RN (1875-79, service until 1905-19): Iris, Mercury

RN (1875-79, service until 1905-19): Iris, MercuryWW1 RN Cruisers

Blake class | Edgar class | Powerful class | Diadem class | Cressy class | Drake class | Monmouth class | Devonshire class | Duke of Edinburgh class | Warrior class | Minotaur classIris class | Leander class | Mersey class | Marathon class | Apollo class | Astraea class | Eclipse class | Arrogant class | Highflyer class

Pearl class | Pelorus class | Gem class | Forward class | Boadicea class | Blonde class | Active class | Bristol class | Weymouth class | Chatham class | Birmingham class | Birkenhead class | Arethusa class | Caroline class | Calliope class | Cambrian class | Centaur class | Caledon class | Ceres class | Carlisle class | Danae class | Cavendish class | Emerald class

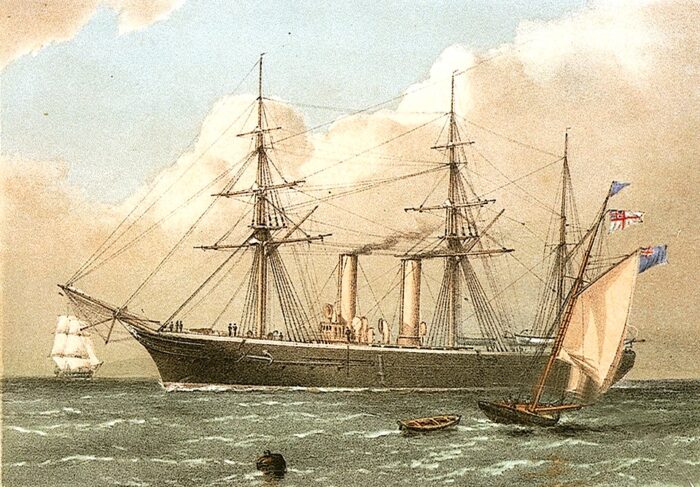

The Iris class Cruiser were an important milestone in the development of the type in the Royal Navy. Unlike contemporary masted vessels called as “armoured cruisers” such as the HMS Shannon and Nelson class, close to ironclads than true cruisers, the Iris class were the first all-steel warships initially classed as “despatch vessels”. These pioneers were later re-rated as 2nd class protected cruisers, but they were the first of this type in the Royal Navy. Completed in 1879, Iris was active until sold in 1905 and Mercury in 1914 (BU 1919).

Development

The mid-1850s was a very peculiar time for the Royal Navy, with radical transformations that completely changed its assets over twenty years, from all wooden built sailing ships and Nelsonian tradition, to an iron and steel turret era of mixed or all-steam warships. As the Crimean war started in 1853, the RN of course had numerous steamships, but they were rarely placed in important military roles. The fleet was still one of large frigates and ships of the line, up to five ranks. There was a race started with France for the conversion of existing sailing warships to steam, then construction of new ones, and then the transition from 1859 to ironclads. But outside capital ships, the real muscle of the Empire and its Navy overseas was made of dependable iron frigates, screw corvettes, and then screw sloops, all composite. The hull might be made partly or totally in Iron, but many internals were still in wood, as the hull backup.

The birth of the “cruiser” was done in an incremental way in the 1870s, well before the term even was used in official documentation. Depending of their protection, there was a triple lineage, of armoured, protected, and unprotected cruisers. Most authors tends to point at HMS Shannon as the start of the armoured cruiser lineage, while the unprotected ones started with 1880s Surprise class despatch vessels (3rd class in the 1900s). Another despatch vessel was generally associated with the birth of the protected cruiser in Britain, the Iris class.

These were designed as “dispatch vessels” by famous naval architect William White, under the direction of Nathaniel Barnaby, Director of Naval Construction (DNC) at the time. They were much later in the 1890s redesignated as second-class protected cruisers. So what is a “despatch vessel”. It was a generally accepted type of small warship, generally light and fast, always steam powered, in order to provide either internal communication in a fleet, or between fleets, or to shore. The idea was that in 1855 still, a large portion of the battle fleet was still sail-powered, with steam as an afterthought. Sure, they could communicate via signal flags or smoke, but for detailed orders, it was necessary to send a fast ship for that mission. Before the 1830s and the apparition of the first steam ships usable for this mission, it was given to over-rigged, ultra-fast and nimble cutters, bricks and schooners.

The core idea with the design, also built by France, Germany and Italy post-1860 (the term “aviso” was used by all three), was to have a steam ship on which the available power made it attractive for a very fast vessel, and the sail rigging almost secondary, used for long crossing for A to B. The Iris class were not the last modern British dispatch vessels. The Surprise class ten years later was another attempt.

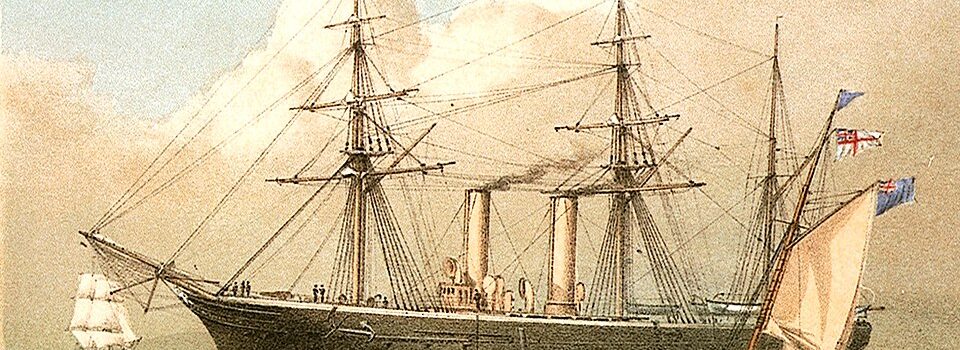

But under the White era, the Iris class were the first to mix modern solution, an all-steel hull for strength, fines lines inherited from the best clippers and frigates, married to a very powerful machinery for ships of that size. The combination was capable of giving them at least 17 knots, whereas the bulk of the fleet was limited to 14 knots at best. They became the first “cruisers” after being redesignated as 2nd class (protected) cruisers retrospectively but paved the way for the first true modern British cruisers, the Leander class, which got rid of the rigging. Iris and Mercury were both ordered to Pembroke Naval Dockyard. Iris was laid down first on 10 November 1875 and completed in April 1879, her sister laid down on 16 March 1876 and completed later in September 1879.

Design of the class

Hull and general design

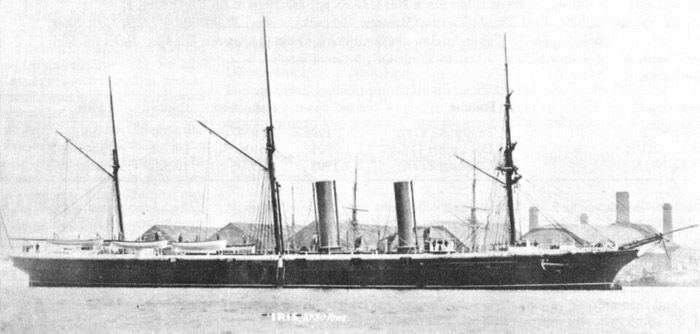

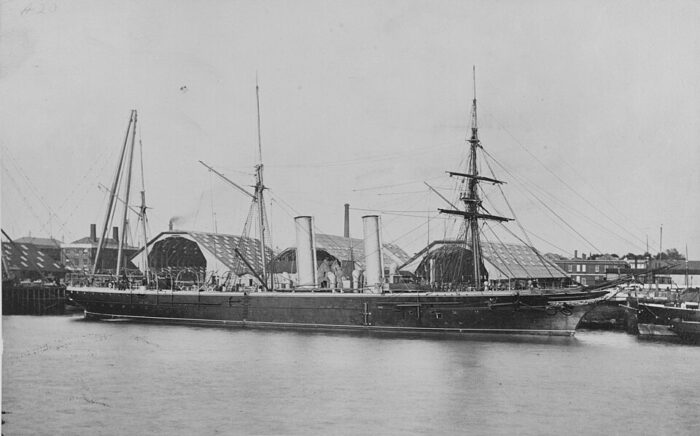

The Iris class innovated on many points, and in addition to their steel hull, they relied for protection on an intensive sub-division with coal bunkers, but still no embryonic protective deck, and they had a limited endurance. The only visible difference both sister was Iris’ clipper bow, making her longer overall than Mercury with her straight stem (the bowsprit was not counted). Iris measured indeed 331 feet 6 inches (101 m) long overall. Mercury measured 315 feet (96 m) long.

The beam was the same 46 feet (14 m), and draught of 20 feet 6 inches (6.2 m). Displacement was 3,730 long tons (3,790 t) at normal load and for their dimensions, it was superior to the norms at the time, as they were made entirely of steel, between the framing and outer plating. The crew amounted to 275 officers and ratings.

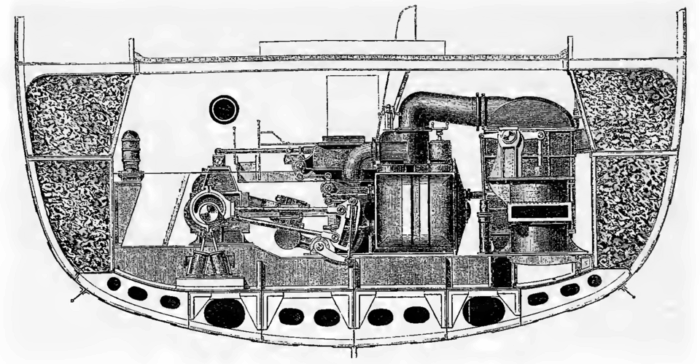

Powerplant

The Iris class was designed to be fast. She had two horizontal four-cylinder manufactured by Maudslay Sons and Field. These compound-expansion steam engines were configured with two high-pressure cylinders, each with a bore of 41 inches (100 cm) plus two low-pressure cylinders 75 inches (190 cm) in diameter. These cylinders had a 36-inch (91 cm) stroke and the engines drove one propeller shaft, using steam from eight oval, four cyl. boilers, all with a working pressure of 65 psi (448 kPa; 5 kgf/cm2). The engines were designed to produce 6,000 indicated horsepower (4,500 kW) overall for a top speed of 17 knots (31 km/h; 20 mph). But as planned by the manufacturer, which deliberately gave conservative fugures, the output and top speed were handily exceeded.

Iris reached at first 16.6 knots (30.7 km/h; 19.1 mph) from 7,086 ihp (5,284 kW) in her first sea trials, a disappointment soon attibuted to propellers. When new propellers were fitted she managed to reach 17.89 knots (33.13 km/h; 20.59 mph) from 7,330 ihp (5,470 kW). Her sister HMS Mercury became the world’s fastest warship thanks at 18.57 knots (34.39 km/h; 21.37 mph) from 7,735 ihp (5,768 kW). Both carried however only 780 long tons (793 t) of coal, to cross 4,400–4,950 nautical miles (8,150–9,170 km; 5,060–5,700 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph). Their sailing rig was a barque sailing rig, which was removed after a few years.

Protection

As the first British “protected” cruisers, the Iris class was not armoured. But they had still an extensive internal subdivision, with many compartments filled with coal, offering some protection against flooding. This was doubled by a 150-foot-long (45.7 m) double bottom, all over the propulsion machinery compartments.

Armament

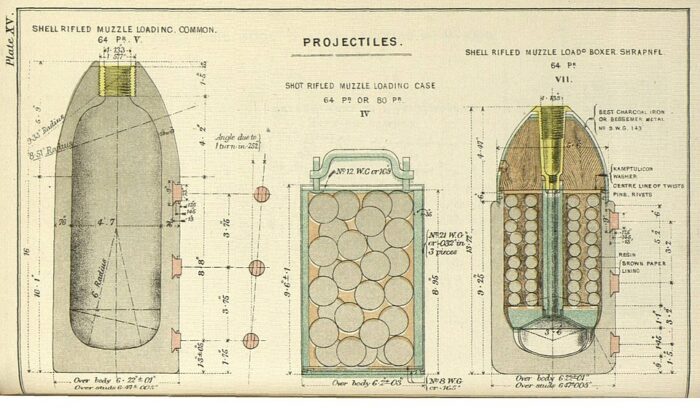

The original armament as planned was of ten 64-pounder (6.3-inch (160 mm)) rifled muzzle-loading (RML) guns, plus eight on the main deck, the remaining pair on the upper deck on pivot mounts, as to act chase guns fore and aft.

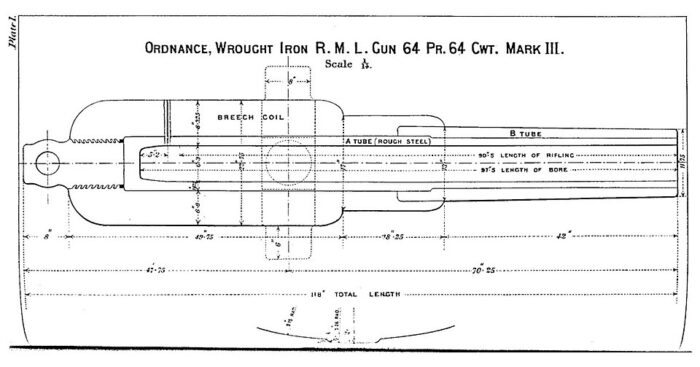

64-pounder (6.3-inch) RML

The Woolwich Arsenal RML 64-pounder (64 cwt gun) was a Rifled, Muzzle Loading (RML) naval, field or fortification artillery gun. Its projectile weighted approximately 64 pounds (29 kg), and it was called “64 cwt” in weight rounded to make a difference with the “64-pounder” guns of the time. They were manufactured to fire remaining stocks of spherical shells from the obsolete 32 pounder guns if needed but the Iris class were provided with shells. They likely still had the Mark III (adopted in 1867), which were converted in 1867–April 1871 with wrought-iron inner “A” tubes and wrought-iron coils. But more elikely they had the more recent versions converted after April 1871, built with toughened mild steel “A” tubes.

Remaining guns with iron tubes went to the RN indeed. They had a 3 grooves, uniform twist, 1 turn in 40 calibres over 252 in or 640 cm. The “common shell” used against ships and buildings weighed 57.4 pounds (26.0 kg), empty with a bursting charge of 7.1 pounds (3.2 kg) or Shrapnel (66.6 pounds/30.2 kg) with 234 metal balls inside. Due to their low muzzle velocity of 1,252 feet per second (382 m/s) versus 1390 fps for the steel tubes, their penetrative power was close to nil, but they had a useful range of 5,000 yards (4,600 m).

Iris class specifications |

|

| Displacement | 3,730 long tons (3,790 t) |

| Dimensions | 315/331 ft 6 in x 46 x 20 ft 6 in (96/101 x 14 x 6.2m) |

| Propulsion | 2 shafts compound-esp. steam engines, 12 boilers; 6,000 ihp (4,500 kW) |

| Speed | 17 knots (31 km/h; 20 mph) |

| Range | 4,400–4,950 nmi (8,150–9,170 km; 5,060–5,700 mi) at 10 knots |

| Armament | 10× 64 pdr RPM |

| Armor | None but ASW compartimentation |

| Crew | 275 |

The Iris class service

HMS Iris (1877)

HMS Iris (1877)

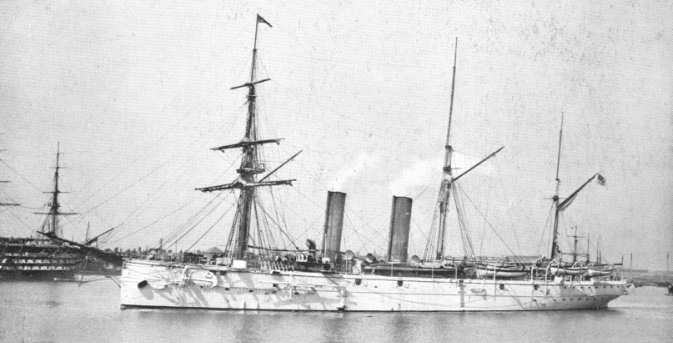

Iris was laid down at Pembroke Dockyard on 10 November 1875, launched on 12 April 1877 and completed in April 1879 at Pembroke. She saw service in the Mediterranean Fleet, from 1879 to 1887, taking part notably in the war in Egypt. She entered the Portsmouth Reserve from 1887 to 1903. She became a tender to HMS St Vincent from 1903 to 1904 and was sold for demolition by 11 July 1905. She was as advanced as soon obsolete and her career was dull in the “Pax Victoriana”.

![]()

HMS Iris during the war in Egypt

HMS Mercury (1878)

HMS Mercury (1878)

HMS Mercury was laid down at Pembroke on 16 March 1876, launched on 17 April 1878 and completed in September 1879. She entered straight away the Portsmouth Reserve from 1879 to 1890. She then sent to the China station, remaining there from 1890 to 1895. Back home, she was versed again the Portsmouth Reserve and stayed there from 1895 to 1903. She became a navigation school ship for navigating officers from 1903 to 1905. She became a submarine depot ship at Portsmouth, and remained in this post from 1906 to 1913. Her sister was sold, but Mercury was in the Harwich force by 1913. There were plans to rename her “Columbine” in 1912, and keep her as an utility vessels, but instead she was hulked at Rosyth in 1914. She remained as a port depot ship, with HMS Columbine, former HMS Wild Swan. She was then towed to Chatham during the war and remained there as an accommodation vessel from 7 January 1918, paid off in March 1919. She was eventually sold for scrap at the Forth Shipbreaking Com. Bo’ness, 9 July 1919.

Upgrades: In 1880, Iris had her eight 32 pdr or 160/16mm guns replaced by four four 6 inches or 6-in(152mm)/26 BL Mk II, and four 5-in(127mm)/25 BL guns.

In 1886-1887, both were entirely rearmed with thirteen 5-in/25 BL and four 47mm/40 (3pdrà Hotchkiss Mk I guns and four 356mm (15 in) torpedoes carrier (no tubes).

Conway’s take on the Type

Britain’s first warships to be constructed of steel, these two vessels were designed for high speed at the expense of protection and armament. Although classified as despatch vessels they originated the development of later cruiser designs and in the late 1880s thev were reclassified as 2nd class cruisers. Jris was the first to run trials and considerably exceeded the designed power at 7,086 ihp although speed was only 16.6 kts. However, after fitting new propellers, she achieved a remarkable 17.89 kts with 7,330 ihp while Mercury, benefiting from the experience gained with her sister, made 18.57 kts with 7,735 ihp, making her the fastest warship in existence at the time of her completion.

Each ship had two engine rooms with the after engine driving the port shaft and the forward engine the starboard shaft. The boilers were equally disposed in two boiler rooms and each could be operated independently in the event of damage to the other. As no armour was fitted, the ships were extensively subdivided with a double bottom over the full length of the machinery compartments (150ft), while some protection was afforded by the coal bunkers which were arranged in wing compartments abreast the machinery extending from the main deck to the hold. The ships completed with a light barque rig but after a few years in commission the yards were removed. The full coal stowage of 780ft provided an endurance of 6000nm at 10kts or about 2000nm at full speed; nominal coal stowage was 500t.

The original armament consisted of 10-64pdr of which 4 were mounted on each side of the main deck and one each on the forecastle and poop. Shortly after completion Jris had her

main deck guns replaced by 4-6in and 4-5in BLRs and both ships were rearmed during 1886/87 with 13-5in BLRs, ten on the main deck, two on the forecastle and one on the poop.

The two were very similar in appearance except that Jris had a clipper bow while Mercury had a straight stem. Mercury became a submarine depot ship in 1905 and served as a hulk at Chatham 1914-18.

Read More/Src

Books

Gardiner, Robert, ed. (1992). Steam, Steel and Shellfire: The Steam Warship 1815–1905.

Lyon, David & Winfield, Rif (2004). The Sail & Steam Navy List: All the Ships of the Royal Navy 1815–1889. Chatham Publishing.

Morris, Douglas (1987). Cruisers of the Royal and Commonwealth Navies. Liskeard: Maritime Books.

Roberts, John (1979). “Great Britain”. In Gardiner, Robert (ed.). Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships 1860–1905.

Links

https://www.navypedia.org/ships/uk/brit_cr_iris.htm

https://www.battleships-cruisers.co.uk/iris_class.htm

http://www.dreadnoughtproject.org/tfs/index.php/Iris_Class_Cruiser_(1877)

https://www.britishempire.co.uk/forces/navyships/cruisers/hmsiris.htm

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Iris-class_cruiser

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign