c105 ships in WW2

c105 ships in WW2

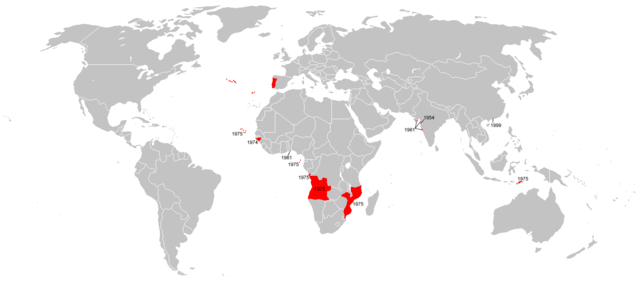

The subject of the Portuguese Navy in interesting, perhaps more than some Scandinavian neutral navies. Indeed, despite its neutrality, the Country that fathered Vasco Da Gama and so many legendary seamen and merchants, had once the largest colonial empire worlwide. And as the latter was a shadow of its former self in 1939, the Portuguese Navy still had potentially to defend it. Technically it was in the XXth century a “pluricontinental nation with overseas provinces”. These were Cape Verde, São Tomé and Príncipe, Guinea-Bissau, Angola, and Mozambique in Africa and in African seas, Macao and Goa in Indian waters. If the first were not really a concern, patrolled by rivering gunboats but too far away to constitute an interest for the axis, Macao and Goa interested Japan in 1942. While Goa was invaded, Macao became a de facto protectorate during the war. The island was attacked later by the USN.

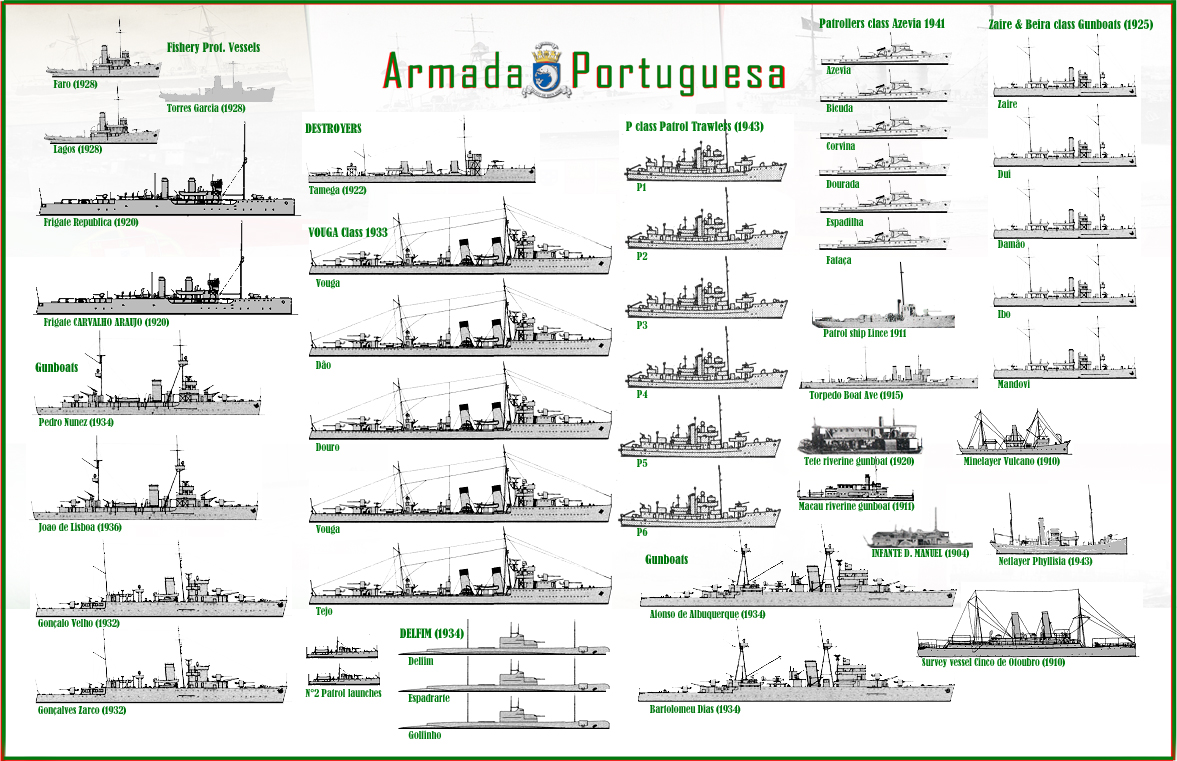

Author’s poster of the Portuguese Navy in WW2. It shows all significant vessels, listed, from 1939 to 1945. Basically the home waters could rely on five modern destroyers and three submarines. The rest was made of modern, powerful gunboats (The Albuquerque could engage destroyers), light gunboats and riverine gunboats. Mine warfare vessels were rare. Patrollers too, although modern ones (Azevia) were built in Lisbon during the war and in 1943-44 a few ships were acquired from the allies: Six patrol trawlers, and a netlayer. More acquisitions will follow after the war, mostly chap, surplus vessels of the Royal navy.

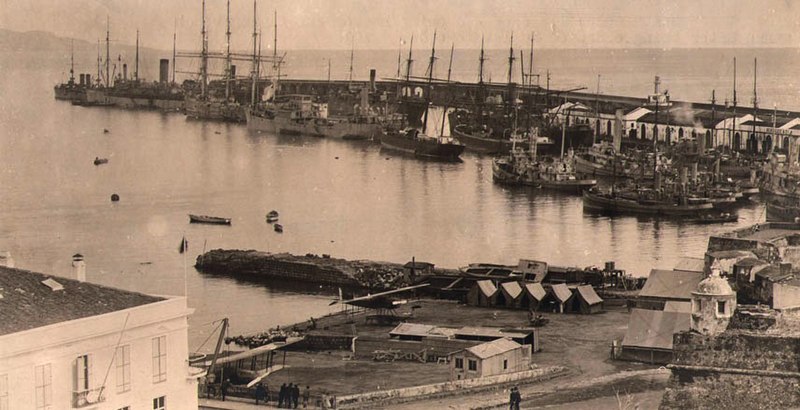

The Marina do Portugal during the great war

Vasco Da Gama. The venerable coastal battleship was scrapped in 1935 without any concerns for a modernization.

The interwar years

Although Portugal was hardly involved in the war, this small country had a prestigious past among all, and inherited a modest colonial empire in land extent but particularly large in the world. Portugal inherited African colonies, survivors of a coastal empire extending columns of Hercules to the Horn of Africa, and retaining Angola and vast territories in East Africa; but also islands in the Atlantic (Azores) with a strategic position, possessions and counters in the Indian Ocean (including Macao) and small islands in the Far East. The fleet was able to respond to riots and even a local revolutions, but absolutely not to a war against an enemy naval force. The distance and isolation of its possessions made them vulnerable in nature.

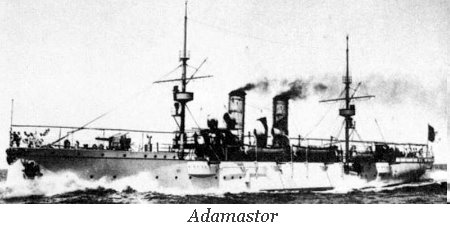

The venerable protected cruiser NRP Adamastor was discarded in 1933.

Portugal, however, practiced the “gunboat policy” and had a squadron in home waters (based in Lisbon) capable of dealing with such an aggression, but at the risk of losing the defense of the metropolis. Its modest manpower consisted mainly of destroyers, since the naval plan of 1930, spread over ten years, a handful of torpedo boats and submersibles, and especially colonial gunboats. Like many countries, it called for British construction for the majority of its ships, some built in Lisbon, but on British plans.

Portuguese naval aviation exploit

In 1922, naval officers Sacadura Cabral and Gago Coutinho made the first aerial crossing of the South Atlantic. This exploit was performed from the Lisbon Naval Air Station in Bom Sucesso, by 30 March. Their plane was a ww1 vintage Fairey III-D MkII seaplane, one of the many used by the Portuguese navy. It was outfitted for this perilous journey, notably with an artificial horizon, an invention of Gago Coutinho. They reached the Brazilian Saint Peter and Saint Paul Archipelago on 17 April 1920, progressing up to Rio de Janeiro by June.

New Infrastructures at Alfeite and Montijo

Construction started of a new naval base and arsenal at Alfeite, southern bank of the Tagus estuary. Facilities were intended to discharge the new overcrowded Lisbon Navy Arsenal, which already spread previously in several small stations between Lisbon and the Tagus estuary. This makes difficult to communicate and made urgent to concentrate the Lisbon Naval Base in a single place. Plans for the new facilities also concerned the Lisbon Naval Air Station. The Bom Sucesso docks were soon helped by the creation of a new base at Montijo. The Alfeite base was completed by 1924, housing the Naval School in 1936. Next year, the arsenal was completed as well. But since the place was extended, new facilities would be built along the years, into the cold war. In any case, the effort on land to bolster infrastructures helped the renewed Portuguese Navy in WW2.

Bolstering the Indian Ocean defences

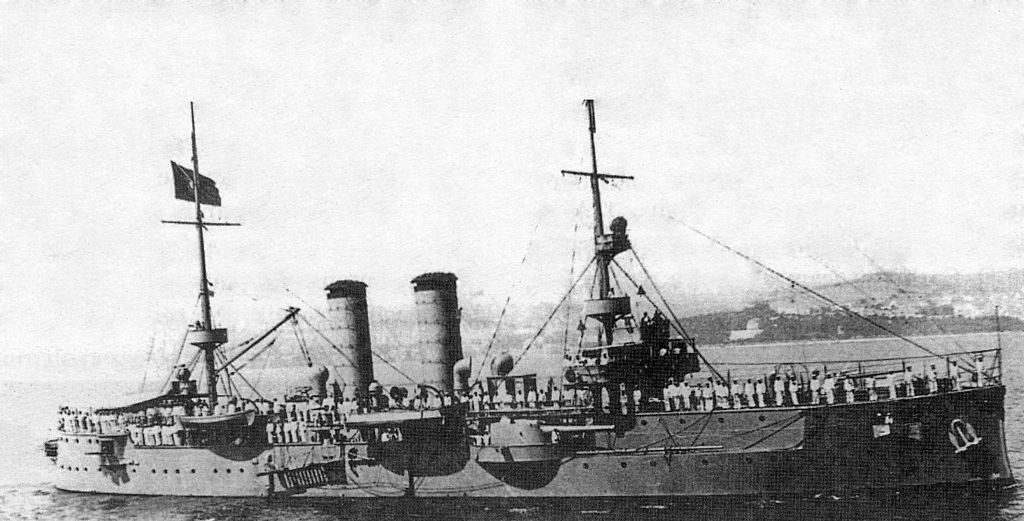

Piracy attacks, civilian conflicts in China triggered a response in 1927 from the Portuguese authorities, by sending to Macau the old cruisers República and Adamastor. They were reinforcing a squadron which comprised the much weaker gunboats Macau and Pátria. A naval air station was created at Taipa island, using Fairey III seaplanes. In 1937 with the Japanese invasion, the Navy sent in Macau sloops in rotation while the Macau Naval Air Station was later upgraded by receiving brand new and more modern Hawker Osprey seaplanes.

The Madeira Mutiny (1931)

On 4 April 1931, officers of the Madeira garrison in opposition to the Dictatorial regime of the time revolted whereas other military uprisings were planned on many other places on the territory. However they failed, often in face of a strong loyalist opposition. In Madeira however, rebels were supported by a part of the population and received help of exiled opposition politicians. Soon the island became a hotbed of political agitation and a rebel base. Considered as “pirates” and under threat of a possible foreign intervention or Loyalist fleet, some politicians tried to create a “Republic of the Atlantic”. This only increased defiance for Lisbon, urging a military intervention.

An amphibious operation to retake the island was setup, however with limited means as Navy has been neglected for years. Despite of this the new minister of the Navy Magalhães Correia, full mobilization of a flotilla with improvized merchant and fishing vessels was created for naval service. The flotilla included the improvized seaplane carrier Cubango with Four CAMS 37 flying boats, two auxiliary cruisers, two transport ships and four naval trawlers. The feet was commanded from the cruiser Vasco da Gama, escorted by a destroyer and three gunboats. This naval force soon was set in motion and sailed out to retake Madeira, leaving Lisbon on 24 April.

Landing operations started on 26 April 1931. Air support was crucial, for observation and artillery spotting, screening troops advance inside the island. After several days of bitter fighting on 2 May 1931, all resistance collapsed. The rebellion made it clear, both for the government and general public that a well equipped navy was a necessity to intervene in Portuguese territories along the map.

Rearmament of the Portuguese Navy.

Therefore from 1932, important investments were authorized by the Government, managed skilfully by the Minister headed by Magalhães Correia. He launched a new naval program based in earlier plans made up by Admiral Pereira da Silva. This naval program tried to setup a modern naval force for the Atlantic. Budget constraints meant only destroyers and submarines should be provided, but completed for overseas stations by powerful fleet gunboats and station gunboats for for colonial service. The larger ships were considered as avisos (sloops).

The ambitious plan also integrated a strike force comprising two cruisers, a seaplane carrier, naval aircraft squadrons as well as modern submarines and supporting vessels. However, budget constraints led to soon execute only part of the project from 1933 to 1939 (see later). The Portuguese Navy would acquire in total some 22 new warships like the Vouga-class destroyers and Delfim-class submarines and several fleet avisos. Neither the cruisers or seaplane carrier saw the light whereas cost cuts were obtained by discarding a lot of older vessels.

The Portuguese Navy in WW2: 1939 Order of battle

The Coastal Battleship Vasco da Gama (1876), after modernization and sixty years of good and loyal service, she was broken up in 1935.

Portugal hardly had any budget for a modern battleship. Dating from 1896-98, the last old Portuguese cruisers had been scrapped between 1923 and 1935. Budget limitations also prevented the adoption of a modern cruiser.

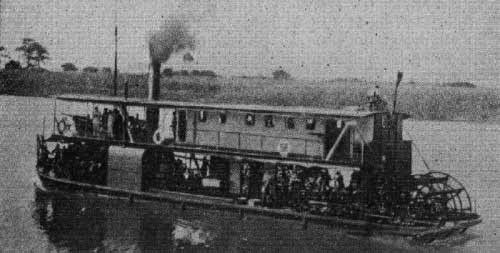

Riverine gunboat Flecha in 1910

Destroyers: The real spearhead of the Portuguese Navy was the Douro class, 7 ships of British origin, built mostly in Lisbon on plans from Yarrow, between 1932 and 1935. The old prewar River-class Tamega (1922) completed this strength. Of the four Tb 82F torpedo boats obtained in 1920, only one was active in 1939.

3 Delfim class Submersibles: Three oceanic submersibles ordered from Vickers in 1932. They were the Delfim, operational in 1935. They replaced the old Foca (1916).

2 Ave class Torpedo Boats: The Ave and Sado were former Austro-Hungarian torpedo boats from 1913, still in service in 1939 for coastal defense, athough only the Ave served until 1945.

24 Gunboats:

In order to maintain its presence in its Colonial Empire, Portugal spent a large part of the budget budget into the construction of large gunboats. There were the two old Republica (ex-British Flower class) the 5 old Beira (1910-18), the three Zaire (1925), completed by the more modern sloops of the Velho class (1932), the Albuquerque (1934), the Nunes (1934 ), adding to six light gunboats (Limpopo, Mineiro, Macau, Rio Minho, Vulvano, Tete) and some older patrol boats (see the nomenclature for details). They added to the WW1 Arabis-class sloops acquired in 1920 and still in service, Araujo and Republica.

Added to this strength was a coastguard, the Torres Garcia, and recent fishery protection vessels, the 2 Faro. The 6 Azevia would be built in 1941-42, the only wartime portuguese vessels completed.

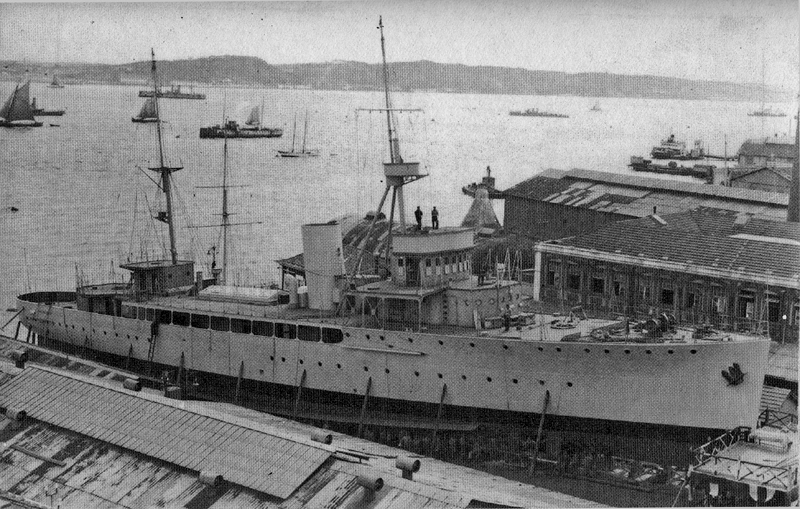

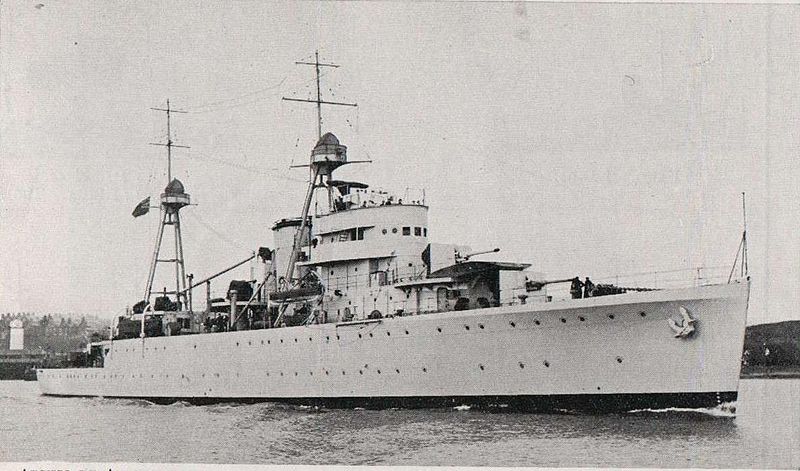

Joao de Lisboa in completion before launch at Lisbon DyD.

The Portuguese Navy during WW2

During wartime, the Portuguese navy’s main tasks were double: Enforce respect of the country’s neutrality from sea and air, home waters and on its colonies. Due to the sizeable Empire naval assets deployed were never enough to ensure this international respect. The Navy, 5 destroyers Class Douro and 3 submarines Class Dolphin were maintained in home waters, leaving the colonies to the vigilant guard of a handful of gunboats.

It was possible however to maintain the integrity of these territories of the Empire all along the war, perhaps not strategic enough to be seized by force by any belligerent, with the exception of East Timor, invaded and occupied by Japanese Imperial Army in 1942 and evacuated by 1945. There was nothing Portuguese authorities could do to avoid it at that time, no naval asset or alliance to play. In addition to the fleet there were only three Naval squadrons of about 40 aircraft, mainly seaplanes between Lisbon, Aveiro and Macau.

The threat of U-Boat warfare

Portugal found itself involved in the conflict, despite its policy of neutrality, in some occasions. To avoid being confused with ships from various belligerents, the Portuguese merchant fleet was ordered to display large flags of Portugal and their names painted on the hull sides. Neverthless, in the ruthless submarine warfare that followed, some incidents and attacks occured. The most severe happened in 1942, when the three-masted lugger sailing ship Maria da Glória en route to Greenland, was torpedoes and sunk without warning by U-94. 36 of her 44 crew sank with the ship.

Hitler latter could have made plans to acquire a very favorable position on this Atlantic coast for possible U-Bootes bases. However the risk of an invasion was too great to contemplate, especially going through Francoist Spain, not in the mood for such action on its own territory. There was certainly less chances Franco would have annexed portugal either, since despite Hitler’s pressure at the conference of Hendaye, on the French-Spanish border to obtain from Franco an attack or at least a blocus of Gibraltar, vital for the axis war effort in this theater.

German submarines operating in the South Atlantic, however, has been often been seen refueling in Portugal. Authorities closed their eyes as these supplies went through German ships displaying the civilian flag, even in Portuguese waters.

Situation in the Atlantic Islands

The Azores indeed soon became a prime target for all belligerents. Dispositions were made against a possible invasion. In 1941, ground and air forces arrived as a reinforcement, a 32,500 strong garrison and more than 60 aircraft. Patrol boats and destroyers were deployed there on rotation. Their air support was Fleet 10, comprising some Avro 626, Grumman G-21 and Grumman G-44 seaplanes. They patrolled the area from the old and refurbished Azores Naval Air Station, at Ponta Delgada. Madeira and Cape Verde islands also received reinforcements, also less important.

Localization of the Azores, surely a strategic asset for the allies and axis alike.

Both the Axis and Allied powers had plans to invade the islands to control the Atlantic. The British admiralty in this prospect prepared operations Alloy, Shrapnell, Brisk, Thruster, Springboard and Lifebelt. The US Nay prepared Operation Grey, while the Germans planned operations Felix, Ilona and Isabella. However these Portuguese military reinforcements successfully deterred any attempt invasion threat, added to skilfull diplomacy.

Nevertheless, the Portuguese also had a contingency plan for a strategic evacuation of the Azores in case of an enemy invasion. There were also plan for a possible invasion and occupation of Continental Portugal. In any case, this explained while the bulk of the Portuguese Navy stayed in home waters.

The risk was considered high enough as intelligence services were made aware of German preparations for Unternehmen Isabella and Felix in 1942. Eventually to cut short any threat, the Portuguese Authorities breached neutrality by allowing the leasing of their port facilities in 1943 to the British. Therefore with the possible reinforcement of the Royal Navy, German threats vanished. This leasing was the application of the old Anglo-Portuguese Treaty of 1373. Air facilities for the RAF in the Terceira Islands were quickly bolstered.

Latter, similar facilities were also ceded, but this time to the United States, in Santa Maria Island. The Azores bases became a considerable asset for the Allied victory in the Battle of the Atlantic. Portuguese collaboration with the Allies however made the threat of an invasion even more prevalent, and the Portuguese Navy was prepared and trained more actively to face a possible naval attack against the Portuguese homeland, while the threat remained for the Azores and other Portuguese Atlantic possessions.

Vickers Wellington the Fleet Air Arm in Latje, Coastal Command 247 Group Operations in the Azores.

The Portuguese fleet soon was reinforced with 30 patrol boats and mine hunters, including the brand new Azevia class ships, and British transferred naval trawlers, plus Portuguese ones. More naval trawlers were also built in Portuguese civilian yards. A survey ship and assisting tanker Sam Brás, were also built, the latter to guarantee the wartime fuel supply to Portugal. Naval Aviation also benefited for wartime military spending, receiving more than 100 new modern aircraft. Soon the Portuguese operated a naval strike unit with land based Bristol Blenheim torpedo bombers, and later Bristol Beaufighters in 1944.

Portuguese search and rescue missions

The Portuguese Navy performed also maritime search and rescue operations during the war. There were indeed many ships sinking and survivors not far away from the Azores or in general off the Portuguese coast. Thousands of lives were saved by vessels and aircraft alike in Portuguese waters. Allied warships and merchant crews but also, from Axis and Neutral countries. In January 1943 during one such missions back from Ponta Delgada, with 119 survivors (from SS Flint and SS Julia Ward Howe), the Portuguese destroyer Lima (Lt. Commander Sarmento Rodrigues) suffered an engine failure for 45 minutes, compounded by a heavy storm. The Lima eventually tilted to 67°, to the terror of the crew and survivors, but did not sank, a testimony to the skills of the engineers. This remained a record in the history of navigation.

Overseas Portuguese Colonies

An effort was also made for overseas territories, not only in Africa, but also Asia and Oceania. Naval and military assets were limited, much more compared to what the Dutch Navy, for example, consented for the defence of the east indies.

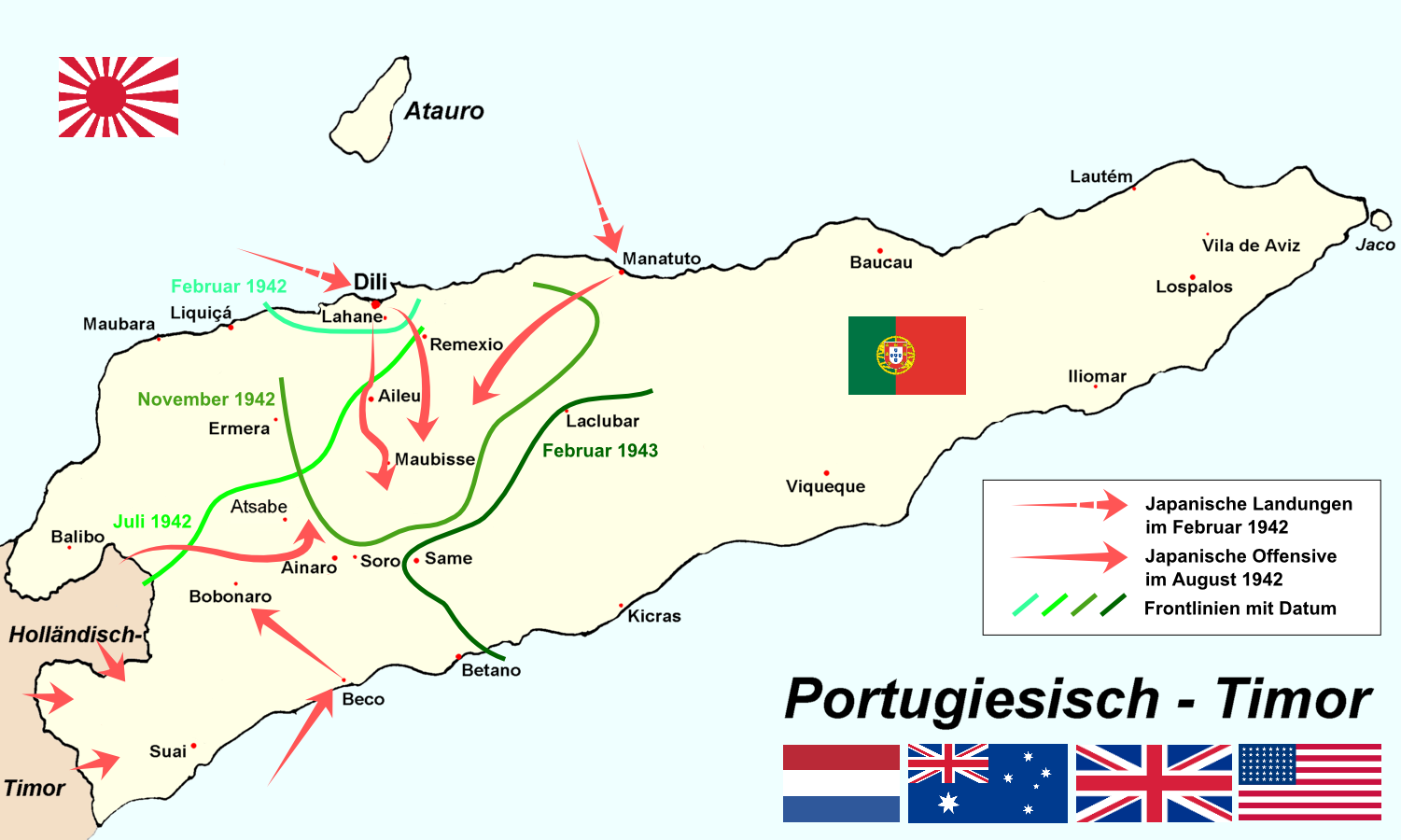

Maintaining the integrity of these possession remained possible in many areas of low strategic importance but the most risky spot was Portuguese Timor, occupied right away by Australian and Dutch forces in December 1941. The official excuse was to prevent a possible Japanese invasion, and bolster the weak local garrison.

Confronted with the fait accompli the Portuguese Government protested formally by soon an agreement was reached, in which the Allies were to withdraw after the arrival of substantial Portuguese military reinforcements. They were actually sent from Mozambique, on board the aviso Gonçalves Zarco and and freighter João Belo.

In February 1942, the convoy was still not in sight when the Japanese used the pretext of Australian-Dutch presence to invade themselves Timor. Their attack was swift and brutal, catching by surprise the Allies. Their troops, after taking heavy losses were forced to withdraw into the mountains. The Battle of Timor would last from 1942 to 1945. NRP Gonçalves Zarco was finally re-routed but would ultimately help to the reoccupation of Portuguese Timor in time. The expedition to Timor was aimed at fully restoring Portuguese sovereignty, comprising the avisos Bartolomeu Dias, Gonçalves Zarco and Afonso de Albuquerque plus three transport ships carrying 2,000 troops, heavy equipment and supplies.

The Portuguese Empire in 1939

The case of Goa and Macau

The Japanese would also attack Macao (Macau), sinking ships in the harbor. The case of Macau is interesting: The island became a refugee center in 1941, Chinese civilians fleeing the Japanese juggernaut, causing the population to climb from 200,000 to about 700,000 with serious consequences, of that we would recognise today as a “refugee crisis”, on sanitary, food, or shelter levels, and tensions rising with the locals.

Unlike Timor occupied by the Japanese in 1942 (with Dutch Timor), the Japanese at first respected Portuguese neutrality in Macau. Macau enjoyed some economic prosperity, being only neutral port in South China after Guangzhou (Canton) and Hong Kong fell. In August 1943 however, the Japanese seized a British steamer, SS Sian, in Macau, killing part of the crew in the process. A month after they asked that Japanese “advisors” be placed at the head of the Macau authorities, the only alternative given being a fully fledge military occupation. Therefore a Japanese protectorate was created de facto over the Island at that point.

Timor invasion in WW2, Wikmedia CC.

This influence went so far as to force Macau to ship aviation fuel to Japan. US intelligence, which had some spies and informers here, decided to strike. Aircraft from the USS Enterprise shelled and destroyed the hangar of the Macau Naval Aviation Centre, 16 January 1945, containing all the fuel destined to Japan. US Navy air raids went on others targets in Macau between 25 February and 11 June 1945.

This attack was never well explained by the USN, other than by a failure of intelligence, the USN official explanation was they mistakenly thought that Macau was occupied by the Japanese.

The Portuguese government protested and eventually this led to an investigation by the international community; In 1950 the Portuguese were given right, and the United States as summoned to pay a compensation of some US$20,255,952 to the government of Portugal.

The Japanese left Macau in August 1945. But the island had not long to live free and independent. In 1949 the winning Chinese communists denounced the old Protocol of Lisbon as invalid, being an “unequal treaty” forced at a time the Chinese power was weak and corrupt. But nevertheless, the Island stayed in an uneasy peace and relations with China for decades, until 1999 when it was, like Hong Kong, ceded over to China as defined by the 1987 Joint Declaration on the Question of Macau.

After the war, Portugal joined NATO and acquired 3 submarines, 7 frigates, 4 patrol boats, 16 minesweepers, 4 minelayers and 3 miscellaneous ships. But that’s another story.

Sources/Read more

Conway’s all the world’s fighting ships 1905-1921 & 1922-1947

marinha.pt/pt

infopedia.pt/ portugal-e-a-segunda-guerra-mundial

War_Plan_Gray

700 years pof the Portuguese Navy (pt)

Noticias de Portugal, Issues 557-608

Alfeite arsenal and yard history

Video of Operation Alactrity 1943 in the Azores

skydozer.com Azores-Crossroads.html

Portuguese Navy ships list

wikipedia.org Portuguese_Navy

Detailed nomenclature

Guadiana class Destroyers (1911)

Guadiana class Destroyers (1911)

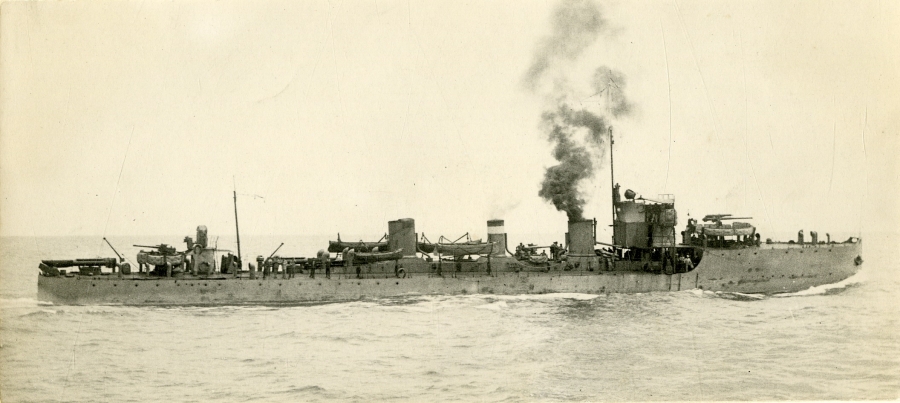

NRP Guadiana, discarded in the 1930s; The other River-class NRP Tamega was still in service during WW2.

The Douro and Guadiana were launched in 1911-12, built in Vickers as River class ships. A third, the NRP Tamega, was acquired in 1922. These 660 tons vessels, which would have been classed as second-class destroyers or coastal TDs were obsolete in the 1930s. NRP Douro (1) was discarded circa 1929, Guadiana in the 1930s, but NRP Tamega was still in service in 1939, and was discaded circa 1943. This is why this class is listed here.

Douro class Destroyers (1932)

Douro class Destroyers (1932)

These were modified versions of the British Ambuscade class, designed by Yarrow. The same company also provided the machinery for all these destroyers (Dao, Douro, Lima, Tejo, Vouga), built in Lisbon naval yard and two more, Lima and Vouga in compensation for two destroyers, NRP Douro and Tejo, resold to the Colombian navy in 1934, soon after launch, and renamed Antioquia and Caldas. In all, five were completed and in Portuguese service. They all surpassed their design speed on trials with ease, 32 knots.

It was reduced to 15 to reach their 3500 nautical miles limit. Armament as conventional, four 4.7 in or 120 mm masked guns in superfiring pairs fore and aft, two funnels, two quadruple 533 mm torpedo tubes banks and three single 40 mm Bofors for AA defence. In addition they were fitted with two deep charge throwers for ASW and rails for 20 mines on deck, launched at the stern. During WW2, their received a complement of AA, their Bofors replaced by six 20 mm Oerlikon guns while the forward TT bank was removed. They were all active during WW2 and discarded in 1959-1960.

Specs

Displacement: 1219 tons standard, 1563 tons FL

Dimensions: 93.57pp/98.45oa x 9.45 x 3.35m (307/323 x 31 x 11 ft)

Powerplant: 2 shaft parsons turbines, 3 Yarrow boilers, 33,000 hp

Speed: 36 knots, Oil 345 tons, range 3500 nm

Armament: 4x 120 mm (5 in), 3x 40mm AA, 2×4 533 mm TTs, 2 DCT, mines

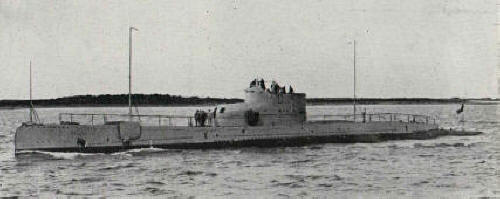

Delfim class Submarines (1934)

Delfim class Submarines (1934)

Ordered as part of the same naval plan, three Vickers-built oceanic submarines were ordered. The Delfim, Espadarte and Colginho were launched in May 1934, completed a year after. They recalled the classic “bathtub” styles British subs of the time, but smaller. Their main gun was entirely shielded. Twelve torpedoes were carried, one reload per tube. Endurance was 5000 nautical miles at 10 knots, and 110 at 4 knots. Their career was without notable incident and they were discarded in the 1950s.

Specs

Displacement: 800/1092 tons diving

Dimensions: 69,23 x 6.5 x 3.86 m (227 x 21 x 12 ft)

Powerplant: 1 shaft Vickers diesels, 2 Electric motors 2300/1000 hp

Speed: 16.5 knots surface, 9.25 underwater

Armament: 6x 533 mm TTs (4 bow, 2 stern), 12 torpedoes, 1 4-in gun (100 mm), 2 MG AA

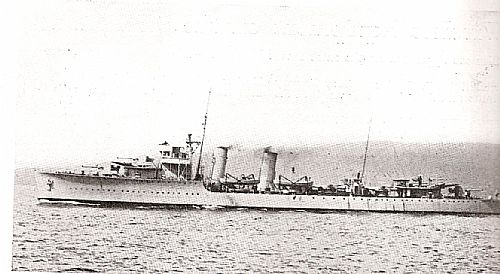

Velho class sloops (1932)

Velho class sloops (1932)

These two British-built sloops were built at Hawthorne-Leslie yards, launched in August (Gonçalvo Velho) and Novemmer 1932 (Goncalves Zarco). They were very similar to the British Bridgewater class, which were minesweeping sloops. But such was not the case here as the Velho were pure gunboats. However they carried a heavier armament and had much better range, fit for colonial stations. Their forward shelter deck allowed a superfiring “B” turret. This created topweight and to compensate, their beam was enlarged 18 inches (45 cm). Endurance was 6000 nm at 10 knots. Both exceeded their designed speed of 17 knots on trials. In 1943, like the destroyers they swapped their old 40 mm “Pom-Pom” guns for five 20 mm oerlikons. After a career without notable event they were discarded in the 1960s.

Specs

Displacement: 950 standard 1414 ton FL

Dimensions: 76.2pp/81.69 oa x 10.82 x 3.43 m (268 x 35 x 11 ft)

Powerplant: 2 shaft Parsons turbines 2 yarrow boilers 2,000 shp

Speed: 16.5 knots. Oil 470 tons, range 6,000 nm

Armament: 3x 120 mm (5 in), 4x 40 mm AA, 4 DCT

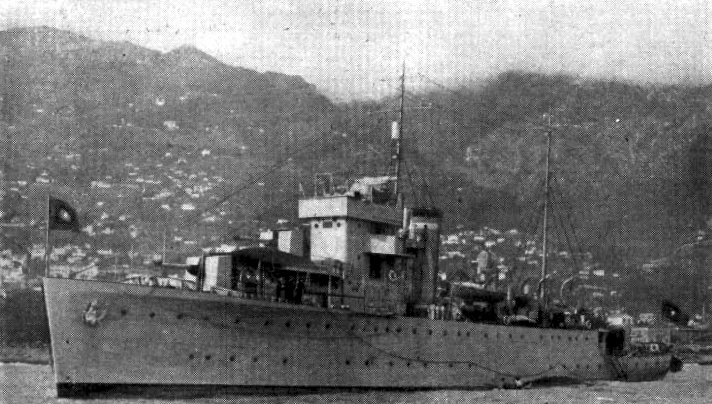

Albuquerque class sloops (1934)

Albuquerque class sloops (1934)

Contract was placed at OTO Livorno in 1931 for two gunboats, but it was cancelled in 1932 and the contract went to Hawthorne Leslie instead, providing a new, slightly more compact design, at 1,780 tons standard vs 2,100 for the Italians. These very large and powerful new gunboats were designed for colonial service, made for use in total autonomy and perform a variety of missions: They were well armed and could engage ships such as destroyers or even light cruisers, perform patrols, accomodate troops for landings operations, ASW warfare, and minelaying. They were also designed to carry and operate (but not house) a seaplane for reconnaissance, liaison, and spotting. However in practice, this was discontinuous.

As long range ship made for distant stations, the range was escellent, in the order of 10,000 nautical miles as specified, thanks limited speed to 10 knots and generous oil provision. But they were still able to ru at 21 knots if needed, served by two Parsons turbines. Both the Alfonso de Albuquerque and Bartolomeu Dias were launched in May and October 1934 respectively, in service in 1935. During WW2, their armament was upgraded: The 40 mm bofors were replaced by eight 20 mm Oerlikon guns. The Albuquerque had a singular fate post-WW2: She was one of the rare ship sunk during the cold war by gunfire, engaged by the Indian Navy at Goa in 13.12.1961 during Operation Vijay which consisted for the RIN to seize Goa, Daman and Diu by force. The Dias was hulked in 1965 and renamed Sao Cristovao.

Specs NRP Alfonso de Albuquerque as built 1935

Displacement: 1780 tons, 2440 tons FL

Dimensions: 99.60 x 13.49 x 3.81 m (326 x 44 x 12ft 6in)

Powerplant: 2 propellers, Parsons turbines, 2 Yarrow boilers, 8,000 shp

Speed: 21 knots – Range 10,000 nm @10 knots

Armament: 4x 120 mm (4 in), 2x 76 mm AA (3 in), 4x 40 mm AA, 2 DCT, 40 mines

Crew: 189

Nunes class sloops (1936)

Nunes class sloops (1936)

For the first time since a long gap, the Portuguese ordered two ships to a loal naval Yard, at Lisbon. The ships in question were two gunboats ordered in 1930, fitted with diesel for long range. Relative inexperience with suc design led the contruction dragging on for years. Joao de Lisboa was to be named Infante D Henrique originally. She was launched on May 1936, six years after the keel was laid down. The Pedro Nunes, the class lead ship, was launched two years prior in march 1934, helping to iron out many problems solved on the second while in construction.

They were small (1090 tons standard) but classic ships with a forecastle followed by a covered gallery up to the rear superstructure, one funnel, two masts, only two guns and as customary 40 mm Bodors AA, plus deep charge thrower for ASW patrols.

Tailored for distant stations, what they lacked in speed at 16.5 knots, they made it for range, carrying 110 tons of oil, allowing 6,000 nautical miles at 13 knots. During WW2 as in other ships, both the Nunes and Joao de Lisboa received 20 mm AA guns in alternative to their older 40 mm Pompom.

During the cold war they were converted as patrol ship, Nunes in 1956 and the other in 1961, and stayed in service until 1978 and 1970 respectively.

Specs

Displacement: 1090/1220 tons FL

Dimensions: 71.42 x 9.98 x 2.84 m (234 x 32 x 9ft 4in)

Powerplant: 2 MAN diesels, 2400 bhp total, 16.5 knots, 6000 nm range

Armament: 2x 120 mm, 4x 40mm AA, 2 DCT

Crew: 138

Patrol vessels

Patrol vessels

Zaire class (1925)

Zaire, Damao and Dio were 397 tons, 45 m vessels built at Lisbon Dyd, with a 700 ihp powerplant for a top speed of 13 knots, armed by two 75 mm (3 in) guns and two 47 mm (3 Pdr). They were slightly modified versions of the Beira fitted with coal-fired boilers and TE engines. In 1942 or 43, Zaire was rearmed with two 20 mm AA and two DC throwers.

Torres Garcia (1928)

This Vigo-built vessel displaced 250 tons, for a 28 m long hull, armed with probably a 3-in gun (unknown, as the powerplant). It was classed as a coastguard patrol gunboat.

Faro class (1927)

These two colonial ships built at Lisbon DyD (Faro, Lagos) in 1927 and 1930 were classed as Fishery protection vessels. They displaced 295 tons, were 36.58 m long, with a TE engine rated at 650 hp, 13 knots, armed with two 47 mm guns (3 pdr).

Azevia class (1941)

These six wartime-built fishery protection vessels were 230 tons, 41 m long, propelled by diesels which developed 2500 hp total, enough for 17 knots and a great range. The class comprised the Azevia, Bicula, Corvina, Dourala, Fataca, and Espadilha. They looks like large motor launches, armed only with two 20 mm guns and two MGs.

The WW1-era vessels, Chaimite (1898), Patria (1903) and the three Lurio class vessels (1907) has been all discarded before 1939.

Beira class:

At 463 tons, these colonial gunboats were five vessels in all: Beira, Bengo, Ibo, Mandovi and Quanza.

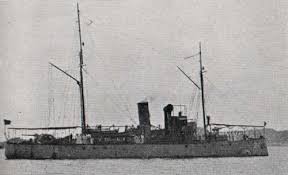

Republica class:

These 1250 tons ex-Flower class sloops of 1915, Republica and Carvalho Araujo were purchased in 1920. They were still in service in 1939. The first was discarded in 1943 and the other in 1959.

Small riverine gunboats:

Other smaller vessels used as gunboats included the Limpopo, Mineiro, Macau, Rio Minho, Vulvano, Tete, in service during WW2.

Patrol vessels (1900-12)

Patrol vessels (1900-12)

The Dili (195 tons), Lince (75 tons) of 1911, Cinco de Octubre (1900, 1343 tons), former dispatch vessel, Fishery protection vessel Carreguado (1912, 105 tons)

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign