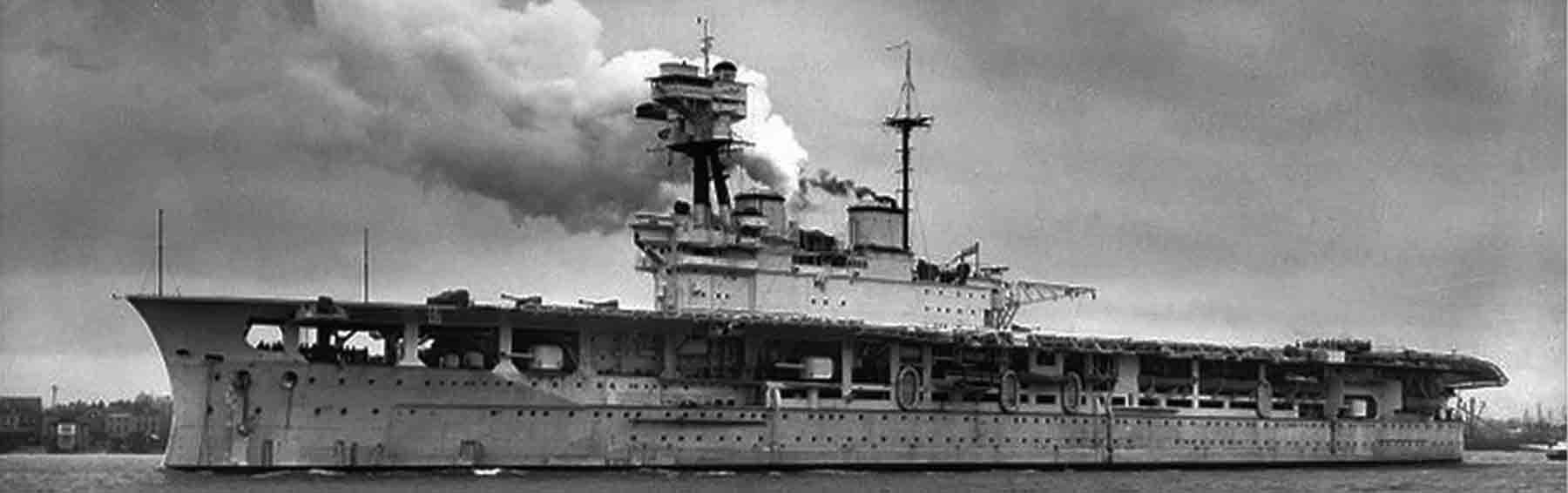

HMS Eagle (1918)

United Kingdom – Aircraft Carrier

United Kingdom – Aircraft Carrier

WW1/WW2 RN Aircraft Carriers:

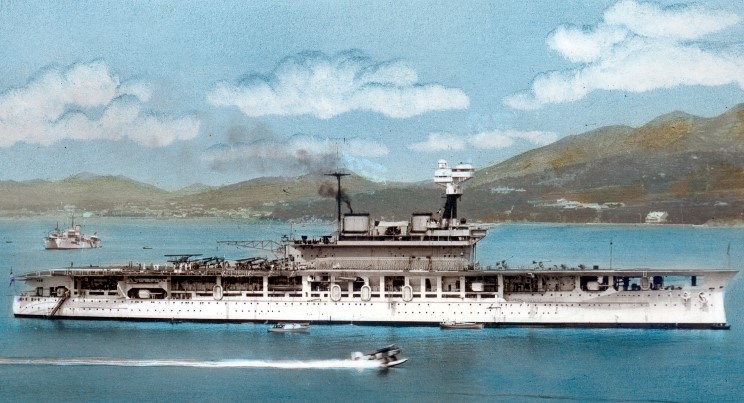

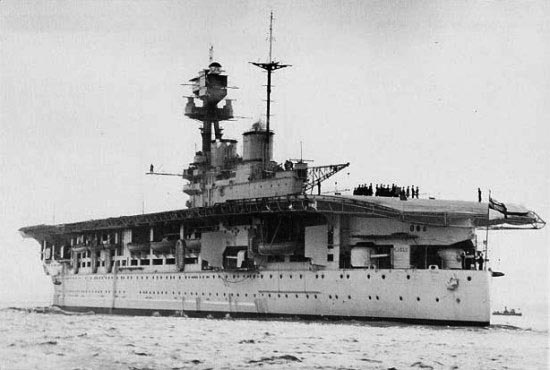

ww1 seaplane carriers | Ark royal (1914) | Campania | Furious | Argus | Hermes | Eagle | Courageous class | Ark Royal (1936) | Illustrious class | Implacable class | Colossus class | Majestic class | Centaur class | Unicorn | Audacity | Archer | Avenger class | Attacker class | HMS Activity | HMS Pretoria Castle | Ameer class | Merchant Aircraft Carriers | Vindex classHMS Eagle was the fourth British aircraft carrier to enter service, after the Furious, Argus and Hermes, and a compromise. Taking a massive dreadnought to carry 25 planes would seems ludicrous to us today, but there were little options at the time, but scrapping the ship entirely, instead of taking advantage of an hole in the naval disarmament treaty of 1922. A dreadnought, even devoid of its main battery, was still a serious proposition as a warship, at a time aviation was seen merely as an auxiliary for the fleet, mainly used for spotting and possibly “harassing” small ships. Before the experiments of Mitchell, the idea of sinking a battleship with planes was not taken seriously by any admiralties.

So we need to see the HMS Eagle in the context of the time, almost as an hybrid that needed to fight for itself in case of close combat, something provided by its 6-in barbette guns and strong armor. As a result, like most early conversions, in particular from battleships, the Eagle was not a satisfying solution, being too cramped to bring a potent air group, and too slow to follow modern battlelines with 30 knots ships. In WW2 nevertheless, she operated in many places from 1939 to 1942: Indian Ocean, Western and Eastern Mediterranean, even thesouth Atlantic from the West African coast and the East African campaign. Her air groups claimed more than a dozen of ships, most of the military, badly damaging many others, including during the famous raid at Tarento. She was sunk in 1942 during the battle of Malta after delivering a hundred of Spitfires, sea Hurricanes and other planes to the besieged Island.

The Chilean Battleship turned Carrier

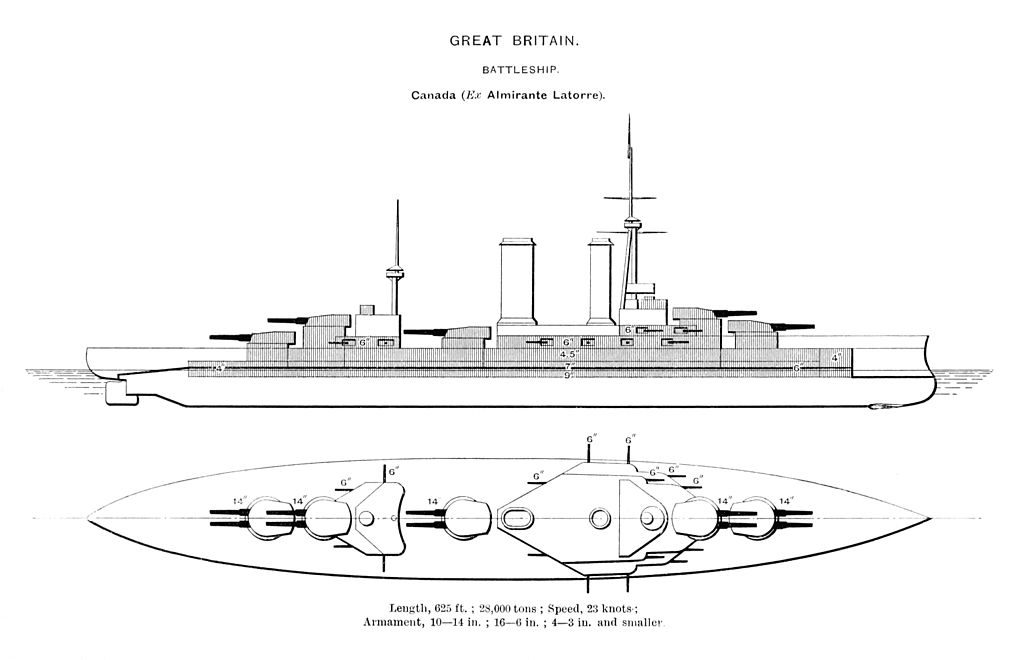

The Eagle was the result of those ships called upon at the top of the battleship era and in a climate of naval rivalry, caught up by the war, resulting of an amazing twist of fate afterwards. In 1910, Chile was the last of the three great naval rivals of South America to embark on the dreadnought race, after Brazil (with the Minas Gerais class) and Argentina with the Rivadavia class. One reason ws to wait for the budget, the other was to study both designs and answer with a superior one. Instead of sticking with the 12-in caliber, the Chilean admiralty, always very close to the Royal Navy chose to embrace the new caliber in development, 14-in (356 mm) for their Almirante Latorre class.

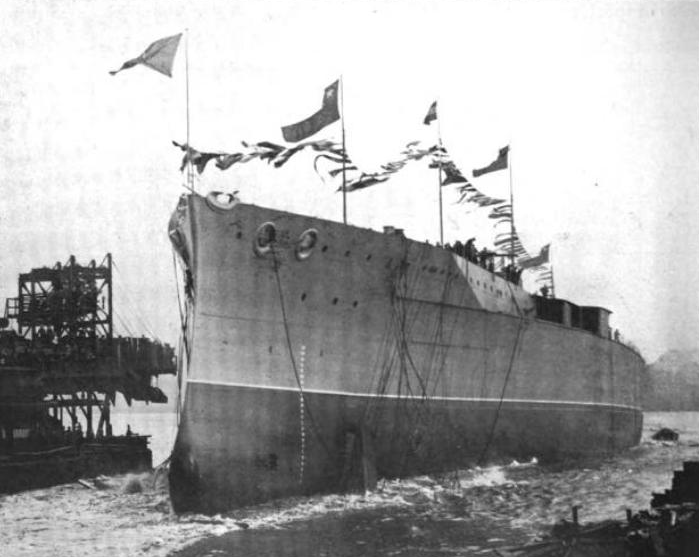

Long story short, both battleships were ordered on 29 July 1912 to British yards, and the second, called Almirante Cochrane, was laid down 20 February 1913 at Vickers Armstrong Whitworth yards. In August 1914, work had advanced well, but stalled completely. She was just month away to be launched, but decision was taken to requisition her sister, Almirante Latorre, to be completed instead and renamed HMS Canada. She would do a brillant career in the Royal Navy, including the battle of Jutland. After the war, she would be delivered back to Chile and stay active under this flag until the 1950s.

Launch of the Latorre, 1915

Meanwhile Almirante Cochrane was left as she was, her hull complete but missing her side armour and still not ready to be launched. Materials and personal has been requisitioned for other more urgent completion and would stay busy in maintenance and other constructions for the years to come. By the fall of 1917, the transformation of HMS Furious and various experiments with British seaplane and aircraft carriers conducted the admiralty to be more open to other quick conversion proposals.

Brassey’s design 1915. Impressive, contrary to the previous Brazilian and Argentinian ships she was considered a “super dreadnought”, faster and better armed.

Director of Naval Construction immediately thought the Cochrane, still officially the property of Chile, would do a good platform for conversion, as she was large, roomy and advanced enough. He delivered a proposal to the admiralty, and an outline design was ready on 8 February 1918. The admiralty was indeed interested to test the innovative design and 20 days later, on 28 February 1918, the request to the government to purchase the hull from the Chileans has been accepted, as well as the conversion. The Cochrane passed under the supervision of the Royal Navy, unnamed and noght in commission at this point. After many revisions and delays, completion would be effective on 20 February 1924, six years later.

Design specifics of the conversion

The first design proposal of late 1917 by the Director of Naval Construction was indeed quite singular and striking: She would have been the first and only carrier fitted with two islands, one either side of the continuous flight deck. Both islands, 110 feet (33.5 m) long would have comprised two funnels and a tripod mast, and were staggered to confuse submarine captains and ships spotters over the ship’s orientation. Both islands were connected with heavy bracing and the bridge mounted above, leaving 20 feet (6.1 m) of clearance above the flight deck. This intermediary space as defined was 68-foot (20.7 m) wide, with the aircraft lifted by the two elevators and assembled before taking off from there.

In addition as seaplanes were still important, a crane was fitted at the aft end of each island to operate these. To feed this air group, 15,000 imperial gallons (68,000 l; 18,000 US gal) were carried inside individual 2-imp. gallon tins stowed on the forecastle deck and under 1-in (25 mm) of armour plate protection. Two ready-use tanks near the islands were installed for quick refuelling of the planes. Armament was of course reduced to side sponsons, with guns under masks instead of barbettes, nine of the original 6-in guns plus four 4-in AA guns between the islands. The powerplant was left unchanged, but with increased quantities of fuel oil, coal still carried but also increased to 1,750 long tons (1,780 t) and 3,200 long tons (3,300 t) respectively.

In March 1918 however, there has been enough experience with turbulence and smoke on Furious from the pilots to decide to scrap the port Island. The ship would be more conventional, and the Island made slightly larger.

Trials on HMS Furious and pilots hearing went into reports, feeding the design staff on the Eagle, which recognised planes dangerously to turn to port when recovering from an aborted landing. This resulted in eliminating the port island altogether in April 1918. To cope with just one left, the remaining starboard island was made longer, at 130 feet (39.6 m) but it as also reduced in width by 15 feet (4.6 m). This minified air turbulence.

Prow of the HMS Eagle in the 1920s – Src: wrecksite.org

The island design was revised to include a more substantial bridge, the two truncated funnels and and enlarged single tripod mast which carried the fire-control directors. Admiral David Beatty, then Grand Fleet commander, insisted for the main armament to be increased to twelve 6-inch guns, notably one on deck, close to the island. He also insisted for eighteen torpedo tubesto be mounted in three triple fixed mounts per side. The idea was to prevent night German light cruisers attacks. At the same time, AA armament was limited to a single 4-inch gun placed on the island, between the funnels, a choice that radically reduced its arc. But David Beatty, in advance on the era on this point, believed the carrier’s own fighters could do the job of defending the vessel against other planes. The revised blueprints were approved in June 1918. The design was later altered for protection: The 4.5-inch (114 mm) armour of the upper belt was lowered at waterline level. The barbettes for the former 14-inch guns were completely eliminated.

Launching and delays

HMS Eagle was eventually launched on 8 June 1918 without much fanfare. She was towed downriver, to the shipbuilder yard for fitting-out. This started ten days after, after all preparations has been made. This started by re-routing boiler uptakes. Next the 1.5-inch (38 mm) upper deck was modify to be used as the floor of the hangar deck. A new superstructure was erected above, running all the way but stopping short of the stern and prow. The flight deck which was built above had a 1-in thickness (25 mm). The thickness was more for better stiffness of the ship rather than protection per se. By November 1918, the war ended, and HMS Eagle was still nine months from completion.

As priorities changed, construction immediately slowed down to almost a halt, pending a decision of the admiralty, linked to the Government’s own decision about her fate. Indeed, before requisition she had been paid by the Chilean Government (but refunded afterwards). As the war ended, so was the requisition and the ship should potentially return to her original owner. Construction of HMS Eagle was therefore completed suspended on 21 October 1919, when Chile made known by its ambassador the will of the Government to repurchase the ship.

This was assorted to the will to converted her back to her initial state, as a battleship. Politicians were not well aware of the technical consequences of this choice. Indeed soon, the yards evaluated the cost of such back conversion to £2.5 million, whereas the purchase as estimated to £1.5 million. This was of course too steep, and the Chileans retracted, after securing the return of HMS Canada as Almirante Latorre, still individually superior to the Rivadvia and Minas Gerais.

The ball was back to the Admiralty which decided to retain the ship and resume conversion. Soon, with adequate material and manpower, completion was nearly done and flying trials started. For the first time, the Royal Navy experimented with a ship with a proper island, and the trials results were eagerly awaited to proceed with other designs. Meanwhile the HMS Hermes, also with an island of a similar type, was in completion.

1919-20 Trials

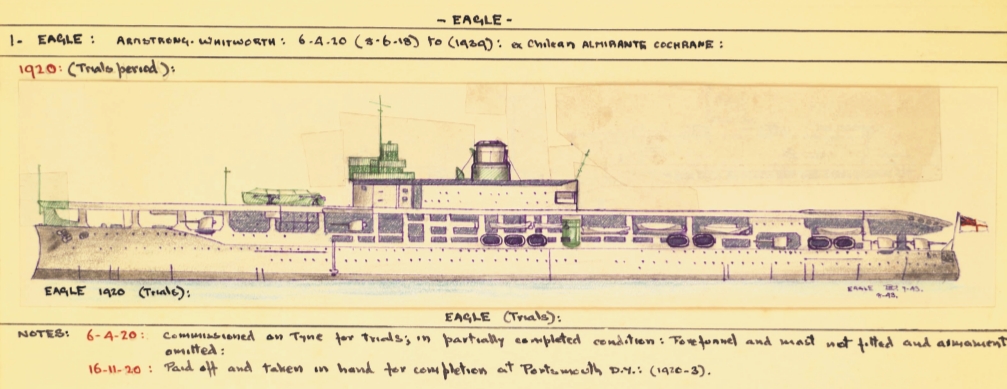

HMS Eagle – original sketches conversion overview

Eventually, on 11 November 1919, after machinery trials were successful, the admiralty approved the ship. Armstrong Whitworth rushed completion to be paid, plating over the openings for the undelivered elevators (cancelled as not in conformity with the specifications), completed the rear funnel, plated over the forward funnel uptakes and removed the torpedo tubes, which could have been an issue for stability. She sailed to the Royal dockyard, Portsmouth for her last modifications and start her first official sea and air trials on 20 April 1920. She performed those sea trials which just two of her boilers, converted oi-burning only.

Afterwards, the first air trials started, under Captain Wilmot Nicholson’s command (former Furious’s captain) and RAF Group Captain Charles Samson. The longitudinal arresting gear already tested in HMS Argus was further tested in a modified form. Bythat time, its purpose was solely to prevent the landing aircraft from veering off to one side, falling off. Indeed planes of that generation were light enough to stop without aid, just by aiming at a good headwind. This arresting gear was about 170 feet (51.8 m) long. The first trials showed it was installed too far forward for comfort. It was therefore moved further back and lengthened. The final version was 320 feet (97.5 m) long.

on 10 May, taxiing trials started, with Sopwith Camel fighters. They were joined by a Parnall Panther reconnaissance aircraft. These tests were realized with the ship anchored. Flights were performed to test winds currents around the ship, from all directions, headings and altitudes. What worried all was the behaviour of planes close to the tall island. The first on-board landing was performed on 1 June 1920.

HMS Eagle in 1920 during her first trials – Src: Hazegray.org

Afterwards, HMS Eagle tested the Bristol F2B fighter, Sopwith Cuckoo (torpedo bomber), and De Havilland DH.9 bomber. Apart the Cuckoo, none was navalized. It was not required at that time.

Tests were mostly successful. They were only 12 minor accidents in 143 landings, including in adverse weather. Reports shown however that the planes own landing gear needed shock absorbers to handle the impact, moreover on a pitching deck and harder angle.

Group Captain Samson for the first time recognise the need to “navalize” aircraft. He preferred the elimination of the island altogether, which was of course opposed by Nicholson and the admiralty, as it was needed to serve the onboard armament and command and control in general. However the captain recoignised the size and shape of the island were not optimal. He recommended a full fuel oil conversion, due to black smoke issues hampering pilot’s vision, and stressed the removal of the 6-inch guns. They were to be traded for extra anti-aircraft guns, and elimination of the tripod mast needed for fire control. In this, he was not followed by the admiralty however. Thus, the HMS Eagle came out as a compromise.

HMS Eagle final design

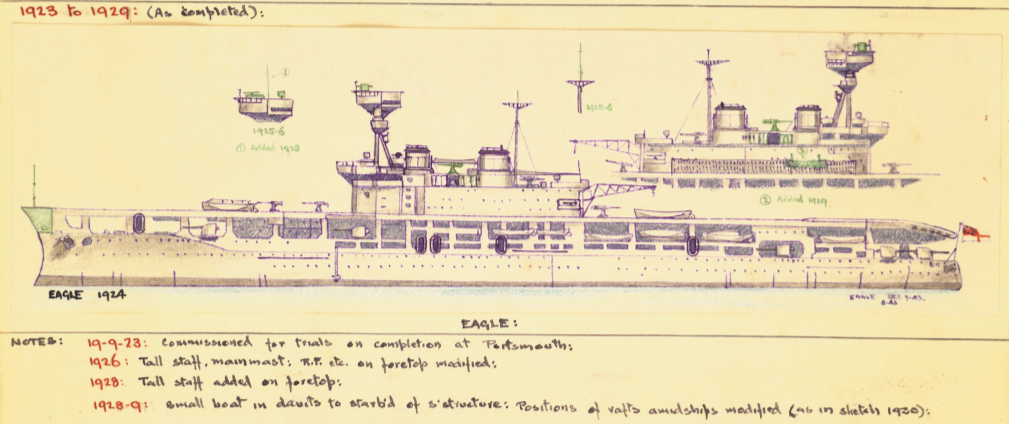

HMS Eagle, modifications 1923-29 – drawing by Perkins. His art book of the RN, recoignition plates, now part of the British Warship Recognition – Volume II: Armoured Ships 1860-1895, Monitors and Aviation Ships. SRC

1921-24 reconstruction

HMS Eagle active service as a test ship ended on 16 November 1920. However she was not taken in hands for modifications, on a completely revised design, before 24 March 1921. This took place at the Portsmouth NyD.

The Admiralty choose to retain some suggestions from Nicholson, but scrap others. The island, first of, was heavily modified. In between, a mockup scale model was tested in a wind tunnel at the National Physical Laboratory.

The admiralty did not flinched over the 6-inch guns, which were retained. The forward edge of the flight deck was faired into bow, as the results of the wind testings. It allowed to smooth out air currents over the bow. Extra 4-inch AA guns were mounted on and around the island as suggested. New elevators were orders, while the forward one was shifted at the forward end of the hangar. To improve ASW protection also, anti-torpedo bulges were added. They ran 6 feet (1.8 m) deep. Petrol storage was modified, from tins to a single 8,100-imperial-gallon (37,000 l) tank. Thus, fuel capacity was increased to 3,000 long tons (3,000 t) and with the bulges added, filled with additional petrol, up to 3,750 long tons (3,810 t), with 500 long tons acting as ballast. This was mandatory to offset the weight of the island on starboard.

HMS Eagle, modifications 1923-29 – same source as above.

As completed in February 1924, HMS Eagle measured 667 feet 6 inches (203.5 m) overall, for 115 feet (35.1 m) in width (waterline) 26 feet 8 inches (8.1 m) of draft deeply loaded. Displacement was lower of course than the original battleship design, but still at 21,850 long tons (22,200 t) standard load.

The flight deck was 652 feet (198.7 m) long, the hangar below 400 feet (121.9 m) long. Its height was around 20 feet 6 inches (6.2 m). The forward elevator was 46 by 47 feet (14.0 m × 14.3 m), and the aft one 46 by 33 feet (14.0 m × 10.1 m). The arresting gear was further lengthened to 328 feet (100.0 m) long. To serve boats and recover planes was planed a large crane, with 60-foot (18.3 m) or traverse, right behind the island as initially planned in 1928.

Powerplant

Each of the ship’s four sets of Brown-Curtis geared steam turbines drove one 3-bladed propeller.[17] They were powered by 32 Yarrow small-tube boilers. During her sea trials on 9–10 September 1923, the turbines produced 52,100 shaft horsepower (38,900 kW) and gave Eagle a speed of 24.37 knots (45.13 km/h; 28.04 mph), but this caused leaks in the turbine joints and she was limited to a maximum of 50,000 shaft horsepower (37,000 kW) in service. She had a range of 4,800 nautical miles (8,900 km; 5,500 mi) at 16 knots (30 km/h; 18 mph).[18]

Protection

Blueprint of HMS Eagle in 1924 as completed

The protection was no longer to battleship standard, but nevertheless, in addition to ASW ballasts, which stored oil and were used to compensate for the island weight offset, the waterline belt was 4.5 in (114 mm) in thickness, and the main protective deck: 1–1.5 in (25–38 mm), the latter figure over the magazines and engine rooms. With a hangar, this means a shell had more levels to cross. Bulkheads were not forgotten and were 4 in (102 mm) thick. Hangar protection included four steel shutter fire curtains to isolate any fires in the hangar.

Armament

Blueprint of HMS Eagle in 1942

The final armament of the Eagle still comprised nine 6-inch (152 mm) guns, completed by five 4-inch (102 mm) Mk V anti-aircraft guns. The former were the standard-issue BL Mk XVII 6-inch gun. Three were posted at the stern, one in the axis and the two others in échelon behind, and the six others went along the broadsides in sponsons. Each was supplied with 200 rounds and was protected by a standard-issue light cruiser gun shield, cast and rounded.

The 4-inch (102 mm) Mk V AA guns were another staple of British light artillery, with a lineage going back from 1914 up to 1945. They were developed to provided a higher rate of fire than the BL 4 inch Mk VII. At first these were used only for anti-shipping role, and inaugurated by the Arethusa class cruisers, but soon a high-angle mount was tested, and fitted, to procure the gun a anti-aircraft role. In that guise, the Mk V had a practical ceiling of 28,750 ft (8,800 m). Muzzle velocity was 2,350 ft/s for the 31 lb (14.1 kg) fixed QF HE round, with promixity fuse in WW2. The gun elevation was 80° but loading was limited to 62°, which slowed down the rate of fire.

Aviation

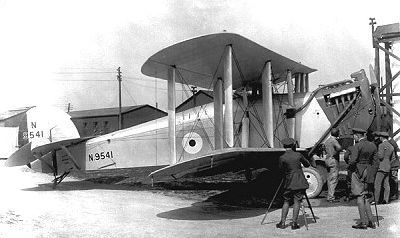

Blackburn Dart, of the 1920s air group, No. 460 Flight.

HMS Eagle aircraft capacity was 25 to 30 planes, depending on their size. In 1939 the crew comprised 41 officers and 750 men, while the air group added 160-200 more personal.

HMS Eagle air group was rather small but comprised a classic trio at first in 1924: Fairey Flycatchers fighters, Blackburn Blackburn (reconnaissance), Supermarine Seagull flying boats (for recce, arty spotting and liaison) and Blackburn Dart torpedo bombers.

From 1925, the Seagull were retired and replaced by land-based Fairey IIIDs from January 1925. Later that year, she carried Avro Bison spotters.

From 1934, the air group would comprise 9 Hawker Osprey fighters and 12 Fairey IIIFs, later replaced by the Blackburn Baffin. In 1937 they were all replaced by a single type air group, nine Fairey Swordfish torpedo bombers and nine more Swordfish of two squadrons. In 1939-40 she carried Gloster Sea Gladiators in crates to be disembarked, but there is no evidence she flew some. She was still equipped only with Swordfish TBs. However in early 1941 she did carried nine Fairey Fulmars, five Sea Gladiators and six Swordfish. In 1942 she would carry for Malta 17 Spitfires and six Fairey Albacore, but retained four Sea Hurricanes, which replaced the obsolete sea gladiators. In addition to those, for her last mission to Malta she carried a total of 31 Spitfires. Later, when she was struck by a submarine, she carried 16 Sea Hurricanes (Sqn 801 & 813) plus four reserve aircraft.

HMS Eagle in action

HMS Eagle operated with the fleet mostly in secondary theatres of operation, where her speed did not matter much. So she never operated with the Grand fleet at Scapa flow, but alternated between the Mediterranean and East Asia stations and was the objects of at least three refits until 1942. Her loss during Operation Pedestal was attributed not to a single, but four submarine torpedoes, proving her ASW protection, designed in 1920 and perhaps still relevant, was unable to cope with such devastation.

The interwar years

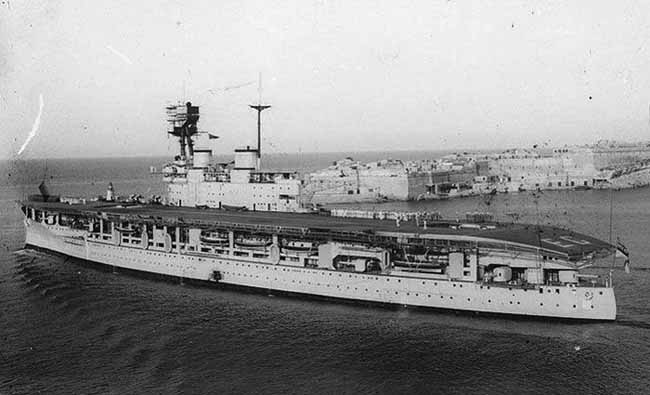

HMS Eagle on the Mediterranean Squadron

HMS Eagle was commissioned on 26 February, and after some crash courses and training, her first assignation was the Mediterranean squadron, on 7 June 1924. As such, by tonnage, she was the largest aircraft carrier in the world, despite the fact her air group only comprised 24 aircraft. They were split into four flights of 6 Fleet Air Arm aircraft. The first to operate on board were the No. 402 (Fairey Flycatchers) No. 422 (Blackburn Blackburn) No. 440 Flight (Supermarine Seagull) and No. 460 (Blackburn Dart).

However she did not operated all four simultaneously. One usually operated from Hal Far in Malta, or Aboukir in Egypt. The Seagulls proved rapidly an hindrance in service. They were replaced by land-carriage Fairey IIIDs from January 1925. HMS returned home at the fall of 1925 in Devonport, for a brief refit. As reported by pilots, the longitudinal arresting gear was removed. Also for AA defence, two single QF 2-pounder AA guns were added close to the 4-inch on the flight, forward of the island. Also petrol tanks were modified, raising the capacity to 14,190 imperial gallons.

Fairey Flycatcher over the Eagle, late 1920s

Eagle was back in the Med by 1926, carrying No. 422 Flight Bison spotter aircraft. In 1928 HMS Courageous joined the squadron. Both experimented common operations. Eagle 1929 refit consisted in the addition of a salt-water spray system in order to deal rapidly with hangar fires. By June 1929, she rescued Major Ramón Franco and his crew (brother Francisco Franco) which Dornier Do J Wal (“Whale”) Numancia was stranded in the North Atlantic due to fuel exhaustion why attempting a global voyage.

Both 440 and 448 Flights of HMS Eagle (Bison) received Fairey IIIF recce aircraft. From 8 January 1931 she departed from Malta to Portsmouth and loaded a provision of the latest FAA aicraft for a marketing operation at the British Industries Exhibition at Buenos Aires. She was back to participate in the summer fleet exercises, and sailed again to Portsmouth, arriving in August 1931 for her first great refit since years, in drydock.

1931-32 Refit

Her boilers were replaced, and to combat fire, four foam generators were installed to spray the deck. Armament wise, the 4-inch gun between the funnels was eliminated. In its place an octuple QF 2-pounder Mark V pom-pom was installed, and a quadruple Vickers .50 mount on the starboard aft side. For aviation, an High Angle Control System director was installed on the tripod, aft of the control room. Accommodations were also improved for the crew. This work was nearly complete on 28 November 1932, but due to labor strikes, went on until April 1933.

1934-35 China Station

After this refit it was decided to send HMS Eagle to the Far East, joining the China Station. From 1934, her air group was frequently deployed against pirates, also spotting and discovering their bases. It was discovered that tropical heat was an issue for the bomb magazines. Also the food storage rooms suffered, and a part of its payload had to be bailed out before adequate ventilation measures were taken.

During a short 1934 refit at Hong Kong, a new quad .50 MG mount was installed forward of the 2-Pdr mount, which was shifted further to port. She operated nine Hawker Osprey fighters (803 Squadron) plus 12 Fairey IIIFs (824 Squadron), so 21 in all. Sqn 803 Squadron was later transferred to HMS Hermes and by Blackburn Baffin torpedo bombers (812 Sqn) arrived when Eagle left the east asia Sqn for the Mediterranean. She arrived in February 1935 and landed her sqn at RAF Hal Far before sailing back to Devonport for her second great refit in service.

HMS Eagle by Phil Heydon – Src maritimequest.com

1936 Refit

In drydock, HMS Eagle was paid off an decommissioned for the work to take place. The refit started in January 1936 and was achieved by mid-1937. First off, thanks to other pilot’s reports, a standard transverse arresting gear was installed. AA-wide, a second octuple 40 mm replaced the older 2-pdr single models installed forward of the island. Two more quad Vickers .50 MGs mounts were also installed in sponsons close to the bow for a greater arc of fire. The bomb magazines was enlarged as modern planes could carry a double payload. At last, the ship’s ventilation and insulation was entirely revised and greatly improved to cope with tropical conditions.

1937-39 China Station

Thanks to this, she sailed again, under her new captain Clement Moody for the Far East in 1937. By that time, 813 Sqn arrived on board, with nine Fairey Swordfish TBs, completed by nine others (824 Squadron) destined for HMS Hermes. Captain A. R. M. Bridge took command of the British aircraft carrier from 16 June 1939. In August her crew landed in Hong Kong, she carried another before sailing to Singapore for a short refit. She was caught was by the war breaking out soon after.

Stern view of HMS Eagle (unknown origin, from Flickr)

1939-40 Indian Ocean Operations

When the war broke out, HMS Eagle was in Singapore, her short refit just completed. Her first wartime mission was to searching for German merchant ships, operating with the light cruiser HMS Birmingham and the destroyer HMS Daring. Her Swordfish planes spotted the freighter SS Franken south of Padang (Sumatra). Birmingham scrambled to intercept her. HMS Eagle stopped at Colombo, Ceylon, on 10 September, and departed for more patrols until 5 October in the Indian Ocean. Her area of operations stretched from the west coast of India to the Maldive Islands. HMS Liverpool replaced the Birmingham. Later, she became the center of Force I, now including the heavy cruisers Cornwall and Dorsetshire. Their mission was to spot and catch the pocket battleship Admiral Graf Spee and German commerce raiders. She then headed for Durban (South Africa) in December for a short refit, to clean up her boilers and scrap her bottom in drydock while the crew enjoyed Christmas and the new year in Durban.

Bow of HMS Eagle (Src Pinterest)

Indian Ocean patrols resumed in early 1940. She was detached to escort a large Australian troop convoy passing by and bound to Suez. As she operated off Nicobar Islands on 14 March, one of her heavy bombs accidentally exploded. This event cost the crew 14 and many more injured while the damage, also confined to the bomb magazines, also cost two generators while one Swordfish stowed in the hangar catch fire and the remainder of the aircraft in the hangar were were doused by salt water and sustained more damage due to corrosion. Eagle halted at Singapore between 15 March and 9 May 1940. She then departed for Colombo and the Mediterranean.

1940 Mediterranean Operations

HMS Eagle arrived on 26 May 1940 and the newt month, she embarked three crated Gloster Sea Gladiators stored in Dekheila. These became her only fighters to cover for the entire Eastern Mediterranean fleet. One of her squadrons, 813, attacked from land bases Tobruk, inflicting serious damage to Italian troops and ships here. He Swordfish and bombers sank the destroyer Zeffior, badly damaged the Euro and sank the freighter SS Manzoni and badly damaged two others. These were crippling blows for the Regia Marina and the Afrika Korps.

Later she took part on 9 July to the Battle of Calabria. 803 Sqn shadowed the Italian fleet, while 813 Sqn attacked the cruisers, but failed to score a hit. On 10 July 1940, her Swordfish attacked Augusta harbour (Sicily) sinking the destroyer Leone Pancaldo. On 13 July, her own fighter Sqn short down three attacking Italian bombers. During the night of 20-21 July, 824 Squadron took off from Sidi Barrani ad attacked again escorting Italian vessels at anchor. They sank destroyers Nembo and Ostro as well as the freighter SS Sereno and on 29 July, her Fighter Sqn shot down another Italian bomber while escorting a convoy to Greece.

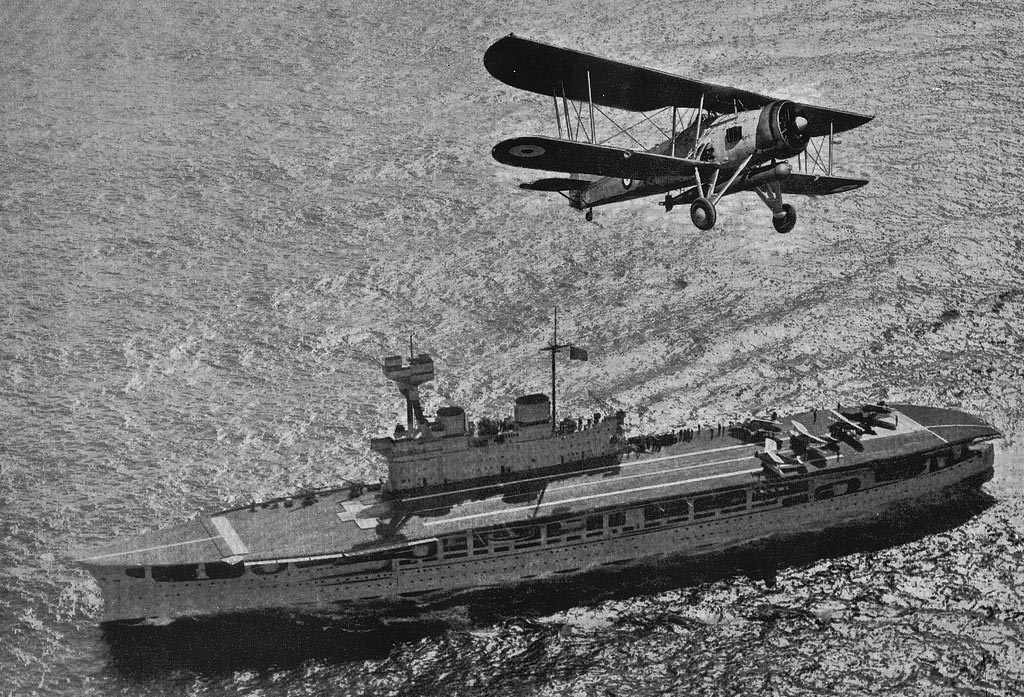

Fairey Swordfish of HMS Eagle. The obsolete plane became one of the most successful carrier-borne attack aircraft of WW2, close to the USN Douglas Dauntless by the total damage it inflicted. HMS Eagle squadrons would claim a dozen of ships.

On 22 August 1940, three planes from 824 Squadron sank the Italian submarine Iride and the depot ship Monte Gargano, in the Gulf of Bomba near Tobruk. What was not known at the time, was these ships carried eight frogmen and four manned torpedoes bound to attack Alexandria harbour. Needless to say, this saved Alexandria (for now). In September 1940 the battle-weary Eagle was reinforced by the carrier HMS Illustrious. They attacked soon after Italian airbases on Rhodes, starting on 9 September. Eagle deployed 12 Swordfish devastated Maritza airfield a bit late after the attack at Collato and four of her planes were were shot down Fiat CR.32 & CR.42 fighters. For these losses, they claimed two SM.79s TBs and four other damaged, disappointing compared to previous attacks. This was a lesson for the staff that coordination and timing were of the utmost importance.

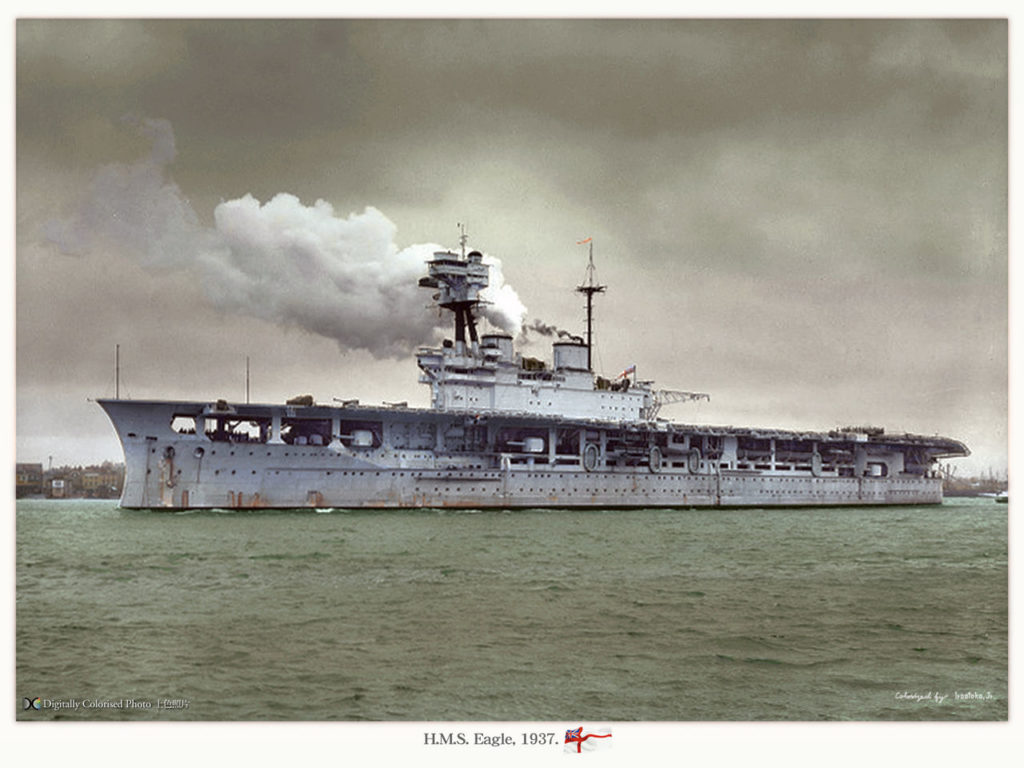

HMS Eagle colorized by Irootoko JR.

Perhaps this was time for retribution. Indeed as she was covering a convoy bound to Malta on 12 October, SM.79s based in Sicily attacked her. They near-missed, but badly damaged the aviation fuel system. Her aircraft attacked the Maltezana seaplane base (Rhodes) on 27 October while four of her Swordfish (824 Sqn) previously disembarked took off from Fuka airfield for a night attack on Tobruk. Basically all 824 Squadron planes attracted the defences by bombing the area, leaving the entrance free to be mined by the 12 other Swordfish deployed. On 28 October, the Mediterranean Fleet departed to the west coast of Greece, hoping to catch the Regia Marina in case they departed but this never happened.

On 5 November, HMS Eagle was in drydock for a short maintenance. Its when the damage previously done to her aviation fuel system was discovered. Leaking could have been disastrous if a fire has broke off. Thise required extensive repairs and meanwhile, one of her Sqn was transferred to HMS Illustrious. They will be put to good use: An attack, the famous attack that took place on 11 November on Taranto, called Operation Judgement. Crucially, that attack cost the Italian fleet its best advanced position in the Mediterranean, in addition to crippling damage to her main battle fleet, and confirmed back in Japan a certain admiral Yamamoto about the chances of success of such operations in a war scenario with the US. This cost Eagle’s quadron one of her Swordfish, shot down by the considerable Italian AA barrage this night.

For the remaining of the month HMS Eagle was Alexandria. Until December, she departed to cover convoys to Greece and Malta and her Sqn bombed Tripoli during the night of 24/25 November. In December 1940 Eagle was back in Alexandria, and the crew enjoyed the leave until the new year. Her aircraft took on many more mission from land bases, notably providing spotting artillery corrections to the battleships Warspite and Barham at Bardia on 2 January 1941.

Gloster Sea Gladiator Mk I named “Faith” (serial number N5520), one of the (alleged) three based in Malta, charged about its defense in September 1940. This fighter has been refitted with a Bristol Mercury XV engine and three-blade Hamilton Standard variable-pitch propeller. In reality the story was embellished by the press, and the Hal Far Fighter Flight group, coming from HMS Glorious, originally comprised 18 Sea Gladiators from 802 Naval Air Squadron. There was a confusion with the three Sea Gladiators on board HMS Eagle which indeed assumed the air cover for the entire eastern Mediterranean fleet. From January 1941, the situation was not brilliant as there were still only five on board for the same tasks, with a menacing and growing Luftwaffe.

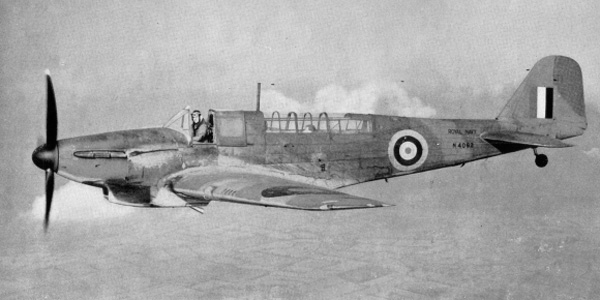

Fairey Fulmar Mark I

1941 Indian, East African & South Atlantic Operations

By mid-January, HMS Eagle departed again, this time covering a convoy to Greece. Bad weather prevented attack on nearby bases. Back to Alexandria, her aircraft group was altered.She received, at the great relief of the staff, additional sea gladiator fighters. Indeed HMS Eagle still provided fighter cover for the entire eastern Mediterranean fleet. Indeed by that time, HMS Illustrious has been badly damaged by German dive bombers on 11 January and was in repairs. One of the Swordfish squadrons was landed to make room for the new fighters. HMS Eagle then departed to cover another convoy to Malta in mid-February. By that time her air group comprised nine Fairey Fulmars (805 Sqn), five Sea Gladiators fighters, and six Swordfish.

HMS Formidable eventually joined the Alexandria squadron, starting by relieving Illustrious on 9 March. At this occasion the staff wanted Eagle to cross the Suez Canal to lead a squadron in the Indian Ocean to hunt down German commerce raiders, but this was cancelled. Meanwhile her two Swordfish squadrons has been transferred to Port Sudan, attacking the port of Massawa, as part of the East African campaign from 25 March. After their mission was a success, they went back to the Eagle on 13 April, as the latter passed the Suez Canal to Mombasa, Kenya, arriving on 26 April. Three days later, she proceeded to patrol the Indian Ocean. On 1 May she was ordered to join Durban (South Africa). There, she met the battleship Nelson and both proceeded to sail to Gibraltar via the west coast of Africa, making a stop at Freetown (Sierra Leone) to refuel. At this occasion her captain was relieved and replaced by E. G. H. Rushbrooke. HMS Eagle received orders and she was detached to search for U-Boat supply ships in the South Atlantic.

The mission started on 29 May, in company of the heavy cruiser HMS Dorsetshire or light cruiser HMS Dunedin. On 6 June, her Swordfish spotted, attacked and sank the Elbe, while the oil tanker Lothringen was also attacked, immobilised, and later captured on 15 June. In September there was an accidental hangar fire, fatally burning an aircraft mechanic while the four Swordfish in the vicinity were damaged by sea water spray.

By October, HMS Eagle sailed back to UK for a well-deserved refit. She arrived at Gladstone Dock in Liverpool and departed for Greenock, arriving on 26 October. She was in the dockyard, decommissioned on 1 November 1941, whereas her crew was given an equally well-deserved leave. The first phase of this refit consisting in improving the AA defense, with the quadruple heavy Vickers machine guns replaced by twelve single satndard 20 mm Oerlikon light AA guns. They were placed in brand new sponsons, six either side of the flight deck. The 4-in AA guns shield were lined with zarebas to avoid splinters.

Control: The HACS fire control was moved forward of the control top, a Type 285 gunnery radar was added as well as a Type 290 air warning radar. Oil fuel capacity was reduced (2,990 tons) to ake room for petrol, up to 3,000 imperial gallons, but this cost her range to fall to 2,780 nautical miles at 17 knots. Of course also the hull was comprehensively cleaned up, as the boilers and tanks, she receive new paint, and comprehensive supplies were bring up to level.

1942 Battle of Malta

On 9 January 1942 she emerged from the dockyard anew, and proceeded to re-commissioning five weeks of training. When done, she was ordered to proceed to meet the convoy WS16 en route to Gibraltar, around 22 February 1942. Se carried for the occasion two newly formed squadrons, 813 and 824. To this all-Swordfish force a complement of four Sea Hurricane 1B fighters (part of 804 Squadron and 813 Squadron). This early type did not have folding wings and stayed on the deck at all times, which was also an advantage to scramble if needed. HMS Eagle arrived at Gibraltar on 23 February, joining Force H.

Hawker Sea Hurricane Mk.1B

824 Squadron was immediately transferred to RAF North Front and in addition, Eagle gathered 15 crated Supermarine Spitfire fighters brought by the HMS Argus. They were partly assembled at the doc and then moved aboard for final assembly, remaining on the flight deck, until completed and were flown off. On 27 February HMS Eagle she was tasked to deliver these to the soon to be besieged strategic Island of Malta.

Her task force was to comprised the battleship Malaya, the carrier Argus and the cruiser Hermione plus nine destroyers, but the whole operation was cancelled. Indeed the Spitfires’ tanks caused troubles and they could not fly. It took until 7 March, to solve this, and they will ultimately made it to Malta. Back to Gibraltar, the worn out engines of HMS Eagle needed intensive care. This lasted until 13 March, and she departed again to deliver nine more Spitfires by 21 March, seven more on 29 March. Back to Gibraltar, the steering gear was now under repairs.

April lasted without notable events, but in May, HMS Eagle was mobilized for Operation Bowery. She was to sail and met during the night of 7/8 May with the American carrier USS Wasp which carried 47 Spitfires bound to Malta. HMS Eagle had no more air group, making room for 17 new Spitfires. The operation was a success and Malta saw sixty new Spitfires delivered.

On 17 May, HMS Eagle was mobilized for another operations, but this time carrying her air group of Swordfish and Sea Hurricanes (813 Squadron), which added to 17 Spitfires and six Fairey Albacore, also destined for Malta. The Operation was a mixed success as the fighters reached Malta but the Albacores had engines problems and were forced back. Just as they landed on HMS Eagle, the radar picked up a flight of around six Italian SM.79 torpedo bombers. They attacked low, avoiding AA fire, and successfully launched their torpedoes, but failed to hit the Eagle. HMS Charybdis however created such as wall of fire that a second attack did not took place.

HMS Eagle escorted by the battleship Malaya during Operation Spotter to Malta, 7 March 1942.

HMS Eagle eventually had all her aircraft, four Sea Hurricanes landed back home to carry 31 Spitfires. On 3 June they were flown off to Malta during Operation Style.

32 more were delivered the same way on 9 June (Operation Salient). She also covered the convoy during Operation Harpoon, taking place at the same time as Operation Vigorous.

She carrid for this 12 Sea Hurricanes (801 Sqn), four Fulmars (807 Sqn) and four Sea Hurricanes (813). Intensive Italo-German air attacks were expected and indeed the Sea Hurricanes during this operations claimed nine aircraft down, two probable, for one loss plus three Fulmars. The mission was a half-success, and Eagle was back to Gibraltar on 17 June. Her next mission to Malta tool plane on 14 July, delivering 32 Spitfires (Operation Pinpoint). Her air group was down to six Sea Hurricane. She would deliver later 29 Spitfires and four Swordfish (824 Sqn) on 21 July, and she fend off a torpedo attack by the Italian submarine Dandolo. This could have been a warning.

Operation Pedestal saw HMS Eagle actively participating with the Victorious and Indomitable, carrying for her own defense 16 Sea Hurricanes (801, 813 Sqn) plus 4 reserve. However on 11 August in the afternoon she has been ambushed by U-73 (commander Helmut Rosenbaum), a Type VIIB. The U-Boat took no chances and fired all four torpedoes from its bow tubes. The ASW compartmentation and ballasts were designed back in 1919 and has not been designed to support the explosive power of four modern torpedoes. As a result, water rushed into the ship’s belly, which filled in four minutes. Thus happened 70 nautical miles south of Cape Salinas. The wreck was found years later. By sinking, Eagle carried with her 131 officers and sailors. Most of the victims were in the ship’s lower level, the machinery area. The destroyers HMS Laforey and Lookout rescued the remaining 67 officers and 862 sailors stranded in the water.

HMS Eagle (1924) |

|

| Dimensions | 203.5 x 35.1 m x 8.1 m (667 x 115 x 26 ft) |

| Displacement | 21,850 long tons standard, ? long tons FL |

| Crew | 791 |

| Propulsion | 4 shafts Parsons geared steam turbines, 24 Yarrow WT boilers |

| Speed | 24 knots (44 km/h; 28 mph) |

| Armor | Belt: 4.5 in (114 mm), Deck: 1–1.5 in (25–38 mm), Bulkheads: 4 in (102 mm) |

| Armament | 9 × 6-in (152 mm), 5 × 4-in (102 mm) Mk V AA |

| Aviation | Variable over time: 30 1924, 25 1942 |

Author’s profile of the Eagle in 1942

Links – Read More

R.Gardiner Conway’s all the world’s fighting ships 1906-1921

Brown, David (1973). HMS Eagle. Warship Profile.

Brook, Peter (1999). Warships for Export: Armstrong Warships 1867–1927.

Colledge, J. J.; Warlow, Ben (2006) [1969]. Ships of the Royal Navy: The Complete Record

Crabb, Brian James (2014). Operation Pedestal. The Story of Convoy WS21S in August 1942.

Friedman, Norman (1988). British Carrier Aviation: The Evolution of the Ships and Their Aircraft.

Gardiner, Robert & Gray, Randal, eds. (1985). Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships: 1906–1921.

Nailer, Roger (1990). “Aircraft to Malta”. In Gardiner, Robert (ed.). Warship 1990.

Rohwer, Jürgen (2005). Chronology of the War at Sea 1939–1945: The Naval History of World War Two (Third Rev ed.).

Smith, Peter C. (1995). Eagle’s War: War Diary of an Aircraft Carrier.

Sturtivant, Ray (1984). The Squadrons of the Fleet Air Arm.

google books – British CVs design, development and service ww2

Gallery on maritimequest.com

Survivor recollections at iwm.org.uk

//ww2db.com/ship_spec.php?ship_id=148

//uboat.net/allies/warships/ship/3255.html

//dreadnoughtproject.org/tfs/index.php/H.M.S._Eagle_(1918)

//againstallodds.fandom.com/wiki/HMS_Eagle_(1918)

//thomo.coldie.net/tag/ww1/

//www.worldnavalships.com/hms_eagle.htm

The models corner: HMS Eagle

HP-Models waterline H.M.S. Eagle 1942

Surface Action HMS EAGLE #9 rare War at Sea miniature

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign

Uh oh, this entry suddenly ends without explaining HMS Eagle’s final fate.

I guess you did not ventured to the end of the article…

Cheers.