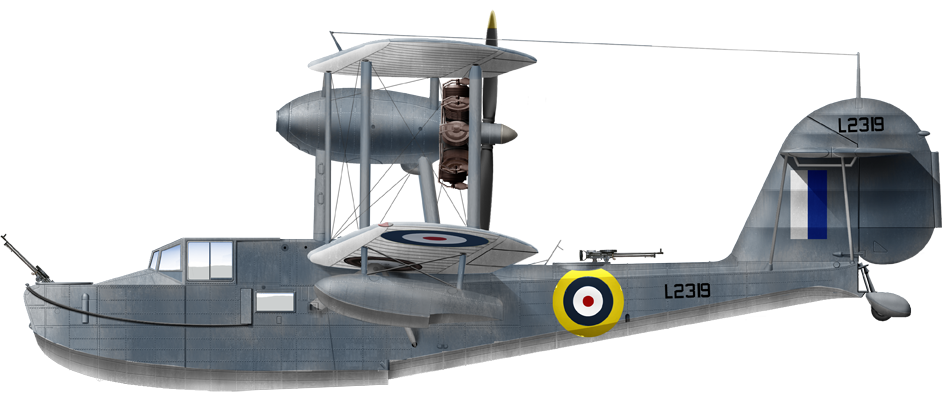

The common British WW2 spotter seaplane

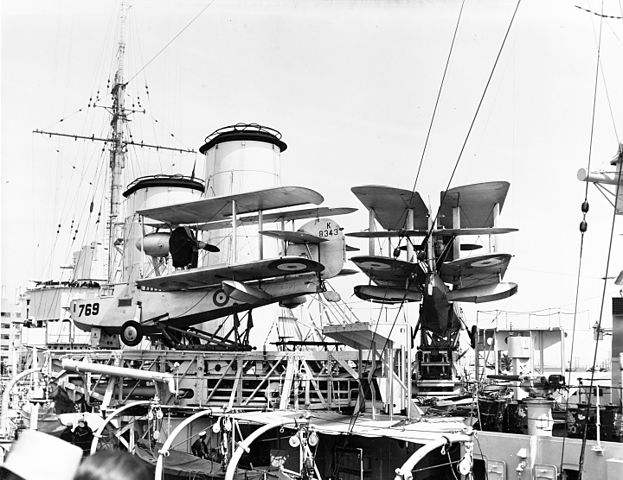

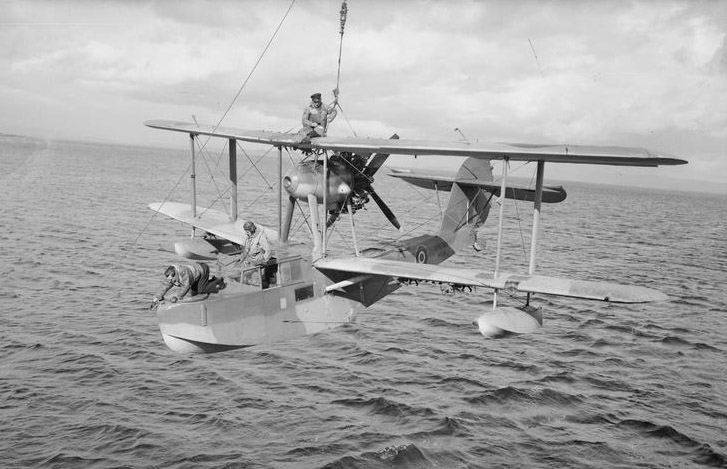

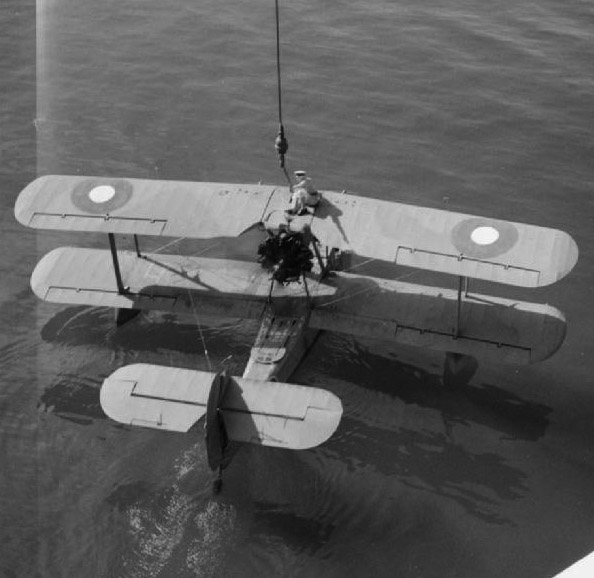

Supermarine Walrus I parked on catapults in HMS Exeter, 1930s

Supermarine, headed by lead designer Reginald Joseph Mitchell which practically died at his desk on 11 June 1937 (aged 42), giving birth to the war-winning Spitfire to his beloved country, also spawn arguably what became the most popular and prolific catapulted seaplane of the Fleet Air Arm in WW2: The Walrus. This unglamorous hero of the Royal Navy, completely obscured by the Merlin-powered fighter over the course of the war, and a production droplet compared to it, nevertheless was found, until 1945, on all major warships of the Royal Navy, from Cruisers, light or small, to battleships, and even aircraft carriers, thanks to its wheeltrain undercarriage;

Although it was a biplane, the Walrus, like the Swordfish was a very dependable model, reliable and perfectly fit for its job, or variety of tasks thereof. Even the advent of the radar or a successor -the 1944 Sea Otter- could not obscure or completely replace it. It not only see action with the Royal Navy, but the RCAN, RAN, RNZN as well, but also the Soviet Union, France, Argentina, Ireland, Turkey and after the war the Netherlands and Norway. A brillant design, that needs not to be forgotten.

About Supermarine and RJ Mitchell

Just as Marcel Lobelle deeply marked Fairey, R.J. Mitchell could hardly be separated from Supermarine. Born in Staffordshire in 1895, he was passionated from a young age with planes, building models, until being an apprentice at a locomotive engineering works an then worked at the drawing office at Kerr Stuart, whilst studying engineering and mathematics at a local technical college, where he perfected his skills; In 1917 he joined the Supermarine Aviation Works at Southampton, a small specialist of flying boats in Southampton. There, he became assistant to the company’s owner and designer, Hubert Scott-Paine and climbed rapidly the stairs being chief designer in 1919, and earning a 10-years contract in 1923 which sealed his role in the company.

Just as Marcel Lobelle deeply marked Fairey, R.J. Mitchell could hardly be separated from Supermarine. Born in Staffordshire in 1895, he was passionated from a young age with planes, building models, until being an apprentice at a locomotive engineering works an then worked at the drawing office at Kerr Stuart, whilst studying engineering and mathematics at a local technical college, where he perfected his skills; In 1917 he joined the Supermarine Aviation Works at Southampton, a small specialist of flying boats in Southampton. There, he became assistant to the company’s owner and designer, Hubert Scott-Paine and climbed rapidly the stairs being chief designer in 1919, and earning a 10-years contract in 1923 which sealed his role in the company.

He started designing flying boats for the Royal Air Force (RAF) and ultimately became the company’s technical director in 1927. His reputation was such that when Vickers took over Supermarine in 1928, a condition was he remained at his post, that he did. Until 1936 and his young death at 42 due to cancer, he designed 24 aircraft, granting the RNAS with four excellent models, the Supermarine Sea Eagle, Sea King, Stranraer, and the model we are concerned here.

But he also propelled the company’s fame into the stratosphere, by repeatedly designing winning models at the Schneider trophy races (1922–1931), bringing worldwide recoignition to the small company and a great deal of experience. Most of this knowledge was then passed onto an initially very innovative and futuristic high performance fighter… rejected by the RAF: A certain “Spitfire”. We will go back to this story with the seafire and seafang in the future.

Before the Walrus: A successful lineage

“supermarine” was intimately linked to the sea. It was founded in 1913 under the combined name of Pemberton-Billing, from former facilities. This company built motor launches and was in yacht trading at White’s Yard, off Elm Road, on the River Itchen. Its first seaplane was a small prototype, the infamous Pemberton-Billing P.B.1… which never flew. The facility was resold to Tom Sopwith which built here his “bat boat”.

Billing enlisted in the Royal Navy during the war, and the company only obtained to built 12 Short S.38 seaplanes under licence in 1915 and others. In 1916 the company was resold to Hubert Scott-Paine and renamed “Supermarine Aviation Works Ltd”. Apart the confidential Supermarine P.B.31E Nighthawk, the company was mostly a sub-contractor.

After the war, Scott-Paine launched a commercial service by hiring ex-RNAS pilots and in 1919 had at last a qualified marine architect. The company then gambled on fame by entering the 1919 Schneider Trophy contest. After a rough start the company won 1922 with the Sea Lion II. The company then started to create for the air ministry a sere of 3-seater fleet spotters and the Seagull became the main seller of the company. In 1924 the company created at last a good serie model, the Southampton, entering service in 1924.

After another round of success in 1925-27, the company was purchased by Vickers and production was stepped-up, notably by having the experience of Barnes Wallis, and the in-house famous Mitchell; Success again in 1929-1931 while the company was restructurated that year with Mitchell as technical director. Soon in 1929, the company answered a RAAF requirement which would lead to design the Walrus, later ordered by the Royal Navy as the revised Type 236, and to answer the specification R.20/31, the Scapa, and for R.24/31, the Stanraer.

Design development: The Supermarine Seagull mark V

Supermarine Seagull III at Richmond RAAF base, 1928.

The Supermarine Seagull was fairly old model, in fact the first company’s best seller with the Royal Navy. It was developed from the experimental Supermarine Seal II and made its first flight in May 1921. In 1922 a single prototype of the single prototype was called Seagull Mk I, but the bulk of the 34 built were Seagull Mk.II (24 for the RNAS), a single sold to Japan for evaluation. A typical seaplane with a boat hull, two underwings floats and single air-cooled engine suspended before the upper wing. It was amphibious, as its landing gear was retractable under wings and alongside the lower fuselage, locked in place to take off and land on hard ground. This feature made its success, as well as its agility and reliability.

The Seagull II was used for gunnery spotting and reconnaissance duties, and succeeded by a single Mark III for evaluation in 1925, tropicalized, of which 6 were purchased by the RAAF with a more powerful Napier Lion V engine. In 1928, a single Seagull Mk II was rebuilt with Handley-Page leading edge slots, twin fins and rudders, assimilated as the Mark IV (no official documentation ever mentioned it). Ultimately, the company tried to improved on this good formula and generated in 1930, a new model with a metal airframe and Bristol Jupiter IX engine, in pusher configuration this time.

It first flew in 1933, and naturally marketed as the Seagull Mark V, but soon the company execitives wanted to make a break with the previous model and renamed it the Walrus, which was the name adopted for this serie, the first great commercial success of the company for the Royal navy. Indeed, at the same time, derived from the company’s racing seaplanes, Mitchell designed the improved Type 300 design to answer a 1934 specs for a fighter… which happened to be the earliest protototype of the future spitfire.

General Design of the Walrus I

First prototype tests and demonstations (1933)

The Seagull V was originally a private venture design to replace the RAAF (Royal Australian Air Force) Seagull III in service since 1926, to be based on its new cruisers. The company worked on the initial prototype in 1930, but since the company was accapared by other projects, it dragged on, understaffed, until 1933. Basically it was the Seagull III but with a metal airframe and new engine in pusher configuration. The first prototype was flown by “Mutt” Summers on 21 June 1933, and showed very good flight characteristics.

Five days later indeed, Summers showcased the surprising aerobatic qualities of the prototype at the SBAC show at Hendon, leaving the spectators amazed to see a seaplane making such impressive manoeuvers, including R. J. Mitchell himseld, showin it could loop the aircraft with no problem, among other. This demonstrated to all the great reigidity of the structure, from the fulelage to the airframe, all stressed for catapult launching. On 29 July, Supermarine conducted the prototype at the Marine Aircraft Experimental Establishment, Felixstowe to be tested by the Navy.

For several months, extensive, punishing trials took place, notably shipborne catapultings aboard Repulse and Valiant, but all on behalf of the Royal Australian Navy, main potential contractor, and soon catapult trials were asked by the Royal Aircraft Establishment at Farnborough. The rigidity and power was such it was possible to mount bombs and armament, making Seagull V, the world’s first catapulted amphibious aircraft launched with full military load. During these tests, the Seagull was piloted by Flight Lieutenant Sydney Richard Ubee.

Further tests were made in 1935 onboard the battleship Nelson at Portland, watched by Admiral Roger Backhouse. The pilot, carried away by his enthusiasm however attempted a water touch-down, but with undercarriage in down position. He hit a wave, flipping over. Nevertheless, the unwanted stunt served even more the growing reputation of Supermarine’s seaplane, as soon the pilot and passengers were recovered with only a few bruises, and the plane was largely intact, quickly repaired for futher tests. It gained a new supporter inside the Navy, Admiral Backhouse.

Soon afterwards, now renamed the “Walrus” the prototype received a new addition to avoid future mishaps, the world’s first undercarriage position indicator on the instrument panel. Test pilot Alex Henshaw whic was also a test pilot went to say the Walrus structure was even strong enough to land on grass wheels-up, without much damage. However he commented that at sea it was “the noisiest, coldest and most uncomfortable” aircraft he had ever flown.

Production

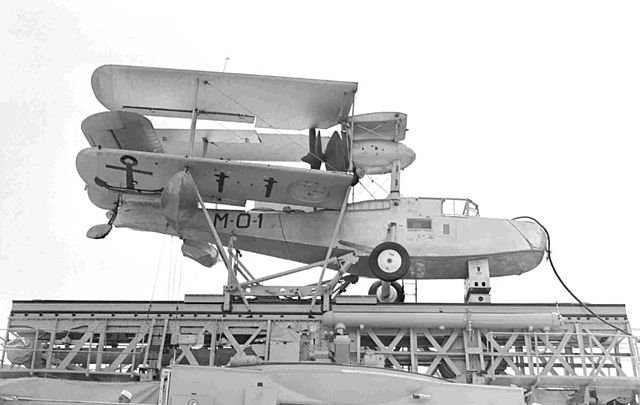

Walrus from HMS MAURITIUS taxiing to be hoisted back aboard

Despite of this, the RAAF ordered 24 Seagull V in 1933, delivered from 1935 under this name. Production aircraft of the Walrus I, soon ordered by the RAF differed from the prototype by having the “Mark IV” Handley-Page slots fitted to the upper wings for extra maniability and to land at very slow speed. The first order of the RAF was for 12 preserie aircraft, placed in May 1935, led by K5772 which flew on 16 March 1936.

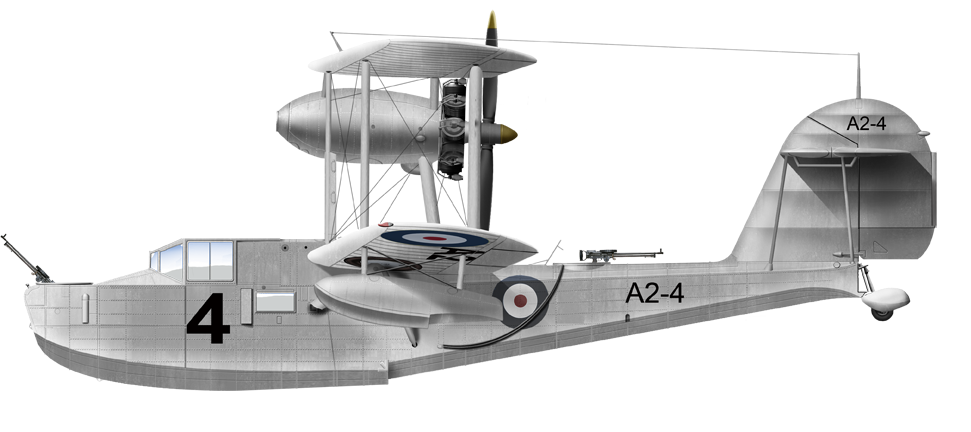

The Walrus I was powered by the Pegasus II M2 engine. From 1937 it was replaced by the 750 hp (560 kW) Pegasus VI and minor details like the transition between the upper decking and sides rounded off, original three struts bracing reduced to two, trailing edges of the lower wing hinged to fold 90° upwards (and not 180° downwards) or the absent external oil cooler on production models.

A grand total of 740 Walrus seaplane were built in all: The “Seagull V” going to the RAAF, the Walrus I beinf produced until 1937, and the Walrus II afterwards, by far the largest chunk of the 740 delivered total. The Mark IIs were not built at Supermarine, but at Saunders-Roe in Addlestone, Surrey. A sub-contractor, Elliotts of Newbury provided the fuselages. This was the 1939-40 production setup (first prototype flying in May 1940) with a wooden hull, sparing strategic materials for military production, a bit heavier.

Saunders-Roe therefore license-built 270 metal Mark Is and 191 wooden-hulled Mark IIs. Supermarine marketed its replacement, the Sea Otter, more powerful but eventually both were used for air-sea rescue in 1943-45. The Supermarine Seagull, same name but brand new postwar model, was cancelled in 1952, seeing only a few prototypes tested as air-sea rescue helicopters took over this role.

Design specifics

Supermarine Walrus K8341 onboard HMS York with folded wings

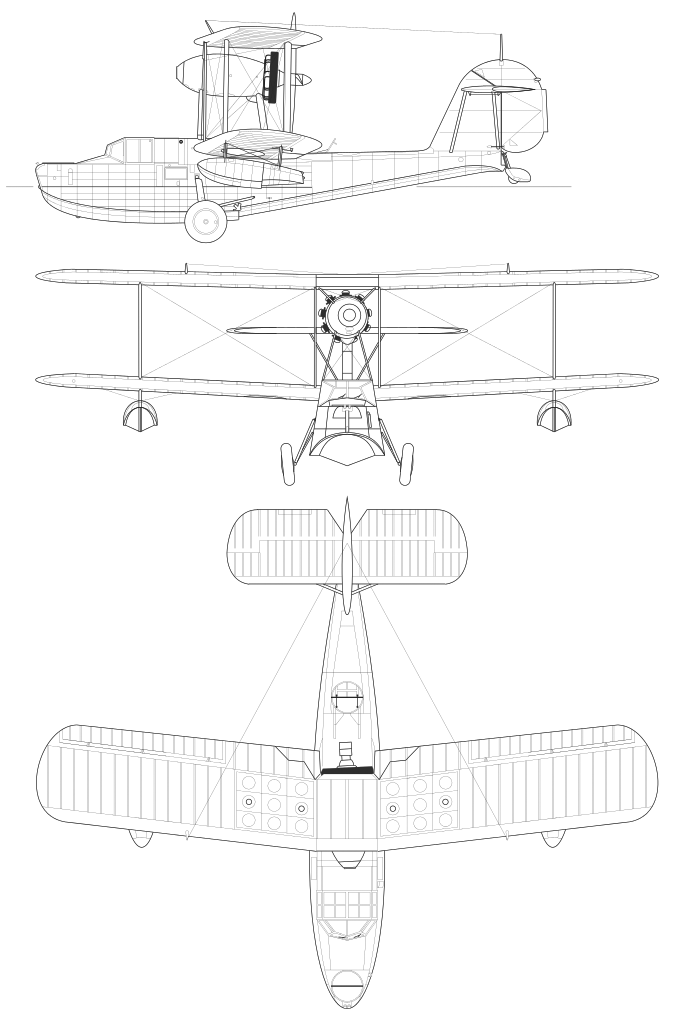

The Supermarine Walrus was a single-engine, single bay boat-like fuselage, amphibious, and biplane for maritime observation. It had a single-step hull made initially from aluminium alloy, but stressed and reinforced by stainless-steel forgings for the catapult spools and mountings, which greatly contributed to its overall rigidity.

Metal construction indeed were proferred over wooden structures, which deteriorated fast under tropical conditions, as required by the County-class cruisers and others around the worls and in particular in Asia. The wings were covered with fabric, and slightly swept back. The internal structure was all-metal, but also in stainless–steel for spars, but wooden ribs. The lower wings were placed in “shoulder position”. They had stabilising floats mounted under, about 70% of their lenght.

General conception

Walrus in HMS King Georges-V hangar.

The tail elevators were high on the tail-fin, braced by ‘N’ struts. One of the great advantage of the design, other than its exceptionaly ruggedness and amphibian caapabilities, were its folded wings. This allowed them a stowage space of just 17 ft 6 in (5.33 m).

The Walrus had a solid aluminium tailwheel, enclosed by a small water-rudder, which could be coupled to the main rudder for taxiing. There was one pilot aboard, but two seats in tandem, with a left-hand position with fixed seat and instrument panel in front. The right-hand seat was folded away to access the nose mounted MG via a crawl-way. The control column was not fixed but could be inserted in one or the other sockets in the floor, therefore adapted to the pilot’s stature or to alternated between pilots. Only one column was used most of the time, even when the control was passed to the co-pilot, just unplugged and handed over. This was quite unique in cockpit design at the time.

Behind the cockpit, the small boat fuselage had a small cabin with seats and work station of the navigator and radio operator. A narrow, relatively dark and noisy place. It was rare however the Walrus was “full” with its four crewmen. During the war, it often happened a single pilot took off, without navigator or radio operator, simply reporting himself his spottings for short range missions in clear weather. The extra crew were mostly necessary for long range operations in open sea.

Engine

Catapult Training For FAA Pilots, HMS Pegasus, Lamlash, Scotland September 1942

The single 620 hp (460 kW) Pegasus II M2 radial, air-cooled engine was housed at the rear of a nacelle, mounted under the upper wings on four struts, braced by four struts to fuselage. To gain maximum traction, the engine was fitted unusually with a four-bladed wooden pusher propeller.

The nacelle contained the oil tank around the air intake, also acting as an oil cooler, plus the electrical equipment with several access panels for maintenance. A second oil cooler was mounted on the starboard side and fuel was carried in two tanks, located in the upper wings.

The choice of a pusher configuration, rarely seen since WWI, had the main advantage for a naval plane, to keep the engine and propeller away frim water spray in operations. It also reducing the noise level for the crew, making it more bearable. The propeller’s location also was safely away any crew standing on the front deck when picking up a mooring line to be hoisted aboard. The engine mounting was particular as being was offset by three degrees to starboard, to counter a known tendency to yaw, due to unequal forces on the rudder, disturbed by the vortex from the propeller.

Armament

Walrus piloted by Lt AS Lawrence lands on deck of an unidentified aicraft carrier, Indian Ocean, 1944 with underwings racks for depth charges.

Typical armament configurations for the Walrus consisted of a pair of .303 in (7.7 mm) Vickers K machine guns, one each in the open positions in the nose and rear fuselage. In addition, there were provisions for carrying either bombs or depth charges mounted beneath the lower wings, limited to 500 lb (230 kg) or two underwing 250 Ibs (115 kgs) bombs.

Equipment

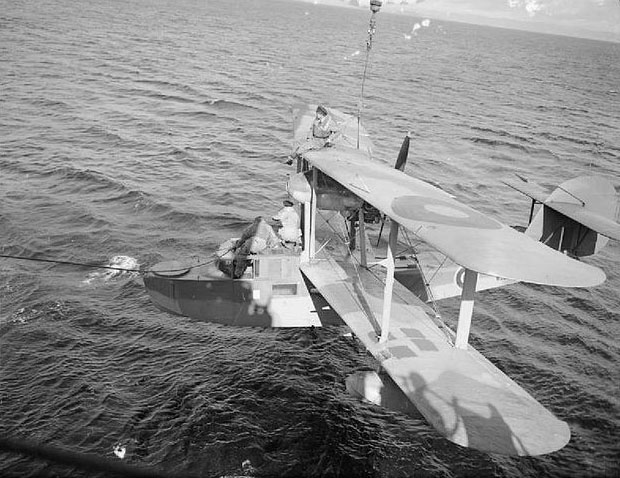

The Walrus carried marine equipment, an anchor, towing and mooring cables but also drogues and a boat-hook, as she behaved like a boat at sea (but with a massive air drag!). After being catapulted, the Walrus was recovered by touching-down alongside the carrier ship in calm weather of possible, then lifted from the sea by the ship’s crane. Its lifting-gear was located in a compartment of the wing, directly above the engine.

Specifications Walrus Mark I |

|

| Crew: | 3: Pilot, Gunner, Observer |

| Dimensions: | 33 ft 8 in x 45 ft 9 in x 12 ft 9 in (10.26 m x 13.94 m x 3.89 m) |

| Wing area: | 443.5 sq ft (41.20 m2) |

| Weight: Light | 6,000 lb (2,722 kg) |

| Propulsion: | Armstrong Siddeley Panther IIA 14-cyl. air-cooled radial 525 hp (391 kW) |

| Performances: | Top speed: 138 mph (222 km/h, 120 kn)

Service ceiling: 17,000 ft (5,200 m) Rate of climb: 5,000 ft (1,524 m) in 5 minutes 20 seconds |

| Endurance: | 4 hours 30 minutes |

| Armament – MGs | 1x .303 cal (7.7 mm), One Lewis MG aft |

| Armament – Bombs | 500 lb (230 kg) |

Royal Navy service

Pilot, observer and air gunner reporting to their Commanding Officer from HMS ARGUS before mission

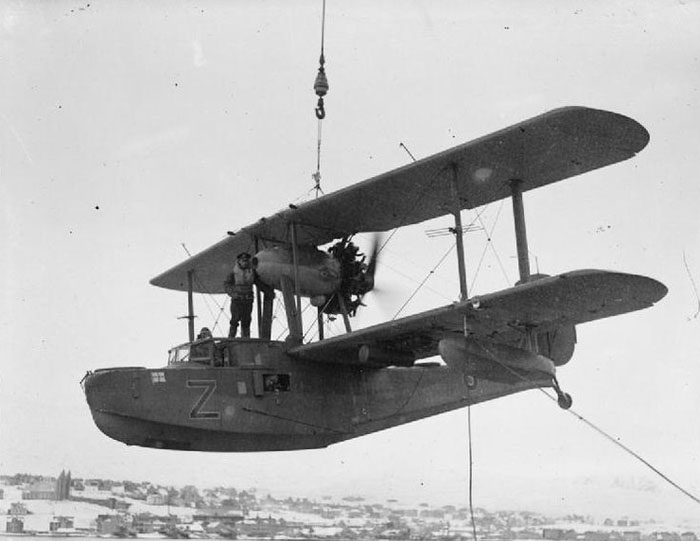

The Walrus was popularly known as the “Shagbat” or sometimes “Steam-pigeon”, from the steam produced by water striking the hot Pegasus engine. The catapulting was straighforward, but the recovery was managed by a brave crewmember that climbed onto the top wing to attach the cable to the crane hook, when close enough to the carrier ship. In rough conditions, the usual procedure necessitated the ship to angle 20° before the aircraft touched down, creating a ‘slick’ of calm water on which the Walrus could land on, fast taxing up to its flank to be hoisted aboard.

All Town-class cruisers from 1937 were provided two Walruses each, launched transversally and stored in individual hangar abaft the forefunnel. HMS York, Exteter, the old E-class, were also, as well as most County-class heavy cruisers provided at least one Walrus. Also battleships, such as HMS Queen Elisabeth, Warspite, Valiant of the QE class, had it, some of the Revenge class, the Battleship HMS Reniown as rebuilt (wich carried two), HMS Rodney and Nelson, as well as the monitor HMS Terror. The “Colony” class (Perth class) carried the Walrus, at least before replacement in 1944 by its designated successor, the Sea Otter. Probably the best known use of the Walrus was the King Georges V class Battleships: All five carried no less than four Supermarine Walrus Mark.II. The planned Lion class, cancelled, would however be given likely the Sea Otter. HMS Vanguard was the last British Battleship, and carried none, due to progress in radar development.

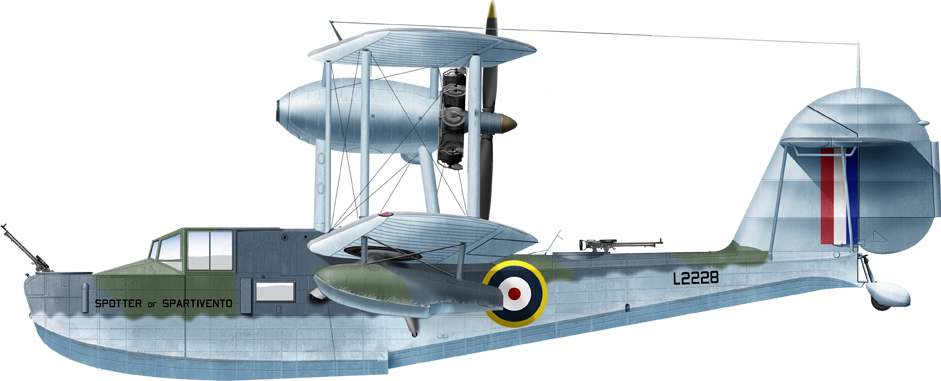

The principal intended use of the Walrus was gunnery spotting, reporting the falling plumes back to the ship’s direction center for immediate corrections. This role was highlighted twice, with HMS Renown and Manchester at the Cape Spartivento, or from HMS Gloucester at the Battle of Cape Matapan. The clear skies of the Mediterranean really proved ideal for such use.

This was another story in the Atlantic, and especially in the punishing conditions of the arctic (Murmansk road), where bad weather provented all but basic air patrols, in search of U-Boats. Indeed, from 1941 onwards, a growing number of Walrus took part in patrols, looking for Axis submarines (German and Italian), blockade-runners and surface-raiders. From March 1941, a few were equipped for the first time wth the new Air to Surface Vessel (ASV) radar, picking spots in bad weather or in the dark. In fact, first tests were made by late 1939, at Lee-on-Solent. Two Walruses were fitted with dipole aerials, fitted on their forward interplane struts. In 1940, another was fitted with a Oerlikon 20 mm cannon to fight against German E-boats, but tests showed the muzzle flash blinded the pilot, with dropping accuracy, and the plan was not adopted.

Walrus of “C” Flight, No 624 RAF mine reconnaissance flight, from Leghorn, Italy 1945.

The Norwegian and East African Campaign both also saw a limited use of the seaplane for bombing and strafing shore targets. In August 1940, one from HMS Hobart indeed devastated the Italian headquarters at Zeila, in British Somaliland. From 1943, improved radar started to make the Walrus redundant and since hangar and catapult occupied much space, plus ammo and gasoline came as a fire hazard, they were removed altogether. Walruses however continued to fly, thanks to their amphibian nature, with undercarriage, from Royal Navy carriers in the “Battle of the Atlantic”. They noyably performed always useful air-sea rescue, or played a role in communications. Despite haing no flaps or tailhook for proper carrier operations, they were ideal due to their slow landing speed and could operate both from fleet and escort carriers.

Air-sea rescue missions were performed to save pilots or sailors from the Royal Navy and Royal Air Force personel. RAF Air Sea Rescue Service squadrons created used indeed both Spitfires and Boulton Paul Defiants to look for large areas quickly, the Walrus to search more limited perimeters, and Avro Ansons to drop supplies and dinghies. But Walruses also were used to pick up downed pilots as well, despite its limited size. RAF air-sea rescue squadrons operated the Mediterranean Sea and up to the Bay of Bengal, saving over a thousand aircrew.

Commonwealth service

Walrus Aircraft on quick launch coastal Slipway, Art (IWM)

The fist “Walrus” in service was in reality the Australian Seagull V, numbered A2-1. It was handed over to the RAAF in 1935, followed by the rest f the batch, until A2-24, in 1937. They were operated from he cruisers HMAS Australia, Canberra, Sydney, Perth and Hobart during WW2. Also among early Walrus of the RAF in 1936 a single one was givent to the New Zealand Division of the Royal Navy, based on HMZNS Achilles. The Australian seaplane tender HMAS Albatross also carried Walruses.

Foreign service

Argentinian Walrus onboard the cruiser La Argentina

After the war, the RAF went on using them, for a few years afterwards, although most ended on the sales list and thus were purchased and impressed into foreign navies, with eight going to the Argentinan Navy, two based on the cruiser ARA La Argentina, operating them as late as 1958, and some were used for training in the Aeronavale (French Navy’s Aviation).

Supermarine Walrus I X9556 S today, waiting full restoration

Surviving ones found commercial use. United Whalers operating some in the Antarctic, from the factory ship Balaena. They were fitted with electrical sockets for the crew’s heated suits; worn under their immersion ones and a petrol cabin heater for long flights, up to five hours. Four aircraft in the RAAF operated them in and off Rabaul, modified and licenced to carry up to ten passengers, and acting also as ambulances until 1954.

Links and resources

Supermarine Seagull

On weaponsandwarfare.com

wik

The model corner

Walrus-SAR-modelkit-1983-Ragnhild-Neil_Crawford

-Trumpeter, Ark Models, Tamiya, Smer, Airfix, SMK

–Full list on scalemates

Gallery

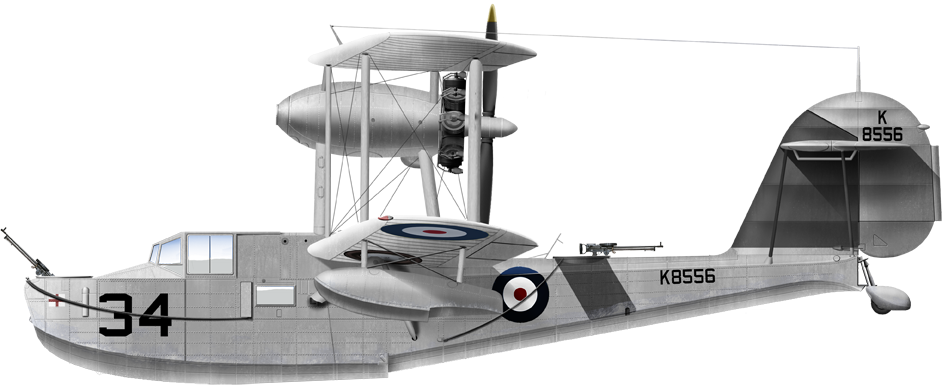

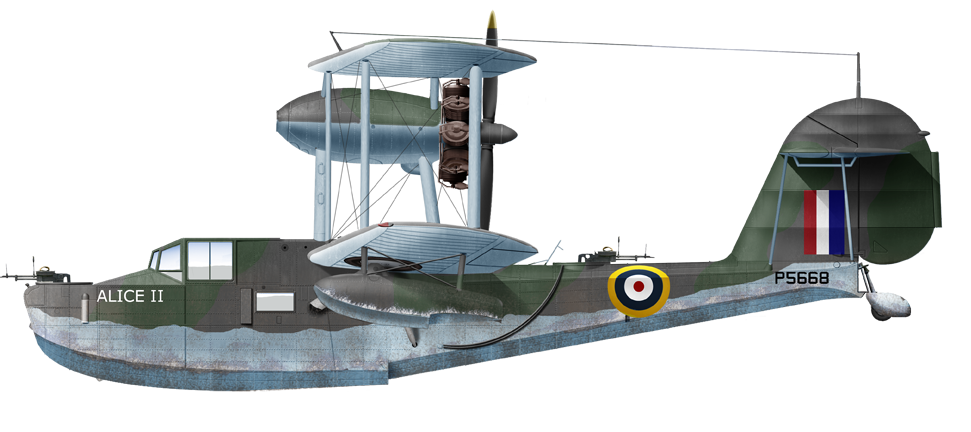

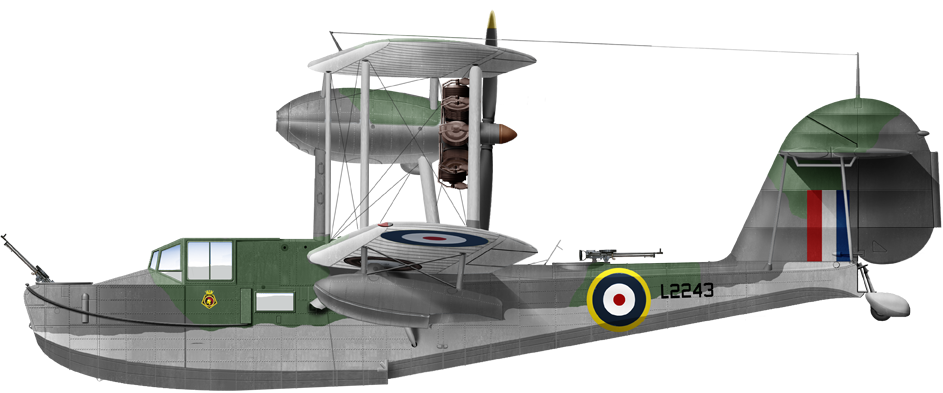

Author’s illustrations: Types and liveries

RAAF Seagull V

Walrus Mark I, 715 wing, heavy cruiser HMS Cumberland, 1937

Walrus I, 720 Flight, HMAS Leander, 1937

Mk.I, 712 Sqn. NAS HLS Southampton 1938

Mk.I HMS Gloucester, Battle of Cape Matapan, March 1941

Mark.I “Spotter of Spartivento”, 700 Sqn. NAS, HMS Sheffield, 1941

Walrus Mark II, Suda Bay, HMS Ajax 1941

Walrus Mark I deployed during Operation Torch, with USN Markings

Mk.II in blue livery, Atlantic, 1942

Mk.II 8th Communicaton Unit RAAF New Guinea August 1944

Mk.II 9th fleet Cooperation unit of the RAAF, New Britain 1944

Walrus II, HMS Victorious July 1945

Additional photos

Seagulls V 5th Squadron RAAF, Richmond 1938 AWM

Seagull V, 9th Sqn HMAS Hobarth

An elephant pulling a Supermarine Walrus Fleet Air Arm station India June 1944

Catapult Training HMS Pegasus Catapult Training Ship FAA, Lamlash Scotland, September 1942

HMS Pegasus walrus recovery

Supermarine Walrus towed into position for hoisting

Crashed Walrus from HMAS Sydney Egypt 1940

Supermarine Walrus towed into position for hoisting

Walrus on HMS Rodney

North African front, Walrus Keeps watch over an hospital ship with Force H, 12-14 January 1943, Mers-el-Kebir.

RNZAF Walrus in auckland, 1944

Walrus onboard HMS Rodney

Walrus X9498 “B plane”, No 284 Sqn RAF in maintenance, Cassibile, Sicily

Walrus Mark I X9506 “C-Flight”, No 293 Sqn RAF, Nettuno, Italy

Walrus of the RAF in Sicily

Supermarine_Walrus_at_Warmwell_No 276or277Sqn-RAF

Walrus-KING-GEORGE-V-Northern_waters

Walrus-taxiing-HMS-WARSPITE-after-sweep-Indian-Ocean

Walrus-hoisted-Lamlash-Scotland

HMS-UNICORN-Trincomalee-Walrus

Walrus-taking-off-hms-argus

Walrus-based-Arbroath

Walrus-takesoff-HMS-KHEDIVE-Far-East1945

walrus-bombardment-Genoa-Spartivento-launched-from-HMS-SHEFFIELD

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign

Please could you let me know the colour scheme of the Walrus on HMSSuffolk during 1941-1943.

Thankyou.

My father worked on the engines during the war & was on Suffolk during this time.

Hi Tim !

All right i’ll try to find it.

David

I’m building a 1/48 scale Supermarine Walrus mark 2. Inquiring about the interior of the aircraft’s fuselage.

Hi David, sorry, no archives for this part of the bird so far. I’m sure there are good books around with these though. Good luck with it.

David