Destroyer Dubrovnik (1931)

Dubrovnik was a British-built flotilla leader and one of the largest destroyers of the time. Although having some strong resemblance to British designs, she was entirely armed with Škoda 140 mm (5.5 in) guns, and the first of three, which ended the only one completed. While the old cruiser Dalmacija became a training ship, Dubrovnik became the ambassador of the young Yougoslavian Kingdom, known for her interwar peacetime cruises and state visits in the Mediterranean. By April 1941, she was captured by the Italians and recommissioned as Premuda, taking part notably in Operation Harpoon‘s convoy attack. Seized in Genoa aftert the Italian armistice by the Germans she was recommissioned as TA32 and took part in the Battle of the Ligurian Sea and ended scuttled in Genoa. Quite a career for an amazing destroyer.

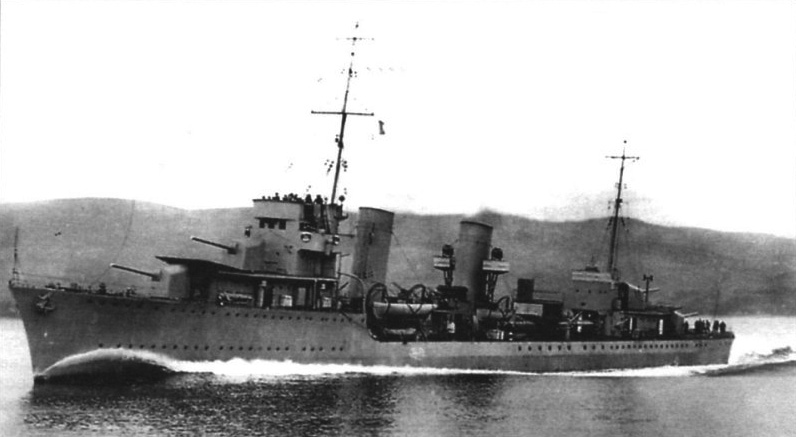

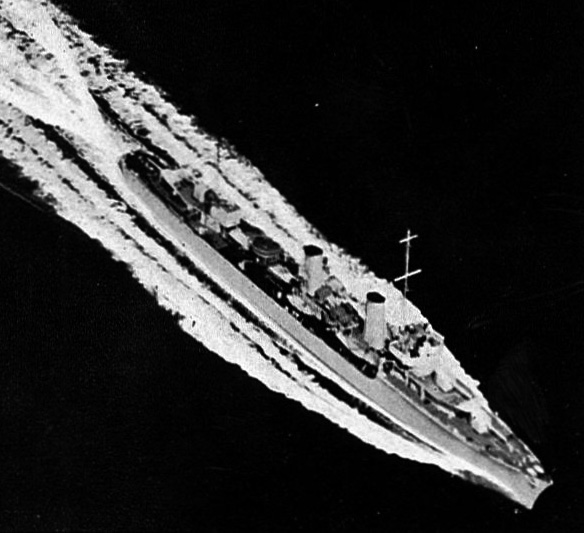

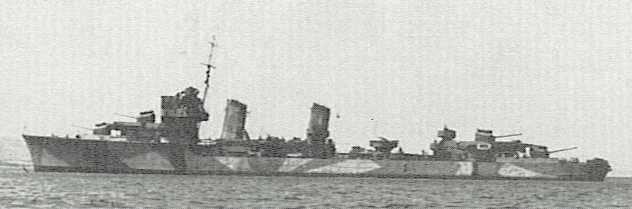

Dubrovnik in trials, 1932, she reached 40 knots in 1934. Photo used on most naval publications, including Conways.

Design development: A Scottish Toroughbred

The Royal Yugoslav Navy emerged, following the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, in what was at first called the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. The first navy was largely made of these Austro-Hungarian vessels, transferred sometimes to the great irritation of Italy. The Armistice of Villa Giusti, signed between Italy and Austria-Hungary on 3 November 1918 never implied this transfers triggering a deployment of Italian forces notably to Trieste, Pola, and Fiume and suggested by frogmen destroying Viribus Unitis (to be renamed Jugoslavija).

All battleships were interned in Italy the young Navy being left with 12 torpedo boats. This was barely sufficient for a coastal defence, and plans were soon drafted to acquire a better navy.

Dubrovnik in Kotor Bay, just arrived, late 1932.

The 1920s, the Yugoslav naval staff observed the craze for the flotilla leader concept, in which units of three large destroyers such as the French contre-torpilleurs could either led smaller destroyers or operate in half-flotillas to defeat light cruisers supposed to hunt down these destroyers. The RYN Navy soon wanted three of such flotilla leaders and insisted on the long endurance requirement, in order to act in the central Mediterranean, to bring help to the French and British Navy, given the aligmnent of Yugoslavia at the time.

In 1929, specifications had been drafted at last, as funds were secured since the economy improved from 1922, and at first a commission was sent to France to enquire about possibilities, but French shipyards at the time were alreay at full capacity. So, still wanting a French style heavy destroyer, the naval staff turned to Great Britain, and received a positive answer by Yarrow Shipbuilders in Glasgow, Scotland. They proposed their own take at the concept, based on their experience with 1918 flotilla leaders.

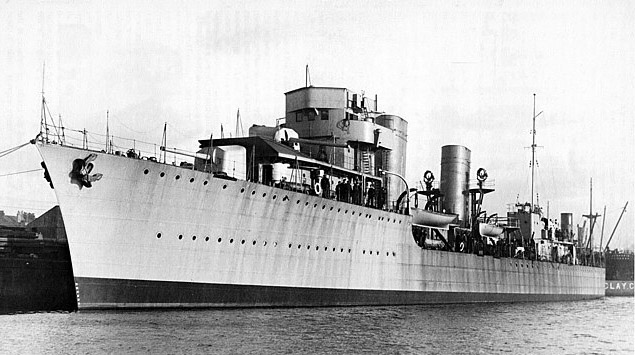

Dubrovnik in completion at Yarrow, 1932

Another points seen favorably by the Yugoslavian naval staff was that unlike French Yards, pushing to adopt their own guns, Yarrow had no problem ordering them at Škoda. This was mainly based on ordnance standardization, the army was in majority equipped with Czech artillery. The first Yarrow design proposed was simply an enlarged Shakespeare class, with five Skoda 14 cm/56 naval guns but recalculations showed it was dangerously top weighted. One gun was deleted and replace by a seaplane mounting and the final version replaced it with better anti-aircraft armament. The idea of mounting a floatplane on a destroyer was not new. The Dutch admiralty already adopted this solution for their Admiralen class used in East Asia’s KNIL. With large guns, it was certainly a plus for longer range artillery spotting.

In 1929, Yugoslavia signed a contract to build three flotilla leaders of this Yarrow design, all to be armed with Czech guns. In fact, Yarrow ordered all twelve 12 Škoda 140 mm (5.5 in) guns to have these delivered asap by July-August 1929. However in September-October in NyC the Wall street Crash coincided with the renaming of the former State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs (KSCS) as the Kingdom of Yugoslavia (3 October), while the lead ship of this class was named Dubrovnik. Soon the Great Depression hit Europe hard, and plunged the Kingdom into its own recession, preventing the construction of the other two destroyers.

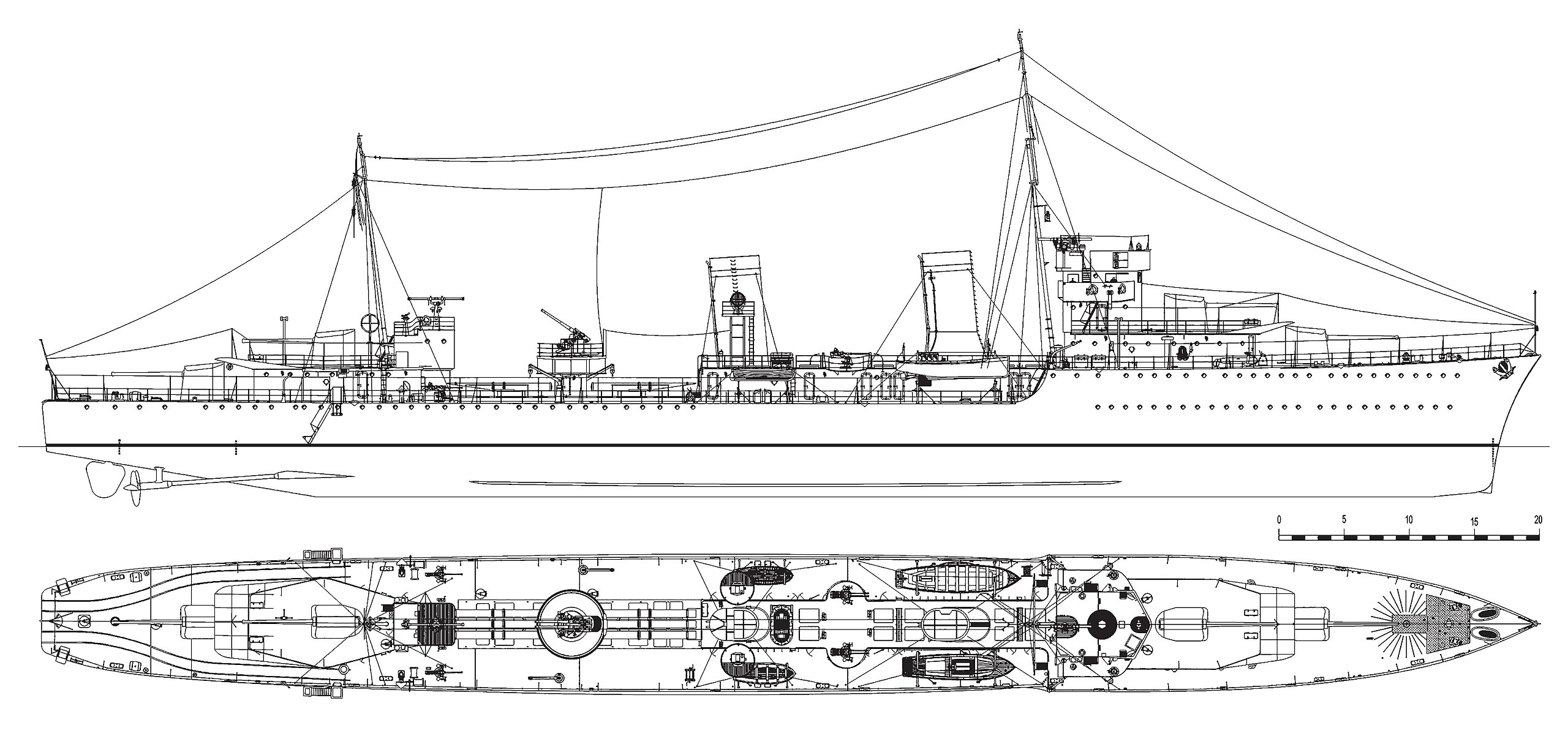

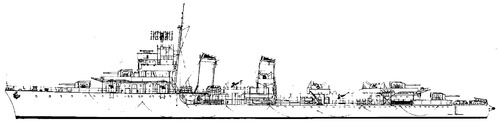

HD Drawing rendition of Dubrovnik (cc)

Detailed design

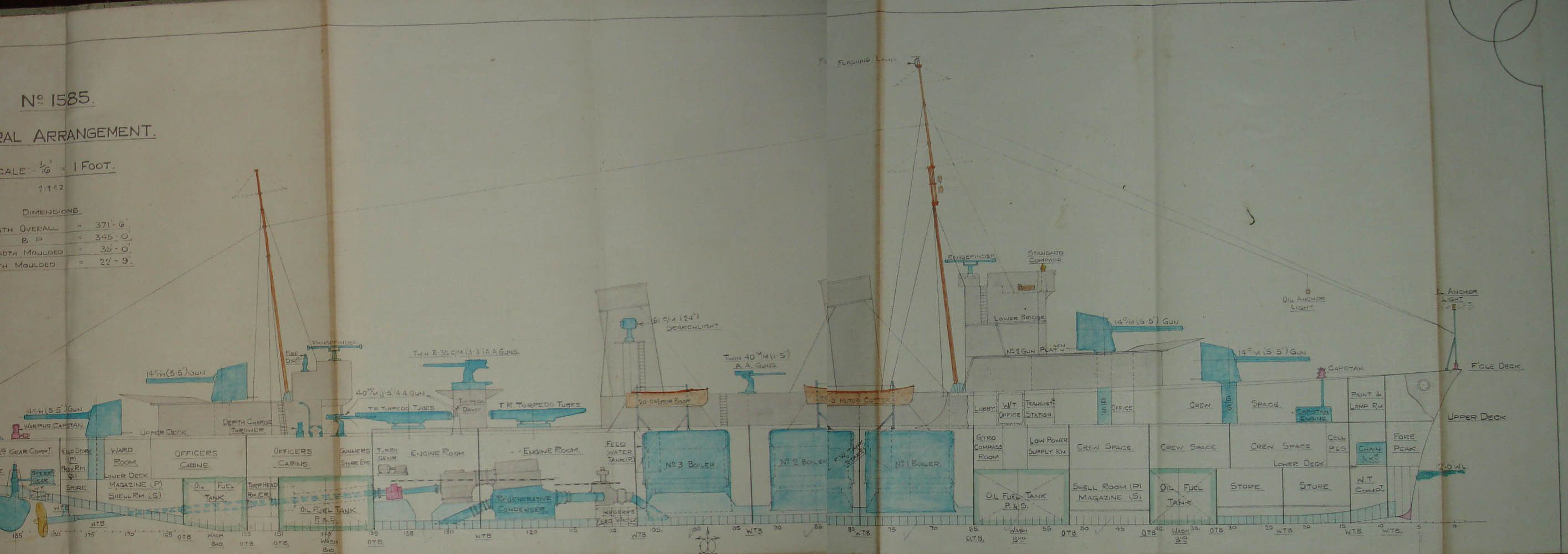

Yarrow Yard’s plans, courtesy of Marko Andrejevic.

HMYS Dubrovnik was designed by Yarrow very much in line with traditional British destroyer designs, with its typical boxy bridge and long forecastle, but sharper raked bow as the future Tribal class. It was usually straight. She also had a rounded stern with chutes designed to enable minelaying, with extensive railing running from the forecastle. She was longer than the average British destroyer of the time, at 113.2 metres (371 ft 5 in), still with a good lenght/width ratio of 1/11 with her 10.67 m (35 ft) beam and a light draft of 3.58 m (11 ft 9 in), up to 4.1 m (13 ft 5 in) when fully loaded. Standard displacement was 1,880 long tons (1,910 t), up to 2,400 long tons (2,439 t) fully loaded. Reactualized in German sources to 1,910 t Standard, 2,439 tons Normal and 2,884 tons at Full battle load.

Dubrovnnik in Den Helder, 1932 waiting for the completion of her electrical wiring and installations.

To give a comparison, a standard British Yarrow 1926 “A” class was 1200/1800 tonnes, 330 ft long. Yarrow’s Leader HMS Faulknor (1934) would only reach 2,000 tonnes FL. British destroyers would only reach these figures with the J-K-N class (1938). Also to compare, the contemporary (1930) French super destroyers such as the Aigle class were much larger, at 2,400/3,400 tonnes and armed with 5.5 in guns. She had two pole masts, raked, two raken funnels with projectors on derricks, four service boats on davits, a radio room aft, on the quarterhouse aft, and a classic profile with axial torpedo tube banks separated by a platform hosting AA guns. Her crew comprised 20 officers and 220 ratings, so 240 total, 1/3 more than the average British destroyer crew (140-170).

Propulsion

Full speed in 1932, official photo no.1615 Yarrow yard photo

Dubrovnik was powered by two Parsons geared steam turbines, connected each on a single propeller shaft. Naturally these turbines were fed by steam woming for Yarrow water-tube boilers in separate boiler rooms as ASW protection. The total was dimensioned for the large hull and to the total was rated at 48,000 shp (36,000 kW), 10,000 more than the average British destroyer. Up to that point she was the most powerful destroyer ever built by Yarrow.

Her designed speed was 37 knots (69 km/h; 43 mph) and she made extensive sea trials, after those in Scotland, in 1934, which was done with half-load and on pristine Adriatic sea conditions (flat as a lake), showing she could reach 40.3 knots (74.6 km/h; 46.4 mph). That was quite an argument to catch other destroyers (and potentially Italian light early Condotierri cruisers). For range, whioch was also an important requirement, the engine rooms were large enough to accomodate another novel feature: Yarrow proposed to install a completely separate Curtis turbine rated at 900 shp (670 kW) only and low revolution, intended for for cruising at 15 knots. It could be engaged or disengaged on the two shafts, to reach 7,000 nautical miles (13,000 km; 8,100 mi). For this, she also carried 470 tonnes (460 long tons) of fuel oil, which was in par with the average British destroyer’s provision at the time. The Yugoslavian admiralty was in any case quite pleased with the ship, even though she was alone.

Armament

Main Guns

Skoda 140 mm guns and Yugoslav Officers on deck during her stay in the Netherlands, Den Helder June 1932.

Dubrovnik was as planned armed with four Škoda 140 mm (5.5 in) L/56. They were in single mounts, shielded, in classic superfiring positions fore and aft. Superstructures for and aft had overhanging deflectors, but to protect from the elements and the deck gun crews from the blast of the upper guns. These Skoda 14 cm/56 naval guns were tailor-built by Škoda Works for export and sold to Yugoslavia for these large destroyers. All twelve were delivered to Yarrow and later shipped to Yugislavia. Some were kept as spares, the otherprobably converted in land defence use (fate unknown).

They were impressive ordnance for a destroyer, weighting 6,000 kilograms (13,228 lb) with a 7.84 meters (25 ft 9 in) long barrel, using separate-loading, brass case AP and HE shells weighting 39.8 kilograms (88 lb). The caliber was equivalent to the French 5.5 in. Rate of fire was 5–6 rounds per minute on average, at 2,900 ft/s and to 23,400 meters (25,600 yd) at max elevation.

For gunnery control, they had two (much probably Dutch) coincidence rangefinder with large span telemeters according to photos and plans. One was located on top of the bridge forward and the other atop the radio room aft, on the quarterdeck structure and behind the mainmast. Her electrical installations, sights and radios were also Dutch, installed while in Den Helder on her way south.

AA Guns

Air defence was also Czech-built: Two twin-mount Škoda 83.5 mm (3.29 in) L/35 guns installed on the platform in between the two torpedo tubes banks. It was complemented by six semi-automatic Škoda 40 mm (1.6 in) L/67 anti-aircraft guns also in two twin mounts, two single mounts located for the first in between funnels, with the latter on the main deck, abreast the aft control station. This was even completed by two Česká zbrojovka 15 mm (0.59 in) machine guns, likely in the bridge’s wings. This made up for an impressive battery for 1930. The average British destroyer had a single 3-in HA or two Pompom 2-pdrs. However by 1941 this AA battery was no longer adapted to 400 kph+ aircraft targeting. It was comprehensively modernized in Italian and German use (see later).

Torpedo Tubes

She was given two triple Brotherhoods 533 mm (21 in) torpedo tubes. They were placed aft, on the centreline, and manually reloadable. They fired the standard Whitehead 21″ (53.3 cm) Mark V (1918) used on British destroyers/ (Weight 3,828 lbs. (1,736 kg), 23 ft 3 in (7.086 m) long, powered by a Wet-heater to 25 kts for 13,500 yards (12,340 m) or 40 kts to 5,000 yards (4,570 m).

Zelenika (Bay of Kotor) 6 october 1934, King Alexander I Karađorđević is inspecting the ship. The depht-charge launcher and its reloads are well visible here.

Depth Charges & Mines

Dubrovnik was also fitted for anti-submarine warfare, with two depth charge throwers forward, abaft the bridge, and two depth charge racks aft with ten depth charges total. She also had railings on deck to carry and lay some 40 mines. However no photos shows her deploying these.

Construction

HMYS Dubrovnik was laid down on 10 June 1930 at Yarrow, launched on 11 October 1931, sponsored by Princess Olga (consort of the Prince Regent of Yugoslavia, Prince Paul). She was named after a famous and old city-state and port of Dubrovnik. The touristic and cinematic city regained fame during the filming of HBO’s Games of Thrones.

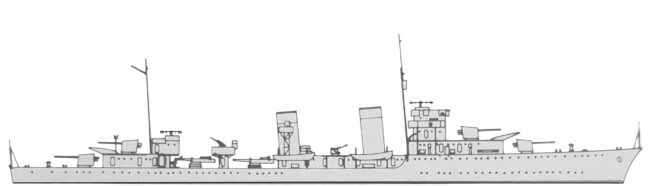

Conway’s rendition

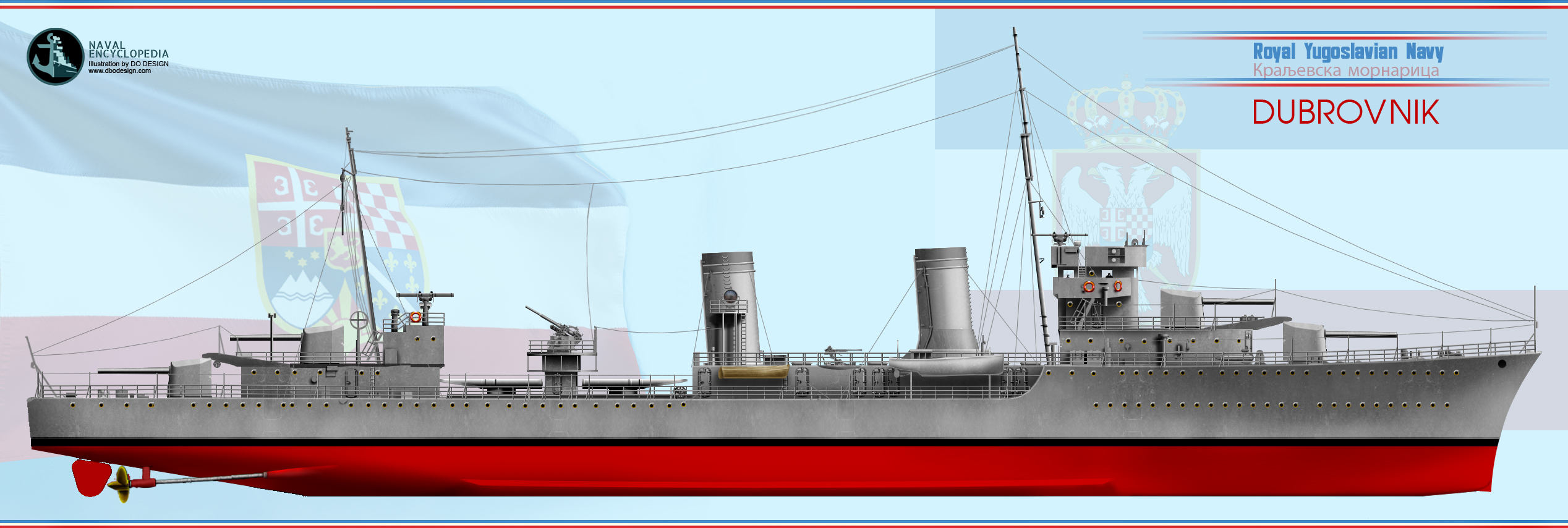

Author’s rendition (Premuda and TA 34 expected)

⚙ specifications |

|

| Displacement | 1,880 long tons/2,400 long tons |

| Dimensions | 113.2 x 10.67 x 3.58–4.1 mm (371 ft 5 in x 35 ft x 11 ft 9 in – 13 ft 5 in) |

| Propulsion | Two shafts Parsons turbines (48,000 shp (36,000 kW), 1 Curtis turbine, 3 Yarrow boilers |

| Speed | 37 knots (69 km/h; 43 mph) top, 15 knots (28 km/h; 17 mph) cruise |

| Range | 7,000 nmi (13,000 km; 8,100 mi) at 15 knots (28 km/h; 17 mph) |

| Armament | 4× 140, 2× 83.5 AA, 6× 40 AA, 2× 15 mm AA, 2×3 533 mm TTs, DCSs, 40 Mines |

| Crew | 20 officers and 220 enlisted |

The triple career of Dubrovnik

HMYS Dubrovnik (1932-41)

HMYS Dubrovnik (1932-41)

Dubrovnik upon arrival at Kotor, 14 July 1932

Dubrovnik was completed in Glasgow in 1932, just as her main and light anti-aircraft guns arrived from Czechoslovakia and were installed. She made inititial yard’s sea trials, in presnece of Yugoslavian navy officers as observers. When judged apt for the corssing, she sailed to the Bay of Kotor in the southern Adriatic to be fitted with her heavy anti-aircraft guns, late in delivery. She was commissioned officially in May 1932 with first captain was Armin Pavić.

By late September 1933, she left Kotor’s waters for the Dardanelles Straits and Romanian port of Constanța (Black Sea) to embark King Alexander and Queen Maria of Yugoslavia then on a tour. They stopped at Balcic, also in Romania, and Varna, in Bulgaria, and then sown south to Istanbul. They exited the straits and sailed to the Greek island of Corfu, Ionian Sea, and from there crossed south of the Peloponese and up to the otranto strait, then arrived at the Bay of Kotor on 8 October 1933.

On 6 October 1934, King Alexander left Kotor on Dubrovnik for a state visit to France. He arrived in Marseille on 9 October but was killed by a Bulgarian assassin the very same day, causing an international incident. Dubrovnik had to sail back with his body aboard to Yugoslavia escorted by French, Italian and British ships as atoken of respect. The state visit was important as they were to include defence contracts and a possible defensive alliance (notably against Fascist Italy). Vladimir Šaškijević became her new captain and the destroyer entered the drydock for a short maintenance.

Dubrovnik in Den Helder, June 1932

By August 1935, she visited Corfu and Bizerte (French protectorate of Tunisia) and by August 1937, visited Istanbul again as well as Mudros (northern Aegean), an stopped near Athens at the Greek port and naval base of Piraeus. Neutral, Yugoslavia was invaded by Germany and Italy by April 1941. Dubrovnik became flagship of the 1st Torpedo Division, leading her assigned destroyer unit composed of the three later built Beograd-class destroyers: Beograd, Ljubljana and Zagreb. Without clear wartime objective she stayed in Kotor, waiting for a possible arrival of the Regia Marina, but instead the city was captured by Italian troops on 17 April. They immediately captured the bulk of the Royal Yugoslavian navy.

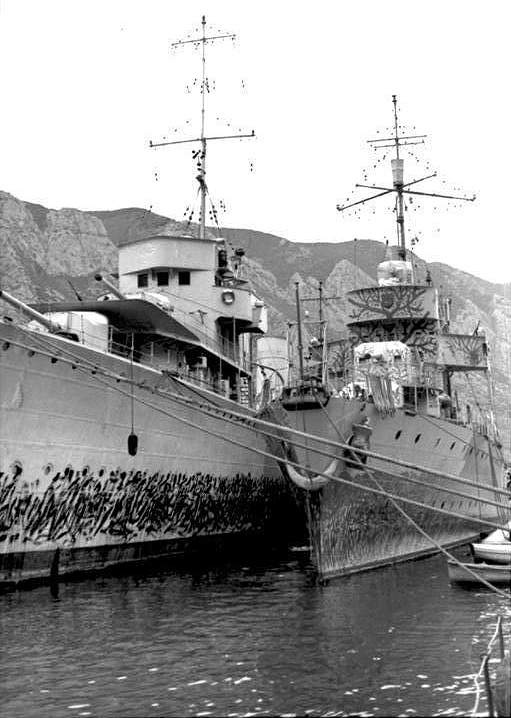

Dubrovnik captured in Kotor, in company of three Beograd class destroyers (Bundesarchiv). She was partially camouflaged (shielded by Beograd which was far more artistically camouflaged) with broom-made dark green bands to mix with the surrounding.

Premuda (1941-43)

Premuda (1941-43)

It seems he crew was absent that day as it’s Yugoslav civilians that tried to scuttled the ship (but failed obviously) when the Italian troops arrived. She was seized and under guard, received a small crew to be sent to Taranto, southern Italy on 21 May to receive a refit and put on Italian standards.

She was renamed provisionally Premuda (a Dalmatian island close to the sinking of SMS Szent István in June 1918). Son after, modifications were made, such as her aft deckhouse replaced with an extra AA platform, mainmast and funnels shortened. Her Škoda 140 mm were planned initially to be replaced by the brand new 135 mm L/45 guns (but this was not carried out). The twin 83.5 mm (3.29 in) L/55 were however replaced by a single 120 mm (4.7 in) L/15 howitzer, dedicated to firing star shells for night combat. Her six lighter Škoda 40 mm (1.6 in) L/67 were replaced by Breda Model 35 20 mm (0.79 in) L/65 (single mounts), searchlights were eliminated, a new director was fitted to the bridge. Towards early 1943 the 4.7 in howitzer was replaced by a twin Breda 37 mm L/54 AA mount. Her new crew comprised less men, 13 officers and 191 ratings. She was also camouflaged for the first time and typical red-white mrkings painted on deck to avoid aerial confusion. Still, her british profile was problematic as soon shown.

Premuda was ready for service and officialy recommissioned on February 1942. She rescued British POW after the sinking of SS Ariosto which was carrying them from Tripoli to Sicily. By June the submarine Alagi mistook Premuda for a British destroyer and fired but missed. However the torpedoes went on an struck the destroyer Antoniotto Usodimare (Navigatori class), sinking the latter. On 12–16 June 1942, she was deployed for the interception of the Allied convoy to Malta called Operation Harpoon, from Gibraltar. She was assigned to the 10th Destroyer Flotilla screening for the 7th Cruiser Squadron (Eugenio di Savoia and Raimondo Montecuccoli). The Allies that day lost several ships to air attacks but also two destroyers and four merchant ships in part by naval gunfire. The destroyer Ugolino Vivaldi (Navigatori-class) badly hit in an engagement with a British destroyer and tow to safety in Pantelleria, Sicily, by Premuda escorted by Lanzerotto Malocello.

On 6–7 January 1943 covered an important troop convoy to Tunis, with 13 other Italian destroyers. She made two more of such raids between 9 February and 22 March, and by 17 July, her captain reported engine problems as she was underway in the Ligurian Sea, off La Spezia. She sailed to Genoa for a major overhaul of her machinery, both boilers and turbines, and eventually it was decided that it would be more sensible to re-engined her as a Navigatori-class destroyer. She also was to received a wider beam for better stability and her initially planned 135 mm (5.3 in)/L45 guns in single mounts installed for good as ammo supplies for her original Skoda guns were running dry. More locations for extra Breda 37 mm and 20 mm was located, notably by eliminating her aft torpedo tubes, but these modifications were still projected when Italy surrendered to the Allies. Since this was a German-occupied zone, she was seized at Genoa (8 or 9 September), the largest war prize of the Kriegsmarine at that point. No doubt it was going to be put in good use.

KMS TA32

KMS TA32

TA-32 technical drawing, 1945.

Premuda now under Kriegsmarine control, started a third mutation and career. The Kriegsmarine saw the incomplete conversion and wanted her converted at first as a radar picket for night fighters. They planned to replace the Skoda guns by three standard 105 mm (4.1 in) L/45 anti-aircraft guns. More importantly she was to be given a Freya early-warning radar and the Würzburg FCS radar, plus a FuMO 21 surface fire-control system. However by early 1944 the axis lacked lacked destroyers for this theater and she was simply put to German standards recommissoned as a Torpedoboot Ausland or “foreign torpedo boat” (TA), fitted instead with a DeTe radar and Würzburg set. She was fitted four 105 mm (4.1 in) L/45 naval guns, and eight 37 mm FLAK AA guns in two quad mounts aft, plus as much as 32 to 36 Rheinmetall 20 mm (0.79 in) AA guns in both quadruple (Flakvierling) and twin mounts. As planned by the Italians, one torpedo tubes bank was disposed of to make room of extra AA, woth an extra two 37mm (four twin, two single). She also received six RAgg 8,6 cm rocket launchers. Her crew rose to 220 officers and ratings.

HMS Meteor (pictured) and HMS Lookout outgunned TA32 and her companions during the Battle of the Ligurian Sea in March 1945.

Recommissioned in the Kriegsmarine on 18 August 1944 as TA32 (Kapitänleutnant Emil Kopka) she served in the Ligurian 10th Torpedo Boat Flotilla. She was sent soon for a shelling mission on Allied positions on the Italian coast. Se also made scouting and minelaying missions, this time in the western Gulf of Genoa. On 2 October 1944 she was operating with TA24 and TA29 towards Sanremo again to lay a minefield when spotted by the USS Gleaves (Lead ship of her class).

The two exchanged fire and the Grrmans retired to Genoa. Other missions were planned, but it’s only by mid-March 1945 that a major sortie was undertook. The flotilla consisted of TA32, TA24 and TA29, last 10th TB Flotilla still operational. Due to the air superiority of the allies, this was a night mission, helped by radar.

On 17/18 March 1945, TA32 laid 76 naval mines off Cap Corse (orthern tip of Corsica) with TA24 and TA29 on the path of allied troopships to the Provence area of operation. They were detected a radar on shore and the local allied HQ directed the nearest ships available. These were HMS Lookout and HMS Meteor on patrol that day, which came first and directed by their own radars, found the flotilla and engaged them in what was the largely forgotten Battle of the Ligurian Sea. TA24 and TA29 were sunk but TA32 resisted, putting a firce defence and making an abortive torpedo attack, succeeding in escaping, her rudder damaged. At that point, she was waiting repairs in Genoa thzat never came. She was scuttled on 24 April 1945 as Germans forces retreated to the “Alpine Line”. Her wreck was raised and BU in 1952.

TA 32, ex-Premuda, ex-Dubrovnik raised in Genoa to be broken up (Reddit). See also

Read More

Books

Brescia, Maurizio (2012). Mussolini’s Navy: A Reference Guide to the Regia Marina 1930–45. NIP

Chesneau, Roger, ed. (1980). Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships, 1922–1946. London, England: Conway Maritime Press

Freivogel, Zvonimir (2020). Warships of the Royal Yugoslav Navy 1918–1945. Zagreb, Croatia: Despot Infinitus.

Jarman, Robert L., ed. (1997). Yugoslavia Political Diaries 1918–1965. Vol. 2. Slough, Berkshire: Archives Edition.

Lenton, Henry Trevor (1975). German Warships of the Second World War. London, England: Macdonald and Jane’s.

Nielsen, Christian Axboe (2014). Making Yugoslavs: Identity in King Aleksandar’s Yugoslavia. Toronto, Ontario: University of Toronto Press.

Novak, Grga (2004). The Adriatic Sea in Conflicts and Battles Through the Centuries Marjan tisak.

O’Hara, Vincent P. (2011). The German Fleet at War, 1939–1945. NIP

O’Hara, Vincent P. (2013). Struggle for the Middle Sea: The Great Navies at War in the Mediterranean Theater, 1940–1945. NIP

Rohwer, Jürgen; Hümmelchen, Gerhard (1992). Chronology of the War at Sea 1939–1945: The Naval History of World War Two. NIP

Sadkovich, James J. (1994). The Italian Navy in World War II. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press.

Tomblin, Barbara Brooks (2004). With Utmost Spirit: Allied Naval Operations in the Mediterranean, 1942–1945. University Press of Kentucky

Whitley, M. J. (1988). Destroyers of World War Two: An International Encyclopedia. NIP

Woodman, R. (2003). Malta Convoys 1940–1943. London: John Murray.

Links

https://web.archive.org/web/20200105223741/https://www.navypedia.org/ships/italy/it_dd_premuda2.htm

https://www.german-navy.de/kriegsmarine/captured/torpedoboats/ta/ta32/index.html

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Dubrovnik_(ship,_1931)

https://www.marina.difesa.it/noi-siamo-la-marina/mezzi/mezzi-storici/Pagine/PQRS/premuda_caccia.aspx

Model Kits

3D Rendition profile (see below)

Dubrovnik is an interesting subject as with some extra work, she can be the basis for the Yugoslavian original ship, camouflaged in 1941, or Premuda, or TA 32. Unfortunately i could not find any photo of her in Kriegsmarine service, showing notably her early 1945 camouflage. More so, i can’t find a kit. Scratch-built project then. Still, a 3D model was made, albeit lacking details.

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign

“On 6 October 1934, King Alexander left Kotor on Dubrovnik for a state visit to France. Her arrived in Marseille on 9 October but was killed by a Bulgarian assassin the very same day, causing an international incident. Dubrovnik had to sail back with his body aboard to Yugoslavia escorted by French, Italian and British ships as a token of respect. ”

In this part is wrong “Bulgarian assassin”, he wasn’t Bulgarian but Macedonian nationalist from VMRO who was helped by Croatian nationalists, Ustasha, who planed whole assassination.

He was a Bulgarian VMRO terrorist.

I love this site so please accept my comments as constructive criticism only.

Maybe it’s because I have a smaller screen on my laptop (15″), but the two columns of text are too close together which makes it difficult to read. I think your page layout would look better with just one column of text and larger images. That said, this article is a lot easier to understand than your past ones. Do you now have an English-speaking editor?

Hi Alex, thanks for this feedback. It can be that on some small resolutions the responsivness is not optimal, i’ll look at it and correct it, by taking the treshold further in larger refs, it’s easy.

Nope, i don’t have an english-speaking editor, it just don’t work in WP through the browser, even all-english. windows is to blame as i found. I hope i just do a little better gradually.

Thanks and happy Xmas !

Dave

Thank you for your reply! Merry Christmas to you too Dave.

Two corections:

1) Photo “Dubrovnik in Tivat, 1935” is not in Tivat, but in Den Helder, and not in 1935, but in june 1932.

2) Photo with “Duch officers”: these officers aren’t Duch, but Yugoslav NCOs.

These photos were all make in june 1932 during visit to Den Helder.

Fixed, thx !

One more thing. In the photo where “Dubrovnik” and “Belgrade” are captured, it is written that “Dubrovnik” is partially camouflaged.

Actually the whole ship was painted in a camouflage scheme except for the funnels and the bridge, but after the capture the Italians started to remove the paint. It is possible that the Yugoslavs did not have time to paint those parts of the ship, or the Italians took pictures of the ships only after removing the camouflage paint from the bow, since the photos show that the right side of the ship is stained, probably from the process of removing the paint.

“Belgrade” and “Zagreb” were definitely completely painted.

In the photo where “Dubrovnik” and “Belgrade” are next to each other, on the left side of “Dubrovnik’s” bow you can clearly see a partially applied camouflage scheme. It is possible that the paint was applied to the lower part of the bow, because there were tree branches on the upper part, with which the ship was additionally camouflaged.

But that’s why the rest of the entire surface area of the hull, the stern and the Škoda 140 mm guns are completely painted in this interesting camouflage scheme.

I have some interesting photos showing the camouflage scheme. How can I send it to you?

Hi Марко, many thanks for these precisions ! This photo indeed always intrigued me. If you have extra photos showing other angles that would be nice to make a rendition of this camo based on the profile i already created. You can send these via [email protected] or [email protected] (faster with the latter).

Best !

David

I sent to both addresses, but the second one wasn’t recognized as existing, so the email was sent only to the first address. 🙁

– Marko

Many thanks Marko well, received !

Dear Sirs,

Dubrovnik at full speed was not taken in 1936., but 1932.

This is according to the official photo no.1615 of Yarrow, original that I have.

Best regards,

Dragutin

Thanks for the update Dragutin, fixed !