HMS Agincourt (ex-Rio de Janeiro, ex-Sultan Osman I) 1913

HMS Agincourt (ex-Rio de Janeiro, ex-Sultan Osman I) 1913WW1 RN Battleships

HMS Dreadnought | Bellerophon class | St. Vincent class | HMS Neptune | Colossus class | Orion class | King George V | Iron Duke class | HMS Agincourt | HMS Erin | HMS Canada | Queen Elizabeth class | Revenge class | G3 classMajestic class | Centurion class | Canopus class | Formidable class | London class | Duncan class | King Edward VII class | Swiftsure class | Lord Nelson class

Invincible class | Indefatigable class | Lion class | HMS Tiger | Courageous class | Renown class | Admiral class | N3 class

The ‘Gin Palace’

HMS Agincourt was singular ship. Not only became a worldwide sensation by its unusual configuration, but she also changed hands three times: Ordered originally by Brazil (Rio de Janeiro) to counter Argentina, she was cancelled, repurchased by Turkey, and then requisitioned in August 1914 by the government. She was tailored to retake naval superiority in south america after the Ridavia class was ordered, and therefore was designed over a 30,000 tons fully loaded loaded displacement, while the length reached two hundred meters overall, in order to stack no less than than fourteen 12 inches guns (305 mm). Events had this arms race ended by a government change.

Turkey had a new deal signed, until the battleship was requisitioned and eventually commissioned as HMS Agincourt. She would take part in all RN operations of the war, including the battle of Jutland, but was no longer relevant in 1918, sold for BU in 1922, so barely ten years after launch, leaving only her memory, the “Gin palace” showcasing the most impressive broadside of any British battleship up to this day.

Context of the order: The South-American arms race

Following the 1889 coup in Brazil which saw Emperor Dom Pedro II deposed, there was a revolt from the loyalist navy in 1893–94 navy. As a result, ships fell under neglect while no provision was made either to purchase more. Chile, an old rival, superseded by Argentina, was part of the early arms race, and due to the strain it took on its budget, agreed to a naval-limiting pact in 1902 with Argentina. This including them keeping their best and most recent ships, alarming the Brazilian government. The Brazilian Navy was indeed by then in a sorry state, while Chile aligned 36,896 long tons of warships, versus Argentina’s 34,425 long tons, Brazil was left behind with 27,661 long tons while her population and economy was far larger.

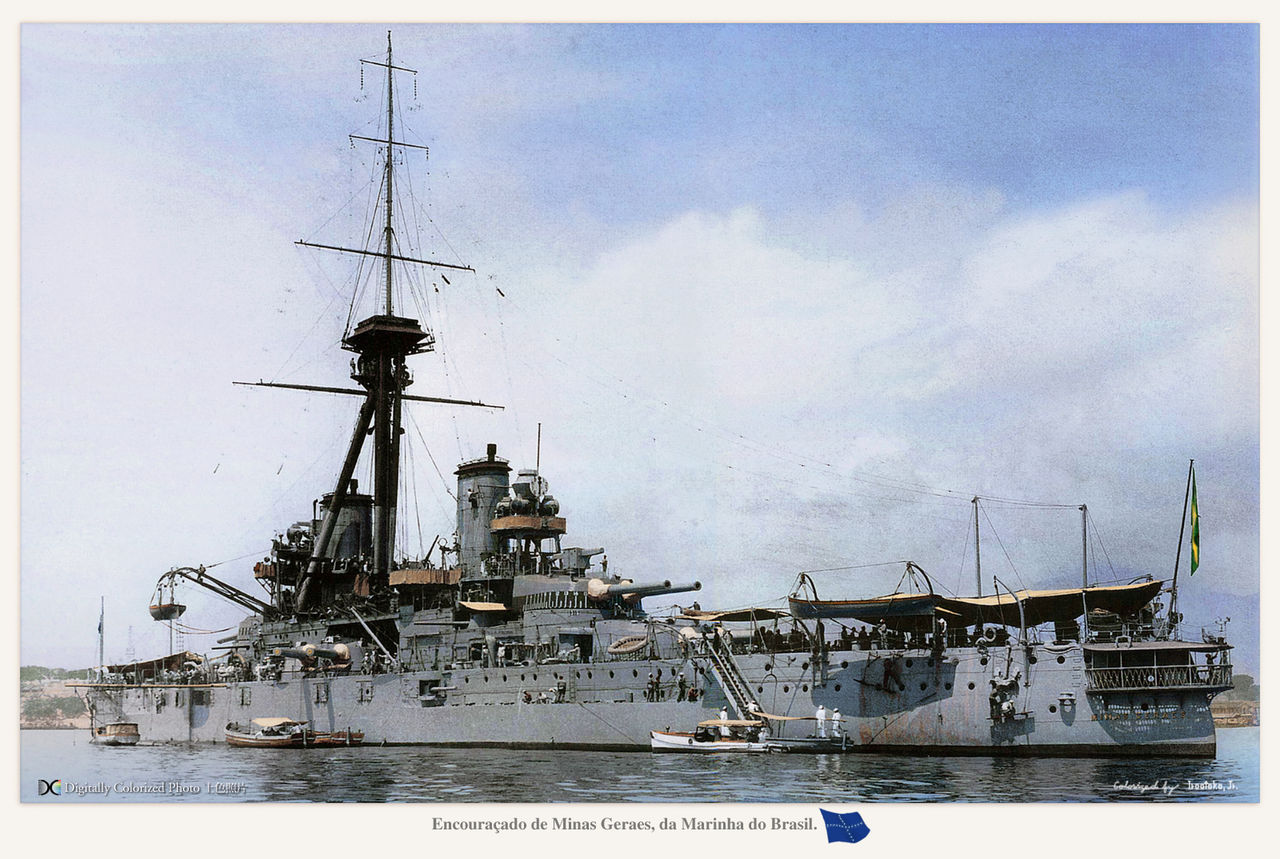

Soon, international demand for coffee and rubber exploded and provided Brazil with a newly found wealth. In the wake of Baron Rio Branco, which wanted more international recoignition for Brazil on the international scene, he obtained from the National Congress of Brazil to vote for a large naval acquisition program in late 1904. At first, three small battleships were ordered in 1906, but the order was changed after seeing the launch of the Dreadnought. In March 1907, they signed a new contract for three Minas Geraes-class battleships. This was rescinded into two ships because of the available yards, Armstrong Whitworth and Vickers, and the order for the third was postponed; This order caused an international sensation, the press even believing it was a disguised order for Germany. Of course this was noted by Argentina and Chile, which nullified their agreement to resume the arms race.

Minas Gerais, colorized by Irootoko fr.

Argentina took longer, but ended with a contract awarded to the Fore River Shipbuilding Company for the Rivadavia class, Chile’s being delayed by the 1906 Valparaíso earthquake (see almirante Latorre). Brazil and Argentina relations warming up, though, had them trying to persuade the Brazilians accept to cancel their third order. But this failed and Brazil ordered in effect a third dreadnought to Armstrong. The keel was laid down in March 1910, while the design was not yet completed.

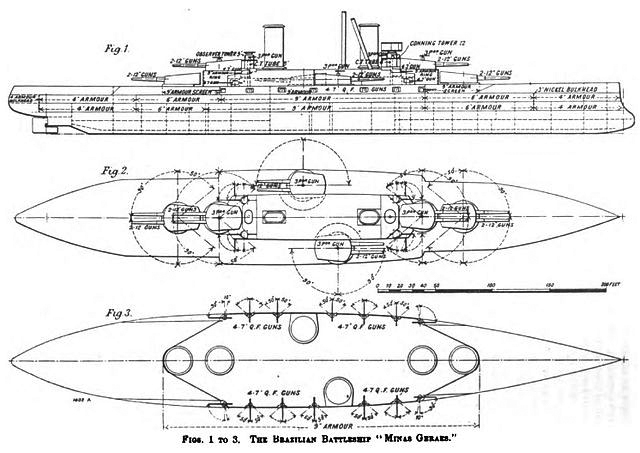

The Brazilian Navy indeed wanted something different for their main battery and ordered several drawings. The naval minister favoured more 12-inch guns on a modified Minas Geraes class, while Admiral Marques Leão favoured fast-firing guns of a slightly lower caliber, like the 10 inches planned for the initial pre-dreadnought order. Leão was advocated strongly his case with President Hermes da Fonseca and in November 1910, the Revolt of the Lash, payments on loans and a worsening economy marred the program’s budgetary support. In May 1911, Fonseca revised the Rio de Janeiro (rated for a 32,000 tons tonnage with 14 in. guns). The contract was to be revised with a tonnage reduction. This final contract was signed on 3 June 1911 and her keel laid on 14 September. The armament was changed due to the tonnage, down to fourteen 12-inch guns two more than the Minas Gerais class. But the turret management was now open do debate.

Design

Debate about the armament became the most interesting part of the design development. The core idea, proposed by the yard, was an all in-line configuration, which allowed a full broadside without the loss of a masked turret unlike the initial configuration of 1906-1910. The problem with that, is the use of no less than fourteen guns. A triple guns turret design was considered, but the ring would have imposed a much larger vessel and and 2×3, 4×2 configuration, with two triple amidship turrets to capitalize of the beam without compromising too much the hull structure and preserve top speed. However technically, no triple turret had been done yet, and there was a delay for its design that would have pushed back the launch for a year, but Brazil wanted it quick. Therefore, a radical approach of all-axial twin turret of a standard type in the Royal Navy was chosen, but it posed some problems.

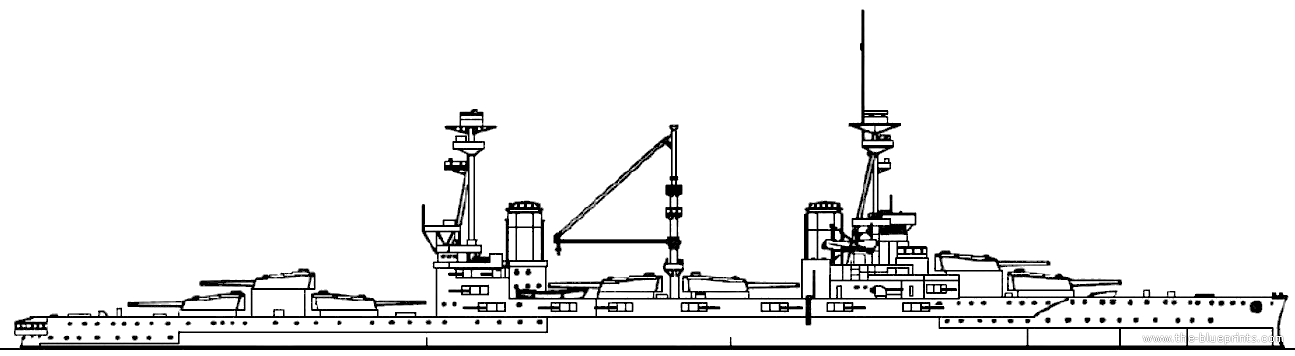

First of, to cram seven turrets in the axis while keeping the funnels, masts and superstructures imposed a rather long hull, and of course superfiring positions. In the end, the solution chosen was two turrets forward, with the upper one superfiring, two at deck level amidship, and three on the aft deck, including one superfiring aft and another back behind the upper turret, guns pointing forward, facing the aft superstructure while amidship turrets were pointing outwards in opposite direction, back to back and separated by a pillar. In the end, there were two superstructures “islands”, one at the front containing two barbette guns at deck level, the conning tower and the bridge, build around a tripod, with the funnel just behind. And there was the aft superstructure, also with an angular section to maximize the arc of fire, and comprising a funnel, and aft tripod but no conning tower.

The are covered by turrets was almost 50% of the ship’s length. This was quite unique and Agincourt remained the only battleship ever built with such configuration. It inspired another design, prepared in UK but built in Japan at the same time, the Fuso class, which had six axial turrets but with a heavier caliber, while the next Ise class in 1917 had their amidship pair superfiring, as for and aft pairs. One of the problems underlined by engineers was this many holes in the deck tended to weaken the whole hull structure, and it was the main reason behind the adoption of twin turrets.

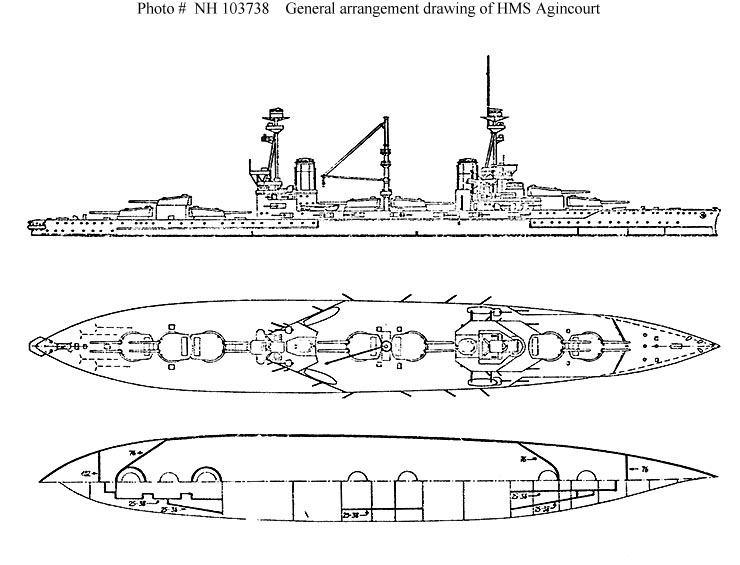

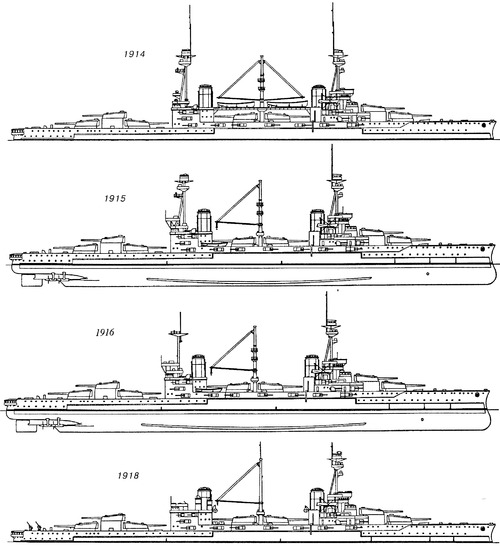

Agincourt as completed in 1914. Note the gangway above the amidship turrets, linking the two superstructure islands.

Hull

In the final blueprint, the future Rio was long overall of 671 feet 6 inches (204.7 m), for 89 feet (27 m) in beam and a draught 29 feet 10 inches (9.1 m) deeply loaded. She was to displace 27,850 long tons (28,297 t) as completed standard, for 30,860 long tons (31,355 t) deeply loaded. Her metacentric height was 4.9 feet (1.5 m) ensuring a relatively good stability. Due to her length/beam ratio she was not supremely agile with indeed a large turning circle, but still her large rudder and underwater lines ensured she was quick to turn without much sheer. In the end, she was considered as a good gun platform. After commission, first report came from her use. She was considered roomy and therefore less cramped with an excellent internal arrangement of living and working quarters. Due to the late change in attribution, a lot of devices indications installed and fittings, as well as instruction plates were all in Portuguese. These were changed later. By 1917, her crew swelled to 1,268 officers and men.

Propulsion

Her propulsion system was not revolutionary. She was fitted with Parsons direct-drive steam turbines, four of them, each driving a propeller shaft. She was given high-pressure turbines on outwards shafts and low-pressure ones astern on the inwards shafts, each fitted with three-bladed propellers, 9 feet 6 inches (2.9 m) in diameter. These turbines were fed by high pressure steam obtained from twenty-two Babcock & Wilcox water-tube boilers. They worked at an operating pressure of 235 psi (1,620 kPa; 17 kgf/cm2).

Performances:

Total output as indicated in the documentation was 34,000 shaft horsepower (25,000 kW). However in trials with overheating these figures rose to 40,000 shp (30,000 kW) and the top speed to 22 knots (41 km/h; 25 mph).

Autonomy:

The powerplant could be supplied with a normal, peacetime stock of 1,500 long tons (1,500 t) of coal. But her generous internal arrangements and with her underwater buoyancy chambers she could hold 3,200 long tons (3,300 t) of coal, plus 620 long tons (630 t) of fuel oil. The latter was sprayed on the coal to increase the burn rate. At ten knots she was able to cover 7,000 nautical miles (13,000 km; 8,100 mi). Electrical power came from four small RP engines mated to electrical generators.

Armament

Main Armament:

As we saw, her main artillery comprised seven twin turrets for a total of fourteen 12-inches guns. These were BL 12-inch Mk XIII 45-calibre models. The turrets were hydraulically powered. Since traditional turret naming was a bit odd there, the number seven pressed instead for the adoption of the days of the week. “Sunday” was therefore the foremost deck turret, formerly “A”. Depression/elevation −3°/13.5° respectively.

Ammunition: 850-pound (386 kg) AP shell, with a muzzle velocity of 2,725 ft/s (831 m/s).

Range: At 13.5°, 20,000 yards (18,000 m) with AP shells.

Wartime modification: The mount was modified for a maximum elevation of 16° extending the range to 20,435 yards (18,686 m).

Rate of fire 1.5 rounds per minute.

As described buy an officer on deck, the full broadside was impressive: “the resulting sheet of flame was big enough to create the impression that a battle cruiser had blown up; It was awe inspiring.” Agincourt was sturdy enough not to take any damage resulting of these full broadsides, although officers ion the mess saw all the tableware and glassware shatter.

HMS Agincourt in 1915 – the blueprints

Secondary Armament:

As designed, the battleship was served by slightly more secondary guns, eighteen BL 6-inch Mk XIII 50-calibre single casemate guns. Fourteen were in armoured casemates along the the upper deck, two in the fore and aft superstructures protected by gun shields and Tow more abreast the bridge in pivot mounts, protected by gun shields.

Depression/Elevation: −7°/13° (wartime modifications 15°)

Range: 13,475 yards (12,322 m)/15°

Ammunition: 100-pound (45 kg) shell, muzzle velocity of 2,770 ft/s (840 m/s).

Supply: 150 rounds per gun, 1,700 total.

Rate of fire: 5-7 rounds per minute.

In reality this was closer to three rounds a minute after ready ammunition were used. Access via the the ammunition hoists was too slow. This was a common problem which conducted crews to often store ammunition and charges in unsafe places or left flash-doors open. The result of this was tragically shown at Jutland.

Fire control:

Each turret was given its individual roof armoured rangefinder. A large one was mounted on top of the foretop. However, when it was built, no provision was made to include a Dreyer fire-control table, considered as a top secret and too sensitive equipment to end in a foreign navy; As a result, HMS Agincourt at Jutland was probably the only dreanought deprived of this system, resulting in a less accurate fire. She would later receive a fire-control director below the foretop. Also a turret was modified to control the entire main armament in 1917. About the same time, directors were installed either side to control for the 6-inch (152 mm) guns. Also an high-angle rangefinder was added in 1918 to the spotting top for the AA defense. A 9-foot (2.7 m) rangefinder was added to the former searchlight platform on the foremast in 1917.

HMS Agincourt in 1918 – the blueprints. Ultra HD profile.

Light artillery & torpedoes:

The ship also was fitted with ten 3-inch (76 mm) 45-calibre quick-firing guns. These very standard rapid fire ordnance from vickers was mounted on the superstructure, all in pivot mounts. They were protected by gun shields. In addition two high-angle 3-inch (76 mm) AA guns were placed on the quarterdeck in 1917–18.

HMS Agincourt like all battleships of that era, carried three 21-inch (533 mm) submerged torpedo tubes. Two in the beam, one in the stern. There was a water dispensal system: Each time the tube was open and fired, water seeped into the torpedo flat, facilitating reloading and was pumped overboard afterwards. But this also meant in case of rapid fire, the crew had to operated in 3 feet (0.9 m) of water. Ten torpedoes were stored. They were controlled by the aft conning tower.

Protection

The weight of the armament left a puzzle to engineers. The remained weight for her armour was reduced indeed. So compromises had been found, and they started to reduce thicknesses in various places, like a four-stage armored deck arrangement, thinner belts at the ends, etc. But overall, this was the weak part of the design.

-Waterline belt: 9 inches (229 mm) thick for 365 feet (111.3 m) from “Monday” to the “Friday” barbette. Down to 6-in for on 50 feet (15.2 m) and 4 in (102 mm) to the bow.

Aft, it was reduced to 6 in on 30 feet (9.1 m) and 4-in but stopped at the rear bulkhead.

-Upper belt: Up from the main to the upper deck, 6-in and from “Monday” to “Thursday” barbettes.

-Armour bulkheads: 3-in, Closing the bow, were angled inwards from midships armoured belts to the end barbettes

-Armored Decks: Layered defense with four of them, from 1 to 2.5 in (25 to 64 mm).

-Barbettes: 9 in thick, above the upper deck, 3 in below to no armour below the main armored deck except the last three aft.

-The turret armour: 12 in (305 mm, face), 8 in (203 mm, sides), 10 in (254 mm, rear), 3 in (76 mm, roof).

-Casemates (secondary guns): 6 in plus 6-in bulkheads.

-Main conning tower: 12 in (305 mm) sides, 4-in (102 mm) roof.

-Aft conning tower: 9 in sides, 3 in roof.

-CT communications tube: 6 in above upper deck, 2 in below.

-Magazines: 1 in or 1-1.5 in side armour plates along the torpedo bulkheads

Agincourt therefore had weaknesses, first a thinner underwater belt, weak barbettes, and poor ASW compartimentation. She was indeed not subdivided. The Brazilians staff indeed preferred to eliminate watertight bulkheads which could limit the size of the compartments available and interfere with the crew’s comfort. The officer’s wardroom for example was larger than in RN practice, being 85 by 60 feet (25.9 by 18.3 m) and it should have been also somptuously decorated.

These weakness conducted the Royal Navy to order the addition of 70 long tons (71 t) of high-tensile steel on the main deck after Jutland. The intent was to protect the magazines against plunging fire.

From Brazilian to Turkish to British

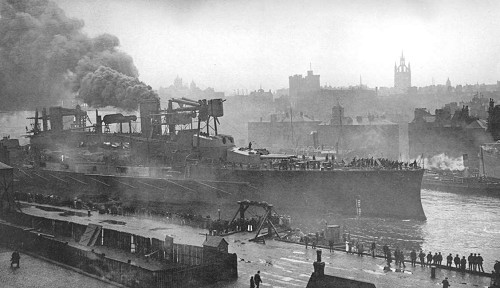

Sultan Osman I after launch, tugged to the site of her completion. src

From Rio to Sultan Osman I

Rio de Janeiro was laid down on 14 September 1911 at Armstrong, Newcastle upon Tyne. She was launched on 22 January 1913, but right after the keel-laying, the Brazilian government was confronted with an economic crisis: The catalyzer was the European depression following the Second Balkan War in August 1913. Soon after, Brazil was forced to renounce foreign loans while coffee and rubber exports plummeted notably due to the loss of rubber monopoly to competitors in the Far East. In addition the Brazilian admiralty obtained clues of new dreadnoughts projects or in construction that would have made the Rio obsolete. In the end, the government place the ship for sale in October 1913. She was sold to the Ottoman Navy at the time, for £2,750,000. The contract was signed on 28 December 1913 and Rio was renamed Sultân Osmân-ı Evvel, while almost complete. She started yards first trials in July 1914, and was completed in August 1914, as the First World War just started.

British requisitions

The British captain learned the new while the ship was at sea in sea trials. An Ottoman crew as en route to receive her officially, but in between, the British Government, not yet at war, took over the battleship. But meanwhile, the Turkish captain and his five hundred Turkish sailors arrived in a transport in the River Tyne. Negociations rook place, but the captain threatened to board his ship by force to hoist the Turkish flag. However at that time, First Lord of the Admiralty was Winston Churchill. In his usual style, he gave strict orders to resist such an attempt at gun point and bayonets if necessary. And as it was not enough, the Turkish crew also learnt that the British also requisitioned a King George V class vessel while still in construction at Vickers, the Reşadiye. The latter would become the HMS Erin. Negociations resumed, the British were quick to translate the contract’s particular clause that allowing such requisition in wartime. However as the Turks were also prompt to underline, UK was not yet at war, so this move from the government was illegal. Basically it was a fait accompli. On 3 August however, the British ambassador to the Ottoman Empire informed his Ottoman counterpart of the official requisition. Churchill indeed did not wanted to risk these battleship to be used against the British i the Mediterranean and knew what consequences could be. They indeed cause an outrage in Istanbul.

Consequences: The shift of alliances

This takeover would caused an uproar in the Ottoman Empire, as both the government and population were united in their strong resentment. Indeed, both battleships were partially funded by public subscriptions. Donations for the Ottoman Navy came in from everywhere and were rewarded with “Navy Donation Medals”. This seizure a few days later was compensated by the very opportune gift by the Kaiserliches Marine of the battlecruiser Goeben and Breslau, together with admiral Souchon and his crews, to the Ottomans. This had the strong effect to persuade the government to turn away from Britain and later, from 29 October, the triple entente with an old enemy, Russia, and take the side of Germany and what became the “Central Empires”. Russia’s move to the triple entente was triggered after Goeben attacked Russian facilities in the Black Sea.

Once the matter was settled after UK officially was at war, the Turkish crew returned home. The Royal Navy before commissioning the ship under her new name, immediately started to make modifications before commission: The flying bridge over the two centre turrets notably was eliminated and she the Turkish-style lavatories were replaced (…). Her name was an idea of Churchill’, formerly reserved for the sixth Queen Elizabeth battleship ordered under the 1914–15 Naval Estimates. But in service she was soon nicknamed the “Gin Palace” due to her unusually luxurious fittings as well as a name play (“A Gin Court”). “pink gin” was a popular drink among RN officers. It has nothing to do with the supposed shattering effect of a full broadside, alhough it shook indeed chandeliers and glassware in the officers’s mess and other places.

The Admiralty was unprepared however to man Agincourt in a short notice. Her crew was a mixbag assembled from Royal yachts and detention barracks. Not the best and brightest perhaps, but at least Agincourt had a crew. Her captain and executive officer served previously on the HMY Victoria and Albert and discovered their ship on 3 August 1914. No doubt with the luxury on board they found at home. The crew was even completed by minor criminals who had had their sentences remitted.

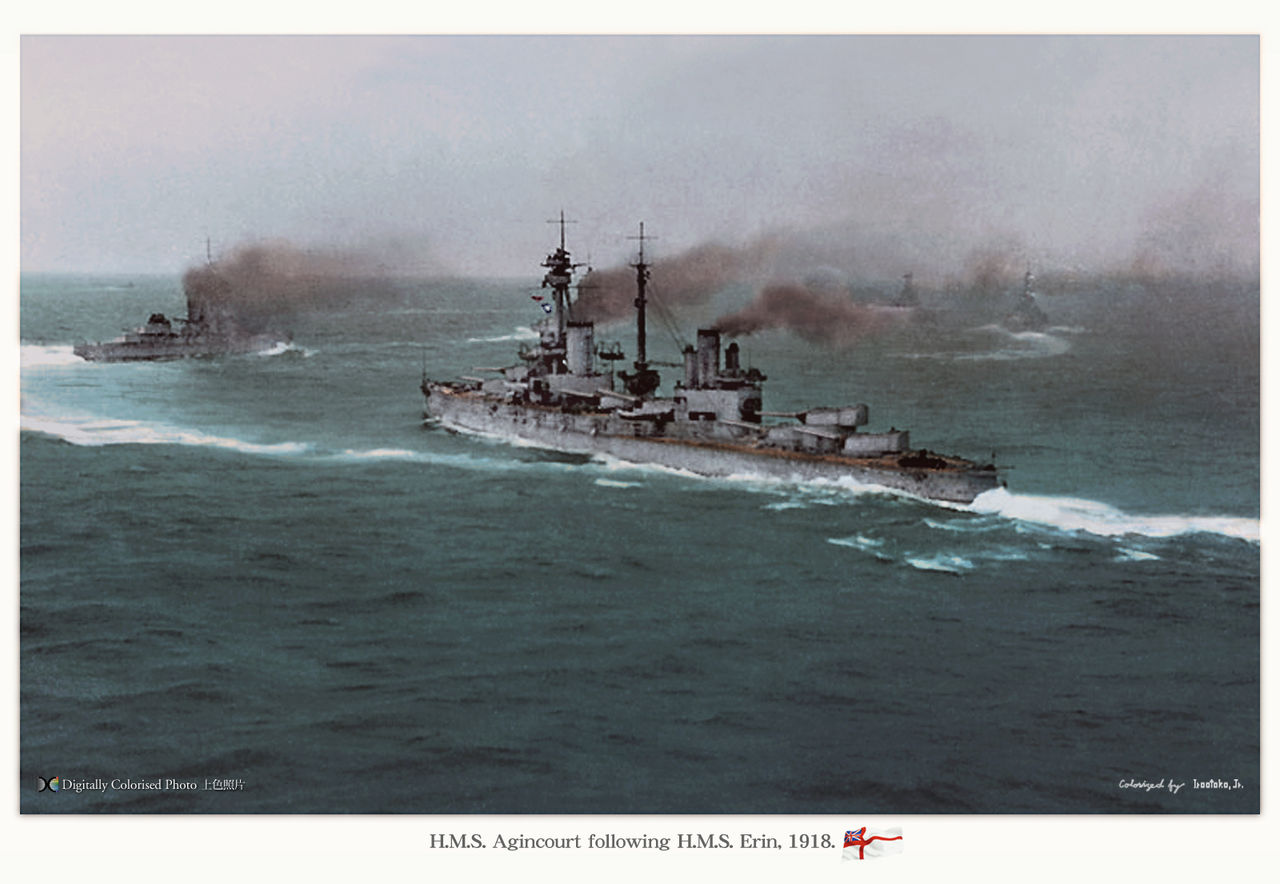

HMS Agincourt showing her broadside and HMS Erin in the background veering to starboard in 1918 – colorized by Irootoko Jr.

Career of the Agincourt

HMS Agincourt had her crew trained hard until 7 September 1914, ans she joined the 4th Battle Squadron of the Grand Fleet at Scapa Flow. However the base was still under plans of ASW defense and the fleet was at sea to avoid being torpedoed at anchor. Agincourt was forty days with the Grand Fleet, half at sea but there was almost a year and a half of inaction. In between sweeps in the north Sea were done both for exercise and to try to draw the Kaiserliches Marine from its bases.

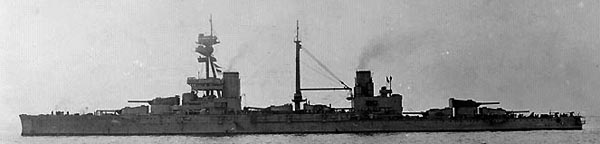

HMS Agincourt underway in 1915

HMS Agincourt

On 1 January 1915 however, Agincourt left the 4th BS for the 1st. Before the battle of Jutland on 31 May 1916 she was the last ship in line in the Sixth Division, 1st BS. Her sisters in this division were HMS Hercules, Revenge and HMS Marlborough, the flagship. It was an heterogeneous group, more difficult to control. The Sixth Division was also the most starboard column when the Grand Fleet advanced to meet Admiral Beatty’s Battle Cruiser Fleet. The fight started with the High Seas Fleet soon and Admiral Jellicoe kept the cruising formation until 18:15 and ordered the columns to deploy in a single line, aligned on the portmost division. Therefore each ship had to turn 90° in succession. The Sixth Division appeared then to be the closest to the battleships of the High Seas Fleet and they started firing even though they were making their turn to port. This became known the “Windy Corner”, drenched by German shell splashes. The German scored no hits however.

HMS Agincourt and Erin turning to port at Jutland, a famous photo.

At 18:24, Agincourt fired on a German battlecruiser and soon also with her six-inch guns on closing in German destroyers. They made torpedo attacks on the battleships to cover a south turn of the Hochseeflotte, and Agincourt managed to didge two torpedoes, whereas Marlborough was hit. Visibility had bee appealing all along, facilitaing the destroyers approach, but the weather cleared around 19:15. HMS Agincourt lookouts identified a Kaiser-class battleship, and she started furing but scored no apparent hit. The latter escaped in the smoke and haze and around 20:00, Marlborough, her bulkheads damaged, had to slow down. As she was the flagship, the rest of her division did the same. But with the reducing visibility at each minute, the division lost sight of the Grand Fleet. By night, it happen they passed the badly damaged SMS Seydlitz but failed to open fire. They were in sight of Scapa at dawn on 2 June. Agincourt made a post-batte report: She had expended 144 twelve-inch shells and 111 six-inch shells; but no hit was recorded. Soe authors attributed this to her lack of modern ballistic computer, unlike other dreadnoughts.

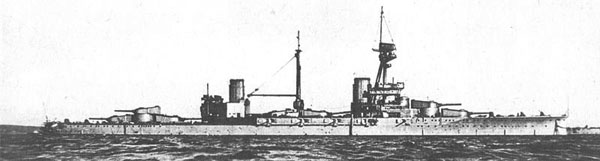

HMS Agincourt in 1918. Last one by Postales navales

The latter war and end of commission

The Grand Fleet made several sorties in 1917 and 1918, but Agincourt was not listed in all of them. On 23 April 1918, she stayed permanently in Scapa with HMS Hercules to provide distant cover for the Scandinavian convoys between Norway and Britain. It was feared a High Seas Fleet sortie, which was planned but never happened. Reports from German Intelligence were off schedule as well and Admiral Scheer aborted the whole operation. Another all out sortie was planned in October-November but never took place: Indeed by that time the crews were borderline to open mutiny.

HMS Agincourt by then had been transferred to the 2nd Battle Squadron. She was there at the surrender of the High Seas Fleet, on 21 November. Placed in reserve at Rosyth in March 1919, the British Government approached the Brazilians to try to sold her at a lower price, but without success. Having no use for this non-standard, unique battleship, she was listed for disposal in April 1921. Not exactly in reserve, but with a reduced crew, she was used for experimental purposes in late 1921. Plans were made to convert her as a mobile naval base. Plans showned the removal of five turrets, while their barbettes were converted into storage rooms and workshops. but this never materialized and she was sold for scrap on 19 December 1922, in part because of the Washington Naval Treaty. She was not scrapped until 1924.

Various appearances of the battleship until 1918.

Author’s profile of the Agincourt in 1914.

⚙ Agincourt specifications 1914 |

|

| Dimensions | 671 ft 6 in x 89 ft x 29 ft 10 in (204.7 x 27.1 x 8.2 m) |

| Displacement | 27,500 t standard; 30,250 T FL |

| Crew | 1,115 |

| Propulsion | 4 shaft Parsons turbines, 22 B & W boilers, 34,000 hp |

| Speed | 22 knots (41.5 km/h) |

| Range | 6,680 nautical miles (12,370 km) at 10 knots (19 km/h) |

| Armament | 7×2 12-in, 20×1 6-in, 12x 3-in (2 AA), 3x 457mm TTs (stern, beam) |

| Armor | Belt 9 in, Decks 1–2.5 in, Barbettes 2–9 in, Turrets 8–12 in, CT 12 in |

The models corner

Nice model of the Agincourt by Kostas Katseas src

-Deluxe Edition FlyHawk Model 1/700

-Combrig 1/700 – See more

Read More/Src

Specs Conway’s all the world fighting ships 1906-21

Burt, R. A. (1986). British Battleships of World War One. Annapolis

Friedman, Norman (2008). Naval Firepower: Battleship Guns and Gunnery in the Dreadnought Era. Annapolis

Gardiner, Robert; Gray, Randal, eds. (1985). Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships: 1906–1921. Annapolis

Gibbons, Tony (1983). The Complete Encyclopedia of Battleships: A Technical Directory of Capital Ships from 1860 to the Present Day.

Grant, Jonathan (2007). Rulers, Guns, and Money: The Global Arms Trade in the Age of Imperialism. Cambridge, Mass. Harvard University Press.

Harner, Robert (2006). “Question 18/02: British Naval Base at Addu Atoll”. Warship International. XLIII (2): 152.

Hough, Richard (1967). The Great Dreadnought: The Strange Story of H.M.S. Agincourt: The Mightiest Battleship of World War I. New York: Harper & Row.

Livermore, Seward (1944). “Battleship Diplomacy in South America: 1905–1925”. Journal of Modern History 16

Martin, Percy Allen (1967) [1925]. Latin America and the War. Gloucester, Massachusetts: Peter Smith.

Massie, Robert (2004). Castles of Steel: Britain, Germany and the Winning of the Great War. New York: Random House.

Murfin, David (2020). “Warship Notes: The Mobile Naval Base”. In Jordan, John (ed.). Warship 2020.

Newbolt, Henry. Naval Operations. History of the Great War: Based on Official Documents. V

Parkes, Oscar (1990). British Battleships (reprint of the 1957 ed.). Annapolis

Scheina, Robert (1987). Latin America: A Naval History, 1810–1987. Annapolis

Tarrant, V. E. (1999). Jutland: The German Perspective: A New View of the Great Battle, 31 May 1916. Brockhampton Press.

Topliss, David (1988). “The Brazilian Dreadnoughts, 1904–1914”. Warship International. XXV

The Agincourt on wikipedia

On the Dreadnought Project

On maritimequest.com

worldwar1.co.uk

jutlandcrewlists.org

navypedia.org

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign

The photo captioned “HMS Agincourt and Erin turning to port at Jutland..” shows Agincourt her in her 1918 rig (searchlight towers around the aft funnel and no mast aft).