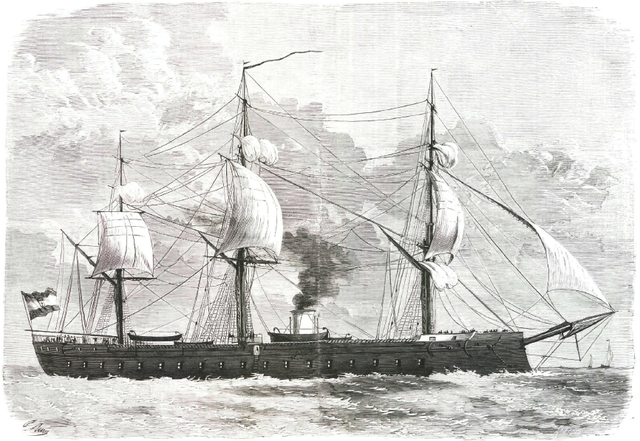

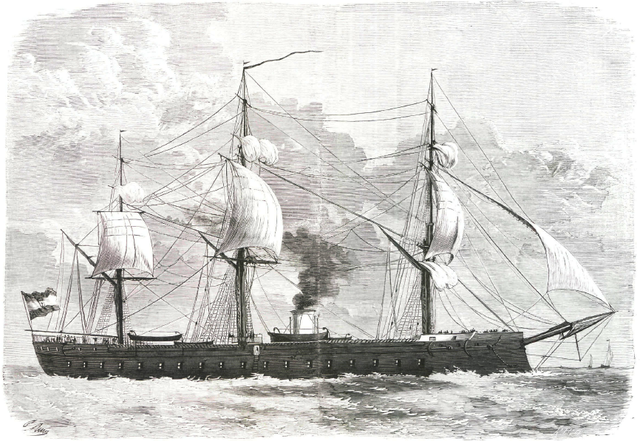

Numancia was a French-built Ironclad, the first “battleship” ever in service with the Armada. She had a fairly long career, and was rebuilt and rearmed four times. On 19 October 1873 she sank by accident the gunboat Fernando el Católico, in November 1902 protect Spanish citizens in Morocco, had a mutiny off Algiers in 1911 a mutiny, became a guardship after he reconstruction in France in 1897 during the Spanish American war, and sunk while being towed to be scrapped in Bilbao, running aground off Sesimbra, Portugal, in December 1916.

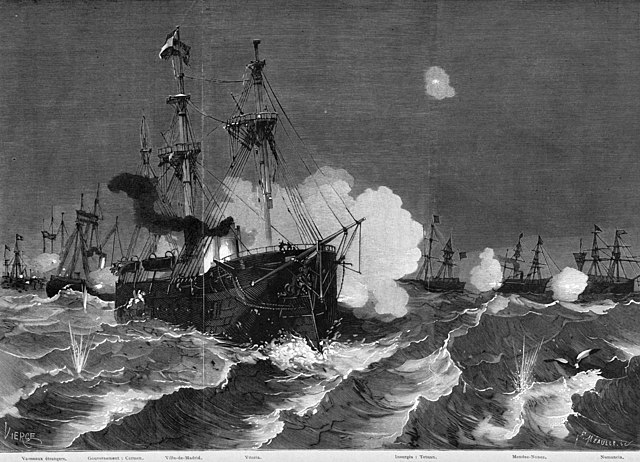

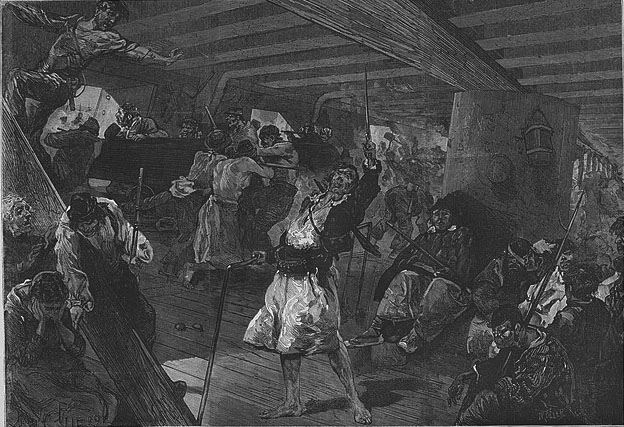

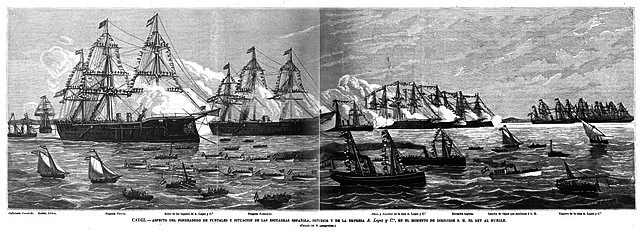

Numancia’s battle off Cartagena against Madrid insurgent’s Frigates.

Development & Context

Spain in 1859, when the French launched the armored frigate Gloire, followed soon after by Britain with its iron-hulled Warrior class, was found, like all the other navies, traditional or on the rise, caught off-guard. At the time, the Armada had valuable frigates (see the Spanish Armada 1860-70), two 85-guns ships of the line (Reina Doña Isabel II, Rey Don Francisco de Asís), four more (ex-Russian 74-guns in poor state, never really in service) three large screw frigates (Asturias, Berenguela, Blanca), and four sailing frigates plus many more sloops, corvettes, gunboats and smaller bricks and service vessels.

Under Queen Isabel II, her navy advisor urged the obtention of a 1861 naval program to give the Armada at least four broadside ironclads. The first two were ordered in 1861, and both in France but in different yards: Numancia at La Seyne (Toulon, Southern France, Med coast) and the second in a local yard prepared for this, at Ferrol (Royal Dockyard), Galicia, Atlantic coast, but with French plans and guidance.

She was the first attempt to return Spain into the circle of the world’s main naval powers after the Trafalgar debacle and a very long eclipse. Her name honored the old Celtiberian inhabitants of Numancia, slained by the Roman invaders and became the second of the three ships bearing that name.

The idea of having a fleet of protected warships was born in 1782 when Spain besieged the British-held Gibraltar. Since La Gloire opened the way to a new arms race, naval renovation for Spain became a golden opportunity to recover its lost prestige and place ater the debacle of Trafalgar in 1805. The Queen was seduced by his advisors of the sight of an imposing fleet of armoured frigates, enough to make the Armada the world’s fourth largest naval power again. However, the government’s need was soon rebuffed by the Spanish shipyards, still setup for traditional shipbuilding, and lack of industrial basis for the hull’s iron construction, let alone wrough iron for the armour plating, and modern artillery. Therefore, foreign shipyards were immdiately thought for.

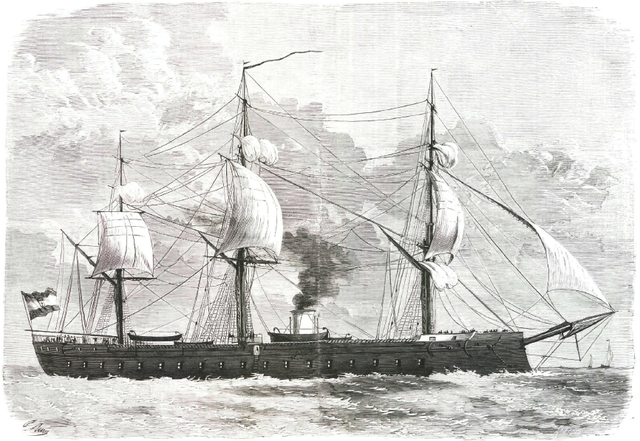

Numancia had her origin in April 1862, after signing in Madrid a contract with Forges et Chantiers de la Mediterranée (La Seyne shipyard), for the construction in its 2nd basin of a vessel, more or less inspired by the contemporary Couronne class. Work started in September 1862, and she was launched on November 19, 1863, blessed by the local bishop and assisted by members of the Royal Family as well as the ambassador. First sea trials and armaments testing were carried out during her trip, after completion in December 1864, from the French shipyard to Cartagena. On December 20, she arrived, after crossing 472 nautical miles in 43 hours, which was considered excellent at the time. Cost amounted to 8,322,252 pesetas, making her the costiest Spanish ever to be commissioned at the time.

Design

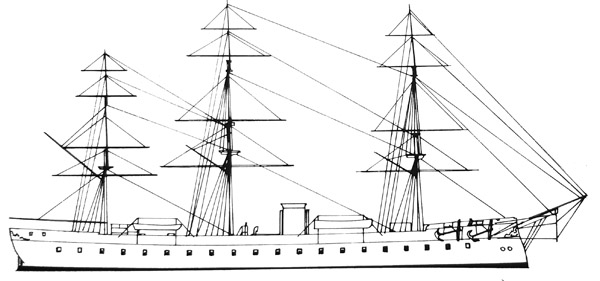

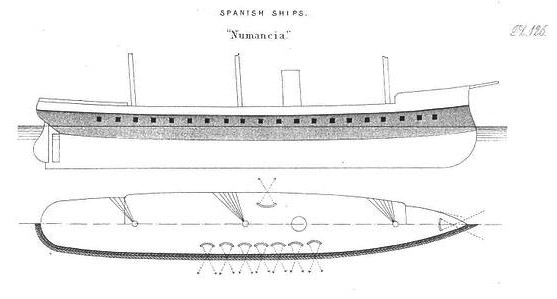

Conway’s profile

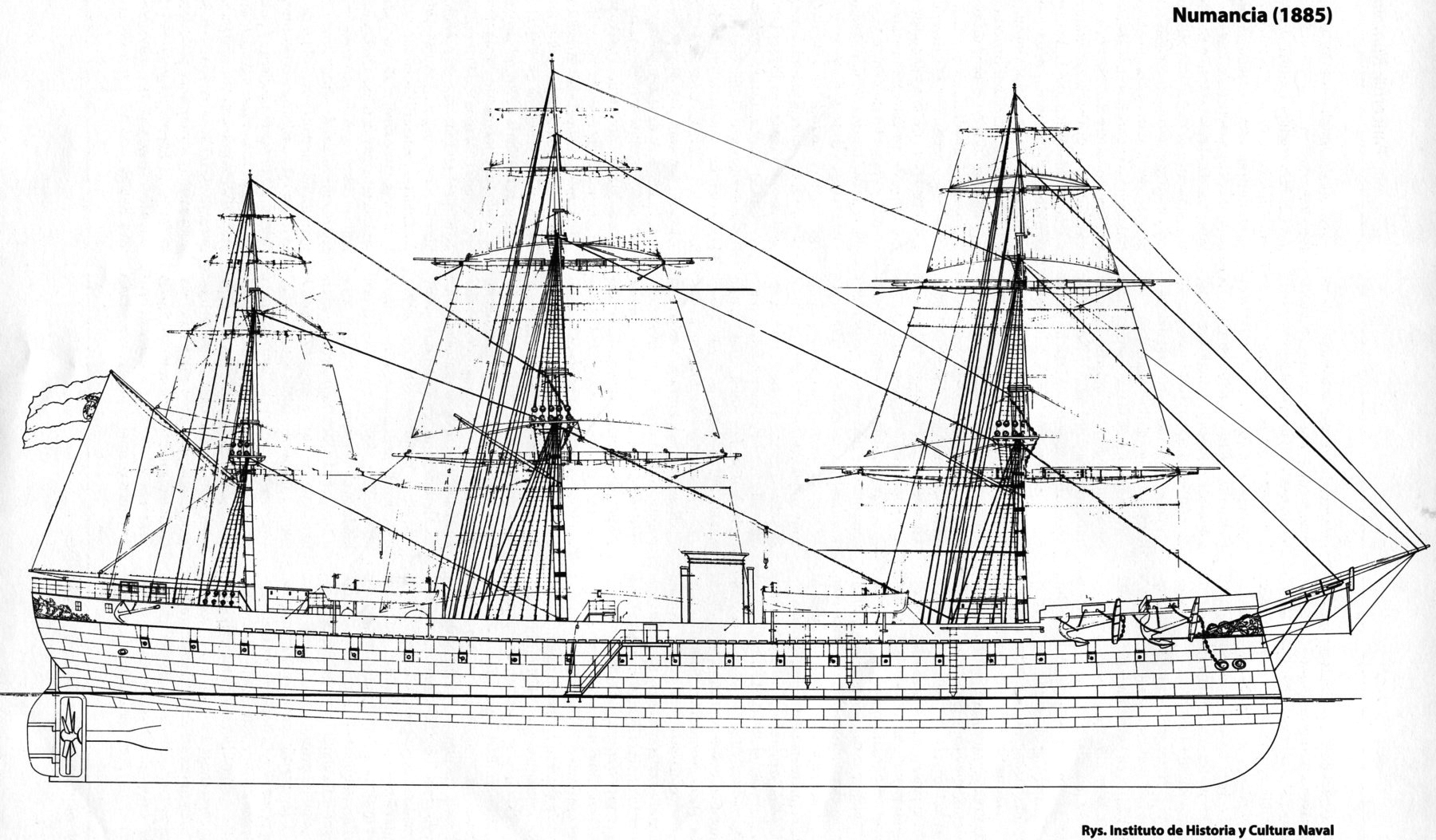

Her hull, unline Gloire and other French ironclads, called less for wood and more iron plating, held together by two million rivets. Her average draft of 7.90 m. The armour shell weighted 1,355 t, but based on teak wood padding with iron plates covered from 2.3 m below the waterline up to the upper deck. Both the upper and lower decks were 10 mm less at the stern and bow ends. Two elliptical wooden towers were used as conning towers, one at the bow and the other at the stern, reinforced with 120 mm iron plating for the helmsman and commander.

Hull and general arrangements

More detailed profile, as of 1885 – Instituto de Historia y cultura naval

Numancia’s hull measured 95.6 meters (313 ft 8 in) on the waterline, for 17.3 meters (56 ft 9 in) in beam, 7.7 meters (25 ft 3 in) draft and an overall displacement of 7,305 metric tons (7,190 long tons). She was fitted with a reinforced ram bow as customary for the time. Her crew comprised 561 officers and ratings.

Rigging

Her rigging comprised four masts (including the bowsprit with three jibs), three simple squared masts (four sails levels for the main and foremasts -course, upper, top, etc but also spanker and mizen couse, topgallant for the mizenmast). In all, this sail area represented with the extra studdingsails a total of 1,800–1,900 (1,846 m² for a Spanish source) square meters (19,000–20,000 sq ft). It was a far cry to the 4,497 m² of the HMS Warrior though. Her top speed under sail is unknown. About 150 me were dedicated to it, knowing that most demanding rigging manoeuvers were all done using steam-driven casptans.

Steam power

A shipyard model in the Madrid’s Maritime Musem

Numancia received a pair of horizontal return connecting rod (RCR) steam engines at La Seyne shipyard, home built. They were a Dupuy de Lôme design, and the cylinders made ø2.14 m and a stroke of 1.5 m, fed by 8 boilers. With a power of 1,000 horsepower, this machine drove a four-blade bronze propeller of ø6.35 m, with a pitch of 8.5 m, after interconnection via gears on a single shaft. Steam was provided by eight cylindrical boilers, truncated into a single round funnel amidship and centerline.

Rated output, total, was 1,000 nominal horsepower, 3,700 indicated horsepower (2,800 kW). Numancia reached 12.7 knots (23.5 km/h; 14.6 mph) as designed, and verified later on trials. She also carried 1,100 metric tons (1,083 long tons) of coal in her hull, for a range of 3,000 nautical miles (5,600 km; 3,500 mi), at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph). Coal could be spared when rigging, adding to her overall range.

Armament

French Engraving, “L’illustration” Newsreel, Inside the Battery Deck during the 1877 Battle.

Due to her armament, and despite her tonnage, Numancian was armed and classed as a frigate. It was changed a lot, four times, during her long career:

Her main battery comprised forty 200-millimeter (7.9 in) -Presumably British*- smoothbore guns, all under portholes along the broadside. These pieces could elevate to 15°, but had no or little traverse, being stuck with a rather heavy wheeled carriage. A pulley system ws used to have back in place after recoil. They had a Muzzle velocity of 1,579 feet per second (481 m/s), and effective range of circa 3,000 yards (2,700 m), max range at 15° of 3,620 yards (3,310 m).

In 1867 her broadside was gutted and she was rearmed with just six 229-millimeter, three 200 mm Armstrong-Whitworth guns on the gun deck. For the secondary artillery on the main deck, eight locally built Trubia 160-millimeter (6.3 in) guns. They were all rifled muzzle-loading (RML).

In 1883 Numancia was this was simplified to eight Armstrong-Whitworth 254-millimeter (10 in) RML guns and seven 200 mm RMLs.

In 1896–1898, her armament was changed to six Hontoria* 160 mm and eight Canet 140-millimeter (5.5 in) rifled breech-loading guns and a pair of 354-millimeter (14 in) torpedo tubes.

*Spain licenced built Vickers guns hrough the firm Hontoria from 1879 onwards.

Armour Scheme

Scheme of the vessel in Brassey’s Naval Annual 1888

Numancia’s flanks were protected by a complete wrought iron waterline belt, 130-millimeter (5.1 in) thick. Presumably the armor plates came from Schneider & Cie, Le Creusot, only specialist in France at that tome. Above the belt, the gun battery was protected by another plating belt 120-millimeter (4.7 in) thick, a strake of armor extending all along unlike the main waterline belt. The deck was unarmored, as customary at the time. Artillery range was not great enough for parabolic enegagements.

Major 1896-98 Reconstruction

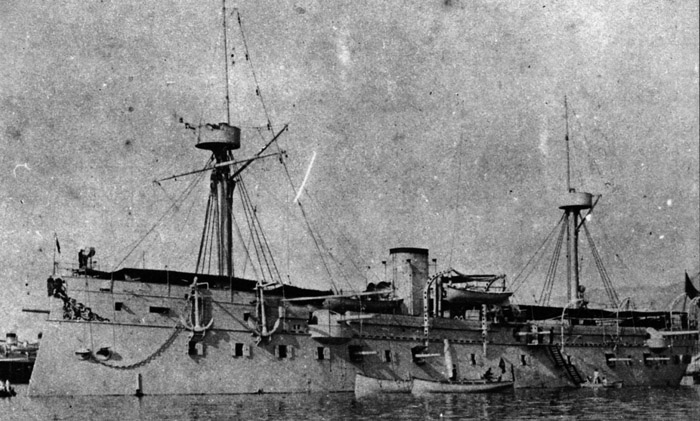

Numancia after refit in 1898, warships international

For the last leg of her career, spanning almost nineteen years, she was transformed into a modern guardship, taking advantage to her armour. This was done at La Seyne, where she was built many years prior. This was a two-years long process, pretty radical, as she was gutted down to the machinery compartment floor. There, she receiving brand new boilers, a new VTE engine (for 12 knots), and a brand new artillery:

- 6x Hontoria RBL 160 mm guns ( in) placed

- 8x Canet 140-millimeter (5.5 in) RBL placed

- 2x 354 mm (14 in) torpedo tubes, underwater on the broadsides.

Her rigging was cut and she had instead new steel masts, with fighting tops (later to receive extra light guns to deal with torpedo boats). According to navypedia.org indeed, she received in 1900 twelve 47mm/40 Skoda QF guns.

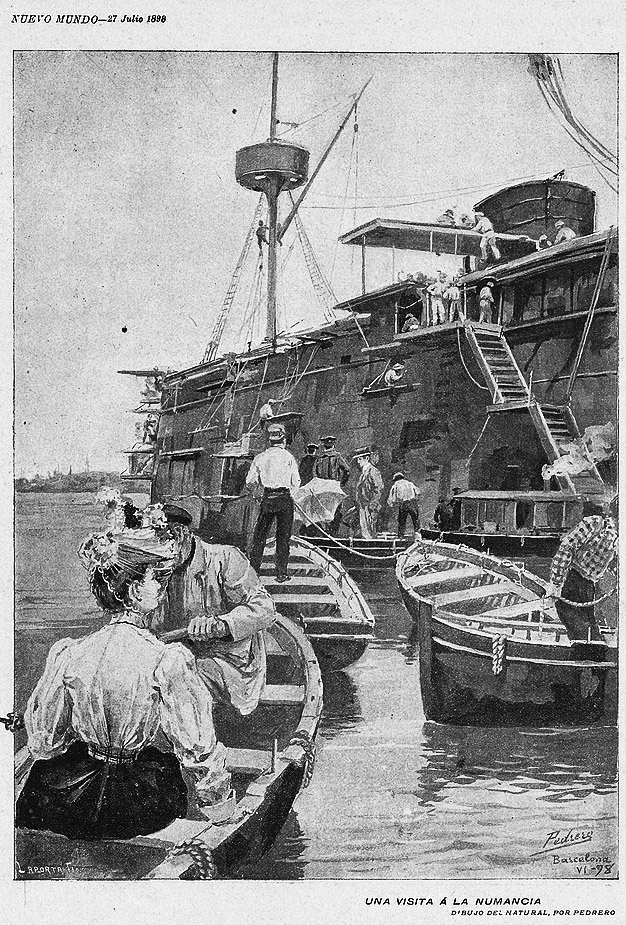

Drawing by Pedrero, a visit onboard Numancia in Barcelona, 1898.

Read More/Src

The Armada in Cadiz, 1877 – engraving (HD)

Adamson, Robert E. & de St. Hubert, Christian (1991). “Question 12/89”. Warship International.

Brassey, Thomas (1888). The Naval Annual 1887. Portsmouth, England: J. Griffin.

de Saint Hubert, Christian (1984). “Early Spanish Steam Warships, Part II”. Warship International.

Chesneau, Roger & Kolesnik, Eugene M. (eds.). Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships 1860–1905.

Pastor y Fernandez de Checa, M. (1976). “The Spanish Ironclads Numancia, Vitoria and Pelayo, Pt. II

Silverstone, Paul H. (1984). Directory of the World’s Capital Ships. New York: Hippocrene Books.

“Spanish Ironclads Numancia and Vitoria”. Warship International. VIII (3)

hemerotecadigital.bne.es

Historia General de España y América : Revolución y Restauración: (1868-1931), José Andrés-Gallego

Navies in Modern World History – Lawrence Sondhaus

Battleships: An Illustrated History of Their Impact – Stanley Sandler

El cantón murciano Escrito por Antonio Puig Campillo

La vuelta al mundo en la Numancia de Benito Pérez Galdós

Antionio Perez Crespo – El Canton Murciano

Impresiones del viaje de circunnavegación en la fragata blindada Numancia Escrito por Eduardo Iriondo

Crónica de la provincia de Pontevedra

Escrito por Fernando Fulgosio

Viajes regios por mar en el transcurso de quinientos años: narración

cc commons photos

wiki

On weapons & warfare

Numancia in service

Numancia had a very long active life, and participated in practically all notable geopolitical naval events in the history of Spain in the XIXth Century, up to WWI.

On January 8, 1865, after months of training, she set sail from Cartagena to Cádiz, her main homeport, arriving the 11th. Captain Casto Méndez Núñez (future celebrity of the Armada) took command. Assigned to the Pacific squadron she started a long trip, with worries about how ironclads faired in such experiences looking at the French and English and their latest ironclads on long voyages. Departing on February 4, 1865, from Cádiz, she coaled in San Vicente on February 13, and after corssing the south Atlantic, arrived in Montevideo on March 13. She departed on April 2 for the Cape Horn accompanied by the Marqués de la Victoria, her coaler for the trip. She rounded the cape and found in Valparaíso on April 28, the corvette Vencedora. The Captain was informed that the Spanish squadron had moved to Callao, where she arrived in May 5, 1865.

Spanish–South American War

On February 17, 1866, with the vessel La Blanca, she departed Valparaíso for the Chiloé Islands, aiming at San Carlos in Particular, where she dropped anchor on the 27th, in the low port and on March, 1 dark port, on the 9th moving in the bay of Arauco where La Blanca seized a paddlewheel steamer. Two other coal barges were also captured a day later, allowing both ships to resupply. On March 12, the Spanish squadron comprised five ships and departed for Valparaíso, arriving on March 14-16.

Numancia took part in the bombardment of Valparaíso on March 31, 1866. Her captain, de facto now squadron commander, gave the signal to start the cannonade, firing eight blanks. The Frigate Villa de Madrid and Blanco went against the fiscal warehouses, and the Frigate Resolucion against the Railway, Numancia shelling the administration building and stock market. After an hour and fifty minutes, all was turned to rubble.

Painting by Rafael Monleón depicting the bombing of El Callao. In the center, the Numancia.

On March 14, she sailed northwards with the rest of the squadron in the Pacific, to El Callao, arriving on April 25, stopping at the Island of San Lorenzo. She took part in the battle of El Callao, at the head of the Pacific squadron, dealing with fortifications but receiving 52 hits. The first time she was seriously tested. Her armour proved its worth. When approaching the coast to carry out the initial shelling her bottom unknowingly cut electrical cables activating sea mines arranged in Callao, so she spare the squadron significant destruction.

Battle of Callao: Casto Mendez Nunez lay wounded on the bridge of Numancia.

After a victory on Callao, the fleet sailed to San Lorenzo Island, to be repaired. In all, for the squadron, 43 killed sailors were buried and captured ships were burned. On May, 10, the squadron departed, the frigates Villa de Madrid, Blanca, Resolucion and Almansa returning to Rio de Janeiro by rounding Cape Horn, with Captain (de facto admiral) Casto Méndez Núñez aboard Villa de Madrid.

Berenguela ws not fit for such crossing at that time of year, and was still repaired after having the most serious damage from this fight. Numancia was spared the same, in addition to having exhausted her coal. The second group was commanded by Manuel de la Pezuela y Lobo-Cabrilla, her new captain. Instead, she was to go through the Pacific. Thus, Numancia became the first Spanish armored ship to make a world’s tour: From Cadiz, she had stopped in Montevideo and Buenos Aires, rounded Cape Horn, stopped off Chile in San Carlos de Chiloe Island, attacked Concepcion, bombarded Valparaiso, shelled Coquimbo, Caldera, and stopping in Chincha Island before the battle of Callao, and from there, crossed the Pacific westwards to the Philippines.

She had the Pacific breeze at her stern, and with all her rigging up, both vessels, Numancia and Berenguela were able to sail to the Philippines together with the schooner Vencedora, and the steamships Marqués de la Victoria, Uncle Sam and the sailing transport Matauara. Numancia, however was slower than the rest due to her displacement and comparatively low sail surface, and delayed the rest of the squadron to such an extent that Berenguela used only her topsail to stay in.

Finally, Berenguela went ahead, and on May 15 when several cases of scurvy appeared in her crew, she took the steamer Uncle Sam with her. Numancia also separated on May 19 and arrived on Otaiti Island, on May 22, 1866 with 110 affected by scurvy on board. When her hull was studied, Mines cables caught underwater in Callao were found twisted around her propeller. Numancia departed and eventually arrived in Spanish-held Manila on September 8, 1866, after having overtaken Berenguela on August 29. Then she proceeded to her trip back to Europe, stopping in Indonesia, crossing the southern Indian Ocean, passed south of Madagascar and then rounded the Cape, crossing the South Atlantic to Rio de Janeiro before making her last leg back to Cadiz.

Cantonal Rebellion

Naval combat of Portmán, Cartagena, October 11, 1873

Nothing much happened in the next years, in 1867 she had a major overhaul in drydock, and in the 1870s, trained with the rest of the fleet. On July 13, 1873, the day after the revolutionary junta was constituted in Cartagena, Captain Antonio Gálvez Arce onboard the frigate Almansa convinced the crew members to join the uprising, despite the officer’s advice and the the Spanish flag was lowered. Soon, Numancia, Tetuán, Vitoria and Méndez Núñez, four of the seven Spanish ironclads, plus the steamship Fernando el Católico, joined the “Canton rebellion”. All those who join the loyalist cantonal squadron were declared pirates on July 20 by decree of the Nicolás Salmerón’s government.

On September 15, the fleet set sail from Cartagena with the Méndez Núñez and Fernando el Católico, under orders of General Carreras. They were shadowed by HMS Swiftsure, HMS Invincible, HMS Torch and the Italian corvette Venezia as observers, with troopships. They stopped in Águilas to collect funds and supplies, dropped anchor on the 16th and went back to Cartagena on September 17.

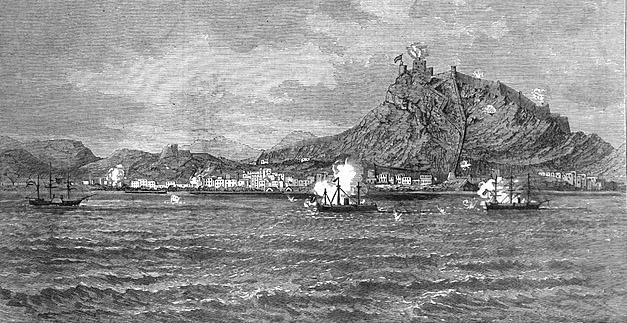

The bombardment of Alicante, 27 Sept. 1873

On September 21, Numancia raided Alicante, try to add the city to the cantonal rebellion, under threat of her battery. This failed and she retired on the 22nd to Cartagena after after inspicting the preparations for the defense of the plaza. on the 24th, she was back to Alicante with Méndez Núñez and Fernando el Católico. Together, they shelled the city to submission on the 27th, expending all their shells after a rain of steel for 5-7 hours.

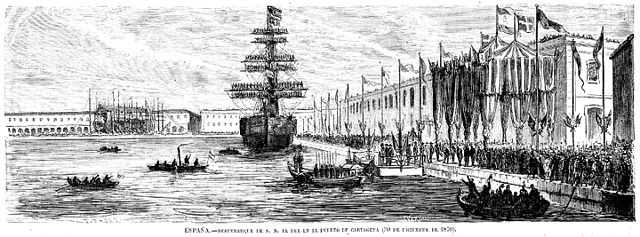

The King disembarking at Cartagena

Numancia became flagship of the cantonal squadron based in Cartagena. There, she led the fleet into the Battle of Portmán, on October 11, 1873, against the government’s squadron. Numancia led the squadron but too such advance that she disrupted the Squadron order, which withdrawn.

She made another sortie with the fleet two days later. This time, the squadron had a way better good combat disposition, Numancia maintaining her speed and place in line for the other two slower ironclads, and the government’s fleet withdrawn this time, and abandoning the blockade.

On October 17, 1873, Numancia sailed from Cartagena to Valencia and Barcelona in a show of force with Tetuán, Méndez Núñez and Fernando el Católico, carrying Generals Juan Contreras, Roque Barcia, Tomaset, and several Valencian and Catalan federal leaders plus troops. They were shadowed all the way by three British frigates. Their main mission was to add land troops in these cities, and force them to join the Cantonal uprising.

At 04:00h AM, October 20, Numancia accidentally rammed Fernando el Católico. The ram pierced her hull and she sank in a few minutes with almost all her crew. The steamers Darro, Victoria, Bilbao, Extremadura were captured along the way, reinforcing the fleet.

After the capitulation of Cartagena, on January 12, 1874, she sailed for Mazalquivir, taking onboard 500 personalities into exile from Oran, including the cantonalist leaders Antonio Gálvez Arce and Juan Contreras y San Román. All the way, she was able to out-run the Madrid’s loyalts ironclad Vitoria and the frigate Carmen. Numancia later surrendered to Vitoria on 17 January.

Interwar Years

Nothing much happened in the following years 1874-1883. In 1877 with Vitoria, she was equipped with electrical lighting in Barcelona. The two became the first in the Spanish navy to be so equipped.

In 1883, Numancia took part in a naval parade in the port of Valencia to the future Frederick III of Germany, after Alfonso XII’s visit to Germany aboard the armored corvette SMS Prinz Adalbert, from Genoa. Soon after she was drydock for an important overhaul and rearmament.

With the Universal Exposition in Barcelona on May 20, 1888, the Spanish squadron was anchored in full regalia, including Numancia, the screw frigates Gerona and Blanca, and brand new cruisers Castilla and Navarra, Isla from Luzón and Isla de Cuba, as well as the “proto-destroyer” Destructor, and the gunboats Pilar, Cóndor among others. This was an impresive show of how the Armada manage to modernize itself. Shortly after, she started a tour of goodwill visits through the Mediterranean, stopping in Italian and French ports. In Toulon, she attended the delivery of the brand new battleship Pelayo, built in her own shipyard and showing the Armada’s renewal. The latter became the new flagship.

Conversion to Coast Guard battleship

Nothing much happened of note in 1888-96. In 1896 however, like Vitoria, she was chosen to Toulon to be completely transformed and modernized as a coastguard battleship due to her speed, improper for fleet operations. During the Hispano-American War, she was therefore unavailable. Spain, in case of a USN raid home, pressed all its remaining ironclads as guardships on her western coast.

Once the war was over, she formed an important part of the Instruction Squadron with Vitoria, Pelayo and the cruiser Carlos V. The fleet needed fresh blood and to rebuilt it’s shattered prestige. In December 1909, during the Melilla war, Carlos V was unavailable, under repairs. The Ministry of the Navy sent instead Numancia as admiral ship to lead the second division in Moroccan waters.

In 1909 she was considered non-sea going. A new inspection in 1910, revealed that Numancia was now hopelessely obsolete. She was partly stripped, with a skeleton crew, used as a floating barrack and then accomodation ship in Tangier until 1912. After the Tangier mutiny of 1911, she was used as an asylum for Navy orphans.

There was a popular movement to preserve her as a historical monument since she took part in so many decisive parts of the recent Spanish History. But it went to nil, and she was stricken and sold for scrap to a company in Bilbao. There were three attempts to have her moved from Cádiz to Bilbao but she ran aground during the third, off the coast of Sesimbra, Portugal. This was on December 17, 1916. There, she was partially broken up and her remains layed there for many years in shallow waters.

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign