Spanish Armada vs

Spanish Armada vs  US Navy

US Navy

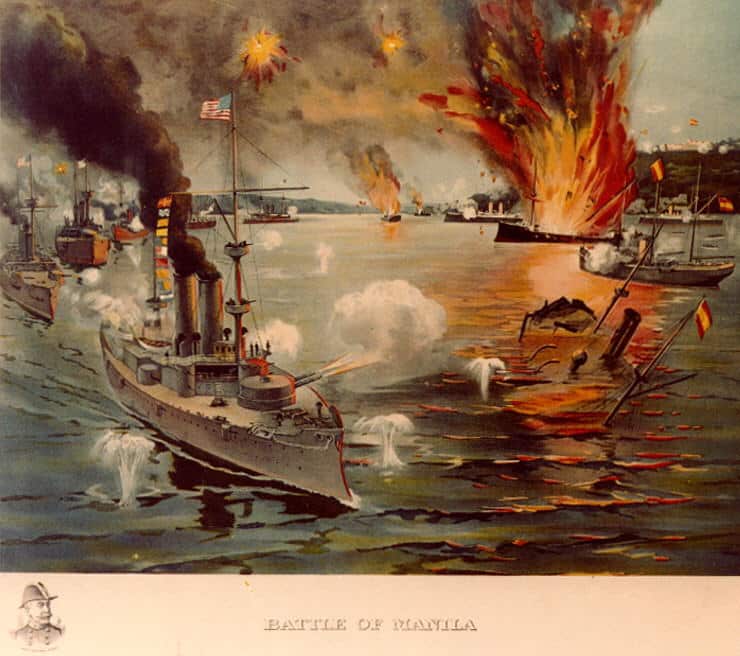

Map of Manila’s battle actions (public domain)

Swapping an Empire for Another

The origins

The war of 1898 which emerged from the question of the independence of Cuba from Spanish so-perceived tyrannic colonial rule, was resolved rapidly through two naval battles. Strangely the first one did not occurred in the Caribbeans, but far away in Asia, in the maze of tropical islands called the Philippines. Thus remote possession of the Spanish Empire was all that left from its former Empire there since 1565, but still, a vital trade and materials provider (notably rubber), which was defended by a squadron while the capital Manila was well protected by a chain of forts all along the bay, easy to close and defend. The American attack came as a surprise (the local forces were not prepared, neither to the ferocity of the assault, nor to fight in any way).

USS Olympia, Commodore Dewey’s flagship at the battle. It has been preserved and can be visited in the Independence Seaport Museum, Penn’s Landing, Philadelphia. Illustration by the author.

The battle and its consequences

It was called soon a “splendid example of a splendid naval action” with tremendous consequences. For Spain, the fall of its Asian operating base (soon Guam followed) and the beginning of the end, confirmed at Cuba in July, which precipitated the end of the war. It proved that despite falling to near oblivion after the civil war, the American Navy was no longer a Joke for European powers. It changed the lives of all Filipino, that much like their Cuban counterparts, lived under a harsh colonial regime and developed resistance movements. First perceived like liberators, the new power however settled in a quasi-colonialist fashion, going as far as ordering fierce repressions leaving the impression to the locals of having swapped an imperialist power for another.

Dewey on the lookout post of the USS Olympia, a painting now at Vermont State.

The Battle of Manila was mainly a surprise attack by a U.S. Navy squadron on the Spanish Pacific Squadron anchored at Manila Bay. Complete destruction of the fleet prevented any reinforcements to Cuba and offered the United States a brand new platform in Asia for future expansions and its fleet support in this area. The victory was all the more dazzling for the Navy, its realization was daring, hazardous and risky, ended with no casualties but minor injuries, a feat rarely achieved for the scale of such battle. The strong impression it left, conducted the Japanese to apply the very same tactic at Port Arthur against the Russians some seven years later. This surprise attack and preventive strike would inaugurate a kind of action soon famous in warfare in general, in a sense prefiguring the blitzkrieg. Like Napoleon once stated, the “best defence is attack”. This success was largely celebrated and do well for the war nickname “the splendid little war” soon relayed by all the press, in the US and abroad.

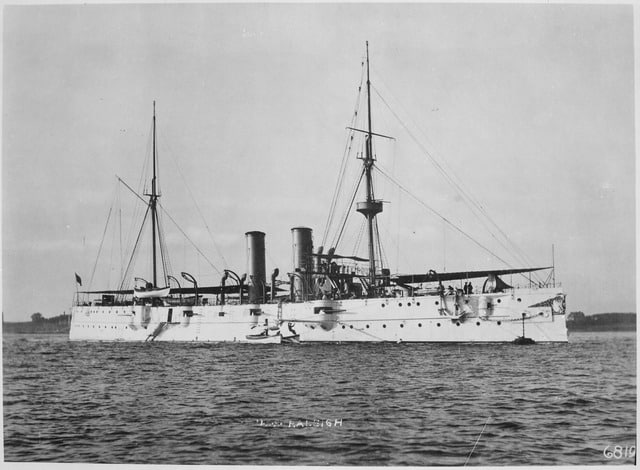

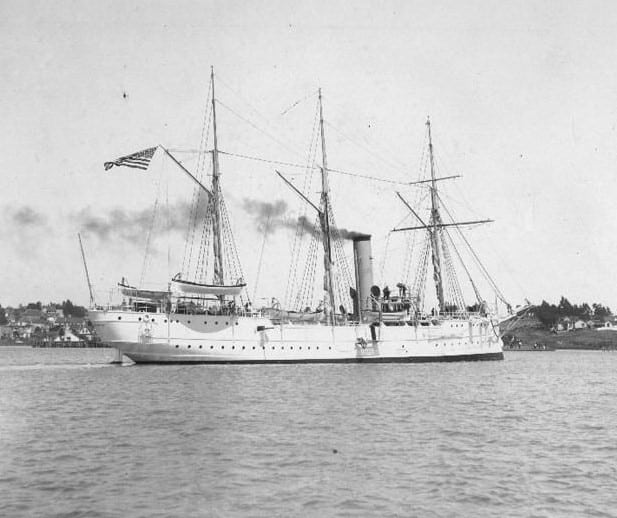

Cruiser USS Raleigh (C8) circa 1900

Commodore Dewey’s Pacific Squadron

It all started with the plans reviewed by the Admiralty in the event of confrontation with Spain, a few years ago. That’s when Commodore George Dewey, then based in Hong Kong, was appointed to head the U.S. Pacific fleet at the insistence of the personal assistant to the secretary at the Naval affairs of the White House, Theodore Roosevelt. His squadron was quite thin in Asia in terms of impact force, especially compared to the Spanish fleet, reinforced by many land-based coastal batteries. His squadron included the cruiser USS Olympia, USS Boston, gunboat USS Petrel and the very old steam paddle USS Monocacy. That was only a mere fraction of the US Navy at that time, which bulk was facing Cuba.

Gunboat USS Petrel, circa 1900

Intelligence of the Armada

In addition, knowledge of the Spanish forces in the sector was meager, based on assumption that the bulk of the fleet was anchored in Manila, which was confirmed later by the American consul there, Oscar. F. Williams. Lieutenant Upham (USS Olympia) was also there in civilian disguise, roaming in the capital of the Philippines to try to glean detailed information on ships in harbour and movements. Finally Dewey himself has his own personal sources, form an American businessman who went there regularly and also passed more valuable information.

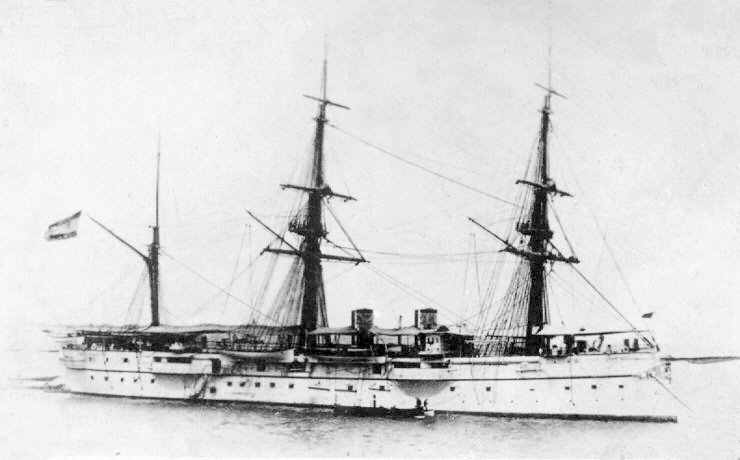

Spanish cruiser Castilla with full rigging in the 1880s.

State of Dewey’s squadron

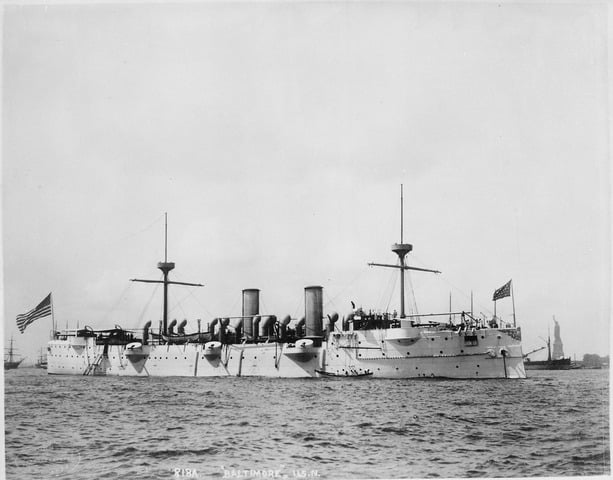

But the supply of ammunition (as well as coal quality) was a real problem for the US squadron. Dewey’s ships had, few days before the battle, not yet received a quarter of their shell stock. Supply ships were hard to find and charter, many companies and crews refused to take the risk. The cruiser USS Baltimore, dry-docked, has her hull cleaned and repainted in dark gray within 48 hours, a more suitable livery than the classic peacetime classic “black hull, white and canvas superstructures” for naval operations. However, reinforcements arrived on the eve of the battle, with some equipment for the fleet and ammunition to complete inventories (40% Empty), accompanied by the cruiser USS Raleigh and a Customs patrol boat, the USS MacCulloch. Still later after the departure of the squadron, the gunboat USS Concord joined the group. Other depot ships were also collected for the purposes of last-minute supplies. At the outbreak of war, the squadron has coaled after many difficulties, but was now ready to depart, and morale was very high.

USS Baltimore (C3) starboard bow view in 1891. Notice the reduced military masts.

State of the Armada in Manila

Meanwhile the local Spanish pacific fleet was managed by Admiral Don Patricio y Montojo Pasaron, whose fleet included the cruisers Don Antonio de Ulloa, Don Juan de Austria, Reina Cristina, Castilla, Isla de Cuba, Isla de Luzon, and the gunboat Marques del Duero. Stationed at Manila Bay, they were deployed in front of Subic Bay, which defenses has been considerably reinforced after the outbreak of war. At the last minute, spare battery from the old gunboats Don Antonio and General Lezo were placed on coastal fortifications, as well as the guns of the cruiser Velasco. Castilla was also in such bad condition that its 150 mm (6 in) guns were landed, but left shortly before the attack on the beach instead of being swiftly mounted in position. The entrance of Subic Bay was mined, as well as that of the harbor of Manila. But if Subic bay of a tactical standpoint remains an excellent choice, no fortification was there, and there was a risk that the planned batteries carried by land could not be installed on schedule. Shallow water of the area also allowed in the worst case ships to be sunk on purpose to serve as fixed batteries. It also rendered a fleet moves difficult, lowering speed and easing the work of coastal artillery batteries.

Revenue cutter USRC McCulloch circa 1900.

The battle

First moves

Since Montojo’s forces gradually showed signs of a defensive stance, most of the action and initiative would came from the Americans: On April 28, Montojo learned the departure of Commodore Dewey’s squadron. In emergency, he tried to install some extra guns, but officers in charge warned him that the defenses would not be ready on time. In addition he received a message from one of the highlights of Subic bay that Dewey already had sent some vanguard units in recognition. Therefore Montojo preferred to retreat under the protection of the guns of Manila and emboss his ships in front of the fortified Sangley Point, and the battery of Ulloa on Cavite. Vessels were sunk by opening valves, still able to continue firing, solidly planted on the sand. The cruiser Castilla, partly disarmed, has her sides protected by two old collier hulls filled with sand shells. Other preparations were in progress when the American fleet stood at the entrance of the bay. The latter could hear from the bridge the distant roar of the city of Manilla.

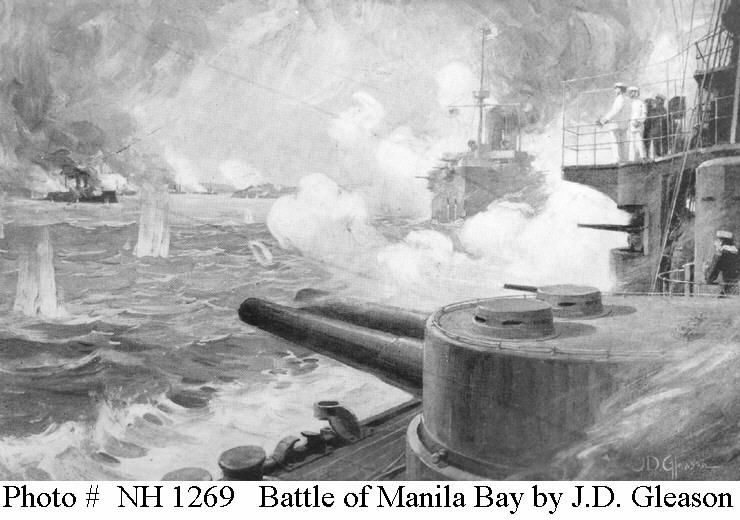

Engraving by J.D. Gleason (USN archives)n

Dewey prepares at Luzon

On april 30, the fleet arrived in Luzon. Dewey sent USS Boston and USS Concord in recognition of Subic, and USS Baltimore, which followed them in front of the fleet, received an erroneous report alleging artillery duels, quickly rectified. It was agreed that the Spanish fleet was no longer in Subic. Dewey turned to his Chief of Staff and said, “Now we have them!”. The ship’s bridges were prepared in case of fire by throwing overboard all that was made of wood, except on the ship bearing the Admiral’s flag, the USS Olympia. Tons of sand were also thrown on bridges to allow grip because of probable seawater from plumes and blood, and certain sensitive parts were protected with thick cloth soaked in vinegar, as was done traditionally to ensure no fire can take root or spread.

Dewey’s approach to the Bay

The fleet headed for the entrance of the bay, protected by islands and islets, forming two more or less wide entries: Boca Chica and Boca Grande. This was dangerous because of its many reefs and narrows, although the maneuvers was feasible. Boca Grande entrance was marked by the forts of the island of Caballo and El Frail, and Boca Chica was even narrower and more heavily defended, notably by the island of Corregidor, surrounded by fortresses able to deliver (at least in theory) a punishing crossfire. Dewey did finally move his squadron in Boca Grande, at 23 pm, lights off except the pilot stern that allowed the battle line to follow. His line passed between Caballo and El Fraile north to south, included leading USS Olympia, followed by the steamer USS Nanshan, Zafiro, McCulloch, and Petrel, then the USS Raleigh, Concord and Boston.

Forts are the first to fire

The poor coal used by USS McCulloch made that little flame that arose from her high chimney an easy pick for the watchman of fort El Fraile, which promptly ordered to open fire. The first salvo fell between Raleigh and Petrel. The whole line answered, and quickly silenced the battery. However, the telegraphist was able to sent an alert at 2 am to Admiral Montojo, already on his feat after hearing the rumbling in the distance, frowned behind the hills of Cavite.

Painting of the battle by J.G. Tyler (USN archives)

Spanish Actions Station

He sounded the rally and crew hurried to put away, or throw overboard everything that was a source of bursts, removing the boats, placing here and there many sandbags. Dewey line of battle went up quietly in the middle of the bay, and at 4:00, the armada signaled the general steadiness for combat. The men were at post, cruisers ready from the tip from Cavite to the batteries of Sangley Canaco. The Spanish fleet was forming a line of stepped defence in front of the city of Cavite, the Velasco drawing the battle line to the east of the fort at Sangley. The Zafiro, the Nanshan and McCulloch, the first two unarmed, were eventually sent back into the bay as observers, while the line drawn by the Olympia arrived at Manila, finding only cicilian steamers, tacked through the course to the southeast toward Cavite.

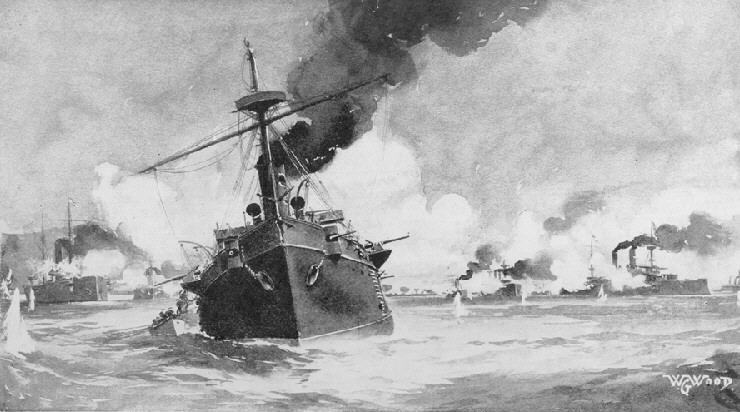

Dewey’s First pass

Dewey’s squadron was walking very slowly, at 3 knots, as he hoped that his vessels still could remain unspotted. However, Don Juan of Austria watchman saw at 4:45 am, still dark, the fire arose from U.S. ships chimneys and gave the alarm. The American line was then at 5 o’clock in the morning, dawn, under fire of the heavy batteries of the forts of Manila. Two cruisers responded with strict orders to use ammunition against these forts with economy, sparing them for the enemy ships. Montojo, seeing the artillery duel in front of Manila, decided to allow his ships to sail in an emergency and lay a few mines blocking Dewey, a risky maneuver performed by his admiral ship, cruiser Reina Cristina. Dewey spotted then at at 5:15 pm the light of the guns of Fort Canacao (one 120 mm/5-in gun) and Sangley Point (two 150 mm or 6-in guns), soon followed by those of Spanish cruisers.

Engraving of the battle, USN archive photo funds

Only 35 minutes later he ordered a counter fire when everyone was ready. The two 203 mm guns (6 in) of the USS Olympia front turret thundered, followed by those of other vessels of his squadron. By presenting the Spanish his ship’s prow first, Dewey did not run a great risk. But soon the Olympia began to turn course East to present its broadside, quickly followed by whole line, opening fire at point-blank range (400 meters).

First, the Reina Cristina was badly hit, after few impacts sparking a fire and knockout her main artillery. Dewey initiated to bring a turning movement, the famous “spiral” in reduced mode (6-8 knots, approx. 10-12 km/h), precisely in order to concentrate his fire back to the north, then back again from the east, each time bearing all its broadside. The line was far enough, however, to avoid the shallows of Canacao’s bay.

Drawing of the battle by W.G. Wood – USN photos archives

Dewey’s incredible withdrawal

At 7:30 am, Dewey suddenly learned that his main battery had only fifteen rounds left. The situation still could turn out badly very quickly. He decided, though men were still ready to fight, to withdraw to replenish his ships, and allowed his men to take a breakfast, while always under Spanish range. This reckless feat was later noted in the press as further evidence of the extraordinary American confidence over the final issue (or arrogance). But in truth the inventory had been misinterpreted, because only fifteen rounds has been fired by gunners in all that time, taking even more time for aiming than the exercise!… This was repeated later at Santiago.

USS Olympia leading the battle line in Manila Bay

But the results seemed to pay off at this distance, with more than 2% hits (at the time was a good result). The retreat order given by Dewey in any case was not well received by the crews, especially the gunners and their officers which suddenly had to provide a detailed report of losses in men and ammunition remaining while those from the boiler rooms had to run along the ships to check for damage. Confusion even shortly reigned aboard the Olympia, which amid the smoke of the fire falsely spotted a torpedo attack from two Spanish steamers, quickly knocked out by small quick-firing pieces. It turned out later that these were two small civilian boats, wrong place, wrong time.

Dewey’s second pass

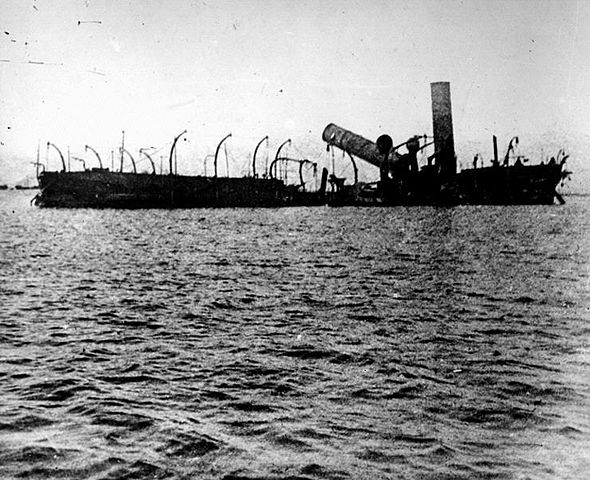

After this surrealist pause, unique in naval warfare, Deweys resumed his attack. Meanwhile indeed, the Spanish did not remain idle. Not only they replicated feverishly, but they also attempted an attack in the old style, Don Juan de Austria and Reina Cristina placing themselves in position to launch a ramming attack. When spotting the manoeuver, a barrage of fire kept them at bay. The Cristina, already deprived of its firing direction, was therefore struck by other shells, one of which entered her hospital room and the other penetrated its rear ammunition store. The latter started to burst but did not explode, promptly drowned by pumps. Nonetheless the fire quickly spread elsewhere and soon ran out of control. Later on, with only a handful of gunners remaining, half her crew ashore, and most officers killed or wounded, Montojo decided to scuttle his flagship. Taking a skiff, he quickly joined the cruiser Isla de Cuba to raise his mark and give orders. The Don Antonio de Ulloa was soon disabled and scuttled as well in shallow water, so that the crew remained on board and resumed firing. Despite the short distance, the poorly trained Spanish gunners scored almost no hit. The Castilla followed suite and was also evacuated and scuttled. Montojo ordered the remaining ships to sail towards Bacoor Bay to pursue the fight, and be scuttled in shallow water. They eventually surrendered before it took place.

The battle ends

The American fleet had taken several hits buy almost without damage and no casualties. The only serious hit was taken by the USS Baltimore, that struck the freeboard, ricocheted off the bridge, crossed a deckhouse, bounced inside the shield of a 6 inch from the opposite side, ricocheted a second time on the bridge and buried itself without exploding… There was eventually 8 minor injuries as a result of sparks and splinters. More fear than harm.

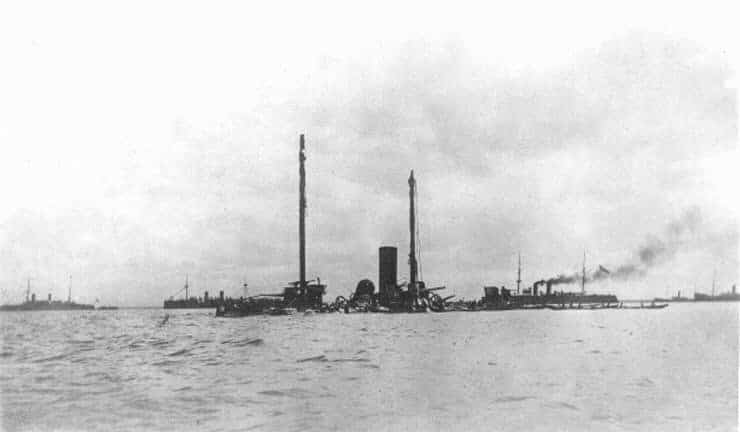

Wreck of the Castilla

At 11h 16 pm, the cease-fire became evident as the Spanish squadron appeared to have been completely knockout. However there was a final artillery duel between USS Baltimore and the still undamaged Canacao and Sangley forts, which were silenced in turn. Yet Dewey was warned that the crew of Don Antonio de Ulloa, although half submerged, was still firing with the last usable gun. In fact this was not true, but a rain of shells quickly fell on the already wrecked ship, slaughtering survivors. Yet the last remaining sailors did not capped their flag. American gunners themselves were impressed by the bravado of these Spanish crews. Gunboat USS Petrel was ordered to enter the harbor, checking unit still able to fight and then be back to make a report. Off the town of Cavite, she wiped out and silenced another battery with her 6 inches guns.

Sunken wreck of the Reina Cristina

Ceasefire

At noon, the case was made. All Spanish ships were reported permanently disabled. Montojo noted in his report 127 dead and 214 injured. The heavy batteries of Manila however, were still able to sink any American ships, but incredibly stood quiet for fear of reprisals. The only two American deaths were due to the chief engineer of the McCulloch, Randall, having a heart attack during Boca Grande maneuvers, and Captain Charles Gridley, already ill, which directed Olympia’s fire from blockhouse, transformed into real oven under the scorching sun of the region. He too badly suffered from the heat, but died a month later at Kobe, back home.

Later, the Americans would seize the cruisers Isla de Cuba and Isla de Luzon, repair them, and resumed their service in the US Navy as gunboats under their original names. In 1912, the Isla de Cuba was also sold in Venezuela, which kept it in service until the late 40. As for the Olympia, the Isla de Cuba was preserved and is currently the visiting centerpiece of Independence Seaport Museum, at Philadelphia.

Sunset victory

At sunset, the USS Olympia came quietly to the mooring at the waterfront of Manila, all flags were raised like for a parade, sailors and officers aligned in perfectly clean uniforms, and the full orchestra dressed in regalia lined up on the rear deck, beginning a series repertoire of songs in honor of the defeated man of the day, Montojo, and the gallantry of the entire Spanish fleet.

The astonished Manilese came to hear these tunes on the docks, while echoing from Cavite continuous explosions of the last stocks of ammunitions in still smoldering wrecks.

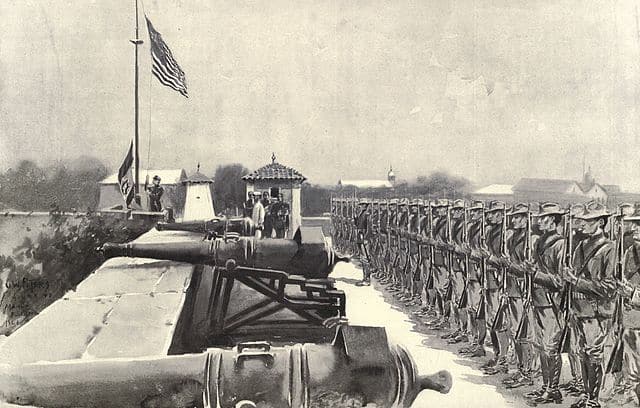

The flag is raised over the fortifications

Manila’s control

While the Spanish fleet was clearly out of action, Dewey still did not controlled the city, which unlike Cuba, became the prey of insurgents. The entire American squadron cannot not even muster a company capable of reaching the governor palace. Dewey then took the decision after news of his victory cabled, to set up a naval blockade of Manila Harbour until reddition of the officials. He was promised troops quickly. In town, several persistent rumors spoke of an alliance between Germany and Spain, in Habsburg memory. Some even predicted an imminent declaration of war by Germany, another rumor pretended an army of 10,000 Germans from Tsing Tao just landed at Subic… However, the Filipino independence movement was quickly sent into action, and revolutionaries under the leadership of Vicente Catalan, provoked the mutiny of the steamer Compania de Filipinas, July 5, 1898. Spanish officers were executed, and the ship rallied Manila, with other steamer crews. Promoted “Admiral of the Mosquito Fleet” and flying a provisional flag of the Philippine Republic, Catalan ordered to paint false barbettes on the hull and installed on the main deck dummy guns made with copper pipes painted black. Thus disguised as “cruiser”, the Compania of Filipinas, a former Tobacco carrier, rallied Subic Bay in order to obtain the surrender of the garrison of the fort, under the threat of his “guns”.

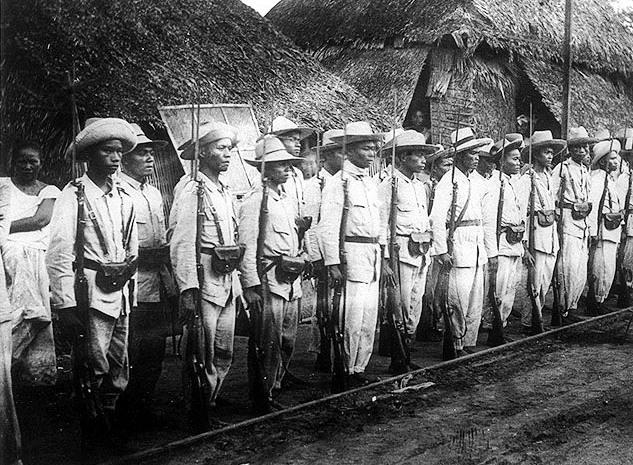

Filipino guerrillas, 1899

Philippines Control

But the Spanish garrison refused and Catalan decided to send a company to finish them. Preparations went on, when the sailors of the improvised cruiser discovered with amazement the “real” German cruiser Irene nearby. The latter raised on her mast a recognition signal and summons the company to stop. The Filipino steamer was seen indeed by the Germans as a “pirate”, the Philippine Republic being not recognized. Meanwhile a diplomatic waltz took place in Europe, each nation sending vessels to “show the flag” in these waters. The Filipino mock cruiser was no match and hoisted the white flag. Informed of the situation, Dewey sent the Concord and Raleigh to intervene and require in turn the Spanish surrender. The Irene, seeing the American ships arrived, went quietly mooring on the other side of Isla Grande, and after a warning shot from Commander Coghlan of USS Raleigh, the garrison stir in turn the white flag.

Reassured by the hope of surrendering to regular troops, the Spanish garrison left the fort in good order and joined the Raleigh. Coghlan, however, had been ordered to assign prisoners to Catalan, while the latter was ordered to hand them over to the Governor of Manila. The Philippine “independence” was granted by the Treaty of Paris signed Dec. 10, 1898, but in reality the first elected president, Emilio Aguinaldo, was seen as a puppet of the White House by the majority of former revolutionaries who took over arms. U.S. military presence, was soon dragged into a new bloody and bitter insurgency war.

New threats and challenges

Later, U.S. troops also had to face the revolt of the indigenous Moros. US presence solidified in the interwar as former Spanish bases were developed and strengthened, fortified over the years 20-30, to the point of building a “concrete battleship”. In 1941, General MacArthur directed the U.S. forces in the Philippines, and considered the approaches to Manila (by jungle or sea), impregnable. It was December 1941, but that’s another story…

Bios

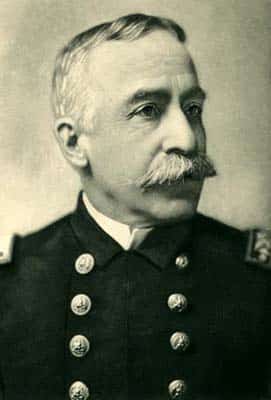

Admiral Patricio Montojo

Born in Ferrol, in Galicia (naval base, shipyard and major industrial hub), Montojo was graduated from the Naval School in Cadiz and spend years in the Philippines fighting the Moros. He was commander also of the Cuba squadron and later Río de la Plata. Montojo was wounded during the Manila Bay battle, as was one of his two sons, and was court-martialled after the war in Madrid, and imprisoned. He was released later, thanks to the intervention of his subordinates and …Dewey himself.

Cdr Georges Dewey

A graduated from the naval Academy, born in Montpelier, Vermont, he was also a decorated veteran of the civil war, for his service on the USS Mississippi, ramming the CSS Manassas. He also took part in the Battle of Port Hudson, and promoted by Farragut, commanded the USS Agawam, USS Colorado and fought at Ft Fisher. As a commodore he was assigned to the Pacific Squadron in 1893 and acted masterfully at the head of his squadron from the USS Olympia at the battle, for which he became a hero after the war, being offered multiple decorations and a priceless sword by the president.

This article is part of three dedicated to the Spanish-American War

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign