Escort Aircraft Carriers: IJN Taiyō, Chūyō, Un’yō, commissioned 1941-42

Escort Aircraft Carriers: IJN Taiyō, Chūyō, Un’yō, commissioned 1941-42WW2 IJN Aircraft Carriers:

Hōshō | Akagi | Kaga | Ryūjō | Sōryū | Hiryū | Shōkaku class | Zuihō class | Ryūhō | Hiyo class | Chitose class | Mizuho class* | Taihō | Shinano | Unryū class | Taiyo class | Kaiyo | Shinyo | Ibuki |The first IJN escort carriers

The paradox of the history of these three first escort carriers, is that they were not designed as such in the first place. The idea was to add more fleet carriers by converting civilian ships, the most capable and conform to requirements, such as liners (larger than cargos, turbine equipped and fast). The first (Kasuga Maru, later Taiyō) was even converted before the war started, with two more following after the Pearl Harbour attack, in service by 1942, and two more single ones later, IJN Kaiyo and Shinyo. In fleet standards however, they were a poor substitute, too slow for fleet operations and lacking both a catapult and arrestor cables so they were limited to aircraft ferry missions until their refit of 1943 allowing more leeway as escort carriers albeit resuming their ferry trips anyway even after being versed to the combined fleet and Grand Escort Command. All three were attacked multiple time during their aircraft ferry missions by US submarines, and ultimately all three were claimed by these in 1943-44. #ww2 #escortcarrier #IJN #imperialjapanesenavy #aircraftcarrier #japanesenavy #taiyo #chuyo #unyo

No Escort carrier before 1943

The Imperial Japanese Navy’s stance towards the defense of its communication lines always had been secondary to its main offensive plans. The question only started to arose in late 1942 with the gradual evolution of the battle of Guadalcanal and the turn that took the Solomons campaign in general. First the focus of remaining US presence being to deprive the Japanese of their reinforcement, leading to the creation of the “tokyo express”, there were already concerns that led the Army itself to develop programs such as the Yu class Transport Submarines. The Navy meanwhile started to look at smaller escorts in 1943 to supply the lack of destroyers, and dwindling numbers of 1919 programme light cruisers hard-pressed in many theaters. From the 4 Simushu class escorts (launched 1939-40), the program was ramped up to include the Erotofu class (launched 1942) and rapidly increase with the concerns about US Submarines, when the issue about the controversial Mark 14 torpedoes had been ironed out. Losses ramped up and also the mass-construction of new escorts, to the point the program gained priority at last by mid-1944 with Type B, C and D escorts, the latter was built to no less than 68 ships. These were much cheaper, very simplified to reduce delivery delays anc comparable to the British Flower/River classes. They came alongside a similar program to the US about escort destroyers: The 1944 Matsu in Tachibana (c30 built) which happened to even too complex to make it for the numbers required.

The rise in this ambitious contruction program was concomitant to the abandonment of the coastal ASW vessels, IJN submarine chaser program, the Ch28 being the last of these (34 made), larger vessels intended for longer operations in archipelagoes. But they were still too small to be effective and correctly protect overextended communication lines to Japan. This leaved thousands of miles free of interference of Submarines, which in 1944 had understood the end point of these lines and just placed themselves in “ambush points”.

And there was of course the crowning achievement of these ASW efforts, similar to what the allies had done in the Pacific, but given the scarcity of resources of Japan for an attrition war, the numbers again, never approached what was needed: Escort carriers.

Navy and Army Escort carriers

Compared to the 100+ escort carriers built by the allies, Japan only committed …5 of these for the Navy, 5 for the army (Kumano Maru, Yamashiro Maru and Shimane Maru class, in all almost ten, half not completed in time), so ten in all “operational”. In both cases, due to the high strain on Japanese shipyards, these were all converted merchant vessels, so not to ask for dockyard space, already busy repairing more capital units. This shoulld not be surprising that the Army seems more committed into delivering more escort carriers than the Navy. After all, the task of supplying its troops was considered “not of our concerns” by the Navy which always wanted to retain the egde in offensive opertations as shown as the last large plans of 1944 and 1945 for the defense of the Philippines, Iow Jima and Okinawa. The Army had to provide for the supply of its own troops scattered across the pacific, and that meant through escort carriers and transport submarines if needed.

The Navy still was called to provide some effort, perhaps under pressure from the Emperor as “arbiter” to tame the constant bickering of inter-service rivalry. This the Navy operated the present Taiyō class, IJN Kaiyo, and IJN Shinyo. A doplet compared to what was needed. In dimensions and capabilities, they were very comparable to allied escort carriers, relatively slow at 21-23 knots, and carried c24-27 aircraft. But there again, they lacked a proper ASW aircraft. This should not be a surprise however: Nobody at the time envisioned a dedicated ASW aircraft and just used bombers with depth charge or rocket-armed aircraft for the task. The Army still had autogyro that were sort of ancestors of ASW helicopters, but they were used for experimental tests on the Akitsu Maru only. The concept never matured;

So, this is the first post on these five escort carriers this year.

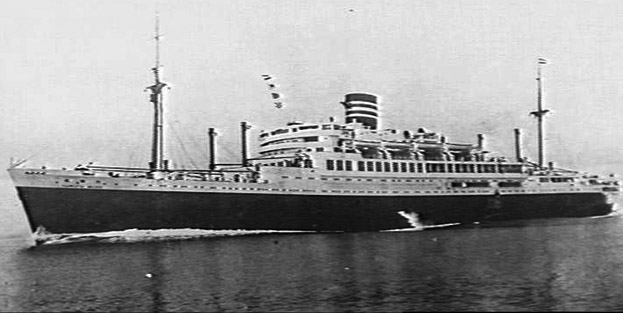

About the Nitta Maru class passenger liners

Nitta Maru

The class was converted from Nitta Maru-class cargo liners, hybrid, fast and large vessels, all built by Mitsubishi at their Nagasaki shipyard for the Nippon Yusen Kaisha (NKK) and Osaka Shosen Kaisha (OSK). Nitta Maru and Yawata Maru were completed before the December 1941. They started their sea trials well before the admiralty requested them for a conversion, as they just were prepared for their intended for service to Europe, but to avoid a possible seizure and the dangers of the Atlantic, by September 1939 it was decided to restrict their service to the Pacific. Kasuga Maru, the third, was fitting out when purchased y the IJN in 1940. She was towed to Sasebo Naval Arsenal, 1 May 1941 to reconvert her as escort carrier and ended as the first ship completed. She acted as a prototype, for further conversions as well as converted her two sisters, which was ordfered after the attack at Pearl Harbor.

Indeed, the IJN planned long before the war, since 1935 already, to built seaplane carriers or auxiliaries not under the limitations of the Washington treaty, with the idea of desigining ships that could be converted back as aircraft carriers after the war has broken. So there were plans for quick conversions already at the time. They were applied also to possible requisitioned vessels, albeit their limitation in speed compared to the seaplane carriers, fast enough for fleet operations.

Yawata Maru

The Nitta Maru-class ships displaced 17,163-gross register ton (GRT) for generous dimensions, 170 metres (557 ft 9 in) in lenght (perpendiculars), 22.5 metres (73 ft 10 in) in beam for a hold depth of 12.4 metres (40 ft 8 in). They were designed to carry morer cargo than a standard liner, and their superstructures were smaller and more compact, as well as utilitarian. So they had still a net tonnage of 9,397, cargo capacity of 11,800 tons, accommodations for 285 passengers (127 1st, 88 2nd, 70 3rd classes). They were not luxury ships, but designed for fast rotation and so powered by two sets of mitsubishi geared steam turbines, on two shaft lined, fed by four water-tube boilers. Turbines developed a total of 25,200 shaft horsepower (18,800 kW) and this was enough for 19 knots (35 km/h; 22 mph) in standard cruise, or a top speed of 22.2 knots (41.1 km/h; 25.5 mph). These figures were appealing to the Navy.

Design

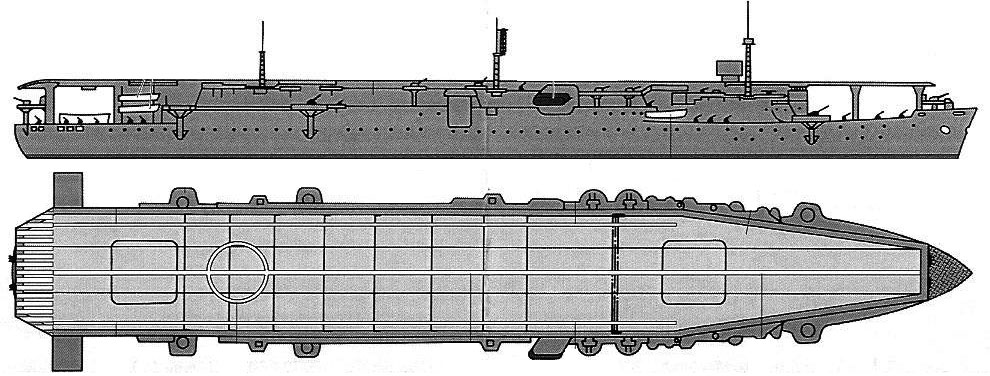

Hull and general design

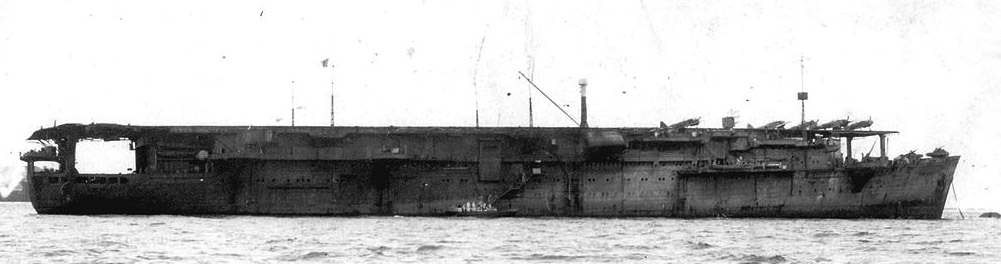

The conversion of the Taiyō-class carriers was fairly austere to be quick. A simple flush deck (no island) was just mounted above their weather hull, using the former holds as hangar, with the walls pierced through for easier communication and part of the formler internal arrangements also redone to free extra space. In the end they displaced 18,120 tonnes (17,830 long tons) at standard load due to these additions, 20,321 tonnes (20,000 long tons) at normal load. After the deck addition, they reached 180.2 metres (591 ft 4 in) overall, and if the beam did not changed, their deck width was now ported to 22.5 metres (73 ft 10 in) and draught went down to 7.7–8 metres (25 ft 3 in – 26 ft 3 in), while their crew jumped to 747 officers and ratings, up to 850 officers and crewmen including the air group pilots, officers and mechanics.

The flight deck was shorter than the overall lenght (see below), but there was not enough space to install an AA gun at the prow, however the stern was low enough to mount at least two 25 mm posts on a platform and limited traverse aft. Instead of an island, the staff commander the ship through the bridge located under the flight deck, sandwiched between it and the weather deck below. So natural light was rare, electric lighting was necessary. Plus no air operations could be directed. It was purely a ship bridge with poor visibility. At least the pilots had no obstructions, but a few antenna masts along the hull’s sponsons, three masts either side. The amidship ones carried an height finder from 1944 and the radar was installed also on a sponson forward port, on the side of the deck. Despite this limited space, every corner of real estate was used in 1944-45 to fit an anti-aircraft gun.

Powerplant

As carriers, they kept their valuable machinery which still was capable of giving them a top speed of of 21 knots (39 km/h; 24 mph). The four boiler uptakes were trunked together into a single starboard side amidship funnel which as usual downward-curved to avoid smoke interference on the deck. The original bunkerage was unknown, but as carrier, they carried 2,290 tonnes (2,250 long tons) of fuel oil, although the lead ship however seems to have only 2,250 tons of oil.

This gave them anyway a range of 6,500 nautical miles (12,000 km; 7,500 mi) at 18 knots (33 km/h; 21 mph) top speed.

Armament

Main

IJN Taiyō (former Kasuga Maru) was the first completed, and carried six single 45-calibre 12 cm (4.7 in) 10th Year Type anti-aircraft (AA) guns. They were placed in sponsons along the sides of the hull, platforms supported by pillars. The single were chosen as lighter and more compact, allowing these overhanging platforms. But as customary for other IJN carriers, they had a poor angle of fire, not cross-deck, but only defending one side. They had a top elevation of +75° for range against ships of 16,600 metres (18,200 yd) and max altitude of 10,000 metres (33,000 ft), which was above the starting trajectory for US dive bombers. They fired 20.41-kilogram (45.0 lb) shell woth a rate of fire of 10–11 rounds per minute, each leaving the barral at 825–830 m/s (2,710–2,720 ft/s).

IJN Chūyō and Un’yō were given eight more modern 40-caliber 12.7 cm (5 in) Type 89 dual-purpose guns, this time on twin mounts, sponsons along the sides, firing 23.45-kilogram (51.7 lb) shells at a muzzle velocity of 700–725 m/s (2,300–2,380 ft/s) and 8-14 rpm. With an elevation of 45° this gave them 14,800 metres (16,200 yd) in range, 9,400 metres (30,800 ft) in ceiling. But like her sister Taiyo they also had eight 2.5 cm Type 96 AA guns.

Light AA

The light AA complement comprised at the start eight Hotchkiss-derived, licence-built 2.5 cm (1 in) Type 96 guns. They were located in four twin-gun mounts, at the start two at the stern and two on either side, sponsoned on the hull. They fired 0.25-kilogram (8.8 oz) shells at 900 m/s (3,000 ft/s) with a 50° elevation and more, cimbining a range of 7,500 metres (8,202 yd) and altitude of 5,500 metres (18,000 ft). Rate of fire was slow for their catergory, at 110-120 rounds/minute as they needed non-stop feeding them with heavy, bulky 15-round magazines.

