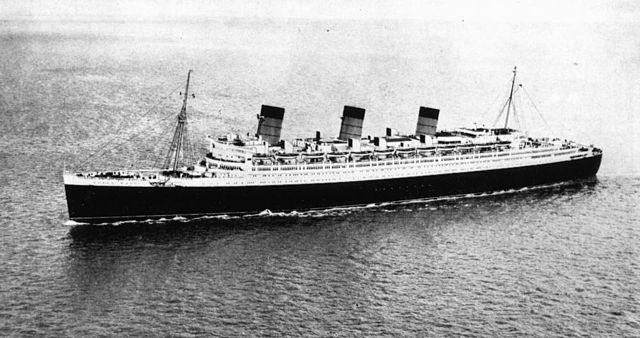

SS Normandy (1936, French Lines), one of the most classic and gorgeous ocean liner ever…

Ocean liners descended from “packet boats”, steamers built to carry mail, which incidentally also carried passengers in the XIXth century. This started with not really passenger-friendly steamers to the classic rival liners that chased the famous “blue ribbond” fast, luxurious leviathans on the conveyed Atlantic line (to New York) in the 1900-1940, and to this day, immense glass and steel floating hotels/theme parks that represent modern cruise industry.

Here is the actual list (more to come):

- SS. Great Britain (1843)

- SS. Atrato (1853)

- SS. Oregon (1883)

- SS. Britannia (1887)

- SS. Ophir (1891)

- SS. Canada (1896)

- SS President Grant (1906)

- RMS Titanic (1912)

- SS France (1912)

- SS Homeric (1921)

- SS Empress of Britain (1932)

Definition

What is a liner ? A ship capable of following a regular “line”, which was the definition of a maritime route between two points, with a regular service. Needless to say it has to do with steam. Before steam power, ships relied on wind power (and rowing, but on coastal areas and enclosed seas like the Baltic, Mediterranean and also rivers). Wind is of course not predictable, although signs and pattern of the sky could be readable for those who manned these ship in open air, “true sailors” or the “old salts”.

Steam, developed from 1800 was not only the start of the industrial revolution, it was also the start of a deep transformation of navigation. Because of raw power and reliability issues, but also some resistance from the sea community and the navy steam power for long has to exist alongside sail, at least until the late 1870s. In the 1830s, steamships were longer a rarity, they were everywhere, relying at that stage on paddle wheels. The screw had yet to be tested.

Steamships of that era bring something on the table which was brand new: Regularity. They could sail from, and arrive to, any destination in the imparted schedule, which was unheard of since most sailships could be stranded either in a totally ‘flat’ sea for days (completely deprived of wind) or having to re-routing to another direction in case of incoming storm, delaying their voyage again. Perhaps when the art of sailing for trade reached its zenith, the Clipper era (1850-1870) showed sail can be significantly faster on any given route;

But on the long run, the regularity of steamships compensated for their relative slowness. Clippers started to carry passengers on a regular basis at that moment, but at the same time classic steamship were mostly used to carry mail, and the name applied for them in the British language was “packet-boat”. It was also translated in French as “paquebot” which is still used to describe a liner.

Therefore, a “liner” was a generalization for all types of ships (mixed, therefore steam and sail) which followed the same route. It did not excluded that a ship could re-route in case of a storm, nor that a steam engine could breakdown, but the security of sail (and addition of, in some case) allowed a captain to reach its schedules on a far more reliable way. Therefore a “liner” become synonymous with regularity of service.

It could have been extended to all steam navigation, including for cargo, but at that stage many of these 1840-50s mixed steamships carried passengers AND cargo, and sometimes made many stops on their way. It has been generally understood that a “liner” reached point A to point B with no or a single stop to gather more passenger. And with the attractiveness of the new world and the difficulties of Europe, transatlantic lines begin to appear. So nowadays it’s assumed that a liner is:

-A passenger ship (which can carry also mail and freight)

-A ship sticking to a regular, long maritime line, with limited or no stops en route.

Modern Ferry boats, even if they made just a few nautical miles, are considered “liners”, but not cruise ships, in both accounts. Needless to say “liners” disappeared in the 1960s, with the advent of jet airliners, which just succeeded them.

The first Liners

As said before the beginning of the century saw many steamships being tested, and the first “lines” on rivers or short distances (Like 1811′ Henry Bell’s Comet) but it’s really in 1820 that things really get going. And this was done by an American ship, the SS Savannah (see first steamers). The Savannah was small, a dwarf compared to many sailships of that time. And she was slow, making the trip from Savannah, Georgia to Liverpool in a blasting 28 days;

The major issue at that time, by a wide margin was …water. Indeed, indeed boilers by then needed large quantities of water to produce steam, which came from the sea. As a result, salt rapidly encrusted the boilers, which had to be removed on a regular basis – every two days in fact. This was a painful and backbreaking work to say the least. Meanwhile, sails just took the relay, until the whole operation was completed and the boilers hot and ready again. There was however soon the invention of condensation balloon, allowing to recycle steam into fresh water. In the following decades, two, three and even four stages of expansion allowed to use every bit of steam to produce movement.

The other limitation was coal. Indeed, coal was taking a large space onboard, reducing therefore the overall carrying capacity. In addition coal supplies were to be installed in many stations around the globe to ensure steady provisions on the longest routes. This explains why the Australian and pacific areas were reached so late by liners. In addition, coal was a pain to work with. Coaling was a long, backbreaking operation, with a toxic cloud of coal dust that settled everywhere; Quite a nuisance for a passenger ship. But the move was started. Just as the locomotive and railroads conquered land, steamships conquered gradually the most remote places on earth, on a steady, regular basis.

Carrying passengers was at first, just an afterthought. There were paying passengers which just “piggybacked” on decks, living with the crews, but an evolution towards more comfort for paying (and wealthy) passengers stirred some ship owners and lines managers to insert cabins with and accomodation dedicated to passengers. This was the start, but there was still a long way to go before the advent of democratization of passenger transport. This only came with larger, more stable ships.

The legend of Cunard

British subject Samuel Cunard could be granted the title of precursor of passenger lines; In 1840 he ordered four paddle steamship to carry cargo and passengers on a regular basis between Liverpool and Boston, crossing the Atlantic every two months. He literally wrote the guidebook of transatlantic lines. The SS Britannia was soon celebrated by Charles Dickens was the first “packet boat” as she carried mail (in small packets). However the name could also be related to the freight which was generally bagged and carried in bulk in large nets.

British subject Samuel Cunard could be granted the title of precursor of passenger lines; In 1840 he ordered four paddle steamship to carry cargo and passengers on a regular basis between Liverpool and Boston, crossing the Atlantic every two months. He literally wrote the guidebook of transatlantic lines. The SS Britannia was soon celebrated by Charles Dickens was the first “packet boat” as she carried mail (in small packets). However the name could also be related to the freight which was generally bagged and carried in bulk in large nets.

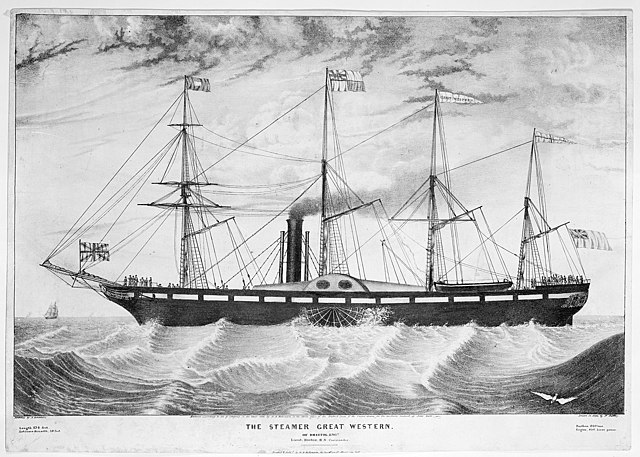

Isambard K. Brunel was certainly a serious contender to Samuel Cunard, and possibly the best engineer of his time. Even before he inaugurated his famed Great Western Railway in 1835, he also projected a regular line between Bristol and NyC. He funded the Great Western Steamship Company, headed by his trusted associate Thomas Guppy. Combining large size to carry more coal applying the experimental evidence of Beaufoy, combined with surface condenser for boilers, he argued the only way forward was a larger ship. In 1838 he launched the Great Western.

For her time, this ship was a masterpiece. Still an oak-hulled paddle-wheel steamship, she was nevertheless prodigiously large, carrying 1,340 GRT, later 1,700 GRT, displacing 2300 ton, while being 71.6 m (234.91 ft) (later 76.8 m/251.97 ft) long, by 17.59 m (57.71 ft) across wheels, which were moved by a 2-cylinder Maudslay steam engine rated for 750 HP, bringing her to 8.5 knots. She of course was also fully rigged and her clipper-style hull allowed a fraction of this speed on sail alone, although the drag of the large hull and wheels was considerable. More importantly she carried 128 passengers in 1st class and 20 servants plus 60 crew and officers. Living quarters for passengers was a step above anything made before, with precious woods and furniture and the equivalent of a first class Hotel service. She was als the longest ship in the world, but was alone, meaning the line could only operate a crossing at best once every month;

(Author’s illustration) The 1843 SS Great Britain also innovated in another way: She was the first liner with a screw instead of paddle wheels. The innovation made the ship quieter, and safer as paddle wheels could be wrecked by bad weather or collisions. The Navy was soon interested, but it would take until 1849 for a large warship propelled that way to materialize (the French Le Napoléon), triggering a wave of new constructions and conversions by the two leading navies of the time, right in time to participate in the Crimean war.

In short, the SS Great Britain was really the first, true, transatlantic liner. She was large enough and well equipped enough to accommodate many more paying passengers than any ship before, and it was fast: In 15 days she was able to reach New York, burning 1,100 tons of coal to do so. In the 1810s, that was reduced to just four-five days, showing the immensity of progress done there.

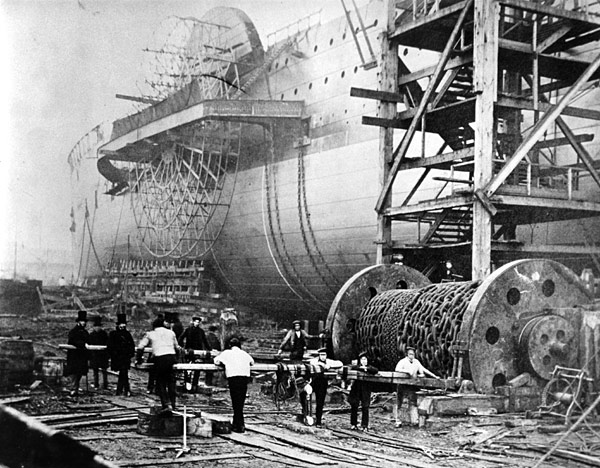

Failed first launch of the Great Eastern, showing her scale. Oddly enough, she was fitted with a screw propeller AND paddle wheels in addition to rigging.

In 1848 of course, a big step forward was carried out by the order of the SS Great Eastern, Isambard Kingdom Brunel’s pet project and at that time not only the first steamship entirely in iron but also the largest ship afloat in 1852, dubbed “Leviathan”.

The Great Eastern was the ship of all superlatives. Still using the same principle that the more larger the ship became, the more efficient she was related to her coal capacity, he designed a behemoth, so inflammatory of imagination that she was also the subject of Jules Vernes famous novella “the floating city”. She was almost 700 ft (210 m) long, and fitted out with the most luxurious appointments with a total capacity of 4,000 passengers in various classes (already!). The size was just a traduction of her intended route: London-Sydney. She was to be able not to stop anywhere for coaling along the way.

However, the ship was so humongous her launch proved almost impossible. And afterwards, proved to be an economical failure. She was a white elephant when operating from 17 June 1860, just too ahead of her time, and remained the largest ship afloat for more than 40 years (until 1899’s SS Oceanic), ended her career in peculiar roles, without much glory. Brunel’s project most often than not ran over budget and behind schedule, facing along the way series of technical problems.

Cunard on the other hand was nothing of the sort. A cold, reasonable businessman using proven technologies in a larger scale. He was the real progenitor of transatlantic lines and would in the future certainly not shy before large ships when they could generate some profit.

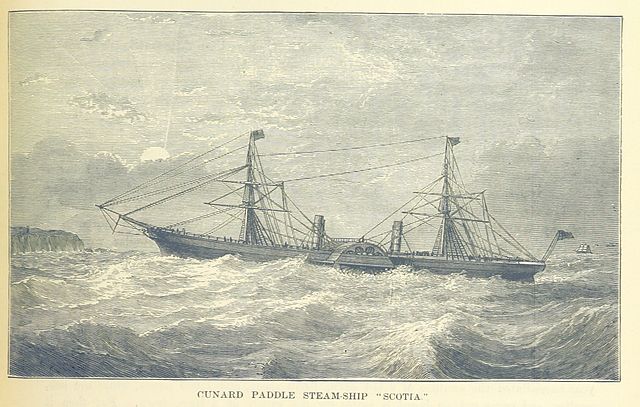

After his first four liners, he ordered his last paddle wheeler, the Scotia, burning 140 tons of coal everyday. The Scotia was able to reach New York from Queenstown in just eight days, and the idea of a prize, the blue ribbond, was not far away. His last wooden ship was the Arabia in 1853, just after the first freezer was installed on the Cleopatra. 1st class passengers saw quite improvements in the 1850s, but second-class ones, those between decks, carried their hammocks with them.

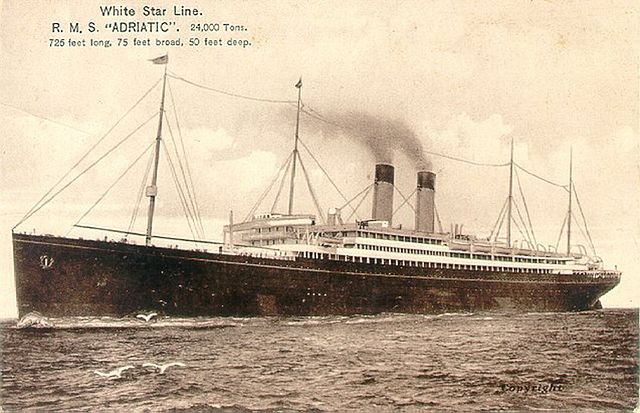

Despite these progresses indeed, sea travel was still not for the faint-hearted: Sea sickness as the ship rolled badly, brutal moves, no artificial lighting, nor heating, and limited food made of cans and sea biscuits, and little to do but wandering on the main deck until noon. Central heating only appeared in 1878 on the SS Adriatic, using gas lighting for the first time.

But it’s really from 1900 that liners reached their golden age, which would last until 1970. They really embodied the best of luxury, grace and power, gradually improving their time in the most prestigious of all lines, the Transatlantic one. The main revolution mirrored the improvements in ship propulsion. While the triple and quadruple expansion steam engines, with boilers soon converted to oil, steam turbines made their promising debut.

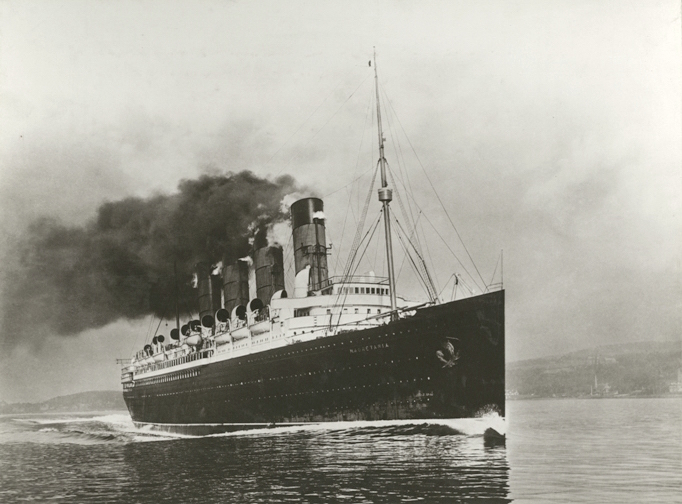

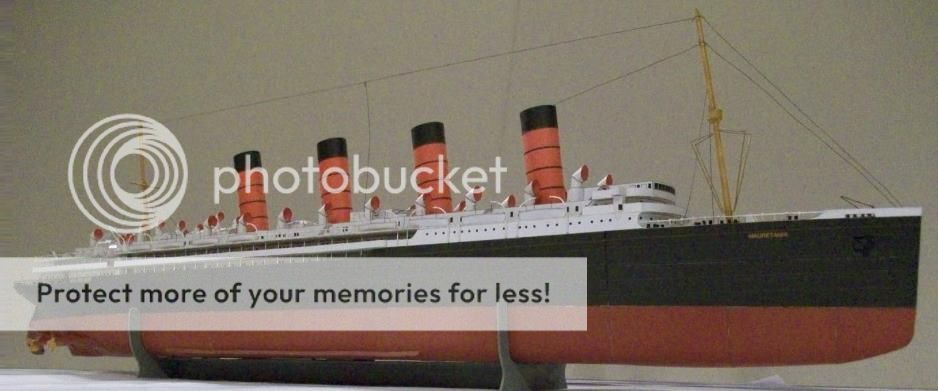

As speed was part of the package sold by any transatlantic line, steam turbines soon found their way in liners as well. The Brown-Curtis turbine, an impulse type, originally developed and patented by Curtis in the 1900s was installed first on the Curnard’s RMS Lusitania and RMS Mauretania, the fastest ships on earth at that time in 1906.

The same year the Royal Navy launched the first battleship with turbines, HMS Dreadnought. She was able to reach 21 knots, while the Mauretania won the blue ribbond first at 22 knots, but she was designed to cruise at 24 knots, which was unheard of at that time. She held the record for a passenger ship for… 20 years, quite an achievement.

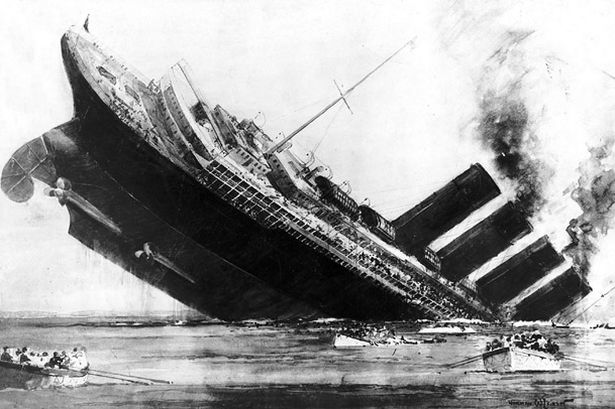

Confidence in technology and opulence in luxury, backed by the masses of immigrants which really paid for the whole enterprise, spawned legendary ships the public never forget to this day. However overconfidence also led to disaters. Such was the case of RMS Titanic in 1912, which led to a tragedy, and a serious re-examination of safety measures at sea. The Titanic was just one of three liners, with the Olympic (1911) and Britannic (1915), that matched Cunard’s ships for the famous rival line, the White Star.

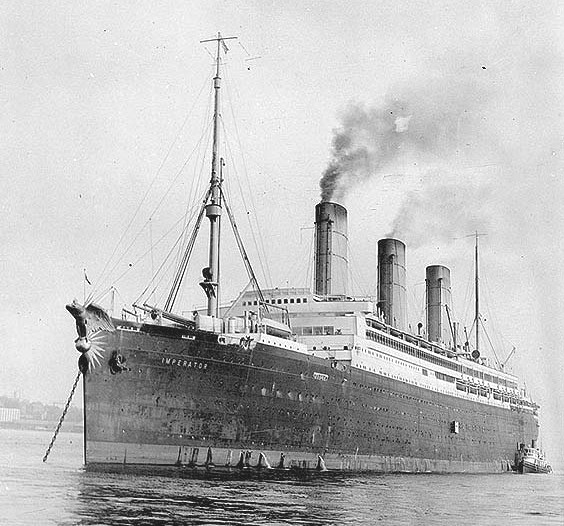

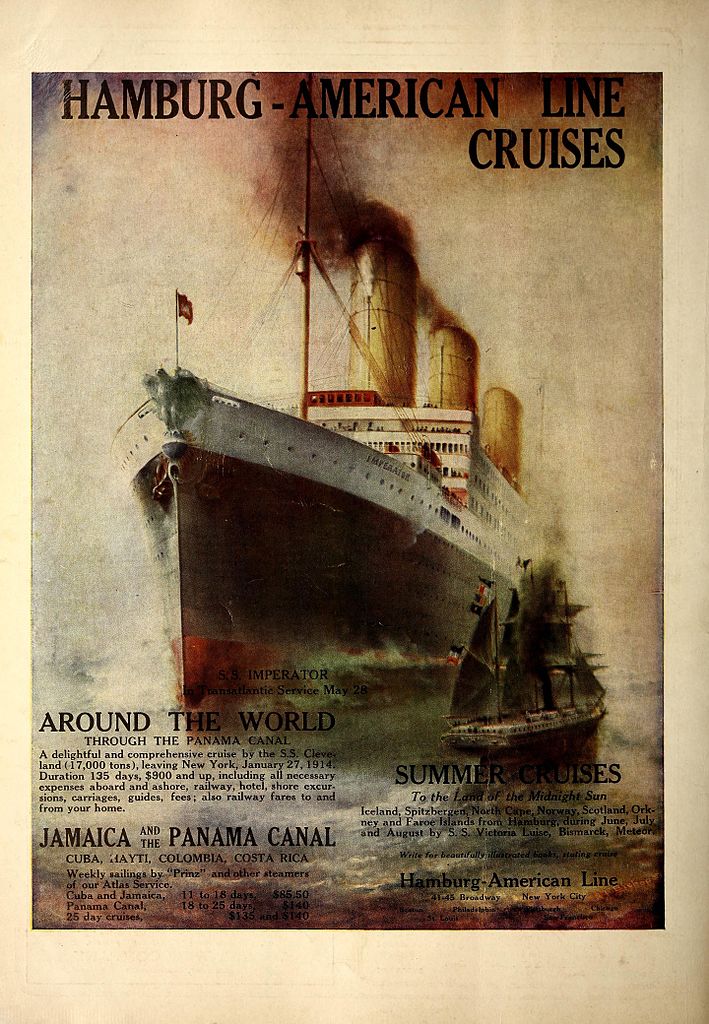

At the same stage, France tried to compete by creating the CGT or Compagnie Generale Transatlantique in 1912, launching for the occasion the SS France, not the fastest but certainly one of the most luxurious. Germany, not to be undone on this prestigious competition of engineering and craftsmanship, created the same year the Hamburg America Line. Soon the Kaiser unleashed his credits lines with in 1913 the SS Imperator followed in 1914 by SS Vaterland, larger than Cunard’s liners. The Bismarck’s construction was suspended as the war broke out.

The Great war, liners in battle dress

It would be misleading to think the war stopped passenger lines to continue service around the globe. Wherever they were not impacted by war, at first constrained to the Flanders and champagne in northern France or the Russian border, the Balkans, passengers and freight went on despite material and manpower shortages, whenever possible.

The transatlantic line at first was not even impacted. The Unites State’s own lines and liners continued to work until the the sinking of RMS Lusitania in 1915. From then on, submarine warfare became systematic and ugly, and would only grow in strength and ferocity until the end of hostilities, three years after.

Submarine warfare however rarely hit great liners. They were fast, while submarines were slow. It was only a combination of luck and skills which allowed the commander of U20, Walter Schwieger to ambush the liner on her expected route. The result, as we know was way more than a tragedy. This triggered the start of a rapid shift in the population against Germany, and up to a declaration of war in 1917.

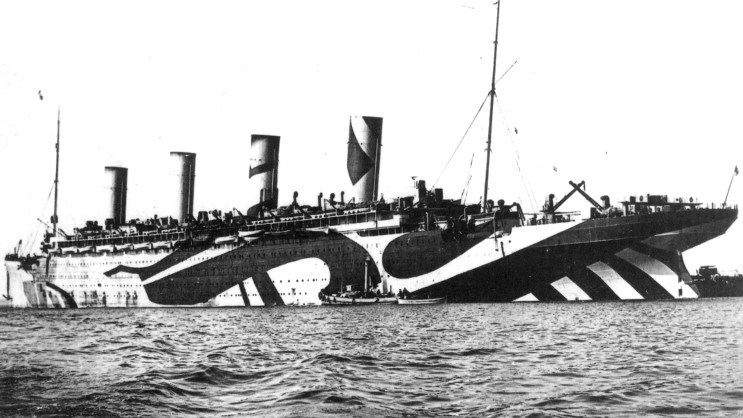

When carrying passengers became perilous, liners became either troop transport or hospital ships, their appearance changing from colorful razzle dazzle to white dotted with red crosses of the second. With all their luxury fittings gone, making way to practical housing, entire divisions could be carried onboard these gargantuan hulls, under the vigilant protection of destroyers. Smaller liners, of secondary lines and ferries also played often significant roles.

The first naval action of the war was led by Germany, with the Königin Luise, a modest liner converted as an impromptu minelayer, with deadly consequences. In the night that followed the declaration of war, she slipped into the Thames estuary, laying minefields which would later claim many ships, before being caught and sank.

Other liners became auxiliaries, sometimes completely rebuilt as aircraft carriers (like the Campania) or seaplane carriers. Other were armed and used as escort vessels and auxiliary cruisers.

Interwar Years: The golden age of liners

Luxury hotels of the modern cruise industry :

Norwegian Epic of the NCL (built in St Nazaire, issue: May 2010 – 330 meters, 153,000 GRT, 14 restaurants, 18 bars and lounges, 7 bridges and 2109 cabins.

Transition (1970-1990) :

There is no doubt that cruise market remains flourishing despite the crisis. The concept was born when the last great transatlantic liners disappeared, victims of the aviation after the war. Yet these great floating palaces, since the beginning of the century had rivaled two chapters: Luxury on board and speed, not to mention their dimensions.

The time when the new fortunes of the industry of the first classes lived in a pomp worthy of the European nobility, while the interior’s dephts were crowded by candidates for emigration from all over Europe to the new world. The goal is no longer to travel, but to live on board. The new floating palaces of the 21st century are thus motorized floating cities, neither more nor less.

Since the 90s, the date of the explosion of this new market, several companies have established themselves: The very first pioneer of the genre was the NCL (Norwegian Cruise Line), followed by the Royal Carribean Cruise Line (RCCL) of Knut Kloster and Edwin Stephan, two Norwegian shipowners who felt demands for this new market.

Their approach to the new ships was radical and will hardly change since the 1970s: While classical Liners were built around an enormous propulsive group capable of exceeding 33 knots, they had several classes, relatively poor in recreational facilities and with a non-negligible load of goods.

The new cruise liners were to be floating hotels, designed for and around one-class passengers, very rich in leisure facilities, and designed for one-week trips to paradisical destinations, with one stopover per day. In 1970, three buildings were built, the Nordic Prince, Song of Norway and Sun Viking, by the Finnish shipyards Värtsilä of Helsinki, the future leader in this field.

Other projects, such as Fincantieri, Howaldswerk in Hamburg, Meyerwerft, Naval Union of Levante in Valence, Saint Nazaire, Papenburg, Vickers-Armstrong and John Barrow, were also solicited for similar projects.

Several were indeed based on the success of the two Norwegian owners: The current US leader, the Carnival Cruise Line, Princess Cruises, Costa Cruises, Crystal Cruises, Disney Cruises, Regency Cruises, Celebrity Cruises, Star Cruises, and famous companies such as the Cunard, P & O, Holland America Line, and other mining companies that found new, juicy outlets, even if it entailed a radical overhaul of former liners dating back to the 1950s and 1960s.

From these giant companies, they arm four to twelve cruise ships and more, and offer year after year, more and more facilities, cabins, and a debauchery of tinsel according to the American taste, strongly inspired by the delusions of the hotels of Las Vegas.

Thus these liners since the 90s, have swelled spectacularly, matching and surpassing in dimensions all liners of yesterday. One can quote for example the Grand Princess of 1997 and her 283 meters for 104 000 GRT to compare with the legendary Norway, ex-France, with her 315 meters and 76 000 GRT. It was during the 1990s and especially 2000s that cruise ships crossed the limit of 300 meters. Due to their unmatched interior layout, life on board even improved due to the ratio between passengers, livable space (cabins of 12-25 m2 on average), recreational areas, and prolific personal.

Interiors diversified greatly: From the turn of the century sports fields and swimming pools on the upper decks, restaurants and concert halls were commonplace, but since the 1990s all the eccentricities of modern construction seem to have been reached: Atriums on 5 to 9 levels lined with glass lifts and tropical plants, giant shopping malls sometimes as long as the ship itself, even real streets reconstructed like Broadway on CCL ships. This, added to athletic-size swimming pools for Las-Vegas type water-shows, numerous theme restaurants and bars, operas and theatres, open air aqua-parks and golfs, rock climbing… There seems to be no limits to the industry’s imagination, in a race to awe in entertainment.

Nothing seems to restrain the ardour of shipowners in terms of gigantism and facilities: The last liners in the computers or in construction sites are all overpanamax of more than 350 meters and 180 000 GRT. The Freedom of the Seas, the flag bearer of the RCCL and its 340 meters, the Queen Mary II of 346 meters, the Genesis of 360 meters… were only a prelude: The current Pharaonic projects, of these future buildings the biggest movable objects ever built of the human hand (but not the heaviest ones, like the supertanker Jahre Viking and its 565 000 GRT)

Thus the Oasis and Allure of the Seas, two giants of 380 meters, 220,000 GRT, 16 bridges, 2700 cabins and 5400 passengers, would be the first to offer a central space open on most of the ship, open to the rear. Another, more hypothetical project is the floating island of Alstom Marine designed by architect Jean-philippe Zoppini and 400 meters long, 300 wide, 30 high apartments, an inland marina and 10,000 passengers (below). Or the Princess Kayuga, its 505 meters, 20 bridges and 550,000 GRT, designed to have all the functionality of a self-contained floating city.

But the biggest and utopian of all is undoubtedly the Freedom Ship, a kind of floating barge of 1317 meters long by 221 wide, the upper deck serving as an aerodrome and having 18,000 habitable modules for permanent residents. The ship would be a kind of “floating country”, with its own citizenship, which would sail in the offshore zone for years… Like any good utopia, for the time being this project has not found investors.

Read more:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ocean_liner

http://www.fr.naval-encyclopedia.com/navires-civils.php

Nomenclature of Liners since 1820

Work in Progress

SS Atrato (1853)

The ship SS Atrato was launched at Caird and Co. of Greenock in Scotland. It was then the largest ship in the world. It had wheels and not a propeller and was entirely made of iron. This was the first of this type issued at the Royal Mail Lines. It was however lighter than the famous Great Britain, ten years earlier, and more end of line. It was sold in 1880 to Adamson and Ronalds Lines, under the name of Rochester. It was under this name that he sank in 1884. His title as the largest ship was quickly taken over by the Himalayas of P & O in 1854.

Specifications

Displacement: 3500 tons light

Dimensions: 98m long x 15.2m wide x 6.5m draft.

Propulsion -1 propeller, 1 engine 4-cylinder, 500 hp.

Speed: 10 knots max.

SS Oregon (1883)

Large liner of the prestigious “Alantic line”, 1883. Launched in 1883 for the Guion Line, this transatlantic built in iron and not steel by John Elder, delights the blue ribbon to its competitor Austral, of the same line. 152.8 meters long, 16.5 wide and moving 7400 tons, it was sold to the Cunard in 1884 because of the economic difficulties of its owner.

In 1885, he was requisitioned and served as a reconnaissance ship for the Royal Navy, in the midst of tensions with Russia, and was armed with ten pieces of marine. He then resumed his civil service, but in 1886 paid the price of the lightness of its construction by hitting a ship off Fire Island, and sank slowly, fortunately without loss of life, crews and passengers being collected by the Fulda, a passenger liner. the North Deustcher Lloyd …

Specifications

Displacement: 3466 tons light

Dimensions: 106.7 m long x 12.8 m wide x 9.5 m draft.

Propulsion -1 propeller, 1 engine 4-cylinder, 700 hp.

Speed: 12 knots max.

Crew, passengers:?

SS Britannia (1885)

The Britannia and Victoria were built at Caird & Co, launched in 1887 and the Oceania and Arcadia at Harland & Wolff and launched in 1888 for P & O on its lines to the East and Oceania. The construction of the Britannia was accelerated to participate in the Queen Victoria Jubilee in 1888. So they were all called “Jubilee class”.

Fast, thanks to their triple expansion machines driving a propeller, they loaded 220 + 160 passengers in two classes and the first two were used as fast troop transports in 1894-95 during the Boer War. This test was a success and this practice spread quickly. They were both removed from service in 1909, but the Oceania was still in service in 1912 when it struck a large German three-mast near Beachy Head and sank with 700,000 gold pounds in its holds. The Britannia saw the first world war and was disarmed in 1915.

Specifications

Displacement: 7400 tons light

Dimensions: 152.8 m long x 16.4 m wide x 5 m draft.

Propulsion -1 propeller, 1 engine 4-cylinder, 16 boilers.

Speed: 13 knots max.

S.S. Ophir (1891)

This liner built in Glasgow in 1891 was destined for the line to Australia, operated by the Orient Line. With a modern design, fast and very opulent, it was an offer of choice to this destination. However, being expensive to operate, it was sometimes put to sleep. Used by the Royal Navy as a magazine ship in 1901, then auxiliary ship in 1915 and finally ship-Hospital at the end of the conflict, service provided until 1922, date of its withdrawal and demolition.

Specifications

Displacement: 6525 light tons

Dimensions: 142.1 m long x 15.9 m wide x 5 m draft.

Propulsion -1 propeller, 2 TE 4-cylinder engines, 16 boilers.

Speed: 18 knots max.

Crew, passengers: 280

S.S. Canada (1896)

Built at Harland and Wolff in 1896, the SS Canada was commissioned by the Dominion Line to connect with Montreal and Boston. He served as a troop carrier during the Boer War, and after his 1910 reshuffle again began to convoy troops in 1914-18, before being demolished in 1926. He was judged at the time as the most beautiful ship ever to sail on the Saint Laurent.

Specifications

Displacement: 6800 tons light

Dimensions: 142m long x 16.2m wide x 4.8m draft.

Propulsion -1 propeller, 2 TE 4-cylinder engines, 16 boilers.

Speed: 19 knots max.

S.S. President Grant (1907)

The British Wilson & Furness-Leyland Line could not receive in 1904 the two beautiful ships built at Harland & Wolff in Belfast, they were resold three years after their completion at the Hamburg-America Line. President Grant and President Lincoln were typical of this generation of cargo ships, betrayed by their numerous cargo tows and their singular superstructures designed to multiply the hatches. Both were seized in New York in 1914, with President Lincoln serving as a troop carrier who died under a torpedo in 1918, and the other was exploited until 1951, a fine career for such a ship, but which also shows legendary strength. ships from the famous Belfast shipyards.

Specifications

Displacement: 6500 light tons, 8000 t PC.

Dimensions: 152.5 m long x 17.7 m wide x 5.6 m draft.

Propulsion -2 propellers, 2 TE 4-cylinder engines,? boilers.

Speed: 20 knots max.

Crew, passengers:? – 1020 (including 800 emigrants).

S.S. France (1912)

The Penhoët shipyards of Saint-Nazaire have a long-standing relationship with the CGT (Transatlantic General Company). They produced for her marvelous wonders, able to confront the biggest companies of the world including at the time the unavoidable White Star Line, P & O and Cunard. This luxurious transatlantic boat, launched in 1912, the largest produced by the shipyards, could be measured against Mauretania and Lusitania.

In 1914-18, he was successively auxiliary cruiser, hospital ship and troop transport. It was rebuilt in 1923, passing oil, and demolished in 1935. It was quickly eclipsed by the sublime Normandy, and its name was taken up by the last great liner of tradition, launched in 1962.

Specifications

Travel: 46,332 tonnes GRT (52,310 TPC)

Dimensions: 269.10 m long x 28.2 m wide x 9 m draft (air draft 53 meters).

Propulsion -3 propellers, 2 TE 4-cylinder engines, 29 boilers, 30,000 hp.

Speed: 22 knots cruising, 25 knots max.

Crew, passengers: 900 – 1/2 / 3rd class: 905, 564, 1134

S.S. Homeric (1921)

This liner had a very original destiny: Started just before the war by Schichau of Danzig for the North Deutscher Lloyd, it remained unfinished during the war and the armistice, was transferred to the British government who sold it to the White Star Line , responsible for its completion. It was the largest ship in the world with two propellers.

It was not until 1922 that he sailed for his maiden voyage on the transatlantic line. However in 1923, he was driven to Harland and Wolff to be converted to heating oil. From 1932 he was removed from the transatlantic line and became a cruise ship. He left to scrap in 1936, after only 15 years of service. He embarked 2866 passengers.

Specifications

Displacement: 23 600 t PC

Dimensions: 217 x 23 x 8 m.

Propulsion -2 propellers, 2 TE 4-cylinder engines, 16 boilers, 12,000 hp.

Speed: 23 knots max.

Crew, passengers: 600 – 1826 (including 800 immigrants).

S.S. Empress of Britain (1932)

Chartered by the Canadian Pacific, this large steamer (231.8 meters by 29.6) and weighing 42 350 tons was built by John Brown Shipyard of Clydebank and launched in 1931. It was specially designed for the Atlantic line, taking the blue ribbon in Bremen. But his maiden voyage did not take place to New York but to Quebec.

He was significantly faster on this line than his competitors. However he was also one of the first cruise liner, a new fashion, launched by the Jet-set of the Roaring Twenties. As such, it could work with half of its powertrain. He embarked 1195 passengers including 460 first class, and mobilized in 1939 and assigned to transport Canadian troops, he was torpedoed by a German submarine, then towed by a destroyer, poured for good by the torpedoes of another submarine. Fortunately, her embarked troops had evacuated her.

Specifications

Displacement: 34 350t PC

Dimensions: 236 x 25 x 6.8 m.

Propulsion -2 propellers, 2 TE 4-cylinder engines, 16 boilers, 6000 hp.

Speed: 23 knots max.

Crew, passengers: 500 – 2886.

S.S. United States (1952)

The ‘Big Four’ of the White Star Line -Mark Chirnside

A Man and His Ship: America’s Greatest Naval Architect and His Quest to Build the SS United States by Steven Ujifusa

Crossing on Time: Steam Engines, Fast Ships, and a Journey to the New World by David Macaulay

Oceanic: White Star’s ‘Ship of the Century’ by Mark Chirnside

SS Leviathan: America’s First Superliner by Brent Holt

Queen Elizabeth 2 Manual: An insight into the design, construction and opera – by Haynes (Other primary creator)

Across the Pacific: Liners from Australia and New Zealand to North America – by Peter Plowman

White Empresses: And Other Canadian Pacific Liners of the 1920s & 30s – by William Ncsu Miller

Transatlantic: Samuel Cunard, Isambard Brunel, and the Great Atlantic Steamships – by Stephen Fox

The Golden Age of Ocean Liners – by Lee Server

Last of the Blue Water Liners: Passenger Ships Sailing the Seven Seas – by William H. Miller

RMS Aquitania: The Ship Beautiful by Mark Chirnside

Great Passenger Ships 1930-1940 by William Miller

Cabin Class Rivals: Lafayette & Champlain, Britannic & Georgic and Manhattan & Washington by David L. Williams, Richard P. de Kerbrech

Great Passenger Ships 1950-60 by William Miller

Liners in Battledress: Wartime Camouflage and Colour Schemes for Passenger Ships – David Williams

Paper Models

SS Olympic – Or Papersquare

SS Titanic – Also

SS Britannic – And on shipmodell

Fentens Papermodel – Queen Mary and others

RMS Mauretania on kartonmodellbau.de

LINKS

https://www.cruiselinehistory.com

https://www.ocean-liner-society.com/

https://www.whitestarhistory.com/

https://cherbourg-titanic.com

https://www.cunard.com/

http://www.frenchlines.com/en/

www.theshipslist.com/

http://www.heritage-ships.com/

https://www.maritime-database.com/

http://www.worldshipping.org

https://www.maritimeinfo.org/

3D MODELS

https://www.turbosquid.com/3d-models/3d-model-great-eastern-ship/917944

https://www.turbosquid.com/3d-models/rms-lusitania-3d-max/921298

https://www.turbosquid.com/3d-models/3d-model-original-immigration-ships-1280620

https://www.turbosquid.com/3d-models/3d-original-passenger-steam-ships-model-1414367

https://www.thingiverse.com/thing:3402906

https://hum3d.com/ocean-liner/

https://www.linerdesigns.com/the-process

https://3dwarehouse.sketchup.com/by/Lucasgustaffson

VIDEO: Great Oceans Liners: Speed Machines

Also:

youtube.com/watch?v=4oyNH8TjJ6A

youtube.com/watch?v=npUpZgSebJQ

youtube.com/watch?v=PPwhrra9mjY

youtube.com/watch?v=Er9wOadvvCY

youtube.com/watch?v=tafvJfFmg3Y

youtube.com/watch?v=nt7dbvKsEf8

youtube.com/watch?v=xmBacWD4M4M

youtube.com/watch?v=ma-j-Rm3W9k

youtube.com/watch?v=a9qRb0mp-5s

youtube.com/watch?v=zfMmmJrEE5I

youtube.com/watch?v=hHNTRDEb5NQ

https://archive.org/details/LostLiners2000

youtube.com/watch?v=xhGcGvR4PEc&list=PLGev5DpvwS6V7q0feaAHzmWuUL0LLnHfD

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign