The twisted origins of the first Japanese Ironclad

The “ship with five lives”

Kotetsu was quite unique as being an ironclad changing at least five or six times names and flags during her 20-years long career. She was planned for the Confederate navy under cover, first laid down as the Egyptian ship “Sphinx”, then during construction as the Danish “Stærkodder” to fight Prussia, transferred after completion to the Condeferacy as USS Stonewall, making a single sortie before the capitulation, being purchased by the Cuban Spanish fleet, then to the US Navy, and resold to a Japanese Faction in the Boshin War, the Tokugawa Shogunate. From 1871 she became IJN Azuma, the first Imperial Japanese ironclad, a flag under which she served until 1888.

CSS Sphinx/Stonewall (1863-65)

Soon after the start of the American Civil War, the Confederate Navy planned to either convert and acquire ironclads ships they knew could break the Union blockade created since the start of hostilities. The ex Union Frigate Merrimack was being converted, and at the same time, a commission was sent in Europe to order one or several ironclad vessels.

In June 1863 John Slidell, Confederate commissioner to France asked Emperor Napoleon III in a private audience if it would be possible to build an ironclad in France. However this, for a recognized belligerent was illegal under French law. Slidell and his agent James D. Bulloch however would find simpathy from the Emperor of France, which had the time had many personal and business connections in Souther States. They were confident he would be able to circumvent these laws. Eventually Negociations succeeded with Arman Bros. Yards in Bordeaux (SW France), with the official sanction of Emperor Napoleon III. The ironclad ram was built for the Confederate Navy, but under cover of a sell to Egypt at first as “Sphinx”. Napoleon made clear their destination would remain a secret.

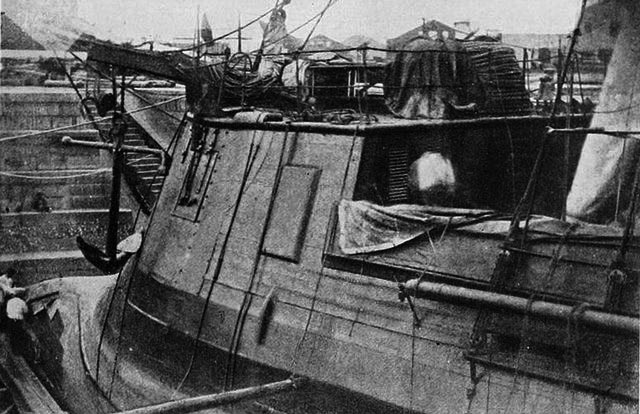

View of the Sphinx in construction in Bordeaux, forward forecastle turret.

In July 1863, Bulloch signed a contract with Lucien Arman at the head of the Bordeaux-based yard, a French shipbuilder which was recommended due to its personal ties with Napoleon III. The initial plan was even to build not a single, but a pair of ironclad rams, each capable of breaking the blockade. To avoid suspicion, their guns were manufactured separately without informations about their destination. Both vessels were initially named “Cheops” and “Sphinx”, spreading rumors about a sell to the Egyptian Civilian Navy as trade and transport teamers, on which nobody enquired.

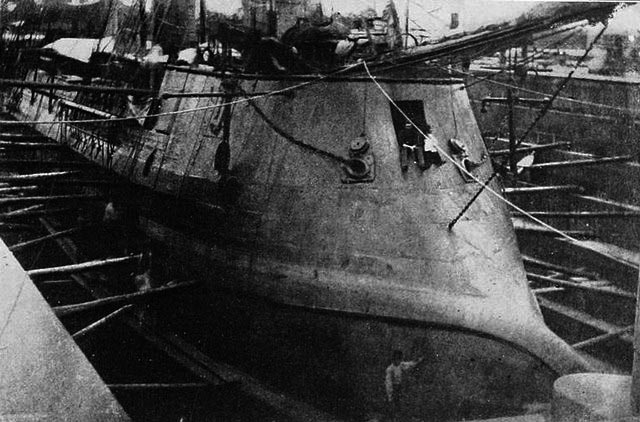

View of the Sphinx in construction in Bordeaux: The ram bow and forward gun port.

However in 1863 the white house made an official warning not to sell any armaments to the Confederacy under threats of ending displomatic relations. In fact, the Arman shipyard clerk betrayed his boss for personal divergences, and went straight into the U.S. Minister’s office in Paris with a wallet containing documents proving clearly Arman’s intention to arm the vessels, and that he was in contact with Confederate agents. It was not long before the US attaché, under orders fro the White House, rushed into Napoleon III’s office and had the French government blocking the sale. Arman however had a ackup plan. Rather than Egypt, now that the ships were known to be armed, he declared having new owners and that contracts had been signed both by Denmark and Prussia as the Second Schleswig War was looming. Cheops even had a document attesting she was to be sold to Prussia as Prinz Adalbert, and Sphinx to Denmark as “Stærkodder”, on 31 March 1864.

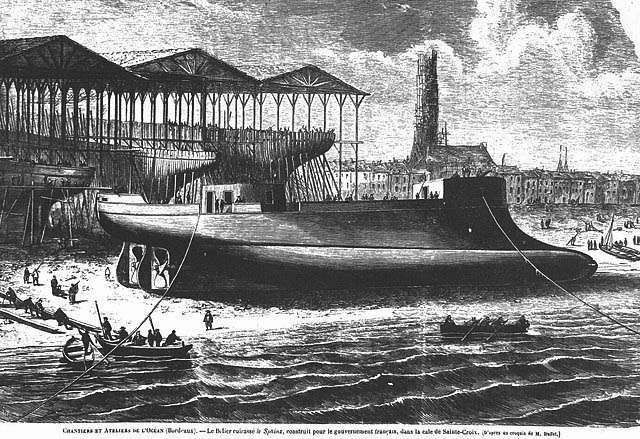

Launch of Sphinx in 1864

So the armoured ram steamer, already laid down in 1863 was now planned to be under cover of a sale to Denmark, by the time hard-pressed by Prussia for territorial concessions (which would end with the Second Schleswig War in 1864). This became the official version and credible cover, allowing the Yard to proceed with the construction without alarming more Union delegates in France. The true project however later was no longer to resell the vessel to the Confederacy. Arman really hoped a sell to Denmark. There was no undervover resell prospect not agreement between the Confederacy and Denmark, which really needed the ship.

The “Stærkodder”, as named from 31 March 1864, was eventually launched on 21 June 1864, completed in January 1865 and presented to Denmark. Danish sailors arrived in Bordeaux before her commission. She was completed and awaited commission, departing with this Danish crew from Bordeaux, for her shakedown cruise, on 21 June 1864. The crew tested her seaworthiness and performances. Meanwhile final negotiations for transfer were conducted between the Danish Naval Ministry and Arman.

The final price caused issues, the Danish Government notably asking compensation from the company for delays (as the war was now in full swing with Prussia), and problems reported during early trials. This led to and eventual completed breakdown of negociations on 30 October. This did not prevented nevertheless HDMS Stærkodder to be en route for Copenhagen, from 25 October. The Danish government refused to relinquish her, despite their apparent refusal, claiming confusion in regards to the negotiations and she indeed arrived in Copenhagen, on 10 November.

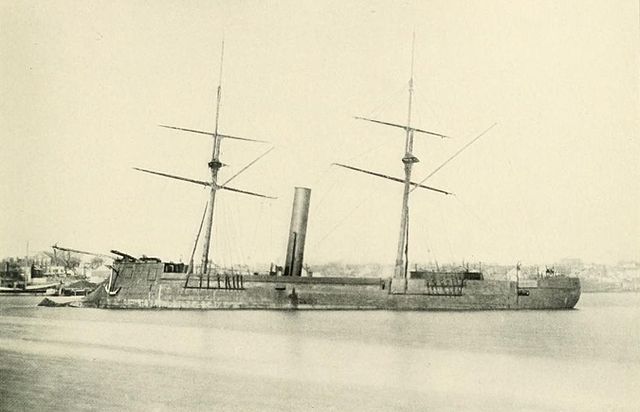

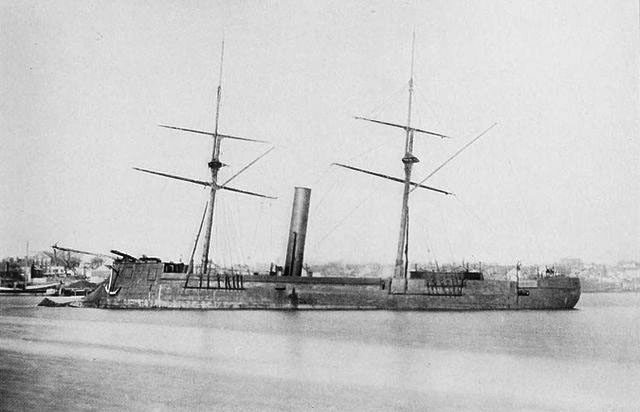

The ship as completed with her Danish crew

However the war ended on 30 October 1864 (This infortunate ship was a few days late in two wars as we will see). There, she was anchored in the Orlogsværftet dockyard in January 1865, pending her fate. It should be noted that SMS Prinz Adalbert was delivered effectively to Prussia and active until 1878. She will be seen in a standalone post, as noticealbly different.

However the position of Denmark at that stage was that they were not concerned by the non-belligence stance adopted by major powers, ship-builders like France or UK. The Danish Navy had a ship no longer needed as the war just ended, and authorities felt free to transfer her ownership via a newly signed contract to the Confederacy, whuich already had delegates in Stocckholm, hoping for precisely that decision. On 6 January 1865, she was renamed CSS Stonewall after the famous Confederate General Stonewall Jackson, and the flag was hoisted under the command of Lieutenant Thomas Jefferson Page.

However, the crew being still Danish (it was quite difficult to muster a confederate crew on site), she was still commanded by a Danish captain. This did not prevented her departure, after coaling, in order to cross the Atlantic. At that stage, although the situation was desperate in the south, but there was still time to attempt an offensive against the blockade. Thus, her short confederate career started (see later).

Design of Stonewall/Kotetsu

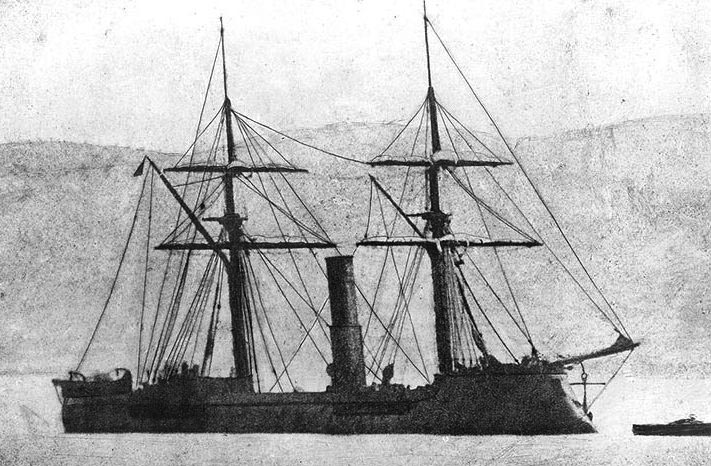

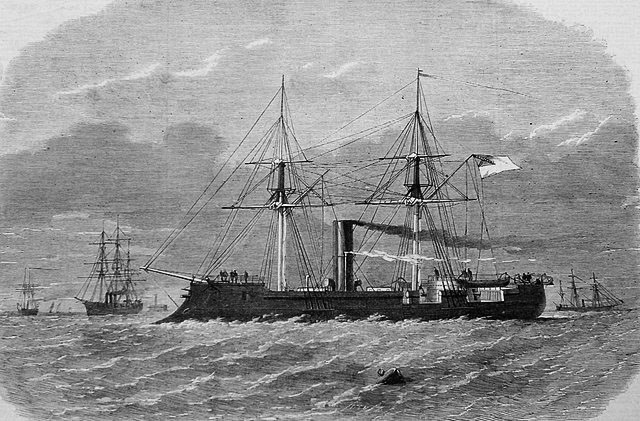

CSS Stonewall in 1865

Hull and construction details

Compared to France’s early ironclads, Stonewall was rather small. She was an ironclad ram, with a few heavy guns, but her ram was a primarly weapon alongside artillery. She displaced 1,390 long tons (1,410 t) for a lenght of 186 ft 9 in (56.9 m) overall, a beam of 32 ft 6 in (9.9 m) and draft of 14 ft 3 in (4.3 m).

Therefore her most distinctive feature was a promiment ram bow, protruding way well forward of her hull, perhaps seven meters (300 feets) from her forward forecastle deck. It was well reinforced too, with an upper thick reinforced iron piece, thick and large iron socket, and upper bow piece. The rest of the ship was merely wooden but the forecastle was protected by vertical iron plating 5.5 in (140 mm) thick, as the bow (2 or 4 in).

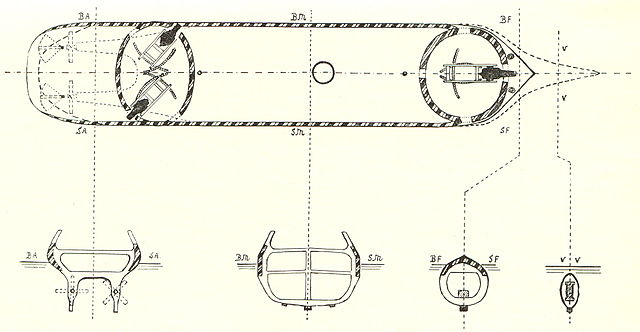

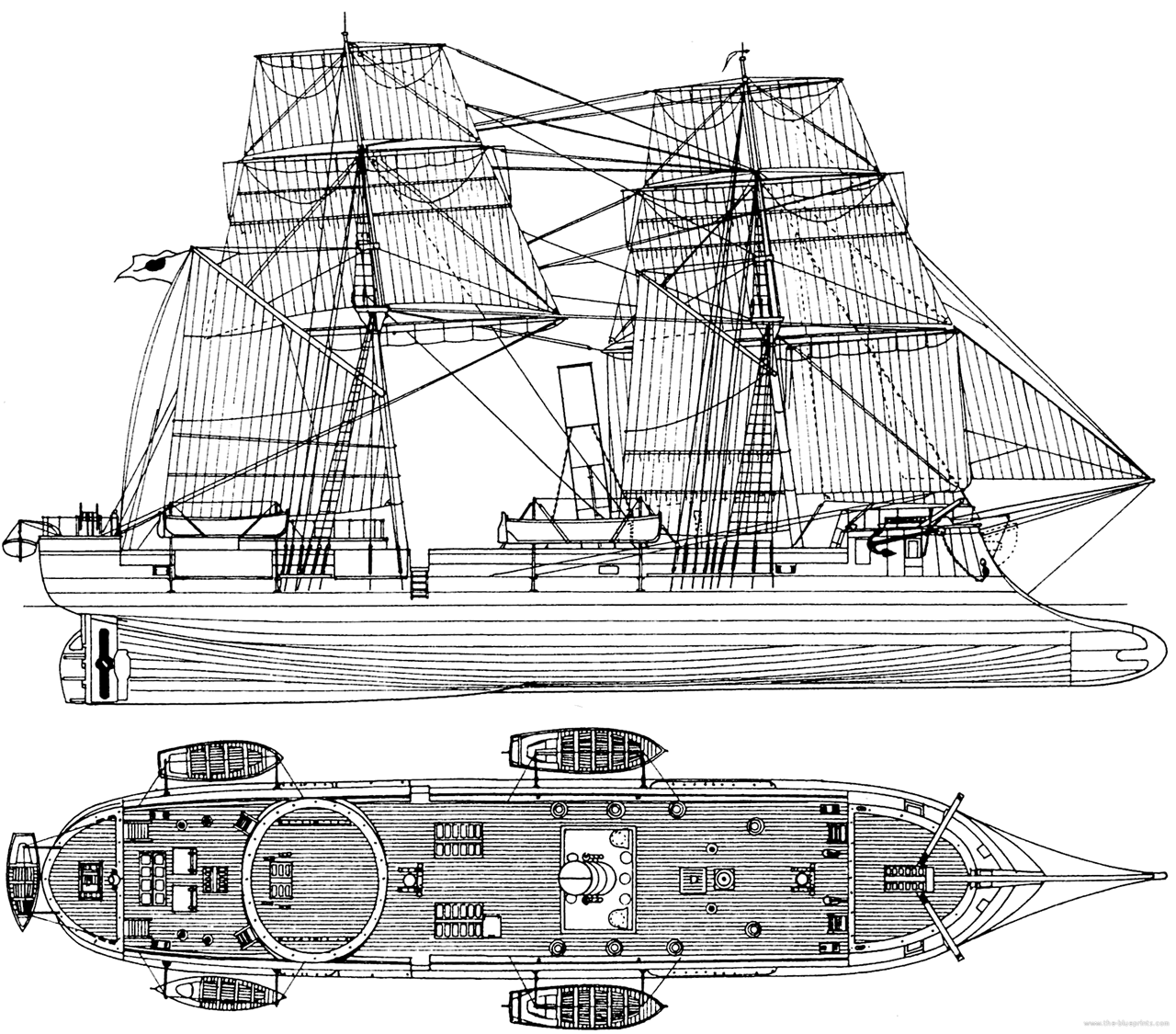

The deck plan, showing her gun arrangement

Her general silhouette was one of a brig, and she was rigged as such with a three square sails foremast, bowsprit and focsails, and aft mainmast with two squares and a trapezoid boom sail. The helm was located on the aft forecastle deck. She had an aft ovale platform for a traversing gun, while her single, tall funnel and access to her engine room was in the center. She carried also five service boats all in davits, two either side and one at the poop. As for the crew she carried 135 officers and sailors. The deck view shows also her “rectangle” shape, quite bulky, which made her poorly steerable and sluggish at the helm.

