The first Japanese dreadnoughts

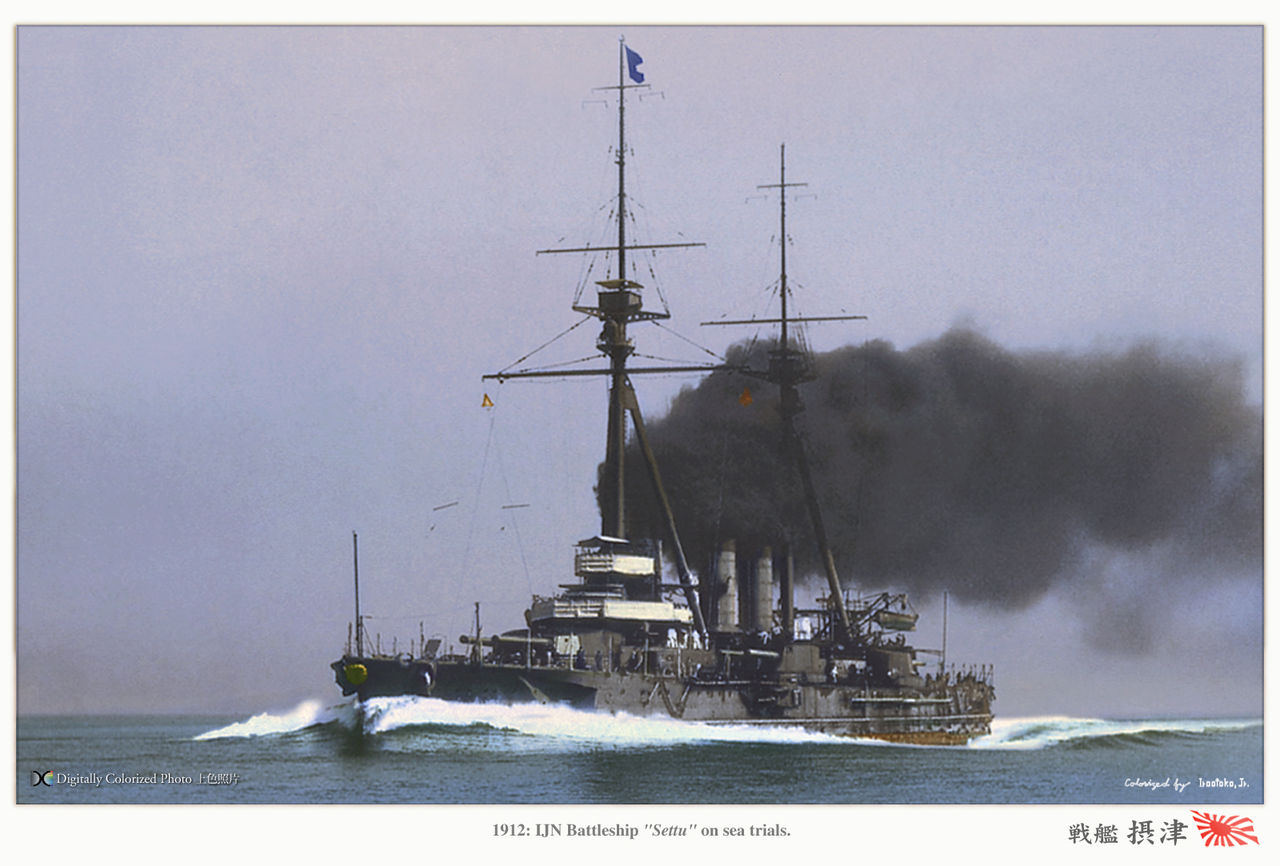

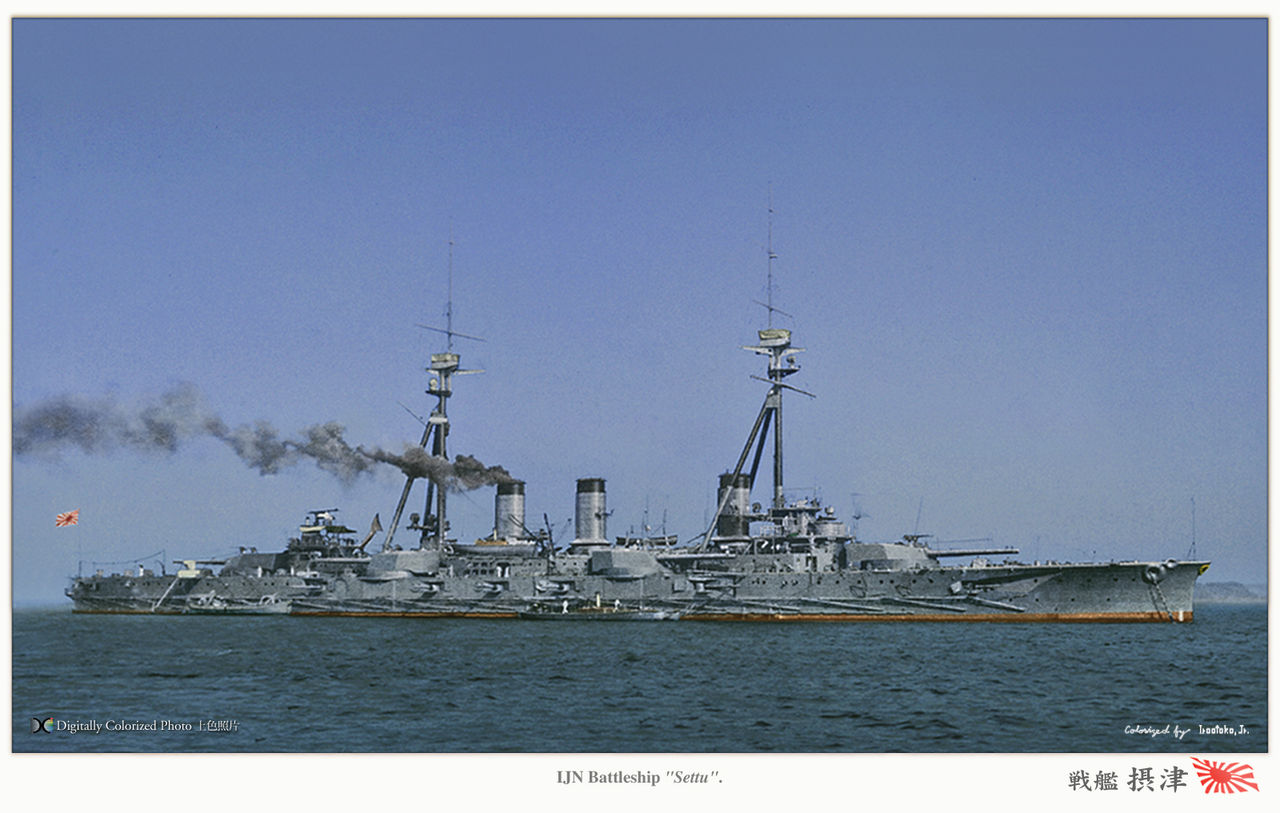

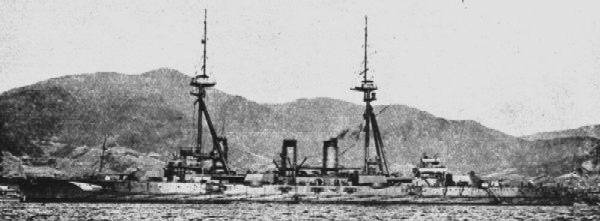

After the Satsuma class which were probably the most advanced “semi-dreadnoughts” ever designed, it was logical for Japan to move towards a true dreadnought, by just scaling up the design, notably making it more beamy. Two ships were laid down, but in 1909, and programmed in 1907, so well after HMS Dreadnought was launched, and known to the world. The two 20,000 tonnes, 21 knots battleships, IJN Kawachi and Settsu, unlike their successors, had a short active carrer. They saw little action in 1914, and Kawachi sank due to an accidental explosion in 1918 and in 1922 due to the Washington Treaty Settsu was converted as a target ship, still around in 1945.

Design

Design Development

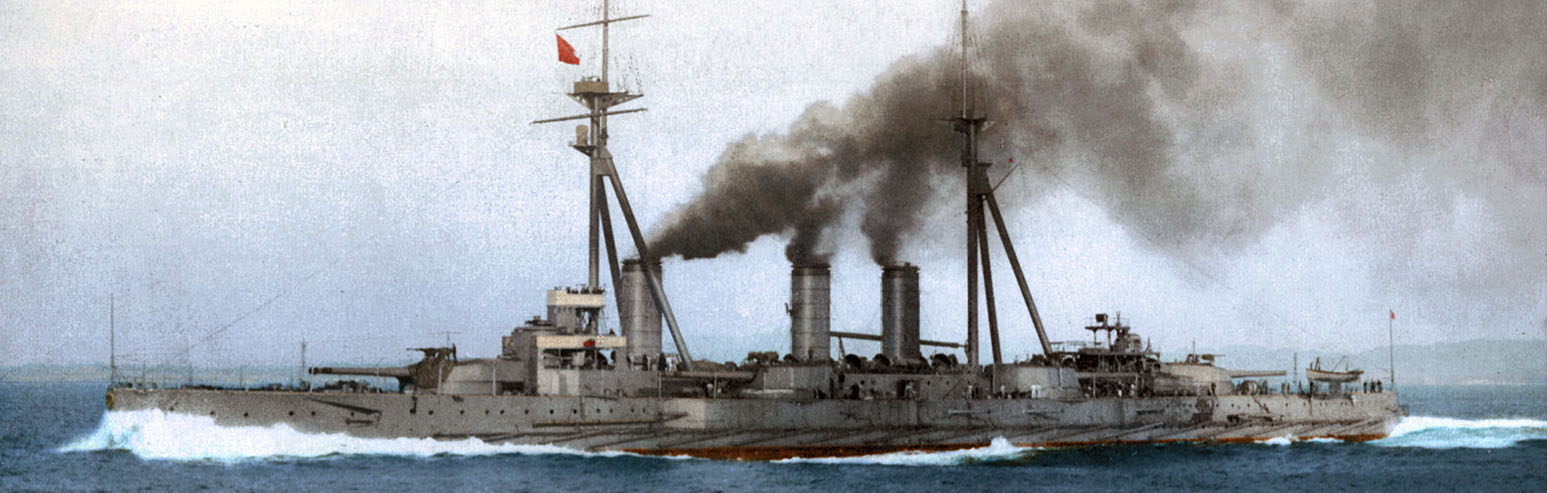

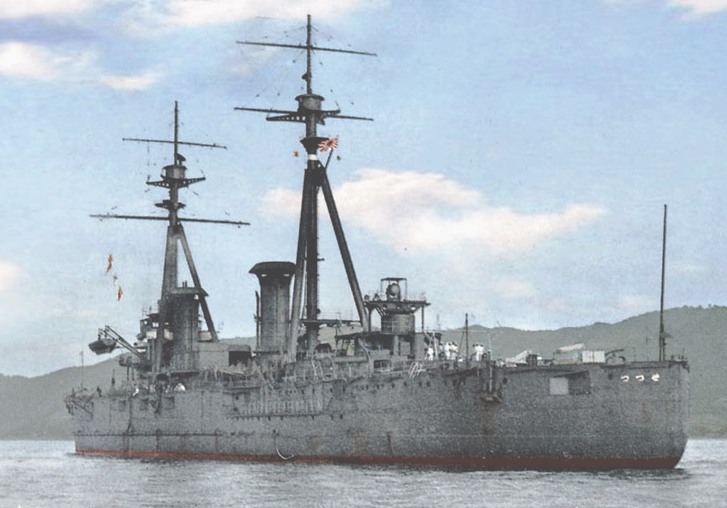

The previous IJN Aki (Brasseys)

The Kawachi class was ordered on 22 June 1907, under the 1907 Warship Supplement Program, motivated by bolstering the Navy after the Russo-Japanese War. As HMS Dreadnought was launched on February 10, 1906, the entire world took notice and naval history took a turn. Its construction was kept secret in Britain even to the very close Japanese, in alliance since 1902, and for the construction of the Satsuma class, the first built in Japan, it was done under extensive British technical assistance, base based on the Lord Nelson design. The Japanese however was an avid reader of international publications and in 1903 knew about Cuniberti’s article on a large monocaliber armoured cruiser.

Construction of the Kawachi class though was delayed by a severe depression but they were first steps in the just adopted “Eight-Eight” Fleet Program. It required a fleet of eight dreadnoughts and armored cruisers, but an enormous cost for Japan, eating an insane amount of GDP to modern standards. To gain time, engineers just evolved the IJN Aki, second vessel of the Satsuma class and improved compared to her sister ship. The step to take was simple: Simply replacing former secondary turrets with large 12-in twin turrets, for an uniform 305 mm main-gun battery in the early hexagonal layout used also by German engineers (Nassau and Helgoland), rather than adopting the Dreadnought’s (and its successors) inline turrets and two on the wings. This gave them an advantage of two guns (12 versus 10), but with firing arc restrictions.

At an age were superfiring turrets were just dreamed of, it was the most rational design. However the final Kawachi class emerged from a sucession of designs, in a process that started in June 1907, but only was completed after nearly two years, in April 1909. All this tme saw much discussions going on and the first iteration had six twin-gun turrets, but with a bold “paper solution” of two pairs of superfiring turrets fore and aft plus two amidships “en echelon”, just like the future German Kaiser class.

On paper this maximized firing arcs but the layout was rejected as exceeded the informal 20,000 long tons limit fixed by the diet for the design, and cost in an already stressed budget. In addition there was no technical expertise for superfiring turrets at the time, in Japan, but in Britain (see the Rio de Janeiro class) and the US with their North Carolinas. The design was revised to the more familiar hexagonal layout, and the choice went on the already proven 45-caliber 12-inch guns of the Kawachi class now produced in Japan.

By early 1908, the IJN however received reports about development of a longer 50-caliber gun for future RN battleships and so the Chief of the Naval General Staff Admiral Tōgō Heihachirō, wanted these. This again went against cost considerations, but still, a heated discussion led to their adoption for the fore and aft turrets as a compromise. Meaning the four wings guns would have a lower range, a return to the pre-dreadnought formula in a sense.

This set them apart future designs and foreing ones at the time.

After extra tweakings on many details the final design was adopted by the admiralty in January 1909 and followed for the search of a suitable yard: Yokosuka and Kure were naturally contracted as the only ones capable of building the new large vessels. In the end, they were just 1,000 tonnes heavier than the Kawachi, ten meters longer, and just 20 cm larger (7.8 in). This was nothing short of amazing given the enormous upgrade in capabilities, but limited to the actual basins Japan possessed. Still, it can be viewed as an engineering prowess.

Final design

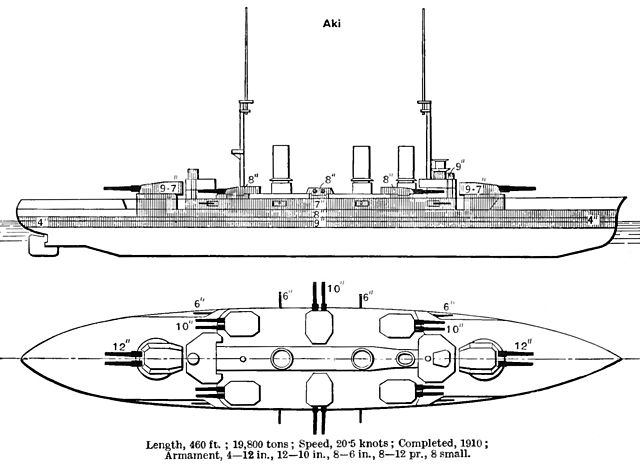

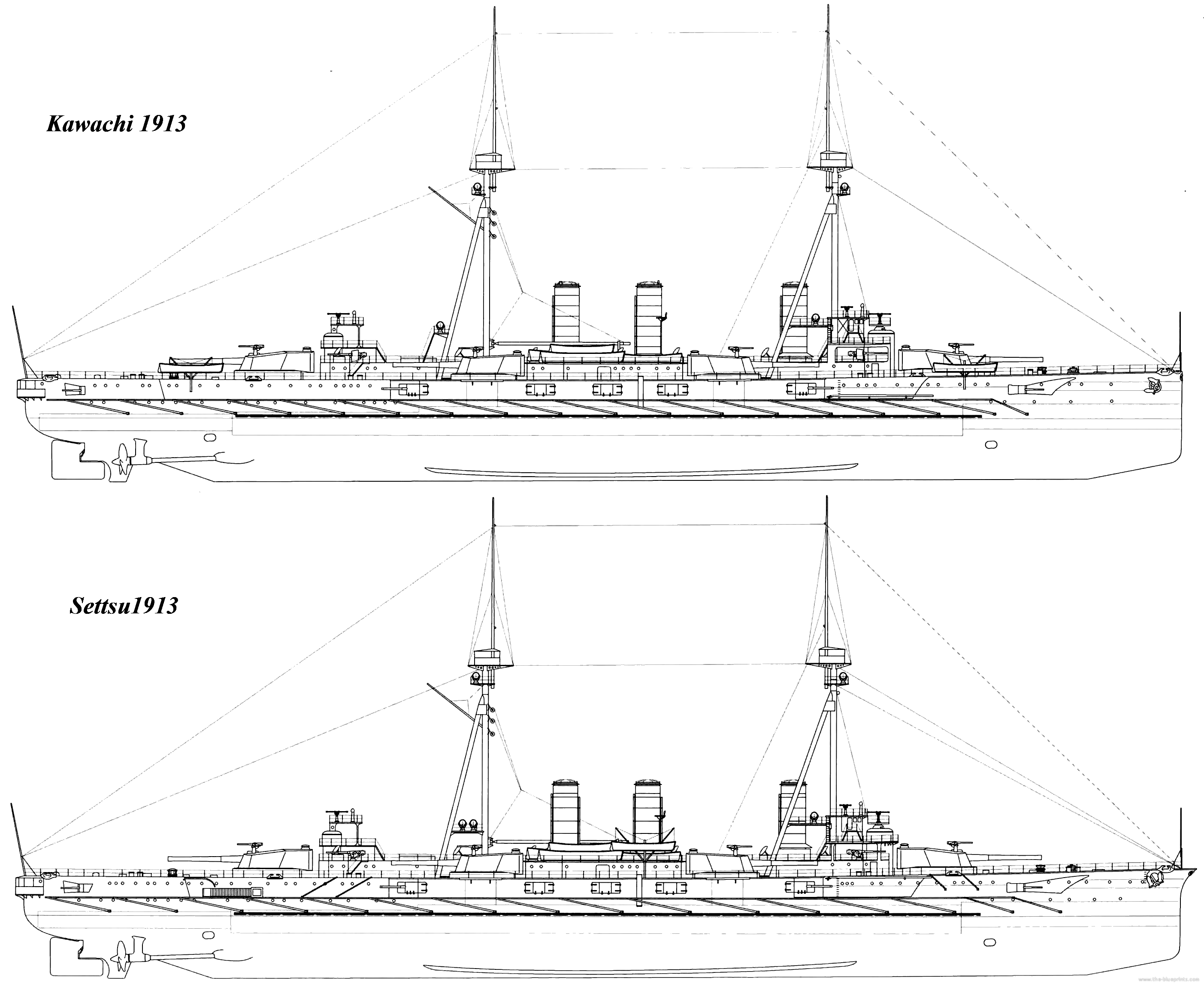

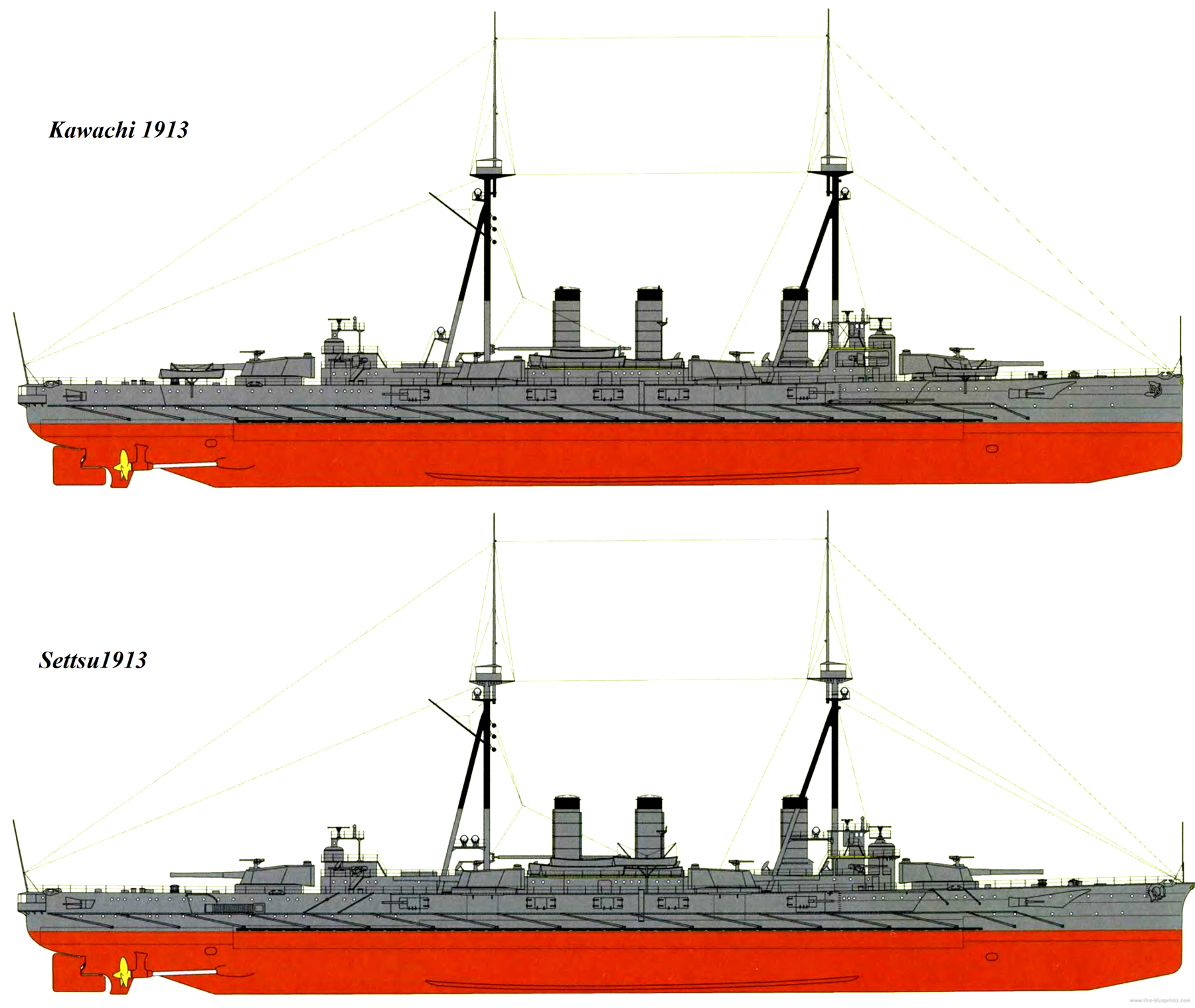

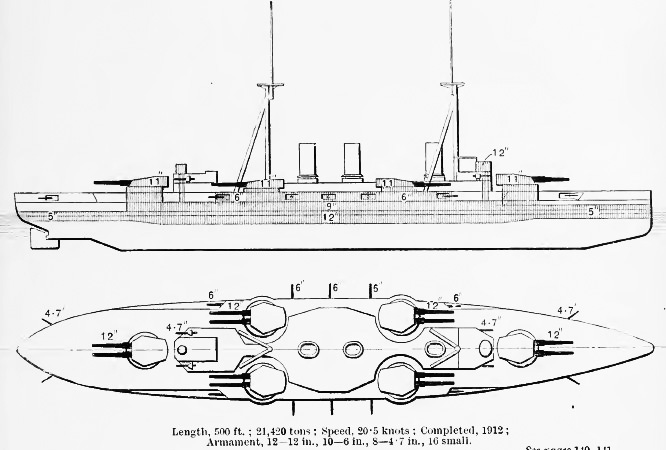

Kawachi and Settsu in 1913 (the blueprints)

The final Kawachi class battleships were much heavier than the HMS Dreadnought, longer, and broader of almost 27 inches (70 cm), with the same speed and two extra guns, the shapes were much “full” at the beam, and to compensate for the beamier hull and extra weight, engine power was beefed up.

The two vessels diverged in many points though: Kawachi was designed with a straight bow, but Settsu adopted the same clipper bow designed for the previous Satsuma class. This was mostly for comparative tests. Over, however, both were externally virtually identical, notably for their funnels, three with a pair aft and a third one forward further apart. Overall, they reached 526–533 feet (160.3–162.5 m), for 84 feet 3 inches (25.7 m) in beam and a normal draft of 27–27.8 feet (8.2–8.5 m). Displacement standard was 20,823–21,443 long tons (21,157–21,787 t) normal, possibly 23,800 fully loaded (figures are not known). Their metacentric height was 5 feet 3 inches (1.59 m), partly thanks to the adoption of all-deck turrets. The crew diverged between ships and peacetime/wartime, from 999 to 1,100 officers and ratings.

Both had a rather long superstructure, going from the bridge forward, comprising a conning tower, with the bridge located behind and above, open bridge on top, and wings. The superstructure was then interrupted and maded narrow due to the needed space for the beam turret to make a full 280° traverse with the longer turret bustle inwards, reducing the available space to a simple catway and the funnels with their air scoops were located in between. The superstructure ended with the aft bridge and it’s own conning tower, plus a platform supporting four projectors.

Another major difference with the previous Satsuma class was that due to the longer guns, the range was expectedly longer, requiring taller spotting tops for gunnery accuracy. For rigidity, with the higher tops it was decided to reinforce them by installing tripod masts for the first time on IJN battleships. The Fuso and Hyuga would stick to this formular until the Nagatos and their unique heptapodal masts. The legs of the tripod in fact had no use supporting the tops, but just supported the main vertical mast. Forward was installed a platform for a projector, added to the ones aft. Both vessels carried a fleet of small boats, some installed on davits aft and amidship, and the rest located on the admidship superstructure abaft the two funnels. They were managed by a boom fitted on the aft mast.

Propulsion

Kawachi and Settsu in 1917 (the blueprints)

Satsuma had 20 Miyabara boilers for 17,300 ihp, her sister Aki had a new model of boilers with just 15 giving 24,000 ihp. Engineers naturally looked at this later powerplant to improve it. Both vessels would have the same boilers, but 16 instead of 15, for a total output of 25,000 shp (19,000 kW), a net gain of 1,000 ihp allowing them to keep the minimal 21 kts asked for. They would be however unable to reach 23+ kts like IJN Aki on trials.

The was no debate about the propulsion system at the time, even though in 1907-1908, Japanese engineers were well aware of the adoption of turbines by British vessels. There was no technical expertise on these (yet) in Japan but despite the price asked by the British for their own turbines, it was still more attractive than keeping the proven VTE (triple expansion) system adopted by IJN Satsuma. Thus, license-built Curtis steam turbine sets like on IJN Aki were reused.

Each turbine drove a single propeller, and steam came from 16 Miyabara water-tube boilers working at 17.5 bar (1,750 kPa; 254 psi). The powerplant was rated for 25,000 shaft horsepower (19,000 kW) and the design speed of 21 knots (39 km/h; 24 mph) was met in trials, as the turbines proved to be more more powerful than designed, giving Kawachi 30,399 shp (22,669 kW) and Settsu even 32,200 shp (24,000 kW), far more than expected. Speeds reached on trials are not known. Based on this it’s not impossible 22.5 kts was the realized figure. For autonomy both carried 2,300 long tons (2,300 t) of coal, 400 long tons (410 t) of fuel oil for 2,700 nautical miles (5,000 km; 3,100 mi) at 18 knots (33 km/h; 21 mph).

Protection

Brassey’s drawing of the class in 1912

That’s not on this chapted engineers innovated the most. They repeated the scheme already adopted for IJN Aki, with heavier thickness figures: The Krupp cemented armor originally of 9 inches (229 mm) amidships reached 12-in, but was tapered down to 5 inches (127 mm) instead of 4 inches (102 mm) inches at both ends, outside the citadel. The main belt extended 6 feet 4 inches (1.93 m) above and 6 feet 5 inches (1.95 m) below the waterline, a bit more than the Satsuma class.

The upper belt was continued by a strake of armor 8 inches (203 mm) covering the upper sides up to the middle deck, and abive was a strake of armor to protect the casemates of 6-in (152 mm), like the prvious battleships. As for the main armored deck, it reached 1.1 inches (29 mm) thick, less than the Aki’s deck armor, of 2–3 inches (51–76 mm) thick. Conning towers reached 10 inches (254 mm) for its walls, better than the 6-in figures of the previous Aki.

Main guns were raised from 8-9 in for the Satsuma and Aki to 11 inches on the Kawachi, with a 3-inch roof. Barbettes which previousy were 7–9.5 inches (180–240 mm) thick also reached 11 in (279 mm) above the weather deck but 9 inches (229 mm) below it. The casemates for the secondary guns were also 6-in thick.

- Waterline belt: 5–12 in (127–305 mm)

- Deck: 1.2 in (30 mm)

- Gun turrets: 11 in (279 mm)

- Conning tower: 10 in (254 mm)

- Barbettes: 11 in (279 mm)

Armament

Main 12-in gun Type 41 at Kashii Guu Temple

Outside the same six twin turrets the main change as seen above was the adoption of different barrel lenght for the main guns, all of the 12-in (305 mm), with /50 caliber guns fore and aft and /45 for the wings turrets. For the secondary armament, it was inspired by the IJN Aki, not Satsuma which started with twelve single 4.7 in (120 mm) guns. Thos of Settsu were ordered from Vickers, but the rest were built in Japan. This made for a 50-caliber Type 41 ranging to 24,000 yards (22,000 m) and the 45 caliber Type 41 to 21,872 yards (20,000 m) with a muzzle velocity of 3,000 and 2,800 fps. Both fortunately fired the same 850-pound (386 kg) armor-piercing (AP) shells. elevated to +25° and could be reloaded up to 13°.

Like Aki, they adopted 6 in (152 mm) guns for their main secondary battery, but ten instead of eight. Yet still, they kept a lower tier secondary battery of eight 4.7 in guns Type 41, making a much serious proposition than Aki or Satsuma. This was an usual solution that complicated supply, but was trusted to deliver various ranges and rate of fire for closer combat.

Light armament was traditionally revolving around two calibers: Twelve 3.1 in Type 41 (On Conways 12-pdr or 3-in/76 mm), like on the longer IJN Aki, of 40 caliber, and like the previous vessels four of the same but 28 caliber used as saluting guns. Just also like the previous vessels they adopted five 18-in torpedo tubes (457 mm), one bow, one stern and four in the broadside with three reloads each. These 24 Type 43 torpedoes had a 209-pound (95 kg) warhead and single range setting of 5,500 yards (5,000 m) at 26 knots.

- 2×2 12 in/50 (305 mm) guns

- 4×2 12 in/50 (305 mm) guns

- 10× 6 in (152 mm) guns

- 8× 4.7 in (120 mm) guns

- 8× 12 pdr/3-in (76 mm) guns

- 5× 18 in (457 mm) torpedo tubes

⚙ Settsu class specifications |

|

| Dimensions | 162.5 x 25.7 x 8.5 m (533 x 84ft 3in x 27ft 8in) |

| Displacement | 20,823-21,443 tons standard |

| Crew | 999-1100 |

| Propulsion | 2 shafts Curtis turbines, 16 Miyabara boilers, 25,000 shp. |

| Speed | 21 knots (39 km/h) |

| Range | 2,700 nm @ 18 knots (5,000 km; 3,110 mi). |

| Armament | 6×2 12-in/50/45, 10x 6-in, 8x 4.7-in, 8x 12 pdr, 5x 18-in TTs (457mm) |

| Protection | Belt 5–12 in, deck 1.2 in, Gun turrets 11 in, CT 10 in, Barbettes 11 in |

Sources/read more

Books

Gardiner, Robert & Gray, Randal, eds. (1985) Conway’s all the world’s battleships 1906-1921

Gibbs, Jay (2010). “Question 28/43: Japanese Ex-Naval Coast Defense Guns”. Warship International.

Gibbs, Jay & Tamura, Toshio (1982). “Question 51/80”. Warship International XIX

Hackett, Bob & Kingsepp, Sander (2009). “IJN Settsu: Tabular Record of Movement”. Combinedfleet.com.

Jentschura, Hansgeorg; Jung, Dieter & Mickel, Peter (1977). Warships of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1869–1945.

Lengerer, Hans (September 2006). Ahlberg, Lars (ed.). “Battleships Kawachi and Settsu”.

Lengerer, Hans (June 2010). Ahlberg, Lars (ed.). “Battleships of the Kaga-Class and the so-called Tosa Experiments”.

Lengerer, Hans & Ahlberg, Lars (2019). Capital Ships of the Imperial Japanese Navy 1868–1945: Ironclads, Battleships and Battle Cruisers

Preston, Antony (1972). Battleships of World War I: An Illustrated Encyclopedia of the Battleships of All Nations 1914–1918.

Silverstone, Paul H. (1984). Directory of the World’s Capital Ships. New York: Hippocrene Books.

Links

combinedfleet.com/Settsu

combinedfleet.com/Kawachi

On timesmachine.nytimes.com

Article on frove.nla.gov.au

worldnavalships.com

On battleships-cruisers.co.uk

wrecksite.eu

Video Kawachi class – Dreadnoughts of the Rising Sun: A World War I Naval History

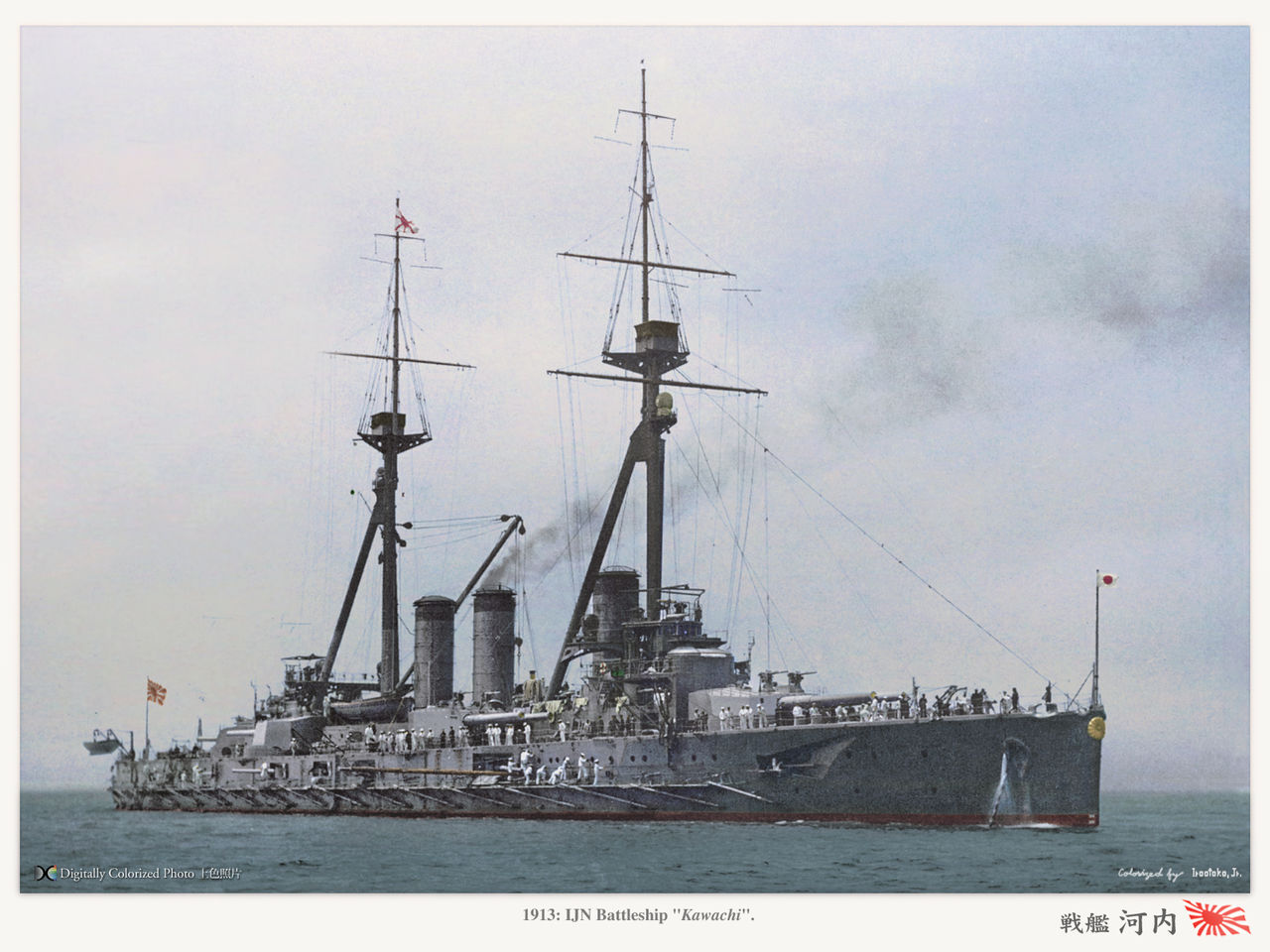

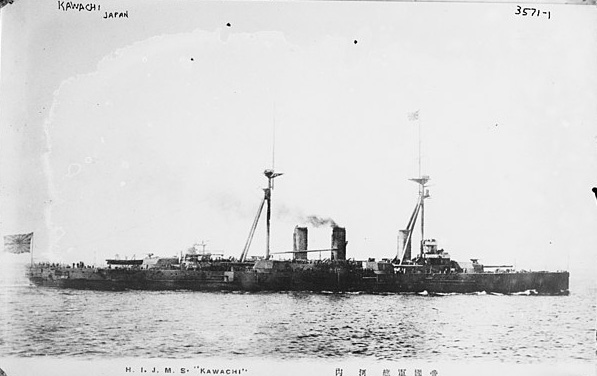

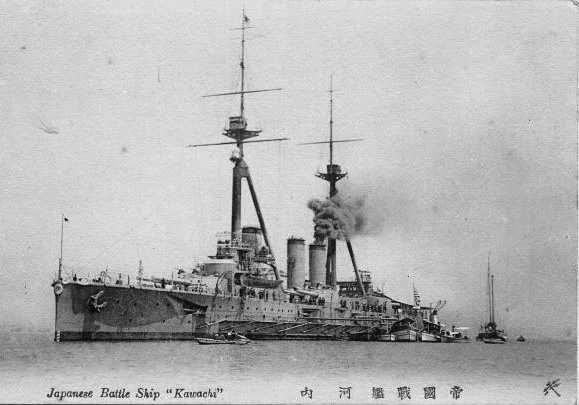

Colorized photos of the Settsu and Kawachi

Model kits

Only found: Navis 203K Japanese Battleship Settsu 1/1250 Scale Model Ship Unpainted Kit.

Service records

IJN Kawachi

IJN Kawachi

A relativeley uneventful career 1912-1918

IJN Kawachi, namd after the province (Osaka prefecture) was laid down on Slipway No. 2, Yokosuka Naval Arsenal, 1st April 1909. Launched on 15 October 1910 in a major state ceremony where Emperor Meiji was present, she was completed on 31 March 1912. Total construction cost has been ¥11,130,000. After a short shakedown cruise and initial training she joined the First Fleet as flagship, Vice Admiral Dewa Shigetō. On 3 October 1912 she witnessed IJN Mikasa’s dramatic fire in her forward magazine, quickly flooded, while Kawachi sent her own fire-fighting teams. She was operating in the South China Sea in February 1913, and north China coast in next April 1913 but was reconverted as a private ship on 1 December for the Royal Family, cruising in 1914. But in August 1914, she was in overhaul in Yokosuka.

She was sent with Settsu to Tsingto, where the siege begane earlier, adding their 24 heavy guns to reduced German fortifications to rubble in October–November 1914 before the final assault. Back in Yokosuka on 8 January 1915 she was with the Second Squadron returning from Tsingtao, but was reassigned assigned to the 1st Squadron, 1st Fleet, on 15 August and by December 1916 started her sole career major refit.

After it was done, under command of Captain Masaki Yoshimoto she was reassigned to the 2nd Squadron, 1st fleet on 1 December 1917, flagship, Rear Admiral Chisaka Chijirō, cruising in the China sea in early 1918 and by May two 3-inch casemate guns were removed and plated over, replaced by same caliber AA guns. On 11 July she was in Tokuyama Bay due to rough seas.

The loss of Kawachi (11 July 1918)

At 15:51 this day, a massive explosion was seen close to her starboard forward main-gun turret, bellowing enormous quantities of smoke, with extra smokle coming from between the 1st and 2nd funnel and after two minutes she started to list starboard, and the movement was unstoppatble, until she capsized after just four minutes, unfortunately with a thousand men aboard. More than 600 were trapped inside, but she still had 433 survivors, almost miracuslous given the circumstances.

The IJN commission presided by Vice Admiral Murakami Kakuichi as chairman suspected arson given what happened to Mikasa, but the enquiry found no plausible suspect and knowing about similar incidents, suspected the cordite decomposition might have been the probable cause. Her magazines were toroughly inspected in January–February but still no proof or an anomaly was found. In the end, the accident led to order a tighter control of production, storage and handling of cordite. Kawachi could have been salvaged and repaired, but due to budget constraints, it sounds far more judicious to ficus on the new Amagi-class battlecruisers. Kawachi was stricken on 21 September 1918, dismantled until she was no longer a hazard and the remains left in place as an artificial reef.

IJN Settsu

IJN Settsu

As a battleship (1912-1922)

IJN Settsu was laid down at Kure Naval Arsenal on 18 January 1909, launched on 30 March 1911 with less fanfare (and also named after a province), completed on 1 July 1912 for ¥11,010,000, less than her sister. Captain Morihide Tanaka took command on 1 December as she was sssigned to the 1st Squadron like her sister. 1913 was spent training and patrolling off China and in August 1914 she was Kure for a small overhaul. She was sent with Kawachi to shell Tsingtao before the final assault.

At her return she saw limited service and she was placed in reserve from 1 December 1916 for another refit in Kure, ending on 1 December 1917, from which she was reassigned to the 2nd Squadron and on 23 July 1918 returned to the First Squadron, this time alone as her sister was lost due to an explosion. All her 3-inch 4th Year Type guns were removed as two TTs, and replaced by four 3-inch 4th Year Type AA guns and by 28 October she became flagship for the Emperor Taishō, taking part of the Yokohama naval review of 9 July 1919.

Placed in reserve on 6 November 1919 to receive her major overhault, she had her old boilers removed and replaced and emerged on 21 August 1921, being a provate ship when she carried Empress Teimei back to Tokyo after she toured shrines in Japan for the Emperor’s health. She weathered a typhoon and was disarmed in Kure in 1922 due to the signing of the Washington Naval Treaty, then stricken on 1 October 1923.

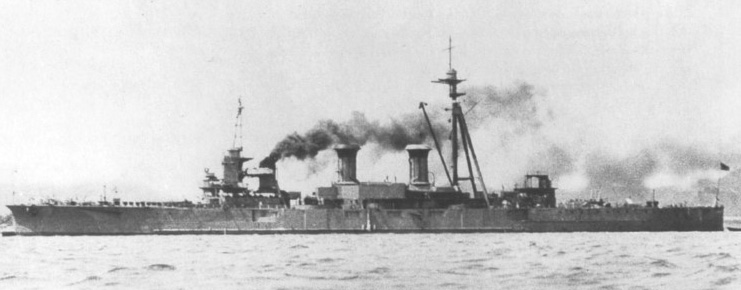

Second life as a target ship (1925-45)

Work started to have her converted as a utility hulk, with her artillery and armoure dismantled as the treaty conditions. The Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) obtained her precious 12-in guns, turned into coastal artillery: Two of entire turrets were placed on Tsushima Island converted as a “concrete battleship” in 1936. The others were stored in reserve. They were scrapped for spare metal in 1943. In 1923, Settsu was ataken in hands for her conversion as a target ship, loosing one boiler room and center funnel, but having her armor reinforced to the latest standard in order to resist to the most recent heavy cruisers shells and (66 lb/30 kgs) aerial practice bombs. Now reduced to 16 knots (30 km/h; 18 mph) for 16,130 long tons by February 1925 when completed she towed the cancelled Tosa, badaly damaged after gunnery/torpedo tests to the Bungo Channel to be scuttled.

Settsu as radio-controlled target ship at anchor on 7 April 1940

In 1935-1937 after years of tests, she was taken for a new overhaul, equipped with a brand new radio-control set, in order to be a moving target. Operators manoeuvered her since the destroyer IJN Yakaze dueing the first of these, and she received extra armor on the deck as well on her funnels and bridge.

In August 1937, under command of Captain Naomasa Sakonju, she was remobilized as a troop carrier, carrying the Sasebo 4th Special Naval Landing Force to Shanghai as part of the Sino-Japanese War operations. These were later transferred to the less drafty light cruiser IJN Natori and destroyer IJN Yakaze and convoyed on the Yangtze River whikle Settsu sailed for home. In 1940 she was again converted as a specialized target for aviators. With extra armor on her deck and markings, she was used as a target by D3A pilots in particular preparing for the Pearl Harbor Operation. Later she took part in a fleet review for Emperor Hirohito on 11 October 1940, in Tokyo Bay.

Settsu as radio-controlled target ship, colorized by irootoko JR.

In early 1942 while under command of Captain Chiaki Matsuda she was in Taiwan, and proceeded to the Philippines, simulating fake radio traffic coming from the Kido Butai, accompanied by the Zuihō and Ryūjō, a deception that mostly worked. Until 1945 she was stationed in the Inland Sea, still used for realistic training for IJN pilots training. In March–June 1944 for example, the 522nd and 762nd Naval Air Groups operated with her, but due to more frequent US aviaion raids she was armed with several Type 96 light AA guns as well as depth charges and hydrophone to located US Submersibles.

She was present in Kure during the massive air attack of 24 July 1945, and no les than thirty Grumman F6F Hellcat fighters targeted her after being located off Etajima. She was hit by a single bomb, killing two and five near misses. Damage led to a slow floodding of her starboard engine room. Captain Masanano Ofuji wanted to run aground at Etajima. After this was done, her 25 mm guns were removed, she became a barracks ships, but after four days USN planes attacked her and she took two bomb hits. The captain ordered to abandon ship later, and she stricken on 20 November. In June 1946 her hull was towed to Kure for scrapping, completed on August 1947.

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign