USA – Armoured Cruiser 1888-1898

USA – Armoured Cruiser 1888-1898WW1 US Battleships:

USS Maine | USS Texas | Indiana class | USS Iowa | Kearsage class | Illinois class | Maine class | Virginia class | Connecticut class | Mississippi class | South Carolina class | Delaware class | Florida class | Arkansas class | New York class | Nevada class | Pennsylvania class | New Mexico class | Tennessee class | Colorado class | South Dakota class | Lexington classUSS Maine was the first USN armoured cruiser made famous by the war she indirectly caused to break out in 1898 while expdoding in Havana Harbor on February 15. A well-organized and focused U.S. press campaign, through “yellow journalism” contributed to a situation that was already degraded bewteen the Spanish Empire and USA through Cuba. Just as the Lusitania in 1915 constributed to the US entering WWI, “Remember the Maine!” became a rallying cry in the opinion. This was the catalyst accelerating almost pre-planned events in what was called later a “splendid little war”. It was proven long after the fact by Historians the explosion was likely caused by gunpowder decomposition, sadly a way too common occurence at the time. But beyond the events it trigerred, how fared the main as a warship ? #spanamwar #cuba #rememberthemaine #teddyroosevelt #ussmaine #maine #usnavy #USN

Development

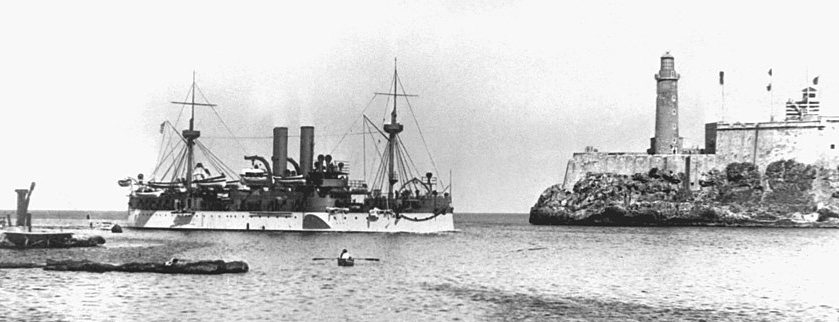

From navsource via pinterest

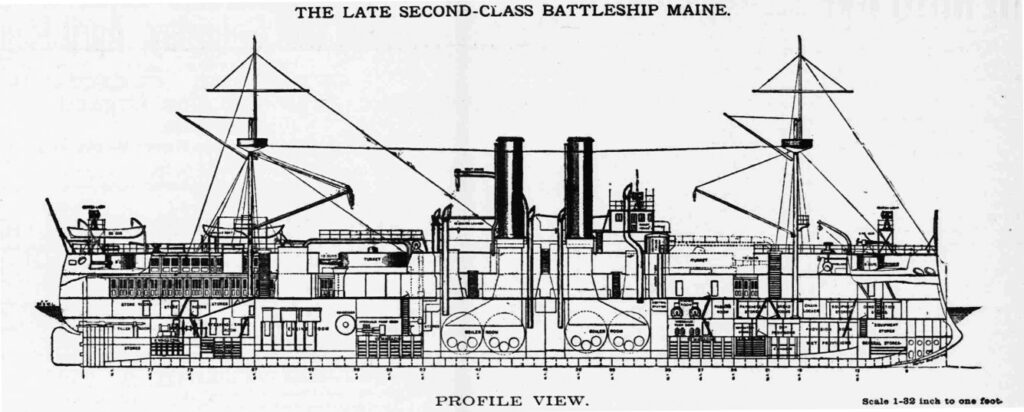

USS Maine, first of the name, a northeast coast state later famous for its Portsmouth, Kittery naval shipyard, was laid down as a “second-class battleship” in 1886, launched in 1889 and commissioned in 1895. A very long time which resulted, like USS Texas, to her obsolescence, despite representing a radical advance in American warship design, looking at European naval developments. Like Texas, she sported the configuration popular in 1885 with two twin-gun turrets staggered en échelon, but not full sailing masts, albeit the barque plan was respected. The 9-year construction period was a testiment to the learning curve. It led ultimately to new generations of battleships starting with the Indiana class (launched 1891), the first true US pre-dreadnoughts.

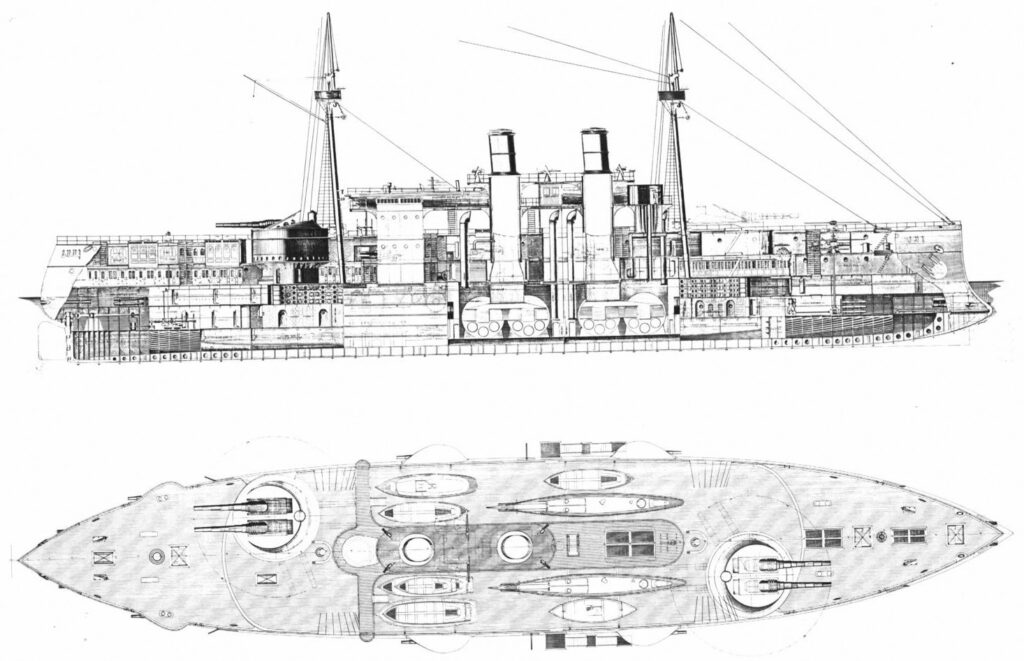

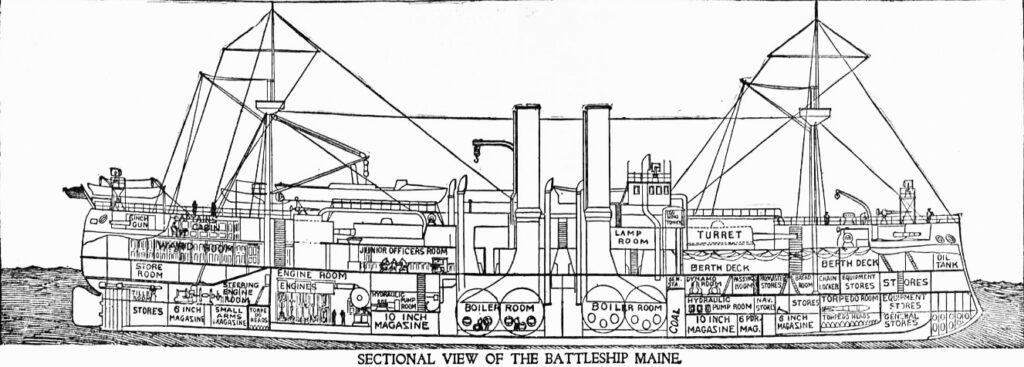

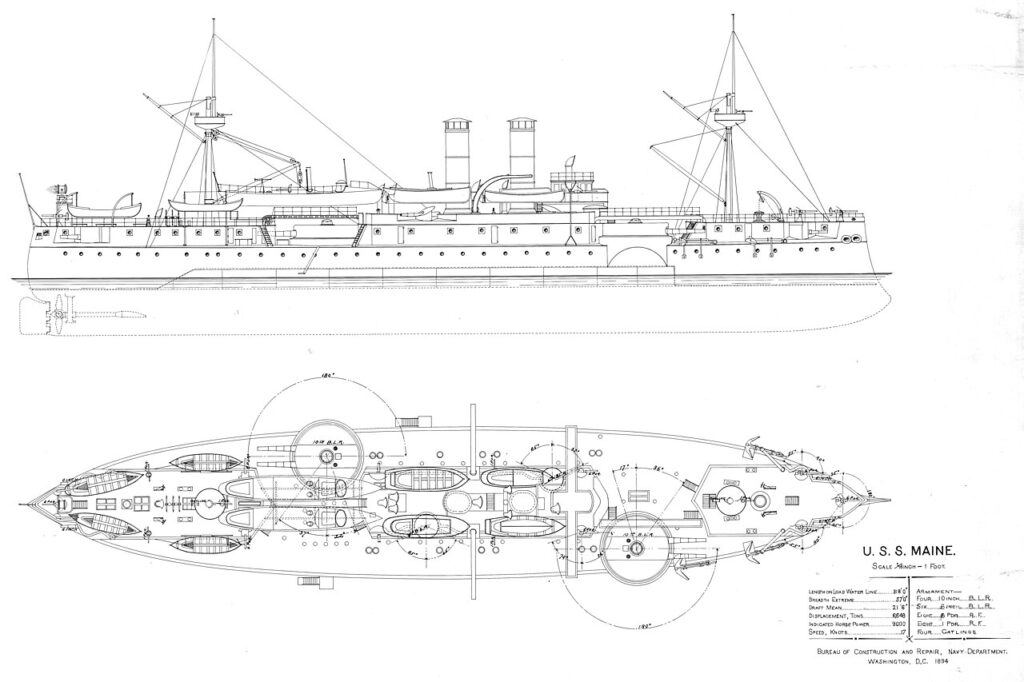

Plans and cutout – From navsource.org

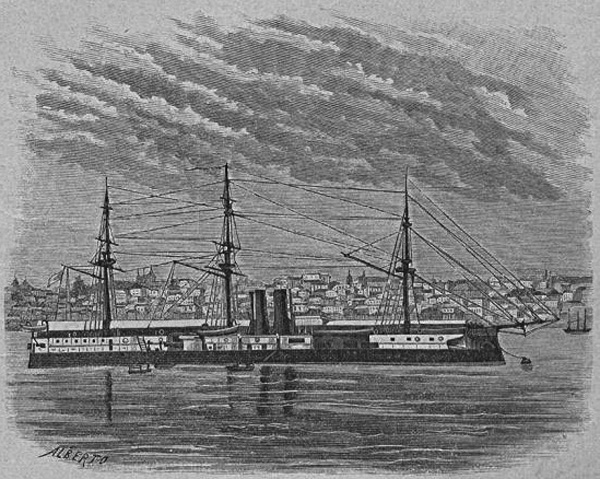

The congress voted the Maine in response, like for USS Texas, to the delivery of the Riachuelo, British built, to the Brazilian Navy in 1883 as well as acquisition of other modern armored warships not only by Brazil, but also Argentina and Chile. The balance of naval power at the time clearly shifted southwards. Until the, the USN was just coming out of decades of near-neglect, an era called the “Old navy” which emerged from the American civil war.

Riachuelo as completed.

At the time, the head of the House Naval Affairs Committee Hilary A. Herbert declared the following to Congress:

If all this old navy of ours were drawn up in battle array in mid-ocean and confronted by Riachuelo it is doubtful whether a single vessel bearing the American flag would get into port.

Discussions already started at the Naval Advisory Board in 1881 and were just fuelled further. Until then it was understood that the U.S. Navy was in no position to challenge any major European fleet, albeit it could still harm merchant trade through attrition, notably using the brand new cruisers of the Atlanta class (1883). Projecting naval power abroad was still against the policy isolationism. The board was divided as many supported a policy of commerce raiding. But the ermeging, more vical faction pointed out the specter of a fleet of enemy battleships blockading the US coast. New from Brazil with the Riachuelo class clearly motivated the second faction, which ultimately won.

The board eventually reached a consensus that if hostile warships arrived off the American coast, the navy had at least a few ships to guard the coast in 1884. Constraints were many, not only using existing docks, but having a shallow draft to enter all US ports and bases, and limited beam to manage canals (Panama was not done yet). The board came out eventually with a length of about 300 feet (91 m) and 7,000 tons.

In 1885 Bureau of Construction and Repair presented two designs to the Secretary of the Navy at the time, William Collins Whitney. One was a 7,500-ton battleship, one a 5,000-ton “armored cruiser”. Decision was passed onto the Congress, which cut a middle way, and authorized two 6,000-ton warships by August 1886. There was an international design contest to naval architects, which ultimately resulted in the Maine and Texas.

Maine as specified was to be capable of 17 knots (31 km/h; 20 mph) and fitted with a ram bow and double bottom. One option also popular at the time, was to be able to carry two torpedo boats. She was to be armed with smaller guns than Texas, hence her classification, four 10-inch guns, completed by six 6-inch guns, defensive armament and four torpedo tubes. Since the specs added that the main artillery “must afford heavy bow and stern fire.” it was not envisioned anyhting else than a repeat of the echelong solution. Turrets fore and aft would have defeated the purpose. Armor thickness was also precised. Texas only main chanage was to have 12-inch guns, thicker armor.

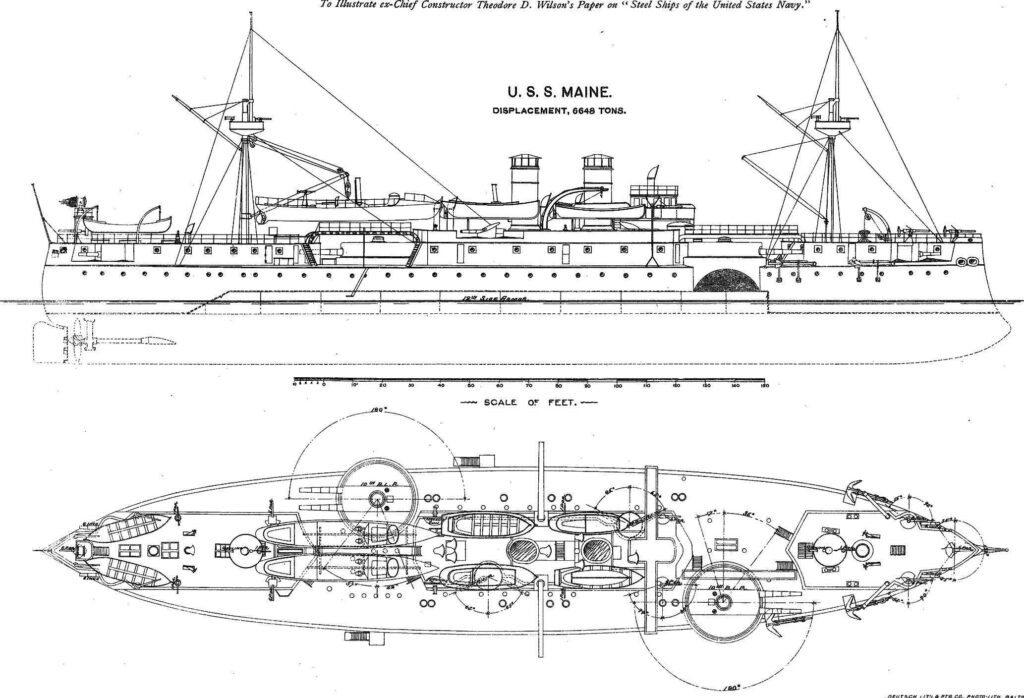

Marine Plans by architect T.D. Wilson – navsource

Naval Architect Theodore D. Wilson (chief constructor for C & R, member on the Naval Advisory Board in 1881) won the contest for USS Maine, whereas Texas was designed by British engineer William John (from Barrow NyD). Like the Riachuelo they featured the same echeloned arrangement, Maine’s design was obliged to be American–designed as per the contest. Congress voted construction of Maine on 3 August 1886. Her keel was laid down on 17 October 1888 at East Coast Brooklyn Navy Yard, much earlier than Texas (1 June 1889) at Norfolk, making her the largest US warship ever built. Construction time dragged on for many reasons and she was commissioned a month later than Texas. It was due American industry limited at the time like the years took before the delivery of her armored plating and bad luck as a fire in the drafting room hit her blueprints storage. Plans had to be reconstituted.

Unfortunately, naval tactics and technology advanced greatly in the meantime and by 1895 she was already obsolete. Notably, her role shifted more to commerce raiding and she was too heavy and too slow for this. She definitively appeared more as a second rate battleship than armoured cruiser in the modern sense, as those delivered by European navies. Harvey steel also contributed to this shift towards lighter cruisers. She ended caught between a rock and hard place and satisfied no role adequately in 1895, but maintained as “multirole” platform by default of anything else but mostly against asymetric threats as her main-gun arrangement was obsolete and her armour scheme was vulnerable. At least “showing the flag” was something she could do as she looked the part, and that’s exaclty what purpose she ended with.

Design of the class

Hull and general design

USS Maine measured 324 feet 4 inches (98.9 m) overall so she was longer than Texas (308 ft 10 in/94.1 m) and narrower with her beam of 57 feet (17.4 m) (64 ft 1 in/19.5 m for Texas), and max draft of 22 feet 6 inches (6.9 m) versus 24 ft 6 in (7.5 m) on Texas. But She displaced more, surprisingly at 6,682 long tons (6,789.2 t) versus 6,316 long tons (6,417 t) (full load) (1896) for Texas. Which was odd for a “cruiser”. She had a metacentric height of 3.45 feet (1.1 m) and possessed a moderate ram bow.

Although her proportions would made her faster than Texas, bad distribution of weight slowed her far more than anticipated. Her main turrets on the cutaway gundeck could almost not fire in bad weather, being drenched in seawater. Since they were mounted further apart coompared to Texas, so away from her center of gravity, she pitched and rolled heavily was less seaworthy as Texas.

The sponsoned echeloned position allowed indeed to fire fore and aft on paper, and was the result of 1870s Italian designs, notably by Benedetto Brin, later retook by HMS Inflexible, completed in October 1881. At the time, broadside fire was no longer desirable, but rather since Lissa, high manoeuvering tactics, since ramming was valued much. Broadside fire was seen as only valid in a line of battle, whereas the USN at the time only envisaged individually posted defensive ships. Engineers were still tasked to allow some transverse fire for opposite turrets, and so the Maine’s superstructure was separated into three islands in order to allow some limited arc of fire across her deck between sections. Ruptors would prevent the turret to turn further and even in that case, blast damage to the superstructure was inevitable.

Initial plans had her armed also with eight six-pounder guns and a possible seventh extreme bow six-pdr, later never installed. There was a single 6-pdr mounted at extreme aft and two six-pdrs forward, bridge, three at the stern placed in ways to fire cross-deck if needed

Protection

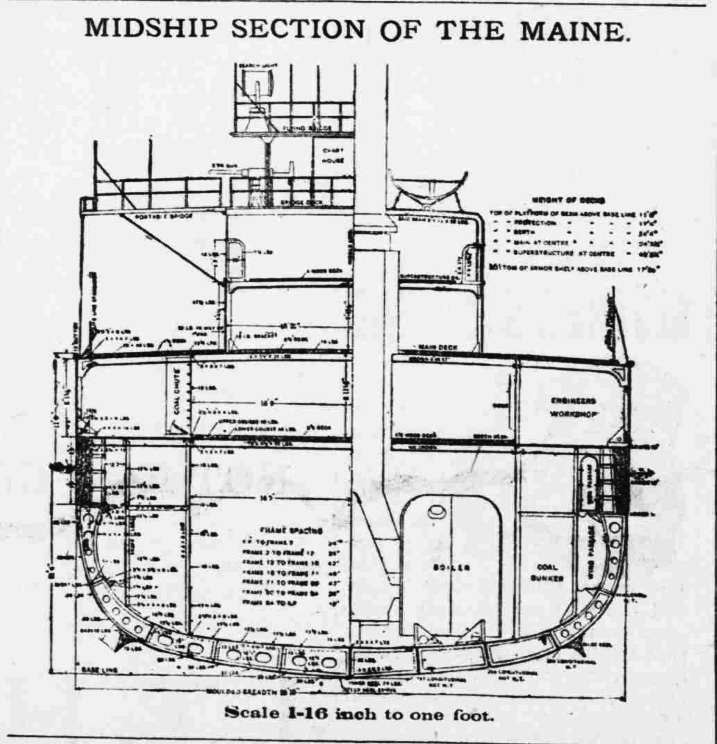

Miship section of the Maine – The Bourbon news April 1898.

-The main waterline belt was made of nickel steel, pre-Harvey type with limited hardness, 12 inches (305 mm) thick, tapering to 7 inches (178 mm) (lower edge).

-This belt was 180 feet (54.9 m) long, over the machinery spaces, main shells magazines, and 7 feet (2.1 m) high along along, including 3 feet (0.9 m) above waterline.

-The citadel started as this belt angled inwards for 17 feet (5.2 m) at both ends and then tapered down to 8 inches (203 mm).

-There was a 6-inch transverse bulkhead forward of the citadel.

-The forward protective deck section was 2-in thick (51 mm), from the bulkhead to the bow and died into the ram.

-The deck sloped downwards (turtleback) either beam up to 3 inches (76 mm).

-The rear protective deck section also arched downwards to the stern below the waterline, above the propeller shafts and steering gear.

-The circular turrets had 8 inches thick vertical walls.

-Main turret barbettes were protected by 12 inches, much heavier than the gun caliber. Below the main weather deck it was thinned down to 10 inches, until reaching the main protective deck.

-The conning tower forward was protected by 10-inch (254 mm) walls.

-Communication voicepipes and electrical leads were sheltered insided a 4.5 in (114 mm) armored tube.

-Hull with double bottom but only over 196 feet (59.7 m, from the foremast to the aft citadel bulkhead). Above it, the hull was sub-divided into 214 watertight compartments. Right through the middile of the sho range a centerline longitudinal watertight bulkhead, separating the engines.

When completed in 1895 the board was soon aware of the flaws of this protection:

-She lacked and adequate topside armor, having no protection against rapid-fire intermediate guns (HE shells), like Texas.

-Her nickel-steel armor was an alloy armor having a figure of merit of 0.67 (0.6 for mild steel), so barely hardened.

Later Harvey steel and Krupp armors from 1893 went up to 0.9 and 1.2 despite having the same density (40 Ib/Sq ft for 1-inch thickness), so the added protection could have save weight and led to a redistribution of protection or just achieving better speed. Harvey armor was adopted for the next Indiana-class battleships.

Powerplant

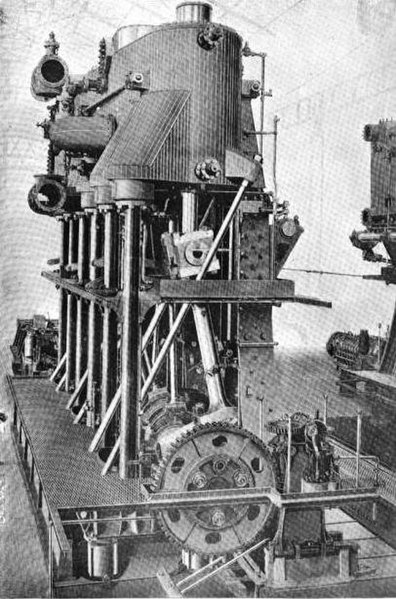

Published in a newspaper of the time, src navsource.org

USS Maine was the first to have a dedicated, very powerful machinery, awarded to N. F. Palmer Jr. & Co, Quintard Iron Works, New York. It was designed under direct supervision of future commodore George Wallace Melville, comprising two inverted vertical triple-expansion steam engines. Cylinder were 35.5 in (900 mm) aft, 57 in (1,400 mm) middle, 88 in (2,200 mm) forward from high to low pressure for a stroke of 36 inches (910 mm) for all three. They were inside two separated, watertight compartments and further protected by both bulkheads. In total output was 9,293 indicated horsepower (6,930 kW) as designed. The innovation was that these cylinders were mounted in vertical mode ubnlike previous horizontal mode allowed better protection below the waterline. Instead, trust was given to the armored deck and greater efficiency while the objective as well as lower maintenance costs, efficient running overall. To feed these, eight single-ended Scotch marine boilers were installed, with a working pressure of 135 pounds per square inch (930 kPa; 9.5 kgf/cm2) and 364 °F (184 °C).

USS Maine was the first to have a dedicated, very powerful machinery, awarded to N. F. Palmer Jr. & Co, Quintard Iron Works, New York. It was designed under direct supervision of future commodore George Wallace Melville, comprising two inverted vertical triple-expansion steam engines. Cylinder were 35.5 in (900 mm) aft, 57 in (1,400 mm) middle, 88 in (2,200 mm) forward from high to low pressure for a stroke of 36 inches (910 mm) for all three. They were inside two separated, watertight compartments and further protected by both bulkheads. In total output was 9,293 indicated horsepower (6,930 kW) as designed. The innovation was that these cylinders were mounted in vertical mode ubnlike previous horizontal mode allowed better protection below the waterline. Instead, trust was given to the armored deck and greater efficiency while the objective as well as lower maintenance costs, efficient running overall. To feed these, eight single-ended Scotch marine boilers were installed, with a working pressure of 135 pounds per square inch (930 kPa; 9.5 kgf/cm2) and 364 °F (184 °C).

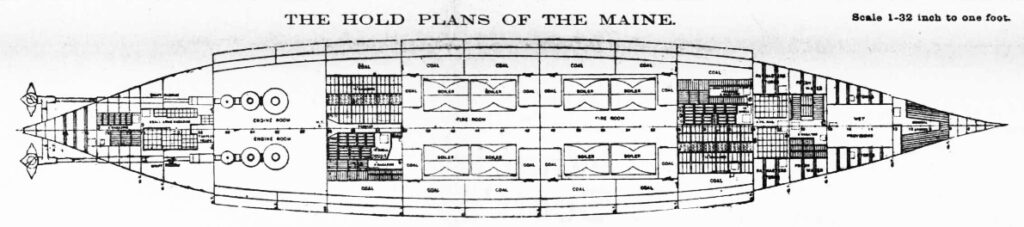

Hold plan – The Bourbon news April 1898.

On trials USS Maine achieved 16.45 knots (30.47 km/h; 18.93 mph), failing short of 17 knots as contracted. Autonomy depended on the bulkerage of some 896 long tons (910,000 kg) of coal in 10 bunkers each sides, bunkers, below the protective deck for stability. A low capacity for her size, but coherent with her mainly defensive role. She wouls have a hard time intercepting faster warships running at flank speed over large distances. Coaling at sea was difficult due to her protruding barbettes sponsons, or in very calm weather. She also had electrical lighting, and so required small dynamos also feeding her searchlights. They were dependent of the main propusion, however, which was to run at all times, further depleting her meagre coal reserves.

On trials USS Maine achieved 16.45 knots (30.47 km/h; 18.93 mph), failing short of 17 knots as contracted. Autonomy depended on the bulkerage of some 896 long tons (910,000 kg) of coal in 10 bunkers each sides, bunkers, below the protective deck for stability. A low capacity for her size, but coherent with her mainly defensive role. She wouls have a hard time intercepting faster warships running at flank speed over large distances. Coaling at sea was difficult due to her protruding barbettes sponsons, or in very calm weather. She also had electrical lighting, and so required small dynamos also feeding her searchlights. They were dependent of the main propusion, however, which was to run at all times, further depleting her meagre coal reserves.

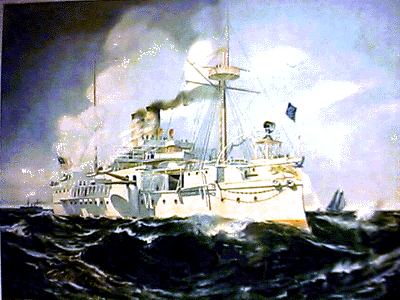

USS Maine’s three-mast barque rig was meant onlt for auxiliary propulsion, sparing cals for long-range cruising but limited in sail surface to a schooner rig albeit sailing plans shows square rigging was intended. Anyway her mizzen mast was removed in 1892, just after launch and she ended with a two military masts with fighting/spotting tops instead.

Cutout profile – The Bourbon news April 1898. Note the is called there a “second class battleship”

Armament

Main Artillery

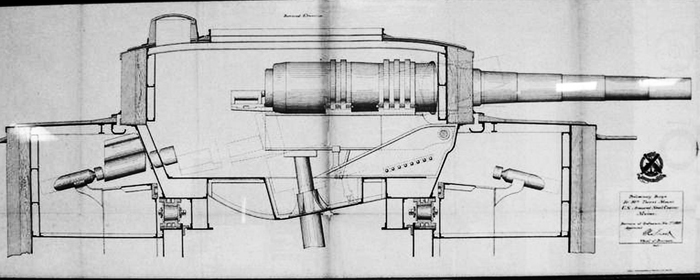

USS Maine had four 10-inch (254 mm)/30 caliber Mark II guns placed in two cylindrical “cheesebox” hydraulically powered Mark 3 turrets. The mountings only allowed a maximum elevation of 15°, −3° depression. Each cannon was supplied with 90 rounds, presumably all AP types, 510-pound (231 kg), existing the barrel as a muzzle velocity of 2,000 feet per second (610 m/s) and up to 20,000 yards (18,000 m) at max elevation. The plan was a starboard fore turret and and port aft turret.

Initial plans showed these mounted in open barbettes but due to the developments of rapid-fire secondary gun with high-explosive shells, Main received enclosed turrets, mounted one deck lower due to the added weight, which impacted seaorthiness, but each had a 180° main side, 64° other side field of fite, and they couldbe loaded at any training angle unlike Texas which external rammers obliged a centerline/abeam loading. Thus, Maine could fire faster, compensating for lighter shells. But this was modified in 1897 for Texas.

The Ecehelon arrangement’s lack of counterbalance cause USS Maine to heel over when both turrets pointed the same direction and cross-deck firing, if possible on paper, was only tried a few times as it damaged her deck and superstructure significantly. Like Texas, this arrangement showed too many drawbacks and was dropped afterwards.

Secondary Artillery

USS Main from eight, came down to six 6-inch (152 mm)/30 caliber Mark 3 guns in casemates along the hull: Two were located at the bow and stern to fire in chase and retreat, the last two amidships for broadsides only. Estimated elevation depressionwas circa +12/−7°. They were provided with 105 pounds (48 kg) HE shells existing the barrel at 1,950 feet per second (590 m/s) and with a max range of 9,000 yards (8,200 m), half the main batterry.

Light Guns

The anti-torpedo boat armament was initially less prevalent, but after 1886 the threat posed by Torpedo Boats became much more prevalent, and she had seven 2.2 inches or 57 mm (6 pdr) Driggs-Schroeder guns placed high up on the superstructure deck for a better field of fire. They fired a puny 6 lb (2.7 kg) HE shell at 1,765 feet per second (538 m/s), at 20 rounds per minuteand up to 8,700 yards (7,955 m), completing well the secondary artillery.

They also had smaller 1.5 in or 1-pdr 37 mm Hotchkiss and Driggs-Schroeder guns, four mounted on the superstructure deck, two in casemates at the stern, one on each fighting top. They fired a 1.1 Ib (0.50 kg) shell at c2,000 feet per second (610 m/s) but could land 30 of them every minute at 3,500 yards (3,200 m).

Torpedo Tubes

USS Maine as customary at the time had four 18-inch (457 mm) above-water torpedo tubes on the each broadsides. Since there was no torpedo industry in the US yet they were imported Whitehead models.

6-inches gun crew of the Maine, Library of Congress

Torpedo Boats

Anothr paper concept that was very popular at the time was the idea of a mothership having her own torpedo boat to attacj an anemy ship, or in her case, trade, but also enter and attack shipping in port, etc. This was introduced and tested in the 1880s until reaching the level of dedicated torpedo carriers. But the idea only was good on paper. The two puny vessels measured 14.8 long tons (15.0 t), steam-powered and armed with a single 14-inch (356 mm) torpedo tube forward, plus a 1-pdr gun. Plans showed their location, but none ws ready at the time. In fact, only one was built and could only reach 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph) by calm weather, just like any picket boat. Meaning in choppy seas, this would have been reduced to a crawl. The idea was abandoned and the TB ended at the Naval Torpedo Station at Newport in Rhode Island for training. The idea never resurfaced again. In 1895 it already fell out of favour.

Author’s illustration of USS Maine as completed in 1895, 1:350

⚙ USS Maine specifications |

|

| Displacement | 6,682 long tons (6,789 t) |

| Dimensions | 324 ft 4 in x 57 x 22 ft 6 in (98.9 x 17.4 x 6.9 m) |

| Propulsion | 2× shafts VTE, 8× Boilers 9,293 ihp (6,930 kW) |

| Speed | Speed 16.5 knots (30.6 km/h; 19.0 mph) |

| Range | 3,600 nmi (6,700 km; 4,100 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Armament | 2×2 10 in (254 mm), 6× 6 in (152 mm), 7× 6-pdr (57 mm), 4× 1-pdr (37 mm), 4× 1-pdr, 4× Gatling, 4× 18 in TTs |

| Protection | Belt 12 in, Deck: 2–3 in, Turrets 8 in, CT 10 in, Bulkheads 6 in |

| Crew | 374 officers and men |

Read More/Src

Books

Alden, John D. (1989). American Steel Navy: A Photographic History of the U.S. Navy. NIP

Allen, Francis J. (1998). “Honoring the Heroes: The Raising of the Wreck of the U.S. Battleship Maine, Part I”. Warship International. XXXV

“Battleship Maine”. The Spanish American War Centennial Website. www.spanamwar.com. 1996. 2 April 2012.

“Casualties on USS Maine”. Naval History & Heritage Command. US Navy Department. 6 February 1998.

Coughlin, Bill (2012). “U.S.S. Maine Memorial Marker”. Bill Coughlin.

Cowan, Mark D.; Sumrall, Alan K. (2011). “Old Hoodoo”: The Battleship Texas: America’s First Battleship, 1895–1911. CreateSpace.

Crawford, Michael J.; Hayes, Mark L.; Sessions, Michael D. (30 November 1998). “The Spanish–American War : Historical Overview and Select Bibliography”.

Dober, Mark; Keough, Daniel E. & Koehler, R. B. (2006). “Question 20/04: Artifacts from USS Maine (ACR-1)”. Warship International. XLIII(2)

Friedman, Norman (1984). U.S. Cruisers, An Illustrated Design History. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press (NIP).

Friedman, Norman (1985). U.S. Battleships, An Illustrated Design History. NIP

Gardiner, Robert, ed. (1979). Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships 1860–1905. New York: Mayflower Books.

Jackson, Robert (2004). Fighting Ships of the World. London: Amber Books

Krause, Paul, ed. (1992). The Battle for Homestead, 1880–1892: politics, culture, and steel. University of Pittsburgh Press.

Love, Robert W. Jr., ed. (1992). History of the U.S. Navy, Volume One: 1775–1941. Harriburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole Books.

“Maine (BB-2)”. Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History and Heritage Command.

Miller, David, ed. (2001). Illustrated Directory of Warships of the World. Osceloa, WI: Zenith Press.

Misa, Thomas J., ed. (1999). A Nation of Steel: The Making of Modern America, 1865–1925. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Morley, A. W. (1895). “Contract Trial of the United States Armored Cruiser Maine”. Journal of the Society of American Engineers.

Morrison, Samuel Loring, ed. (2003). The American Battleship. Osceloa, WI: Zenith Press.

Musicant, Ivan (1998). Empire by Default: The Spanish–American War and the Dawn of the American Century. Henry Holt and Co.

O’Toole, G. J. A. (1984). The Spanish War: An American Epic 1898. New York: W.W. Norton.

Paine, Lincoln P. (2000). Warships of the World to 1900. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Parkinson, Roger (2008). The Late Victorian Navy: The Pre-Dreadnought Era and the Origins of the First World War. Boydell Press.

Pater, Alan F., ed. (1968). United States Battleships: The History of America’s Greatest Fighting Ships. Monitor Book Co.

Peifer, Douglas Carl (2016). Choosing War. Oxford University Press.

Putnam, William Lowell (2000). Arctic Superstars. New York: Amer Alpine Club.

Reilly, John C.; Scheina, Robert L. (1980). American Battleships 1886–1923: Predreadnought Design and Construction. NIP

Rickover, Hyman George (1995). How the Battleship Maine was Destroyed (Second Revised ed.). NIP

“Sinking of USS Maine, 15 February 1898”. Naval History & Heritage Command. USN

“Survivors of USS Maine”. Naval History & Heritage Command. US Navy Department. 6 February 1998.

“The Destruction of USS Maine”. Naval History & Heritage Command. US Navy Department.

United States Army Corps of Engineers (1914). Final Report on Removing Wreck of USS Maine from Harbor of Habana, Cuba.

“USS Maine (1895–1898), originally designated as Armored Cruiser #1”. Naval History & Heritage Command. US Navy Department.

Weems, John Edward (1992). The Fate of the Maine. College Station, Texas: Texas A&M University Press.

Wegner, Dana (2001). “Chapter 2: New Interpretations of How the USS Maine Was Lost”. In Marolda, Edward J. (ed.). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Wisan, Joseph Ezra (1965) [c. 1934]. The Cuban Crisis as Reflected in the New York Press, 1895–1898. Octagon Books.

Allen, Thomas B. “Remember the Maine?” National Geographic, Vol. 193, No 2 (February 1998): 92–111.

Allen, Thomas B. ed. “What Really Sank the Maine?” Naval History 11 (March/April 1998): 30–39.

Blow, Michael. A Ship to Remember: The Maine and the Spanish–American War. New York: William Morrow & Co., 1992.

Foner, Philip S. The Spanish-Cuban-American War and the Birth of American Imperialism 1895–1902. London 1972

Samuels, Peggy and Harold. Remembering the Maine. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington DC, London 1995

Lithography of “remember the maine” musical about the Maine “Big Minstrel Jubilee” by WmH.West, 1898 (Library of Congress)

Links

NH 48621 USS Maine (1895-1898). Port quarter view, taken in Bar Harbor, Maine, 1895. U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command Photograph. (2016/05/09).

spanamwar.com USS maine

spanamwar.com coal fire Maine

spanamwar.com Maine Report

spanamwar.com Maine Mine report

https://www.history.navy.mil/our-collections/photography/us-navy-ships/battleships/maine.html

https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/museums/nmusn/explore/photography/ships-us/ships-usn-m/uss-maine-1895-1898.html

https://www.loc.gov/item/today-in-history/february-15/

flickr.com/ library_of_congress USS Maine photos

Nice illustration by donn thorson

https://www.pbs.org/crucible/tl10.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/USS_Maine_(1889)

http://navsource.org/archives/01/pdf/maine03m.pdf

arlingtoncemetery.net ussmaine.htm

archives.gov/ publications prologue 1998 spring spanish american war

Specifications for Triple-expansion Twin-screw Propelling Machinery for USS Maine

Proceedings by Municipal Engineers of the City of New Yor

Videos

Model Kits

3D

The short career of USS Maine

USS Maine was delayed multiple times and in 1890 annual report to congress, Secretary of the Navy wrote, “the Maine … stands in a class by herself” and expected the ship to be commissioned by July 1892. Sadly three more years were necessary, notably with little work to do as nickel steel plates were awaited from Bethlehem Steel, which promised the navy 300 tons monthly by December 1889 but had to wait for heavy castings and forging presses coming from Armstrong Whitworth in 1886, which arrived in 1889. Navy Secretary Benjamin Tracy secured an order to the Homestead mill of Carnegie, Phipps & Co. and signed a contract by November 1890 to supply of 6,000 tons of nickel steel. But the union caused strikes in 1882, and a lockout in 1889 to try and break the union, but the 1892 strike became one of the largest in U.S. labor history and further caused delays. The cruise was ultimately commissioned on 17 September 1895, three years beyond schedule with first captain Arent S. Crowninshield.

USS Maine was delayed multiple times and in 1890 annual report to congress, Secretary of the Navy wrote, “the Maine … stands in a class by herself” and expected the ship to be commissioned by July 1892. Sadly three more years were necessary, notably with little work to do as nickel steel plates were awaited from Bethlehem Steel, which promised the navy 300 tons monthly by December 1889 but had to wait for heavy castings and forging presses coming from Armstrong Whitworth in 1886, which arrived in 1889. Navy Secretary Benjamin Tracy secured an order to the Homestead mill of Carnegie, Phipps & Co. and signed a contract by November 1890 to supply of 6,000 tons of nickel steel. But the union caused strikes in 1882, and a lockout in 1889 to try and break the union, but the 1892 strike became one of the largest in U.S. labor history and further caused delays. The cruise was ultimately commissioned on 17 September 1895, three years beyond schedule with first captain Arent S. Crowninshield.

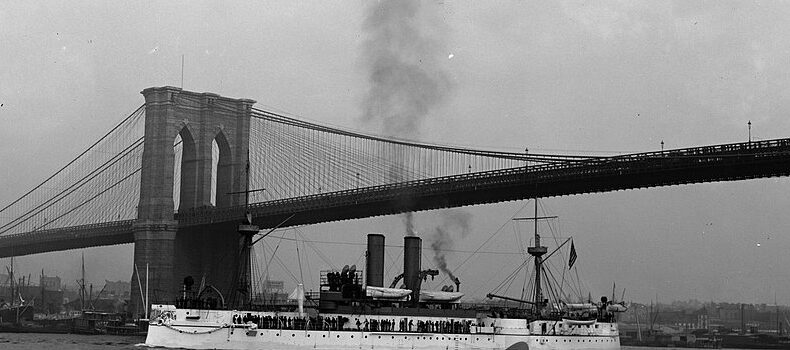

On 5 November 1895, USS Maine started her initial trials underway to Sandy Hook Bay, New Jersey. After two days she left for Newport, Rhode Island and fitting out. She test fired her torpedoes as well. She went to Portland, Maine, and reported to the North Atlantic Squadron for fleet training and drills. Her first and only operating port for the North Atlantic Squadron was Norfolk in Virginia and she trained in the Caribbean as welk. On 10 April 1897, Captain Charles Dwight Sigsbee took command, and by January 1898, after two years of drills with nothing notable, USS Maine was sent from Key West in Florida to Havana in Cuba, to protect American interests as the Cuban War of Independence raged on.

Entering Havana Harbor, January, 25, 1898

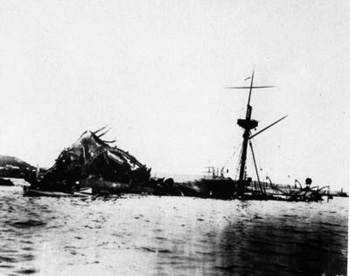

At 11:00 local time, January 25 she entered the harbour. At 21:40, 15 February, so in between her crew had time to make demonstrations and come ashore, an explosion wrecked Maine and she sank.

As the explosion ioccured in the evening, when night fell already, the crew were sleeping or resting in its quarters forward, precisely where the explosion occurred and of her full crew of 355 (26 officers, 290 ratings, plus a company of 39 Marines to protect US citizens ashore), 261 died in tota, including 2 officers and 255 ratings following the explosion, 7 were rescue by died later of burns, and one officer died later of apparent commotion. There were 94 survivors including only 16 that were not injured, including Captain Sigsbee and his staff as at the time, theor quarters were still located aft, in the “castle”, far from the blast. The nearby steamer City of Washington launched rescued boats immediately and assisted the survivors.

The story could have end there, but the event came out at a time the press was unchained against the Spanish rule over the Island and embraced the cause of the insurgents. It was part of a serie of events that would lead ultimaterly to the 1898 Spanish-American war, the explosion only served as a catalysts, well exploited by a campaign orchestrated by W.R. Hearst (which possessed the bulk of US press at the time, proving the leverage this media could have in the hands of a single man at the time).

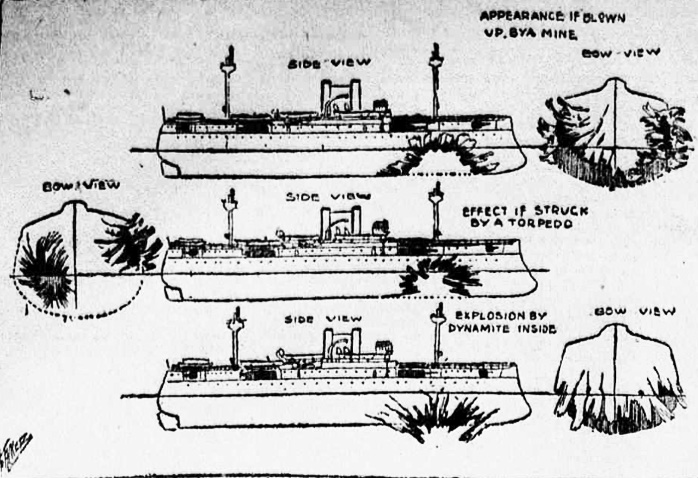

The investigation

The cause of the sinking was discussed right away, with President McKinley being woke up to hear the news at the white house, and commander Francis W. Dickins, USN called it an “accident” straight away. The consensus was not reached yet as Commodore George Dewey (Asiatic Squadron) initially thought this was due to Spanish action, but later changed his mind. Captain Philip R. Alger (expert on ordnance and explosives) immediately expressed his opinion this was most likely a spontaneous fire in the coal bunkers, but Assistant Navy secretary Teddy Roosevelt, given his personal agenda, saw this as premature, in a letter to the board.

“Mr. Alger cannot possibly know anything about the accident. All the best men in the Department agree that, whether probable or not, it certainly is possible that the ship was blown up by a mine.”

Then came the media storm. New York Journal (William Randolph Hearst) New York World (Joseph Pulitzer) gave this event an intense press coverage and their actions were later called “yellow journalism.” All incoming information was exaggerated and distorted, mixed with fake news in order to reach a narrative. This went so far as having a week later a daily average of eight and a half news page on the Maine. Reporters and artists were sent by boat to to Havana (as Frederic Remington) Hearst going so far as proposing a $50,000 reward to catch the authors of the “mining”.

Then came the media storm. New York Journal (William Randolph Hearst) New York World (Joseph Pulitzer) gave this event an intense press coverage and their actions were later called “yellow journalism.” All incoming information was exaggerated and distorted, mixed with fake news in order to reach a narrative. This went so far as having a week later a daily average of eight and a half news page on the Maine. Reporters and artists were sent by boat to to Havana (as Frederic Remington) Hearst going so far as proposing a $50,000 reward to catch the authors of the “mining”.

The World press, by default of better judgment, and to jump on the easy bandwagon of sensationalism, seemd to opt for this narrative as well. Spain via its ambassador expressed condoleances while underlying the agressive campaign, while the NYJ denounced the Spanish “treachery, willingness, or laxness” to not secure Havana Harbor. Compounded by growing tales of Spanish atrocities in Cuba with graphic depiction only fan the flames in the general public.

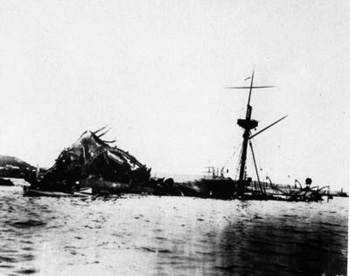

Havana’s wreck, from a postcard “Remember the Maine”, Library of Congress

Hearst was the first to call for retaliatory military action in Cuba, not waiting for the investigation conclusions, citing various naval officers believing this could not be an on-board accident. The publication of the Navy investigation report was due after a month, and so newspapers, including the major Washington DC paper, reported before hand this not accidental, but the declaration of war was long in coming still. The atmosphere created coukd have been abated. The own Spanish investigation found that spontaneous combustion of the coal bunkers was the cause, only to be ruled out by the Sampson Board, citing a torpedo. President McKinley denied in his memoirs the the Maine was the casus belli, but rather perceived atrocities and loss of control in Cuba. Rallying cries of “Remember the Maine! To hell with Spain!” nevertheless continued to fuel the highly volatile atmosphere and ultimately, war was declared cia the Congress by April 21, 1898, two months after Maine was lost.

The Spanish enquriy comprised the officers Del Peral and De Salas, and was countered in the US by the Sampson Board in 1898 and later the Vreeland board in 1911, so long after the events. The final one was lef by no lesst than Admiral Hyman G. Rickover (father of Nuclear submarines) in 1976, the National Geographic Society in 1998 this time with computer simulations. The forward magazines detonated for all, but the exact cause could not be attributed with certainty. Nevertheless it caused, via US expansionism and “manifest destiny”, later the “great white fleet”, the fall of the Spanish Empire. Indeed on paper in 1898, the Spanish fleet ws superior to the USN.

The Spanish Del Peral and De Salas inquiry collected evidence from officers of the naval artillery examining remains of the Maine and pointed the spontaneous combustion of the coal bunker closest to the munition stores as most likely cause and possible action of varnish, drier or alcohol, pointing that if a mine was the cause, there would have been a visible column of water present, dead fish, and that due to the quartedeck watch and calm waters, noone could be able to approach undetected, and such explosion would have been prepared in secret and detonated by electric cables, not found on site. but no cables had been found. They also pointed that a mine blast was almosty never the cause of an ammunition stores to detonate, locatyed furthern inwards the ship, rather fire inside. Unsurpringly they were not reported by US press.

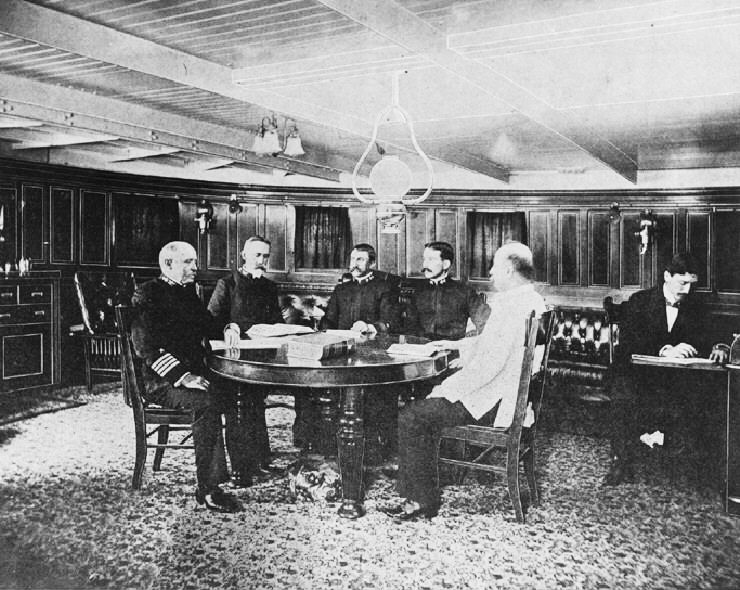

The 1898 Sampson Board’s Court of Inquiry was ordered after the incident under Captain William T. Sampson, and the Spanish governor of Cuba which proposed a joint Spanish-American investigation was not heard. Spanish officers and General Blanco were reported to express sympathy and Spanish minister of colonies, Segismundo Moret, pressed local authorities in Cuba to mount an investigation to avoid the blame.

The boar was the choice of the Secretary of the Navy with gave its task to the commander-in-chief of the North Atlantic squadron, shortlisting junior line officers including a court president until navy regulations had Captain Sampson as senior to Captain Sigsbee to direct the board, making a first reunion and started investigate in La Havana on 21 February, taking survivors testimonies, witnesses and divers looking at the wreck but the gap between the proceedings and findings hd many inconsistencies. More so, only one technical witness, Commander George Converse (Torpedo Station at Newport) was heard. Converse again pointed our the coal-bunker fire as a likely cause, as the heat, so close adjacent to the ammunition room, on already decomposing, volatile gunpowder unde rintense heat in these latitudes the past days, was no unlikely. In the end, the board concluded a mine caused the explosion of her forward magazines, with master proof that many witnesses reported hearing two explosions and divers reporting the keel was bent inward. It was sent to Washington on 21 March:

At frame 18 the vertical keel is broken in two and the flat keel is bent at an angle similar to the angle formed by the outside bottom plating. … In the opinion of the court, this effect could have been produced only by the explosion of a mine situated under the bottom of the ship at about frame 18, and somewhat on the port side of the ship.

In the opinion of the court, the Maine was destroyed by the explosion of a submarine mine, which caused the partial explosion of two or more of her forward magazines.” (the court’s 7th finding). The court has been unable to obtain evidence fixing the responsibility for the destruction of the Maine upon any person or persons.

The 1911 Vreeland Board’s Court of Inquiry was by a 1910 decision to also facilitate the recovery of bodies, to be buried in the United States. Plus the Cuban government wanted the wreck removed from the Harbor, offiring the possibility to examine it in greater detail. Greater objectivity was awaited, notably due to the use of many certified engineers. This started by December 1910 by buuilding a cofferdam around the wreck, remove all seawater, and lead the examination by late 1911 with the court statuing between 20 November and 2 December 1911 under RADM Charles E. Vreeland, concluding that an external explosion, again, triggered magazine’s detonation, located farther aft and lower-powered. Corpses discovered meanwhile were extracted and buried in Arlington while an intact portion of the hull was refloated, towed and ceremoniously scuttled at sea, on 16 March 1912.

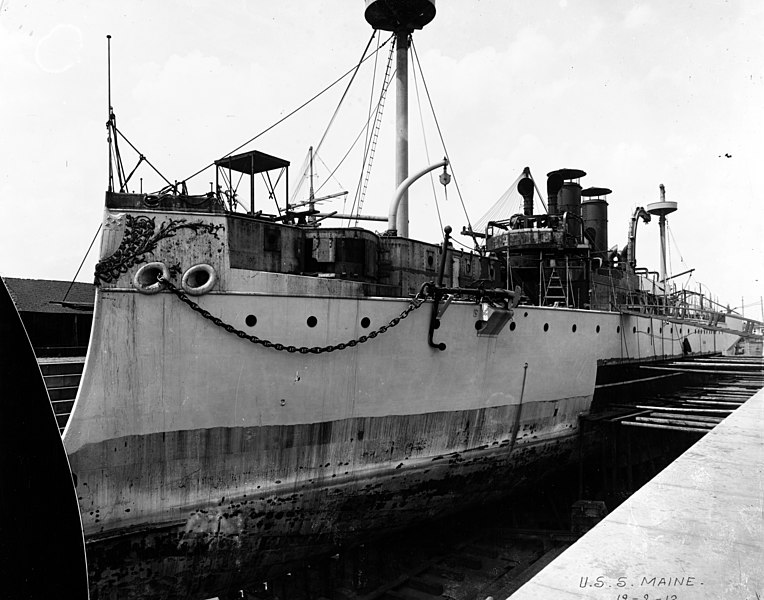

USS Maine in drydock after her first fleet campaign in 1896-97

In 1974 Hyman G. Rickover became obsessed by the disaster and started his own private investigation in 1974 crossing reports fro the two official inquiries, and original documentation, concluding spontaneous combustion was the most likely cause, just as the Spaniards concluded from the very start, with coal in the adjacent bunker slowly heating up the thing metal wall separating it folm the ammo storage area. In fact the mere contact between the red hot wall and charges was enough. A book was published in 1976, “How the Battleship Maine Was Destroyed”. Given the fame of Rickover at the time, it sold moderately well.

In 2001 the book “Theodore Roosevelt, the U.S. Navy and the Spanish–American War” by Wegner, offered additional details and made an in-depth historiography of the investigations, he notably on the photos taken in 1911, showing “no plausible evidence of penetration from the outside”. He pointed out a change in the type of coal used and the type of separation between both compartment as “highly conductive” indeed. Bituminous coal burned at a hotter temperature than anthracite coal but is considerably more volatile and release large amounts of “firedamp”, a mix mostly of methane. As tested it was explosive at 4%-16% concentration in the air already. Iron sulfide (pyrite) also contributed by its oxidation, exothermic and added to the spontaneous combustion in the next locker.

It was used to strike sparks to ignite gunpowder and if stored immlediately close to the bulkhead, could have cooked off. In the end, many bunker fires had been reported after switching to the new coal before even Maine’s explosion. He also cited a 1997 heat transfer study by Nat. Geographic that was also confirming it. The commissioned analysis was done by Advanced Marine Enterprises (AME) for a later documentary linked to the centennial of the sinking of USS Maine, using computer modeling. Results however were still inconclusive as it did not ruled out a small, handmade mine, compounded by the soil depression beneath the Maine.

There was also the 2002 Discovery Channel History investigation but given its later reputation (ancient aliens anyone ?) i will leave “Death of the U.S.S. Maine” out. Let’s just say it identified a weakness or gap in the bulkhead separating coal and powder allowing a fire the link the two without indirect bulkhead transmission.

Of course given the times, conspiracy theories had been many, notably in Spanish-speaking media for a false flag operation. In the end, the wreck, for what was left, was rediscovered on October 18, 2000, under 3,770 feet (1,150 m), 3 miles (4.8 km) northeast of Havana by a Toronto-based expedition company. They accidentally stumbled across her while testing underwater exploration technology with Cubans. It was not her reported scuttling site, but currents pushed her further east when sinking. It was duly explored by a ROV and in generally good conditions. By February 1898, more recovered bodies were interred in the Colon Cemetery in Havana, injured sailors sent to hospitals in Havana and Key West, some buried there. By 1915, President Woodrow Wilson dedicated the USS Maine Mast Memorial at Arlington.

Of course given the times, conspiracy theories had been many, notably in Spanish-speaking media for a false flag operation. In the end, the wreck, for what was left, was rediscovered on October 18, 2000, under 3,770 feet (1,150 m), 3 miles (4.8 km) northeast of Havana by a Toronto-based expedition company. They accidentally stumbled across her while testing underwater exploration technology with Cubans. It was not her reported scuttling site, but currents pushed her further east when sinking. It was duly explored by a ROV and in generally good conditions. By February 1898, more recovered bodies were interred in the Colon Cemetery in Havana, injured sailors sent to hospitals in Havana and Key West, some buried there. By 1915, President Woodrow Wilson dedicated the USS Maine Mast Memorial at Arlington.

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign