The oldest Chinese protected cruisers – The Chao Yung class was part of the rearmament naval program destined to the Beiyang fleet. They were designed by Vickers architect and built at the Mitchell Yard, and completed with British armament all around. Displacement less than a destroyer in WW1, these were typical of the “cruisers” at the end of the 1870s, basically enlarged armored gunboats. With 16.5 knots this ship was just able to follow ironclads of the time. The class comprised two cruisers launched in 1880 and 1881, both sunk 15 years later during the first sino-Japanese war, at the battle of Yalu river in 1894.

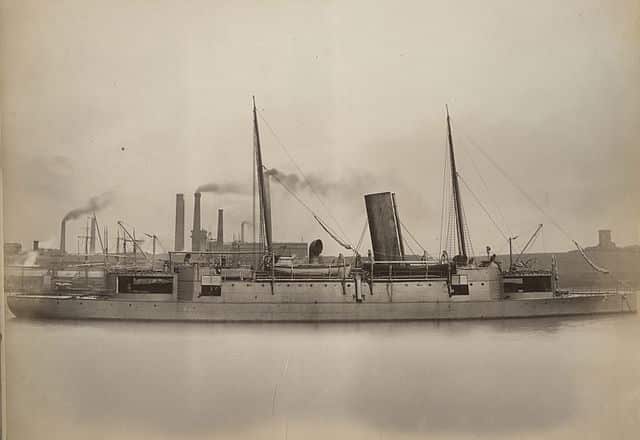

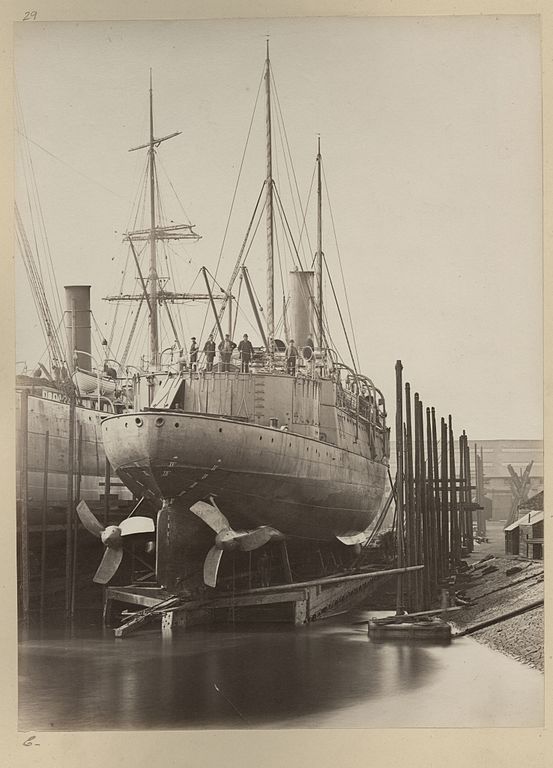

The Chao Yung as completed at Mitchell NyD, in July 1881.

Order context: Ambitions for the Beiyang fleet

The term of “Chinese Navy” is ill-adapted to describe the Imperial Chinese Navy at the end of the XIXth century. There were provincial navies, not unlike the northern, central and southern navies of the PLAN today, but developed of the completely independent way, both in ships orders and command. They were under orders of the local governor as well, and so was the most powerful of these three provincial fleet: The Beiyang fleet, or “northern fleet”, closest to Beijing and the Imperial City, Korea and Japan, a relatively “hot” area, while the Nanyang fleet (or southern fleet) was focused in Western regional ambitions, like the British and French navies.

The term of “Chinese Navy” is ill-adapted to describe the Imperial Chinese Navy at the end of the XIXth century. There were provincial navies, not unlike the northern, central and southern navies of the PLAN today, but developed of the completely independent way, both in ships orders and command. They were under orders of the local governor as well, and so was the most powerful of these three provincial fleet: The Beiyang fleet, or “northern fleet”, closest to Beijing and the Imperial City, Korea and Japan, a relatively “hot” area, while the Nanyang fleet (or southern fleet) was focused in Western regional ambitions, like the British and French navies.

The Beiyang fleet at anchor

The best example of this independence was the fact the the Beiyang Fleet took good care of staying out of range of Admiral Amédée Courbet’s Far East Squadron during the Sino-French War (August 1884 – April 1885). This would have been unthinkable any modern C-in-C, and weighted heavily when the Beiyang Fleet had to face the Japanese in 1894, as the reconstructed Nanyang fleet did nothing to support her. Also, Admiral Ding Ruchang at the head of the Beiyang fleet withdrew his ships from Che-foo to Pei-ho to protect them from the French of admiral Sébastien Lespès, commander of the Far East naval division and remained there idle until the end of the Sino-French War.

Anyway, the northern fleet was the strongest and largest of all Chinese regional navies, by far. There was a real will to develop it in the late 1870s and a swarm of orders saw a rapid growth, to British and German yards. The trump card of this fleet was its pair of ironclad, the Dingyuan class, and in 1879 were ordered two protected cruisers in UK (ChaoYung class), one in Germany by 1882 (Chi Yuan), two more in UK by 1885 (Chih Yuan), two German armoured cruisers (King Yuan) in 1886, the Ping Yuen in 1887, and some gunboats. The first class ordered therefore was typical of products designed in Great Britain for export at the time. Relatively fast as they almost reach 17 knots and heavily armed for their small displacement, these protected cruisers had a recent innovation, the protective turtleback armoured deck, placed just at the level of the waterline, protecting the machinery. This first pair of cruisers ordered in 1879 was the Chao Yung class (or Chaoyong).

Chinese diplomat Li Hongzhang was made aware of Rendel’s designs, and following the start of the construction on Arturo Prat, an order was placed on behalf of the Imperial Chinese Navy for two ships of the same type. Chaoyong was laid down on 15 January 1880, and launched on 4 November. She was subsequently worked up, and was announced as completed on 15 July, a day after her sister ship, Yangwei. They were both completed ahead of Arturo Prat, who instead would enter service as the Imperial Japanese Navy’s Tsukushi after Chile cancelled the order following the end of the War of the Pacific”

Design of the Chaoyong class

Rendel’s cruiser Arturo Prat for Chile (launched August 1880), later resold to Japan before completion as Tsukushi, and classed as a gunboat.

The Chaoyong class was the brainchild of British naval architect Sir George Wightwick Rendel. It was branded as an example of a low-cost cruiser, able to fight larger ironclads. Experts later saw this small cruiser as an intermediate concept between the Royal Navy distant stations colonial flat-iron gunboats and home fleet protected cruisers. On paper indeed, her small size and higher speed made her more agile and difficult to hit, helped by a low freeboard, while her slightly lighter but higher muzzle velocity main battery were well suited to “dance around” ironclads. But Chaoyong was not originally intended for China. It was not a private venture either, but she preceded by a ship ordered by Chile at first. Her design was directly inspired indeed by the Chilean Arturo Prat, later repurchased by Japan, but Rendel’s changed on the design were significant:

The Chaoyong class was the brainchild of British naval architect Sir George Wightwick Rendel. It was branded as an example of a low-cost cruiser, able to fight larger ironclads. Experts later saw this small cruiser as an intermediate concept between the Royal Navy distant stations colonial flat-iron gunboats and home fleet protected cruisers. On paper indeed, her small size and higher speed made her more agile and difficult to hit, helped by a low freeboard, while her slightly lighter but higher muzzle velocity main battery were well suited to “dance around” ironclads. But Chaoyong was not originally intended for China. It was not a private venture either, but she preceded by a ship ordered by Chile at first. Her design was directly inspired indeed by the Chilean Arturo Prat, later repurchased by Japan, but Rendel’s changed on the design were significant:

-Increased output with more steam boilers, from four to six.

-Slightly increased draft (disp. 1,380 vs 1,350 long tons)

-Modified armament: No torpedo tubes, but many light guns (depending on the sources)

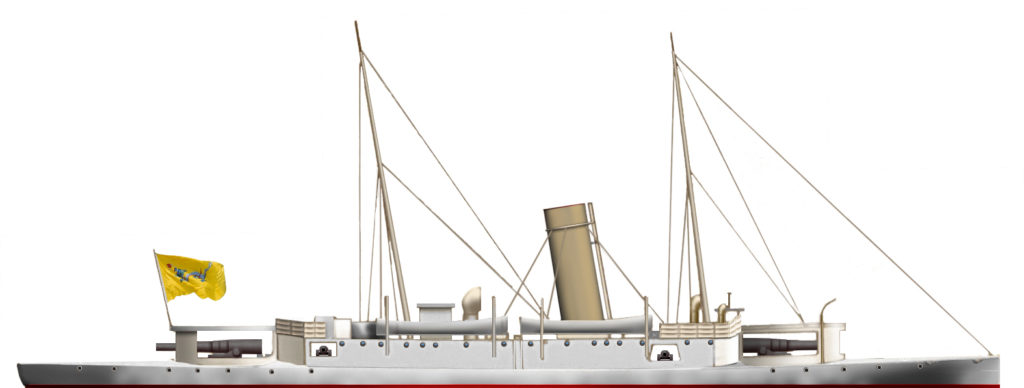

Hull

The design was approved by the Chinese commission and Chaoyong was later followed by a sister ship, Yangwei, which shared the same design, and was also built by the same yard of Charles Mitchell on the River Tyne, near Newcastle Upon Tyne. Mitchell worked with Rendel on several designs which proved popular worldwide. As designed, the Chaoyang was 220 feet or 67 m (210 ft/64 m for Conways) in length overall with a beam of 32 feets (9.75 m) and average draft from 15 to 15.5 feets (4.57-4.7 m). They were compact ship, rather large with a width-to-lenght ratio of 1/6, a single smokestack, and two masts fitted for rigging, in that case a schooner sail plan. They also had a number of technical innovations, notably an hydraulic steering system, and electrical lighting all around. The crew comprised in peacetime 140 officers and ratings.

powerplant

They were propelled by two HCR or reciprocating steam engine, mater on two shafts, and as said above, fed by the steam produced in (four for Conways) six cylindrical boilers. Both cruisers however diverged in some details: The power output of their reciprocating engines was not the same, Yangwei having an output of 2,580 indicated horsepower (1,920 kilowatts), while Chaoyong’s revendicated 2,677 ihp (1,996 kW). Nominal power (also for Conways) was to be 2,287 ihp but this was the same as the Arturo Prat, so possible confusion here. Yangwei was able to achieve 16 knots (30 km/h; 18 mph) and Chaoyong 16.8 knots (31.1 km/h; 19.3 mph) for a contracted, nominal top speed of 16.5 knots.

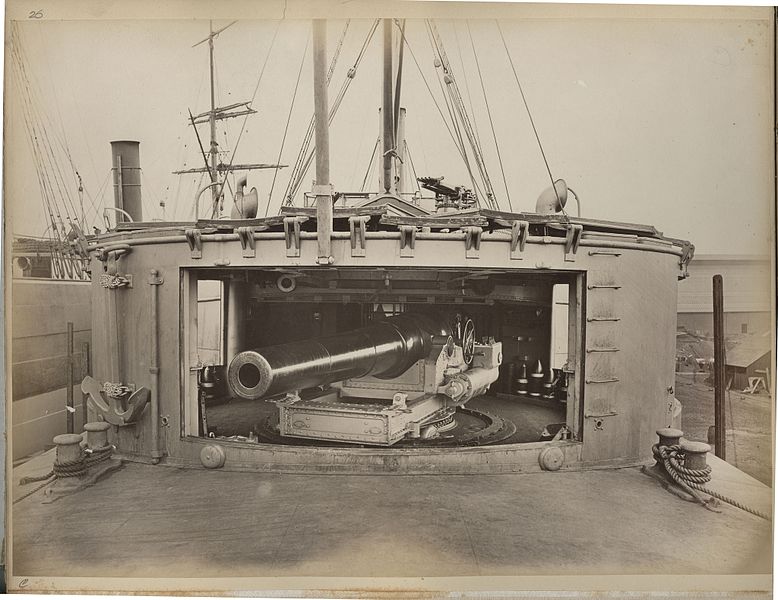

The main battery deck of the cruiser Yang Wei

Protection

The ships were entirely constructed with 0.75 inches (1.9 cm) steel plating, with internal waterproof bulkheads 3.5 ft (1.1 m) below the waterline and a reinforced prow for ramming purposed. Her armoured deck was only 0.27 in thick (7 mm), but this was vertical, so shells were likely to bounce above, in near-flat trajectories of the time, and the “turrets” in which the main guns were located had walls of 1 inch (27 mm). These were not turrets but rather revolving turntables protected by walls making the “turret-like” arrangement. There was also a small conning tower at the front, protected by half an inch of armour, or 12.7 mm.

Profile of the Chaoyong class as built (Conways) in it’s “colonial” livery

Armament

Main armament:

Two breech-loading Armstrong Whitworth 10 inches (254 mm) rifled cannons were provided. One was placed forward and one aft, mounted in stationary gun shields, installed for weather proofing reasons. They restricted the angle of fire to four openings for traverse, but also elevation. The guns themselves were mounted on rotative tables. The types of shells, numbers, or characteristics are unknown.

We will tray to extrapolate from the 10″/32 (25.4 cm) Marks I, II, III and IV installed on board the ironclads and battleships of the Victoria, Thunderer, Devastation and Barfleur classes, all being posterior to the ship’s completion. Indeed this model was developed from 1882 and introduced in 1884 for the Mark I, so too late for this type of cruiser. However this was an AP only type shell, weighting 500 lbs. (227 kg), as much as a WW2 light aerial bomb. The gun weight was about 30 tonnes, and the rate of fire about 0.5 rounds per minute.

Secondary Armament:

These cruisers were also armed with four 5.1 inches (130 mm) or 4.7 in (120 mm) guns, two to each side at the end of the “casemate”. These were two lightly armoured walls with openings for the guns, limiting their traverse to a mere 90°. Only possible comparison was the 7″/36 (17.8 cm) Mark I of 1884 made for the Mersey class cruiser, a 7 inches 36 caliber rifled, breech loading gun. But closer to it was the 5″/25 (12.7 cm) BL. This widespread gun was indeed from 1875, in service by 1878 a 25 caliber. It had a Bagged HE shell weighting 50 lbs. (22.7 kg) with a 4.45 lbs. (2.02 kg) Cord 7.5 propellant charge and a muzzle Velocity of 1,750 fps (533 mps). Around 100 were stored per gun. It was commonplace on sloops and cruisers of the 1880s.

The main armament, a turning table protected by partial armoured walls

Light Armament:

Sources are diverging on details. For Conways, they were given two 2.75 inches guns, placed on either side of the front bridge, behind the forward “turret”. No information available.

Other sources are stating this was a mix of two twin Armstrong Whitworth 9-pounders or 57 mm (2.2 in) long guns, and four 11 mm (0.43 in) Gatling guns plus four 37 mm (1.5 in) Hotchkiss guns, and eventually two 4-barrelled Nordenfeldt guns and two torpedo tubes. In addition the ship carried and could unload two pinnaces, armed with spar torpedoes acting as on-board torpedo boats. This figure is copmletely different from Conways however, and it is possible this data was directly taken from the previous Chilean Cruiser, then updated before departing or upgraded once in China. This was a considerable armament for close range fighting, and the only place these guns could have been the front and aft section roof of the main battery deck, as boats were stored on either side, and the decks.

Specifications

Specifications (as built) |

|

| Dimensions | 64 m x 9.75 m x 4.57 m draft (210 x 32 x 15 ft) |

| Displacement | 1,380 tonnes standard, circa 1,542 tonnes Fully Loaded |

| Crew | 177 |

| Propulsion | 2 shaft HCR, 4 cyl. boilers, 2,887 ihp. |

| Speed | Top speed 16.5 knots, 5000 nm range/8 kts, about 300 tons coal. |

| Armament | 2 x 10-in (254 mm), 4 x 4.7 in (120 mm), 2 x 2.75-in (76 mm) |

| Armor | 0.27 in (6.8 mm) protective deck, 1 in turrets (25 mm), 0.5 in CT (30 mm). |

Src/Read More

Robert Gardiner (Hrsg.): Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships 1860–1905

Arlington, L. C., Through the Dragon’s Eyes (London, 1931)

Wright, R. The Chinese Steam Navy, 1862–1945 (London, 2001)

Wright, R. “The Chinese Flagship Hai Chi and the Revolution of 1911”.

The Desk Hong List. Shanghai: North China Herald. 1884.

Brassey, T. A., ed. (1895). The Naval Annual. Portsmouth Griffin Co

Friedman, Norman (2012). British Cruisers of the Victorian Era.

Inouye, Jukichi (1895). The Japan-China War: The Naval Battle of Haiyang.

Jacques, William H. (1898). “Torpedo Boats in Modern Warfare”. Cassier’s Magazine.

Van de Ven, Hans (2014). Breaking with the Past: The Maritime Customs Service and the Global Origins of Modernity in China.

Wright, Richard N.J. (2000). The Chinese Steam Navy. Chatham Publishing

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chinese_cruiser_Chaoyong

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Beiyang_Fleet

http://www.navypedia.org/ships/china/ch_cr.htm

http://www.navweaps.com/Weapons/WNBR_Main.php

The Chao Yung class in service

Chao Yung (Wade–Giles), in chararacters 超勇; and in pinyin: Chāoyǒng meant “Valiant”. This cruiser was launched at Mitchell Yard on 4 November 1880, completed on 14 July 1881 and commissioned on 22 November 1881, so a year after her launch. The second ship ordered, Yangwei was launched on 29 January 1881, completed on 15 July 1881 and commissioned in 22 November 1882.

Both had Chinese crews but Western captains and instructors for their first trip, arrived previously by ship. They sailed out of the Tyne River on 9 August, and stopped in Plymouth Sound. Two days later, Admiral Ding Ruchang took command of them for their departure to China. They arrived on 20 October in Hong Kong and stopped at Canton (now Guangzhou) and Shanghai, and afterwards sailed north to the strategically important Taku Forts (the Yangtze gateway to Beijing). Chaoyong was approached by the Hongzhang, to take on board the diplomat inspecting the dredging of the port at Taku (now Tianjin). At last, both cruisers joined the Beiyang Fleet under Ruchang’s overall command. They served for their whole career with the Beiyang fleet; rotating each year, in Taku during the summer and in Chemulpo in Korea, during the winter. They saw no action during the Sino-French War, but the later Sino-Japanese War. They fought at the critical Battle of Yalu River on 17 September 1894, both sinking the same day.

About completion and the Chinese commission:

On December 18, 1879, China and Britain formally signed a shipbuilding contract and on January 15, 1880, the Elswick (not Mitchell ?) Shipyard started construction of the lead ship, but a the suggestion of Jin Denggan, the cruiser pair was temporarily named “Taurus”, meaning both were built in Europe (from the allusion that Zeus was turned into a Bull when abducting the woman Europa in Greek mythology). On December 6th, the Qing Dynasty created a receiving team of more than 200 notables led by Beiyang coastal defense supervisor, while named admiral Ding Ruchang at its head, and Lin Taizeng as deputy director, Deng Shichang and others. They settled in Tianjin. On December 10, the receiving team took a boat for Shanghai and started training. On the 23, Ding Ruchang, the British attaché Greyson took a French merchant ship which sailed to the UK for acceptance of both cruisers. On December 27, Li Hongzhang officially named both ships.

On February 20, 1881, the receiving team arrived in Shanghai, and Ding Ruchang ordered to sail to UK and the British yard. On the 27 February, the receiving team set off on the Chinese Merchant steamer Haichen and arrived in Newcastle on April 30, anchored in Ellswick to watch over the the construction process. They observed various problems such as material price increase, design modification, strikes and delivery problems, so the construction was repeatedly delayed; The contractor reused parts originally scheduled for the cancelled Chilean warship to gain time, but it was not enough. Construction of the Chaoyung was relatively quicker, but not the Yangwei, so she was not completed before the spring of 1881. Afterwards, first yard trials were delayed by bad weather and Li Hongzhang was quite vocal about the situation. He put pressure on Jin Denggan to urge the progress of sea trials and fixes, and on July 15th, Yangwei was ready to conduct a full sea trial session. She nearly collided with a fishing boat on her way, as the latter accidentally trespassed the test area, but still 2,700 indicated horsepower (2,013 kilowatts) were recorded as well as 16.4 knots (30 kilometers per hour), to the satisfaction of the team.

The difficult journey to China:

On August 2, the team officially took over the ship and at 13:00 on August 9, both cruisers set off from Newcastle to Plymouth. At 04:00 on the 17th, they left Great Britain for the long voyage home. This journey was troublesome: shortly after entering the Mediterranean Sea, Yangwei separated from Chaoyong and drifted 80 nautical miles from Alexandria for two days due to lack of coal. She was found later by her sister ship and eventually resupplied. However when passing through the Suez Canal, the propeller of the Yangwei was damaged to the point it needed repairs, which was done at the nearest facility in drydock. After entering the Indian Ocean, bad luck stroke Yangwei again as she had a mechanical failure. She was stopped for emergency repairs, and during this, a fire broke out in the boiler compartment. After repairs, both cruisers were underway, while on October 15 they encountered a tropical storm off Hong Kong. At 16:00 this day they rescued 4 sailors in distress, trapped on the islands and reefs. The following day, both cruisers headed to Guangzhou and Fuzhou. In Guangzhou, Zhang Shusheng, governor of Guangdong and Guangxi, led officials onboard for an official visit. On November 18, both cruisers arrived in Dagu, Tianjin, joining the Beiyang Fleet. At the time, they were the most advanced warship of the Chinese Navy and became the spearhead of the Beiyang Fleet. Captain Deng Shichang took command of Yangwei and British officers sailed for home.

Chao Yung

The Sino-French war and interwar years:

On 23 June 1884, Chaoyong, Yangwei, the corvette Yangwu and the sloop Kangji, met a French squadron, and a discussion took place between the commanders of each fleet. The French put on a firing demonstration as an argument in between. The Chinese fleet then joined force with Yang-Wu and sailed to Foochow (now Fuzhou), while the two protected cruisers sailed back to Taku later. The Sino-French War broke out, during which the Beiyang fleet saw no action. The two cruisers were at some point scheduled to break the French blockade of Formosa, and for this, she was, in concert with her sister-ship, redirected to Shanghai in November. However the overall command recalled them as there were growing tension with the Japanese about Korea. Chaoyong and Yangwei used to operate always together, out of Taku, frozen during the winter, so they were based during each winter in the Korean port of Chemulpo (now Incheon).

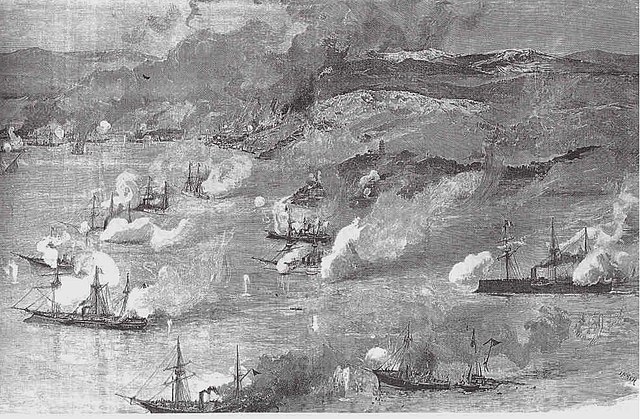

The battle of Foochow in 1884

The Chaoyong at Yalu:

The First Sino-Japanese War broke out in 1894, and Chaoyong supported troop transports until the fleet made contact with a Japanese on the morning of 17 September. The battle of Yalu started, with the Japanese fleet, mostly made up of cruisers, quickly closing in while the Chinese try to drop their anchors, raise steam and manoeuver to for form up a battle line. But the lack of training of the previous months and years meant it was never achieved, and the ship were not arranged in an optimal way to fire, their views blocked by each others. Chaoyong was one of four behind this disorderly formation. In addition to the lack of training, the ships suffered from poor maintenance over the years, to such point thy could barely make 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph). As they were used to operate together, they manoeuvered to close by. But the battle line was stranger to their initial design, due to their lack of armour. They were meant to operate in distant solo by themselves, preying on smaller ships.

The fight started at 3,000 yards (2,700 m), and several IJN vessels concentrated rapidly on the Chaoyong, which was set ablaze within minutes. Soon, the ship ws completely engulfed in flames for the entire length of the central superstructure, all the wooden partitions layered with flammable varnish feeding the flames. Chaoyong, almost blind by its own smoke, and somewhat hidden, managed to break away to beach herself on a nearby island when she collided with the cruiser Jiyuan. The damage was so extensive that she started to list starboard and sinking in shallow waters. Most of the crew went down with her, and a few survivors were rescued by a Chinese torpedo boat.

The Yang Wei in action

On 23 June 1884, Yangwei teamed up with Chaoyong, corvette Yangwu and sloop Kangji during the pre-Sino-French war meeting. The Chinese headed for Foochow (now Fuzhou) while the YangWei and her sister ship made it for to Taku, under the protection of the fort’s heavy artillery. The Sino-French War ended as a crushing defeat for the Nanyang fleet, which was given no support by the Beiyang fleet despite speculations both cruisers could be sent to break the French blockade of Formosa, but instead they headed to Shanghai in November, and quickly recalled back in the north as tensions grew in Korea. The cruisers were based in Taku in the summer, and Chemulpo in winter (Korea)

A complex situation:

At this time, Japan stepped up its control of North Korea, and in order to contain this expansion, the Qing government decided to convince foreign powers into the Korean Peninsula to counter Japan. On May 7, 1882, Ding Ruchang led the two cruisers escorting the Ma Jianzhong, Qing’s special envoy to North Korea, signing the “North Korea-U.S. Treaty on Trade”. On June 25, 1882, Ding Ruchang participated in the German-North Korean contract negotiations. On July 23, the Renwu Mutiny broke out in North Korea and soldiers and civilians stormed the Zhuyi embassy, which was burned downed and kill the Japanese staff here. King Xuanxuan Dayuan took control of it later, but Japan sent its army to prepare for retaliation. The Qing Dynasty took countermeasures, sending the Chaoyong and Yangwei to Incheon, in full view of the Japanese warships, acting as a deterrent, her main guns surpassing all the Japanese had at that time. The Japanese indeed only had a the old ironclad Fuso there as lead ship. On August 20, the Beiyang Navy escorted the troops ships carrying 4,500 troops from the Huai army (Admiral Wu Changqing) in Korea. On the 26th, the Qing army entered Seoul and arrested the local Korean monarch, and controlled the city. This was only a respite however.

The Sino-French war

In 1884, war erupted between China and France over control of Vietnam. Chaoyong and Yangwei were went to Shanghai, and met there Nanchen, Nanrui, Kaiji, Chengqing, and Yuyuan, preparing to head further south and meet the French fleet. The Qing Dynasty also purchased a batch of 37 mm cannons from the Dias Company, which equipped the Chaoyong and Yangwei (two each). On June 23, the cruisers confronted the French Far East Squadron together with the Nanyang Navy ships Yangwu and Kangji. Japan took advantage of that void in Chinese naval presence in the area, and sent troops to the south to restart their occupation of Korea. Due to the degrading situation, the two cruisers were ordered back north to Taku (Dagu) and missed the naval battle of Majiang.

In November, both cruisers weere ordered south again, anchoring in Shanghai. On December 4, the nationalist party members supported by the Japanese Army Minister launched the Jiashen coup, and the Japanese army occupied the palace in Seoul. The former North Korean minister pleaded Yuan Shikai, special envoy of the Qing Dynasty for support and Ding Ruchang was ordered to send Chaoyong and Yangwei northward again, escorted by the gunboat Weiyuan and carrying troops reinforcements of the Huai army, to be landed in North Korea. Therefore, once again, bth cruisers could not help the Nanyang fleet in the Sino-French war. At the beginning of 1885, tensions between Britain and Russia were increasingly acute and on April 12, the British Asian Fleet occupied North Korea’s Juwen Island, using it as a base to dissuade the Russians to land an army in Korea. On the 16th, Ding Ruchang led Chaoyong and Yangwei to Juwen Island, and started negotiations with the British fleet. In 1887, the ironclads Dingyuan and Zhenyuan joined the Beiyang Navy, and Chaoyong and Yangwei were versed in second line, used from then on mainly for for training.

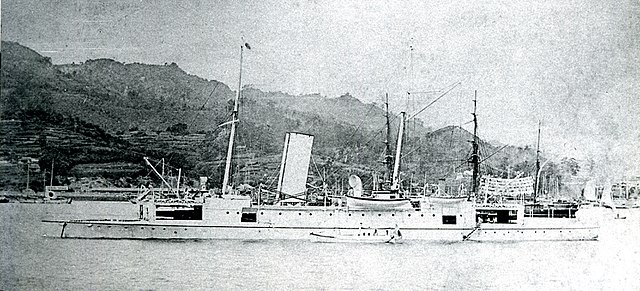

Chinese Cruiser Yangwei in drydock, in completion at the yard. Note the “turret” with bad weather protective panels installed.

The Sino-Japanese war

On May 17, 1894, Li Hongzhang inspected the navy in Weihai. Due to theese ten years of intense service without maintenance, both ship’s hull were in poor conditions, and the boiler needed serious cleaning and repairs, or replacement, while most of their powerplant was worn out. Both ships were only capable of maintaining 7 knots (13 kph) in the best conditions, less than lhalf their original figure. The main guns were also obsolescent by now. The Tianjin Machinery Bureau carried out some repairs, but the ships would never be in the same conditions again. Their secondary guns were also worn out and old. The situation in North Korea degraded however still, and on June 6th, Nie Shicheng, general of Taiyuan in Shanxi, led a troops of 910 plus heavy equipment of the Qing army, landing in Baishi Puli in Asan Bay. The Jiyuan, Yangwei, Pingyuan, and Caojiang escorting steamers arrived in North Korea and stationed in in Asan, Incheon, Datongjiang to protect the interests of Chinese citizens there, and evacuate them in case. On July 25, the Japanese sank the protected cruiser Guangyi and transport ship Gaosheng leased at the naval battle of Toshima. They also badly damaged Jiyuan and captured the gunboat Caojiang, which was the start of the war. The Yangwei and Chaoyong participated in several escort and patrol operations before this, and were prepared for war the best they could.

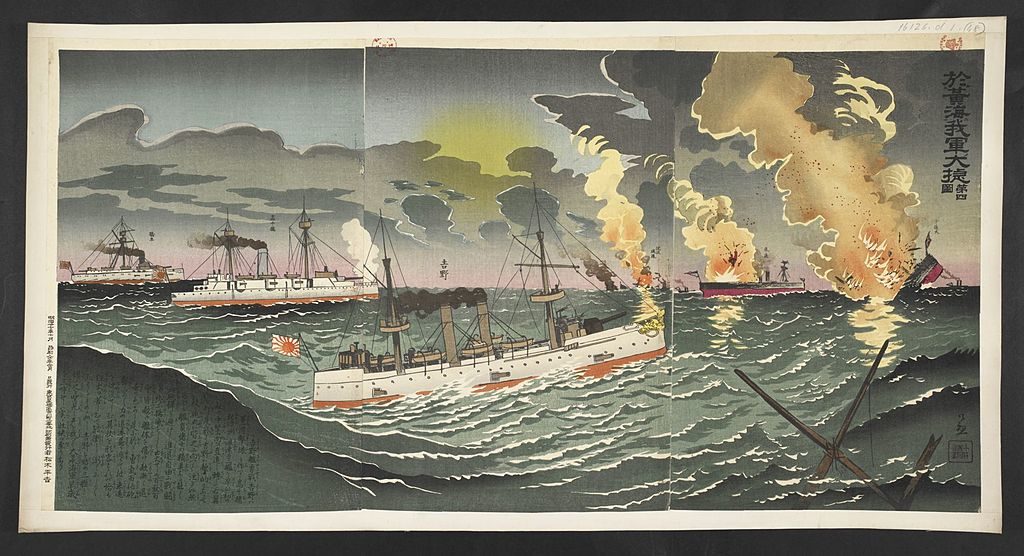

The Battle of Yalu

On September 17, 1894, the Beiyang Navy sailed to Dadonggou, at the mouth of the Yalu River. There, they syarted to cover landings of the Qing army. Some warships had a shallow draft and were moored closer to the coast in Dadonggang to support by artillery gunfire the landing zone. After 12:00 a watch on Zhenyuan saw smoke at the horizon. The Beiyang fleet immediately was prepared to left their anchorage and form a battle line. Chaoyong was to be the ninth and Yangwei the tenth ship of this line, together they formed the fifth combat unit. The fleet started to take a horizontal combat formation, and Chaoyong and Yangwei ened at the end of the right wing. Due to the lack of maintenance, they could not follow and fell behind the main force. At the same time, the IJN flying squadron led by Rear Admiral Tsuboi Kozo, left the squadron, accelerated and turned right to head straight for the Chaoyong and Yangwei, the weakest ships of the Beiyang Fleet.

Meawnhile Dingyuan opened fire while Chaoyong and Yangwei fired their main bow gun. To improve hit rate, the Japanese waited until they were much closer. At 12:55, IJN Yoshino determined that the distance was now 3000 meters, and opened fire with her starboard artillery. Due to the close distance, hits were almost certain. Within a few minutes, the shell plates of Chaoyong and Yangwei were shot through, many officers and soldiers were killed and injured and their secondary guns put out of action. The Japanese ship continued their outflanking manoeuver, and the Chaoyong and Yangwei turned right to present a smaller target, but lacking the speed, they could not made the manoeuver fast enough. Ma Jifen onboard Zhenyuan observed the flying squadron moving to the right of the Beiyang fleet at twice the speed of the best Beiyang warship. They effectively made a crossing fire, causing the Chaoyong and Yangwei to be surrounded, Nelson style.

Around 13:05, the fire broke out in Yangwei and rapidly spread. At 13:08, the cruiser however succeded in sending a 10-inch (254 mm) shell on Yoshino’s rear deck, detonating and killing 2, injuring 9 people, causing a fire. At about 13:20, the ironclad Hiei crossed the Beiyang Fleet in turn and after crossing it, fell on Yangwei. Fire was exchanged point blank, around 400 meters to the starboard. At 14:31, the 1st flying suqadron retreated to protect the hardly battered gunboat Akagi, forming a cross fire and blasted the Yangwei, which catch fire again. Severely damaged, the cruiser was limping back in the direction of Dagushan Bay, trying to beach herself and save the crew. On her way, she crossed the path Jiyuan, running away fro the fight and the latter rammed the Yangwei, but reversed and left after the accident, leaving the Yangwei dead in the water. The Yangwei took heavy flooding and eventually capsized and started to sink, her surviving crew members evacuated but Captain Lin Luzhong went down with his ship. On September 18, the combined fleet found Yangwei not completely sunk, and sent a spar torpedo boat to finish her off.

The first Sino-Japanese War broke out in 1894, Yangwei was covering troop transports, and she spotted, like other ships of Admiral Ding Ruchang, the Japanese fleet approaching on the morning of 17 September. The Chinese fleet was at anchor at the time and prepared to form in line, but it was too late already, and they never achieved the desired formation. The Yangwei and Chaoyong fought together, opening fire at 3,000 yd (2,700 m) and both were quickly engaged by the Japanese. Wooden flammable wooden partitions, with heavily coats of varnish applied over the years feed the flames on board Yangwei, so much so she was rendered blind, her guns disabled. The captain ordered her to be be beached on a reef, a few miles away due south. The majority of her crew was dead, injured or already jumped into the water at that time, without orders. The morning following of the battle, she was approached by the cruiser IJN Chiyoda, which dispatched one of her own spar torpedo boats to finish her off. The Japanese considered her rightly as obsolete and were not interested by a capture. The Japanese fleet was kept at a distance and sent smaller boats to investigate in case the Chinese would use their onboard still functioning torpedo tubes. The spar torpedo did its job and badly damaged the hull, preventing the ship to go anywhere. The fire was still raging in parts completing the destruction. Her wreck was demolished many years later.

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign