New Orleans class cruisers (1933)

USA (1933-37)

USA (1933-37)

USS New Orleans, Astoria, Minneapolis, Tuscaloosa, San Francisco, Quincy, Vincennes

New Orleans class: Veterans of Guadalcanal

Faithful to the peacetime principle of improving small classes of cruisers or battleships, the numerically important New Orleans class was in reality three sub-classes, with each time small improvements:

Design #1: New Orleans, Astoria, and Minneapolis.

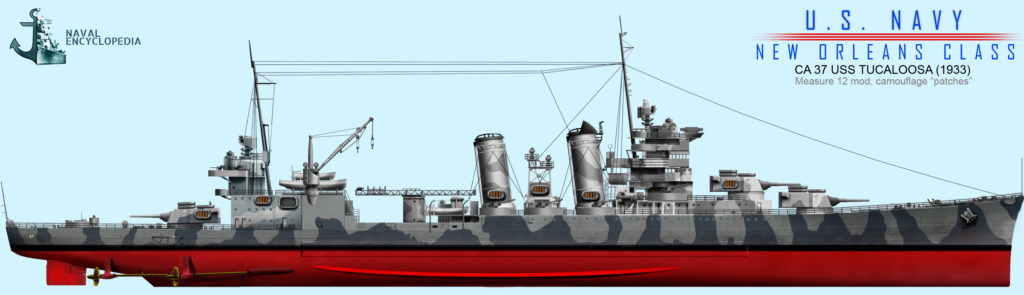

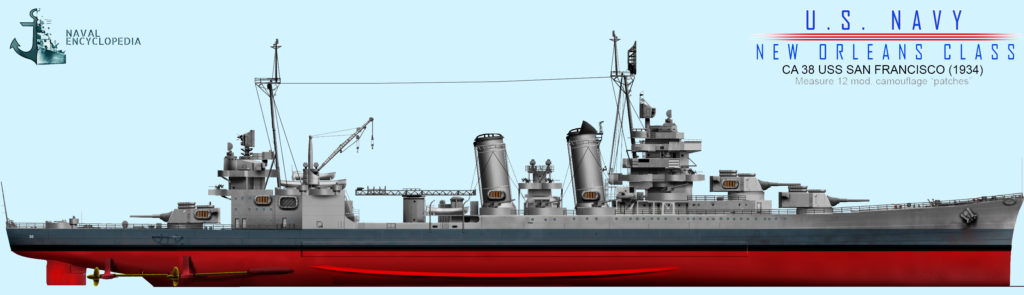

Design #2: Tuscaloosa and San Francisco.

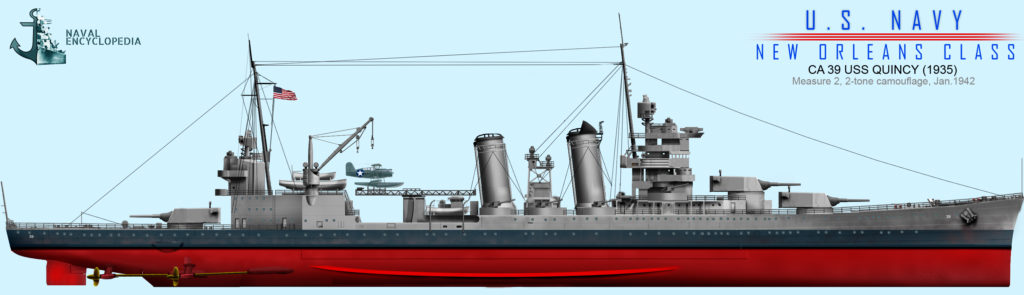

Design #3: Quincy and Vincennes.

They were laid down for New Orleans (CA-32) on 14 March 1931 so her design was worked out since 1928. The last of the class, USS Vincennes, was completed on 24 February 1937, so a span of seven years. They innovated compared to the previous relatively similar Northampton and Portland classes, improved in some ways and more stable, less “wet” than the unstable Pensacola class, mostly on the account of protection, as the armament was basically the same as previous cruisers.

These cruisers however became infamous for going through perhaps the fiercest surface battles of the Pacific War. USS Astoria, Quincy, and Vincennes were indeed all sunk in the Battle of Savo Island, while three others were heavily damaged, also during the long Guadalcanal campaign. Tuscaloosa was fortunate enough to serve in the Atlantic, and went totally unharmed from the war. But because of this early, constant engagement the New Orleans class collectively earned 64 battle stars. None was preserved however, and they were sold for scrap in 1959. The three “ironbottom sound” wrecks were rediscovered during a sonar campaign led by Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen in 2015. But they have not been explored yet. Were the New Orleans flawed in any way, or just victims of circumstances ? Let’s find out:

Design development of the New Orleans class

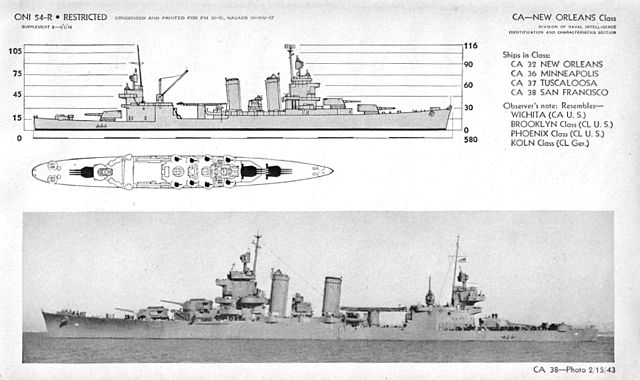

ONI 1943 recoignition plate of the class

Despite the class early development started as the Portland/Northampton were in construction, the New Orleans class were still seen as a radical departure over previous designs, still associatded with the early “tin-class cruisers” fad born from compromises linked to the Washington treaty limitations: They were limited to 10,000 tonnes standard. But soon afterwards came the London conference which capped the heavy cruisers (8-in armed cruisers), and so were born the Brooklyn, which innovated radically in other ways and announced the next wartime Wichita, Cleveland, and Baltimore-class cruisers. New technology were implemented on the New Orleans class in anticipation of wartime construction, for future cruisers already in the planning stage and non-compliant to treaties. The USN was perfectly aware of the 10,000-ton cruiser being inadequate to properly perform in war time its given duties properly.

Originally it was Tuscaloosa the lead ship, but Astoria, New Orleans and Minneapolis previously laid down as supplementary Portland-class cruisers were reordered to the Tuscaloosa design in 1930 and New Orleans was launched first. In addition, Portland and Indianapolis came from civilian yards and were completed as designed.

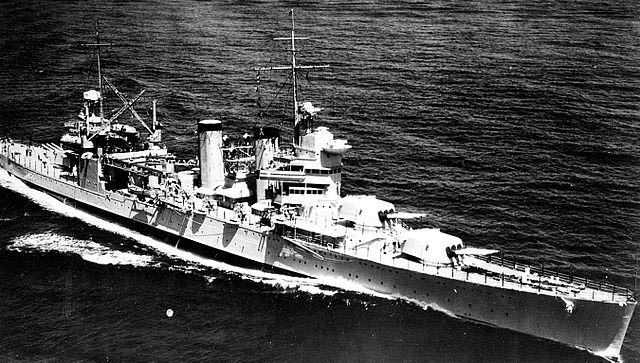

USS Vincennes in the Panama Canal in 1938

Design of the New Orleans class

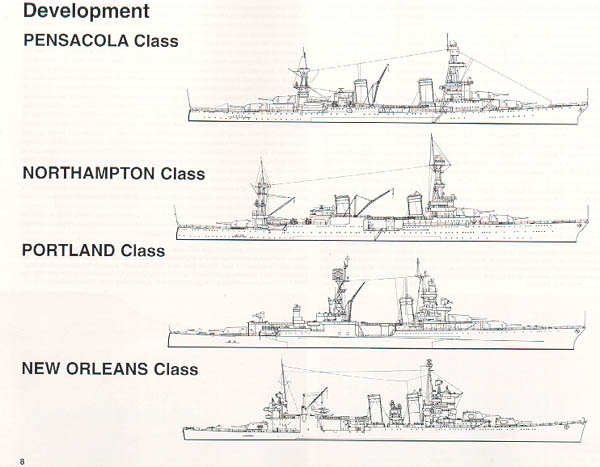

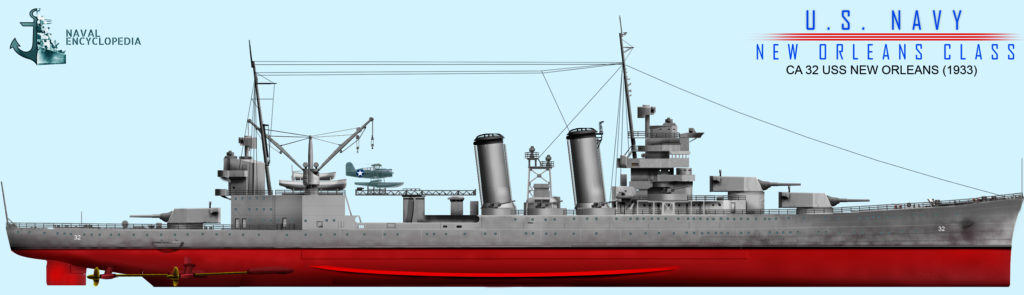

An explicit comparison of the four classes: The New Orleans are shorter, smaller, but the spared displacement weight is used to improve protection dramatically, although by figures alone it was still modest, 5-in at best for the shorter belt and conning tower. Speed was untouched as well as armament. Overall when introduced in service these cruisers became popular, with their distinctive appearance with two heavenly spaced raked funnels, and tall three-bridges superstructure and were considered very good-looking vessels.

They also differed from previous ships by dispensing of the aft tripod mast: They had a raked bow instead of the clipper bow of previous vessels, the hull was overall lower, thus saving weight and making a less exposed silhouette.

The forecastle deck was extended back to the second funnel, allowing the more ideal placement of dual purpose guns. The two funnels were closer together and a large search light tower was placed in between. Aircraft facilities were now relocated further aft and the hangar also integrated on its roof the second conning station, saving space, with a single, light mainmast between two pedestal cranes. The letter served both the spotter planes and onboard boats.

Powerplant:

Four Westinghouse gearing steam turbines, mated each on their own propeller shaft, were fed by eight Babcock & Wilcox high-pressure steam boilers. In total they produced an output of 107,000 hp (79,800 kW), for a rated speed of 32.75 knots (60.7 km/h), the same as the previous Portland. Their range was approximately 14,000 nautical miles (26,000 km) obtained at a cruise speed of 10 knots or 5,280 nautical miles at 20 knots, thanks to a capacity of 3,269 long tons (3,321 t) of bunker oil. This could be expanded in wartime, notably by using the ASW compartments. But they were also fitted in order to be refuelled at sea by a fleet oiler or another ship underway. Their sea trials and peacetime exercises shown no serious shortcomings either ith their powerplant or seakeeping qualities and the treaty limit was not exceeded. They were overall successful in reaching their own goals, but still were inferior to some Japanese and German designs (like the Myoko class or Hipper class).

Armament:

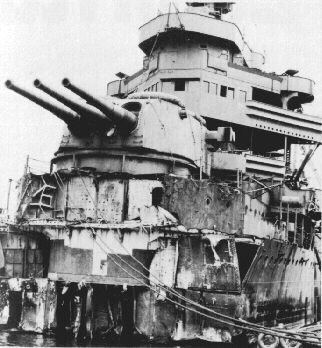

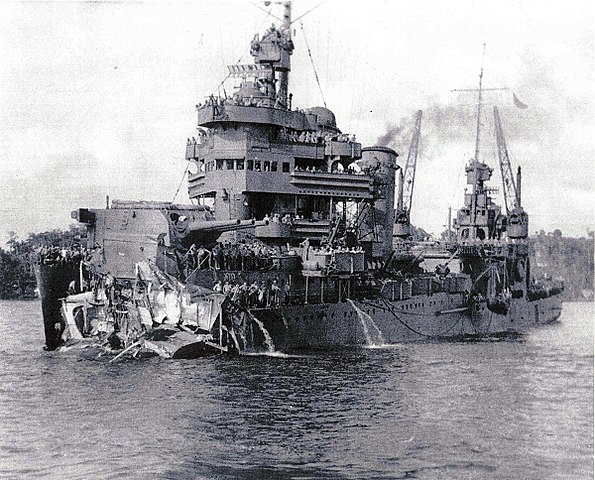

The damaged bow of USS New Orleans after the battle of Tassafaronga, showing her upper 8-in turret and associated barbette, now exposed.

Main armament: Nine 8 in/55 caliber Mark 14 guns (Mark 9 guns after World War II broke out) in triple mounts, like previous classes. Two turrets, with one superfiring were on the forecastle and on aft, one level lower.

however they differed as USS New Orleans was given the Mark 14 Mod 0 model, USS Minneapolis had the Mark 15 Mod 1 while the remainder had the Mark 12 Mod 0. Turrets faces also differed as Mark 14 guns ships were protected by rounded face turrets while the Mark 12/15 were housed in flat faced turret.

These 8 in guns fired an armor-piercing round of 260 pounds (118 kg) at 2,800 feet per second (853 m/s) and up to a range of 31,860 yards (29,130 m). As tested it can penetrate 5 inches of armor plate at 19,500 yards (17,830 m). Each turret had a provision of xxx rounds, xxx in total.

5-in/50 dual purpose guns onboard USS New Mexico in 1944: New Orleans cruisers also had open mounts, four on each side amidships.

Secondary armament: As previous ships also, the New Orleans carrier eight single mount dual purpose rapid fire 5 in/25 cal. Against surface targets they were able to deal with destroyers and small vessels, and aerial targets thanks to fragmentation shells. This ubiquitous gun equipped a large number of battleships and cruisers during WW2. It was given 52 to 54.5 lb (23.6 to 24.7 kg) shells at a 2,100 ft/s (640 m/s) and thanks to a mount allowing a -15 – +85° elevation and 360° traverse, it could hit a target at 14,500 yards (13,300 m) on the surface at 40° angle, and up to 27,400 feet (8,400 m) in ceiling.

Anti-aircraft armament:

The New Orleans class still had the old scheme of anti-aircraft defense and apart the heavy 5-in had no intermediate caliber but the low end of it: Eight .50 caliber water-cooled machine guns in single mounts were opposed to deal with low-flying aircraft in close defense. Acceptable by the early 1930s standard, it was replaced by modern 40 mm and 20 mm guns after WW2 broke out. But December 1941 however the whole New Orleans class was still clearly deficient for air defense as shown by the relative impunity of the Japanese at Pearl Harbor. The designers chose to enlarge the forecastle deck, allowing this battery of 5-inch guns to be mounted closer, thus facilitating ammunition delivery.

When available, quadruple 1.1 in guns (28 mm “Chicago Piano”) and Oerlikon autocannons replaced the .50 caliber guns). Early radar units and fire control directors were also added but radar developments gave the Allies an edge over the enemy. By late 1942, 40 mm Bofors in twin and quadruple mounts gradually replace the quadruple 1.1-in mounts, without regret. This went on gradually as, to make room and save weight, aircraft, cranes and catapults were removed thanks to better radars, more 40 and 20 mm guns were added, including their associated electrical and guiding equipment, making the ships dangerously unstable, but in late 1945 captains wilfully accepted this to get a proper air defence.

USS Quincy underway on 1 May 1940, as seen from a Utility Squadron One aircraft. Note identification markings on her turret tops: longitudinal stripes on the forward turrets and a circle on the after one. Official U.S. Navy Photograph, from the collections of the Naval Historical Center

Armour protection:

By far the most interesting aspect of the class was its clearly improved armour, thanks to weight savings by reducing dimensions. The New Orleans class were indeed the last to respect the Washington Naval Treaty tonnage limitations, which imposed draconian measures to not sacrifice protection. With a hull 12 feet (3.7 m) shorter than previous cruisers, this also traduced into a lesser gap between barbettes and therefore also a shorter belt and citadel. Only the machinery and vital internal spaces were protected, and armour plates were increased to 5 inches (127 mm). The machinery bulkheads were also thicker at 3.5 inches (89 mm). The deck armor rose to 2.25 inches (57 mm). It was a first as indeed calculations showed that the barbette and turret armor with their slopes would withstand a 8-in shell. Turrets had 8 inches on the front, 2.75 inches (70 mm) on either side and the roof was covered by one inch (25 mm) while barbettes had 5 inches walls, while USS San Francisco tested barbettes protected by 6.5 inches (170 mm) thick plates. The main 8-inch turrets were actually smaller but had a more effective angular faceplate.

In detail, 1520 tons of armour total.

-5″ (127mm) belt tapering to 3″ (76mm) on 0.75″ (19mm) STS plating

-3″ (76mm) machinery bulkheads tapering to 2″ (51mm)

-4.7″ (119mm) magazine sides tapering to 3″ (76mm)

-1.5″ (38mm) magazine bulkheads

-2.25″ (57mm) armor deck

-8″/1.5″/2.25″ (203mm/38mm/57mm)) turret faces/sides and rear/roof

-5″ (127mm) barbette

-2.5″ (64mm) conning tower

To put things in perspective, the Northampton belt was up to 95 mm or 3.75 inches, its Barbettes walls were just 1.5 in (38 mm) in thickness, while the turrets were protected by 2.5 inches (64 mm) and the conning tower was given walls 1 1⁄4 in (32 mm) strong. Although in some cases they could withstand 5 in shells, they were not immune to 6-inches shells, let alone 8-inches shells. This was the “paper cruiser” era. All in all, this Protection total combined weight represented 15% of the overall displacement against only 5.6% in the Pensacolas and 6% in the Northampton and Portland. So it almost tripled, but this was traduced by smaller fuel bunkerage, thus, reducing their range, compensated by their ability for refuelling at sea. This proved quite helpful in operations indeed.

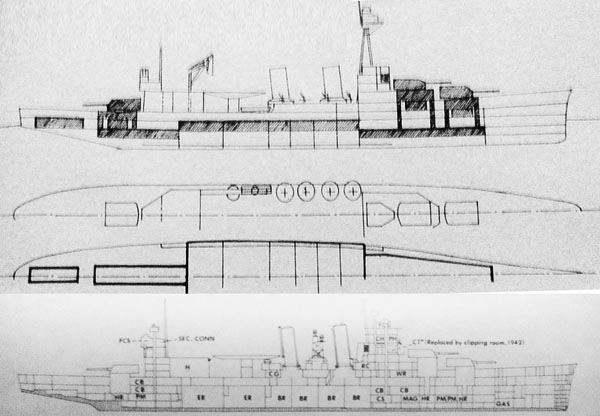

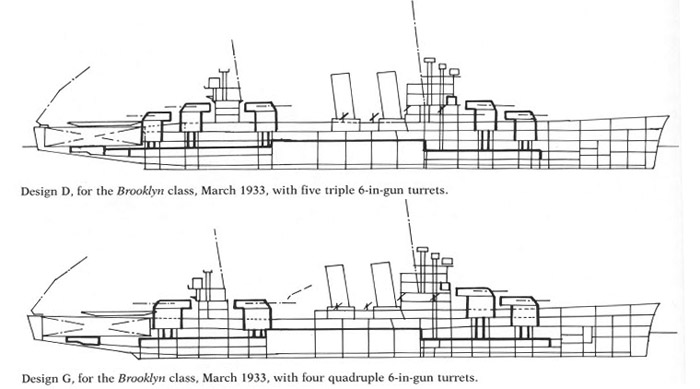

Preliminary design details (ship review)

Preliminary design compared to the following Brooklyn class

The New Orleans class had their magazine protected by 4 inches (100 mm), much better than previous vessels, and in addition it was decided to place them a deck lower, below the waterline. This forced any incoming shell to go through several decks before going there, dissipating its energy, in addition to the internal splinter belt and armor deck.

This was by all accounts, an exceptionally good level of protection for the vitals, however the hull volume was still vulnerable to underwater damage and massive flooding. This was shown when the forward section of the New Orleans went off at the Battle of Tassafaronga.

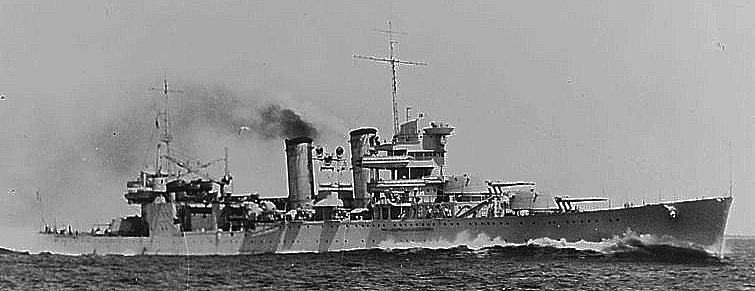

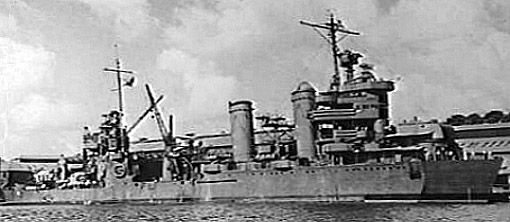

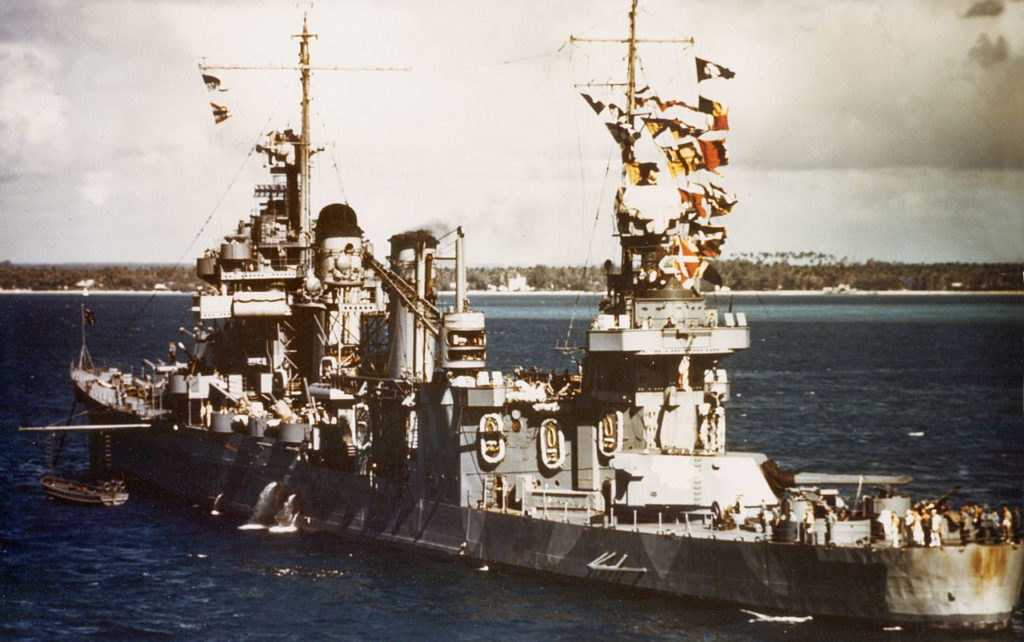

USS Tuscaloosa 1930s

USS San Francisco enters San Francisco bay December 1942, giving a good sense of the scale of the bridge.

Characteristics (1941):

Displacement: 9,950 tonnes, 12,400 tonnes fully loaded

Dimensions: 179,27 x 18,82 x 5,9 m ()

Propulsion: 2 shafts, 4 turbines Westinghouse, 8 B&C boilers, 107 000 cv. 32,7 knots.

Armour: Turrets 30-70 mm, belt 120mm, CT 5-in (130) casemate 80 mm, deck 60 mm.

Armament: 9 x 203 mm (3×3), 8 x 127 mm, 8 x 12,7 mm HMG, 4 seaplanes

Wartime lessons

As three cruisers of the class were sunk in a single night, USS Astoria, Quincy, and Vincennes off Savo Island in 1942 and the Guadalcanal campaign, the admiralty decided to retired remaining ships for major overhauls. Their main goal was not to imprve protection but to lessen top heaviness because of the electrical and radar systems and additional anti-aircraft armament. It was also possible because of technology advances. They gained a new appearance as the bridge was rebuilt, they lost their conning tower and new electronics systems were installed.

In detail:

In 1942-44:

-Splinter shields added to 5″ gun positions.

-0.50 machine guns replaced with six single 20mm Oerlikon AA guns.

-Equipped with SC and Mark 3 radar.

From 1942: Light AA increased by up to ten single 20 mm Oerlikon guns.

By Late 1943:

-1.1″ guns (28 mm) replaced with six quadruple 40 mm Bofors AA.

-SC radar replaced by SG (two sets), SK, and Mark 4 radar.

-Conning tower removed to reduce top weight.

1944-1945: Increased light AA, sixteen single, and fourteen twin 20 mm Oerlikon guns. Total: 24/32 x 40 mm Bofors, 54 x 20 mm Oerlikon

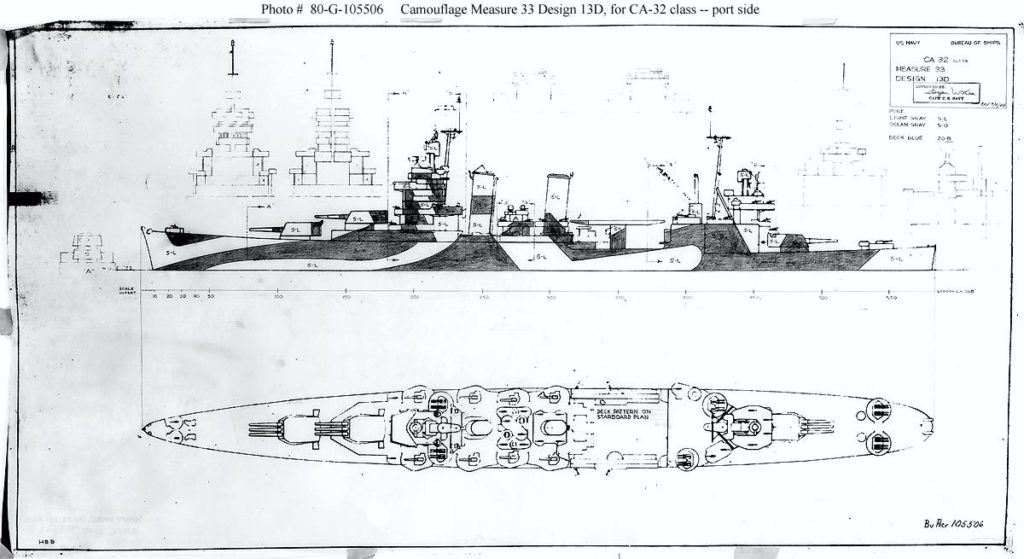

USS Tuscaloosa 1944 ship camouflage measure 33 scheme (navsource)

Characteristics (1945):

Displacement: Unknown, around 12,900 tonnes fully loaded

Dimensions: Same

Propulsion: Same

Armour: Same

Armament: Same but up to 24-32 (6-8×4) x 40 mm, 40-54 x 20 mm Oerlikon AA

First Published on 2017/02/18 and completely rewritten and expanded

USS San Francisco in March 1945, the horizontal livery in effect since the end of 1944: Light gray/medium gray/dark blue – Illustration by the author

Sources/Read More

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_Orleans-class_cruiser

See the official report on New orleans torpedo damage, lunga point Nov. 1942

On modelwarships.com

Conways all the world’s fighting ships 1922-1947

On navsource.org

On the pacific war online

Models corner

Trumpeter 1/700 USS New Orleans CA32

Trumpeter 1/700 USS Quincy CA39

Trumpeter 1/700 USS Tuscaloosa CA41

Same manufacturer: San Francisco, Minneapolis

Pit-Road 1/700 Sky Wave CA32 USS New Orleans

WSW 1/700 700-11 WSW USS Quincy CA 39 resign kit

White Ensign Models photo etch for the Trumpeter kit No. PE 790 1:700

Shipcraft 13 – New Orleans Class Cruisers Paperback

AK Interactive! MODELLING FULL AHEAD 2 NEW ORLEANS CLASS

Review on Modelwarhips.com

The New Orleans in action

The Astoria, Quincy and Vincennes were destroyed during the Battle of Savo in August 1942, and the others participated in many particularly hard engagements in Guadalcanal, were badly damaged but were repaired and survived. Only USS Tuscaloosa had a rather more “cushy” affectation, in the less contested Atlantic.

USS New orleans – CA-32

Interwar

New Orleans was laid on 14 March 1931 at the New York Nyd (Brooklyn Navy Yard), launched on 12 April 1933. The champaign bottle was thrown by by Cora S. Jahncke, native of New Orleans and daughter of Ernest L. Jahncke, president of the Jahncke Shipbuilding Co. of New Orleans. He also served as Assistant Secretary of the Navy under Herbert Hoover. USS New Orleans CA-32 was commissioned at the yard on 15 February 1934. Captain Allen B. Reed took command under Rear Admiral Yates Stirling, Jr. the yard commander and former Assistant of Jahncke. As the lead ship in a class of seven new heavy cruisers she also headed a “family” that altogether earned more than sixty battle stars during the war and CA-32 was awarded 17 of them, among the top four highest decorated USN warships of World War II.

From 30 August 1935, she depared New York for her shakedown Transatlantic crossing. She arrived in Great Britain and stopped in Scandinavia, in May and June 1934, making good will visits to Stockholm, Sweden, Copenhagen, Denmark, Amsterdam, Netherlands and Portsmouth. She crossed back and was in NyC on 28 June. However she soon sailed, on 5 July, to Balboa in Panama, meeting her USS Houston which carryied President Roosevelt to Hawaii. She also took part in an exercise with the only USN Flying aircraft carrier, USAS Macon off the California coast. She met at Honolulu on 26 July 1934 the USS Astoria and Oregon and the cruise ceased in August while she sailed back to Panama and Cuba, stopping at San Pedro (Ca) on 7 August. After some exercises Off New England she stopped at her namesake city and in March 1935 she joined the Cruiser Division 6 (CruDiv 6) at San Pedro. She was open for public viewing and later participated in Fleet problem XVI from until 10 June. This was the largest mock battle so far, over five million square miles in North Central Pacific. The exercise covered areas such as Midway, Hawaii, and the Aleutian Islands, with 321 vessels. She visited San Diego as part of a 114 warships in a massive fleet review for the California Pacific International Exposition. Back to Brooklyn Navy Yard in drydock for maintenance, she resumed service in 1937 in the Pacific, and made a winter training in the Caribbean in 1939 but was sent to the Hawaiian Detachment on 12 October 1939, for exercises and patrols.

Pearl Harbor

USS New Orleans happened to be Moored in Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941. Her engines were under repair and as power shut out engineers raised steam to work by flashlight. However men were on the deck, firing at the Japanese planes which whatever they could lay their hands on: rifles and pistols (indeed the AA mounts were powerless). The crew broke the locks of ready ammunition boxes as the keys were not onboard this sunday. The 5″/25 cal AA gun still could to be aimed and fired manually but it took too much time, as in addition the ammo hoist were inoperative. Ammunitions had to be carried by hand from two decks below. The crew had to shelter or duck during strafing attacks, but the cruiser was not the main target yet for bombers or TB planes. However some men succeeded at having some 54 lb (24 kg) shells pulled by ropes attached to their metal cases and ammunition lines were formed. There were a few injured but no casualty.

After her engine work was partially completed, CA-32 left Pearl Harbor to escort troopships to Palmyra and Johnston Atolls using only three engines. On 13 January 1942 she was in San Francisco tat the docks to install her new search radar and her first 20 mm Oerlikon guns. She departed on 12 February to cover another escort convoy to Brisbane, Australia and then to Nouméa New Caledonia, before going back to Pearl Harbor, joining Task Force 11.

Battle of Coral Sea: TF 11 was at sea on 15 April to meet USS Yorktown task force, southwest of the New Hebrides. This composite force will win the Battle of the Coral Sea on 7–8 May 1942. This crucial victory drove back the Japanese force threatening Australia and New Zealand. When USS Lexington was heavily damaged, USS New Orleans assisted her, many crewmen diving overboard to rescue survivors as the carrier was burning. They saved 580 of Lexington’s crew, later landed at Nouméa. The cruiser patrolled the eastern Solomons and was back to Pearl Harbor.

Battle of Midway: The cruiser sailed on 28 May to escort USS Enterprise, to Midway. On 2 June, she and Enteprise met the the Yorktown force, and on 4 june the battle began. Crucially during the battle th Japanese Navy lost her four most experienced aicraft carriers Akagi, Kaga, Soryu and later Hiryu although this was the work of dive bombers. USS New Orleans never had the occasion to fire but her AA, but the USS Yorktown was lost.

Battle of the Eastern Solomons: USS New Orleans left Pearl Harbor on 7 July bound for the Fiji Islands, as part of the invasion of the Solomon Islands. She protected USS Saratoga, driving off enemy air attacks on 24–25 August. She also provided artillery support to the USMC beachhead on Guadalcanal. The Battle of the Eastern Solomons turned the Japanese off. As USS Saratoga was torpedoed, USS New Orleans escorted her back to Pearl Harbor, at home on 21 September.

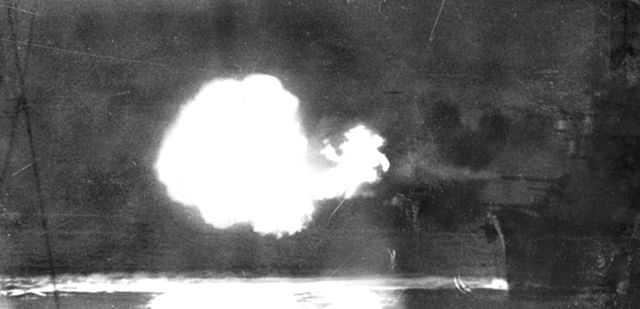

Battle of Tassafaronga: As USS Saratoga was repaired, USS New Orleans was back to Fiji in November 1942, and then sailed to Espiritu Santo, on 27 November. Soon she was back to the cauldron of the Solomons. She was part of a force of five cruisers and six destroyers at the Battle of Tassafaronga, which happened on the night of 30 November. This force trie to intercept and stop a Japanese destroyer-transport force. USS Minneapolis was hit by two torpedoes and New Orleans sheer away to avoid collision, still crossing the track of a torpedo detonating her forward magazines and gasoline tanks. This was a tremendous explosion, cutting clean off a 150 ft (46 m) section of her bow forward of turret No. 2. Turret No. 1 with the rest of the bow was swung around the port side, banging on the hull and eventually sinking at the stern. While doing so as it still partially floated, the port inboard propeller was badly damaged. This was no less than 1/4 of the ship that was gone, but thanks to bulkheads, flooding was controlled. Despite of this, USS New Orleans was limping to 2 knots and the crews had to master a fire forward. After a miraculous work, the ship was able to sail to Tulagi Harbor on 1 December.

The crew then tried to hide the ship the best they could, fearing a Japanese air attack. She was covered by coconut logs, and after more provisional repairs which lasted for 11 days sailed stern first, to Cockatoo Island Dockyard in Sydney, arrived on 24 December. The damaged propeller was replaced and the Australians managed to weld a temporary stub bow for the ship to depart again, on 7 March 1943 for Puget Sound NyD. But again, she sailed backward for the entire trip. There, she had a new bow fitted and Minneapolis’ No. 2 Turret. She was completely repaired as well as modernized and refitted entirely with the new reconstruction standard. After the superstructures, radars, guiding systems and AA, her machinery was entirely overhauled anew.

USS New Orleans underway Puget Sound 30 July 1943

USS New Orleans in Tulagi with a provisional bow to sail back home

Because of this long interruption her service in 1943 was short. She was in Pearl Harbor on 31 August, and joined a force shelling Wake Island on 5–6 October, also driving off an air attack. On 10 November she sailed to shell the Gilberts on 20 November, and the to escort carriers in the eastern Marshalls on 4 December. She drove off several aerial attacks, covering USS Lexington (ii), but could not prevent the carrier to be torpedoed and she guarded her until repairs at Pearl Harbor on 9 December.

Operation in 1944-45 were relatively less stressful, but New Orleans still had her fair share of fighting. On 29 January 1944 she was seen shelling the Marshalls, blasting Japanese air installations and shipping in Kwajalein. On 11 February she escorted fast carriers on the Truk raid in the Carolines, on 17–18 February 1944. USS New Orleans and other crisers and destroyers circled the atoll to catch escaping IJN ships and a light cruiser and destroyer were destroyed. Newt was the Marianas, and back to Majuro and Pearl Harbor.

USS New Orleans resumed her escort of the carrier force in the Carolines by March-April 1944, covered Allied landings at Hollandia in New Guinea. On 22 April however, one of Yorktown (ii)’s plane hit New Orleans’ mainmast, and a gun mount before tumbling into the sea, sprayed gas, but despite two casulalties, the damage control party did its job and the ship went on patrolling off New Guinea, and raiding with the carrier force Truk and Satawan on 30 April. On 4 May she was back in Majuro and prepared for the invasion of the Marianas.

USS New Orleans left Kwajalein on 10 June, shelled Saipan on 15–16 June, and escorted the carriers towards the Japanese Mobile Fleet in what became the Battle of the Philippine Sea. The cruiser patrolled and shelled Saipan and Tinian, was back in Eniwetok in August, to sail again for a raid raids on the Bonin islands, and then Iwo Jima on 1–2 September. She also provided cover for the invasion of the Palaus. She then resumed her escort at Okinawa, Formosa, and Northern Luzon.

Battle of Leyte Gulf and Okinawa: On 25 October USS New Orleans was screeing the Fast Carrier Strike Force northwards, driven by the bait force of Jisaburō Ozawa. She was part of Task Force 34 which was sent to find and destroy crippled ships with gunfire, sinking the Chiyoda and destroyer Hatsuzuki. In November 1944 after a stop at Ulithi, USS New Orleans assisted the carrier force in the Philippines during the invasion of Mindoro. By december she was back at Mare Island NyD for an overhaul, making a trainng cruiser in Hawaii. On 18 April 1945 she was in Utilhi, and joined TF 54 for the invasion of Okinawa, arriving on 23 April. She engaged shore batteries and shelled enemy lines in close coordination with USMC troops. She stayed there for two months before supply and repair in the Philippines. She was present at Subic Bay when the war ended. But her service was not over as she covered the internment of Japanese ships at Tsingtao, evacuated liberated POWs and landing troops in Korea and China. She carried troops from Sasebo U.S. Fleet Activities base to San Francisco and later with Guam, bfore visiting the city of New Orleans for a last time, before sailing to Philadelphia Navy Yard on 12 March 1946 to be later decommissioned on 10 February 1947.

USS Astoria – CA-34

USS Astoria operating in Hawaiian waters on 8 July 1942

USS Astoria off Guadalcanal 1942

USS Astoria CA 33) was laid down on 1 September 1930 at the Puget Sound Navy Yard, and at that stage was classified as a light cruiser due to her original thin armor, but became a heavy cruiser as defined by the London Naval Treaty. She was launched on 16 December 1933, commissioned on 28 April 1934 with Captain Edmund S. Root in command. This summer 1934, she conducted a long shakedown cruise in the Pacific. She visited the Hawaiian Islands, Samoa; Fiji and Sydney or Nouméa (New Caledonia), and back to San Francisco in September.

Until February 1937, she was part of Cruiser Division 7 (CruDiv 7), a Scouting Force based at San Pedro, California. But she was reassigned to CruDiv 6, although still at San Pedro. She took part in peacetime maneuvers and the annual fleet problem.

At the beginning of 1939, she was taking part of Fleet Problem XX in the West Indies under command of Richmond Kelly Turner. She sailed from Culebra Island in March for Chesapeake Bay and took fuel at Norfolk before heading to Annapolis in Maryland. There she took the remains of former Japanese Ambassador to the United States Hiroshi Saito back to Japan as a gesture of appeasament and for the return of Edgar Bancroft on Tama in 1926. USS Astoria was back on 18 March 1939, carrying Naokichi Kitazawa, Second Secretary of the Japanese Embassy also for the Japanese trip.

In the Panama Canal Zone she was visited by officials and a Japanese colony delegation, paying their respects to Saito’s ashes and she headed for Hawaii, arriving on 4 April, greeted by Lady Saito and daughters just arrived from liner Tatsuta Maru. For her second part of the trip to Japan she was accompanied by the destroyers Hibiki, Sagiri, Akatsuki, and arrived in Yokohama harbor on 17 April, firing a 21-gun salute, returned by Kiso while sailors carried the ceremonial urn ashore. It was followed by lavish hospitality. She sailed for Shanghai on 26 April, receiving Admiral Harry E. Yarnell the C-in-C, Asiatic Fleet, and headed next to Hong Kong. She stopped in the Philippines, Guam, helping finding the grounded Army transport U. S. Grant. She covered around 162,000 sq mi (420,000 km2) without success and return to Pearl.

She was part of Hawaiian Detachment as war broke out in October and participated in Fleet Problem XXI in Hawaiian waters. She was based there until the 1941 attack. On 2 April 1941, she returned briefly on the west coast, Long Beach and Mare Island Navy Yard for ha refit, receiving quadruple-mount 1.1 in (28 mm)/75 AA and a pedestal for a future air-search radar. She was back in service in July 1941, sailed for Long Beach, San Pedro, and Pearl Harbor. There, she operated between Oahu and Midway untli September, trying to find German raiders roaming between Guam and the Philippines. She escorted Henderson to Manila and Guam, and was back in Parl on 29 October, making more patrols and training. In December 1941, Admiral Husband E. Kimmel, ordered reinforcements to Wake Island and Midway and Astoria from 5 December (Rear Admiral John H. Newton TF 12) USS Lexington, escorted the relieving force.

Astoria on the 7yh some 700 mi (1,100 km) west of Hawaii, closing with Midway, later joined by USS Indianapolis the flagship (Vice Admiral Wilson Brown, of the Scouting Force), and TF 12 searching the southwest of Oahu to intercept and destroy any enemy encountered ship off Pearl Harbor. She entered on 13 December at Pearl to resupply and was back to sea, to cover a convoy, a civilian oiler and the seaplane tender Tangier to Wake Island, but the latter fell and the force was recalled. She remained at sea until 29 December, back at Oahu, her crew being completed by 40 sailors from USS California. She departed on 31 December with TF 11 (USS Saratoga), patrolling until January 1942 until I-6 torpedoed the carrier, back to Pearl on 13 January 1942. She returned to sea on 19 January with TF 11 again, this time the repaired USS Lexington and the cruisers Chicago and Minneapolis, nine destroyers to patrol northeast of the Kingman Reef to Christmas Island line. They were to met the oiler Neches for supply bound to cover an air raid on Wake Island and shelling while I-17 sank the oiler which cancel the operation.

On 16 February, USS Astoria sortied with TF 17 (USS Yorktown, cruiser Louisville, destroyers Sims, Anderson, Hammann and Walke, oiler Guadalupe, Rear Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher) to patrol vicinity of Canton Island but a second carrier was called to strengthen TF 11 at Rabaul. The force proceeded southwest of the New Hebrides on 6 March and combined force while IJN landings at Lae and Salamaua in New Guinea changed plans and the combined force was hastened to the Gulf of Papua, adding to the mix the cruisers Chicago, Louisville, and HMAS Australia (Rear Admiral John G. Crace) while Brown remained off Rossel Island (Louisiade Archipelago). The force was also to shield Port Moresby and convered a troops convoy to Nouméa. A raid on Lae and Salamaua was conducted by Yorktown and Lexington on 10 March 1942, caliming three transports, a minesweeper, damaging a light cruiser, minelayer, three destroyers and seaplane carrier and delayed the conquest in the Solomons.

Battle of the Coral Sea: USS Astoria take part in TF 17, replenish at Nouméa along with Portland, Hughes and Walke on 1 April, and was in the Coral Sea for two weeks, then Tongatapu, on 20–27 April. USS Astoria screened Yorktown during its air raids on off Tulagi and was less active on 5–6 May, but screened Yorktown on the 7th sinking the Japanese carrier Shōhō and another raid on 8 May. USS Astoria prepared for the expected retaliation from Zuikaku and Shōkaku. Astoria’s executive officer, Cdr Chauncey R. Crutcher, put up an efficient protective barrage over Lexington before shifting over Yorktown depending of waves. Her gunners claimed four planes. However soon Lexington was heavily damaged and later Astoria set course for Nouméa with Minneapolis, New Orleans and destoyers. In May the force was getting ready for Midway.

Battle of Midway: USS Astoria screened Yorktown during the first wave launch and prepared for payback, coming a few minutes before noon. A weve of 18 Aichi D3A1 “Val” dive bombers were claimed by Grumman F4F-4 Wildcat from VF-3 and eight entered the combat air patrol (CAP), Astoria and Portland claming two more while six went through and badly damaged USS Yorktown. Rear Admiral Fletcher and his staff shifted his flag to USS Astoria for the remaining of the battle. Later the cruiser had to help repel 10 Nakajima B5N2 “Kate” torpedo bombers, and two Torpedoes hit Yorktown, Astoria helping rescue with its lifeboats. Astoria remained flagship of TF 17 north of Midway on 8 June before Fletcher transferred his flag to Saratoga on 11 June. Astoria was back to Pearl on 13 June and during this summer underwent and overhaul, resuming later training in the Hawaiian waters.

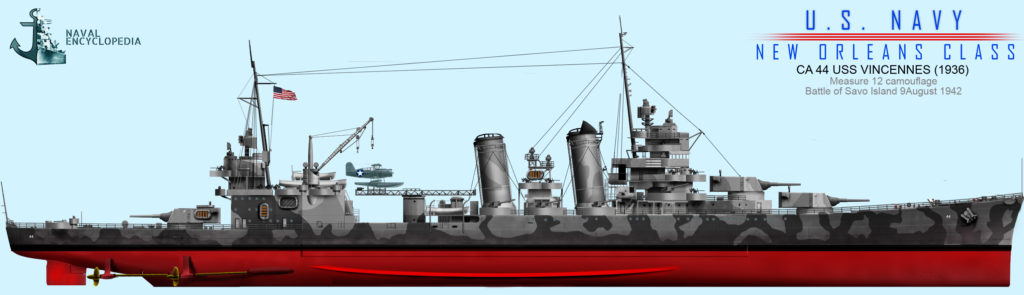

Solomons (Battle of Savo Island): In early August, Astoria joined Task Group 62.3 (TG 62.3) and Fire Support Group L, to cover the landings at Guadalcanal and Tulagi. She entered Guadalcana waters on 7 August, and covered by gunfire the Marines, repelling air counterattacks until the next day. But during the night of 8/9 August, seven cruisers of Vice Admiral Gunichi Mikawa sneaked off Savo Island at a time Astoria was patrolling east of Savo in column behind Vincennes and Quincy. Chicago was hit first, and HMAS Canberra. The Japanese force next divided into separate groups passing on either side of the USN column, including Astoria and fire was opened at 01:50. Astoria returned fire immediately before being ordered a ceasefire by her commanding officer mistaking the intruders for friendly ships. USS Astoria’s superstructures, hangar and number one turret were blasted by the Japanese fifth salvo. She was set ablaze, and the aviation fuel for her planes further lightened her for more hits.

Soon, Japanese gunfire took their toll, she lost speed, turned right to avoid Quincy off course, and took more hits aft of the foremast. Quincy however, was out of control, blazing furiously, and veered across Astoria and while the latter’s captain ordered a hard left turn, avoiding collision. Soon illuminated by IJN Kinugasa, No. 2 turret fired on the light, missing the former but hiting No. 1 turret of IJN Chōkai. The bridge at 02:25 was lost, so the captain shifted control to the central station. The cruiser started a zig-zag course south when she lost all power, just as the Japanese withdraw. 400 men and 70 wounded were assembled on the forecastle deck for evacuation. By that time, Astoria had been hit 65 times.

While the control crew tried to fight the blaze the deck grew hot forcing the wounded into the forecastle. USS Bagley later came alongside the battered cruiser to offer assistance at her starboard bow. By 04:45, the wounded were evacuated, and rescued further men on rafts, notably a few USS Vincennes’s survivors. At daylight Bagley came to Astoria’s starboard quarter and took onboard the remaining 325 men while bucket brigades still fought on, but with little hope. USS Hopkins came, securing a towline and proceeded ahead, trying to tow her in shallow water and transferred a second gasoline-powered handy-billy, to fight the fire, later joined by USS Wilson. At nine in the morning, Hopkins and Wilson departed, while Buchanan was en route as well as USS Alchiba, but it was already too late. Despite heroic efforts, the fire below decks grew in intensity, explosions soon starting and her list increased to 15° while her stern disappeared underwater. There were already too much shell holes, feeding the increasing list. Buchanan arrived at 11:30 but the cruiser could not be approached and soon Commodore William G. Greenman gave the order abandon ship. She turned over on her port beam, rolled and settled by the stern. She was entirely gone by 12:16. Later Alchiba rescued 32 more men while 219 were reported missing or killed in action.

USS Minneapolis – CA-36

USS Minneapolis 1943

USS Minneapolis made her first commission shakedown cruiser in European until September 1934 before heading for Philadelphia NYd, and a short refit, and departed on 4 April 1935 for the Panama Canal and San Diego Naval base with Cruiser Division 7, Scouting Force. She trained on the west coast Caribbean until 1939 and joined Pearl Harbor in 1940. On 7 December the next year, USS Minneapolis was fortunately at sea for gunnery practice, only 8 miles (13 km) from the base, and received order to patrol the Hawaiian waters. She took up various escort missions until late January 1942 when she joined the carrier force sent to attack the Gilberts and Marshalls, screening USS Lexington and repelling an air attack by Mitsubishi G4M “Betty” medium bombers, caliming at least one. She covered the carrier force during these raids on 20 February and also on 10 March at Lae and Salamaua.

USS Mineapolis was also engaged in the Battle of the Coral Sea and Midway. On 4–8 May 1942 she was covering Lexington and claimed three Japanese bombers, also rescuing of Lexington. At Midway on 3–6 June 1942, she again screen the carrier force. However her affectation to the Somomons would prove her downfall. She replenished at Pearl Harbor and sailed as carriers screening to cover landings on Guadalcanal and Tulagi. This was planned for 7–9 August 1942 and she remained with the carriers, helping USS Saratoga on 30 August when hit by a torpedo and managed to tow her away from danger. In September-October, she covered the landings of Lunga Point and Funafuti.

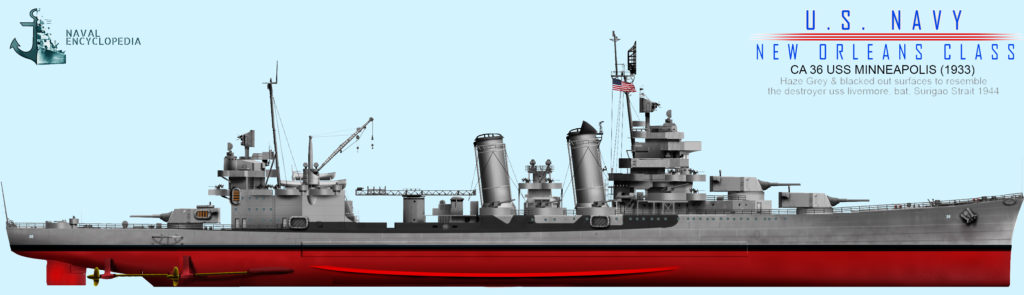

USS Minneapolis in December 1942, showing damage received in the Battle of Tassafaronga

USS Minneapolis became flagship of Task Force 67 and was at sea on 29 November to intercept a Japanese troopships convoy bound to reinforce the Guadalcanal garrison. At 23:05 she spotted six ships (wich were destroyers loaded with troops) and the Battle of Tassafaronga started when she fired her main guns first, scoring a first kill on IJN Takanami. However a second group of Japanese destroyers until then providing distant cover entered the fray and torpedoed USS Minneapolis: She took two hits, on the port bow, and number two fireroom, loosing power and like the New orleans, her bow collapsed back to the chain pipes, badly damaging her port side: The hull’s steel plating was torn and stripped away, leaving two firerooms out on the open, with seawater gushing in. However, the the skillful damage control team managed to keep the cruiser afloat. She was later able to reach Tulagi. The crew first camouflaged her with palm fronds and shrubs and she was temporarily repaired, with the help of a Seabee unit from the island. This allowed her to sail for Mare Island Naval Shipyard where she was more extensively repaired. She had a new bow built for her transit back to the shipyard. In drydock her forward bridge was remodelled as well as rebuilt anew, and she was provided with new radars and a full array of 20 mm and 40 mm AA guns.

In service again by August 1943, USS was again on the frontline, seeing every major Pacific operations but Iwo Jima. There was the shelling of Wake on 5 October, the capture of Makin in the Gilberts in December, the pre-invasion strikes against Kwajalein and Majuro, and the Marshalls invasion until mid-February 1944. She also coverred the carrier force in the the Marianas and the Carolines, and subsequent raids on the Palaus, Truk, Satawan, Ponape, among others until April 1944. She also covered operations at Hollandia in New Guinea. Later in May, USS Minneapolis shelled Saipan in preparation for the invasion which would take place on 14 June. She joined TF 58 during the Battle of the Philippine Sea on 19–20 June, screening the carriers against Japanese air attacks. She only took a bomb near-miss, but was repaired quickly with no loss of life. Later she was seen in action again at Guam. She operated there from 8 July to 9 August, supporting the Marines by provding spot on fire on demand. By her availability and accuracy she was praised by General Allen H. Turnage (3rd Marine Division Cdr.). From 6 September she provided the same accurate fire for the capture of the Palaus, and was prepared for the assault on Leyte. She entered Leyte Gulf on 17 October, claiming five enemy planes right away.

The Battle of Surigao Strait: USS Minneapolis on 24 October was part of Rear Admiral Jesse B. Oldendorf’s bombardment group with cruisers and battleships, deployed across Surigao Strait by night. PT-boats and destroyers were probing ahead in search of the enemy. Japanese ships arrived in a column, heading straight for the battleline, which coordinated a sudden devastating salvo, destroying the Yamashiro. Minneapolis also crippled the IJN Mogami and destroyer Shigure with other cruisers. Admiral Oldendorf performed the classic “crossing the T”, destroying the column with concentrated fire, with devastating effect. Minneapolis covered newt the landings in Lingayen Gulf and Luzon on 4–18 January 1945. She was also covering the landings on Bataan and Corregidor on 13–18 February. In March 1945 shejoined Task Force 54 (TF 54) in preparation for the invasion of Okinawa. She started the shelling with the rest of the fleet on the 25th, blasting Kerama Retto, to provide a safe haven.

From 1 April as troops landed, she provided a constant on demand fire, including night harassing fire. She shelled notably the airfield at Naha, and all targets opportunity signalled by radio during the campaign. However at some point, her gun barrels were badly worn out so she sailed in April, delayed after repelling the largest Kamilaze attack yet of the Okinawa operation. She claimed downed four and possible three others and depated at nightfall for Bremerton in Washington state. There, she received an overhaul and her gun barrels were relined. She was back in Subic Bay at the end of hostilities however. There was no upcoming campaign but Operation Olympic, planned in 1946.

She had the honor of being the flagship of Admiral Thomas C. Kinkaid when accepted the Japanese surrender of Korea on 9 September. Afterwards, she patrolled the Yellow Sea, and covered landing of at Taku and Chinwangtao in China, carrying back eterans to the west coast. On 14 January 1946 she was in Philadelphia, placed in partial commissioned and in reserve on 21 May, and fully decommissioned on 10 February 1947, sold on 14 August 1959 and BU.

USS Tuscaloosa – CA-37: Solo in the Atlantic

USS Tuscaloosa 23 August 1935

USS Tuscaloosa was laid down on 3 September 1931 at Camden Yard in the New Jersey, a division of New York Shipbuilding Company. She was launched on 15 November 1933, and commissioned on 17 August 1934. Captain John N. Ferguson took first command. She was particular in two ways: She was the last cruiser built on Washington Treaty standards, and made all her career in the Atlantic and Mediterranean. After a shakedown cruise down to Rio de Janeiro, Buenos Aires, and Montevideo she went on post-shakedown refits until March 1935. After a trip to Guantánamo Bay in Cuba, she joined San Diego via the Panama Canal on 7–8 April to join CruDiv 6 and taking part of Fleet Problem XVI in May off the coast of Alaska and the Hawaiian Islands.

USS Tuscaloosa main base became San Pedro in California, taking part in all exercises of CruDiv 6 like Fleet Problem XVII in 1946 another in 1937 in Alaskan waters and Hawaiian-Midway, to perfect amphibious warfare doctrines. In April-May 1938, this was Fleet Problem XIX, off Hawaii, but by January 1939 she transited by Panama and sailed to the Caribbean, to take part in Fleet Problem XX in the Atlantic. She was refitted at Norfolk Navy Yard and was back to San Francisco with Quincy for a goodwill tour of South America until 10 May under command of Rear Admiral Husband E. Kimmel. They were both battled by a storm off the strait of Magellan on 14–15 May and were back to Norfolk in 6 June. The American heavy cruiser was on east coast during the summer of 1939, carryong President Franklin Delano Roosevelt to Campobello Island in the New Brunswick.

When WW2 broke out, Tuscaloosa was in Norfolk and soon joined the the Neutrality Patrols alternated with training in October in the Caribbean and Virginia Capes in November, until December.She tracked German merchantmen as 85 German were signalled off the American coast. One of these tempting prizes was the Norddeutsche Lloyd liner Columbus. She was caught in the West Indies, at Veracruz in Mexico, fuelling to depart for home on 14 December 1939 when she was framed by seven USN destroyers, and Tuscaloosa joined in on 16 December. On 19 December, the liner was captured by the British destroyer HMS Hyperion but German Captain Dahne quickly scuttled his ship. Tuscaloosa embarked 576 men, boys and women from the ship and disembarked them at Ellis Island on 20 December. As the year 1940 was going to start, tuscaloosa remained in Norfolk, before departing on 11 January for the West Indies with USS San Francisco and other vessels of Battleship Division 5, making it in Culebra on 16 January, then proceeding to Guantánamo Bay, participated in fleet exercises until 27 January. Back in Norfolk she entered drydock to be refitted as a Presidential flagship. She was back at Guantánamo on the 7 February, then headed for Pensacola and embarked President Roosevelt and his guests. She was escorted by the destroyers USS Jouett and Lang and headed for the west coast of Central America and was back to disenbark the President at Pensacola before joining New York NyD for a three-month overhaul. After May, she went on patrolling in the Caribbean and Bermuda until the fall of 1940.

On 3 December 1940 she was sent to Miami to embark President Roosevelt for a cruise of inspection of various base obtained from Britain in the “destroyers for bases” deal, a 99-year lease including Kingston, Jamaica, Santa Lucia, Antigua and the Bahamas. Roosevelt was disembarked at Charleston and Tuscaloosa sailed for Norfolk in December, embarking en route Admiral William D. Leahy, the newly designated Ambassador to Vichy France bound to Portugal. At the time, to show her neutrality, the cruiser had large stars and stripes painted large on Turrets 2 and 3 rooftops, plus a very large flag flying. She was escorted by the destroyers USS Upshur and Madison.

USS Tuscaloosa Scapa in Flow, 1942

After disembarking the Ambassador she was back to Norfolk on 11 January 1941. Between Maneuvers and exercises she was into March she was sent to the new base at Bermuda on 8 April, meeting here USS Ranger, Wichita, Kearny, and Livermore. Sh patrolled shipping lanes up to the North Atlantic and was signalled the Prinz Eugen broke out into the Atlantic in May. With news of KMS Bismarck’s escape USS Tuscaloosa sailed west but arrive too late. On 8 August, she departed Bermuda for Newfoundland, carrying H. Arnold (Army Air Corps) and Rear Admiral Richmond K. Turner and Capt. Forrest Sherman to join USS Augusta (with the president on board) off NyC and sailed to NS Argentia in Newfoundland. There was an important meeting there, the HMS Prince of Wales bringing Prime Minister Winston Churchill. The reunion decided on signing the “Atlantic Charter”. In August, USS Tuscaloosa carried Secretary of State Sumner Welles to Portland in Maine and in September, escorted a troop convoy to Iceland. She joined the battleships Idaho, Mississippi, and New Mexico, USS Wichita and two divisions of destroyers under Rear Admiral Robert C. Giffen, to Hvalfjörður.

USS Tuscaloosa October 1942

Northern route convoys

Tuscaloosa there was on alert for any possible sortie of the German battleship KMS Tirpitz. On 7 December 1941, she was still there, and only departed on 6 January 1942 for training mission through the Denmark Strait. She was sent to Boston for an overhaul until 20 February. She later trained at Casco Bay and joined Task Group 39.1 (TG 39.1), Rear Admiral John W. Wilcox, Jr., flagship USS Washington. The Task Group sortied from Casco Bay bound for Scapa Flow. On 27 March however the Rear Admiral suffered was washed overboard and Rear Admiral Giffen assumed command. Tuscaloosa was in Scapa on 4 April 1942.

She was briefed by onboard British signals and liaison team and used to train with the British Home Fleet. Her newt duty would be the protection of convoys to Murmansk. By mid-August 1942 she departed with two destroyers plus one British, and was spotted by a German reconnaissance plane en route. The task force changed course and was joined later by two more British destroyers and then a Russian escort for the Kola Inlet. he cruiser disembarked her precious cargo, took on fuel and 243 passengers, survivors of sunken ships of previous convoys, notably from PQ 17. She was back to Seidisfjord and proceeded to the River Clyde to disembarked the passengers. She was then detached from the Home Fleet stopped at the Hvalfjord and proceeded to the East Coast for a long overhaul.

Mediterranean: Operation Torch

In November 1942 she was prepared for Operation Torch. Tuscaloosa and Wichita joined USS Massachusetts off casablanca and the carrier USS Ranger. She fired her guns helped by her own scout planes shorewards on French Army’s defensive positions. At some point she was framed by the unfinished battleship Jean Bart firing from the harbour, and later the shore batteries at Table d’Aukasha and El Hank. All three were silenced, as well as several French Air Force airfields. However USS Tuscaloosa was near-missed by a torpedo volley from a Vichy French submarine and was detached to replenish ammunition offshore, later remaining offshore in support before heading for the US East Coast for another overhaul. After this, she returned to cover convoys bound for North Africa until the Africa Korps and Italian forces remaining were cornered in northern Tunisia, surrendering to the Allies in May 1943.

Norway & Iceland

Tuscaloosa was training to take part of a task force fast, mobile, and ready to catch any German surface which could slip through the Allied blockade. By late May, she escorted RMS Queen Mary, with Prime Minister Churchill to New York City. She then proceeded to Boston Navy Yard for short overhaul, and escorted RMS Queen Elizabeth to Halifax in Nova Scotia, then met USS Ranger and was back to Scapa Flow for more sorties in the North Sea in the hope of drawing Norway’s Germans ships into a decisive battle. She later covered Ranger as she launched air strikes against Bodø (Operation Leader) until 6 October 1943.

The Germans ultimately attempted a sortie to Spitzbergen, with Tirpitz and other heavy units shelling the base before retiring, but Tuscaloosa was part of the relief expedition to the battered station as part of Force One with two LCV(P) and cargo on board, covered by HMS Anson, Norfolk and the carrier Ranger plus six destroyers. This force arrived the 19 fielding a party of 160 men on shore. She later refuelled at Seidisfjord and proceeded to the Clyde to disembark the garrison’s survivors. After another sweep in the north sea she was back to New York for a major overhaul in December until February 1944.

D-Day

After fleet exercises and shore bombardment practice she received at the Boston Navy Yard a radio intelligence and electronic countermeasures gear, and later carried Rear Admiral Morton L. Deyo, the Commander of CruDiv 7, heading for the Clyde, staying mostly inactive prior to D-Day. She made more shore bombardment practice and liaison with the allied fleet, her aviation exchanged for British Supermarine Spitfires, training for spotting. On 3 June 1944, USS Tuscaloosa was part of Task Force 125 and arrived at 05:50 on 6 June, off the Normandy coast, firing first with her main guns and then her secondary 5 inches. She silenced the Fort of Tatihou island in the Seine Bay and battered other coast defense batteries, and artillery positions or troop concentrations signalled both by air spotters and ground fire control parties. These planes were Spitfire VBs and Seafire IIIs. However as German counter-fire was more precise, the cruiser took evasive action.

On 9 June USS Tuscaloosa was back to Plymouth to resupply ammunition and was back on the 11 off the Saint-Marcouf island, remaining on station until 21 June, for on call support, before going back to Britain. On 26 June, she supported the assault against Cherbourg, duelling with German shore batteries. After the situation was stabilized, USS Tuscaloosa steamed from Belfast to the Mediterranean. There, she was prepared for the second large French landing, Operation Anvil-Dragoon.

Operation Anvil-Dragoon In August 1944, Tuscaloosa was part of the force based at Palermo whch arrived on 13 August off the southern French coast called the “riviera”. On the 14th, at 06:35 she opened fire until troops assaulted the beaches at 08:00 and the proceeded to find other targets of opportunity, soon silencing a pillbox at the St. Raphael breakwater, firing her 8 in (200 mm) rounds at very close range. Later the fired on a field battery reported by air spotters. She will also covered the right flank of the Army’s advance to the Italian frontier engaging more German shore batteries and fending off rare air attacks by Junkers Ju 88s and Dornier Do 217s, using radar-controlled glider bombs. These were defeated by radar counter-measures and jamming. These attacks by night and day were unsuccessful. By September 1944 the Allies were strongly installed in western and southern France and USS Tuscaloosa was back at the Philadelphia Navy Yard for an overhaul.

Tuscaloosa in the Pacific:

She then proceeded to the Pacific Fleet, stopping at San Diego, then Pearl Harbor, making exercises and proceeding to Ulithi to join the 3rd Fleet, in January 1945. Her first mission was to be part of the bombardment force off Iwo Jima. She arrived at dawn on 16 February and three days later pounded Japanese positions inland. She went on providing on demand precision fire and and illumination bu night from 19 February to 14 March. Back to Ulithi for supplies she joined Task Force 54 (TF 54), for the next great operation, at Okinawa. She arrived ans started shelling on 25 March, on targets pointed out by aerial reconnaissance and stood on duty for the entire campaign, repelling kamikazes, splashing two before departing from Okinawa on 28 June, for Leyte Gulf reporting to the Commander of the 7th Fleet for duty. She had only six weeks left of shore gunnery and AA cover before Japan surrendered. On 27 August she departed Subic Bay for the Korean and Manchurian waters, Tsingtao, Dairen, Port Arthur, Chefoo, Taku, Weihaiwei and Chinwangtao.

She stopped at Jinsen (Incheon) in Korea on 8 September, supporting Marines landings and staying there 22 days. On 30 September 1945, she headed for Taku in China and another marines landing, then Chefoo in October stopping at Jinsen fir supplies. There, she would be an observers of the Chinese civil war as Chefoo fell to the communists on 13 October. She departed newt to Shanghai taking on board 214 army and 118 navy passengers. This was her first “Magic Carpet” mission, and she arrived in Hawaii on 26 November, then San Francisco on 4 December 1945. She was sent in the South Pacific and arrived at Nouméa, New Caledonia and then embarked troops at Guadalcanal, Russell Islands and back to Nouméa on 31 December to 1st January 1946. Back to Pearl she went home via San Francisco before being placed out of commission at Philadelphia, on 13 February 1946. stricken on 1 March 1959 she was sold on 25 June for scrap.

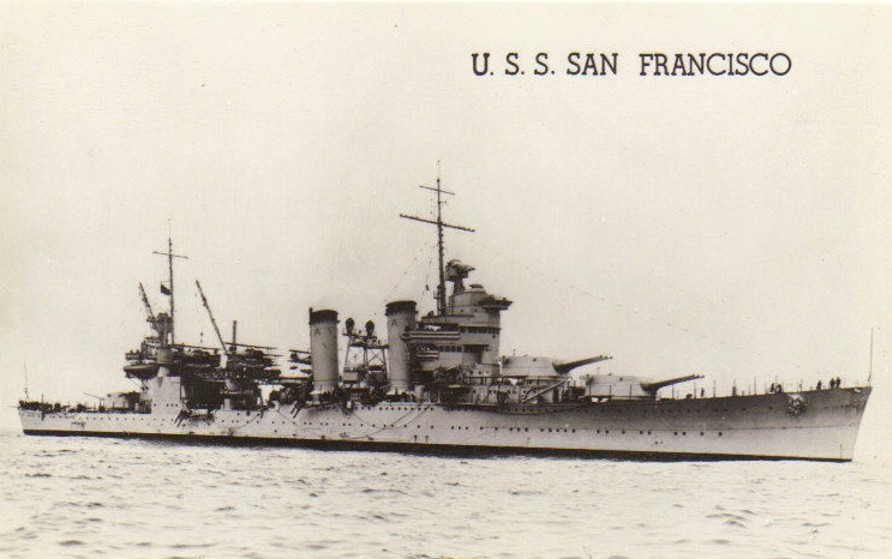

USS San Francisco – CA-38

USS San Francisco before the war. Scr .history.navy.mil.

After entering service, USS San Francisco made an extensive shakedown cruise off Mexico, then in Hawaiian waters and up to British Columbia, and back to the Panama Canal Zone before her refit at Mare Island Navy Yard. She was converted as a flagship and was back in service in February 1935, joining Cruiser Division 6 (Crudiv 6) at San Diego. She participated in May to Fleet Problem XVI, then the northwest coast for fleet tactics and Alaska in the summer, back to California and the eastern Pacific coast. In January 1939 she participated in Fleet Problem XX and became in march flagship of CruDiv 7, starting a tour of South American ports, until June. When was broke out, she was based in Norfolk as part of the Neutrality Patrol force, also carrying freight and passengers to San Juan in Puerto Rico. She was in Norfolk until January 1940, and relieved Wichita in Guantanamo Bay.

In late February she transited Panama and headed for San Pedro base, and then Pearl Harbor in March, with CruDiv 6. In May 1940, she was overhauled in Puget Sound Navy Yard, received four additional 3 in (76 mm) AA guns. In May 1941 she was the flagship of CruDiv 6 and trained between Long Beach and Hawaii, arriving on 27 August. In October she was overhauled in Pearl Harbor, scheduled for completion on 25 December, but the Japanese attack proceeded earlier.

On 7 December indeed, the cruiser was awaiting docking, with a heavily fouled bottom and tired powerplant in great need of care. Her main and secondary guns ammunitions were not on board, all locked up in storage ashore while her 3 in (76 mm) just had be removed removed to fit four quad 1.1 in (28 mm) guns, still no installed. She only had her .50 in (12.7 mm) machine guns left, also overhauled, and ammo locked away. So when Japanese planes arrived, her crew this sunday only had small arms and two .30 in (7.6 mm) machine guns on board, with many officers and men absent. As the press later said, it was Off-duty signalman Ed Ifkin which allegedly first signalled the Japanese aicraft over the base. San Francisco’s crew did not stayed idle, securing the ship’s watertightness and arming themselves. Some went onboard the nearby USS New Orleans to help man the operational AA batteries while the other climbed into the bridge for better positions and fired with rifles and light machine guns while .50 in (12.7 mm) ammo was transferred from ashore. But they could do little. The cruiser was totally spared by the attack and found itself seaworthy and combat-ready as the harbour was in shambles.

CA 38, date unknown. Src: Navsource.

She left Pearl, dropping its maintenance for more necessary repairs of other ships and sailed with TF 14 to Wake Island, which fell on 23 December, and her force was diverted to Midway, reinforcing it instead, before returning to Pearl Harbor. On 8 January 1942 the cruiser joined TF 8 and covered transports to Tutuila in Samoa, joined by Task Force 17. Next came raids on the Gilbert and Marshall Islands. She went later northeast of the Solomon Islands, but was attacked en route by two waves of Mitsubishi G4M “Betty” bombers, sixteen downed, but the force aborted the raid. USS San Francisco protected TF 11 flagship, USS Lexington operating in New Guinea with TF 17, the cruiser loosing one her scout planes, later recovered. On 9–10 March, aerial raids were launched on Salamaua and Lae. She was back to Pearl Harbor on 26 March 1942, heading for San Francisco to cover convoy 4093 and convoy PW 2076 (carrying the 37th Army Division) bound to Suva, and special force to Australia. She stopped at Auckland in New Zealand before arriving in Hawaii and Pearl Harbor on 29 June. With USS Laffey and Ballard she later escorted the convoy 4120 to the Fiji Islands and later joined the Solomon Islands Expeditionary Force for Operation Watchtower: the Guadalcanal-Tulagi offensive, starting at noon on 7 August. She provided cover there under command of Rear Admiral Norman Scott, TF 18, USS Francisco being used a flagship.

USS San Francisco under the Golden Gate bridge in December 1942.

On 3 September she refuelled at Nouméa in New Caledonia and was back to Guadalcanal, meeting there TF 17 (USS Hornet), refuelling at sea. TF 61, TF 17, and TF 18 began operations, when on 15 September USS Wasp was torpedoed and Admiral Scott took command of TF 18. USS San Francisco and Salt Lake City tried to tow the carrier, but fires went out of control and she was evacuated and torpedoed. On 17 September, USS San Francisco sailed with Juneau and five destroyers to join TF 17, protecting convoys. By 23 September she operated with Salt Lake City, Minneapolis, Chester, Boise, and Helena plus the Destroyer Squadron 12, a force named TF 64, to provide screening and support (Admiral Scott, flagship USS San Francisco). The force was sent to the New Hebrides and soon participated in the Battle of Cape Esperance, a strong test for the cruiser.

On 7 October 1942, TF 64 was amputated from Chester and Minneapolis sent to Espiritu Santo. On 11 October, the force was off Rennel Island, trying to intercept a Japanese relief force made of two cruisers and six destroyers. They came from Buin-Faisi, Bougainville Island and approached from the north to Savo Island, in “The Slot”. It was 23:30, about 6 mi (9.7 km) northwest of Savo when spotted, and the battle started 15 min. later. After some initial confusion because of the fear of friendly fire, battle raged on past midnight, until surviving Japanese vessels retired toward the Shortland Islands while USS Salt Lake City, Boise and the destroyers Duncan and Farenholt has been damaged, Duncan later sinking. IJN Furutaka and a destroyer were sunk and two more destroyers the following day by aviation from Henderson Field. On 20 October USS San Francisco was back from Espiritu Santo for operations in the Guadalcanal campaign, assisting Chester hit by a torpedo, Helena later was hit too, while one missed USS San Francisco’s port beam. On 28 October, Admiral Scott left the heavy cruiser to transfer his mark to USS Atlanta. He was replaced on 30 October by Rear Admiral Daniel J. Callaghan as the head of Task Group 64.4 (TG 64.4) and future TF 65 with reinforcements.

USS San Francisco in the background, and transport SS President Jackson during the air attack of 12 November 1942.

On 31 October 1942, TF 65 sailed from Espiritu Santo to the Solomon Islands, covering troop landings on Guadalcanal, shelling Kokumbona and Koli Point and back on 8 November. Two days later, USS San Francisco became flagship of TG 67.4, and was spotted before noon by a Japanese reconnaissance plane until Lunga Point, on 12 November. At 14:08, 21 Japanese planes attacked the formation,

USS San Francisco took a near-hit from an aerial torpedo at her starboard quarter while the carrier plane, hit, crashed into her control structure aft, killing 15 and wounding 29. The cruiser’s secondary command post was burned out but later repaired while her aft AA director and radar destroyed as well as three 20 mm guns. Wounded men were transferred to President Jackson, and soon after a surface force was reported. The covering force escorted the transports out and later returned, comprising the USS Portland, Atlanta, Helena, Juneau, and eight destroyers. They were entering Lengo Channel at 01:25 on 13 November, spotting the IJN surface force some 27,000 yd (25,000 m) to the northwest. Rear Admiral Callaghan’s task group maneuvered for interception. This became the first Naval Battle of Guadalcanal.

USS San Francisco fired first on an unidentified enemy cruiser at onmy 3,400 m starboard, and a small cruiser or large destroyer at 3,000 m until targeting Atlanta by mistake. The damage of this friendly fire was quite fierce: Admiral Scott and the bridge crew was killed and San Francisco soon realized the friendly fire, and ceased fire but USS Atlanta would later sank while San Francisco duelled with IJN Hiei at very close range, only 2,200 yd (2,000 m) and around 02:00, the heavy cruiser shofted attention on IJN Kirishima while taking gunfire from IJN Nagara on starboard, near-missed by a passing destroyer off her bow to port. San Francisco duelled with her 5 in with the the destroyer loosing nearly all her battery in the process. She swung left, still sending 8-in volleys on both IJN battlecruisers bu soon took a direct hit on her navigation bridge. All officers except the communication officer (Bruce McCandless) were instantly killed or wounded.

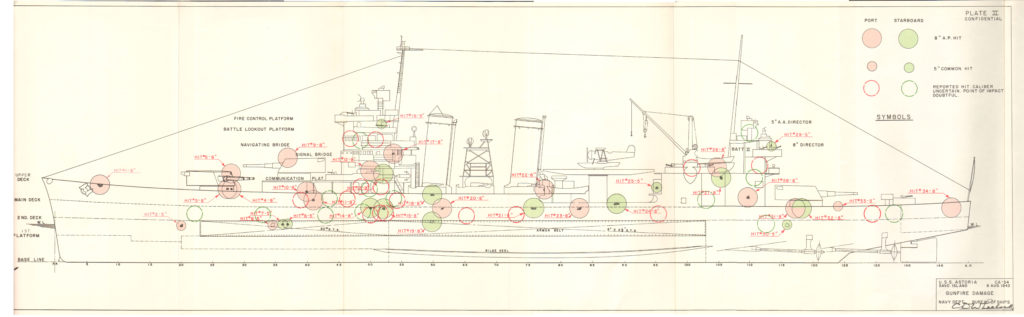

Lt. Cdr Herbert E. Schonland took command but could do little at this point, ordering McCandless to stay in the command post 2 to control Steering and the engine until it out of commission by a direct hit. Later orders came from conning tower, soon hit on starboard, communications ceased, control was lost as the Japanese ceased fired, while San Francisco withdrew eastward, on the north coast of Guadalcanal. Rear Admiral Daniel J. Callaghan, Captain Cassin Young and 77 sailors had been killed during the fight, 105 wounded, 7 missing while the cruiser took 45 hits. No structural damage was proved fatal to the ship and none penetrated below the waterline while control parties extinguished 22 fires. This is a strong tertimony to both the strenght of the cruiser’s protection and crew’s skills. USS San Francisco survived indeed the combined fire of two battlecruisers (modernized as fast battleships), a cruiser and a destroyer.

San Francisco later met Helena and Juneau, passed though the Sealark Channel and sailed to Espiritu Santo. There, the heavy cruiser was temporarily repaired. Meawnhile, USS Juneau has been torpedoed by I-26 and literally disintegrated, San Francisco receiving large fragments from her blast, killing one man. There were about 100+ survivors but they were stranded at sea eight days and only ten survived shark attacks and time spent in water. Back in harbour, the cruiser received a Presidential Unit Citation and sailed on 18 November to Nouméa and the United States, arriving in her namesake city on 11 December, extensively repaired and modernized at Mare Island Naval Shipyard.

After completion and post-refit trials, she departed On 26 February 1943 for the South Pacific, escorting convoy PW 2211 along the way Nouméa. She stopped at Efate and arrived in Pearl by the mi-April, to sail for the Aleutian Islands, North Pacific Force (TF 16) and Alaska, Kuluk Bay and Adak Island. There she was prepared for the reconquest of the Aleutians, covered the assault and occupation of Attu and Kiska in July 1943, before going back for escort duties and joined TF 14. She departed Pearl on 29 September with TU 14.2.1 to raid Wake Island in October, making to two runs and back to Pearl Harbor. On 20 November she took part in the raid on Makin, shelled Betio and patrolled west of Makin before joining TG 50.1 with the Essex-class carriers Yorktown(ii), Lexington(ii), Cowpens and five cruisers plus six destroyers to the Marshall Islands. She shelled Kwajalein in covered the fleet in December, fending off Japanese aerial attacks, notably three torpedo bombers which splashed near her, but the strafing left one dead and 22 wounded on the decks. USS Lexington was torpedoed during the night and the Task force veered north-west and went back to Pearl Harbor.

USS San Francisco Kuluk Bay Adak Island April 1943

On 22 January 1944, USS San Francisco carried a raid in the Marshalls with TF 52, shelled installations on Maloelap to prepare the main assault on Kwajalein. The cruiser was there on 31 January and opened fire on the morning, stopping 50 min. later then resumed firing at Berlin and Beverly islands all the day, and later Bennett Island, and next, pre-landing barrages and support fire during the assault on Burton, Berlin, and Beverly islands. On 8 February she was sent to Majuro to meet TF 58, fast carrier task force. He own unit was called TG 58.2/ She helped clear Majuro lagoon as Operation Hailstone took place. USS Intrepid was torpedoed later and the cruiser assisted her eastward.

On 19 February San Francisco was back to Majuro and six days after was back to Hawaii, but after supply was back on 20 March to Majuro and on 22 March was sent to the Western Carolines, planes assaulting the Palaus and Woleai and back to Majuro lagoon on 6 April. The force newt was sent to New Guinea and in 21–28 April bring cover for the landings at Hollandia. Another raid in the Carolines and Truk folowed, and by 30 April, USS San Francisco joined eight other cruisers to shell Satawan, then met back TG 58.2 and headed for the Marshalls. This unit was relocated to Kwajalein June 1944 to take part in the Saipan invasion force, starting the artillery preparation on 14 June on Tinian, and then provided close support. By 16 June she was dispatched to CruDiv 9 to shell Guam and back to Saipan.

On 19 June, this was the Battle of the Philippine Sea. San francisco was framed by bombs in aerial attacks and dive bombers returned for another attack. By 20 June, she chased the Japanese force, the returned to Saipan and Guam in July for more shellings, on Agat and Agana. By 18 July, she had made a refuelling trip on Saipan and back. She supported Marines streaming Agat beaches and shelled Orote Point. On 30 July she stopped at Eniwetok and Pearl Harbor bound for San Francisco, overhauled from August to October, arriving in 21 November 1944 at Ulithi, still as flagship of CruDiv 6. On 10 December she joined TG 38.1 for strikes against Luzon, while her spotter planes went on making antisubmarine patrols and rescue. The force then met TG 30.17which carried supplies, interrupted by a typhoon and mater searched for survivors of three destroyers sunk during it. On 20 December, as part of TF 38 she operated off Luzon until sailing to Ulithi. Operations had been cut short by heavy weather.

USS San Francisco_off the Korean coast 28 September 1945

In early January, she shelled Formosa and then Luzon, heading through the Bashi Channel for a rampage against all Japanese targets of opportunity in the South China Sea and Indochina. by mid-January, the force attacked Hong Kong, Amoy and Swatow, then passed through Luzon Strait to complete operations against Formosa, repelling air attacks which damaged USS Langley and Ticonderoga, the force next proceeding to the Ryukyu Islands and south to the Western Carolines. Crews rested and supplies were made from 26 January to 10 February, conducting in mid-February air raids on central Honshū. Later, this was the Bonin Islands, and Iwo Jima. USS San Francisco stayed for fire support until 23 February and then shelled on 25 February, Tokyo but failed to shell Nagoya because of heavy weather, before the force was sent back to Ulithi. In March 1945 the cruiser was attached to Task Force 54 for Okinawa. She shelled Kerama Retto before moving to support the main landings while silencing batteries oon the Aka, Keruma, Zamami, and Yakabi Islands. Next, ait attacked started, and she was moved to support sector 5 west of Naha, retiring for supply at Kerama Retto. He crew downed a Nakajima B6N “Jill” and later a Nakajima B5N “Kate” torpedo bomber, also repelling kamikaze, one, hit, closely splashing 50 yd (46 m) off the starboard bow. She resumed her fire support with TF 51 on the east coast of Okinawa and swapped for TF 54 on the west coast. She downed a Aichi D3A “Val” dive bomber later. By mid-April 1945, she was back with TF 51 on the east coast and resupplied at Kerama Retto, returning woth TF 54, providing night illumination as suicide-swimmers and Shinyo boats has been spotted, destroying at least two.

San Francisco near Korea in 1945. She shelled the Naha and Machinate air fields and anchored in Nakagusuku Wan for more support in the southern sector, until 24 April, still shelling Naha and sailed back to Ulithi.

She was back on 13 May to Okinawa, Nakagusuku Wan for assisting the clearing of the southern Okinawa area, receiving targets by radios of the 96th Infantry Division, southeast of Yonabaru. She also shelled Kutaka Shima, until she ran of ammunitions but provided AA support on 25 May during one of the largest and most massive air attack in Nakagusuku Wan. She also covered the 77th Infantry Division, resupplied at Kerama Retto, then covered operations on west Okinawa and the 1st and 6th Marine Divisions. By 21 June, she met TG 32.15 southeast of Okinawa and in July, protected the eastern anchorage. By mid-August as she was prepared for Operation Olympic, however, the war ended and the cruiser was prepared for occupation. The war was over for the cruiser, one of the most successful of the USN history: She earned 17 battle stars, making her the third most decorated USN ship of the war. Statistics showed she travelled 480,000 km, crossing the equator 24 times and fired 11,022 8-in shells and downed at least a dozen aircraft while her crew suffered 267 combat casualties. On 28 August 1945 she left Subic Bay for the Chinese coast, covered minesweepers and anchored at Inchon, participating in a Gulf of Pohai operation. Onboard, Rear Admiral Jerauld Wright, CruDiv 6 commander accepted the surrender of Japanese naval forces in Korea. She headed then for home, a job well done, in November at San Francisco and then Philadelphia where she was decomm. on 10 February, but still part of the Atlantic Reserve Fleet until March 1959, struck and sold for scrap.

USS Quincy – CA-39

USS Quincy, second ship of the name, was laid down by Bethlehem Shipbuilding Corporation’s Fore River Shipyard in her namesake city of the Massachusetts on 15 November 1933, and launched on 19 June 1935, sponsored by the wife Adams-Morgan, wife of the shipyard mogul Henry S. Morgan. She sailed out to be commissioned in Boston, on 9 June 1936. Captain William Faulkner Amsden took command. With USS Vincennes she was a slightly improved version of the New Orleans-class design, denominated CA-39. He wartime carrer was relatively short and brutal, but she earned a battle star.

She was assigned to Cruiser Division 8 in the Atlantic Fleet, and sailed to the Mediterranean on 20 July 1936 as the civil war erupted in Spain, trying to protect and embark US citizens. She went through the Gibraltar strait, bound to Málaga on 27 July. She operated with the international rescue fleet also including the three German “pocket battleships”. She evacuated 490 refugees, carried to Marseille and Villefranche in France, replaced by USS Raleigh in September. She was in Boston Navy Yard in October for a refit and final acceptance trials, in 15–18 March 1937, making for a very late full commission. On 12 April she join CruDiv 7 and headed for the Pacific, arriving in Pearl Harbor on 10 May. She participated in very large and realistic tactical exercises in 1937–1938, notably Fleet Problem XIX. After a shot refit at Mare Island Navy Yard, she operated off San Clemente in California, before going back in the Atlantic in January 1939. There, she made more exercises in the Caribbean, and Fleet Problem XX in 13–26 February followed from 10 April by a South American goodwill tour and spent the remainder of 1939 on patrol in the North Atlantic. She was overhauled in Norfolk in May 1940 then visited South America again and back in September, followed by reserve training cruises until Christmas. She took part in landing force exercises off Culebra Island in Puerto Rico by February-April 1941. Then she joined Task Force 2, USS Wasp to enforce the US neutrality untom 6 June. She then was detached to USS Yorktown (TF 28) and was back home on 14 July.

USS Quincy off Nouméa, New Caledonia, 3 August 1942. Colorized by Irootoko Jr.

On 28 July, she departed with TF 16 for the occupation of Iceland and patrolled the denmark strait on 21–24 September. She escoted a convoy from Newfoundland and then departed for Cape Town in South Africa, stopping at Trinidad, to escort another convoy and back to Trinidad. The year 1942 started with USS Quincy in Icelandic waters, on convoy duty. She operated with TF 15 until March, and made an overhaul at New York Navy Yard until May 1942. As she was needed in the Pacific, the cruiser went through the Panama Canal in June and joined TF 18 as flagship (Rear Admiral Norman R. Scott). She then departed for the South Pacific in July 1942, with the fleet assembled for the invasion of Guadalcanal. Preliminary actions of USS Quincy including shelling installations and an oil depot at Lunga Point and later she provided close fire support for the Marines.

USS Quincy in action off Guadalcanal in August 1942.

On 9 August, she was sailing between Florida and Savo Islands past midnight when USS Quincy was surprised by a large Japanese naval force: This was the Battle of Savo Island, a nightmare of searchlights and withering close range guns and torpedo fire by masters of night attacks. Quincy, USS Astoria and Vincennes’s lookouts previous saw aircraft flares nearby and were distracted from the real attack, which fell on them, with captain, Samuel N. Moore ordering fire, catching the crews unready. Soon after there was a crossfire between Aoba, Furutaka, and Tenryū. USS Quincy was soon afire and the captain ordered to turn to charge towards the Japanese column but as she did, the hull was struck by two torpedo hits, launched by Tenryū. The damage was quite extensive, the ship started to list, still burning furiously, but the cruiser managed to fire a few salvos. IJN Chōkai’s chart room was hit and short missed Admiral Mikawa. At 02:10, Quincy’s bridge crew and the captain were all dead. Another torpedo struck the cruiser at 02:16, from Aoba while all guns were shut. The assistant gunnery officer soon found what remained of the bridge, devastated, all communications broken. The sold survivor was the signalman. After taking so much punishment the Japanese retired, leaving behind 370 dead and 167 wounded ans Quincy sank bow first, at 02:38, the first to go in the infamous “Ironbottom Sound”. Lucky survivors managed to get ashore. The cruiser’s wreck was rediscovered and explored by Robert Ballard in 1992 below 2,000 feet (610 m) of water, her bow missing and both forward turrets trained to starboard, showing a jammed gun and another burst. The bridge showed extensive damage while the hangar collapsed and her stern was bent upwards because of implosions. A commemorating plaque was left after a ceremony.

USS Vincennes – CA-44

USS Vincennes in the Panama canal in 1938