USA (1917-30) T-1 to T-3, AA-1 to AA-3 fleet submersibles

USA (1917-30) T-1 to T-3, AA-1 to AA-3 fleet submersiblesWW1 US submarines:

USS Holland | A class | B class | C class | D class | E class | F class | G class | H class | K class | L class | M class | N class | O class | R class | S class | T classThe T-1 class submarines (previously known AA-1 class) were the first attempt by the USN to build a fleet submersible. It was planned in 1913 already to operate with the new Delaware class, the first “standard battleships”, with a surface speed of 21 knots to act as scouts. It was a radical departure from conventional approaches that saw the submarine as a coastal defence asset with good underwater speed and agility. Only greenlighted in 1917 when construction commenced at Electric Boat in the Massachusetts, they had been designed in a rush, with an existing designed stretched to accomodate five massive New London Ship and Engine Company (NELSECO) diesels, two paired on each propeller, one used only to reload batteries.

When commissioned eventually after nearly six years of contructions they initially showed promised, being capable of reaching 20 knots on trials. However they were plagues by huge structural issues and engine unreliability which shortered their service life down to just three years of service on average. They spent their time in the mothballs before being stricken in 1930 and sold for BU, the example of “how not to do it”. The USN would certainly not abandoned the concept and laid down three more subs, this time with German diesels, and they proved equally frustrating. See the previous article on the Barracudas. #ww2 #usnavy #USN #unitedstatesnavy #submarines #schley

Development

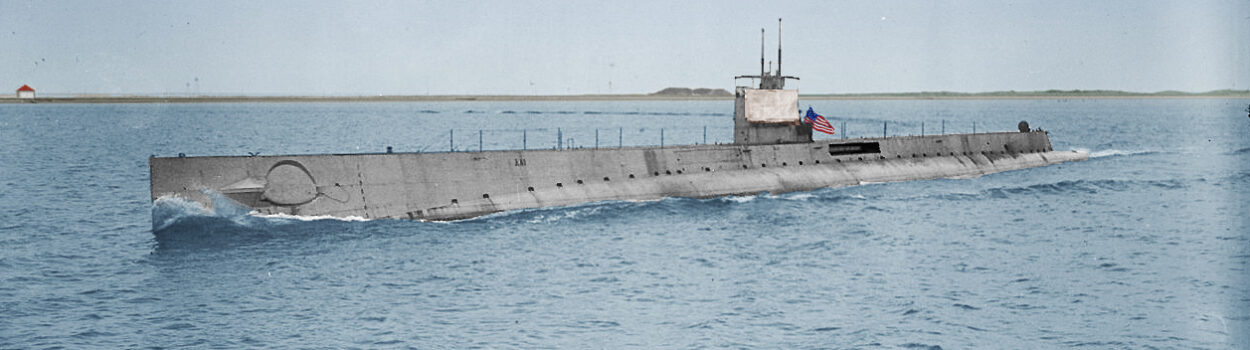

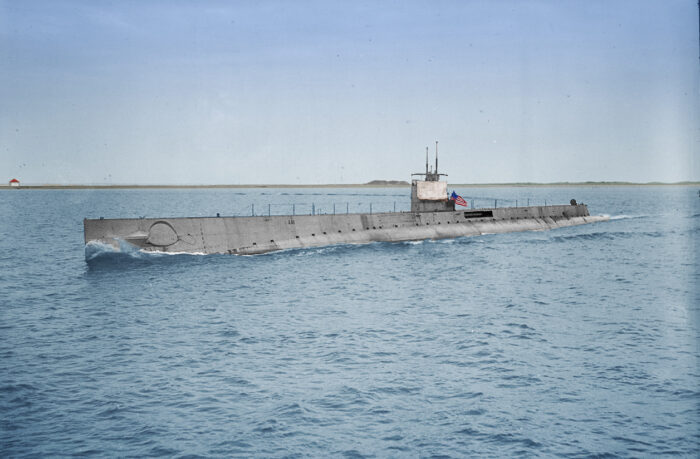

The first USS T-1 (SS-52/SF-1) later named USS SChley, was an AA-1-class submarine which entered after the first world war with the United States Navy. The AA-1 class which only comrised three experimental boats were designed and constructed under a project of the US Admiralty to develop fleet submarines, giving them sea-keeping qualities and endurance for long-range operations acting as submersible scouts for the surface fleet.

From Aide for Naval Operations to CNO Benson

The development of this class of fleet subs arrived just as the USN underwent changes in its command structure. At the head indeed of the department existed a status known as the Aidr for Naval Operations, ancestors of the CNO for general direction in naval construction and maintenance, linked to the secretary of the Navy. The ANO helped in administrative and operational authority over the Navy alongside the secretary of the Navy and bureau chiefs with the General Board holding advisory powers (see later). Critics of the lack of military command authority under the secretary however never succeeded in their reorganization attempts as they were opposed by Congress due to fears of a Prussian-style general staff with an all-powerful Navy secretary. Navy secretary George von Lengerke Meyer under William Howard Taft created the “aides” on 18 November 1909 which lacked command authority but were used as principal advisors to secretary, alsmot working like an XO for the detailed administration of the Navy. Next ANOs were Rear Admiral Richard Wainwright, Rear Admiral Bradley A. Fiske in 1913, which stayed in place under Josephus Daniels and obtained his post was transformed into the CNO.

Meanwhile, the General Board was established by general order 544 (March 13, 1900) by Secretary of the Navy John Davis Long, only recognized by Congress in 1916. It was disbanded in 1951. The General Board had been created after the war with Spain after the need for adequate staff work. Like the ADO and later CNO it possessed no executive functions, and had an advisory council role towards the secretary. These were senior admirals at the end of their careers in no urge thus able to deliberate selflessly and objectively on matters ranging from strategy to ship characteristics. They helped defining the new types of vessels of all sorts in the Navy.

When the post of CNO was created by Daniels, the Board was directed by George Dewey until 1917. Daniels feared that the country was not ready to enter WWI if needed be and wanted to give more authority to the office, asking Richmond P. Hobson, a retired Navy admiral and specialist in legal matters to draft legislation for the new post. The CNO worked well wth the Board but as time passed, the Board earned its own administration making the Board redundant. The genesis of the massive fleet born before the entry int the war by the USN was the result of these discussions between the Board and the CNO, and between him and the Secretary, making the interface with the Congress.

Genesis of the new submarines

Captain William S. Benson was promoted as rear admiral and became the first CNO on 11 May 1915. With good trust with Daniels, confidence grew and so his own authority. Under this guidance in 1916 already, the fleet was in full modernization. New dreadnought were built and soon a debate raged between those who wanted fleet destroyers for the battle fleet and those who rather wanted scout cruisers (especially since cruiser construction stopped in 1907), and a third section, more radical, which advocated for submersibles, having the advantage of staying unspotted. Indeed, scout cruisers and/or destroyers would always be spotted on the horizon, alerting the enemy and potentially conducting the latter to avoid the researched “decisive battle”.

But the genesis of fleet submarines went as far as 1914, years after Holland succeeded in pushing the adoption of submarines to naval strategists. Seeing the possibilities of these, many started to believ they could operate as long range reconnaissance assets regarless of their speed (we would say picket ships today), capable of working in close collaboration with the fleet. It was a radical departure of the traditional notion of the submarine as a coastal defense asset. The brand new concept of “fleet” submarines would obviously needed to be larger, better armed, with a surface speed ultimately setup at 21 knots (39 km/h; 24 mph) to be compatible to the new “standard” battleships defined prewar, such as the Delaware class to start with.

In the summer of 1913, so, Electric Boat’s chief naval architect Lawrence Y. Spear proposed two preliminary designs for consideration for the FY14 Navy program. The project got traction with the Secretary of the Navy at the time, and earned an authorization by the Congress for eight submarines, provided they would “be of a seagoing type to have a surface speed of not less than twenty knots.” This was of course the curcial point for this class, all was linked to it.

Work went on with blueprints between 1914 and 1916, with many proposals back and forth defining the internal arrangement of engines, mostly, the search for the right powerplant, and ending with the afterthoughts, like the armament. Final blueprints being provided and authorized, the first fleet boat of this order of eight was eventually laid down in June 1916.

As a symbolic gesture towards 1911 deceased war hero Winfield Scott Schley of Spanish–American fame she was named USS Schley, but there was confusion as how they should be classified, outside their SS hulll number. At USS Schley, later AA-1 in 1919 and finally T-1 before they were discarded.

Design of the class

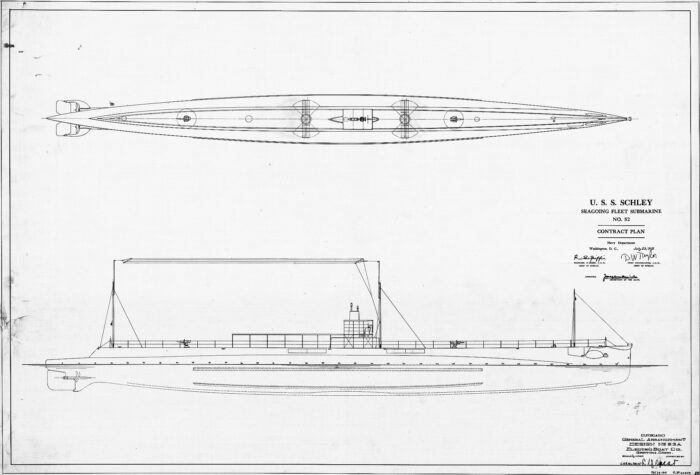

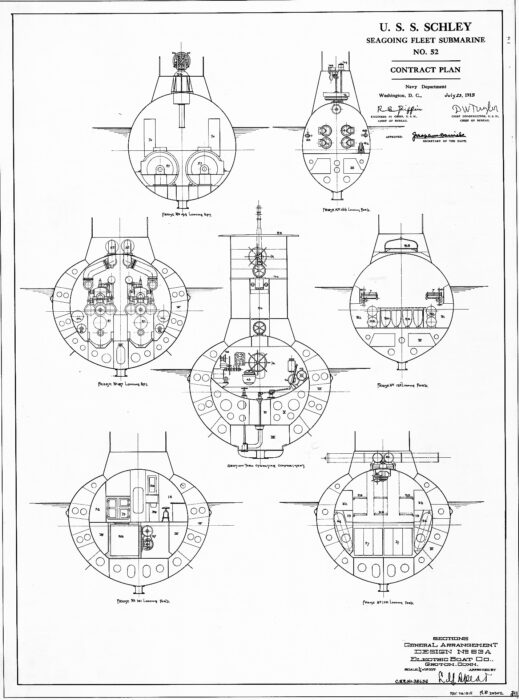

Hull and general design

The ultimate design was a 1,106 tons surfaced boat, 1,486 tons submerged and 270 feet (82 m) which was considerable, making these the largest submersibles ever built in the western hemisphere. Indeed Germany was working on since 1914 even more massive designs, such as the bloclade runner Deutschland, an unarmed sub cargo used as base for more massive oceanic U-Kreuzer. Still in the US, USS Schley was twice as large as any previous U.S. submarine. To expedite the design, Spear expanded an existing partial double hull design cerated for a foreign customer originally, but without thickening the hull plating or strengthen the framework which ultimately made for an awkward tank arrangement. Despite their large size, these fleet subs could only dive to 150 ft (46 m), half their lenght.

Powerplant

To achieve the surface speed the congress and USN wanted at first it was believed to install two 1,000 horsepower (750 kW) diesel engines (unspecified), arranged in tandem on each shaft and add an axial, separate diesel generator only for charging batteries. This way, the three boats authorized in 1915 which later redesignated as AA-1, AA-2 (T-2), and AA-3 (T-3) all manage to reach their design speed of 20 knots (37 km/h; 23 mph).

This engineering plant comprised four New London Ship and Engine Company (NELSECO) 6-EB-19 4-cycle 6-cylinder diesels rated for 1,000 hp (750 kW) each for the tandem pair and, with two Electro Dynamic main electric motors rated for 675 hp (503 kW) each driven by the engines without any transmission or intermediate system.

The submerged power had its own independent powerplant as designed, with a smaller NELSECO 4-cycle 4-cylinder auxiliary diesel generator to charge batteries, two 60-cell Exide models. Thanks to this arrangement, 100% of the power of the main engines could be passed on to the shafts, without loss due to charging batteries at the same time. Unfortunately it was not planned to couple the third diesel to a gearbox and pass on this power to the two shafts, or a third axial shaft for cruise speed and a boost in top speed if needed. This direct drive, 1.0% power and separated batteries charge was quite unique and only possible by the size of these boats, but it was a bit crude.

Indeed while in trial, in order to maintain that 20 knots speed it was ceessary to not push this regime too long (to compare the next fastest US sub at the time in construction, the S class, reached 14 kts). Indeed after a prolongated use, there were torsional vibration problems caused by the stretched structure, and excess vibrations. Indeed to simplify the design it was decided to clutch together these diesels, so it was impossible to perfectly synchronize operation, creating unbalance and these extreme torsions. The NELSECO also suffered from poor reliability in operations.

For all these issues, early service in 1921-22 was plagued by constant breakages and very short periods at sea. From 1923 to 1927, only USS T-3 was taken over to be re-engined, with two now available, (war reparation) German Maschinenfabrik Augsburg Nürnberg AG (MAN) 4-cycle 10-cylinder diesels rated for 2,350 hp (1,750 kW) each. These were those from former incomplete U-Kreuzer. At least they gave some boost in speed to 21.5 knots in trials, but the way they were arranged and structureal problems remains.

Armament

Despiote thjeir large size, these submarines were stretched, not bulkier, and they kept four bow 18 inch (450 mm) torpedo tubes. However given their great size it was decided to give them two twin trainable external torpedo tubes in the deck superstructure, forward and aft of the sail, and usually covered. This idea was popular with French designs as well as adopted by others navies, but it remained unique to these boats in the USN. These could fire broadside only and could not be reloaded. The four tubes forward had 8 spare torpedoes. The four external and four bow tubes were pre-loaded in port.

These large ships were given no consideration for their deck armament at first. It was just to included two 3-inch (76 mm)/23 caliber retractable deck guns in the original design (seen in the blueprints) as a defensive means. They were not intended for preying on trade. But they were never installed.

In August 1918 T-1 while just launched, was experimentally rearmed with a single 4-inch (102 mm)/50 caliber, of course non-retractable gun. However for this, the forward trainable torpedo tube bank was removed and the location was reinforced. The two other boats would remained unarmed. This was merely to test the effects when submerged of a larger gun on drag and top speed. The admiralty wanted to know if this was possible to get a more serious firepower, especially after it was revealed some German “U-Kreuzer” had two massive 15 cm (5.9 inch) deck guns. Most U-Boats in 1918 also had adopted the 105 cm gun as standard. The teste was mostly positive, and thus 4-inch gun became the standard on the S-class submarines, the last batches being launched in 1921 and completed in 1922. The trainable tubes in the end were eliminated also from AA-2 and AA-3 at commission, AA-1 keeping her aft one. She is shown in most photos without her 4-in gun by the way.

3-in/23 Mark 13 (never installed), link on navweaps

4-in/50 Mark 9

Designed in 1910, in service in 1914, unlike the Mark 8 never adopted and the Mark 7 on the Arkansas class BBs, the Mark 9 became the most produced light gun in US inventory, used on the “Flush Deck” series Cassin (D-43), Aylwin (D-47), O’Brien (D-51), Caldwell (D-69), Wickes (D-75) and Clemson (D-186) classes, “S” class subs as well as the interwar Shark (SS-174), Perch (SS-176), Salmon (SS-180) and Balao (SS-285 to SS-291) classes, but also armed yachts, patrol gunboats, Eagle boats and auxiliaries as well as the Gato class (SS-212) when refitted.

Only fitted for tests on USS T1. More

⚙ specifications 4-in/50 Mark 9 |

|

| Weight | 2.725 tons (2.769 mt) |

| Barrel lenght | 206.5 in (5.2496 m) |

| Elevation/Traverse | -15 / +20 degrees, 150° training from axis |

| Loading system | Smith-Asbury side swing breech, Welin block, 27.5 in (70 cm) recoil |

| Muzzle velocity | 2,900 fps (884 mps) |

| Range | 15,920 yd (14,560 m) at 20° |

| Guidance | optical |

| Crew | 6-8 |

| Round | 64.75 lbs.(29.4 kg) |

| Rate of Fire | 9 rpm |

Torpedo Tubes

The Mark 10 were the last torpedo designed by Bliss, manufactured by the Naval Torpedo Station at Newport. They were used by the AA-1 class presumably as well as all “S” class submarines. Even when the latter saw service in WW2, they kept these models, believed to be more trustworthy than the Mark 14.

⚙ specifications 21″ (53.3 cm) Mark 10 mod 3 |

|

| Weight | 2,215 lbs. (1,005 kg) |

| Dimensions | 183 in (4.953 m) |

| Propulsion | Wet-heater |

| Range/speed setting | 3,500 yards (3,200 m) / 36 knots |

| Warhead | 497 lbs. (225 kg) TNT or 485 lbs. (220 kg) Torpex |

| Guidance | Mark 13 Mod 1 gyro |

⚙ AA specifications 1917 |

|

| Displacement | 1,107 tons (1,125 t) surfaced, 1,482 tons (1,506 t) submerged |

| Dimensions | 268 ft 9 in x 22 ft 10 in x 14 ft 2 in (81.92 x 6.96 x 4.32 m) |

| Propulsion | 4x NELSECO diesels (4,000 hp), 2 Electro Dynamic main motors 1350hp, 1 NELSECO auxiliary diesel |

| Speed | 20 knots (37 km/h; 23 mph) surfaced, 10.5 knots (19.4 km/h; 12.1 mph) submerged |

| Range | 3,000 nmi (5,600 km; 3,500 mi) at 14 kn (26 km/h; 16 mph) |

| Armament | 6x 18 in TTs (4 bow, 2 ext. 16 torpedoes), 2x 3 in/23 deck gun |

| Crew | 4 officers, 5 chief petty officers, 45 enlisted |

Career of the AA class

They were launched and completed with quite a gap. USS Schley was the only one actually launched during WWI, un July, laid down a ful year before her sisters to have trials results to modify the two others. She was commissioned however a full years and two months after the war ended in January 1920, and at this stage her two sisters had been launched in September and May 1919, both will be completed even later in December (for T-3) 1920 and in January 1922, so six years after her construction started, for USS T-2.

All three boats were based out of Hampton Roads with Submarine Division 15, Atlantic Fleet for fleet training and maneuvers.

On July 17, 1920, all three became “Fleet Submarines” with the hull numbers SF-1, SF-2, and SF-3, changed from “AA” to “T” on September 22, 1920 and thus only AA-1 became operational under this name, not her sisters. In all literrature they became the T-series when accepted by the Navy. But they served onky for a short time, plagued by multiple issues caused by their rushed design and so they were all decommissioned by 1923 (just one year for T-3 !) and as it was hard to “sell” three ships broken up after one to three years of service, they were placed in storage at Philadelphia, in Pennsylvania for a time they could be drydocked, gutted and equpped with better diesels and reinforced. But between 1925 and 1927 on T-3 returned into uncommissioned service to test German-built MAN diesels as seen above, and the returned to Philadelphia. All three passed the 8 years mark in storage when stricken on 19 September 1930, sold for scrap on 20 November 1930. In the end, they were probably the worst submarine ever built for the USN up to that point. In 1922 plans to revive the concept of fleet submarines, with some German tech influence, gave the three Barracuda class to replace them (equally bad) and later the enormous USS Argonaut and Narwhal class.

Their legacy was technical. How to not just stretch and existing hull and use such machinery arrangement, as well as these diesels.

USS Schley (AA-1)

USS Schley (AA-1)

On August 23, 1917 USS Schley prior to launch was renamed AA-1 to free the name for a new destroyer. On 17 July 1920 when being fitted-out, she was designated SF-1. On 20 September, she was renamed T-1 in the combo T-1 (SF-1). Her hull number was SS 52. She emerged from Fore River Shipbuilding Co. in Quincy, Massachusetts, the first of three sisters by Electric Boat Co. of New York. When commissioned on 30 January 1920 she was under Command of Lt. James Parker, Jr.

She spent just three years in service, homeported all this time at Hampton Roads, training crews, taking part in tactical maneuvers along the east coast and with the Atlantic Fleet, part of Submarine Division 15. Design flaws caused by initial shortcuts taken in design proved too much when combined with the constant issues of her propulsion plant.

On 5 December 1922, she was decommissioned, laid up at the Submarine Base in Hampton Roads and later in Philadelphia. After eight years she was strickenon 19 September 1930 and broken up, after being sold for scrap on 20 November 1930.

USS AA-2 (T2)

USS AA-2 (T2)

Laid down as USS AA-2 on 31 May 1917 on the same yard in Quincy in Massachusetts, she was launched on 6 September 1919, beame SF-2 on 17 July 1920, then T-2 on 22 September 1920, commissoned at last at Boston Navy Yard on 7 January 1922, after six years in construction and fixes… and the shortedt service life of any USN submarine to date.

T-2 in fact was the commissioned. She served for 18 months to demonstrate the concept of long-range scouting and reconnaissance on behalf of the surface fleet. She was administratively attached to Submarine Division 15 (SubDiv 15), between training and maneuvers as part of the the Atlantic Fleet along the East coast. No details are given if she sailed to the Carribean or Newfoundland but given their poor reliability records and issues this was dubious at best. By the fall of 1922, the Navy had just enough. She was decommissioned on 16 July 1923 at Hampton Roads SubBase in Virginia, and was placed in reserve, later moved to Philadelphia reserve, spending seven years of inactivity until stricken on 19 September 1930. She was sold for scrap on 20 November 1930 and broken up.

USS AA-3 (T3)

USS AA-3 (T3)

USS AA-3 was laid down on 21 May 1917 at Fore River like her sisters, launched on 24 May 1919, redesignated SF-3 on 17 July 1920, then T-3 on 22 September 1920, commissioned at last on 7 December 1920 at Boston Navy Yard. Like her sister was life was fairly short. She joined her sister USS T-1 already training in Submarine Division 15 with the Atlantic Fleet. Later they were joined by USS T-2 and they multiplied maneuvers with the Atlantic Fleet until the fall of 1922. It was made abundantly clear they were not ready for service and neede to be completelty rebuilt. But with thes cash-stricken years, all three instead were sent to the reserve fleet, T-3 beng the first, until stricken after six years inactive, and two years testing German diesels. She was decommissioned on 11 November 1922 at Hampton Roads, berthed at the submarine base, moved to Philadelphia before decision was taken to modify her to see if it was practicable to refit all three with the advantage of available diesels, on the cheap.

Both photos: An official visit of Wilbur and the house of Naval Affairs staff visiting USS T-3 in the Navy Yard on 30 December 1925.

T-3 “active service” was thus prolongated after she was modified. But the idea of testing German diesel engines floated around in Navy circles from much longer. T-1 in fact had been at least designed to procure such diesels, but funds prevented the sale. In 1925 budget allowed to modify T-3. Un-mothballed on 1 October 1925, T-3 she returned in service at Philadelphia and for 21 months, tested her newly installed 3,000 horsepower (2,200 kW) M.A.N. diesel engines on behalf of the Bureau of Engineering. it was also to establish the merits of such engines. This choice was also bade for the Barracuda class in 192. Early summer 1927, her captain announced she had completed tests and by 14 July 1927, she was decommissioned at Philadelphia. Indeed, although the new diesels at least solved the powerplant issues, structural problems remains. There are few records about how much these trials were successful and the speed gain, and if it could be maintained. After 3 years of inactivity she was stricken on 19 September 1930 and broken up, sold for scrap on 20 November 1930.

Read More/Src

Books

Alden, John D., CDR U.S. Navy (Retired), The Fleet Submarine in the U.S. Navy A Design and Construction History NIP

Friedman, Norman “US Submarines through 1945: An Illustrated Design History” NIP

Gardiner, Robert, Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships 1906–1921, Conway, Page 129.

Silverstone, Paul H., U.S. Warships of World War I (Ian Allan, 1970)

Links

pigboats.com/index.php?title=T-class

navsource.org/archives/08/04idx.htm

navsource.org

navypedia.org/

en.wikipedia.org AA-1-class_submarine

en.wikipedia.org USS_T-1_(SS-52)

Model Kits

None found

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign