing three deckers was pushed by the current near the forts and the reefs, when she was took in charge and towed by Napoleon out of any danger(the weather was sunny and very calm, perfect for gunnery practice, but all windless sailing ships were unable to evolve). This episode proved that the steam power, not only still allowed the ship to bombard succesfully the forts, but also to save an almost doomed traditional three-deckers.

The Paixhans guns were also put to the test. During the Sinope naval engagement, the Russian fleet famously burned most of the Ottoman fleet, which was almost unable to respond. Later in Crimea, some relatively light, french floating batteries were able to bombard the forts, blewing up their magasines and burning the unprotected crews from above (they fired on parabolic angles).

The batteries, of the Devastation class, were specially built for this task, and were also heavily protected, in fact, they were armoured floating batteries, and remained all safe from the Russian replies.

French naval forces, order of battle :

– Screw three deckers : Montebello (114 guns, converted in 1852) in service as 1854.

– Screw two deckers : Napoleon (1850), Charlemagne (1851), Jean Bart (1852), Austerlitz (1852), two Fleurus class (1853), two Duquesne class (1853), three Navarin class (1854).

– Screw frigates : Isly (1849, 2690 guns, 40 guns), Bellone (1853, 2350 tons, 36 guns) and Pomone (1845, 1900 tons, 36 guns).

– Screw Corvettes : The two D’Assas class (1854, 2100 tons, 16 guns), the three Primauguet class (1852, 1900 tons, 10 guns), Roland (1850, 1970 tons, 8 guns), and three iron hull ships : Reine Hortense (1846), Caton (1847), and Chaptal (1845).

– Screw Devastation class armoured floating batteries : Five purpose-built ships launched in 1855 and ready in time for the end of the war.

– Paddle frigates : 19 ships, all from 1841 to 1848. Ranging from 20 to 8 guns, and 2460 to 2820 tons.

– Paddle corvettes : 14 ships, from 1838 to 1851, ranging from 900 to 1600 tons, and from 4 to 10 guns, two were Iron hulled.

– Screw sloops : 5 ships : Biche, Corse, Lucifer, Marceau class, and Sentinelle. From 400 to 900 tons, 120-150 nhp, 2-6 guns. 13 other built after the war.

– Paddle sloops : 37 ships from 1830 to 1855, 400 to 900 tons, and 2-6 guns.

– Screw gunboats : 26 mixed sail-steam 2 to 4 guns ships, and 31 iron hulled one-gun, steam only batteries.

– Sailing ships of the Line : Valmy (114 guns), Hercules and Jemmapes (90 guns), Iéna, Inflexible and Sufren (82 guns), Jupiter (80) and Duperré (70).

– Sailing Frigates : 27 ships ranging from 38 to 56 guns.

– Sailing corvettes : 11 ships of 22 guns and one of 38 guns.

– Brigs : 21 ships equipped with 8 to 14 carronades and one with two heavy paixhans Mortars.

The Russian Navy in 1853

As Russian main industry was agriculture, they were few facilities skilled enough to deliver reliable steam engines as 1850. So far, the bulk of the fleet was made of many sailing three and two deckers, equipped with 130 to 74 guns. The former navy was built carefully during Peter the Great and Catherine of Russia rules.

St Petersburg was a major warship harbour of strategic importance for all Baltic Sea, as well as Sevastopol in Crimea. The majority of the screw vessels were built from 1856 to 1860, after the Crimean war, and the major ships were all based in the Baltic, while frigates and corvettes were based equally in the mediterranean and in the Far east. The very first Russian ironclad was built in 1865. It was based on a frigate and converted in 1862 at Kronstadt.

As from the Russian perspective, the French and British were Christian nations, and as such the fact they could wage war against Russia to defend the Ottoman Turks was unbelievable. So the Russian navy, in relative understrength compared to the Ottoman navy, but counting half of Paixhans guns, attacked the squadron at Sinope, the Black Sea stronghold, as the first move against the Ottoman Empire.

This was purchased notably to ensure safe passage of troops and materials in the Black Sea. Obvious Russian ambitions in the Mediterranean, were both the French and the British has commercial and strategic interests, as well as the well-known weakness of the Ottoman Empire, came as a threat sufficient to intervene. During the whole Crimean war, no Russian ship was ever committed against the allied armada. They relied on forts.

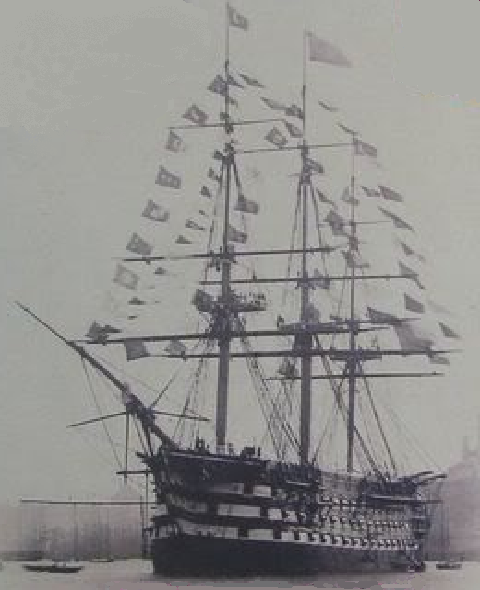

The Akeksander Nevski flagship of the Russian navy, an impressive first-rate, three deckers sailing ship of the line, which fought at Sinope.

The Russian navy, as for 1853, was no match for the combined allied forces. They retreated and the bulk of the navy was stationed in the Baltic sea, were naval operations, once again, were directed toward an impressive line of naval fortifications.

Russian empire naval forces, order of battle :

To be completed.

The Ottoman Navy in 1853

Ottoman flagship Mahmudiye in Istambul

FOCUS: Mahmudiye, the largest ship in the world for many years.

Built on plans prepared by naval architect Mehmet Kalfa and naval engineer Mehmet Efendi at the Imperial Arsenal, Constantinople, she was Launched in 1829. She was 76.15 m (249.8 ft) long (hull only), for a 21.22 m (69.6 ft) beam, displacement unknown. Sailing ship only she was never converted to steam. One of the rare first-rate three deckers, she was in reality a four decker, with its utmost deck partially provided cannons and partially covered.

She carried a massive crew of 1,280 sailors on board, and her cannons ranged from 3-pounders (upper open deck) to 500-pounders stone firing bombards at the lowest deck.

She participated in the first Egyptian–Ottoman War in 1831, but in poor condition, because of her dry-rotted hull. She served as flagship and was assisted by a British Royal Navy to blockade the main Egyptian naval base at İskenderun, concluded by a long-range shalling on 18 August 1831. In 1839, an internal power struggle pushed the pro-Russian Husrev Pasha on the throne (Sultan Abdulmejid I) while the commander of the Ottoman fleet decided to take the bulk of the Ottoman fleet in Egypt. The ship was bargained for in July 1840 by the British an the Egyptians refused, this being followed by the bombardment of coastal cities, until the ship was returned to Constantinople. She also participated in the Siege of Sevastopol (1854–55) under command of Admiral Kayserili Ahmet Pasha and honored with the title Gazi for her successful mission. Although conversion to steam was considered, the hull was inspected before in Britain by the late 1850s, before it was discvered her poor condition prevented any attempt of reconstruction. The machinery reserved for her ended on the frigate Mubir-i Sürur instead.

The mighty Mahmudiye took no part in the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878, being relegated as troop transport. But on 27 December, she was attacked by four Russian torpedo boats (as well as the ironclad Asar-i Tevfik), but missed. She was decommissioned in 1874 already and scrapped after the war.

Ottoman empire naval forces, order of battle :

After the battle of Navarino (1827), were the Russian Navy decisively defeated the Ottoman fleet, the Empire did no lost time rebuilding its fleet. In 1839, so fifteen years before the events of Crimea, some impressive ships had been purchased or built, including the massive Selimiye (1809), a 128 cannon, and in 1829 an even bigger vessel with the same number of guns, on four decks, the Mahmudiye. The former was probably not around in 1850 but the latter, certainly. At Sinope in November 1853, the Ottomn deployed a fleet of 7 frigates, 3 corvettes and 2 steamers. They were engaged by a larger Russian force of 6 ships of the line, 2 frigates and 3 steamers, using Paixhans bombs. The 44-gun Ottoman flagship was Auni Allah, confronted the Nakhimov’s lead ship 84-gun ship Imperatritsa Maria. One of the two steamers was the 12-gun paddle frigate Taif, sole to escape the disaster. Were lost that day all sailing frigates, Avni Illah (44 cannon), Fazl Illah (44), Nizamieh (62), Nessin Zafer (60), Navek Bahri (58), Damiat (56), Kaid Zafer (54)

– Four deckers : Mahmudiye (1829), 128 guns

– (Screw) three deckers : 96 cannons Fethiye class (1827-1836), 5 ships. Necm-i Zafer (1815, 74 cannons)

– (Screw) two deckers : Two 64 cannons, Hifz-i Rahmân (1826), Nusretiye class (1835-36, 3 ships)

– Screw frigates : Mecidiye (1846-48) Saik-i Şadi and Feyzâ-i Bahrî (30 guns), Mubir-i Sürur (1847) 22 guns.

– Corvettes (Sinope): Feyd Mabud (24), Kel Safid (22)

– Paddle frigates (Sinope): 12-gun paddle frigate Taif

– Sailing ships of the Line : Unknown

– Sailing Frigates : Hıfz-ı Rahmân 60, Feyz-i Mi’rac 48, Keyvan-ı Bahrî 48, Fevz-i Nusret 64, Bandino Seret (48), Mejra Zafer class (10 ships, 42 guns), Nouhan Bahari 50, M’sian Zafer 50, Chabal Bahari 50, Naoum Bahari 50, Muîn-i Rahmet 40, Avnillah 50, Yâver-i Tevfik 32, Suriye 56, Tâir-i Bahrî 62, Mirat-ı Zafer 44, Şihâb-ı Bahrî 64, Pîr-i Şevket 58, Nâvek-i Bahrî 42, Nusretiye 60,

Reşid, Avnillah 50 or 36, Nizâmiye 64 or 60, Nesîm-i Zafer 48 or 32, Fazlullah 48 or 38, Nâvek-i Bahrî 42 or 52, Dimyâd 42 or 54, Kâ’id-i Zafer 22 or 50, Nacm-i Zafer 52, Zır-i Cihat, Serafeddin.

– Sailing corvettes : Unknown.

– Brigs : Unknown.

Src/Read More

İsmail Hami Danişmend, İzahlı Osmanlı Tarihi Kronolojisi, 4. Cilt, Türkiye Yayınevi, p. 148.

Candan Badem, The Ottoman Crimean War (1853-1856), Brill, 2010, p. 117.

Winfield, Rif (2008). British Warships in the Age of Sail 1793–1817: Design, Construction, Careers and Fates. Seaforth Publishing

1853-1856

1853-1856

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign

Interesting piece. I read somewhere that the Vulcan became the first ship to engage in minesweeping operations. Have I missed it here? Whose ship was it?

Thanks, i’m working on the Prussian Navy in 1870 so i should cover it if i find enough info.