Armour

She had a waterline belt with 4.5 in (114 mm) plating backed by teak, the aft turret had 5.5 in (140 mm) walls, all in wrought iron. Her protective design scheme was intended to withstand 15-inch (381 mm) guns hits. Her armored belt extended 2.12 meters (6 ft 11 in) below the waterline, backed by 15 inches teak. Above it was 12 centimeters (4.7 in) amidships, tapering to 9 cm (3.5 in) towards the bow and stern. The was an upper strake of armor, 76 mm (3 in). The turret amidships was fitted with 4-inch (102 mm) plating.

Powerplant

Stonewall/Kōtetsu was propelled by 2 shafts direct-acting steam engines (HSE). These Mazeline horizontal two-cylinder single-expansion steam engines were mated to two Mazeline tubular coal-burning boilers, developing a total of 1,200 PS (1,184 ihp). Top speed as designed was 10.5 knots (19.4 km/h; 12.1 mph), but she reached a maximum speed of 10.8 knots (20.0 km/h; 12.4 mph) during her sea trials on 9 October 1864. Range was estimated to be 3,000 nmi (5,600 km; 3,500 mi). Coal consumption is not known with precision but she carried a a full load of 227 t (223 long tons) of coal.

Armament

Although this varied considerably during their career, both ships initially designed for the Confederacy were to carry a single Vickers 300 pdr (10 in (254 mm)) rifled muzzle-loading (RML) gun located in the bow turret, in a pivot mount. The latter was peculiar with its five bow ports. It is quite different from a regular Coles type turret, more a rotating platform for the gun and various ports to fire from. She also had two Vickers Armstrong 70 pdr (6.4 in (163 mm)) RML guns positioned in the oval fixed turret abaft the mainmast, one pivot mount on each broadside firing through two gun ports. This was modified later both by the Japanese and Prussians.

⚙ Kotetsu Specs 1865 |

|

| Dimensions | 56,9 m long, 9.9 m wide, 4,3 m draft |

| Displacement | 1,390 t. standard -1,500 t. Full Load |

| Propulsion | 2 shafts direct-acting steam, 2 boilers, 1,200 hp. |

| Speed | 10.5 knots (19.4 km/h; 12.1 mph) |

| Range | 3,000 nmi (5,600 km; 3,500 mi) |

| Armor | Waterline belt 4.5 in (114 mm), Turrets 5.5 in (140 mm) |

| Armament | 1x 300 pdr/10 in, 2x 70pdr/ 6.4 in RML |

| Crew | 600 |

The very short Career of CSS Stonewall

Stonewall (USNI archives)

After the sell to the Confederacy, from 6 January under Lieutenant Thomas Jefferson Page she was to cross the Atlantic, but Heavy weather in the nort sea forced her soon after departure to take refuge at Elsinore (eastern Denmark). She was at sea again when the weather subsided, heading south, for the French coast. There, she was load supplies, ammunition and gather more crewmen. Her commission as CSS Stonewall was completed at sea, Thomas Jefferson Page now assuming full command of the ship. Her Danish Captain and crew were left behind.

Soon, Stonewall appeared to be a bad seabot in heavy weather, rolling heavily and notoriously unstable. Encountering foul weather in the Bay of Biscay, she had her rudders damaged. Sje was heading to the island of Madeira to gather coal for the final crossing, in Portugal, but instead she headed for Ferrol in Spain. This unfortunate accident had her stuck in drydock for months long repairs. This provided time for the Union to be notified of her clocation and prepare a small squadron to intercept her.

In February-March 1965 the Union Navy sent indeed the Frigate USS Niagara and the steam sloop USS Sacramento. They stayed at sea, keeping a look on Stonewall, now anchored off Coruña, with still repairs left. At last on 24 March, Captain Page decided to put to sea and prepared to engage the Union vessels. The latter, unarmored, declined to fight, allowing Stonewall to steamed for Lisbon and take coal for her crossing. CSS Stonewall eventually reached Nassau in the Bahamas on 6 May, the re-coal and sailed to Havana in Cuba. There, she received a courier announcing the war had ended on the 11th.

USoon afterwards, union ships arrived at Havana (15 May). They created a “security curtain” this month, constantly reinforced notably by the monitors USS Monadnock and Canonicus, largely up to the task of dealing with her. Captain Page decided that honour commanded instead of the Union, to turn his ship over to the Spanish Captain General of Cuba. The latter, on behalf of the Spanish government managed acquisition negociations, and accepted to pay $16,000 to pay for the crew’s wages, the ship being “leased” to the Armada in Cuba.

Eventually, the US Government negociated with the Spanish Governor, in order to have the ship turned over to their representatives, in return for a reimbursement of the same amount. The sum was delivered on 2 November, thus CSS Stonewall was examined while the crew was take into custody or proposed to stay aboard and man their vessel. Captain Page was discharged. The commission soon saw she needed some repairs before leaving Cuba. When done, she was escorted by USS Rhode Island and Hornet and departed Havana on 15 November for the Washington Navy Yard (24 November).

However as she proceed during the night of the 22-23 in the Chesapeake Bay she failed to spot and coal schooner off Smith Island, which was rammed and sank by accident. Fortunately no lives were lost, but this was her only “kill”, albeit in peacetime and accidental. Since the USN had no immediate projects to press her into service, she was paid off and laid up at the Washington Navy Yard.

Kōtetsu With the Shogunate (1868)

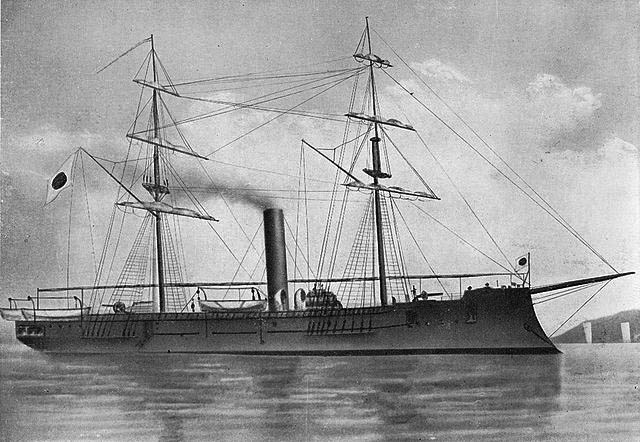

kotetsu flying Japanese colors

USS Stonewall (presumably holding her name) was still in suplus storage, decommissioned, when Japanese delegates arrived in the USA for a purchase commission. They seeked to acquire surplus vessels of the Union and captured confederate vessels, on behalf of the Shogun, Tokugawa Yoshinobu, which direct ancestor was no other than Tokugawa Ieyasu, the “Japanese Napoleon”, and unifier of the country in the Sengoku Jidai period (1600).

At the time, tensions between the Emperor Meiji, which councellors were favourable to the rapod modernization of the country, and the Shogunate factions, to restore traditional value and resist change. They were in power since the 1840s.

The Tokugawa shogunate however declined during the Bakumatsu era, from 1853, until overthrown by supporters of the Imperial Court (Meiji Restoration, which started in 1868) and the Empire of Japan established while Tokugawa loyalists continued to fight in what became the Boshin War, and “Republic of Ezo”. But in 1867, the Tokugawa shogunate was till ruling the country and seeked to acquire modern ships fro the West. After examining several surplus vessels, Ono Tomogoro while in the Washington Navy Yard in May 1867 was advised by the US delegate there to choose the former Stonewall, expecting to return the recent taspayer’s expense for this ship to Spain. Ono made a formal offer to the government for the purchase, which was concluded to $400,000.

Kotetsu (甲鉄艦 ‘kōtetsukan’) in the Shogun TW fall of the samurai expansion.

On 5 August, she was officially handed over, with the personal Shogunate flag hoisted. She was simply renamed Kōtetsu, which meant “ironclad”, and she became the very first ship of the type ever commissioned by Japan. She was refitted and prepared for the long crossing (probably started in September or October) with a US captain and crew taking her for a delivery, making many stops in between during this winter’s months journey. When she arrived in Shinagawa harbor on 22 January 1868, the Boshin War between the shogunate and pro-Imperial forces just started.

It seems she was also rearmed while in the US: One of the two 70-pounder guns was removed, a pair of Armstrong 6-pounder guns was added as well as four 4-pounder field guns, and a Gatling gun.

Trouble started immediately: Since the while house took a neutral stance in this war, they considered all weapons deliveries should be stopped, which included the Kōtetsu to the Shogunate. Indeed, she carried a Japanese flag but an American crew, making if for a very uneasy situation. US Resident-Minister Robert B. Van Valkenburg decided that she needed to be returned to the American flag and sail back to the US. Negociations were harsh, but eventually Kōtetsu took part into the war, hoisting a new flag for a new owner, being delivered to the new Meiji government in early March 1869.

Kōtetsu in the Boshin war (1869)

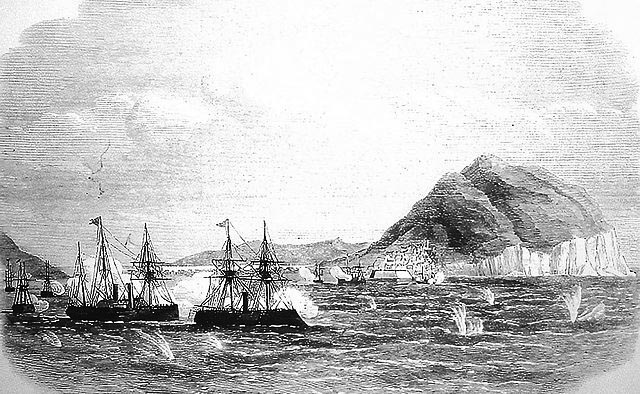

Naval Battle of Hakodate, 1869.

Tokugawa admiral Enomoto Takeaki at the head of what left of the Shogunate Navy refused to surrender after the fall of Edo Castle. He escaped to Hakodate (Hokkaido) in the north with which the few ships remaining, and a few French military advisers led by Jules Brunet (which inspired the figure in the movie “the last samurai”).

The Tokugawa fleet comprised eight unarmoured steam warships, and still this made the strongest naval force in Japan. On 27 January 1869, the foundation of the Republic of Ezo, with Enomoto as president angered the Meiji government which dispatched its own, newly formed Imperial Japanese Navy headed by the flagship IJN Kōtetsu and a bunch of unarmoured steamers seized in various feudal domains, loyal to the Emperor. On 25 March 1869, Kōtetsu distinguished herself at the Battle of Miyako Bay, repulsing a surprise night boarding by the Kaiten’s crew (Ezo flagship). Acquired the past yeat to the US, she had a Gatling gun, whih decidely showed its worth in this event.

Kōtetsu later supported with her guns the invasion of Hokkaidō and took part in many naval engagements, culminating in the Naval Battle of Hakodate Bay. There, she led a battle line comprising the IJN Kasuga, Hiryū, Teibō No.1, Yōshun, Mōshun (and three more steamers), under command of admiral Masuda Toranosuke (flagship Kōtetsu), decisively defeating the Shogunate’s fleet, 5 steamers strong (Kaiten, Banryū, Chiyoda, Chōgei, Kanrin Maru, Mikaho) under command of admiral Arai Ikunosuke. The Imperial ironclad proved imperveous to their fire and decisively crippled the Kaiyō Maru and Kanrin Maru, turning the tables.

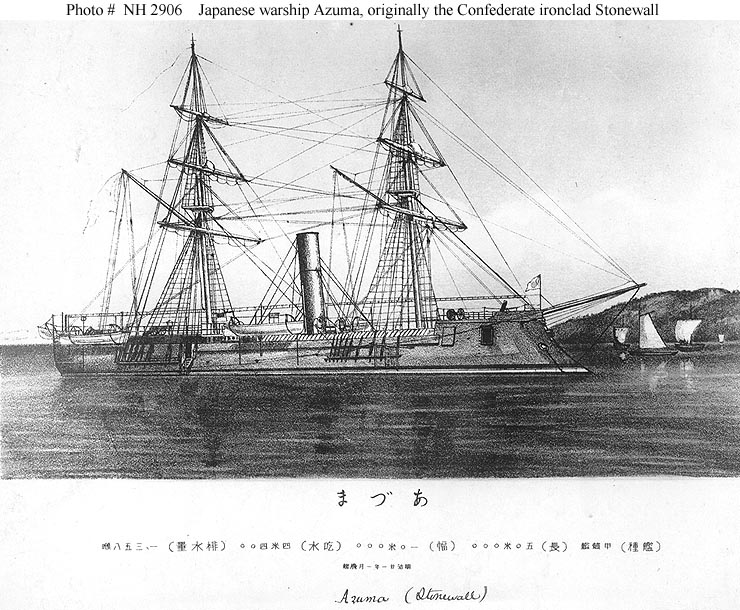

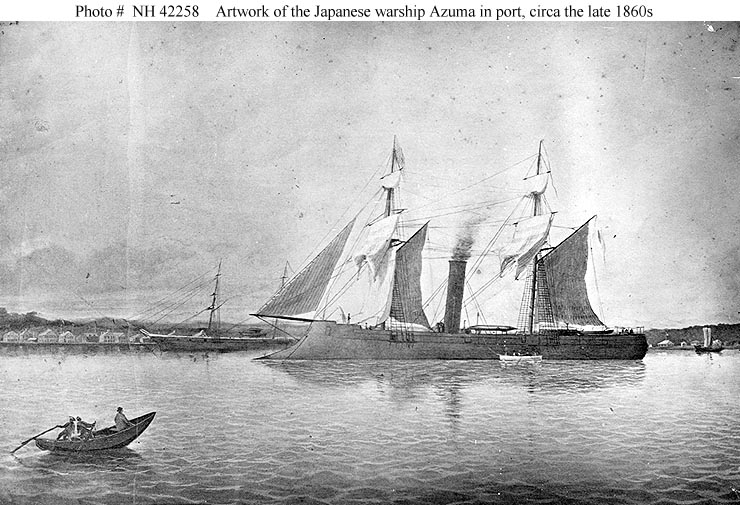

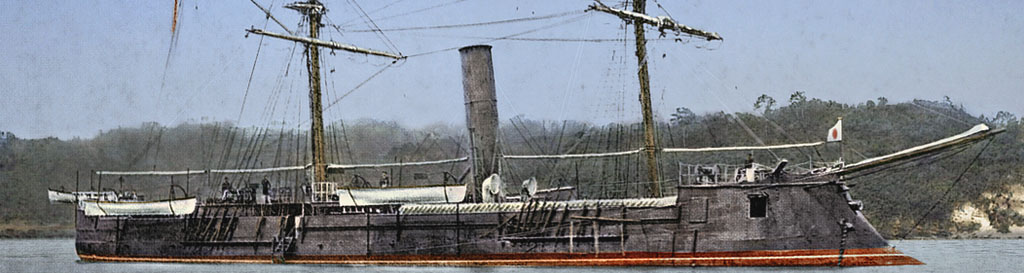

Fourth and last career as the IJN Azuma (1871-1888)

Engraving of the Azuma

Following the war in August 1870, IJN Kōtetsu was gradually side-lined. It appeared her timber rotted quickly and she presented many structural problems. She became a third-class warship from 15 November 1871, renamed for the last time, now IJN Azuma from 7 December. In January 1873 an inspection reported her general poor state, and a small refit tried to remedy her problems. IJN Azuma was assigned as a moored guardship in Nagasaki, protecting the port during the Saga rebellion in February 1874. She was refitted enough to be part of the Taiwan Expedition in May 1874.

On 19 August 1877, she was caught in a typhoon, and ran aground at Kagoshima. Later refloated she was repaired at the Yokosuka Naval Arsenal and was ready to take part in the Satsuma Rebellion later, as guardship in the Seto Inland Sea. Her fate after this is not known, apparently she became a TS and depot vessel. Eventually she was stricken on 28 January 1888, sold for scrap on 12 December 1889, with her armor plating recycled into electric generators in the Asakusa Thermal Power Station of Tokyo in 1895, still in existence.

Read More/Src

Books

Ballard C. B., Vice-Admiral G. A. The Influence of the Sea on the Political History of Japan.

Jentschura, Hansgeorg; Dieter Jung, Peter Mickel. Warships of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1869–1945.

Onodera Eikō, Boshin Nanboku Senso to Tohoku Seiken. Sendai: Kita no Sha, 2004.

Canney, Donald L. (2015). The Confederate Steam Navy 1861–1865. Atglen, Schiffer Publishing

Case, Lynn M. & Spencer, Warren F. (1970). The United States and France: Civil War Diplomacy.

Greene, Jack & Massignani, Alessandro (1998). Ironclads at War: The Origin and Development of the Armored Warship, 1854–1891.

Lengerer, Hans (2020). “The Kanghwa Affair and Treaty: A Contribution to the Pre-History of the Chinese–Japanese War of 1894–1895”.

Scharf, J. Thomas (1977). History of the Confederate States Navy From its Organization to the Surrender of its Last Vessel

Silverstone, Paul H. (2006). Civil War Navies 1855–1883. The U.S. Navy Warship Series

Stepesen, Robert Steen (1968). Vore Panserskibe [Our Armoured Vessels]. Marinehistorisk Selskabs skrift

Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships 1860–1905. Conway Maritime Press.

Links

The Armoured Ram Stærkodder

NavSource Online: “Old Navy” Archive – CSS Stonewall

Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion.

“Stonewall”. Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Naval History and Heritage Command.

Sphinx-Staerkodder-Stonewall-Kotetsu – militaryfactory.com

Drachinfels video about Kotetsu

wiki EN

warshipsresearch.blogspot.com

thelateunpleasantness

On laststandonzombieisland.com

Model kits

Not a lot of choice here. Scratchbuilt seems to be a viable option.

kotetsu cardboard model 1:200

1/1250 kit

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign