Warsaw Pact Navies (1955-1991)

East Germany, Poland, Romania, Bulgaria, Albania, Czechoslovakia, Hungary

East Germany, Poland, Romania, Bulgaria, Albania, Czechoslovakia, Hungary

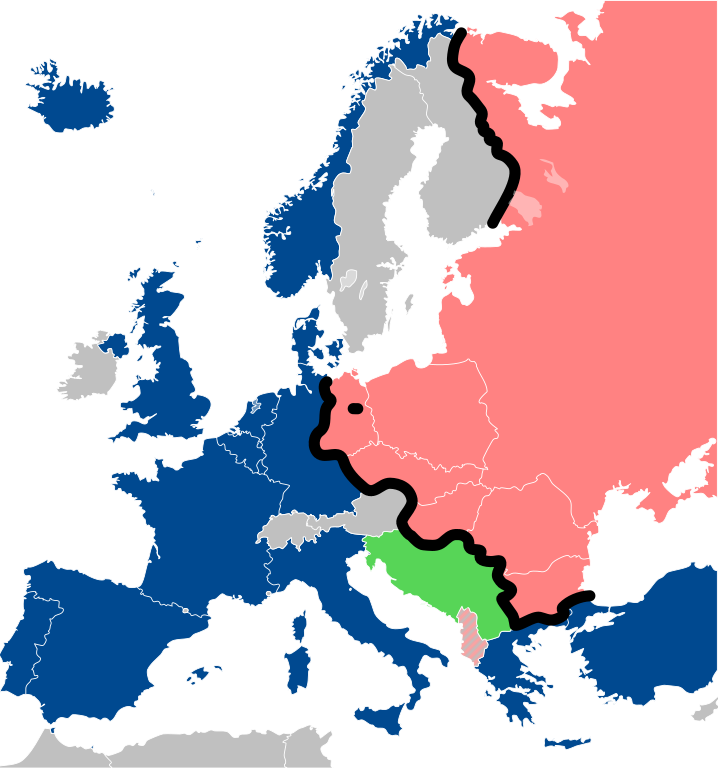

Refresher: The Warsaw Pact

Presidential palace of Warsaw, where was signed the pact

The anthitesis of NATO, created in 1949 by the USA, Canada and some Western European Powers of the time, was Stalin’s response to what he considered a threat to soviet future expansion. The irony was that USSR was proposed to join the alliance at its creation, but Stalin flatly refused, and so for satellite countries now under his sphere of influence. So why waiting until 1955 ? Indeed Stalin never really wanted an “alliance” considering eastern countries now “piloted” from Moskow being only subjected to automatic de facto military contribution to USSR, which still stationed considerable forces in these countries at that time. However after the death of Stalin in 1953, the new USSR’s premier, Nikita Kruchtchev started to ease this domination with these countries, allowing some autonomy, including in the creation of their armies -provided they still ordered their assets to Moskow and stayed in its the strict military supervision as well.

Therefore, more as a counterweight to NATO than real concession of autonomy (in the sense Western European nations were), Albania, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, East Germany, Hungary, Poland and Romania as well as Yugoslavia were all summoned to join the Moskow-driven military alliance. It was a collective defense treaty, as the term “defense” was more likely to gain suffrages within eastern population. NATO was also afterall flagged as defensive. It was called the Warsaw Treaty Organization (WTO), and paraphed officially as the “Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance”. For the west it was simply called the “WP” for “warsaw pact” and conveyed a way to describe the combined forces beyond the iron curtain although all agreed USSR was the sold real threat here.

First off, Yugoslavia’s Tito saw its relations with Stalin soured to no return point and the split was started in 1948 and consumed with US aid, but redeemed in 1951 as Tito himself recoignised a Soviet attack was inevitable regardless of military aid from the West. Yugoslavia was therefore was included after some discission in the Mutual Defense Assistance Program. The latter was latter augmented to Finland.

The Warsaw Treaty’s organization was two-fold, a Political Consultative Committee which handled political matters, and a Combined Command of all Armed Forces headquartered in Warsaw in Poland. The Supreme Commander was also a First Deputy Minister of Defence of the USSR, combining this as Chief of Combined Staff. So behind an international collective security alliance facade, USSR stil ruled the dices and made decision, like the fist large scale operation. It was not unlike the dominant position of the United States anyway.

The Wa-Pac strategy was driven by the desire of the USSR to prevent Eastern Europe to be subjugated and became a near-border threat. Ideological and geostrategic reasons also went into the mix. Ideologically, Soviet Union still claimed the definition of socialism and communism as the leader of global socialist movement. This implied military intervention if any country would appear to violate core socialist principles and dogma. It was reinstated in the Brezhnev Doctrine.

The Warsaw pact made a single large scale intervention: The invasion of Czechoslovakia in August 1968 or “prague spring”. All but Albania and Romania participated and the first latter withdrawn from the pact. The Pact stood strong at least in appearance until the Revolutions of 1989. The second shaking event for the pact was East Germany withdrawing following German reunification in 1990. Indeed, East Germany among all nations was seen as by far the strongest. On 25 February 1991 at a meeting in Hungary, the Pact was declared obsolete by the defense and foreign ministers of the six remaining member states. As USSR was dissolved in December 1991, the former Soviet republics still formed a Collective Security Treaty Organization but gradually over 20 years these countries joined NATO, including separate Czech Republic and Slovakia and Baltic states. The loss of this “buffer” for Moskow was considered a sever blow, more so as former easter countries joined NATO, always considered a threatening organization for Russia.

The Warsaw Pact Naval side

Romanian naval ships in 1990

Of course, these eastern countries had a limited navy, or maritime facade, if any, and were totally dwarved by the size and extension of the Soviet Navy. We will undergo a review of all of these, but to summarize:

-East Germany and Poland had a Baltic facade. Both also had a long maritime tradition, ports and shipyards and kept a sizeable navy, albeit focused on specific tasks

-Albania had an adriatic shore

-Bulgaria and Romania had a black sea shore

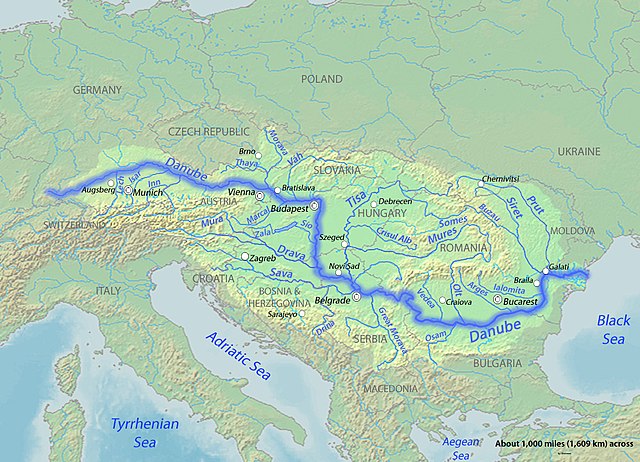

-Czechoslovakia and Hungary had a riverine shore (The Danube, also acting as border).

For all this, geostrategic consideration were of course taken in account to try and specialize these naval forces in the frame of regional defense, incliding many scenarios. For exemple, both est Germany had a role to play to interdict the Baltic by using mines (a strategy valid already before WW1), and had a support role by using FACs as well as eliminating enemy minefields. Romania and Bulgaria could participate to the defense of the black sea against any NATO attack (lkely coming from Turkey), again with affordable minelayers and FACs. Romania however had greater assets and could bring support to larger off-shore operations with a destroyer and four frigates, but in the 1980s. Poland had three destroyers and a number of submarines as well as some amphibious vessels and for course a number of patrol ships/crafts. East Germany only had frigates and corvettes plus some amphibious ships, its real strenght being in FACs and sub-chasers, patrol crafts, and as said above, mine warfare vessels. Most of these ships were built locally (a great difference with other Wa-Pac countries) and had an excellent quality reputation, while still provided with Soviet armament for standardization.

In the end, Albania had three submarines, several series of FACs, patrol crafts and minesweepers, incluing Chinese-provided vessels, a notable difference with other countries of the Pact. Bulgaria had a single destroyer and two, then three (1985) frigates, several submarines, some landing ships, corvettes, and as the others, FACs and minesweepers. Czechoslovakia and Hungary ad the first had a patrol riverine force of 18 crafts, while Hungary had its Danube flotilla rebuilt entirely in 1948, at first with transferred ships, then locally-built reiverine vessels, and was by far the strongest riverine force of the pact (outside USSR itself).

Soviet direction

USSR kept the rank and status of a sea-going naval superwower. They were supposed to integrate these fleets within operational objectives in case of war. As for NATO’s smaller navies, they specialized, notably in mine and ASW warfare. Main antiship combat was kept as a prorogative with integration through multinational coordination exercizes, and so did the Warsaw pact to some extent.

Data Published by the Two Alliances (1988-1989) |

||

|---|---|---|

| Types | NATO estimates | Warsaw Pact |

| Submarines | 200 | 228 |

| Submarines-nuclear powered | 76 | 80 |

| Large surface ships | 499 | 102 |

| Aircraft-carrying ships | 15 | 2 |

| Aircraft-carrying ships +cruise missiles | 274 | 23 |

| Amphibious warfare ships | 84 | 24 |

Warsaw Pact Fleets in detail

Albania

Albania

Albania, uniquely among the smaller nations, freed herself from Second World War Axis occupation using her own military forces. An underground army was set up and commanded by the Communist Party, which seized power in 1944 after the country was liberated. With the govermment formed by Enver Hoxha, a totalitarian communist state was set up and plans for rapid industrial development were drawn up, despite lack of capital, know-how and material wealth. The scale of industry proved to be inadequate to supply any kind of fighting craft and the status of the Albanian naval forces has reflected changes in the political sympathies of the regime since the end of the war.

Birth of a modern Albanian navy (Soviet era)

Until 1948 Albania was a satellite of Yugoslavia with a customs as well as a monetary union. The Albanian naval forces, part of the ‘People’s Army’ at that time, were supplied by the Soviets with some minor craft while Yugoslavia helped to restore two old minesweeping tenders: After the expulsion of Yugoslavia from the Cominform, and the overpowering of the pro-Tito group by the Stalinist faction in Albania, the country became a close Soviet ally despite territorial isolation, and had to rely on the Soviet Union for both technical advice and capital loans.

Albania was valuable to the Soviet Union as she provided her with Mediterranean bases for the Soviet Navy. After joining the Warsaw Pact in 1955 Albania allowed the Soviet Union to begin construction of base facilities at Sazan (Saseno) Island, in the Gulf of Valona. In exchange, cancellation of the large Albanian debt was announced by the Soviet Union in 1957 and large amounts of credit made available for the modernisation and expansion of the armed forces. During 1956-61 the Albanian Navy was gradually separated from the Army to become a fully independent service,like the Air Force.

Soviet Technical advices and capital loans to Albania were valuable to her Navy. Aner joining the Warsaw Pact in 1955, and the government purchased two “Whiskey” class submarines, six MTBS of the ‘P4’ type, two minesweepers of the T 143 type, six inshore minesweepers of the T 301 type, four ‘Kronstadt’ class patrol craft, eleven minesweeping boats and a number of auxiliaries.

Albanian left the WaPac and aligned on China

The new Soviet credit dried up by the late 1950s which, together with Khrushchev’s dislike of the strict Stalinist course maintained by the Albanian government, inclined Tirana to tlirt with Red China. When a rift between the two communist giants became evident, public disapproval of the Chinese viewpoint was disguised by the Soviet Communist Party as an attack on Albania. This resulted in diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union being severed in December 1961. Albania effectively withdrew from the Warsaw Pact and deprived the Soviet Union of her base at Sazan island, seizing two “Whiskey class submarines there. The Soviet-made ships were commissioned and maintained with Chinese assistance, giving the Albanians an effective task force of three submarines and six MTBS.

However lack of spares soon decreased their efficiency. Transfer of Chinese craft was initiated in 1965 with six MTBS of the ‘P4′ type and provided Albania with an effective squadron of fast Attack craft which by the late 1970s consisted of four missile craft of the “Hoku’ class, thirty-two torpedo hydrofoils of the “Huchwan’ class and six patrol craft of the “Shanghai IP class. This force of comparatively new craft despite their somewhat obsolescent design ind favourable strategic location of bases gave the Albanians the ability to control traffic through the 50-mile wide Strait of Otranto, altbough the strained relations between Albania and China disclosed in the late 1970s may have affected the supply of spares for the Chinese-made craft.

A dilapidated fleet (1980s)

Despite sparing use of vessels and production of rudimentary spare parts, the fleet could not be maintained for long without foreign assistance. As a result since the carly 1980s some vessels have either semi scrapped or placed in reserve, while others have been cannibalized for spares. In 1993 most of the vessels were in poor condition. The number of operational units continues to decline due to the lack of spare parts. Submarines were non-operational after the fall of USSR, with just one T 43′ class and two T 301′ class minesweepers spotted at sea. Following standard Eastern Bloc practice, Albanian ships recognition numbers were periodically changed.

The new UE-backed fleet (2000s)

The condition of her naval vessels reflects the economic state of Albania. After 46 years of strict Stalinist economic management, the Country had the lowest GNP in Europe. This, and phantasmagoric dreams such as building nuclear shelter instead of houses created fertile land for the anti-communist ideas that came from other Warsaw Pact countries left.

The Communist Party faced by growing internal opposition, but the county slowly recuperated by its integration to the UE and donations allowed to reach a new level of operational readiness, at least to perform its basic green water needs, of coastal police and fishery protection, reaching 1,000 Personnel and 19 Patrol Vessels as of today.

As a result of the 1998-2004 agreements, donated patrol vessels ex-US and ex-Italian for SAR started with five boats in 1998, six boats in 2002, five in 2004. An agreement was concluded that year with Italy with the latter providing equipment and technical assistance to the Albanian Naval Force, to cover its basic needs, but also patrolling to catch migrant boats. In 2007, the Albanian Navy was reorganized into two flotillas and a logistics battalion.

Fleet strenght in 1947

-2 Italian motor boats of the Tirane class, former MAS captured and retroceded by the USSR.

-2 ex German MFP craft used as landing ships tanks (1943), discarded in the 1970s.

-Minesweeping tenders, former Yugoslav Marjan, Mosor. Sticken 1967.

Additions

-7 Vosper class MTBs, ex-lend-lease in 1950, discarded 1960s

-3 KM 4 minesweeping boats transferred 1945, stricken 1967

1980s cold war fleet

Ex-Whiskey class

Three Type 053 submarines transferred by the Soviet Union in 1960, plus two more seized in 1961, numbered 512, 514, 516 and the fourth unnamed, kept for spares, harbor training and charging station.

Stricken in 1976 and cannibalized for spares. In the 1980s only one was apparently kept operative, two renamed 552 and 523 in 1993, still active until the late 1990s. Now scrapped.

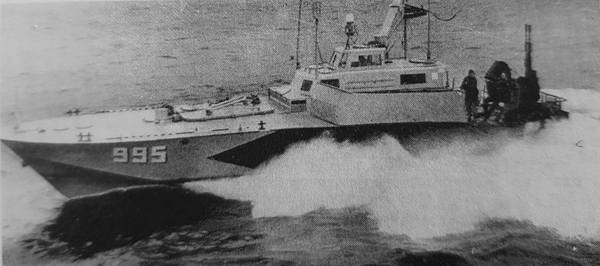

Fast Attack Crafts:

-12 ex-Soviet P4 FAC(T), six delivered 1956, six Chinese-built in 1965, with a twin DsHK and no radar. All stricken 1987.

-31 Huchuan class FAC hydrofoils. Various batches built in Shanghai, transferred 1968-74. Conditions degraded due to lack of spares and maintenance still reported operational in 1987, but unknown status for the 1990s.

-4 Hoku class FAC(M) transferred in 1976-77, stricken 1982-84.

Patrols Crafts:

-Four Kronstadt class transferred 1958 numbered originally 191, 192, 502, 504. Two upgraded to the latest ASW standards in 1961 and claimed back in 1965, still extant 1987, status unknown for the 1990s.

-Six “shanghai II” class patrol crafts, four transferred 1974, two 1975, extant 1987.

Minesweepers:

-2 T43 ww2 ocean minesweepers acquired august 1960, extant 1987.

-6 T301 WW2 inshore minesweepers (three pairs) 1957-60, fitted with navigation radar in the 1980s, One discarded 1979, the other extant 1987.

-11 PO-2 minesweeping boats 1957-60. Stricken 1988-89.

Bulgaria

Bulgaria

The Frigate Smeli (“Brave”) in 2006, Varna

During the closing stages of the Second World War Bulgaria fell into the Soviet sphere of influence and the Bulgarian Army came under cccccavist command. The Soviet troops’ presence and a strong pro-Russian sentiment in the country were the major factors which enabled the Communists to seize power more easily than in other countries of the recently emerged Soviet bloc. After the peace treaty with the Allies was signed and the new constitution had come into force, the Soviet troops left Bulgaria at the close of 1947 and remodelling of the country on Soviet lines began.

Nationalisation of private industry was started immediately, collectivisation of peasant holdings was pursued while industrialisation became one of the principal aims of economic policy regardless of the lack of raw materials and of technically educated manpower for heavy industry. By 1950 the strict Stalinist course was adopted throughout and in May that year a new army command was formed with a Soviet officer of Bulgarian origin taking the post of Minister of National Defence and C-in-C of the armed forces.

With the help of Soviet advisers the amed forces were equipped and reorganised on the Soviet model. By 1953 they numbered about 220,000 despite the peace treaty limitations. The treaty of 10 February 1947 ordered a considerable reduction of the Bulgarian armed forces as compared with their prewar status; maximum permitted strength included an army of 55,000, an air force of up to ninety aircraft (with no bombers) while the tonnage limitation for the navy was set at 7250t with personnel not Exceeding 3500.

Ex-Italian submarine support ship used for the Foxtrot class submarines

Despite the spectacular build-up of the army, the naval forces were not so successful as the Soviet Black Sea Fleet had w resources to spare for her ally at that time. However, because of endent neglect of the Bulgarian Navy, a Novik class destroyer ered for the Imperial Russian Navy), three war-built M class Coastal submarines and four ex-German M-boats of 1935 type were transferred from the Soviet Union to form the nucleus of the ‘People’s Navy

After Stalin’s death the country gained a considerable margin of forces were reduced by 45,000 while supplies of modern equipment began to arrive. During the late 1950s one . In 1955 Bulgaria joined the Warsaw Pact and an armed destroyer of the Ognevoi class was added to the list of transfers, as well as a number of modern vessels- two ‘Whiskey’ class subs and later two ‘Riga’ class frigates, ecight ‘P 4′ type MTBS, two “Kronstadt’ class patrol craft were purchased in the Soviet Union. In December 1959 command of the armed forces was taken over by a Hulgarian officer and Soviet advisers were withdrawn.

There were a few additions to the Bulgarian Navy during the 1960s, but the present strength was largely built up under three successive Five Year Plans since 1970. Naval power currently encompasses short-range landing and minesweeping capabilities, backed by some ASW capacity and striking forces of FACS and naval aviation. This expansion programme, backed by construction of new auxiliaries (some built domestically), was completed by the end of 1985 and resulted in a balanced coastal navy with some, albeit limited, projection capability.

The modernisation programme commenced in the later 1980s with the transfer from the USSR of two Romeo’ class submarines, one “Poti’ class corvette and two Polnocny’ class landing ships, apparently to replace those acquired in the early 1970s. Possible further transfers were to include more landing ships as well as ASWS and FACS, but these plans were forestalled by the deteriorating Bulgarian economy, in particularly since the mid-1980s. A reduction of 12% in the military budget was announced in 1989, including the scrapping of five warships (corvettes and some landing craft).

A Vanya class minesweepers

Following the overthrow of President Zhivkov’s regime in 1990, free elections, and the break-up of the Warsaw Pact, plans for further military expenditure were shelved because of the still critical economic

situation. Bulgaria now follows a policy of seeking membership of NATO and associate membership of the European Community. As the country’s economy struggles to improve, the navy is being further reduced. It is planned that by the year 2000 the Bulgariari Navy will comprise only three submarines, FACS, small patrol and mine warfare cruft and helicopters.

The Bulgarian navy in 1990 consisted of the Black Sea Fleet and the Danube Floulla. The fleet was organised into one division each of submarines, ASWS, FAC(M)s, FAC(T)s and one brigade each of landing ships and minesweepers. In 1992, the navy had a total of 8800 men, of whom 2100 were afloat, 2200 in coastal defence (twenty batteries with over one hundred 130mm and 6-in guns as well as three battalions of six truck-mounted SSC-2b ‘Samlet’ missile launchers), and 200 in naval aviation.

Slava, Bulgarian Type 033 – the Chinese Romeo, last in existence and now retired.

By 1994, the total had been reduced to 5,400 men. Personnel are largely ratings on three years’ national service (eighteen months since 1991). The fleet headquarters and main buse is at Varna, and other bases are at Burgas and Sozopol. The Danube River Flotilla, which is headquartered at Victin, and has bases at Atiya and Balchik, operates ex Soviet PO 2′ class boats and two fast patrol booats. The naval aviation division with stations at Varma and Burgas, has Mi-14 Haze and twelve Mi-2 Hoplite’ and Mi-4 Hound’ helicopters.

As of today, the Bulgarian Navy is 4,100 personnel strong, and rejuvenated thanks to the West, with three ex-Wielingen Belgian frigates, a single Koni class (Smeli), a tarentul, two Pauk class covettes, three ex-French tripartite mine hunters, one Olya, four Vanya, three Sonya, and a Yevgenya ex-Soviet minesweepers, and the 13 support ships of the 18th and 96th support divisions, with a single ex-Polish ship, an Italian, and the rest all Bulgarian-built, plus a training vessel. Two German OPVs are to be delivered in the late 2020s. Bulgaria also operates 2 Eurocopter AS565 Panther and a single Eurocopter AS365 Dauphin.

WW2 vessels

Still in service in 1954: Torpedo Boats of the Drzki class (Built in France, 1907). The tiny Bulgarian Navy in WW2 was bolstered by transfers from Germany: Three S 2 class S-Bootes, named F1 to F4. These 1939 47.8 tonnes vessels were transferred in 1939 (two) and one last in 1941. The fourth (F-4) was captured by Soviet forces en route, retroceded after some service, as TKA-960. It was retuned in April 1945. They served until 1953 and were converted as avisos. The second batch of early FACs (MBTs) were the captured Dutch T52 class vessels, transferred by the Germans in 1942. They were seized by the Soviets in Sept. 1944 and pressed as TKA-961 to 964. Two were returned in April 1945 but the remainder two were substituted by two TM-200 boats. Plagued by engine problems without spares they were immobilized until around 1960.

Bulgaria also possessed also a bunch of WW2 era (or older) patrol boats, maintained in service until 1952-55. Most were transferred by Soviet Union in April 1947. In all, this represented 18 ships.

- Belomorec, Chernomorec (ex-US C27, C80 of the SC 1916 type)

- Artillerist class: 281, 282

- MO-4 class: I-IV

- TK class: I-VI

- OD-200 class: I-VI

Cold war vessels

- Four ‘Whiskey’ class subs. 1960-61, extant 1990. See the page for more details;

- 7 transferred US-built Vosper type FAC/T in 1950, stricken 1965-69

- 12 ex-P4 FAC/T 1956-65, twin DsHK, radar in the 1970s, stricken 1987.

- 17 Huchwan type FAC/T hydrofoils: Transferred 1968-74, stricken 1889-93.

- 4 Hoku class FAC/M transferred 1976-77, stricken 1982-84

- 4 Kronstadt class Patrol Crafts, transferred 1958. Two extant 1995.

- 6 Shanghai II class patrol crafts transferred 1974-75, extant 1990.

- 2 former T43 ocean minesweepers acquired 1960, discarded 1990s

- 6 T301 inshore minesweeperss transferred 1960, reserve 1990s

- 3 KM4 minesweeping boats tranbsferred 1945, stricken 1967

- 11 PO2 minesweeping boats transferred 1957-60, stricken 1988-89.

Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia

After the Second World War Czechoslovakia, freed from Axis occupation mainly by the Red Army, was rebuilt within the pre-1938 boundaries (with the exception of Transcaucasian Ukraine which was incorporated into the Soviet Union) while her internal affairs were remodelled on the Soviet pattern.

As a result of attempts to introduce political reforms Czechoslovakia was invaded in 1968 by most of the Warsaw Pact countries to restore the Communist regime. From this time Soviet troops were permanentiy stationed in the country. Being landlocked, Czechosłovakia does not maintain a navy, but there is a river patrol force operated by 1200 Border Guard personnel wearing naval type uniforms. In 1990 this force consisted of about 18 armed launches.

Following the overthrow of the Communist regime at the end of 1989 and the break-up of the Warsaw Pact, Czechoslovakia successfully negotiated the withdrawal of Soviet troops by mid-1991. In December 1991 the country became an associate member of the ropean Community and applied to become a member of NATO. On 1st January 1993, following a referendum, the country was divided into the Czech Republic and Slovakia, It is believed that the Czech Republic has retained control of the river force.

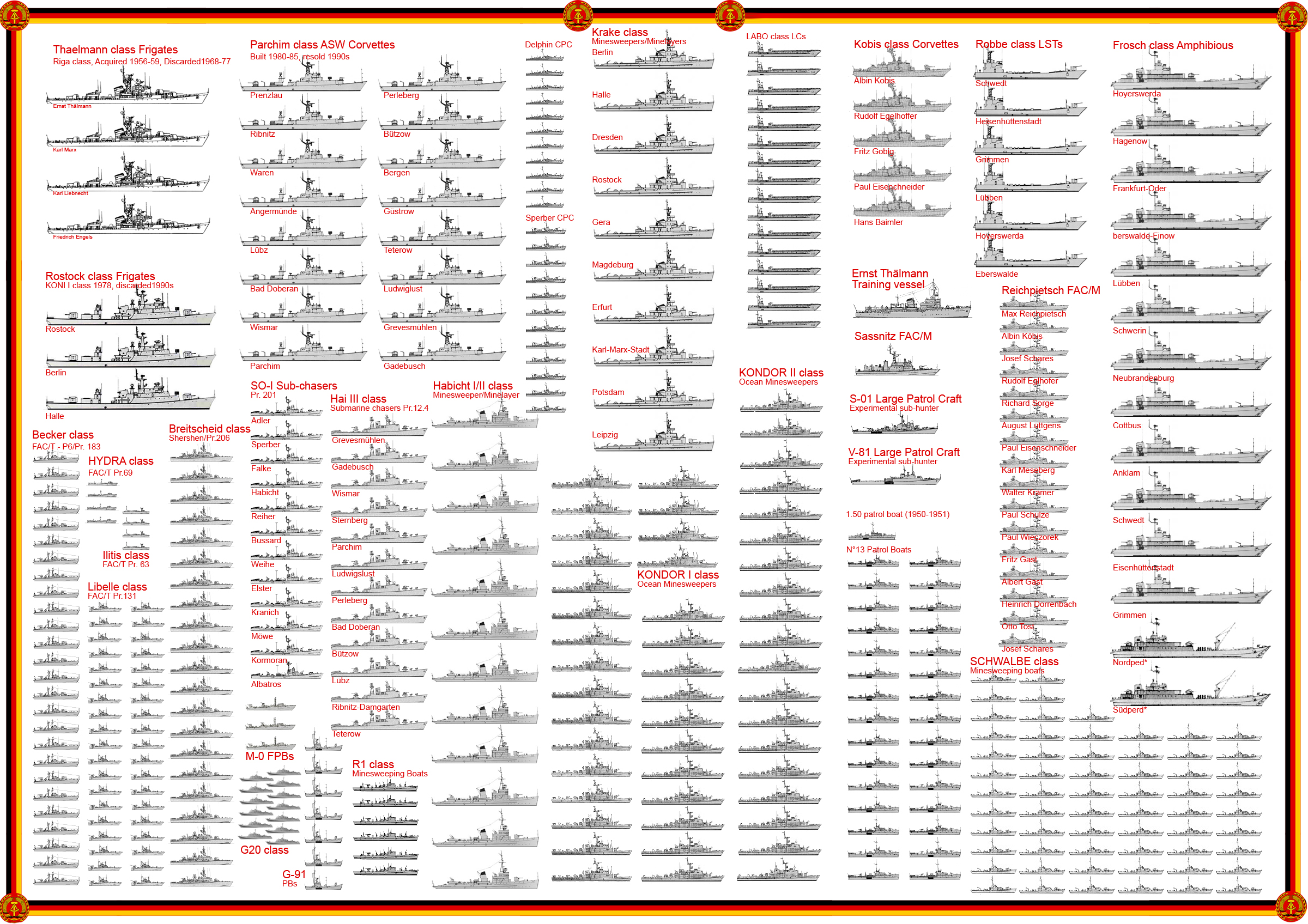

East Germany

East Germany

Poster showing the extent of the East German Navy in the cold war.

Far less known than the Bundesmarine, the German Democratic Republic’s Navy, or “Volksmarine” was far less impressive. It still had frigates, corvettes, landing ships, fast attack crafts, sub-chasers, coastal patrol craft, and minesweepers. On this part of the eastern Baltic, the Volskmarine presented a sizeable threat to NATO, with a capable industry which delivered in the 1970-80s most of its assets and a large degree of autonomy in its organization, structure and procurement, although sensors and armaments were standardized and delivered by the Soviet Union. Minesweepers were designed and built at Pennewerft. Sub-Chasers and patrol crafts also, as well as its Fast Attack Craft (Torpedo) vessels and most importantly, a large construction program of corvettes, the Parchim class. They were large and capable ASW vessels, with a recoignized quality that made them a prime example of Warsaw-pact vessel exported to USSR, a quite unique case there.

Fundamentally, the Volksmarine was a defensive, green water navy which role was to deter any access to the eastern Baltic by western powers. Both for economical reasons and political ones, within the strict frame of the Warsaw pact, there was at no point an extension plan to a blue water navy and after the fall of USSR and German reunification, its assets were all sold or discarded to adopt the Bundesmarine standards.

Koni class Rostock class Frigate, the largest Volksmarine combat vessels.

The Soviet East-German buuilt Corvette Kazanets in 1990 (Parchim class)

German built Maltese Mal P30, ex-Ueckermünde G411 submarine chaser.

Bad Doberan, German-built FAC/T

Libelle class German experimental FAC/T

Full list

- 4 Thälmann class Frigates (Riga class) 1956-59 discarded 1968-69

- 3 Rostock class Frigates (Koni I type) 1978, discarded 1990s

- 16 Parchim class Corvettes (1980s, resold 1990s)*

- 5 Kobis class (Tarantul I) missile corvettes (1984-85)

- 12 Labo class LSCs (1960)*

- 6 Robbe class LSTs (1964)*

- 14 Frosch class LSTs (1976)*

- 38 Iltis class FAC/T (1958)*

- 28 P6 type FAC/T (transferred 1957-58)

- 60 Hydra class FAC/T Project 68* (1959)

- 16 Max Reichpietsch class (OSA I) FAC(M) (1962)

- 18 Shershen Type FAC/T (transferred 1969-70)

- 2 Forelle class FAC(M) (1982)* experimental boats

- 5 ‘Balcom 10’ FAC/M Project 151* (1990)

- 2 former Danish Kvintus class minesweepers (acquired 1950)

- 12 Habicht I/II class MWVs* (1953)

- 10 Krake class MWVs* (1957)

- 20 Kondor I class Coastal minesweepers* (1970)

- 30 Kondor II class Coastal minesweepers* (1971)

- 48 Schwalbe class minesweeping boats* (1952)

- 11 SO-I type sub-chasers transf. 1959-60

- 1 Hai I experimental sub-chaser (Project 12.1)*

- 1 Hai II experimental sub-chaser (Project 12.3)*

- 13 Hai III class sub-chasers (Project 12.4)*

- 26 Sperber I/II class Coastal Patrol Boats* (1966)

- 12 Sperber class Coastal Patrol Boats* (1953)

- 12 Tummler I/II class Coastal Patrol Boats* (1954)

- 7 SAS class Coastal Patrol Boats* (1948)

- 10 Bremse class Coastal Patrol Boats* (1948)

- Ernst Thälmann (1955) training vessel (ex-Danish)

Note: starred ships were built in East Germany, mostly Peenewerft, Wolgast.

Hungary

Hungary

Riverine Minesweeper MSB-268 in the 1970s credits

The armistice signed in January 1945 in Moscow ordered the return of territories seized during 1938-40, 300 million dollars reparations and access to the country’s territory by units of the Soviet Army.

Hungary was proclaimed a republic in 1946 and in 1947 the communists seized power in the country following the disbanding of the Allied armistice commissions after signing the peace treaty in the same year.

Internal affairs were modelled on the Soviet pattern and in 1955 the country became a member of the Warsaw Pact. In 1956 the Hungarian Revolution forced the government to establish a multi-party system and to announce on 1 November withdrawal from the Warsaw Pact. This resulted in Soviet invasion and a permanent Soviet presence which went unopposed by Western powers at the time. The political reforms were abolished but thorough economic reform now became possible and the country became the most prosperous of the COMECON states.

Being a landlocked country after the First World War, Hungary maintained a flotilla on the Danube which had been totally annihilated by the closing stages of the Second World War. Reconstruction of the Danube Flotilla was started in 1948 with the transfer of ex-Soviet river minesweepers. Then eight old craft (the four Kecskemet class 133t ships were stricken in the 1950s, Baja in 1969, and the 140t Sopron of 1918 also in the 1950s, as were the three Honved class 17t minesweeping boats of 1916) from the Austro-Hungarian Danube Flotilla were restored.

Since the mid-1950s they have been replaced either by reconstructed ships of the inter-war period or by new construction. In 1969, it was officially stated that the flotilla had been disbanded; however, the country continues to operate an independent maritime brigade (400 officers and men; ratings on one and half years service) of the army, and older patrol craft have been gradually disposed of and replaced by Yugoslav-built river minesweepers.

About 13 craft were in active service in 1990, and others were in reserve. Several auxiliaries are operated, including troop transports up to 1000t, two transport barges which can be used as LCTS, and five LCUS. Hungary, which together with Poland led the wave of political reform in eastern Europe, successfully pressed for the disbanding of the Warsaw Pact and was able to negotiate withdrawal of Soviet troops from its territory. In December 1991 Hungary became an associate menber of the European Community and has applied for membership of NATO.

Details of the flotilla

MSB-22 in 1990, src navypedia

AN-1 boats in the 1970s, src navypedia

- PN11 river patrol boat: Built in Budapest 1944 as PN3, scuttled winter 1945, raised and repaired 1948, rebuilt with 30 mm casemate added, renamed Pn 31, 34, stricken 1973. 87 tons, 33.2 x 3.9x x 1.1 m, 2 shafts LANG MP-35 DIESELS 420 hp 13.5 kts, 2x 37mm, 85 mm howitzer, 30 mm armour.

- PN21 type river patrol boats: Two 52 tons boats, former Danube flotilla raised 1948, repaired, entered service as Pn 21, 22, with 30 mm casemate added. PN 22 lenghtened, 74 tons. Stricken 1973.

- PN 31 class Rover patrol boats: Three 92 tons, 33 x 4.8 x 1m boats, with 2 shafts Endraeck diesels 900 bhp 13.4 kts, 2x 37mm, 1x 12.7mm DshK., scrapped 1973

- Nestin class riverine minesweepers (1979-80): Ex-Yugoslavian Újpest, Baja, Szazhalombatta, Óbuda, Dunaúváros, Dunaföldvar + two reserve unnamed ships acquired 1979-80 and still extant in the 1990s. 61/78 tons, 26.9 x 6.5 x 1m, 2 Torp B539 RM/2 diesels 520 shp, 15 kts, 864 nm, quad 20mm M75 AA, 2x 20 mmAA, 12-24 mines PEAM acoustic/magneti and MDL1 mechanical gear.

- Wooden motor minesweepers: 12, ex Soviet, transferred July 1948, stricken 1960s.

- AN-2 Type MSB Patrol Crafts: These 10.5 tons, 13.4×3.8×0.6m aluminium boats were built in WW2 for Lake Balaton operations. Two were refloated in 1948 and rebuilt with new superstructures. Construction of 45 clones started in 1953, N°542-001 542-053, still in service 1990.

Poland

Poland

ORP Warsawa of the Kotlin SAM II type

The Polish Navy was re-established between 1945 and 1948 with the destroyer Byskainca, three submarines, four minesweepers, two minesweepers acquired in Britain and nine minesweepers, twelve

patrol craft and a sail training ship (all of Polish origin), three BYMS type minessweepers from Britain, twelve Submarine chasers and two MTBS from the Sovier Union in lieu of war reparations from the Knegmarine. The units thus asembled were insufficient for the detence of over 500km of coastline, and in 1947 a Naval Estimate was prepared for the construction of a 42,000 ton fleet (eighteen submarines, twenty-four MTBS, nine escorts, forty-four patrol craft, sixty-six minesweepers), over 20 years.

This programme reflected adoption of the Soviet naval doctrine of that timne, which confined the navy to covering the flanks of large land armies with extensive use of minefields guarded by constal artillery while attack on enemy communications would be executed by small combatant and naval aviation. The 1947 estimate evidently exceeded what was possible from a war-shattered economy and was substituted by a 1950-55 plan for construction of five MTBS, five patrol craft, five minesweepers and five minesweeping boats.

This plan was abiandoned in 1950 by the Soviet officers in command, who saw the Polish Navy as a local detachment of the Soviet Baltic Fleet. In 1951 the ‘Plan for Reinforcing Defences’ was authorized, as a modernisation of the army, air force and AA defence. The navy’s role was confined to the defence of the main base at Gdynia, and further development was restricted to the placing in service of suitable ships. As a temporary measure, a landing craft flotilla was formed. It comprised former German and US boats, and the ageing destroyer Burra was modemised. The necessity of replacing ageing naval craft

was only acknowledged four years later in the ‘Military Development Plan for 1955-60’, which proposed increasing the navy to five destroyers, nine frigates, twelve submarines and ninety-six MTBs (all to be imported from the Soviet Union), in addition to sixty minesweepers and eight submarine chasers built locally.

This enforced rearmament programme brought about a sharp decline in the national economy, the first sign of which was an acute food shortage in 1952. However, only the easing of tension, both internationaly (Geneva conference of July 1955) and internally after the 1956 riots in Poznan made it possible to halt the Soviet program. This resulted in the wihdrawal of certain command posts and the return of Polish Military Uniforms. The military expansion program was halted, but at that point, the navy had already purchased two Skoriy class destroyers, six ‘MV’ type submarines, twenty-seven fast craft, while twelve ‘T43’ type and seven ‘TR40’ type minesweepers were to be built locally under Soviet licence.

The Khrushchev regime forced Poland to adopt a new armament programme approved in March 1961, which provided within a period of seven years, a destroyer flotilla of three ships, a missile boat flotilla of seven boats, a submarine brigade of seven boats, an MTB brigate of nineteen, and a sub-chaser flotolla of eight boats, plus a minesweweepers flotilla of twenty-four, a riverine flotilla of seven boats, plus a landing brigade of twenty-eight ships.

The Polish Navy had to undertake the construction of the minesweepers, sub-chasers, MTBs, landing ships and auxiliaries, like East Germany. The desired force at least on paper was only achieved in the late 1960s, but numerous earlier vessels already needed a replacement. The declined of Polish planned economy, burdened with excessive military expenditures and lack of modern technology led to social unrest in December 1970. The ailing economy caused delays in replacement and was made only worse by the attitude of the Polish ministry of defence, emphasised a stronger development for better integration nto the Warsaw Pact strategic planning.

Therefore the basic combat potential planned for the Polish Navy in 1961 was never reached, and at the end development of the decade the Polish Navy only comprised a single ‘Kotlin SAM’ guided missile destroyer, four “Whiskey V’ class submarines, 50 small surface combatants, 33 landing ships and 24 to be imported from the Soviet Union, but the naval aviation division had not been modermised. Thus the Polish Navy, which had been the largest of the non-Soviet naval forces lost its position to East Germany in the early 1980s.

The 1980 program focused on locally-built small surface combatants, FACs, MCVs and assault craft, equipped with Soviet armaments and sensors, but its development was plagues by strikes, notably at Gdansk and Gdinya. Therefore after the withdrawul of the 30 years old destroyer Warsawa in 1986, the Poles were unable to contribute to the Warsaw Pact joint Baltic squadron until the arrival of the “Kashin mod” misile destroyer was lend by USSR in 1988. Construction of FAC/M only started with difficulties by 1988, in coperation with East Germany, und only the landing craft program wa pursued nore vigorously, even though only five Lublin class have been completed.

ORP Poznan of the Lublin class LSTs

ORP Warsaw (iii) of the Kashin Mod class in 2004

ORP Wilk of the Foxtrot type

ORP Orzeł of the Whiiskey class (cutaway)

Pilica class patrol crafts

ORP mewa of the Krogulec class minesweepers

ORP Kaszub corvette in Gdynia

Missile Corvette ORP Metalowiec in Gdynia (Tarantul class)

ORP Grom, Orkan class Missile corvettes

Additional purchases from the Soviet Union proved a considerable strain on the economy, but included four “Tarantul class” corvettes FAC/M replacing the old OSA I boats. Noteworthy was the transfer of

the submarine Orzel in 1986 (sole Kilo class), and the smaller and cheaper Foxtrot class followed, with the Wilk and Wicher.

Following economic restraints brought about as a result of this program, the Polish economy once again showed sign of crisis. Hardship suffered by the people caused much social unrest in the summer of 1988, and the Communist Party, discouraged by Moscow’s unwillingness to compromise its new image by supporting an unpopular regime, decided to negotiate with leaders of the hitherto illegal opposition. This resulted in the peaceful removal of communist rule after elections in June 1989, and triggered a similar process in neighbouring countries.

Poland was the first country to join the ‘Partnership for Peace’ programme, and the most eager to join NATO, making the best possible use of the time given by the temporary weakness of the Russian Empire. An estimate to create a balanced and independent naval force was drawn up, and provided for five submarines, twelve ASW escorts, eighteen FACs, twenty MCVS and a naval aviation of eighty aircraft. This programme was however still well beyond the capacity of the Polish economy, driving forcefully from the centralised system to the open market.

The Polish Navy in 1995 comprised on paper at least, three submarines, a single missile destroyer, a surface escort, thirteen TACM, nineteen sub-chasers, twenty-four mineweepers and the landing ships. However most of these ships were without practical military value eiher because of obsolescence or lack of modern weapon systems, not even talking about NATO standards total incompatibility. The only units pratical value came from the single Kilo class submarine, the four Tarantul class corvettes, the five landing ships, the sixteen MCVS.

The Coast Guard was separated from the navy in 1991. The tleet headquarters are at Gdynia, and bases were at Gdynia Oksywie, Hel, Swinoujscie and Kolobraeg. Naval aviation comprised by then the 34th Fighter Wing (at Gdynia Babie Doly) 38 MIG-21 fighters, 4 TS-11 Iskra training aircraft, two AN-2 transport planes and two Mi-2 ‘Hoplite’ helicopters, and the 7th Training Wing irowice with fifteeri TS-11, eight An-2 and two An-28 bombers, an Helicopter Squadron at Darlowo, with fourteen Mi-14 ‘Haze’ and Mi-2 ‘Hoplite’, the 18th Despatch and Rescue Squadron with four RW Anakonda, three W-3 Sokol, ten Mi-2 helicopters and two An-28.

WW2 legacy ships

ORP Blyskawica, modernized 1949-50 and 1957-61, Polish flagship until the late 1960s

- -Destroyer Burza (Wicher class 1929), BU 1977

- -Destroyer Blyskawica (Grom class 1936), preserved 1976

- 3 Wilk class subs (Rys, Wilk, Zbik) BU 1952-54

- -Sep (Orzel class 1938), stricken 1969

- 4 Jakoslka class minesweepers, stricken 1970

- 9 Transferred T371 boat, stricken 1959

- 2 D3 class MTBs stricken 1959

- 11 OD-200 sub chasers, stricken 1959

- 6 misc. ships stricken 1957-1961

- 6 former German MFP landing ships, stricken 1957-1963

- 1 former Italian MS landing ship acq. 1950, BDD 4, ODD 4, stricken 1963

- 11 LCT-5 acq. 1950, stricken 1957-60

- 3 LCM-3 acq. 1950, stricken 1960s

- 4 YMS type minesweepers purchased 1948, stricken 1955-57

The Polish cold war fleet

ORP Wicher of the Skoryy type

- 2 Grom class destroyers (Skoryy class) 1957, stricken 1967

- -Warsawa Kotlin SAM acq.1970, stricken 1986

- -Warsawa Kotlin Mod acq.1988, discarded 2000s

- -Kaszub Corvette (Balcom 6) 1986, extant

- -6 MV class subs (1948-52), delivered 1954, stricken 1970

- -4 Whiskey class subs (transferred 1962-69), stricken 1990

- -Orzel (Kilo class) acquired 1986, extant

- -Wilk class (Foxtrot) acquired 1987-88, extant

- 11 Gdynia class landing ships (Polocny A) 1965-68, discarded 1990s

- 11 Lenino class landing ships (Polocny B) 1968-71, discarded 1990s

- 5 Lublin class LSTs (Balcom 11) 1989-92, extant.

- Command ship Grunwald (Polocny C) 1972 (+27 exported)

- 15 Eichstaden class LCs (LCP(L) type 1962, stricken 1990s

- 4 Marabut class LCs 1973 stricken 1987

- 3 Deba class LCs (1987), extant

- 20 ‘P6’ type FAC(T) (1956) discarded 1970s-80s

- 12 OSA I type FAC(M) 1963-69, discarded 1990s

- -Blyskawiczny experimental FAC(T) 1958, discarded 1970s

- 8 Bitny class FAC(T) (NATO Wisla) 1962, discarded 1984

- -Project 665 FAC(M) 1977, construction abandoned.

- 4 Tarantul class missile corvettes delivered 1983-89

- 3 Orkan class FAC(M) (Balcom 10) 1990s

- -Sub-chaser Bitny 1952, experimental.

- 8 Kronstadt class sub chasers (delivered 1955-57), stricken 1969-72

- 2 Oksywie class large patrol craft (Op 201 type) 1957, stricken 1980

- 9 Gdansk Large Patrol Crafts (1959), discarded 1980s

- 13 LPC/SC (1965-72) extant 1990s

- 2 Kaper class patrol craft (SKS 40 type) built 1991

- 20 Pilica class PC/SC 1971-74/1973-83, extant

- 7 KP 100 class inland patrol boats (1953-54), stricken 1970s

- 11 Wiloska class coastal patrol craft (1970s), extant 1990s

- 12 T43 licence bult minesweepers 1955-62, stricken 1987-93

- 12 Krogulec class minesweepers 1962-67, stricken 1990s

- 13 GRP hull Goplo class minesweepers 1981-85, extant

- 4 Mamry class (improved Goplo) 1990s

- 2 Leniwka class experimental coastal mineswpeers 1984

- 7 ‘TR40’ type river minesweepers 1954-56, stricken 1969-70

- 33 ‘K8’ type minesweeping boats 1956-60, stricken 1986

Romania

Romania

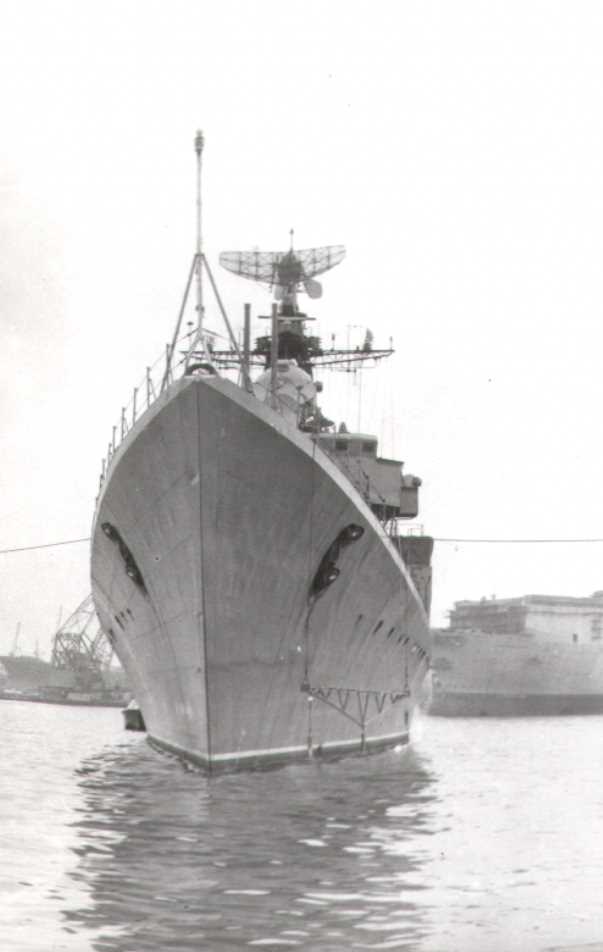

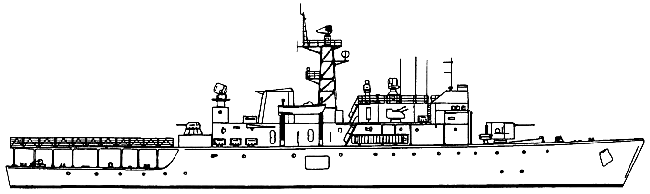

The missile destroyer Mărășești (1982), late cold war navy flagship, now replaced by the Regele Ferdinand frigate, British Type 22 type (one more). Mărășești has been reclassified as a frigate.

Post-WW2 situation

Although Romania changed to the Allied side in the closing stages of the Second World War, this did not excuse the country from postwar restrictions placed upon her by the USSR.

The peace treaty of 10 February 1947 required a reduction of the Romanian Army to 120,000 men, the Air Force to 150 aircraft while the Navy was allowed to maintain 15,000t overall tonnage. At the time that tonnage was barely reached as the Romanians operated two old destroyers, one submarine, two escorts converted from the old torpedo-boats, two old gunboats and five MTBS returned by the Soviets.

This force was supplemented by more modern units returned by the Soviet Union by the early 1950s namely two destroyers, two submarines and a minelayer. At that time the Romanians began the river craft programme which resulted in the completion of nineteen such craft for service on the Danube. During the late 1940s and carly ’50s the country was remodelled on the Soviet pattern, a process which had started in September 1944 due to the presence of Soviet troops. The increasing dominance of the local communists, backed by Soviet military power, forced King Michail I to abdicate in 1947, and this ended any likelihood of organised opposition.

In 1948 the Communist Party took absolute power and enforced radical collectivisation and industrialisation programmes (1949-62). Romania’s membership of the Warsaw Pact improved her navy’s situation but not to the same extent as with neighbouring Bulgaria. Four ‘MV’ type coastal submarines, four ex-German M-boats (1940 type), three ‘Kronstadt’ class patrol craft and twenty-one T 301 class inshore minesweepers were acquired from the Soviet Union during the late 1950s. In addition eight incomplete hulls of the TR 40′ type river minesweepers were transferred from Poland for completion in Romania and twelve landing craft were laid down in a local yard.

The Cold War Romanian fleet in 1947

- 2 Marasti class destroyers (1917), stricken 1955

- 2 Regele Ferdinand class destroyers (1929), seized 1944, returned 1951, stricken 1959

- 3 submarines of the Delfinul class (1930), stricken 1957-59*

- 2 Escorts Sborul, Naluca (1914) stricken 1960

- 2 Capt. Dumitrescu class Gunboats (1916), stricken 1990s

- 1 Vosper, 4 Vantul class MTBs discarded 1950

- 3 Capt. Lascar Bogdan class river patrol vessels (1906), discarded 1950

- 5 Ardeal class river monitor (1900), sized 1944, retroceded 1951, discarded 1959-60

*Apart Delfinul available in 1947, Requinul was in soviet service after capture in 1944 as TS-1, returned in 1951, discarded c1958. Marsuinul was also seized as TS-2, sunk in 1945, raised, repaired and recommissioned but stricken 1950.

The Romanian Navy of the 1960s

In June 1958 Soviet forces left the country. The early 1960s saw slow but steady development as twelve ‘P4′ type MTBS were transferred from the Soviet Union and transfer of the “Osa’ class missile boats was started. Further transfer of Soviet warships was interrupted suddenly in 1964 when Romania refused to follow the Soviet Union’s example in relations with Red China or accept COMECON plans for economic development. This rift was widened when Romania took an independent line in her trade relations and refused to participate in the invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968.

Such disobedience resulted in a considerable reduction of Soviet supplies and left the Romanian Navy, except for three ‘Poti” class corvettes, acquired in 1970, with only five modern cormbar naval craft (Osa’ class) in service at the beginning of the 1970s. Therefore Chinese assistance was willingly invited and licence was bought for construction of torpedo hydrofoils of the ‘Huchwan’ class and patrol craft of the ‘Shanghai’ class. Over twenty-five craft of the former and thirty of the latter type were commissioned during the later 1970s. Apart from these boats the Romanians themselves began construction of three types of river craft.

Romania’s somewhat divergent foreign policy was sufficient to satisfy Bucharest’s ambitions for independence without provoking open conflict with the Kremlin. This in turn allowed President Ceaucescu the political freedom for an unparalleled concentration of power into his own hands and the pursuit of a series of major projects, increasingly erratic in conception and increasingly at odds with the capacity of the Romanian economy to support them. Among these was a most spectacular naval expansion programme undertaken in the early 1980s.

The unrealistic 1980s program

A huge fleet (compared with the country’s resources) of missile destroyers (officially classed as battlecruisers), four frigates, twelve torpedo craft and two large auxiliaries were to be built domestically, The first submarine, after a 25-year absence of this type in the Romanian Navy, was purchased in 1986 from the Soviet Union. The results, however, were far from satisfactory. The major surface ships were too large for coastal defence and it was hard to conceive of their use in other waters. Moreover, they were of rather rudimentary design, fitted with outdated weapons and sensors purchased from the Soviet Union.

The ASW forces were inadequate as were the MCM capabilities, amphibious capacity was negligible and the auxiliaries were too small. Construction of such a large fleet, together with other large auxiliaries were to be built domestically, The first submarine, after a 25-year absence of this type in the Romanian Navy, was purchased in 1986 from the Soviet Union. The results, however, were far from satisfactory. The major surface ships were too large for coastal defence and it was hard to conceive of their use in other waters.

Moreover, they were of rather rudimentary design, fitted with outdated weapons and sensors purchased from the Soviet Union. The ASW forces were inadequate as were the MCM capabilities, amphibious capacity was negligible and the auxiliaries were too small. Construction of such a large fleet, together with other grandiose projects, was attained at a cost unequalled elsewhere in Europe, and this was at a time of declining living standards, decapitalisation of machinery and devastation of the environment.

‘Cosar class’ minelayer NMS Ian Murgescu

Despite strenuous sacrifices imposed on the Romanian people, most of the extravagant programmes had to be postponed due to the collapse of the economy. Naval shipbuilding was stopped in 1987, and since then no new shipsor craft have been laid down. At the end of the 1980s Romania possessed quite a large fleet by eastern European standards, but this force had ‘operetta and parade ground’ value rather than true operational worth. The increasing hardship and repression suffered by the Romanian people led in 1989 to an unprecedented level of unrest, and news of events in other eastern European countries sparked a popular revolt, which was at least partly orchestrated by the army and the Communist Party and resulted in the execution of President Ceaucescu.

The Fall

Partial disintegration of the apparatus of the state and of the Communist Party itself, combined with the continuing struggle of non-communist political groups for power, accelerated the collapse of the economy. Following the break-up of the Warsaw Pact, Romania has pursued a policy of seeking membership of NATO and associate membership of the European Community. The Romanian navy has a total of 10,000 men, of whom 3400 are afloat, 2000 are in coastal defence (one SSC26 ‘Samlet missile battalion and gun batteries totalling one hundred 130mm and oin pieces, as well as radar stations along the coast) and 100 personnel in naval aviation.

The Romanian Navy in the 1990s

Ratings are on 15-months’ conscription. The fleet headquarters are at Mangalia, and the main bases are at Mangalia and Constanța. The Danube River Flotilla has headquarters at Giurhiu and has bases at Giurhiu, Sulina, Galati and Dulcea. The naval aviation division, which was established in 1983, has its headquarters and base at Constanța and consists of six Mil4 Haze’ land-based and six license-built French designed IAR-316 ‘Alouette III’ shipborne helicopters. Because of lack of oil fuel some of the larger warships have been non-operational since 1990.

Amiral Petre Barbuneanu, corvette of Tetal I class

Contraamiral Eustatiu Sebastian, a Corvette of the ‘Tetal-II’ class

River Patrol Crafts of the VD class

Romanian river monitor F-46 Ion C Bratianu.

Cold War vessels in 1947-90

- Missile destroyer Muntenia (1985), extant

- 4 Tetal class frigates (1981), extant

- 2 Tetal II class frigates (1988) extant*

- 4 M V class coastal submarine transferred 1957, stricken 1967

- Delfinul (Kilo class acquired Dec. 1986), extant

- 12 Braila class LCU c1955, stricken 1983-90

- 3 Poti type ASW corvettes (Critsecu class) 1970, stricken 1990s

- 12 ‘P4’ class FAC(T) 1962, stricken 1987

- 6 OSA I class FAC(M) 1964, stricken 1990s

- 26 Huchwan class Torpedo Hydrofoils** (1970s-80s), extant

- 12 Epitrop class FAC(T)*** 1979-82

- 3 Tarantul I class FAC(M) 1990

- 3 Kronstadt class LPC (purchased 1956), stricken 1990s

- 14 Shanghai II type LCP (purchased 1970s-80), extant

- 6 Brutar class river monitors (1986), extant

- 7 VG class patrol crafts (1988-92)

- 17 VB class patrol crafts (1973-85)

- 12 SM class patrol boats (1954-56) stricken 1989-95

- 5 SD class patrol boats (1972), stricken 1990

- O.23E experimental hovercraft (1987)

- 2 Cosar class minelayers (1980)

- 4 M40 type coastal minesweepers (1951), rebuilt 1976-83, extant 1995

- 4 Musca class minesweepers (1987-89)

- 27 ‘T301’ type minesweepers acquired 1955-60, stricken late 1980s apart those modernized

- 8 ‘TR40’ type river minesweepers purchased Poland, completed 1960, stricken 1983-85

- 24 VD 141 minesweeping launches 1976-84, extant.

*Now called as the “Admiral Petre Bărbuneanu class corvettes” and “Rear-Admiral Eustațiu Sebastian-class corvettes”, Tetal I/II class was their NATO designation.

**First six imported friom China, the rest built locally at Mangalia shipyards in two batches in 1974-83 (15), 1988-90 (5), 2 as diving tenders.

***Mangalia-built of OSA-I with torpedoes

Read More/Src

Links

worldnavalships.com – Polish Navy

NATO and Warsaw Pact: Force Comparisons

The Warsaw Pact: Changes in Structure And Functions, Ivan Volgyes

The role of East European Warsaw Pact Forces in Soviet military planning (pdf)

Soviet Military doctrine & Warsaw Pact Exercizes (pdf)

The Role of East European Warsaw Pact Forces in Soviet (PDF)

Soviet and Joint Warsaw Pact Exercises: FUNCTIONS AND UTILITY, JOHN M. CARAVELLI

SOVIET STRATEGY AND NATO’S NORTHERN FLANK, William K. Sullivan Naval War College Review 1979

insidethecoldwar.org NATO & Navies of the Warsaw Pact 1982 PDF

The navies of the NATO opposition Warsaw Pact Baltic Fleet

The Romanian Navy on globalsecurity.org

Military Balance 2010 tandfonline.com

navy.ro romanian naval forces historical background

Natalia Jackowska, The Border controversy Between The Polish People’s reoublic and the German democratric republic in the pomeranian bay

polska1918-89.pl: History of the Polish Navy until 1989

relikte.com

www.polish-navy.org

On www.mon.gov.pl pdf

baltmilitary.amberexpo.pl

altair.com.pl

isap.sejm.gov.pl Doc Polish Navy modernization

Warsaw Pact (refresher)

Video: The Rise Of The Soviet Navy (1969)

Books

Nelcarz, Bartolomiej & Peczkowski, Robert (2001). White Eagles: The Aircraft, Men and Operations of the Polish Air Force 1918–1939. Hikoki Publications

Peszke, Michael Alfred, Poland’s Navy: 1918–1945, New York, Hippocrene Books, 1999

Siegfried Breyer, Peter Joachim Lapp: Die Volksmarine der DDR, Bernard & Graefe Verlag

Robert Rosentreter: Im Seegang der Zeit, Vier Jahrzehnte Volksmarine, Ingo Koch Verlag

Klaus Froh, Rüdiger Wenzke: Die Generale und Admirale der NVA. Ein biographisches Handbuch.

Arrangement concerning the carrying of flags, pennants and standards on ships and boats of the People’s Navy

Axworthy, Mark; Scafeș, Cornel; Crăciunoiu, Cristian (1995). Third Axis. Fourth Ally. Romanian Armed Forces in the European War, 1941–1945

Halpern, Paul G. (1995). A naval history of World War I. Routledge.

Zaloga, Steven (1985). Soviet Bloc Elite Forces. Osprey Publishing.

Videos

Scenario of a fight between NATO and WaPac Navies 1985, Binkov’s battlegrounds

SOVIET SEA POWER TODAY COLD WAR ERA RUSSIAN NAVY CAPABILITIES 80434

Launch of “Oceans Ventured: Winning the Cold War at Sea”

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign