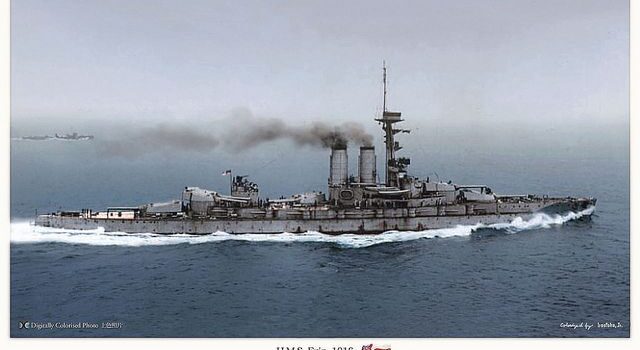

HMS Erin (ex-Reshadieh) 1913

HMS Erin (ex-Reshadieh) 1913WW1 RN Battleships

HMS Dreadnought | Bellerophon class | St. Vincent class | HMS Neptune | Colossus class | Orion class | King George V | Iron Duke class | HMS Agincourt | HMS Erin | HMS Canada | Queen Elizabeth class | Revenge class | G3 classMajestic class | Centurion class | Canopus class | Formidable class | London class | Duncan class | King Edward VII class | Swiftsure class | Lord Nelson class

Invincible class | Indefatigable class | Lion class | HMS Tiger | Courageous class | Renown class | Admiral class | N3 class

HMS Erin was a one-off dreadnought battleship ordered initially by the Ottoman from the Vickers Armstrong prior to the war, as “Reşadiye”, as part of a grand plan of modernization, and regain the advantage in the Ionian and Black seas. However, she was still not completed in August 1914, and Reşadiye was seized by order of First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill, notably as it was believed Turkey could have been a proxy to resell her to Germany or another central power. This move of course angered the Ottoman government but it only played a minor or not part in declaring war on the Triple Entente. Erin took pat in the Battle of Jutland in May 1916 and the Action of 19 August but her service in the North Sea was relatively uneventful and she was reduced to reserve, used in training ship by 1918, and as flagship of the reserve fleet in 1920 until sold for scrap in 1922.

A second rank Super-Dreadnought ?

Vickers Armstrong, atthe time the world-leading yard for dreadnoughts, was literally inundated with orders from across the globe, everybody but France, Germany, Austria, Italy and Russia wanted their share of the new “miracle battleship” than rendered all former capital ships obsolete overnight. More than a dozen dreadnoughts were on order after 1906. But there was a limited space available, and despite new yards were built, delays were encountered. Only a fraction of the ships had been delivered until the fateful summer of 1914. The Ottoman Empire was objectively at war with Greece in 1911-12. It also had a long standoff with the Russian Black Sea fleet and wanted to retake the advantage, modernize its fleet. German stepped in by 1910, and proposed two former pre-dreadnought, the future Barbarossa class (Brandenburg class ships).

Salamis, ordered in Germany in 1912.

But Turkey wanted already in 1911 one of these shiny new dreadnought, in case Greece obtained its own class from Germany (The Salamis class). Turkish authorities were well aware of the talks made by a Hellenic delegation to Vulkan AG. Indeed, their suspicions turned right as later the Salamis was ordered in 1912, then laid down on 23 July 1913 and effectively launched on 11 November 1914, but by this stage German took over the hull, which was never completed and recycled. Back in 1911, pourpalers were engaged with Vickers for two dreadnoughts. The delegation established on a rather large specification, so chief engineer Thurston presented a compromise design between King George V and Iron Duke classes, considered as “super dreadnought” with their larger calibre and five twin guns in the axis.

Sultan Osman I tugged for completion.

The first ordered on 8 June 1911 was Reshad V (current Ottoman Sultan, for an estimated cost of £2,500,000). She was later renamed “Reshadieh”, followed by Reshad-i-Hamiss, which was finally cancelled in 1912 as instead the Ottomans could acquire the well advanced Brazilian “Rio de Janeiro” then under construction as a complement for the two Minas Gerais, now in an arms race with Argentina and Chile, also built at Armstrong. After negotiations with Brazil, she was purchased, renamed Sultan Osman-I. No doubt the Greeks knew about it when ordering their own dreadnought, and plan a second.

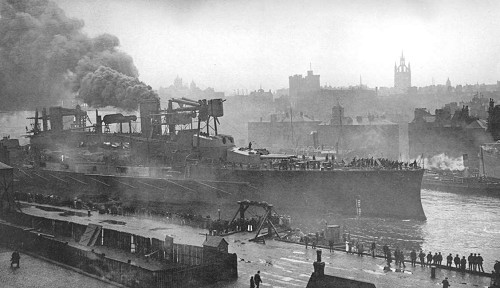

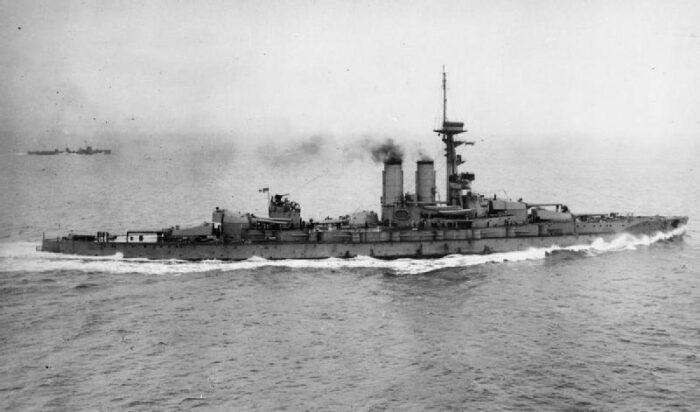

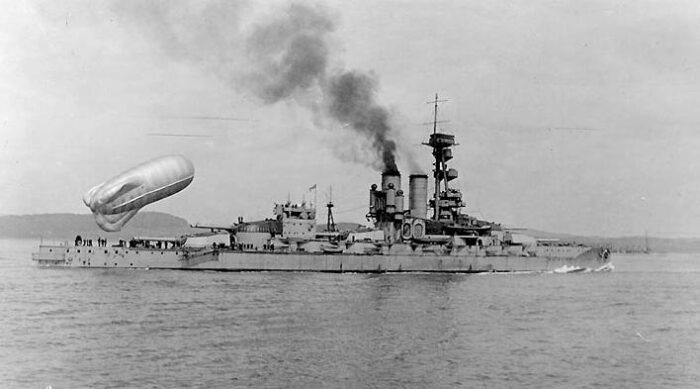

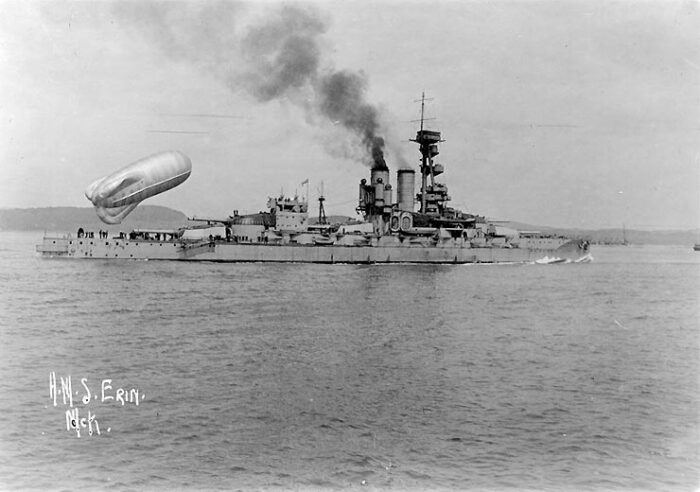

HMS Erin, in Moray, Firth of Forth 1915 – Credits: Imperial War Museum

Reshadieh was laid down at Yard 425 on 6 December 1911. But construction was suspended in late 1912 during the Balkan Wars as diplomatic rule in Britain prevented the sell of a warship to a belligerent nation. Construction only resumed in May 1913. She was launched on 3 September 1913, renamed, and scheduled for completion at the time of the Sarajevo bombing.

Churchill’s requisitions

But she was famously requisitioned in August 1914 by FLA Winston Churchill, with suspected a potential resell to Germany or at least justified the move i that sense, in a context of rising tensions in the Balkans and apparent shift of Turkey towards the central Empire. A decision that was criticized at the time and considered, rightly so, to anger the Ottomans; In fact this was part of a two-prone requisition, with the second, being Sultan Osman-I, which was later integrated into the Royal Navy as HMS Agincourt. The latter, named the “gin palace” due to all the broken glass and apparels when she fired a full broadside, could not have been so different from Erin. She was famously armed with a staggering array of seven twin turrets armed with 12-inches guns. Reşadiye and Sultan Osman-I were both requisitioned during their sea trials, after being detained on 29 july, by soldiers from the Sherwood Foresters Regiment. If Sultan Osman-I became Agincourt to commemorate the 100 years war victory, the second became HMS Erin, a dative name for Ireland (“Eire”).

But she was famously requisitioned in August 1914 by FLA Winston Churchill, with suspected a potential resell to Germany or at least justified the move i that sense, in a context of rising tensions in the Balkans and apparent shift of Turkey towards the central Empire. A decision that was criticized at the time and considered, rightly so, to anger the Ottomans; In fact this was part of a two-prone requisition, with the second, being Sultan Osman-I, which was later integrated into the Royal Navy as HMS Agincourt. The latter, named the “gin palace” due to all the broken glass and apparels when she fired a full broadside, could not have been so different from Erin. She was famously armed with a staggering array of seven twin turrets armed with 12-inches guns. Reşadiye and Sultan Osman-I were both requisitioned during their sea trials, after being detained on 29 july, by soldiers from the Sherwood Foresters Regiment. If Sultan Osman-I became Agincourt to commemorate the 100 years war victory, the second became HMS Erin, a dative name for Ireland (“Eire”).

Ottoman reactions

This takeover of course caused a stir in the Ottoman Empire. Indeed all newspapers the following day displayed big fiery titles as first page news. Indeed the ship were largely funded by public subscriptions due to the notorious indigent Court finances. The Ottoman government already was in a financial deadlock over their budget. Largely led by Turkish nationalists and a newspaper campaign, donations poured in Ottoman Navy from taverns, cafés, schools and markets, plus large private donations were rewarded with a “Navy Donation Medal”. This seizure, albeit the British Government officially prepared to refund the Ottomans, certainly angered the general public. But it was the donation of the German battlecruiser Goeben to the Ottomans after the escape of Admiral Souchon’s Mediterranean squadron, with the cruiser Breslau (later Yavuz and Midilli) which largely influenced public opinion in the Empire to turn away from Britain and eventually declaring on Britain and the Triple Entente.

This became for a long time a subject of discussions by historians as a critical factor. But there were no evidence fo thisn, at least official, apart newspapers of the time which reflected the general opinion, some aready calling for war. In fact, the Ottomans even offer to transfer Sultan Osman I (future Azincourt) to the Germans in early August 1914 if transferred, which justified after the fact, Churchill’s decision. Historian David Fromkin speculated this offer was made in exchange for signing a secret defensive alliance, extended after learning the seizure. The Ottoman government still was intent on remaining neutral so soon after a war with Greece. It was the news of Russian disasters after the ill-fated invasion of East Prussia in September 1914 that persuaded Enver Pasha and Djemal Pasha, Ministers of War and of the Marine, that Turkey could exploit a decisive Russian weakness. This was decided against the advice of other members of the government, and negociations with Vice Admiral Wilhelm Souchon, which became C-i-C of the Ottoman Navy was to help them attacking and defeating if possible the Russian blak sea fleet by late October. Souchon was also instrumental in this, as he was frustrated with Ottoman neutrality, and led his ship in a bombardment missions on Russian ports on 29 October, which further forced the government’s hand…

Design

HMS Erin was a very peculiar dreadnought, with a hull shorter but wider, than the usual practice, giving her a better stability as a gun platform and better maneuverability while being lighter of around 2,000 tons compared to the King George V/Iron Duke classes, last two classes of the “trilogy” or super-dreadnought, started with the Orions in 1911, that preceded the game-changing Queen Elisabeth class.

On the other hand, a smaller hull made for lower autonomy, although it was intended for use in the Mediterranean, and ultimately used cheaply in the North Sea. Her central main turret was raised and made less sensitive to spray, while her hull’s barbettes were better places and also less sensitive to heavy weather. She was the first British battleship also featuring a cresent stem, improving seakeeping, and systematically repeated thereafter. Scout cruisers already tested the concept.

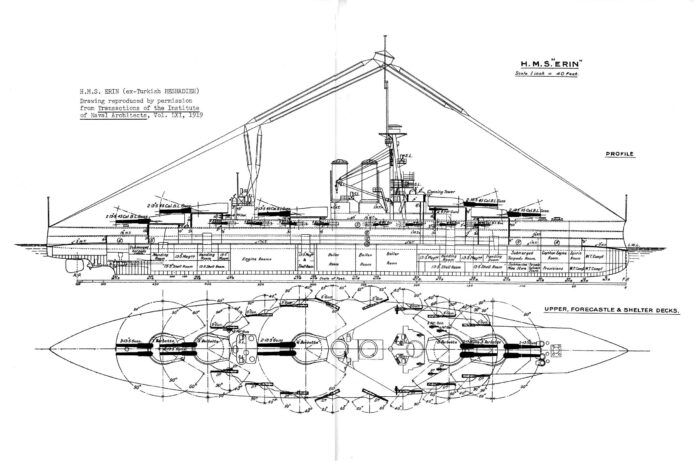

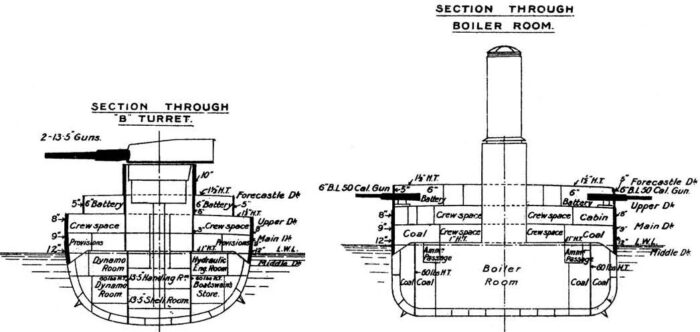

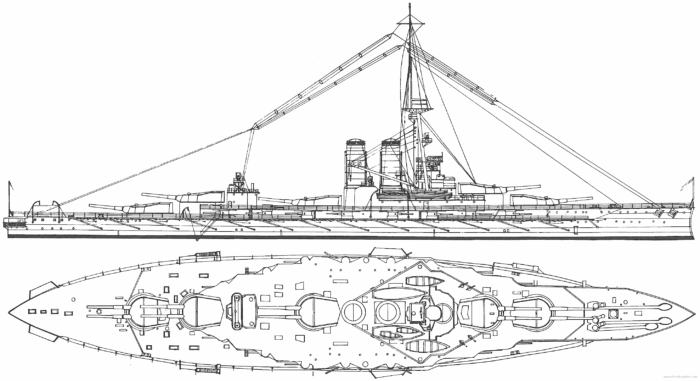

From warships international 1969 N°103 src

Hull and General Layout

Erin measured 559 feet 6 inches (170.54 m) overall for a beam of 91 feet 7 inches (27.9 m) and draught of 28 feet 5 inches (8.7 m) while displacing 22,780 long tons (23,146 t) at normal load and 25,250 long tons (25,655 t) deeply loaded. In 1914 she had a complement of 976 officers and ratings, 1,064 in 1915.

Powerplant

Erin had two Parsons direct-drive steam turbine sets mated on two shafts. Steam came from 15 Babcock & Wilcox boilers. The turbines were rated at 26,500 shaft horsepower (19,800 kW) for a designed speed of 21 knots (39 km/h; 24 mph). They carried both coal and fuel oil, making for best range of 5,300 nautical miles (9,800 km; 6,100 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph). This was a bit less than contemporary British battleships but still ok fpr opetations on the North Sea. It was originally designed for operatios on the black sea, which was about the same.

Protection

Erin had a waterline armoured belt that 12 inches (305 mm) in thickness protecting her vitals. Her decks were armoured from 1 to 3 inches (25 to 76 mm). The main gun turrets were protected by faces 11 inches (279 mm) thick, supported by barbettes 9–10 inches (229–254 mm) in thickness.

Details:

Belt: 12 in (305 mm amidship)

Armoured Decks: 1–3 in (25–76 mm flat/slopes)

Main Turrets: 11 in (279 mm)

Main Barbettes: 9–10 in (229–254 mm)

Armament

They were armed like the contemporary Orion class follow-up dreadnoughts, featuring five twin turrets, with an extra one amidship. In addition to these ten 13.5 in (343 mm) guns her secondary battery in casemates comprised sixteen single 6 in (152 mm) guns and to defend against TBs she possessed also six single 6 pdr (57 mm) guns on decks and four 21 in (533 mm) torpedo tubes as usual for battleline torpedoing, all submerged in the broadside, below the belt amidship.

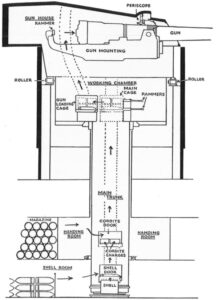

13.5 in (343 mm) guns

Erin was completed with a main battery of ten BL 13.5 in (343 mm) Mk VI guns* mounted in five twin-gun turrets: ‘A’, ‘B’, ‘Q’, ‘X’ and ‘Y’ in order from the prow. They were arranged in two superfiring pairs forward one aft of the main superstructure plus the fifth turret amidships between the funnels and aft superstructure, having a more limited arcs of fire, dictated by the shape of the structures and safety. If firing too close to them, damage was massive. This gave these ships a broadside of ten guns, chase and retreat with four, and depending on angles, up to ten guns also in intermediate arcs. The Mark VI were produced specifically for the Turks, so Vickers only delobered ten. There were no spares.

Erin was completed with a main battery of ten BL 13.5 in (343 mm) Mk VI guns* mounted in five twin-gun turrets: ‘A’, ‘B’, ‘Q’, ‘X’ and ‘Y’ in order from the prow. They were arranged in two superfiring pairs forward one aft of the main superstructure plus the fifth turret amidships between the funnels and aft superstructure, having a more limited arcs of fire, dictated by the shape of the structures and safety. If firing too close to them, damage was massive. This gave these ships a broadside of ten guns, chase and retreat with four, and depending on angles, up to ten guns also in intermediate arcs. The Mark VI were produced specifically for the Turks, so Vickers only delobered ten. There were no spares.

The BL 13.5-inch Mk VI gun were designed from 1911 and they were of a design similar to that of their 45-calibre BL 13.5-inch Mk V naval gun. The difference was their smaller chamber, meaning less propellant, reducing muzzle velocity by 55 ft/s (17 m/s) and range by 630 yards (580 m). Vickers manufactured the guns of X and Y turrets, Elswick Ordnance the guns of A, B, and Q turrets. At 10,000 yards (9,144 m) they could defeat 12.5″ (318 mm) or armour and 17.3″ (439 mm) on tests at point-blank range.

*Sources disagree on the number of each model of gun mounted on the ship, although everyone agrees that most of the guns fitted were Mk VI guns. Friedman claims that two Mk V guns were mounted to expedite completion but Campbell maintained she carried Mk V gus only for a time. Campbell and Friedman stated the Mk V guns on Erin were provided with reduced powder charges to match the Mk VI guns. Preston maintained they were all Mk VI guns. More

Specs BL 13.5 inch Mk VI gun

Mass: 46 long tons (46.7 t)

Length: 625.9 in (15.90 m) barrel 607.5 inches (15.4 m) 45 calibre

Shell: 1,400 lb (635 kg) 13.5-inch (343 mm)

Elevation: 0° – +20°

Muzzle velocity: 2,445 ft/s (745 m/s)

Maximum range: 23,110 yards (21,130 m) at +20°

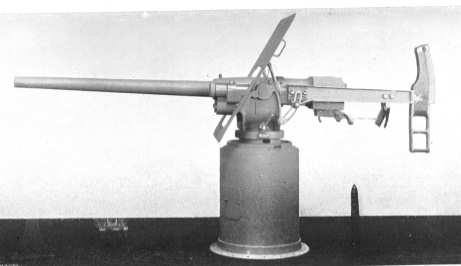

6 in (152 mm) guns

These were again one-off guns designed as equivalents to British ones for Turkish ships, Reshadieh and Sultan Osman I (ex-Rio). The latter had twenty of these Armstrong-Whitworth’s 6-inch 50 calibre guns, similar in design and characteristics to the 6-inch Mk XI in British service and used the same ammunition. Sixtenn were built for Erin as well. In British service they were designated BL 6-inch Mk XIII. They ended on gunboats later and were still in action in WW2.

These were again one-off guns designed as equivalents to British ones for Turkish ships, Reshadieh and Sultan Osman I (ex-Rio). The latter had twenty of these Armstrong-Whitworth’s 6-inch 50 calibre guns, similar in design and characteristics to the 6-inch Mk XI in British service and used the same ammunition. Sixtenn were built for Erin as well. In British service they were designated BL 6-inch Mk XIII. They ended on gunboats later and were still in action in WW2.

These guns were located on HMS Erin in the following pattern:

-Six in the forward recesses battery, firing forward

-Four on the broadside, abaft the main structure

-Six on the aft battery, facing aft.

Broadside was of eight guns.

Specs BL 6-inch Mk XIII

Barrel: 300 inches (7.620 m) bore (50 cal), 6 inches (152.4 mm)

Shell: 100 pounds (45.36 kg)

Muzzle velocity: 2,770 feet per second (840 m/s)

6 pdr (57 mm) guns

Classic Hotchkiss Naval Guns, patented in Britain and made by Elswick from 1884. Largely adopted by a wide range of cruisers and battleships.

Specs 6-Pdr 58 cal.

Mass: 821–849 lb (372–385 kg) barrel & breech

Length: 8.1 ft (2.5 m) bore 7.4 ft (2.3 m) 40 calibre

Shell: 57x307R 57-millimetre (2.244 in)

Breech; Vertical sliding-block with Hydro-spring recoil, 4 inch

Elevation: c30°

Rate of fire: 25 rpm

Muzzle velocity: 1,818 feet per second (554 m/s)

Effective firing range: 4,000 yards (3,700 m)

21 in (533 mm) torpedo tubes

As was typical for British capital ships at the time she had four submerged 21-inch (533 mm) torpedo tubes on the broadside, firing the Whitehead Mark I.

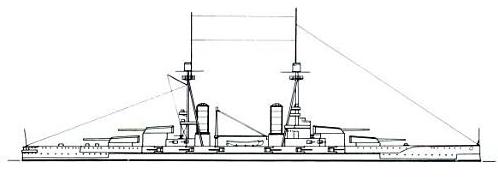

Author’s profile of the Erin in 1914.

Specifications 1914 |

|

| Displacement | 22,780 long tons normal, 25,250 long tons (25,655 t) deep load |

| Dimensions | 559 ft 6 in x 91 ft 7 in x 28 ft 5 in (170.5 x 28 x 8.7 m) |

| Propulsion | 4 shaft Parsons turbines, 15 Babcock & Wilcox boilers, 26,500 hp (19,800 kW) |

| Speed | 21 knots (39 km/h; 24 mph) |

| Range | 5,300 nmi (9,800 km; 6,100 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Armament | 5×2 x 13.5-in, 16×1 6-in, 6×1 6 pdr, 4x 21-in Sub TTs. |

| Armor | Belt 12 in, Decks 1–3 in, Turrets 11 in, Barbettes 9–10 in |

| Crew | Max 1070 or 976 (1914), 1,064 (1915). |

Modifications

HMS Erin in 1918 (the blueprints)

These combined qualities made it a good acquisition for the Royal Navy, which employed him extensively. When the Turkish government, this double requisition completed its hostility towards the British, which was illustrated during the bitter resistance it opposed to the Dardanelles. In 1917, Erin went into dry dock and received new rangefinders, deflectors and additional searchlights, and in 1918 two aircraft platforms were installed on the B and Q turrets.

-Four six-pdr were removed in 1915–1916, for a QF 3-inch (76 mm) 20-cwt anti-aircraft gun placed on the former searchlight platform, aft superstructure.

-The fire-control director for the main guns wa supdated and relocated on a tripod mast between May and December 1916.

-Two directors for the secondary armament were fitted to the legs of the tripod mast in 1916–1917

-An extra 3-inch AA gun was added on the aft superstructure in 1917.

-A high-angle rangefinder was fitted as well as flying-off platforms on ‘B’ and ‘Q’ turret roofs to launch spotting biplanes in 1918.

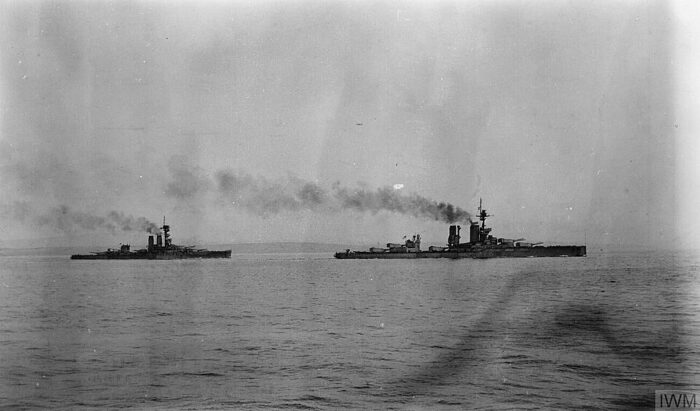

In September 1914, Erin was assigned to the 2nd Fleet Line Fleet of the Grand Fleet, for the North Sea. She was detached to the Firth of Forth to participate in the Battle of Jutland, where exchange fire for a brief moment, was hit, but without casualties. She became flagship of the Scapa Flow Reserve Fleet in 1919, but was sold for BU in 1922 due to the limitations of the Washington Treaty. The Royal Navy logically preferred recent, homogenous classes such as the Queen Elisabeth and Revenge.

Career of HMS Erin

Captain Victor Stanley became Erin’s first captain when, on 5 September, she entered officially Jellicoe’s Grand Fleet at Scapa Flow. She was assigned to the 4th Battle Squadron (4th BS) and like the others she departed Loch Ewe on 17 September for gunnery practice, west of the Orkney Islands on the 18th. Next, she started a collective sweep for German ships in the North Sea in bad weather. Back to Scapa Flow on 24 September, she refuelled and departed the next day for more target practice, west of Orkney.

By early October, she was part of a distant support fore in the North Sea for a large convoy of Canadian troopships from Halifax. She was then back to Scapa on 12 October, while soon after reports of U-boats in Scapa Flow led Jellicoe to build up ASW defences on the perimeter. On 16 October, he ordered the Grand Fleet dispersed to Lough Swilly in Ireland. He made another gunnery drill on 3 November and a battle exercise with the 4th BS until returning to Scapa six days later. On 22 November, he made another sweep in the southern half of the North Sea. Erin remained close to Vice-Admiral David Beatty’s 1st Battlecruiser Squadron. They were all back at Scapa Flow on the 27th. On 16 December she took part in the hunt after the German raid on Scarborough, Hartlepool and Whitby, and then another sweep of the North Sea on 25–27 December.

She was on gunnery drills on 10–13 January 1915 west of the Orkney-Shetlands and by the evening of 23 January, as the Battle of Dogger took place, the fleet rushed to help to Beatty’s battlecruisers, but it was too far away. On 7–10 March there was sweep in the northern North Sea and training manoeuvres, and the same on 16–19 March. On 11 April, a new sweep took place in the central North Sea and back on 14 April, the same on 17–19 April, followed by gunnery drills off Shetland 20–21 April.

There were more sweeps into the central North Sea, 17–19 May and 29–31 May while on 11–14 June, Gunnery and battle exercises off Shetland took place from 11 July. On 2–5 September same story, new sweep in the northern North Sea and gunnery drills. There were more training and sweep on 13-15 October and a large fleet training operation west of Orkney on 2–5 November. HMS Erin still without a proper overhaul, was reassigned to the Second Battle Squadron (2nd BS) in December.

Se took part in yet another sweep in the North Sea on 26 February 1916 and this time the Harwich Force was to catch any ship around the Heligoland Bight, albeit this was marred by bad weather in the southern North Sea, and instead the sweep was to the north. The one on 6 March but was abandoned due to sever ran squalls and heavy seas. Or the fleet would have departed without any destroyer escorts. On the night of 25 March, Erin and the fleet left again in distant support of Beatty’s battlecruisers and light forces engaged in a raid on the German Zeppelin base at Tondern. However, the opposing force already disengaged when the fleet arrives on 26 March. On 21 April, the Grand Fleet made a large scale exercises off Horns Reef to distract the Germans while the Russians laid new massive defensive minefields in the Baltic.

The fleet was back on 24 April to refuel and sail south, over intel. Reports of a new raid on Lowestoft, which was indeed performed well before the fleet arrived. On 2–4 May, the Grand Fleet made another diversionary action off Horns Reef. The fleet by late departed for yet another weep and demonstration, heading east while the Germans sailed to the south and the opposing fleets eventually met (or their vanguard forces would be more accurate) off the Danish coast. The idea of the Grand Fleet Commander Reinhard Scheer was to lure out and destroy a portion of the Grand Fleet.

He pressed the departure of all his Hochseeflotte, composed of 16 dreadnoughts, 6 pre-dreadnoughts and supporting ships, from the Jade Bight in the first hours of 31 May. Franz Von Hipper’s five battlecruisers were to take the vanguard, preceded by cruisers and high seas torpedo boats. U-Bootes were sent in advance. Room 40 (British naval intel) intercepted and decoded messages and informed the Admiralty, which ordered the Grand Fleet (28 dreadnoughts and 9 battlecruisers) to deploy before the German operation even begun, in order to create a giant pincer and catch the Germans when retiring, cutting them off and ideally destroyed the whole fleet in a decisive engagement all wanted on both sides.

This was the Battle of Jutland in which Beatty’s battlecruisers came in support of hard-pressed British cruisers and then managing to bait Scheer and Hipper onto the main body of the Grand Fleet. Jellicoe deployed meanwhile his battle lines, Erin being fourth from the head. Scheer spotted the Grand Fleet but managed to run over in poor visibility, and eventually Scheer disengaged under the cover of darkness. Erin only only fired 6 six-inch shells from her secondary armament, but no her main guns, a case unique during the battle. But the battle was over without achieving much, despite being taunted as the titanic clash of WW1.

The Grand Fleet made yet another sortie on 18 August in order to try to ambush the High Seas Fleet underway on the southern North Sea, but between miscommunications and mistakes the interception failed. Two light cruisers were sunk by U-boats and Jellicoe decided to not risk his fleet out of 55° 30′ North. The Admiralty confirmed the danger posed by U-Boote made any new sortie like earlier in the war, too dangerous to contemplate and it was agreed the Grand fleet would only sortie to counter the Hochseeflotte, and not being proactive. The case of an invasion of Britain was still considered. Meanwhile, on Erin, Captain Stanley was promoted to rear-admiral on 26 April 1917 and replaced by Captain Walter Ellerton.

In April 1918, the Hochseeflotte made a sweep against British convoys to Norway under Wireless silence. But Room 40 cryptanalysts managed to pick up disturbing intel still and warn Admiral Beatty, after SMS Moltke forced her radio silence due to her condition and folded back. Beatty, now at the head of the Grand Fleet instead of Jellicoe, ordered the Grand Fleet to interception, but it was too late.

Erin was mostly inactive for the remained of 1918 and was present in Rosyth, Scotland, when the surrendered High Seas Fleet arrived on 21 November. She remained with thee 2nd BS until 1 March 1919, and then under Captain Herbert Richmond assumed from 1 January 1919 and on 1 May, she was reassigned to the 3rd Battle Squadron. In October, she was placed in reserve at the Nore, but sent to Portland Harbour on 18 November. Captain Percival Hall-Thompson took command on 1 December and she was back to Nore by January 1920, as gunnery training ship from February. In June she became flagship of Rear-Admiral Vivian Bernard at the Reserve Fleet, Nore. In July–August 1920 she had her first and last refit at Devonport. She remained flagship until 18 December and as gunnery training ship, planned to remain so even under the Washington Naval Treaty of 1922, but HMS Thunderer was chosen instead so she was soon struck from the register by May 1922 and later sold to Cox and Danks on 19 December, BU in 1923.

Links & Sources

Books

Specs Conway’s all the world fighting ships 1906-1921 and 1922-1947.

Brooks, John (1996). “Percy Scott and the Director”. In McLean, David & Preston, Antony (eds.). Warship 1996.

Burt, R. A. (2012) [1986]. British Battleships of World War One. NIP

Campbell, N. J. M. (1981). “British Naval Guns 1880–1945, Number Two”. In Roberts, John (ed.). Warship V. London: Conway

Campbell, N. J. M. (1986). Jutland: An Analysis of the Fighting. NIP

Corbett, Julian (1997) [1940]. Naval Operations. History of the Great War: Based on Official Documents. Vol. III Imperial War Museum

Friedman, Norman (2011). Naval Weapons of World War One: Guns, Torpedoes, Mines and ASW Weapons of All Nations; An Illustrated Directory. Seaforth Publishing.

Fromkin, David (1989). A Peace to End All Peace: The Fall of the Ottoman Empire and the Creation of the Modern Middle East. New York: H. Holt.

Jellicoe, John (1919). The Grand Fleet, 1914–1916: Its Creation, Development, and Work. New York: George H. Doran Company.

Langensiepen, Bernd & Güleryüz, Ahmet (1995). The Ottoman Steam Navy, 1828–1923. London: Conway Maritime Press.

Monograph No. 12: The Action of Dogger Bank–24th January 1915 (PDF). Naval Staff Monographs (Historical). Vol. III. The Naval Staff

Parkes, Oscar (1990) [1966]. British Battleships, Warrior 1860 to Vanguard 1950: A History of Design, Construction, and Armament NIP

Silverstone, Paul H. (1984). Directory of the World’s Capital Ships. New York: Hippocrene Books.

Tarrant, V. E. (1999) [1995]. Jutland: The German Perspective: A New View of the Great Battle, 31 May 1916. Brockhampton Press.

Links

on maritimequest.com

on jutlandcrewlists.org/

on canakkale.gen.tr/

The St Vincent class Battlehips on wikipedia

On the Dreadnought Project

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign