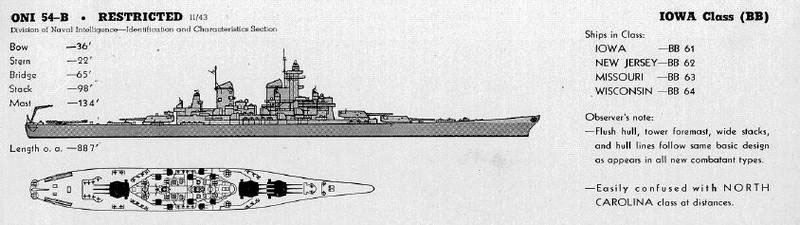

Iowa class battleships (1942)

Battleships (1942-44): USS Iowa (BB-61), New Jersey (BB-62), Missouri (BB 63), Wisconsin (BB 64), Illinois (BB 65), Kentucky (BB 66)

Battleships (1942-44): USS Iowa (BB-61), New Jersey (BB-62), Missouri (BB 63), Wisconsin (BB 64), Illinois (BB 65), Kentucky (BB 66)

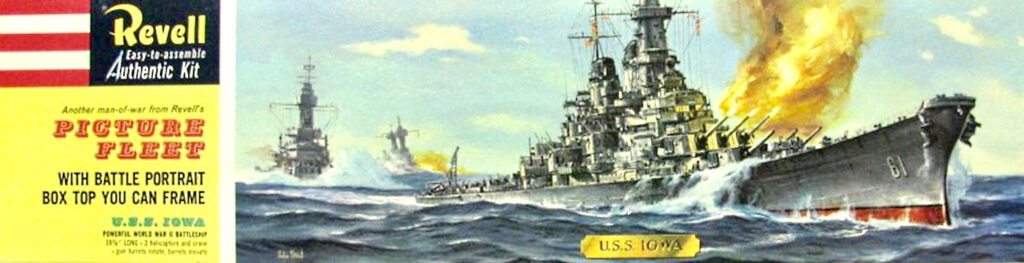

The Iowa class battleships were the last built in the US, and memorable ships at more than one title. They were the culminating point of a standard design worked out since 1934, but built for speed, and the first using the escalator clause to reach a larger tonnage. If their WW2 career was short, they emerged from the reserve to take part in the Korean War, the Vietnam War, putting their main artillery to good use when older fast battleships had long met the scrapyard. If their fate seemed sealed after 1973, they were unexpectedly resurrected and completely modernized during the Reagan administration to counter the Soviet Kirov class battlecruisers. They fired their last rounds in the gulf war of 1991 and are now preserved as the world’s last active battleships. #USN #ww2 #coldwar #iowa #newjersey #missouri #mightymo #wisconsin

A fitting end to this year’s study of WW2 USN Capital Ships.

Note: This post, like the one on the Queen Elisabeth class, is so large in scope, that it will be limited to the construction and WW2 career of the Iowa class. A new post will be dedicated on their cold war career and comprehensive refits in 2023.

The last USN battleships: Iowa class

All four Iowas in formation for the first and last time of their carrer. An historical photo for the pinnacle of conventional warship development.

The Iowa class were originally six fast battleships ordered in two batches, in 1939 and 1940. They were intended at first as very fast ships, almost battlecruisers, to intercept the Japanese Kongō class while still able to take their place in the battleline. The Iowa class were also designed to meet the Second London Naval Treaty‘s “escalator clause” reaching the limit up to 45,000-long-ton (45,700 t) of standard displacement.

Ultimately only the first four were completed, while USS Illinois and Kentucky were laid down, but canceled in 1945 and 1958, and scrapped. Ultimately the new Montana class were preferred, but also cancelled in July 1943 in favor of completing the Essex-class fleet carriers as the last battleship class ever designed for the United States Navy.

This made the four Iowa-class, the last battleships ever commissioned in the US Navy. They had a short but eventful carrier in the Pacific in 1944-45 protecting the Fast Carrier Task Force during the last phases of the Island Hopping Campaign, until the surrender signed on “Mighty Mo”. Decommissioned in 1947 in long term reserve, they were recommissioned for Korea and Vietnam. Completely modernized in the 1980s (a full chapter here) they became missile-carrying battleships (with quite amazing alternative projects) fighting in four major US wars. This post will dive deep into these very long careers, but before that, their development whereabout, design in detail, construction, the fate of their cancelled sister ships, a bit on the Montana class, their modernizations history, until the great 1980s refit.

Summary

- Development History Context

- Design Work

- Detailed Design

- Powerplant

- Turbines

- Boilers

- Performances

- Propellers and shafts

- Auxiliary Power

- Armament

- Main Guns: Nine 16-in Mk12

- Secondary Guns: Twenty 5-in/38

- 40mm Bofors AA

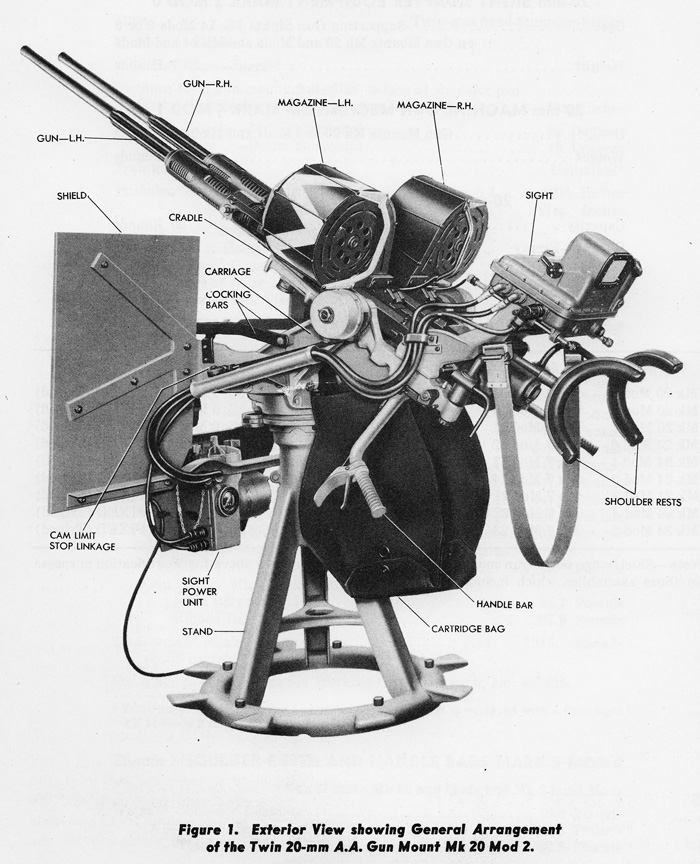

- 20mm Oerlikon AA

- Electronics

- Radars

- Fire Control Systems

- Electronic Counter Measures

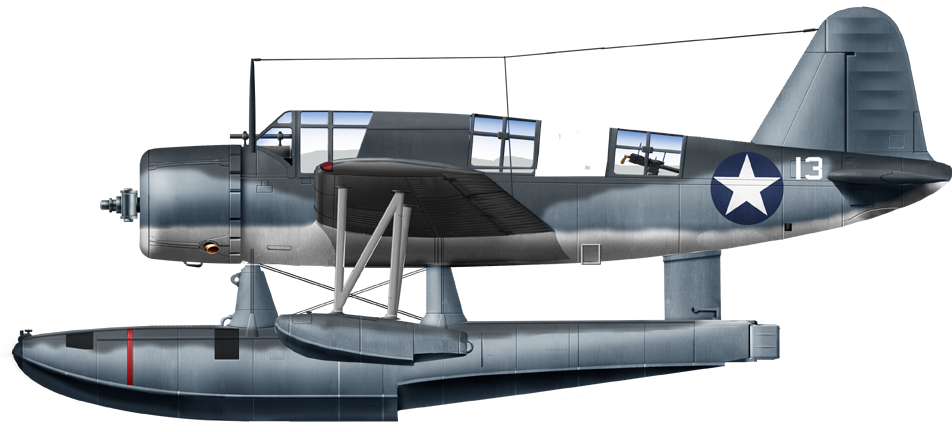

- Onboard aviation

- Other specifics

Development History Context

Initial motivations and discussions

A model of the North Carolina class in 1937

Very early origins could be traced back to the various discussions and preliminary designs leading to the North Carolina class battleships, so all back to May-June 1935 when the General Board asked for a new battleship design with three design studies submitted and discussed. The first two proposals had 14-in guns, but ”C” (over 36,000 long tons) and with 30.5 knots proposed eight 16-inch/45-caliber in a classic 4×2 configuration. In short a fast version of the West Virginia. The caliber choice was going to stick later, as the Bureau of Ordnance (BuOrd) announced its new standard being a new “super-heavy” 16-inch shell, leading to the updated proposals “A1”, “B1” and “C1”. The problem was they all went beyond the 35,000 tones standard authorized, to 40,000 long tons.

Importantly, as dicussions progressed the new “fast battleships” as called that way by the General Board, could have their top speed used as adjustment variable, not to compromise the protection, and the Naval War College suggested 23-knot as a good compromise as shown in their own war games, compatible with older standard super dreadnoughts. Five more proposals were studied until September 1935 with a speed pushed again to 30.5 knots but still discissions about nine 14 inch or 16-inch guns, the latter reaching 41,100 t.

Eventually Designers reported as how hard it was to deliver a balanced design over a 35,000 tons limit to reach 30 knots a massive output was needed, and so a large hull. Even quadruple turrets (14-in guns) were studied. By October 1935 the board settled on “A”, and if possible four battleships to match the rebuilt Kongō class.

The Secretary of the Navy and Chief of Naval Operations, president of the Naval War College decided by late October 1935 to work on “K” design, to be further developed. But the game changer in the treaty, was that the US benefited from an exception, the “Escalator Clause” in the case a country adhering previously to the Washington Naval Treaty was out.

Of course there was no mystery about who, which happened to be Japan. This clause, enable signatories, engaged to limit themselves to 14-in (fixing the main armament of the King Georges V class as we know), could swap to 16 inches, allowed to all three signatories during discussions. This also applied to Italy, that also retired and went for the 15-in Littorio class. The signing date was 1st April 1937 indeed. As time pressed, initial plans for the new US fast battleships were to require a rapid “switch” option from 14 to 16-inch after being laid dow, which proved nightmarish for the engineers. However on 27 March 1937, Japan’s position was made clear to all and the US played the “escalator clause”, and this despite political pressures to tone this down on President Roosevelt by the congress and democrats at large.

Beyond the escalator clause: Vinson and Vinson-Walsh Acts

Blueprint, C&R outboard profile of the North Carolina class (still showing portholes) in 1937.

Eventually the conclusions of the Consequences of the London Naval Treaty (1936) signed by Britain, France, and the United States had conformed the 35,000 tons and 16-inch as max caliber confirmed. The treaty started to apply by January 1937 and from 1934 onwards already, there has been planning of 45,000 tons plus vessels in case the Japanese pull-out from the Washington accord, which they did eventually by refusing the London prolongation. Eventually the last 35 designs studied in 1936 were mrre variations five base designs published on 15 November 1935. All were about 35,000 long tons to fit a possible production FY1937. The problem was, compared to the Kongo, that thet were all around 27 knots-26.5 knots and sizes of 710 to 725 ft but still wild discussions and variants in artillery.

The second major decision after the Escalator Clause was the second Vinson Act of 1938. It officially authorized the construction of these first fast battleships, and from 35,000 tons/14-inch guns BB-55 were laid down at New York Naval Shipyard, leaving still time to alter the blueprints and swap to the later classic nine 16-inch guns while protection was equal to 14-in shells immunity. The second Vinson Act was to grant an increase of capital ship size of 20% and get rid of the London Treaty limitations.

On June 30, 1938 what was known as the “sliding scale” clause enable a 16-in armed 45,000 tons for good, raising the bad will showed by the Japanese to British inspection. This led to six new ships, outside the fiorst two “prototypes”, USS North Carolina and Washington. These were important for the next phase buildinf four SOUTH DAKOTA class with revision and then a pair of the IOWA Class, on a modified North Carolina design. Modified indeed: By looking at all three battleship classes side by side seen from above it appeared clearly the North Carolina design was simply shortened or at the contrary stretched up to accomodate more power or protection depending on the case.

Evbentually, the Vinson-Walsh Act of July 19, 1940 had this first act passing the treshold of “wartime level” which was curcial into authorizing 18 new fleet aircraft carriers of the Essex class and two additional Iowa-class and five larger, better armed montana class, the first “not-limit” wartime design. This went with 33 cruisers, 115 destroyers and 43 submarines.

“Plan Orange”: The war with Japan scenario

Initial design scheme for the Montana class (at the time S511-13 Battleships Study scheme 8 BB65 study, 15 March 1940)

Initial design scheme for the Montana class (at the time S511-13 Battleships Study scheme 8 BB65 study, 15 March 1940)

Plan Orange was a written senarion to be played at the naval college, of an attack of Japan on the US. This took place in the Pacific, not the atlantic, and had consequences for ships’s designs, not only to comply with greatr range, but also to what Intel reveals about Japanese capital ships at the time. War planners anticipated a main combat in the Central Pacific, this with an extended line of communication and complicated logistics vulnerable to fast Japanese cruisers.

The standing force of super dreadnoughts in Hawaii at the time, with their 21-knot were just too slow to face Japanese task forces, while in a scissors/paper.rock fashion, the faster carriers and cruiser escorting them would be easy prey for a composite force of fast battleships (such as the rebuilt Kongō-class) and fast cruisers. The US Navy was a “fast detachment” capable or operating with and outside of the battle line and met these opponents on more equal terms. All knew that because of the previous limitations, neither the North Carolina-class or South Dakota-class can met the ideal speed to fit the task. They were more likely to be deployed with the main battle line or on the Atlantic.

I short, the USN planned battleships designs capable of 30 knots but also had the idea of contituting a special strike force of fast battleships with carriers and destroyers to act independently as a scouting force. This concept would evolve into the Fast Carrier Task Force, with battleships ending as mere auxiliaries or escorts. In all cases, engineers were now free to work on a larger tonnage design, thanks to the escalator clause being ratified by all signatories in June 1938, and establishing the limit to 45,000 long tons (45,700 short tons).

Design Work

The “slow” battledesign scheme was apparently an elongated version of this, sometimes called the “Ohio class”.

Two designs by the General Board

The process had its roots in the first studies if early 1938, under the direction of Admiral Thomas C. Hart at the time, the head of the General Board using an additional 10,000 long tons (10,200 t) to give some extra possibilities. The first option was a mer development of the 27-knot (50 km/h; 31 mph) “slow” battleship design, with increased armament and protection, and a “fast” design capable of 33 knots (61 km/h; 38 mph) and more. The “slow design” ended as the better protected one, based on a shorter hull, the South Dakota-class.

The board was even enthusiastic about the possibility to mount no less tha nine 18-inch (457 mm)/48 guns, with more protection for 27-knot, enabled by the large tonnage. The “fast” design however was ultimately the one retained (which turned put to be the Iowa class). The “slow” design ended with a twelve 16-inch guns design 60,500-long-ton Montana class, from September 1939 as all limits were not out.

Priority went to the “fast” design only, clearly aiming at the Japanese Kongō-class battlecruisers, also taking into account the Panama Canal gates width as superior beam limit.

C&R fast battleships early study

The “fast” design was worked out by the Design Division section of the Bureau of Construction and Repair (C&R). The general concept was that of a “cruiser-killer” that can also engage fast Japanese battleships on equal terms. The study was led from 17 January 1938 by Captain A.J. Chantry. The base design comprised not nine but twelve 16 in guns and twenty 5-inch DP guns on a Panamax beam, and unlimited displacement with 35 knots and 20,000 nm range at 15. This resulted in a massive, 50,940 long tons standard battleship but the catch was a compromised protection just sufficient to stop 8-inch (200 mm) heavy cruisers guns.

Missing Pictures: Can’t find C&R designs. More on the Iowa class and this.

Thus, designs “A”, “B”, and “C” followed by late January with better draft and revised armor, and instead of 5-in, a battery of twelve 6-inch (152 mm) guns in eight twin turrets.

“A”: 59,060 long tons standard, 4×3 16-inch guns, 277,000 shp (207,000 kW) for 32.5 knots.

“B” was 52,707 long tons standard, 32.5 knots but based on 225,000 shp (168,000 kW) and 3×3 16-in turrets.

“C” was 55,771 long tons (56,666 t) standard, but had 300,000 shp (220,000 kW) for 35 knots and a 512 feet (156 m) long citadel.

“B” main belt ran for only 496 feet (151 m).

The Battleship Design Advisory Board Enters discussions

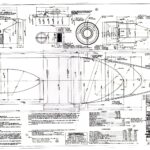

Battleship Study, preliminary design, showing on 8 July 1940 the recoignisable silhouette of the BB61 and outlines differences with the BB65 scheme (Montana class).

In March 1938, the General Board had an influx of recommendation for its branch, the Battleship Design Advisory Board: Naval architect William Francis Gibbs, Ny Ship building CEO William Hovgaard, John Metten, Joseph W. Powell, and Joseph Strauss, former admiral at the head of the ordnance dept. Not satisifed with C&R they asked for a new design study just based on a larger South Dakota-class design (stretched out, the extra space used to add boilers and possibly larger turbines). This would enable to reach 30 knots (56 km/h; 35 mph) on just 37,600 long tons. They estimated that to reach 33 knots they would need 220,000 shp (160,000 kW) on 39,230 long tons standard, well below the “escalator clause”.

This, compared to the more ambitious C&R studies, led the General Board to think that it was still possible to design a more moderate (and thus cheaper, the Congress still had to ratify this) to have a well balanced 33-knot while keeping even some margin with the “escalator clause”. Politically that would mean to think the US was not going to led a new arms race. Something proper to reassure Roosevelt and feel better when facing its majority or the Congress, but also the admiralty that still had a “wartime reserve” of useful displacement estimated to 5,000 tonnes and more.

However, further studies by C&R contradicted these enthusiatic design estimations:

-More speed needed more freeboard fore and amidships (so heavier hull) which also implied more armored freeboard, up to a feet in height.

-The consequence of above meant more weight to be braced to meet structure requirements.

-This trigerred in turn a larger power plant to maintain the speed. This resulted in a net increase of 2,400 long tons (2,440 t) even on conservative estimates. This also nullified the 5,000 long tons (5,080 t) of useful reserve (to add extra armour for example) and better AA.

The draft needed to be increase as well not to lost buoyancy but this enable a narrower beam and a bit required power (since lower beam-to-draft ratio reduces wave-making resistance). This also allowed the ships to be shortened, reduced overall weight. The General Board was dubmbfounded that 6 knots was traduced by an increase of 10,000 long tons, based on the South Dakota design. A harsh recall to reality.

However for this “price”, the new battleship had to show a bit more than extra speed: There were discussions of replacing the 16-inch/45 caliber Mark 6 of the South Dakota class by the new, heavier 16-inch/50 caliber Mark 2 which were an old design inherited from the canceled Lexington-class battlecruisers and first South Dakota class battleships. The projectiles were much heavier and potent than the 16-in/45, but this traduced in an additional 400 tonnes for each triple turret, larger barbette (39 feet 4 inches versus 37 feet) and in the end a global increase of 2,000 long tons for the main battery alone, reaching now 46,551 long tons.

The Bureau of Ordnance preliminary design however, gave the Board some home, with the guarantee a large turret could still use for loading the 45-caliber gun turret’s barbette. To chase extra weight and save 1,500 tonnes, it was decided to play on lower armor thickness in some places. But the most important move was to use, like for the Essex class carriers, a new construction steel using Special Treatment Steel (STS) in certain areas. It acted as a structural armor. All this enable to lower the displacement down to 44,560 long tons standard. That’s the General Board looked at on 2 June 1938.

The “stretched South Dakota”. Comparison between the three classes

Work went on with the Bureau of Ordnance being allocated the turret design with a larger barbette, while C&R worked on the smaller barbette option. However without communication between these entities, a reunion in November 1938 about the contract design shown that the larger barbette would required too much alterations to the North Dakota basic design as a starting base. At the same time the board was adamant not return to the 45-caliber was acceptable.

Before this new challenge, it’s again the Bureau of Ordnance that broufght up an elegant solution: In between, they had been working on a new 50-caliber gun called Mark 7, lighter and smaller. This enabled the same diameter as for the 45 caliber. This made them small barbette compatible, and thus, both the North Carolinas and South Dakotas could be in the future upgraded to the new 50 caliber gun as well without much trouble.

The new turret with this lightweight Mark 7 gun saved a total of 850 long tons (864 t) total, enabling again some extra room for future weight increase, while stil treaty bound by 1938. At last the latest contract design stated a 45,155 long tons (45,880 t) standard displacement estimated to reach 56,088 long tons (56,988 t) fully loaded. Based on the second Vinson act, President Franklin D. Roosevelt was able to program and fund the construction in June of the new Iowa class battleship at an estimated US$100 million unitary cost.

Final design at New York Navy Yard

The contract design was finalized gradually and blueprints generated in the New York Navy Yard which was the lead shipyard. Revisions included:

-New foremast design (notably stronger to fit future radars)

-1.1-inch (27.9 mm)/75 AA “Chicago Piano” by 20 mm (0.79 in)/70 caliber Oerlikon plus 40 mm/56 Bofors

-Moving the combat information center (CiC) further down into the armored hull.

-Comprehensive redesign of the internal subdivision of the machinery rooms based on tests:

> Longitudinal subdivision doubled with 50% less flooding risk and less uptakes in the third deck.

-Beam enlarged by a foot due to this (0.30 m) at 108 feet 2 inches (32.97 m) overall, still panamax, but now reaching 45,000 tonnes again.

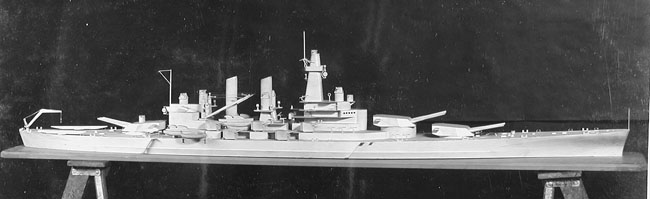

Photo by Norman Friedman via navsource.org of the Iowa model. It had a hull slot fared over when built prewar 12-foot navigational range finders, range clocks, pair of boat cranes never fitted, boat stowage replaced by three quad Bofors.

It should be recalled that it did not mattered much by the time: Both Britain and France renounced in turn the Second London Naval Treaty as WW2 started, and design displacement could not slip to 45,873 long tons (46,609 t) standard without causing a stir, which was still about 2% overweight. Now compare this to Bismarck and Yamato… The keels of both USS Iowa and New Jersey were laid down in June and September 1940, and as planned, a radical increase in anti-aircraft armament and extra splinter protection, more crew accommodations, heavier and more numerous additional electronics resulted in a new figure by 1944-45 of 47,825 long tons for 57,540 long tons (58,460 t) fully loaded. This would change again during their cold war career.

Detailed Design

Hull Construction

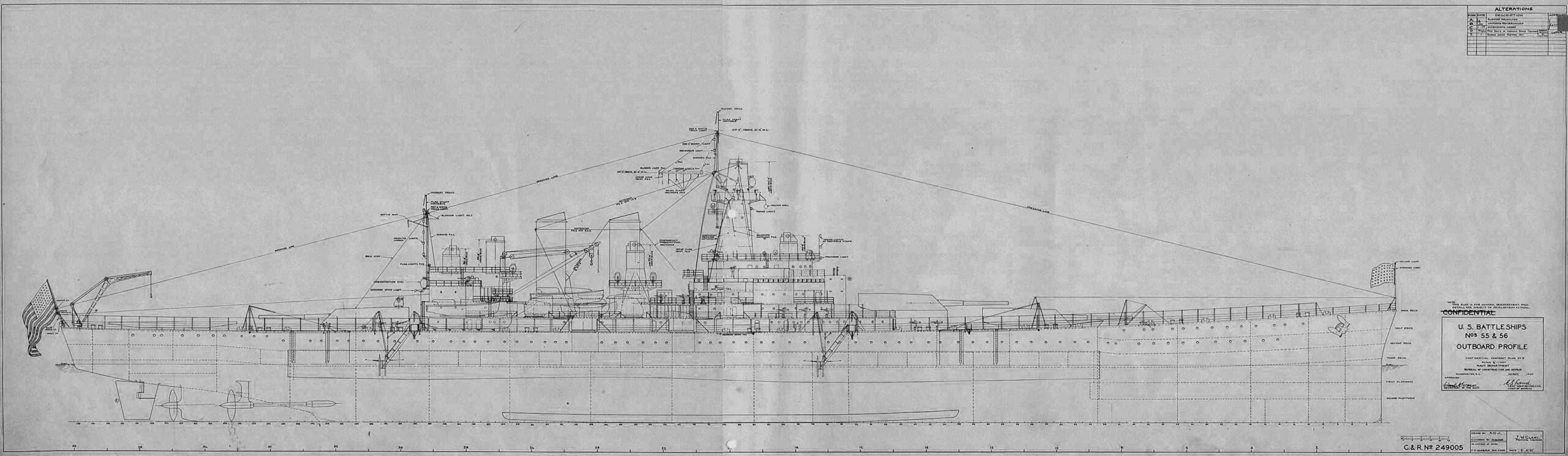

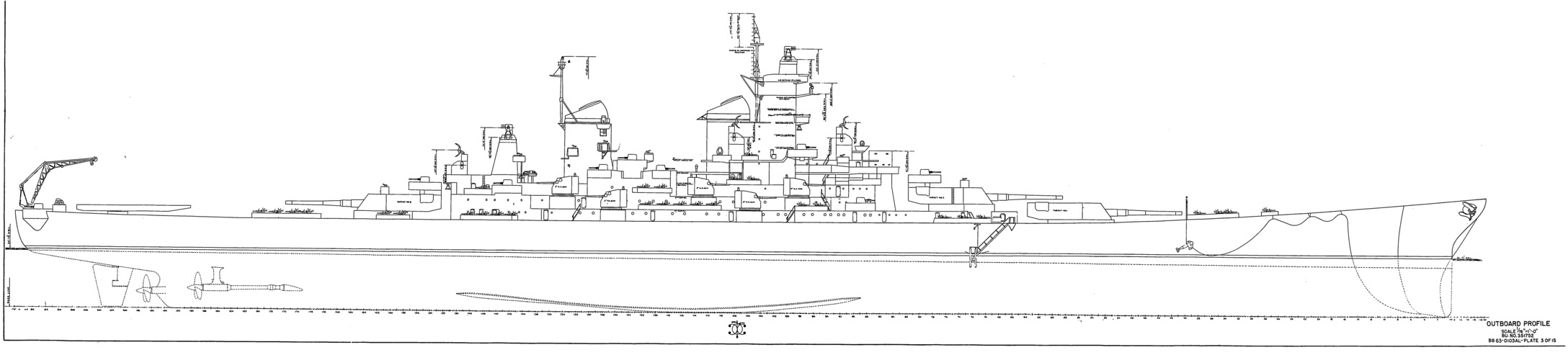

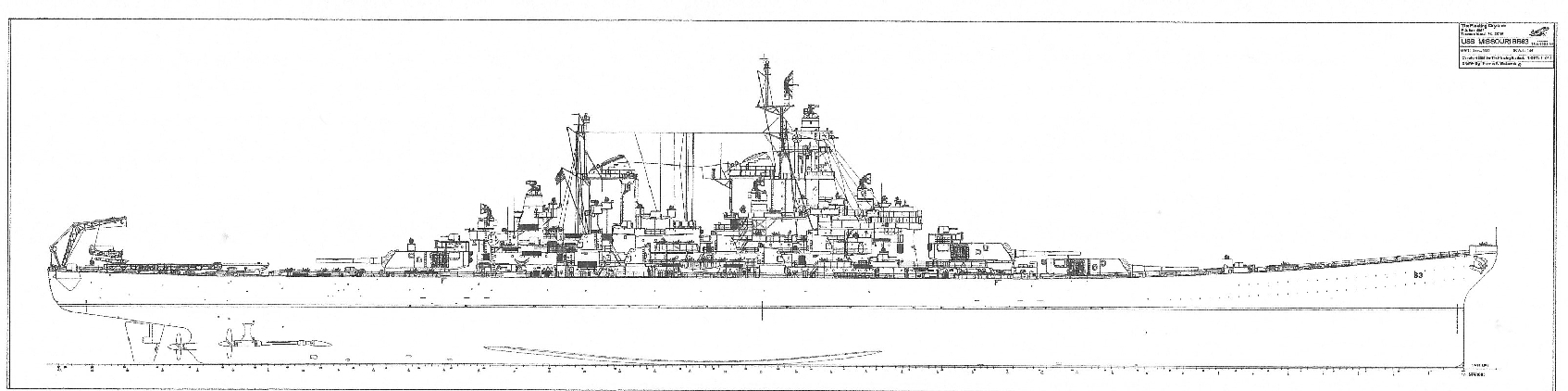

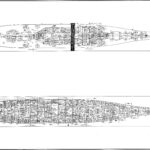

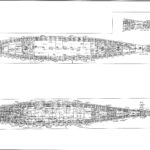

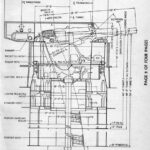

Missouri plans. Note, all original blueprints are kept by the Library of Congress, accessible here.

Based on the latest design idea, which was to simply stretch out a South Dakota, design was quick to adapt and refine, allowing to spare perhaps six month of new calculations.

Hull design

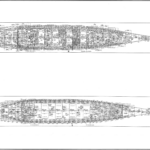

Seen from above, the three battleships, sharing the same panamax beam, the family traits are obvious. All three shared the same hull design, almost rectangular for the amidship sections, with some flare at the bow and rounded stern. Flat sides, internal armour, and flush deck, gradually going up for an entire level, were all common traits.

Superstructures

The silhouettes however shared little in terms of superstructures, apart the location of the three turrets. The exhausts were truncated with wildly different funnel designs: Two narrow funnels close apart for the North Carolinas, single large funnel for South Dakotas and two large ones far apart for the Iowas. However the superstructures of the Iowas had much more in common with those of the North Carolinas. Indeed, they were simply copied, notably for the main tower design, stronger, taller and roomier than than of the North Carolinas.

The space in between the forward bridge tower and aft one was massively stretched out. But the amidship deck design was about the same. Indeed, instead of just five twin turrets at least two more could have been crammed either side. This was not done as for again, design simplification and the extra space allocated to more quad 40 mm Bofors mounts, which took about the same space but were lighter and can be positioned higher up.

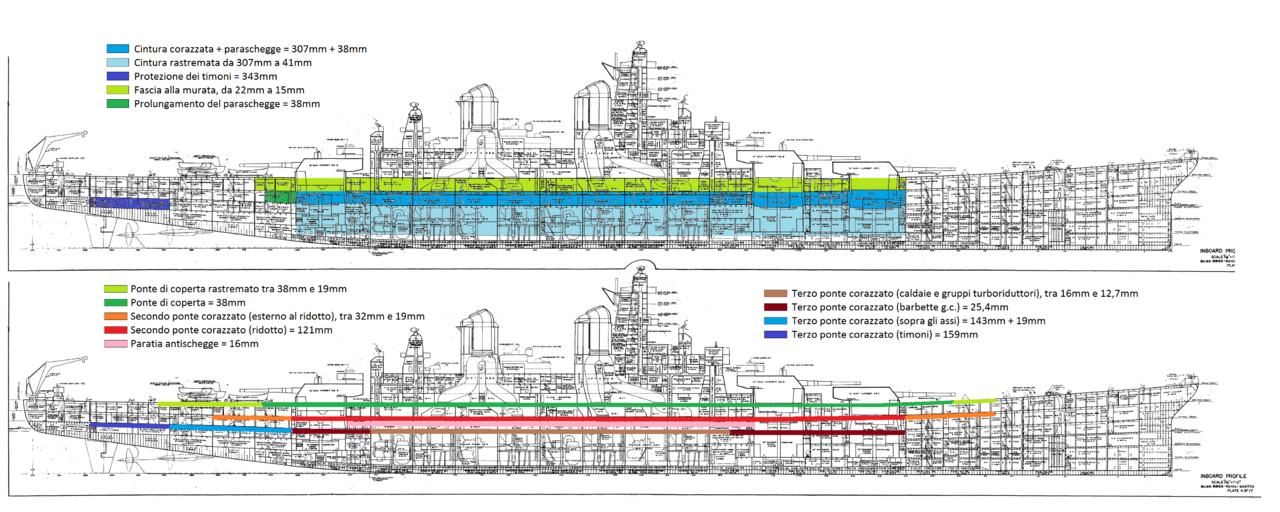

Armour scheme

The Iowa class went on with the tradition of “all-or-nothing” armor scheme inaugurated on the standard battleships of pre-WWI, and continued on by the South Dakota class, which perhaps had the best protection of any US capital ship to date. This protection was designed for full immunity against plungin fire (16-inch/45-caliber guns) at a particular distance set: Between 18,000 and 30,000 yards (16,000 and 27,000 m; 10 and 17 mi). At the time, the Krupp Cemented armour was the best process available for the time, and a Class A face-hardened K.C. armor as well as Class B homogeneous KC were used throughout, the remainder being protected by the newly developed special treatment steel (STS). This high-tensile structural steel was comparable to Class B and found its way onto the hull plating, creating with inferior thickness, another layer of protection.

Citadel

The citadel, ie the unsinkable “raft”, buoyancy reserve at the center of the ship, consisted of magazines and engine rooms, both under STS outer hull plates 1.5 inches (38 mm) thick, and behind the refular Class A armor belt. For the bulkheads, they diverged between the Iowa and New Jersey and the Missouri and Wisconsin. This protection against raking fire ahead was considered almost overkill due to their top speed. The main difference overall with the previous South Dakota, apart the longer citadel, was that armor was installed while in early construction and prior to the launch, since the STS notably was part of the structure. In general, the immunity zone was still good against 16-in/45 shells, but far less against 16-inch/50-caliber, especially with the Mk. 8 armor-piercing shell (“heavy shell”) compbining greater muzzle velocity and better penetration. The General Board just hoped the Japanese were not going to take that path. The Nagato class 41cm (16.1 in)/45 were considered inferior, the Yamato were unknown, and perhaps only the new Sovietsky Soyuz class battleships 406 mm/40 B-37 guns came close.

-Magazine, Engine rooms: 1.5 in (38 mm) STS plating

-Main armor belt, citadel: class A 12.1 inches (307 mm) thick + 0.875-inch (22.2 mm) STS back plating

-Internal sloping main belt 19 degrees, equivalent 17.3 in (439 mm) class B (from 19,000 yards).

-Lower belt to triple bottom: 1.62 inches (41 mm).

-Armored citadel transverse bulkheads: 11.3-inch (287 mm) Class A. (batch 2 14.5 in (368 mm))

-Weather Deck armor: 1.5-inch-thick (38 mm) STS

-Main armor deck: 6-in (152 mm) Class B + STS

-Splinter deck: 0.63 in (16 mm) STS.

-Magazines (third deck): 1-inch (25 mm) STS

-Wall between the magazine rooms and turret platforms: 2x 1.5-inch STS bulkheads under barbettes

Main Battery Protection

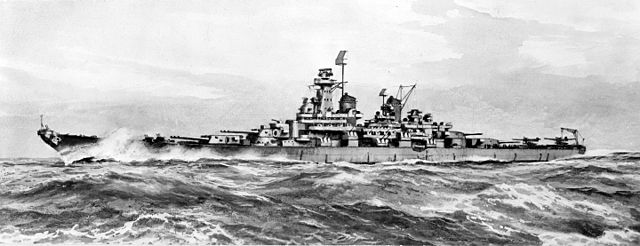

ONI recoignition drawing

The Iowas had larger turrets, and they were as heavily protected:

Faces: 19.5-inch (495 mm) Class B + STS

Sides: 9.5-inch (241 mm) Class A

Rear: 12-inch (305 mm) Class A

Roof: 7.25-inch (184 mm) Class B.

-Barbettes: 17.3 inches (439 mm) Class A abeam and 11.6 inches (295 mm) inwards, down to the main armor deck.

Secondary Battery and others

The conning tower has been put into question (it was eliminated from cruisers) but was maintained with walls 17.3 inches (439 mm) class B anf topped by a 7.25 inches (184 mm) roof.

The secondary battery turrets and the handling spaces below received 2.5 inches (64 mm) STS.

Propulsion shafts, steering gear compartment: 13.5-in (343 mm) Class A sides, 5.6–6.2-in (142–157 mm) above.

Iowa class ASW protection

The Iowa class torpedo defense was a repeat of the South Dakota design. A few modifications were made however to adress some issues detected during caisson tests. It was basically an internal “bulge” composed of four longitudinal torpedo bulkheads, behind the outer hull plating. This internal sandwich was 17.9 feet (5.46 m) in depht, spending the energy of any known torpedo warhead.

Armor belt also went down to the triple bottom reaching 1.62 inches (41 mm), becoming one of the torpedo bulkheads. Its joint was reinforced with buttstraps to compensate of the structural discontinuity. This internal bulge was designed to deform elastically in order to absorb energy: The the two outer areas dividied into many compartments were filled with liquid, either seawater or oil. Pumps and valves would be used for counter-flooding as well.

The liquid in any case was supposed to “eat” th einitial detonation blast energy and slowdown any splinters before hitting the lower armored belt. The fourth one was an empty compartment behind, destined to absorb remaining energy. Outside the citadel for the lower ones, they were used for extra storage but had all watertight roof apertures only, no side door, which could have weakened the internal wall.

Further improvements:

In between, Caisson tests went on in the Navy, and by 1939 the South Dakota’s scheme was found less effective than the North Carolinas’ due to the lower armor belt. It was too rigid and thus, had the explosion displacing the final holding bulkhead inwards. To fix this it was decided that both the third deck and triple bottom structure, behind the lower armor belt, would be reinforced, and brackets placement changed as well.

Thus, with a bit more time for polishing details, the Iowas’ ASW protection system was improved over the South Dakotas class, between modified transverse bulkheads, thicker lower belt at the bottom joint, and larger internal bulge overall. Built later, USS Illinois and Kentucky even had extra modifications, since it was decided to eliminat knuckles along certain bulkheads, improving the whole system to an estimated 20%. The Montanas would gave gained a relatively similar system, albeit even more refined, as well as the other unbuilt last two Iowa class. All in all, with the wartime freeing extra tonnage, it was decided to simple extened the citadel aft to included the steering gear and power control room, way aft of the ship. That was somthing completely new and ensure a greater level of survivability. This extra space beyond the barbette also included refrigerated compartments, fruits and vegetable storage room as well. This extra protected space also increased the buoyancy of the ship.

The question of aerial bombing:

About aerial bombing, notably from high altitude with AP bombs, some still had doubts about their capacity to withstand that kind of damage. It was compounded by the develomment of the Norden bombsight, fearing something comparable of the Japanese side, fortunately, not only this was too late to make any extra armor additions, bu the war proved time and again that high altitude bombing against capital ship was a phantasm, and in the end, largely ineffective against maneuvering warships.

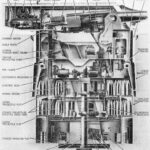

Powerplant

Main engine control room on USS New Jersey

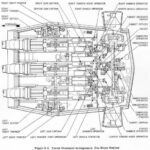

Main turbines

The Iowas class having more hull space was granted extra room for a far larger powerplant than its predecessors: It consisted of eight Babcock & Wilcox boilers feeding four sets of double reduction cross-compound geared turbines. Each turbine drove its single shaft. For comparison, it was the same on the South Dakota class: Four GE/Westinghouse steam turbines and eight Babcock & Wilcox three-drum express type boilers. But the output differed. For such contract, Iowa and Missouri also were provided their four geared turbines each by General Electric, and Westinghouse for New Jersey and Wisconsin.

They were protected by flooding in a new way, longitudinally divided into not four (South Dakota class), but eight compartments, alternating boilers and engine rooms. Indeed, this design incorporate larger turbines and the machinery space too more volume, hence reducing the useful beam for the ASW protection. This ensured that at worst a single torpedo could only disable 1/4 of the engine power. HP turbines were rated at 2,000 rpm and the shaft, through reduction gearing, went down to 225 rpm to the propellers but varied with the speed setup.

Boilers

Four “fire rooms” well separated by using the outer and inner turbines arrangements each housed two M-Type boilers. Their working pressure was 600 pounds per square inch (4,137 kPa; 42 kgf/cm2) and maximum superheater temperature being set at 850 °F (454 °C). These were of the same type as those on the South Dakotas.

The steam setup was directed by a mix for each set, of a high-pressure (HP) turbine combined with a low-pressure (LP) turbine in a 2-expansion system. The steam passes through the HP one at 2,100 rpm and whilst depleted, passes through the LP turbine, now at 50 psi (340 kPa). This was the most optimized way to deal with all produced steam. Leaving the low presure turbine, exhaust steam went to a condenser to be reciculated as feed water into the boilers. A closed loop which however imposed some additions from the internal waters tanks. But little was lost oustide leakage. Three evaporators producing some 60,000 US gallons daily or 3 liters per second were used to produced fresh water for the whole ship, also for the crew.

Performances

Despite similar configuration, this plant produced some 212,000 shp (158,000 kW) versus 130,000 shp (97,000 kW) on the South Dakota class. This explained the speed difference, also in part due to the better hull ratio. This enable the Iowa class a record 32.5 knots (60.2 km/h; 37.4 mph) fully loaded, and up to 33 knots (61 km/h; 38 mph) under normal displacement, not even “light” trials with minimum load (no ammo, food, water, reduced crew, and minimal oil). These kind of fancy speed trials were a peactime thing. We can only guess how these figures could have been outpassed, perhaps even 35 kts. After all, there was no governor.

To compare, this was about the same as the German Scharnhorst class, considered as “battlecruisers”. They were faster than the Richelieu (32), Litorrio (31), King George V (28), Yamato (28), and Bismarck (30). This was largely sufficient to deal with the Kongo class (30) anyway.

The range was also adequate for the pacific: They carried 8,841 long tons (8,983 t) of fuel oil. As a rsult, this gave them a calculated range of 15,900 nmi (29,400 km; 18,300 mi), at 17 knots cruise speed. As for agility, in addition to the outer propellers, steering counted on the two semi-balanced rudders. This enable a tactical turning diameter of 814 yards (744 m) at 30 knots, down to 760 yards (695 m) at 20 knots. Of course at 30-33, the Iowa class and their long gull bled more speed in hard turns than the South Dakota or North Carolina class.

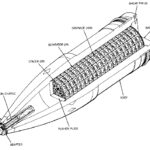

Propellers

The Iowas had four screw propellers: The outboard pair (4-bladed) were 18.25 ft (5.56 m) in diameter. The inboard pair (5-bladed) were 17 ft (5.18 m) in diameter, and more optimised for cruising. This different propeller design was adopted after comprehensive basin testing to evaluate the effect of propeller cavitation. There was a clear drop over 30 knots (56 km/h; 35 mph). The same studies went on improving the PT-Boats as well, as a completely different scale, and later cruisers of the Salem and Worcester class. The two inner shafts housed in skegs to blend into the hull and reduce the flow of water to the propellers. Thus also improved structural strength at the weaker stern.

Auxiliary Power

Electrical generators onboard USS New Jersey

In either of the engine rooms were installed a pair of 1,250 kW Service Turbine Generators (SSTGs). Each provided non-emergency electrical power, rated at 10,000 kW on 450 volts (alternating current). There were an additional, backup two 250 kW emergency diesel generators in case the main engines were all flooded, to at leat produce minimal power to lighting, pumps and save the ship. It was also envisioned a new redundancy in case of battle-damage: Electrical circuits could be more easily repaired or bypassed. The lower decks alsh had a “Casualty Power System” with a new set if three-wire cables and wall outlets usable to reroute power. These were the first time such baskup was setup. Indeed during the second battle of Guadalcanal in 1942, USS South Dakota was left without power, due to battle damage and technical error at the worst critical moment. This elactrical power had room to spare to add extra AA, and did not necessitated much change until 1945.

Armament

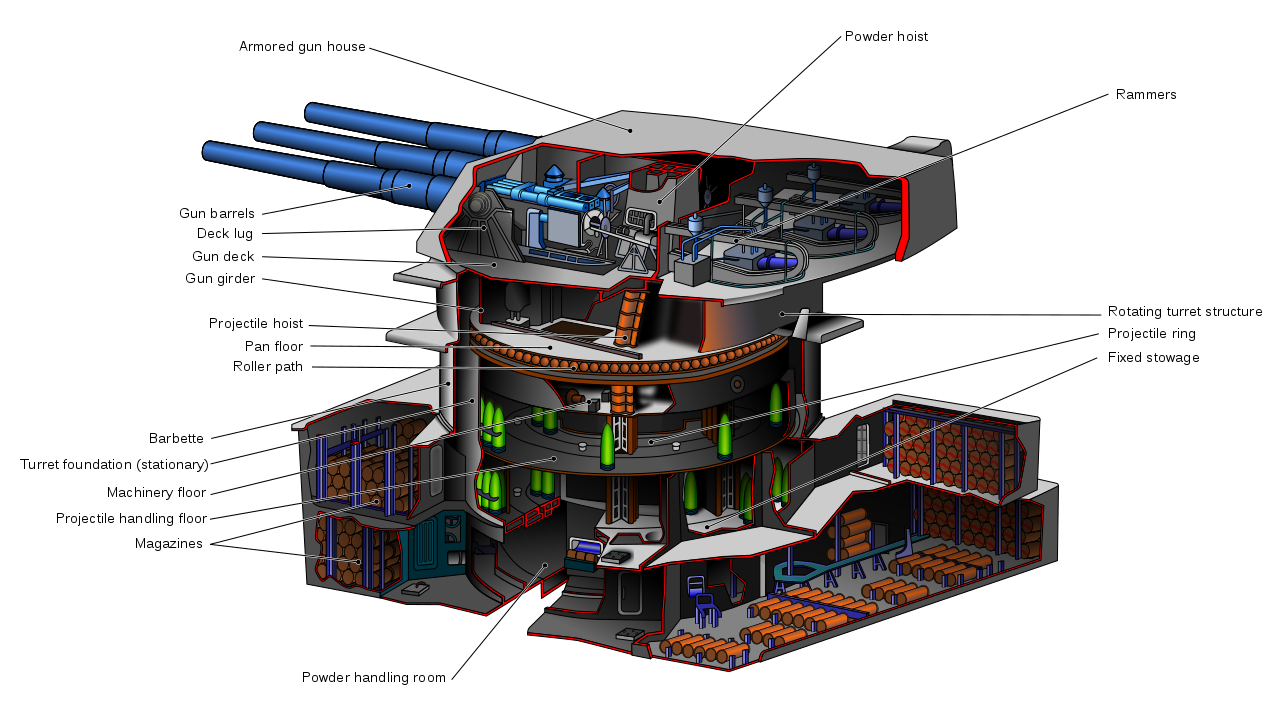

Main Guns: Nine 16-in Mk12

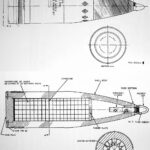

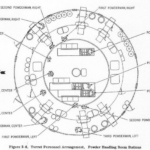

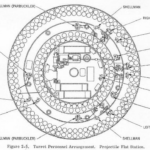

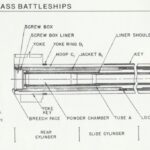

Iowa’s 16-in guns and barbette scheme

The 16-in/50 could claim the coveted claim of best naval gun of WW2 (and perhaps of all times since no battleship has been done since). The closest contender would be the British BL 15-inches Mk I naval gun, which however is older. Although it shared some caracteristics with the 45 caliber used on the previous North Carolina and South Dakota, it was tailored to fire a new shell, the “super heavy” 16-in AP which was though enough to defeat any known armor for a decade, but started completely different, to fire the relatively light 2,240 pound (1,016.0 kg) AP Mark 5 instead when preliminary studies started 1938. But in 1939 it was swapped for the “super-heavy” 2,700 pound (1,224.7 kg) AP Mark 8 before any battleship of the new class was even laid down. By performances, this made them equal or superior to the larger 46 cm (18.1″) Japanese (Yamato class) while being much lighter, a prowess which also saved time and energy to find comprises during the design phase of the new battleships.

With modern electronics during their cold war career they showed also an amazing accuracy in multiple occasions. The gun was designed and built in record time to equip the Iowa class when completed, in 1943. Each Mark 7 gun was composed of a liner and A tube plus its jacket and three hoops, two locking rings. The tube had its own liner locking ring as well as a yoke ring and screw box liner. The bore was plated over in chromium to extent its life. The breech was classic, using the Smith-Asbury Welin opening downwards.

The Mark 7 weighted 267,904 lbs. (121 tons including breech) while measuring 816 in (20.7 m) and had a rate of fire of 2 rounds per minute, with a muzzle velocity dependong on the round: AP Mark 8 – 1800 to 2,500 fps (762 mps), the former with reduced charge, and the HC Mark 13 between 2,075 and 2,690 fps (820 mps). Its approximate barrel life was 290 rounds and each gun was provided with 130 rounds. More refinement were made during the cold war and new shells introduced.

Loading the gun

Powder bags

Ammunitions: This gun fired the following:

-AP Mark 8 Mod 0-8: 2,700 lbs. (1,225 kg)

-HC Mark 13 Mod 0-6: 1,900 lbs. (862 kg)

-HC Mark 14 Mod 0: 1,900 lbs. (862 kg)

-Practice rounds Target Mark 9-16: 2700 or 1,900 lbs. (861.8 kg)

The AP Mark 8 carried a 40.9 lbs. (18.55 kg) warhead

HC Mark 13/14 carried the same 153.6 lbs. (69.67 kg) warhead.

The HE Mark 19 was a special “shotgun” round carrying 400 M43A1 grenades

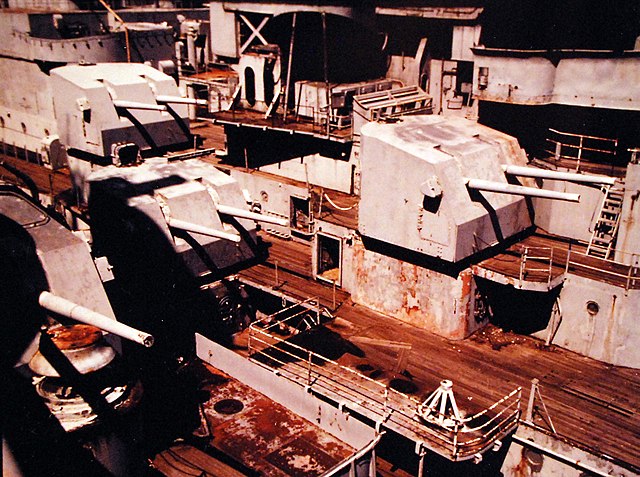

Secondary Guns: Twenty 5-in/38

The standard battery seen on the North Carolina and South Dakota class: Twenty 5 in (127 mm)/38 caliber Mark 12 in twin turrets. They were placed along the superstructure, in two rows and superfiring, alternated position to reach the best possible arc of fire at about 180° either side. This did not changed during WW2, albeit AA artillery did.

These turrets were of the Mark 28 Mod 2 twin dual-purpose mount type, weighting 56,295 lb (70,894 kg) and capable of −15 degrees to 85 degrees. They fired AA, illumination, white phosphorus shells for night fighting at 15–22 rounds per minute. The shell was quickly manually loaded, each weighting 54 and 55 lb (24–25 kg). They could be associated with full charge, a full flashless charge, and reduced charge. Depending on these, muzzle velocity of ranged from 2,500 to 2,600 ft/s (790 m/s). Each turret was supplied by 450 rounds and life expectancy of the barrels was 4,600 rounds.

They were all ten directed by four Mark 37 fire control systems through remote power control (RPC).

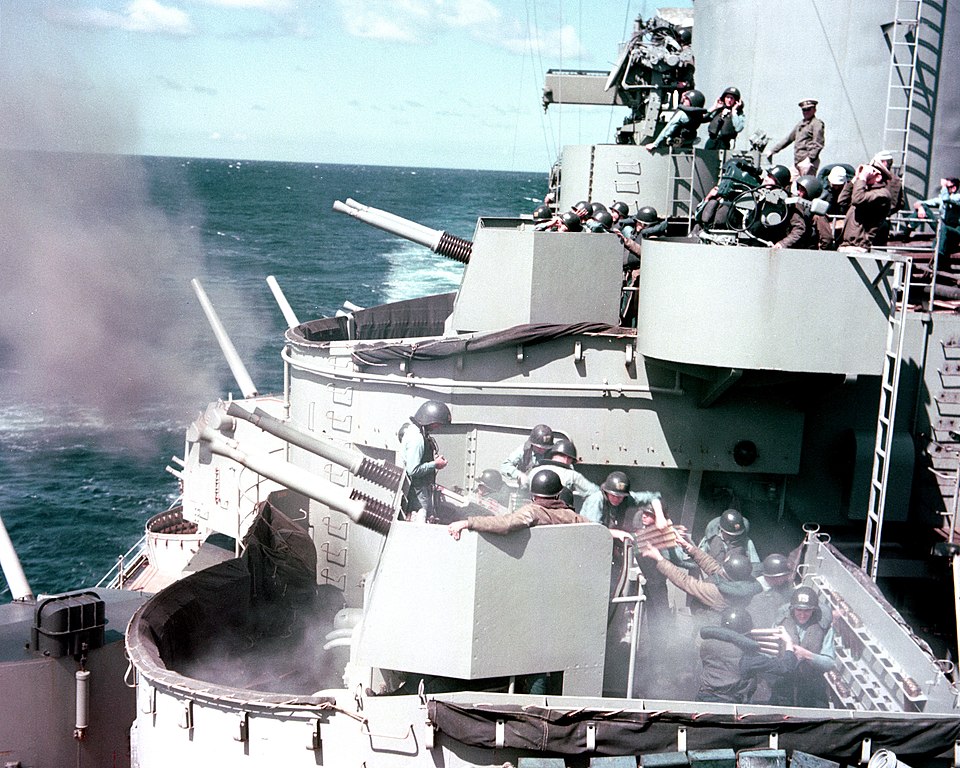

AA Guns: Eighty 40mm/70

The Iowa class came out with fifteen quad 40mm/56 Mk 1/2 for USS Iowa herself, twenty for her sisters, posted, from bow to stern, two on either side of the footbridge on sup. deck, one optional on B turret, two upper in the bridge, six at different levels close to the aft funnel, two at the superstrcture’s end, one on X turret, and two at the bow. However Iow soon obtained four more to reach the same total as her sisters, with little changes over time. In 1946 they swapped for the 40mm/60 Mk 2 model, and kept them in the 1950s, but they dwindled down until 1955. After the great refits of the 1960s-80s, they completed disappeared while secondary 5-in/38 were redyced to three turrets either side. (this will be more detailed on the cold war article).

AA Guns: Fifty 20mm/70

USS Iowa was planned and completed with fifteen quad 40mm/56 Mk 1.2 (60), and the same number of 20mm/70 Mk 4 Oerlikon. On BB 62, 63 New Jersey & Missouri, this was ported twenty quad 40mm/56 Mk 1.2 (80) and forty-nine 20mm/70. In 1944 the potency of the Bofors on the Oerlikon was recoignised already. BB 64 Wisconsin had an interesing mix of twenty quad 40mm/56 but also two twin 20mm/70 Mk 4 AA guns and the same forty-nine dingle mount Mk 4. By late 1945, New Jersey, Missouri and Wisconsin had their light AA reduced to just 17 single 20mm/70. In 1946, they all retained 20 quad Bofors. This was comparable to the North Carolina (24 at best) or South Dakota class (18 at best), thanks to their largest deck surface.

Electronics

Radars:

The earliest search radars on USS Iowa as completed were the SK air-search radar and SG surface-search radars in 1943. The first was on the mainmast’s top and the other on the forward fire-control tower. The first was later replaced by the SK-2 air-search radar and a modified version of the SG surface-search radar. Of course, these models were again upgraded between 1945 and 1952 while a SP height finder was placed on the main mast.

Typically they carried in 1943-44 the following: One SK, Two SG, One Mk 3, two Mk 8, four Mk 4 FCS radars. BB 63 and 64 were completed with a Mk.27 instead of the Mk.3, and four new Mk 12.22 radars for BB 64 as completed.

In 1945, modifications were extensive, with the adoption of the SC-2, SK-2, SP, SU, two Mk 13, four Mk 12.22 FCS radars, Mk 27 radars, and the TDY ECM suite for USS Iowa (March). By 1946 the usual set was one SK, two SG, one SR, two Mk 13, one Mk 27, four Mk 12.22 radars and same TDY ECM suite.

In 1952, AN/SPS-10 surface-search radar and AN/SPS-6 air-search radar replaced the SK and SG radar systems, respectively. Two years later the SP height finder was replaced by the AN/SPS-8 height finder, which was installed on the main mast of the battleships.

Fire control radars:

-As commissioned, two Mk 38 gun fire control systems (FCS), with Mark 8 FC radar for the main battery.

-Four Mk 37 gun FCS with Mark 12 FC radars plus Mark 22 height finding radar (HFR) for the secondary (5-in) battery.

-Upgrades: Mark 13 instead of the Mark 8 for the main battery, Mark 25 instead of the Mark 12/22 for the secondary battery. Despite their age, they remained active with few electronics improvements for the whole career of theese ships.

These were perhapos the most advanced FCS of their day, with a range estimation prividing a clear accuracy advantage as shown during the engagement off Truk Atoll (16 February 1944), USS Iowa straddling out IJN Nowaki at 35,700 yards (32.6 km; 17.6 nmi) a record for the time.

Electronic Countermeasures

Electronic countermeasures (ECM) was installed indeed at the end of the war for the first time, including SPT-1 and SPT-4 equipment, for passive ESM, with two DBM radar direction finders, three intercept receiving antennas to detect the radar source. The more active TDY-1 jammers were installed on either side of the fire control tower. Postwar they were among the first to receive the Mark III identification, friend or foe (IFF) system, then Mark X in 1955.

Onboard aviation

Vought OS-2U Kingfisher, USS Iowa 1944

Curtiss SC-1 Seahawk, VO1b, USS Iowa 1948

When first commissioned the Iowa-class battleships came with two aircraft catapults aft like previous designs, served by an axial crane. Initially plans were to adopt the Curtiss SOC-3 Seagull, but its poor performances meant it was replaced outrugh when commissioned with the Vought OS2U Kingfisher. In 1945 was adopted in replacement the smaller, faster Curtiss SC-1 Seahawk. They were used for artillery spotting but were used in between for search-and-rescue missions, saving the life of numerous aviators, notably when covering TF 38/58 in air raids. They were used despite better fire control systems now assisted by radars.

The early cold war saw the Seahawk still in use at least until 1947-48, but catapults were removed, freeing space used as a helicopter spot, the real revolution of the Korean War.

SC-1 Seahawk taxiing up to sea-sled, USS Iowa, July 1947

Crew, Stats, and other specifics

Port view of the Bridge

Flying bridge of the USS Missouri

Crew members painting the starboard anchor.

-The two anchors were of stockless bower type, 30,000 pounds. The chains counted “12 shots” (1,080 feet long) with the outboard swivel shot, 110 pounds for each link.

-Construction cost for each ship in 1940 was $90,000,000.

-Tank Capacity: 2.2 million gallons, fuel oil.

-Aviation gas. cap. 37,000 gallons of aviation fuel.

-Fresh water: 210,000 gallons with boilers recycled feed.

-All urinals and all but toilet on the Iowa class was flush with saltwater.

-Four meals were served, breakfast, lunch, dinner, and mid-rats (midnight)

-Two free service ice-cream machines

-834 tons of food stoared aboard for each long terme sortie

-7 tons daily consumed, fresh food (1.5t), frozen (2t) dry (3.5 tons).

-119 days at sea possible before resupply for food alone, not fuel or ammo

-Tailors, cobblers, barbers a board

-Fully wirking printing shop for the ship’s journal

-Library and Oratory

-Medical facilities: Dentist and full hospital

-Post office on 2nd Deck.

Gallery

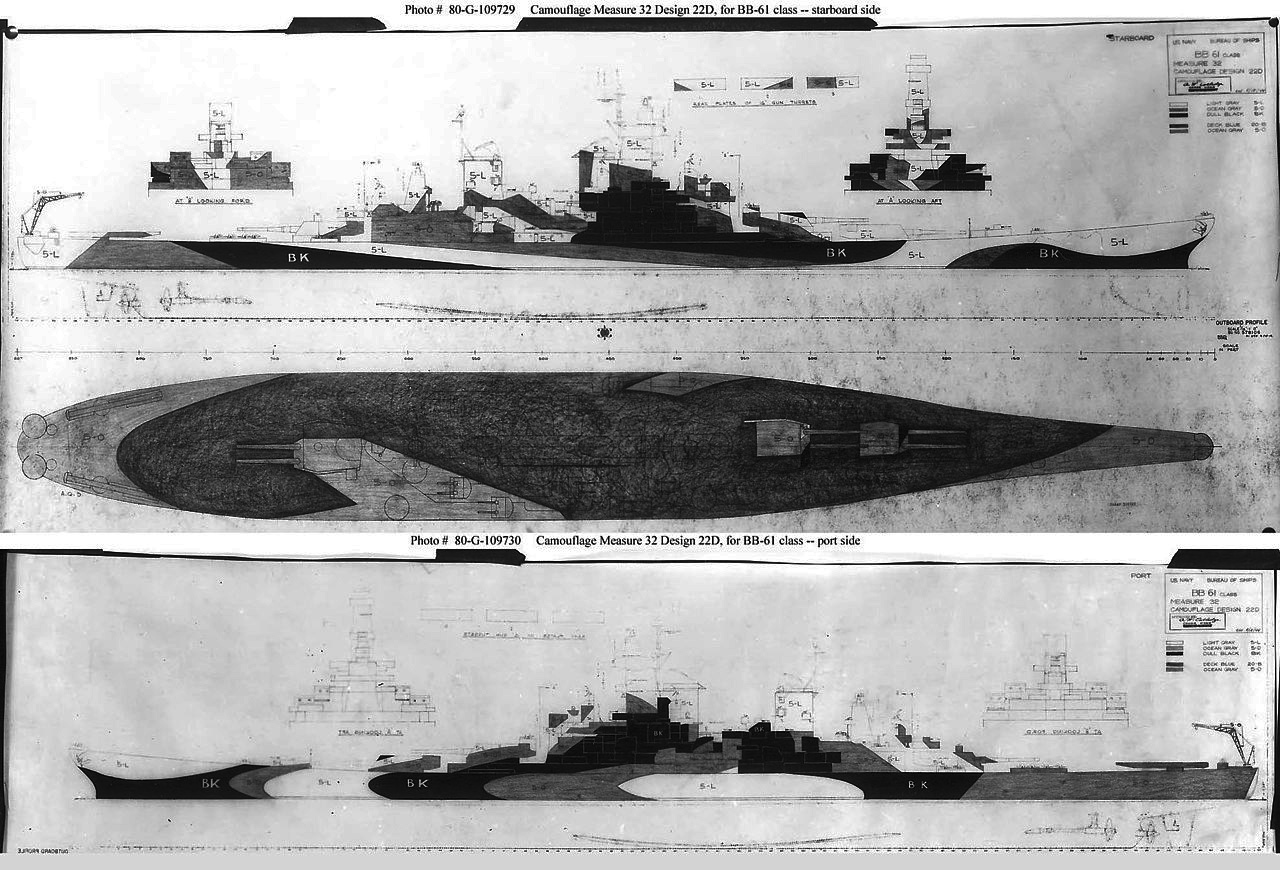

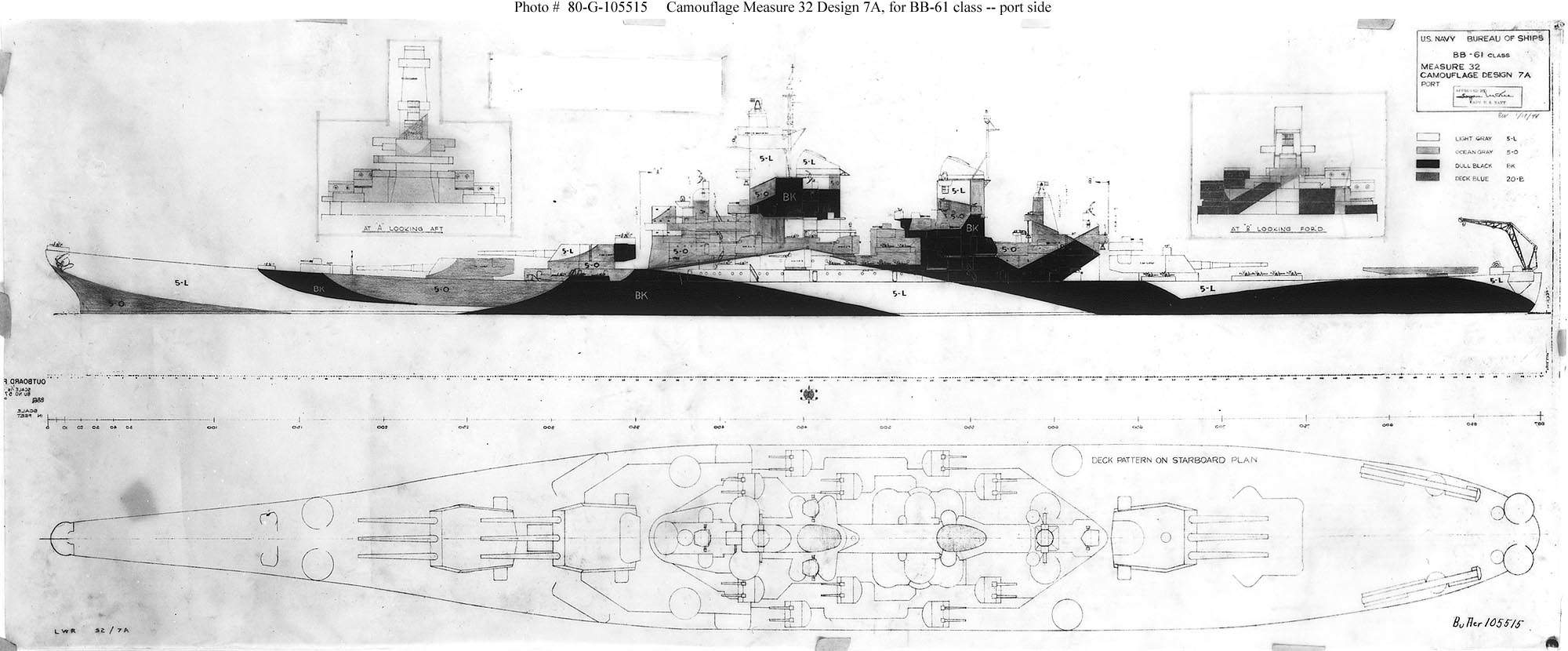

Standard camouflage scheme for the Iowa class in 1944.

Measure 32 Design 7a

16-in guns barrel elevated

Old author’s illustration of the Iowa

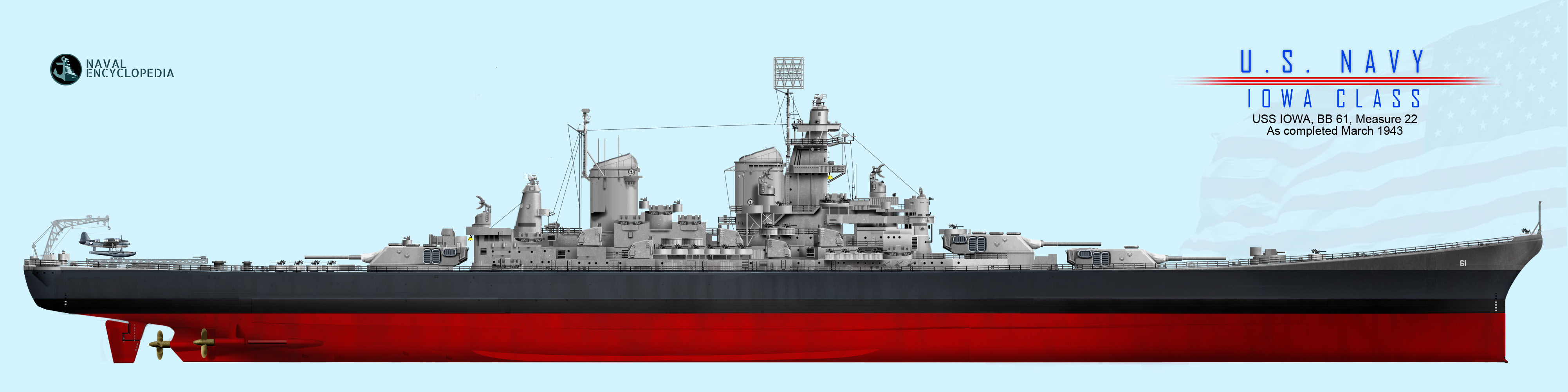

Iowa in March 1943

USS Iowa with her unique Measure 32 camouflage, Philippines sea, December 1944

USS Missouri 1944

USS Iowa (1943) specifications |

|

| Displacement | 48,110t standard, 57,540t fully loaded |

| Dimensions | 262,1 wl/270.4 oa x 33 x 11m (887 x 108 x 38 ft) |

| Propulsion | 4x sets GE geared steam turbines, 8 B&W boilers 212,000 shp (158,000 kW) |

| Speed | 35.2 knots on trials (65.2 km/h; 40.5 mph), 33 kts as designed |

| Range | 14,890 nmi (27,580 km; 17,140 mi) at 15 knots (28 km/h; 17 mph) |

| Armament | 3×3 406mm/50, 10×2 127mm/38, 15-20×4 40mm AA, 60x 20mm AA, 2 catapults, 3 seaplanes |

| Armor | Belt: 307+22, main deck 178, bulkheads 287, barbettes 439, turrets 495, CT 440mm, see notes |

| Crew | 2,700 (WWII and Korea) |

The Iowa class in service

USS Iowa (BB 61)

USS Iowa (BB 61)

Built at the New York Naval Yard from 27 June 1940 to launch on 27 August 1942, she was completed and commissioned on 22 February 1943. After sea trials, she started her shakedown cruise and service with the Atlantic Fleet on the 24th, starting with the Chesapeake Bay, along the coast. She stopped in Argentia on 27 August in case the KMS Tirpitz made a sortie in the North Atlantic from Norway to prey on convoys.

On 25 October she was in maintenance at Norfolk NyD for post-cruise fixes. Next, she became the “presidential yacht”, carrying President Franklin D. Roosevelt to the Cairo and Tehran Conferences, fitted with a tailored bathtub as the president could not use a shower.

The staff also comprised Secretary of State Cordell Hull, CiC Admiral William D. Leahy and General George C. Marshall, CNO Ernest King, and for the Air Force Henry “Hap” Arnold plus Harry Hopkins. They landed at Mers El Kébir in Algeria on their way to Tehran escorted by the destroyer USS William D. Porter, known for its torpedo drill that turned into near catastrophy when a nactual loaded torpedo was sent into the path of USS Iowa, which was warned at the last minute and turned hard. Sje trained her main guns on William D. Porter in case…

Iowa completed her votage on 16 December back home. Roosevelt addressed the crew by stating it appeared Iowa was to him a ‘happy ship’ and wished the crew good luck.

USS Iowa in late 1943

Pacific Service

USS iowa became flagship of BatDiv 7 (Admiral lee), departing on 2 January 1944 via the Panama Canal to join the Marshall Islands compaign. Until 3 February she escorted TF 58 for their air strikes under RADM Frederick C. Sherman’s TG 58.3 focusing on Kwajalein and Eniwetok. Next, she accompanied carriers assaulting Truk in the Caroline Islands. She was however detached with other battleships on 16 February 1944 to prey on Japanese shipping around Truk, notably on their northern retreat path. With USS New Jersey, she sank the Japanese light cruiser Katori fleeing after Operation Hailstone. One of the rare surface engagements of these battleships.

On 21 February she was now part of TF 38 (renamed TF 58, 5th Fleet) for operations against Saipan, Tinian, Rota, and Guam, in the Marianas. On 18 March 1944, USS Iowa as flagship of Admiral Willis A. Lee, shelled Mili Atoll (Marshall). In return she was hit by two Japanese 4.7 in (120 mm) shell, with little damage. Back in TF 58 on 30 March 1944 she covered new air strikes (Palau-Woleai).

Until 28 April, she escorted the carriers hitting Hollandia, Aitape, Wake in support of landings in Aitape and Tanahmerah, New Guinea. Next this was the second Truk raid on 29-30 April, then Ponape (Carolines) on 1st May.

New strikes followed on Saipan, Tinian, Guam, Rota, and Pagan Island, on 12 June and she was detached to shell IJN installations on Saipan and Tinian (13–14 June).

Battle of the Philippine Sea, Leyte, and Campaign

USS Iowa in 1944

On the 19th June she took part in the Battle of the Philippine Sea as part of TF 58 escort, put her AA to good use by repelling four massive air raids, claiming three enemy aircraft alone, many more assisted. She was part of the pursuing fleet claiming a torpedo plane and assisting another. In July, she covered other raids off Marianas, notably landings on Guam. She left Eniwetok with the 3rd Fleet and covered the landings on Peleliu (17 September). Next, she covered more raids in the Central Philippines before the invasion. On 10 October she was off Okinawa for air strikes on the Ryukyu Islands, Formosa (Taiwan). She was back for raids against Luzon (18 October) and until MacArthur’s landing on Leyte two days later.

Then came Operation Shō-Gō 1, a last ditch attack by three fleets which became the Battle of Leyte at large. Iowa escorted TF 38 attacking Japanese Central Force (Admiral Kurita) going through the Sibuyan Sea. The fleet was attacked, and retreated, which left Admiral William “Bull” Halsey to send Iowa and other ships with TF 38 in hot pursuit of the Northern Force retreating from Cape Engaño. On 25 October 1944, as this retrating fleet came into range Iowa’s guns, it was learned the Central Force was just falling on Taffy 3 off Samar. TF 38 was forced to reverse course, but the 7th Fleet resisted fiercely forcing the Japanese to retreat before they could be met by Halsey and his battleships. The great showdown of capital ships was avoided there. Iowa remained afterwards in the Philippines to cover more strikes against Luzon and Formosa.

However on 18 December, TF 38 was hit by Typhoon Cobra while 300 mi (480 km) east of Luzon. The core of the storm came with little warning and the task force was caught pants down with many destroyers ttrying to refuel from larger ships. Hurricane-force winds claimed USS Hull, Monaghan, and Spence, damaging a cruiser, five aircraft carriers, and three more destroyers, 790 officers and men lost as well as 146 planes. Iowa reported no injuries, biut lost her Vought Kingfisher, washed overboard, and had a shaft damaged. This required her bacl to the US after some hasty repairs in a floating drydock. She was back in San Francisco on 15 January 1945. The overhaul Iowa saw her bridge enclosed, addition of AA, new search radars and fire-control.

Last Operations against Japan

USS Iowa in repairs, floating drydock ABSD-2 in Manus, admiralty Islands, 28 December 1944

Iowa was back at sea on 19 March 1945, bound for Okinawa (15 April), relieving sister ship New Jersey as flagship. From 24 April, she supported carrier operations there. She went on with TF 58 for strikes off southern Kyūshū (25 May-13 June) on the Japanese mainland. Next raids on northern Honshū and Hokkaidō and more striked on 14–15 July this time with direct shore shelling: She devastated Muroran Industrial complex in Hokkaidō. Hitachi (Honshū) was next in her scopes, between 17-18 July. She bombarded Kahoolawe on 29-30 July and escorted the last fast carrier strikes in early august until ceasefire orders were received on 15 August.

On the 27th, with USS Missouri (“Mighty Mo”) she entered Sagami Bay for the surrender of the Yokosuka Naval Arsenal, then Tokyo Bay assistined, with sailors from Missouri on her board to make room for numerous officials, for the surrender ceremony on USS Missouri. She was Halsey’s flagship for the surrender ceremony on 2 September and covered operations of the occupying force. Next, she took part in Operation Magic Carpet, with GIs and freed POWs aboard brought bacck home, departing Tokyo Bay on 20 September.

He cold war service will be seen in a later post.

USS New Jersey (BB 62)

USS New Jersey (BB 62)

USS New Jersey and Richelieu (bg) on 7 September 1943 off Hampton Road. The two fastest battleships at the time. Richeloeu just joined the allies, being refitted in New York, with New Jersey was brand new, commissioned in May.

Marshall Islands Campaign

USS New Jersey was Launched on 7 December 1942 at Philadelphia Naval Shipyard, commissioned on 23 May 1943. Her fitting out completed, she trained her initial crew in the Atlantic, making her first shakedown cruise in the Caribbean Sea. This process went on from May until December 1943. On 7 January 1944 she was assigned to the Pacific fleet, and went through the Panama Canal bound for Funafuti in Ellice Islands, arriving on the 22th. She was assigned to the Fifth Fleet, and met with Task Group 58.2 for the Marshall Islands Campaign. Like her other sisters her main tasks eere to screen aircraft carriers while TG 58.2 flew strikes against Kwajalein and Eniwetok until 2 February before the landings taking place on 31 January.

USS New Jersey became flagship on 4 February, while in Majuro Lagoon, varrying the mark of Admiral Raymond A. Spruance, 5th Fleet. She took part in Operation Hailstone, a massive attack on Truk Lagoon, Carolines. It went on at the same time as the assault on Kwajalein with the goal of achieving the conquest of the Marshalls. By 17-18 February, the raid claimed among others two Japanese light cruisers and four destroyers. USS New Jersey destroyed a trawler by gunfire and co-claimed the destroyer IJN Maikaze. She also claimed at least an enemy aircraft before being back in the Marshalls on 19 February.

On 17 March and until 10 April she stayed with USS Lexington(ii), RADM Marc Mitscher’s flagship during the attack on Mille, and joined TG 58.2 for a strike in the Palaus, also bombarding directly Woleai. Admiral Spruance left for USS Indianapolis and she sailed from Majuro on 13 April and until 4 May 1944 in another strike, returning to Majuro. These hit Aitape, Tanahmerah Bay and Humboldt Bay in New Guinea but also Truk again (29–30 April). She claimed two enemy torpedo bombers these days and shelled Ponape on 1 May.

Mariannas Islands Campaign

USS New Jersey shelling Tinian in June 1944

Before being prepared for the invasion of the Marianas, USS New Jersey on 6 June took part on Admiral Mitscher’s Task Force for preinvasion air strikes starting on 12 June, claiming an enemy torpedo bomber, bombarding next Saipan and Tinian to prepare for the landings on 15 June. The Japanese prepared massive counter-attack, their formations shadowed by US submarines into the Philippine Sea. Admiral Spruance and Admiral Mitscher gather their forces and went forward in interception. USS New Jersey opened fire on 19 June 1944 on the remaining Japanese aircraft that went through the massive USN air screen, part of the Battle of the Philippine Sea.

She played her part in the “Marianas Turkey Shoot”, the fleet learning that the IJN Taihō and Shōkaku had been claimed by USS Albacore and Cavalla, plus USS Hiyō bya aviation from USS Belleau Wood and two more Japanese carriers and a battleship damaged. USS New Jersey AA crews managed to shot down any aproaching aircraft before they could engage.

USS new Jersey’s AA was hard at work during the Battle of the Philippines sea.

Philippines Campaign

USS New Jersey crowned the Marianas campaign by strikes on Guam and Palaus before returning to Pearl Harbor (9 August). She became there flagship of Admiral William F. Halsey Jr. and on the 24th, flagship of the 3rd Fleet. On 30 August, she departed again to join Ulithi, her new advanced base for eight months of the Philippines Campaign. She escorted TF 38, the fast carrier task force on striked in the Philippines but also Okinawa, and Formosa. By September she escorted the force striking the Visayas, southern Philippines, Manila and Cavite, Panay, Negros, Leyte, and Cebu.

By October a sweep was done to hit Okinawa and Formosa while Leyte landings were prepared from 20 October.

This trigger the IJN’s last gamble. This almost succeeded as the northern force drew away Halsey’s force despite her was tasked initially to protect the landings. Center Force entered the gulf through San Bernardino Strait and fell on Taffy 3 protecting the landings. Halsey meanwhile reversed course, having sank by aviation four carriers, a destroyer and cruiser, New Jersey meanwhile rushed south to try to catch Center force, already defeat and retreated. Like Iowa, she was declined her duel with IJN capital ships.

USS New Jersey during a stiff storm in the Western Pacific, 8 November 1944

USS New Jersey was back in close protection of the fast carriers fleet near San Bernardino, on 27 October 1944. Dhe covered new striked on central and southern Luzon. Two days after a fierce Kamikaze attack followed, and USS New Jersey claimed a plane aiming for USS Intrepid. The carrier’s rounds landed by accident on USS New Jerdey, wounding three. On 25 November she claimed three more Japanese planes, one however hitting USS Hancock. Intrepid was jit by another kamikaze hit by New Jersey gunners. She did the same for anothers targeting USS Cabot.

On 18 December 1944, TF 38 was badly hit by Typhoon Cobra. As a fleet flagship, USS New Jersey had a highly experienced weatherman aboard, Commander G. F. Kosco from the MIT and expert on hurricanes in the West Indies, but he completely missed the signs of the sudden typhoon. The battleship was hit on 18 December, but New Jersey remained largely unscathed. She was in Ulithi on Christmas Eve, visited by Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz.

USS New Jersey from 30 December 1944 to 25 January 1945 accompanied carriers hitting Formosa, Okinawa, and Luzon, the Indo-China coast, Hong Kong, Swatow and Amoy, and again Formosa and Okinawa. Back at Ulithi on 27 January Halsey left New Jersey, replaced on the 29 by RADM Admiral Oscar C. Badger II, BatDiv7.

Iwo Jima and Okinawa

She was present for the attack on Iwo Jima, screeing CVs attacks on 19–21 February, and took part in the first major carrier raid on Tokyo 25 February, being attacked by air. She later was seen in the conquest of Okinawa (14 March-16 April). Her AA gunners did wonders to repel Kamikaze strikes, haing both seaplanes budy rescuing downed pilots. In all she claimed three assisting in many more.

On 24 March 1945 she was committed to heavy bombardment, on the invasion beaches. After this, she was sent home of a major overhaul at Puget Sound Naval Shipyard. This was over on 4 July as she departed for San Pedro, then to Pearl Harbor and Eniwetok, then to Guam, arriving on 14 August, as flagship of the 5th Fleet (Spruance). She learned the end of the war and went to Manila and Okinawa before heading for Tokyo Bay 17 September as flagship for successive commanders of the occupation forces until replaced on 28 January 1946 by USS Iowa. She took part in Operation Magic Carpet with circa 1,000 troops, landed at San Francisco on 10 February. She would be decommissioned in 1948. She earned 9 battle stars for her WW2 service, but will earn more in the future.

USS Missouri (BB 63)

USS Missouri (BB 63)

BB 63 was built at Brooklyn Navy Yard, laid down on 6 January 1941 and launched on 29 January 1944, christened by Margaret Truman, daughter of Harry S. Truman a senators from the namesake state. She was fitted-out work quickly, commissioned four month afterwards on 11 June with Captain William Callaghan in command.

After initial sea trials off New York from 10 July, she made a trip to Chesapeake Bay to starte her shakedown cruise whilst doing initialtraining, in company of the new “large cruiser” USS Alaska, and destroyers in case of U-Boats. Once done, she headed on 11 November via the Panama Canal to San Francisco. Fitting-out work, with post-fix maintenance were carried out at Hunters Point Naval Shipyard, notably to serve as fleet flagship.

On 14 December, she sailed from San Francisco to Ulithi, the gathering point for the fleet in the Carolines, meeting it on 13 January 1945. She became HQ for VADM Marc A. Mitscher and was assigned to Task Force 58 on its way on 27 January for a strike on Tokyo, in preparation of Iwo Jima’s future assault. As her sister she was tasked of AA screen duties as part of TG 58.2 (USS Lexington, Hancock, San Jacinto). She also resupplied her escorting destroyers as oilers were left behind.

From 16 February her units started operations off Kyushu before returning to Iwo Jima, which invasion started on 19 February. USS Missouri at her first evening shot down an incoming lone Japanese bomber (likely Nakajima Ki-49 Donryu “Helen”). TF 58 left the area in March to resupply in Ulithi while Missouri was reassigned to the Yorktown task group (TG 58.4) and was underway again from 14 March. On the 18th, the battleship claimed/co-assisted in downing four Japanese aircraft. During a massive Kamikaze counter-attack USS Franklin was badly damaged, Missouri being detached to cover her withdrawal. She was back on the 23-24 reassigned to the preparatory bombardment of Okinawa as part of TF 59 with her sisters USS New Jersey and Wisconsin. They rained steel on the southern coast of Okinawa on 24 March, diverting attention as the main landing was on the western side. She spent 180 rounds that day and returned in protection of TG 58.4.

On 11 April she repelled another kamikaze attack, but one wetn through and hit her side, below the main deck. A gasoline fire on deck rapidly ignited but was suppressed. Damage was light and she stayed on station. On the 17 another attack left two crewmen badly wounded after one Kamikaze exploded on the stern crane and ended on the wake. She returned with TF 58 to Ulithi on 5 May having 5-6 six aicraft kills and six assisted. On 9 May she left Ulithi for Apra Harbor in Guam arriving on the 18th, visited by William F. Halsey Jr. which made the ship his flagship for the whole TF 38.

On 21 May, she sailed back to Okinawa, arriving six days afte, and shelling positions around the island. She soon left for the north, covering more air strikes on Kyūshū (2-3 June). She went through a typhoon (5–6 June) largely unscaved. Operations resumed on 8 June and retired to Leyte Gulf (13 June). The fleet returned to the Japanese Home Island on 1 July, Missouri being integrated into 38.4. Attacks started on 10 July and went to Honshū and Hokkaidō on 13-14 July while on the 15 she left to join the detached TG 38.4.2 sent shelling industrial facilities in Muroran on the northernmost island of Hokkaido. A second mission was done in the night of 17–18 July with HMS King George V. Next they were back as carrier screens. This time for raids on and around Tokyo, later resuming attacks on northern Japan (9 August). The A-Bomb of Nagasaki, then second, and Soviet Invasion resulted in a reddition announced on 15 August.

For the next two weeks preparations commenced for the occupation of Japan and on the 21, Missouri sent 200 officers and men to USS Iowa, to form a large landing party, in Tokyo, at first tasked to find weapons and gathered them. Captain Murray was informed that his ship would host the surrender ceremony setup on 31 August. Crew started frantic preparations, including cleaning the decks and painting everything anew. “Mighty Mo” entered Tokyo Bay on 27 August, escorted by IJN Hatsuzakura. While in Kamakura a courier gave them the flag flew by Commodore Matthew Perry in 1853, displayed during the ceremony. On 29 August al ships had dropped anchor, Missouri symbolically close where Perry was 92 years prior. Poor weather had the ceremony pushed back to 2 September.

Admiral Chester Nimitz boarded BB 63 on the morning, with Gral Doug MacArthur as Supreme Commander a bit later, and Japanese representatives led by PM Mamoru Shigemitsu barel ten minites later at 08:56. MacArthur opened the 23-minute surrender ceremon with a well prepared discourse before the signing and by 09:30 Japanese emissaries departed. On 5 September, Halsey made USS South Dakota his new flagship and Missouri departed Tokyo Bay to take part in Operation Magic Carpet landing in Guam, and then Hawaii, on 20 September. Later she was made flagship of Admiral Nimitz on the 28th, for a vivtory reception. Later she would depart Pearl Harbor for the East Coast, New York City (23 October) as flagship Atlantic Fleet (Admiral Jonas Ingram), firing a 21-gun salute for Truman during Navy Day ceremonies. Soon after some cadet training she was sent in reserve. The rest of her career is truly amazing. For her service in WW2 she earned eight battle stars.

Battle Honors painted on her bridge, as preserved today.

USS Wisconsin (BB 64)

USS Wisconsin (BB 64)

USS Wisconsin completed her trials, initial training, both in the Chesapeake Bay before post-fixes and depart Norfolk on 7 July 1944 for the British West Indies. She made her shakedown cruise off Trinidad and returned to the yard for alterations. On 24 September 1944 she sailed for the West Coast via Panama and arrived in the Pacific Fleet on 2 October, hitting Hawaii for local training exercises before proceeding to the Western Caroline Islands, and dropping anchor at Ulithi to joined the 3rd Fleet, on 9 December, preparing for her first wartime mission, months after completion.

Philippines Operations

She was on time for the reconquest of the Philippines and was planned to cover landings on the southwest coast of Mindoro (Luzon) so she was assigned to protect the 3rd Fleet’s Fast Carrier Task Force or TF 38, launching raids over Manila and surrounding bases. On 18 December TF 38 was hit by Typhoon Cobra while trying to refuel at sea some 300 mi (480 km) east of Luzon. There was considerable damage on several carriers and several destroyers lost, but USS Wisconsin only had to report two injured sailors after the typhoon.

She next covered the occupation of Luzon, troops hitting Lingayen Gulf, while BB 64′ AA batteries watched over TF 37 launching air strikes against Formosa, Luzon, and Nansei Shoto in an attempt to destroyer Japanese air power there on 3–22 January 1945, including a sortie in the South China Sea.

New raids were done on Saigon and Camranh Bay in French Indochina and the raids claimed 41 Japanese ships, wrecking the docks port installations and destroying aircraft facilities around. Formosa was hit by six raids, the last on 21 January. Raids were also performed on Hong Kong, Canton, Hainan Island plus Okinawa. Afterwards, USS Wisconsin was reassigned to the 5th Fleet (Admiral Raymond A. Spruance) was the new commander. She covered TF 58 moving directly for raids on the Tokyo area. On 16 February, they arrived by heavy weather a achived surprise, launching devastating raids. During the air counter attack, USS Wisconsin and other escorts shot down altogether some 322 enemy planes (some claimed by fighters), while Helldivers and Avengers, Corsairs claimed 177 more on the ground. Japanese shipping was also crippled in the whole area and installations.

Iwo Jima and Okinawa

Wisconsin next moved with TF 58 to Iwo Jima, arriving on 17 February, this time leaving her main battery bark in anger in preparatory bombardment and direct support for the landings from 19 February. She left with TF 58 for more raids on 25 February, to Honshū before retiring for resplenishment to Ulithi on 14 March. Later southern Honshū was hit, Kure and Kobe devastated, leaving dozens of ships dead in the warer. On 18–19 March now just 100 mi (160 km) southwest of Kyūshū, TF 58 repeated air strikes in depth. However a vigorous Kamikaze attack left USS Franklin crippled. Whike USS Wisconsin’s AA barrels were cooling, the fleet retired, while repelling another Japanese attack with 48 Kamikaze.

On 24 March, Wisconsin started her first naval bombardment on the Japanese soil. She trained her 16 in guns on Okinawa. Japanese positions and installations in all marked areas for landings were reduced to rubble. Meanwhile, a last-ditch operation was underway, in which were committed the remnants of the IJN, notably the mighty battleship Yamato. However, none of the battleships ever had to be detached and seek combat with the giant, which was intercepted and dealt with by a deluge of ordnance from all the air groups sent.

Meanwhile though, there was anothr masive Kamikaze attack, for which the Combat air patrol shot down 15, the rest being dealt for close and personal by the massed AA gunfire. Still, one managed to crash on USS Hancock. On 11 April, Wisconsin and other units had to fend of other kamikaze attacks, which grew in numbers and intensity and reached a treshold, leaving the crew shaking. This time again, 17 were claimed by the CAP, 12 by ship’s AA. This was not the last though as another force of 151 Kamikaze hit TF 58, there again dealt for between the CAP and AA, radar helping. They still managed to hit USS Intrepid, Bunker Hill, and Enterprise along this period.

Last raids on Japan

By 4 June, TF 58 was hit by a typhoon -again- and again USS Wisconsin rode out the storm unscathed. Operations were resumed on 8 June on Kyūshū. Ny that time, Kamikaze missions were rare in between with all that was flyable to be mustered and thrown into the cauldron: 29 planes were dealt with. Wisconsin’s floatplanes rescued a downed pilot from USS Shangri-La also.

By 4 June, TF 58 was hit by a typhoon -again- and again USS Wisconsin rode out the storm unscathed. Operations were resumed on 8 June on Kyūshū. Ny that time, Kamikaze missions were rare in between with all that was flyable to be mustered and thrown into the cauldron: 29 planes were dealt with. Wisconsin’s floatplanes rescued a downed pilot from USS Shangri-La also.

Next, Wisconsin went to Leyte Gulf on 13 June for repairs and replenishment. On 1 July she was back in Japanese home waters for more carrier air strikes, with particular attentio to the Tokyo area. The fleet went even closer to shore since Japanese response was anemic.

On 16 July, USS Wisconsin at last fired her main battery directy at the steel mills and oil refineries at Muroran in Hokkaido. She also flattened industrial facilities in the Hitachi Miro area on Honshū and NW of Tokyo, joined also by British battleships of the BPF. After the aviation devastated Yokosuka and sunk Nagato the fleet was free to ream the coast unempeded, into August, the lat attack taking place on 13 August, and an attomic attack combioned with the Russian invasion of Mandchuria led the Japanese surrender on the 15th.

USS Wisconsin took her guard duties if the occupying force entering Tokyo Bay on 5 September to see her sister USS Missouri on which was signed the surrender earlier. It was time for assessment. Since departing home she had sailed some 105,831 mi (170,318 km) and claimed three enemy planes shot by herself, assited dozens others on four occasions. As usual practice she also her own screening destroyers some 250 times. Wisconsin earned five battle stars for her World War II service.

The unbuilt Iowas, 1940

USS Illinois (BB-65)

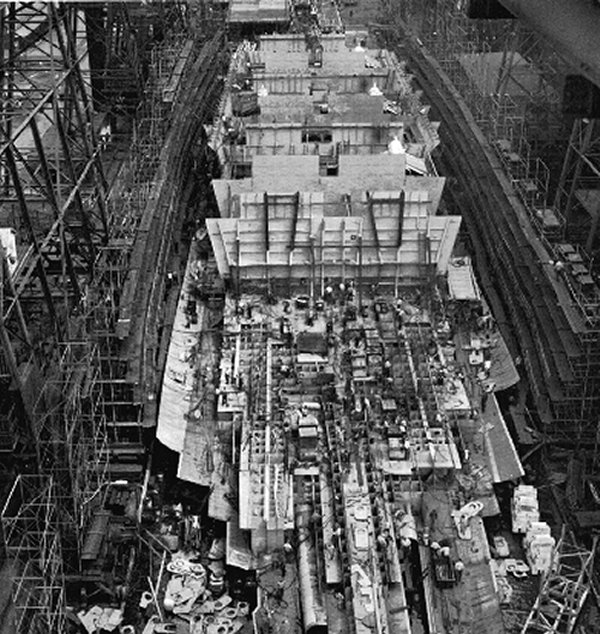

USS Illinois in construction, 1944

The Navy initially planned to develop the previous alternative design using the escalator clause, lower but better protected and armed, designated “BB-65” (Montana class). However with industrial mobilization in 1940 the Navy intstead deided to authiroze the next BB-65 and BB-66 ax extra Iowa class design. USS Illinois and her sister sister ship diverged as calling for all-welded construction to saved weight. They were powered by four General Electric steam turbines, same armoured change, and for armament, the same but eighty 40 mm Bofors AA guns and forty-nine 20 mm Oerlikon AA guns.

Since the Missouri the frontal bulkhead armor rose to 14.5 in (368 mm). There were also a better protection for the torpedo defense system increasing its potency for 20% compared to USS Iowa, also from Missouri.

BB-65 was assigned the name USS Illinois by the Preliminary Design Branch at BuC&R. Funding was authorized though the Two-Ocean Navy Act by the U.S. Congress, on 19 July 1940, being the fifth Iowa-class ship. Contract was assigned on 9 September 1940 as BB 66 USS Kentucky and part of the funding came from the auction of “King Neptune”, a Hereford swine which toured Illinois as a fundraiser ($19 million were earned as war bonds).

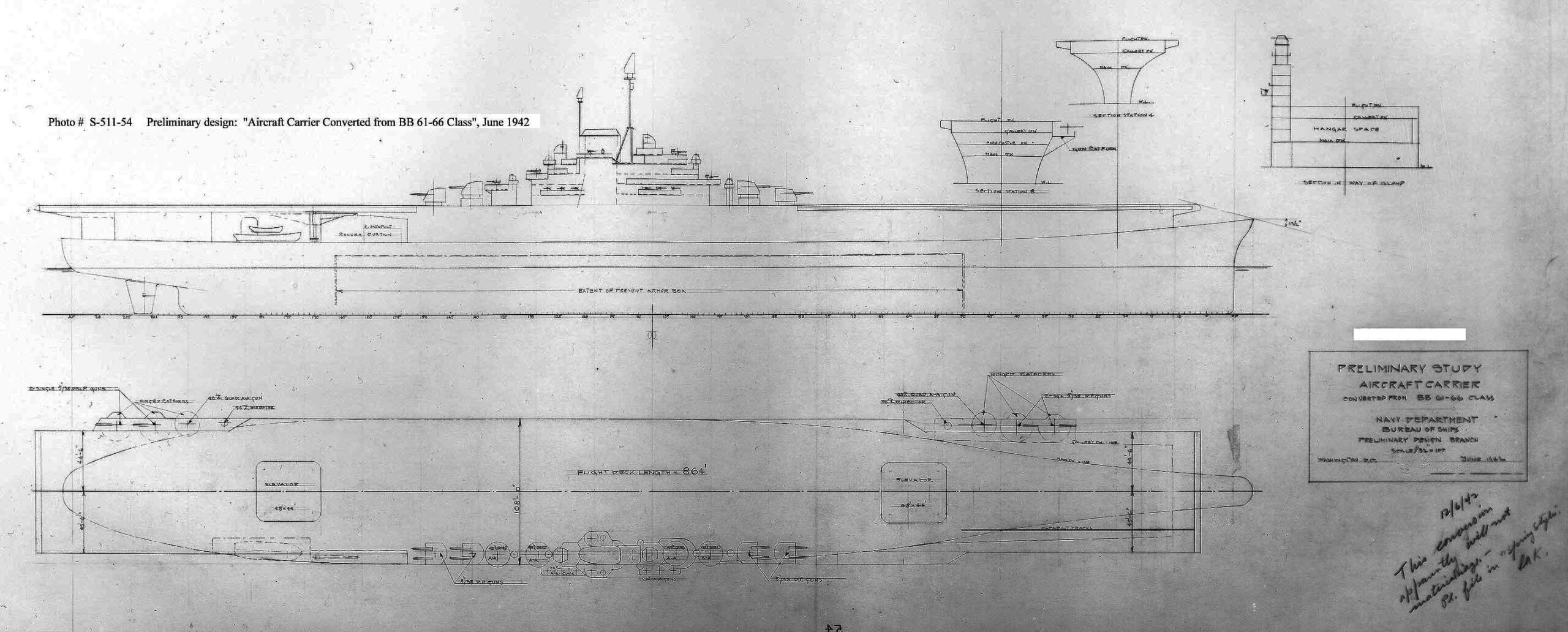

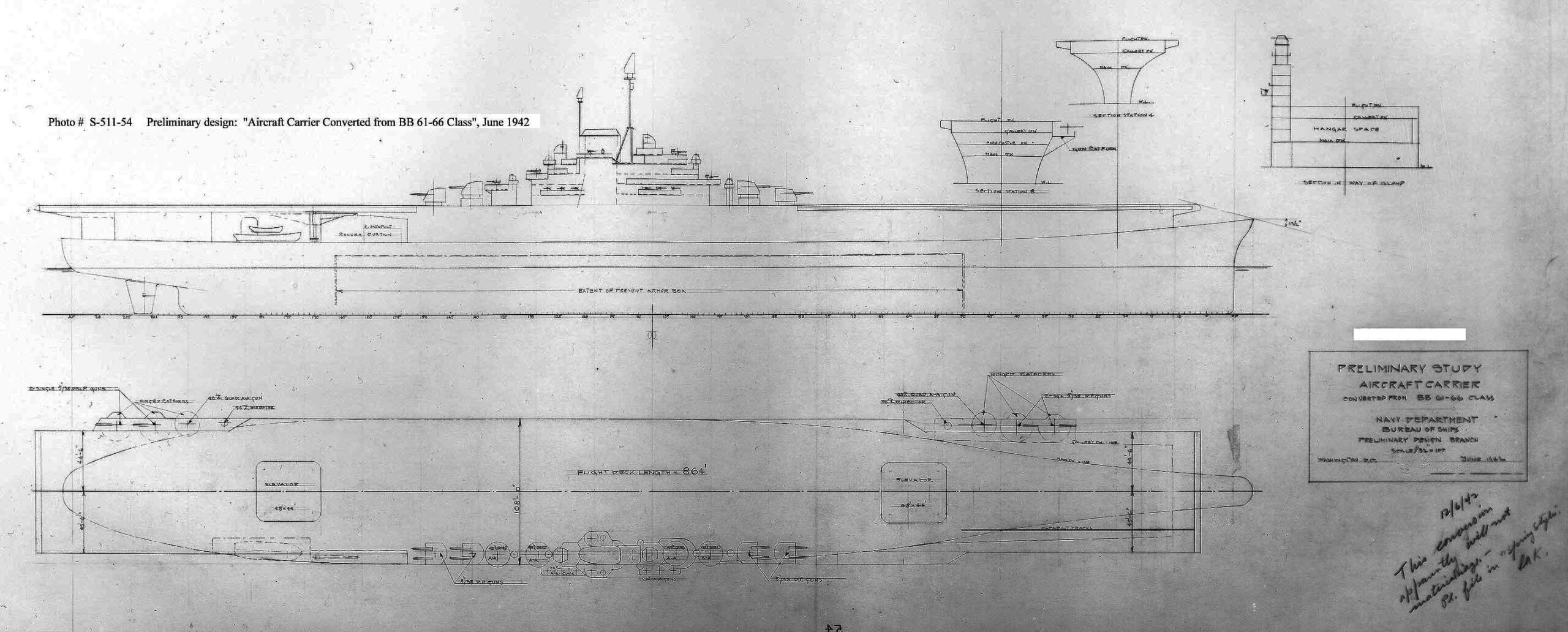

Construction had been put on hold after the Battles of the Coral Sea and Midway, leaving time for BuShips to work on an aircraft carrier conversion proposal for both (see later). At the end of calculation it was estimated thay would have carried lass aircraft than the Essex class and the latter needed less time to be built than the full conversion. So they were soon reverted as battleships and construction resume, albeit at the lowest priority.

Eventually, BB 65 was laid down at Philadelphia Naval Shipyard on 6 December 1943 with an expected completion at around 1 May 1945, but it was not so by 11 August 1945 when cancelled, 22% complete Stricken on 12 August 1945 her hulk was to be half-completed in roder to test nuclear weapons on her. The $30 million to complete her was too much for the admiralty and it was decided to instead to BU her on slipway. But for this she had to wait in the dockyard until September 1958 before proceeding.

Her bell is now a treasured item of the Memorial Stadium, at the University of Illinois, loaned by the Naval History and Heritage Command in Washington NyD to the Naval Reserve Officers (NROTC) at the university, rung for football team scores.

USS Kentucky (BB-66)

USS Kentucky’s hull in 1950, floated out of drydock to allow USS Missouri to be repaired after runing aground

USS Kentucky (BB-66) had the same construction as her sistr BB 65 (Illinois). Construction was suspended to decide if a conversion as aicraft carrier was worthy or not, and when proved the second case, she was laid down at Norfolk Navy Yard in Portsmouth, earlier than her sister, on 7 March 1942. Construction was given low priority, and she was still not launched when suspended in August 1945. This was resumed for launch on 20 January 1950, just to be broken up in Baltimore in 1959.

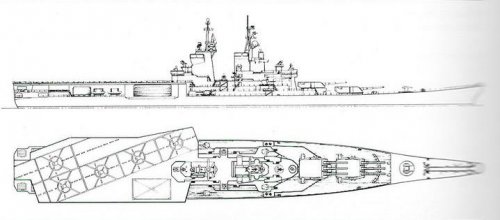

Carrier conversion project

The first suspension arrived after her keel was laid down, in June 1942, just after Midway. Her bottom structure was launched, feeing the place for LST construction, on 10 June. After CV conversion idea was abandoned by BuShips her completion as battleship was resume, but at very low priority. Work resumed on 6 December 1944 when her keel structure was moved to Dry Dock 8. By now her completion was estomated by late 1946. In December 1945n the war has ended and some proposed she would be completed as a dedicated anti-aircraft battleship, as the French Jean Bart, and construction was suspended again in August 1946 for BuShip to study the question. No decision was made ultimately, and construction resumed again on 17 August 1948, going on until 20 January 1950, but that this point the admiralty expected much in missiles and estimated her days has passed. She was floated out of her drydock to repair Missouri in her place.

Project SCB 19 (1948)

Project SCB 19 concerned her as a prototype for a missile-carrier conversion that would also be ported on the the incomplete USS Hawaii. The idea was to combined her heavy artillery and guided missiles, now refined. Kentucky was chosen for this conversion, the first “guided missile battleship”. It would have consisted only in the installation of two twin arm launchers RIM-2 Terrier SAM on the aft deckhouse, and associated AN/APG-55 pulse doppler interception radar, AN/SPS-2B air search radar. At that stage, Kinetucky was about 73% complete, basically up to the second deck so that the installation of the missile system, reloads, storage spaces and exlectronics would have only be additions to that point. Some alwo wanted to explore the addition of eight SSM-N-9 Regulus II or SSM-N-2 Triton nuclear-tipped cruise missiles to justiyfy her large hull.

Project SBC 19 was eventually authorized in 1954, USS Kentucky becomin BBG-1, with a conversion complete as estimated in 1956. But it was cancelled based on maintenance cost. It was estimated that it wouyld make more sense on a heavy cruiser instead, which became the Boston-class. And it proved wise as rapid advances in missiles and electronics soon rendered them obsolete and costly to operate. In between a smaller “fleet escort” type could carry a more balanced missile array for the same task as a fraction of the cost. Heavy guns however were still in demand.

Second missile conversion project (1956)

So that led to the last twist in this story: By 1956 she would had carried two Polaris nuclear ballistic missile launchers (sixteen reloads), four RIM-8 Talos SAM launchers (2x 80 in storage) and 12x RIM-24 Tartar SAM (504 missiles), which were all new systemsn while keeping her lain artillery and protection. But by July 1956 an estimation for completion placed it to July 1961, and it was cancelled under the Kennedy administration based on cost concerns. (Again, there were still four battleships in reseve for the artillery role, and she was costly in maintenance as a missile platform, even large).

Therefore after all this time, her keel being laid down in 1942, USS Kentucky was never completed and became a hulk in the mothball fleet; Philadelphia NyD, until 1958. There was another surprising twist: Hurricane Hazel hit the reserve and on 15 October 1954 her moorings ceded, and she broke free, to run aground in the Delaware River. In 1956 she was removed and partly dismantled to serve as parts reserve, to repair USS Wisconsin damaged in a collision with USS Eaton, on 6 May 1956. At last she was stricken on 9 June 1958 and sold for scrap at Boston Metals in Baltimore, on 31 October, towed there to be BU on February 1959.

Her boilers and turbine sets were recycled into the new Sacramento-class fast combat support ships (Sacramento and Camden in 1961-64). Sailors of these ships passed o their precious experience to those aboard New Jersey during the Vietnam War and toured all remaining Iowa class vessels as they were modernized in the 1980s.

The never built Montanas, 1942