Their issues are well known, between vibrations that complicated the work of the gunner, and flash-prone ammunitions which blinded him as well. Plus as for the main guns, they only defended a limited sector. This was of course largely increased during their wartime service (see below).

For ASW defense they also carried two Depth Charge Racks, with 8 DCs in all at the stern.

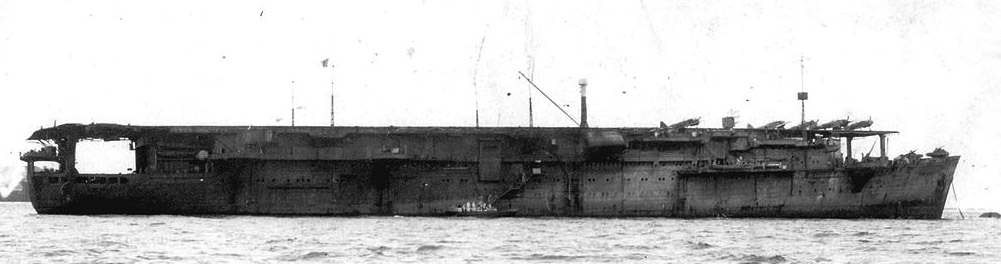

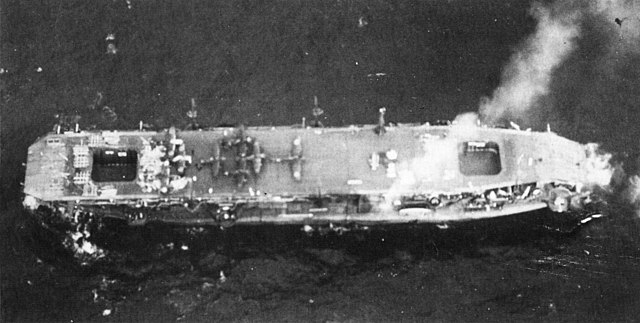

Chuyo at anchor, 1944

Upgrades

In early 1943, the four twin 2.5 cm mounts were removed and replaced by triple mounts with many more single mount Type 96 guns added as they claimed little space. Taiyō and Un’yō went to 24 guns in eight triple mounts, Chūyō had 22 guns and even five 13.2 mm (0.5 in) Type 93 AA HMGs, again less for efficience but as they took little space. To help with awareness, they received a 1st-gen Type 13 early-warning radar, placed in a retractable installation on the flight deck.

So in late 1943 had had eight triple 25mm/60 96-shiki AA guns and a single shiki 2-go radar while Chuyo had six triple, plus five single 13.2mm/76 and the 1-shiki 2-go radar, but by May 1944, IKN Taiyo also had her flight deck lengthened to 172 m (same on her sister Unyo in Augst 1944) four twin 25mm/60 96-shiki, 28 single and five twin 13.2mm/76.

In 1944, IJN Taiyō had her 12 cm guns replaced by two twin 12.7 cm Type 89 guns as her sisters, and like IJN Un’yō she received as many 2.5 cm guns as practicable to reach the amazing figure of 64 fire posts. Before that she also had the replacement of her twin for triple mounts, plus four more added but a Type 21 early-warning radar in a similar retractable installation on the flight deck and by 1944, Un’yō’s AA complement was raised also to 64x 25mm AA guns, mostly in single mounts. They had for example 12 of them along the poop deck, six on the bow deck, and the remainder in sponsons, even walkways.

Sensors

None when completed, but in 1944 they gained a 1-shiki 2-go radar, Type 13 or Type 21 early warning radars.

Type 13: This was vertical dipole 10 kW 110 kg/240 lb type grid radar with Yagi mattress receiver, fitted on the amidship mast. Its Wavelength was 200 cm, pulse Width 10 microsecond, pulse Repetition Frequency of 500 Hz. Range was 30-60 nautical miles (50-100 km). About 1000 sets were produced from 1943.

Type 21: A large 5 kW general purpose radar with greater detection range. It Weighted 840 kg/1850 lb with a mattress comprising two horizontal sets of four dipoles for the transmitter and two horizontal sets of three dipoles for the receiver.

Wavelength was 150 cm; pwdt 10 microsecond, PRF 1000 Hz. It could located an aicraft group 60 nautical miles (100 km) away, 40 nautical miles (70 km) for a single aircraft or ships up to 12 nautical miles (20 km) for a battleship. Accuracy was about a 1 mile/1-2 km with a resolution of 2200 yards/20 degrees or 2000 meters/20 degrees.

Air Group

Facilties included a 3,807 or 4,042m² flight deck (volume unknown) measuring 162 m (531 ft) on Taiyo and Unyo but 172 m (564 ft) on Chuyo (later an upgrade for the first pair), all with the same width of 23.5 m (77 feet). The hangar measured 91.5 m long, but width and height are unknown. There were 2 lifts of 12 meters by 13 meters (39 x 42 feet). Aircraft fuel stowage capacity is unknow.

Facilties included a 3,807 or 4,042m² flight deck (volume unknown) measuring 162 m (531 ft) on Taiyo and Unyo but 172 m (564 ft) on Chuyo (later an upgrade for the first pair), all with the same width of 23.5 m (77 feet). The hangar measured 91.5 m long, but width and height are unknown. There were 2 lifts of 12 meters by 13 meters (39 x 42 feet). Aircraft fuel stowage capacity is unknow.

However the greatest issue was the lack of arrester gear, meaning operations were alternative: Either taking off or landing with at deck lenght, not both. That’s whye until their 1943 refit, they mostly were used to ferry aircraft to various outposts. After their flight deck was lenghtened, they alternated between this same role and operating a covering air group for escort.

The air group varied between ships, from 27 (lead vessel) to 30 later.

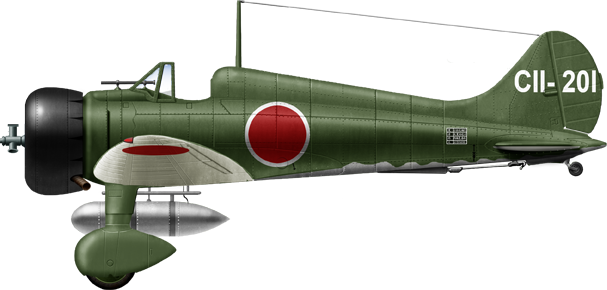

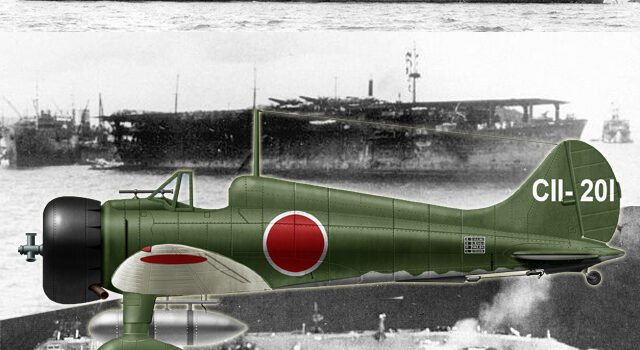

Typically, in 1942, they ventured with 11 Mitsubishi A6M2 Zero fighters and 16 Nakajima B5N2 Kate torpedo-bombers.

The lead vessel was the only one to carry (as ferry) the old Aichi D1A dive bomber, and D3A2 dive bombers as well, plus the D4Y “Judy” after 1943. But they also carried the A5M4 in these ferry missions and even the army Yokosuka K5Y “Willow” intermediate trainer, notably to Truk and Formosa airfields. Her own air group past 1943 was composed as said above of A5M2s and B5N2s, a mixed attack/defensive group that could have better fit fleet roles rather than escort roles.

It should be stressed that tactically, this air group was mostly defensive against aviation or submarines, more so than surface vessels. So the use of dive bomber, which was carried out anyway, should not have been a priority, more fitting of attack fleet carriers rather than defensive escort vessels.

A5M4 Model 56, IJN Taiyō October 1942

IJN Taiyo in 1944, with the typical green on green camouflage of the time, which silhouetted a civilian vessel (author’s).

⚙ specifications |

|

| Displacement | 18,120 t standard, 20,321 t normal |

| Dimensions | 180.2 x 22.5 x 7.7–8 m (591 ft 4 in x 73 ft 10 in x 25 ft 3 in/26 ft 3 in) |

| Propulsion | 2× shafts geared steam turbines, 4x water-tube boilers 25,200 shp (18,800 kW) |

| Speed | 21 knots (39 km/h; 24 mph) |

| Range | 6,500 or 8,500 nmi (12,000 or 15,700 km; 7,500 or 9,800 mi) at 18 knots |

| Armament | 4×2 or 6×1 5 in DP, 4×2 2.5 cm (0.98 in) AA guns |

| Sensors | 1-shiki 2-go radar (1944) |

| Air Group | Aircraft carried 27–30 |

| Crew | 747 – 850 |

Read More/Src

Books

Campbell, John (1985). Naval Weapons of World War II. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press.

Jentschura, Hansgeorg; Jung, Dieter & Mickel, Peter (1977). Warships of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1869–1945. Annapolis, Maryland: United States Naval Institute.

Peattie, Mark (2001). Sunburst: The Rise of Japanese Naval Air Power 1909–1941. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press.

Polmar, Norman & Genda, Minoru (2006). Aircraft Carriers: A History of Carrier Aviation and Its Influence on World Events. Vol. 1, 1909–1945. Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books.

Stille, Mark (2005). Imperial Japanese Navy Aircraft Carriers 1921–1945. New Vanguard. Vol. 109. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing.

Sturton, Ian (1980). “Japan”. In Chesneau, Roger (ed.). Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships 1922-1946. Greenwich, UK: Conway Maritime Press.

Tate, E. Mowbray (1986). Transpacific Steam: The Story of Steam Navigation from the Pacific Coast of North America to the Far East and the Antipodes, 1867-1941. New York: Cornwall Books.

Watts, Anthony J. & Gordon, Brian G. (1971). The Imperial Japanese Navy. Garden City, New York: Doubleday.

Links

http://www.navypedia.org/ships/japan/jap_cv_taiyo.htm

http://pwencycl.kgbudge.com/T/y/Type_21_general_purpose_radar.htm

http://pwencycl.kgbudge.com/T/y/Type_13_air_search_radar.htm

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taiy%C5%8D-class_escort_carrier

Tully, Anthony P. (2007). “IJN Chuyo: Tabular Record of Movement“. Imperial Japanese Navy Page. Combinedfleet.com.

Tully, Anthony P. (June 2007). “IJN Taiyo: Tabular Record of Movement“. Imperial Japanese Navy Page. Combinedfleet.com..

Tully, Anthony P. (January 2012). “IJN Unyo: Tabular Record of Movement“. Imperial Japanese Navy Page. Combinedfleet.com.

Model Kits

https://www.1999.co.jp/eng/image/10005491

IJN Taiyō (launched 1939, comp. 1942)

IJN Taiyō (launched 1939, comp. 1942)

Before the start of the Pacific War, Kasuga Maru already made two trips to Formosa and Palau, notably carrying Mitsubishi A5M “Claude” fighters to Palau, days before Pearl harbour. And between these transport missions, she trained naval aviators. She also carried at the time the D1A3 “Susie” dive bomber and even the Navy K5Y1 trainer, all biplanes.

Shortly after, IJN Kasuga Maru arrived at Rabaul, on 11 April but the harbour was attacked twice, she escape damage. bombed twice, although the ship was not damaged in the attacks. On 14 July, she joined the depleted Combined Fleet with Un’yō. After the landings on Guadalcanal on 7 August 1942, Kasuga Maru and IJN Yamato, escorted by two destroyers, and the 2nd, 3rd Fleets sailed for Truk.On 27 August she was detached to deliver her aircrafts to Taroa Island, Marshalls. On 30 August she resumed her trip to Truk, still under the name of Kasuga Maru at thje time, and then formally Taiyō (for “goshawk”).

In Truk on 4 September, she was ordered to Palau and Davao City as well as Kavieng but en route she was torpedoed by USS Trout on 28 September 1942. The single hit killed 13 crewmen but she had enough buoyancy to survive and reach back Truk for emergency repairs. Her mission aborted, she had to sail beck to Japan on 4 October for final repairs. Once done, she started again ferrying aircraft from Japan, to Truk and Kavieng by November and the next year, in February–March 1943, she joined her sister Un’yō and in alternative, Chūyō. While underway to Truk, she was torpedoed by USS Tunny on 9 April. Being mark 14s, they despite she received four hits, they failed to explode.

IJN Taiyō and Chūyō were escorted by two destroyers from Truk to Yokosuka on 16 April and loaded other aicraft to sail back to Truk and Mako in Formosa (Taiwan) before a refit back at Sasebo. Underway to Truk on 6 September she was again ambushed by an US submarines, this time USS Pike, but yet again, the torpedoes failed to hit or detonate. It happened again three weeks later this time by USS Cabrilla. One succeeded however, hitting her starboard propeller (it exploded), and this knocked out power. Fortunately assisting destroyers after chasing the assailant off, went back and Chūyō manage to tow her bacl to Yokosula for repairs began until 11 November 1943.

In December she was assigned to the Grand Escort Command, meaning a complete overhaul, notably with more modern AA, more AA guns, a longer flight deck, new hangar accomodations, and radars. This was completed on 4 April 1944 for her intended role of pure escort carrier, with a proper air group, and no longer an aicraft ferry. On 29 December she was ordered to join the First Surface Escort Unit, and sailed from Japan with the Convoy HI-61 from Japan to Singapore via Manila. She arrived on 18 May, and escorted Convoy HI-62 back home, arriving on 8 June, but was tasked to again carry aircraft to reinforce Manila air bases as the situation deteriorated and a TF38 attack was expected. She departed on 12 July, joined underway Convoy HI-69 and arrived the 20th.

Taiyō escorted a convoy from there to Formosa and back to Japan. On 10 August, she escorted the convoy HI-71 to Singapore, via Mako and Manila. But on 18 August she was atacked by another submarine off Cape Bolinao (Luzon) this time USS Rasher which had modified, working Mark 15. She was hit in the stern by a single torpedo and the detonation propagated to her unprotected aft avgas tank. The double explosion still was dampened. She sank still indeed in 28 minutes but carried many passengers in addition to the pilots and mechanics of her air group, so it’s estimated she had circa 400 survivors rescued while 790 went under.

Chūyō (launched 1939, comp. 1942)

Chūyō (launched 1939, comp. 1942)

Chūyō was was strangely the earliest of the class, laid down originally on 9 May 1938, launched 20 May 1939 and completed last on 25 November 1942, but she was also confined in secondary roles, like her sister an aircraft transport to and from Truk, making 13 trips in all, the first on 12 December 1942 to Yokosuka and back. She made a trip per month in 1943, rarely eventful but in April: She sailed with Taiyō escorted by the heavy cruiser Chōkai and six destroyers from Yokosuka on 4 April, via Saipan buy on 9 April, Chuyo was attacked by USS Tunny, and like for her sisters the faulty detonators of the Mark 14 torpedoes and only denting her hull so she arrived unharmed. She made tow more trips in May and August with Un’yō and had a refit on 9-18 August. She departed then on 7 September with Taiyō and while back on 24 September her sister was torpedoed by USS Cabrilla, propeller damaged, so she was towed by Chūyō for two days to Yokosuka. She was assigned to the Combined Fleet on 27 September and Grand Escort Command on 15 November but continued to ferry aircraft to Truk.

On 30 November, she left Truk with IJN Zuihō and Un’yō, escorted by Maya and four destroyers. Chūyō and Un’yō also carried 21 and 20 POWs from USS Sculpin but just after midnight on 4 December, IJN Chūyō was hit in the bow by one torpedo from USS Sailfish. The detonation severed the bow clean off, with water rushing in, while her forward flight deck collapsed as the pillars buckled. Interior bulkheads still held until the captain ordered to reverse at half speed, turned towards Yokosuka for a strange sailing over six hours until ambushed again by Sailfish at 05:55, taking a hit in her port engine room which disabled both engines and left her dead in the water. Maya and a destroyer came alongside, providing assistance until USS Sailfish launched another spread at 08:42, hitting her with one or two more torpedoes, port side again. This time no bulkhead could stip the devastating flooding and she capsized to port after six minutes carrying nearly all her crew, includinf Sculpin’s POWs. Only a few survivors survived, 161 crewmen and passengers and… one POW. While 737 passengers and 513 crewmen went with her to the bottom. She was stricken on 5 February 1944.

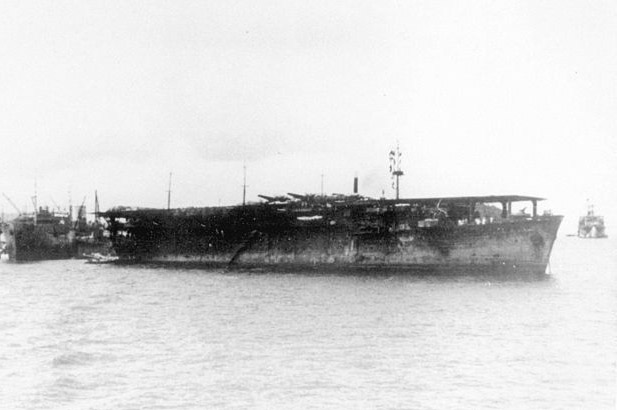

Un’yō (Launched 1940, comp. 1941)

Un’yō (Launched 1940, comp. 1941)

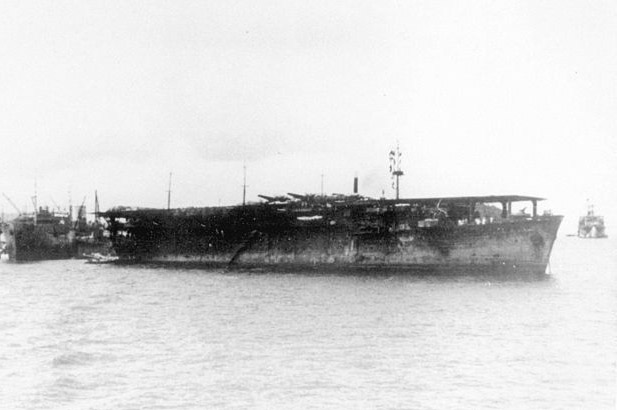

IJN Un’yō in February 1944, Yokosuka, after being damaged by USS Haddock

Un’yō was originally laid down on 14 December 1938, launched 31 October 1939 and only converted after December 1941, completed by 31 May 1942. She made three trips from Yokosuka to Truk like her sisters, often via Saipan, or to Rabaul, ferrying aircraft between July and October 1942. She notably delivered 10 Mitsubishi A6M Zero on 11 September but for her next trip stopped in the the Philippines and the Dutch East Indies, also via Palau and Truk. On 28 October she departed Japan to collect the 11th Fighter Regiment aboard at Surabaya, Java on 2 December, delivered to Truk on 11 days later as they were no longer needed on this theater of operation. She was back at Surabaya on 24 December to load 33 aircraft (IJAAF 1st Fighter Regiment) to Truk and back to Yokosuka in early January 1943.

After a short refit in Yokohama she carried 36 Kawasaki Ki-48 “Lily” bombers of the 208th Light Bomber Regiment on 1 February, brought to Truk on the 7th (the deck was jam packed, they were uunloaded by cranes). She later made multiple trips between Yokosuka and Truk and at some occasions, parired with Taiyō and/or Chūyō. On 10 July, she ferried the 201st and 552nd Naval Air Groups to Truk protected by the auxiliary cruiser Aikoku Maru when attacked by USS Halibut and USS Steelhead. Both claimed hits but … mark 14 obliges, only one hit Aikoku Maru and she survived.

The carrier made more missions until refitted at the Kure Naval Arsenal (30 September-9 October 1943) and by 30 November, she left Truk with Chūyō and Zuihō, escorted by Maya and four destroyers when ambushed by USS Sculpin (see above). Her sister went down after trying to regain Yokosuka in reverse on 4 December. Un’yō tried to take her sister in tow, until ordered to leave the area and continue to Yokosuka. Transferred from the Combined Fleet to the Grand Escort Command on 5 December, she resumed her rotations.

On 19 January 1944 while back to Yokosuka, she was hit by three torpedoes fired by USS Haddock, two detonating, shattering her bow, which still hold, sagging downwards. She entered the Garapan Anchorage in Saipan for emergency repairs, while Halibut entered to finish her off but was detected and driven off on 23 January. On the 27th she departed for Japan, slowly and escorted by three destroyers. On her way, the latter managed to repel USS Gudgeon and USS Saury on 2 February. They crossed unfortunately a bad storm and part of her bow snapped off, her flight deck collapsed, and the captain order her to reverse and steam stern-first until Yokosuka, on the 8th. Full repairs were completed on 28 June.

On 19 January 1944 while back to Yokosuka, she was hit by three torpedoes fired by USS Haddock, two detonating, shattering her bow, which still hold, sagging downwards. She entered the Garapan Anchorage in Saipan for emergency repairs, while Halibut entered to finish her off but was detected and driven off on 23 January. On the 27th she departed for Japan, slowly and escorted by three destroyers. On her way, the latter managed to repel USS Gudgeon and USS Saury on 2 February. They crossed unfortunately a bad storm and part of her bow snapped off, her flight deck collapsed, and the captain order her to reverse and steam stern-first until Yokosuka, on the 8th. Full repairs were completed on 28 June.

She was assigned 1st Surface Escort Force on 14 August and departed Moji-ku in Kitakyūshū on 25 August with Convoy HI-73, sub-chaser Kashii, six escorts and with aboard ten Nakajima B5N “Kate” torpedo bombers, six Kawasaki Ki-3 trainers from 91st Squadron to Singapore, arriving on 25 August.

She was part of Convoy HI-74 on 11 September but on the 17th she was attacked and hit by twi torpedoes from USS Barb. One opened the engine room cutting all power, the other destroyed the steering compartment, making her unable to turn. Her bulkheads held one but a storm developed and she was battered until her stern collapsed and the interior bulkheads, even shored up, failed. She started to list heavily at 07:30 to starboard until the captain ordered to abandon ship. She sank 25 minutes later southeast of Hong Kong. There were 761 survivors but sources differs as how many personal and passengers she had and how many went down with her, some saying as much as 800.

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign

Olá!

Sou Carlos Wahrlich

Estou fazendo um modelo 1/700 do Unyo. Tenho dúvidas sobre o Deck. No manual era cinza claro. Eu acho que era madeira exposta, e aqui, tem um desenho dele complexamente camouflado.

Poderia

Me ajudar neste caso?

Hi, according to Tamiya, uniform light gray indeed, i have bio refs of a camouflage (no photos). Best,