Nuclear Attack Submarine 1958-1985.

Nuclear Attack Submarine 1958-1985.Cold War US Subs

GUPPY | Barracuda class | Tang class | USS Darter | T1 class | X1 class | USS Albacore | Barbel classUSS Nautilus | USS Seawolf | Migraine class | Sailfish class | Triton class | Skate class | USS Tullibee | Skipjack class | Permit class | Sturgeon class | Los Angeles class | Seawolf class | Virginia class

Fleet Snorkel SSGs | Grayback class | USS Halibut | Georges Washington class | Ethan Allen class | Lafayette class | James Madison class | Benjamin Franklin class | Ohio class | Colombia class

USS Seawolf (SSN-575) was the third of this name, and the USN second nuclear submarine, and a very interesting as she was the only one ever fitted with a Sodium liquid metal cooled beryllium-moderated nuclear reactor S2G. This was supposed to be the next gen “super-safe” reactor, but it was not to succeed. Her overall design called SCB 64A was a variant of Nautilus, but with many changes, including a new massive BQR-4 passive sonar giving her bow shape. After she received standard pressurized water reactor by 30 September 1960 she stayed in service until 1987 as one of the proud grandfather of the US nuclear fleet. #coldwar #usn #USNavy #unitedstatesnavy #submarine #nuclearattacksubmarine #ussseawolf

The second SSN

The early days of nuclear propulsion were exciting ones. Nothing was perfectly fixed it was more in the realm of experimentation since 1943 than an industrial reality yet. Thus, scientists had different ideas on how to implement fusion and cooling, and what solution to use for the best effect. The watercooled reactor has a massive problem (still acute today as Chernobyl and Fukushima showed): Once the coolant is no longer distributed due to energy drop or malfunction, the control bars starts to overheat and the reactor is ultimately condemned to explode. There is no “no-energy” solution to keep it under control. Using a solution where without energy the reactor would simply shut down naturally without consequences is much more appealing, both for civilian and expecially more for military applications, as for example a singlz depht charge blast could damage watercooling pipes or just shut down generators. WW2 showed how many times ships became sitting ducks after a powerful failure.

A short lived sodium-cooled reactor SSN

Thus, was designed the Submarine Intermediate Reactor (SIR) nuclear plant by General Electric at its Knolls Atomic Power Laboratory in the 1950s as an alternative. It wasprototyped in West Milton, New York and eventually designated “S1G”. When all tests were made and the reactor certified, it was adapted to submarine installation, and became the next SSN plan under the name of “S2G”.

This was a sodium-cooled reactor:

“Although makeshift repairs permitted the Seawolf to complete her initial sea trials on reduced power in February 1957, Rickover had already decided to abandon the sodium-cooled reactor. Early in November 1956, he informed the Commission that he would take steps toward replacing the reactor in Seawolf with a water-cooled plant similar to that in the Nautilus. The leaks in the Seawolf steam plant were an important factor in the decision but even more persuasive were the inherent limitations in sodium-cooled systems. In Rickover’s words they were “expensive to build, complex to operate, susceptible to prolonged shutdown as a result of even minor malfunctions, and difficult and time-consuming to repair”.

-Atomic Energy Commission’s Historian

Indeed this new reactor was a one-off experiment. It was just too complex to be installed aboard a submarine and dismissed by Hyman G. Rickover -The father of USN subs- himself.

It was in fact replaced after sufficient operations with the same S2Wa carried by USS Nautilus when drydocked on 12 December 1958. What was left was an advanced sonar and other innovative systems.

Other innovations

The Seawolf, SSN-575 however shared the same basic “double hull” twin-screw (dimensions diverged a bit). It was fully armed and operational but like USS Nautilus stayed largely an experimental vessel, presented however like a new generation of “hunter-killer submarine”, but she was in reality a single test platform for the S2G LMFR reactor and test new sonars. It had another refit and role change again to prolongate her active life now she was obsolete (no teardrop hull, many systems now superseded) and was refitted in 1971 – 1973 with a new light water system and noise reduction measures to be used for covert operations in foreign waters. All her long active life was that of a testbed submarine, more than an operational boat, albeit she took part in some fleet exercises.

Construction

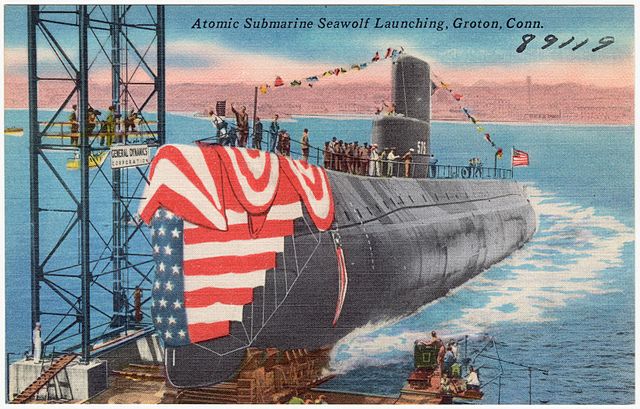

Launch Ceremony. Mrs. W. Sterling Cole, wife of congressman from New York, when christening the Seawolf failed to break the bottle and it slipped out of her hand. Old salts saw it as a bad start, but despite her three reconstructions and many dangerous operations later in her life putting the crew to high stress, she always came back home.

Both Nautilus and Seawolf were part of the FY52 programme. USS Seawolf’s keel was laid down 7 September 1953 at Electric Boat, General Dynamics, Groton, Connecticut, one year after Nautilus (laid down 14 June 1952). She was launched on 21 July 1955, sponsored by Mary Elizabeth (Thomas) Cole, wife of New York Congressman W. Sterling Cole, as the boat’s name did not referred anyone. She was commissioned on 30 March 1957, two years after Nautilus, but still under supervision of general manager Bill Jones. He had his officers modified to house different teams in the same space, Rickover’s, Navy observers, but also the Atomic Energy Commission and its independent labs. Given the complexity of both Nautilus and this new project, teamwork was required.

The Power Plant Project manager Dennis B. Boykin III however led his own division concerning the power plant installation and was back in the same yard for the reactor conversion, succeeded by Gardner Brown. Lieutenant James Earl “Jimmy” Carter for the anecdote was to be his Engineering Officer but resigned his commission after learning the death of his father in 1953.

Design of the class

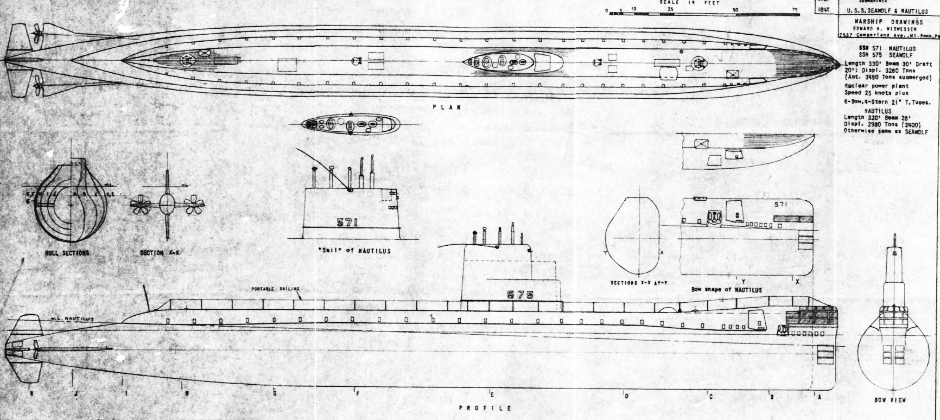

general schematics, reconstituted. Seems the originals were not declassified yet. Note also the Nautilus kiosk to compare.

Hull and general design

USS Seawolf, a name very much intended to underline its “hunter killer” role, less experimental/grounbreaking than “Nautilus”, was a clear sign sent to USSR by Eisenhower. But she still reproduced the hull of Nautilus to gain time, changing only details. The new submarine was however different in mensurations and tonnage. At 3,260 tons surfaced (vs. 3,530t) she was lighter but had more internal capacity and ended at 4,150 tons submerged (vs. 4,092t). She was ended longer than nautilus at 337 ft (103 m) and even longer at 387 ft (118 m) post conversion. She became the largest submarine ever built anywhere, although still a bit shy of the WW2 IJN STO class. Her Beam was of 28 ft (8.5 m) and Draft of 23 ft (7.0 m) versus 26 ft (7.9 m) in draft for Nautilus, but the beam was identical and both had the same hull design overall, jusy stretched on Seawolf for the new, more complex reactor.

USS Seawolf, a name very much intended to underline its “hunter killer” role, less experimental/grounbreaking than “Nautilus”, was a clear sign sent to USSR by Eisenhower. But she still reproduced the hull of Nautilus to gain time, changing only details. The new submarine was however different in mensurations and tonnage. At 3,260 tons surfaced (vs. 3,530t) she was lighter but had more internal capacity and ended at 4,150 tons submerged (vs. 4,092t). She was ended longer than nautilus at 337 ft (103 m) and even longer at 387 ft (118 m) post conversion. She became the largest submarine ever built anywhere, although still a bit shy of the WW2 IJN STO class. Her Beam was of 28 ft (8.5 m) and Draft of 23 ft (7.0 m) versus 26 ft (7.9 m) in draft for Nautilus, but the beam was identical and both had the same hull design overall, jusy stretched on Seawolf for the new, more complex reactor.

USS Seawolf carried a crew of 101 officers and men, about the same as for Nautilus (105: 13 officers, 92 enlisted). They shared accomodations which repeated Nautilus internal arrangement, also to gain time in design. There was no experience return when her construction started.

Her other big difference with Nautilus was a more advanced, stepped conning tower, the best in design at the time, experimented on the GUPPY. The staff gathered not in the upper, but lower part in the step, protected by a large plexiglas bubble, retractable entirely to avoid drag, and bridge access trunk in the fin.

Powerplant

Left: comparatives of the the seawolf prior and after reconstruction of spec ops, on HI sutton. As said above, the initial Westinghouse SIR Mk II reactor (Navy denomination S2G) was tested for a short time, proved too complex for military applications and thus during a refit (see later) replaced by the simpler S2Wa in 1960. This however needed to streched the hull to install it; It was powering geared steam turbines of the same type as Nautilus, driving two shafts with the same propellers agains, and for a total output of c15,000 shp (11,000 kW). This procured a top speed of 23 knots (43 km/h) surfaced, 19 knots (35 km/h) submerged. Figures before the conversion are still top secret. This was the same as Nautilus.

Left: comparatives of the the seawolf prior and after reconstruction of spec ops, on HI sutton. As said above, the initial Westinghouse SIR Mk II reactor (Navy denomination S2G) was tested for a short time, proved too complex for military applications and thus during a refit (see later) replaced by the simpler S2Wa in 1960. This however needed to streched the hull to install it; It was powering geared steam turbines of the same type as Nautilus, driving two shafts with the same propellers agains, and for a total output of c15,000 shp (11,000 kW). This procured a top speed of 23 knots (43 km/h) surfaced, 19 knots (35 km/h) submerged. Figures before the conversion are still top secret. This was the same as Nautilus.

Later she also tested bow thrusters above her pressure hull (two forward and two aft) for precise manoeuvering, after her “spec ops” last overhaul of the late 1970s. During the same she was fitted with a DSRV for deep sea exploration, infiltration or rescue (see career for more details).

Torpedo Tubes

Despite her enormous size, USS Seawolf, like Nautilus, was armed the same, with six 21-inch (533 mm) torpedo tubes forward, behind sliding doors and with pneumatic systems to reduce noise.

These were Mark 50 torpedo tubes close together in the straight section of the bow, launching the trusted 21″ (53.3 cm) Mark 35 type (design 1946, service 1949) weighting 1,770 lbs. (803 kg) 13 ft 5 in (4.089 m) with a 270 lbs. (122.5 kg) HBX warhead, range 15,000 yards (13,710 m) at 27 knots. It used active and passive acoustic, spiral search. These tubes had two reloads each for 22 in all.

After her next refit in 1958-60 (new reactor) she was likely given updated torpedoes Mark 39 (1956) 1,275 lbs. (578 kg), 11 ft 1 in (3.378 m) long with 130 lbs. (59 kg) HBX warhead, 13,000 yards (11,890 m) range at 15.5 knots and Wire-guidance/passive acoustic sonar, far more accurate.

Sensors

She started her career with a brand new, innovative sonars:

BQS-4 bow sonar

An active/passive detection sonar comprising the AN/BQR-2 passive detection system and active detection capability plus BQS-4 active component (7 vertically stacked cylindrical transducers in the chin bow dome) to transmit active “pings.” It can operate in either automatic echo-ranging or old school “ping mode” if required.

BQR-4A sonars

Long range array sonar suite also used on the GUPPY class boats. Older model kept for redundancy.

BPS-12 radar

Medium-range surface search and navigation radar, modified BPS-5 raised by a periscope antenna.

BLR-1 ECM suite

Radar frequency tuner unit 90 MHz to 180 MHz, for AN/BLR-1 or AN/SLR-2 electronic counter measures receiver, British, adopted by the USN and soon obsolete.

In the 1960s her BPS-12 radar and BLR-1 ECM suite were replaced by a BPS-15 radar and WLR-1 ECM suite. In 1969 she lost her main BQS-4 bow sonar for a SQS-51 sonar while provision was made for a DSRV, and four side-thrusters added.

profile

⚙ specifications as completed 1957 |

|

| Displacement | 3,260 tons surfaced, 4,150 tons submerged |

| Dimensions | 337 x 28 x 23ft (103 x 8.5 x 7.0 m) |

| Propulsion | 2 shafts geared steam turbines, S2G reactor, 15,000 shp (11,000 kW) |

| Speed | 23 kts surfaced, 19 ks submerged |

| Range | Unlimited (c30 days operations without supply) |

| Armament | 6 × 21-inch (533 mm) torpedo tubes |

| Sensors | BPS-12 radar, BQS-4, BQR-4A sonars, BLR-1 ECM suite |

| Crew | 101 officers and men |

Career of USS Seawolf

USS Seawolf departed New London in Connecticut, on 2 April, making her shakedown cruise off Bermuda and back on 8 May. 16 May-5 August saw her travelling to Key West for her first fleet training exercises. On 3 September she crossed the North Atlantic for NATO exercises with other fleets, and was back to Newport, making a go and back underwater run all the way coast to coast, 6,331 nonstop. On the 4th, President Dwight D. Eisenhower was aboard for a short presentation cruise.

Atlantic and Mediterranean Operations

USS Nautilus and Seawolf in 1957

By November she sortied in the Caribbean for an exercise in November and next month entered her first restricted availability until 6 February 1958. She trained along east coast until early August and started another underwater cruise from 7 August to 6 October, over 13,700 nautical miles (25,400 km), an impressive feat earning her a Navy Unit Commendation. This time was indeed superior to the usual patrol time of any GUPPY class.

USS Seawolf however reported many issues with her reactor: It was too difficult to maintain, having unreliable superheaters which were rarely operational and construction of rolled steel vs forged steel were the main reason behind the way these superheaters were unable to provide a full capacity inside a submarine. The general conclusion was that it was unsuitable for use on a military submarine, better for a land plant and other applications. Thus, she entered Electric Boat’s drydock in Groton, by 12 December 1958 for a complete change of powerplant exhanging it for a S2Wa PWR. This conversion ended by 30 September 1960.

On 18 April 1959, the radioactive S2G plant was sealed into a 30-foot high stainless steel containment vessel, towed, then sunk 120 miles off the eastern coast of Maryland under a known 9,100 feet fault. The Navy was later unable to relocate the container but guaranteed the deterioration of the container was estimated longer than the radioactive material decay.

Back to operation, USS Seawolf made a three-week refrseher cruiser, qualifications, and by 25 October, November and December retirned to fleet exercises. By 9 January 1961, she was posted to San Juan for local operations and on the 25th was detached to look for the disappeared Portuguese passenger liner Santa Maria after her SOS, seized by pirates. She made contact off the coast of Brazil on 1 February, the ship latter surrendering in Recife. After training back on the east coast she started a two-month oceanographic voyage to Portsmouth in England and back to New London on 19 September 1961.

In 1963 she searched after the lost USS Thresher (SSN-593) and returned to fleet operations until April 1964. On 28 April she sailed to New London and the Gibraltar, the gate of the Mediterranean for a three month plus deployment with the Sixth Fleet. She screened and trained with USS Enterprise (CVAN-65) battle group alongside USS Long beach (CGN-9), and the also nuclear-powered USS Bainbridge (DLGN-25) to showcased the world’s first all nuclear task force. Beack to East Coast exercises until 5 May 1965 she had an overhaul at Portsmouth Naval Shipyard and standardized to SUBSAFE, a work going on until September 1966.

USS Seawolf left Portsmouth on 24 August 1967 for New London in Connecticut as new home port, made a refresher training in the Caribbean, weapons/sensors fill qualifications. She stopped at Charleston for a change of propellers and followed by sea trials. In 1967 she was back to home port and ventured off the coast of Maine in early January 1968 but was grounded, damaging her stern so she was repaired in New London and was back in operations on 20 March 1969, tested in the Caribbean Sea in June-July, then returned with the Sixth Fleet from 29 September to 21 December 1969.

Sailing with USS Essex

Pacific Operations as “spy sub”

Back to the East Coast by November 1970 she was homeported in the pacific, to Vallejo, California via the Panama Canal on the 17th and reporting to the Pacific Fleet. There, she was planned as a “spy submarine”, shadowing Soviet submarines and retrieving test weapons from the seabed or tapping communications cables.

For this, she needed an extensive overhaul, which started at Mare Island Naval Shipyard from 8 January 1971 to 21 June 1973:

She became in essence a ‘special project platform’ with a 52-foot hull extension, forward of the sail to house intelligence gathering equipment, an “aquarium” housing a VDS and retrieval equipment, jet thrusters fore and aft, saturation diver lockout, new gondola underneath the hull, retractable “skegs” for bottom station and move.

She was tested off Bangor, Washington state, and returned to Mare Island on 4 September 1973 for post-fixes. In 1974 post-conversion testing/evaluation was declared over, so she started her first Pacific Fleet deployment over three months, being awarded a second Navy Unit Commendation (detailed records still classified). In 1975 she was supervised by Submarine Development Group One for more covert opeartions, eanring a Battle Efficiency “E” for 1974-75.

In 1976 she won both a second Battle “E” and Engineering “E” for her second Pacific Fleet deployment for independent operations over three months, a 89 consecutive days underwater, setting another U.S. Navy record and 3rd third Navy Unit Commendation.

In 1977 she won a 3rd Battle “E” 2nd engineering “E” and for her third Pacific Fleet deployment with 79 consecutive days, earned a 4th Navy Unit Commendation and Navy Expeditionary Medal. In 1978, she started her fourth Pacific Fleet deployment followed by a well deserved overhaul. Many incidents were indeed reported with the reactor and oxygen systems. By February 1980 she had a turbine generator failing during sea trials and she was drydocked again.

Reconstitution of SSN-575 in Operation Ivy Bells, by Hi Sutton with gunnarson

In August 1981 she made her 5th Pacific deployment but systems were keep failing just out of obsolescence putting the crew’s morale close to breaking. During a mission however, USS seawolf managed to tap a submarine communications cable in the Sea of Okhotsk, but was trapped by an extreme storm shaking her enough for her skegs to dig deep into the seabed causing her reactor heat exchanger to be clogged with sand. The captain eventually decided to jettison her underbelly gondola and she lost silence, being detected by a Soviet fishing trawler. She however exited the area at full speed and arrived in international waters. No doubt the Kremlin took notice.

Back home by October 1981 she still received the Navy Expeditionary Medal for her efforts, but badly needed another overhaul.

Still in high demand though, this was cosmetic and by 1983 she condicted her sixth Pacific deployment over 76 days and back to Mare Island by May this year, being awarded a Navy Expeditionary Medal, Battle “E,” Engineering “E,” Supply “E,” Damage Control “DC” awards. In 1984, she out-done herself by a 93-day deployment, this time to the Western Pacific and was awarded her third Supply “E,” first Communications “C” Deck Seamanship Award which at least alleviate the high crew’s stress.

In April 1986, she departed for her last Western Pacific deployment, short, and was back to Mare Island by June and a decommissioning on 30 March 1987, after which she was stricken on 10 July and mothballed. After which she entered the Navy’s nuclear Recycling Program on 1 October 1996, completed by 30 September 1997.

Read More/Src

Books

Conway’s all the world’s fighting ships.

Breeder Reactor Programs: History and Status. International Panel on Fissile Materials.

Friedman (1994), p. 109. “Attempt to christen the Seawolf (SSN-575)”. NavSource Online: Submarine Photo Archive.

Pearson, Richard (16 March 1987). “Ex-Congressman W.S. Cole, Atomic Energy Expert, Dies”. Washington Post.

“James Earl Carter, Jr”. Naval History and Heritage Command. 19 October 1997.

Sontag, Sherry; Drew, Christopher; Drew, Annette Lawrence. Blind Man’s Bluff: The Untold Story of American Submarine Espionage.

The Boston Globe, 17 May 1980

Links

seawolf-ssn575.com – vets site

on militaryperiscope.com

on fissilematerials.org

On HI Sutton

on enseccoe.org/

on hazegray.org/

on navsource.org/

on navypedia.org/

web.archive.org/ submarinehistory.com/PresidentCarter.html

on wikipedia.org/

Accident on SSN 757

commons.wikimedia.org/ on USS_Seawolf_(SSN-575)

facebook.com group

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign