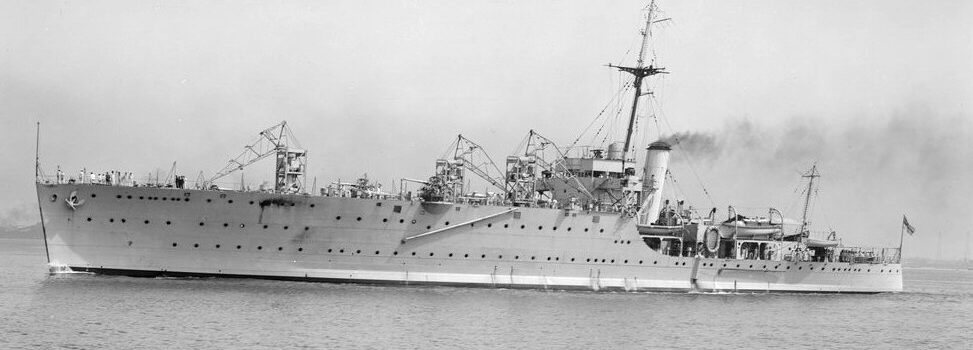

RAN Seaplane Tender from Cockatoo

RAN Seaplane Tender from Cockatoo

Built 1926-29, RAN 1929-38, RN 1938-45

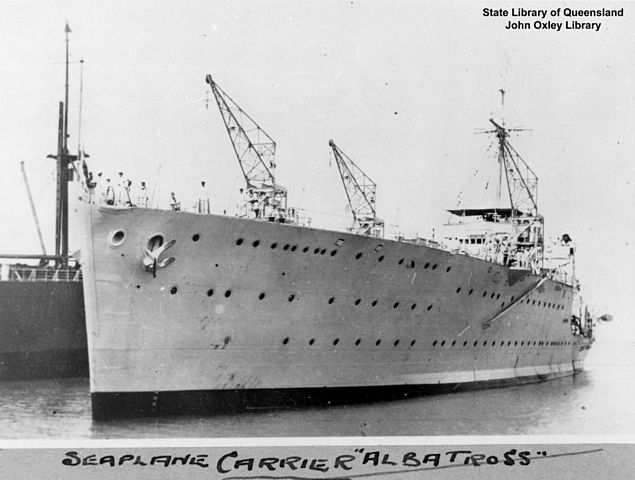

HMAS Albatross was for almost ten years what was the closest to an Australian Aircraft Carrier, and the first naval aviation ship built in Australia for the Royal Australian Navy (RAN). This seaplane tender was later transferred to the Royal Navy in 1938 used as a repair ship in WW2. Albatross was built by Cockatoo Island Dockyard in 1926-29, entered service but experienced problems with the aircraft assigned to her, were retired just she entered service and replacement aircraft not catapult-launched. A new plane was designed specifically was developed just as she was demoted from seagoing status in 1933. She spent five years in reserve and without purpose before being transferred to the Royal Navy in 1938, to offset the Australian purchase of the light cruiser Hobart in the budget-stricken context of the time.

The RN at the time was reluctant to acquire a seaplane carrier, a deal somewhat forced by the government, but found for each a niche after two aircraft carriers were sunk in WW2, based in Freetown, in Sierra Leone for patrol and convoy escort, southern Atlantic, then Indian Ocean in mid-1942. The in 1943-1944 she was converted as “Landing Ship (Engineering)” in support of the Normandy landings, in order to repair landing craft off Sword and Juno Beaches. She was torpedoed in October, survived, repaired in England early in 1945, so she ended as a minesweeper depot ship and decommissioned afterwards. Her life was not over. Not wanted by the RAN, she was sold to the civilian market in August 1946, converted again and became the renamed Hellenic Prince in 1948, a passenger liner chartered by the International Refugee Organisation, carrying migrants from Europe to Australia and troopship during the 1953 Mau Mau uprising, BU 1954.

Development

In 1925, Governor-General Lord Stonehaven of Australia announced to some surprise, that he advocated for the construction of a seaplane carrier, not wanted either by the RAN or RAAF. This was merely a political move in order to provide work to Cockatoo shipyard in the recession of the 1920s and arguing that compared to a conventional aircraft carrier it was easier to finance and man while procuring some similar advantages.

Still, the RAN was not too enthusiastic as the new ship fitted no niche not existing request and did not entered the frame of limited RAN operations at the time, focused on Australian waters and New Guinea. The Australian Commonwealth Naval Board then at least wanted to be in the loop, and from this decision, turned to the British Admiralty to supply a basic design for a seaplane carrier, a type disregarded by Britain since 1918, albeit the RN had been an avid user of such ships in WWI, before turning to aircraft carriers. Both admiralties agreed on some conditions (as the RN suspected one day the RAN would be unable to operate her and perhaps return her to Britain or used it in wartime operations). She was requested to have a top speed of 20 knots (37 km/h; 23 mph), and a cost under 400,000 pounds if built in a British shipyard, a cost to be applied to Cockatoo.

The final design was the very last seaplane carrier designed in Britain. In the interwar, other navies went on with this type, with more or less success: Italy converted a train ferry which became Giuseppe Miraglia, Spain had the Dédalo, a former freighter, and France made the largest of all, the dedicated Commandant Teste in 1931. Being not a conversion but a new built, Albatross looked rather to a previous ships which shared many characteristics, HMS Ark Royal, a seaplane carrier launched in 1914.

Albatross was laid down at Cockatoo Docks and Engineering Co. (Cockatoo Island) near Sydney on 16 April 1926, launched by the wife of the Governor-General of Australia (Baron Stonehaven of Ury) on 23 February 1928 and completed on 21 December 1928, commissioned into the RAN on 23 January 1929 at a cost of 1,200,000 pounds.

Design of the class

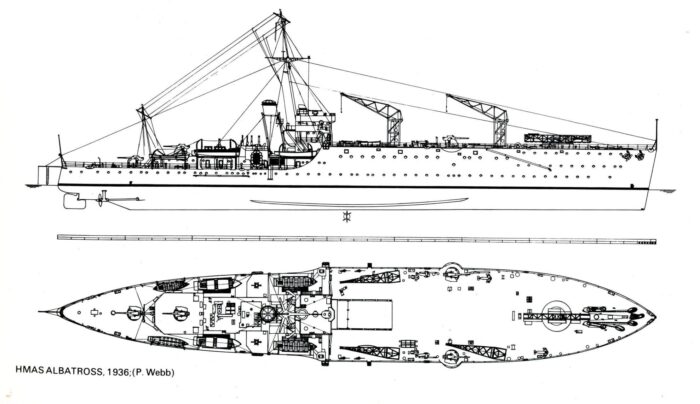

A depiction of HAS Albatross in 1936 by P. Webb.

The basic design was indeed about the same in philosophy, with a roomy hull plus hangar and flat deck forward, and then the superstructure aft. However she still was very different. Ark Royal had a continuous flush deck hull, whereas Albatross had a massive forecastle which extended on three decks, and shorter aft section on which was stacked all the rest, bridge, funnel, masts, structures and main armament. The deck represented more than 6/10 of the length overall, with some flare so as the deck above was much larger than the waterline beam. This flare was more reasonable than on HMS Hermes, but the same basic idea was applied there. Dimensions were far more generous than Ark Royal, and in addition to cranes, she had modern amenities which lacked on Ark Royal, a lift afot of her deck and a catapult forward capable of full traverse.

Hull and general design

HMAS Albatross displaced 4,800 tons at standard load and measured 443 feet 7 inches (135.20 m) long overall, with a beam of 58 feet (18 m) at waterline but 77.75 feet (23.70 m) over the gun sponsons, with an initial max draught of 16 feet 11.5 inches (5.169 m), later raised to 17.25 feet (5.26 m) after additions in 1936.

By the shap of her deck forward she looked like if somewone had taken HMS Hermes and cut the rear to place the aft section of a light cruiser. Her stern was in a pointed inverted style, but her hull was broad in general with a hull ratio of 7,5, which favoured agility over speed.

Her flat deck forward was really free of obstructions except two lain guns on sponsons and a few light guns aft of it, and three main latice cranes to retreive seaplanes at sea. The bridge located aft admidhip started after the hull break, at the foot of the hangar lift. It was four stage high withan open bridge on top and loosely based on the County class bridge. It had a telemeter and destroyer standard tower fire control (see the A/B class), coherent with her main guns.

There was a single mainmast supporting a X type platform to anchor cables and followed immediateley by a single raked funnel. Then followed a quartederck structure with tthe remaining two main guns in the axis, superfirong X-Y positions. She had two counter-keels and three anchors.

Her complement consisted in 29 RAN officers, 375 RAN sailors, 8 RAAF officers, and 38 RAAF personal, pilots/observers and mechanics. She carried two motor launches under davits aft as well as two yawls, a whaler and a cutter aft.

Powerplant

HMAS Albatross’ propulsion machinery comprised four Yarrow boilers, which fed two Parsons geared turbines. This powerplant generated 12,000 shaft horsepower (8,900 kW) and that power was passed to two propeller shafts with three bladed screws at the end of struts. Maximum speed as contracted was 20 knots (37 km/h; 23 mph) initially, and it surprised everybody but the yard when in full-power trials she reached 22 knots (41 km/h; 25 mph), at light load and lake-like waters.

Her range was 4,280 nautical miles (7,930 km; 4,930 mi) at this high speed, which was impressive enough, but in reality it was at max, 7,900 nautical miles (14,600 km; 9,100 mi) at the cruising speed of 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph). Sure, she was not going to follow a fleet, but after all she was designed as an auxiliary to be placed from point A to point B and then used locally as a seaplane base. The powerplant was in fact located in the hull past the break to enable full space for the front section below the hangar. This was essentally a destroyer powerplant fitted in a bulky hull which displaced thrice as much.

Armament

HMAS Albatross was armed basically for self-defence, as a destroyer. She had indeed four QF 4.7-inch Mk VIII naval guns (destroyer standard at the time, but here AA guns) and four QF 2-pounder pom-pom guns as a complement, located aft of her “flight” on both sides. She also had four QF 3-pounder Hotchkiss saluting guns, and four .303-inch Vickers machine guns located on two bandstands abaft the funnel, and twenty .303-inch Lewis machine guns in ten singles and five twin mounts along the ships in multiple points. Needless to say, these were not very effective in WW2 but the combination of AA firepower at various ranges constituted still a good protective bubbles against air attacks.

The problem is that she lacked any protection against air attacks, no deck armour at any level, no armour belt and only ASW compartimentation withy void utility compartments close to the waterline, and bulkheads and separations in the engine room. Aviation fuel tanks buried deep as well as ammunition stores, which were limited since her air group was mostly for recce (see later).

QF 4.7-inch Mk VIII

Her QF 4.7 inch Gun Mark VIII were a rare naval anti-aircraft gun designed in the 1920s, largest caliber fixed ammunition gun ever but with round considerably shorter and lighter than the one from the QF 4.5-inch Mk I–V naval gun. It had a powered HA XII mountin shared by the Nelson-class, Courageous-class carriers, minelayer HMS Adventure, HMAS Albatross.

It had no shield and needed a crew of 8 with a chief, two at elevation and traverse control, a pointer/gunner and loaders. The fixe ammo enabled quick loading but each round weighted an hefty 76 pounds complete. The loading crew was rapidly exhausted to say the least. Compared to the US 5-in/38 they looked antiquated. Only 84 of these were made, and ammo supply was also limited. Read more on navweaps.

⚙ specifications 4.7-inch Mk VIII |

|

| Weight | 6,636 pounds (3,010 kg) |

| Barrel length | 189 inches (4.8 m) L/40 x 4.724 inches (120 mm) |

| Elevation/Traverse | –5° to +90, 360° |

| Loading system | horizontal sliding breech mechanism opening automatically after firing |

| Muzzle velocity | 2,457 feet per second (749 m/s) |

| Range | 16,160 yards (14,780 m) at 45°, max 32,000 feet (9,800 m) at 90° |

| Guidance | Optical, FCS data |

| Crew | 8 |

| Round | Complete 76 pounds (34.5 kg),proj. 50 pounds (22.7 kg) |

| Rate of Fire | 8–12 rounds per minute |

Air Group a Facilities

Development by the Admiralty meant she was originally designed to operate the Fairey IIID seaplane at the time operated for the RAN, No. 101 Flight. Albatross between her deck and hangar could accomodate nine aircraft: 6 active, 3 in reserve—in three separate internal hangars, one on top the the other and all served by the single lift amidship.

This configuration caused the ship’s forward very high freeboard, relegating the propulsion machinery, accommodation and bridge in the aft half. The Faireys however were already absolete and were removed from service shortly she entered service, replaced by the much better Supermarine Seagull Mark III.

However the latter, albeit performing well in geeneral, being derived from race seaplanes made for the Schneider cup, proved unsuited for operations aboard Albatross.

They had not been designed for being catapulted and their structure suffered greatly, so they needed constant repairs and survey between launched. This went so bad that capatuplting was banned and they took off at sea, deposited by the cranes.

Supermarine Seagull Mark III on HMAS Albatross 1928

Specifications for a new aircraft were drawn up to the RAN and RAAF. From them, Supermarine designed the Seagull Mark V (later Walrus) specifically for Albatross. But the design proved so sturdy it was also adopted by the Royal Navy and became its primary observaiton seaplane. Albatross however was just decommissioned in 1933, two months before the future Walrus entered service, and those who arroved were however still operated from her at anchor, at least for testing purposes.

Not designed for her hangars, they proved too tall to be stored inside. The problem was resolved after having the undercarriage retracted on specially designed trolleys but it imposed a slower pace of operation. Overall, this was not super easy nor convenient but at least the Walrus could take off from the catapult as intended. On paper, she could circle seplaned coming from the hangar, with one ready for launch on the catapult, two being prepared on deck behind and one coming from the hangar on its trolley, ready to have its undercarriage in place to roll it in turn.

There are hardly any figure to come out, but it’s likely she could launch a seaplane every five minutes if well managed.

⚙ HMAS Albatross specifications |

|

| Displacement | 4,800 tons (standard) |

| Dimensions | 443 ft 7 in x 58/77.75 ft x 16 ft 11.5 in* (135.2 x 18/23.70 x 5.169 m*) |

| Propulsion | 2 shafts Parsons Turbines, 4 boilers, 12,000 shp (8,900 kW) |

| Speed | 22 knots (41 km/h; 25 mph) |

| Range | 7,900 nmi (14,600 km; 9,100 mi)/10 knots |

| Armament | 4× 4.7-in AA, 2×2 pdr pom-poms, 4× 3-pdr saluting, 24 × .303-in MG |

| Air Group | 9 aircraft (6 active, 3 reserve) |

| Crew | 450, see notes |

*1936: 17.25 ft (5.26 m)

The two Careers of Albatross

HMAS Albatross 1929-1938

HMAS Albatross 1929-1938

HMAS Albatross her her first just a week after commissioning. She visited Tasmania and Victoria as shakedown. On 11 April 1929, she left Sydney for Wyndham in Western Australia to search for Sir Charles Kingsford Smith and the Southern Cross just lost. Smith was found before she arrived. He made an emergency landing near the Glenelg River.

In November 1931, it was discovered her engines had been sabotaged and it happened again by September 1932, attributed with unrest among sailors due to Depression-era pay cuts and retentions.

Meawnhile it was made clear that the Seagull III was ill-fated for her mission due to its catapult ban. Once qualifications were obtained and without clear role, she was to be converted for other uses. From December 1931, Albatross she had a refit to become a gunnery training ship early in 1932. On 19 March 1932 she was present during the ceremonial opening of the Sydney Harbour Bridge.

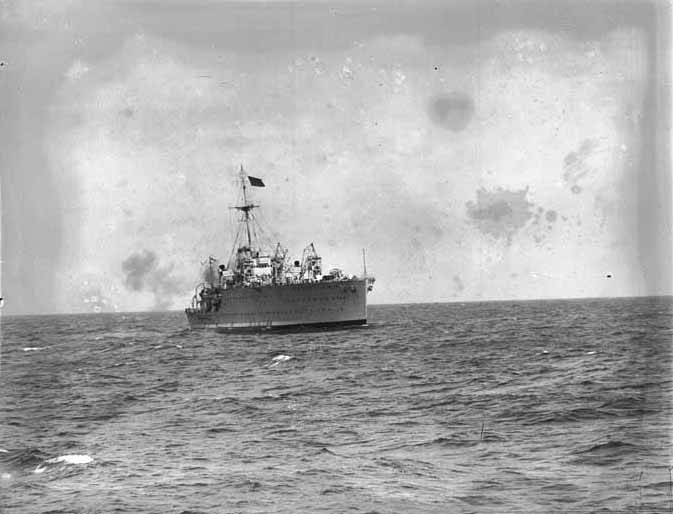

Albatross in 1938

On 26 April 1933, she was decommissioned, as per budget cuts, placed into reserve, anchored in Sydney Harbour. Seaplanes were still operated just to keep the crew’s skills sharp. In 1938, with the Australian government unable to pay for the light cruiser Hobart they just purchased to British yards, it was proposed in compensation to the Admiralty acquiring Albatross as part payment for 266,500 pounds. She thus was recommissioned on 19 April in Austalia as HMS Albatross and prepared for her trip to the UK, departng on 11 July with the company carried by HMAS Hobart on arrival.

HMS Albatross 1938-1945

HMS Albatross 1938-1945

Still, there was no more need for the ship in the RN than in the RAN. With the costs and manpower associated, her very existence was in balance. Not only carriers at the time carried often their own seaplane, but battleships and cruisers all had theor own as well. She was commissioned at Devonport as a trials ship until December and just paid off. Her catapult was removed and she became an Accommodation ship, ideal due to her large hangars, and a skeleton crew, at anchor.

In 1940 the sudden loss of Courageous and Glorious prompted her return to active status. She was assigned to Freetown, western Africa, to be used for convoy escort and perform anti-submarine recce and warfare as well as air-sea rescue in the Atlantic. In May 1942, she was transferred to the Indian Ocean for trade protection and working with the Eastern Fleet based at Kilindini. By September 1942 she provided the air support and reconnaissance for the landings at Mayotte, Madagascar campaign. She went on in her trade protection until July 1943, refitted twice at Durban and Bombay in between. Back home in September she was paid off as there were enough escort carriers in the RN making her redundant.

From October 1943 until early 1944, she had a major conversion as a rather unique Landing Ship – Engineering (LSE). She was to support the Normandy landings, resupplying, maintaining and repairing LSTs. She was initially deployed in the Thames estuary as a deception (part of Operation bofyguard) and on 8 June 1944, crossed the channel and sailed to Gooseberry 5 off Sword Beach, Ouistreham. There she was assigned to her repair role, ideally suited between her cranes and large work spaces and parts storage. Her AA armament was also ideal to provide a point anti-aircraft defence and even bombardment support. She was busy especiall after the “great storm” that disrupted Allied plans and wrecked so many ships and parts of the Mullbery. She saved 79 craft from total loss, returned 132 more to service and July, returned to Portsmouth for R&R. When back to Normandy, she sailed to Juno Beach.

On 11 August, while off Courseulles-sur-Mer she was atpparently targeted by likely a midget sub (seehund and assimilated) and since she lacked the ASW protection of an aicraft carrier, she had major structural damage. 66 died in this explosion. She was withdrawn from service, towed to Portsmouth by the Dutch tug Zwart Zee with repairs lasting until early 1945. She was then anchored as a minesweeper depot ship, until paid off into reserve, on 3 August 1945. Her career could be done by that time, but her unusual hull appealed to others…

Post-war:

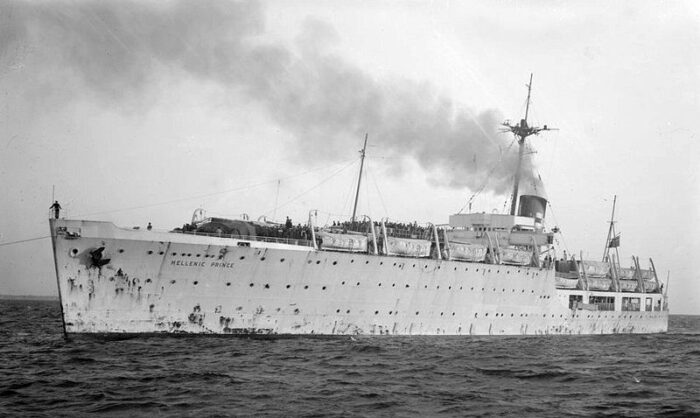

Hellenic Prince photographed between 1949 and 1951

Albatross was to be either sold for BU or to the civilian market, and in fact a British company purchased her from the RN on 19 August 1946, for commercial use. The plan was to convert her into a luxury liner, which soon proved financially prohibitive. So instead she became the “Pride of Torquay”, a floating cabaret, but this plane was never realized as she was repurchased on 14 November 1948 by the British-Greek Yannoulatos Group. After conversion to a liner she became the “Hellenic Prince” (to honor Prince Charles born that day and his Greek heritage).

She was later converted into a passenger liner at Barry in Wales and in 1949, chartered by the International Refugee Organisation, relocating displaced persons from Europe to Australia, which was a fitting return of things. On 5 December 1949, Hellenic Prince entered Sydney Harbour with 1,000 passengers, greeted by those still alive that originally built her or servedon board.

In 1953, Hellenic Prince became a troopship as the Mau Mau uprising went on, carrying British troops to Kenya. However after this last campaign her age showed off. She was sold and scrapped at Hong Kong, on 12 August 1954.

Read More/Src

Books

Australian Naval Aviation Museum (ANAM) (1998). Flying Stations: A Story of Australian Naval Aviation. Allen & Unwin.

Cassells, Vic (2000). The Capital Ships: Their Battles and Their Badges. East Roseville, NSW: Simon & Schuster.

Frame, Tom; Baker, Kevin (2000). Mutiny! Naval Insurrections in Australia and New Zealand. Allen & Unwin.

Hobbs, David (1996). Aircraft Carriers of the Royal and Commonwealth Navies. Greenhill Books.

Molkentin, Michael (2012). Flying the Southern Cross: Aviators Charles Ulm and Charles Kingsford Smith. National Library Australia6.

Rohwer, Jürgen; Hümmelchen, Gerhard (1992). Chronology of the War at Sea 1939–1945. London: Greenhill Books.

“Conversion for Peace No. 3 – HMS Albatross”. Marine News Supplement: Warships. 76 (2): S99–S101 2022.

Links

faaaa.asn.au/ hmas-albatross/

seapower.navy.gov.au/

navypedia.org/

Mason, Geoffrey (2005). “HMS Albatross”. Service Histories of Royal Navy Warships in World War 2. Naval-History.net.

“HMAS Albatross (I)”. HMA Ship Histories. Royal Australian Navy.

en.wikipedia.org/ HMAS_Albatross

more photo Category:HMAS_Albatross

youtube

Videos

Model Kits

Seaplane Tender HMS Albatross 1939 Niko Model No. 7079 1:700

paulooimodelworks.com/ hms-albatross 1942

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign