Named the “Elisabethan Corsairs” due to their names, the Hawkins-class cruisers were designed for hunting down commerce raiders in the open ocean, combining heavy armament, high speed and long range, to the detriment of armour. They were arguably less well armoured than some earlier protected cruisers but the scheme was better designed. But these cruisers were also an historical milestone, not only for the RN, but also the world. They defined the concept of “heavy cruiser” by blending some aspects of past protected cruisers and modern scout cruisers along with a uniform heavy armament with intermediate QF calibers. Designed as “cruiser hunters” specifically against WWI German commerce raiders, they were later chosen as a standard for the new heavy cruiser type defined in the 1922 Washington treaty and confirmed by the London 1930 and 1936 conferences. As cruisers, they featured an interesting mix of characteristics and constituted a radical design leap for their time, but they were obsolescent in WW2 (all but Raleigh, lost early on and Vindictive converted as cruiser-carrier for a time), in which they took part actively. Authors tends to separate Hawkins, Raleigh, Frobisher and Effingham as their own class, from Cavendish/Vindictive due to her own peculiar design.

Note: First published on 2017/09/27

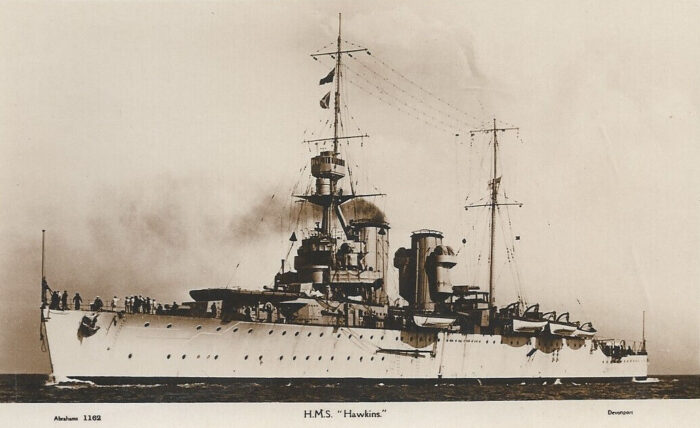

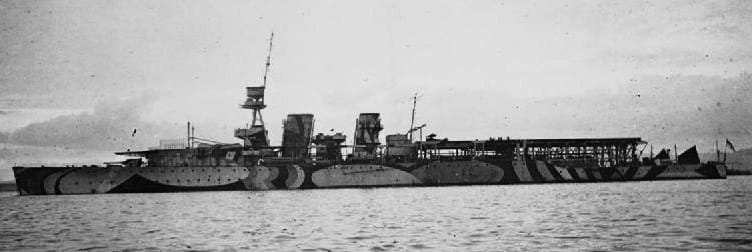

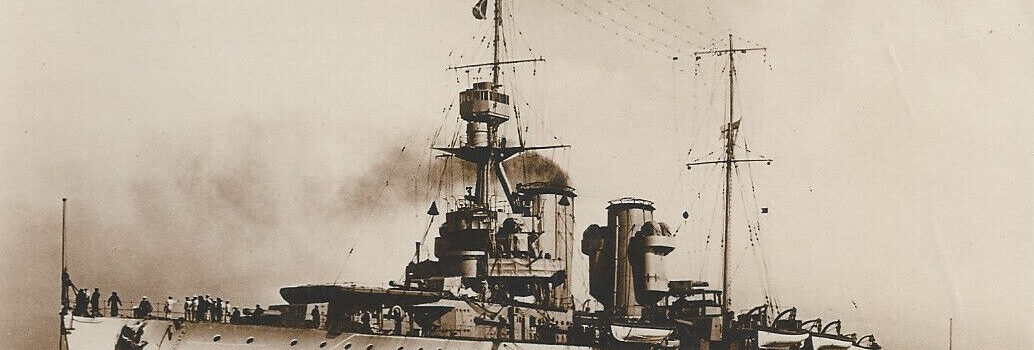

HMS Hawkins, postcard

Development

First and last heavy cruisers of ww1: In 1914, the Royal Navy aligned dozens of cruisers of the old 3rd, 2nd and 1st rate, protected and armoured, but after the launch of the Dreadnought in 1906, production focused on light cruisers, and this lineage would go through ww1 and beyond. Operations showed however the need for a more heavily armed cruiser type designed to counter German commerce raiders and be posted in far away overseas stations to deal with 170 mm-armed German cruisers (like Von Spee’s Scharnhorst class). Too late for ww1 (the five cruisers were completed 1917-18 for the first two, but operational in 1919), they inspired the model of heavy cruiser defined by the Washington treaty in 1922, had a quite active career in ww2, famously named after Elizabethan corsairs. They also inspired a new type of interwar cruiser known collectively as the “County” class.

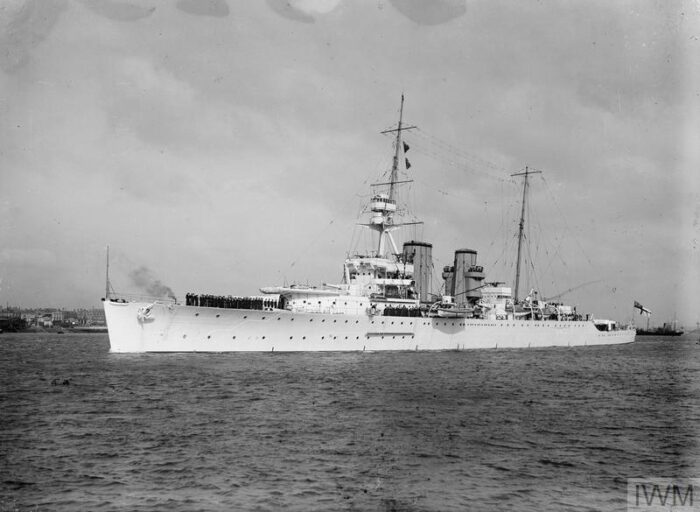

HMS Effingham in 1940.

Development

A design genesis going back to 1912

The Hawkins class had been dubbed by some “Improved Birminghams” and linked them to the 1912 Town-class light cruisers. But their design was based on a 1912 proposal by the Director of Naval Construction (DNC) of the time, Eustace Tennyson d’Eyncourt. The “German Scare” did not limited itself to dreadnoughts. There were also rumors of large German cruisers, armed with 6.9-inch (175 mm) guns. These were intended for overseas service, to hit hard British trade in case of war around distant stations. The problem was that in these same stations, the RN posted up to the start of WWI its elderly armoured cruisers to replace battleships. A good example would be HMS Good Hope, that tried to stop famously at Coronel Graf Spee’s Asiatic Squadron.

The Hawkins class had been dubbed by some “Improved Birminghams” and linked them to the 1912 Town-class light cruisers. But their design was based on a 1912 proposal by the Director of Naval Construction (DNC) of the time, Eustace Tennyson d’Eyncourt. The “German Scare” did not limited itself to dreadnoughts. There were also rumors of large German cruisers, armed with 6.9-inch (175 mm) guns. These were intended for overseas service, to hit hard British trade in case of war around distant stations. The problem was that in these same stations, the RN posted up to the start of WWI its elderly armoured cruisers to replace battleships. A good example would be HMS Good Hope, that tried to stop famously at Coronel Graf Spee’s Asiatic Squadron.

D’Eyncourt feared precisely the type of rampage made by KMS Emden and propose to replace these old armoured cruisers by fast (26 knots/48 km/h; 30 mph), modern, oil-fuelled, lightly protected but well armed (7.5-inch (191 mm) gun turrets) 7,500 long tons (7,600 t) cruisers. These were called “Light Cruiser for Atlantic Service” and were designed with a good seakeeping in order to track down these commerce raiders. They had limited superstructure but a good deep draught and high freeboard to achieve high speeds even in heavy weather.

Winston Churchill being the First Lord of the Admiralty at the time however objected their size and cost. Instead he insisted for a smaller but even faster (27.5 knots) design mixed 6-inch (152 mm) and larger 7.5-inch (190 mm) guns (likely 2x 7.5 and 4x 6-in), but mixed fired (coal and oil) as were the Birminghams in a letter of August 1913. There were indeed real concerns about the ability to be supplied with oil in case of war, whereas coal was always abundant in UK. D’Eyncourt answered by a new proposal of oil-fuelled cruiser at a £550,000 budget instead of the £700,000 of his initial design. The mixed-fuel cruiser was costier at £590,000. But in 1913, constraints in budget had this development stopped.

Winston Churchill being the First Lord of the Admiralty at the time however objected their size and cost. Instead he insisted for a smaller but even faster (27.5 knots) design mixed 6-inch (152 mm) and larger 7.5-inch (190 mm) guns (likely 2x 7.5 and 4x 6-in), but mixed fired (coal and oil) as were the Birminghams in a letter of August 1913. There were indeed real concerns about the ability to be supplied with oil in case of war, whereas coal was always abundant in UK. D’Eyncourt answered by a new proposal of oil-fuelled cruiser at a £550,000 budget instead of the £700,000 of his initial design. The mixed-fuel cruiser was costier at £590,000. But in 1913, constraints in budget had this development stopped.

The project returns in 1915

As the First World War progress, regional German naval fleets were found surrounded by the Entente. Souchon’s Mediterranean squadron found refuge in Constantinople, but the powerful Asiatic Squadron under Admiral Count Graf Spee was soon preyed upon by Opportunistic Japanese and the RN, being forced to depart Tsing Tao. This Asiatic Squadron, combining warships and armed merchant cruisers made a rampage in British seaborne trade, imposed re-routing ships or delayed sailings and long trip. But overall, the exact position of his fleet remained unknown. Soon also in the Atlantic, the Kaiserliched Marine unveiled new commerce raiders. The need to protect convoys and search for these raiders suddenly cause a panic as despite its massive cruiser fleet, the RN could simply not be everywhere and lacked cruisers.

The scare posed by these raiders in fact outpaced the available cruisers in the opinion, and on 12 October 1914 d’Eyncourt came back with his 1913 design, presenting a slightly updated “Atlantic Cruiser” proposal. The memo was sent to the Board of Admiralty and focused on the mixed-fuel design variant, with a greatly improved radius of action. The mixed natured allowed more flexibility on remote stations where oil might not be available. By defaul the RN had naval bases with always coal around the world, plus trade was still largely running of coal at the time, so depots were found nearly in all ports of the world.

By early 1915 Graf Spee’s Rampage had been dealt with, apart remaining cruisers remaining in Paganonia or Africa. Still, the Royal Navy believed that the Germans would continue their commerce-raiding operations and by 9 June 1915 at last, the board discussed specifications for such a “large light cruiser”. D’Eyncourt was requested to submit new designs, this time pushing the speed boundary to 30 knots (56 km/h; 35 mph) and powered at 1/5 with coal while having at least ten 6-inch guns. Six sketch were provided, mixing instead 6 and 7.5 inches, even 9.2-inch (234 mm) guns.

Displacement respectively rose to 9,000-long-ton (9,144 t) and 9,750-long-ton (9,906 t) for the latter. The board wanted an armament with a long range, out to the visible horizon and able to cripple a fleeing raider if caught, ideally hittng its powerplant with a single hit, then catching up and finishing her up with lighter guns and torpedoes. In this new light, the 6-inch gun was recoignized as too short-ranged, lacking power. The 9.2-inch was so massive by constrast only two could be mounted per ship and it was believed to be slow. The 7.5-inch gun, faster and with a 30° elevation mount was believed to be the best option. It was almost twice lighter than the 9.2 in and fired at the same range and almost twice faster. It was more compatible with the 9000t displacement required.

Final Take

The main attention and focus turned to artillery as everything revolved around it, with an original combination of 7.5 inches (190 mm) and 4-inches (102 mm) guns as designed. Efforts were made to boost their autonomy, for a final displacement of 9,000 tons. In their final drawing in 1915, they were also able to face any cruiser of the time thanks to no less than seven 7.5-inch (191 mm) Mark VI guns under masks, distributed along the axis, with two side ones Almost in the center, for a six guns broadside. This was still a far cry to the next evolution (eight 8-inches guns) but the path was there. They rendered obsolete armoured and protected cruisers overnight by using fuel oil instead of coal and were much, much faster. A new generation of cruisers, that would serve actively in the interwar, but still appeared as “ancestors” in 1939.

Much delayed Cruisers

Eventually, the design was approved after several refined designs back and forth in december 1915. They were planned FY1916, the problem was other competing constructions in the yards envisioned and delays accumulated. Eventually the very first of these cruisers, aptly named from Elisabethan corsairs, HMS Hawkins (from John Hawkins) was ordered from HM Dockyard in Chatham on 3 June 1916. Still, between labor and material shortages, construction proceeded slowly and they completely misses the war. In her case, Hawkins was launched on 1 October 1917 but only completed on 19 July 1919. Four other cruisers were ordered:

HMS Raleigh (after Sir Walter Raleigh) at William Beardmore & Company in Dalmuir on 4 October 1916 (delayed launch until 28 August 1919)

HMS Frobisher (after Martin Frobisher) at HM Dockyard, Devonport laid down on 2 August 1916 but only launched on 20 March 1920

HMS Effingham (after Charles Howard, Lord Effingham) also at HM Dockyard but Portsmouth on 2 April 1917 was not launched before 8 June 1921

HMS Cavendish (after Thomas Cavendish) at Harland & Wolff in Belfast on 29 May 1916, only one actually launched on 17 January 1918 and completed before the end of the war in October. She only had time to start training before V-Day.

The main reason of the apparently counter-intuitive delays and fast construction of Cavendish was a complete change in policy. By 1917, the new concerns of the admiralty was to find solutions against U-Boats, not against now ellusive commerce raiders. The whole program was put on ice, but Cavendish however was requisitioned to test a concept of “cruiser carrier” as aviation was also all the rage in 1917. She eventually was completed as such, under the name “Vindictive” instead, honoring a cruiser just lost in an heroic action at Zeebruge.

Design

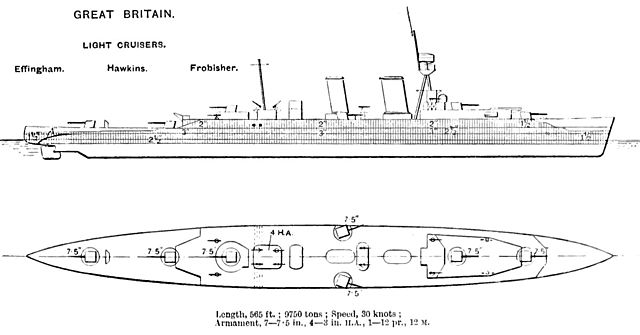

On Brassey’s naval annual 1923

Hull and General design of the Elisabethans

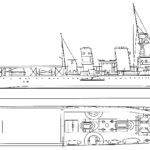

The Hawkins class were large cruiser indeed compared to everything else built at the time, the C-class and D class or the earlier Town class. In overall length they reached 605 feet (184.4 m), for a beam of 65 feet (19.8 m) and draught of 19 feet 3 inches (5.9 m) when deeply loaded, displacing 9,800–9,860 long tons (9,960–10,020 t) standard but 12,110–12,300 long tons (12,300–12,500 t) deep load, there’s no wonder the desin was chosen as a comparison standard to define the “heavy cruiser”. The extra tonnage (above 10K tons) was mostly the result of extra armour, later epurged from post-Washington designs.

The hull was based on the light battlecruiser Furious. For extra stability and ASW protection there were 5-foot (1.5 m) anti-torpedo bulges covering the engine and boiler rooms. The hull had 10° of tumblehome amidships for extra stability, and a lot of lare at the forward forecastle deck to improve seakeeping. The hull stepped down from a deck approx. 1/3 aft to a narrow rounded poop. Metacentric height was 4–4.1 ft (1.2–1.2 m) at deep load, which was good. Added to the blisters they were also well subdivided by internal bulkheads into order to resist the flooding of two adjacent compartments. The Hawkins class crew at the time comprised 37 officers and 672 ratings, and they had at least eight service boats under davits along their hull amidships. Later and especially in WW2, life rafts were preferred. They only kept two launches for shore liaison. The crew also grew in WW2 due to multiple additions, radars and AA (see below).

Powerplant and perfomrances

The Hakwins class were designed as the fastest British cruiser ever. Their powerful machinery on paper provided them with reached 31 knots, thanks to four geared steam turbines, fed by eight oil and coal fired boilers for a total of 60-70,000 shp (52,000 kW). HMS Hawkins had four sets Parsons geared steam turbines fed by 12 Yarrow boilers whereas Raleigh had four sets Brown-Curtis geared steam turbines and 12 Yarrow boilers and HMS Frobisher, Effingham differed by their Brow-Curtis boilers but ten Yarrow boilers. Hawkins’s two coal-fired boilers were removed in 1929.

The four Parsons geared steam turbine sets drove each a propeller shaft. Steam came from twelve mixed-fired Yarrow boilers working at a pressure of 235 psi (1,620 kPa; 17 kgf/cm2). For safety thet were placed in three separate boiler rooms with transverse and longitudinal bulkheads. The fore and aft groups housed only oil-fired boilers, but the middle compartment house four coal-fired boilers to help refualling them in foreign ports where oil was not available, in transit. Of coourse they would have needed all their power to intervene and intercept their preys, so it was theorized that when operating far from british bases, they would cruise on coal only of possible.

Coal also produced much less power, just 1/6h of the total output, so this was only good for patrol transits between stations. These boilers groups were ducted into two raked funnels amidship, relatively close togethers and with flat sides, the forward was larger than the aft ones and the uptakes from the coal-fired central group were trunked in with those from the oil-fired ones both fore and aft still. These turbines rated at 60,000 shaft horsepower (45,000 kW) for 30 knots on average bt this diverged:

Hawkins’ power plant was rated to 60,000 hp, Raleigh was the most powerful at 70,000 hp and Effingham, Frobisher had 65,000 hp. Speeds was reflected by these choices as Hawkins was capable of 30 knots, Raleigh of 31 knots and Effingham, Frobisher of 30.5 knots.

As for fuel supply this also varied. Hawkins and Raleigh carried 1,480 tons of oil and 860t of coal, Frobisher and Effingham eventually had 2,150t of oil.

Hawkins carried 1,580 long tons (1,610 t) of fuel oil, 800 long tons (810 t) of coal. Steaming range was for Hawkins 5,640 nautical miles (10,450 km; 6,490 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph), Raleigh was capable of 5400 nm at 14 knots, Effingham and Frobisher 7000 nm at 15 kts.

As the war ended, only Hawkins and Vindictive were completed with their intended mixed engine installation. In sea trials on 1919, Hawkins would only reach 28.7 knots (53.2 km/h; 33.0 mph) from 61,000 shp (45,000 kW) when deeply loaded, which was a disappointing as she was designed for 29 knots (54 km/h; 33 mph) fully loaded. Light, if pushed hard, she could have reached 31 knots or more, but after WWI the RN wanted trials to be done in realistic combat conditions.

In November 1917 already the Admiralty changed its mind on propulsion. It was decided to replace the coal-fired boilers on the least-advanced cruiser with four oil-fired boilers, with only Raleigh received this modification. Power thus rose to 70,000 shp (52,000 kW) and 31 knots (57 km/h; 36 mph) on paper. Raleigh reached her design speed in trials and Effingham, Frobisher als left their coal-fired boilers for a single pair of oil-fired boilers, a compromise to gain space, leaving them with 65,000 shp (48,000 kW) and 30.5 knots (56.5 km/h; 35.1 mph). The latter stowed only oil, 2,186 long tons (2,221 t) for a range of 5,640 nautical miles (10,450 km; 6,490 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) but this was altered later refits and reconstructions.

Protection

Protection was modelled on previous classes, albeit thicker, up to 3 inches or 76 mm for the belt and deck. Protection called for a full-length waterline armoured belt using the new high-tensile steel (HTS).

Main belt: up to 2.5 in (38–64 mm) forward, 3-in (76 mm) amidships, 2.25–1.5 in (57–38 mm) aft

Upper belt: 1.5 in (38 mm) forward, 2 in (51 mm) amidships.

Upper deck: 1 to 1.5 in (25–38 mm) over the boilers

Main deck: 1 to 1.5 in (25–38 mm) HTS over the engines, 1 in (25 mm) over the steering gear.

Gunshields, main guns: 2 in (51 mm) thick forward, 1 in (25 mm) top and sides.

Transverse bulkhead: 1-inch aft of mild steel

Magazines: Box protection, 0.5 to 1 inch (13 to 25 mm) HTS

Conning Tower: 3-in, HTS plates

This was light to protected cruisers standard, especially given their displacement, and certainly more tha for armoured cruisers, but compromises had to be found to keep the speed.

Armament

These ships were initially armed with seven 7.4-in/45 BL Mk VI main guns, four to six 3-in/50 12pdr 18cwt QF Mk I DP guns and 3-in/45 20cwt QF Mk I, or three 4-in/45 QF Mk V and in some case four 3-pdr/40 Hotchkiss Mk I, and two 2-pdr/39 QF Mk II, as well as six 21-in or 533 mm TT in the beam. This diverged between ships, reflecting design changed during completion, the last ending in 1924:

HMS Hawkins had the same main guns as her sisters, same 2-pdr AA guns and same TTs but divered by six 3-in (76mm)/50 12pdr 18cwt QF Mk I and four 3-in (76mm)/45 20cwt QF Mk I, as well as four 47mm/40 or 3pdr Hotchkiss Mk I. HMS Raleigh was completed with only four 3-in (76mm)/45 20cwt QF Mk I. Frobisher and Effingham had none of these small guns, only the 2-pdr AA.

Main: 7x 7.5-inch (191 mm) Mk VI

The main guns were seven 45-calibre 7.5-inch (191 mm) Mk VI guns, all in single mounts with light gun shields. They were arranged with five on the centreline, A and deck and B superfiring, X superfiring, Y further aft on the quarterdeck and Z on the poop deck, and C-D as wing guns abreast the aft funnel.

They had hand-worked mounts initially but they were later in the interwar, refitted with power-operated elevation and traverse motors, and thus much faster to train. In addition they were powered-loading gear was never fitted.

Kittens in HMS hawkins’ 7.5 inches fwd deck gun muzzle.

They were hand-loaded with a Welin breech block with as Asbury mechanism at up to 10° elevation and needed long lines of ammunition-handlers, the rounds were physically passed as well as cartridges along the deck, from the shell-hoist to each gun and even through another deck for the superfiring forward gun. This required a massive manpower described at the time “absurdly out of proportion” for their size and status. To give sufficient deck clearance for recoil at full elevation, the center-line guns were inside shallow wells. The side weapons were mounted on elevated platforms. A total of 44 guns were manufactured and they only were used by these cruisers.

Specs:

Weight and size: 14 tonnes (14,000 kg) without shield, 337.5 inches (8.6 m); (45 calibres) barrel.

Shells: 200-pound (91 kg) shells, muzzle velocity 2,770 ft/s (844 m/s)

Max range: 21,114 yards (19,307 m) or 12 miles.

150 rounds were allocated per gun. 30+ crew were necessary to operate each gun.

Later during the war, with the rearmament of some of these cruisers, 17 were then transferred to the coastal artillery, three at South Shields between July 1941 to August 1943, six to the Dutch West Indies (Curacáo and Aruba), three to Canada, five to Mozambique (lost in transit 1943), replaced by those from South Shields.

More on navweaps

Fire Control

HMS Vindictive, Raleigh and Hawkin had a mechanical Mark I Dreyer Fire-control Table using data from a 15-foot (4.6 m) coincidence rangefinder located under the spotting top at the head of the tripod mast. In addition they had a 12-foot (3.7 m) and a 9-foot (2.7 m) rangefinders and Effingham, Frobisher were fitted with a Mark III Dreyer Fire-control Table plus three 12-foot rangefinders.

3-in/50 12pdr 18cwt QF Mk I

Mainly used as defence against TBs, limited elevation. These six low-angle mounts were located in casemates between the forward 7.5-inch guns (two), two on platforms abreast the conning tower, two on a platform between funnels.

Specs:

Gun & breech: 2,016 lb (914 kg), bore 150-inch (3.81 m) 50 calibres

Shell: Separate QF 12.5 lb (5.66 kg) 3 in (76 mm) mv 2,600 ft/s (790 m/s)

Effective firing range 9,300 yards (8,500 m) at +20°

Rate of fire: 20 rd/min

3-in/45 20cwt QF Mk I

Main AA guns, positioned further aft around the base of the mainmast.

Specs: Mass 2,240 lb (1,020 kg) gun and breech, bore 11 ft 4 in (3.45 m), 11 ft 9 in (3.58 m) oa

Semi-automatic sliding-block breech with hydro spring, constant recoil 11 in.

Shell: Fixed QF HE 76.2 × 420 mm R 12.5 lb (5.7 kg) mv 2,500 ft/s (760 m/s)

Elevation −10 – 90°, traverse 360°, 16–18 rpm, crew 11.Effective firing range 16,000 ft (4,900 m)[8]

Maximum range 23,500 ft (7,200 m) (12.5 lb shell).

4-in/45 QF Mk V

These were placed on high-angle HA Mark III mountings. A pair were located at the base of the mainmast, third gun was on the quarterdeck.

Specs:

Barrel & breech: 4,890 lb (2,220 kg), bore 15 ft (4.6 m), 15 ft 8 in (4.8 m) oa

4-inch (101.6 mm), shell 31 lb (14.1 kg) fixed QF, Warhead 5 pounds (2.27 kg) Lyddite, Amatol HE

Breech: horizontal sliding-block, hydro-pneumatic recoil 15 in (380 mm)

Muzzle velocity: 2,350 ft/s (716 m/s), range 16,300 yd (15,000 m) ceiling 28,750 ft (8,800 m)

3pdr/40 Hotchkiss Mk I

The venerable 1880s Hotchkiss virtually present on all RN ships. Only installed on Hawkins and removed early in the interwar.

Torpedo Tubes

This was the most interesting aspects of the design. The admiralty wanted at least six torpedo tubes to deal with closer targets. The C and D class weree all heavily armed, with torpedo tubes banks. Overll they causes weight issues and dedgraded stability. Thus engineers found a different way to manage their placement aboard these ships: Of the six tubes, two were submerged in the beam, fixed, and the remainder pair above water, also fixed amidship port and starvboard at the level of the superfiring “X” gun aft, after the smaller mainmast. The fixed tubes obliged the ship to manoeuvr to the right angle, but they spared a lot of weight if made into torpedo tubes banks.

They fired the classic Whitehead models of the time such as the Mark II***** (1916).

Weight 2,953 lb (1,339 kg), Length 22 ft (6.7 m), 400 lb (180 kg) TNT warhead to 18,000 yd (16,000 m) at 19 kn (35 km/h) ot 15,000 yd (14,000 m) at 24 kn (44 km/h), 6,000 yd (5,500 m) at 35 kn (65 km/h), 4,500 yd (4,100 m) at 45 kn (83 km/h). The tubes were gradually removed, the last in 1943.

The interwar

Upgrades

There were significant differences between the ships at the end prior to ww2. However their uniform design included a radical armament of only heavy guns and light dual-purpose ones for some (with TB in mind as well as aircraft). In detail, these were all to be equipped with seven 7.5-inch (191 mm) Mark VI guns in single mounts CP Mk.V, whereas their secondary armament changed. Needless to say, the 12-pounder (76 mm) 12 cwt Mk.II guns in single mounts P Mk.I and QF 3-inch (76.2 mm) 20 cwt Mk.I guns on single mounts HA Mk.II of the Hawkins and others were later removed and replaced by more moder AA.

All the ships but Effingham (see later) were rearmed at completion indeed by three QF 4-inch (102 mm) Mk.V guns, in single mounts HA Mk.III or four QF 3-inch 20 cwt Mk.I guns on single mounts HA Mk.II for Hawkins or four QF 3-inch 20 cwt Mk.I guns on single mounts HA Mk.II and two QF 2-pounder (40 mm) Mk.II guns on single mounts HA Mk.I.

Here are the upgrade details:

in 1921 Hawkins had all six 3-in/50 removed, not replaved and in 1924 she also lost all her 3-in/45 for two 4-in2/45 QF Mk V.

In 1928 gained an extra 4-in/45 QF Mk V (so now 4) and gained a catapult and seaplane.

In November 1929, Hawkins had 4 boilers removed, the coal boilers were converted to fuel oil only with a fuel stowage ported to 2,740t oil, 55.000hp and 29.5kts top speed. She also gained two 4-in/45 QF Mk V. The powerplant changes were extensive: Four coal-fired boilers were removed, the remaining eight oil-fired boilers were modified to for improve burning, offsetting the loss of the four boilers but turbines fell to 55,000 shp (41,000 kW) and top speed to 29.5 knots (54.6 km/h; 33.9 mph), not a great loss. The now freed coal-fired boiler room was convered into a large oil tank enabling 2,600 long tons (2,642 t) of oil capacity and 20% more range overall. Her old 3-inch AA guns were replaced by 4-inch (102 mm) Mk V AA guns controlled by a modern Mk I HACS gunnery director, and she obtaned for her main guns a 15-inch rangefinder in the HACS director plus three 12-inch rangefinders. In 1932, Frobisher was converted to a training ship due to the London treaty reductions, seeing the removal of two main guns 7.5-in/45 aft (X, Y), and all her 21-in above water TTs for extra accomodations.

In 1936-1937, Hawkins, Effingham, Frobisher had all their main and above water TTs removed as well.

In June 1938, Effingham had a major refit in which she lost two boilers were the remainder being trunked into a single funnel, and fuel stowage raised to 2,620t, 58.000hp, 29.5kts. The armarment was changed as follows: She lost her four 3-pdr/40, and remaining two underwater 21-in TT for nine 6-in/45 BL Mk XII under masks, th addition of one 4-in/45 QF Mk V, three quad 0.5 in/62 AA vickers, and reinstallation of four above water 21-in tubes.

In early 1939, she was agains refitted, lost two 4-in/45 for the gain of four twin masked mounts 4-in/45 QF Mk XVI, two octiple 40mm/39 2pdr QF Mk VIII pompom AA, one catapult and seaplane and a full displacement rising to 12,514 tonnes.

In January 1940 Hawkins was also modernized, she lost her old Hotchkiss gins, kept her main guns and her above water tubes, but obtained two single 40mm/39 2pdr QF Mk VIII AA. By December 1941 in another frfit she gained a type 271 and a type 285 radar.

In March 1942 Frobisher lost her Hotchkiss 3-pdr and 40mm/39 pompom, kept five main guns, one of her 4-in/45 QF Mk V and gained four quad 40mm/39 2pdr QF Mk VIII pompom and well as seven 20mm/70 Oerlikon Mk II/IV as well as her four above water 21-in TTs and received the type 271, type 281, and type 285 radars

From December 1941 to May 1942 in refit, Hawkins lost two 40mm/39 but gained two quad 40mm/39 2pdr QF Mk VIII pompom AA, and seven 20mm/70 Oerlikon Mk II/IV AA guns in single positions. She also received a Type 281 early-warning radar, Type 273 surface-search radar and two Type 285 anti-aircraft gunnery radarsfitted on the roofs of the 4-in directors.

In 1943 Frobisher received a type 282 radar and by December 1943, Hawkins and Frobisher lost their remaining 21-in TTs to make room for extra AA and radars.

In May 1944, Frobisher received twelve single 20mm/70 Oerlikon Mk II/IV and the type 650 ECM suite whereas in August, Hawkins lost her quad 40mm/39 pompom and two single 40mm/39 for instead two octuple 40mm/39 2pdr QF Mk VIII pompom and three single 20mm/70 Oerlikon Mk II/IV and a full displacement rising to 13,160t.

In October 1944, Frobisher kept only two main guns, and four 4-in/45, as well as six 20mm/70. After the end of the war, Hawkins ended with all her main guns, four 102/45 HA Mk III, two octuple pompom Mk VIA, ten 20mm/70 Mk III, two 21-in tubes in the beam and the type 271, type 285 radars whereas Frobisher ended with only three main guns, a single 4-in/45 HA Mk III, four quad pompom Mk VII, thirteen 20mm/70 Mk III, two beam tubes, a catapult and spotter seaplane but she had a greated radar suite of all, with the type 271, type 281, type 282, type 285 radars, and type 650 ECM suite.

General Evaluation & Career

HMS Raleigh was lost on an unclassified reef of the Labrador coast in 1922, and Vindictive was transformed into an hybrid aircraft carrier, then converted as a fast supply ship in 1935. The other five ships were modernized in 1936-38, but it was planned to disarm them as per treaties. This was suspended when international tension grew. Their underwater TTs were removed, their old 3-in AA guns were replaced by 4-in quick-firing DP guns and to ten 40 mm pompom in quadruple and octuple mounts plus a number of single 20-mm Oerlikon guns. They never received the US pattern 40 mm Bofors. They also remained a bit under-armed for their size.

They received even more AA guns during the war, plus were equipped with a type 273 centimeter radar, a 286 type aerial surveillance radar antenna, and a 275 electronic fire control systems. The Frobisher additionally received two types 282 For its Bofors mounts. The latter was also freed from her wing guns in favor of additional 4-in guns in twin turrets. Their mixed boilers were converted to oil only and some boilers were replaced by more modern models. Most of these ships has been used for escorting convoys. Effingham was rebuilt in 1937 with a modernized powerplant, funnels truncated into a single one, artillery replaced by only 6-inquick firing masked guns, three superfiring. She remained the only one in this configuration, the other one being the Vindictive.

HMS Hawkins in the interwar

Hawkins served in The southern Atlantic, based in the Falklands, to intercept potential German corsairs trying to pass Cape Horn. She was then sent to the Indian Ocean, where she carried out a raid on Mogadishu against Italian shipping, capturing a cargo ship. After an overhaul lasting until 1942, she was sent to the Far East to assist Frobisher against the Japanese. Then she returned in time to participate in D-Day operations at Utah Beach. Afterwards she was broken up after the war in 1949.

Effingham was lost early in the war, in 1940, on a reef in Norway. But before that she had transported two million pounds of gold from the Bank of England to Nova Scotia, chased German raiders into the Atlantic, and then participated in the Norwegian campaign. Torpedoed by the U38, she survived, was repaired in record time and returned to operations, fighting in particular in Narvik. It was there that she met her destiny. For the anecdote, the map operator drawn a course so thick that it masked a reef off Navik’s passes. She struck this reef in right when racing in the middle of the night, opening an immense breach in her flanks which caused a rapid sinking. Fortunately, most of her crew escaped and swam back to shore. She was then achieved by friendly gunfire to prevent capture and reduced to the state of smoking wreck four days later.

During her peacetime career, Frobisher served in India, the Atlantic and China. She had been disarmed in 1930, and served as a schoolship but was eventually modernized and rearmed between 1940 and 1942. She was sent rapidly to the Far East where the situation deteriorated and fought against the Japanese until his return in late 1943. She served as an escort in the Atlantic and provided fire support in Normandy in June 1944, covering Sword beach. She was torpedoed by night by an unidentified S-Boote in August 1944, repaired and finally partially disarmed to serve as a school ship again, a role she held until set aside, unlisted, sold and broken up in 1949.

Frobisher in June 1944 off Normandy (author’s illustration).

Hawkins specifications |

|

| Displacement | 9,750 tons Standard, 12,190 tons FL |

| Dimensions | 184oa x18 x5.26 m (605 x58 x17 ft) |

| Propulsion | 4 shafts, 4x Parsons geared steam turbines, 10 Yarrow boilers, 70,000 hp |

| Speed | 31 knots (57 km/h) |

| Range | 5400 nm @14 knots (10,000 km) | Armor | Belt 38-64 mm (1.5-2.5 in), decks & bulkheads 38-51 mm (2 in). |

| Armament | 7x 7.5 in, 3x 4-in DP, 8x 3-in DP, 2x 2pdr pompom AA, 6x 21-in TTs |

| Crew | 712 or 750 as flagship |

The case of Vindictive

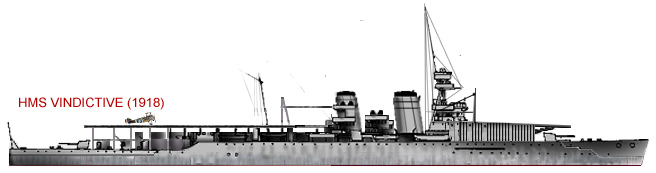

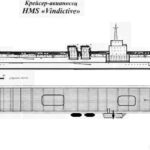

HMS Vindictive as completed, still not camouflaged in 1918, author’s illustration

HMS Cavendish was to be initially completed as a regular Hawkins class, but the admiralty decided in 1917 to have her completed as an experimental “cruiser-carrier” instead, of the “split deck design”. Unlike the “through deck” such as the Argus, and like Furious, she would comprise an aft landing deck and a forward launch deck, short and keeping part of her main armament. She was to be the first “hybrid cruiser” in the RN. It was clear however that she was spaller than Furious, so presenting also smaller landing and taking off surfaces, but this was considered worth testing. Her conversion was due to the lack of facilities to built such ship. In a sense, Hermes, laid down later, was to be the first true “through deck design” carrier cruiser.

General Design

By June 1917 work commenced, and “B” main gun, two 3-inch guns and the conning tower were all removed. Theh forward superstructure was rebuilt in order to support now a 78 by 49 feet (23.8 x 14.9 m) hangar with a capacity for just six reconnaissance aircraft. It had a small extension and supported a 106-foot (32.3 m) flying-off deck. It was considered enough to launch aircraft at full throttle, wheels blocked. They were hoisted up through a hatch at the aft end and lifted by two derricks. Now aft there was a recovery are, a 193 by 57 feet (58.8 by 17.4 m) landing deck, which imposed to remove the aft superfiring pair of main guns, relocated the four 3-inch AA guns on elevated platform between funnels.

There was (On Furious there two such gangways) a port side gangway which was 8 feet (2.4 m) wide and which connected the landing and flying-off decks and allow the transit of aircraft, wings folded, from the landing to the storage or launch area forward. The landing deck also had an important feature, a crash barrier hung from “the gallows”, at the forward end of the landing deck. Stability required to enlarge the upper portion of her anti-torpedo bulge. She completed her sea trials on 21 September 1918, proving she was capable of 29.12 knots (53.93 km/h; 33.51 mph) thanks to her original powerplant rated for 63,600 shp (47,400 kW).

Armament

To make room for her flight decks, HMS Vindictive was completed with just four guns, one forward, two in the wing positions, and one right aft. Further revisions to the number and layout of the main guns added to a complicated history as she was reconverted back as a cruiser in the interwar.

Air Group

During trials and exercises she operated Port Victoria Grain Griffin reconnaissance aircraft. These were a development of the unsuccessful Sopwith B.1 bomber, and a two-seat single-engined biplane only procured on small numbers to the RNAS notably to operate on Vindictive and deployed on the British intervention in the Russian Civil War.

During trials and exercises she operated Port Victoria Grain Griffin reconnaissance aircraft. These were a development of the unsuccessful Sopwith B.1 bomber, and a two-seat single-engined biplane only procured on small numbers to the RNAS notably to operate on Vindictive and deployed on the British intervention in the Russian Civil War.

Two were lost in accidents. There was only one landing aboard, performed by William Wakefield on 1 November and it was on last operational Sopwith Pup. Experiments on Furious demonstrated the turbulence created by the superstructures made a successful landings very dangerous and nigh impossible. Wakefield knew this by Furious pilots and managed to approach the landing deck at an angle while the cruiser placed itself in a wind and slowly moved. It was a one-off feat but was deemed to be too dangerous to be repeated.

When she was sent to the Baltic she had a dozen aircraft on board, Griffins, Sopwith 2F.1 Ship Camel fighters, Sopwith 1½ Strutter and Short Type 184 floatplane bombers which did not required deck space. After she was gruonded her air group ended in Finland on 14 July, on the first national airfield. Vindictive had her flying-off deck extended to 118 feet (36 m) to allow the bombers to take off with 112-pound (51 kg) bombs. Kronstadt Raids brough mixed results.

This only operational use of her concept proved this was not the righ solution. She was paid off into reserve at her return and the Admiralty considered her conversion as a “through deck” cruiser with an island like Hermes, launched on July 1918 but decided to wait tests on HMS Argus evaluating island designs. Vindictive later was considered too small to be effective and postwar financial restrictions went against such major reconstruction. So she was instead reconverted as a cruiser.

Long story short, in her new career, she was at the China Station, demilitarized in 1936-37 following the London treaty, converted as a TS. In 1939 she was to be modernized like Effingham but ended as a fleet repair ship instead, completed in March 1940. She was at Narvik, and operated in the Mediterranean, saw D-Day and was paid off at the end of the war. Converted again as fleet repair ship in 1940, she was damaged by an airborne “Dackel” torpedo off Normandy. Repaired she served as a destroyer depot ship (reserve 1945, BU 1946).

HMS Effingham

HMS Effingham

Effingham was completed last in 1925, with Captain Cecil Reyne in command. She was assigned to the 4th Light Cruiser Squadron, East Indies Station and under Captain Bruce Fraser (later First Sea Lord) from September 1929. She sent emissaries and her Royal Marine band to assist to the coronation of the Emperor of Ethiopia, Haile Selassie, on 2 November 1930. On 14 June 1932 she became flagship of Rear-Admiral Martin Dunbar-Nasmith (CiC East Indies Station) until 1 October before joining the 4th LCS. She had a cruiser in the Bay of Bengal in March–April 1933 and went back home, flagship of the Reserve Fleet, William Munro Kerr hoisted, then Vice-Admiral Edward Astley-Rushton and from 28 June 1935, Vice-Admiral Gerald Charles Dickens. She took part in the Silver Jubilee Fleet Review for King George V on 16 July, private ship on 29 September 1936 for modernization.

HMS Effingham as rebuilt in 1938

She was recommissioned on 15 June 1938 under Captain Bernard Warburton-Lee and flagship of Vice-Admiral Max Horton, CiC Reserve Fleet. Two future famous commanders in WW2. Captain John Howson took command on 17 April 1939 and on 9 August she hosted King George VI during the review of the Reserve Fleet in Weymouth Bay. She was sent to Scapa Flow on 25 August, 12th Cruiser Squadron and Horton’s flagship for the Northern Patrol, trying to intercept German ships back to Germany before the war broke out.

From 3 September, the Northern Patrol started to hunt down German commerce raiders trying to reach the Atlantic. Effingham however was grounded on 6 September repaired at HM Dockyard, Devonport on 3-9 October, later relieving Berwick, escorting Convoy KJ-3 and needed later engine repairs, boiler cleaning until early November. She carried £2 million gold to Halifax and returned while in Canada to the West Indies Patrol and south to Bermuda with HMAS Perth on the route Kingston-Halifax. However she soon was plagued by more engine problems in repairs in Bermuda. Her replacement boiler tubes were defective and she was scheduled to return home via Halifax, escorting Convoy HX-14 from 29 December.

She was repaired at Portsmouth from 9 January 1940, engines stripped down, boiler tubes replaced entirely and AA and directors modified. She also had a catapult installed. She returned into action from 12 April via Scapa Flow, and Plan R 4, the occupation of Narvik and the iron mines in Kiruna and Malmberget in Sweden if the Germans invaded Norway, which happened earlier than expected on 8 April, cancelling all plans.

Norwegian Campaign:

Effingham in a Norwegian fjord (cropped), April–May 1940, click to see the full photo

With HMS York, Calcutta and destroyers, she started seaching on 17 April for five spotted German destroyers off Stavanger by aviation, but it proved false, as they remained off the entrance to the Romsdalsfjord dueing the British landings at Molde and Åndalsnes. U-38 tried torpedo the cruisers underway on 19 April but they arrived safely back at Scapa Flow. On the 20th, Admiral Lord Cork (CiC Norway) chose her as flagship, and she took part on a shalling of Narvik in a snowstorm. On 1-3 May she shelled Ankenes and Bjerkvik and became command ship for the landings at Bjerkvik (12–13 May) with Lord Cork and the French commander Brigadier General Antoine Béthouart and Lieutenant-General Claude Auchinleck on board as observer. Effingham ferried herself 750 men of the French 13th Demi-Brigade, Foreign Legion and supported them with naval gunfire.

Auchinleck decided to transfer the South Wales Borderers from Ankenes to Harstad and create a HQ for the 24th Guards Brigade at Bodø and given the Lufftwaffe activity, Effingham was chosen to transport the troops to the displeasure of commander Howson as he only had 40 short tons (36 t) of supplies and ammunition and could not feed the 1,020 British and French troops on board. Eventually he obtained 130 short tons (120 t) of food and ammunitions plus ten Bren Carriers on deck, which marred the use of some of her guns.

As flagship of the 20th Cruiser Squadron, she also commandeered the nearby AA cruisers Coventry and Cairo, DDs Echo and Matabele when leaving Harstad on 17 May and took by night the Tjeldsundet Strait and Vestfjorden with a much higher average speed before arriving at 20:00 to unload in darkness. However near Bodø, U-Boat attack risk was high. Instead they went for the narrow strait between the island of Bliksvær and Terra Archipelago thanks to a just provided detailed, large-scale map of the area. RADM John Vivian in HMS Coventry lacked a copy of the map adn accepted Effingham be used as guide for the squadron, screened by Matabele at 23 knots, Echo trailing starboard. However in the strait entrance at 19:47, Matabele grounded on a submerged rock, Faxsen Shoal, tearing off her port propeller for its bracket and a minute later Effingham struck the shoal holing the hull, Coventry grounded later by the stern while turning to starboard to avoid Effingham.

The hull damage was considerable, as the dpeed draught of the cruiser meant the shoal tore apart sections of her hull and holed it at several places, so she started to flood. She also lost power and started drifting until settling on an even keel.

Howson ordered HMS Echo to tow Effingham to shallow water and hoped to have her beached at 20:15. But she destroyer failed to free her out and Vivian ordered it to be cast off at 20:45. Now the ship was declared lost, and it was ordered to abandon her and have her scuttled in deep water not to be salvaged later by the Germans. Echo took aboard all passengers 200 of the crew and at 22:10 had transferred the to Coventry, returned to Effingham to take off the remaider. Effingham ended grounded off Skjoldsh Island (east of Bliksvær), upright, settling under (9.1 m) of water. Boats from Matabele rescued extra crew, transferred to Cairo and then they all departed for Harstad.

HMS Echo stayed behind, Howson went aboard to supervise the salvage attempt by small ships from Bodø but it was painful. Only four Bren Carriers and some mortars were recovered. Only little material could salvaged, sent to Bodø. Detonators of the torpedo warheads and other explosives were underwater, the guns were sabotaged, ready-use ammunition thrown overboard. Eventually, Echo torpedoes her twice at 08:00 and she capsized. Postwar she was scrapped by Høvding Skipsopphugging but divers still can find some remains underwater.

HMS Frobisher

HMS Frobisher

Named after the corsair and future Elizabethan Admiral Sir Martin Frobisher (which defeated the Spanish Armada in 1587) HMS Frobisher was ordered in December 1915, completed among the latest on 20 September 1924. She was assigned to the 1st Cruiser Squadron, Mediterranean Fleet adn covered a party of Royal Marines in an amphibious landing exercise by June 1926. Rear-Admiral William Boyle made her his flagship by September and she was sent to the China Station. On 10 September 1928 Rear-Admiral Henry Parker replaced Boyle, and she took part in a torpedo exercise on 24 August and a fleet exercise in January, the combined exercise with the Atlantic Fleet in March 1929. In 1927–1928 she obtained a F.I.H aircraft catapult and crane on the quarterdeck, loosing the pair of 4-in AA gun, relocated to a platform between funnels.

In 1929–1930 she was with the Atlantic Fleet and on June 1930 she lost her aft superfiring gun to have a floatplane and superstructure installed close to the mainmast. She entered the reserve as flagship, Vice-Admiral and in 1932 was converted to a cadet training ship. She lost her quarterdeck main gun and two 4-inAA guns and from July 1935 obtained instead a new aircraft catapult bu with the 1936 London treaty she was completely disarmed, including her torpedo tubes and kept only a defensive/instructional 4.7-inch (120 mm). She was in reserve in 1937 at Devonport, transferred to Portsmouth by 1939 still as a cadet training ship.[12]

Wartime service. By September 1939 the RN decided to rearme her and Hawkins along the lines of Effingham but the conversion was delayed until 5 January 1940.

It was planned to give her back all seven main guns, above-water TTs, but install five 4-in AA guns, plus two quadruple and two single 2-pounder pompom, three 20 mm (0.8 in) Oerlikon AA guns, catapult, crane and superstructure around the mainmast removed. In 1941 however it was decided to fire another pair of quadruple 2-pounder pompom replacing the two wing 7.5-in guns while the single 2-pdr were to be replaced by four additional Oerlikons. Then shortly before completion,n always under low priority by March 1942, Frobisher was given a Type 281 early-warning radar, Type 273 surface-search radar and two Type 285 anti-aircraft gunnery radars on new 4-in directors plus depth-charge rails at the stern and hydrophones at the bow.

Frobisher in the Indian Ocean 16 June 1942

Frobisher was assigned to the 4th Cruiser Squadron, Eastern Fleet when completed for convoy escort, as well as of capital ships in the Indian Ocean. She towed the French light cruiser (previously destroyer) Le Triomphant in December 1943 after being badly damaged by a typhoon to Diego Suarez in Madagascar on 19 December, now in allied hands since Operation Ironclad. After more missions she was back home in March 1944 for Operation Neptune, the naval phase of D-Day. She received 12x Oerlikons AA guns, and her quadruple pompom were replaced by octuple in her refit from 5 April to May 1944.

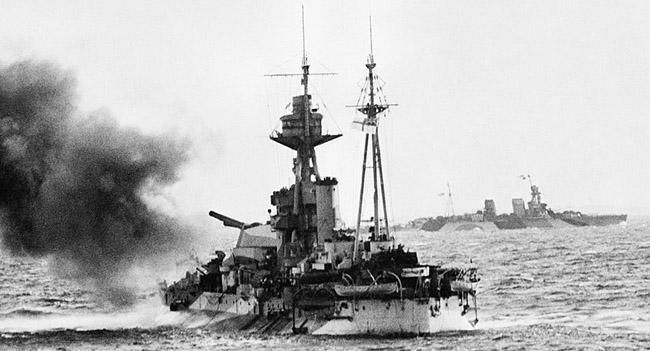

Frobisher is in the background; the monitor Roberts is firing in the foreground, 6 June 1944

On 6 June, HMS Frobisher took part in the Support Force D at Sword Beach during the landings. She shelled notably the defencses at Riva-Bella in Ouistreham and destroyed the fire-control observation post with a direct hit, helping the French Commando Kiefer to take the heavy defended casino. It was reportred at the time, the well drilled gunners managed to fire 5 rounds per minute. In August with HMS Albatross she was damaged by long-range G7e Dackel torpedoes from E-boats comng in the Baie de la Seine off Normandy.

HMS Frobisher in the Firth of Forth, 1945

HMS Frobisher in the Firth of Forth, 1945

This sent Frobisher under repair at HM Dockyard in Chatham and it was decided to convert her as a training ship for 150 cadets, which was started in Scotland (Rosyth) when transferred there in September. She lost her two superfiring and aft quarterdeck main guns, four amidships 4-in AA guns, octuple 2-pdr pompom mounts, some Oerlikons and depth-charge racks, directors for the 2-pdrs. Instead she had a 6-inch (150 mm) gun added in the forward superfiring B pisition, and a quadruple 21-in torpedo bank on her aft quarterdeck former main gun position for instruction. She had the new Type 291 early-warning radar but this conversion was low priority and dragged on until May 1945. By then she had still three main guns, a single 6-inch gun, a single 4-inch AA, 11 Oerlikons and a quad TT bank to represent most armament types. She served as such and in July 1946, her 4-in HA (high-angle) directors were removed. She was replaced in her role by HMS Devonshire in 1947 and sold for scrap to Cashmore Ltd, 26 March 1949 at Newport, Wales, BU from May.

HMS Hawkins

HMS Hawkins

HMS Hawkins in 1944

HMS Hawkins became flagship of the 5th Light Cruiser Squadron, China Station from September 1920 and until 1928. Back to Chatham on 12 November she had a major refit (boilers changes, less speed but 20% more range, FCS and gunnery changes), recommissioned on 31 December 1929 and assigned as flagship of the 2nd Cruiser Squadron, Atlantic Fleet until back to reserve on 5 May 1930, but recommissioned in September 1932, as flagship, 4th Cruiser Squadron, East Indies Station and back to reserve in April 1935. Due to the new London Naval Treaty entering into effect, tonnage was to be reduced, she was due to be demilitarised in 1937–1938 having all main guns and TTs removed, but by September she was announced instead converted as a cadet training ship and allowed disarmed in effect, stored.

By September 1939, she was rearmed and saw her AA battery reinforced by with a 2-pounder AA gun and she was reclassed as a heavy cruiser in January 1940 but sent to the South American Division (North America/West Indies Station), looking for German commerce raiders after the loss of Graf Spee.

In January 1941 she was tasked to escort convoys off the West African coast. She rescued part of the crew of the oil tanker British Premier on 3 January, torpedoed off Freetown by U-65 and in February she HMS Formidable to the East African coast and Suez Canal, attacking Mogadishu underway on 2 February. Next the cruiserm was assigned to Force T to support the invasion of Italian Somaliland, with three other cruisers and HMS Hermes. On 10–12 February she captured five fleeing Italian merchant vessels from Kismayo for 28,055 GRT. Next on the 22th she escorted WS-5BX off Mombasa, detached to search for Admiral Scheer, spotted by a British aircraft.

She stayed escorting convoys in the Indian Ocean and detached to look for Axis commerce raiders, until back home for a refit at HM Dockyard in Devonport, on 4 December (AA, radar, new FCS) until May 1942. Back in the Indian Ocean she was reassigned to the Eastern Fleet as war broke up with the Japanese here, but stuck to convoy escort until mid-1944. Sge coould not prevent the sinking of SS Khedive Ismail by I-27 on 12 February 1944 but rescued many survivors. She was soon back home via Scapa Flow, Lough Neagh and a refit in the Clyde plus exercises before to be prepared for the Normandy landings. From the 1st Cruiser Squadron she was assigned to the Western Task Force Gunfire Support Bombardment, Force U (Utah Beach). On 6 June she shelled the Grandcamp-Maisy and Saint-Martin-de-Varreville batteries.

She was paid off in July, in Rosyth, Scotland and convertion into a training ship as many new cruisers had been built in the meantime. Her AA armament was modified again on 8–23 August. In September she took part in the Highball trials in Loch Striven but the conversion was cancelled in May 1945 and instead she was put into reserve, laid up in the Fal until 1947, used for target trials against 500-pound (230 kg) and 1,000-pound (450 kg) bombs dropped by Avro Lincoln bombers from 18,000 feet (5,500 m) off Spithead exaclty two years after her mothballing. In 27 days she took no less than 616 bomb drops, with only 29 directly struck her and 13 failed to detonate, showing once and for all the limitation of high altitude bombing against ships and definitively convincing the admiralty that the missile was the way forward in air attacks. Hawkins was transferred the Iron & Steel Corp. on 26 August 1947, BU December 1947 at the Arnott Young scrapyard in Dalmuir (Scotland).

HMS Vindictive (ex-Cavendish)

HMS Vindictive (ex-Cavendish)

In January 1917, the Admiralty reviewed its aircraft carrier requirements and decided for combining a flying-off deck forward with a landing deck aft. The 1917 order was cancelled in April 1917 as no shipyard was available for a new built (Hermes was the only one laid down, p, 15 January 1918). It was decided for a shortcut, converting the already built Cavendish in June 1917. She combined the advantages of a well advanced cosntruction, but not enough for completing carrier modifications and having the right size. She was renamed “Vindictive” later in prder to pay hommage for the heroic Cruiser of the Second Ostend Raid. Priorities then were shifted out form her sisters to this new cruiser, even rushed to be in service before a possible end of hostilities.

She only saw limited service before the end of hostilities under her new name, and starting operating a variety of undercarriage models and took part in the Russian civil war 1919 operations, notably at Kronstadt, even launching the first air raids. However like her larger sister Furious she showed the concept of “cruiser carrier” was doomed due to the turbulences created by their structures, HMS Argus being more successful in operations, with far less accidents. Thus, decision was made to reconvert Vindictive into a cruiser, and later rebuilt Furious as a true aircraft carrier.

Vindictive back as a cruiser in 1926, China Station

HMS Vindictive after being completed as an hybrid aircraft carrier with a capacity for six reconnaissance aircraft was briefly armed with four 7.5 in guns and six 12-pounder guns but in 1923 was converted back as a cruiser, only retaining a forward hangar and instead of ‘B’ gun a crane and catapult were fitted.

Vindictive for her first and only operational campaign as a carrier, was sent to the Baltic with 12 aircraft and on 2 July 1919 started missions of support for the hard-pressed White Russians and newly independent Baltic states. On 6 July she ran aground on a shoal near Reval. Stranded, her crew managed to dump her fuel overboard and ammunition to light her up, but it was not enough. Soon 2,200 long tons (2,235 t) of stores were off-loaded and thiswas still not enough despite the efforts of both cruisers Danae and Cleopatra and three tugboats. Eight days after an unxpected westerly wind allowe to raise water by 8 inches (203 mm), and this enable her to pull free. It happened later that the whole squadron was right in the middle of a minefield.

Vindictive had to unloaded her air group (Major Grahame Donald) at Koivisto in Finland on 14 July to continue operations in better conditions. The airfield was still under construction when they started to fly daily missions of reconnaissance over Kronstadt, from 26 July. Vindictive meanwhile sailed without her air group and ammunitions or even lacking fuel, to Copenhagen first, to load aircraft and spares left for her by Argus which went back home. On the 30th, Rear Admiral Walter Cowan ordered Major Donald and his air group to attack Kronstadt at night and some were flew off by Vindictive, which had her flying-off deck extended. But the mission petered out due to Accurate AA fire. The bombers had to climb to drop their bombs, which was highly effective. Some pilots still claimed hits on the tender Pamiat Azova, but in reality this was the oil tanker Tatiana, which burn for hours. Raids were abandoned and Vindictive was now repurposed due to her facilities as a CMB tender, for eight Coastal Motor Boats for the remainder of the campaign.

Meanhile the airfield was complete and Major Donald resumed operations by day, in support of British operations against the Bolsheviks until December. They notably shot down a Bolshevik helium-filled observation balloon and spotted for shore bombardments. There was another night raod on 17/18 August 1919 with eight bombers escorted by fighters, providing a diversion for an attack by Vindictive’s CMBs on Kronstadt harbour. They damaged Andrei Pervozvanny and sank Pamiat Azova. In another raid they hit Pervozvanny while in drydock, damaged a minesweeper, hit two auxiliary ships. By December the White Russians could not hold the “reds” anymore and started to be evacuated, while the British started withdrawing. HMS Vindictive left three Camels for local defence in Latvia but embarked the rest of her air geoup and set sail on 22 December.

Vindictive was paid off into reserve at Portsmouth on 24 December and had grounding damage repairs for £200,000. Like Furious in the same “cruiser-carrier” configuration she showed to be unable to recover the aircraft and that a through deck carrier with island was preferrable. Converison projects were dropped in the new 1921 austerity context. When not mothballed she was used as troop transport, and she started reconversion back into a cruiser at Chatham from 1 March 1923, restored to her original configuration, but with three QF 4 inch Mk V AA guns instead of 3-in guns (between aft funnel and mainmast and quarterdeck between the two upper main guns). She still retained her hangar forward in place of her “B” main gun but her two derricks were replaced by a single crane, starboard side and had instead a prototype compressed-air Carey aircraft catapult. So Vindictive became the prototype for such systems. On 3 October she launched a Fairey IIID floatplane and had catapult trials with float-converted Fairey Flycatcher fighters. She was sent on 14 March 1928 to the China Station on 1 January 1926, her hangar filled with six Fairey IIIDs for anti-piracy patrols in this summer but her catapult was removed in October. She reduced to reserve in 1929 and by July 1935 left the reserve to join the King George V’s Silver Jubilee Fleet Review.

As Cadet TS

Vindictive as Cadet TS in 1938

In 1936–1937, she demilitarised after the London Naval Treaty, converted to a cadet TS: Two inboard propellers and corresponding turbines and boilers removed, the freed compartments were converted into accommodation for the dacets and instructors. The aft funnel was removed and aft superstructure remodelled, enlargedinto classroom as well as the hangar for more accommodation space. She ended with just two 4.7-inch (120 mm) guns forward and a quad QF 2-pounder (“pom-pom”) AA mount aft, dispacement down to 9,100 long tons (9,246 t), 24 knots when recommissioned on 7 September 1937.

As Repair ship in WW2

From August 1939, she was transferred to Devonport for modernisation like Effingham. Nine 6-inch (152 mm) guns were installed as well as four twin shielded 4-inch (102 mm) mounts and a catapult but under low priority and later a more austere modernisation considered: Six 6-in guns, three 4-inch single AA guns, former aft boiler room converted from a laundry into an oil tan for extra range. But this was abandoned and instead she was converted as a fleet repair ship. Her armament was removed, forward superstructure extended over the hangar’s roof, aft superstructure extended flush with her sides, slightly lengthened, large deckhouse on the quarterdeck. As completed she had no 6-in, but six 4-inch QF Mk V AA on the centreline, two qua “pom-pom” mounts (either side), six depth charges, displacement 10,000 long tons but (12,000 long tons full load, draught 20 feet 3 inches (6.2 m).

Vindictive nearly hit by bombs while at anchor in Harstad Fjord, 17 May 1940

As such she was completed on 30 March 1940, ans was used as a troop transport for the Norwegian Campaign, notably to Narvik in late April, then escorted an evacuation convoy from Harstad on 4 June. During her stay she had seen Luftwaffe air raids and had some close calls. She acted as AA platform for the troopships around (photo). Later she transferred to the South Atlantic station and stayed there until late 1942, and while back to the Mediterranea, west of Gribraltar, she was attacked in the night of 12 November by U-515, but evaded the torpedoes. U-515 sank th tender Hecla and blew the stern of the destroyer HMS Marne. Vindictive remained in the Mediterranean Fleet until 1944, and was later recalled for Operation Overlord.

By August 1943 she was modernized in Girbraltar, receiving a Type 286 target indication and a Type 285 AA gunnery radar. By January 1944 this was the Type 291 air warning radar and she had six more Oerlikon 20 mm AA guns, three on each side of the workshop roof abaft the funnel. In 1944 she was converted into a destroyer depot ship and received six more Oerlikons AA guns, later lost her 4-inch guns for eight more Oerlikons. She took part of the D-Day operations in June-July, supoporting Destroyrs of the channel fleet. By early August 1944, she was was damaged by a long-range “Dackel” torpedo, dropped by a German aircraft off the coast of Normandy but was quickly repaired. In 1945 she received six more Oerlikons. and eventally came back home in May 1945. She was paid off on 8 September 1945, sold for scrap on 24 January 1946 at Blyth.

HMS Raleigh

HMS Raleigh

HMS Raleigh at Pier D, Vancouver (side)

HMS Raleigh, named after Sir Walter Raleigh (1553 – 1618) was laid down at William Beardmore & Company in Dalmuir on 4 October 1916, launched on 28 August 1919 and completed on July 1921. HMS Raleigh had the shortest career of any ship of the class with just a year commissioned before being wrecked after running aground at Point Amour, Forteau Bay in Labrador on 8 August 1922. How it happened ?

6th ship of the name she started training under Captain Arthur Bromley from 14 February 1920 and she was to be the flagship of Vice-Admiral Trevylyan Napier, CiC, North America-West Indies Station (Later the sum of the Carribean, South American and Pacific Station in 1926). She departed on 26 July for the naval base of the Imperial fortress colony of Bermuda for the admiral to board her, but he passed out on 30 July wile she was underway.

Sir William Pakenham replaced him as new commander and hoisted his flag aboard on 12 August. She then made her first sortie as such to Montreal, Quebec, on 1 September and in December, she was back to the warm waters of Bermuda and then stopped in Jamaica, crossed the Panama Canal in January 1922 and visited San Francisco on the 21st. She was back to Bermuda and stopped in several ports in the Chesapeake Bay including Washington, D.C. in May 1922. In July she was back to Canada and stopped to be open to general public. On 3 August, Pakenham transferred his flag HMS Calcutta.

HMS Raleigh at Pier D, Vancouver (prow)

On 8 August, Raleigh was underway to Forteau, Labrador coming from Hawke’s Bay in Newfoundland. She soon encountered entered heavy fog in the Strait of Belle Isle and despie reading the maps, she ran aground at L’Anse Amour that afternoon. It was 15 minutes after entering the fog bank and the grounding was mild, but strong winds, which also chased off the fog, blew her stern onto the rocks, holing her hull and soon flooding cause a 8° list. 12 drowned by hypothermia after it was ordered to abandon ship, and the remainder found shelter ashore and created fires to stay warm before a rescue could come. Officers were sent further inland to contact help.

HMS Raleigh hard aground at L’Anse Amour, August 1922

Help was found, crews were gathered in a twon hall and other nearby building before trucks arrived and officers went back the next morning to evaluate HMS Raleigh’s condition. They also sent a party to recover personal belongings. It was soon discovered that the winds and rocks conspired to create a 260-foot-long (79 m) gash in the hull and leaking fuel oil stuck everywhere. HMS Capetown and Calcutta arrived with the tide and gathered some of the crewmen but bad weather hampered more operations. The bulk of the crew, which found refuge in the meantime to Forteau, were sent by truck to the neartest port to be transported back to Britain by the 18,481-gross GRT Canadian ocean liner RMS Empress of France from 10 August. The captain refuse to set sail as not having necessary provisionsand after a few more days they were evacuated by the 16,402 GRT ocean liner SS Montrose. The emainder of the crew was still back to the wrecksite to try and salvage what they could and ensure locals will not do the same. She was stripped and abandoned upright. Captain Bromley and his navigator back in UK were court martialled, found negligent, severely reprimanded and dismissed, both requested retirement.

Embarrassed by the sight of the stranded cruiser, which could not be towed away without patching up the hull and refloat her first, a long aznd costly operation, the Board of Admiralty in the new budget-stripped context decided it was not worth it. Declared a hazard to shipping in 1926 she was to be refloated, derspite studies said it was impossible. She was instead to be, if possible, scrapped on site and the remains blew apart using depth charges. The task was given to no other than a young Captain Andrew Cunningham from 23 September although the date is disouted by historians.

There was before that a third round of stripping. RCN divers teams revisited the submerged remains of the wreck in 2003 and 2005 and apart a comprhesive survey, they managed to refloat live 7.5-inch ammunition…

Raleigh sunk at Point Harbour, 1922.

Resources

Books

Conway’s all the world’s fighting ships 1922-1947

Brown, David K. (1987). Lambert, Andrew (ed.). “Ship Trials”. Warship (44)

Friedman, Norman (1988). British Carrier Aviation: The Evolution of the Ships and Their Aircraft. NIP

Friedman, Norman (2010). British Cruisers: Two World Wars and After. Barnsley, UK: Seaforth Publishing.

Friedman, Norman (2011). Naval Weapons of World War One: Guns, Torpedoes, Mines and ASW Weapons of All Nations, Seaforth Publishing.

Layman, R. D. (1989). Before the Aircraft Carrier: The Development of Aviation Vessels 1859–1922. Annapolis NIP

Morris, Douglas (1987). Cruisers of the Royal and Commonwealth Navies Since 1879. Liskeard UK Maritime Books.

Raven, Alan & Roberts, John (1980). British Cruisers of World War Two. NIP

Rohwer, Jürgen (2005). Chronology of the War at Sea 1939–1945: The Naval History of World War Two (3rd Revised ed.). NIP

Smith, Peter C. (2015). Sailors on the Rocks: Famous Royal Navy Shipwrecks. Barnsley, UK: Pen & Sword Maritime.

Whitley, M. J. (1995). Cruisers of World War Two: An International Encyclopedia. London: Cassell.

Links

battleships-cruisers.co.uk hms_cavendish

on navypedia.org

on en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org HMS_Vindictive 1918

forcesnews.com/ hms-argus-first-aircraft-carrier

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign