In destroyer history, there are a few landmarks most authors agrees upon. Let’s cite for example the Spanish Destructor in 1886, recoignized generally as the earliest torpedo boat destroyer, the British Daring class in 1893, the US Bainbridge class inaugurated their own lineages, the massive HMS Swift in 1907, unhappy pet project of Sir “Jackie” Fisher or the much smaller, but more practical and innovative River class in 1903, the Shakespeare class (1916) Destroyer leaders, announcing the interwar standard, the 1917-21 Wickes/Clemson of first mass-production models, or the Fubuki class in 1926 or “special type” which also defined a new standard for the Pacific…

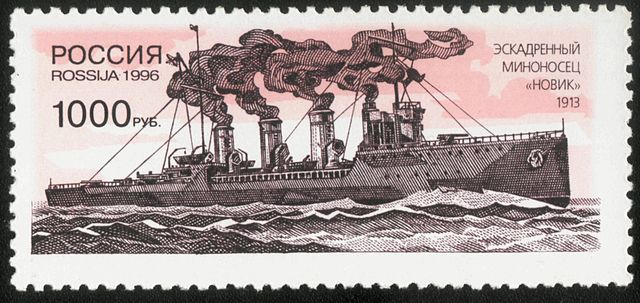

But in between is also Novik, considered by most authors as a landmark for destroyer design in 1911.

Indeed, the first vessel of that name was a prototype, built in Germany on Russian ideas. Novik was the forerunner of a new generation of Russian fleet destroyers which counted no less than 52 ships, within four classes: The Derzky-class, Orfey, Izyaslav and Fidonisy-class destroyers. This post will be followed by these classes, treated one by one on their own dedicated post in detail.

Novik was the world’s first oil-burning destroyer, and the first Russian destroyer with steam turbines as well. It became with an unmatched powerplant at the time, the world’s fastest ship, beating all categories. And as a destroyer, extremely well armed with no less than four 102 mm (4.0 in) guns and eight torpedo tubes in twin banks. The following will stick with these figures, sharing the same hull, powerpant and general design. This was quite a formidable new standard and in this pre-dreadnought age, all admiralties took notice, from Berlin to London, Paris, Rome, New York and Tokyo. Unlike previous generation, they all survived WWI and the civil war, and were preciously maintained by the Soviet Navy, renamed, and seeing a fair share of action in WW2 as well.

Origins and Development

The admiralty’s destroyers in 1908:

Three years after the devastating defeat of their war with the Japanese, the crippling losses of Tsushima, of the Pacific and Baltic sea fleets combined, a serious train of reform, a walz of officers and ministers equalled a “great reset” at the head of the Naval Staff. None was spared the maelstrom of mutations. Severe criticism about the Navy, albeit not made public, had for effect to put it back in shape, on a time schedule which was to end with the start on WWI. Like many other navies (and like in 1941), the Russian Navy was caught off-guard by the start of the war.

One aspect that was criticized, was the total lack of adequate support for the Battleships during the Battle of the Yellow sea in 1904 and Tsushima in 1905. Admiralties indeed had no plans to screen their precious battleships with a buffer of expandable vessels used for reconnaissance and protection: Fleet destroyers.

Special committee for the Navy’s reinforcement:

Emphasis on mine and torpedo warfare shown in this war shown the potential capabilities of more capable Destroyers, even their capabilities as “universal ships” carrying out torpedo attacks, patrol, minelaying, and even coastal bombardment as well as fleet screening. The last war involved 18 minelayers, enlarged version of the standard 350-ton destroyers as the basis of the mine forces ordered with funds raised by the “Special Committee for Strengthening the Navy”, based on voluntary donations. These Minelayers were more advanced ships at 600-700 tons, with improved seaworthiness and enhanced armament, but could not fully fulfill escort tasks for largeer ships in any sea state. The “Special Committee” secured 2 million rubles to spend on construction of a new type of ship taking into account the experience and new set of requirements.

Thus, Novik was financed by donations during the 1904-1905 war. The design was subjected to delays due to the study of numerous reports, a compilation of experiences. They were supposed to be very fast, in part as an active protection against rapid-fire guns, delivering a powerful torpedo broadside (eight or ten was envisioned, or even more), completed by artillery if needed, or to lay “active” minefields in the path of an approaching battlefleet, an idea that was to have a long reach in the Russian naval staff, well into the Soviet era.

December 1905 Reunion

By December 1905, the Marine Technical Committee (MTC) held a meeting presided by the commander of the 2nd Pacific squadron, Z. P. Rozhestvensky. The development of a new minelaying force was decided. Some participants proposed new minelayers with increased displacement, others supported the idea of small destroyers for coastal defense, also capable of minelaing. The majority, so 14 versus 9 wanted specialized “mine cruisers”. Characteristics proposed were a speed of 28-30 knots, 6-8 long-barreled guns (with two 120 mm, six 47 mm or four 75 mm) plus four machine guns and three 450 mm torpedo tube banks. They were to be given oil fired steam boilers for a range of at least 3,000 miles at 12 knots. Rozhdestvensky wanted tro limit the tonnage to 750 tons, but it was not accepted as unrealistic. The machinery type, VTE or turbines, remained open oto discussion. Mechanical engineers present wanted to push for steam turbines. Particular attention was paid also to structural strength of the hull and absence of vibrations at full speed, also important for the latter and construction engineers, which also played on the powerplant type. As a result, no form decision was made, but this was the starting point for further development, which later ended with a new type of turbine destroyers.

Technical aspects of Novik (old rusian publication)

Summer 1907 Reunion

In the summer of 1907, the “Special Committee” still lacking official instructions from the Naval Department to solve the issue of the powerplant, formed a technical commission of its own to study several technical aspects of a high-speed turbine destroyer. The operational-tactical task (OTZ) for this project had the proposed objective of reaching 36-knot and from this the Russian Naval General Staff for the first time whorked on a new multi-purpose mine-torpedo-artillery ship designed for high seas reconnaissance and commerce raiding operations. An untouchable thoroughbred and jack of all trades.

Special attention paid to speed and cruising range, plus seaworthiness had engineers proposing a hull able to clip through waves at a winds force 8-9 with 7-8 force waves, and supported the idea of a large hull to “ride” the wave lenghts at 35 knots, with a range of 1,800 miles or 86 hours of continuous travel at 21 knots. Displacement was eventually limited to 1000 tons with the armament precised to two 120 mm gun, two twin 450 mm torpedo tubes with spare torpedoes.

Final Requirements of 1908

All this led to requirements setup by the admiralty. Specifications developed by the Marine Technical Committee (MTC) under the guidance of shipbuilders A. N. Krylov, I. G. Bubnov and G. F. Shlesinger precised also a displacement of 1000 tons, full load speed of 33 knots, armament of two 120-mm cannons, 4 machine guns, three 450-mm twin torpedo banks and a main power plant with Parsons steam turbines. On February 11, 1908, the “Special Committee” sent these to several shipyards with a request to report cost and time of construction within two days.

Answers received in tome showed this was difficult and most importantly, yards did not wanted to deal with the specificications without a guaranteed order.

It was also decided to announce an international competition for the new “36-knot destroyer” with the right to provide the winning proposal with an order. Invitations were sent out in mid-1908, and more time was left/ The first answers came back in October. In January 1909, the commission rendered its verdict:

The four Russian yards’s proposals had been considered and foreign ones rejected at the preliminary stage (not meeting the competition’s conditions).

The former were Admiralty, Creighton, Nevsky and Putilov.

As a result, the Putilov Plant project developed by chief engineers D. D. Dubitsky and B. O. Vasilevsky were recognized as the winner.

Putilov won the order (1909)

The order to the Putilovsky plant was confirmed and approved at a “Special Committee” reunion of July 4, 1909 marking the end of the said committee. By July 29, representatives of the Putilov Yard signed an agreement of a delivery for trials within 28 months from signing date. The contract conditions were handed over to the Imperial treasury on August 1, 1912 to secure funds. These represented 2 million and 190 thousand rubles at the time, but assorted with trials and construction penalties for exceeding building time and not meeting speed requirements, as insufficient stability.

The detailed design was made in putilov’s design bureau in 1909-1910, together with the German company Vulkan which undertook to design, manufacture and install a powerful yet compact three-shaft boiler and steam turbine units. It would also looked at the tactical and technical requirements. This work was supervised by D. D. Dubitsky for the mechanical part, with B. O. Vasilevsky tasked of the shipbuilding part. Navy Supervision was entrusted to Lieutenant Colonel of the Corps of Naval Engineers N. V. Lesnikov, assisted by Staff Captain V. P. Kostenko for the mechanical part and Staff Captain G. K. Kravchenko foe the construction as well as Yard’s Chief Builder C. A. Tennyson. A permanent laison team was installed at Vulkan, Stettin, working with daily communications.

Design of the class

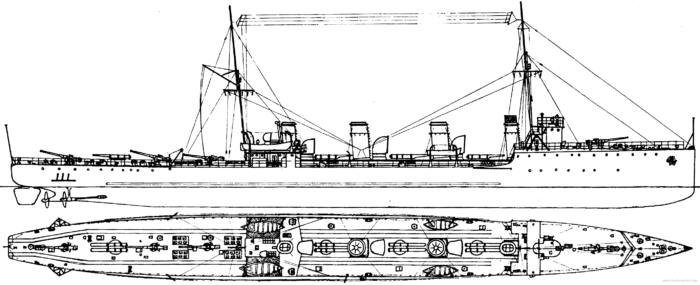

The main differences between the lead ship and subsequent mass-produced destroyers were that Novik had a four-funnel silhouette, two superstructures, and three-shaft powerplant. But the two masts, forecastle extending a quarter of her length, solid main deck, forecastle deck, were carateristic of subsequent Russian destroyers until the Gnevny, the new 1930s generation.

Hull Design

The hull was riveted and 102.43 m over its total lenght. She was 9.53 m in beam, making it for a 10.75 ratio. Particular attention was paid to ensure longitudinal strength, based on a 100 m (328 ft) wave length, with a 5 m crest (16 ft). The hull was assembled with high-strength steel framing and plating (tensile strength 55–70 kg/mm², elastic limit of 28 kg/mm²). The framing had intervals of 560 mm (1.83 ft) from the stern to the bow for extra rigidity. The main feature was the use of an longitudinal reinforcement around the boiler and engine rooms, proposed by I. G. Bubnov.

The hull bottom consisted of a 8 mm thick vertical keel, 1,050 mm high (3.31 ft) with double steel squares along the upper and lower edges, two bottom and one side stringers either each side, and one carling per side. The whole structure, together with a 4-mm (0.15 in) thick deck at the second bottom and upper deck, were enclosed between longitudinal bulkheads, 3.5 m (11.4 ft) from the centreline, with a 6-9 mm (0.2-0.3 in) thick outer skin and 11.5 mm (0.45 in) thick deck stringer. This formed a fairly rigid structure withstanding very hard longitudinal bending in any operating conditions.

The double bottom extended along the main powerplant, divided into compartments storing extra fuel. Outside the engine and boiler rooms, the vertical keel was sloped down, smoothly turned into a vertical forged stem and cast sternpost. The prow was shaped and reinforced in order to break ice. The transverse framing consisted of double frames, 6 mm thick each and interconnected by brackets of 4.5-5 mm sheets and beams of the upper and main decks (5-6 mm squares). According to this transverse scheme, the forecastle was made of 4 mm sheathing and flooring.

The outer skin consisted of 8 plating belts, including the keel belt and sheerstrake. Their thickness decreased from 9 mm at the keel belt and 8.5 mm at the sheerstrake down to 6 mm. Belts connection used rivets in 3 horizontal rows applied on same frames.

Superstructure Design

The bow superstructure consisted of a forecastle bridge, combat bridge and unprotected wheelhouse. The conning tower below was made of chromium steel walls, 12.7 mm (walls) thick (0.5 in) and 6 mm (0.3 in) for the roof plate. Low-magnetic steel was used for the compass area to avoid interferences. The navigator’s cabin was located behind the combat cabin (with the chadburn and acoustic pipes were located) made of 3-3.5 mm mild steel sheeting. The forecastle bridge was built atop the conning tower with the navigation cabin behind it, extending the entire width. Both the bridge’s spotting wings were supported by pillars connected by diagonal struts.

The stern superstructure started aft of the fourth funnel and was noticeably larger than the rest of the Novik-derived destroyers. It housed a radio room, a galley with an oil heating apparatus for cooking. The aft bridge wings were beam-wide, ans also fixed by pillars and struts. The “radio room” housed of course a wireless radio telegraph, and soundproofed. Walls and ceiling indeed had a built-in air gap 45 mm thick in 3 rows of 12 mm boards and 10 mm felt layers for better cushion. On top of the inner boards an extra layer of 10mm felt was added. The floor was paddled, with a 45mm air gap, two 25mm boards layers and 15mm cork layer. All internal surface were also covered with linoleum. To further reduce vibration and heat the floor was raised more above the machinery. Telephone for internal communication was coupled with a the dynamo located outside the wheelhouse.

During her major overhaul, this superstructure was redesigned: The stern superstructure was expanded, accommodating a division headquarters room, and a damage control post. The radio room relocated instead forward of the first funnel. The bow brudge was also expanded and fully enclosed. Instead of pole masts, tripods were installed to support heavier platforms, notably spotting top and projectors, and heavier wireless radio cables for longer range.

Accomodations

Novik was a brand new league for the crew accomodations, at the relief of the latter compared to previous destroyers. There was a well better though at and convenient distribution of living quarters with the commander and officers cabin as well as the “campaign cabin” and mess located under the forecastle, closer to the bridge for quick turnover and reaction time. They were also aklways close to the combat and navigation cabin, but not from the radio, which communicated via the internal telephone. The officer’s quarters were semi-luxurious with in addition to the mess hall, a bathroom and latrine. Each officer’s cabin had a bunk, wardrobe, folding washbasin, desk, chair and hanging hooks.

The later increased crew in the interwar led to a deterioration of living conditions. The latter was located mostly aft to avoid the noise from the engine compartments as much as possible. No bunks still, but hammocks. These rooms were located in the stern (two) and in a single bow cabin, mostly officers assistants. Depending on the space available, there were lockers and some folding beds. Personal gear were stored in lockers, but bed nets close to the bridge were a novelty. Conductor rooms (large enough for 6 men each) were located aft, equipped with lockers in two tiers but also wardrobes and a small living room with books, chairs and a dining table.

The galley was located under the aft bridge, with stoves using oil heating, for the ratings. There was a separate officer’s stove and samovar (because Russia), and provision srorage rooms. The attenant room to the galley had a table and shelves. When modernized, the larger crew forced to enlarge the galley and bridge.

To avoid internal shrapnels when hit by shells, sides were sheathed with cork plates with an air gap, and bulkheads painted with white lacquer paint acting also as lining, to prevent shards. The floors were covered with 5 mm linoleum for a better cushion while all the latrines and bathrooms were floored with chipped marble on cement. Cabinets and tables as well as lockers and washbasins were made of mild steel. Chairs however were made in wood, curved beech, and ash for the rest of the furnitures.

Protection layout

The danger of mines dicated a separation of the hull underwater into 9 main watertight bulkheads at the 14, 41, 55, 75, 96, 117, 139, 159 frames. This bulkheading went up to the upper deck and ended at the 175 frame to the forecastle deck. In addition, eight more separations were installed at 20, 28, 37, 142, 146, 153, 165, 169 frames up to the weather deck, down to the stern. Their thickness was 5 mm for the lower cord and 3 mm for the upper one. This was completed by the conning tower at the bow, 0.5 – 0.3 in between the walls and roof was seen above.

Powerplant

Novik was the first domestic ship fitted with steam turbines, operating only on fuel oil. Steam turbines were all the rage at the time for the Russian admiralty, which wanted to procure them too for the Sevastopol class battlecruisers and the new cruisers of the Svetlana type in construction. On the Sebastopol class though, this was coal heating and for the cruisers a mix of both. The choice of oil only for the destroyers was dictated by relative scarcity of both oil and space, prioritizing oil to that class.

The plant consisted of three steam turbines of the Curtis-A.E.G. Vulcan type (a licenced Curtis type by AEG). These were classic direct drive turbines made at Vulkan, Stettin in Germany.

They had a linear layout with the boilers. These were six water-tube Vulkan models. From the bow to the stern, at forst 6 boilers, located in three boiler rooms, were followed by the steam turbines, two in the bow, on in the stern. Funnels corresponded to boilers No. 1 and 6 to their own (1st and 4th funnel), and boilers No. 2 and 5 corresponded to Funnel 2 and 3 amidships.

As for the turbines they were of the direct-acting type, not fitted with a reduction gear. They drove the propeller shaft through intermediate shafts and composed from a high-pressure turbine (HPT), and low-pressure turbine (LPT), plus a reverse turbine (RTH). Components were located on one shaft and single casing. The low pressure turbine was supposed to deliver 35% of the forward, HP turbines with a total contract power rated at 42,000 hp (unofficially 42,800 hp). They were capable of 640 rpm, enabling speeds up to 37.3 knots. Full speed was however reduced in practice to 36 knots, and when cruising, 21 knots which was the standard for capital ships at the time. At the end of the shaft lines were three three-blade bronze propellers 2.4 m in diameter (7.8 ft) with a pitch of 2.3-2.2 m (7.5 ft).

The water-tube boilers were of the also classic triangular type. Two were located in each of the three boiler room. They had an unitary capacity of 50 t/h for a total of 290 t/h. Total heating surface was 850 m² for a total of 4,970 m². Note that the smaller Boiler N°1 had inferior values. Thes boilers produced supersaturated steam at 17 kg/cm² (1.19 Ib/Sq. inch) and 203° Centigrades (397° F). These boilers were fed with freshwater using piston feed pumps, two per Boiler. Double-capacity pumps were installed. The feed water was heated by Norman heaters, one per boiler, operated on exhaust (“mint”) steam. This loop enabled the feed water to be already heated up to 60–80 °C before it was fed into the boiler. The two 13 tonnes Feed water tanks were located in front of the bow boiler rooms, behind the aft engine rooms.

Fuel supply was 351 tons of fuel oil, stored in double-bottom compartments motly between frames 42 and 139, with exception, additional fuel located into side tanks between the 75 and 117 frames, for a grand total up to 418 tons usable in wartime and for long crossings. The upper tanks were of course those emptied first to not compromise stability. With all this, range was down to 740 miles if using a practical long run full speed of 34 knots, but up to 1,760 miles at the economic cruise speed of 21 knots.

Radio & Communication

The radio room was located under the aft bridge, and the first model installed was a long-wave transmitter of the MV type from the Naval Department, model 1911 rated for 2 kW and with a range of 200 miles. It also had a long reception range with its two tube receivers at 300-1900 m. The destroyer also had 30 W radiophones. Internal communication used traditional voice pipes, but also telephones and bells, notably to communicate from the bridge to the radio room, machinery, fire posts and torpedo room. Voice pipes were made of red-copper 45 mm in diameter with brass sockets and whistles. They passed from the navigation bridge and conning tower to the guns and other places directly behind. The telephone network was mostly useful to connect the conning tower with the bow and stern bridges and nearly all others compartments. The senior mechanic was in contact with the bridge on an open line. The conning tower was connected with the division commander’s room and commander’s office as well as the wardroom and mess in order to be sure reaching any officer.

Visual communication rested on a signal searchlight on the foremast platform, and a Semyonov system lights, Ratier system and STB stereo tubes. There were also day and night binoculars, and traditional signal flags and flares. After modernization, these were improved, as in 1931-1932, Novik received the “Blockade-1” receiver/transmitter radio with a much greater range, and after her second overhaul in 1937-1940, the “Blockade-2” system, plus the VHF radiotelephone station “Reid”.

Navigation Equipments

Novik was fitted with three 5-inch (127-mm) magnetic compasses, with direction-finding devices but also a sextant, chronometers and a laying tool. The main magnetic compass counted a large binnacle located in the center of the navigation bridge. Steering compasses were placed on the open bridge, next to the helm and the conning tower. Novik also had two 75 mm smaller boat portable compasses in order to carry them on the cutter or small boats in case of abandoning ship. Depth was measured by a Thomson mechanical system and traditional backups. Speed was measured by a Walker turntable with control posts located on the bridge and conning tower.

After her 1931 upgrade, Novik was given the Russian gyrocompass “GU mark 1”, first tested aboard. Its repeaters were added on all her control posts. The turntable was replaced with an electromechanical “GO mark-III” system, also domestic.

Armament

Main

The main guns consisted in four 102 mm (4 inches) L/60 Obukhov cannons. These 4″/60 (10.2 cm) Pattern 1911 coincided with the Novik class. They were placed in the axis, one forward and the remaining three aft, alternating with the torpedo tubes banks. They had a high-mounted pivots for good elevation, but no gun shield.

Performances of these were as follows:

-Shell Obukhovsky 38.58 lbs. (17.5 kg) HE mod 1911

-Unitary cartridge 30 kg including the 17.5 kg shell

-Brass cartridge case containing a 7.5 kg charge

-Elevation Rate 3 degrees per second

-Train 360 degrees at 3 degrees per second

-Gun recoil 28 inches (71 cm)

-Muzzle velocity 823 m/s.

-Range at 30 degrees 16,800 yards (15,360 m).

-Rate of fire 12 rounds per minute.

More on Navweaps

These were rapid-fire guns, provided with 160 unitary artillery rounds per barrel (HE) for a grand total of 640 shells aboard. In 1941 this was increased to 810 rounds. Cartridges were stored in two artillery cellars. There was a feed system upwards using two elevators driven by electric motors (with manual backup), which was quite modern for a destroyer at the time.

Many more shells were made available on the long run as these guns were widepsread and still used in WW2: HE mod 1915 and mod 1911, FRAG mod 1915, HE mod 1907, Shrapnel, Star Shell, Diving shell (for ASW use), Incendiary shell.

Machine Guns

In the “monocaliber” tendency, apart these main guns Novik had nothing else but the torpedo boats. The only exception were 2-4 7.62-mm Maxim liquid-cooled machine guns installed on pedestals on the bow bridge, and upper deck aft, near the galley. Total boxed ammunition and belts totalled 810 rounds per Machine Gun.

Fire equipments

For night fighting, Novik was equipped with a combat 60 cm Sperry searchlight, to illuminate targets.

There was a single manual Barr and Strood 9-foot (base 2,745 mm) coincidence rangefinder installed on the bridge providing data. They were coordinated by a single Geisler-type fire control system communicating setting angles from sights located in the conning tower. There were four sets of data display (for each of the guns). These were equipped with bells and howlers to signal a shot or a volley.

Torpedoes

The four twin torpedo launchers were all in the axis: Three aft of the forecastle, the last forward of the radio room and mainmast, and a fourth aft, in between the third and fourth gun mount.

These four twin-tube 450 mm torpedo tubes were already above the average destroyer armament. The admiralty thought of triple tubes already, but due to weight issues, the system was not ready to be adopted yet. The catch however was that if torpedoes were stored directly in the tubes, there were spare torpedoes provided. This was a one-way ticket. Loading torpedoes and feeding them into the tubes was a long and complicated, even dangerous task in case of unclement weather. Using manpower with beams, cranks and manual winches. These were Whitehead torpedoes, which detonaters can be loaded and stored separately in a single small cellar.

Despite the advantage of a twce larger tproedo volley, compared to previous designs, the main drawback of Novik and her followers in the Black Sea Fleet were the torpedo tubes used: The twin-tube made at Putilov factory had rigidly fastened tubes with the impossibility of target tracking, lacking the appropriate clutch in the gear train and with a slow mechanical rotation, plus a structural defect in the charger shutter that was never really solved before the late interwar.

Mines

Novik and her successors were also wanted by the Navy Staff, given the lessons of the Russo-Japanese war, as “active minesweepers”, capabk of a rapid delivery directly into the path of an underway enemy battle formation, even under fire. Their speed was their best weapon, but this meant dropping mines at 30 knots+ which was never done before, especially if the stern wake wave had the potential to create such a depresssion a contact mine could unexpectedly return to the stern and explode. This tactic was seen as a way to scatter the enemy formation and favor torpedo attacks. The staff launche itself in many new imaginative tactics as the last war was seen as missed opportunities, not having the proper ships. Novik’s mines were stored on two long rail tracks on either side of the lower hull aft, starting at the forecastle. That was quite a distance, enabling a larger number of mines can be carried, unlike previous destroyers.

According to the naval staff, Novik and her followers could lay up to 50 mine thanks to these permanent rails and mine slopes, which shaped was carefully studied in a basin to avoid high speed turbulence issues. In addition, the destroyer tested on-board mine ramps which were given a 20° angle towards the stern also to solve these high speed laying issues. The slopes protruded overboard by 1.5 m at this but this design turned out to be unsuccessful and only worked below 24 knots instead of 30 knots. Mines had even the potential to be sucked underwater towards the propellers.

In the 1930s, Nobik received two K-1 paravanes for anti-mine operations.

For ASW warfare, Novik was given in WW1 ten 10 depth charges of the types 4V-B or 4V-M on two five-charge racks at the stern. They were replaced in the interwar by more advanced BB-1 and BM-1, respectively 8 and 20, stored between racks, manually dropped overboard or using carts tailored to support 4 large or 5 small depht charges.

Modifications

In WWI, Anti-aircraft defence was added to the ship with the installation of a single 76.2-mm Vickers type AA gun on the quarterdeck. This was likely done during the winter of 1914-15. There was a supply of 300 rounds located in the mine storeroom.

Also the main artillery received modified mounted with a greater elevation angle to 30°, whereas three guns were reinstalled behind the aft superstructure. The sol AA gun remained in place but both at the bow and stern decks a single Maxim 37-mm LMG was installed, replaced later in the interwar by a 45 mm 21-K semi-automatic gun. In the 1930s, two extra 12.7 mm DShKs HMGs were also added, to complement the Maxim machine guns. In 1940, a second 3-in (75 mm) Lender anti-aircraft gun was likely installed and the Maxims removed and replaced by four DShKs. The old Barr & Stoud rangefinder was left in place but a 1.5 m wide DM-1.5 was added on the aft bridge for better range and accuracry. The combat 60-cm Sperry searchlight was replaced by a Russia MPE 6.0 of the same diameter.

In the end, four 7.62-mm Maxim AA machine guns were also kept for close defence.

So to resume at the start of WW2 Novuk had two 76.2mm AA guns, one 45mm/46 mm 21-K AA gun, and four 12.7 mm DShK HMGs, plus potentially four Maxim LMGs.

Anti-submarine armament was increased from ten 10 depht charges to 28 (8 BB-1 type and 20 BM-1 type). Mine and torpedo armament was upgraded to three triple tubes and 50 sea anchor mines.

This torpedo overhaul gave Novik and her follow-ups the occasion of getting rid of her problematic torpedo armament: The stern No. 4 bank was rmeoved, the remaining three converted to new three-tube torpedo tubes banks model 1913 without all the main shortcomings of the two-tube banks. They allowed quick revolution for volley firing and better, more accurate speed control rotation notably by the use of a Jenny clutch. Spare torpedoes however were still not provided. Torpedo fire control rested on Mikhailov M-1 sights mounted on the bridge’s wings. Also Ericsson’s PUTS system were installed, and later removed.

Construction and Trials

In 1910, at the eve of her keel-laying, it was decided to assign Novik to the Baltic Fleet instead of the Pacific. One reason was the proximity of the German yard in case of any mishaps, and because the new head of the Baltic Fleet, Vice Admiral N. O. Essen, personally asked this to the Emperor, as well as securing the name “Novik”, in memory of the 2nd rank, 1898 cruiser Novik which he commanded in 1902-1904 scuttled during the war. Novik ship was laid down on July 19, 1910 at Putilov Shipyard, St. Petersburg in presence of the Minister of the Navy.

On May 1, 1912, Novik started her sea trials. On May 17, she achieved 35.8 knots at a measured mile, off Wolf Island, down to the contract speed by 0.2 knots. This was world record, but below expectations, and despite of this, it was judged still satisfactory and it was not considered to review the propellers or oil heating system. The ship also failed top reach the contract speed on June 18 and July 1 with an average of 35.85 knots. Eventually it was decided to change her propellers on July 30, and yet she still only reached 35,275 knots.

As a result, the commission found it was impossible to meet the contractual conditions and the Yard then returned itself towards Vulkan AG in order not to lose face and gain experience in design, manufacture and testing of powerplants. There was indeed no equivalent in any fleet at the time. Vulkan proposed to increase the boiler’s heating surface, replacing fans and inductors. The proposal was accepted and work started by the summer of 1913.

By August 28-30 torpedo launchung tests commanced, at speeds ranging from 18 to 34 knots. The commission decided to install bells and special signs inside the machinery also to raise wareness of the machinery engineers since te noise was unbearable at high speed, completely masking commands. On September 5-6, vibrations were tested and not judged too excessive for the guns, with residual deformations observed being minor. In the autumn it was established her metacentric height was excessive at 0.8 – 1.13 m with extra roll. At Putilov it was proposed to install extra ballast tanks to cure the problem, and extending the side keels, but at a cost of 1.5 knots speed.

In the spring of 1913, she was prepared to reach Vulkan, Germany, her armament removed, ammunition unloaded. On May 17, she was in Stettin and was gutted open for 3 months, to have her plant overhauled: All boilers were replaced, new inductors and fans installed, the expansion surface increased and thickness by 213 mm and 294 mm. After static tests, the steam output was increased by 15%. A casing was installed above the boiler room to allowed them to stand, being 325 mm higher. Also Vulkan precised the operation ad her displacement increased to 1,296 tons.

On sea trials on August 21 in German waters, Novik reached 36.92 knots (based on 13,60 tons, with an output of 42,800 hp) and even reached 37.3 knots over three preliminary runs, setting a world record. On August 27, official tests at full speed followed, recognized as successful with an average of 36.82 knots (41,980 hp and 141 tons more than normal displacement) over three hours, and with “peaks” at 37 knots and final average of 36.2 knots. On August 29, trials were complete so she was accepted for service. WW1 was just a year away.

⚙ specifications |

|

| Displacement | 1,280 tons (1260 long tons) standard, 1,360 tons FL* |

| Dimensions | 102.43 x 9.53 x 3.53 m ( feets) |

| Propulsion | 3 steam turbines “A. E. G. Curtis-Vulkan, 6 Vulkan Boilers 42 000 shp (29.44 MW) |

| Speed | 37.3 knots (21 cruise speed, 32 average service)** |

| Range | 740 miles (32 knots)*** |

| Armament | 4x 102 mm, 4×2 533mm TTs, 2 LMGs, mines, see notes. |

| Crew | 117 (1940: 168) |

*1940: displacement standard – 1483 tons light, 1,717 tons normal and 1,951 tons FL.

**1940: Top speed 32 knots, 30.5 knots FL, 16 knots cruise speed.

***Cruising range 1940: 1800 miles (16 knots)

Final Assessment

On October 5, 1913 on the granite embankment of the Neva in St. Petersburg a crowd watched an unusual event, the arrival of a handsome new vessel, the destroyer Novik. The general public came here to admire her size and shape, but experts considered her advantage was a combination of innovation that were not perceptible by the general public: A true revolution in the development of such class of ships worldwide. Novik laid the foundation for the construction of a new type of fleet destroyers all fleets of the world. All admiralty took notice and prepare their own designs, when WWI broke out, many of these designs were ongoing. The first concerned however were the British, not the Germans, which strangely did not changed anything to their ongoing “hochseetorpedoboote” construction policy. The small black “toothbrush” style boats were judged sufficient for the confines of the Baltic and North Sea. The Russians hiwever had to care for the Pacific and the British their own far-fetched empire.

In WWI German “destroyers” were created exclusively for torpedo attacks as part of a flotilla, and focus on powerful torpedoes. The Germans unreasonably neglected artillery believing that keeping a tight formation would delegate fire protection to a light cruiser used as flotilla leader. German shipbuilders as the naval staff were also dismissive of radio equipment, assuming these flotilla were not intended either for reconnaissance or laying minefields, seen as a dangerous diversion of their core mission. However German High sees TBs had for them high speed, still good seaworthiness and long cruising range despite thir limited size.

The British Royal Navy developed their own type of destroyer, quite different and did not neglected other roles, ot the role of artillery. Their destroyers were traditionally more powerful than that the German ones, and constantly strengthened artillery.

The Novik, built on voluntary donations after the Russo-Japanese War favorably differed from other destroyers by its extremely low specific fuel consumption, due to the use of oil-fired boiler heating, high efficiency, compact power unit but also construction with a progressive use of longitudinal steel bracing, better seaworthiness with increased strength based on a still moderate displacement and high speed. Novik also combined a powerful artillery and torpedo armament, a very advanced radio station for the time, for better coordination, and versatility combining minelaying, torpedo attacks and duel with other destroyers, combined with the immense advantage of a superior speed to choose their own moment, and dictate their own battle rythm to the adversary.

The ceremonial keel laying took place on August 1, 1910 at Putilov shipyard was not secret, and thus, followed by naval attachés of all nations at St. Petestburg. The ship was ready a month and a half before schedule, and again, naval attachés came back to see her: This unusual ship borrowed all the best from British and German destroyers, while going further with ma,y other innovations kept on a 1500 tons design. Novik pushed the boundaries of all parameters on a moderate displacement.

In terms of artillery itself, Novik surpassed the competition. The organization of firing was les rational and suffered from cluttered arc of fires on places, but the guns themselves were judged superior to British 102-mm (4-in) guns in terms of muzzle velocity, shell weight and firing range, with the addition of a modern centralized fire control.

The torpedo armament was also formidable with an eight-torpedo broadside, more powerful than even the very latest planned destroyers. And the third advantage was this ability to lay minefields on the go. The concept of “active minelaying” proper to Russia was noticed by all, but raised still doubts about the Russian capacity to effectively lay mines at 30+ knots (which was a design issues that kept admiralties occupied for decades and never properly solved but perhaps by the Germans with their interwar R-Bootes, small enough to avoid turbulence issues).

The last point, probably the most spectacular, and most striking was the new destroyer’s unmatched top speed at the time. This record of 37.3 knots remained uncontested from 1912 to 1917.

The Royal Navy felt concerned by the Novik design, but only went for larger destroyes when WWI started, as destroyer leaders (like the Scott class) with four 102-mm guns instead of three and six torpedo tubes. The British admirakty realized it was extremely difficult to reload torpedo tubes in combat conditions and eventually in turn started to adopt multiple tube banks quickly. But still they were inferior to the Novik (and successors) on that plan, missing a bank. They became eve more concerned as the next Ushakovskaya class had twelve torpedoes to launch in one go.

In 1916, the need to equip destroyers for laying minefields came back on the table to constrain the Hochseeflotte to path of their choosing, and to compensate for the weight of the mines it was necessary to remove the stern gun and stern twin-tube torpedo tube. After a 12 hours operations, including fitting rails, a destroyer could take 40 to 60 mines (for flotilla leaders). Novik and their successors kept that possibility without sacrifice or delays.

In September 1914, Novik was the only ship of her kind in the Russian fleet and she was so different than her predecessors, the naval command had her included in a detachment of cruisers.

She performed well as expected in combat, and in the interwar, was large and solid enough to be upgraded and partly rebuilt twice. Thus, unlike all her precedessors, Novik and her circa 50 sister ships were relevant enough to be kept in service for the whole duration of WW2. Their original concept made them pioneers, and thus perfectly apt after two decades to perform all destroyers missions. They enabled the new Soviet admiralty to capitalize on their intimidating presence and not even considering starting any new design until the mid-1930s -with Italian help- for the Gnevniy class.

Read More

Books

Breyer, Siegfried (1992). Soviet Warship Development: Volume 1: 1917–1937. London: Conway Maritime Press.

Budzbon, Przemysław (1985). “Russia”. In Gray, Randal (ed.). Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships 1906–1921. NIP

Budzbon, Przemysław (1980). “Soviet Union”. In Chesneau, Roger (ed.). Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships 1922–1946.

Budzbon, Przemysław; Radziemski, Jan & Twardowski, Marek (2022). Warships of the Soviet Fleets 1939–1945. Vol. I NIP

Campbell, John (1985). Naval Weapons of World War II. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press.

Friedman, Norman (2011). Naval Weapons of World War One: Guns, Torpedoes, Mines and ASW Weapons of All Nations. Seaforth Publishing.

Halpern, Paul G. (1994). A Naval History of World War I. NIP

Hill, Alexander (2018). Soviet Destroyers of World War II. New Vanguard. Vol. 256. Osprey Publishing.

Rohwer, Jürgen (2005). Chronology of the War at Sea 1939–1945: The Naval History of World War Two NIP

Watts, Anthony J. (1990). The Imperial Russian Navy. London: Arms and Armour.

Links

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Russian_destroyer_Novik_(1911)

https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D0%9D%D0%BE%D0%B2%D0%B8%D0%BA_(%D1%8D%D1%81%D0%BC%D0%B8%D0%BD%D0%B5%D1%86)

https://www.rbth.com/history/328549-russias-world-beating-destroyer

http://navsource.narod.ru/photos/03/217/index.html

https://www.korabel.ru/dictionary/detail/1070.html

https://web.archive.org/web/20110720011950/http://mkmagazin.almanacwhf.ru/ships/novik.htm

https://web.archive.org/web/20110219054450/http://www.navycollection.narod.ru/ships/Russia/Destroyers/ESM_tip_Novik/history2.html

Model Kits

https://www.super-hobby.fr/products/Russian-destroyer-NOVIK.html

https://www.scalemates.com/fr/kits/combrig-70215-novik-1912–187756

https://worldofwarships.eu/en/news/general-news/142-Novik/

Videos

https://worldofwarships.eu/en/news/general-news/142-Novik/

3D

Livery of the Novik as built:

Grey: fan-ejectors capstan, fan-deflectors, 102-mm cannons, skylights, hull above the waterline, conning tower, bow and stern superstructure, steering wheel, fore-mast and fore-yard, chimneys, torpedo devices, shots, hull of a four-oar yal, hull of a whaleboat, hull of a motor boat above the waterline, davits, similar hatches, shields and machine gun casings, gangway, combat searchlights, steam siren steam pipe, main mast, gaff and main yard , ventilation shafts, min-beams, flagpole, propeller guard, fender, 102-mm shell elevators, round hatches, bed nets, outboard ladder, entrance doors, inclined ladders, boiler room ventilation casing, engine telegraph, steam boiler, deflectors boiler room fans, breakwater, signal flag fender, conning tower entrance platform, boiler room casing.

BLACK: Hall anchor, deck hawse, bollards, bitteng, standing rigging, chimney caps, mine rails, ladder brackets, bale slats, Legof stoppers and chain stop frames, anchor tubes.

WHITE: halves of each lifebuoy, spotlights.

RED: Port marker light, hull below the waterline, propeller shafts, propeller shaft brackets, powerboat hull below the waterline, rudder.

GREEN: starboard side marker light.

YELLOW: running rigging, fender.

LACQUERED WOOD: front gangway, main magnetic compass binnacle.

POLISHED METAL: propellers (bronze), side inscriptions, stern inscription, state emblem (copper), sights for 102 mm guns and twin torpedo tubes (bronze), magnetic compass caps (bronze).

Novik in two wars: 1912-1941

Prewar and wartime service 1913-1917

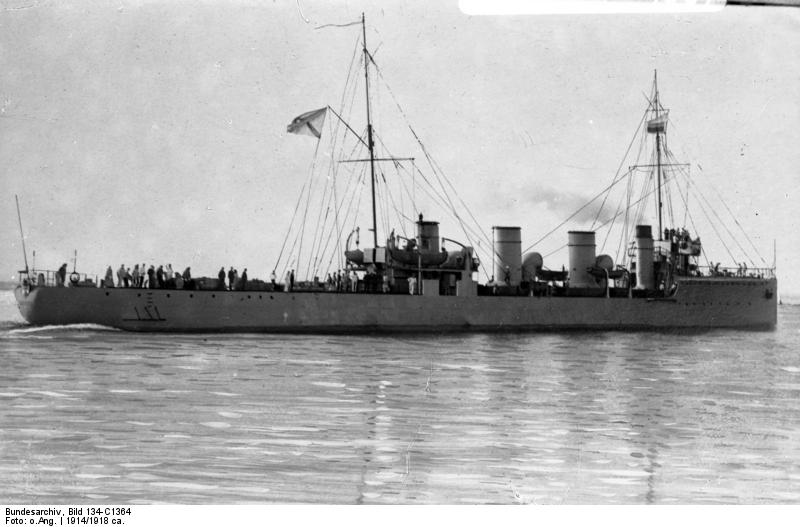

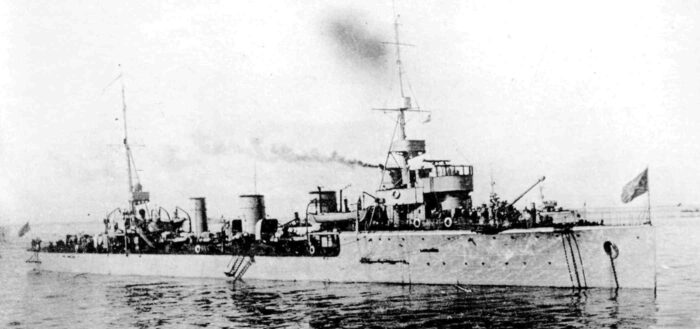

Novik as built in 1911

After sea trials and fleet training, gunnery and torpedo drills, the Novik was ready for her service with the Baltic fleet in the summer of 1914, as the only modern destroyer, enlisted in the cruiser brigade. On July 18, 1914, she operated in the area of Cape Dagerort, covering a large minelaying operation. On August 19-21 and 26, she went for several reconnaissance missions, looking for German vessels. On the night of August 19-20 she spotted and fired 4 torpedoes on the cruiser SMS Augsburg, but failed to hit her.

The commander of the Baltic Fleet, N. O. Essen, decided to carry out minelaying missions by nifght as close as the German coast as possible, and for these purpose, “Novik” was allocated to the special semi-division (Border Guard ships and the General Kondratenko, Okhotnik destroyers) but on site, Novik was supposed to act independently, laying mines in the Danzig Bay, west of the Stolpe Bank, the most dangerous spot. Her saving grace was her speed, which the other lacked.

On September 1914, Novik departed and met on the 2nd a German cruiser patrol, with the latter immediately retreating. SMS Augsburg spotted again her previous assailant and chased Novik for forty minutes, but could not catch up.

From the second half of September 1914, the Baltic Fleet started active minelaying in enemy waters, and the “special-purpose” destroyer unit wasn sent again with Novik appointed as formation leader. Minelaying was carried out in the southwestern and southern parts of the Baltic Sea. Indeed the Nile Bay and adjacent areas adjacent were used by the Kaiserliches Marine for their summer training manoeuvers. Also routes of German transports converged there, including the supply of many steel and weapons factories along the coast.

As a rule, a second destroyer flotilla covered the minelaying and once again, Novik departed to act independently, unsupported. Between secrecy and high speed the admiralty thought these missions would be performed without a hitch. Minelaying was made in full darkness, the flotillas returning at dawn to their shores.

The Germans did not conducted constant reconnaissance in these dangerously close areas, making it easier to approach, with severe consequences: Pn November 5, 1914, 12 days after the first minelaying mission, the armored cruiser Friedrich Karl blew up and sank. It was a stuning first success for the Russian admiraty and a complete surprise for the the German command, many believing this was due to a submarine action, as none though the Russian would have dared minelaying that close to their shores.

Gulf of Riga action (August 17, 1915)

In August 1915, the German fleet tried to break into the Gulf of Riga, mustering two battleships, four cruisers, 33 destroyers, and four divisions of minesweepers, plus a cohort of patrol ships and auxiliary vessels. The breakthrough was covered by ten dreadnoughts, 5 armored cruisers and 32 destroyers. The most important concentration of German naval forces in this area of the Baltic ever.

But minesweeping work was hampered by the battleship Slava. The destroyers V-99 and V-100 were despatched to spot her and sink her in the night of August 17, however they fell on two Russian destroyers, notably General Kondratenko, an older, but still potent design. The night battle had all four opponents quickly lost sight of each other. At 11 p.m. Novik while in the Irben Strait, was contacted by General Kondratenko and dispatched to prevent any German entrance to the bay. German destroyers were illuminated by searchlights from the the “Ukraina” and “Voiskovoy” and a new battle started, a quick exhanged lasting only three minutes. At 600 m, Russian gunners scored hits, launching two torpedoes so close they went under the keels of the nimble German destroyers. But in this exceptionally dark night, they lost sight again. The Germans retreated and waited for dawn to leave the bay through their own minefields.

However at this time, they were chased off by Novik, spotted and signalled in the predawn haze by the Mikhailovsky lighthouse. V-99 and V-100 were precisely built in Germany to deal with the new Russian destroyer generation and were capable of 35.5 knots. But they only totalled eight 88 mm guns, twelve torpedo tubes between them. Novik’s captain was confident, with motivated, eager and well drilled crews. They were in the best boat of the Baltic fleet and knew it. At last, Novik caught sight of the two fleeing black “toothbrushes” and was first to open fire from 8,700 m. The enemy destroyers turned around to present theior best broadside and close the distance to respond, but at that range it was still ineffective. Their own spotters soon realized with what destroyers that had to deal. At the third volley, Novik found its mark on V-99 and switched to rapid fire. Gunners swated hard to load and shoot faster than in training.

A cloud of smoke and steam enveloped V99, hit several times. A fire broke out on her quarterdeck, her funnel fell, and from her stern a ball of flames erupted. V-100 put up a smokescreen to cover her retreat, stopping the engagement for a withdrawal. Novik concentrated on V-100 next, and quickly set it on fire in turn. Enemy firing became erratic and Novik maneuvered, hoping to drive them into the Russian minefield, succeeding in this. V-99 soon hit two mines in succession and rapidly sank. V-100, badly damaged, however made good her escape damage, joining the cover of the main forces. Novik suffered no loss or any hit and came back a war hero. The ship commander, Berens, and artillery officer, Lt. Fedotov were awarded the Order of St.George.

Novik went on her operations of minelaying notably in the Irbensky Strait, Libaya and localized minefield to deny the German fleet any passage in the Gulf of Riga. By September 15-21, she had her propellers repaired in drydock, after being damaged on August 4 during the explosion of a 12-in projectile astern during one of her sorties, when straddled by a German dreadnought. On September 25, near Odensholm, she recured pilot Musgyats as his hydroplane crash-landed nearby. On October 29-30 and November 22-23, she sorties with Gangut and Petropavlovsk, providing cover for the 1st minelaying division operating near Gotland. Later she took part in yet another a raid on German patrol ships, in the central Baltic. On December 24-25, she towed the damaged destroyer Zabiyaka after the Revel raid, which hit a mine near Dagerort.

Further operations (1916)

This victory was followed by a series of no less outstanding combat successes of the brand new destroyer. Novik became soon a household name, its successes reported to the Tsar. On the evening of November 7, 1915, Novik discovered the patrol vessel SMS Norburg near the Spon Bank and in less a minute, paralyze her with rapid fire followed by a torpedo hit which sent her to the bottom.

As the Baltic Fleet intensified its minefield operations, Novik was always at the lead, and always acted independent action, being the most active ship in these campaigns. Night minelaying required still great skills from navigators, maneuvering in unknown areas and the ability to extract from the German, and their own minefields.

But to be effective these minefields had to stand in the most unexpected places. As dusk fell, the special detachment received a radiogram from the fleet commander that by the evening of December 4, 1915, Bremen cruiser and a large destroyer were sunk, likely by Novik’s mines given their location. This added two more success and confirmed the path to maintain for a numerically inferior Baltic fleet. Instead of seeking a classic line engagement against a largely superior Hochseeflotte, a serie of hit and run operations such these became the accepted norm. And there was the construction of dozens of sisters of Novik on the way.

On the night of May 18, 1916, Novik, Grom and Pobedel, covered by the cruisers Rurik, Oleg and Bogatyr, made yet another raid on a German convoy in Norrköping Bay. The enusing battle, Russian destroyers launched their torpedoes and dispersed the 20 ships, and between them and the cruisers, claimed a German auxiliary cruiser, two armed trawlers and two merchant ships. On June 26, 1916, when crossing to Helsingfors near Nargen at 17 knots, she was grounded on rocky shoals. She was towed out by the icebreaker “Peter the Great” on the third attempt, towed to Helsingfors for repairs at Sandvik Dock, until August 13. From August 22, and until the end of the campaign she operated off Moonsund. On September 17-22, she sortied to look for U-Boats.

From October 4 to October 16, 1916, Novik was prepared for more sorties, but their were all postponed each time. On October 18, at 7:30, she sailed with the semi-division for a raid on the Memel area. A storm had the ships soon rolling up to 36° forcing them to slow down and reverse. On October 19, they made another sortie to Moonsund. On October 23 and November 10, two more minelaying missions were successfully done. More German vessels were sunk, but of less importance. On December 2, after another canceled operation while back off Reval, she collided with the minelayer Narova and her her stem bent. She was repaired from December 4 to December 18, in Helsingfors. From December 21 she stayed for the winter in Reval.

In early October, he carried out a minelaying operation off the Steinort lighthouse, and searched for German destroyers in the area of Sarychesky lighthouse. On November 2, together with the destroyer Desna she sailed to Rogokul and on December, 12 moved to Helsingfors for repairs adn an overhaul.

Last wartime operations (1917)

In May 1917, she became flagship of the mine division of the Baltic Fleet. She took part in the defense of the Moonsund archipelago and by October 1917, took part in the Battle of Moon sund with the German fleet. Afterwards, she was sent to revolutionary Petrograd, and entered a drydock for repairs and by November 1917, a major overhaul, her crew learning that from October 25, 1917 she was now part of the Red Fleet. On September 9, 1918, she was decommissioned however (her officers and crew gone) handed over to the Petrograd port for long-term storage. The war ended and her fate in the civil war years, like the rest of the fleet, was all but uncertain.

Modernization and interwar career as Yakov Sverdlov

Until 1925, Novik was mothballed in Petrograd, but by order of the Revolutionary Military Council of the Republic, on December 31, 1922, she was renamed after the first Chairman of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee Yakov Sverdlov. The decision was initiated back in March 1921, in the 10th Congress, whien it was decided to revive and strengthen the fleet. On October 29, 1924, approved the allocation of funds for the complete overhaul of still extant Novik-style destroyers in the fleet.

This was the occasion for an overhaul, a complete refection after years of neglect, complete restoration, and on August 30, 1928, freshly painted anew, with her new name and red star on the bow, she became part of the Red Banner Baltic Fleet.

After indeed being laid up from 9 September 1918 to 1925 she was indeed extensively rebuilt between 26 September 1925 and 30 August 1929. Her rearmost twin torpedo tubes bank was removed, three 102 mm (4.0 in) guns relocated forward, a second 76.2 mm (3 in) “Lender” AA gun ounted aft of the quarterdeck (a problem of the rearmost 102 mm gun). The three remaining twin torpedo tubes bankis were replaced by triples, re-positioned. The bridge structure was completely redesigned and enlarged, the deckhouse aft of the fourth funnel elmininated and a new, larger deckhouse added about 30 ft aft of the fourth funnel. Masts were now tripod, re-positioned, the forward funnel heightened by 2 metres (6.6 ft).

Interwar Service

Fleet Exercises with the Red Banner Baltic Fleet marked her early interwar service. Decommissioned again from December 1, 1926 to August 30, 1929 at the Northern Shipyard it was decided during the ioverhaul and maintenance to convert her into a destroyer division command ship, requiring larger accomodations, dedicated rooms and larger crew. The modernization caused and increase to 1,771 tons standard and 1,951 tons fully loaded.

After further fleet manoeuvers and exercises from 1930 to 1937, she was overhauled again between 28 November 1937 and 8 December 1940. This included her machinery, with elements replaced or refreshed. She also obtained ip to four 45 mm (1.8 in) 21-K anti-aircraft guns but re-designated a training ship on 23 April 1940.

The same year it was decided to make another upgrade with her firepower enhance and taking a heavier displacement. The days of her record 37 knots were long gone. Her standard “best speed”, despite her machinery overhaul, was circa 30 knots.

Before invasion of the summer 1941, Yakov Sverdlov was part of the training squadron, Frunze Naval School and in late July she was moved to the 3rd destroyer division of the Baltic Fleet squadron, no longer training but now fully active again.

A short and deadly WW2 career

In the first two months she carried out escort missions and covered actions of the fleet, screening cruisers and looking for enemy ships and U-Boats. She also took part in fire support missions for the ground forces. Also in July she became shortly flagship of the fleet (“command post”).

As part of the 3rd Destroyer Division she covered the evacuation of the Soviet Navy from Tallinn to Kronstadt, Yakov Sverdlov escorted to the cruiser and flagship Kirov, under command of Captain 2nd Rank A. M. Spiridonov, ensured their breakthrough to a less exposed port.

On August 28, 1941, at 05:00, together with the rearguard destroyers, she was detached to the Soviet Estonian capital Port to evacuate city defenders.

At 16:00 on the same day, near Nargen Island, she was sailing to the northern part of the island with five minesweepers at the head of the formation, and then an icebreaker. The destroyer Yakov Sverdlov screened Kirov, followed by a submarine and the Flotilla leader Leningrad. She received an order to move to a new position slightly ahead, port side of Kirov when it happened.

The end and controversy

Describing the events immediately preceding what happened her indicated:

Approaching “to my place”, I was dumbfounded by events alternating with lightning speed – a semaphore was received from one of the minesweepers: “You have a floating mine on your nose. Dodge.” The port signalman reported: “Submarine periscope left 60 degrees.” Having found the periscope at a distance of 8 cables, I ordered Senior Lieutenant Orlov to open fire. At the same time, he gave the order to make bombs and had already decided to go to the boat in order to ram it and bomb it, when suddenly the starboard signalman reported: “Kirov has stalled.” Looking around, I found that the cruiser “Kirov”, moving at the slowest speed, lowered a Red Navy man onto the gazebo, who was cutting the minesweeping part with an autogen. At the same time, the commander of the signalmen’s squad reported: “To the left is the trail of a torpedo.” Having found a torpedo trail in 2-3 cables, I realized that I could do nothing more than sacrifice the destroyer. Besides, even if I wanted to evade it, I could not do anything in this position; I knew this as the former head of the department of torpedo firing.

-Captain A. M. Spiridonov’s report

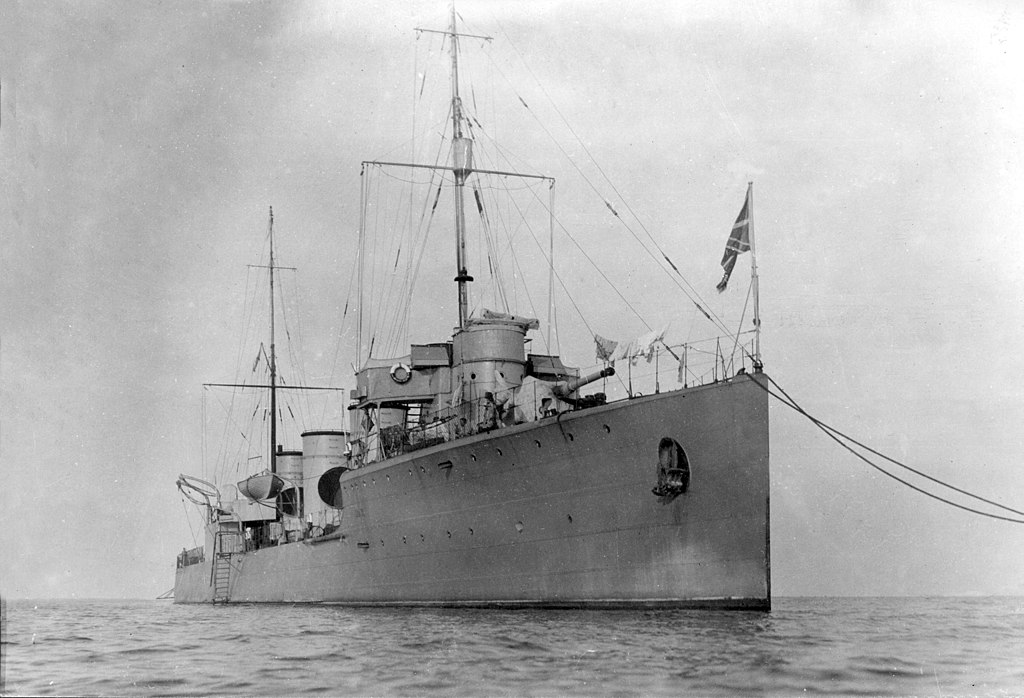

Sverdlov in 1940

Further events were witnessed not only by those who escaped Yakov Sverdlov, but also by sailors on duty aboard Kirov. According to Alexander Panasenko, a signalman from Kirov, warned that Yakov Sverdlov raised the dreaded “torpedo on the left” signal, compounded by its siren, and increasing speed, the captain, which flanked-guarded the flagship decided to willingfully take the torpedo himself, turning to the left and sparing Kirov. By all accounts by her sacrifice she saved the cruiser. If hit, Kirov, which was lightly protected against ASW threats, would have never reached Kronstadt and the flotilla could have lost her flagship.

A 2018 dive to the location and examination of the Yakov Sverdlov’s wreck showed the torpoedo hit her under the second funnel amidship. Due to the force of the detonation at this crucial point, she broke in half but did not sink immediately due to her excellent comparitmentation. This allowed part of the crew and refugee aboard to escape. According to Spiridonov report, the stern was still capable of moving independently, commanded by his assistant. Still 300 died: Circa 100 from her crew, 200 refugee from Tallinn (sources differs).

She sank 10 miles from the island of Mohni, resting for decades at a depth of 75 meters. Her bow was turned upside down exposing her keel, the stern however sank upright, still intact with guns and superstructure on an even keel. The soviet coat of arms was still clearly readable as her name. Many photos and a film were taken.

This put an end to a controversial theory about the origin of the torpedo. In fact she sat on the eastern edge of the German-Finnish Yuminda minefield, on the reported mine line D.27, and thus probably hit EMC mines (250 kg explosives), the Russian-Finnish also discovering three more wrecks of ships sunk during the Tallinn breakthrough. The location of the Yakov Sverdlov in a dense minefield is compounded by declassified German achives reported that not a single U-Boat was ever reported in the area of the Yuminda minefield during this breakthrough, due precisely to the danger of the minefield. This put an end to the long-maintained myth of the “her destroyer of the great patriotic war”. A nice story ideal for the propaganda of the time.

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign